Submitted:

06 September 2024

Posted:

09 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Leaf Area Index (LAI)

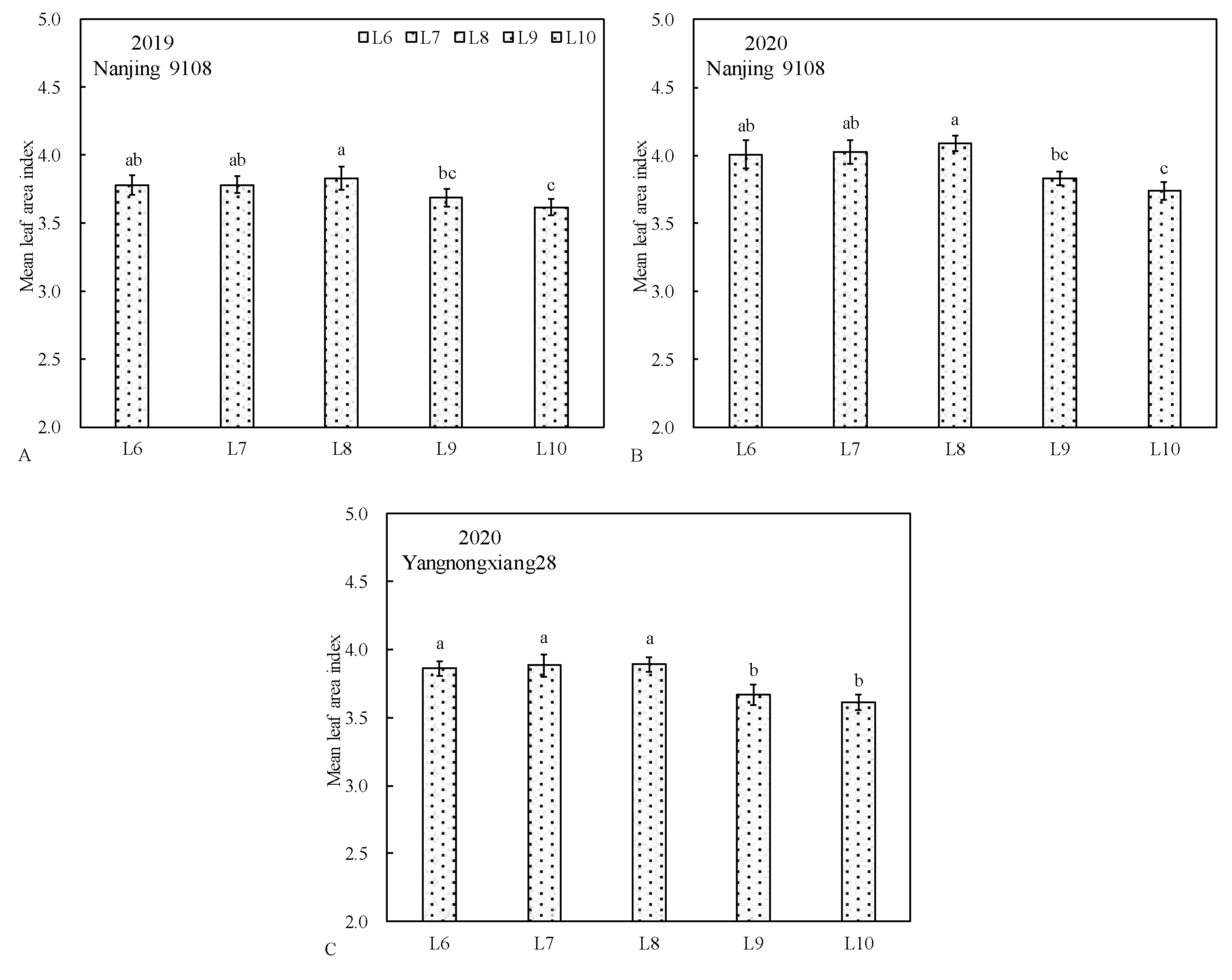

2.2. Mean Leaf Area Index (MLAI)

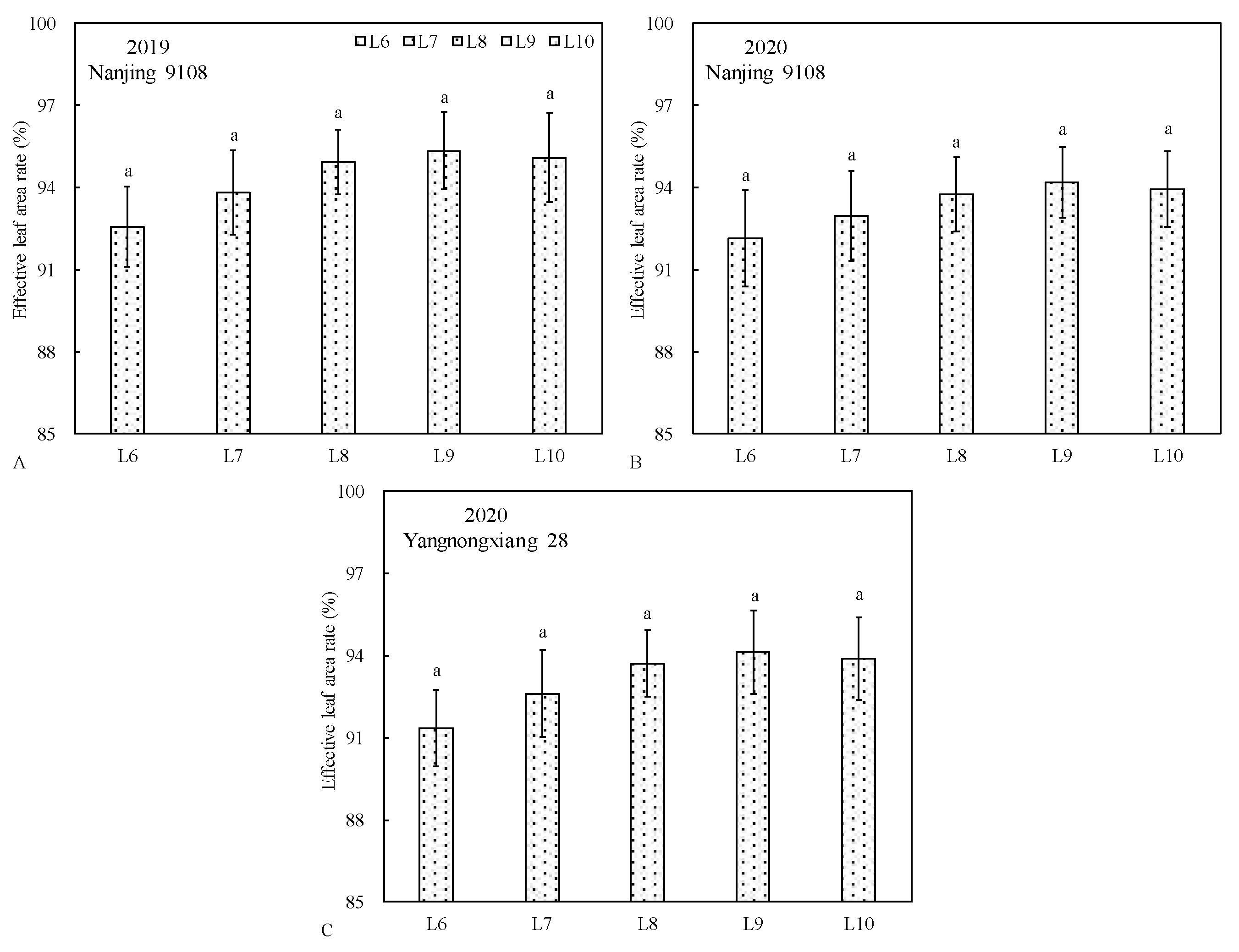

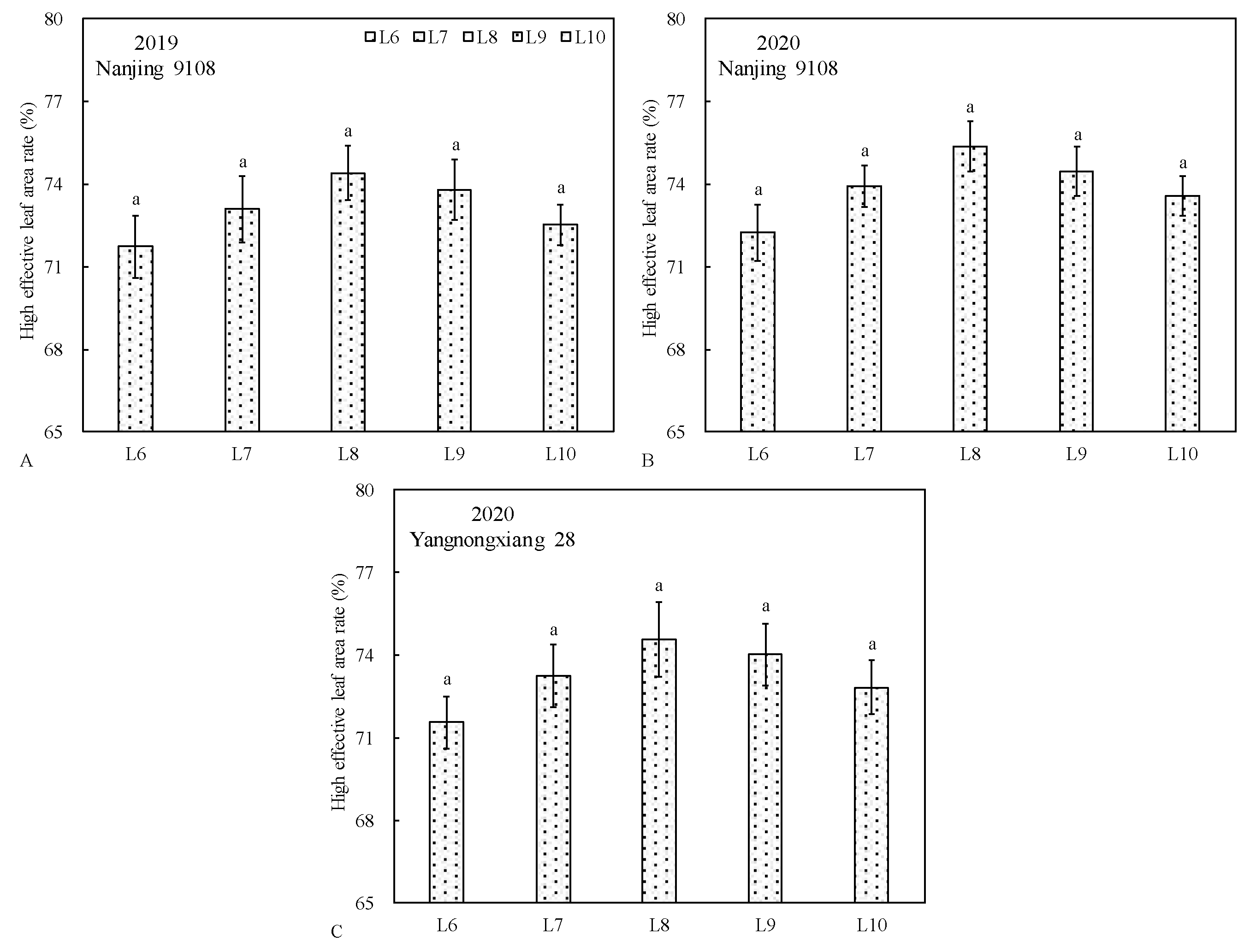

2.3. Effective Leaf Area Rate (ELAR) and High Effective Leaf Area Rate (HELR) at Heading Stage

2.4. Leaf Area Duration (LAD)

2.5. Above-Ground Dry Matter Weight (ADW) at Mian Growth Stage

2.6. Above-Ground Dry Matter Weight (ADW) in Determined Growth Period

2.7. Crop Growth Rate (CGR) and Net Assimilation Rate (NAR)

2.8. Grain-Leaf Ratio Traits

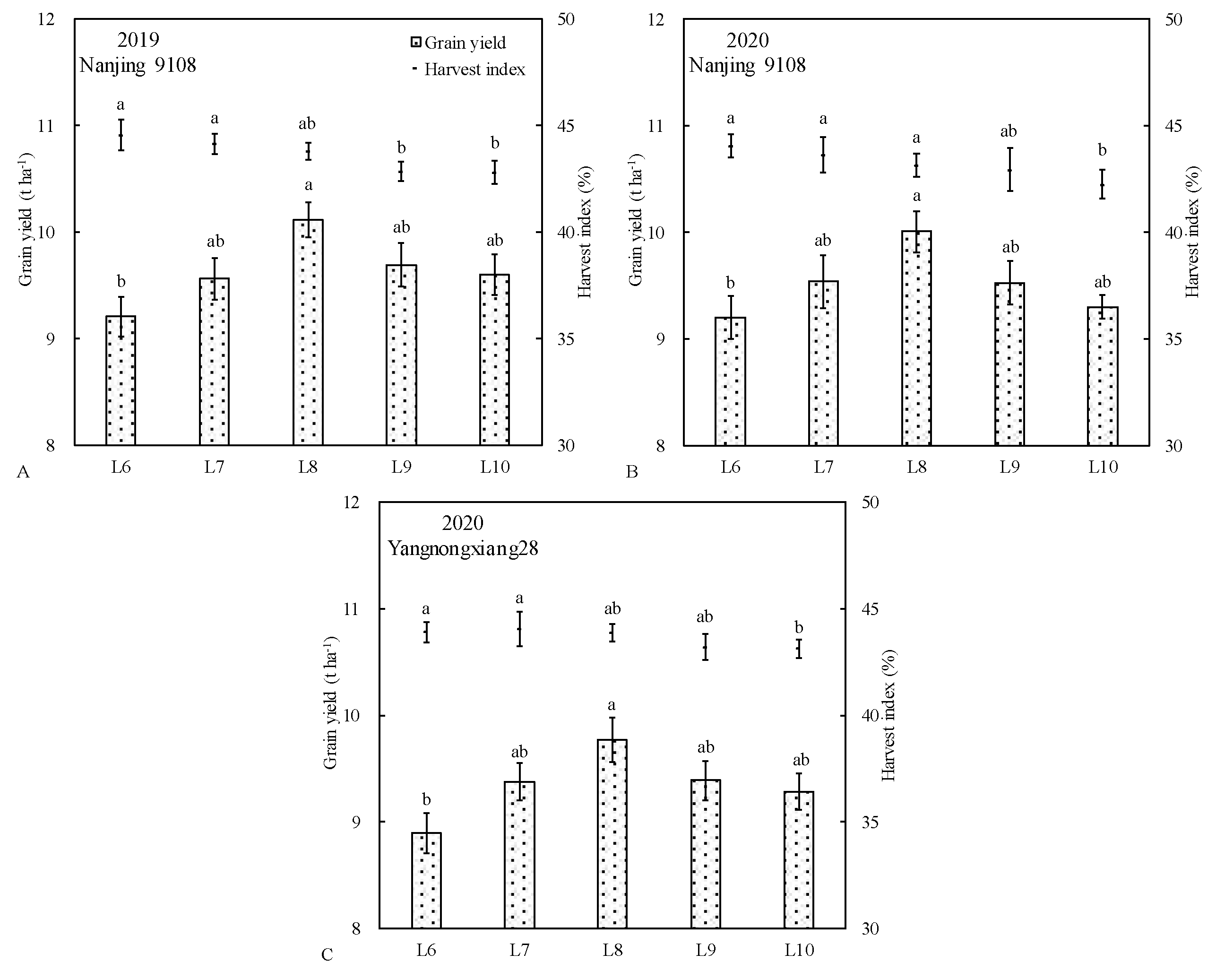

2.9. Grain Yield and Harvest Index

3. Discussion

3.1. The Above-Ground Dry Matter Accumulation Trait

3.2. The Above-Ground Dry Matter Production Trait

4. Materials and Methods

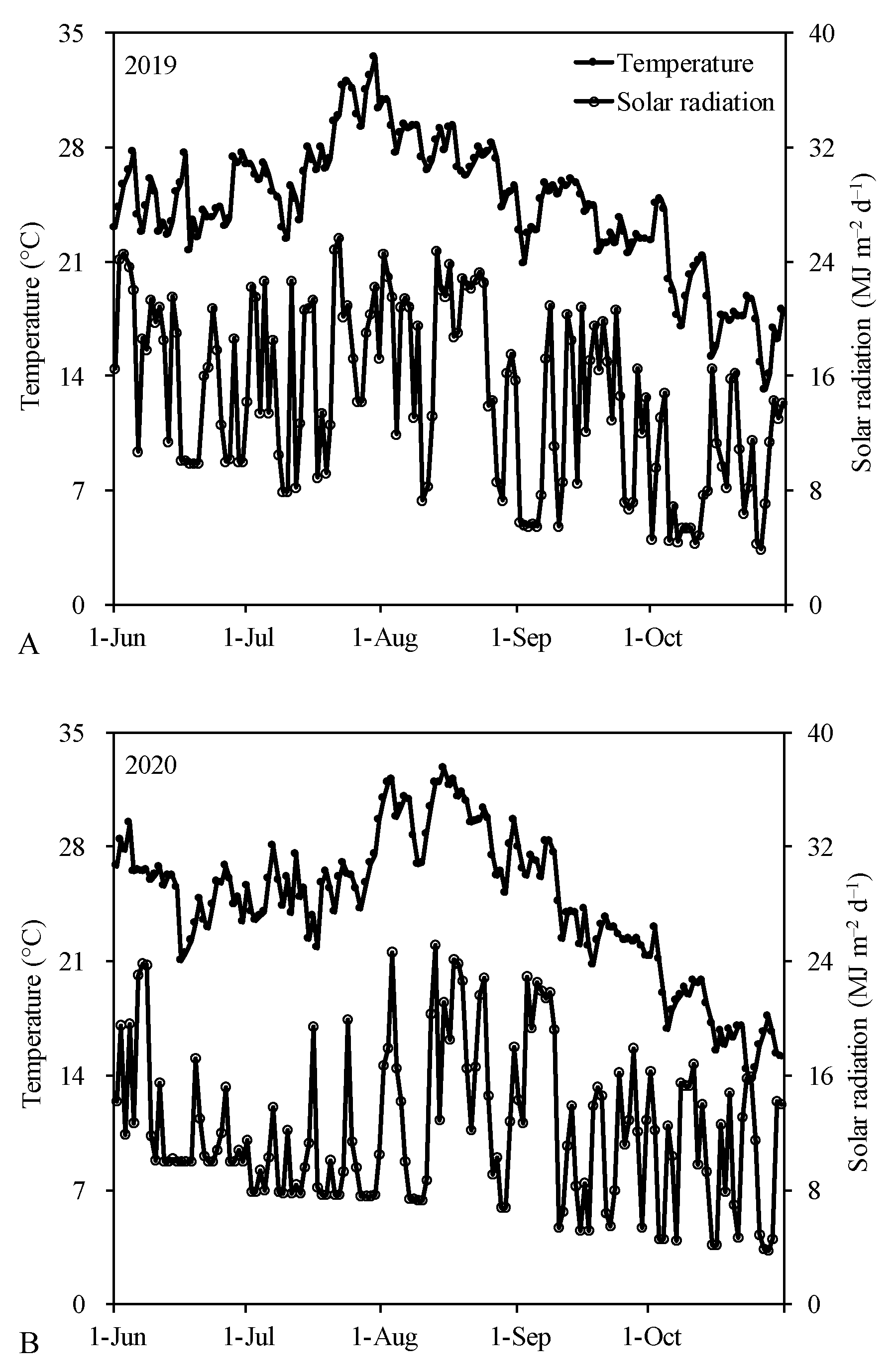

4.1. Experiment Condition and Plant Material

4.2. Experiment Design and Cultivation

4.3. Sampling and Measurements

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Farooq, M.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Rehman, H.; Aziz, T.; Lee, D.J.; Wahid, A. Rice direct seeding: experiences, challenges and opportunities. Soil Tillage Res. 2011, 111, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Hussain, S.; Zheng, M.M.; Peng, S.B.; Huang, J.L.; Cui, K.H.; Nie, L.X. Dry direct-seeded rice as an alternative to transplanted-flooded rice in central China. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M; Li, X. B.; Xin, L.J.; Tan, M.H. Paddy rice multiple cropping index changes in southern China: impacts on national grain production capacity and policy implications. J. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 1773–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.C.; Xing, Z.P.; Weng, W.A.; Tian, J.Y.; Tao, Y.; Cheng, S.; Hu, Q.; Hu, Y.J.; Guo, B.W.; Wei, H.Y. Growth characteristics and key techniques for stable yield of growth constrained direct seeding rice. Sci. Agric. Sin. 1322. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Z.P.; Huang, Z.C.; Yao, Y.; Hu, Y.J.; Guo, B.W.; Zhang, H.C. Comparison of crop yield and solar thermal utilization among different rice–wheat cropping systems. J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 161, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap, V.; Dass, A.; Dhar, S.; Babu, S.; Singh, V.K.; Singh, R.; Krishnan, P.; Sudhishri, S.; Bhatia, A.; Kumar, S.; et al. Co-implementation of tillage, precision nitrogen, and water management enhances water productivity, economic returns, and energy-use efficiency of direct-seeded rice. Sustainability. 2022, 14, 11234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.Y.; Li, S.P.; Cheng, S.; Liu, Q.Y.; Zhou, L.; Tao, Y.; Xing, Z.P.; Hu, Y.J.; Guo, B.W.; Wei, H.Y.; et al. Increasing the appropriate seedling density for higher yield in dry direct-seeded rice sown by a multifunctional seeder after wheat-straw return. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.M.; Yu, K.R.; Zou, J.X.; Bao, X.Z.; Yang, T.T.; Chen, Q.C.; Zhang, B. Management of seeding rate and nitrogen fertilization for lodging risk reduction and high grain yield of mechanically direct-seeded rice under a double-cropping regime in south China. Agronomy-Basel. 2024, 14, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, C.S.; Carandang, R.B.; Motilla, J.K.L.; Cruz, P.C.S. Yield component compensation as affected by seeding rates in dry direct seeded rice. Philipp. Agric. Sci. 2023, 106, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.Q.; Huang, N.R.; Zhong, X.H.; Mai, G.X.; Pan, H.R.; Xu, H.Q.; Liu, Y.Z.; Liang, K.M.; Pan, J.F.; Xiao, J.; et al. Improving grain yield and nitrogen use efficiency of direct-seeded rice with simplified and nitrogen-reduced practices under a double-cropping system in south China. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 5727–5737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, X.L.; Zhang, Z.L.; Lin, Y.Y.; Wang, B.F.; Zhang, Z.S.; Liu, C.Y.; Cheng, J.P. Delaying first fertilization time improved yield and N utilization efficiency on direct seeding rice. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Zhang, K.Y.; Liao, X.H.; Aer, L.S.; Yang, E.L.; Deng, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, R.P. Effects of nitrogen application rate on dry matter weight and yield of direct-seeded rice under straw return. Agronomy-Basel. 2023, 13, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, S.P.; Cheng, S.; Tian, J.Y.; Xing, Z.P.; Tao, Y.; Zhou, L.; Liu, Q.Y.; Hu, Y.J.; Guo, B.W.; et al. Effects of nitrogen fertilizer in whole growth duration applied in the middle and late tillering stage on yield and quality of dry direct seeding rice under ‘solo-stalk’ cultivation mode. Acta Agron. Sin. 1162. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.B.; Shan, S.L.; Wang, Y.M.; Cao, F.B.; Chen, J.N.; Huang, M.; Zou, Y.B. Dense planting with reducing nitrogen rate increased grain yield and nitrogen use efficiency in two hybrid rice varieties across two light conditions. Field Crop. Res. 2019, 236, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Zeng, Y.J.; Wu, Z.M.; Guo, L.; Xie, X.B.; Shi, Q.H.; Pan, X.H. Nutrient utilization and double cropping rice yield response to dense planting with a decreased nitrogen rate in two different ecological regions of south China. Agriculture-Basel. 2022, 12, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.Q.; Zhong, X.H.; Zeng, J.H.; Liang, K.M.; Pan, J.F.; Xin, Y.F.; Liu, Y.Z.; Hu, X.Y.; Peng, B.L.; Chen, R.B.; et al. Improving grain yield, nitrogen use efficiency and radiation use efficiency by dense planting, with delayed and reduced nitrogen application, in double cropping rice in south China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, X.C.; Xie, J.; Deng, G.Q.; Tu, T.H.; Guan, X.J.; Yang, Z.; Huang, S.; Chen, X.M.; Qiu, C.F.; et al. Reducing nitrogen application with dense planting increases nitrogen use efficiency by maintaining root growth in a double-rice cropping system. Crop J. 2021, 9, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.P.; Deng, A.X.; Zhang, W.J. Dense planting with less basal nitrogen fertilization might benefit rice cropping for high yield with less environmental impacts. Eur. J. Agron. 2016, 75, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Li, Y.M.; Zhang, K.H.; Wu, Z.Z.; Liu, J.X.; Liu, J.F.; Zhou, C.C.; Wang, S.; Li, F.H.; Sui, G.M. Selection and yield formation characteristics of dry direct seeding rice in northeast China. Plants-Basel. 2023, 12, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, J.F.; Peng, S.B.; He, Q.R.; Yang, H.; Yang, C.D.; Visperas, R.M.; Cassman, K.G. Comparison of high-yield rice in tropical and subtropical environments: I. determinants of grain and dry matter yields. Field Crop. Res. 1998, 57(1), 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsura, K.; Maeda, S.; Lubis, I.; Horie, T.; Cao, W.X.; Shiraiwa, T. The high yield of irrigated rice in Yunnan, China- ‘A cross-location analysis’. Field Crop. Res. 2008, 107, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Gao, H.; Yoshihiro, H.; Koki, H.; Tetsuya, N.; Liu, T.S.; Tatsuhiko, S.; Xu, Z.J. Erect panicle super rice varieties enhance yield by harvest index advantages in high nitrogen and density conditions. J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 1467–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.B.; Tang, Q.Y.; Zou, Y.B. Current status and challenges of rice production in China. Plant. Prod. Sci. 2009, 12, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Peng, S.B. Yield potential and nitrogen use efficiency of China’s super rice. J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.W.; Bin, S.Y.; Iqbal, A.; He, L.J.; Wei, S.Q.; Zheng, H.; Yuan, P.L.; Liang, H.; Ali, I.; Xie, D.J.; et al. High sink capacity improves rice grain yield by promoting nitrogen and dry matter accumulation. Agronomy-Basel. 2022, 12, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.B.; Chen, Y.W.; Chen, Q.M.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y.S.; Jia, W.; Mo, W.W.; Tang, Q.Y. High-density planting with lower nitrogen application increased early rice production in a double-season rice system. Agron. J. 2020, 112, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.B.; Hu, C.; Xu, H.C.; Yang, R.; You, C.C.; Ke, J.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Wu, L.Q. High yield, good eating quality, and high N use efficiency for medium hybrid indica rice: from the perspective of balanced source-sink relationships at heading. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 159, 127281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.X.; Huang, J.L.; Cui, K.H.; Nie, L.X.; Xiang, J.; Liu, X.J.; Wu, W.; Chen, M.X.; Peng, S.B. Agronomic performance of high-yielding rice variety grown under alternate wetting and drying irrigation. Field Crop. Res. 2012, 126, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.W.; Liu, L.J.; Wang, Z.Q.; Yang, J.C.; Zhang, J.H. Agronomic and physiological performance of high-yielding wheat and rice in the lower reaches of Yangtze River of China. Field Crop. Res. 2012, 133, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Peng, J.; Wang, J.; Fu, P.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, C.; Fahad, S.; Peng, S.; Cui, K.; Nie, L.; et al. Crop management based on multi-split topdressing enhances grain yield and nitrogen use efficiency in irrigated rice in China. Field Crop. Res. 2015, 184, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Li, C.; Yao, L.; Cui, H.Y.; Tian, Y.J.; Sun, X.; Yu, T.H.; He, J.Q.; Wang, S. Effects of dynamic nitrogen application on rice yield and quality under straw returning conditions. Environ. Res. 2024, 243, 117857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y; Zhang, Y. C.; Cui, J.H.; Gao, J.C.; Guo, L.Y.; Zhang, Q. Nitrogen fertilization application strategies improve yield of the rice cultivars with different yield types by regulating phytohormones. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 21803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Yang, X.; Tan, X.L.; Han, K.F.; Tang, S.; Tong, W.M.; Zhu, S.Y.; Hu, Z.P.; Wu, L.H. Comparison of agronomic performance between japonica/indica hybrid and japonica cultivars of rice based on different nitrogen rates. Agronomy-Basel. 2020, 10, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Nie, L.X.; Wang, F.; Huang, J.L.; Peng, S.B. Agronomic performance of inbred and hybrid rice cultivars under simplified and reduced-input practices. Field Crop. Res. 2017, 210, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.C.; Yuan, X.J.; Wen, Y.F.; Yang, Y.G.; Ma, Y.M.; Yan, F.J.; Li, B.; Wang, Z.L.; Xing, M.W.; Zhang, R.P.; et al. Common population characteristics of direct-seeded hybrid indica rice for high yield. Agron. J. 2023, 115, 1606–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Xing, Z.P.; Tian, C.; Weng, W.A.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, H.C. Optimization of one-time fertilization scheme achieved the balance of yield, quality and economic benefits of direct-seeded rice. Plants-Basel. 2023, 12, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.Y.; Li, S.P.; Xing, Z.P.; Cheng, S.; Guo, B.W.; Hu, Y.J.; Wei, H.Y.; Gao, H.; Liao, P.; Wei, H.H.; et al. Differences in rice yield and biomass accumulation dynamics for different direct seeding methods after wheat straw return. Food Energy Secur. 2022, 11, e425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.H.; Cao, Y.W.; Chai, Y.X.; Meng, X.S.; Wang, M.; Wang, G.J.; Guo, S.W. Identification of photosynthetic parameters for superior yield of two super hybrid rice varieties: a cross-scale study from leaf to canopy. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1110257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.W.; Ma, T.; Ding, J.H.; Yu, S.E.; Dai, Y.; He, P.R.; Ma, T. Effects of straw return with nitrogen fertilizer reduction on rice (Oryza sativa L.) morphology, photosynthetic capacity, yield and water-nitrogen use efficiency traits under different water regimes. Agronomy-Basel. 2023, 13, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horie, T.; Ohnishi, M.; Angus, J. F.; Lewin, L.G; Tsukaguchi, T.; Matano, T. Physiological characteristics of high-yielding rice inferred from cross-location experiments. Field Crop. Res. 1997, 52, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.X.; Zhou, Y.J.; Shuai, P.; Wang, X.Y.; Peng, S.B.; Wang, F. Source-sink balance optimization depends on soil nitrogen condition so as to increase rice yield and N use efficiency. Agronomy-Basel.

- Wang, J.J.; Xie, R.Q.; He, N.A.; Wang, W.L.; Wang, G.L.; Yang, Y.J.; Hu, Q.; Zhao, H.T.; Qian, X.Q. Five years nitrogen reduction management shifted soil bacterial community structure and function in high-yielding 'super' rice cultivation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 360, 108773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirooka, Y.; Homma, K.; Shiraiwa, T.; Kuwada, M. Parameterization of leaf growth in rice (Oryza sativa L.) utilizing a plant canopy analyzer. Field Crop. Res. 2016, 186, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year/Cultivar | Treatment | Tenth-leaf stage |

Jointing stage |

Booting stage |

Heading stage |

Maturity stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | ||||||

|

Nanjing 9108 |

L6 | 2.84a | 4.18a | 7.39b | 6.82b | 3.02c |

| L7 | 2.48b | 4.08a | 7.63ab | 7.13ab | 3.17bc | |

| L8 | 2.28b | 3.87a | 7.95a | 7.54a | 3.46b | |

| L9 | 1.76c | 3.44b | 7.82ab | 7.46a | 3.92a | |

| L10 | 1.75c | 3.29b | 7.79ab | 7.31a | 4.08a | |

| 2020 | ||||||

|

Nanjing 9108 |

L6 | 2.89a | 4.39a | 7.52b | 6.84b | 3.20c |

| L7 | 2.49ab | 4.22ab | 7.73ab | 7.32ab | 3.33bc | |

| L8 | 2.29b | 3.97abc | 8.07a | 7.67a | 3.64ab | |

| L9 | 1.69c | 3.63bc | 7.96ab | 7.56a | 3.79a | |

| L10 | 1.67c | 3.42c | 7.89ab | 7.30ab | 3.86a | |

|

Yangnong xiang 28 |

L6 | 2.80a | 4.17a | 7.58b | 7.04b | 3.44b |

| L7 | 2.34b | 4.08a | 7.71ab | 7.44ab | 3.63ab | |

| L8 | 2.21b | 3.92ab | 8.02a | 7.65a | 3.78ab | |

| L9 | 1.69c | 3.71b | 7.95ab | 7.55ab | 3.86ab | |

| L10 | 1.68c | 3.58b | 7.91ab | 7.39a | 3.92a |

| Year/Cultivar | Treatment | Before jointing stage (m2 m–2 d–1) |

Jointing to heading stage (m2 m–2 d–1) |

Heading to maturity stage (m2 m–2 d–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | ||||

|

Nanjing 9108 |

L6 | 110.77a | 159.48ab | 236.13b |

| L7 | 108.15a | 162.52a | 247.06b | |

| L8 | 106.54a | 165.57a | 264.10b | |

| L9 | 94.47b | 158.02ab | 273.11a | |

| L10 | 93.72b | 153.64b | 273.21a | |

| 2020 | ||||

|

Nanjing 9108 |

L6 | 118.43a | 168.42ab | 251.00b |

| L7 | 115.92a | 172.98ab | 266.18b | |

| L8 | 109.22ab | 174.63a | 282.77a | |

| L9 | 103.32ab | 167.73ab | 283.64a | |

| L10 | 97.45b | 160.83b | 278.96a | |

|

Yangnong xiang28 |

L6 | 120.83a | 151.36b | 262.10b |

| L7 | 118.35ab | 161.35a | 276.92ab | |

| L8 | 117.54ab | 161.92a | 285.61a | |

| L9 | 114.86ab | 157.52ab | 285.14a | |

| L10 | 110.85b | 153.57ab | 282.89a |

| Year/Cultivar | Treatment | Tenth-leaf stage (t ha-1) |

Jointing stage (t ha-1) |

Heading stage (t ha-1) |

Milky stage (t ha-1) |

Maturity stage (t ha-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | ||||||

|

Nanjing 9108 |

L6 | 2.17a | 4.53a | 11.10abc | 14.02c | 17.67b |

| L7 | 1.99ab | 4.47a | 11.52ab | 15.36b | 18.53ab | |

| L8 | 1.83bc | 4.38ab | 11.96a | 16.54a | 19.75a | |

| L9 | 1.74c | 3.84bc | 10.67bc | 15.76ab | 19.35a | |

| L10 | 1.74c | 3.71c | 10.28c | 15.54b | 19.19a | |

| 2020 | ||||||

|

Nanjing 9108 |

L6 | 2.19a | 5.03a | 11.23abc | 14.95c | 17.86b |

| L7 | 2.01b | 5.00a | 11.54ab | 15.56bc | 18.69ab | |

| L8 | 1.80c | 4.47a | 12.13a | 17.02a | 19.83a | |

| L9 | 1.71c | 3.70b | 10.83bc | 15.97b | 18.98ab | |

| L10 | 1.71c | 3.59b | 10.38c | 15.62bc | 18.83ab | |

|

Yangnong xiang28 |

L6 | 2.11a | 4.75a | 10.92bc | 14.48b | 17.34b |

| L7 | 1.91b | 4.68a | 11.24ab | 14.97b | 18.22ab | |

| L8 | 1.79bc | 4.17ab | 11.71a | 16.54a | 19.05a | |

| L9 | 1.69c | 3.73b | 10.72bc | 15.23b | 18.58a | |

| L10 | 1.69c | 3.57b | 10.26c | 14.98b | 18.41ab |

| Year/ Cultivar |

Treatment | RAPT before jointing stage (%) | Jointing to heading stage | Heading to maturity stage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADW (t ha-1) | RCPT (%) | ADW (t ha-1) | RAPT (%) | |||

| 2019 | ||||||

|

Nanjing 9108 |

L6 | 25.6a | 6.58c | 37.2b | 6.57c | 37.2d |

| L7 | 24.1a | 7.05b | 38.1ab | 7.01c | 37.8d | |

| L8 | 22.2b | 7.58a | 38.4a | 7.79b | 39.4c | |

| L9 | 19.8c | 6.84bc | 35.4c | 8.67a | 44.8b | |

| L10 | 19.3c | 6.57c | 34.2d | 8.91a | 46.4a | |

| 2020 | ||||||

|

Nanjing 9108 |

L6 | 28.2a | 6.20c | 34.7b | 6.63d | 37.1b |

| L7 | 26.7a | 6.54bc | 35.0b | 7.14cd | 38.2b | |

| L8 | 22.5b | 7.66a | 38.6a | 7.71bc | 38.9b | |

| L9 | 19.5c | 7.13ab | 37.7ab | 8.14ab | 42.9a | |

| L10 | 19.1c | 6.78bc | 36.0ab | 8.45a | 44.9a | |

|

Yangnong xiang28 |

L6 | 27.4a | 6.17c | 35.6b | 6.42d | 37.0b |

| L7 | 25.7a | 6.55bc | 36.0b | 6.98cd | 38.3b | |

| L8 | 21.9b | 7.54a | 39.5a | 7.34bc | 38.5b | |

| L9 | 20.1b | 6.99ab | 37.6ab | 7.86ab | 42.3a | |

| L10 | 19.4b | 6.69bc | 36.3b | 8.15a | 44.3a | |

| Year/ Cultivar |

Treatment | Before jointing stage (g m–2 d–1) |

Jointing to heading stage (g m–2 d–1) |

Heading to maturity stage (g m–2 d–1) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGR | NAR | CGR | NAR | CGR | NAR | ||

| 2019 | |||||||

|

Nanjing 9108 |

L6 | 8.54a | 2.92a | 22.67c | 4.21c | 13.69c | 2.94c |

| L7 | 8.43a | 2.90a | 24.32b | 4.45b | 14.60c | 2.99c | |

| L8 | 7.96ab | 2.78ab | 26.14a | 4.75a | 16.23b | 3.10bc | |

| L9 | 6.97bc | 2.50bc | 23.58bc | 4.54ab | 18.07a | 3.28ab | |

| L10 | 6.51c | 2.36c | 22.64c | 4.50b | 18.57a | 3.36a | |

| 2020 | |||||||

|

Nanjing 9108 |

L6 | 9.31a | 3.14a | 20.68c | 3.75b | 13.26d | 2.77b |

| L7 | 9.09ab | 3.10a | 21.81bc | 3.89b | 14.29cd | 2.82ab | |

| L8 | 8.12b | 2.82a | 25.53a | 4.55a | 15.41bc | 2.85ab | |

| L9 | 6.49c | 2.30b | 23.78b | 4.45a | 16.29ab | 2.99ab | |

| L10 | 6.31c | 2.27b | 22.61bc | 4.42a | 16.91a | 3.13a | |

|

Yangnong xiang28 |

L6 | 8.19a | 2.80a | 22.86b | 4.17b | 12.83d | 2.56b |

| L7 | 8.07a | 2.78ab | 23.41b | 4.19b | 13.96cd | 2.64ab | |

| L8 | 6.96b | 2.42bc | 26.92a | 4.83a | 14.68bc | 2.68ab | |

| L9 | 6.02bc | 2.12c | 24.98ab | 4.63ab | 15.72ab | 2.86ab | |

| L10 | 5.76c | 2.05c | 23.88b | 4.55ab | 16.30a | 2.98a | |

| Year/Cultivar | Treatment | RTSL (cm-2) | RTGL (cm-2) | RGWL (mg cm-2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | ||||

|

Nanjing 9108 |

L6 | 0.474bc | 0.454b | 12.45a |

| L7 | 0.495b | 0.465b | 12.53a | |

| L8 | 0.540a | 0.502a | 12.73a | |

| L9 | 0.472bc | 0.433bc | 12.41a | |

| L10 | 0.443c | 0.411c | 12.33a | |

| 2020 | ||||

|

Nanjing 9108 |

L6 | 0.487bc | 0.462ab | 12.23a |

| L7 | 0.519ab | 0.486a | 12.34a | |

| L8 | 0.543a | 0.500a | 12.40a | |

| L9 | 0.465bc | 0.422b | 11.97a | |

| L10 | 0.443c | 0.406b | 11.80a | |

|

Yangnong xiang28 |

L6 | 0.449bc | 0.427b | 11.74a |

| L7 | 0.478b | 0.444b | 12.16a | |

| L8 | 0.520a | 0.478a | 12.18a | |

| L9 | 0.455bc | 0.413bc | 11.81a | |

| L10 | 0.429c | 0.393c | 11.74a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).