1. Introduction

The straddle-type monorail tour-transit system (MTTS) has developed rapidly in recent years. At present, there are more than 30 MTTS projects under construction or operation over the world [

1]. It uses lightweight steel box girders as the supporting track beam and steel column as the substructures, which is easy for construction, has good ornamental characteristics, and is very suitable for scenic areas. With these configurations, the weight of the track beam of MTTS is light, and the overall stiffness is relatively low. Compared with the supporting structures of general transportation systems, the dynamic response of the track beam of MTTS is more significant. In particular, the lateral stiffness is an essential factor affecting the smoothness and comfort of train operation and hence, the related limited values must be reasonably determined. However, the design code for MTTS, i.e., the “Large-scale amusement device safety code (GB 8408-2018) [

2]”, does not have specific regulations in this respect. Of course, provisions in relevant codes (e.g., design code for urban rail transit bridge (GB/T 51234-2017) [

3] and monorail in urban transit systems (GB 50458-2022) [

4]) can be used for reference. However, practical use has proven that these codes are not completely applicable because of the structural diversity in various transit systems and the design concepts of different codes. Therefore, it is important to carry out targeted research and improve relevant design standards to promote the development of modern tourism systems.

In general, existing studies on the dynamic responses of transportation systems were conducted through numerical simulations, e.g., using finite element method (FEM) and multi-body dynamics (MBD). For example, Gao et al. developed a co-simulation model using ANSYS (FEM software) and SIMPACK (MBD software) to study the effects of vehicle speed and bridge pier height on a rail system [

5]. Liu studied the dynamic response of a T-girder continuous rigid frame bridge: by using a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) software, the aerodynamic parameters and their effects of the bridge under passing vehicles were simulated [

6]. Furthermore, many studies have been able to consider the coupling effect of various loadings. For example, Miao et al. [

7] established a refined space vibration model of a wind-vehicle-bridge system with time-varying characteristics to investigate the dynamic features of bridges. Huang et al. [

8] utilized a co-simulation method to analyse the mechanical properties of bridges under wind–vehicle–bridge coupling actions. Chen et al. [

9] and Wang et al. [

10] studied the aerodynamic performance of a vehicle‒bridge system under the action of a crosswind. Zou et al. [

11] developed a joint model to analyse the dynamic response of a wind—monorail car—suspended bridge system under wind loadings. In addition, laboratory tests on the coupling system were reported. Luo et al. [

12] measured the aerodynamic coefficients of relevant bridge and vehicle models under the action of crosswind through a wind tunnel test. Jiang et al. [

13] focused on the most unfavourable load that long-span bridges bore when vehicles and subways were in operation at the same time, and relevant models were established for dynamic response studies. Guo et al. [

14] performed wind tunnel tests and numerical simulations to investigate the dynamic characteristics of bridge; the wind‒car‒bridge coupling model was also developed via FEM and CFD. It should be noted that these studies are dominantly focus on rail transportations, results in general monorail system are still limited, not to mention relevant studies on MTTS. Nevertheless, the methodologies of general transportation system can be used as great reference.

In terms of lateral stiffness limit, a perspective more inclined towards practical application, research has made great progress on general transit systems. In general, the main body of vehicle can be simulated or constructed by using MBD. Then, a targeted dynamic evaluation system can be proposed based on the results of the dynamic response of vehicle and bridges [

15]. Xiang et al. [

16] investigated the lateral stiffness limit of a suspension bridge through a combination of wind tunnel test and numerical simulation. Zhou et al. [

17] investigated the effects of the height of the bridge pier and the lateral stiffness of the bridge beam on the dynamic response of a vehicle-bridge system. Zhu et al. [

18] developed multiple suspension bridge models and investigate various methods to improve the structural stiffness of the railway bridges. Liu et al. [

19] proposed an analytical model to quantitatively analyse the influence and mechanism of several important parameters on the mapped deformation of the rail, including the lateral beam deformation and the lateral stiffness of fasteners. Wang et al. [

20] performed numerical simulations of the coupled vibration of 12 track-beam systems with different stiffnesses. In the study, track irregularities and wind-induced lateral loads were considered. Yan et al. [

21] investigated the design value of the torsional stiffness reduction factor for the serviceability limit states. CARDEN et al. [

22] proposed a simplified calculation method based on the elastic stress and stiffness of bridge beams, and the results were found comparable with those obtained by FEM.

To sum up, existing studies on the dynamic response of monorail systems, including MTTS, and effects of lateral stiffness of monorail bridge, i.e., track beams and piers, are limited. Research have reported field tests and numerical simulations of the monorail systems considering track irregularities [23-26], wind loadings [

27], and ground motions [

28]. Moreover, the usage of FEM and MBD on monorails have been verified, providing an effective method for investigating the dynamic effects of MTTS. To the best of our knowledge, no existing studies have focused on the determination of lateral limited values of MTTS.

On the basis of a comprehensive analysis of the existing research and considering the unique structural configurations of MTTS, this work employs FEM and MBD software to establish a wind‒vehicle‒bridge coupling model of MTTS. The effects of variables such as vehicle load and track beam lateral stiffness on vehicle running stability, acceleration, and the lateral force of guide wheels and stabilizing wheels are investigated. Through numerical simulation and parametric analysis, the lateral deflection–span ratio limit and the lateral displacement limit of the pier top were determined based on the riding comfort standard, i.e., the mid-span acceleration of the monorail track beam and the lateral force limit of the monorail train wheels. The results of the study can improve the problem of unclear limits of lateral stiffness of MTTS, which can provide a reference for related research and design.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Influencing Factors

In the dynamic analysis of vehicle‒bridge coupling, with reference to relevant codes, various indexes that representing the dynamic response of MTTS were selected. The evaluation indexes of the dynamic response of track beams are: i) horizontal and vertical deflection at the beam mid-span; ii) acceleration at the beam mid-span; and iii) lateral displacement at the pier top. The evaluation indexes of the dynamic response of monorail trains are: i) wheel unloading rate; ii) acceleration of car body; iii) riding quality); and iv) index of tire stress. It should be noted that the last index is only applicable in monorail systems that utilizing rubber tires.

Main factors influencing the dynamic response of MTTS are the speed of the tourist vehicles, vehicle loadings, the pier height and lateral stiffness of monorail bridge. To lay a solid basis to subsequent analyses, effects of these four influencing factors are firstly analysed in the following.

3.1.1. Effects of Travelling Speed

At present, the MTTS generally serves as an amusement facility, and the maximum speed is 40 km/h under current specifications. In this work, the maximum speed used was km/h, about 1.2 times the maximum operating speed. A total of 10 intervals of vehicle speed were set: 5, 10, …, 50 km/h, so that a comprehensive analysis on the dynamic response can be performed. The model described in

Section 2 is then used, with consideration of train loading (maximum capacity), wind loading, and track irregularities. Dynamic responses of the track beam and monorail train are shown in

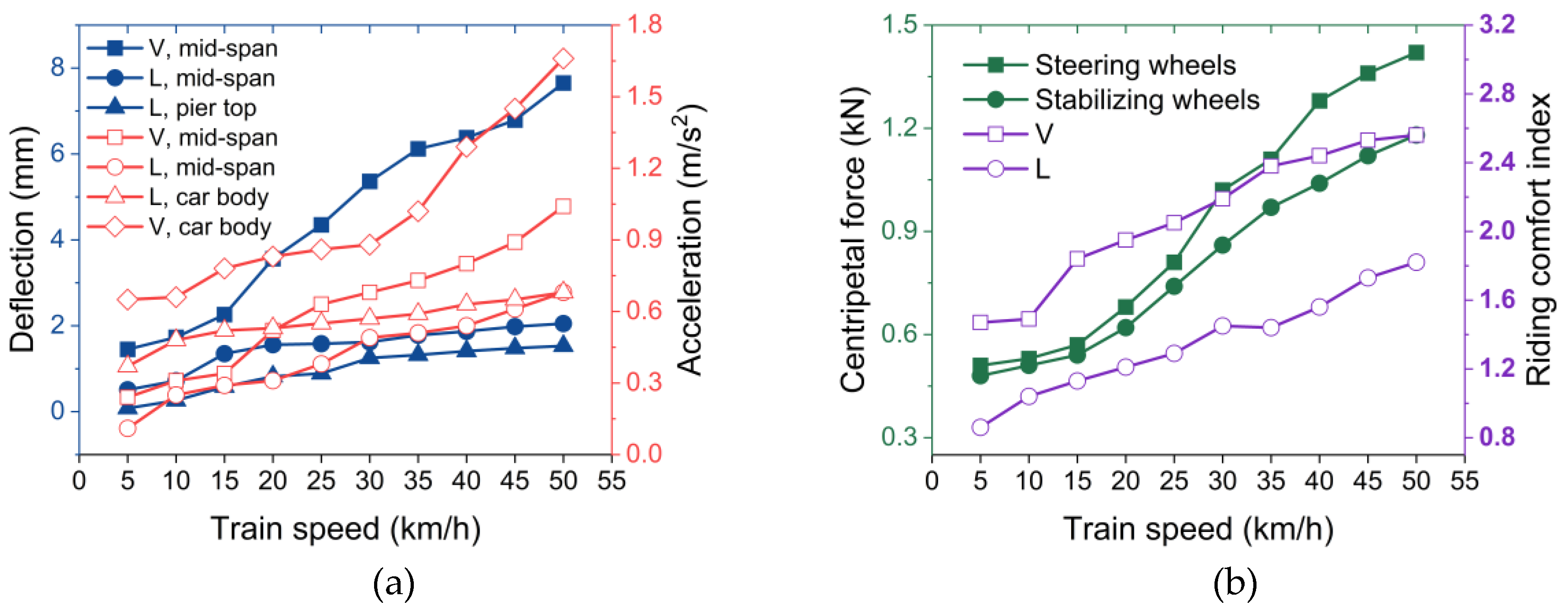

Figure 6.

Figure 6 shows that each kind of dynamic responses continuously increases with vehicle speed. Compared with the other responses, vertical deflection at the mid-span and the vertical acceleration of car body varied significantly with the train speed, indicating that the train speed had the most significant effects on the two. In addition, a significant change of various dynamic responses can be found under a train speed from 20 to 30 km/h. Moreover, in terms deflection and acceleration, vertical responses are more sensitive to the variation of train speed compared to lateral responses, which is also reflected in the curves of riding comfort index in

Figure 6b. It should be noted that the steering wheels and stabilizing wheels are located at the webs of the track beam during monorail operation. Hence, similar patterns of centripetal force can be observed.

3.1.2. Effects of Vehicle Loading

To study the effect of vehicle loadings on the dynamic response of MTTS, three different working conditions were used: 1, no load; 2, full load (3.8 tons); and 3, overloaded (5.3 tons). The train speed commonly used in MTTS are divided into three gears: slow, 10 km/h; medium, 20 km/h; and fast, 30 km/h. The rest of the conditions are the same as those described in

Section 3.1.1. The dynamic responses of the monorail beam and the vehicle are shown in

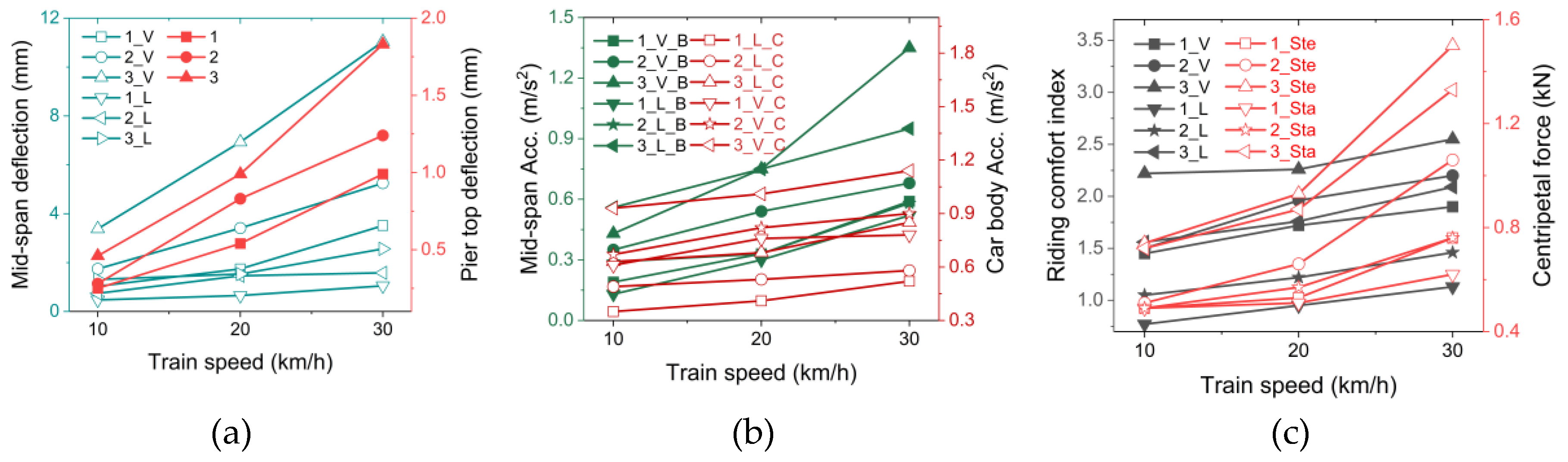

Figure 7.

Figure 7 shows that various types of dynamic response increase as the vehicle loads continuously increases, which are consistent to practical experiences. Specifically, the weight of the vehicle significantly affects the lateral displacement of the pier top, with a greater impact on the vertical deflection at the mid-span than in the lateral direction. Furthermore, this weight has a more pronounced effect on the vertical acceleration response and vertical stability index compared to the lateral direction.

3.1.3. Effect of Pier Height

In this section, six pier heights of monorail bridge, i.e., 2 m, 4 m, 6 m, 8 m, 10 m and 15 m, were used to analyse the dynamic response of MTTS. The designed maximum train speed (40 km/h) was used in simulations. The rest of the conditions are the same as those described in

Section 3.1.1. The dynamic responses of the monorail beam and vehicles are shown in

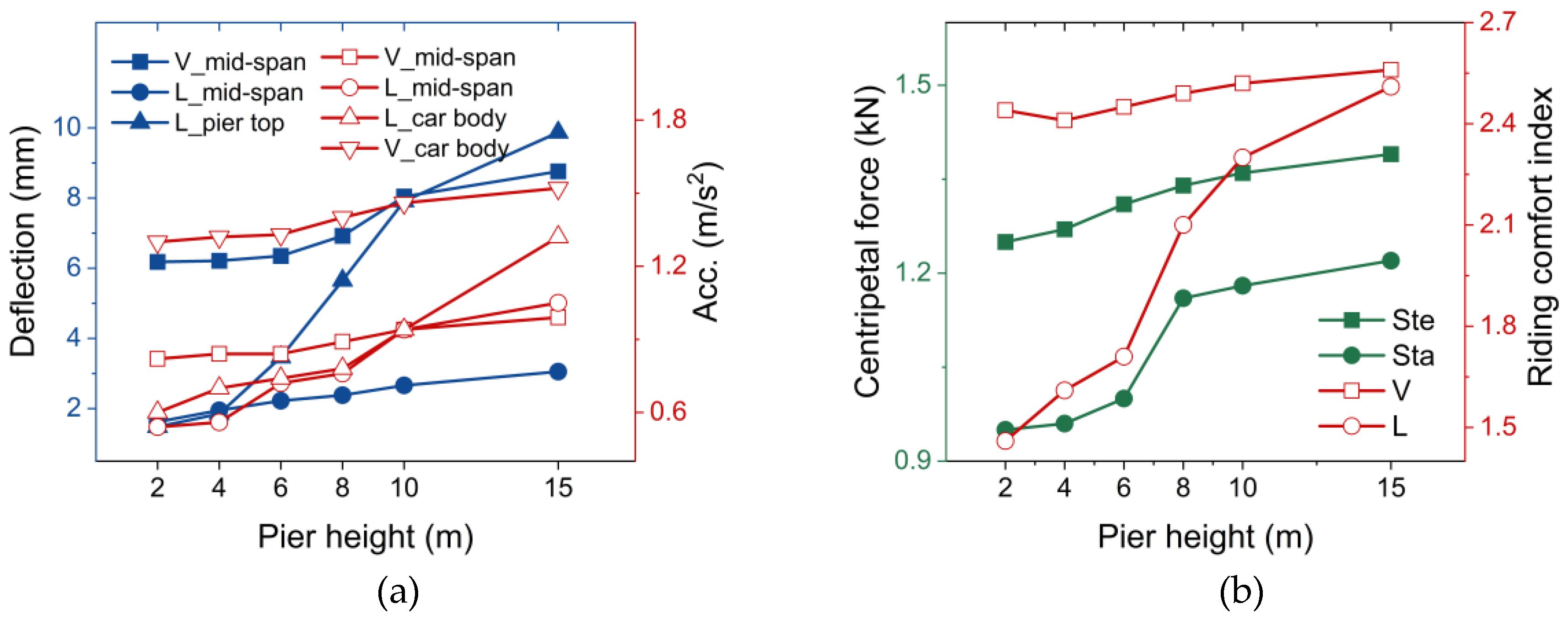

Figure 8.

As shown in

Figure 8, similar patterns can be found in various dynamic responses versus pier height curves, indicating that the induced dynamic responses generally increase with the increasing pier height. The effect of the pier height on the variation in the lateral displacement of the pier top was more significant than that of the other responses. The variation in the lateral riding comfort index is also significant. Nevertheless, the overall lateral comfort index is less than that of vertical.

3.1.4. Effects of Beam Stiffness

By changing the width and stiffness of the monorail beam, the lateral stiffness of the monorail beam can be altered and hence, effects of lateral stiffness on the track beam can be further investigated. To this end, this work adopted the method of changing the transverse moment of inertia of track beams. The specific method is as follows: the lateral stiffness of the beam

EI was multiplied by a reduction factor

Rh, where

Rh were set to values of 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 1.0, 1.2, 1.5 and 1.8, to ensure representativeness and coverage of the lateral stiffness of practical track beams. The remaining conditions are as described in 3.1.1. Results are shown in

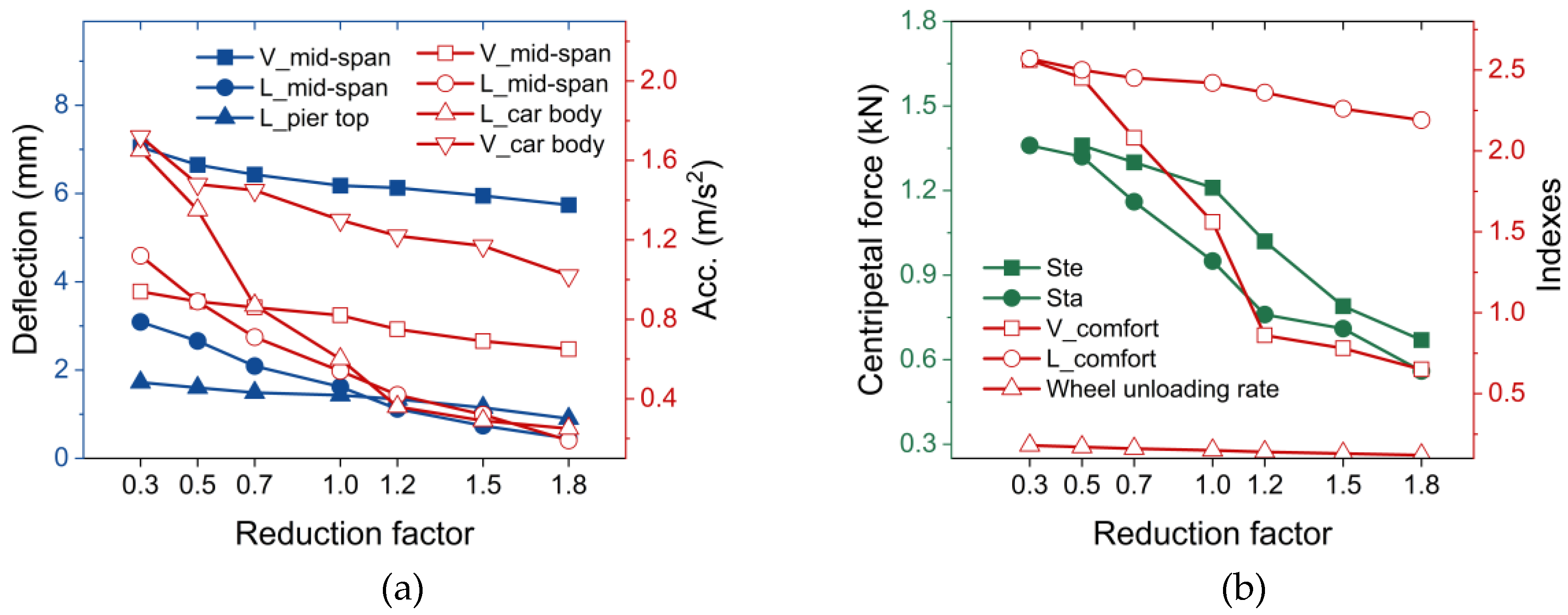

Figure 9.

As shown in

Figure 9, all kinds of dynamic response decrease with increasing beam lateral stiffness. The variations in the mid-span lateral deflection and the vehicle body lateral acceleration with the girder lateral stiffness were more significant than the other responses were, and the two kinds of wheel vertical forces and stationarity indicators also varied significantly with the girder lateral stiffness.

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis

3.2.1. Variance-Based Methods

In the variance-based sensitivity analysis, the ratio of the parameter influencing factors to the output variance was calculated to assess the sensitivity of the parameter to the output. In this work, the Sobol index analysis method combined with the Santelli method [

29] was used to perform sensitivity analysis. This method uses quasi-random number sequences to construct two random number matrices

A and

B, then constructs matrix

Ci on the basis of

A and

B, and inputs the parameters of matrices

A and

B and each row of

Ci into the model calculation to obtain three matrices. output vectors

uA, uB, and uC, from which the first-order sensitivity coefficient

Si and the overall sensitivity coefficient

STi of the

i-th parameter can be calculated. The method is expressed as follows:

3.2.2. Sensitivity Analysis of the Lateral Response

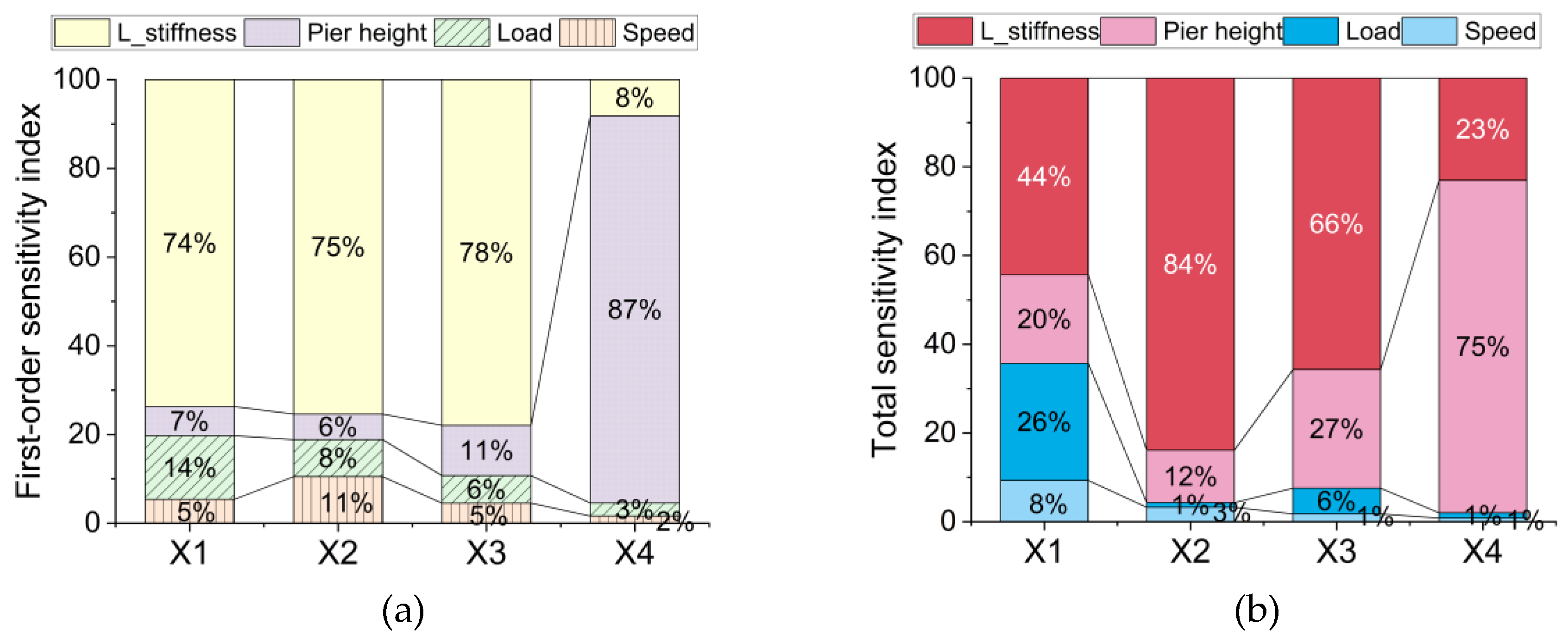

In the sensitivity analysis of the horizontal response, the four influencing factors mentioned above were set as sensitivity input parameters. A MATLAB program was compiled based on the Saltelli method. The sensitivity indicators of each parameter are obtained after the determined parameters are input, as shown in

Figure 10.

As shown in

Figure 10, the height of the monorail girder pier and the lateral stiffness of the beam have the greatest impacts on the lateral response of the overall structure. Among them, the pier height significantly contributes to the lateral displacement of the pier top, accounting for 87% of the first-order sensitivity index and 75% of the total sensitivity index: beam lateral stiffness to car body lateral acceleration and monorail beam midspan. The maximum lateral acceleration and the maximum lateral displacement at the midspan significantly contribute to 74%, 75% and 78% of the first-order sensitivity indicators and account for 44%, 84% and 66% of the total sensitivity indicators, respectively.

3.3. Determination of Lateral Stiffness Index

For the evaluation index of bridge lateral stiffness, the width‒span ratio, lateral deflection‒span ratio, natural frequency and amplitude are usually chosen. Compared with other indicators, the lateral deflection-to-span ratio can fully reflect the interaction between the vehicle and the bridge system and thus is a more comprehensive indicator for evaluating the performance of bridge structures. Accordingly, the lateral deflection–span ratio is used in the present study to evaluate the lateral stiffness of bridges.

As an important structure in travel and transportation systems, the lateral stiffness limit of the pier column was chosen in the present study as the evaluation scale for the lateral displacement of the pier top. In addition, the mid-span lateral acceleration, stationarity index and wheel lateral force limit are more deterministic; therefore, the above three evaluation criteria are used in the lateral stiffness index in this paper. With reference to other specifications and consideration of structural configurations of MTTS, the evaluation limit of the mid-span lateral acceleration is 0.98 m/s2; the stability index uses the excellent level limit of the bus stability rating criteria after considering the comfort; and the vertical force limit of the guide wheels is used as the vertical force limit. The evaluation limit was set to 1.37 kN according to the technical conditions of the polyurethane wheel 200‒68 tire provided by the manufacturer.

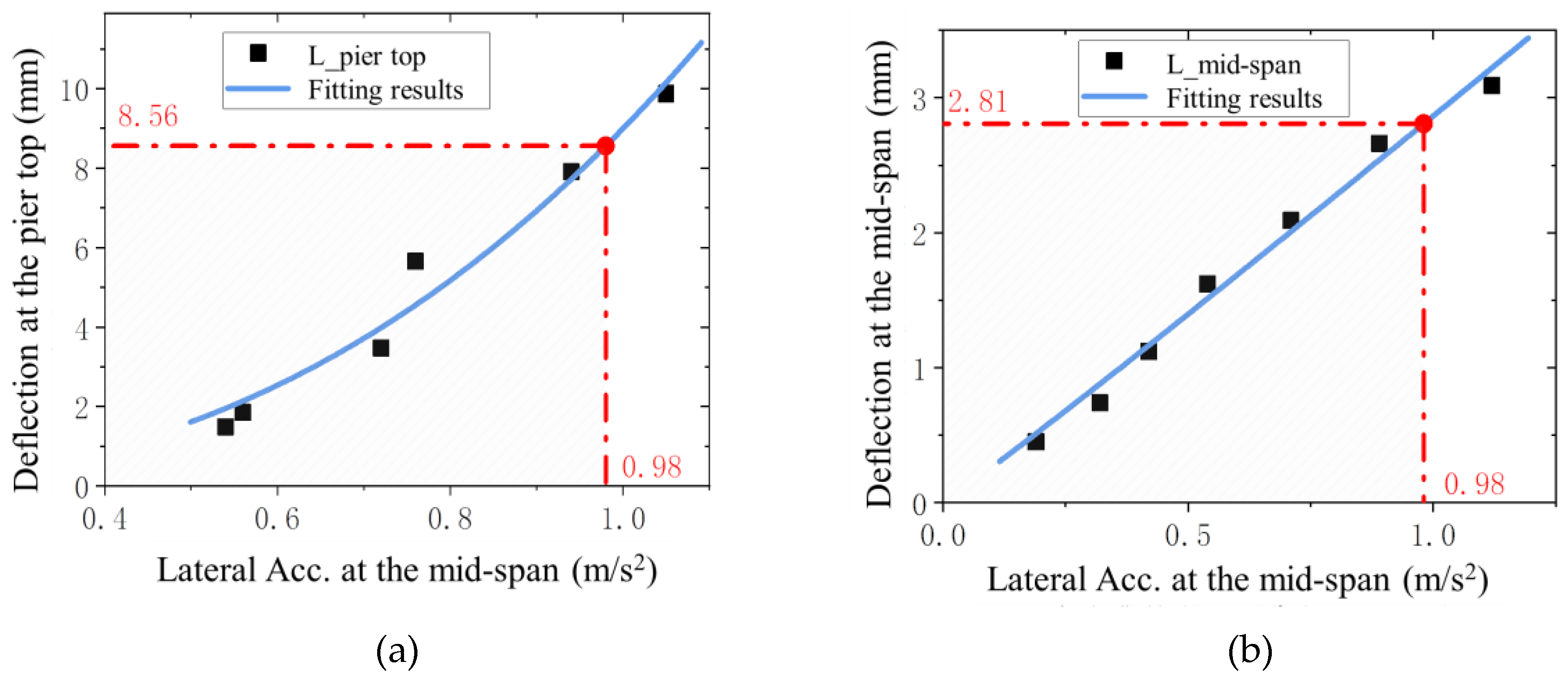

3.3.1. Lateral Acceleration Perspective

Based on the previously obtained data, the maximum transverse acceleration in the span and the transverse displacement at the top of the pier under the variation of the pier height, as well as it’s fit to the transverse deflection in the span under the variation of the transverse stiffness are shown in

Figure 11.

As shown in

Figure 11, the fitting coefficients

R2 of the lateral deflection at the pier top and the mid-span are 0.96 and 0.98, respectively, indicating that the calculated function fits well and can reflect the actual variation patterns of the parameters. Point interpolation was then performed on the basis of the fitting function. When the lateral acceleration at the mid-span was 0.98 m/s2, the lateral horizontal displacement of the pier top was 8.56 mm, and the lateral deflection at the mid-span was 2.81 mm. On the basis of the calculation formula for the lateral deflection–span ratio, the limit of the lateral deflection–span ratio is approximately L/3600.

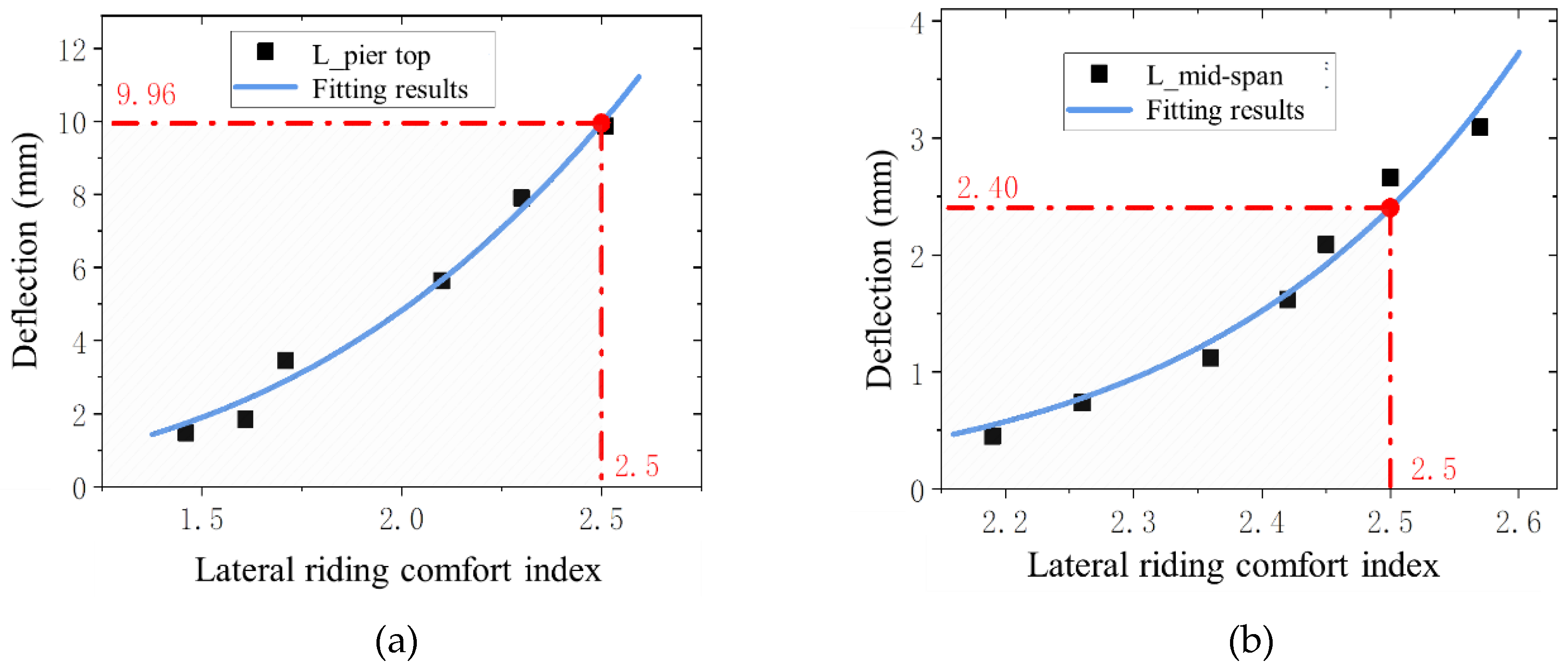

3.3.2. Lateral Riding Comfort Perspective

Based on the previously obtained results, the fitting results of the lateral stability and the lateral displacement of the pier top under the changes in pier height and lateral deflection under the changes in lateral stiffness are shown in

Figure 12.

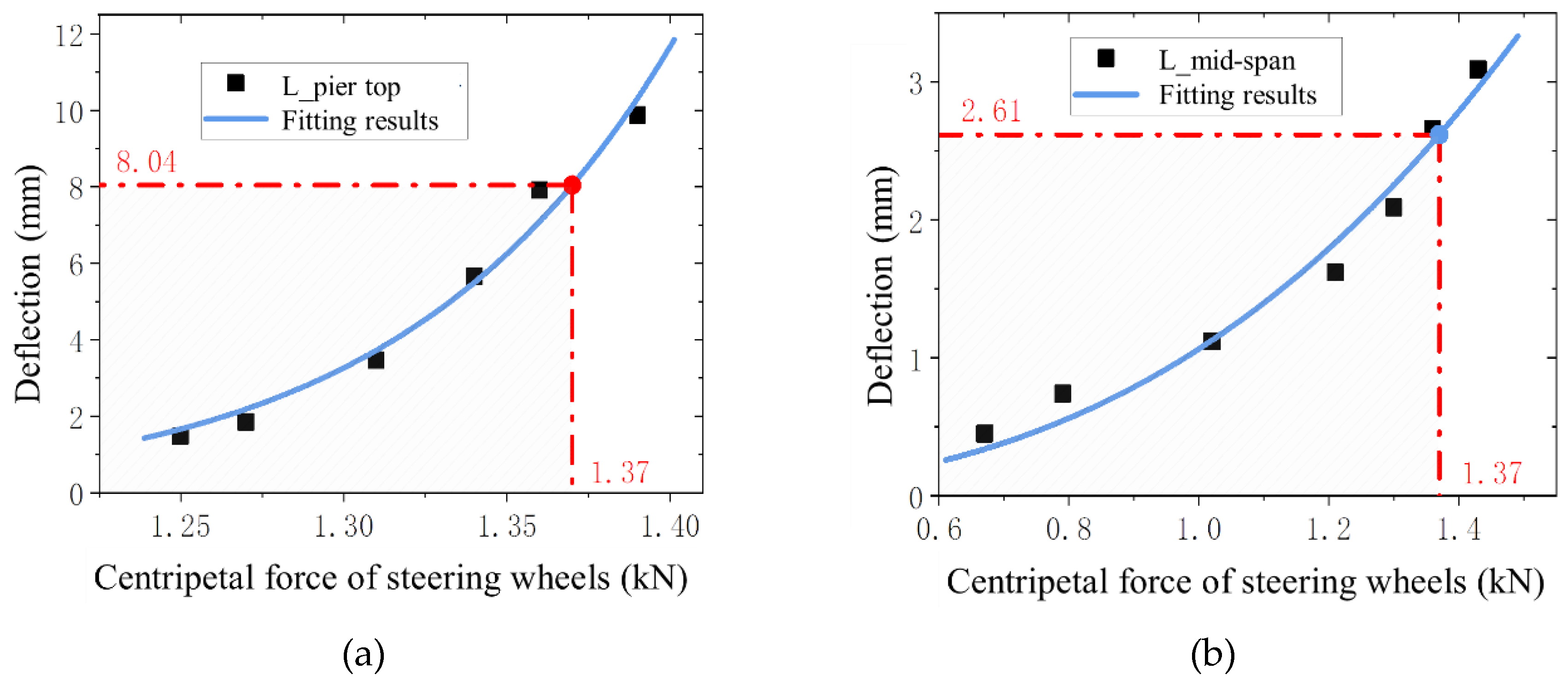

3.3.3. Lateral Wheel Force Perspective

From the data obtained in the previous section, respectively, the vertical force of the guide wheel and the transverse displacement of the top of the pier under the variation of the pier height and it’s fit to the transverse deflection under the variation of the transverse stiffness are shown in

Figure 13.

The fitting coefficient

R2 of

Figure 13a is 0.98, and the fitting coefficient

R2 of

Figure 13b is 0.96. According to the fitting function of the selected point interpolation, when the vertical force of the guiding wheel is the limit value of 1.37 kN, the transverse horizontal displacement of the top of the pier takes the value of 8.04 mm, and the transverse deflection in the span takes the value of 2.61 mm. According to the formula of the transverse lateral deflection-span ratio calculation, it can be obtained that the limit of the lateral deflection-span ratio is about L/3900.

3.3.4. Limits of the Lateral Displacement and Lateral Deflection‒Span Ratio of the Pier Top

In the foregoing text, the interpolation method was used to select the values of the fitting function, and the corresponding data are summarized in

Table 2.

On the basis of the data in

Table 2 and considering partial safety, the minimum value of 8.04 mm is used for the lateral displacement of the pier top, and the minimum value of

L/4200 is taken as the lateral stiffness limit for the lateral deflection–span ratio limit.

Author Contributions

Methodology, H.Z., P.W., and S.W.; software and formal analysis, P.W. and S.W; data curation, P.W., J.J., and S.W.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z. and S.W.; writing—review and editing, P.W. and F.G.; supervision and project administration, F.G.; engineering application, Q.L., J.J., C.F., and Q.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

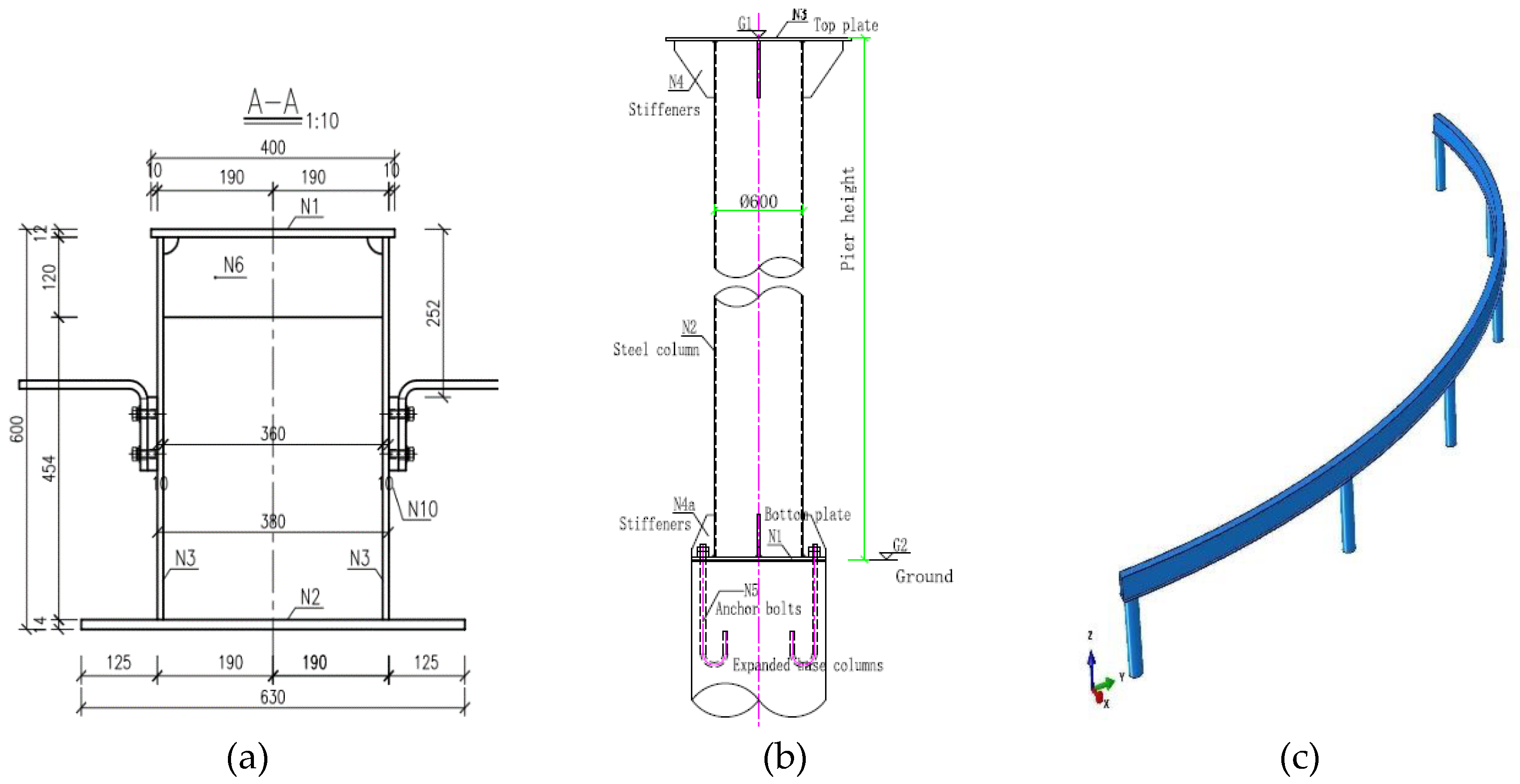

Figure 1.

Representative design diagrams and numerical model of monorail substructures. (a) Cross-section of the track beam; (b) design diagram of the pier; (c) finite element model.

Figure 1.

Representative design diagrams and numerical model of monorail substructures. (a) Cross-section of the track beam; (b) design diagram of the pier; (c) finite element model.

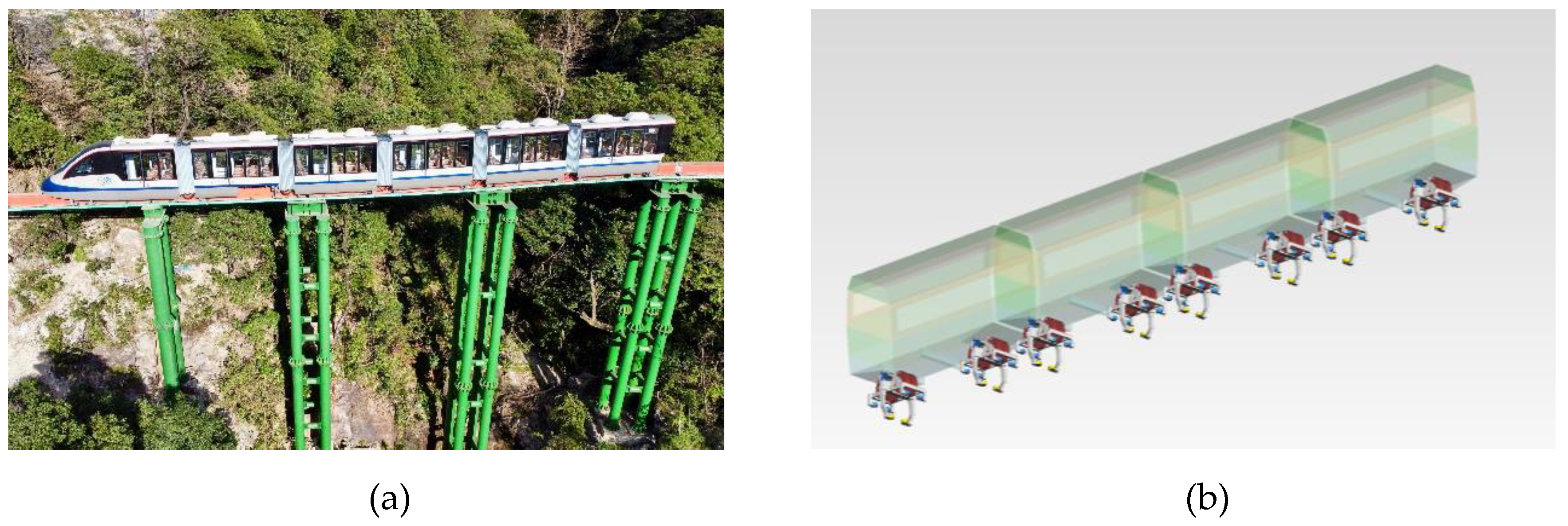

Figure 2.

Onsite monorail train and its MBD model (a) A train in the Dajueshan project; (b) MBD model.

Figure 2.

Onsite monorail train and its MBD model (a) A train in the Dajueshan project; (b) MBD model.

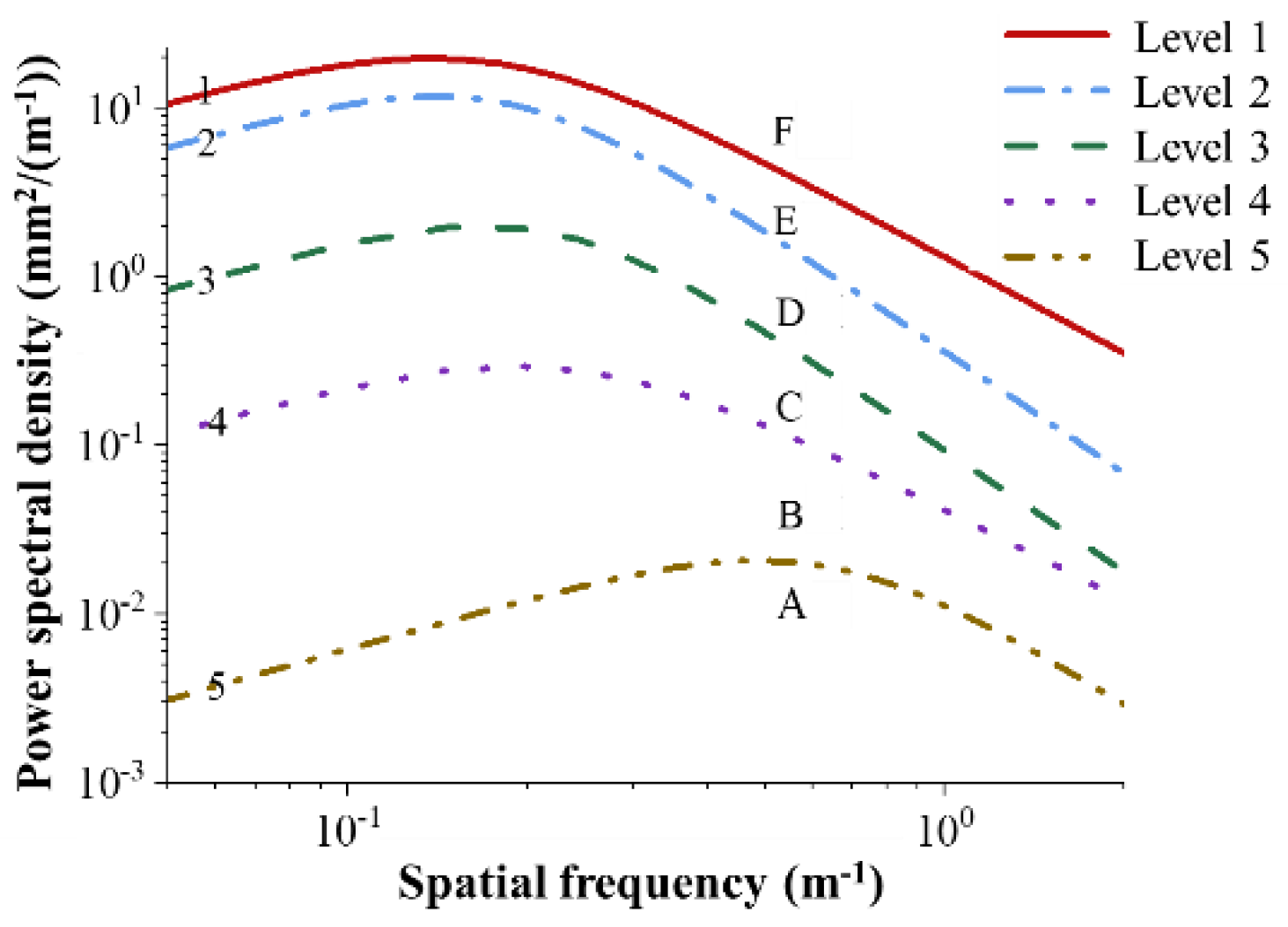

Figure 3.

Integrating different level track irregularities.

Figure 3.

Integrating different level track irregularities.

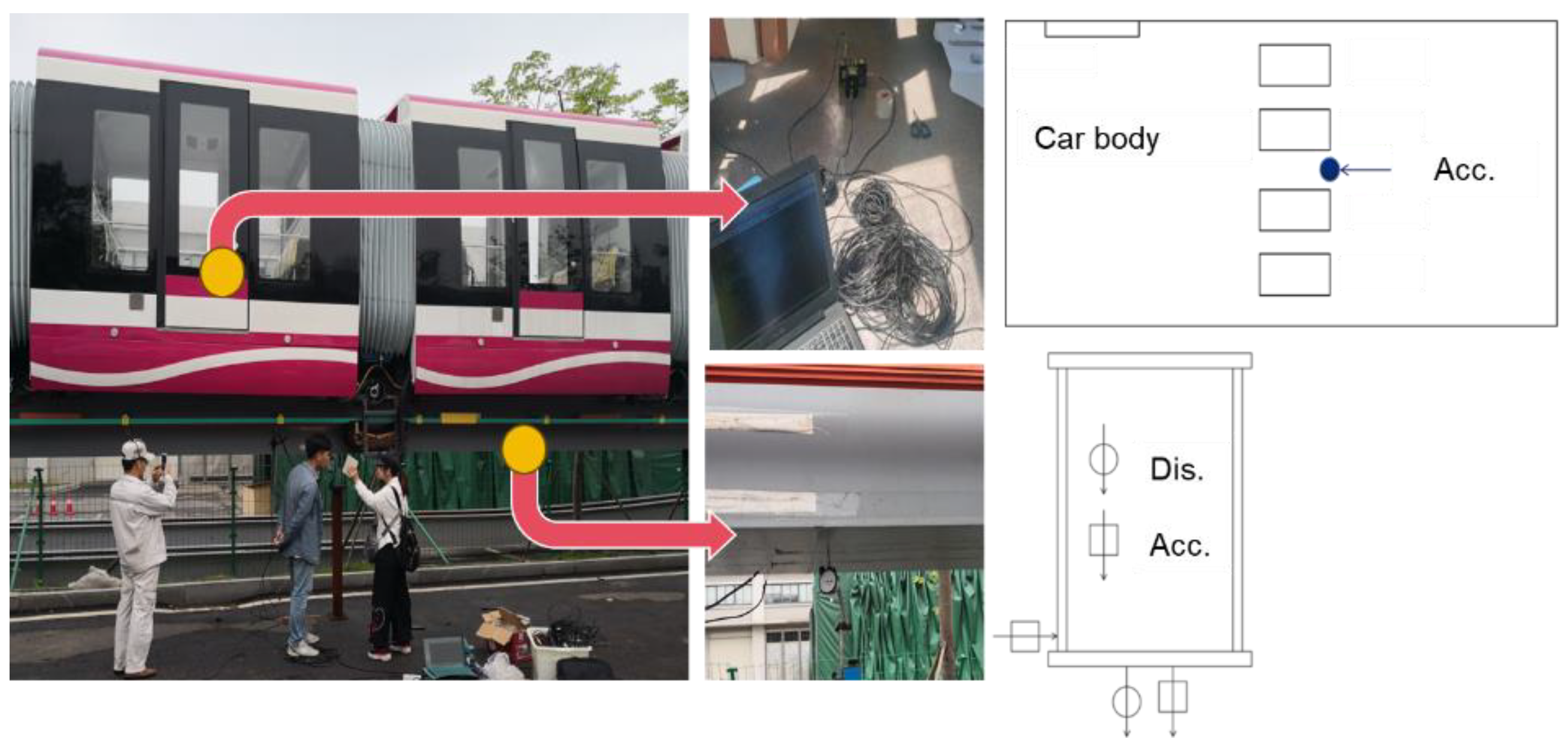

Figure 4.

Layout diagram of the measuring points. For the car body, vehicle accelerations (Acc.) were tested; for the track beam, vertical displacement (Dis.), vertical and lateral Acc. were tested.

Figure 4.

Layout diagram of the measuring points. For the car body, vehicle accelerations (Acc.) were tested; for the track beam, vertical displacement (Dis.), vertical and lateral Acc. were tested.

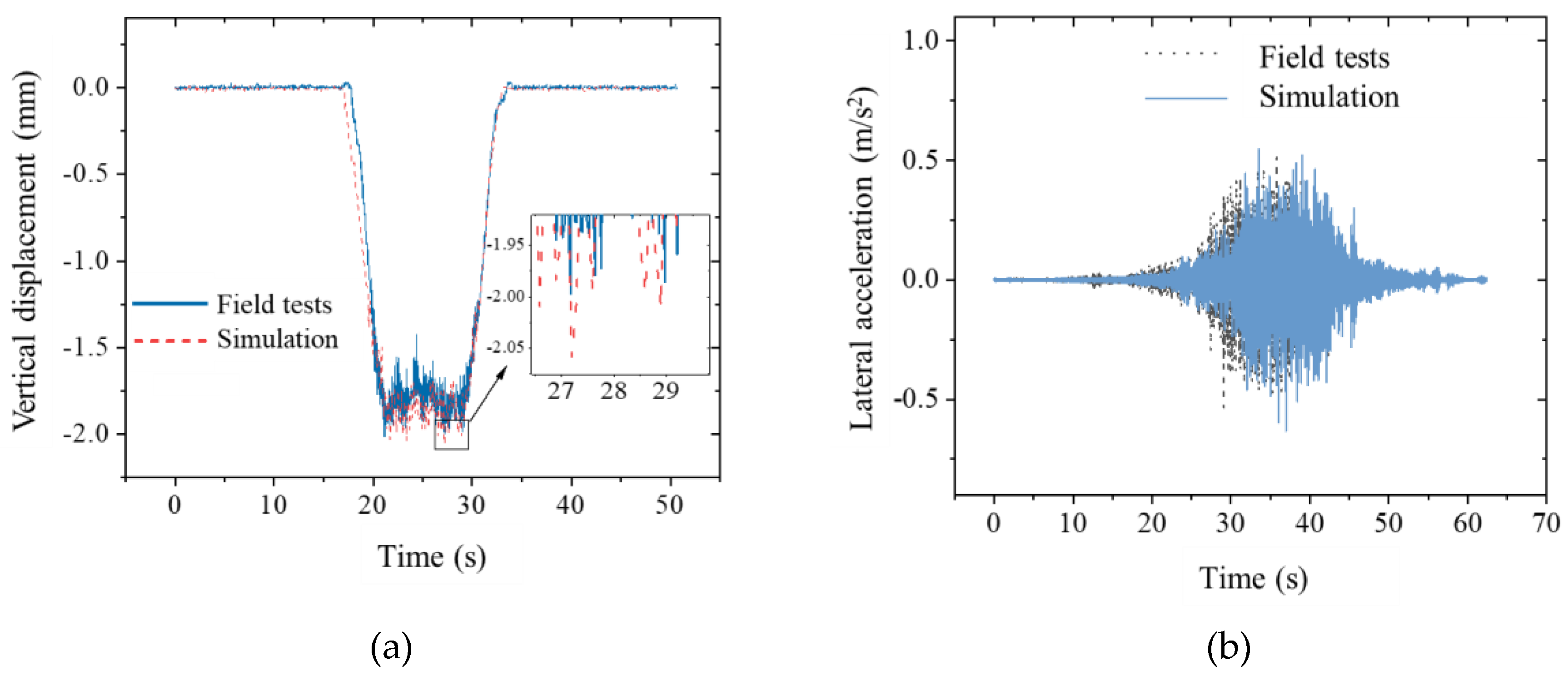

Figure 5.

Comparison of tested and simulation results at the mid-span of a track beam. (a) Vertical displacement; (b) Lateral acceleration.

Figure 5.

Comparison of tested and simulation results at the mid-span of a track beam. (a) Vertical displacement; (b) Lateral acceleration.

Figure 6.

Response results corresponding to different vehicle speeds. (a) Displacement and acceleration response (b) centripetal force and the calculated riding comfort index. Note V and L denote vertical and lateral, respectively.

Figure 6.

Response results corresponding to different vehicle speeds. (a) Displacement and acceleration response (b) centripetal force and the calculated riding comfort index. Note V and L denote vertical and lateral, respectively.

Figure 7.

Results under various loading conditions and train speed: (a) Deflection of bridge components; (b) accelerations (c); centripetal force and the calculated riding comfort index. Note 1, 2, and 3 denote the loading conditions; B and C denote bridge and car body, respectively; and Ste and Sta denote steering and stabilizing wheels, respectively.

Figure 7.

Results under various loading conditions and train speed: (a) Deflection of bridge components; (b) accelerations (c); centripetal force and the calculated riding comfort index. Note 1, 2, and 3 denote the loading conditions; B and C denote bridge and car body, respectively; and Ste and Sta denote steering and stabilizing wheels, respectively.

Figure 8.

Results under various pier height: (a) Displacement and acceleration response (b) centripetal force and the calculated riding comfort index.

Figure 8.

Results under various pier height: (a) Displacement and acceleration response (b) centripetal force and the calculated riding comfort index.

Figure 9.

Response results corresponding to different reduction factor. (a) Displacement and acceleration responses (b) centripetal force, riding comfort index, and wheel unloading rate.

Figure 9.

Response results corresponding to different reduction factor. (a) Displacement and acceleration responses (b) centripetal force, riding comfort index, and wheel unloading rate.

Figure 10.

Results of sensitivity indexes: (a) First-order level (b) Total level. Note, X1 represents the vehicle lateral acceleration, X2 represents the lateral displacement at the mid-span, X3 represents the lateral acceleration at the mid-span, and X4 represents the lateral displacement at the pier top.

Figure 10.

Results of sensitivity indexes: (a) First-order level (b) Total level. Note, X1 represents the vehicle lateral acceleration, X2 represents the lateral displacement at the mid-span, X3 represents the lateral acceleration at the mid-span, and X4 represents the lateral displacement at the pier top.

Figure 11.

Fitting results of lateral deflection versus lateral acceleration: (a) Deflection at the pier top (b) deflection at the mid-span.

Figure 11.

Fitting results of lateral deflection versus lateral acceleration: (a) Deflection at the pier top (b) deflection at the mid-span.

Figure 12.

Fitting results of lateral riding comfort index: (a) lateral displacement at the pier top (b) lateral displacement at the mid-span.

Figure 12.

Fitting results of lateral riding comfort index: (a) lateral displacement at the pier top (b) lateral displacement at the mid-span.

Figure 13.

Fitting results of wheel centripetal force: (a) lateral displacement at the pier top (b) lateral displacement at the mid-span.

Figure 13.

Fitting results of wheel centripetal force: (a) lateral displacement at the pier top (b) lateral displacement at the mid-span.

Table 1.

Aerodynamic coefficients of vehicles and bridges.

Table 1.

Aerodynamic coefficients of vehicles and bridges.

| Type |

FD |

FL |

FM |

| Vehicle |

1.53 |

0.68 |

-0.03 |

| Bridge |

1.12 |

-0.15 |

-0.04 |

Table 2.

Summary of the lateral deflection and deflection-span ratio limits at the pier top.

Table 2.

Summary of the lateral deflection and deflection-span ratio limits at the pier top.

| Judging criteria |

Lateral Acc. |

Lateral riding comfort |

Wheel lateral force limit |

| Lateral deflection at the pier top (mm) |

8.56 |

9.96 |

8.04 |

| Lateral deflection-span ratio |

L/3600 |

L/4200 |

L/3900 |

Table 3.

Comparison of the lateral stiffness limits with specifications (non-mandatory for MTTS)

Table 3.

Comparison of the lateral stiffness limits with specifications (non-mandatory for MTTS)

| Specifications |

GB 50458-2022 |

GB/T 51234-2017 |

MTTS |

| Lateral deflection at the pier top (mm) |

30 |

25 |

8.04 |

| Lateral deflection-span ratio |

L/800 |

L/4000 |

L/4200 |