1. Introduction

The speed of light, as one of the fundamental constants in modern physics, and its invariance is a core assumption of the theory of relativity. Since Einstein proposed the principle of the constancy of the speed of light, the scientific community has generally believed that the speed of light is constant in a vacuum. However, in recent years, a series of experimental results have shown that the speed of light is not immutable under specific space-time conditions. Experiments such as the radar echo delay experiment [

1,

2,

3], as well as the gravitational lensing effect [

4,

5,

6], all indicate that the speed of electromagnetic waves will slow down when propagating near massive celestial bodies. These phenomena suggest that the speed of light is not absolutely constant. Theoretical research and observations related to the variation of the speed of light have gradually attracted widespread attention in the academic community.

Based on astronomical observation results, this paper proposes the principle of relative variation of the speed of light and deeply explores the compatibility between this principle and the principle of the constancy of the speed of light. The study analyzes the energy differences caused by the relative variation of the speed of light in a vacuum, and elaborates how this difference leads to the spontaneous accelerated motion of objects and the source of the kinetic energy of objects during the acceleration process. The study finds that there is a phenomenon of relative variation in the speed of light, which has opened up a new field for the study of the laws of material motion. Moreover, the vacuum dynamics mechanism also provides a brand-new physical perspective for explaining the physical mechanism of universal gravitation and the dark energy that drives the accelerated expansion of the universe [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

2. Discussion on the Covariant Relationship between Space-Time and the Speed of Light

2.1. Proposal of the Principle of Relative Variation of the Speed of Light [13,14,15]

In a vacuum environment, according to the principle of the constancy of the speed of light, the speed of light measured at any point is always equal. Taking two points A and B as an example, the mathematical expression is:

In the formula, c represents the speed of light, Δs represents the distance that light travels in a vacuum, and Δt represents the time required for light to travel a distance of Δs.

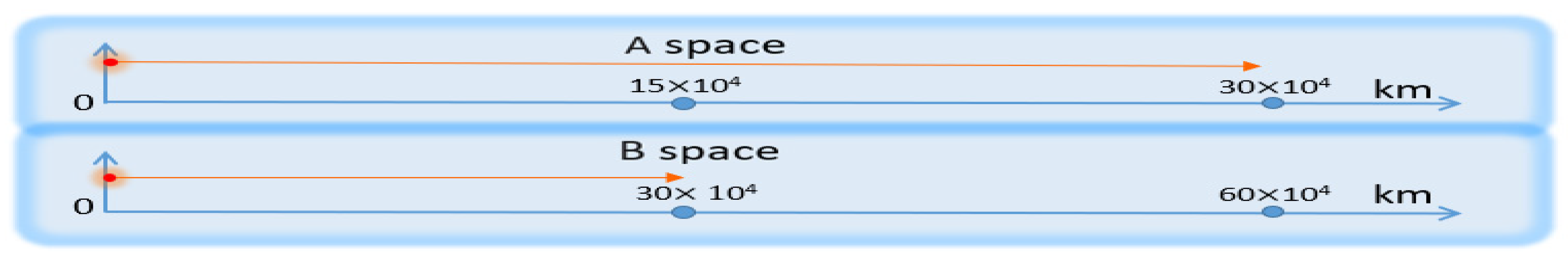

Now assume that the space where point B is located has shrunk by 50% relative to the space where point A is located. According to the principle of the constancy of the speed of light, the speeds of light measured at points A and B respectively are still equal (both are, for example, 300,000 kilometers per second). However, at this time, 300,000 kilometers in space B is only equivalent to 150,000 kilometers under the scale of space A. Therefore, the speed of light in space B should be 50% slower than the speed of light in space A, as shown in

Figure 1.

Based on the above analysis, on the basis of the principle of the constancy of the speed of light, a postulate named the “principle of relative variation of the speed of light” is further derived: when the space undergoes relative expansion or contraction, the speed of light within it will also change relatively in the same proportion. This principle seemingly contradicts the principle of the constancy of the speed of light, but in fact, it is an inevitable result deduced from following the principle of the constancy of the speed of light. Given that the gravitational field in the universe changes continuously with space, then the spaces of various parts of the universe are also constantly expanding and contracting. Thus, it can be known that the speed of light in the universe also undergoes relative changes in different spaces. This is a new expansion of the understanding of the speed of light based on the principle of the constancy of the speed of light, and the principle of relative variation of the speed of light is an important theoretical basis of vacuum dynamics.

2.2. The Correlation between Time, Space and the Speed of Light

To satisfy the principle of the constancy of the speed of light, if

expands by a certain multiple relative to

,

should expand by the same multiple relative to

. Let the multiple be k, that is;

Combining and arranging the above formulas, we get:

The distance that light travels per second in any space is 300,000 kilometers. That is to say, the speed of light should change by the same multiple as the space changes relatively, that is:

Combining and arranging the above two formulas, we get:

Formula (2-5) shows that in a vacuum, the speed of light, the spatial scale and the passage of time between any two points all change according to the same proportion, which reflects a deeper internal correlation among the three.

3. Energy Difference Caused by the Speed of Light Difference in Vacuum Space

3.1. Energy Difference of Photons Caused by the Speed of Light Difference

If there is a speed of light difference between space A and space B, then there must be a time difference between the two points. The time difference further leads to a frequency difference, and the frequency difference in turn causes an energy difference of photons.

Next, we prove the corresponding conversion relationship formula of the frequency between the two points. According to the proportional relationship formula, from formula (2-5), we can get:

Let

and

be the frequency periods respectively, and define:

From the relationship formula between frequency and period

, we can get:

Substitute the above relationships into formula (3-1) to obtain the conversion relationship formula of the frequencies between the two spaces:

That is to say, the relative speed of light difference will produce the phenomenon of redshift [

16,

17,

18,

19].

According to the relationship between frequency and photon energy E = hf, combined with the proportional relationship formula of frequency (3-4), we can obtain the conversion relationship of photon energy between the two spaces:

If , then after the photon energy in space B is converted to space A, its energy is reduced by 50%. It is worth noting that the energy difference of photons between the two spaces has nothing to do with the photons themselves, but is only related to the speed of light difference between the two spaces.

3.2. Speed of Light Difference and Internal Energy Difference of Objects

According to Einstein’s mass-energy equation:

We can obtain the relationship between the internal energy of an object, its rest mass, and the speed of light. Suppose there are objects with the same mass

in two spaces A and B, and their internal energies in the two spaces are respectively:

From this, we can derive the conversion relationship of the internal energy of the object in the two spaces:

When the speeds of light in spaces A and B are equal, the internal energies of the objects are also equal. However, when the speeds of light are not equal, the internal energy of the object will change, and this change is a multiple of the square of the speed of light ratio .

The speed of light difference only affects the energy of the object, rather than providing or absorbing energy for the object. There is a deeper internal connection between the speed of light and the energy of the object.

3.3. Three Energy Spaces Formed by the Speed of Light Difference

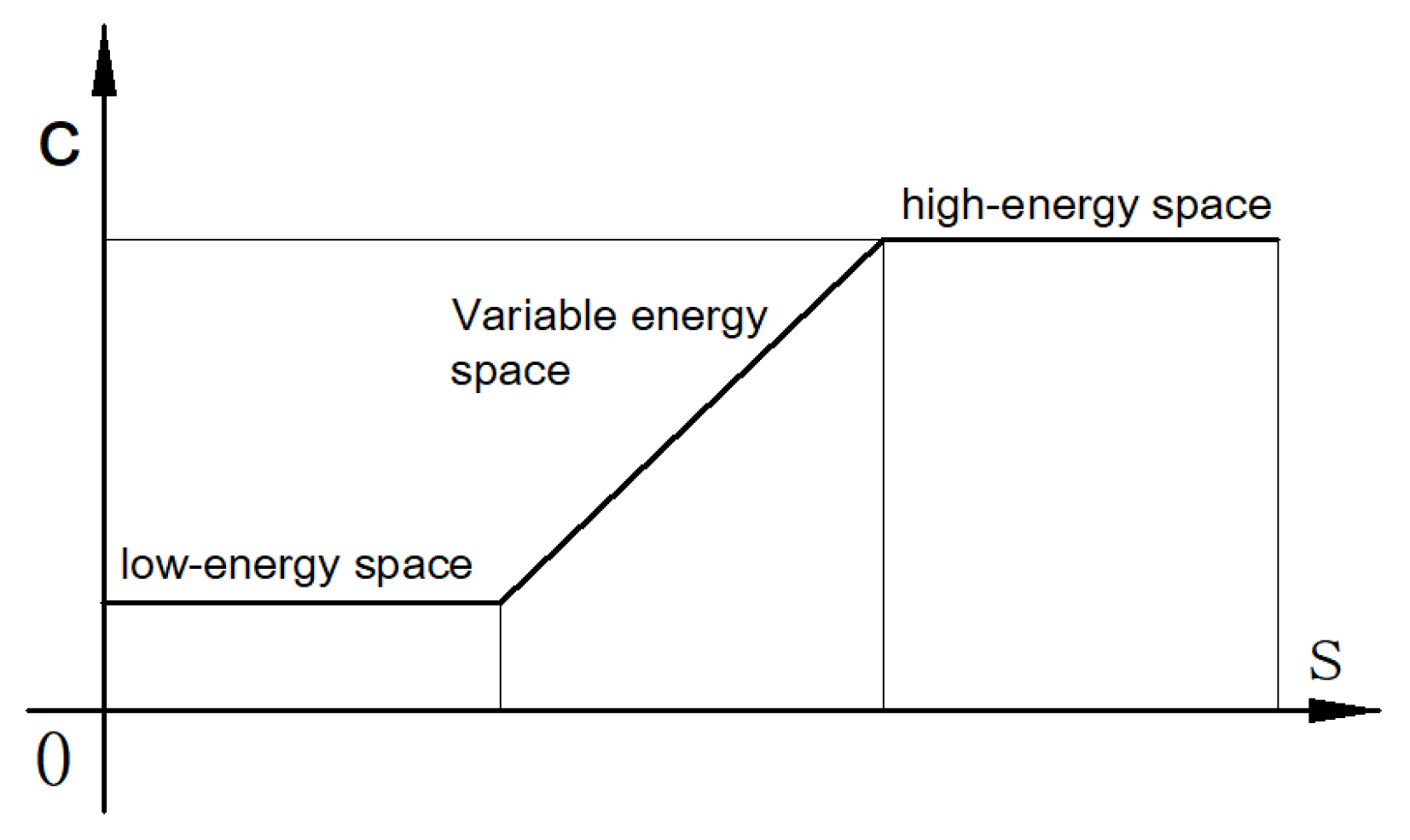

The speed of light has a direct impact on the energy of an object. Now, the space with a relatively high speed of light is called a high-energy space, the space with a relatively low speed of light is called a low-energy space, and the space between the high-energy space and the low-energy space is called a variable-energy space. In the variable-energy space area, the speed of light c changes with the spatial position, resulting in the internal energy of the object varying with the spatial position.

The division of the three energy spaces is shown in

Figure 2. This division is helpful for systematically studying the influence of the speed of light difference on the motion of matter.

4. Principle of Minimum Energy

The principle of minimum energy [

20,

21,

22] is a fundamental law in physics, which is widely applicable to various physical fields and serves as a core principle for understanding the behavior of objects and systems in nature. According to this principle, objects or systems will spontaneously tend towards the state of minimum energy under ideal conditions. Whether at the macroscopic scale of celestial bodies or at the microscopic level of atoms and molecules, objects and systems will develop towards the state of minimum energy. The system gradually adjusts to a stable state with the minimum energy through the exchange, conversion, or transfer of energy.

The pursuit of the lowest energy state is an inherent property of all objects and also an important theoretical support for vacuum dynamics.

5. Spontaneous Movement of Objects and the Acceleration Field

5.1. Spontaneous Movement of Objects and Energy Conversion

In a variable-energy vacuum space where the speed of light changes continuously, objects will spontaneously move towards the region with lower internal energy, and this kind of movement conforms to the principle of minimum energy.

Suppose that the object is not affected by any external force and does not do work externally during this spontaneous movement process. Then the total energy of the object should remain unchanged, and the change amount of its total energy ΔE should be zero. This means that the sum of the change amount of the object’s internal energy ∆Ei and the change amount of its kinetic energy ∆Ev is zero, that is:

Therefore, we can obtain:

From the above derivation process, it can be seen that the kinetic energy increased by the object during the spontaneous movement process completely comes from the decrease of the object’s internal energy. In this process, only the excess internal energy converted when the object moves towards the lower internal energy state is the only source of the object’s kinetic energy. This not only ensures the spontaneity of the entire movement process but also satisfies the law of conservation of energy.

5.2. The Spontaneous Force Caused by the Difference in Internal Energy

In a variable-energy vacuum environment, objects will spontaneously accelerate towards the direction of the lower energy state. Since it is the accelerated movement of the object, there must be a force acting on it. Since this is a spontaneous movement without the action of external forces, this force is called the spontaneous force of the object.

Suppose that the displacement of the object during the accelerated movement process is

. According to the definition of work, the work

done by the force

can be expressed as:

Thus, the acting force

can be obtained:

Among them, the work

represents the increment of kinetic energy

∆Ev, and it is also equal to the decrement of internal energy

-∆Ei,

Substitute it into formula (5-4) to get:

Substitute the specific change form of the internal energy to obtain:

It can be seen from the above formula that the spontaneous force is equal to the negative gradient of the square of the speed of light with respect to the spatial change. In a space with a variable speed of light, even if the object is in a stationary state, there is still a spontaneous force that makes it move towards the lower energy state, which is similar to the gravity of an object in a gravitational field.

Through the above discussion, we can have a clearer understanding of the relationship between the change of the object’s internal energy and the spontaneous force, and reveal the dynamic mechanism of spontaneous movement in a variable-energy environment.

5.3. Acceleration Caused by the Speed of Light Difference

To find the acceleration obtained by an object in a variable-energy space, for an object with mass m, let the acceleration generated by the spontaneous force

be

:

Substitute formula (5-7) into the above formula, and we can get:

Suppose

, the acceleration

is the negative gradient of the square of the speed of light

with respect to the spatial change, which can be expressed as:

The speed of light c forms a scalar field in space, while forms a vector field in space. It can be seen from formula (5-9) above that the acceleration obtained by the object is only related to the rate of change of the square of the speed of light in space, and has nothing to do with the mass of the object. This physical characteristic is consistent with the property of the gravitational field.

Although the continuous relative change of the speed of light in space does not directly exert any force on the object, it provides the necessary environmental conditions for the spontaneous movement of the object.

6. The Space-Time Structure of Spherically Symmetric Objects and General Relativity

By applying the theory of vacuum dynamics, we deeply explore the influence of spherically symmetric objects on the space-time structure, which is of great significance for understanding the physical mechanism of gravitational phenomena. The corresponding relationship with the Schwarzschild solution of general relativity has been discovered, revealing the deep internal connection between the curvature of space-time and the relative variation of the speed of light.

6.1. Theoretical Framework

1. Foundation of Classical Gravity

2. Hypothesis of Vacuum Dynamics

As is well known, the gravitational interaction between objects is not an action at a distance, but is realized by changing the physical state of space. A large number of astronomical observations clearly show that celestial bodies have an influence on the propagation speed of light: in the region closer to the object and with a larger mass of the object, the speed of light is relatively slower. According to the theory of vacuum dynamics, the relative variation of the speed of light in space can enable an object to obtain an acceleration

. Therefore, we make the hypothesis that the variation of the speed of light in space is exactly the physical cause of the generation of the gravitational acceleration

, that is:

Let

, and establish the differential relationship:

The above formula can be regarded as an expression of the gravitational field strength generated by a spherically symmetric object in space. Next, we will discuss how a spherically symmetric object affects the distribution of the speed of light in space and what impact it has on space and time.

6.2. Mathematical Derivation

1. Solving the Schwarzschild Metric

Integrate formula (18) above to obtain:

When

, let

,

Note: is the background speed of light in vacuum far from the influence of the mass of the sphere, which is consistent with the speed of light c in the Schwarzschild solution of relativity.

The ratio of the squares of the speed of light:

The above formula shows that under the condition of spherically symmetric vacuum, the vacuum dynamics theory can reproduce the classical structure in general relativity, that is, the form of the Schwarzschild metric [

23,

24,

25]. Specifically, the consistency between these two theories strongly affirms the correctness of the vacuum dynamics theory, which means that under the basic symmetry and boundary conditions, the vacuum dynamics theory can reach the same conclusion as general relativity. Achieving this result also proves the correctness of the initial hypothesis (

).

The space-time components of the Schwarzschild metric in general relativity are:

2. Explaining the Physical Essence of the Law of Universal Gravitation from the Spatial Distribution of the Speed of Light Field

The spatial distribution formula of the speed of light field:

The above formula explains the distribution of the speed of light c(r) in space caused by the mass of a spherically symmetric object. Obviously, this speed of light field c(r) presents a monotonically decreasing distribution pattern from far to near. In this way, a variable-energy space with low internal energy and high external energy, centered around the sphere, is established. Based on this, other objects will naturally accelerate towards this low-energy space (that is, towards the center of the sphere). Its acceleration is determined by the negative gradient of the speed of light field, and this spontaneous force generated by the object is what we usually call gravity. The increase in the kinetic energy of the object comes from the decrease in its internal energy. Therefore, there is only the interaction of the scalar field of the speed of light between objects, and there is no direct mutual attractive force involved. This is the explanation of the physical essence of the law of universal gravitation of spherically symmetric objects by the theory of vacuum dynamics.

6.3. Derivation of the Space-Time Expansion Effect

1. Time Dilation Effect

According to formula (2-5), the ratio of the speed of light is equal to the ratio of time:

Find the ratio of the speed of light

:

Substitute formula (6-11) into formula (6-10) to get:

In the above formula, is the time interval at the point , and is the time interval at the position r. This formula describes the relative difference between the time passage rate at different spatial positions r of the spherically symmetric object and . The above formula shows that the closer to the object, the slower the passage of time. When r approaches infinitely, the time passage corresponding to almost stops. The value of r at this time is called the Schwarzschild radius . The Schwarzschild radius is an important concept in general relativity and is crucial in the research of cutting-edge fields such as black holes and gravitational singularities. The ability to derive this concept also reflects the correctness of the vacuum dynamics theory.

Formula (6-13) is completely consistent with the Schwarzschild time dilation formula

2. Space Expansion Effect

Based on the principle of the constancy of the speed of light, the speed of light at any point in a vacuum must remain the same, which means that the scaling ratios of time and space must be the same. Therefore, the scaling ratio of time is the scaling ratio of space, and the relationship formula for the scaling of the vacuum space can be obtained:

Among them,

is the spatial interval at the point

, and

is the spatial interval at the position r. This relationship is applicable to the scale comparison between the local spaces of static observers, and has the following corresponding relationship formula with the Schwarzschild space expansion:

To sum up, from the perspective of vacuum dynamics, the influence of spherically symmetric objects on time, space, and the distribution of the speed of light has been verified, and the corresponding calculation formulas have been successfully derived, thus clearly clarifying the physical causes of the generation of the law of universal gravitation.

It should be emphasized that the corresponding relationship between vacuum dynamics and general relativity has profound physical connotations. As shown in formula (2-5), time, space, and the speed of light all strictly follow the law of proportional co-evolution. This characteristic fundamentally explains why two seemingly different theoretical frameworks can both derive the Schwarzschild space-time factor. More importantly, there is a complementarity in the physical interpretations of the two: the gradient change of the speed of light field () is essentially equivalent to the geometric deformation of the space-time structure - the adjustment of the space-time metric at any spatial point must be accompanied by a new gradient distribution of the speed of light, and the existence of the speed of light gradient directly gives rise to the local acceleration field (that is, gravity). This reveals the physical essence of the generation of the gravitational effect by the curvature of space-time: the speed of light field is related to the space-time geometric structure through its spatial gradient. This intrinsic dynamic mechanism provides a clearer physical analysis for the classic proposition that “the curvature of space-time is gravity”.

7. The Source of Dark Energy

Based on the theory of vacuum dynamics, the hypothesis is proposed that the speed of light in the universe presents a distribution with a higher value at the center and a lower value at the edge. Celestial bodies spontaneously move towards the regions with a lower speed of light, thus forming the phenomenon of the expansion of the universe. Through this hypothesis, the assumptions of anti-gravity and dark energy are avoided. In fact, dark energy [

26,

27] is the internal energy released by celestial bodies when they move towards the space with a lower speed of light and converted into kinetic energy.

Astronomical observations support this hypothesis in three aspects:

1. Delay in the Propagation Time of Light: Many astronomical observations show that the time required for light from distant celestial bodies to reach the Earth significantly exceeds the predictions of traditional theories [

29,

30]. Moreover, as the distance of celestial bodies increases, the time delay of light also becomes greater, indicating that the speed of light of more distant celestial bodies is relatively slower.

2. The Phenomenon of Redshift: Astronomical observations have found that when observing celestial bodies at a distance of more than 5 billion light-years, according to the existing calculation methods, it is often concluded that the recession speed of celestial bodies is greater than the speed of light, which is a result contrary to common sense [

28]. This indirectly proves the assumption that the speed of light is slower the farther away it is from us. Because this extremely large redshift should contain the redshift component caused by the slowdown of the speed of light, and only by deducting this component can the correct result be calculated.

3. The Distribution of the Speed of Light Gradient: The distribution of the speed of light gradient actually reflects that the interior of the universe is a high-energy space, and the edge is a low-energy space. This is consistent with the evolutionary process of energy diffusion from the center to the outside after the Big Bang.

It is recommended that in future research on dark energy, more attention should be paid to the relative variation of the speed of light in the universe and more attention should be paid to the analysis of redshift data to verify the distribution model of the speed of light gradient and provide more evidence for revealing the essence of dark energy.

8. Conclusions

The theory of vacuum dynamics is established on the basis of the principle of relative variation of the speed of light, constructing a self-consistent theoretical system. This theory holds that the gradient distribution of the speed of light in the vacuum space is the fundamental cause of the spontaneous movement of objects, and the kinetic energy required for the accelerated movement of objects comes from the internal energy of the objects. This provides a unified interpretive framework for the physical mechanisms of the law of universal gravitation and dark energy.

The study has found that there is a fixed variable ratio relationship among time, space, and the speed of light. Therefore, it is an inevitable result that the theory of vacuum dynamics and general relativity have the same description of space-time changes.

In addition, the theory of vacuum dynamics provides a theoretical framework for the unification of the gravitational field and the electromagnetic field, and lays a solid theoretical foundation for the research of anti-gravitational field technology.

This paper aims to expound the basic physical ideas of the theory of vacuum dynamics. There are still many issues that need in-depth study. It is hoped that this paper can attract the attention of the academic community to the theory of vacuum dynamics, jointly promote the further development and improvement of this theory, and thus contribute to the progress of the fundamental theories of physics.

References

- Shapiro, I. I. (1964). Fourth Test of General Relativity. Physical Review Letters, 13(26), 789-791. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, I. I., et al. (1971). Fourth Test of General Relativity: New Radar Result. Physical Review Letters, 26(18), 1132-1135. [CrossRef]

- Bertotti, B., Iess, L., & Tortora, P. (2003). A test of general relativity using radio links with the Cassini spacecraft. Nature, 425(6956), 374-376. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. (1936). Lens-Like Action of a Star by the Deviation of Light in the Gravitational Field. Science, 84(2188), 506-507. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, D., Carswell, R. F., & Weymann, R. J. (1979). 0957+561 A, B: Twin Quasistellar Objects or Gravitational Lens? Nature, 279(5712), 381-384.

- Oguri, M., & Marshall, P. J. (2010). Gravitational lensing by galaxy clusters: A comprehensive review. Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan, 62(4), 1017-1044.

- Riess, A. G., et al. (1998). Observational Evidence from Supernovae for an Accelerating Universe and a Cosmological Constant. The Astronomical Journal, 116(3), 1009-1038. [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, S., et al. (1999). Measurements of Omega and Lambda from 42 High-Redshift Supernovae. The Astrophysical Journal, 517(2), 565-586.

- Sahni, V., & Starobinsky, A. (2000). The Case for a Positive Cosmological Lambda-Term. International Journal of Modern Physics D, 9(4), 373-444.

- Frieman, J. A., Turner, M. S., & Huterer, D. (2008). Dark Energy and the Accelerating Universe. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 46(1), 385-432.

- Weinberg, D. H., Mortonson, M. J., Eisenstein, D. J., Hirata, C., Riess, A. G., & Rozo, E. (2013). Observational Probes of Cosmic Acceleration. Physics Reports, 530(2), 87-255. [CrossRef]

- Hinshaw, G., et al. (2013). Nine-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Cosmological Parameter Results. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 208(2), 19. [CrossRef]

- Magueijo, J., & Barrow, J. D. (2002). Varying Speed of Light Theories. Physics Reports, 419(1-3), 1-50.

- Moffat, J. W. (1993). Superluminary Universe: A Possible Solution to the Initial Value Problem in Cosmology. International Journal of Modern Physics D, 2(3), 351-366. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, G. F. R., & Uzan, J.-P. (2005). c is the speed of light, isn’t it? American Journal of Physics, 73(3), 240-247.

- Hubble, E. (1929). A Relation between Distance and Radial Velocity among Extra-Galactic Nebulae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 15(3), 168-173. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. (1917). Cosmological Considerations in the General Theory of Relativity. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 142-152.

- Sandage, A. (1961). The Ability of the 200-Inch Telescope to Discriminate Between Selected World Models. The Astrophysical Journal, 133, 355-392. [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, S., et al. (1999). Measurements of Omega and Lambda from 42 High-Redshift Supernovae. The Astrophysical Journal, 517(2), 565-586.

- Feynman, R. P., Leighton, R. B., & Sands, M. (1964). The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol. II: Mainly Electromagnetism and Matter. Addison-Wesley.

- Goldstein, H., Poole, C., & Safko, J. (2002). Classical Mechanics (3rd Edition). Addison-Wesley.

- Landau, L. D., & Lifshitz, E. M. (1976). Mechanics (3rd Edition). Pergamon Press.

- Schwarzschild, K. (1916). “Über das Gravitationsfeld eines massiven Punktes nach der Einsteinschen Theorie”.Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin (1916): 424–434.

- Einstein, A. (1915). “Die Feldgleichungen der Gravitation”.Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin (1915): 844–847.

- Abramowicz, M. A., & Kluźniak, W. (2005). “A precise determination of black hole spin in GRO J1655-40”. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 438(1), L15-L18. [CrossRef]

-

Perlmutter, S., et al. (1999). “Discovery of a supernova explosion at half the age of the universe.” Nature, 391(6662), 51-54. [CrossRef]

-

Riess, A. G., et al. (1998). “Observational evidence from supernovae for an accelerating universe and a cosmological constant.” The Astronomical Journal, 116(3), 1009-1038. [CrossRef]

- Nojiri, S., & Odintsov, S. D. (2004). “Introduction to modified gravity theories.” International Journal of Modern Physics D, 13(4), 705-750.

- Linder, E. V. (2003). “Exploring the acceleration of the universe.” Reports on Progress in Physics, 69(3), 429-485.

- Liddle, A. R., & Lyth, D. H. (2000). “Cosmological Inflation and Large-Scale Structure.” Cambridge University Press.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).