1. Introduction

In recent decades, the escalating issue of over-indebtedness in China, propelled by the proliferation of diverse consumer credit forms, has become increasingly conspicuous. This trend of financial instability is particularly pronounced among the younger population, characterized by a high accumulation of debt, low asset holdings, and a propensity for increased financial risk-taking. Over the last two decades, a combination of socio-cultural shifts, evolving expenditure patterns, changes in social policies, and structural economic transformations have significantly fueled the growth of consumer credit (ECRI, 2017). These factors have collectively contributed to the normalization of personal debt, and heightened consumer dependence on borrowing mechanisms.

According to Friedline and Song (2013), for example, the younger generation in the USA is currently experiencing unprecedented debt levels. The broad deregulation of the American financial sector, alongside practices in predatory and fringe banking, has facilitated easy, but often expensive, access to financial resources for individuals (Dwyer, 2018; Autio et al., 2009). These lending methods, combined with the widespread availability of credit, the prevalence of bank fraud, money scams, and inflation, exert considerable pressure on consumer financial health (Gani, 2022). The consequences of over-indebtedness are far-reaching, extending beyond individual welfare to societal issues such as poverty, social exclusion, and both physical and mental health challenges (Białowolski et al., 2019). Significantly, over-indebtedness poses a threat to the stability of the financial system due to the potential for debt repayment defaults. This issue is recognized as a pressing concern in various countries, including China, where over-indebtedness underscores the need for urgent attention and effective policy interventions.

Our research leverages data from ‘Debtors Avengers’ (hereinafter, DA), a Chinese online community on Douban.com that has been offering guidance plus informational and emotional support on debt-related issues since 2018. This study meticulously analyzes a collection of posts from 2019 to 2022, seeking to uncover the underlying causes of over-indebtedness among the community members. We employ a hybrid content analysis methodology, blending computerized Artificial Intelligence (AI) analysis with manual coding. This approach is particularly effective in deriving meaningful insights from unstructured textual data.

By scrutinizing the reasons behind indebtedness through the prism of digital media, our study makes a significant contribution to the understanding of over-indebtedness and the burgeoning field of financial social work. Our underscores the necessity for future research to engage closely with financial service providers and support organizations. The insights gleaned from this study are expected to be invaluable for policymakers in formulating strategies aimed at preventing over-indebtedness among microfinance borrowers, thereby contributing to poverty reduction efforts. Our findings shed light on the complex web of factors that lead to financial distress, offering a roadmap for more targeted and effective policy interventions.

2. Literature Review

To fully grasp the concept of over-indebtedness, it is essential to explore the diverse perspectives and distinctions within the debt arena. It is critical to acknowledge that not all forms of debt are inherently problematic. Interestingly, what might be technically classified as debt may not always be perceived as debt by individual consumers. Within this context, three primary consumer perceptions emerge: ‘credit’, which signifies an agreement where both a willing lender and borrower fulfill their respective obligations; ‘debt’, indicative of a scenario where expected payments have been missed; and ‘over-indebtedness’ or ‘problem debt’, denoting situations where consumers find themselves unable to meet their debt obligations without experiencing considerable hardship, taking into account their income and assets (Lea, 2021).

The state of over-indebtedness can arise from a range of factors, including an unwillingness to repay, an incapacity to repay, or repayment not made due to onerous actions that may be required. This condition is often discernible when borrowers are compelled to reduce their spending beyond typical levels, or when they face greater sacrifices than originally anticipated (Gonzale, 2008).

In the broad spectrum of over-indebtedness, young people emerge as a demographic particularly vulnerable to financial instability. Often grappling with unstable incomes and lacking substantial assets, they are prone to resorting to high-interest loans, which significantly escalates their risk of entrenchment in a cycle of over-indebtedness (Autio et al., 2009). This situation is further compounded by their tendency toward financial risk-taking, leading to potential payment defaults and debt enforcement issues, as highlighted in related financial risk literature.

Recent years have witnessed an upsurge in scholarly discourse on the process of indebtedness. This increase in attention is largely a response to the subprime economic crisis (Houle, 2014) and the growth in consumer credit (Oksanen, Aaltonen & Rantala, 2016), which have collectively underscored the vulnerability of youth to debt and the precarious nature of their financial obligations. The existing literature aims to unravel and address the phenomenon of over-indebtedness by offering diverse perspectives. These perspectives encompass both the life-course and structural viewpoints, delving into the fundamental causes of over-indebtedness among younger populations. This multifaceted approach to understanding over-indebtedness is crucial in developing comprehensive strategies to mitigate its impact on this particularly at-risk group.

2.1. Life Course Perspective on Over-Indebtedness

The transition from adolescence to adulthood represents a pivotal period marked by significant changes and decisions that lay the groundwork for an individual’s financial future. Consistent with the life-cycle hypothesis (LCH) (Ando and Modigliani, 1963; Modigliani and Brumberg, 1954), this phase of early adulthood is often characterized by increased borrowing, as young adults strive to attain a lifestyle that surpasses their current earnings, leading them to depend on credit or loans. This stage, which typically involves a shift towards independent living, presents young adults with heightened responsibilities, which they must navigate with relatively limited income, sparse assets, and constrained resources (Robson et al., 2017). Guided by the hopeful anticipation of enhanced future income, young adults maintain a belief in their ability to manage and repay their debts. However, this optimism frequently clashes with the harsh realities of their financial acumen and behaviors (FINRA, 2013).

Complicating matters further, factors such as unstable income, ongoing educational commitments, and a lack of sufficient financial literacy and experience place young adults at a distinct financial disadvantage (OECD, 2020) . While access to credit is essential for achieving significant life milestones, an overdependence on it poses serious risks. Credit can jeopardize economic independence, increase the likelihood of bankruptcy, and have detrimental effects on overall well-being (Houle, 2014; Dwyer et al., 2012). This nuanced understanding of young adults’ financial behavior and challenges underscores the need for more targeted financial education and support systems to aid them in navigating this critical life stage.

Marked by the transition to adulthood, this life stage is also characterized by a confluence of factors that elevate the risk of accruing debt. These include significant life-stage transitions, unforeseen events, a lack of savings, and a precarious position in the labor market (Autio et al., 2009). Beyond the inherent financial challenges and decisions associated with becoming an adult, it is crucial to consider the role of family dynamics and unexpected life events in shaping financial stability.

Critical life events such as marriage, childbirth, the dissolution of relationships, job loss, or sudden caregiving responsibilities bring with them substantial financial burdens. These occurrences often serve as pivotal ‘turning points’ that can steer individuals towards debt, with the impacts closely tied to shifts in income levels and family size (Oksanen et al., 2015; McCloud & Dwyer, 2011). The interplay of these various elements underscores the complexity of financial management during this transitional phase of life. Understanding the multifaceted nature of these influences is key to developing more effective strategies for preventing and managing debt among young adults.

The prevailing empirical literature on over-indebtedness predominantly focuses on socio-demographic and economic determinants within the traditional Life Cycle Theory framework. However, this approach does not comprehensively address the impact of individual behaviors and decision-making processes. It is imperative to recognize that individuals frequently diverge from the rational economic assumptions posited by this theory. Consequently, individuals may incur over-indebtedness through behaviors that defy conventional ideas of economic rationality. These patterns are particularly evident during transitional life stages, a time when young adults, in addition to their inexperience in financial matters, are inclined to heavily rely on credit. This reliance is often driven by a desire to fulfill lifestyle expectations influenced by their social peers. Understanding the nuances of these behavioral factors is essential for developing a more holistic view of over-indebtedness, particularly among younger demographics navigating key life transitions.

Compulsive purchasing, a culture of immediate gratification, and the pervasive ‘buy now, pay later’ ethos are increasingly recognized as key contributors to over-indebtedness and, in many cases, eventual bankruptcy (Achtziger et al., 2015; McNeill, 2014). Research conducted by Limerick and Peltier (2014) supports the existence of a direct correlation between impulsive behavior, higher credit card balances, and their misuse among college students. This impulsivity often leads to the accumulation of unsustainable debt levels, with students struggling to amend their spending habits despite an awareness of the perils associated with over-indebtedness (Dittmar & Bond, 2010; Meier & Sprenger, 2010). Additionally, there is evidence suggesting a heightened incidence of over-indebtedness among frequent ‘buy now, pay later’ users, particularly those who regularly incur fees and rely on additional borrowing to settle their dues (Fook et al., 2022). These insights highlight the crucial influence of individual choices and behaviors in the broader context of over-indebtedness, a phenomenon that is especially pronounced among the youth. These findings call for a deeper understanding of these behavioral patterns to develop effective interventions targeting young adults, a demographic particularly susceptible to these trends.

2.2. Structural Perspective on Over-Indebtedness

An in-depth understanding of over-indebtedness requires analyzing the complex interaction between macroeconomic environments and transformations in financial policies. Young adults, particularly those in the midst of transitioning to adulthood, are confronted with escalating uncertainties. This is compounded by a myriad of factors such as precarious employment opportunities, wage stagnation, and the prevalence of irregular work schedules typical of flexible contractual arrangements (Hardgrove et al., 2015). These vulnerabilities in the labor market are further intensified by overarching economic dynamics, including periods of recession and soaring living costs.

Such broader economic factors result in unstable living conditions and diminished income, while simultaneously restricting access to affordable credit options. Consequently, these conditions foster a propensity among young adults to accrue debt as they navigate these financial challenges. This multifaceted scenario underscores the need for a holistic approach in understanding and addressing the issue of over-indebtedness, considering both individual circumstances and the larger economic context that influences young adults’ financial decisions and vulnerabilities.

The surge in personal debt in recent times is closely associated with financial deregulation policies initiated in the late 20th century. Starting in the 1970s, federal deregulation allowed credit lenders to bypass state usury laws and interest rate caps. This shift enabled a so-called “democratization” of credit, albeit often through subprime lending and predatory practices (Williams, 2005). This development coincided with a downward trend in real wages and employment security, paired with escalating costs of housing, education, and dwindling social benefits. These combined factors frequently render credit as the only feasible option for many individuals to maintain financial stability (Williams, 2008).

Over time, financial policies have significantly increased consumer access to credit. This has been achieved through empowering banks with the authority to adjust interest rates, broadening the scope of loan marketing to reach households that were previously excluded, and fostering the development of innovative credit instruments (Campbell & Hercowitz, 2009). This intensified marketing of credit specifically targets less affluent demographics. Coupled with escalating interest rates and the widespread use of revolving credit, these strategies have significantly heightened the debt obligations shouldered by American families. This growing debt burden is further intensified by stagnant wage levels, compelling lower- and middle-income families to depend more on credit to maintain their living standards (Dwyer et al., 2011). The issue of over-indebtedness is particularly acute among economically vulnerable groups, such as the unemployed, who face the greatest risk of accumulating unsustainable levels of debt (Anderloni et al., 2012). However, there is a paucity of research examining the evolution of credit usage and debt burdens among young adults along social class divisions. Individuals from affluent backgrounds or college-educated youths often use debt as a tool to accumulate wealth and finance postsecondary education. In contrast, those youths from less affluent backgrounds may find themselves grappling with unsecured debt, primarily as a mechanism to compensate for stagnant income.

The contemporary consumer culture has witnessed a normalization of credit, a trend significantly propelled by credit liberalization policies that target young consumers (Lachance et al., 2005). This shift has ushered in various risks, including issues of credit misrepresentation and the increasingly ambiguous distinction between credit and debt. Furthermore, the internet has emerged as a favored platform for facilitating these financial transactions and loans (Hohnen and Böcker Jacobsen, 2015). The ease of access to costly short-term loans via online channels can exacerbate financial challenges, leading to defaults and debt enforcement actions. These trends underscore the severe consequences of over-indebtedness, affecting not only debtors but also creditors and the broader economic landscape.

2.3. Review

The life-course perspective primarily concentrates on the financial behaviors and decisions individuals make throughout their lives. This approach highlights the significance of developmental and transitional stages in shaping financial attitudes and behaviors. However, by focusing predominantly on the behavioral aspects at the individual level, the life-course perspective may inadvertently neglect external structural factors that profoundly impact youth debt. These factors include credit liberalization, economic downturns, and wage stagnation. Conversely, the structural perspective delves into the broader socio-economic and political frameworks that create environments conducive to indebtedness. While this approach effectively underscores the influence of macroeconomic trends and policy changes, it may fall short in adequately exploring the interaction between these structural elements and individual life-course factors that collectively shape the debt landscape for young people.

The current body of research provides valuable insights but tends to obscure the intricate interplay between individual financial behaviors and broader macroeconomic structures. This narrow focus overlooks the complex interaction between individual life-course events and macro-structural elements, which together significantly contribute to youth indebtedness. The objective of this paper is to explore how the escalating debt issues among young people may be not only attributed to their specific life situations, but also to the increasing digitalization and normalization of credit.

In this study, we selected the Douban online community “Debtors Avengers” as the core research object, and deeply analyzed the posts from 2019 to 2022, with the intention of revealing the underlying reasons behind over-indebtedness. We employed a hybrid content analysis method, blending computerized analysis with human coding, facilitated by AI. This approach is particularly effective in deriving meaningful insights from unstructured textual data. By examining the causes of debt through the lens of digital media, this study provides new insights into the emerging literature on financial social work and over-indebtedness. The findings of this study have far-reaching implications for guiding policymakers in preventing over-indebtedness among microfinance borrowers, as well as further alleviating poverty in the society. Additionally, our in-depth exploration of the current living conditions and challenges faced by individuals in debt aims to foster the healthy evolution of the financial credit market. It also seeks to support young individuals in cultivating sound consumption habits and contribute to the maintenance of social cohesion and stability.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

This paper derives its data from the ‘Debtors Avengers’ online community, established in December 2019 on the Chinese website named Douban.com, which boasts 57,651 members. Utilizing Atlas.ti software (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Germany), we extracted online texts spanning from December 2019 to December 2022. Our initial search was confined to publicly accessible posts, totaling 30,250. Additionally, the ‘Debtors Avengers’ group, which is accessible only upon application, was established to unify Chinese individuals grappling with debt for various reasons. To preserve member anonymity, usernames and any identifying details in posts were excluded from our data collection. The online community features five sections: ‘Must Read’, ‘Experience and Knowledge’, ‘The Road to Shore’, ‘Ask a Question’, and ‘Reflection’. The ‘Regulations and Announcements’ section serves as a bulletin board for group administrators, while the remaining sections cater to member posts, segmented by the nature of the content. Our analysis centers on the ‘Road to Shore’ section, focusing primarily on the reasons behind the members’ indebtedness. The data preparation began with an Excel-based cleanup to eliminate duplicate posts. Considering our focus on personal accounts related to indebtedness, any off-topic posts were excluded. This resulted in a final dataset comprising 2,417 posts over a period of three years.

3.2. Coding Rubric and Procedures

In this study, we implemented a systematic, step-by-step coding procedure to categorize the posts from the ‘Debtors Avengers’ online community on Douban.com. This involved progressively coding the related concepts and their hierarchical relationships. The specific steps of coding were as follows: First, we imported the final selection of Douban.com posts into Atlas.ti software. Second, we conducted an analysis and coding of the text, with the reasons for indebtedness derived directly from the posters’ statements. We employed open coding to summarize themes, creating three levels of indicators. These indicators were then organized to delineate the interrelationships and analogies among themes, forming second-level indicators. Subsequently, these themes were further condensed based on the second-level indicators to establish first-level coding. During this process, we paid particular attention to recurrent content, finalizing the coding after thorough sorting and generalization. This paper details our hybrid content analysis of these posts, which encompassed both manual categorization and coding, as well as automated content analysis using the AI capabilities of Atlas.ti. Content analysis conventionally involves quantifying phrase frequency within a given text. Accordingly, textual data is distilled into phrase frequency counts, transforming qualitative textual information into quantitative frequency data. This conversion facilitates addressing research questions with a more quantitative orientation (Short et al., 2018).

4. Results

4.1. Overview of Liabilities of the Alliance of the Indebted Group

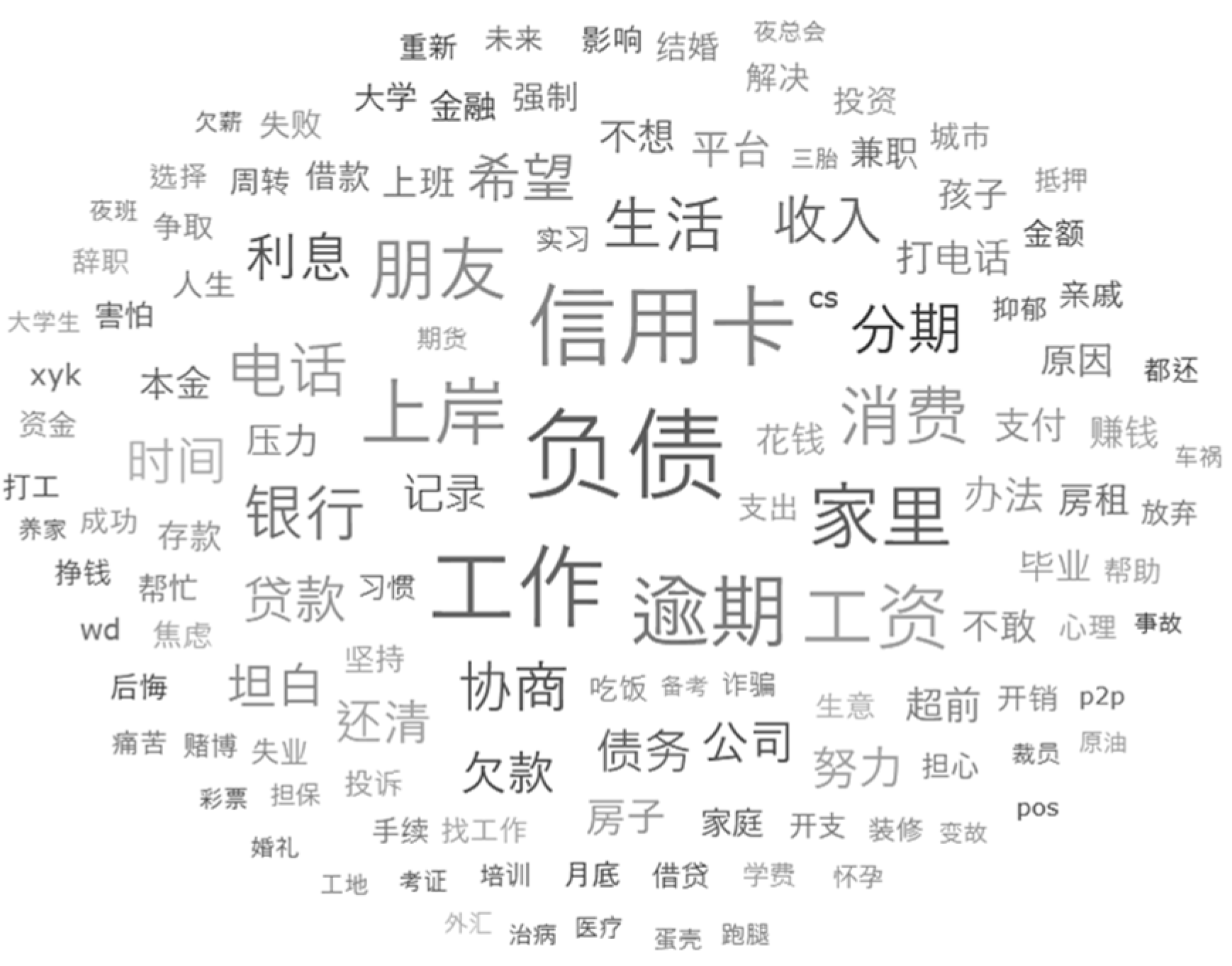

With the rapid development of the modern socio-economic landscape, especially the proliferation of consumer culture and technological advancements, the youth demographic has increasingly become a key participant and beneficiary in economic and social progress. However, this is accompanied by a growing burden of indebtedness. To gain a deeper understanding of the factors behind youth indebtedness and the social structures it reflects, the present study employs the Atlas.ti software for an in-depth analysis of a series of texts related to youth debt. Word clouds (word collection / cluster in different sizes denoting differences in importance), as the primary analytical tool of this study, display various keywords and their relative weights. All texts were imported into the Atlas.ti qualitative analysis software, setting the threshold to 1 to generate a word cloud. As shown in

Figure 1, the words “debt”, “consumption”, and “credit card” are significantly larger than other keywords, suggesting that youth indebtedness is primarily related to consumption and credit. This aligns with the recent prevalence of consumer loans, installment payments, and online lending. Furthermore, terms such as “tuition”, “rent”, and “wages” also occupy a significant place, revealing that in addition to consumer debt, the youth also face pressures related to basic living expenses, which could be associated with high tuition fees, housing prices, and low wage levels. This implies that in studying the issue of youth indebtedness, one cannot overlook the dual role of social structure and individual choice. Youth indebtedness is not merely a result of youth personal choices, but is also intertwined with macro factors such as the economic structure of society, the job market, and the education system. Additionally, terms like “finance”, “technology”, and “internet” also occupy a notable position in the word cloud, indicating that in modern society, technology and the internet have become significant factors related to debt. Emerging modes like online lending and financial technology offer more convenient lending paths for the youth, but also higher risks potentially. The word cloud reveals that the issue of youth indebtedness is not just a result of individual consumption choices, but more profoundly, it is closely related to social structures, economic models, and technological developments. Among these keywords, terms like “regret”, “pain”, and “pressure” also stand out, hinting at the stress and related life states that the youth demographic faces in the context of indebtedness.

4.2. Analysis of the Causes of Youth Debt Groups

4.2.1. Individual Causes of Youth Indebtedness

Younger generations are increasingly vulnerable to various factors that can lead to indebtedness, particularly during specific stages of their lives and under certain economic pressures. This vulnerability is especially pronounced in urban settings, where young individuals confront the significant economic challenge of livelihood indebtedness. In our study, 36.45% of the analyzed posts referenced liabilities related to everyday expenses, medical costs, and vehicle loans. The rapid pace of urbanization exacerbates this issue, as everything from soaring rental prices to the cost of basic necessities adds to the financial burden shouldered by young urban dwellers. Consequently, many young people resort to credit as a strategy to manage this financial stress. One participant shared: “When I left school and couldn’t afford rent, I had to resort to credit card payments for the first time, marking my initial venture into overdraft consumption”. Newly-graduated individuals, in particular, face substantial financial pressure at the onset of their careers, often finding credit to be the only viable short-term solution. Despite employment, managing substantial sudden expenses, such as initial rent payments, remains a challenge. In scenarios where social and familial support is lacking, alternative financial avenues such as online lending platforms become a crucial lifeline. Moreover, unexpected incidents exacerbate further their financial struggles, as illustrated by a participant who recounted: “Last year, I broke my hand in an accident...”. The reliance on credit cards and online loans underscores the heightened susceptibility of financially unprotected youth to abrupt economic downturns.

Indebtedness frequently correlates with perceptions of ‘over-consumption’. A significant portion of individuals, precisely 33.39%, attribute their debt to practices like ‘overspending’, ‘overconsumption’, and ‘irrational consumption’. These tendencies also render individuals more susceptible to abrupt economic shocks. For instance, one post vividly illustrates this mindset: “I used my overdraft card to get married, renovate a house... I overspent. Deep down, I know it’s excessive, but I can’t bring myself to face it”. This exemplifies a common scenario where consumers, despite understanding their financial limitations, choose to overlook long-term fiscal consequences for immediate gratification from appealing goods and services.

Yanjing Gao(2019) highlights that behind the seemingly affluent lifestyle of the ‘hidden poor’ youth lies a substantial debt burden. This new wave of ‘poor’, primarily driven by credit card and loan dependencies, symbolizes the intensification of China’s consumer culture. This youth group represents a unique demographic, overly fixated on the symbolic value of commodities. Moreover, digital consumer platforms, such as the virtual credit card product Ant Credit Pay (ACP), exacerbate this propensity for overspending. A poignant example is a user’s experience: “I was introduced to ACP in my freshman year. It gradually fueled my desires, leading to extravagant spending”.

This trend indicates that fintech (financial technology) tools significantly magnify consumer spending desires, precipitating indebted behavior. Social contexts and peer pressure also play pivotal roles in driving consumers to spend beyond their means. For instance, a user shared: “At the beauty salon where I work, I was persuaded to undergo an eyelid surgery on installment payments”. This not only underscores the influence of social and professional environments on consumption behavior, but also reveals how these pressures can compel individuals to spend well beyond their actual financial capacity.

In pursuit of economic self-reliance or entrepreneurial aspirations, some young individuals opt for self-employment, with 19.11% of the postings referencing “business failure” or “entrepreneurial failure”. This category of indebtedness, though reflective of an entrepreneurial spirit and a quest for an improved quality of life, often involves individuals engaging in small-scale investments or business operations in the hope of financial returns. As elucidated by one post author: “Lacking funds, I resorted to extracting money from Huabei and credit cards to acquire land and invest in ducklings, planning to start a farm. When cash became unattainable, I turned to the bank for a loan of 60,000 [8,300 USD]”. This account reveals how individuals, confronted with economic pressures, utilize a variety of financial instruments to invest in entrepreneurial ventures. Another post states: “Dissatisfied with my current situation and wishing to start my own business, I concealed from my family and became overdrawn on four credit cards amounting to 120,000 [17,000 USD], and incurred online loans of over 240,000 [35,000 USD]”. This highlights the pressures and risks borne by individuals in their pursuit of financial autonomy and life improvement, arising from challenges such as initial capital, market conditions, or management strategies. Their potential over-reliance on credit and possible lack of sufficient experience and knowledge in financial decision-making can lead to an excessive burden of debt.

The issue of investment-related indebtedness has garnered widespread societal attention. An analysis of data from the online community named “Debtors’ Alliance” on Douban.com reveals that 13.03% of the posts mention activities such as leveraging in stock trading, cashing out through credit cards and online loans for reinvestment in the stock market, and digital currency investments. These investors, in their pursuit of high returns, amplify their investments through leverage, often overlooking market risks, which lead to significant financial losses. Some investors even resort to unconventional means to acquire funds, hoping for rapid returns in the stock market, but such outcomes are frequently disappointing. Investment in digital currencies is also repeatedly cited as a cause of indebtedness. In the modern financial market, individual investors often lack sufficient risk awareness and investment experience, making them susceptible to market misinformation, thereby resulting in significant debt issues.

In the current societal context, the balance between individual economic behavior and financial responsibility among the youth demographic has emerged as a significant issue. The unique cultural atmosphere in China further intensifies this challenge, as the status of young people within their families, among friends, and in social networks often entails monetary expectations and obligations. Narratives in the posts, such as: “Despite financial hardships, I still transfer money to my parents monthly to ensure they remain unaware of my indebtedness”, and “To maintain the family’s economic image, I regularly send money home during holidays”, illustrate how youth, under financial strain, still adhere to cultural and societal expectations, upholding their financial commitments to family, even at the cost of accruing substantial debt. “Relational debt” is not limited to familial contexts. For instance, one posting notes: “To help a friend with medical expenses, I took an online loan of 30,000 yuan [4,200 USD]”. The economic support and obligations within friendships and social networks are often not purely personal choices, but are more influenced by deep-seated cultural values and societal expectations. This form of relational debt can also lead to significant economic risks. For example, one posting notes: “My sister and brother-in-law’s business failure led to a debt of nearly 1 million yuan [138,000 USD] which I was unaware of. During this period, I lent my brother-in-law up to 500,000 yuan [69,0000 USD]”. Such scenarios reflect how young people might become entangled in financial predicaments of other’s due to societal and familial expectations, despite a lack of adequate foresight or preparation.

The pursuit of academic advancement and the enhancement of vocational skills, as pathways for contemporary youth seeking better career development, often bring additional financial pressures. Young individuals, aiming to elevate their professional competencies, willingly opt for further education or participate in specialized training programs. This strategy of short-term investment for long-term growth undeniably escalates their financial burden, particularly when faced with a scarcity of job opportunities or delayed remuneration. Civil service exams and other large-scale recruitment tests typically involve a series of preparatory expenses. For instance, one individual recounts: “In preparation for a civil service position, I took part in multiple circuit exams and eventually succeeded, but this journey incurred substantial expenses, including travel, accommodation, dining, and tutoring fees”. While academic and vocational training provide young people with opportunities to enhance their market competitiveness, the associated costs often weigh heavily on them, especially when these investments have yet to yield anticipated returns. This scenario underscores how individual choices and structural pressures interact in the context of indebtedness contemporary youth.

After conducting a detailed textual analysis of 2,417 posts, a stark and striking theme emerged, that of deviant indebtedness, manifesting particularly in numerous posts where authors candidly shared their descent into the vortex of online gambling, leading to their financially impoverished predicaments. For instance, one narrator in a post explicitly states: “Online gambling made me lose everything”. Another narrator recounts a four-year journey through online gambling, initially under the misconception that gambling would lead to a better life: “Four years of online gambling, thinking it would bring good days”. Even more concerning are posts detailing how a youth, due to ignorance and curiosity about gambling, squandered all savings and plunged into deep debt: “A naive youth encountered online gambling, wasting all savings and incurring debts”.

Behind these deviant behaviors there often is the erroneous expectations individuals, blind optimism, and an excessive pursuit of immediate rewards. In the digital era, the prevalence and accessibility of online gambling might have amplified its inherent dangers, rendering young people more susceptible to its allure.

4.2.2. The Structural Risks of Youth Indebtedness

The profound economic repercussions of the COVID 19 pandemic have been widely acknowledged by scholars internationally (Orlowski,2021). Significant public health crises, such as the current epidemic COVID 19 in China, have markedly influenced the financial status of young individuals, particularly those in already precarious economic positions. This situation has led to interruptions in their financial stability, thereby exacerbating levels of indebtedness. The rise in debt levels is not merely a direct result of income reductions due to the pandemic, but also a reflection of the amplification of structural risks within the pandemic context. These risks are further intensified by pre-existing economic practices and consumption patterns, exemplified by behaviors such as: “lack of moderation in consumption post-university graduation”. When these entrenched economic habits intersect with the pandemic’s impact, they significantly heighten the financial risks for individuals.

This paper additionally identifies that many young Chinese individuals are grappling with income uncertainty and risk within today’s intricate economic landscape. Income risk is multifaceted, originating from various structural socio-economic factors. A salient aspect contributing to this is the highly competitive nature of the current labor market in China, coupled with a scarcity of job opportunities. The youth, particularly those individuals entering the workforce for the first time, are more susceptible to economic instabilities. Income-related risks often emerge from abrupt shifts in the macroeconomic climate, exemplified by work stoppages and disruptions in salary.

For instance, there are cases of individuals who have already accrued debt owing to job insecurity and medical expenses, and they then resort to loans for everyday expenses. The advent of the pandemic disrupts their plans unexpectedly, hindering their ability to return to work promptly, and causing rapid debt accumulation. Such scenarios highlight how individuals, even those with stable employment in normal economic conditions, can encounter substantial financial strain due to unforeseen events.

The expansion of digitalized financial services has led to an increased dependency among many consumers on unconventional financial instruments. In the modern consumer society, the practice of “using a loan to pay off another loan” has become a normalized behavior among numerous young indebted individuals. This phenomenon is not merely a consequence of individual consumer decision-making errors, but is shaped within the broader macro-socio-economic structure. Confronted with cash flow challenges, this reliance intensifies, leading many to embark on a perilous cycle of acquiring new loans to settle existing loans, thus perpetuating a destructive pattern of debt accumulation.

Financial platforms, with their strategies of enticing users through low prices and discounts, have significantly bolstered the propensity of young people to incur debt. However, the transparency of these financial instruments is often lacking. For instance, platforms may only display daily interest rates, obscuring the fact that the annual interest rate could be as high as 14.6%. This obscurity in financial strategies frequently causes consumers to underestimate the true cost of borrowing, thereby increasing their susceptibility to falling deeper into debt.

Financial scams have increasingly become a pivotal factor contributing to the over-indebtedness of many youth groups. These scams exploit the reliance of the youth on digital financial instruments and their lack of awareness about associated risks, rendering them susceptible to online fraud. Furthermore, the interplay between fraudulent activities and an unstable job market intensifies this vulnerability. Encountering financial scams during the job-hunting process, combined with the dire need for stable income, heightens the likelihood of young people falling prey to such frauds. Moreover, victims frequently face challenges in recuperating their losses, which aggravates their financial strain. The widespread occurrence of financial fraud underscores the vulnerability of the contemporary financial system and the absence of adequate safeguards for young consumers. This situation also reflects broader macroeconomic and political dynamics that, to a certain extent, either tolerate or indirectly contribute to the proliferation of financial fraud.

Table 1.

Hierarchical Coding of Structural and Individual Factors.

Table 1.

Hierarchical Coding of Structural and Individual Factors.

| Primary Attribution |

Secondary Attribution |

Tertiary Attribution |

| Structural Factors |

Social Risks

n=551; Proportion:22.80% |

Major Public Health Event |

Income Risks

n=652; Proportion:26.98% |

Unpaid Wages |

| Unemployment |

| Job Instability |

Debt-fueled Debt

n=929; Proportion:38.44% |

Debt-fueled Debt |

Financial Fraud

n=291; Proportion:12.04% |

Financial Fraud |

| Individual Attribution |

Investment Debt

n=315; Proportion:13.03% |

Financial Investment |

Entrepreneurial Debt

n=462; Proportion:19.11% |

Business Debt |

| Business Failure |

Subsistence Debt

n=881; Proportion:36.45% |

Daily expenses |

| Medical Expenses |

| Home and Car Loans |

Social Obligation Debt

n=171; Proportion:7.07% |

Friends and Family Loans |

Academic Debt

n=128; Proportion:5.30% |

Student Loan |

| Training and Certification |

Consumer Debt

n=807; Proportion:33.39% |

Overspending |

| Excessive consumption |

Deviant Debt

n=181; Proportion:7.49% |

Gambling |

4.3. Individuality and Structural Spiral of Indebtedness in Youth Groups

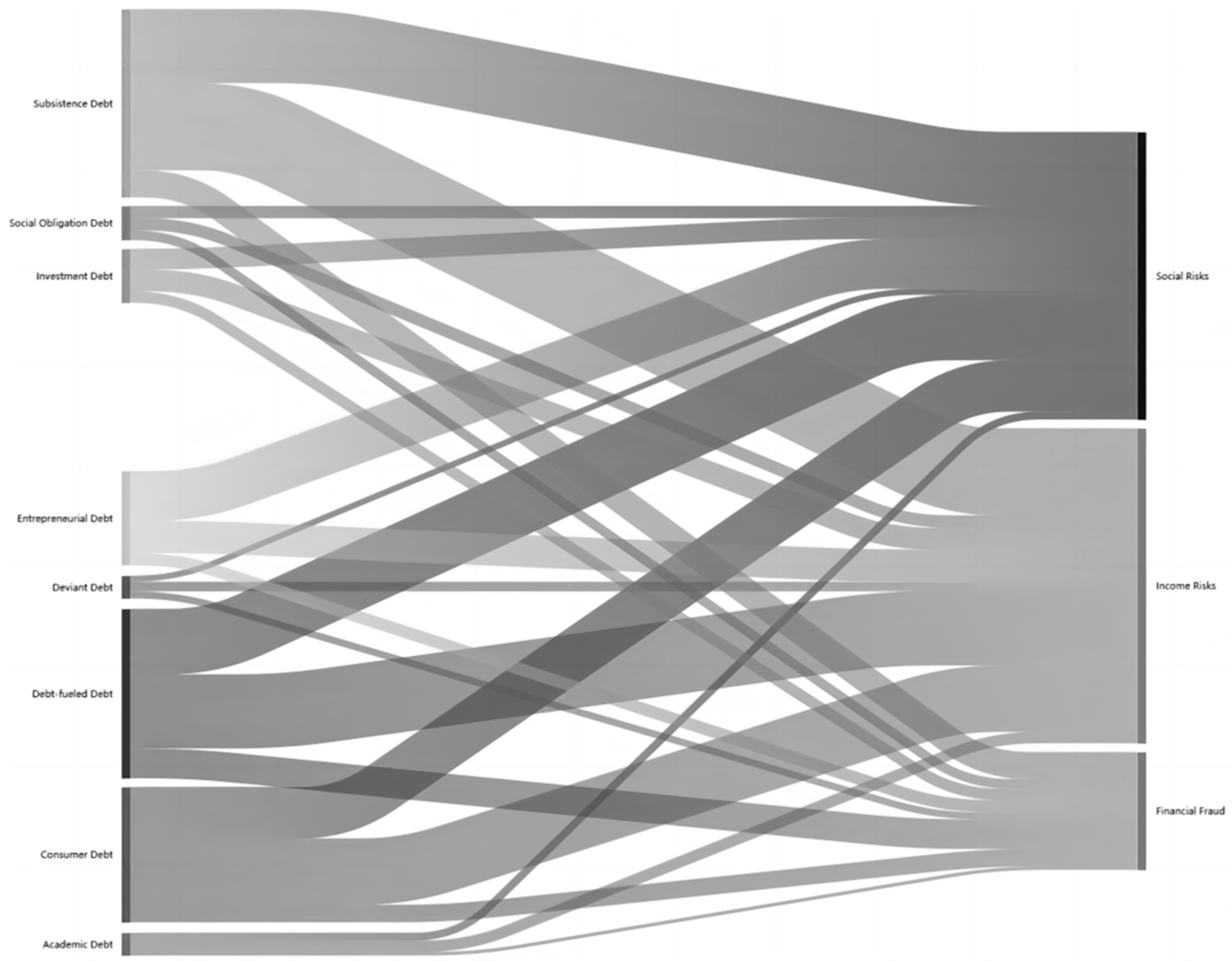

The Sankey diagram presented in

Figure 2 elucidates the interconnectedness and flow between structural risks and individual causes of youth indebtedness. Building upon our preceding discussion on the financial burdens of this demographic, we delve deeper into the intertwined individual and structural dynamics of youth indebtedness. The liberalization of financial markets and the diversification of credit forms have catalyzed the integration of credit into consumption patterns. This is evident in various financial platforms, from installment shopping platforms tailored for college students to traditional e-commerce sites offering P2P online loans, which have brought unparalleled convenience to the youth.

For instance, the emergence of online borrowing platforms has expanded borrowing avenues. However, the widespread accessibility of finance has concurrently escalated levels of indebtedness. A common trend observed is: “Most popular apps, whether for online shopping, ordering takeout, taking a taxi, or even for work-related or sports activities, now incorporate online lending functions”. This aligns with the consumption tendencies of young individuals, particularly those in the early stages of their careers, who often display a robust desire to consume, but possess limited payment capacity.

Nevertheless, some informal online lending platforms employ deceptive practices, luring consumers with a ‘low threshold’ while concealing actual risks. These platforms engage in illicit lending and loan extraction under the guise of banking institutions, lacking bank credit qualifications and following non-compliance with regulatory requirements, such as implementing a fund depository. This highlights the shortcomings of administrative oversight. For example, one post narrates: “Unable to repay on the due date, the salesperson suggested another platform. I used this new platform to pay off the previous debt, only to later discover that all these platforms were operated by the same company under different app guises, entrapping me in their scheme”.

Structural risk not only precipitates a direct loss of income for individuals but also impairs their economic mobility. This is exemplified by a graduate’s experience, where an initial plan to attend graduate school was thwarted, followed by an attempt to rejoin the workforce, only to be interrupted by the epidemic. This led to a disruption in income, compelling the graduate to resort to internet loans to meet basic needs. By the time re-employment was secured, and necessary expenses such as rent and living costs arose, the initial debt had significantly compounded.

The graduate elaborates: “Initially, my credit limit wasn’t high, so I took out three online loans and also had a few thousand ‘dollars’ in credit card debt, marking the start of my journey into debt. At that time, I had a reasonable repayment plan based on my then-stable salary. It seemed feasible to make monthly payments, but often plans don’t keep pace with changes, and unexpected factors arose! My repayment plan completely fell apart!”. This cycle of “using a loan to pay off another loan” has further deepened the indebtedness of young individuals, ensnaring them in a debt spiral that is challenging to escape.

Structural risks not only induce immediate financial shocks for many, but also they intensify indebtedness due to various other factors. Interactions between social values, personal aspirations, and precarious living conditions, compounded by the epidemic, have further complicated the economic struggles of individuals. For instance, one individual borrowed money for an internship at a large company, but was unable to secure permanent employment afterward due to the recession and employment challenges wrought by the epidemic. Moreover, societal and familial expectations led him to conceal his true debt situation from his family, exacerbating his financial burden.

There is a prevailing tendency to perceive debt, particularly consumer loans, as an individual issue. Some studies indicate a growing neoliberal viewpoint permeating all aspects of life (diLeonardo, 2008). This neoliberal stance attributes individuals’ financial troubles to their irresponsibility. However, attributing excessive blame to individuals for deviant consumer behavior detaches indebtedness from the broader context of socio-economic inequality, and embeds it within neoliberal discourse. It has been argued, in a Finnish study by Autio et al. (2009) and an American study by Dwyer (2018), that widespread financial sector deregulation, alongside predatory and fringe banking practices, has facilitated easy access to financial resources for individuals. For example, a post narrates: “On a Borrowing App, I unknowingly applied for a 50,000-Yen loan that was surprisingly approved. I was instructed to bring my bank card and ID for processing, only to discover a 20% processing fee upon arrival”.

The

Table 2 shows the total group size for each primary category, indicating the magnitude of each debt type or risk category. For example, "Subsistence Debt" has the highest group size (881), suggesting it is a common form of debt. The numbers and proportions indicate the overlap or co-occurrence among different risk factors. For example, there is a significant overlap between "Subsistence Debt" and "Income Risks" (305 cases, 0.25), suggesting that individuals with income risks are more likely to experience subsistence debt.“Debt-Fueled Debt”category has the most connections to other forms of debt, such as "Income Risks" (258 cases, 0.20) and "Social Risks" (229 cases, 0.19). This could suggest a strong correlation between debt-fueled debt and multiple types of risk factors. Some connections are less prevalent but noteworthy. For instance, "Academic Debt" has a relatively low group size (128), with lower proportions of co-occurrence with other risks, suggesting it might be less common or occur in isolation. Several risk factors overlap with multiple debt types. "Social Risks" and "Income Risks" show connections with most forms of debt, indicating that these risks can be broadly distributed among different debt types. Overall, the analysis demonstrates a complex web of connections and co-occurrences among various debt types and risk factors, providing insights into their interdependencies.

In summary, the issue of youth indebtedness stems from a confluence of individual and structural factors. The disparity between individuals’ consumption desires and their payment capacities, structural financial enticements, and the neoliberal consumption ethos are significant contributors to this issue. Addressing this problem necessitates, not just enhancing financial literacy education at the individual level and improving consumer self-management capabilities, but also effectively regulating the financial market at the structural level to curb excessive financial temptations and safeguard the consumer rights and interests of the youth.

5. Conclusions

The conclusions of this study are multifaceted. First, the increasing debt burden among the youth is intricately linked, not just to individual-level irrational consumption behaviors within a consumerist context, but also to the economic activities of young people during specific stages of their life cycle. Second, from a structural risk perspective, youth indebtedness is connected not only to significant socio-economic risks, but also to the evolution of socio-financial digitization and the normalization of credit practices. Lastly, the escalating issue of youth indebtedness is attributable to a combination of individual factors and structural dynamics. These include the unique life circumstances of young people at various life course stages, the probability of encountering unexpected events, and a lack of financial literacy. Additionally, factors such as a precarious position in the labor market, risks stemming from major public safety incidents, and the creation of a “debt spiral” facilitated by financial digitalization and the standardization of credit practices also play crucial roles.

In light of these identified challenges, it is evidently unrealistic to expect young individuals to navigate these economic vulnerabilities through solely personal strategies. This scenario underscores the deficiencies in the current Chinese social welfare system. Consequently, there is an urgent need to enhance the Chinese social security framework. The goal should be to establish a comprehensive and universally inclusive social security system that integrates urban and rural coverage, delineates clear roles and responsibilities, and ensures sustainability and viability across multiple levels. Strengthening health insurance and unemployment benefits is also crucial.

Additionally, in the face of structural shifts in credit markets in recent years, relying solely on individual-level efforts proves inadequate. Systemic interventions are imperative, including bolstering the regulation of credit platforms, refining relevant laws and regulations, and formulating effective and efficient punitive mechanisms. Currently, China’s financial regulatory system exhibits significant shortcomings, chiefly manifested in the fragmented nature of administrative regulatory bodies, outdated legal norms, a disconnect between administrative oversight and industry self-regulation, and the absence of effective regulatory standards for innovative financial products.

Particularly in the realm of Internet finance, despite the introduction of numerous rules and regulations, the existing legal framework falls short of comprehensively encompassing the nascent domain of Internet lending. This gap results in inconsistencies and a lack of cohesion in the practical implementation of relevant policies, necessitating an urgent call for reform and better alignment of regulations with the evolving financial landscape.

In light of the challenges posed by insufficient financial literacy among the youth, there is an urgent need for a multifaceted approach to address this issue. Financial institutions have a pivotal role in innovating and expanding access to financial services. They must aim to simplify procedures and offer reasonable interest rates to meet the credit needs of young people, thereby supporting their economic participation.

Equally crucial is the state’s role in enhancing legal and policy frameworks governing these institutions. However, beyond regulatory measures, a significant focus must be placed on elevating the financial literacy of college students. This demographic, often vulnerable to making impulsive financial decisions, typically lacks the necessary awareness and skills for informed decision-making. For example, as highlighted in some studies, students can accumulate substantial debt due to poor financial choices stemming from inadequate literacy. The case studies of Disney and Gathergood (2013), based in the UK, underscore this predicament. They illustrate how low financial literacy leads to excessive loan costs and default risks, as consumers struggle to navigate and understand their financial options. To counter these trends, an all-encompassing approach is needed. The state, in collaboration with various societal sectors, should leverage the Internet and other media platforms to expand the reach of financial education. Such efforts are imperative, not just to curb poor financial decisions like impulsive spending and online gambling, but also to enhance young consumers’ overall financial acumen.

In conclusion, the journey toward financial literacy for the youth is a collaborative effort requiring the involvement of financial institutions, policy-makers, and educational bodies. Together, they can forge a path that equips young individuals with the knowledge and skills needed for sound financial decision-making, thereby securing their future economic well-being and contribution to society.

In the contemporary societal milieu, as discussed in this paper, young individuals face heightened risks of financial victimization, manifesting in over-indebtedness, compulsive consumption habits, and detrimental financial decisions. This predicament extends beyond mere financial duress, often leading to profound psychological impacts, including depression, anxiety, and diminished self-worth. As highlighted by Sweet et al. (2018), indebtedness frequently induces negative self-perceptions, such as guilt and a sense of failure, which are reinforced by prevailing neoliberal ideologies. This not only exacerbates the individual’s financial troubles, but also perpetuates a cycle of self-blame and despair.

However, it is imperative to recognize that financial victimization is not solely a result of individual choices, but also a consequence of broader structural issues. These include the intricacies of the financial system, the design of financial products, and societal risk perceptions. The neoliberal ethos of financial responsibility has significantly influenced young people’s financial behaviors and psychological states, making financial aggression a complex social issue intertwined with cultural and psychological dimensions.

Addressing this challenge requires a comprehensive and multi-pronged approach, with social work playing a pivotal role. Social workers are uniquely positioned to offer psychological crisis intervention to young victims of financial abuse. They can assist in restoring mental health through counseling, emotional regulation, and psychoeducation, thereby helping individuals recover and regain self-esteem and confidence. Beyond individual mental health, social workers also contribute to the broader societal health and stability by mitigating the impacts of financial aggression.

Moreover, early intervention in cases of addictive consumption and other financial issues is vital. It not only aids young people in recognizing and altering harmful behaviors, but also averts more significant financial crises. This preventive strategy focuses on enhancing risk awareness and financial literacy among the youth, thereby forestalling future losses and safeguarding their well-being.

In conclusion, the menace of financial victimization among youth calls for a concerted effort from social workers and other stakeholders. By addressing both the psychological trauma and the underlying societal factors, we can forge a path towards a financially stable and psychologically healthy future for our young generation.

References

- Achtziger, A., Hubert, M., Kenning, P., Raab, G., & Reisch, L. (2015). Debt out of control: The links between self-control, compulsive buying, and real debts. Journal of Economic Psychology, 49, 141-149. [CrossRef]

- Anderloni, L., Bacchiocchi, E. & Vandone, D. (2012). Household financial vulnerability: An empirical analysis. Research in Economics, 66(3), 284-296. [CrossRef]

- Ando, A., & Modigliani, F. (1963). The ‘life cycle’ hypothesis of saving: Aggregate implications and tests. The American Economic Review, 53(1), 55-84.

- Autio, M., Wilska, T. A., Kaartinen, R., & Lähteenmaa, J. (2009). The use of small instant loans among young adults: A gateway to a consumer insolvency? International Journal of Consumer Studies, 33(4), 407-415.

- Białowolski, P., Węziak-Białowolska, D., & VanderWeele, T. J. (2019). The impact of savings and credit on health and health behaviours: An outcome-wide longitudinal approach. International Journal of Public Health, 64(4), 573-584. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. R., & Hercowitz, Z. (2009). Welfare implications of the transition to high household debt. Journal of Monetary Economics, 56(1), 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Di Leonardo, M. (2008). The neoliberalization of minds, space, and bodies: Rising global inequality and the shifting American public sphere. In J. L. Collins, M. Di Leonardo, & B. Williams (Eds.), New landscapes of inequality: Neoliberalism and the erosion of democracy in America. Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press.

- Disney, R., & Gathergood, J. (2013). Financial literacy and consumer credit portfolios. Journal of Banking and Finance, 37, 2246-2254. [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, H., & Bond, R. (2010). I want it and I want it now: Using a temporal discounting paradigm to examine predictors of consumer impulsivity. British Journal of Psychology, 101, 751-776. [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, R. E. (2018). Credit, debt, and inequality. Annual Review of Sociology, 44, 237-261.

- Dwyer, R. E., McCloud, L., & Hodson, R. (2012). Debt and graduation from American universities. Social Forces, 90(4), 1133–1155. [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, R. E., McCloud, L., & Hodson, R. (2011). Youth debt, mastery, and self-esteem: Class-stratified effects of indebtedness on self-concept. Social Science Research, 40(3), 727-741. [CrossRef]

- ECRI. (2017). Lending to households and non-financial corporations in Europe, 1995–2016. Statistical Package, August.

- FINRA. (2013). Financial capability in the United States: Report of findings from the 2012 National Financial Capability Study. Washington, DC: FINRA.

- Fook, L., & McNeill, L. (2020). Click to buy: The impact of retail credit on over-consumption in the online environment. Sustainability, 12(7322). [CrossRef]

- Friedline, T., & Song, H. (2013). Accumulating assets, debts in young adulthood: Children as potential future investors. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(9), 1486–1502. [CrossRef]

- Gani, A. (2022). From fashion to food, Brits using fast credit to stretch budgets. Bloomberg UK. Retrieved November 1, 2022, from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-08-23/from-fashion-to-foodbrits-using-fast-credit-to-stretch-budgets.

- Gao YanJing. (2019). Invisible Poverty: a New Phenomenon of urban Youth--from the Perspective of inter-generational Change in Reforming Open for 40 Years. China Youth Study, 03,29-35+51.

- Gonzalez, A. (2008). Microfinance, incentives to repay, and overindebtedness: Evidence from a household survey in Bolivia (Doctoral dissertation). The Ohio State University.

- Hardgrove, A., Rootham, E., & McDowell, L. (2015). Possible selves in a precarious labour market: Youth, imagined futures, and transitions to work in the UK. Geoforum, 60, 163-171. [CrossRef]

- Hohnen, P., Gram, M., & Jakobsen, T. B. (2020). Debt as the new credit or credit as the new debt? A cultural analysis of credit consumption among Danish young adults. Journal of Youth Studies, 23(3), 356-370. [CrossRef]

- Houle, J. N., & Berger, L. (2017). Children with disabilities and trajectories of parents’ unsecured debt across the life course. Social Science Research, 64, 184–196. [CrossRef]

- Houle, J. N. (2014). A generation indebted: Young adult debt across three cohorts. Social Problems, 61(3), 448–465.

- Lachance, M. J., Beaudoin, P., & Robitaille, J. (2006). Quebec young adults’ use of and knowledge of credit. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 30(4), 347-359. [CrossRef]

- Lea, S. E. (2021). Debt and overindebtedness: Psychological evidence and its policy implications. Social Issues and Policy Review, 15(1), 146-179. [CrossRef]

- Li, J. J., Jiao, C., Nicholas, S., Wang, J., Chen, G., & Chang, J. H. (2020). Impact of medical debt on the financial welfare of middle- and low-income families across China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 4597. [CrossRef]

- Limerick, L., & Peltier, J. (2014). The effects of self-control failures on risky credit card usage. Marketing Management Journal, 24, 149–161.

- McCloud, L., & Dwyer, R. E. (2011). The fragile American: Hardship and financial troubles in the 21st century. Sociological Quarterly, 52, 13–35. [CrossRef]

- McNeill, L. S. (2014). The place of debt in establishing identity and self-worth in transitional life phases: Young home leavers and credit. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38(1), 69-74. [CrossRef]

- Meier, S., & Sprenger, C. (2010). Present-biased preferences and credit card borrowing. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2, 193-201. [CrossRef]

- Modigliani, F., & Brumberg, R. (1954). Utility analysis and the consumption function: An interpretation of cross-section data. In K. K. Kurihara (Ed.), Post-Keynesian Economics (pp. 388-436). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- The Money Charity. (2023). The Money Statistics: January 2023. Retrieved February 1, 2023, from https://themoneycharity.org.uk/money-statistics/.

- OECD. (2020). OECD/INFE 2020 International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/financial/education/launchoftheoecdinfeglobalfinancialliteracysurveyreport.htm.

- Oksanen, A., Aaltonen, M., & Rantala, K. (2016). Debt problems and life transitions: A register-based panel study of Finnish young people. Journal of Youth Studies, 19(9), 1184-1203. [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, A., Aaltonen, M., & Kivivuori, J. (2015). Driving under the influence as a turning point? A register-based study on financial and social consequences among first-time male offenders. Addiction, 110(3), 471–478. [CrossRef]

- Robson, J., Farquhar, J. D., & Hindle, C. (2017). Working up a debt: Students as vulnerable consumers. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 27(2), 274–289. [CrossRef]

- Short, J. C., McKenny, A. F., & Reid, S. W. (2018). More than words? Computer-aided text analysis in organizational behavior and psychology research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 415-435. [CrossRef]

- Sweet, E., Kuzawa, C. W., & McDade, T. W. (2018). Short-term lending: Payday loans as risk factors for anxiety, inflammation, and poor health. SSM - Population Health, 5, 114-121. [CrossRef]

- Williams, B. (2005). Debt for sale: A social history of the credit trap. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. [CrossRef]

- Yabroff, K. R., Zhao, J. X., Han, X. S., & Zheng, Z. Y. (2019). Prevalence and correlates of medical financial hardship in the USA. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 34, 1494–1502. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).