Submitted:

05 September 2024

Posted:

09 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Quantum State Preparation: Bob prepares qubits in one of the four initial states: (polarization states) or (phase states), forming the basis of the communication.

- Initial Transmission to Alice: Bob sends these qubits to Alice via the quantum channel.

- Eavesdropping Detection: Alice randomly selects some received qubits for immediate measurement in basis X or Z. The results are communicated to Bob through the classical service channel. Bob then verifies if the measured qubits match the initially prepared states. Any discrepancy indicates potential eavesdropping by Eve, causing the process to terminate if the error rate () exceeds a predefined threshold. Otherwise, Alice and Bob proceed to estimate the secrecy capacity ().

- Message Encoding: Alice encodes the message bits () into codewords () using a predetermined coding scheme.

- Photon Modulation: Alice modulates the remaining qubits by applying either the identity operator (I) or the unitary operator (U) based on the bit values ’0’ or ’1’ of . These modulated photons are then stored in a quantum memory.

- Return Transmission to Bob: The modulated photons are sent back to Bob through the same quantum channel.

- Demodulation and Decoding: Bob demodulates the received photons to retrieve the codewords (), then decodes these to extract the original message ().

- Eavesdropping Detection: The immediate measurement of randomly selected qubits allows Alice and Bob to detect any interference by Eve, leveraging the fundamental principles of quantum mechanics where any measurement alters the quantum state.

- Quantum Memory Utilization: Unlike protocols that operate memory-free, DL04 requires quantum memory, ensuring qubits are stored securely between initial transmission and modulation. This aids in maintaining the integrity and sequence of transmitted qubits.

- Secrecy Capacity Estimation: The protocol allows for precise estimation of the secrecy capacity (), which is crucial for determining the security of the communication channel.

- Two-Way Transmission: The bidirectional flow of qubits between Alice and Bob enhances the robustness of the protocol by providing an additional layer for detecting and mitigating eavesdropping attempts.

- Introduction of a novel LF QSDC system designed for Web 3.0 networks.

- Introduction of a detailed and practical road map to the implementation of LF QSDC into global communication networks.

- Development and optimization of a quantum-aware LDPC and PAT technology to enhance quantum communication reliability and efficiency.

- Proposal of a novel AQCA aimed at mitigating atmospheric disturbances and improving security over long distances satellite communication.

2. Long-Distance Free-Space QSDC Overview

2.1. Quantum State Preparation and Encoding

2.1.1. Basis Determination ():

- If , the basis is computational, with states .

-

If , the basis is superpositional, where further dictates the specific state:

- −

- : State becomes

- −

- : State becomes

- If , the phase states remain as initially encoded.

-

If , the phase states are swapped:

- −

- becomes and vice versa.

2.2. Measurement Protocols and Two-Way Communication

- If , he measures in the basis:

- If , he measures in the basis:

2.3. Integration of Advanced Quantum Technologies

- Quantum-Aware LDPC Coding: Specifically designed for quantum information, these codes correct errors that occur during the quantum state transmission, thus ensuring that the integrity and secrecy of the data are maintained even over long distances.

- Pointing, Acquisition, and Tracking (PAT) Systems: These technologies are critical for maintaining the alignment of the quantum communication link, especially in dynamic environments such as satellite communications, where precision pointing is crucial for successful data transmission.

- Atmospheric Quantum Correction Algorithms: These algorithms are designed to compensate for the quantum signal degradation caused by the atmosphere. By correcting errors induced by atmospheric turbulence, these algorithms significantly improve the reliability and stability of the quantum channel.

2.4. Security Checking Process

- Error Rate Estimation: Alice and Bob share a portion of their measurement results to estimate the quantum bit error rate (QBER). If the QBER exceeds a predefined threshold, the communication is deemed insecure, and the process is aborted.

- Entanglement Verification: By verifying the entanglement of the transmitted quantum states, Alice and Bob can ensure that no eavesdropping has occurred. This involves comparing the measurement results to check for correlations consistent with the expected entangled states.

- Classical Post-Processing: Any discrepancies identified during the verification steps are corrected through classical post-processing techniques, such as error correction and privacy amplification. This ensures that the final shared data is secure and free from eavesdropping.

3. Lossless and Secure Long-Distance Free-Space Transmission Techniques

3.1. Quantum-Aware LDPC Coding

3.1.1. LDPC Code Parameter Optimization

- Extended Definition and Impact: The degree distribution of an LDPC code, represented by the polynomials for variable nodes and for check nodes, fundamentally determines the code’s performance in terms of error correction efficiency and rate. These polynomials dictate how bits are interconnected within the LDPC graph.

- Technical Enhancement: A comprehensive optimization function that not only maximizes mutual information I(X; Y) and minimizes QBER but also considers the decoding threshold and the code rate. The optimization can integrate more complex constraints related to the noise model of the quantum channel.

-

New Mathematical Formulation:Optimization Goal:Subject to:Here, represents the additional constraint related to the code rate.

-

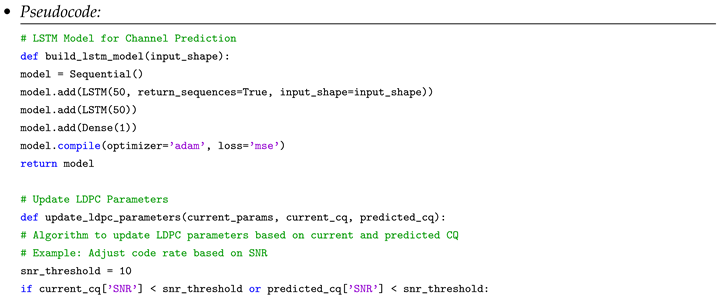

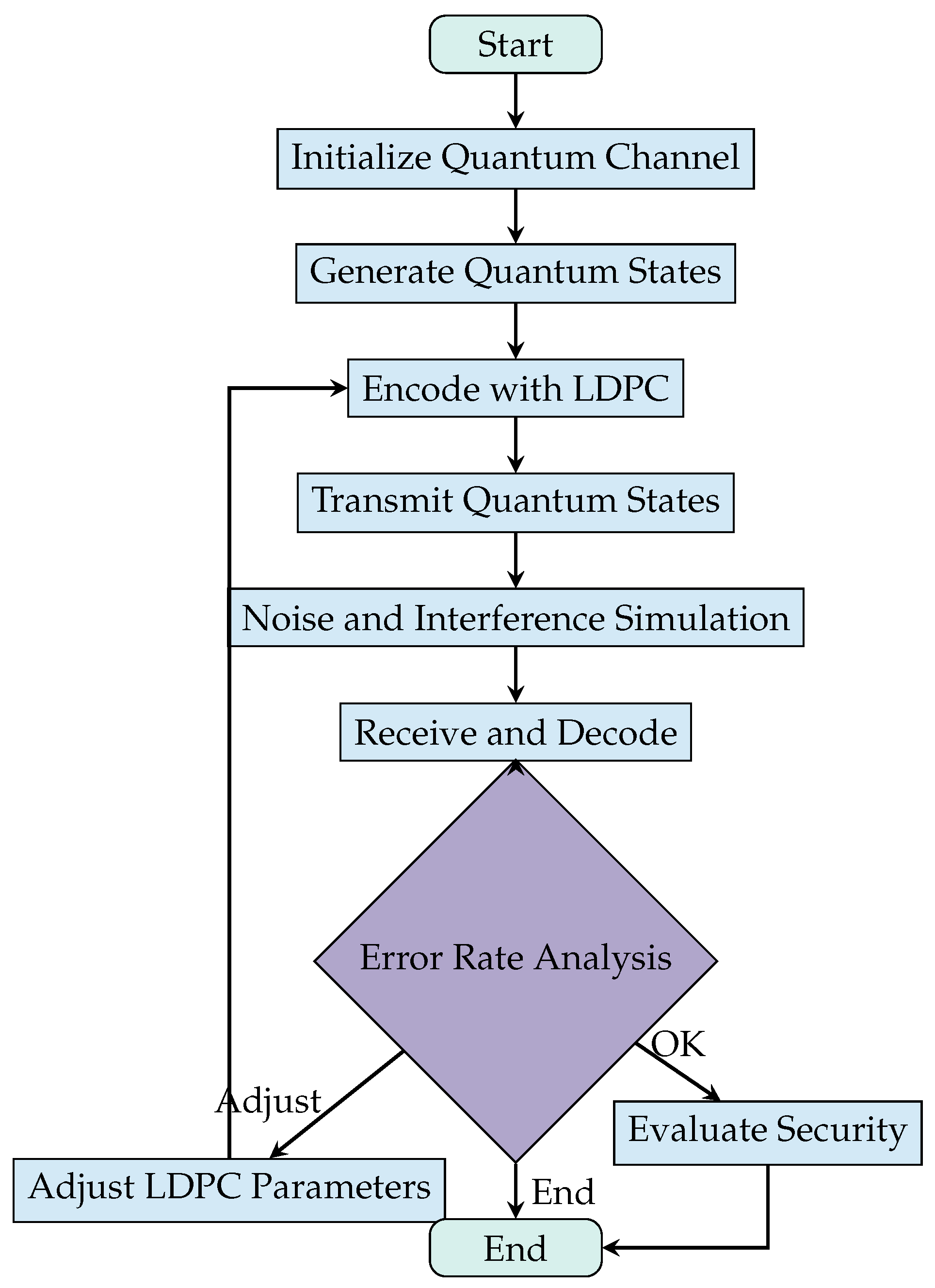

Machine Learning Prediction and Iterative Update Algorithm: a machine learning and an iterative update algorithm designed to predict upcoming alterations in the quantum channel and modify the LDPC code parameters, guided by immediate feedback from the quantum communication system.

- Initialization: Set initial LDPC code parameters based on average channel conditions.

-

Real-time Feedback Loop:

- *

- Collect real-time CQ data.

- *

- Adjust LDPC parameters for immediate channel conditions.

-

Predictive Adjustment:

- *

- Use the ML model to predict short-term future CQ.

- *

- Preemptively adjust LDPC parameters based on predictions.

-

Iterative Update:

- *

- Continuously repeat steps 2 and 3.

- *

- Employ a decay factor to balance between recent adjustments and new predictions.

3.1.2. Adaptive Decoding Algorithm with Graph Neural Network Enhanced Belief Propagation and Adaptive Iteration

- Input: Messages from each node, current iteration number, and additional features like channel conditions.

- Architecture: Utilize a GNN architecture capable of handling graph-structured data. Layers can include graph convolutional networks (GCN) or Graph Attention Networks (GAT).

- Output: Adjusted messages and probability of error for each node.

- Dynamically Adjust Iterations: Based on channel conditions and convergence rate, the number of iterations, T, is adapted.

- Stopping Criterion: Utilize error patterns and rate of convergence to determine when to stop the iterations.

- Let be the message from node i to node j at iteration t.

- GNN output influences the update rule:

- Adaptive iteration count T based on GNN feedback and channel conditions.

- Pseudocode:

3.1.3. Security Enhancement Techniques

- Employ decoy states with varying intensities to estimate channel parameters.

- Use statistical methods to analyze the difference in detection rates between signal and decoy states to estimate and detect eavesdropping.

- The estimation can be formulated as solving a set of linear inequalities derived from decoy state intensities and detection rates.

3.2. PAT Technologies

3.2.1. Design

3.2.2. Performance Evaluation and Optimization Algorithms

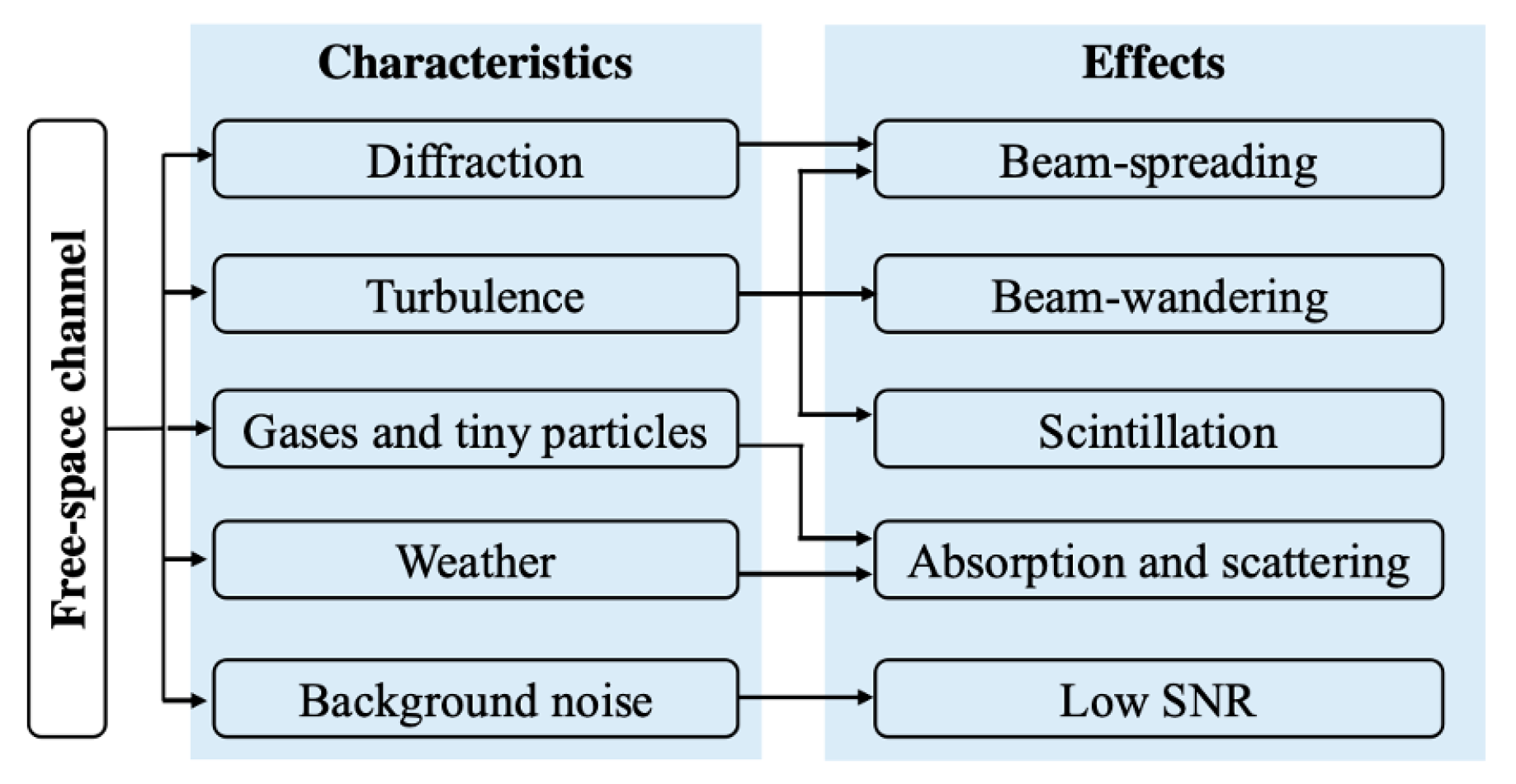

3.3. Atmospheric Quantum Correction Algorithm

3.3.1. Design

3.3.2. Mathematical Formulation

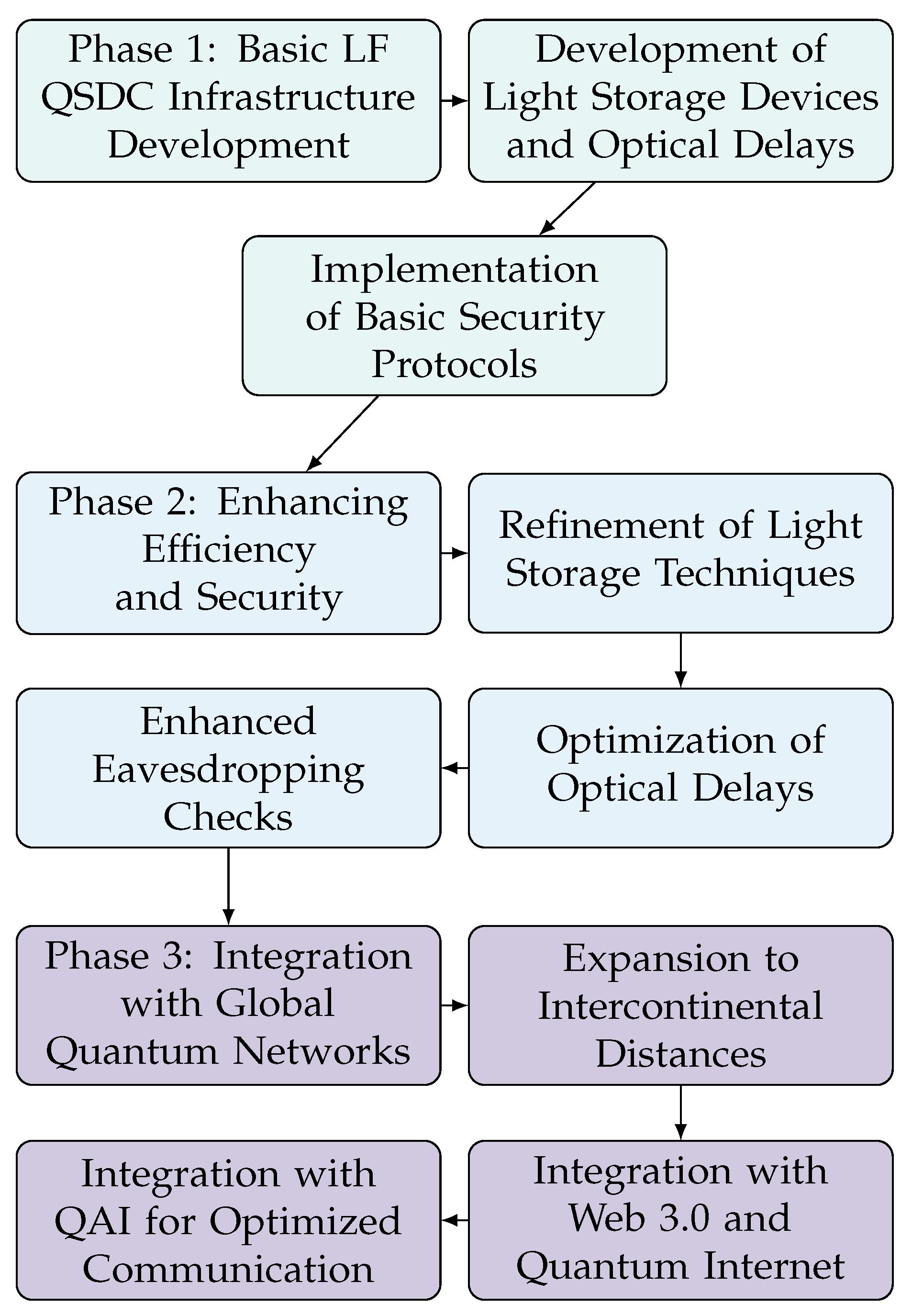

3.4. Integration with LF QSDC Protocol

- The transmitter and the receiver measure the atmospheric parameters, such as the Fried parameter, the absorption coefficient, and the scattering cross section, using the disturbance modeler module of the AQCA.

- The transmitter and the receiver select the appropriate quantum code, such as a CV code or a DV code, based on the quantum signal’s modulation scheme and the atmospheric parameters, using the quantum error corrector module of the AQCA.

- The transmitter encodes the quantum state into the quantum signal, using a quantum source and a quantum modulator, and applies the quantum code to the quantum signal, using the encoding step of the QEC process.

- The transmitter directs the quantum signal toward the receiver, using the pointing device of the PAT system, and adjusts the quantum signal’s path in real-time, using the adaptive optics system module of the AQCA.

- The receiver detects the incoming quantum signal, using the tracking device of the PAT system, and measures the quantum signal’s phase distortions, using the wavefront sensor of the adaptive optics system.

- The receiver compensates the quantum signal’s phase distortions, using the deformable mirror of the adaptive optics system, and enhances the quantum signal’s SNR, using the signal enhancer and recoverer module of the AQCA.

- The receiver measures the quantum signal, using a quantum detector, and applies the quantum code to the quantum signal, using the syndrome measurement and decoding steps of the QEC process, to recover the original quantum state.

- The transmitter and the receiver exchange classical information, such as basis choices, error correction codes, and privacy amplification keys, using a classical channel, such as a radio or optical link.

- The transmitter and the receiver perform post-processing steps, such as error correction, privacy amplification, and authentication, to ensure the security and reliability of the quantum communication.

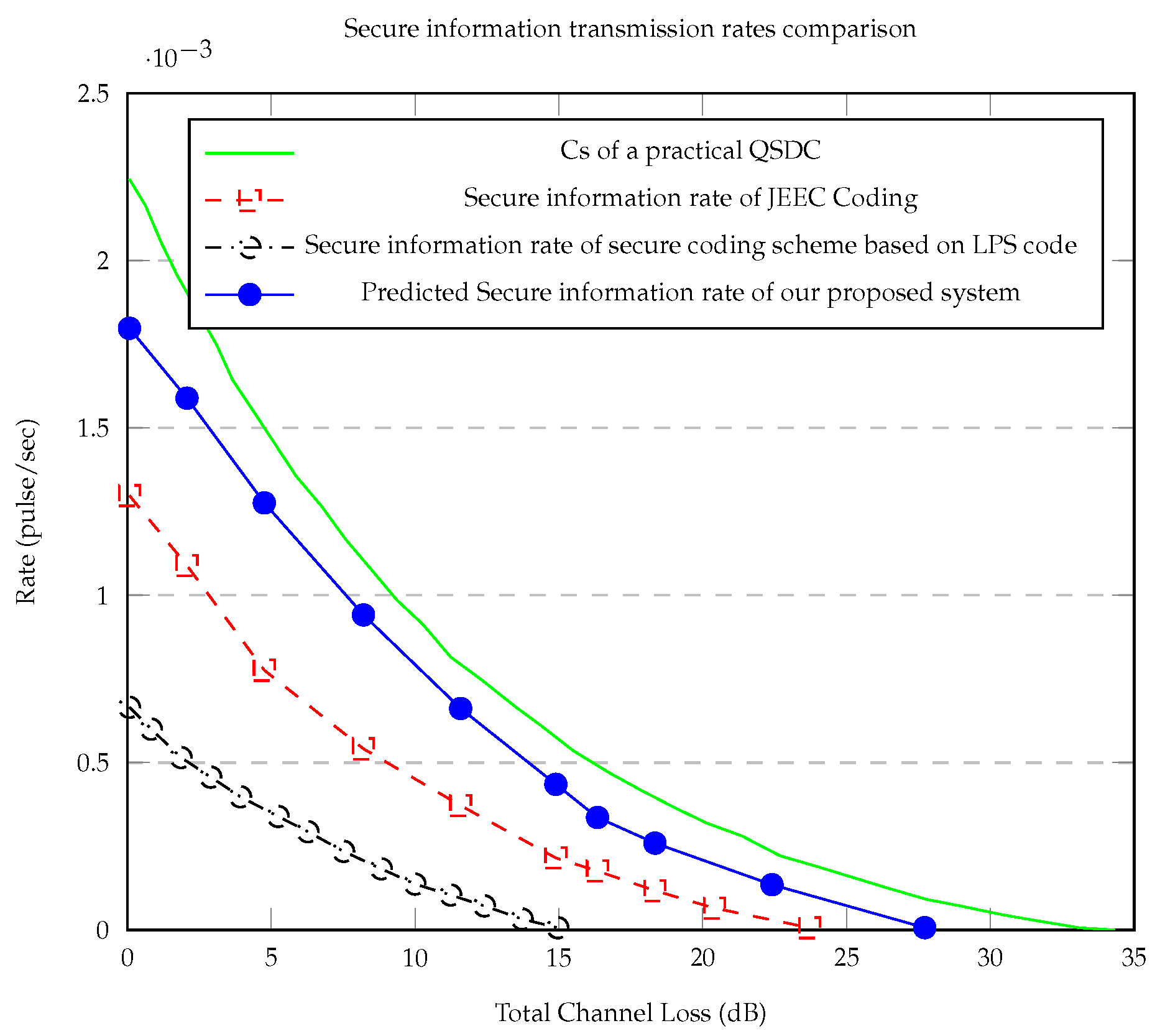

4. LF QSDC Simulation Plan and Analysis

4.1. Simulation Plan

4.2. Predicted Results and Analysis

5. Implementation Plan for LF QSDC

5.1. Technical Implementation of LF QSDC

5.1.1. 1-Way Transmission Protocols in Free-Space Channel

5.1.2. Experimental Implementation

5.2. Feasibility and Adaptability of Satellite-based QSDC

5.2.1. Feasibility of Satellite Communication with LF QSDC

5.2.2. Expanding Feasibility with LF QSDC

5.3. Web 3.0 Compatibility

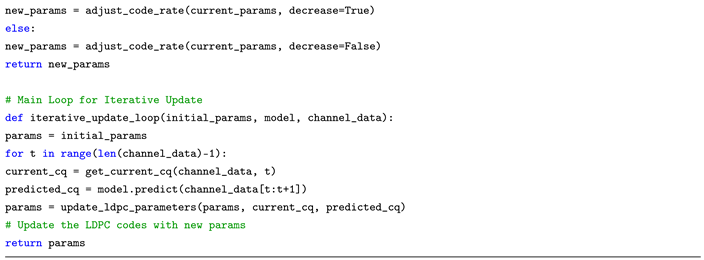

5.4. Stages of Gradual Implementation

5.4.1. Phase 1: Development of Basic LF QSDC Infrastructure

5.4.2. Phase 2: Enhancing Efficiency and Security

5.4.3. Phase 3: Integration with Global Quantum Networks

5.5. Business Case of LF QSDC in The Web 3.0 Era

6. Discussion

6.1. Comparison With Similar Protocols

6.1.1. Security

6.1.2. Distance

6.1.3. Channel Loss and Atmospheric Disturbances

6.1.4. Cost

6.2. Limitations and Future Work

6.2.1. Theoretical Challenges

- Quantum Decoherence and Noise: Quantum states are highly susceptible to decoherence and environmental noise, which can severely limit the distance over which LF QSDC can be effectively implemented.

- Security Proofs: Complete, universally accepted security proofs for LF QSDC under all potential attack scenarios are challenging to develop, raising concerns about its absolute security.

6.2.2. Technological Constraints

- Quantum Sources and Detectors: The efficiency and reliability of quantum sources (e.g., single-photon sources) and detectors are critical, yet current technologies may not provide the necessary performance for long-distance communication.

- Atmospheric Interference: Free-space transmission is significantly affected by atmospheric conditions (e.g., cloud cover, atmospheric turbulence), which can degrade the quantum signal over long distances.

6.2.3. Implementation Challenges

- Infrastructure Development: Establishing a global LF QSDC network requires significant investment in both ground-based and potentially satellite-based infrastructure, posing a substantial financial and logistical challenge.

- Interoperability: Compatibility with existing communication technologies and standards is crucial for widespread adoption, necessitating complex integration efforts.

6.2.4. Impact Considerations

- Scalability: While promising for point-to-point communication, scaling LF QSDC to a multi-node quantum network presents considerable technical challenges.

- Accessibility: The high cost and complexity of LF QSDC technology may limit its accessibility, particularly in developing regions, potentially exacerbating the digital divide.

- Regulatory and Ethical Issues: The deployment of LF QSDC might raise questions regarding regulation, data sovereignty, and privacy, requiring careful consideration and potentially new legal frameworks.

7. Conclusions

8. Acknowledgement

9. Data Availability

References

- P. W. Shor, “Algorithms for quantum computation: Discrete logarithms and factoring,” in Proc. 35th Annu. Symp. Foundations of Computer Science. IEEE, 1994, pp. 124–134.

- L. K. Grover, “Quantum mechanics helps in searching for a needle in a haystack,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 79, no. 2, pp. 325–328, 1997.

- J. G. Ren et al., "Ground-to-satellite quantum teleportation," Nature, vol. 549, pp. 70-73, Sept. 2017.

- S. Nauerth et al., "Air-to-ground quantum communication," Nature Photonics, vol. 7, pp. 382-386. June 2013.

- Q. Zhang et al., "Satellite-based entanglement distribution over 1200 kilometers," Science, vol. 356, no. 6343, pp. 1140-1144. June 2017.

- J. Yin et al., "Satellite-based quantum-secure time transfer," Nature Communications, vol. 11, no. 1, Article no. 4186, Aug. 2020.

- L. Zhou, Y. B. Sheng, and G. L. Long, "Device-independent quantum secure direct communication against collective attacks," Sci. Bull. (Beijing), vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 12-14, 2020.

- H. Zhang et al., "Realization of quantum secure direct communication over 100 km fiber with time-bin and phase quantum states," Light: Science & Applications, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 83, 2022.

- X. Liu, D. Luo, G. L. Lin, Z. H. Chen, C. F. Huang, S. Z. Li, C. X. Zhang, Z. R. Zhang, and K. J. Wei, “Fiber based quantum secure direct communication without active polarization compensation,” Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron., vol. 65, no. 12, p. 120311, 2022.

- L. Zhou, B. W. Xu, W. Zhong, and Y. B. Sheng, “Device-independent quantum secure direct communication with single-photon sources,” Phys. Rev. Appl., vol. 19, no. 1, p. 014036, 2023.

- I. Paparelle, F. Mousavi, F. Scazza, A. Bassi, M. Paris, and A. Zavatta, “Practical quantum secure direct communication with squeezed states,” arXiv:2306.14322, 2023.

- Y. B. Sheng, L. Zhou, and G. L. Long, “One-step quantum secure direct communication,” Sci. Bull. (Beijing), vol. 67, no. 4, p. 367, 2022.

- L. Zhou and Y. B. Sheng, “One-step device-independent quantum secure direct communication,” Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron., vol. 65, no. 5, p. 250311, 2022.

- D. Pan et al., "The Evolution of Quantum Secure Direct Communication: On the Road to the Qinternet," in IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials. [CrossRef]

- Z. Sun, L. Song, Q. Huang, L. Yin, G. Long, J. Lu, L. Hanzo, “Toward practical quantum secure direct communication: A quantum-memory-free protocol and code design,” IEEE Transactions on Communications, vol. 68, no. 9, pp. 5778–5792, 2020.

- Z. Gao, T. Li, and Z. Li, “Long-distance measurement-device–independent quantum secure direct communication,” EPL (Europhys Lett.), vol. 125, no. 4, p. 40004, 2019.

- W. Zhang, D. Ding, Y. Sheng, L. Zhou, B. Shi, and G. Guo, “Quantum secure direct communication with quantum memory,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 118, no. 22, p. 220501, 2017.

- L. Yin, C. Jiang, C. Jiang, N. Ge, L. Kuang, and M. Guizani, “A communication framework with unified efficiency and secrecy,” IEEE Wireless Communications, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 133–139, 2019.

- F. Deng and G. Long, “Secure direct communication with a quantum one-time pad,” Phys. Rev. A, vol. 69, no. 5, p. 052319, 2004.

- F. Deng, G. Long, and X. Liu, “Two-step quantum direct communication protocol using the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen pair block,” Phys. Rev. A, vol. 68, no. 4, p. 042317, 2003.

- Y. X. Xiao, L. Zhou, W. Zhong, M. M. Du, and Y. B. Sheng, “The hyperentanglement-based quantum secure direct communication protocol with single-photon measurement,” Quantum Inform. Process., vol. 22, no. 9, p. 339, 2023.

- M. Bailly, E. Perez, “Pointing, acquisition, and tracking system of the European SILEX program: a major technological step for intersatellite optical communication,” in Free-Space Laser Communication Technologies III, vol. 1417, pp. 142-157, 1991.

- I. B. Djordjevic, O. Milenkovic, and B. Vasic, “Generalized low-density parity-check codes for optical communication systems,” J. Lightwave Technol., vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 1939–1946, 2005.

- G. Yue, L. Ping, and X. Wang, “Generalized low-density parity-check codes based on Hadamard constraints,” IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory, vol. 53, no. 3, pp. 1058–1079, 2007.

- Z. Sun, R. Qi, Z. Lin, L. Yin, G. Long, and J. Lu, “Design and implementation of a practical quantum secure direct communication system,” in Proc. IEEE GlobeCom Conf. Workshops, IEEE, 2018, pp. 1–6.

- C. Wang, F. Deng, G. Long, “Multi-step quantum secure direct communication using multi-particle Green–Horne–Zeilinger state,” Optics Communications, vol. 253, nos. 1-3, pp. 15–20, 2005.

- P. Maunz, D. Moehring, S. Olmschenk, et al. “Quantum interference of photon pairs from two remote trapped atomic ions,” Nature Phys, vol. 3, pp. 538–541, 2007.

- C. Bennett, H., G. Brassard, C. Crépeau, and U. M. Maurer. “Generalized privacy amplification,” IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory, vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 1915-1923, 1995.

- J. Carter, L., and M. N. Wegman. “Universal classes of hash functions,” J. Comput. Syst. Sci., vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 143-154, 1979.

- J. Hu, B. Yu, M. Jing, L. Xiao, S. Jia, G. Qin, and G. L. Long. “Experimental quantum secure direct communication with single photons,” Light: Science and Applications, vol. 5, no. 9, e16144, 2016.

- Z. Babar, P. Botsinis, D. Alanis, S. X. Ng, and L. Hanzo. “Fifteen years of quantum LDPC coding and improved decoding strategies,” IEEE Access, vol. 3, pp. 2492–2519, 2015.

- Z. Zhou, Y. Sheng, P. Niu, L. Yin, G. Long, and L. Hanzo. “Measurement-device-independent quantum secure direct communication,” Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy, vol. 63, no. 3, 230362, 2020.

- J. Roffe, "Towards practical quantum LDPC codes," Quantum Views, vol. 5, p. 63, Nov. 2021. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- M. Ghilea et al., "Quasi-cyclic multi-edge LDPC codes for long-distance quantum cryptography," npj Quantum Information, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41534-021-00426-1.

- F. A. Mele, L. Lami, and V. Giovannetti, "Quantum optical communication in the presence of strong attenuation noise," Physical Review A, vol. 106, no. 042437, 2022. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- S. Zafar and H. Khalid, “Free space optical networks: applications, challenges and research directions,” Wireless Personal Communications, vol.

- H. Kaushal, V. K. Jain and S. Kar, “Free-space optical channel models,” in Free Space Optical Communication, New Delhi, India: Springer, 2017, pp. 9-41.

- A. M. Al-Kinani, A. A. Al-Habash, A. A. Al-Habash and A. A. Al-Habash, “A survey of hybrid free space optics communication networks to overcome atmospheric turbulence,” Entropy, vol. 24, no. 11, p. 1573, 2022.

- A. Avella et al., “Characterization of free-space quantum channels,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.05700, 2018.

- T. Ye, and Z. Ji, “Multi-user quantum private comparison with scattered preparation and one-way convergent transmission of quantum states”, arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.04631, 2021.

- M.Xiao, and C. Ma, “Fault-tolerant quantum private comparison protocol”, International Journal of Theoretical Physics, vol. 61, no. 1, p. 41, 2022.

- J. Liu, Q. Wang, Y. Yang, and Q. Wen, “Quantum private comparison protocol based on high-dimensional quantum states”, Quantum Information Processing, vol. 13, no. 11, pp. 2391-2404, 2014.

- Pan D, Lin Z, Wu J, et al. Experimental free-space quantum secure direct communication and its security analysis[J]. Photonics Research, 2020, 8(9): 1522-1531.

- R. Qi, Y. Zhang, S. Wang, H. Li, Z. Wang, S. Wang, X. Chen, and J.-W. Pan, “Experimental demonstration of free-space quantum secure direct communication with single photons”, Light: Science and Applications, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 28, 2020.

- G. Vallone et al., “Adaptive real time selection for quantum key distribution in lossy and turbulent free-space channels”, arXiv preprint arXiv:1404.1272, 2014.

- L.-C. Xu, H.-Y. Chen, N.-R. Zhou, and L.-H. Gong, “Multi-party semi-quantum secure direct communication protocol with cluster states”, International Journal of Theoretical Physics, vol. 59, no. 6, pp. 2175-2186, 2020.

- R. Qi et al., “Implementing a practical quantum secure direct communication system,” Light: Science and Applications, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 21, 2019.

- J.-G. Ren et al., “Ground-to-satellite quantum teleportation,” Nature, vol. 549, no. 7670, pp. 70-73, 2017.

- S.-K. Liao et al., “Satellite-to-ground quantum key distribution,” Nature, vol. 549, no. 7670, pp. 43-47, 2017.

- A. V. Khmelev et al., “Semi-Empirical Satellite-to-Ground Quantum Key Distribution Model for Realistic Receivers,” Entropy, vol. 25, no. 4, p. 670, 2023.

- P. Panteleev and G. Kalachev, “Degenerate Quantum LDPC Codes With Good Finite Length Performance,” Quantum, vol. 5, p. 585, 2021.

- P. Panteleev and G. Kalachev, “Layered Decoding of Quantum LDPC Codes,” IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, vol. 66, no. 8, pp. 5198-5209, 2020.

- J. Roffe, “Towards practical quantum LDPC codes,” Quantum Views, vol. 5, p. 63, 2021.

- M. T. Toledo, “Process Analytical Technology (PAT) - Enhance Quality and Efficiency,” 2021. [Online].

- J. Wang et al., “Direct and full-scale experimental verifications towards ground-satellite quantum key distribution,” Nature Photonics, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 387-393, 2013.

- Z. Cao et al., “Continuous-Variable Quantum Secure Direct Communication Based on Gaussian Mapping,” Physical Review Applied, vol. 16, no. 2, p. 024012, 2021.

- S. Goswami and S. Dhara, “Satellite Relayed Global Quantum Communication without Quantum Memory,” arXiv:2306.12421, 2021.

- G. Long, H. Zhang “Practical quantum secure direct communication,” 2020 Cross Strait Radio Science and Wireless Technology Conference (CSRSWTC). IEEE, 2020, 1-3.

- V. E. Balasubramanian et al., “Quantum communication using satellites,” Journal of Physics: Photonics, vol. 3, no. 3, p. 032001, 2021.

- E. Perrier, “The Quantum Governance Stack: Models of Governance for Quantum Information Technologies,” Digital Society, vol. 1, no. 1, p. 22, 2022.

- M. Kop, “Establishing a Legal-Ethical Framework for Quantum Technology,” Yale Journal of Law and Technology, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1-40, 2021.

- D. Pan, X.-T. Song, and G.-L. Long, “Free-Space Quantum Secure Direct Communication: Basics, Progress, and Outlook,” Advanced devices and instrumentation, vol. 4, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Zhu et al., “Experimental long-distance quantum secure direct communication,” arXiv:1710.07951, Oct. 2017.

- S. Pirandola et al., “Advances in quantum cryptography,” Adv. Opt. Photon., vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 1012–1236, Dec. 2020.

- QANplatform, “Quantum-resistant security,” [Online]. Available: https://learn.qanplatform.com/technology/technology-features/quantum-resistant-security.

- J. Liu et al., “Quantum-secure blockchain with efficient verification based on quantum key distribution,” Sci. Rep., vol. 10, Article 10677, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Kayal and S. Mandal, “Quantum secure direct communication using quantum key distribution and quantum encryption,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Adv. Comput. Commun. Inform. (ICACCI), Bangalore, India, Sep. 2018, pp. 1566–1571. [CrossRef]

- Min-Jie W, Wei P. Quantum secure direct communication based on authentication[J]. Chinese Physics Letters, 2008, 25(11): 3860.

- J. Wang et al., “Drone-based entanglement distribution towards mobile quantum networks,” Natl. Sci. Rev., vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 921–930, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Yin et al., “Long-distance and secure quantum key distribution over a free-space channel,” Nat. Photon., vol. 15, pp. 41–45, Jan. 2021.

- M. A. Nielsen and I. L. Chuang, Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, 10th ed. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010.

- A. K. Patra and S. K. Jana, “A new quantum secure direct communication protocol using decoherence-free subspace,” arXiv:2211.15941, Nov. 2021, [Online]. Available.

- S. Mexicana De Física et al., “Improved performance of the cryptographic key distillation protocol of an FSO/CV-QKD system on a turbulent channel using an adaptive LDPC encoder,” Revista Mexicana de Física, vol. 63, pp. 268–274, 2017, Accessed: Feb. 08, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/570/57050507008.pdf.

- J. Yin et al., “Quantum teleportation and entanglement distribution over 100-kilometre free-space channels,” Nature, vol. 488, no. 7410, pp. 185–188, 2012. [CrossRef]

- X.-S. Ma et al., “Quantum teleportation using active feed-forward between two Canary Islands,” 2012, Accessed: Feb. 08, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1205.3909.pdf.

| Category | Type of Protocol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LF QSDC | DL04 Protocol | Memory-Free DL04 | QKD | |

| Communication Distance | Long-distance (intercontinental) | Moderate distance | Moderate distance | Moderate distance |

| Security Level | High (no key exchange required) | High (can transmit secure messages without key exchange) | High (can transmit secure messages without key exchange) | High (key exchange fundamental) |

| Implementation Complexity | Moderate (enhanced by PAT technologies) | High (requires quantum memory) | Moderate (no quantum memory required) | Low (proven by ample experimentation) |

| Suitability for Globalized Web 3.0 | Highly suitable | Moderately suitable | Moderately suitable | Less suitable for global scale |

| Atmospheric Disturbances Resistance | Strong (mitigated by adaptive optics) | Moderate (susceptible to some atmospheric effects) | Moderate (susceptible to some atmospheric effects) | Weak (highly susceptible to atmospheric effects) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).