1. Introduction

The dynamic interaction between railway rolling stock and bridge structures plays a crucial role in ensuring the safety and stability of train operations [

1]. The movement of freight trains, particularly empty gondola cars with worn wheel profiles, introduces complex oscillatory phenomena that can influence both the rolling stock and the bridge superstructure [

2]. In modern railway engineering, increasing train speeds and evolving track infrastructure necessitate a detailed understanding of these interactions to prevent derailments and structural damage [

3]. One of the key challenges in railway dynamics is bogie wobbling, an instability that arises at certain critical speeds, leading to periodic transverse impacts between train wheels and rails [

4]. This phenomenon, combined with the elastic and inertial properties of bridge superstructures, can induce resonant transverse oscillations, amplifying structural vibrations and increasing derailment risks [

5]. In previous research, steam locomotives in the early 20th century exhibited strong forced oscillations due to eccentric wheel drive mechanisms [

6], but in modern railway operations, empty freight wagons present new instability concerns at high speeds [

7]. This study aims to analyze the dynamic interaction between freight gondola cars and a metal bridge superstructure (55 m span with through trusses) under various speed conditions. Using finite element modeling and numerical simulations, the research evaluates the influence of track conditions, wheel wear [

8], and bridge flexibility on rolling stock stability. The primary objectives of this study are:

To determine safe operational speed limits for empty freight gondola cars on a railway bridge;

To identify critical speed thresholds where resonant transverse oscillations, occur due to wheel-rail impact forces;

To assess the influence of bridge superstructure properties on rolling stock stability under real operating conditions;

To compare modern structural responses with early 20th-century experimental data to assess the evolution of train-bridge interactions.

The findings indicate that for speeds up to 80 km/h, safe operation is maintained [

9], but at 90 km/h, resonant transverse oscillations reach amplitudes of 11 mm, exceeding permissible limits. Furthermore, the elastic and inertial properties of the bridge influence rolling stock stability by approximately 15%, necessitating speed restrictions and further structural modifications to mitigate excessive oscillations [

10]. This research contributes to railway safety and infrastructure optimization, offering practical recommendations for train speed regulations, bogie design improvements, and bridge structural enhancements. The study’s results serve as a foundation for future investigations, which should incorporate wind and seismic effects to ensure a more comprehensive understanding of train-bridge interactions in high-speed freight operations [

11].

During the development of any structure, the designer solves the problem of assessing its stress-strain state [

12]. To do this, it is necessary to know the stress distribution pattern in all elements of the designed structure and the magnitude of the displacements of characteristic points both under static external loading and under time-varying loads. Today, the design and calculation of bridge structures is impossible without the use of modern computer technologies [

13]. These are FEM software packages focused on calculating bridge structures, which allow you to build finite element models of structures with minimal labor costs. They provide the special capabilities necessary for calculating bridges (for example, constructing influence lines for calculating moving loads, for calculating nodal connections, for checking local stability, for calculating the thermal stress state of supports, etc. [

14]. With the traditional approach, to solve such a problem in the general case, it is necessary to solve a system of equations that ensure the fulfillment of the conditions of equilibrium and compatibility of deformations. The problem that arises in this regard is that in the case of a complex two-dimensional or three-dimensional structure, the behavior of the system is described by high-order equations with a large number of unknowns. One way to eliminate this difficulty is to use approximate solution methods. Currently, the most effective approximate method for solving applied problems of mechanics is the finite element method (FEM) [

15]. This method essentially boils down to approximating a continuous medium with an infinite number of degrees of freedom by a set of subdomains (or elements) with a finite number of degrees of freedom. For each element, some form functions are specified that allow one to determine the displacement field inside the element based on the displacements at the nodes, i.e. at the junctions of the finite elements [

16]. FE interact with each other only through nodes. External loads acting on FE, such as concentrated and distributed forces and moments, are reduced to its nodes and are called nodal loads. In calculations using the FE method, the displacements of the model nodes are first determined. The values of internal forces in an element are proportional to the displacements in its nodes. The proportionality coefficient is a square stiffness matrix, the number of rows of which is equal to the number of degrees of freedom of the element [

17]. All other FE parameters, such as stresses, displacement field, etc., are calculated based on its 2 nodal displacements. The main types of finite elements used in practice are: rod; shell/plate; volumetric. The entire variety of models of structures and parts can be described using FE of different types or their combinations [

18]. At the same time, this approach is not applicable to calculations of geometrically variable structures that turn into mechanisms.

3. Results and Discussion

The study included 8 numerical experiments that simulated the movement of rolling stock along the superstructure [

33]. To determine the effect of elastic and inertial properties of the superstructure on the safety of train movement, a series of calculations were performed for movement along the roadbed, the profile and track plan of which were taken to be straight, but the unevenness of the rails and the wear of the wheel profiles were taken into account, as in the calculations for movement along the superstructure.

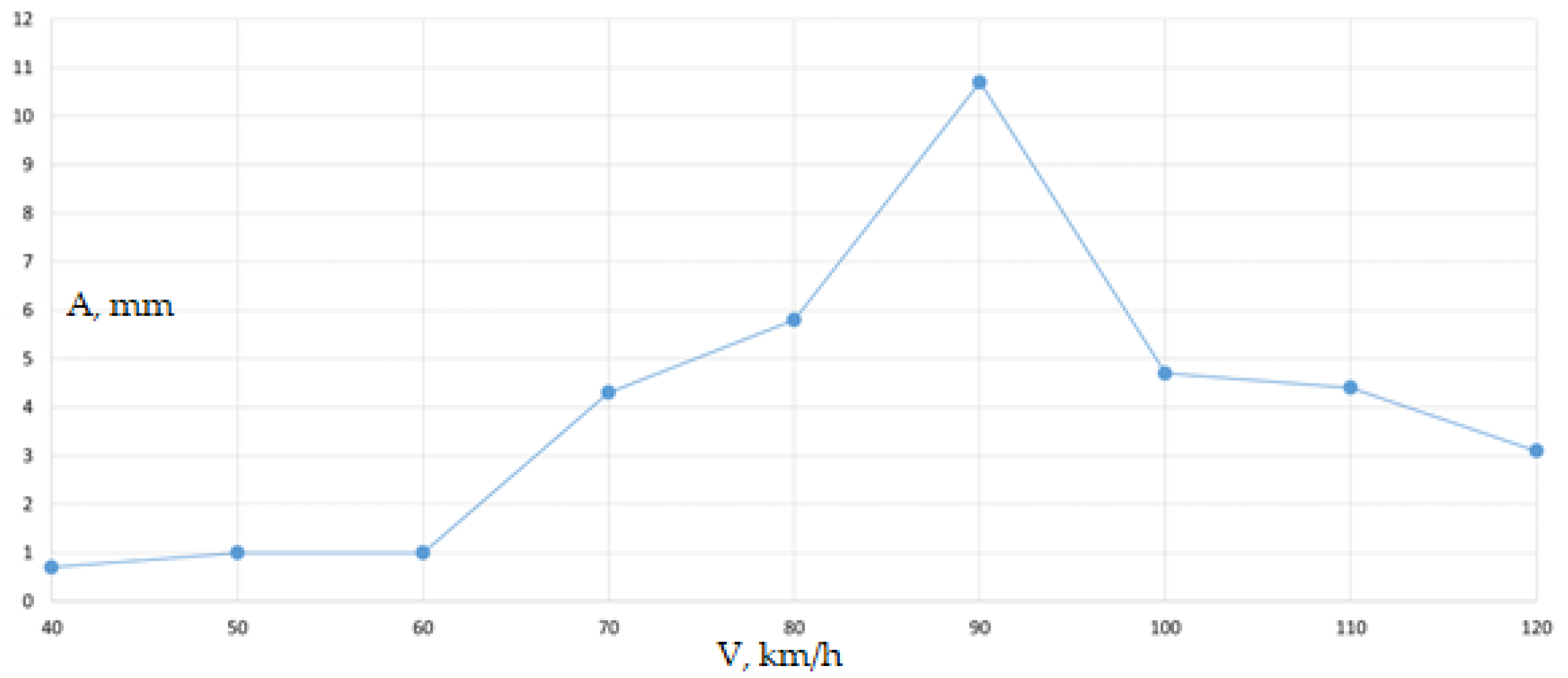

Figure 14 shows the dependence of the amplitudes of transverse oscillations of the superstructure on the speed of the train.

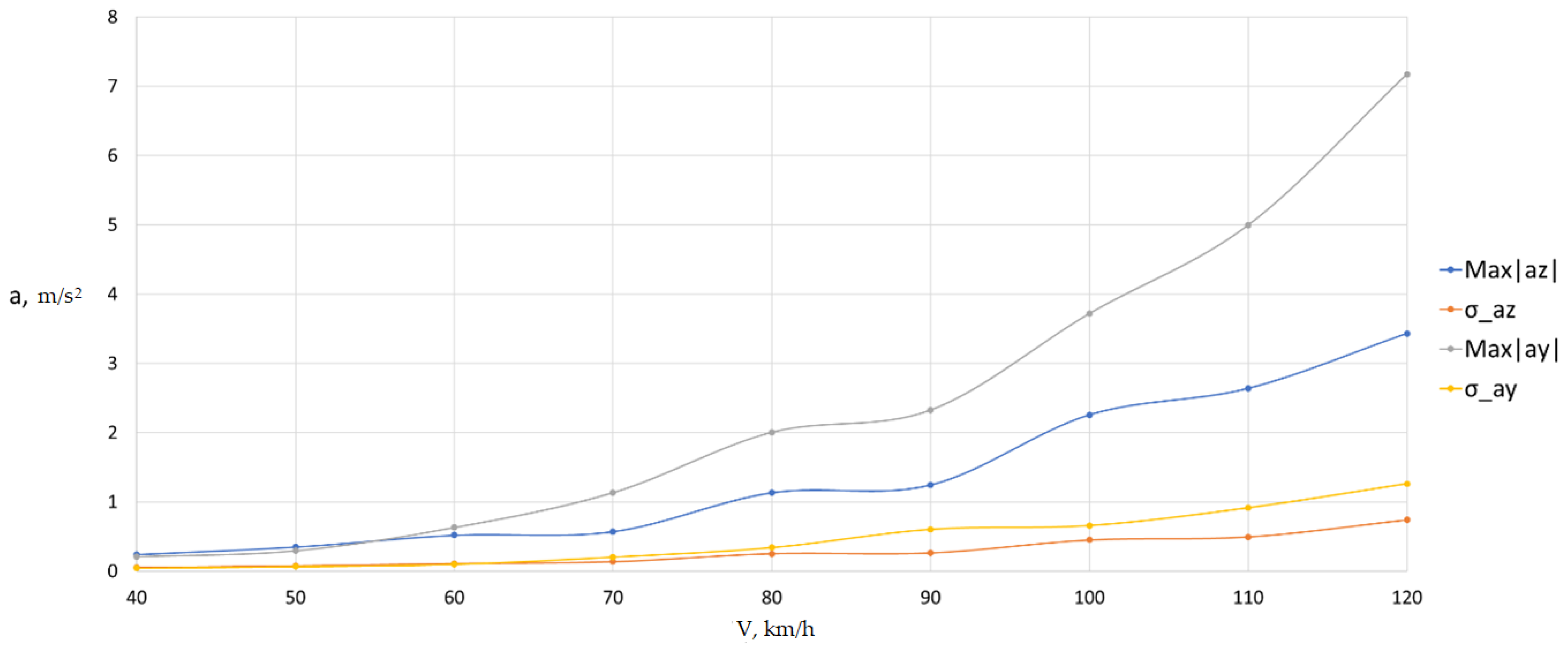

Table 2 shows the maximum absolute and standard deviations of the vertical and horizontal transverse accelerations of the span structure.

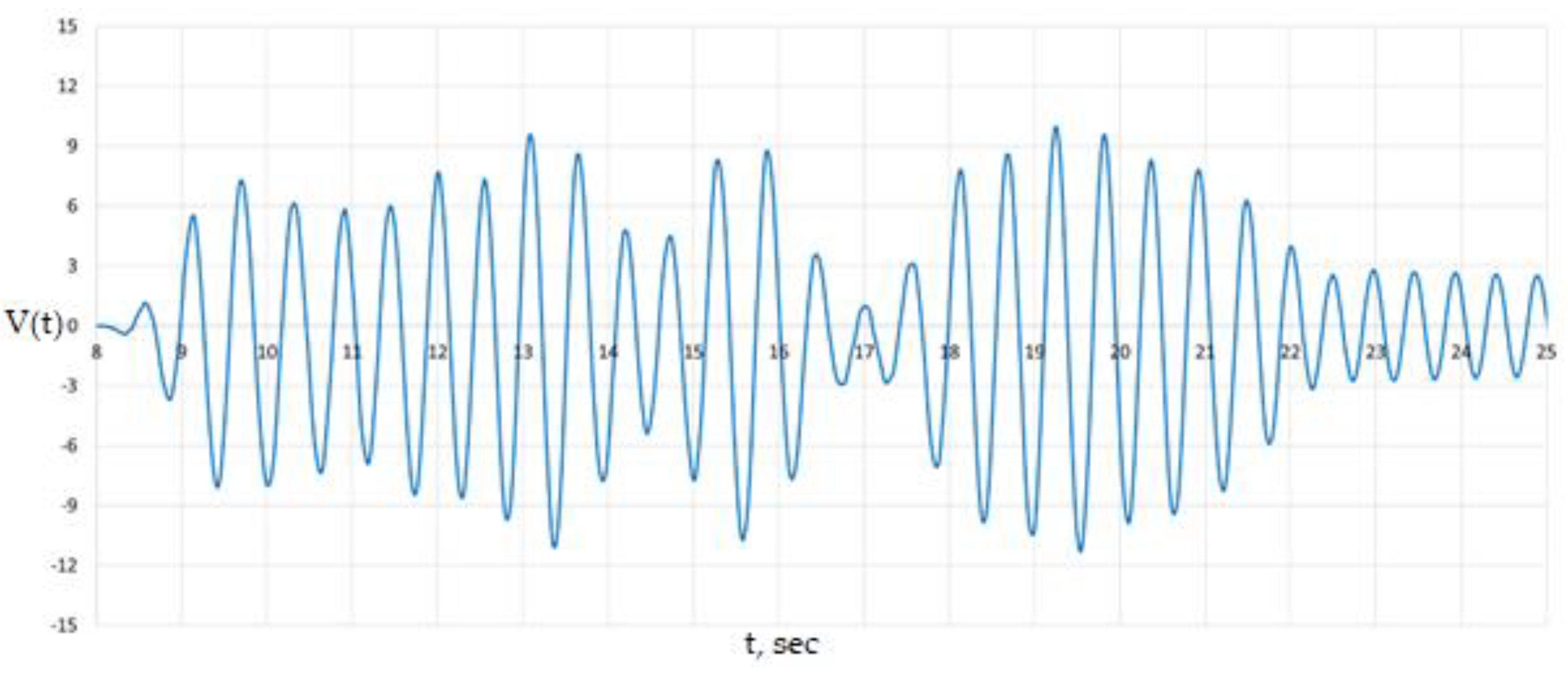

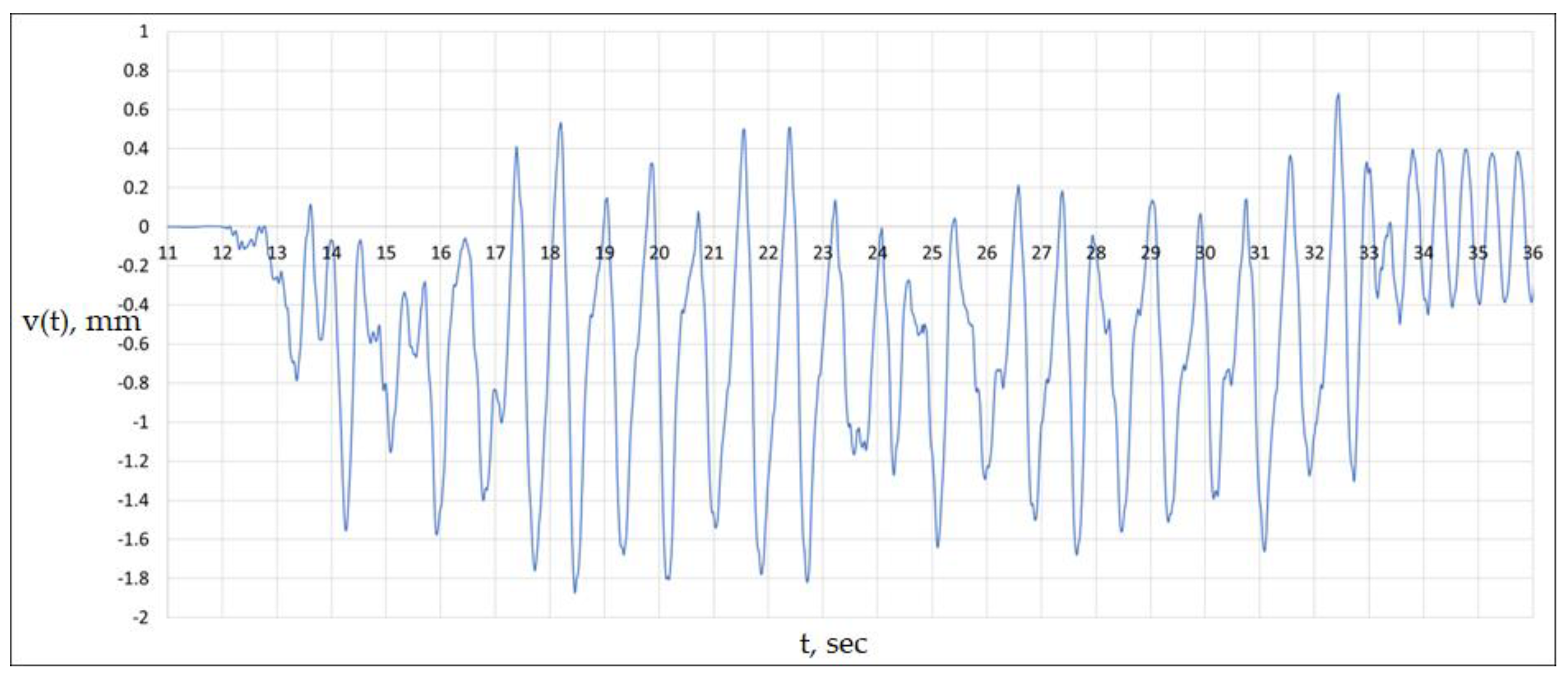

It is interesting to note the increase in the amplitude of transverse vibrations to 11 mm at a speed of 90 km/h. The displacements are shown in

Figure 16.

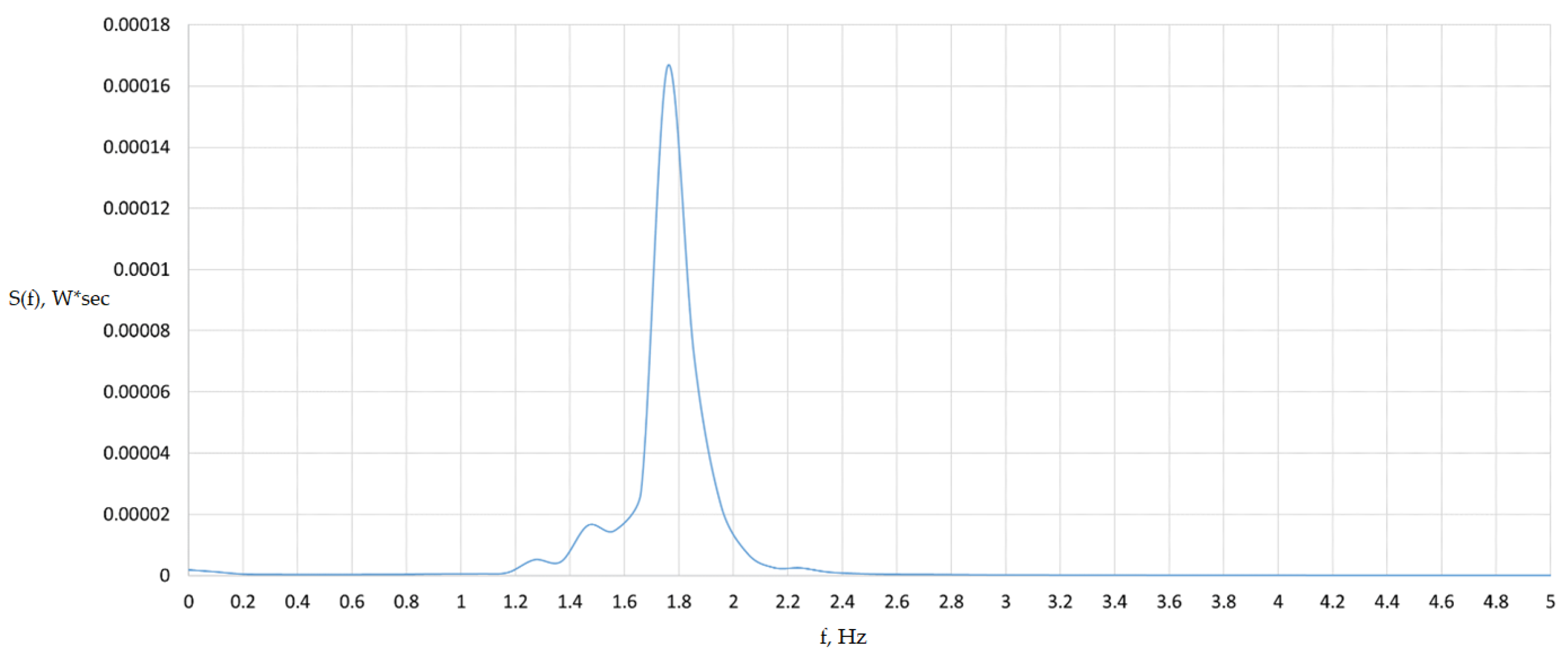

Figure 17 shows the spectral composition of the oscillations, from which it follows that the fundamental frequency is f = 1.76 Hz.

Considering that the period of oscillation of the span increases when a train moves along it due to the increase in the total mass of the system, we determine the period of the loaded structure:

where

– is the period of oscillation of an unloaded span structure, s;

p – is the linear weight of rolling stock, tf/m;

m – is the linear weight of the span structure, tf/m.

This value corresponds to the frequency f = 1.76 Hz. Consequently, at the speed V = 90 km/h, resonance occurs, caused by the coincidence of the natural transverse bending frequency of the loaded span structure oscillations and the frequency [

34] of transverse impacts of the vehicle wheels on the rail (the wobble frequency).

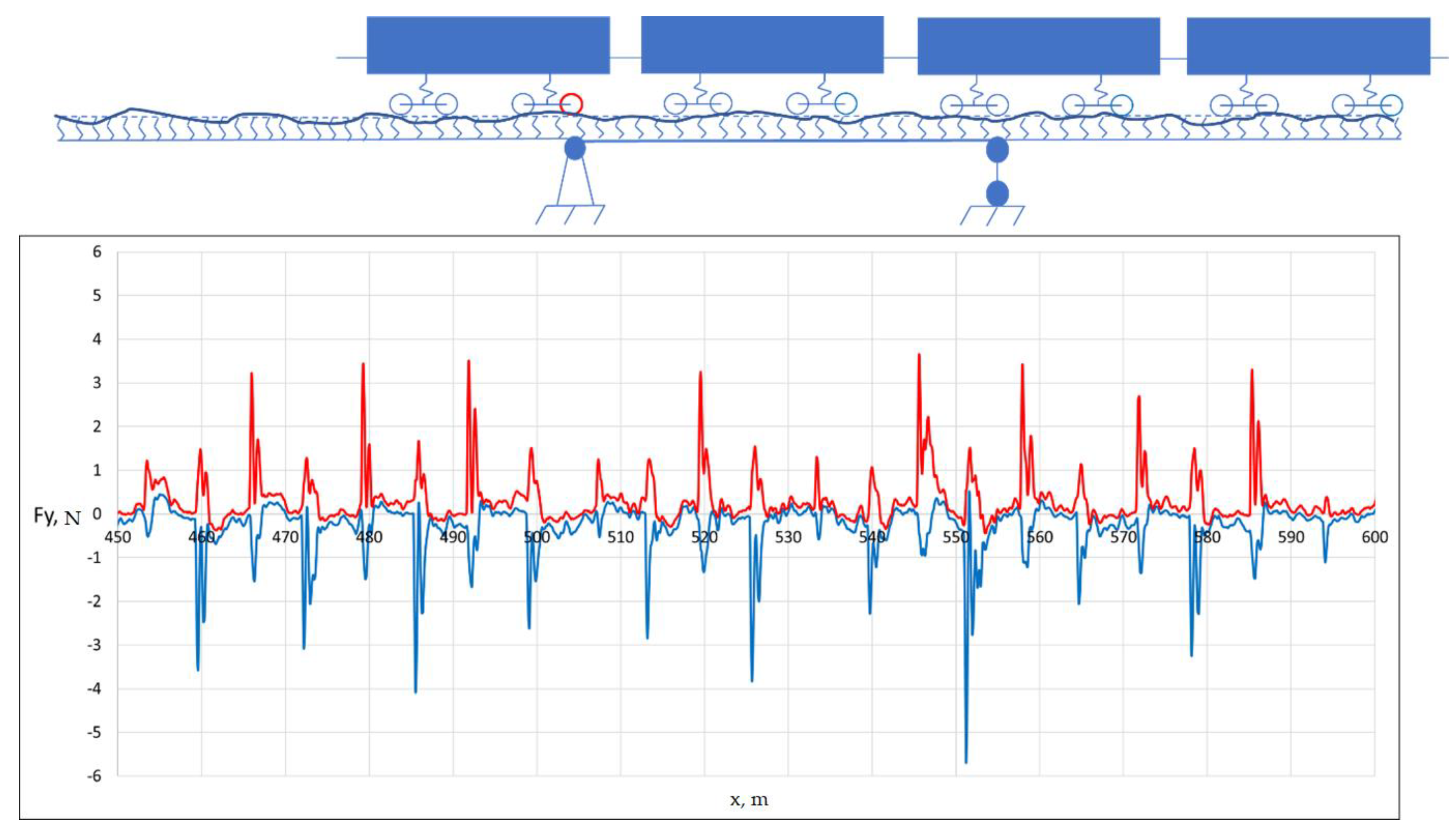

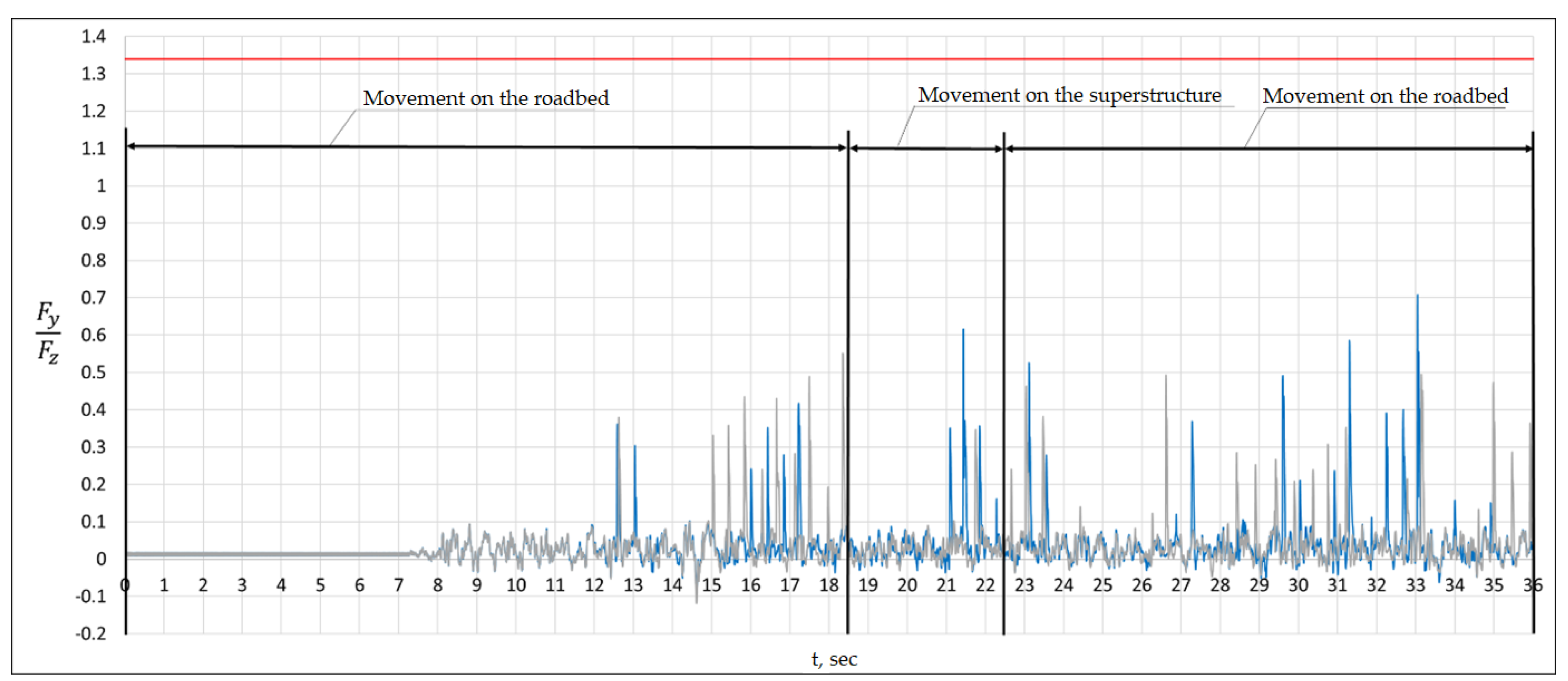

Figure 18 shows the graphs of the transverse forces in the wheel-rail contact of the first wheelset of car 23, obtained at 90 km/h.

The jumps in the graph correspond to the transverse impact of the wheel flange on the rail.

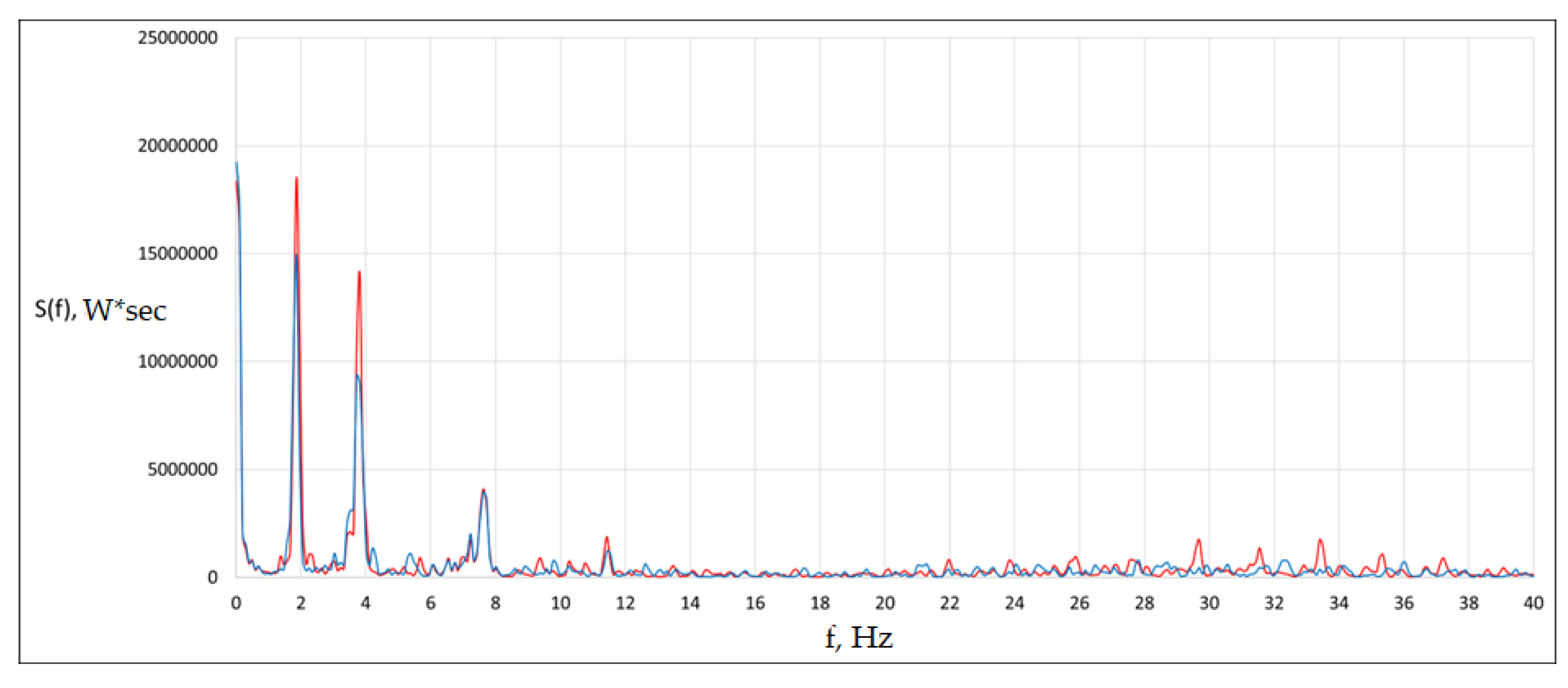

Figure 19 shows the graphs of the spectra, in which the fundamental frequency is f = 1.8 Hz.

At a speed of V = 90 km/h, at which resonant vibrations of the superstructure are observed, movement both on it and on the roadbed is characterized by the danger of derailment.

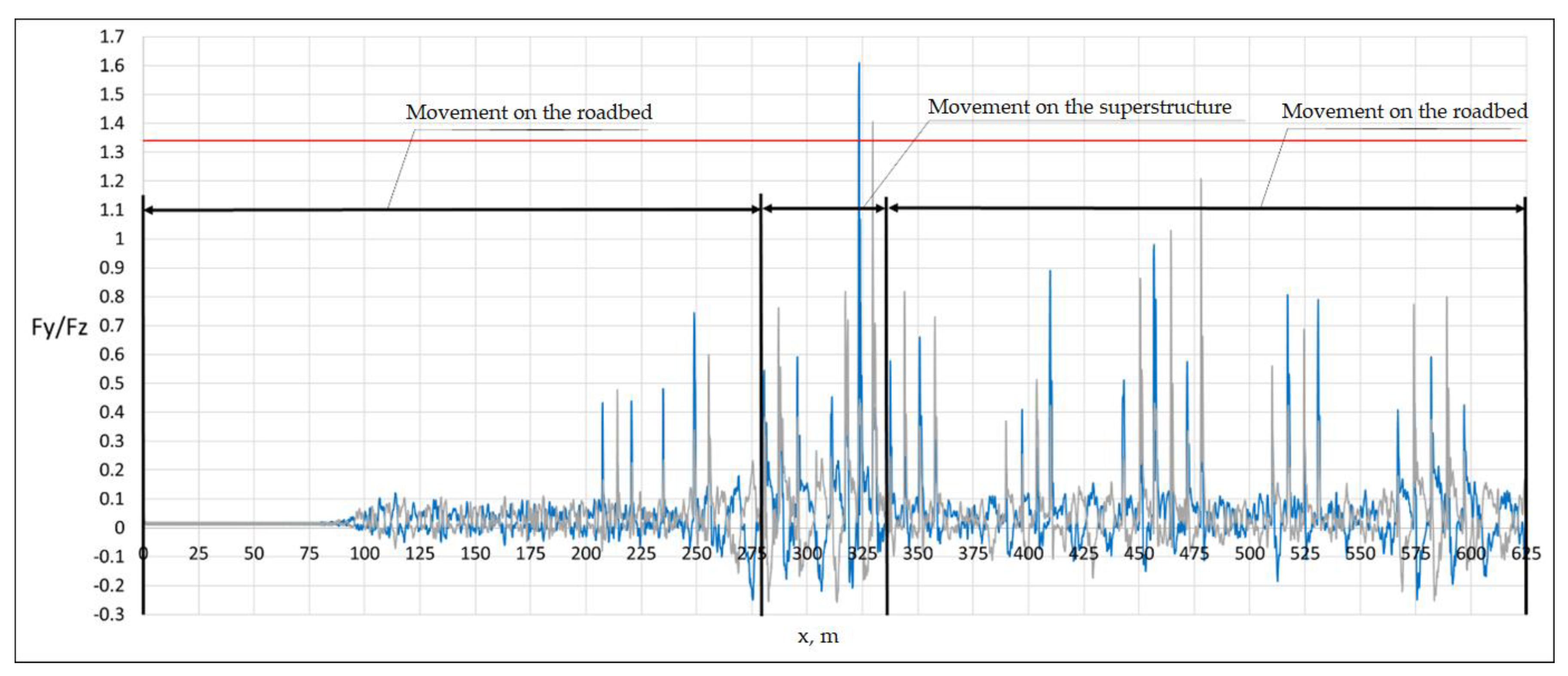

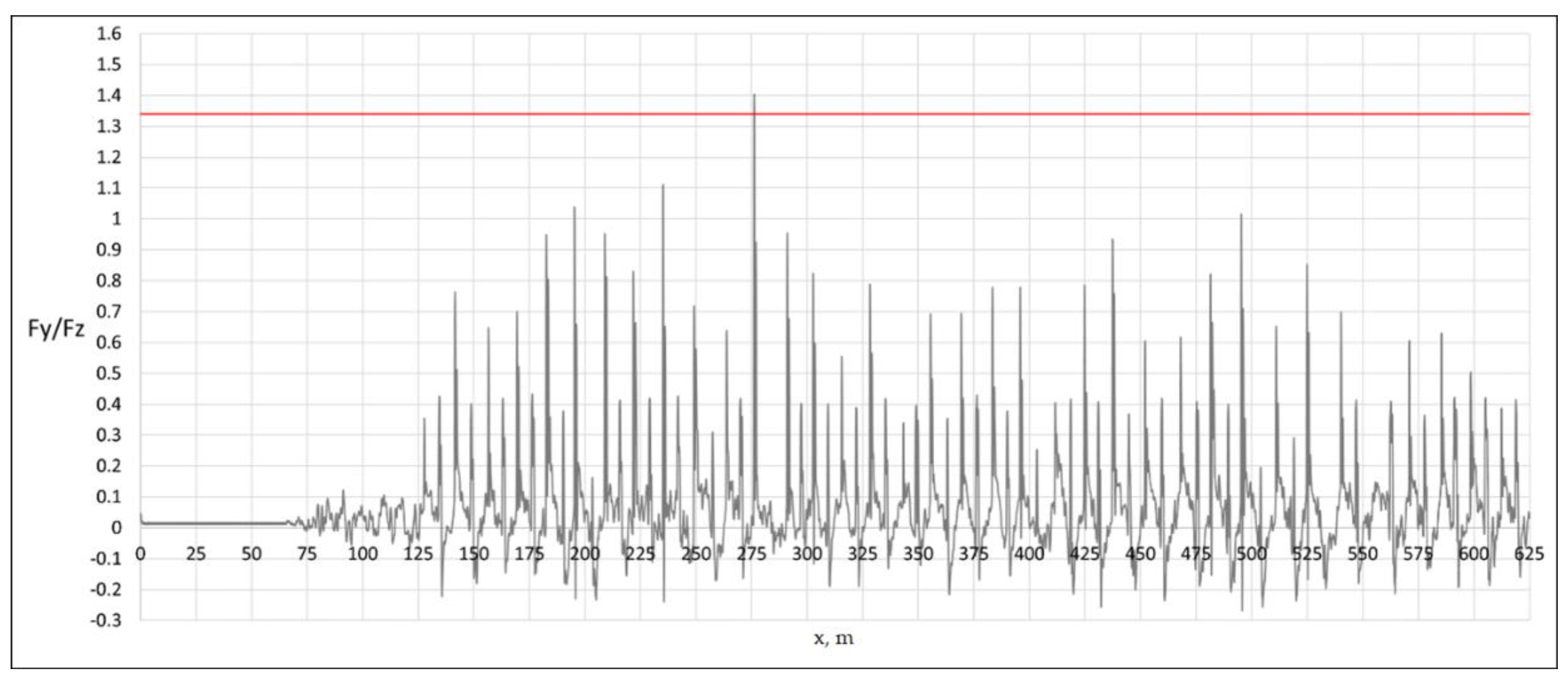

Figure 20 shows the graphs of the Nadal criterion of the 3rd wheel pair of the 6th car.

The maximum value of the Nadal criterion is recorded on the span structure and is equal to 1.61, which is 20% higher than the permissible value.

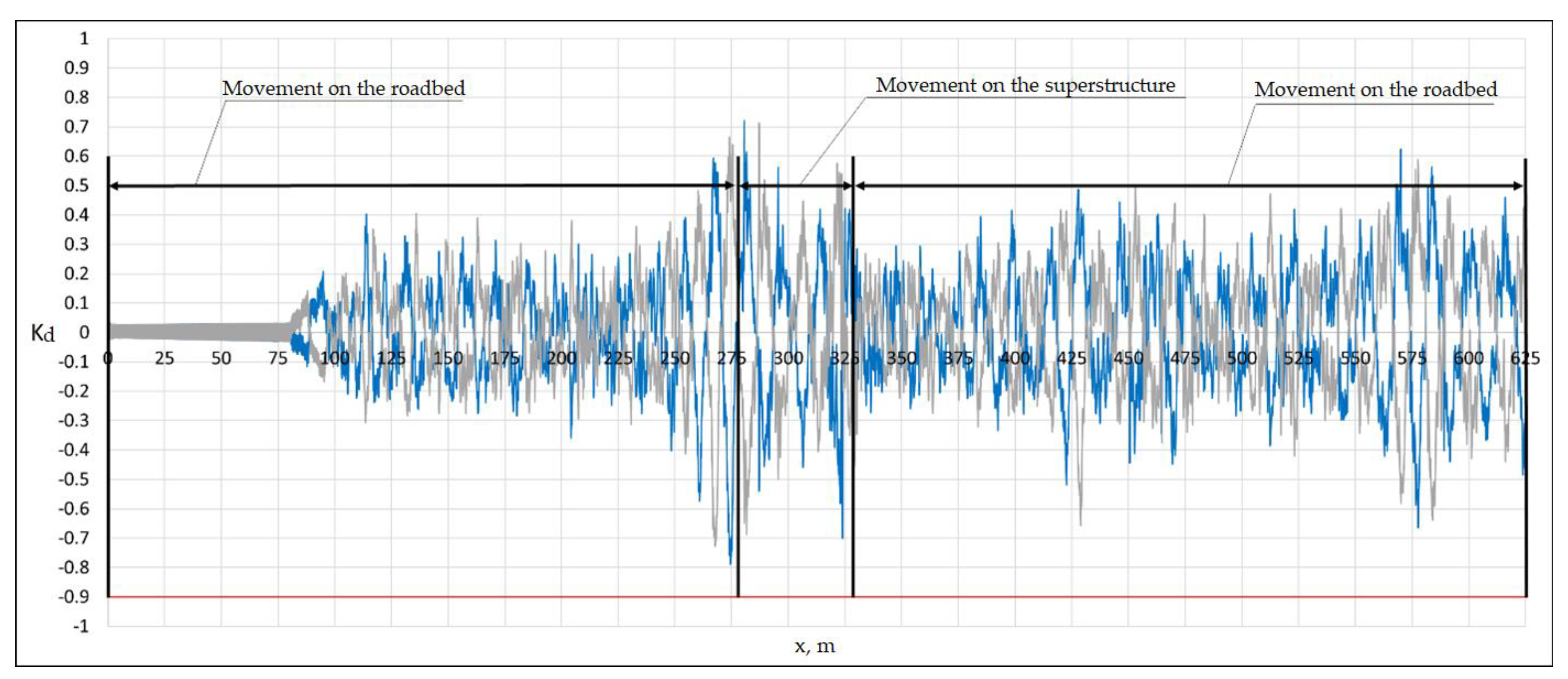

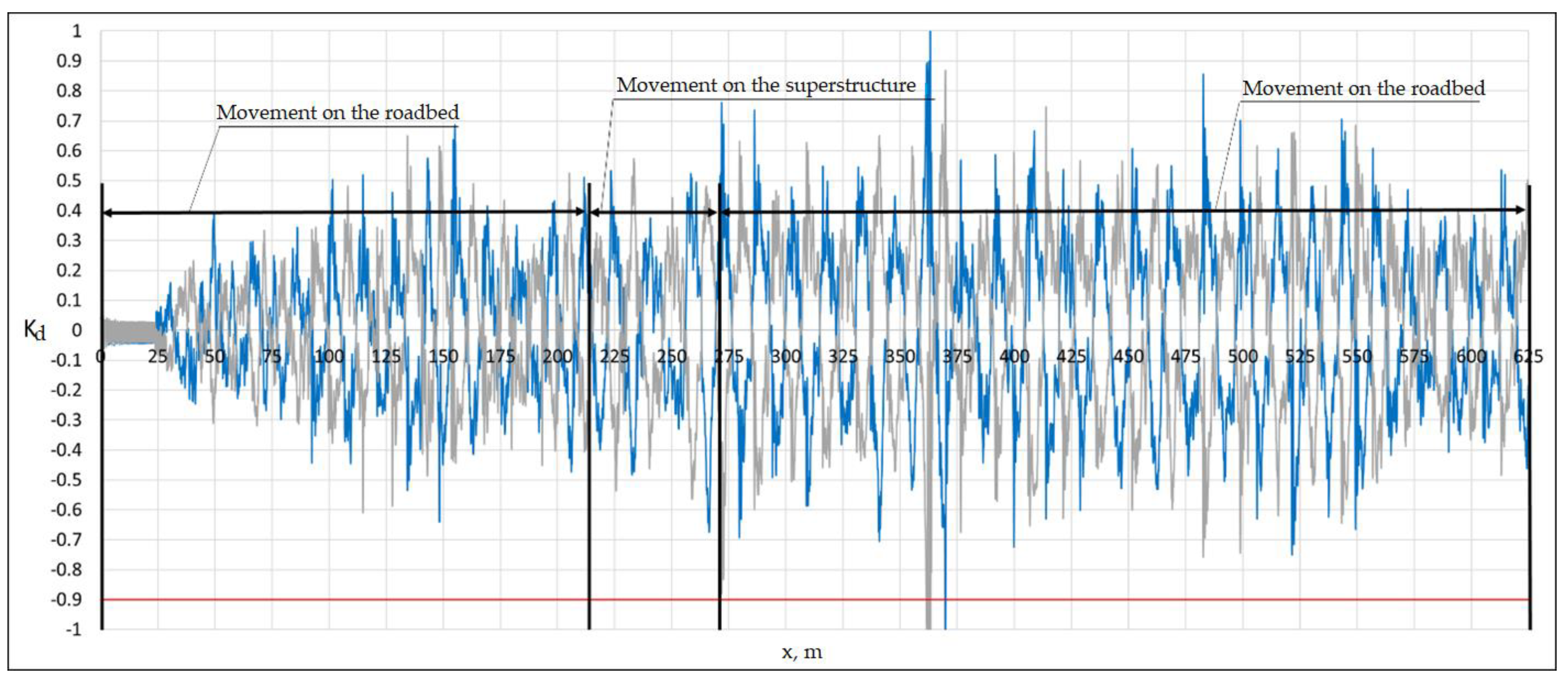

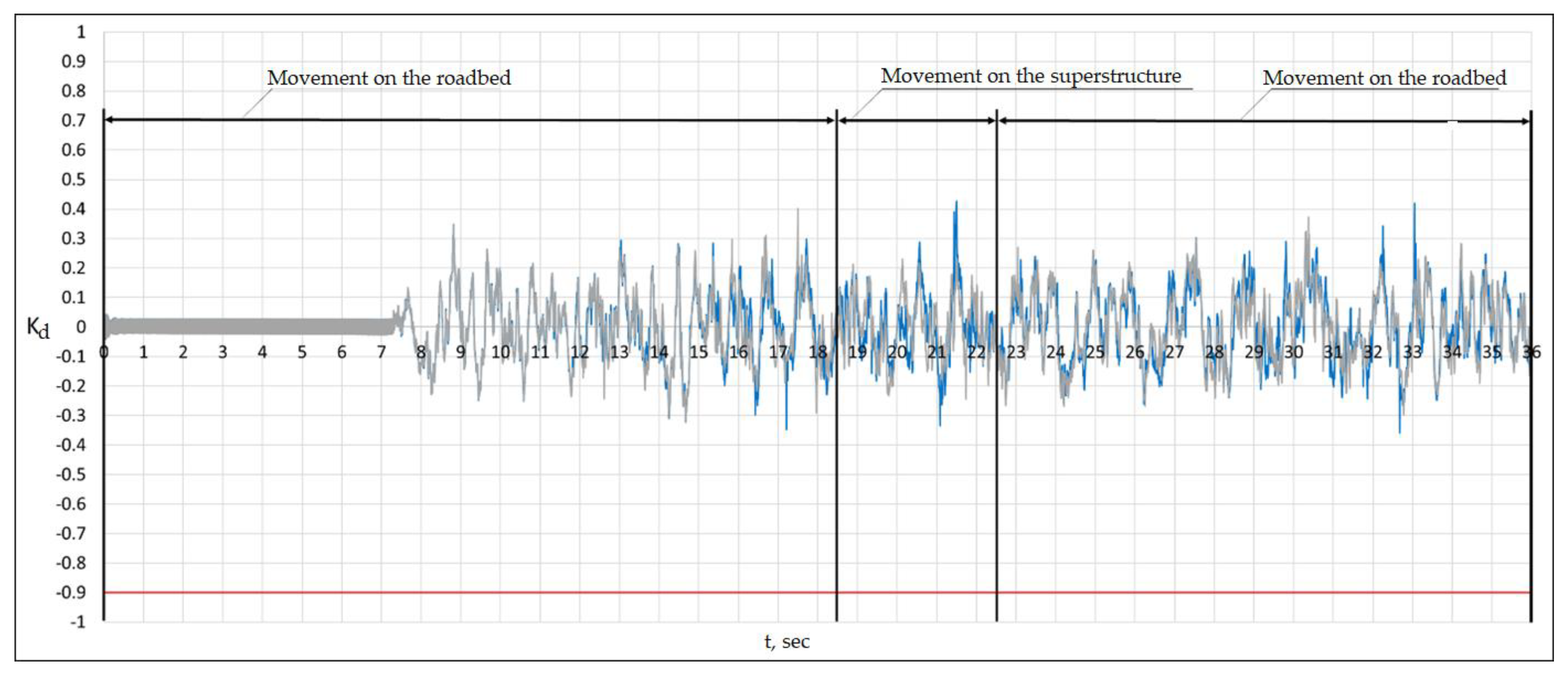

Figure 21 shows the graphs of the wheel-rail dynamic coefficients.

There is no vertical separation of the wheels from the rails.

Figure 22 shows the graphs of the wheel-rail dynamic coefficient for the 1st wheel pair of the 2nd car.

80 m after leaving the superstructure, alternating vertical separation of the wheels from the rails occurs due to significant transverse impacts. To determine the influence of the superstructure on the safety of the rolling stock [

35], we compare the results of numerical experiments when moving along the superstructure and the roadbed (

Figure 23).

Figure 24 shows the graph of the Nadal criterion for the left wheel of the 1st wheelset of the 5th car, obtained in the calculation without a superstructure when moving along the roadbed at a speed of 90 km/h.

The maximum value of the Nadal criterion for movement along the roadbed exceeded the permissible value and amounted to 1.4, while for movement along the superstructure at the same speed of 90 km/h, the value of 1.61 was recorded (see

Figure 20). The ratio of these values (1.61/1.4 = 1.15 or 15%) can be characterized as the influence of the elastic and inertial properties of the superstructure on the stability of the movement of rolling stock or, more simply, the "influence of the bridge" on the dynamics of the rolling stock.

It should be noted that not all calculation cases have been considered, and it is too early to draw final conclusions. For example, the current calculations do not take into account the transverse wind effect on both the rolling stock and the bridge superstructure [

36]. The latter causes general transverse deformations of the superstructure and corresponding deformations of the rails in the plan, especially in the above-support zones. The passage of bogies in these zones is accompanied by additional negative dynamics. In this case, the "influence of the bridge" was maximally manifested at the "bogie wobble" speed exceeding the critical value, which in turn caused resonant transverse vibrations of the superstructure. Recall that in the previous article [

2], vertical vibrations were similarly investigated and resonant vertical vibrations were detected at a speed of 60 km/h. In that case, the "influence of the bridge", although recorded under other conditions, also amounted to a comparable value (10%).

When empty cars are moving on bogies of the 18-100 model without elastic constant contact sliders at a speed of 90 km/h, intense wobbling will occur, which is also noted in scientific articles [

4,

5]. The danger of derailment appears both when moving along the superstructure and the roadbed, as calculations show. An increase in the transverse rigidity of the superstructure, which would lead to a decrease in the amplitude of oscillations, would not lead to stabilization of the movement of cars.

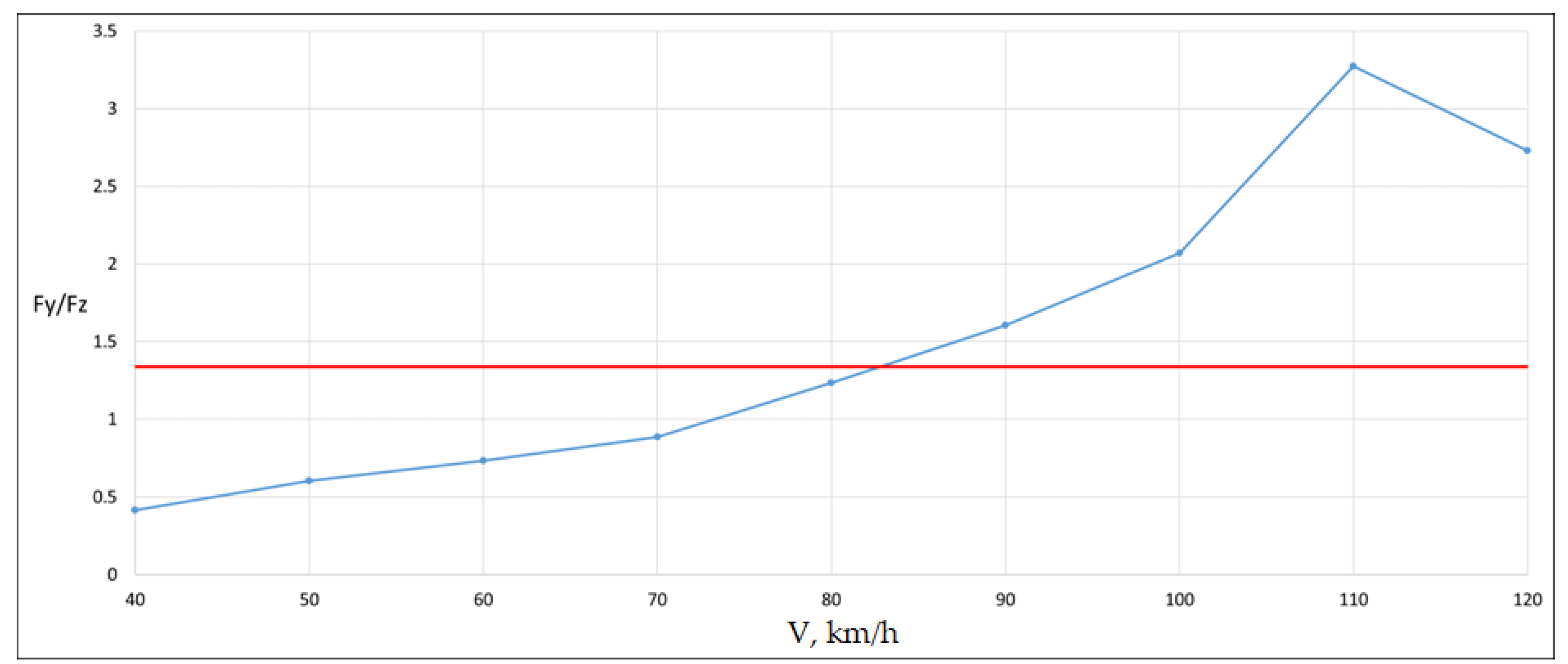

Figure 25 shows a graph of the maximum value of the Nadal criterion depending on the speed, constructed based on the results of calculations taking into account the superstructure.

All maximum values were recorded either on the superstructure or when moving along the roadbed after the exit. It follows from the graph that safe movement modes are in the speed range of 40 - 80 km / h. Let us consider the oscillations of the superstructure and rolling stock at 60 km / h. As will be shown below, the maximum amplitudes of transverse oscillations of the superstructure in tests conducted 100 years ago were obtained at 64 km / h.

Figure 26 shows a graph of horizontal transverse oscillations of the superstructure, obtained in the calculation at a speed of 60 km / h.

The picture qualitatively differs from the results at a speed of 90 km/h – resonance is not observed. The largest amplitudes of oscillations are observed in the time interval of 21 – 23 s. Of the cars passing along the span in this time interval, the worst safety indicators were recorded for car No. 9.

Figure 27 and

Figure 28 show the safety criteria for the left wheel of the 1st wheelset of the 9th car from calculations with and without taking into account the span.

The oscillations of the superstructure have a negative impact on the dynamics of the crew, but at the same time the criteria for traffic safety are far from the limit values. Of interest is the comparison of the obtained oscillations of the superstructure during interaction with the rolling stock under modern operating conditions with the results of experimental studies from the beginning of the last century.

Table 3 shows the calculated span lengths, the type of test train, the speed of movement and the amplitudes of forced oscillations of the superstructures [

7].

A comparison of the experimental data in

Table 3 on the vibrations of span structures from the early 20th century with the results of calculations for a modern structure allows us to draw the following conclusions:

Under modern operating conditions and speed modes similar to the data in

Table 3, the impact of the rolling stock [

35] on the superstructure is found to be many times smaller. For example, in the calculation at a speed of 60 km/h, the amplitude of transverse vibrations was 1 mm, whereas the vibrations of the superstructure during interaction with steam locomotives obtained experimentally at the beginning of the 20th century correspond to an amplitude of 9 mm. The significantly larger amplitudes of transverse vibrations of superstructures obtained during tests in the 20th century can be explained by the influence of the design features of steam locomotives (beating from the eccentric wheel drive) [

20]. An analysis of the critical speed of modern locomotives and an earlier study of an off-grade superstructure of 2x176 m [

10] also confirm their significantly smaller dynamic impact on the superstructure compared to steam locomotives;

With the increase in speeds, a new problem arose - instability of the movement of empty wagon bogies - wobbling. As the calculations show, it is this factor in modern realities that determines the critical speeds of movement and the maximum dynamics of the interaction of the rolling stock and the superstructure (the greatest transverse accelerations and oscillation amplitudes), which in the resonant mode are 11 mm, which exceeds the "dynamics of steam locomotives".

4. Conclusions

At a speed of movement of empty freight gondola cars with moderately worn wheel profiles without taking into account wind and seismic effects of up to 80 km/h, safe operation of the metal superstructure is ensured. If the speed of movement is more than 80 km/h, then the permissible values of the amplitude of transverse vibrations of superstructures both when moving along the roadbed and along the superstructure may exceed the permissible ones, which may cause the rolling stock to derail.

At the maximum speed of 90 km/h established for freight rolling stock, resonant transverse horizontal vibrations of the superstructure with an amplitude of 11 mm were recorded, caused by the coincidence of the natural frequency of horizontal bending vibrations of the loaded structure and the frequency of transverse impacts of the car wheels on the rails, which are a consequence of the instability of movement (wobbling of the cars).

It has been established that the speed of movement of freight rolling stock on bogies of model 18-100 without modernization of the bogies, or of a completely empty train, should be limited to 90 km/h, both on the track bed and on the superstructure, to ensure traffic safety conditions.

The influence of the elastic and inertial properties of the studied span structure with through trusses L = 55 m on the safety of rolling stock under conditions of movement with a given track condition, wheel wear and speed range can be estimated at 15%.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.; methodology, A.B.; software, N.S.; validation, S.S.; formal analysis, A.Z. and N.S.; investigation, A.S.; resources, A.B. and S.S.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S. and N.S.; writing—review and editing, A.Z., A.S., and A.B.; visualization, A.Z. and S.S.; supervision, A.S.; project administration, A.Z. and A.S.; funding acquisition, A.B., N.S., and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

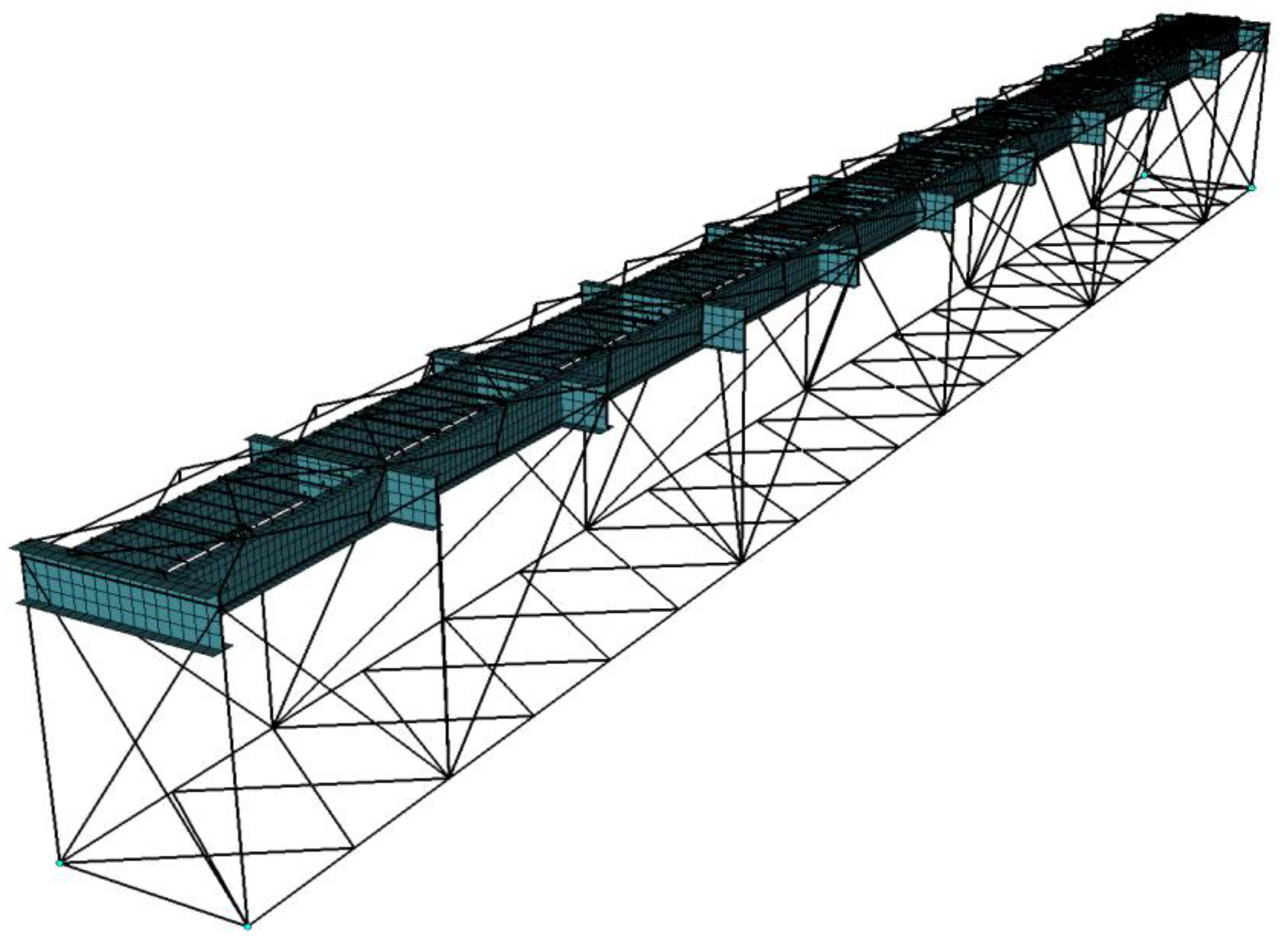

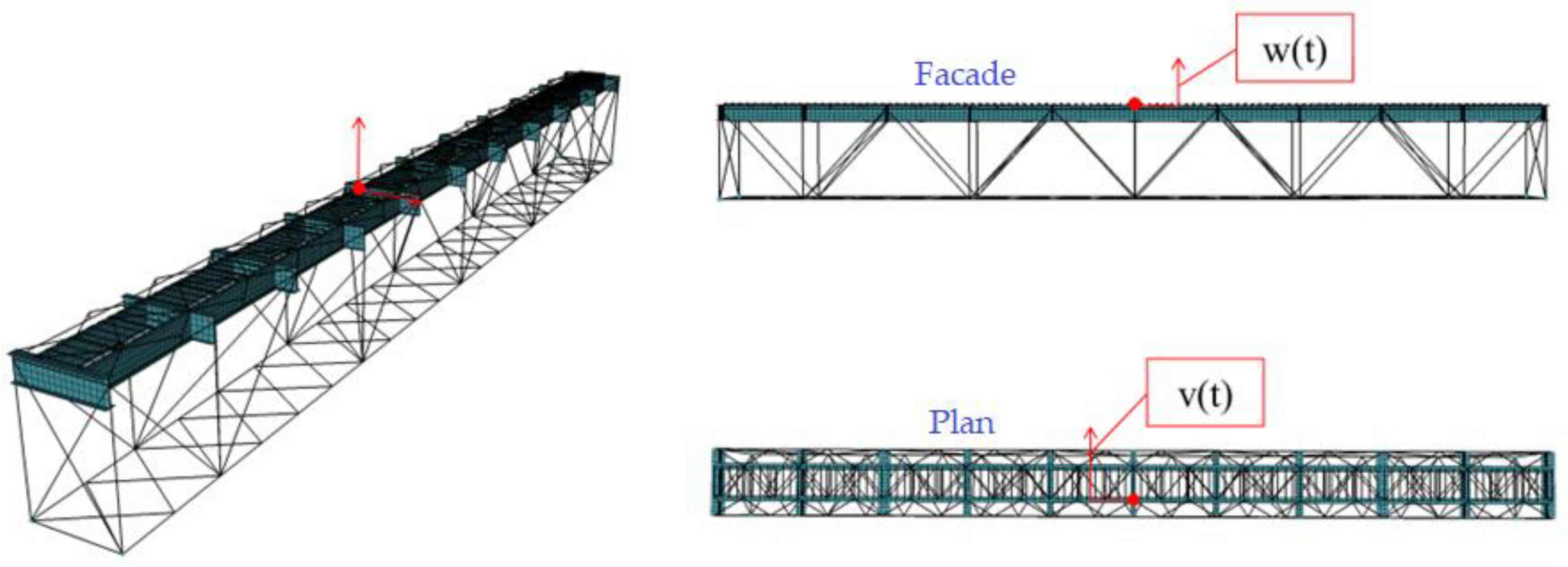

Figure 1.

Finite element model of the span structure.

Figure 1.

Finite element model of the span structure.

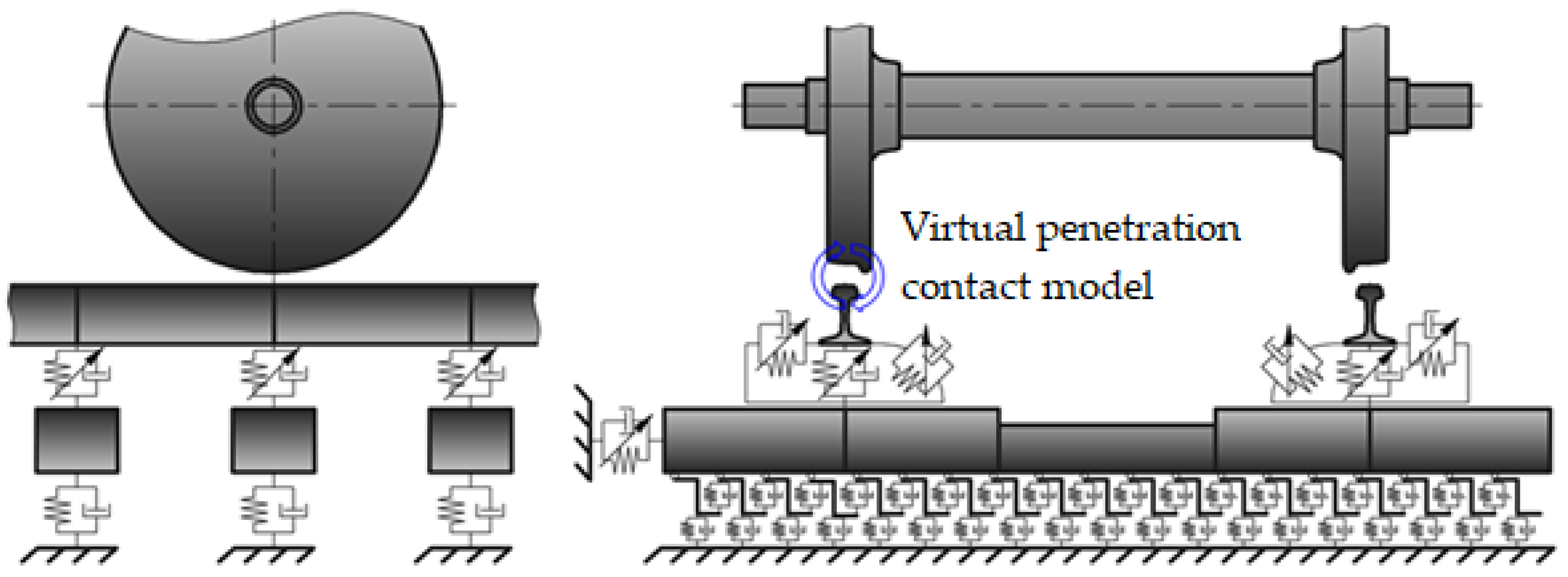

Figure 2.

Diagram of mechanical interaction between the wheelset and the track.

Figure 2.

Diagram of mechanical interaction between the wheelset and the track.

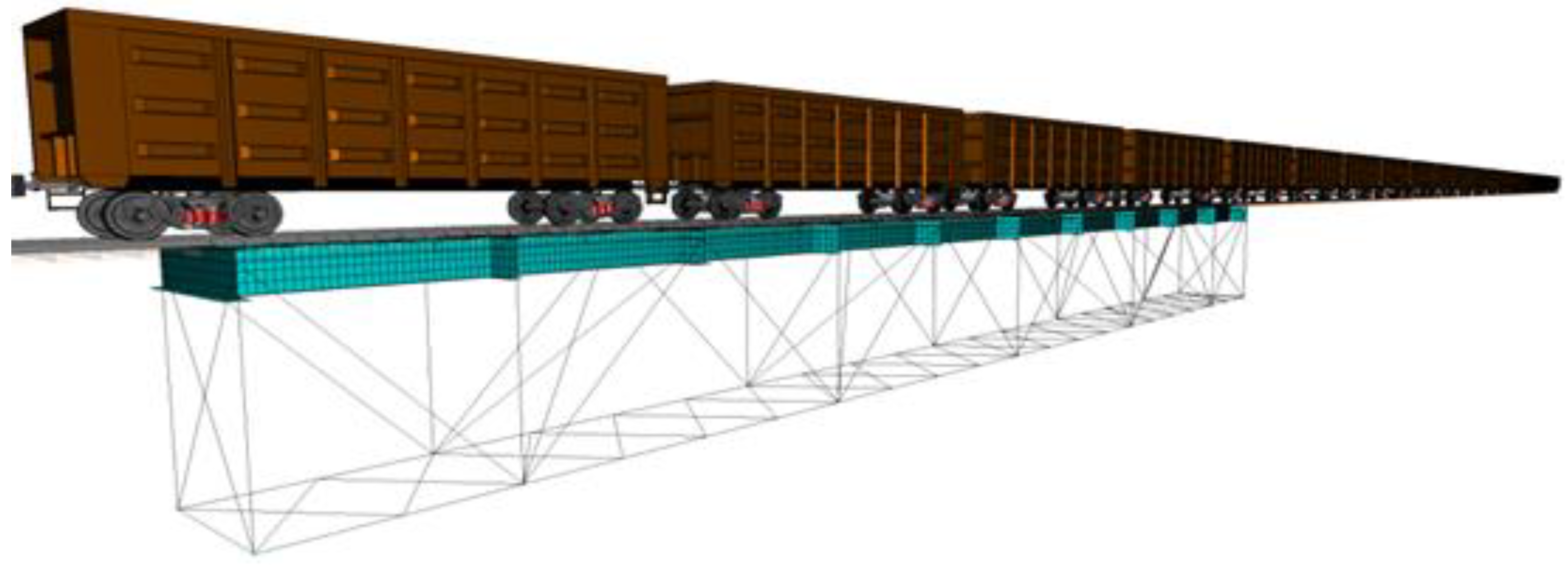

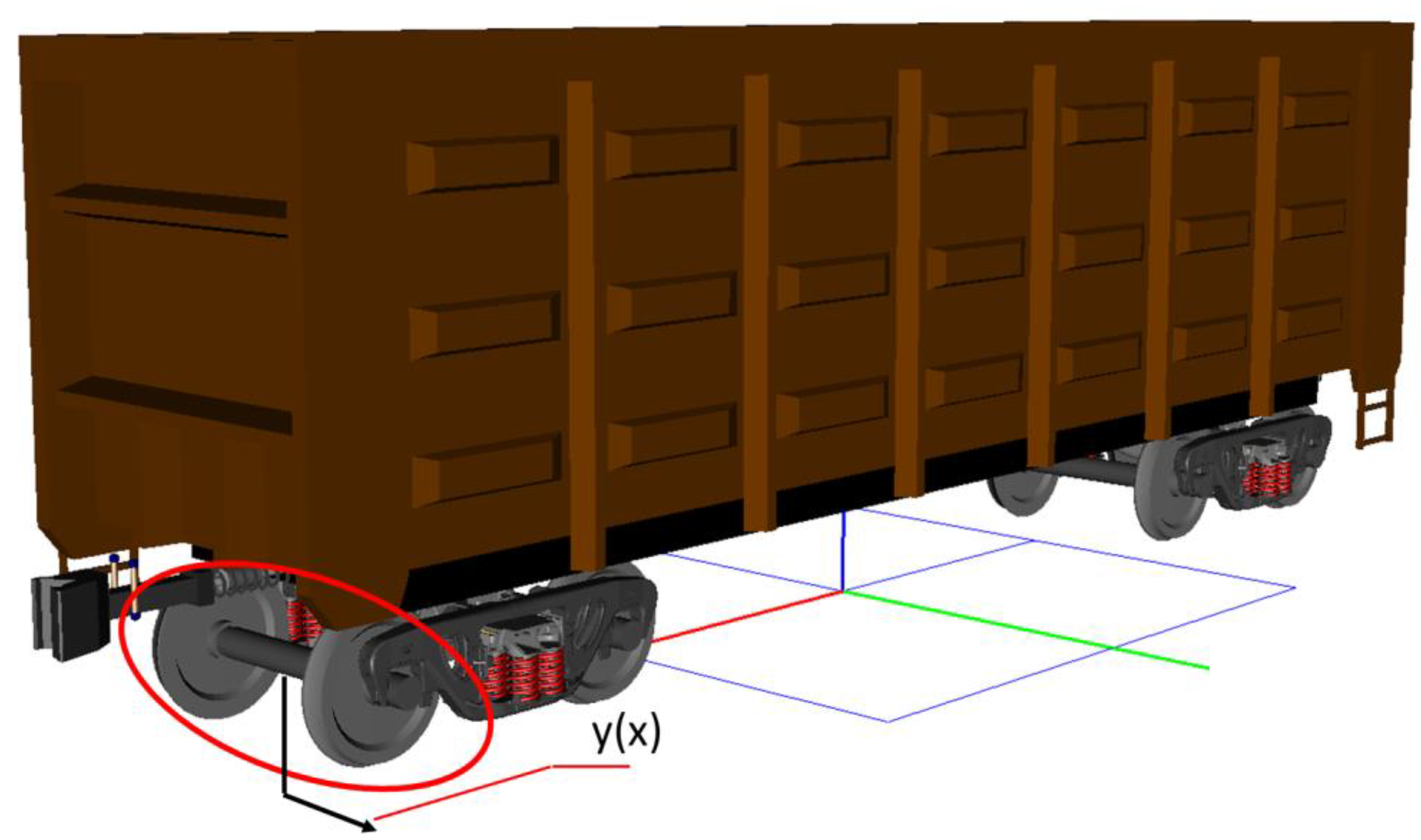

Figure 3.

Model of rolling stock.

Figure 3.

Model of rolling stock.

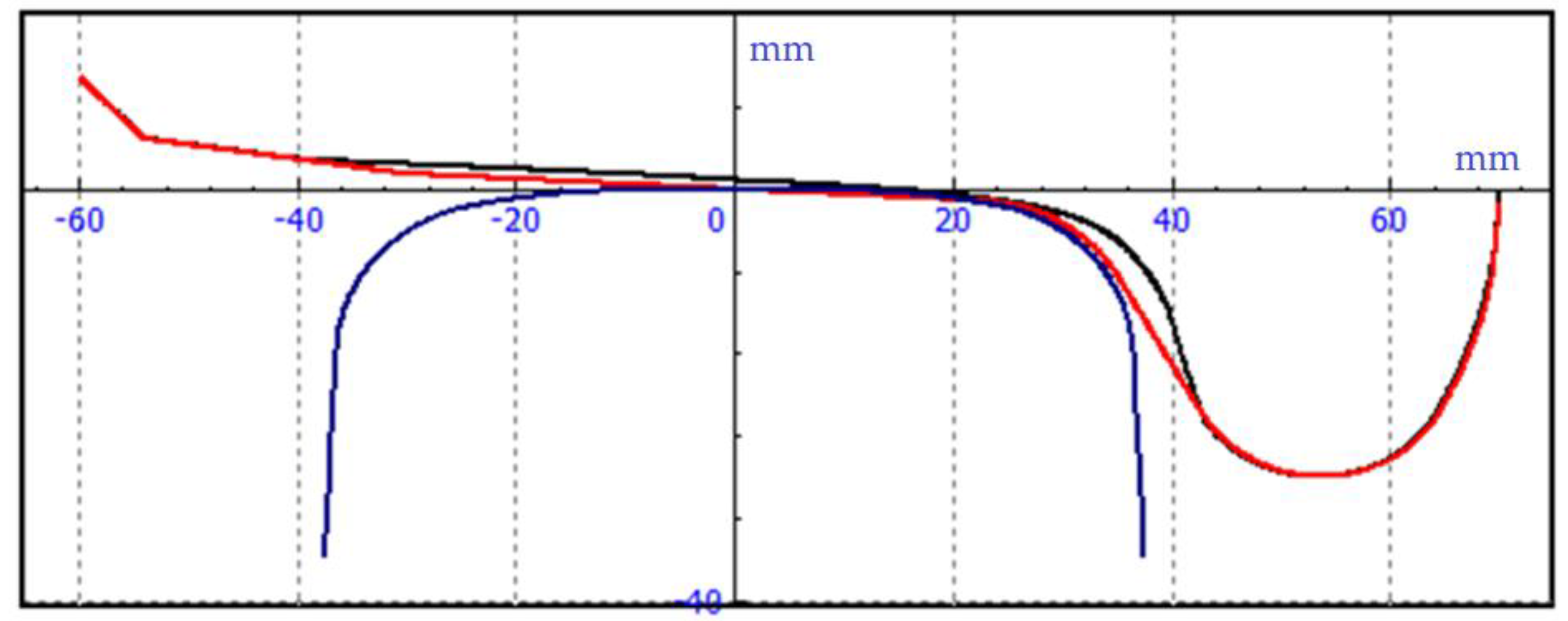

Figure 4.

Forms of car oscillations: upper lateral roll – on the left, bouncing – on the right.

Figure 4.

Forms of car oscillations: upper lateral roll – on the left, bouncing – on the right.

Figure 5.

New profile - red, worn profile - black.

Figure 5.

New profile - red, worn profile - black.

Figure 6.

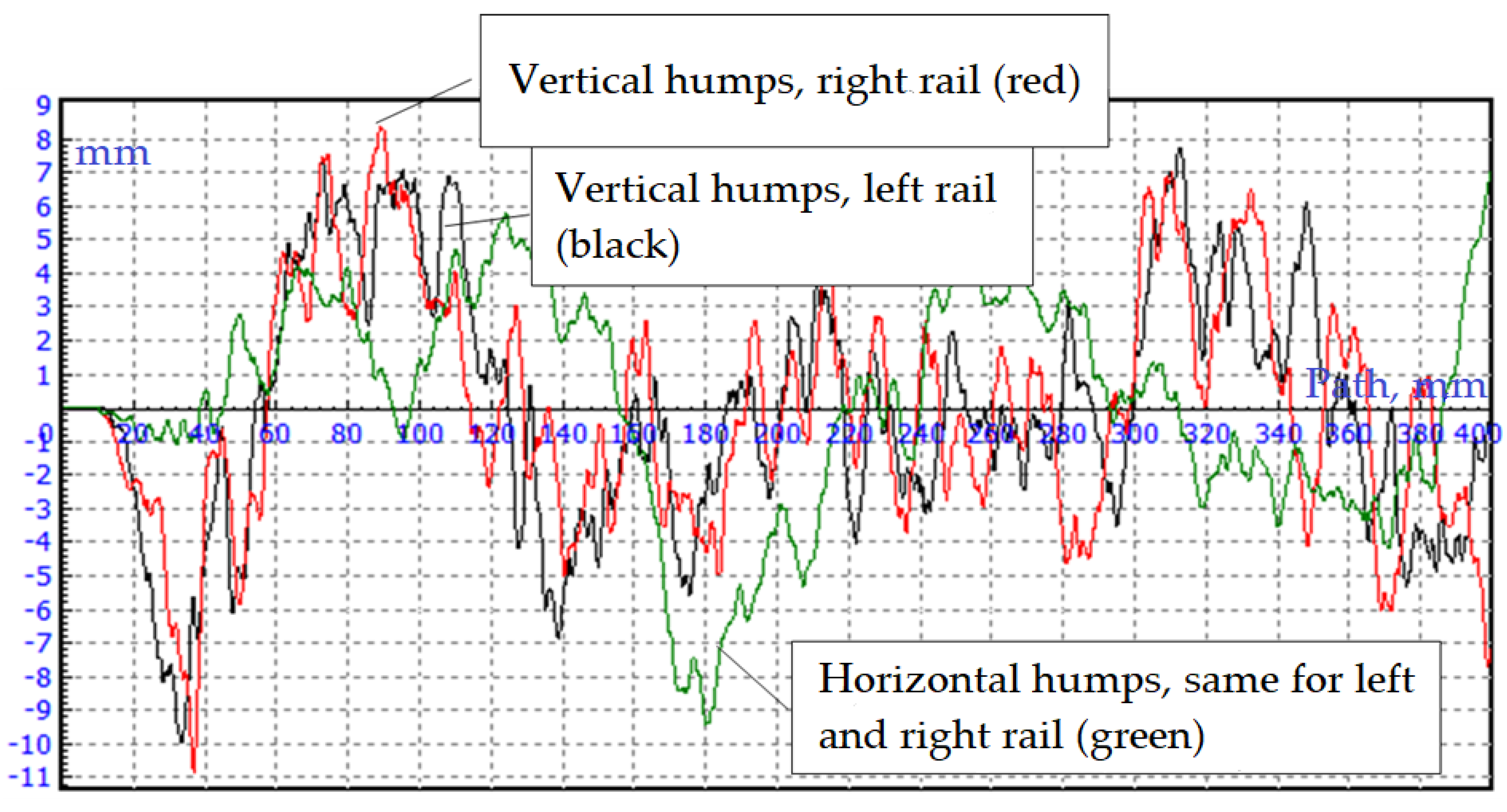

Imperfections of the path.

Figure 6.

Imperfections of the path.

Figure 7.

Vertical and horizontal imperfections of the track.

Figure 7.

Vertical and horizontal imperfections of the track.

Figure 8.

Recording point of oscillograms of the span structure vibrations.

Figure 8.

Recording point of oscillograms of the span structure vibrations.

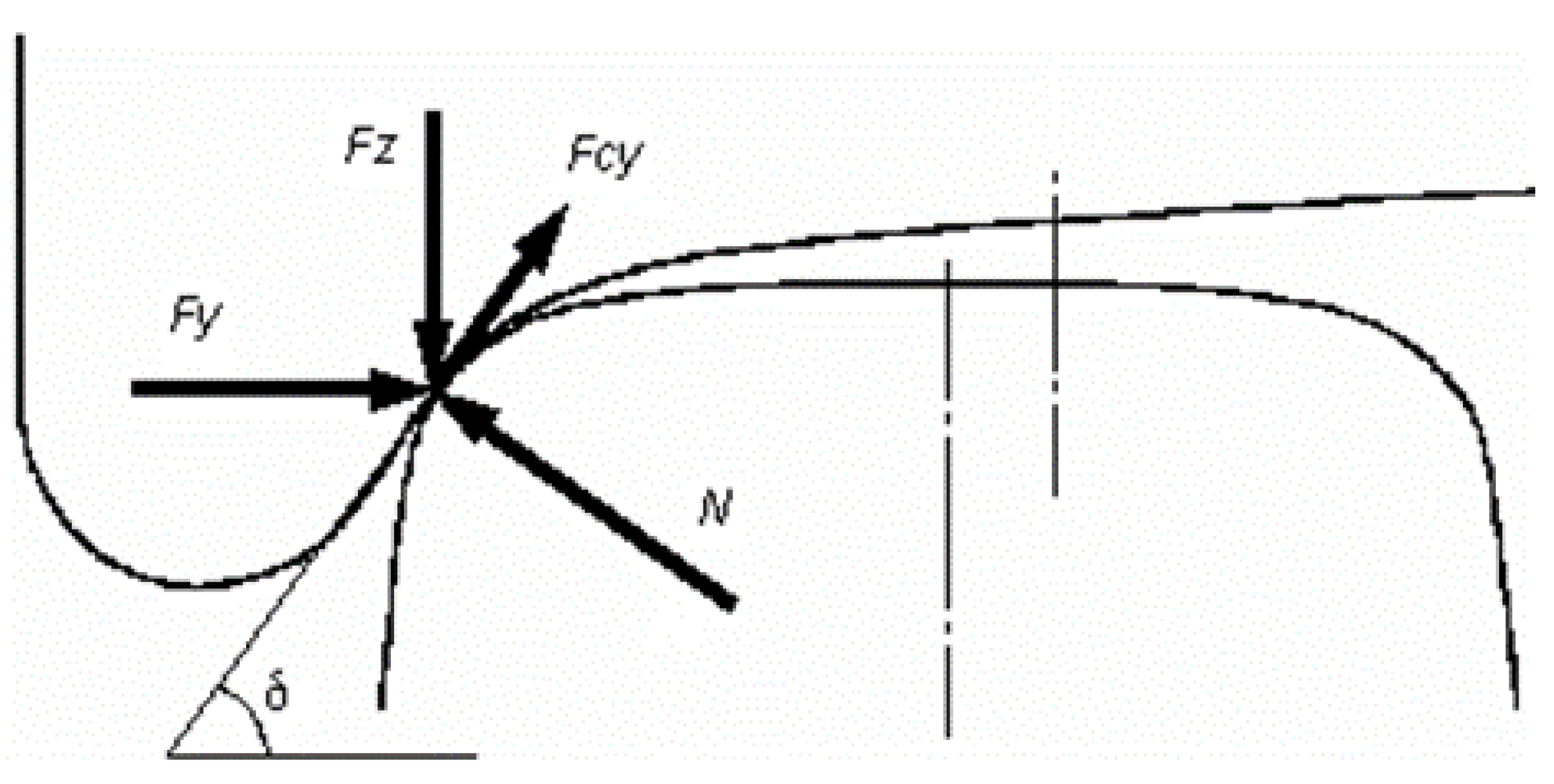

Figure 9.

Projection of forces in contact between the wheel flange and the rail on the transverse vertical plane at the moment of the start of derailment.

Figure 9.

Projection of forces in contact between the wheel flange and the rail on the transverse vertical plane at the moment of the start of derailment.

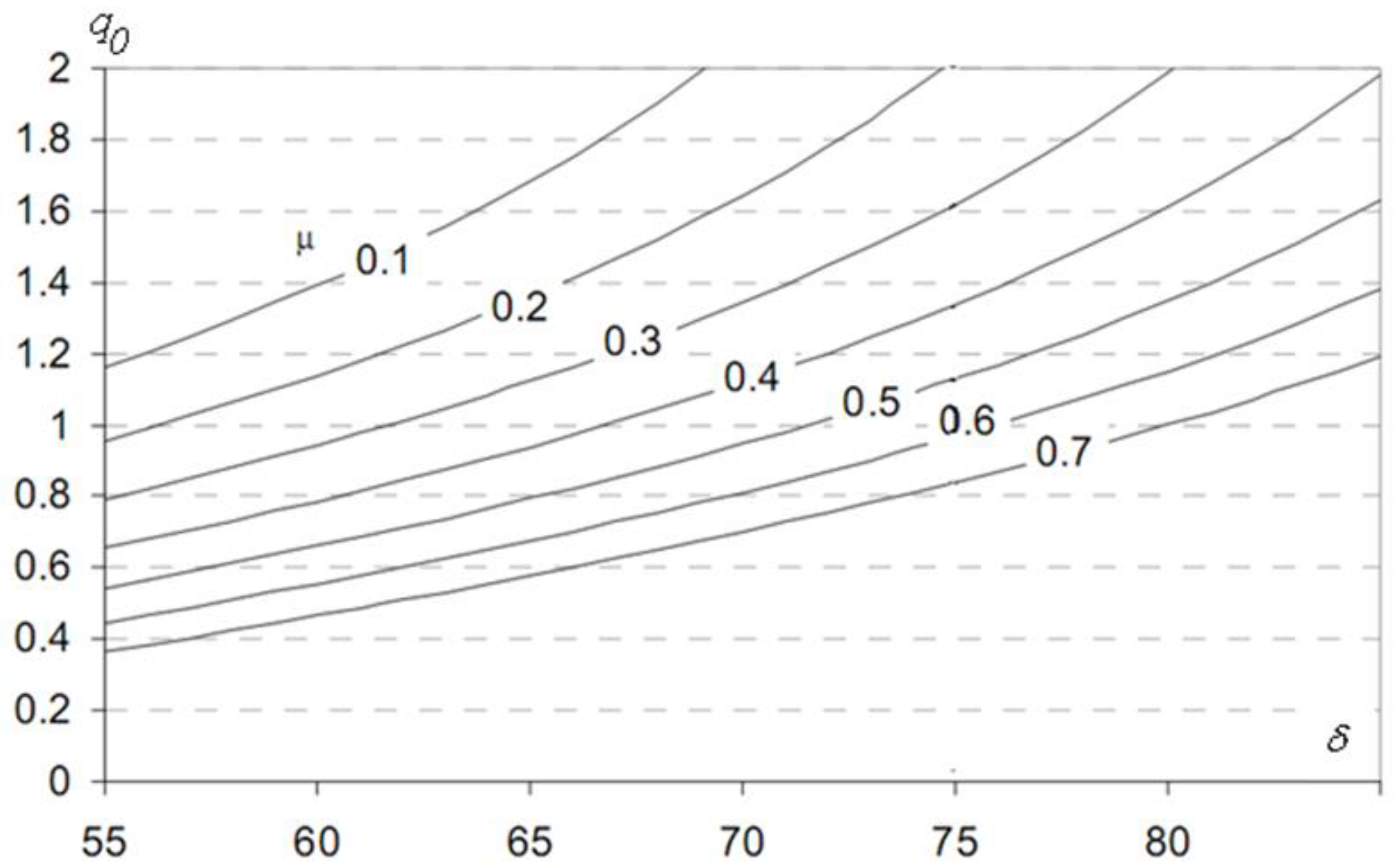

Figure 10.

Dependence of the limiting ratio according to the Nadal criterion on the comb inclination angle for different values of the friction coefficient.

Figure 10.

Dependence of the limiting ratio according to the Nadal criterion on the comb inclination angle for different values of the friction coefficient.

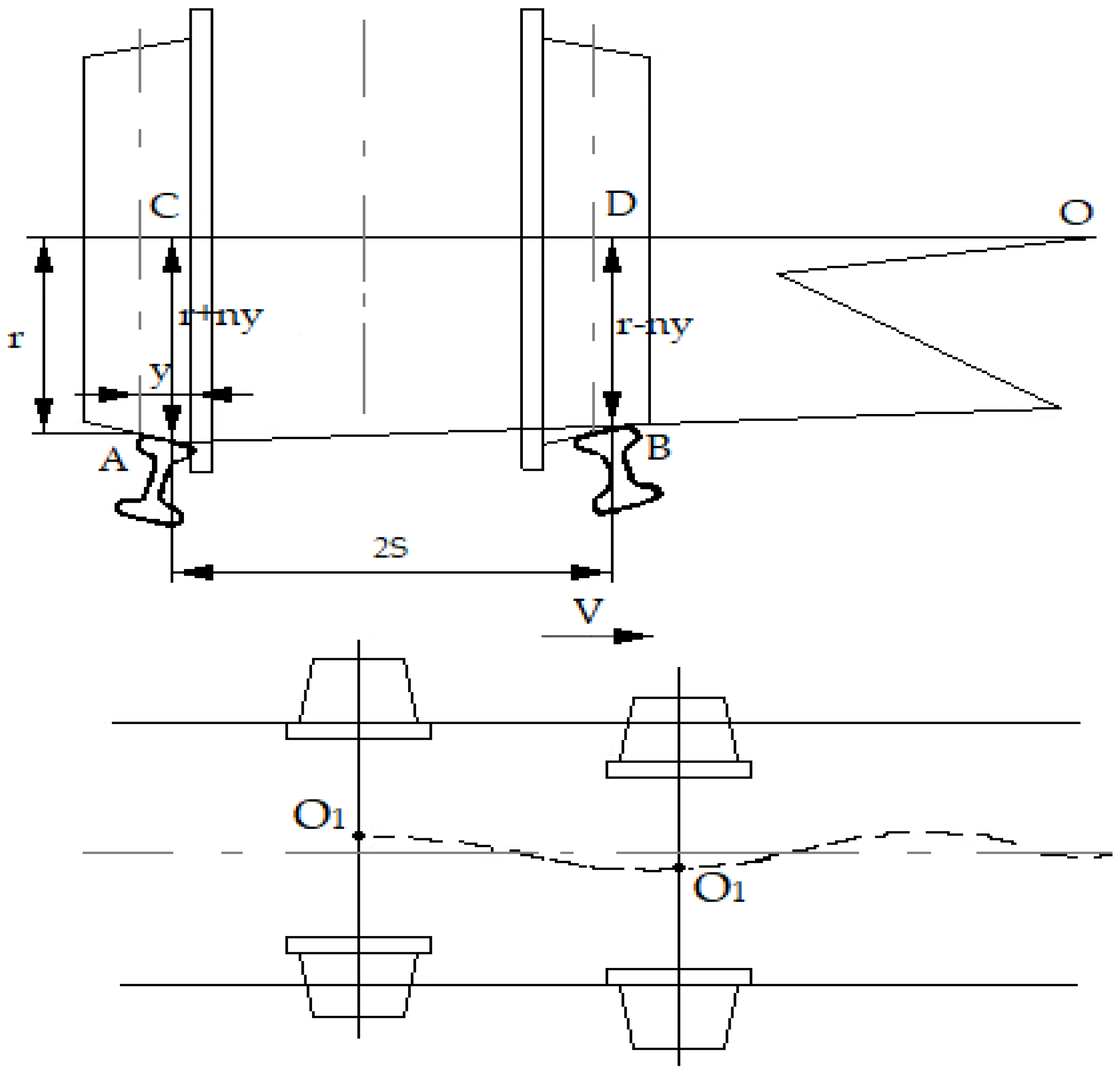

Figure 11.

Winding motion of a wheel pair.

Figure 11.

Winding motion of a wheel pair.

Figure 12.

Wheel pair for which transverse movements are recorded.

Figure 12.

Wheel pair for which transverse movements are recorded.

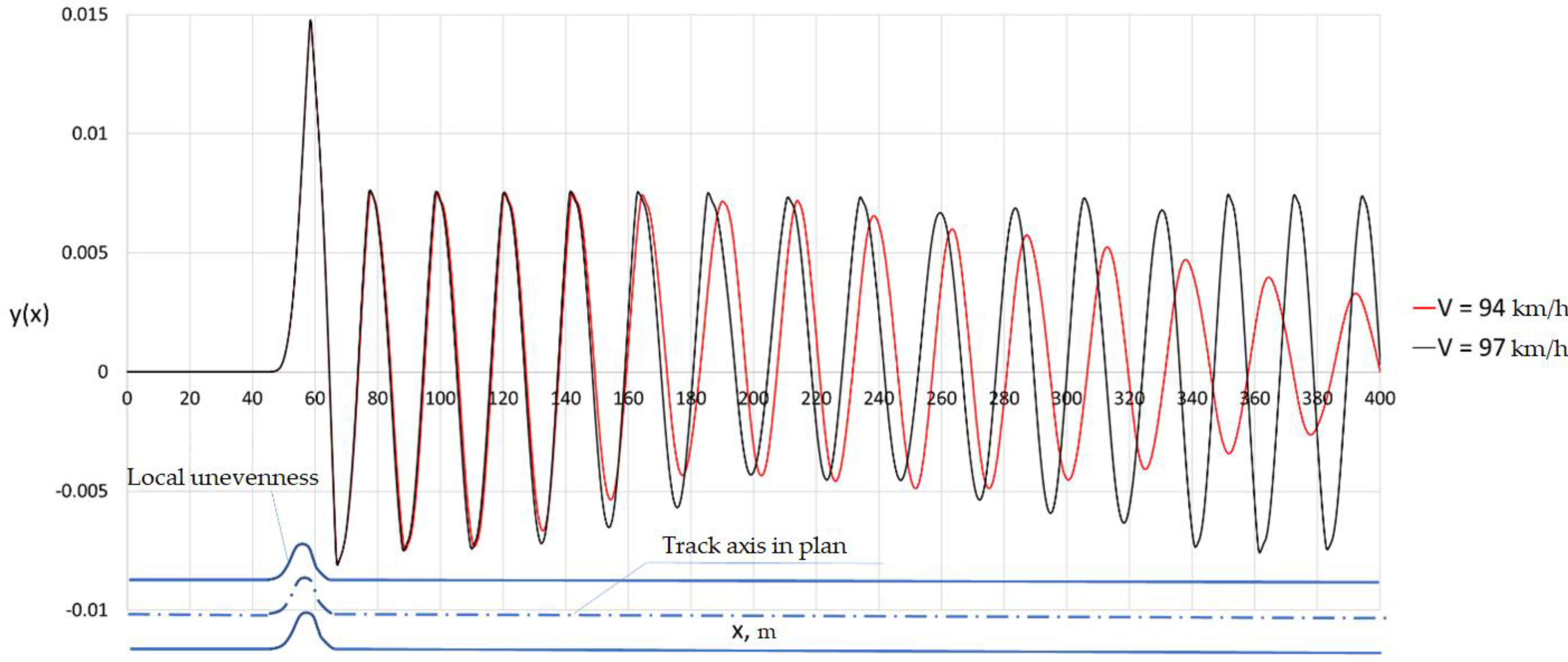

Figure 13.

Transverse displacements of the 1st wheel pair at subcritical and supercritical speeds. New wheels.

Figure 13.

Transverse displacements of the 1st wheel pair at subcritical and supercritical speeds. New wheels.

Figure 14.

Dependence of the amplitude of transverse vibrations in the middle of the span on the speed of the train.

Figure 14.

Dependence of the amplitude of transverse vibrations in the middle of the span on the speed of the train.

Figure 15.

Dependences of the maximum absolute and standard deviations of vertical and horizontal transverse accelerations in the middle of the span.

Figure 15.

Dependences of the maximum absolute and standard deviations of vertical and horizontal transverse accelerations in the middle of the span.

Figure 16.

Transverse vibrations in the middle of the span at a train speed of V = 90 km/h.

Figure 16.

Transverse vibrations in the middle of the span at a train speed of V = 90 km/h.

Figure 17.

Spectral power density of transverse oscillations.

Figure 17.

Spectral power density of transverse oscillations.

Figure 18.

Transverse forces Fy in the wheel-rail contact of car No. 23. Left wheel is red, right wheel is blue.

Figure 18.

Transverse forces Fy in the wheel-rail contact of car No. 23. Left wheel is red, right wheel is blue.

Figure 19.

Spectral density of transverse forces in the wheel-rail contact. Left wheel – red, blue – right wheel.

Figure 19.

Spectral density of transverse forces in the wheel-rail contact. Left wheel – red, blue – right wheel.

Figure 20.

Nadal criterion. Wheel pair No. 3. Car No. 6. Left wheel – blue, right wheel – grey, permissible value – red.

Figure 20.

Nadal criterion. Wheel pair No. 3. Car No. 6. Left wheel – blue, right wheel – grey, permissible value – red.

Figure 21.

Wheel-rail dynamic coefficient. Wheel pair No. 3. Car No. 6. Left wheel – blue, right wheel – gray, permissible value – red.

Figure 21.

Wheel-rail dynamic coefficient. Wheel pair No. 3. Car No. 6. Left wheel – blue, right wheel – gray, permissible value – red.

Figure 22.

Wheel-rail dynamic coefficient. Wheel pair No. 1. Car No. 2. Left wheel – blue, right wheel – grey, permissible value – red.

Figure 22.

Wheel-rail dynamic coefficient. Wheel pair No. 1. Car No. 2. Left wheel – blue, right wheel – grey, permissible value – red.

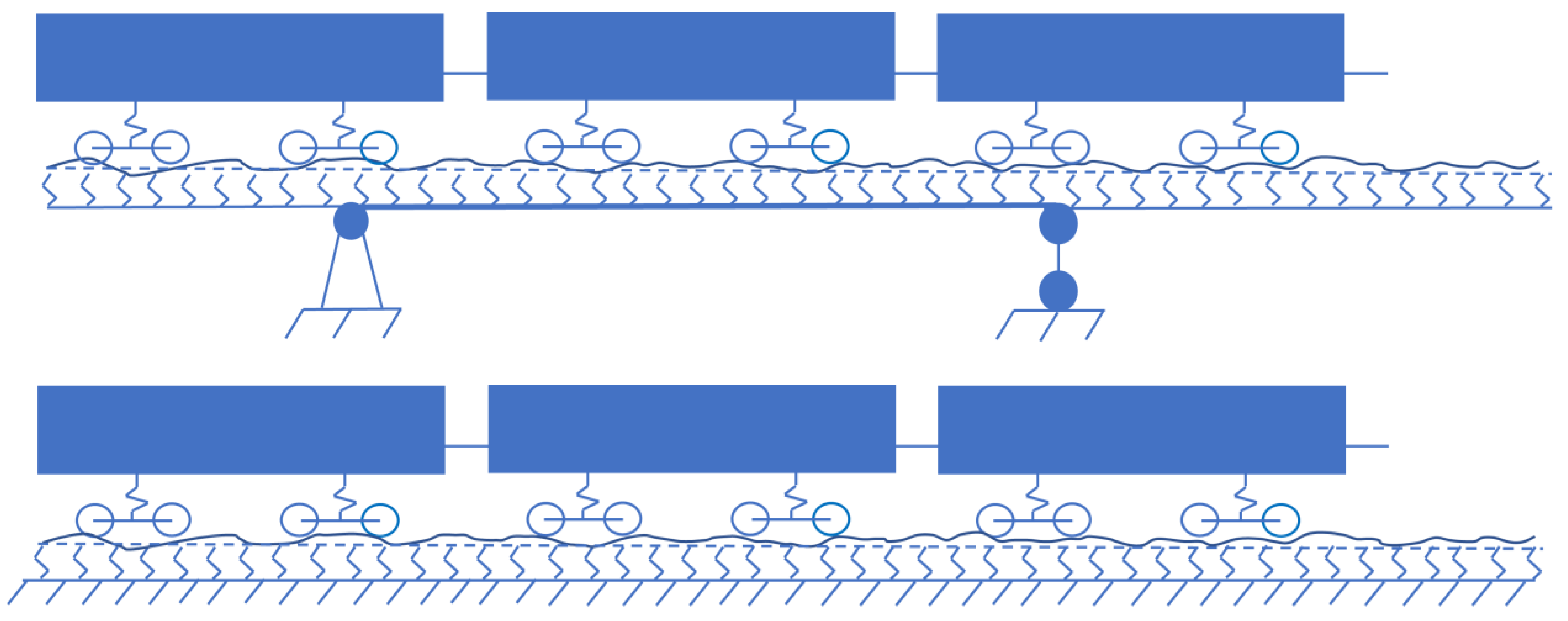

Figure 23.

Scheme of movement of rolling stock in calculations with and without the superstructure.

Figure 23.

Scheme of movement of rolling stock in calculations with and without the superstructure.

Figure 24.

Nadal criterion. Wheel pair No. 1. Car No. 5. Left wheel – gray. Permissible value – red.

Figure 24.

Nadal criterion. Wheel pair No. 1. Car No. 5. Left wheel – gray. Permissible value – red.

Figure 25.

Dependence of the maximum value of the Nadal criterion on the speed of the train.

Figure 25.

Dependence of the maximum value of the Nadal criterion on the speed of the train.

Figure 26.

Transverse horizontal vibrations of the span structure in the middle of the span.

Figure 26.

Transverse horizontal vibrations of the span structure in the middle of the span.

Figure 27.

Nadal criterion. Wheel pair No. 1. Car No. 9. Left wheel. Calculation with a span – blue, calculation without a span – grey, permissible value – red.

Figure 27.

Nadal criterion. Wheel pair No. 1. Car No. 9. Left wheel. Calculation with a span – blue, calculation without a span – grey, permissible value – red.

Figure 28.

Wheel-rail dynamic coefficient. Wheel pair No. 1. Car No. 9. Left wheel. Calculation with span structure – blue, calculation without span structure – grey, permissible value – red.

Figure 28.

Wheel-rail dynamic coefficient. Wheel pair No. 1. Car No. 9. Left wheel. Calculation with span structure – blue, calculation without span structure – grey, permissible value – red.

Table 2.

Vertical and horizontal accelerations of the span structure.

Table 2.

Vertical and horizontal accelerations of the span structure.

| V, km/h |

|

|

| Max|Az|, m/s2

|

σ_Az, m/s2

|

Max|Ay|, m/s2

|

σ_Ay, m/s2

|

| 40 |

0.243 |

0.052 |

0.211 |

0.047 |

| 50 |

0.352 |

0.078 |

0.298 |

0.069 |

| 60 |

0.522 |

0.111 |

0.633 |

0.102 |

| 70 |

0.574 |

0.138 |

1.137 |

0.207 |

| 80 |

1.135 |

0.254 |

2.008 |

0.344 |

| 90 |

1.247 |

0.265 |

2.329 |

0.607 |

| 100 |

2.258 |

0.451 |

3.721 |

0.662 |

| 110 |

2.639 |

0.496 |

4.997 |

0.917 |

| 120 |

3.431 |

0.741 |

7.174 |

1.264 |

Table 3.

Tests of the early 20th century.

Table 3.

Tests of the early 20th century.

| № |

Estimated span L m. |

Test train |

V, km/h |

Amplitude, mm |

| 1 |

54.88 |

2 locomotives + 2 freight cars |

57 |

7.5 |

| 42 |

5.0 |

| 64 |

9.0 |

| 2 |

55.1 |

2 steam locomotives + 4 freight platforms |

16 |

2.5 |

| 13 |

3.0 |

| 37 |

4.0 |

| 40 |

3.0 |

| 17 |

2.5 |

| 5 |

1.0 |

| 2 steam locomotives |

16 |

2.2 |

| 17 |

3.0 |

| 45 |

2.0 |

| 3 |

55.06 |

2 steam locomotives + 4 freight platforms |

5 |

2.0 |

| 16 |

2.5 |

| 13 |

2.2 |

| 37 |

2.5 |

| 40 |

3.0 |

| 2 steam locomotives |

6 |

1.8 |

| 17 |

2.5 |

| 40 |

5.5 |