Submitted:

13 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. PQC-Based PKE Protocols for Using PQC Algorithm in Application

3.1. PQC Standalone PKE Protocol

| Algorithm 1 PQC standalone PKE Protocol |

|

3.2. PQC-AES Hybrid PKE Protocol

| Algorithm 2 PQC-AES hybrid PKE Protocol |

|

4. Practical Implementation of PQC-Based PKE Protocols

4.1. Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) Uses in Applications

4.1.1. Real-World Scenario Use Cases for Proposed PQC-Based Protocols

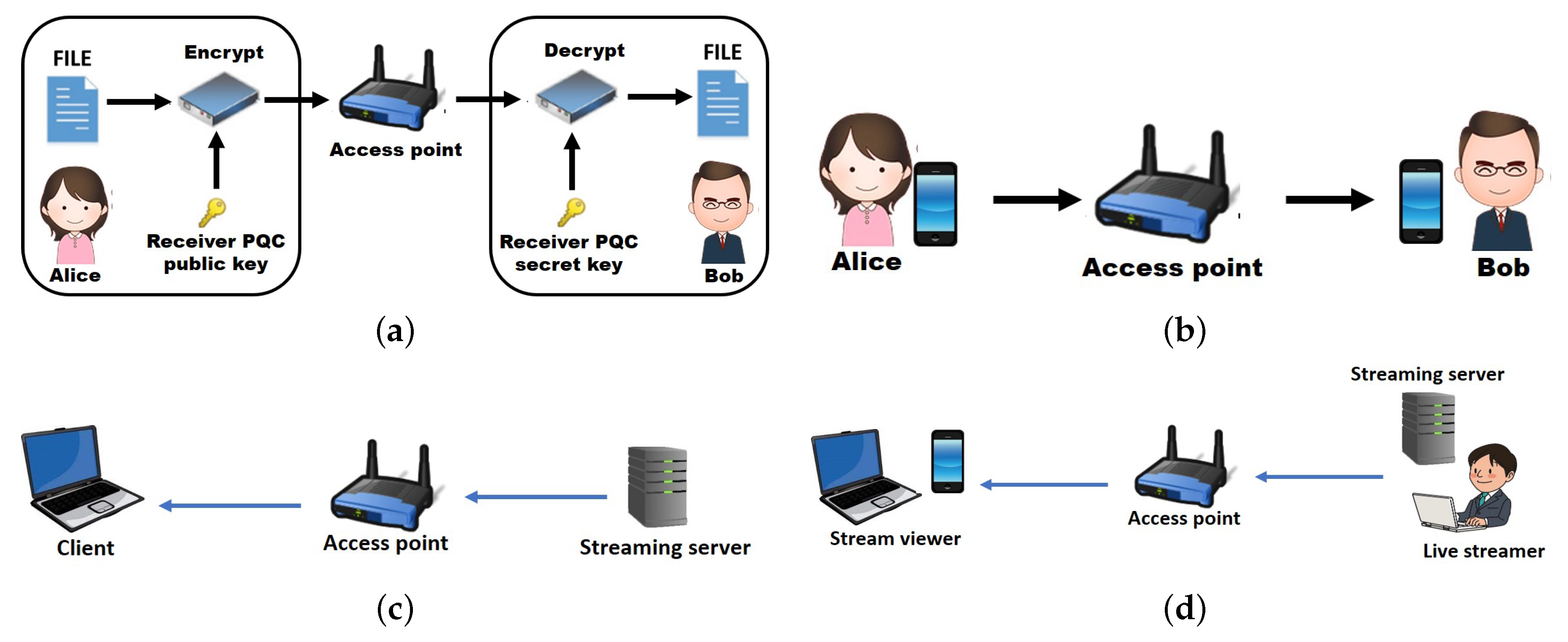

- Bob generates a pair of keys using a PQC algorithm: a public key () and a private key ().

- Bob shares his public key () with Alice while keeping the private key () secret.

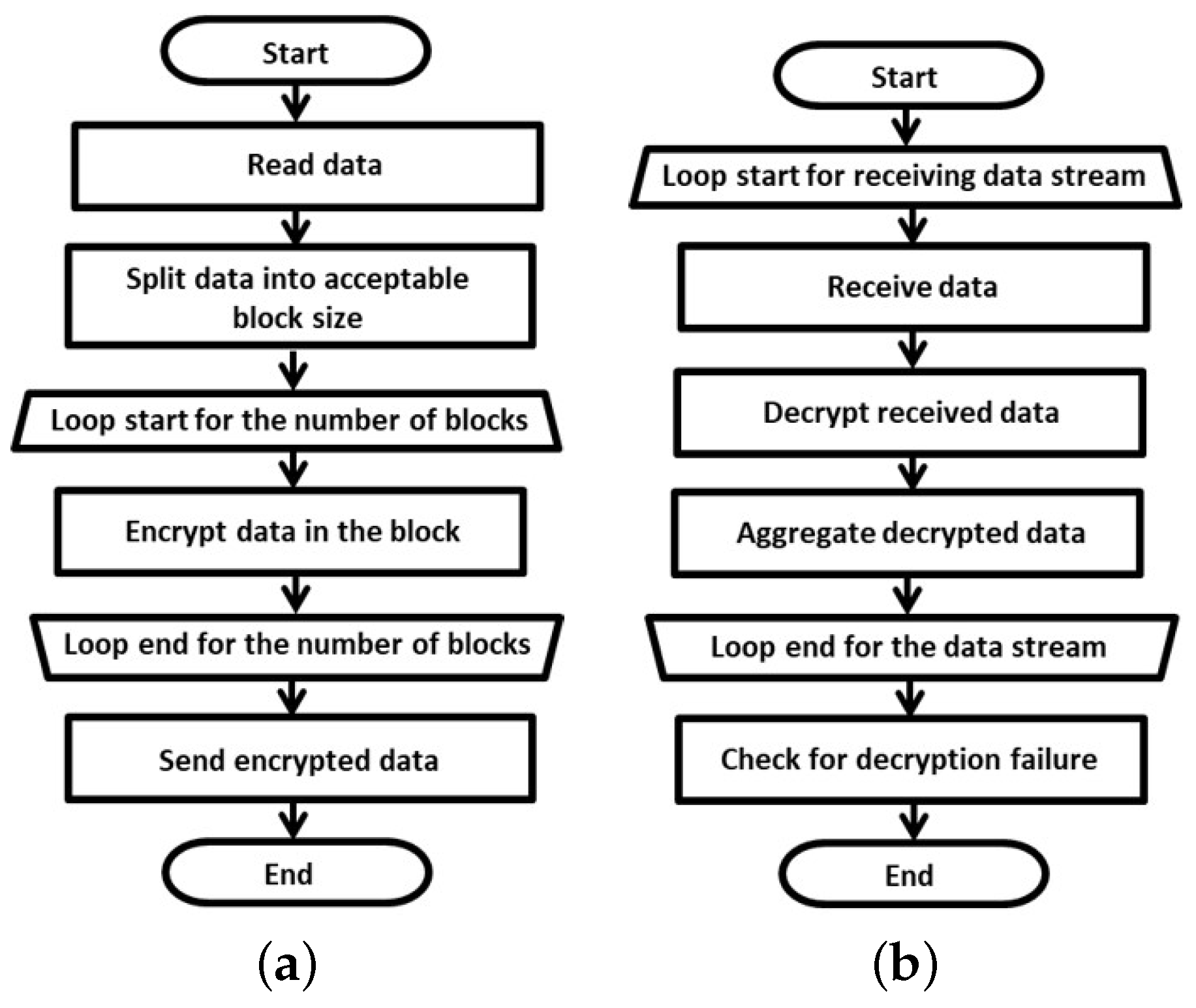

- Alice prepares the data for transmission and splits it into multiple blocks if it exceeds the maximum byte size allowed by the PQC algorithm as shown in Figure 1a.

- Alice encrypts each block sequentially using Bob’s public key (). The encrypted blocks are aggregated into a single encrypted file.

- Alice sends the encrypted file through a secure network.

- The access point routes the encrypted file to Bob without being able to decrypt it.

- Bob receives the encrypted file and uses his private key () to decrypt each block.

- He reassembles the decrypted blocks to reconstruct the original document as shown in Figure 1b.

5. Security Analysis of the Proposed Protocols

5.1. Security Analysis of the PQC Standalone PKE Protocol

5.1.1. Key Exchange (PQC KEM)

Security Assumption

Formal Statement

5.1.2. Key Confirmation

Mechanism

Security Assumption

- The collision resistance of SHA-256.

- The pseudorandomness and unforgeability properties of HMAC.

Formal Statement

5.1.3. Data Encryption and Decryption (PQC)

Security Assumption

Formal Statement

- The underlying KEM is IND-CCA2 secure.

- The public-key encryption scheme derived from it inherits this IND-CCA2 security property.

5.1.4. Replay Protection

Mechanism

- Sequence numbers are incorporated into each encrypted message.

- The receiver tracks these sequence numbers to ensure they are unique and monotonically increasing.

- Messages with duplicate or out-of-order sequence numbers are rejected.

Security Assumption

Formal Statement

5.1.5. Overall Security

Advantages

- Post-Quantum Security: Provides resistance against quantum adversaries due to reliance on PQC algorithms.

- Simplified Design: Avoids additional complexity introduced by hybrid schemes.

Limitations

- Single Point of Failure: The protocol’s security entirely depends on the strength of the PQC algorithms used (both KEM and public-key encryption). If these algorithms are compromised, both key exchange and data confidentiality are at risk.

- Performance Overhead: PQC standalone encryption/decryption operations are computationally intensive compared to symmetric cryptography like AES-256.

Formal Statement

5.2. Security Analysis of the PQC-AES Hybrid PKE Protocol

5.2.1. Security of the Key Exchange (PQC KEM)

5.2.2. Key Confirmation

5.2.3. Security of Data Encryption (AES-256)

Security Assumption

Formal Statement

5.2.4. Overall Security Argument

Formal Statement

5.3. Robustness Against Common Attack Vectors

5.3.1. Eavesdropping

PQC Standalone PKE

PQC-AES Hybrid PKE

5.3.2. Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) Attacks

5.3.3. Replay Attacks

PQC-AES Hybrid PKE (with AES-GCM)

PQC-AES Hybrid PKE (with AES-CBC or Other Modes)

5.3.4. Chosen-Ciphertext Attacks (CCA)

5.3.5. Side-Channel Attacks

5.3.6. Known-Plaintext Attacks

6. Evaluation

6.1. Experiment Settings

6.2. Results and Discussion

6.2.1. PQC Algorithm Key Generation Performance Results

6.2.2. PQC Algorithm Encryption and Decryption Performance Results

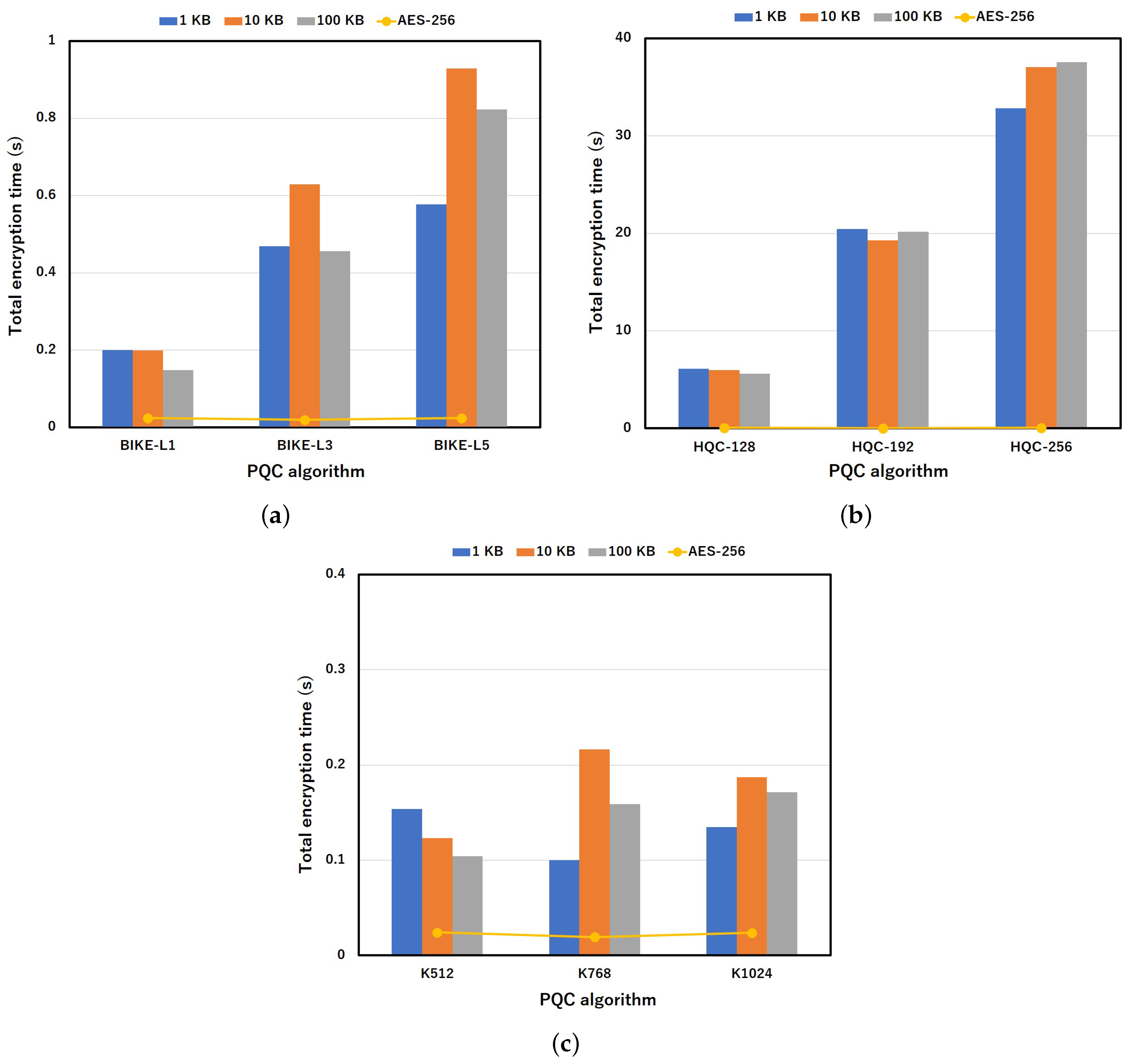

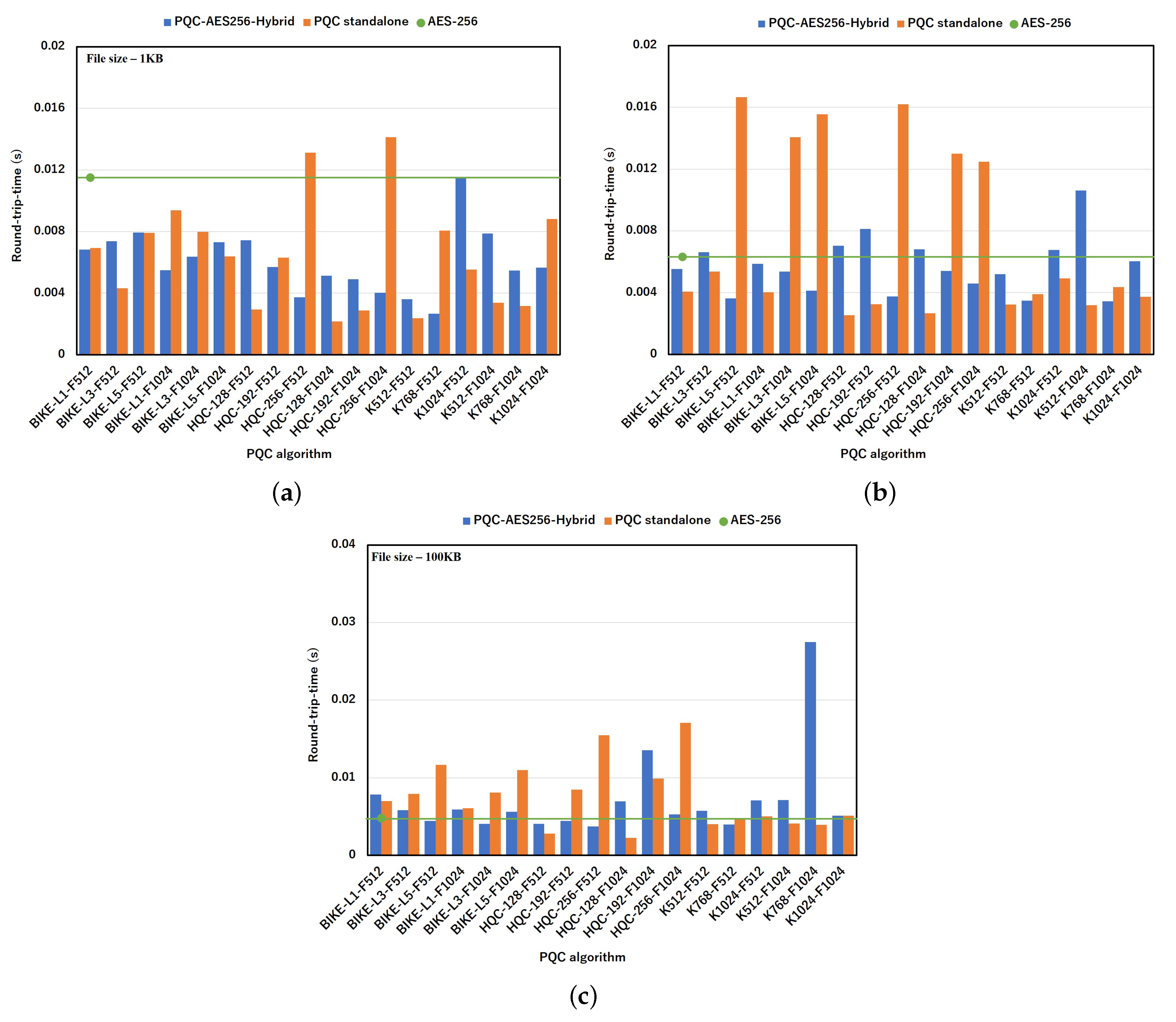

6.2.3. PQC Algorithm Impact on File Transfer Performance Results

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

Abbreviations

| PQC | Post Quantum Cryptography |

| KEM | Key Encapsulation Mechanism |

| PKE | Public Key Encryption |

| AES | Advanced Encryption Standard |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| SSL | Secure Sockets Layer |

| TLS | Transport Layer Security |

| SSH | Secure Shell |

| MITM | Man-in-the-middle |

| MAC | Message Authentication Codes |

| KDF | Key Derivation Function |

| HKDF | Hash-based Message Authentication code Key Derivation Function |

| QC-MDPC | Quasi-Cyclic Moderate Density Parity-Check |

| ACK | Acknowledgement |

References

- Equal1. Bell-1: The First Quantum System Purpose-Built for the HPC Era. [Online]. Available: https://www.equal1.com/post/equal1-launches-bell-1-the-first-quantum-system-purpose-built-for-the-hpc-era. [Accessed: April 16, 2025].

- Esmailiyan, A.; Wang, H.; Asker, M.; Koskin, E.; Leipol, D.; Bashir, I.; Xu, K.; Koziol, A.; Blokhina, E.; Staszewski, R.B. A Fully Integrated DAC for CMOS Position-Based Charge Qubits with Single-Electron Detector Loopback Testing. In IEEE Solid-State Circuits Letters, 3, pp. 354–357, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Staszewski R.B.; Esmailiyan, A.; Wang, H.; Koskin, E.; Giounanlis, P.; Wu, X.; Koziol, A.; Sokolov, A.; Bashir, I.; Asker, M.; Leipol, D.; Nikandish, R.; Siriburanon, T.; Blokhina, E. Cryogenic Controller for Electrostatically Controlled Quantum Dots in 22-nm Quantum SoC. In IEEE Open Journal of the Solid-State Circuits Society, 2, pp. 103–121, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Barker, W.; Polk, W.; Souppaya, M. Getting Ready for Post-Quantum Cryptography: Exploring Challenges Associated with Adopting and Using Post-Quantum Cryptographic Algorithms. (National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST),) NIST Cybersecurity White Paper, April 28, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Jordan, S.; Liu, Y-K.; Moody, D.; Peralta, R.; Perlner, R.; Smith-Tone, D. Report on Post-Quantum Cryptography. (National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)), NIST Internal Report 8105, April 2016. [CrossRef]

- Alagic, G.; Apon, D.; Cooper, D.; Dang, Q.; Dang, T.; Kelsey, J.; Lichtinger, J.; Miller, C.; Moody, D.; Peralta, R.; Perlner, R.; Robinson, A.; Smith-Tone, D.; Liu, Y-K. Status Report on the Third Round of the NIST Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization Process. (National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)), NIST Internal Report 8413-upd1, Sept. 2022. [CrossRef]

- NIST. Special Publication 800-227: Recommendations for key-encapsulation mechanisms, 2024.

- NIST. Module-Lattice-based Key-Encapsulation Mechanism. Federal Information Processing Standards Publication, FIPS 203. August 13, 2024. [CrossRef]

- NIST. Module-Lattice-Based Digital Signature Standard. Federal Information Processing Standards Publication, FIPS 204. August 13, 2024. [CrossRef]

- NIST. Stateless Hash-Based Digital Signature Standard. Federal Information Processing Standards Publication, FIPS 205. August 13, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Alagic, G.; Bros, M.; Ciadoux, P.; Cooper, D.; Dang, Q.; Dang, T.; Kelsey, J.; Lichtinger, J.; Liu, Y.; Miller, C.; Moody, D.; Peralta, R.; Perlner, R.; Robinson, A.; Silberg, H.; Smith-Tone, D.; Waller, N. Status Report on the Fourth Round of the NIST Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization Process. (National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST),) NIST Internal Report (NIST IR 8545), March 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ojetunde, B.; Kurihara, T.; Yano, K.; Sakano, T.; Yokoyama, H. Performance Evaluation of Post-Quantum Cryptography Algorithms for Secure Communication in Wireless Networks. In proceedings IEEE Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC2025), Las Vegas, USA, Jan. 2025.

- Ghosh, S.; Upadhyay, S.; Saki, A.A. A Primer on Security of Quantum Computing. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.02505v1.

- Perepechaenko, M.; Kuang, R. Quantum Encryption and Decryption in IBMQ Systems using Quantum Permutation Pad. Journal of Communications 17, 12, pp. 972–978, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Schwabe, P.; Stebila, D.; Wiggers, T. Post-Quantum TLS Without Handshake Signatures. In Proceedings of he 2020 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 1461–1480, Oct. 2020, New York, USA. [CrossRef]

- Schwabe, P.; Stebila, D.; Wiggers, T. More Efficient Post-quantum KEMTLS with Pre-distributed Public Keys. In: Bertino, E., Shulman, H., Waidner, M. (eds) Computer Security – ESORICS 2021. ESORICS 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 12972, Sept. 30 2021, Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Gunther, F.; Rastikian, S.; Towa, P.; Wiggers, T. KEMTLS with Delayed Forward Identity Protection in (Almost) a Single Round Trip. In: Ateniese, G., Venturi, D. (eds) Applied Cryptography and Network Security. ACNS 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 13269. June 18 2022, Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Sarma, B.K.; Saikia, A. Public key cryptography using Permutation P-Polynomials over Finite Fields. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2009/208, 2009. https://eprint.iacr.org/2009/208.pdf.

- Marco, L.; Talayhan, A.; Vaudenay, S. Making Classical (Threshold) Signatures Post-Quantum for Single Use on a Public Ledger. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2023/420, 2023. https://eprint.iacr.org/2023/420.

- da Silva Lima, P.; Ribeiro, L.A.; Queiroz, R.J.; Quintino, J.P.; Silva, F.Q.; Santos, A.L.; Roberto, J. Evaluating Kyber post-quantum KEM in a mobile application. 2021. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:237235623.

- Giron, A.A. Migrating Applications to Post-Quantum Cryptography: Beyond Algorithm Replacement. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2023/709, 2023. https://eprint.iacr.org/2023/709.

- Liu, T.; Ramachandran, G.; Jurdak, R. Post-Quantum Cryptography for Internet of Things: A Survey on Performance and Optimization. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Asif, R. Post-Quantum Cryptosystems for Internet-of-Things: A Survey on Lattice-Based Algorithms. Algorithms. IoT 2021, 2, pp. 71-–91. http://. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yuxiang, C.; Lin, C.; Jing, L.; Chanchan, K.; Kuanching, L.; Wei, L.; Naixue, X. Post-Quantum Security: Opportunities and Challenges. Sensors 23, 21: 8744, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, C.; Singh, K.; Ganesan, G.; Rajarajan, M. Post-Quantum and Code-Based Cryptography—Some Prospective Research Directions. Cryptography, 4: 38, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Fakhruldeen, H.F.; Al-Kaabi, R.A.; Jabbar, F.I.; Al-Kharsan, I.H.; Shoja, S.J. Post-quantum Techniques in Wireless Network Security: An Overview. Malaysian Journal of Fundamental and Applied Sciences, Vol. 19 2023 pp. 337–344. [CrossRef]

- Lawo, D.C.; Abu Bakar, R.; Cano Aguilera, A.; Cugini, F.; Imaña, J.L.; Tafur Monroy, I.; Vegas Olmos, J.J. Wireless and Fiber-Based Post Quantum-Cryptography-Secured IPsec Tunnel. Future Internet 2024, 16, 300. [CrossRef]

- https://www.nist.gov/news-events/news/2022/07/pqc-standardization-process-announcing-four-candidates-be-standardized-plus.

- Liboqs, https://openquantumsafe.org/liboqs/.

- Sharpe, R.; Warnicke, E.; Lamping, U. Wireshark User’s Guide. Version 4.1.0. https://www.wireshark.org/docs/wsug_html_chunked/.

| (a) | (b) |

| (a) | (b) |

| (c) | (d) |

| (a) | (b) |

| (c) | |

| (a) | (b) |

| (c) | |

| (a) | (b) |

| (a) | (b) |

| (c) | |

| (a) | (b) |

| (c) | |

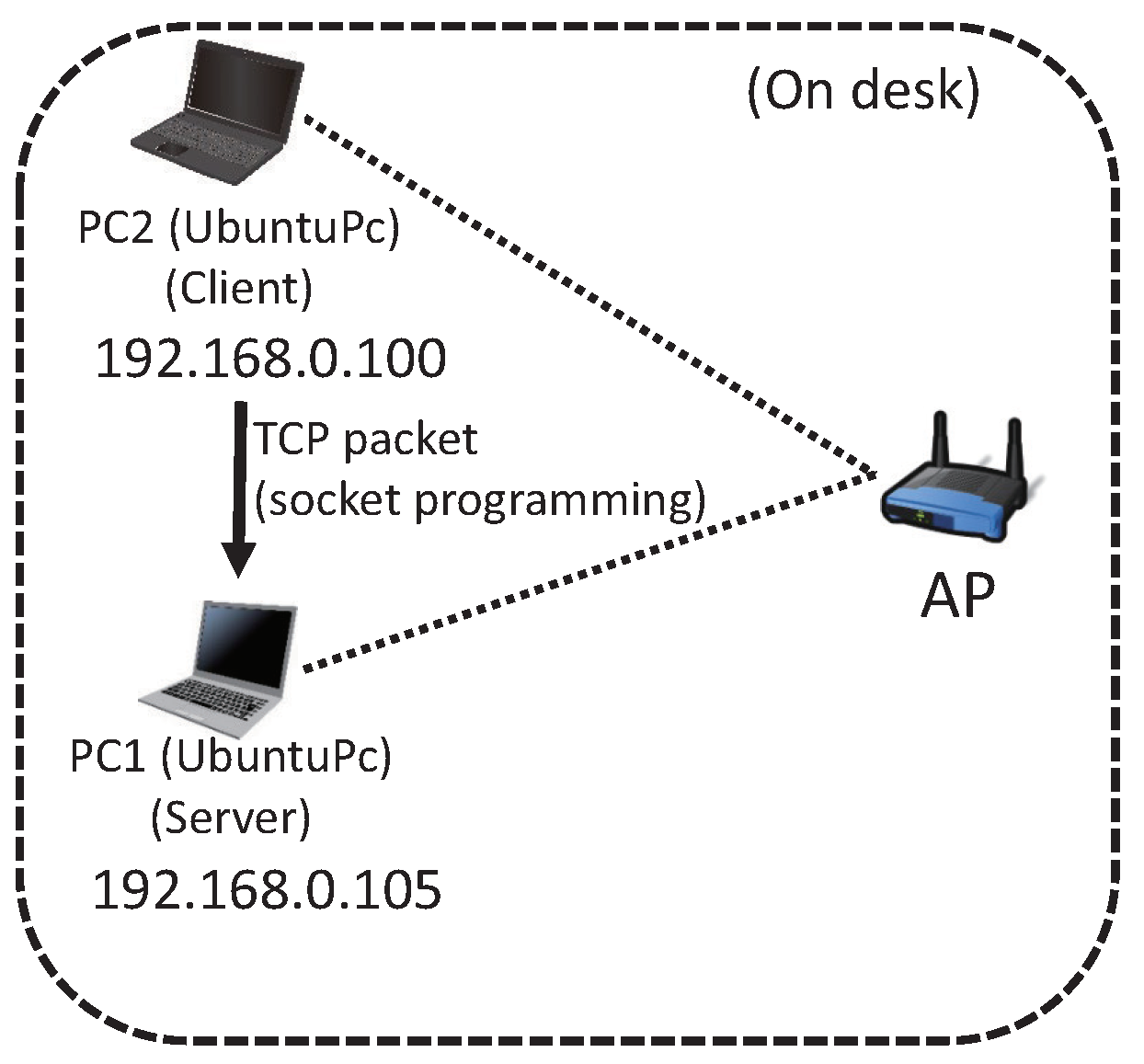

| Parameter | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Server | Client | |

| PC | Mouse Laptop | Mouse Laptop |

| OS | Ubuntu 20.04 desktop | Ubuntu 20.04 desktop |

| Network/Protocol | IEEE 802.11n | IEEE 802.11n |

| Frequency band | 2.4 GHz | 2.4 GHz |

| Maximum data rate | 144 Mbps | 144 Mbps |

| Sniffer | Wireshark | Wireshark |

| PQC KEM Algorithm |

Client | Server | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ave. Key Gen. (ms) |

Ave. Encap. (ms) |

Ave. Decap. (ms) |

Ave. Key Gen. (ms) |

Ave. Encap. (ms) |

Ave. Decap. (ms) |

|

| BIKE-L1 | 0.43 | 0.12 | 1.64 | 1.23 | 0.12 | 1.52 |

| BIKE-L3 | 0.80 | 0.21 | 5.68 | 2.63 | 0.19 | 5.79 |

| BIKE-L5 | 1.95 | 0.36 | 14.42 | 5.05 | 0.33 | 15.94 |

| HQC-128 | 3.45 | 5.76 | 10.23 | 5.60 | 4.03 | 8.44 |

| HQC-192 | 4.88 | 12.83 | 28.11 | 9.70 | 11.99 | 32.20 |

| HQC-256 | 8.73 | 17.96 | 49.77 | 14.32 | 1.81 | 53.40 |

| K512 | 0.92 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 1.83 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| K768 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| K1024 | 1.00 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.49 | 0.09 | 0.11 |

| PQC Signature |

Client | Server | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ave. Sig. Key Gen. (ms) |

Ave. Signing (ms) |

Ave. Ver. (ms) |

Ave. Sig. Key Gen. (ms) |

Ave. Signing (ms) |

Ave. Ver. (ms) |

|

| F512 | 7.01 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 9.68 | 0.37 | 0.82 |

| F1024 | 19.00 | 1.43 | 0.31 | 24.51 | 0.67 | 0.79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).