Submitted:

22 June 2023

Posted:

23 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Multi-body dynamic models

1.2. Simplified model alternatives

1.3. Objectives of numerical study

2. Materials and Methods

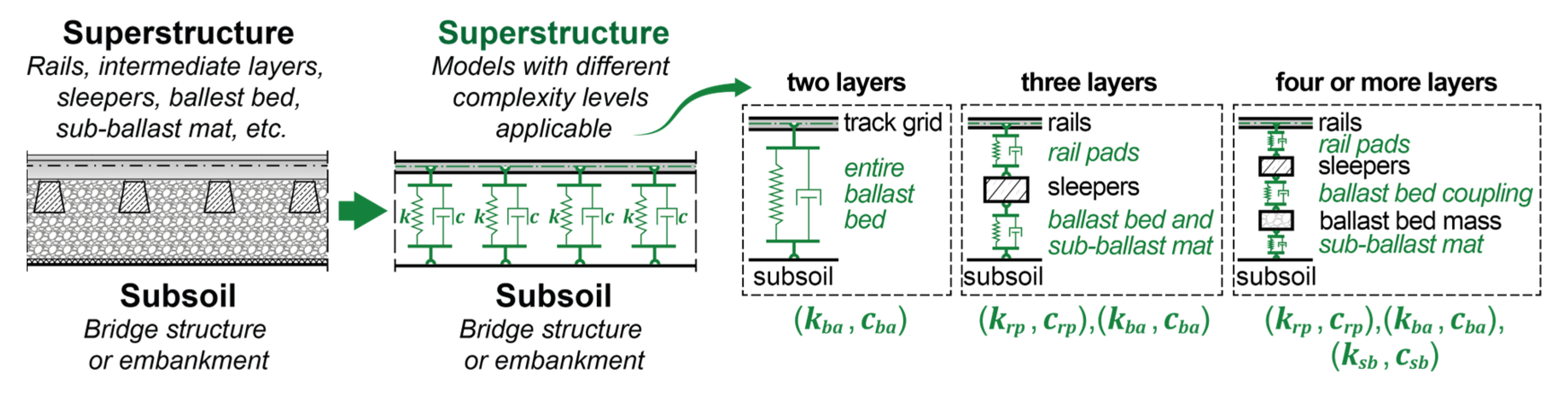

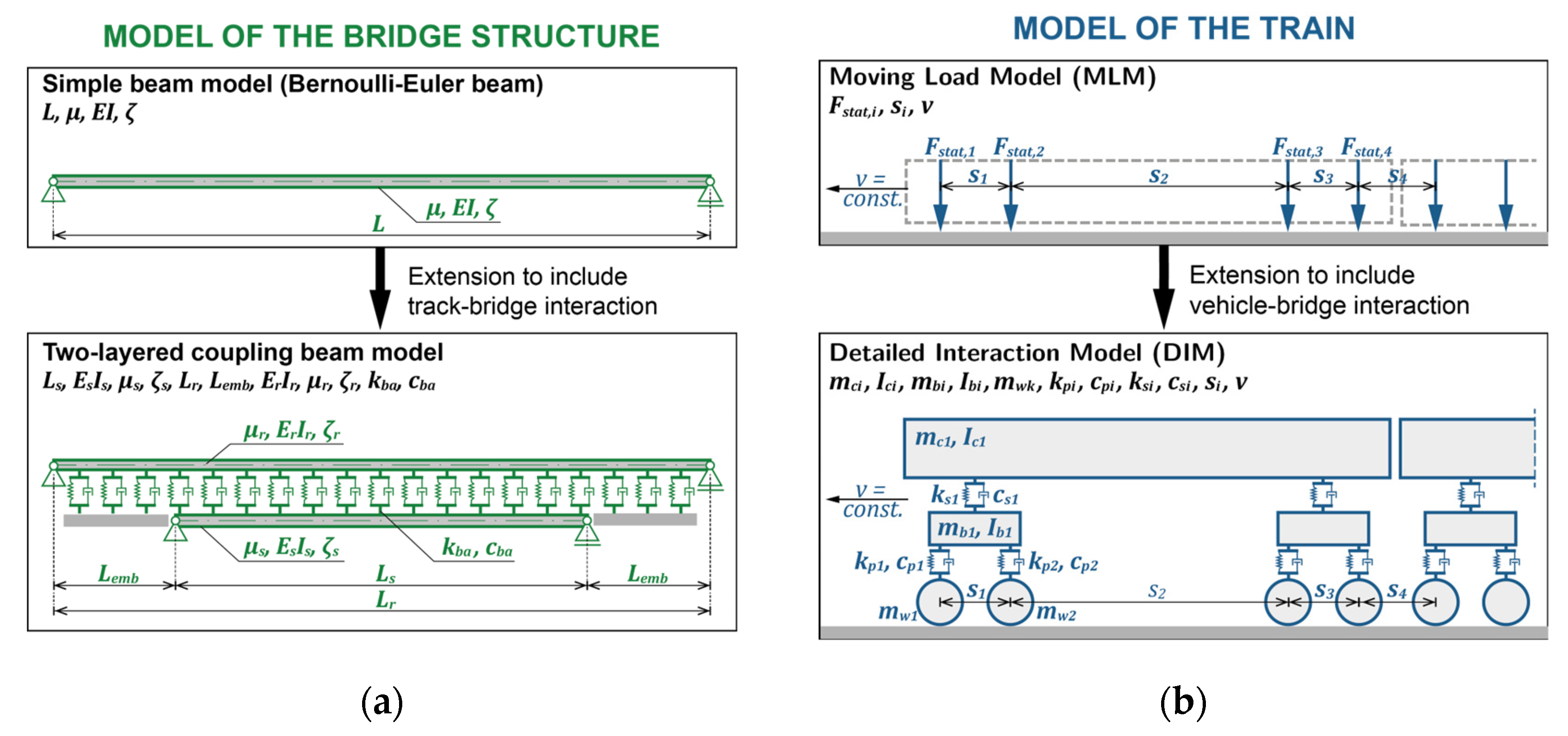

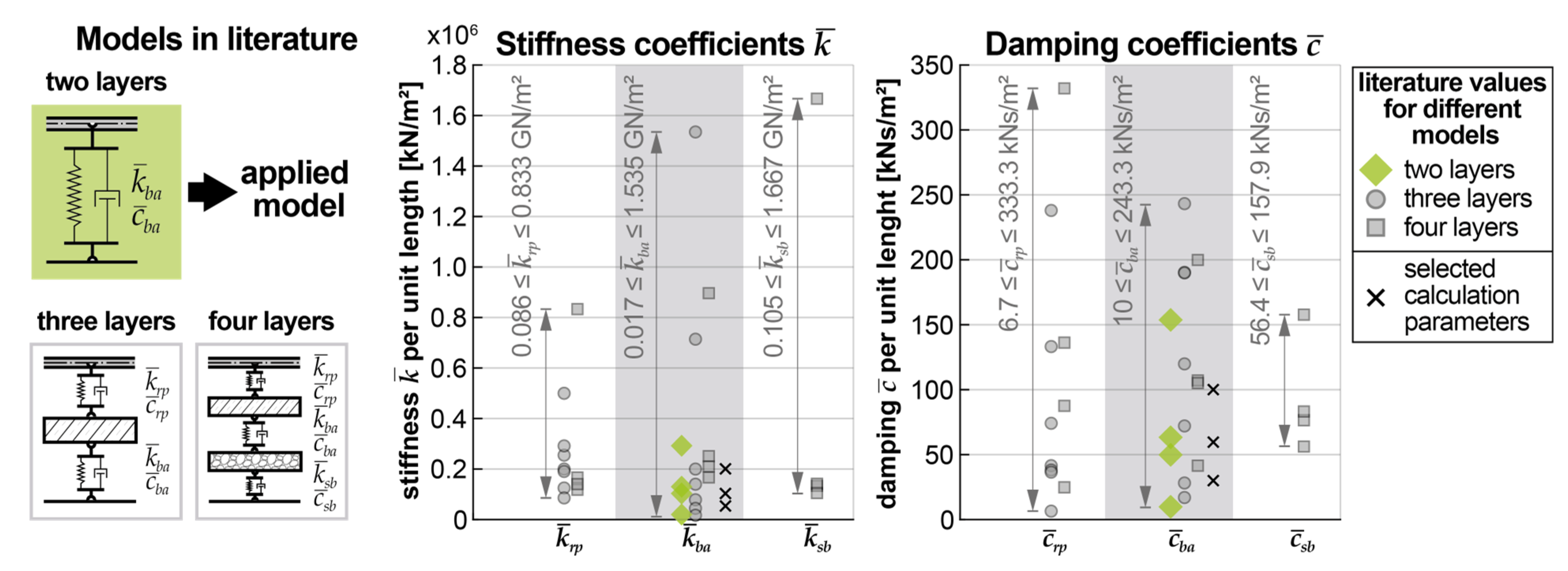

2.1. Mechanical models of the bridge structures

2.2. Mechanical models of the high-speed train

2.3. Parametric analysis – bridge parameters

- Linear stiffness: = 50 000 kN/m2;, = 100 000 kN/m2;, = 200 000 kN/m2;

- Viscous damping: = 30 kNs/m2;, = 60 kNs/m2;, = 100 kNs/m2;

2.4. Parametric analysis – train parameters

2.5. Parametric analysis – calculation and evaluation parameters

- V1-B1: Reference calculations with the MLM (V1) and the Bernoulli-Euler beam (B1) →3 330 parameter combinations

- V2-B1: Calculations with the DIM (V2) and the Bernoulli-Euler beam (B1) – Consideration of vehicle-bridge interaction possible → 3 330 parameter combinations

- V1-B2: Calculations with the MLM (V1) and the coupling beam (B2) – Consideration of track-bridge interaction possible → 16 500 parameter combinations

- V2-B2: Calculations with the DIM (V2) and the coupling beam (B2) – Consideration of vehicle-bridge and track-bridge interaction possible → 3 330 parameter combinations

3. Results

3.1. Investigation of an exemplary bridge structure

3.1.1. Variation of coupling beam parameters

3.1.2. Evaluation of critical train speed

3.2. Investigations on a parametric field of bridges

3.2.1. Acceleration results of reference model

3.2.2. Influence of modeling on critical train speed

3.2.3. Influence of modeling on acceleration peaks

4. Conclusions and outlook

4.1. Statistical analysis of bridge parameters

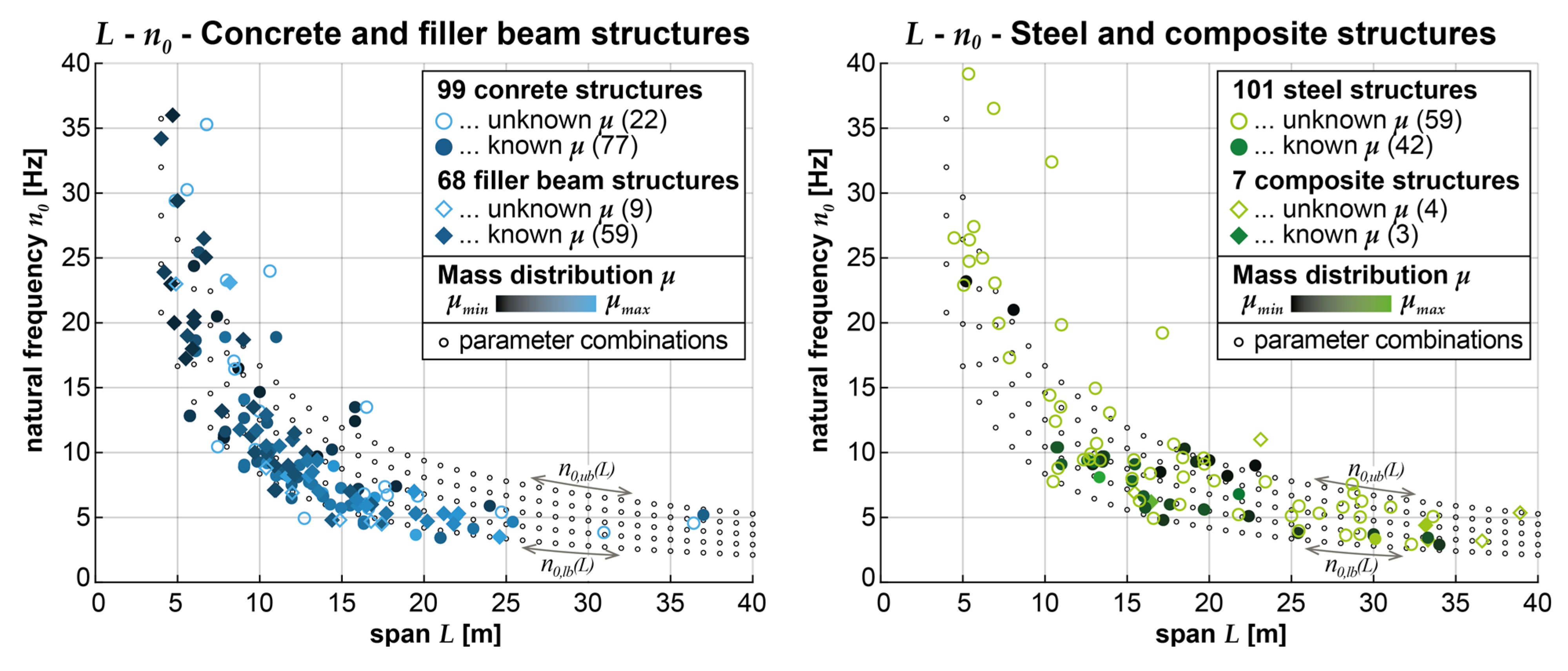

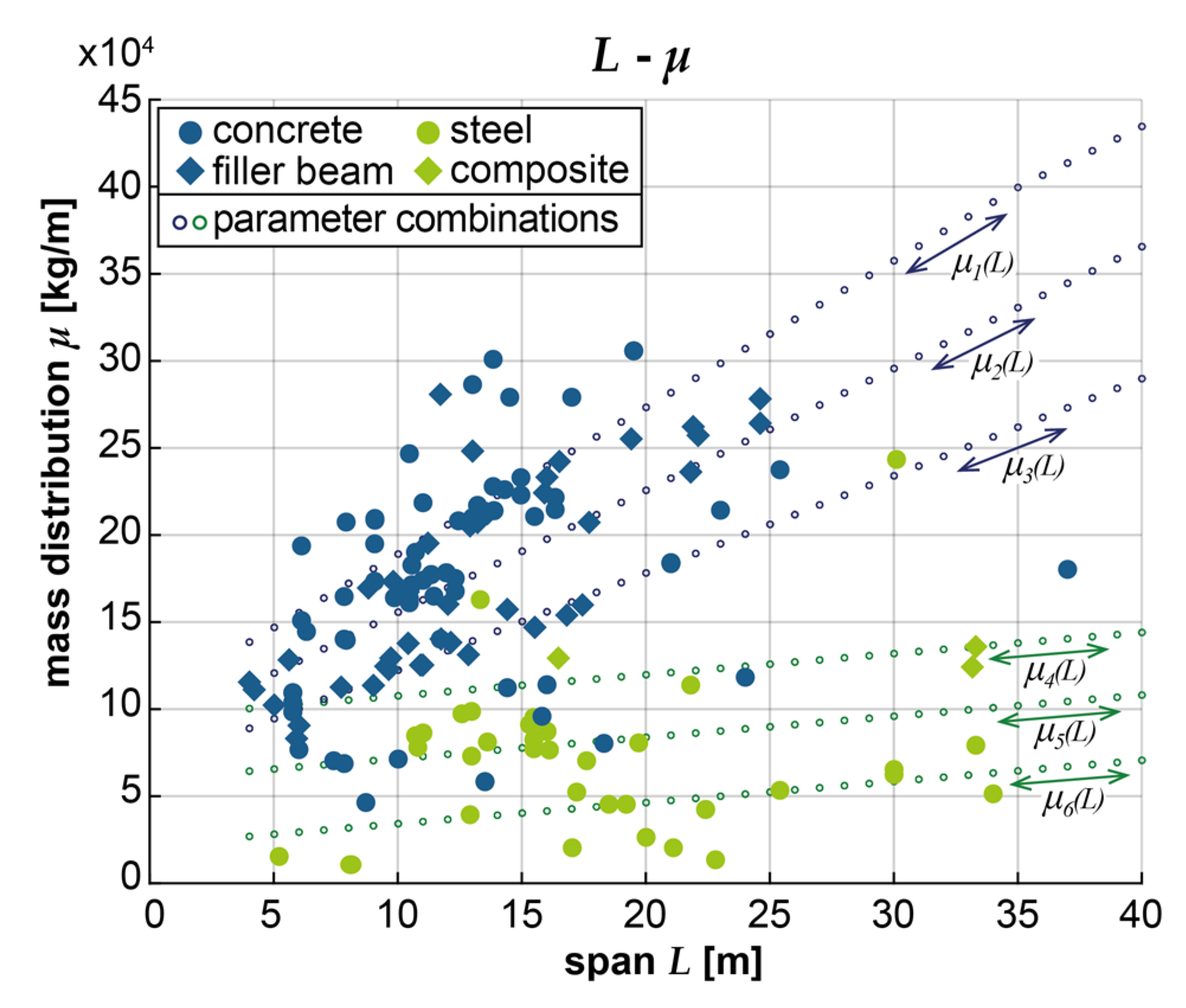

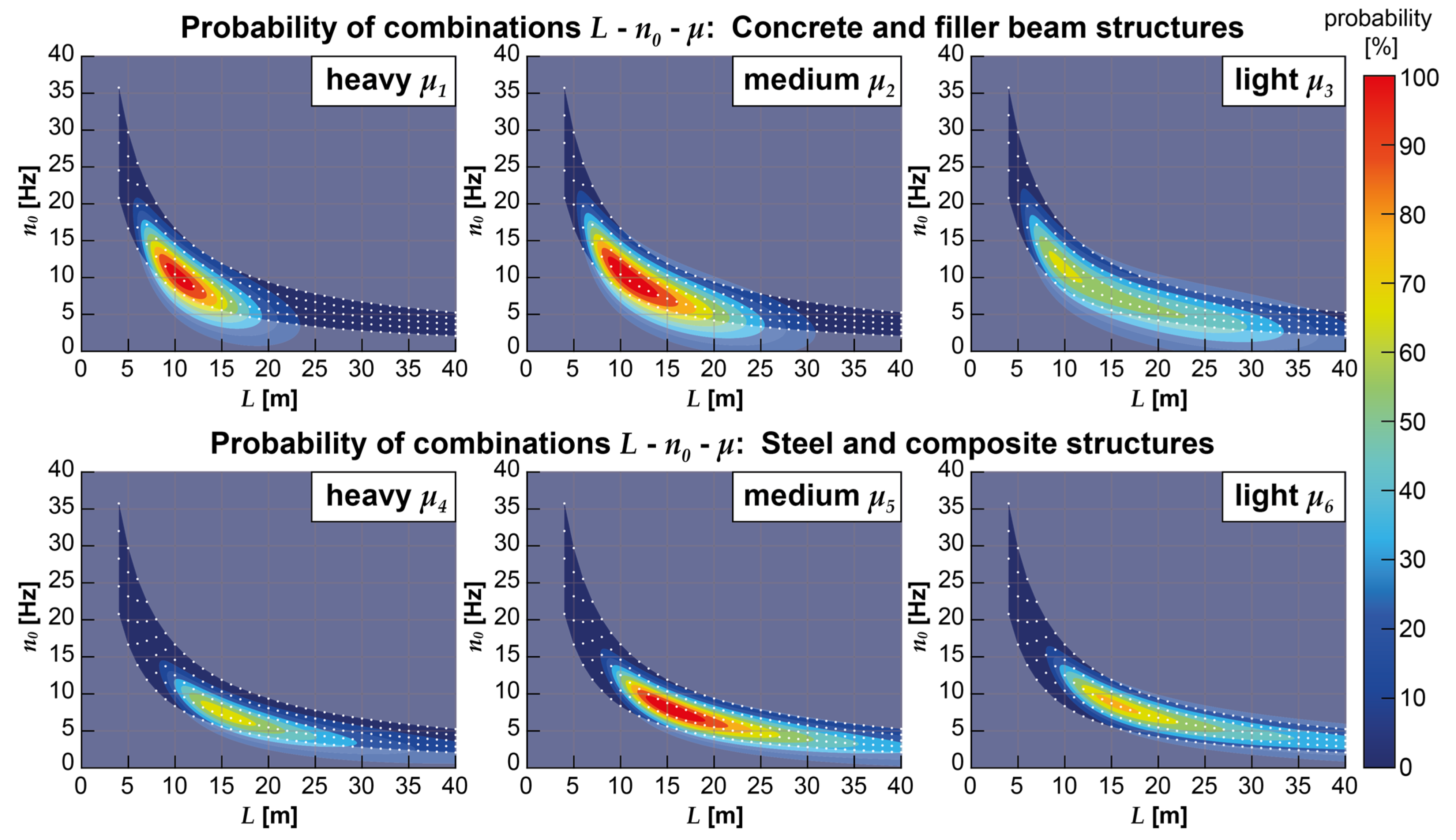

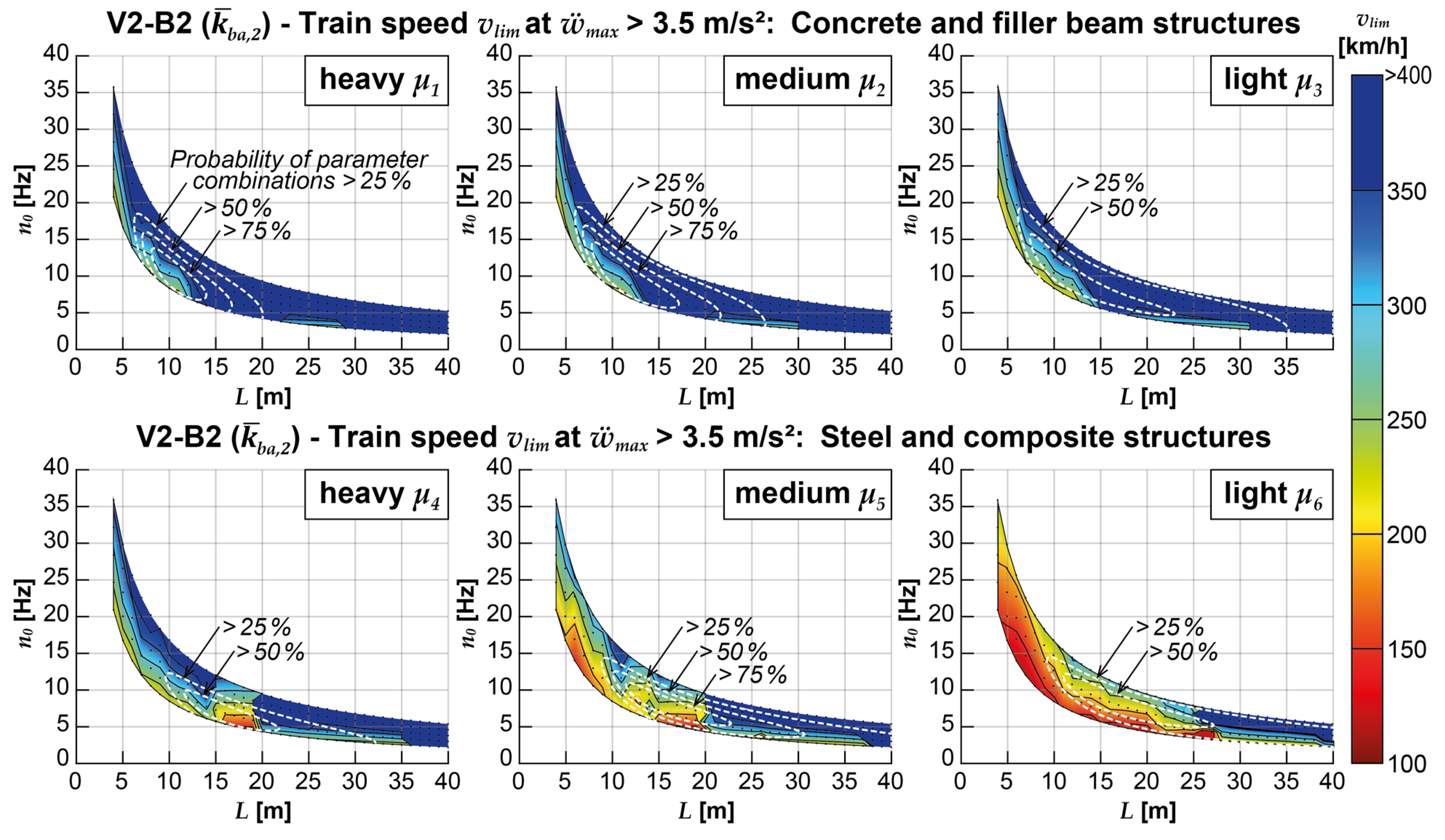

- Based on the available information on existing concrete and filler beam structures, the average span is = 10.65 m, the average mass distribution is = 17.5 t/m, and the average fundamental bending frequency = 10.1 Hz. Parameter combinations with spans ranging from 7 to 23 m and fundamental frequencies from 5 to 17 Hz, particularly for heavy to medium structures (μ1 to μ2), have a probability of occurrence greater than 50%.

- Based on the available information on existing steel and composite structures, the average span is = 15.3 m, the average mass distribution is = 7.5 t/m, and the average fundamental bending frequency = 8.1 Hz. Parameter combinations with spans ranging from 10 to 31 m and fundamental frequencies from 4 to 13 Hz, particularly for structures with medium mass distribution (μ4), have a probability of occurrence greater than 50%.

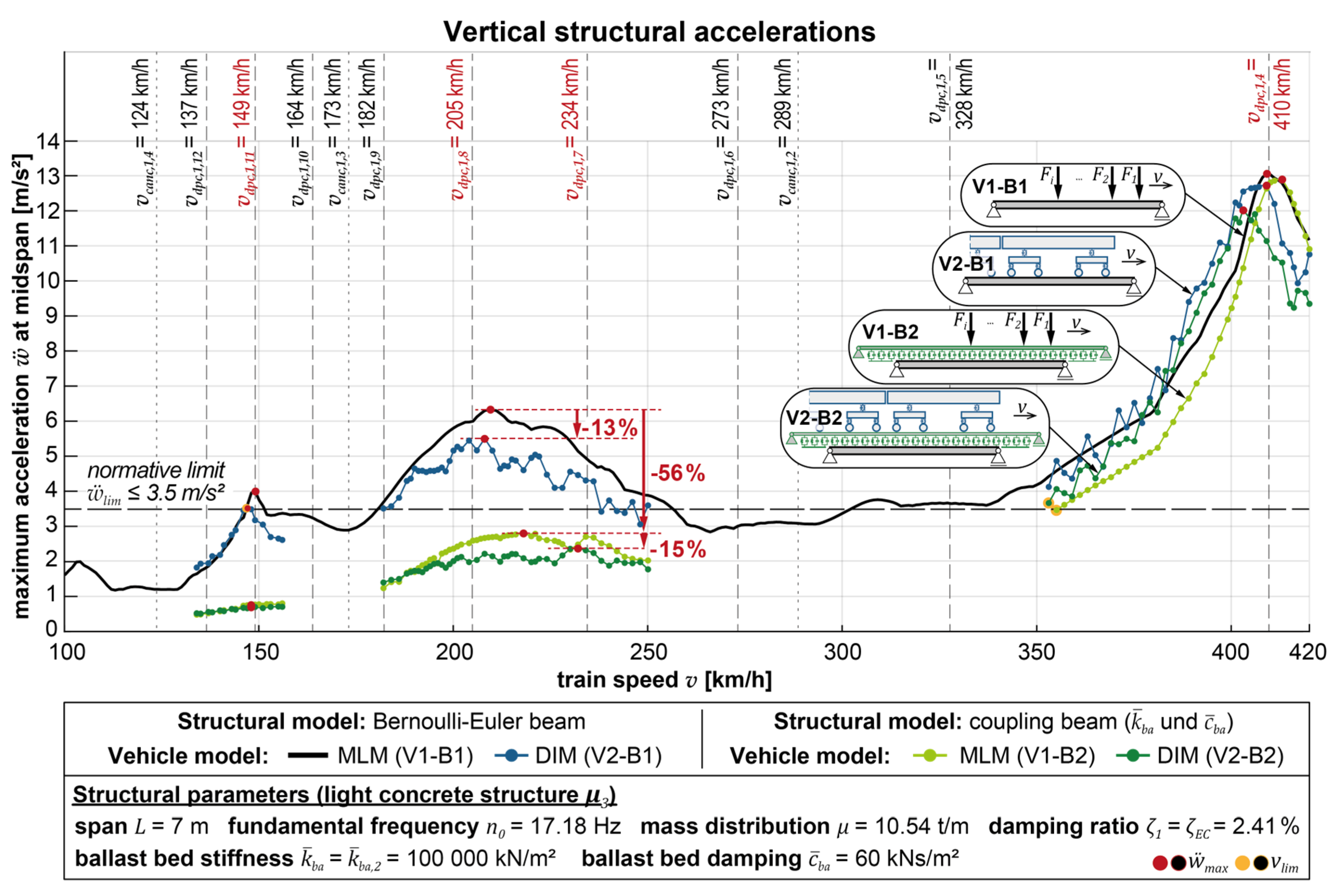

4.2. Evaluation of exemplary bridge structure

- The results of the reference model (V1-B1) generally represent the maximum acceleration values in most cases, which can be reduced to varying degrees by applying one of the other models. It is observed that the lowest accelerations are typically obtained with the most complex model (V2-B2), which considers both the track-bridge and vehicle-bridge interaction. When examining the acceleration peak at the maximum train speed, which occurs within the range of the resonant speed vdpc,1,4 for this particular structure, the maximum reduction can be achieved by employing the DIM of the train (V2-B1 and V2-B2). However, for the acceleration peaks at lower train speeds (at vdpc,1,8 and vdpc,1,11), the application of the coupling beam model (V1-B2 and V2-B2, respectively) has a much more significant influence in reducing the acceleration results.

- When utilizing the multi-body model of the train alone (V2-B1), a shift of the acceleration peaks towards slightly lower train speeds is observed. This can be explained by the increase in the modal mass of the overall system resulting from the consideration of train masses. On the other hand, when solely employing the coupling beam model (V1-B2), the acceleration peaks tend to shift towards somewhat higher train speeds. Furthermore, it was noted that the influence of the coupling beam model leads to more pronounced damping of the acceleration peaks at lower train speeds than at higher speeds. This effect may lead to acceleration peaks at higher train speeds, which were previously overshadowed in the reference model, becoming more significant or decisive (see also Figure 9).

- When combining both model extensions in the V2-B2 model, there appears to be an additive superposition of the computational benefits of both interaction effects. Specifically, the accelerations are reduced to a similar extent by applying the coupling beam model, regardless of the vehicle model used (see also Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6). This implies that the influence of the coupling beam model on reducing accelerations remains consistent regardless of the specific characteristics of the vehicle model.

- When the underlying structural damping ζ is varied (to the same extent in all models), it is observed that the coupling beam model (V1-B2) has a very similar effect on reducing accelerations (see also Figure 8 and Table 4). However, when solely applying the more complex vehicle model (V2-B1) at higher underlying structural accelerations, the achievable reduction is less compared to cases with the normatively lower bound damping (ζ1 = ζEC). In other words, the coupling beam model consistently contributes to reducing accelerations regardless of the damping level. In contrast, the sole application of the more complex vehicle model is less effective in reducing accelerations when the underlying structural accelerations are higher than the normative damping would suggest.

- When varying the applied coefficients of the ballast bed damping while using the coupling beam model, only a marginal deviation in the resulting influence on accelerations is observed (see also Table 6). This indicates that the ballast bed damping does not have a noticeable impact on the influence of the coupling beam model on structural accelerations within the range of variation considered.

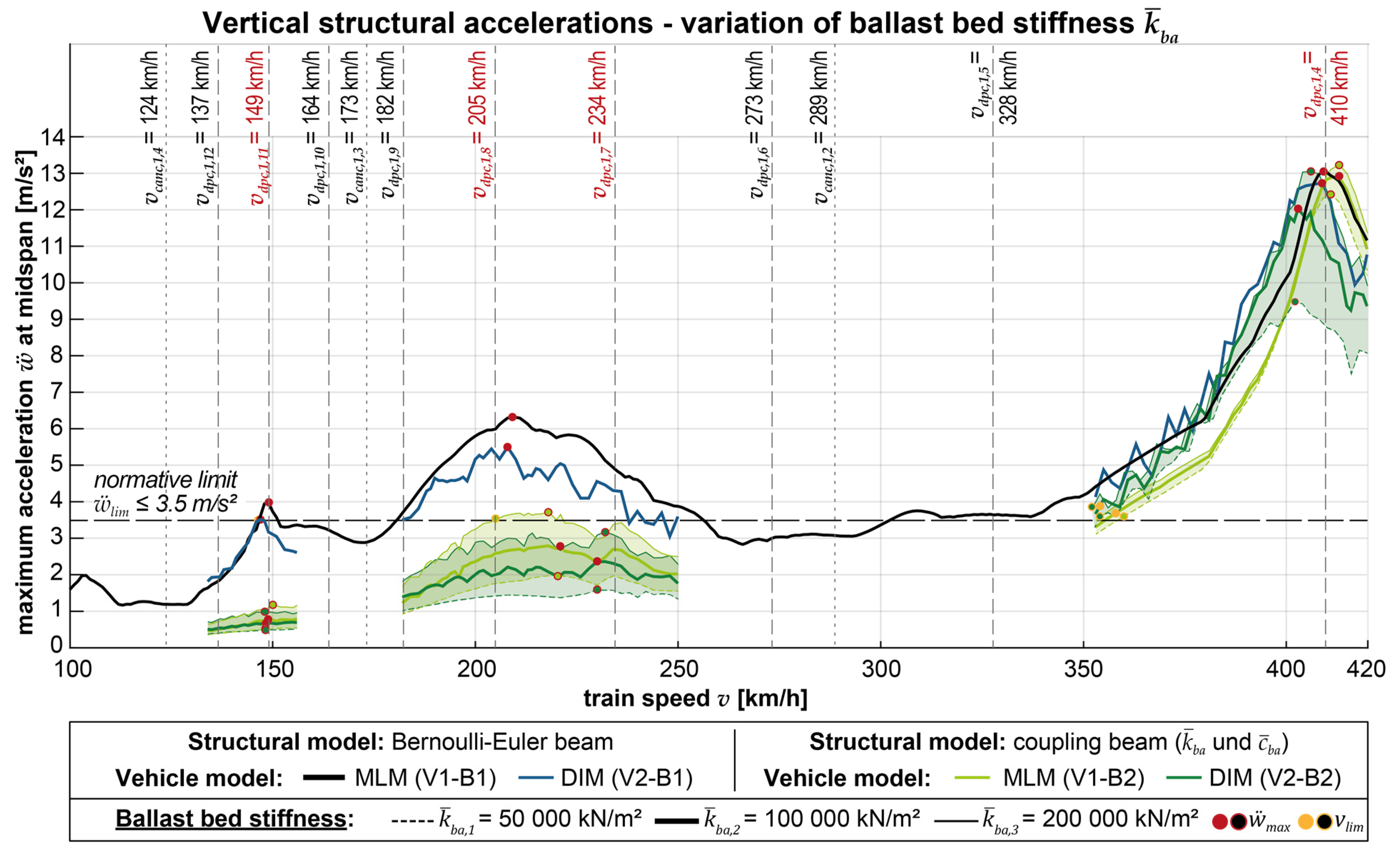

- When the applied spring stiffness of the ballast bed is varied while utilizing the coupling beam model, a significant influence on the computed acceleration reductions is observed (see also Figure 9 and Table 5). Specifically, a lower applied ballast stiffness is associated with a higher reduction in acceleration.

- The evaluation of speeds vlim at which the calculated structural acceleration exceeds the acceleration limit of ẅmax = 3.5 m/s2;, as specified by the standard, reveals a significant potential for the coupling beam model to assess high-speed train crossings as computationally uncritical. For the exemplary structure, regardless of the specific parameters applied to the coupling stiffness , coupling damping , structural damping ζ, and vehicle model (MLM or DIM), the coupling beam model allows for train speeds of over 350 km/h without exceeding the acceleration limit (see also Table 7). In contrast, the reference model predicts a first-time exceedance of the acceleration limit at speeds below 150 km/h. Furthermore, applying the DIM (V2-B1) alone does not significantly influence the limit speed achieved with the reference model (V1-B1) for this specific exemplary structure.

4.3. Evaluation of parametric field of bridges

- Critical accelerations, which substantially exceed the normative limit value, tend to occur more frequently as the structures' mass distribution and span length decrease (see also Figure 10). This is particularly prominent in the case of steel and composite structures, where nearly all parameter combinations with a probability of occurrence exceeding 50% are affected by excessive structural accelerations when the reference model is applied (within the considered speed range).

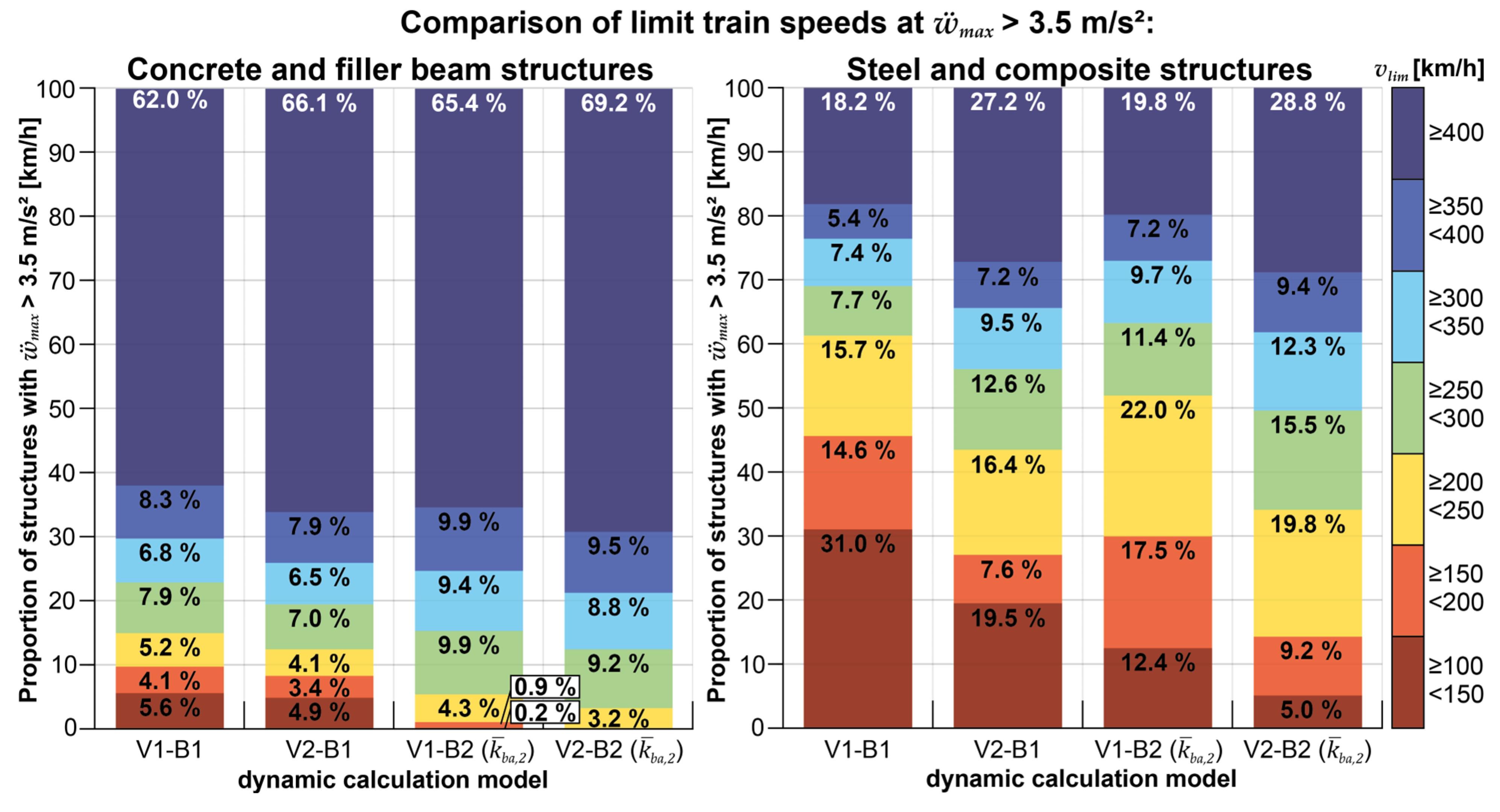

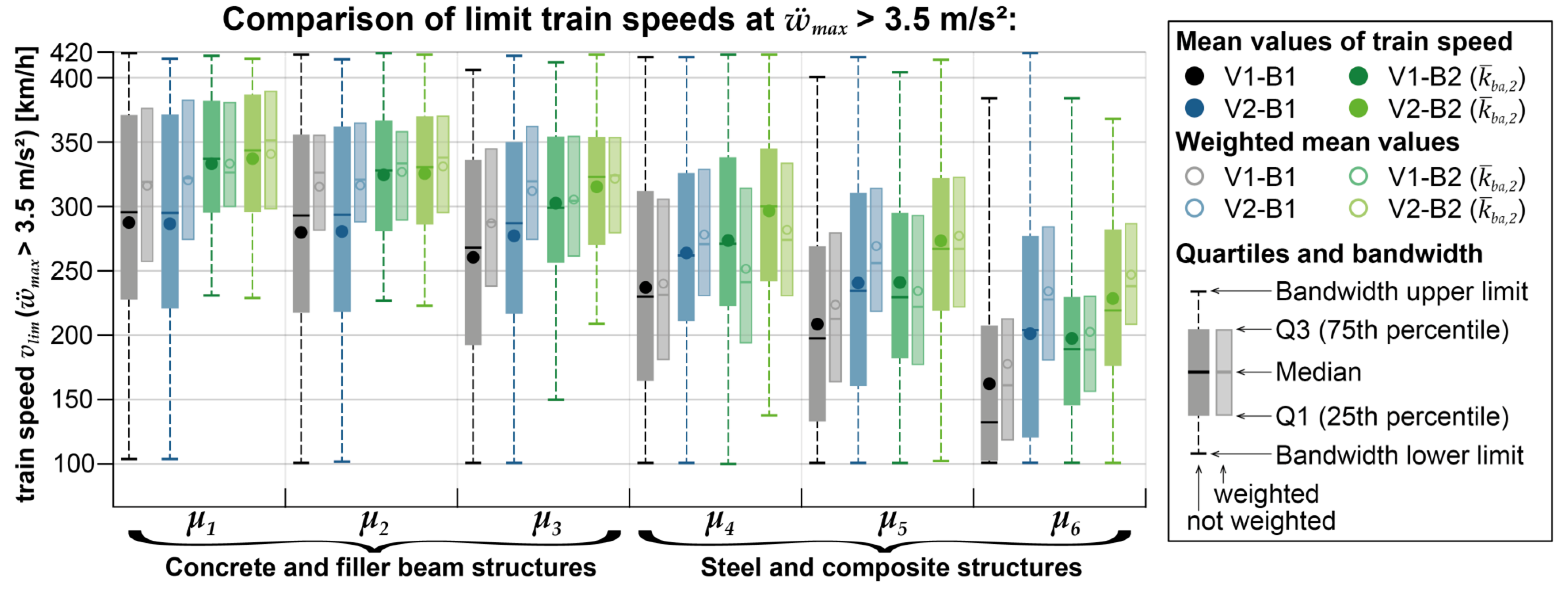

- When considering the critical speed vlim, it is observed that for a relatively large proportion of the concrete and filler beam structures, with a probability of occurrence exceeding 50% (and approximately 62% of all structures), critical accelerations only occur at train crossing speeds above 250 km/h (see also Figure 11 and Figure 15). The median critical speeds range from 268-296 km/h, with a weighted range of 288-326 km/h (see Figure 16). Consequently, these structures can be identified as dynamically uncritical without any issues (at least when considering the Railjet in the standard configuration), even when using the reference model V1-B1. Lower critical speeds are only observed for structures with lower mass distributions, shorter spans, and lower fundamental bending frequencies.

- In contrast, assessing steel and composite structures as dynamic uncritical using the reference model V1-B1 is rarely possible above speeds of 250 km/h (see Figure 11 and Figure 16). Almost all structures experience high maximum accelerations at relatively low speeds. The median critical speeds range from 133-230 km/h, with a weighted range of 161-231 km/h for these structures (see Figure 16).

- Only minor increases in maximum crossing speeds vlim can be achieved for concrete and filler beam structures when utilizing only the more complex multibody model of the train in the V2-B1 model (the median critical speeds range from 287-295 km/h, with a weighted range of 319-322 km/h, see Figure 12 and Figure 16). However, significant increases in maximum crossing speeds are attainable for steel and composite structures (the median critical speeds range from 204-262 km/h, with a weighted range of 228-271 km/h, see Figure 16). Notably, for structures with spans L > 15 m, the V2-B1 model has a highly favorable effect compared to the reference model. Nevertheless, it should be noted that there is a considerable scatter of results, and a relatively high proportion of 19.5% of structures still exhibit problematic accelerations at speeds below 150 km/h (see Figure 15).

- The sole application of the two-layer coupling beam model results in significant increases in critical crossing speeds vlim for all types of structures or mass distributions (see Figure 13, Figure 15, and Figure 16). The median critical speeds for concrete and filler beam structures range from 299-337 km/h, with a weighted range of 304-333 km/h. Similarly, the median critical speeds for steel and composite structures range from 189-271 km/h, with a weighted range of 189-241-km/h. The increment of critical train speed is particularly pronounced for structures with smaller spans L, specifically those below 15 m. When considering parameter combinations with a probability of occurrence exceeding 50%, the favorable impact of the coupling beam model in V1-B2 is similar to or slightly less pronounced than the influence achieved by using the DIM model alone through V2-B1.

- Once again, the beneficial effects of considering the interaction dynamics are further amplified when both the DIM and the coupling beam model are combined in the V2-B2 model (see Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16). As a result, critical accelerations at crossing speeds vlim < 250 km/h are only observed for a smaller proportion of particularly light steel and composite structures. Only 3.2% of all concrete and filler beam structures and 34% of all steel and composite structures experience acceleration peaks below 250 km/h that exceed the normative limit. The median critical speeds vlim for concrete and filler beam structures range from 323-344 km/h, with a weighted range of 324-351 km/h. The median critical speeds for steel and composite structures range from 219-300 km/h, with a weighted range of 238-274 km/h.

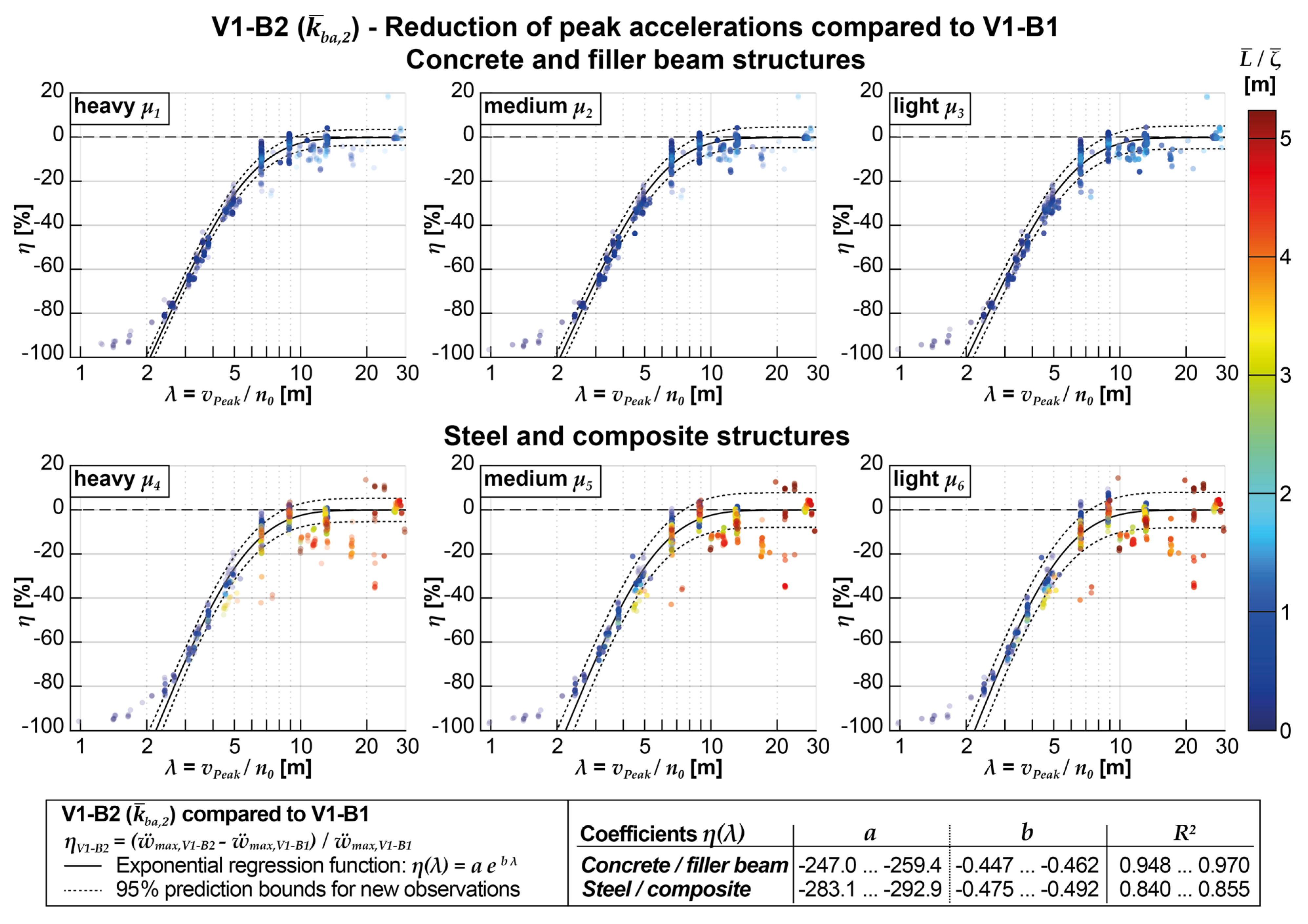

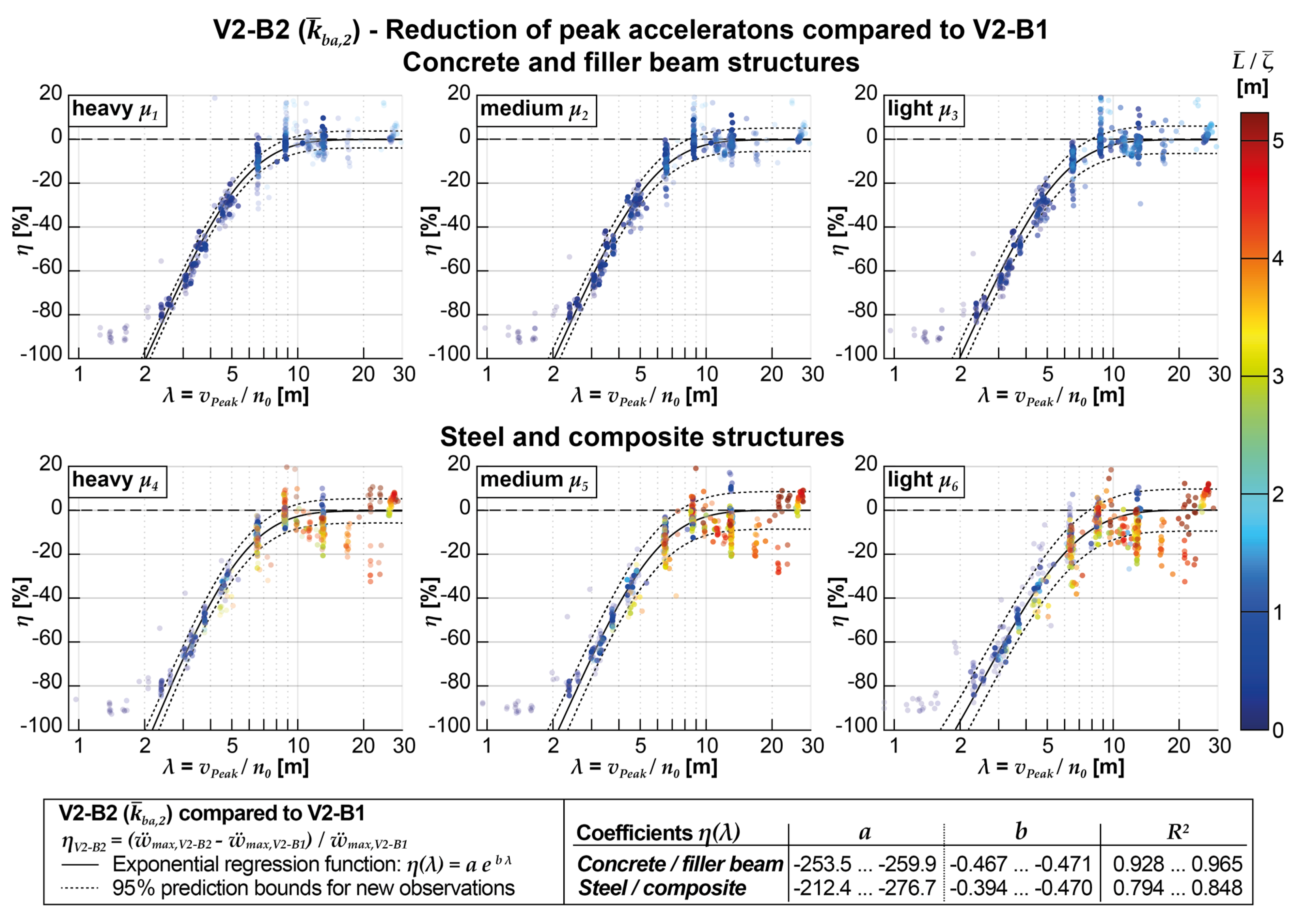

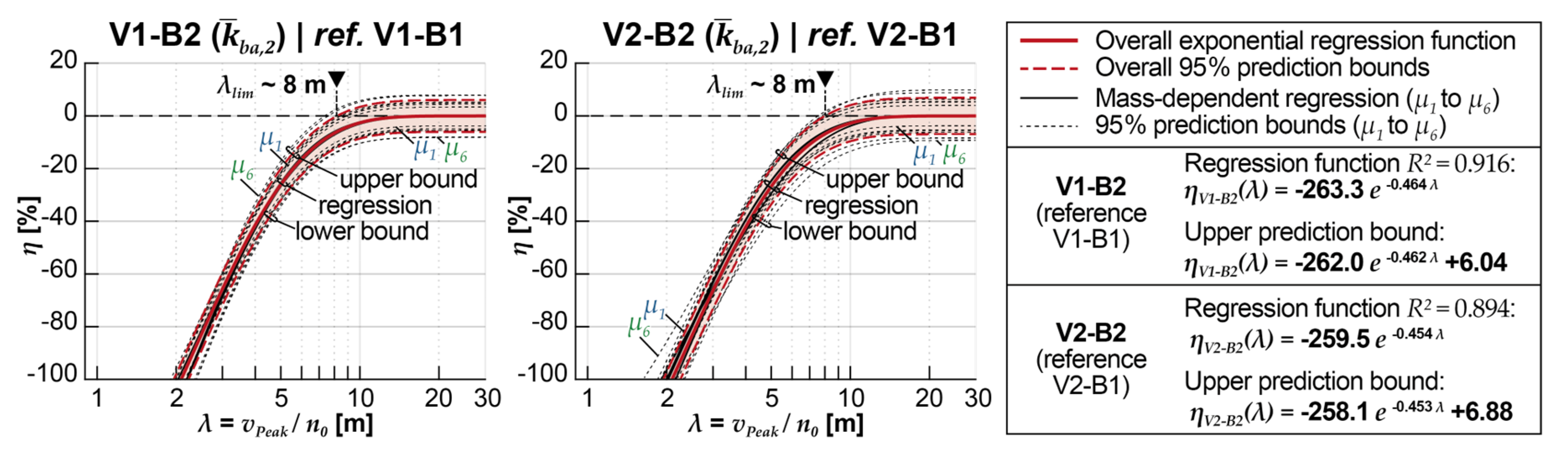

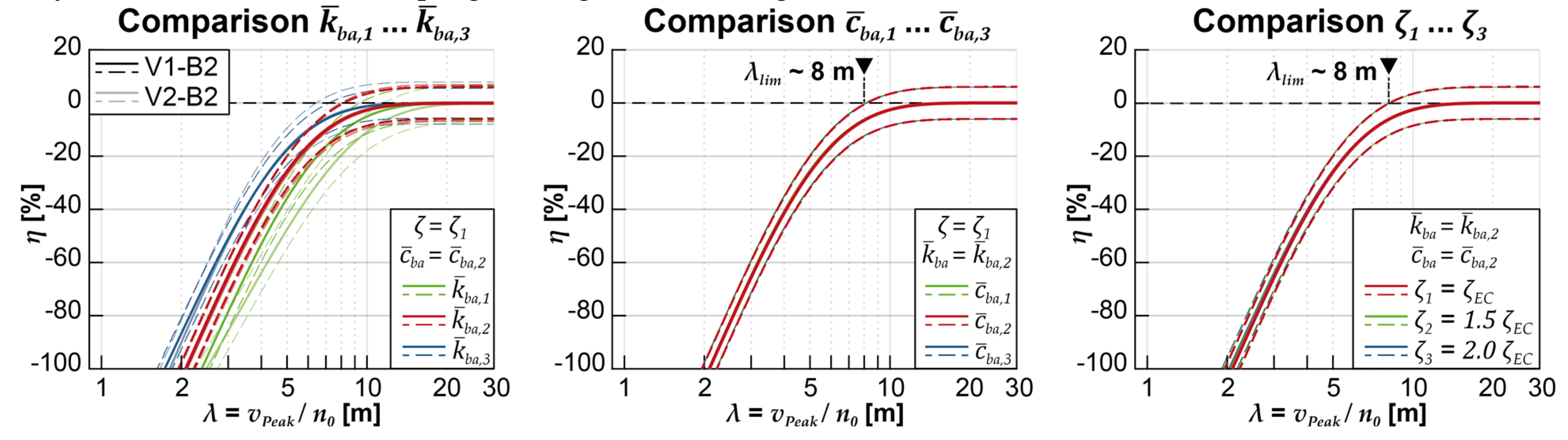

- The influence of the coupling beam model (V1-B2) on the maximum acceleration peaks of the reference model (V1-B1) exhibits a clear dependence on the normalized crossing speed at which it occurs (see Figure 17). Larger reductions in acceleration can be expected as the normalized speeds decrease. This relationship can be accurately described by an exponential (weighted) regression function, which has a high predictive probability. The reduction of acceleration peaks approaches zero at a normalized speed of approximately 13.2 m. At higher normalized speeds, the results tend to scatter significantly; in some cases, even an increase in acceleration peaks can occur. The upper 95% confidence limit for predicting new observations can be considered reliable within a range of normalized speeds from 2.5 to 8 m. With medium coupling stiffness, the reference model's calculated acceleration results can be reduced within this range from 0% to -77%.

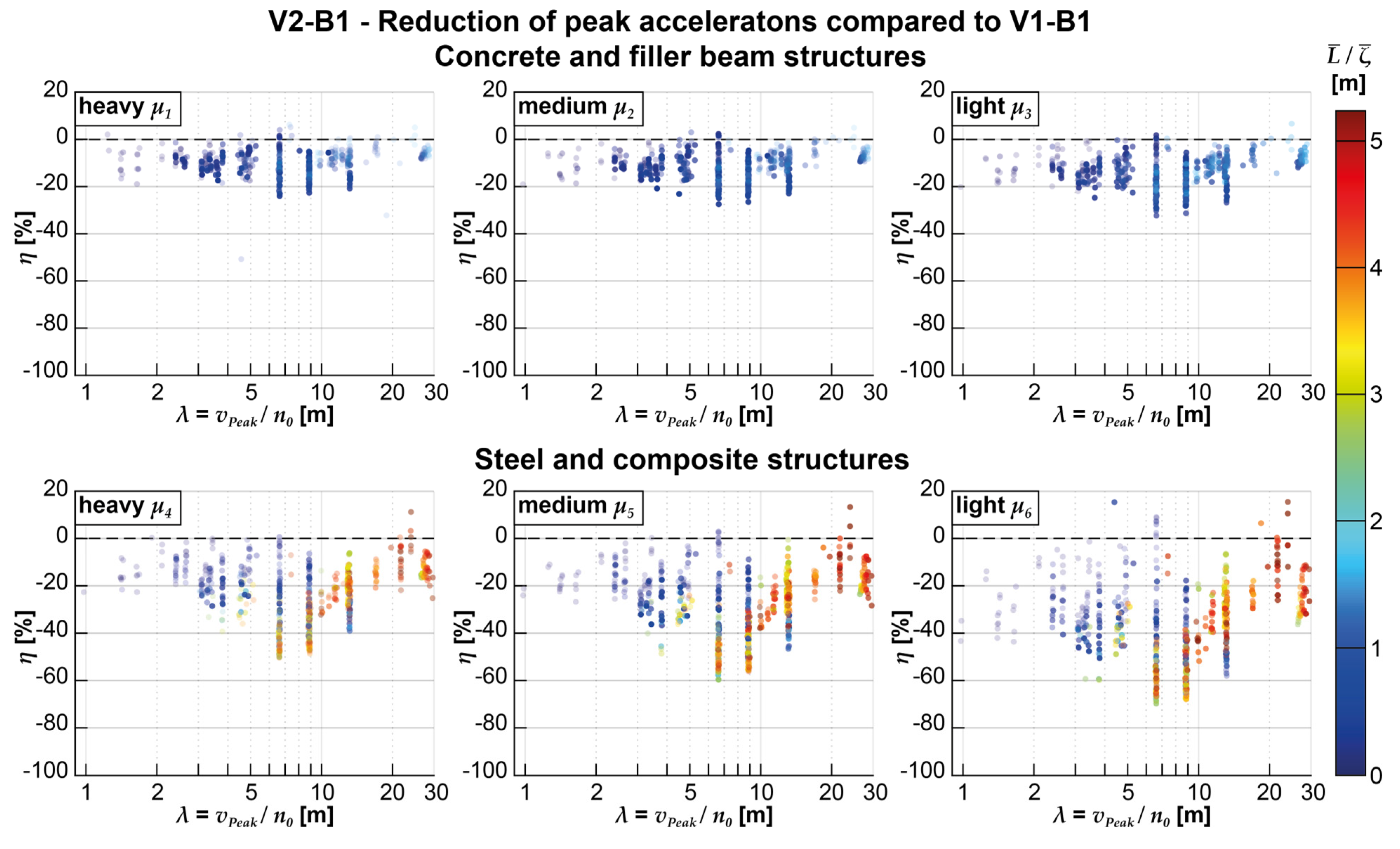

- In contrast to the coupling beam model (V1-B2), the sole application of the vehicle model DIM (V2-B1) does not exhibit a clear dependence between the percentage reduction of the maximum acceleration peaks and the normalized train speed at which they occur (see Figure 18). Therefore, a regression function of the same form cannot be provided. However, it can be observed that low mass distributions and large ratios of span to structural damping tend to favor a stronger influence of the DIM. In general, as the mass occupancy decreases, the magnitude of acceleration reduction increases. In the maximum case, the reduction can reach up to -75%.

- The comparison between the acceleration reduction achieved by using the coupling beam model and the DIM (V2-B2) versus applying the DIM alone (V2-B1) shows similar results to the comparison with the MLM for the vehicle (see Figure 17 and Figure 19). This indicates that the beneficial impact of the coupling beam model is mainly independent of the specific vehicle model used. In other words, regardless of whether the multibody model or the MLM is employed, including the coupling beam model consistently leads to favorable acceleration reductions.

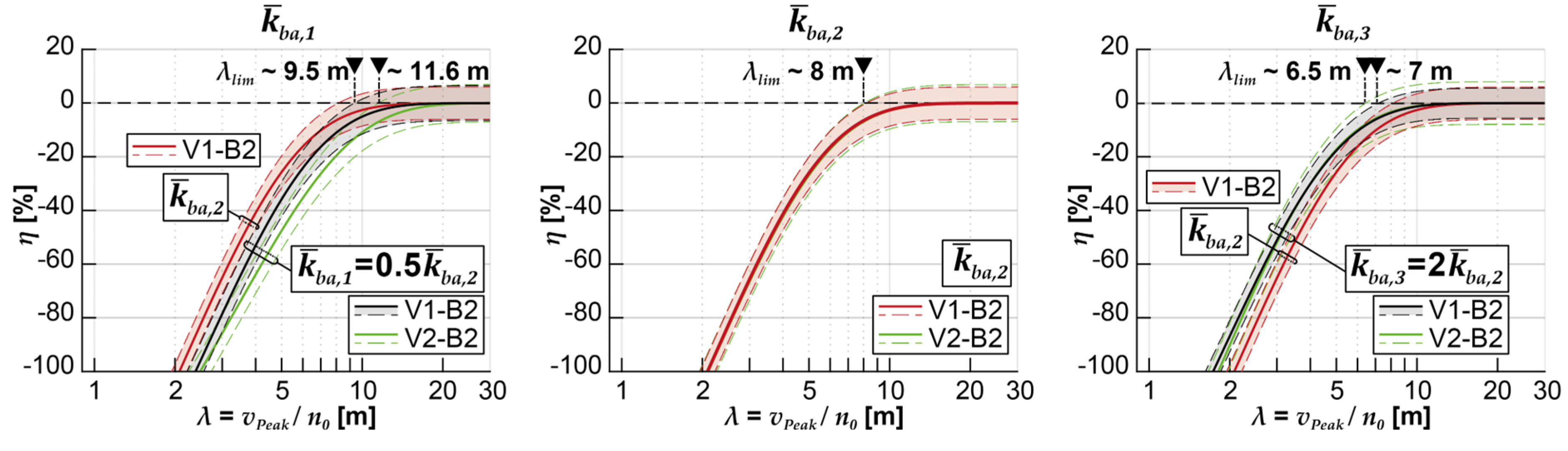

- The achievable acceleration reductions strongly depend on the ballast bed stiffness of the coupling beam model (V1-B2 and V2-B2, see Figure 20, Figure 21 and Figure 22). Lower coupling stiffnesses are associated with more significant reductions in the acceleration peaks of V1-B1. It is worth noting that the regression functions determined for the different vehicle models, DIM (V2-B2) and MLM (V1-B2), may exhibit some deviation, particularly in the case of the lowest coupling stiffness .

- The variation of the ballast bed damping coefficient and structural damping ζ has only marginal effects on the regression functions derived from the results of the entire parameter field, analogously to the exemplary structure (see Figure 22). This observation suggests that a more precise variation of these two parameters may not be necessary for future investigations aiming to describe the influence of coupling beam modeling. It implies that a more generalized approach can be applied, where specific variations of coupling and structural damping can be omitted without significantly compromising the accuracy of the results.

4.4. Final conclusions and outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Vehicle:

- Rail beam:

- Supporting structure beam:

- Interaction vehicle - rail:

- Interaction rail – supporting structure:

References

- EN 1990:2002/A1:2005/AC:2010 Eurocode - Basis of structural design. 2021, CEN European Committee for Standardization.

- Adam, C. and P. Salcher, Dynamic effect of high-speed trains on simple bridge structures. Structural Engineering and Mechanics 2014, 51, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frýba, L., S. Kadecka, and I.C.E.V.L. Books, Dynamics of railway bridges. 1996, London, New York: T. Telford American Society of Civil Engineers, Publications Sales Department.

- Mähr, T.C. , Theoretische und experimentelle Untersuchungen zum dynamischen Verhalten von Eisenbahnbrücken mit Schotteroberbau unter Verkehrslast, Doctoral thesis, Technische Universtität Wien, Vienna, 2009.

- Yang, Y.-B., J. -D. Yau, and L.-C. Hsu, Vibration of simple beams due to trains moving at high speeds. Engineering structures 1997, 19, 936–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-B. , et al., Vehicle-bridge interaction dynamics : with applications to high-speed railways. 2004, River Edge, NJ ; London: World Scientific.

- Yang, Y.B. and C.W. Lin, Vehicle–bridge interaction dynamics and potential applications. Journal of Sound and Vibration 2005, 284, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiterer, M. , et al., Ermittlung der dynamischen Kennwerte von Eisenbahnbrücken unter Anwendung von unterschiedlichen Schwingungsanregungsmethoden. Bauingenieur 2017, 92, 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Reiterer, M. and S.-Z. Bruschetini-Ambro, Dynamik von Eisenbahnbrücken: Diskrepanz zwischen Messung und Berechnung. Bauingenieur 2019, 94, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, T., R. Karoumi, and C. Pacoste, Statistical screening of modelling alternatives in train–bridge interaction systems. Engineering structures 2014, 59, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenech, A. and P. Museros, Influence of the vehicle model on the response of high-speed railway bridges at resonance. Analysis of the Additional Damping Method prescribed by Eurocode 1. Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Structural Dynamics, Eurodyn 2011, 2011, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar]

- Doménech, A., P. Museros, and M. Martínez-Rodrigo, Influence of the vehicle model on the prediction of the maximum bending response of simply-supported bridges under high-speed railway traffic. Engineering Structures 2014, 72, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatz, B. and J. Fink, Influence of the calculation models on the dynamic response of 75 steel, composite and concrete bridges (in German). Stahlbau 2019, 88, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatz, B. and J. Fink, A redesigned approach to the additional damping method in the dynamic analysis of simply supported railway bridges. Engineering Structures 2021, 241. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K., G. De Roeck, and G. Lombaert, The effect of dynamic train-bridge interaction on the bridge response during a train passage. Journal of Sound and Vibration 2009, 325, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantero, D. , et al., Train–track–bridge modelling and review of parameters. Structure and Infrastructure Engineering 2016, 12, 1051–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Rail Research Institute, ERRI D 214/RP9, Rail bridges for speeds >200 km/h; Final Report Part A: Synthesis of the results of D 214 research. Part B: Proposed UIC Leaflet. . 1999.

- Rigueiro, C., C. Rebelo, and L.S. da Silva, Influence of ballast models in the dynamic response of railway viaducts. Journal of Sound and Vibration 2010, 329, 3030–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stollwitzer, A. and J. Fink, Damping parameters of ballasted track on railway bridges - part I: vertical relative displacements in the ballast (in German). Bautechnik 2021, 98, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stollwitzer, A. and J. Fink, Damping parameters of ballasted track on railway bridges - part II: energy dissipation in the ballasted track and related calculation model (in German). Bautechnik 2021, 98, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, C. and J. Oscarsson, Dynamic train/track interaction including state-dependent track properties and flexible vehicle components. Dynamics of Vehicles on Roads and on Tracks 2000, 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kouroussis, G., O. Verlinden, and C. Conti, Influence of some vehicle and track parameters on the environmental vibrations induced by railway traffic. Vehicle System Dynamics 2012, 50, 619–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouroussis, G. and O. Verlinden, Prediction of railway induced ground vibration through multibody and finite element modelling. Mechanical Sciences 2013, 4, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.Y. and B. Zhang, The Influence of Track Stiffness Distribution on Dynamic Behavior of Track Transition. Proceedings of the Asme/Asce/Ieee Joint Rail Conference, 2012; 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Lombaert, G. , et al., The experimental validation of a numerical model for the prediction of railway induced vibrations. Journal of Sound and Vibration 2006, 297, 512–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, P., Z. W. Yu, and F.T.K. Au, Rail-bridge coupling element of unequal lengths for analysing train-track-bridge interaction systems. Applied Mathematical Modelling 2012, 36, 1395–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, P. , Finite element analysis for train–track–bridge interaction system. Archive of Applied Mechanics 2007, 77, 707–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moliner, E. , et al., On the vertical coupling effect of ballasted tracks in multi-span simply-supported railway bridges under operating conditions. Structure and Infrastructure Engineering, 2022.

- Nguyen, K., J. M. Goicolea, and F. Galbadon, Comparison of dynamic effects of high-speed traffic load on ballasted track using a simplified two-dimensional and full three-dimensional model. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers Part F-Journal of Rail and Rapid Transit 2014, 228, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saramago, G. , et al., Experimental Validation of a Double-Deck Track-Bridge System under Railway Traffic. Sustainability 2022, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Young, T.H. and C.Y. Li, Vertical vibration analysis of vehicle/imperfect track systems. Vehicle System Dynamics 2003, 40, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1991-2:2003/AC:2010 Eurocode 1: Actions on structures - Part 2: Traffic loads on bridges. 2010, CEN European Committee for Standardization.

- prEN 1991-2:2021 Eurocode 1: Actions on structures - Part 2: Traffic loads on bridges and other civil engineering works. 2021, CEN European Committee for Standardization.

- RW 08.01.04 Dynamische Berechnung von Eisenbahnbrücken, Anhang 1: Zugdefinitionen. 2022, ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG.

- Museros, P. and E. Alarcón, Influence of the second bending mode on the response of high-speed bridges at resonance. Journal of structural engineering 2005, 131, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-B. and J.-D. Yau, Vehicle-bridge interaction element for dynamic analysis. Journal of Structural Engineering 1997, 123, 1512–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, W. , Computationally efficient simulation program for the dynamic analysis of railway bridges using multi-body models and trigonometric shape functions (in German), Diploma thesis, Technische Universtität Wien, Vienna 2009.

- The Mathworks Inc., MATLAB 2022: Natick, Massachusetts.

- Shampine, L.F. and M.W. Reichelt, The MATLAB ODE Suite. SIAM Journal on Scientific Computing 1997, 18, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Rail Research Institute, ERRI D 214/RP3, Rail bridges for speeds >200 km/h; Recommendations for calculating damping in rail bridge decks. 1999.

- European Rail Research Institute, ERRI D 214/RP8, Rail bridges for speeds >200 km/h; Confirmation of values against experimental data. Part A: Rig tests to investigate ballast behaviour on bridges due to high acceleration levels Confirmation of the acceleration limit for the ballast. Part B: Comparison of calculations and measurements usi. 1999.

- Rauert, T. , et al., On the influence of constructional elements on the dynamic behaviour of filler beam railway bridges (in German). Bautechnik 2010, 87, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatz, B., L. Bettinelli, and J. Fink, Power cars and vehicle-bridge-interaction in the dynamic calculation of railway bridges (in German). Bautechnik 2020, 97, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotz, S. Balakrishnan, and N.L. Johnson, Continuous multivariate distributions, Volume 1: Models and applications. Vol. 1. 2004: John Wiley & Sons.

- Bruckmoser, B. , Investigation of the load-distributing effect of the ballast bed in simulations of railway bridge vibrations (in German). Diploma thesis, Technische Universtität Wien, Vienna 2009.

| concrete and filler beam structures | steel and composite structures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μ1 | μ2 | μ3 | μ4 | μ5 | μ6 | |

| a | 0.843 | 0.7002 | 0.5584 | 0.1214 | 0.1214 | 0.1214 |

| b | 10.45 | 8.539 | 6.627 | 9.5174 | 5.918 | 2.1691 |

| Locomotive (loc) | Passenger car (pc) | |

|---|---|---|

| Axle load Fstat [kN] | 215.6 | 148.4 |

| Car body mass mc [kg] | 51 500 | 47 316 |

| Car body moment of inertia Ic [kgm] | 882e3 | 307e4 |

| Bogie mass mb [kg] | 13 220 | 2 800 |

| Bogie moment of inertia Ib [kgm] | 27 100 | 1 700 |

| Wheelset mass mw [kg] | 2 495 | 1 900 |

| Length over buffer d [m] | 18.59 | 26.50 |

| Bogie axle distance r [m] | 9.90 | 19.00 |

| Wheelset distance b [m] | 3.00 | 2.50 |

| Primary suspension stiffness kp [kN/m] | 3 680 | 1 690 |

| Primary suspension damping cp [kNs/m] | 80 | 20 |

| Secondary suspension stiffness ks [kN/m] | 2 720 | 280 |

| Secondary suspension damping cs [kNs/m] | 200 | 14 |

| V1-B1 | V2-B1 | V1-B2 |

ηV1-B2 / ηV2-B2 |

V2-B2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vPeak ~ vdpc,1,4 | Train speed v [km/h] | 409 | 409 | 413 | - | 406 |

| Acceleration ẅmax [m/s2;] | 13.0 | 12.7 | 12.9 | - | 11.9 | |

| Reduction η [%] | - | -2.4 | -1.0 | 0.12→ | -8.6 | |

| vPeak ~ vdpc,1,8 / vdpc,1,7 | Train speed v [km/h] | 209 | 208 | 221** | - | 232** |

| Acceleration ẅmax [m/s2;] | 6.3 | 5.5 | 2.8 | - | 2.4 | |

| Reduction η [%] | - | -12.9 | -55.9 | 0.89→ | -62.5 | |

| vPeak ~ vdpc,1,11 | Train speed v [km/h] | 149 | 147 | 149* | - | 149*- |

| Acceleration ẅmax [m/s2;] | 4.0 | 3.5 | 0.8 | - | 0.7 | |

| Reduction η [%] | - | -12.0 | -80.6 | 0.97→ | -82.7 |

| V1-B1 | V2-B1 | V1-B2 |

ηV1-B2 / ηV2-B2 |

V2-B2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vPeak ~ vdpc,1,4 | ζ1 = ζEC | ẅmax [m/s2;] | 13.0 | η [%] | -2.4 | -1.0 | 0.12→ | -8.6 |

| ζ2 = 1.5 ζEC | 9.6 | -0.6 | 0.2 | -0.04→ | -4.4 | |||

| ζ3 = 2.0 ζEC | 7.9 | -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.04→ | -4.0 | |||

| vPeak ~ vdpc,1,8 / vdpc,1,7 | ζ1 = ζEC | ẅmax [m/s2;] | 6.3 | η [%] | -12.9 | -55.9** | 0.89→ | -62.5** |

| ζ2 = 1.5 ζEC | 5.3 | -6.1 | -55.2 | 0.90→ | -61.1 | |||

| ζ3 = 2.0 ζEC | 4.8 | -5.4 | -55.9** | 0.93→ | -60.0 | |||

| vPeak ~ vdpc,1,11 | ζ1 = ζEC | ẅmax [m/s2;] | 4.0 | η [%] | -12.0 | -80.6* | 0.97→ | -82.7* |

| ζ2 = 1.5 ζEC | 3.0 | -7.7 | -75.7* | 0.97→ | -77.7* | |||

| ζ3 = 2.0 ζEC | 2.7 | -8.1 | -73.9* | 0.98→ | -75.2* |

| V1-B1 | V2-B1 | V1-B2 |

ηV1-B2 / ηV2-B2 |

V2-B2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vPeak ~ vdpc,1,4 | ẅmax [m/s2;] | 13.0 | η [%] | -2.4 | -6.4 | 0.24→ | -27.4 | |

| -1.0 | 0.12→ | -8.6 | ||||||

| 1.4 | ~ | 0.0 | ||||||

| vPeak ~ vdpc,1,8 / vdpc,1,7 | ẅmax [m/s2;] | 6.3 | η [%] | -12.9 | -68.8** | 0.92→ | -75.1** | |

| -55.9** | 0.89→ | -62.5** | ||||||

| -42.3** | 0.85→ | -49.8* | ||||||

| vPeak ~ vdpc,1,11 | ẅmax [m/s2;] | 4.0 | η [%] | -12.0 | -87.0 | 0.99→ | -87.7* | |

| -80.6* | 0.97→ | -82.7* | ||||||

| -72.2* | 0.96→ | -75.0* | ||||||

| = 50 000 kN/m2;;= 100 000 kN/m2;;= 200 000 kN/m2; | ||||||||

| V1-B1 | V2-B1 | V1-B2 | ηV1-B2 / ηV2-B2 | V2-B2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vPeak ~ vdpc,1,4 | ẅmax [m/s2;] | 13.0 | η [%] | -2.4 | -1.5 | 0.19 | -7.8 | |

| -1.1 | 0.12 | -8.6 | ||||||

| -1.3 | 0.15 | -8.9 | ||||||

| vPeak ~ vdpc,1,8 / vdpc,1,7 | ẅmax [m/s2;] | 6.3 | η [%] | -12.9 | -57.4 | 0.92 | -62.5 | |

| -55.9** | 0.89 | -62.5** | ||||||

| -55.6 | 0.89 | -62.7 | ||||||

| vPeak ~ vdpc,1,11 | ẅmax [m/s2;] | 4.0 | η [%] | -12.0 | -80.3 | 0.97 | -82.8 | |

| -80.6* | 0.97 | -82.7* | ||||||

| -80.9 | 0.98 | -82.7 | ||||||

| = 30 kN/m2;;= 60 kN/m2;;= 100 kN/m2; | ||||||||

| ζ | V1-B1 | V2-B1 | V1-B2 | V2-B2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ζ1 = ζEC | vlim [km/h] | 147 | 147 | 357 | 354 | ||

| ζ2 = 1.5 ζEC | 184 | 188 | 359 | 354 | |||

| ζ3 = 2.0 ζEC | 187 | 189 | 363 | 356 | |||

| ζ1 = ζEC | vlim [km/h] | 147 | 147 | 359 | 354 | ||

| 357 | 354 | ||||||

| 205 | 352 | ||||||

| ζ1 = ζEC | vlim [km/h] | 147 | 147 | 357 | 348 | ||

| 357 | 354 | ||||||

| 357 | 354 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).