Submitted:

11 September 2024

Posted:

11 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. Novelty and Contribution of the Research

2. Materials and Methods

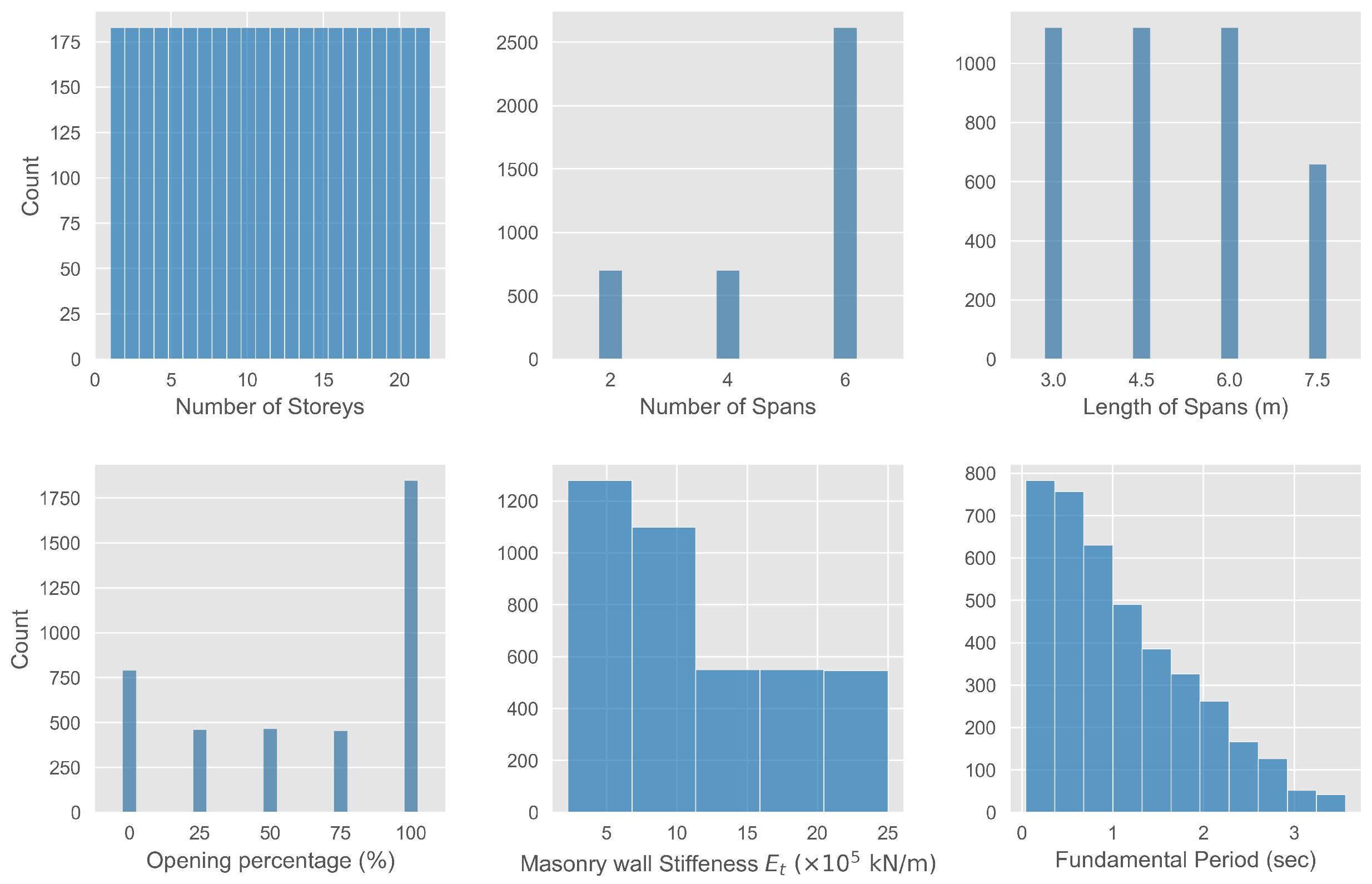

2.1. Dataset Description

2.2. Data Preprocessing

2.3. Machine Learning Modeling

2.4. Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP)

3. Results

3.1. Machine Learning Regression

| Metric | Formula |

|---|---|

| MAE | |

| RMSE | |

| Log-transformed | Original space | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | Test | Training | Test | |

| MAE | 0.0487 | 0.0517 | 0.0524 | 0.0545 |

| RMSE | 0.0645 | 0.0723 | 0.0856 | 0.0870 |

| 0.9943 | 0.9932 | 0.9879 | 0.9879 | |

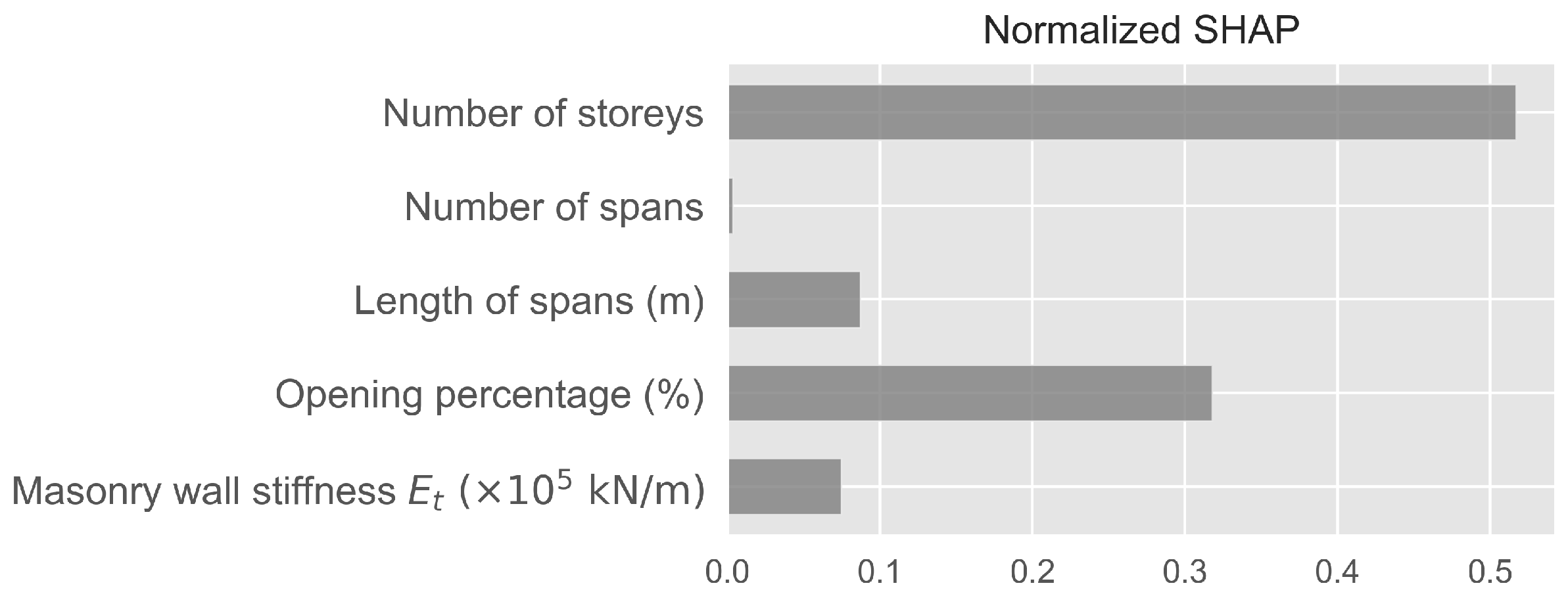

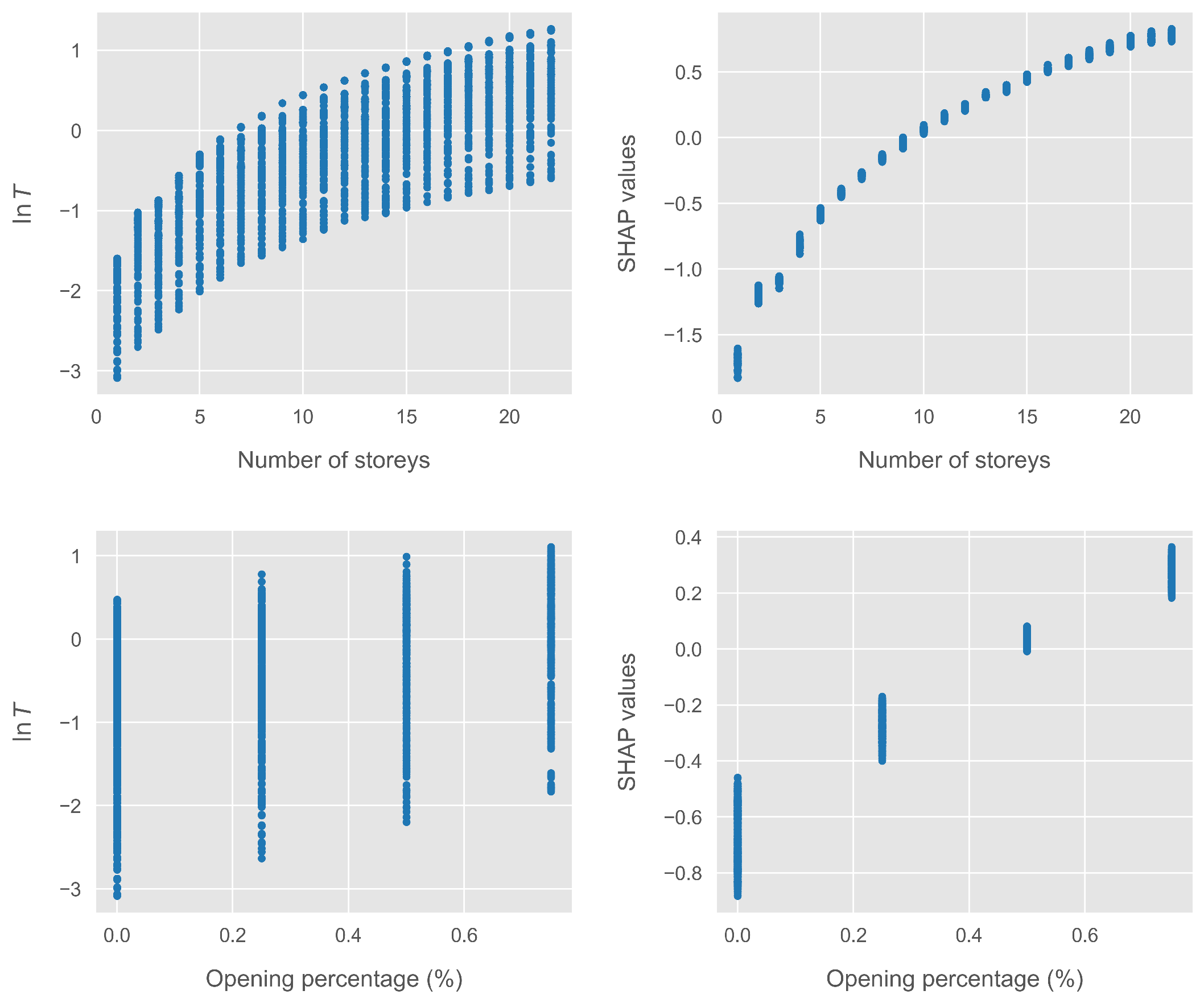

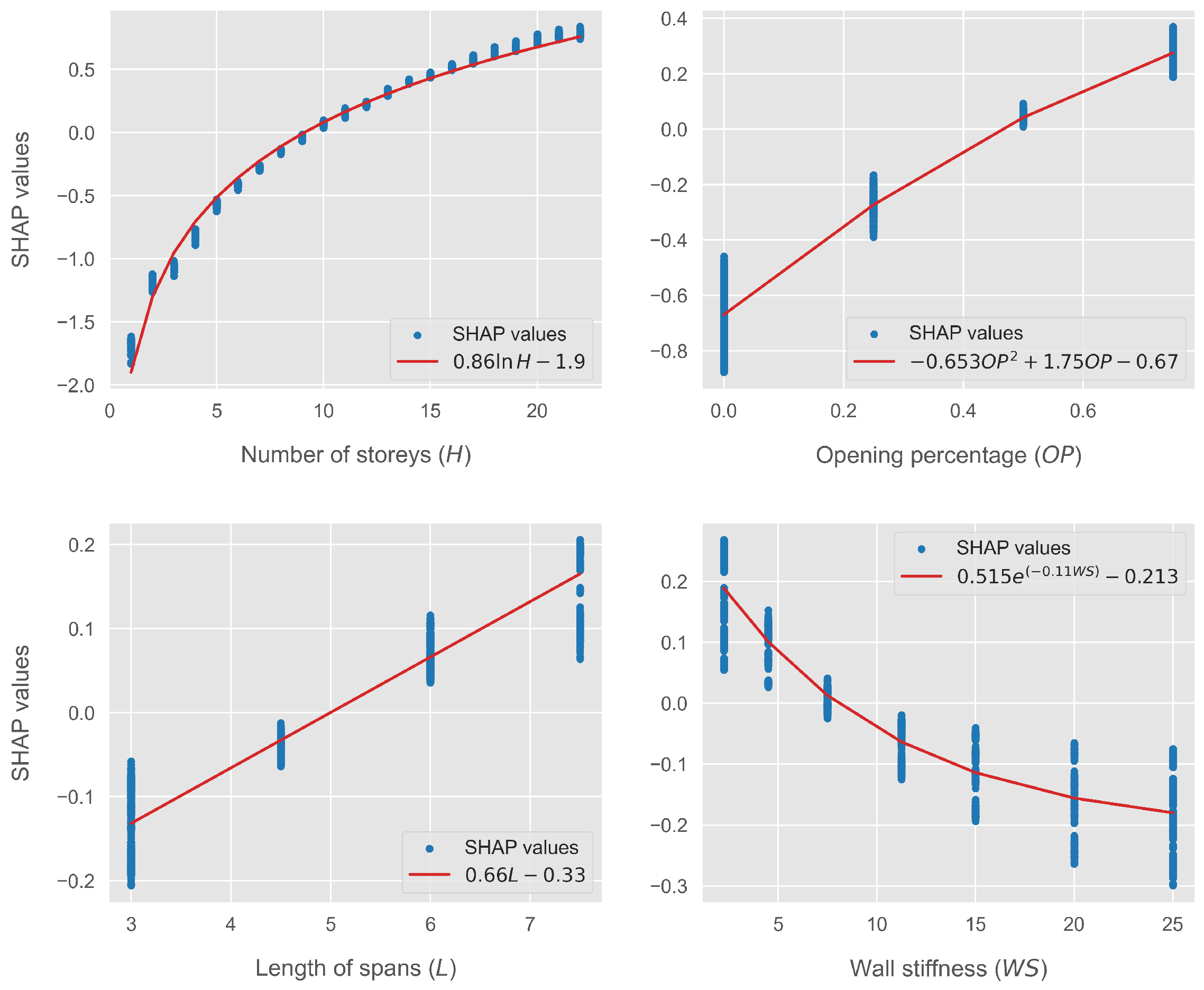

3.2. Regression Using SHAP

| Log-transformed | Original space | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | Test | Full dataset | Training | Test | Full dataset | |

| MAE | 0.1185 | 0.1217 | 0.1193 | 0.1174 | 0.1193 | 0.1179 |

| RMSE | 0.1485 | 0.1515 | 0.1493 | 0.1725 | 0.1707 | 0.1721 |

| 0.9706 | 0.9681 | 0.9700 | 0.9522 | 0.9510 | 0.9520 | |

4. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RC | Reinforced Concrete |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| SHAP | Shapley Additive Explanations |

| FUP | Fundamental Period |

| RCB_MI | Reinforced Concrete Building with Masonry Infills |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

References

- Penelis, G.; Kappos, A. Earthquake-Rresistant Concrete Structures; E and FN Spon. London, 1997.

- Elnashai, A.S.; Di Sarno, L. Fundamentals of Earthquake Engineering: From Source to Fragility; John Wiley & Sons, 2008.

- Theodoulidis, N.; Karakostas, C.; Lekidis, V.; Makra, K.; Margaris, B.; Morfidis, K.; Papaioannou, C.; Rovithis, E.; Salonikios, T.; Savvaidis, A. The Cephalonia, Greece, January 26 (M6. 1) and February 3, 2014 (M6. 0) earthquakes: near-fault ground motion and effects on soil and structures. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering 2016, 14, 1–38. [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriadou, A.; Karabinis, A.; Baltzopoulou, A. Fundamental Period versus Seismic Damage for Reinforced Concrete Buildings. Proc. 15th World Conf. Earthq. Eng. Lisboa, 2012.

- Bathe, K.J. Finite Element Procedures; Prentice Hall, 2006.

- Bhatt, P. Programming the Dynamic Analysis of Structures; Spon Press, 2002.

- European Committee for Standardization. Eurocode 8: design of structures for earthquake resistance-part 1: general rules, seismic actions and rules for buildings. European Standard EN 1998, 1, 2005.

- NZS3101: The Design of Concrete Structures. Technical report, Standards New Zealand, Wellington, 2006.

- Bureau of Indian Standards. Indian standard criteria for earthquake resistant design of structures-part 1: general provisions and buildings. Technical report, Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi, India, 2002.

- Egyptian Code for Computation of Loads and Forces in Structural and Building Works. Technical report, Housing and Building Research Center, Cairo, Egypt, 2012.

- AFPS. Recommendations for the redaction of rules relative to the structures and installation built in regions prone to earthquakes. Technical report, France Association of Earthquake Engineering, Paris, France, 1990.

- National Research Council. The National Building Code (NBC). Technical report, National Research Council, Ottawa, Canada, 1995.

- NEHRP Recommended Provisions for the Development of Seismic regulations for New Buildings. Technical report, Building Seismic Safety Council, Washington. D.C., USA, 1994.

- Uniform Building Code. Technical report, International Conference of Building Officials, Whittier, CA., USA, 1997.

- Tentative provisions for the development of seismic regulations for buildings. Technical report, Applied Technology Council, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1978.

- Minimum Design Loads for Buildings and Other Structures. Technical report, American Society of Civil Engineers, Reston, VA, USA, 2010.

- Building Standard Law of Japan. Technical report, Building Center of Japan, Tokyo, Japan, 2016.

- Recommended lateral force requirements and commentary. Technical report, Structural Engineers Association of California, Sacramento, CA, USA, 1999.

- Crawford, R.; Ward, H.S. Determination of the natural periods of buildings. Bulletin of the seismological Society of America 1964, 54, 1743–1756. [CrossRef]

- Bertero, V.V. Fundamental period of reinforced concrete moment-resisting frame structures; Number 87, John A. Blume Earthquake Engineering Center, Stanford, CA, USA, 1988.

- Goel, R.K.; Chopra, A.K. Period formulas for moment-resisting frame buildings. Journal of Structural Engineering 1997, 123, 1454–1461. [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.K.; Chopra, A.K. Period formulas for concrete shear wall buildings. Journal of Structural Engineering 1998, 124, 426–433. [CrossRef]

- Balkaya, C.; Kalkan, E. Estimation of fundamental periods of shear-wall dominant building structures. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics 2003, 32, 985–998.

- Hong, L.L.; Hwang, W.L. Empirical formula for fundamental vibration periods of reinforced concrete buildings in Taiwan. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics 2000, 29, 327–337.

- Verderame, G.M.; Iervolino, I.; Manfredi, G. Elastic period of sub-standard reinforced concrete moment resisting frame buildings. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering 2010, 8, 955–972. [CrossRef]

- Chiauzzi, L.; Masi, A.; Mucciarelli, M.; Cassidy, J.; Kutyn, K.; Traber, J.; Ventura, C.; Yao, F.; others. Estimate of fundamental period of reinforced concrete buildings: code provisions vs. experimental measures in Victoria and Vancouver (BC, Canada). 15th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, 2012, Vol. 3033.

- Salama, M.I. Estimation of period of vibration for concrete moment-resisting frame buildings. HBRC Journal 2015, 11, 16–21. [CrossRef]

- Hadzima-Nyarko, M.; Morić, D.; Draganić, H.; Štefić, T. Comparison of fundamental periods of reinforced shear wall dominant building models with empirical expressions. Tehnički Vjesnik 2015, 22, 685–694. [CrossRef]

- El-saad, M.N.A.; Salama, M.I. Estimation of period of vibration for concrete shear wall buildings. HBRC journal 2017, 13, 286–290. [CrossRef]

- Badkoubeh, A.; Massumi, A. Fundamental period of vibration for seismic design of concrete shear wall buildings. Scientia Iranica 2017, 24, 1010–1016. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.N.; El Kashif, K.F.; Salem, H.M. An investigation of the fundamental period of vibration for moment resisting concrete frames. Civil Engineering Journal 2019, 5, 2626–2642. [CrossRef]

- Shatnawi, A.S.; Al-Beddawe, E.H.; Musmar, M.A. Estimation of fundamental natural period of vibration for reinforced concrete shear walls systems. Earthquakes and Structures 2019, 16, 295–310.

- Alrudaini, T. Estimating vibration period of reinforced concrete moment resisting frame buildings. Research on Engineering Structures & Materials 2023, 9.

- Dominguez Morales, M. Fundamental period of vibration for reinforced concrete buildings; University of Ottawa, Canada, 2000.

- Amanat, K.M.; Hoque, E. A rationale for determining the natural period of RC building frames having infill. Engineering Structures 2006, 28, 495–502. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.S.; Kim, E.S. Evaluation of building period formulas for seismic design. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics 2010, 39, 1569–1583.

- Crowley, H.; Pinho, R. Revisiting Eurocode 8 formulae for periods of vibration and their employment in linear seismic analysis. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics 2010, 39, 223–235.

- Ricci, P.; Verderame, G.M.; Manfredi, G. Analytical investigation of elastic period of infilled RC MRF buildings. Engineering Structures 2011, 33, 308–319. [CrossRef]

- Asteris, P.G.; Repapis, C.C.; Cavaleri, L.; Sarhosis, V.; Athanasopoulou, A. On the fundamental period of infilled RC frame buildings. Structural Engineering and Mechanics 2015, 54, 1175–1200. [CrossRef]

- Asteris, P.G.; Repapis, C.C.; Tsaris, A.K.; Di Trapani, F.; Cavaleri, L.; others. Parameters affecting the fundamental period of infilled RC frame structures. Earthquakes and Structures 2015, 9, 999–1028. [CrossRef]

- Perrone, D.; Leone, M.; Aiello, M.A. Evaluation of the infill influence on the elastic period of existing RC frames. Engineering Structures 2016, 123, 419–433. [CrossRef]

- Asteris, P.G.; Repapis, C.C.; Repapi, E.V.; Cavaleri, L. Fundamental period of infilled reinforced concrete frame structures. Structure and Infrastructure Engineering 2017, 13, 929–941. [CrossRef]

- Al-Balhawi, A.; Zhang, B. Investigations of elastic vibration periods of reinforced concrete moment-resisting frame systems with various infill walls. Engineering Structures 2017, 151, 173–187. [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, S.; Fiore, A.; Uva, G. A new approach to predict the fundamental period of vibration for newly-designed reinforced concrete buildings. Journal of Earthquake Engineering 2022, 26, 6943–6968. [CrossRef]

- Harirchian, E.; Hosseini, S.E.A.; Jadhav, K.; Kumari, V.; Rasulzade, S.; Işık, E.; Wasif, M.; Lahmer, T. A review on application of soft computing techniques for the rapid visual safety evaluation and damage classification of existing buildings. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 43, 102536. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Ebad Sichani, M.; Padgett, J.E.; DesRoches, R. The promise of implementing machine learning in earthquake engineering: A state-of-the-art review. Earthquake Spectra 2020, 36, 1769–1801. [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Burton, H.V.; Huang, H. Machine learning applications for building structural design and performance assessment: State-of-the-art review. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 33, 101816. [CrossRef]

- Flah, M.; Nunez, I.; Ben Chaabene, W.; Nehdi, M.L. Machine learning algorithms in civil structural health monitoring: A systematic review. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2021, 28, 2621–2643. [CrossRef]

- Avci, O.; Abdeljaber, O.; Kiranyaz, S. Structural Damage Detection in Civil Engineering with Machine Learning: Current State of the Art. Sensors and Instrumentation, Aircraft/Aerospace, Energy Harvesting & Dynamic Environments Testing, Volume 7: Proceedings of the 39th IMAC, A Conference and Exposition on Structural Dynamics 2021. Springer, 2022, pp. 223–229.

- Haykin, S. Neural networks and learning machines. 3rd ed; Prentice Hall, 2009.

- Deka, P.C. A Primer on Machine Learning Applications in Civil Engineering; CRC Press, 2019.

- Chatterjee, P.; Yazdani, M.; Fernández-Navarro, F.; Pérez-Rodríguez, J. Machine Learning Algorithms and Applications in Engineering; CRC Press, 2023.

- Bishop, C. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer, 2006.

- Koutroumbas, K.; Theodoridis, S. Pattern Recognition, 4th Edition; Elsevier, 2008.

- Kose, M.M. Parameters affecting the fundamental period of RC buildings with infill walls. Engineering Structures 2009, 31, 93–102. [CrossRef]

- Asteris, P.G. The FP4026 Research Database on the fundamental period of RC infilled frame structures. Data in Brief 2016, 9, 704–709. [CrossRef]

- Asteris, P.G.; Tsaris, A.K.; Cavaleri, L.; Repapis, C.C.; Papalou, A.; Di Trapani, F.; Karypidis, D.F. Prediction of the fundamental period of infilled RC frame structures using artificial neural networks. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2016, 2016, 5104907. [CrossRef]

- Asteris, P.G.; Nikoo, M. Artificial bee colony-based neural network for the prediction of the fundamental period of infilled frame structures. Neural Computing and Applications 2019, 31, 4837–4847. [CrossRef]

- Charalampakis, A.E.; Tsiatas, G.C.; Kotsiantis, S.B. Machine learning and nonlinear models for the estimation of fundamental period of vibration of masonry infilled RC frame structures. Engineering Structures 2020, 216, 110765. [CrossRef]

- Somala, S.N.; Karthikeyan, K.; Mangalathu, S. Time period estimation of masonry infilled RC frames using machine learning techniques. Structures 2021, 34, 1560–1566. [CrossRef]

- Mirrashid, M.; Naderpour, H. Computational intelligence-based models for estimating the fundamental period of infilled reinforced concrete frames. Journal of Building Engineering 2022, 46, 103456. [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.S. ANFIS: adaptive-network-based fuzzy inference system. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics 1993, 23, 665–685. [CrossRef]

- Yahiaoui, A.; Dorbani, S.; Yahiaoui, L. Machine learning techniques to predict the fundamental period of infilled reinforced concrete frame buildings. Structures 2023, 54, 918–927. [CrossRef]

- Thisovithan, P.; Aththanayake, H.; Meddage, D.; Ekanayake, I.; Rathnayake, U. A novel explainable AI-based approach to estimate the natural period of vibration of masonry infill reinforced concrete frame structures using different machine learning techniques. Results in Engineering 2023, 19, 101388. [CrossRef]

- Adadi, A.; Berrada, M. Peeking inside the black-box: a survey on explainable artificial intelligence (XAI). IEEE Access 2018, 6, 52138–52160. [CrossRef]

- Seismosoft. SeismoStruct-A computer program for static and dynamic nonlinear analysis of framed structures, 2013.

- Crisafulli, F.J.; Carr, A.J. Proposed macro-model for the analysis of infilled frame structures. Bulletin of the New Zealand society for earthquake engineering 2007, 40, 69–77. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Annals of Statistics 2001, pp. 1189–1232.

- Natekin, A.; Knoll, A. Gradient boosting machines, a tutorial. Frontiers in Neurorobotics 2013, 7, 21. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30.

- Shapley, L.S. Notes on the n-person game-II: The value of an n-person game 1951.

- Goldstein, A.; Kapelner, A.; Bleich, J.; Pitkin, E. Peeking inside the black box: Visualizing statistical learning with plots of individual conditional expectation. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics 2015, 24, 44–65. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.G.; Lee, S.I. Consistent individualized feature attribution for tree ensembles. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.03888 2018.

| MAE | RMSE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feature | Fitted curve | Training | Test | Training | Test |

| Number of storeys | 0.0593 | 0.0623 | 0.0763 | 0.0801 | |

| 0.0823 | 0.0837 | 0.1011 | 0.1045 | ||

| 0.0546 | 0.0575 | 0.0740 | 0.0797 | ||

| Opening percentage | 0.0758 | 0.0778 | 0.0888 | 0.0914 | |

| 0.0725 | 0.0763 | 0.0916 | 0.0955 | ||

| Length of spans | 0.0246 | 0.0308 | 0.0330 | 0.0441 | |

| 0.0358 | 0.0350 | 0.0420 | 0.0414 | ||

| Wall stiffness | 0.0450 | 0.0439 | 0.0544 | 0.0533 | |

| 0.0431 | 0.0438 | 0.0535 | 0.0538 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).