1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of financial technology (FinTech) has transformed how consumers access and interact with credit markets. Digital platforms offering peer-to-peer lending, mobile-based credit, and pay-later services now serve as major alternatives to traditional banking, particularly for individuals with limited access to formal credit channels [

1,

2]. By leveraging big data, artificial intelligence, and alternative credit scoring models, FinTech lenders have broadened access to financing and improved credit risk evaluation, especially for those who have historically been underserved by conventional financial institutions [

3,

4].

In emerging economies like Indonesia, FinTech-based lending is not only growing rapidly but also redefining how consumers borrow. Between 2023 and 2024, online loan disbursements rose by more than 29%, reaching IDR 77.02 trillion, with over 18 million active borrowers recorded nationwide [

5,

6]. Popular platforms such as Shopee PayLater, Kredivo, and Akulaku are particularly attractive to middle-income groups, offering convenience, minimal paperwork, and instant credit approval [

7]. These features have helped FinTech products gain widespread adoption, especially among urban millennials and salaried employees [

8,

9].

However, the growing accessibility of digital loans has raised concerns about consumer indebtedness and financial vulnerability. Empirical evidence indicates that many FinTech borrowers exhibit risky financial behavior, including frequent late payments, high debt-to-income ratios, and poor credit discipline [

3,

10]. Because of their simplicity and speed, FinTech credit products can appeal to individuals prone to impulsive consumption, limited budgeting skills, or emotional decision-making, potentially leading to unsustainable borrowing [

11,

12].

This behavioral shift reflects what scholars term a propensity to indebtedness, a tendency to take on debt not necessarily due to financial necessity, but due to behavioral and psychological triggers such as emotional gratification, materialistic aspirations, and cognitive biases [

13,

14,

15]. In FinTech environments, these tendencies can be intensified by persuasive design, personalized marketing, and frictionless loan processes [

16,

17]. Over time, this may create a population of repeat borrowers whose financial decisions are shaped more by affect and convenience than by careful planning.

Although the issue of debt has been widely studied, most research to date focuses on traditional credit products such as credit cards or bank loans [

18,

19]. There is limited literature that specifically examines debt-related behavior in FinTech-based lending contexts, particularly in developing countries. Studies that do explore this space tend to concentrate on loan adoption behavior, platform trust, or repayment performance [

20,

21,

22], rather than the behavioral predisposition toward digital borrowing itself.

Moreover, despite the growing discourse on behavioral finance, few studies have explored how individual-level characteristics such as financial literacy, job security, and religiosity moderate the relationship between psychological factors and FinTech borrowing behavior. While some evidence suggests these factors influence financial choices, their moderating role in the context of propensity to indebtedness in FinTech-based loans remains underexplored. This represents a significant gap in the literature, especially in rapidly digitizing economies where FinTech credit is widely adopted but poorly regulated.

To address these gaps, this study investigates the determinants of the propensity to indebtedness among Indonesian users of FinTech-based loans. It specifically explores how behavioral biases, emotions, culture, and materialism influence individuals’ borrowing tendencies. Furthermore, it examines whether financial literacy, perceived job security, and religiosity moderate these relationships. The study focuses on civil servants and private employees/self-employed workers, a relevant population as they often have fixed incomes and are primary targets of FinTech lenders.

This research provides several theoretical contributions. First, it extends the existing literature on consumer credit by applying behavioral finance and socio-psychological theories to the context of digital lending. Second, it introduces the concept of propensity to indebtedness into the FinTech space, an area where this construct has received little attention. Third, it integrates individual differences (e.g., financial literacy, religiosity) as moderators, enhancing the explanatory power of behavioral models of indebtedness in digital environments. Additionally, by focusing on Indonesia, one of the fastest-growing FinTech markets in Southeast Asia, this study contributes regionally relevant insights to the broader global discourse on FinTech adoption and behavioral risk in emerging economies.

In terms of practical contributions, the study offers insights for policymakers, FinTech developers, and financial educators. For regulators, understanding the behavioral drivers of debt can inform the development of consumer protection policies tailored to digital lending. For FinTech firms, the findings can support more responsible product design, one that balances accessibility with safeguards against risky borrowing. For educators and financial institutions, the study emphasizes the importance of targeted literacy programs, particularly for populations vulnerable to impulsive or emotionally-driven borrowing behavior.

In summary, while FinTech credit solutions offer powerful tools for financial inclusion, they also carry behavioral risks that are not yet fully understood. By examining the drivers of fintech-related indebtedness, this study seeks to inform both academic understanding and practical interventions that promote more responsible financial behavior in the digital era.

2. Literature Review

2.1. FinTech-Based Loan

The rapid digitalization of financial services has led to the emergence of financial technology (FinTech), a term that encapsulates innovations at the intersection of finance and technology [

23]. FinTech-based loans, in particular, have redefined how credit is accessed and delivered by offering faster, more convenient, and algorithm-driven lending solutions. These platforms leverage big data, artificial intelligence, and mobile infrastructure to simplify application processes and improve loan approval efficiency [

24]. Compared to traditional banks, FinTech lenders offer streamlined alternatives, minimizing bureaucratic friction and paperwork [

11].

A key distinction of FinTech lending lies in its use of alternative, nontraditional data such as online activity, purchase history, and even smartphone metadata to assess creditworthiness [

24,

25]. This allows lenders to create a more holistic borrower profile than traditional credit scoring methods and identify viable borrowers previously excluded from formal credit systems [

26]. Consequently, FinTech has contributed to increasing credit penetration among underserved populations, including those in rural or economically marginalized areas [

27].

While these innovations enhance financial access, they also raise important challenges. The use of automated credit scoring and opaque algorithms introduces risks related to data privacy, borrower profiling, and potential discrimination [

28]. In some markets, elevated default rates, especially for short-term or unsecured loans, suggest a need for stronger risk management frameworks [

29]. Additionally, digital borrowers may lack adequate financial knowledge, making them more susceptible to over-borrowing and debt accumulation [

10,

27].

Recent studies have begun to explore FinTech’s broader economic and social effects, including its complementary role to traditional banks, and its association with regional development, credit availability, and financial risk [

30,

31]. However, limited attention has been paid to the behavioral and psychological mechanisms that drive borrowing in FinTech environments. Understanding these factors, particularly the propensity to incur debt in digital settings, is essential to ensure responsible lending practices and to mitigate the financial vulnerabilities that may emerge alongside FinTech expansion.

2.2. Financial Behavior Bias

Behavioral finance has become increasingly important in explaining why individuals often make financial decisions that deviate from rational expectations. Rather than always acting in accordance with utility-maximizing principles, individuals frequently rely on mental shortcuts and are influenced by psychological factors that distort their judgment, especially in contexts involving risk and uncertainty [

32,

33]. These distortions, rooted in cognitive and emotional biases, can significantly affect individuals’ financial behaviors, particularly in lending and borrowing decisions [

34].

One such bias is overconfidence, a tendency in which individuals overestimate their financial knowledge or control over outcomes. This bias may cause borrowers to underestimate the risks of indebtedness or to believe they can easily manage repayments despite limited income or unstable job conditions [

33,

35]. Overconfident individuals may disregard critical loan details and take on excessive debt under the false assumption that future circumstances will remain favorable [

33].

Another significant behavioral tendency influencing financial decision-making is herding behavior. This occurs when individuals follow the financial choices of others, such as peers or social media influencers, rather than relying on independent judgment [

27]. In digital environments where information spreads rapidly and borrowing is made convenient, herding can lead to mass participation in lending platforms without adequate assessment of personal financial capacity or loan risk [

35]. Herding amplifies impulsive borrowing, especially when fintech services are perceived as trendy or widely adopted.

These behavioral patterns are closely linked to individuals’ propensity to become indebted. People with low self-regulation or high susceptibility to emotional gratification may be more likely to borrow for immediate consumption without considering the long-term implications [

34,

36]. Empirical evidence has shown that behavioral biases significantly contribute to suboptimal borrowing behaviors and increasing debt burdens, especially among younger populations and those with limited financial capability [

34].

The proliferation of FinTech-based loans further amplifies the impact of these biases. The speed, ease, and low entry barriers associated with digital lending can reduce critical reflection and increase borrowing based on emotional triggers or peer influence [

27]. Moreover, the intention to continue using FinTech credit is often shaped more by internal psychological factors, such as enjoyment and perceived control, than by rational assessments of cost or repayment capacity [

11]. This reinforces a feedback loop in which behavioral biases sustain ongoing borrowing behavior.

2.3. Culture

Culture plays a foundational role in shaping individual financial behavior, including decisions around borrowing and debt. As a set of shared values, beliefs, and behavioral norms, culture influences how individuals perceive money, credit, and risk [

37]. These cultural influences are not only reflected in broad societal attitudes but also manifest in individual decision-making processes related to financial obligations and consumption preferences [

38].

Research has shown that personal cultural orientations, such as individualism, collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, and long-term orientation, significantly affect financial behavior and vulnerability. For example, individuals with an idiocentric (individualist) orientation tend to have a long-term financial focus, which reduces impulsive spending and risky indebtedness debt [

39]. In contrast, those with allocentric (collectivist) values, especially when combined with high uncertainty avoidance and masculinity, are more likely to engage in impulsive purchases and accumulate debt [

39]. These orientations shape how people manage financial resources, evaluate risk, and respond to credit offerings.

In the context of FinTech lending, cultural background may also moderate consumers’ continuance intentions. Bergmann et al. [

11] found that users from different cultural settings demonstrate varying satisfaction and trust levels in FinTech services, suggesting that firms must tailor their digital lending strategies to align with regional values, socio-economic conditions, and digital maturity. In regions where digital financial literacy is low or where there is cultural skepticism toward debt, more effort is required to build trust and ensure responsible borrowing.

Historical and institutional contexts also reflect the cultural evolution of credit behavior. For instance, in Protestant-dominated cultures, negative attitudes toward debt shaped legal and financial systems to favor creditors, which led to the expansion of credit access and, paradoxically, higher levels of indebtedness among households [

40]. Similarly, Latin American cultures, characterized by strong familial collectivism (familismo), often view borrowing as a means to fulfill family obligations, influencing attitudes toward debt acceptance and usage [

41].

Studies have also found significant cultural differences in attitudes toward indebtedness. For example, East Asians tend to experience stronger feelings of indebtedness and social obligation compared to Western cultures, a reflection of their more relational approach to financial support and borrowing [

42]. In Switzerland, culturally shaped views of money, such as seeing it as a source of prestige or a tool for social power, were associated with higher indebtedness, while a culture of economical financial management was linked to reduced financial distress [

43].

2.4. Emotions

Emotions are complex psychological and physiological states that influence human behavior, including financial decision-making. They involve affective responses rooted in personal experiences, neurobiological processes, and situational contexts [

44,

45]. Rather than being isolated or purely irrational forces, emotions can interact with cognitive mechanisms to shape judgments, evaluations, and behavior under uncertainty [

14]. In the context of finance, emotions are particularly relevant given the high stakes and uncertainty involved in borrowing, lending, and managing personal debt [

46].

Recent studies have highlighted that emotions, both positive and negative, significantly influence decisions to take on debt, especially in fintech-based lending environments. Zhou et al. [

9] found that negative emotions, such as anger, serve as strong predictors of borrower default, with a U-shaped relationship indicating that both low and high levels of anger increase the likelihood of non-repayment. These emotional patterns suggest that feelings experienced during or before the loan approval stage can serve as early indicators of risk. Similarly, Marston et al. [

47] observed that emotional considerations, such as avoiding judgment or institutional shame, can shape low-income individuals’ preferences for certain types of credit over others.

While some emotions lead to risky financial behavior, others prompt caution. For instance, Flores and Vieira [

48] found that individuals experiencing heightened negative emotions tended to reduce their indebtedness, likely as a coping strategy to restore emotional well-being. Conversely, Waqas and Siddiqui [

49] reported that emotional responses could act in opposing directions: while some negative social emotions decreased debt levels, others increased them. The inconsistency in these emotional impacts underscores the complexity of emotional influence on financial choices. Azma et al. [

13] further noted that emotions such as embarrassment, shame, and nervousness, often tied to social or cultural context, are significantly linked with a higher tendency toward borrowing, especially in environments where financial literacy is low and emotional awareness is unregulated.

Moreover, the emotional well-being of over-indebted individuals has been consistently found to be lower than those without significant debt burdens. Ferreira et al. [

50] demonstrated that consumers who are over-indebted experience more frequent and intense negative emotions, including stress and guilt, which tend to intensify as the day progresses. This aligns with findings by Rendall et al. [

51], who emphasized that debt-related decisions are not purely rational, but heavily shaped by emotional states such as guilt, excitement, and alertness. These emotions influence not only the decision to incur debt but also the management of repayments, with individuals in heightened emotional states more likely to engage in high-risk financial behaviors.

2.5. Materialism

Materialism is broadly defined as the value individuals place on the acquisition and possession of material goods, often regarding them as essential to life satisfaction and success [

52]. In contemporary society, especially in consumer-driven cultures, materialism has become deeply embedded as a lifestyle ideology, where personal fulfillment and social identity are closely linked with ownership and consumption [

53]. Richins [

15] emphasized that for highly materialistic individuals, acquiring goods is not only habitual but central to their lives, consuming substantial time, effort, and resources. This overemphasis on consumption often influences financial decision-making, especially when individuals prioritize immediate possession over long-term financial stability.

A significant body of literature has associated materialistic values with a greater likelihood of indebtedness. Rahman et al. [

18] found that individuals who strongly value material possessions tend to engage in spending behaviors that are poorly planned, increasing their propensity to take on debt. Similarly, Azma et al. [

13] reported that materialistic consumers are more inclined to accumulate debt because they pursue consumption as a form of gratification without fully evaluating their financial capacity. Flores and Vieira [

48] explained that habitual high consumption among materialists leads to a diminished perception of financial risk and a reduced sensitivity to the emotional burden of debt, making them more tolerant of over-indebtedness.

Moreover, empirical studies consistently demonstrate that materialism significantly predicts the amount of debt a person holds. Garðarsdóttir and Dittmar [

54] revealed that materialism is a stronger predictor of debt levels than either income or money management skills. Their findings also indicated that materialism is linked to financial anxiety, uncontrolled spending, and compulsive buying tendencies. Watson [

53] added that highly materialistic individuals are more likely to perceive themselves as spenders and hold more favorable views toward borrowing, particularly for discretionary consumption. This inclination toward debt is not merely a behavioral pattern but also reflects an underlying orientation toward immediate acquisition and low tolerance for delayed gratification [

52].

Recent research further suggests that materialism drives the use of novel credit facilities such as “buy now, pay later” schemes, intensifying impulsive and compulsive buying behaviors [

55]. Matos et al. [

56] found that individuals with higher levels of materialism tend to experience elevated debt levels due to the centrality of acquisition in their lives, often linking consumption to happiness, social status, or self-worth. While some studies like Waqas and Siddiqui [

49] acknowledge the moderating effect of education, indicating that higher educational levels may buffer the negative effects of materialism on debt propensity, the overarching consensus is that materialism plays a critical role in driving irresponsible borrowing behavior, especially in environments with easy access to credit.

2.6. Financial Literacy

Financial literacy is widely recognized as a crucial capability enabling individuals to make informed and responsible financial decisions. The OECD [

57] defines it as a combination of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors that allow people to achieve financial well-being. Practically, it involves the ability to manage budgets, plan for the future, and evaluate financial products effectively [

58]. Empirical studies consistently show that financially literate individuals are more likely to adopt prudent financial behaviors, while those with low literacy are more vulnerable to debt burdens and financial distress [

59].

Several studies suggest that financial literacy can mitigate the negative consequences of behavioral and emotional tendencies on financial outcomes. For instance, Adil et al. [

60] showed that financial literacy weakens the influence of overconfidence on investment decisions, while Potrich and Vieira [

61] found it reduces compulsive buying behaviors. Likewise, Tahir et al. [

62] reported that financial literacy improves financial well-being when combined with self-control and future-oriented decision-making. These findings indicate that literacy may serve as a “buffering factor” against biases, although prior research has not explicitly tested this role in the context of fintech-based indebtedness.

With respect to debt behavior, the evidence generally supports financial literacy as a protective mechanism. Waqas and Siddiqui [

49] observed that higher levels of literacy lower individuals’ tendency to borrow irresponsibly by improving their capacity to manage earnings and expenses. Mahdzan et al. [

63] documented that financial literacy is negatively associated with excessive credit card use, reflecting greater financial discipline. Similarly, Lebdaoui and Chetioui [

64] found that more financially literate consumers exhibit less favorable attitudes toward borrowing. Yet, other findings suggest that literacy alone may not always prevent indebtedness, implying that its effect could depend on contextual or moderating factors [

48].

In the digital finance environment, the scope of financial literacy has expanded to include digital competencies. Ravikumar et al. [

65] emphasize that digital financial literacy is vital for navigating fintech platforms responsibly, while Zaimovic et al. [

66] show that it enhances financial inclusion and resilience. Moreover, Aftab et al. [

67] highlight that financial literacy not only promotes fintech adoption but also helps consumers evaluate risks and avoid debt traps. This is particularly important since borrowers with limited financial knowledge are more susceptible to over-indebtedness through online loans [

10,

68].

Although prior studies have rarely modeled financial literacy as a moderator between financial behavior biases and indebtedness, theoretical reasoning suggests such a role is plausible. Owusu et al. [

69] found that literacy can counteract the negative relationship between indebtedness and saving, while Ngo and Nguyen [

70] showed that consumer knowledge facilitates more responsible fintech usage. Conversely, Galariotis and Monne [

71] argue that individuals with poor debt literacy may not even seek financial education, exacerbating their vulnerability. Taken together, this evidence indicates that financial literacy holds the potential to act as a moderating factor, reducing the influence of behavioral biases on fintech-based borrowing, a possibility that this study explores further.

2.7. Job Security

Job security has consistently been linked to individuals’ financial stability and debt behavior. Empirical studies show that workers in precarious or insecure jobs are more likely to default or experience financial distress, even when controlling for macroeconomic conditions and demographic profiles [

3,

72]. Similarly, part-time or contract-based workers face greater risks of over-indebtedness compared to those with stable employment, as unstable income streams reduce their ability to manage repayments [

73]. These findings confirm that employment insecurity constitutes a structural driver of financial vulnerability.

Beyond direct effects, job insecurity also influences psychological and behavioral dimensions of financial decision-making. Insecure workers often experience heightened financial anxiety and stress, which in turn undermine rational financial behavior [

74,

75]. Evidence further shows that job insecurity decreases precautionary savings [

76] and amplifies short-term financial pressures, making individuals more susceptible to risky borrowing or consumption patterns [

77,

78]. During crises such as COVID-19, job insecurity has been associated with increased reliance on FinTech loans, reflecting both necessity and constrained access to traditional credit channels [

1,

79].

Although prior studies demonstrate the significant impact of job security on indebtedness and financial well-being, limited attention has been given to its potential moderating role in behavioral finance contexts. Conceptually, job insecurity could either strengthen or weaken the influence of financial behavior biases on borrowing. For instance, individuals with high job insecurity may be more prone to herding tendencies in digital lending decisions, as uncertainty encourages reliance on peer behavior rather than personal judgment. Conversely, in contexts of high job security, the same biases may translate less directly into indebtedness because stable income provides a buffer against impulsive borrowing.

This suggests that job security is not merely an antecedent of debt behavior but may also act as a contextual condition that shapes how financial biases manifest in borrowing outcomes. However, to date, very few studies have empirically examined this moderating function, particularly in the case of FinTech-based loans. Addressing this gap is therefore essential to advance understanding of how labor market uncertainty interacts with behavioral biases in driving indebtedness

2.8. Religiosity

Religiosity is widely acknowledged as a determinant of financial behavior and debt aversion. Prior studies demonstrate that individuals with strong religious values are generally less inclined toward excessive borrowing, as debt is often perceived as a moral and spiritual burden [

63,

80]. Within the Islamic context, for example, borrowing is strongly discouraged due to prohibitions against riba (interest), shaping individuals’ attitudes to avoid unnecessary loans and to repay obligations promptly [

81]. Such findings highlight that religiosity can function as a protective factor against excessive indebtedness.

Beyond direct effects, religiosity has been shown to interact with psychological drivers such as materialism and emotions. For instance, Lebdaoui and Chetioui [

64] found that Islamic religiosity moderates the link between impulsiveness, materialism, and indebtedness: individuals with low religiosity are more likely to translate materialistic values into debt, whereas high religiosity buffers this relationship. Similarly, religiosity can influence emotion regulation, fostering adaptive strategies such as cognitive reappraisal and reducing maladaptive patterns like rumination or expressive suppression [

82,

83]. These mechanisms suggest that religiosity may weaken the emotional pathways that lead individuals toward impulsive borrowing or debt-driven consumption.

Nevertheless, the relationship is not always linear. Yeniaras [

84] showed that for certain groups, religiosity could indirectly reinforce status consumption, thereby intensifying the link between materialistic values and indebtedness. This highlights the dual nature of religiosity: while it can act as a constraint on excessive borrowing, under specific cultural or social conditions, it may amplify consumption behaviors linked to identity and status. These nuanced outcomes indicate that religiosity’s influence depends on both context and individual interpretation of religious values [

85].

Despite these insights, empirical investigations into religiosity as a moderator remain limited. Existing studies focus primarily on its direct role in shaping borrowing attitudes, but few have explicitly examined how religiosity conditions the effects of emotions and materialism on indebtedness, particularly within the FinTech lending context. This presents an important research opportunity: religiosity could serve as a key contextual factor that either restrains or amplifies behavioral drivers of debt, depending on how individuals integrate spiritual beliefs into their financial decision-making.

2.9. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

This study draws on three complementary theoretical perspectives: the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), and the Behavioral Life-Cycle Hypothesis (BLCH). TAM [

86] explains why individuals adopt new technology, emphasizing the roles of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use in shaping technology-related behavior. In the context of fintech loans, this framework highlights how digital lending platforms are likely to be embraced when borrowers perceive them as both convenient and beneficial.

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [

87] extends this perspective by linking attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control to behavioral intentions and actual decisions. Within FinTech borrowing, attitudes toward debt, cultural norms regarding borrowing, and perceived control over financial resources all contribute to an individual’s propensity to become indebted. This framework provides a strong basis for examining how financial behavior biases, cultural influences, emotional drivers, and materialistic tendencies may shape borrowing behaviors in digital lending environments.

The Behavioral Life-Cycle Hypothesis (BLCH), introduced by Shefrin and Thaler [

88], further enriches this analysis by emphasizing the psychological conflict between a forward-looking “planner” and an impulsive “doer.” Borrowing decisions in FinTech settings are often influenced by this tension, where the “doer” may respond to immediate consumption desires triggered by materialism or emotions, while the “planner” seeks to impose self-control. Moderating factors such as financial literacy, job security, and religiosity can empower the planner, strengthening an individual’s ability to resist short-term impulses and avoid excessive indebtedness.

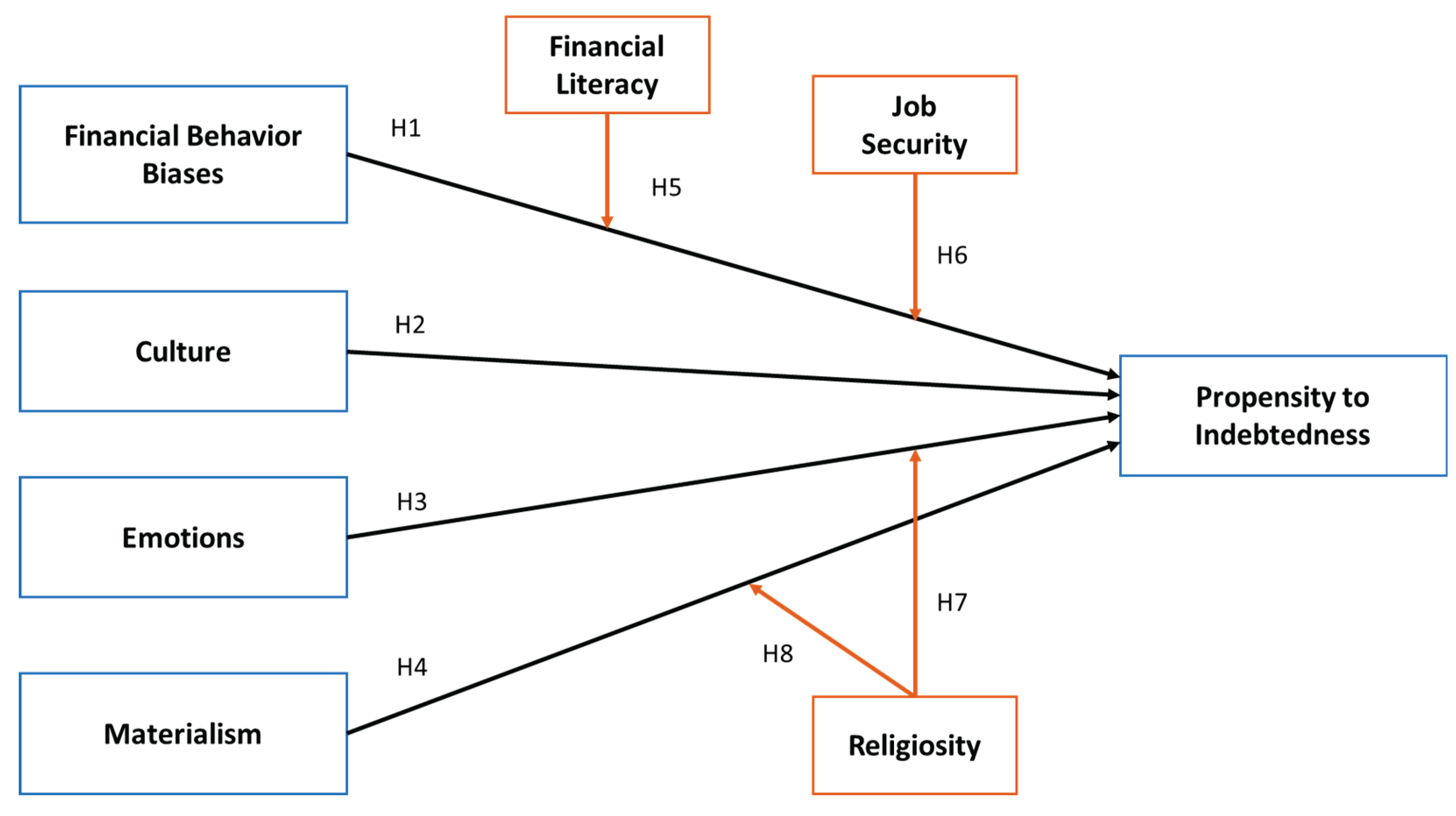

Taken together, these theories provide a holistic foundation for the proposed framework, in which fintech adoption is understood through TAM, psychological and social determinants of borrowing are captured by TPB, and the internal impulse–control struggle is explained by BLCH. The integration of these perspectives is illustrated in

Figure 1, which presents the research model linking financial behavior biases, culture, emotions, and materialism to the propensity to indebtedness, with financial literacy, job security, and religiosity as moderating variables. Based on this theoretical scaffolding, the study develops the following hypotheses:

H1. There is a positive relationship between financial behavior bias and the propensity to indebtedness in FinTech-based loans;

H2. There is a positive relationship between culture and the propensity to indebtedness in FinTech-based loans;

H3. There is a positive relationship between emotions and the propensity to indebtedness in FinTech-based loans;

H4. There is a positive relationship between materialism and the propensity to indebtedness in FinTech-based loans;

H5. Financial literacy moderates the relationship between financial behavior bias and the propensity to indebtedness in FinTech-based loans;

H6. Job security moderates the relationship between financial behavior bias and the pro-pensity to indebtedness in FinTech-based loans;

H7. Religiosity moderates the relationship between emotions and the propensity to indebtedness in FinTech-based loans;

H8.

Religiosity moderates the relationship between materialism and the propensity to indebtedness in FinTech-based loans.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

The primary data used in this study were collected through an online questionnaire distributed to respondents across Indonesia. The target population comprised civil servants, private employees, and self-employed workers. Using purposive sampling, 400 valid responses were obtained and analyzed.

The questionnaire items were adapted and developed from established studies in behavioral finance, psychology, and cultural research, as summarized in

Table 1. Respondents were informed of the voluntary nature of their participation, and anonymity was maintained to ensure data confidentiality.

Variable measurement relied on multiple scales depending on construct characteristics. Several constructs, including propensity to indebtedness (FinTech-based loan), financial behavior bias, culture, emotions, materialism, job security, and most items of religiosity, were measured using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree/very rare) to 5 (strongly agree/very frequent).

For financial literacy, the measurement employed a set of scenario-based and knowledge-based multiple-choice questions (FL1–FL6). The answer options varied across items, such as frequency comparison, portfolio diversification, and bond pricing, following established financial literacy instruments.

For religiosity, most indicators (R1, R2, R4, R5) were assessed using the five-point Likert scale, while one indicator (R3) applied a ratio-based categorical scale (e.g., 90:10, 70:30, 60:40, 50:50, 30:70) to capture the balance between daily routine and spiritual activities. This differentiation ensured content validity and accurate reflection of religious commitment.

Table 1.

Measurement of Variables.

Table 1.

Measurement of Variables.

| Variable |

Item |

Measurement |

References |

Financial

behavior bias |

FBB1 |

I often make financial decisions without careful consideration. |

Hamid [89]; Ritika and Kishor [90]; Zainol et al. [80] |

| FBB2 |

I frequently purchase goods due to the influence of others or advertisements. |

| FBB3 |

I often regret after making impulsive (unplanned) purchases. |

| FBB4 |

I consider it important to prepare a budget before making expenditures. |

| FBB5 |

I often make purchases based on emotions rather than logic. |

| Culture |

C1 |

My family habits or traditions influence my financial decisions. |

Bahrawi and Aldossry [91]; Chetioui et al. [92]; Yates and de Oliveira [93] |

| |

C2 |

I often follow the shopping habits of my family or friends. |

| |

C3 |

Social norms influence the way I manage money. |

| |

C4 |

I feel it is important to own items similar to those around me. |

| |

C5 |

I feel social pressure to purchase certain goods. |

| Emotions |

E1 |

I feel stressed when I have debt. |

Azma et al. [13]; Rahman et al. [18]

|

| |

E2 |

I often purchase goods to improve my mood. |

| |

E3 |

I feel happy after making large purchases. |

| |

E4 |

I feel guilty after making unplanned purchases. |

| |

E5 |

My emotions frequently influence my financial decisions. |

| Materialism |

M1 |

I often feel satisfied after purchasing new items. |

Azma et al. [13];

Flores et al. [48] |

| |

M2 |

Owning luxury goods is very important to me. |

| |

M3 |

I believe that material wealth is a measure of success. |

| |

M4 |

I frequently buy items that I do not really need. |

| |

M5 |

I am willing to go into debt to purchase luxury goods. |

Financial

literacy |

FL1 |

Imagine that the interest rate on your savings account is 1% per year and inflation is 2% per year. After one year, will you be able to buy more than today, the same as today, or less than today with the money in the account? |

Lusardi and Tufano [94,95] |

| |

FL2 |

If the inflation rate is 3% per year and your savings earn an interest of 2% per year, after one year will your money buy more, the same, or less than today? |

| |

FL3 |

Suppose you want to invest your money. Which of the following is the best way to reduce investment risk? |

| |

FL4 |

If market interest rates rise, what will happen to the price of existing bonds in the market? |

| |

FL5 |

You have a balance of IDR 1,000,000 on your credit card with an annual interest rate of 18%, and you make no payments at all. How much debt will you owe after one year? |

| |

FL6 |

Suppose in 2024, your income doubles and the prices of all goods also double. In 2024, how much can you buy with your income compared to today? |

| Job security |

JS1 |

I feel that my current job provides me with stability. |

Blotenberg and Richter [96];

Probst [97] |

| |

JS2 |

I can remain in my current job for as long as I wish. |

| |

JS3 |

I feel secure in my job stability as long as my performance meets expectations. |

| |

JS4 |

I am not worried about my future career in this company/organization. |

| |

JS5 |

I feel that there is no threat of losing my job in this company/organization. |

| Religiosity |

R1 |

If I had to choose between attending a religious event or a free concert of my favorite musician, I would choose to attend the concert. |

Mahdzan [63]; Zainol [80] |

| |

R2 |

I always pray before starting any activity. |

| |

R3 |

The distribution of my time between routine activities and religious activities in a 24-hour period is… |

| |

R4 |

Before making any decision, I pray and seek guidance from my spiritual leader. |

| |

R5 |

I believe in the individual right to change one’s religion. |

| Propensity to indebtedness |

PTI1 |

I am likely to use a fintech loan app even if I am unsure how I will repay the loan. |

Azma et al. [13]; Vieira et al. [98]; Barros and

Botelho [99] |

| |

PT12 |

I often use fintech lending platforms for small purchases that I cannot afford in cash. |

| |

PTI3 |

Even when I do not urgently need money, I consider borrowing through digital loans. |

| |

PTI4 |

I believe I will be able to repay fintech loans, even when I am uncertain about my income next month. |

| |

PTI5 |

I have used or considered using multiple fintech loan applications simultaneously. |

3.2. Methods

This study applied Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) using SmartPLS version 3.2.9 as the primary data analysis technique. PLS-SEM was chosen due to its suitability for exploratory models with multiple constructs, ability to handle both reflective and formative indicators, robustness with complex moderating relationships, and minimal distributional assumptions compared to covariance-based SEM [

100].

The analysis followed the standard PLS-SEM procedure, which comprised three main stages. First, the measurement model evaluation assessed reliability (indicator and construct reliability), convergent validity, and discriminant validity to ensure construct soundness. Second, the structural model evaluation examined the hypothesized relationships through path coefficients, t-statistics, and p-values obtained via bootstrapping. Third, an Importance–Performance Map Analysis (IPMA) was conducted to complement path analysis by identifying constructs that not only influence outcomes but also present opportunities for improvement.

4. Results

4.1. Respondent Profile

Table 2 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the 400 respondents. The sample was relatively balanced in terms of gender, with 52.5% male and 47.5% female. The majority of respondents were in the mid-career age range, particularly 36–40 years (23.0%), 46–50 years (21.3%), and 41–45 years (19.3%), while younger (<25 years) and older (>55 years) groups were less represented. This distribution suggests that digital loan adoption is most prevalent among individuals in their economically active years, when financial commitments are typically higher.

In terms of occupation, civil servants dominated the sample (68.3%), followed by private employees and entrepreneurs (31.8%). Regarding income, more than half of respondents (58.5%) reported monthly earnings between IDR 5,000,001 and IDR 10,000,000, while 25.8% earned less than IDR 5,000,000 and only 15.8% exceeded IDR 10,000,000. These figures indicate that fintech-based loans are particularly attractive to middle-income groups, who may seek credit to support consumption or manage liquidity, rather than for large-scale investment. Overall, the respondent profile reflects that fintech loan users are predominantly middle-income, mid-career individuals with relatively stable occupations.

4.2. Measurement Model Evaluation

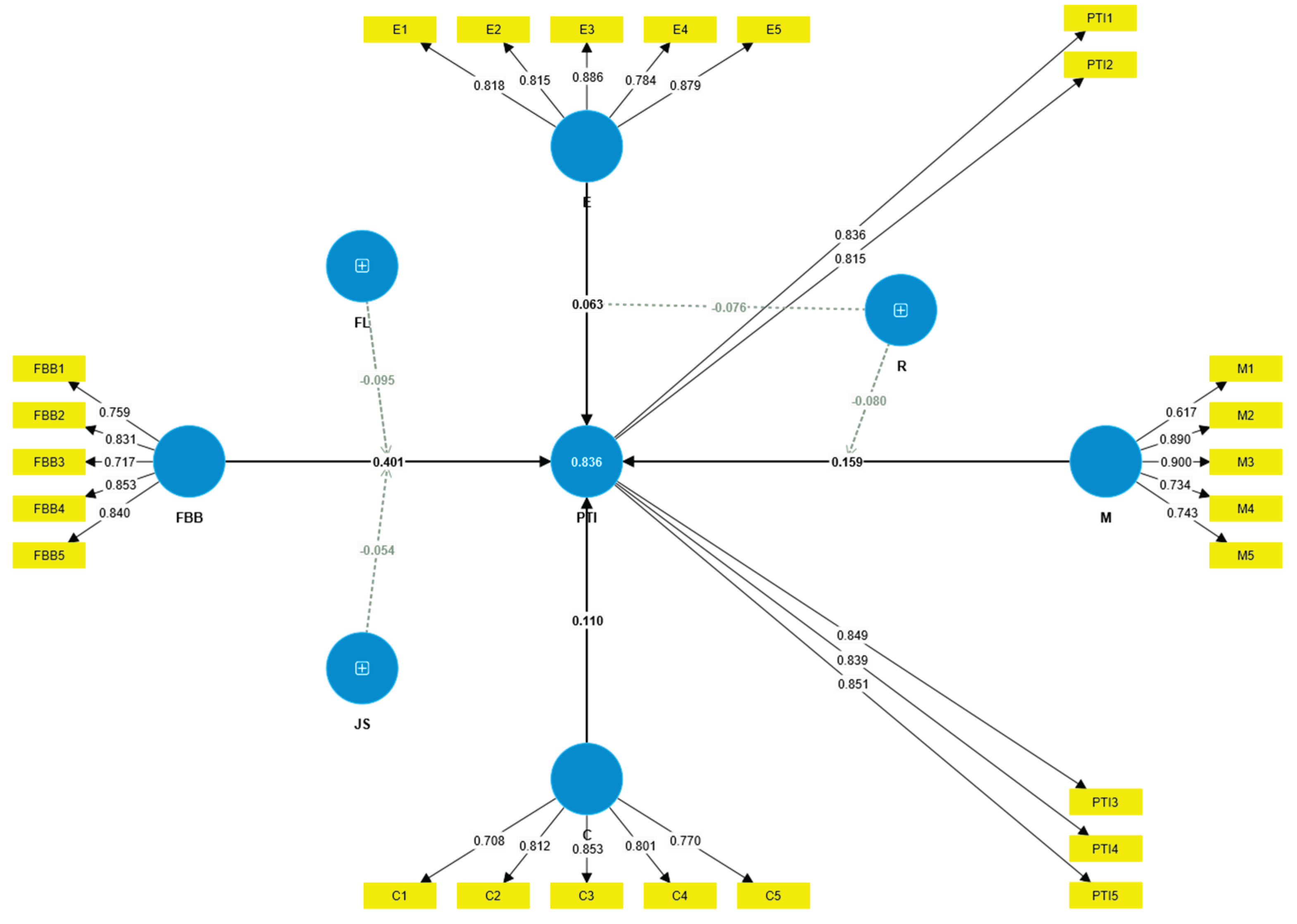

The measurement model was first assessed through indicator reliability, internal consistency, and convergent validity. As presented in

Table 3, all outer loadings exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70, except for a few items (e.g., M1 = 0.617), which were still acceptable given that the construct reliability values remained adequate [

100]. Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) values ranged from 0.831 to 0.920, while Composite Reliability (CR) values ranged from 0.880 to 0.940, all above the minimum criterion of 0.70, indicating satisfactory internal consistency. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values also exceeded the recommended 0.50 threshold, confirming convergent validity for all constructs.

Discriminant validity was examined using the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT). As shown in

Table 4, all HTMT values were below the conservative threshold of 0.90 [

101], supporting discriminant validity across constructs. Furthermore, the structural assessment confirmed that multicollinearity was not an issue, as all variance inflation factor (VIF) values were within the acceptable range.

Figure 2 illustrates the validated measurement model derived from the SEM-PLS analysis, confirming that the specified constructs and their indicators demonstrated adequate reliability and validity. Collectively, these results provide a strong foundation for further testing of the structural relationships among the constructs.

4.3. Structural Model Results

The structural model assessment shows that the proposed framework demonstrates substantial explanatory power. The coefficient of determination indicates that R² = 0.831 for propensity to indebtedness, suggesting that the exogenous constructs collectively explain 83.1% of the variance in the dependent variable, which is considered substantial according to Hair et al. [

100]. Furthermore, the Stone–Geisser predictive relevance test reveals a value of Q² = 0.568, confirming that the model has strong predictive capability.

Table 5.

Structural Model Fit and Predictive Metrics.

Table 5.

Structural Model Fit and Predictive Metrics.

| Metric |

Construct |

Value |

Description |

Coefficient of

Determination |

Propensity to indebtedness |

R2 = 0.831 |

Substantial explanatory power |

| Effect Size |

Financial behavior biases |

f2 = 0.421 |

Large effect |

| |

Culture |

f2 = 0.020 |

Small effect |

| |

Emotions |

f2 = 0.016 |

Small effect (below threshold) |

| |

Materialism |

f2 = 0.057 |

Small-to-medium effect |

| |

Financial literacy |

f2 = 0.324 |

Medium-to-large effect |

| |

Job security |

f2 = 0.005 |

Negligible effect |

| |

Religiosity |

f2 = 0.310 |

Medium-to-large effect |

| |

Financial behavior biases*financial literacy |

f2 = 0.046 |

Small effect |

| |

Financial behavior biases*job security |

f2 = 0.017 |

Small effect (below threshold) |

| |

Emotions*religiosity |

f2 = 0.028 |

Small effect |

| |

Materialism*religiosity |

f2 = 0.036 |

Small effect |

Predictive

Relevance |

Propensity to indebtedness |

Q2 = 0.568 |

Strong predictive relevance |

Regarding effect sizes, financial behavior biases (f² = 0.421), financial literacy (f² = 0.324), and religiosity (f² = 0.310) demonstrate large effects on propensity to indebtedness, indicating their central roles in shaping debt tendencies. Materialism shows a small-to-medium effect (f² = 0.057), while culture (f² = 0.020) and emotions (f² = 0.016) exert small effects. The moderating variables present relatively weaker contributions, with financial literacy moderating financial behavior biases (f² = 0.046), job security moderating financial behavior biases (f² = 0.017), religiosity moderating emotions (f² = 0.028), and religiosity moderating materialism (f² = 0.036). Most of these interaction effects fall within the small range, but remain statistically meaningful for understanding the nuanced pathways in the model.

The path coefficient results provide empirical support for all proposed hypotheses (

Table 6). Financial behavior biases exert the strongest direct influence on propensity to indebtedness (

β = 0.401,

p < 0.001), confirming their critical role in shaping borrowing tendencies. Culture (

β = 0.110,

p < 0.01), emotions (

β = 0.063,

p < 0.05), and materialism (

β = 0.159,

p < 0.001) also positively affect indebtedness, though with relatively smaller magnitudes compared to behavioral biases.

The moderating effects provide further insight into boundary conditions of indebtedness behavior. Financial literacy strengthens the impact of financial behavior biases (β = 0.095, p < 0.001), highlighting its paradoxical role where higher literacy may not reduce but instead enhance the expression of existing biases. Similarly, job security amplifies the influence of behavioral biases (β = 0.054, p < 0.05), suggesting that individuals with stable employment may feel more confident to take on debt despite bias-driven decisions.

Religiosity shows a contrasting effect: it weakens the impact of emotions (β = −0.076, p < 0.05) and materialism (β = −0.080, p < 0.05) on indebtedness. This indicates that religious values act as a protective factor, mitigating the debt-inducing influence of affective impulses and material desires.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that both cognitive biases and socio-cultural-emotional drivers significantly shape indebtedness, while moderating conditions such as literacy, security, and religiosity further refine these relationships. Hence, all eight proposed hypotheses (H1–H8) are empirically supported.

4.4. Importance–Performance Mapping Analysis (IPMA)

The IPMA results combine descriptive analysis (mean performance) with inferential analysis (total effects). As suggested by Ringle and Sarstedt [

102], the procedure involves constructing importance values from the total effects and combining them with performance values. By calculating the averages of both importance and performance, vertical and horizontal lines are drawn to divide the map into four quadrants. Importance is represented on the X-axis, and performance is represented on the Y-axis. This mapping provides a strategic visualization of which constructs demonstrate satisfactory performance and should be maintained, and which require further improvement.

Table 7.

Importance–Performance Mapping of Constructs.

Table 7.

Importance–Performance Mapping of Constructs.

| Variable |

Construct Importance |

Construct Performances |

| Financial behavior biases |

0.389 |

33.947 |

| Culture |

0.116 |

73.037 |

| Emotions |

0.065 |

76.129 |

| Materialism |

0.155 |

20.179 |

| Financial literacy |

0.360 |

33.420 |

| Job security |

0.050 |

48.064 |

| Religiosity |

0.278 |

81.915 |

| Average |

0.202 |

52.384 |

Based on

Figure 3, the target construct (propensity to indebtedness) distributes the variables into four quadrants according to their relative importance and performance. Religiosity is located in the upper-right quadrant, characterized by high importance (0.278) and strong performance (81.915). This suggests that religiosity not only plays a central role in shaping borrowing behavior but also demonstrates strong application in practice, making it a core element to maintain in both educational and policy interventions. Culture and emotions are situated in the upper-left quadrant, indicating that while respondents perceive them as less important (0.116 and 0.065, respectively), their performance is above average (73.037 and 76.129). These constructs, though not central, still contribute positively and should be reinforced to sustain their effects.

In contrast, financial behavior biases and financial literacy are mapped into the lower-right quadrant, reflecting high importance (0.389 and 0.360) but weak performance (33.947 and 33.420). This indicates a substantial gap between the constructs’ significance and their effectiveness, highlighting the urgency of intervention. Improving literacy programs and addressing behavioral distortions should therefore be prioritized to mitigate over-indebtedness risks. Finally, job security and materialism fall into the lower-left quadrant with both low importance (0.050 and 0.155) and low performance (48.064 and 20.179). Although not primary concerns for respondents, these constructs may warrant attention if external conditions increase their salience in the future.

Taken together, the IPMA provides a comprehensive mapping that identifies religiosity as a high-performing safeguard against indebtedness, while financial literacy and behavioral biases emerge as critical areas for improvement. This analysis offers a practical guide for prioritizing interventions by policymakers, educators, and fintech providers.

5. Discussion

The results of this study provide strong empirical support for the central role of psychological, cultural, and contextual factors in shaping individuals’ propensity to incur debt through FinTech-based loans. The strongest effect was observed for financial behavior biases (H1 supported), confirming that cognitive distortions remain pivotal in explaining debt-related decisions. Consistent with behavioral finance literature, overconfidence and herding behaviors can lead individuals to underestimate repayment risks or to emulate peers without adequate reflection [

33,

35]. In FinTech environments, these biases are magnified by the immediacy and accessibility of digital platforms, which encourage impulsive borrowing and reduce time for deliberation [

11,

27]. This finding corroborates prior evidence that the speed and personalization of digital lending can encourage risk-taking behaviors, particularly among individuals with limited self-regulation [

10,

89].

Culture also exhibited a significant relationship with indebtedness (H2 supported). The cultural measurement in this study, which included family traditions, shopping habits, social norms, and perceived peer pressure, offers a more relational perspective than traditional Hofstede-type frameworks. The results suggest that individuals who are strongly influenced by family shopping practices, societal expectations, or peer consumption patterns are more likely to take on debt, even in digital lending contexts. This aligns with earlier findings that collectivist orientations and social conformity pressures can increase financial vulnerability [

39,

41].

The emphasis on items such as “I feel pressure from society to buy certain goods” resonates with research demonstrating that debt often serves not only as a financial tool but also as a means of maintaining social belonging and status [

40,

43]. In FinTech contexts, where consumerism is reinforced by targeted digital advertising and peer sharing, the cultural drive to conform may be even stronger, reflecting how economic behavior is deeply embedded in relational and normative frameworks [

11,

37].

Emotions also played a role in increasing borrowing tendencies (H3 supported), though their effect was smaller compared to biases and culture. This result is consistent with studies showing that emotional states, including excitement, anxiety, or embarrassment, can influence credit uptake and repayment outcomes [

13,

46]. Particularly in FinTech-based loans, where decisions are often made rapidly and in private, emotions may bypass rational evaluation, leading individuals to borrow either as a coping mechanism or as a response to social comparison [

9,

47].

Materialism (H4 supported) also demonstrated a positive and significant relationship with indebtedness, reaffirming prior evidence that individuals who place high value on possessions and social status are more inclined toward excessive consumption and higher debt levels [

18,

55]. These findings align with the Behavioral Life-Cycle Hypothesis [

88], in which the “doer” driven by short-term gratification often overrides the “planner” that seeks long-term stability.

The moderating variables provided further nuance to these relationships. Contrary to the conventional view that financial literacy reduces risky borrowing, this study found that it strengthened the effect of financial behavior biases on indebtedness (H5 supported). This paradox may reflect the phenomenon where individuals with higher literacy develop confidence in their ability to manage debt, but instead use their knowledge to rationalize biased or impulsive borrowing choices. Such a finding is consistent with recent evidence that literacy does not always serve as a protective factor and may interact with overconfidence in unexpected ways [

60,

61].

Job security similarly amplified the effect of behavioral biases on borrowing (H6 supported). This suggests that individuals with stable employment may perceive debt as more manageable and thus feel emboldened to take on credit, even when influenced by biases. This finding extends earlier work linking job security to increased borrowing confidence and reduced precautionary saving [

3,

77].

In contrast, religiosity demonstrated a mitigating effect, weakening the influence of both emotions and materialism on indebtedness (H7 and H8 supported). This result reinforces evidence that religious values often serve as a protective mechanism, discouraging impulsive consumption and framing debt as a moral burden [

80,

81]. By weakening emotional and materialistic drivers of debt, religiosity provides individuals with a value-based framework for resisting consumerist pressures and impulsive borrowing. This supports prior findings that religiosity can buffer the effect of materialism on debt propensity [

64] and influence emotion regulation strategies in ways that promote greater financial restraint [

82,

83]. However, this effect is not always uniform, as some studies highlight contexts where religiosity may indirectly reinforce consumption through status signaling [

84], pointing to the need for further investigation of contextual differences.

These findings also carry particular significance in the context of Indonesia as an emerging economy. Indonesian borrowers, especially civil servants and private employees/self-employed workers targeted in this study, often have fixed or predictable incomes. This makes them attractive clients for FinTech lenders but simultaneously exposes them to higher risks of debt accumulation if borrowing is influenced by biases, emotions, or cultural pressures. Previous studies indicate that digital credit in emerging markets often serves as a tool for short-term consumption smoothing rather than productive investment, increasing the risk of over-indebtedness [

27,

29].

In Indonesia, where digital financial literacy and consumer protection frameworks are still developing, these dynamics are particularly relevant. The combination of cultural conformity, strong materialistic aspirations, and widespread FinTech adoption among the middle-income population underscores the need for contextualized policies. At the same time, the moderating role of religiosity highlights the importance of integrating cultural and spiritual values into financial education and consumer awareness strategies.

Overall, the study demonstrates that indebtedness in FinTech contexts cannot be explained solely by access to digital credit but results from a complex interplay of psychological, cultural, and contextual factors. The full support for all hypotheses illustrates the robustness of the proposed framework, showing that theories such as TAM, TPB, and BLCH collectively explain how individuals navigate digital borrowing decisions [

86,

87,

88]. Importantly, while FinTech adoption expands financial inclusion in Indonesia and other emerging economies, without careful attention to behavioral and cultural determinants it risks deepening consumer vulnerability and unsustainable debt accumulation.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the propensity to indebtedness in FinTech-based loans among Indonesian borrowers is shaped not only by technological access but also by psychological, cultural, and spiritual factors. Financial behavior biases exert the strongest influence, followed by materialism, culture, and emotions, while moderating variables such as financial literacy and job security can paradoxically amplify bias-driven borrowing. Religiosity, on the other hand, plays a protective role by dampening the effects of materialism and emotions, confirming its function as a moral and behavioral regulator. These findings highlight that indebtedness in emerging economies such as Indonesia is best understood through a multidimensional lens that integrates behavioral finance with socio-cultural and contextual factors, thereby extending the explanatory power of TAM, TPB, and BLCH in digital lending settings.

Theoretically, this study enriches the behavioral finance literature by demonstrating that indebtedness in FinTech environments cannot be understood solely through access and technology adoption, but requires accounting for the interplay of biases, cultural norms, and emotional drivers. By testing moderating variables, it extends prior research showing that financial literacy and job security may paradoxically amplify bias-driven borrowing, while religiosity serves as a buffer. These findings strengthen behavioral theories of debt and provide a culturally contextualized extension of the BLCH framework in emerging economies.

Practically, the findings carry significant implications for regulators, FinTech firms, and consumers in Indonesia and similar emerging markets. Strengthening financial literacy programs is essential, but such initiatives must go beyond technical knowledge by incorporating emotional regulation, cultural awareness, and critical thinking skills to reduce impulsive borrowing. Policies that enhance employment stability can indirectly reduce over-indebtedness by mitigating the perceived security that drives risk-taking under behavioral biases. The integration of religiosity into financial management programs, particularly in predominantly religious societies such as Indonesia, can further serve as a safeguard against excessive borrowing. Finally, the development of more responsible credit policies, such as adaptive credit scoring, transparent loan terms, and behavioral nudges, can promote healthier borrowing practices and protect vulnerable borrowers.

This study is not without limitations. The cross-sectional design restricts causal inference, and the sample, limited to civil servants and private/self-employed workers, may not fully capture the dynamics of informal workers or rural borrowers. Self-reported measures also pose risks of social desirability bias, particularly for sensitive items such as religiosity and debt behavior. Future research should adopt longitudinal or experimental approaches, extend the sample to include more diverse populations, and explore additional determinants such as digital trust, social media influence, and institutional regulations. Comparative studies across different emerging economies would also enrich the understanding of cultural and institutional differences in FinTech indebtedness, while qualitative approaches could provide deeper insights into borrowers’ lived experiences.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, A.W., D.S., and A.Z.A.; methodology, A.W., D.S., and A.Z.A.; software, A.Z.A.; validation, D.S., and A.Z.A.; formal analysis, A.W., and A.Z.A.; investigation, A.W., D.S., and A.Z.A.; resources, A.W.; data curation, A.W., and A.Z.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.W., and A.Z.A.; writing—review and editing, A.W., D.S., and A.Z.A.; visualization, A.Z.A.; supervision, D.S., and A.Z.A.; project administration, A.W.; funding acquisition, A.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Universitas Bina Darma (No. 0501/Univ-BD/IX/2025, 25 August 2025) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participation was voluntary, and respondents were assured of anonymity and confidentiality before completing the online questionnaire.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, as they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants. No publicly archived datasets were generated during this study. In compliance with MDPI Research Data Policies, anonymized survey instruments can be made available to qualified researchers upon request.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cumming, D. J.; Sewaid, A. FinTech Loans, Self-Employment, and Financial Performance; 2021. [CrossRef]

- Danisewicz, P.; Elard, I. The Real Effects of Financial Technology: Marketplace Lending and Personal Bankruptcy. J. Bank. Financ., 2023, 155, 106986. [CrossRef]

- Croux, C.; Jagtiani, J.; Korivi, T.; Vulanovic, M. Important Factors Determining Fintech Loan Default: Evidence from a Lendingclub Consumer Platform. J. Econ. Behav. Organ., 2020, 173, 270–296. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J. P.; Jagtiani, J.; Moon, C.-G. Consumer Lending Efficiency: Commercial Banks versus a Fintech Lender. Financ. Innov., 2022, 8 (1), 1–39. [CrossRef]

- IRU-OJK. Financing Institutions, Venture Capital, Fintech P2P Lending and Micro Finance Industry Update December 2024 https://iru.ojk.go.id/iru/dataandstatistics/detaildataandstatistics/13379/financing-institutions-venture-capital-fintech-p2p-lending-and-micro-finance-industry-update-december-2024 (accessed Mar 10, 2025).

- IRU-OJK. Indonesia Financial Sector Development Q4 2023; Jakarta, 2024.

- Jakpat. Indonesia Fintech Trends – 1st Semester of 2024; Yogyakarta, 2024.

- Thomas, N. M.; Mendiratta, P.; Kashiramka, S. FinTech Credit: Uncovering Knowledge Base, Intellectual Structure and Research Front. Int. J. Bank Mark., 2023, 41 (7), 1769–1802. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, T.; Lu, X. Social Media Meets FinTech Platforms: How Do Online Emotions Support Credit Risk Decision-Making? Decis. Support Syst., 2025, 195, 114471. [CrossRef]

- Bu, D.; Hanspal, T.; Liao, Y.; Liu, Y. Cultivating Self-Control in FinTech: Evidence from a Field Experiment on Online Consumer Borrowing. J. Financ. Quant. Anal., 2022, 57 (6), 2208–2250. [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, M.; Maçada, A. C. G.; de Oliveira Santini, F.; Rasul, T. Continuance Intention in Financial Technology: A Framework and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Bank Mark., 2023, 41 (4), 749–786. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, D. Unraveling Youth Indebtedness in China: A Case Study Based on the “Debtors Avengers” Community on Douban. Int. J. Financ. Stud., 2024, 12 (4), 113. [CrossRef]

- Azma, N.; Rahman, M.; Adeyemi, A. A.; Rahman, M. K. Propensity toward Indebtedness: Evidence from Malaysia. Rev. Behav. Financ., 2019, 11 (2), 188–200. [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J. S.; Li, Y.; Valdesolo, P.; Kassam, K. S. Emotion and Decision Making. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 2015, 66 (Volume 66, 2015), 799–823. [CrossRef]

- Richins, M. L. Materialism, Transformation Expectations, and Spending: Implications for Credit Use. J. Public Policy Mark., 2011, 30 (2), 141–156. [CrossRef]

- Iliyas, M. A.; Kumar, P. K. Personalization in the FinTech Age. In Financial Innovation for Global Sustainability; Afjal, M., Birau, R., Eds.; Scrivener Publishing, 2025; pp 249–279. [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Yang, Q.; Yu, P. S. Data Science and AI in FinTech: An Overview. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal., 2021, 12 (2), 81–99. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Azma, N.; Masud, M. A.; Ismail, Y. Determinants of Indebtedness: Influence of Behavioral and Demographic Factors. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2020, p 8. [CrossRef]

- Solarz, M.; Adamek, J. Trust and Personal Innovativeness as the Prerequisites for Using Digital Lending Services Offered by FinTech Lenders. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Skłodowska, Sect. H–Oeconomia, 2023, 57 (1), 197–218. [CrossRef]

- Zubair, D.; Tiwary, D. Early Warning System Model for Non-Performing Loans of Emerging Market Fintech Firms BT. In Financial Markets, Climate Risk and Renewables; Mohapatra, S., Padhi, P., Singh, V., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2024; pp 221–240.

- Roh, T.; Yang, Y. S.; Xiao, S.; Park, B. Il. What Makes Consumers Trust and Adopt Fintech? An Empirical Investigation in China. Electron. Commer. Res., 2024, 24 (1), 3–35. [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rahim, R.; Bohari, S. A.; Aman, A.; Awang, Z. Benefit–Risk Perceptions of FinTech Adoption for Sustainability from Bank Consumers’ Perspective: The Moderating Role of Fear of COVID-19. Sustainability. 2022, p 8357. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guan, Z. (Gordon); Hou, F.; Li, B.; Zhou, W. What Determines Customers’ Continuance Intention of FinTech? Evidence from YuEbao. Ind. Manag. Data Syst., 2019, 119 (8), 1625–1637. [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Ji, J.; Sun, H.; Xu, H. Legal Enforcement and Fintech Credit: International Evidence. J. Empir. Financ., 2023, 72, 214–231. [CrossRef]

- Banasaz, M.; Bose, N.; Sedaghatkish, N. Identification of Loan Effects on Personal Finance: A Case for Small U.S. Entrepreneurs. J. Econ. Behav. Organ., 2025, 234, 106982. [CrossRef]

- Cornelli, G.; Frost, J.; Gambacorta, L.; Jagtiani, J. The Impact of Fintech Lending on Credit Access for U.S. Small Businesses. J. Financ. Stab., 2024, 73, 101290. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Marisetty, V. B. Are FinTech Lending Apps Harmful? Evidence from User Experience in the Indian Market. Br. Account. Rev., 2023, 101269. [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Leung, H.; Liu, L.; Qiu, B. Consumer Behaviour and Credit Supply: Evidence from an Australian FinTech Lender. Financ. Res. Lett., 2023, 57, 104205. [CrossRef]

- Burlando, A.; Kuhn, M. A.; Prina, S. Too Fast, Too Furious? Digital Credit Delivery Speed and Repayment Rates. J. Dev. Econ., 2025, 174, 103427. [CrossRef]

- Hodula, M. Does Fintech Credit Substitute for Traditional Credit? Evidence from 78 Countries. Financ. Res. Lett., 2022, 46, 102469. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hou, S.; Kyaw, K.; Xue, X.; Liu, X. Exploring the Determinants of Fintech Credit: A Comprehensive Analysis. Econ. Model., 2023, 126, 106422. [CrossRef]

- Maji, S. K.; Prasad, S. Present Bias and Its Influence on Financial Behaviours amongst Indians. IIM Ranchi J. Manag. Stud., 2025, 4 (1), 17–30. [CrossRef]

- Ayad, K.; Touil, A.; El Hamidi, N.; Bennani, K. D. Does Behavioral Biases Matter in SMEs’ Borrowing Decisions? Insights from Morocco. Banks Bank Syst., 2024, 19 (1), 170–182. [CrossRef]

- Hamid, F. S.; Harizan, S. H. M. Behavioral Biases and Credit Card Repayments among Malaysians. Int. J. Bank. Financ., 2023, 18 (2), 53–78. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Hewege, C.; Perera, C. Exploring the Relationships Between Behavioural Biases and the Rational Behaviour of Australian Female Consumers. Behavioral Sciences. 2025, p 58. [CrossRef]

- Mutsonziwa, K.; Fanta, A. Over-Indebtedness and Its Welfare Effect on Households. African J. Econ. Manag. Stud., 2019, 10 (2), 185–197. [CrossRef]

- Goodell, J. W.; Kumar, S.; Lahmar, O.; Pandey, N. A Bibliometric Analysis of Cultural Finance. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal., 2023, 85. [CrossRef]

- Gogolin, F.; Dowling, M.; Cummins, M. Individual Values and Household Finances. Appl. Econ., 2017, 49 (35), 3560–3578. [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Tanner, E. C.; Marquart, N. A.; Zhao, D. We Are Not All the Same: The Influence of Personal Cultural Orientations on Vulnerable Consumers’ Financial Well-Being. J. Int. Mark., 2022, 30 (3), 57–71. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.; Shin, F.; Lawless, R. M. Attitudes, Behavior, and Institutional Inversion: The Case of Debt. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol., 2021, 120 (5), 1117–1145. [CrossRef]

- Villarreal, R.; Peterson, R. A. The Concept and Marketing Implications of Hispanicness. J. Mark. Theory Pract., 2009, 17 (4), 303–316. [CrossRef]

- Hitokoto, H. Indebtedness in Cultural Context: The Role of Culture in the Felt Obligation to Reciprocate. Asian J. Soc. Psychol., 2016, 19 (1), 16–25. [CrossRef]

- Henchoz, C.; Coste, T.; Wernli, B. Culture, Money Attitudes and Economic Outcomes. Swiss J. Econ. Stat., 2019, 155 (1), 2. [CrossRef]

- Izard, C. E. The Many Meanings/Aspects of Emotion: Definitions, Functions, Activation, and Regulation. Emot. Rev., 2010, 2 (4), 363–370. [CrossRef]

- Koob, G. F. The Dark Side of Emotion: The Addiction Perspective. Eur. J. Pharmacol., 2015, 753, 73–87. [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani, C.; Vandone, D. Impulsivity and Household Indebtedness: Evidence from Real Life. J. Econ. Psychol., 2011, 32 (5), 754–761. [CrossRef]

- Marston, G.; Banks, M.; Zhang, J. The Role of Human Emotion in Decisions about Credit: Policy and Practice Considerations. Crit. Policy Stud., 2018, 12 (4), 428–447. [CrossRef]

- Flores, S. A. M.; Vieira, K. M. Propensity toward Indebtedness: An Analysis Using Behavioral Factors. J. Behav. Exp. Financ., 2014, 3, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Siddiqui, D. A. Does Materialism, Emotions, Risk and Financial Literacy Affects the Propensity for Indebtedness in Pakistan: The Complementary Role of Hedonism and Demographics. Emot. Risk Financ. Lit. Affect. Propensity Indebt. Pakistan Complement. Role Hedonism Demogr., 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M. B.; de Almeida, F.; Soro, J. C.; Herter, M. M.; Pinto, D. C.; Silva, C. S. On the Relation Between Over-Indebtedness and Well-Being: An Analysis of the Mechanisms Influencing Health, Sleep, Life Satisfaction, and Emotional Well-Being. Front. Psychol., 2021, 12, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Rendall, S.; Brooks, C.; Hillenbrand, C. The Impacts of Emotions and Personality on Borrowers’ Abilities to Manage Their Debts. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal., 2021, 74, 101703. [CrossRef]

- Maison, D.; Adamczyk, D. The Relations between Materialism, Consumer Decisions and Advertising Perception. Procedia Comput. Sci., 2020, 176, 2526–2535. [CrossRef]

- Watson, J. J. The Relationship of Materialism to Spending Tendencies, Saving, and Debt. J. Econ. Psychol., 2003, 24 (6), 723–739. [CrossRef]

- Garðarsdóttir, R. B.; Dittmar, H. The Relationship of Materialism to Debt and Financial Well-Being: The Case of Iceland’s Perceived Prosperity. J. Econ. Psychol., 2012, 33 (3), 471–481. [CrossRef]

- Raj, V. A.; Jasrotia, S. S.; Rai, S. S. Intensifying Materialism through Buy-Now Pay-Later (BNPL): Examining the Dark Sides. Int. J. Bank Mark., 2024, 42 (1), 94–112. [CrossRef]

- Matos, C. A. de; Vieira, V.; Bonfanti, K.; Mette, F. M. B. Antecedents of Indebtedness for Low-Income Consumers: The Mediating Role of Materialism. J. Consum. Mark., 2019, 36 (1), 92–101. [CrossRef]

- OECD-INFE. Measuring Financial Literacy: Core Questionnaire in Measuring Financial Literacy: Questionnaire and Guidance Notes for Conducting an Internationally Comparable Survey of Financial Literacy; 2011.

- Gerth, F.; Lopez, K.; Reddy, K.; Ramiah, V.; Wallace, D.; Muschert, G.; Frino, A.; Jooste, L. The Behavioural Aspects of Financial Literacy. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2021, p 395. [CrossRef]

- French, D.; McKillop, D. Financial Literacy and Over-Indebtedness in Low-Income Households. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal., 2016, 48, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Adil, M.; Singh, Y.; Ansari, M. S. How Financial Literacy Moderate the Association between Behaviour Biases and Investment Decision? Asian J. Account. Res., 2022, 7 (1), 17–30. [CrossRef]

- Potrich, A. C. G.; Vieira, K. M. Demystifying Financial Literacy: A Behavioral Perspective Analysis. Manag. Res. Rev., 2018, 41 (9), 1047–1068. [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M. S.; Ahmed, A. D.; Richards, D. W. Financial Literacy and Financial Well-Being of Australian Consumers: A Moderated Mediation Model of Impulsivity and Financial Capability. Int. J. Bank Mark., 2021, 39 (7), 1377–1394. [CrossRef]

- Mahdzan, N. S.; Zainudin, R.; Shaari, M. S. The Influence of Religious Belief and Psychological Factors on Borrowing Behaviour among Malaysian Public Sector Employees. Asia-Pacific J. Bus. Adm., 2022, 15 (3), 361–385. [CrossRef]

- Lebdaoui, H.; Chetioui, Y. Antecedents of Consumer Indebtedness in a Majority-Muslim Country: Assessing the Moderating Effects of Gender and Religiosity Using PLS-MGA. J. Behav. Exp. Financ., 2021, 29, 100443. [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, T.; Suresha, B.; Prakash, N.; Vazirani, K.; Krishna, T. A. Digital Financial Literacy among Adults in India: Measurement and Validation. Cogent Econ. Financ., 2022, 10 (1), 2132631. [CrossRef]

- Zaimovic, A.; Torlakovic, A.; Arnaut-Berilo, A.; Zaimovic, T.; Dedovic, L.; Nuhic Meskovic, M. Mapping Financial Literacy: A Systematic Literature Review of Determinants and Recent Trends. Sustainability. 2023, p 9358. [CrossRef]

- Aftab, R.; Fazal, A.; Andleeb, R. Behavioral Biases and Fintech Adoption: Investigating the Role of Financial Literacy. Acta Psychol. (Amst)., 2025, 257, 105065. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Nieto, B.; Serrano-Cinca, C.; de la CuestaߚGonzález, M. A Multivariate Study of Over-Indebtedness’ Causes and Consequences. Int. J. Consum. Stud., 2017, 41 (2), 188–198. [CrossRef]

- Owusu, G. M. Y.; Ossei Kwakye, T.; Duah, H. The Propensity towards Indebtedness and Savings Behaviour of Undergraduate Students: The Moderating Role of Financial Literacy. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ., 2024, 16 (2), 583–596. [CrossRef]

- Ngo, H. T.; Nguyen, L. T. H. Consumer Adoption Intention toward FinTech Services in a Bank-Based Financial System in Vietnam. J. Financ. Regul. Compliance, 2022, 32 (2), 153–167. [CrossRef]

- Galariotis, E.; Monne, J. Basic Debt Literacy and Debt Behavior. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal., 2023, 88. [CrossRef]

- Giannetti, C.; Madia, M.; Moretti, L. Job Insecurity and Financial Distress; Quaderni - Working Paper DSE; 887; Bologna, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Cuesta, M. B.; Budría, S.; Moro-Egido, A. I. Job Insecurity, Debt Burdens and Individual Health; IZA Discussion Papers; 12663; Bonn, 2019.

- Lim, V. K. G.; Sng, Q. S. Does Parental Job Insecurity Matter? Money Anxiety, Money Motives, and Work Motivation. J. Appl. Psychol., 2006, 91 (5), 1078–1087. [CrossRef]

- To, W. M.; Gao, J. H.; Leung, E. Y. W. The Effects of Job Insecurity on Employees’ Financial Well-Being and Work Satisfaction Among Chinese Pink-Collar Workers. SAGE Open, 2020, 10 (4), 2158244020982993. [CrossRef]

- Klemm, M. Job Security Perceptions and the Saving Behavior of German Households; Ruhr Economic Paper; 380; 2013.

- Basyouni, S. S.; El Keshky, M. E. S. Job Insecurity, Work-Related Flow, and Financial Anxiety in the Midst of COVID-19 Pandemic and Economic Downturn. Front. Psychol., 2021, 12, 632265. [CrossRef]

- Hirshman, S. D.; Sussman, A. B.; Vazquez-Hernandez, C.; O’Leary, D.; Trueblood, J. S. The Effect of Job Loss on Risky Financial Decision-Making. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 2025, 122 (1), e2412760121. [CrossRef]

- Adamek, J.; Solarz, M. Adoption Factors in Digital Lending Services Offered by FinTech Lenders. Oeconomia Copernicana, 2023, 14 (1), 169–212. [CrossRef]