Submitted:

03 September 2024

Posted:

04 September 2024

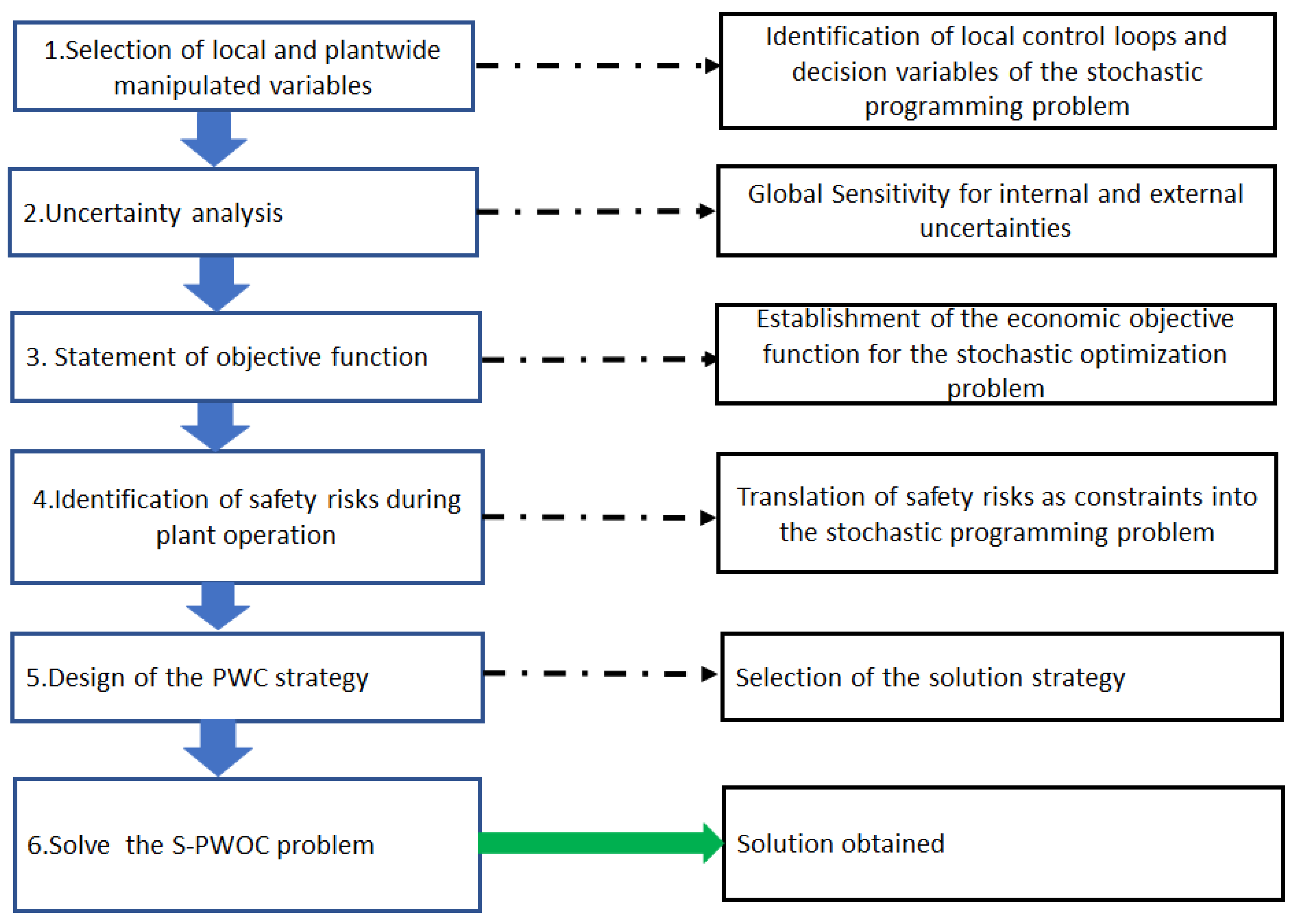

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Methods

2.1. Plantwide Control Methodologies

2.2. Stochastic Optimization

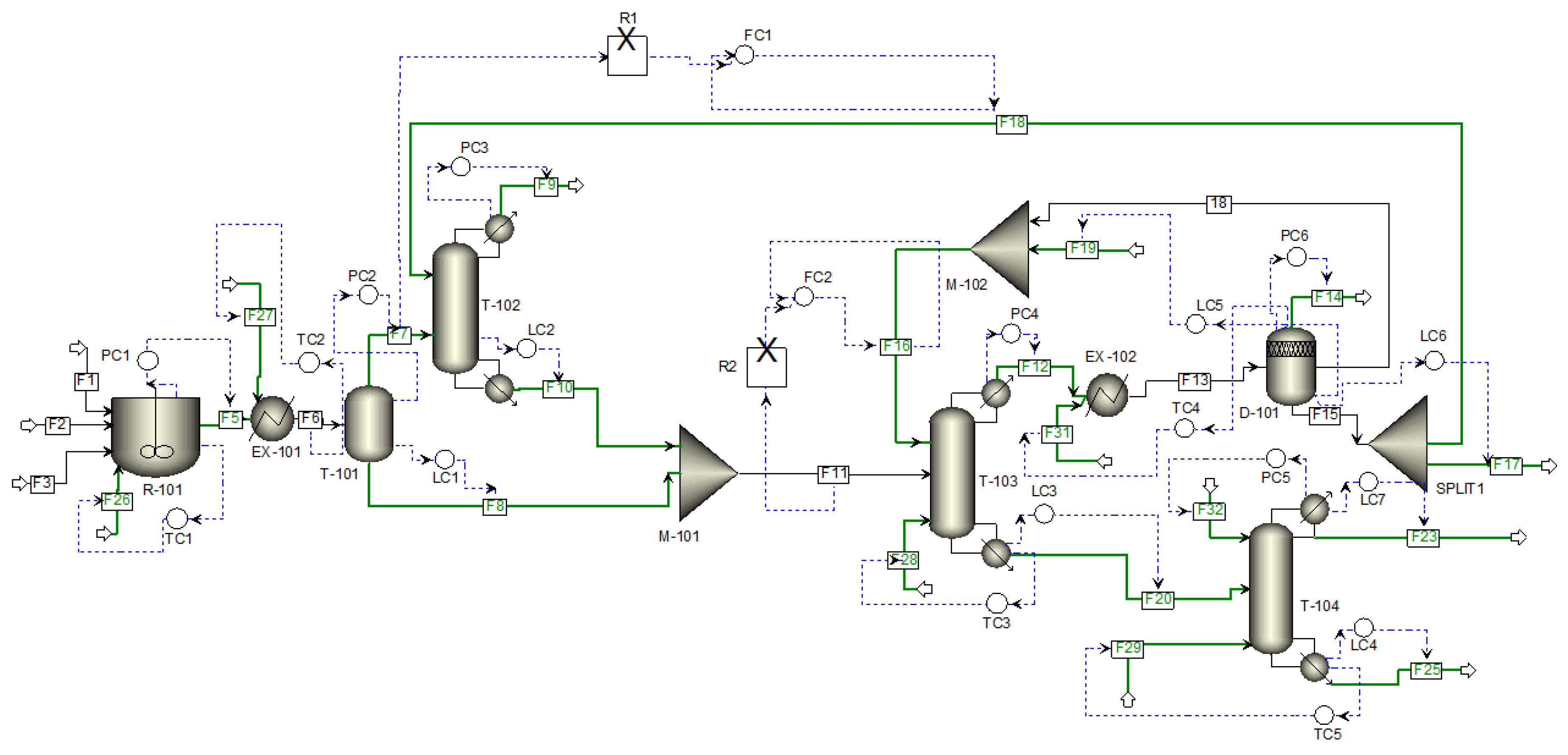

3. Acrylic Acid Process

3.1. Process Modeling and Simulation

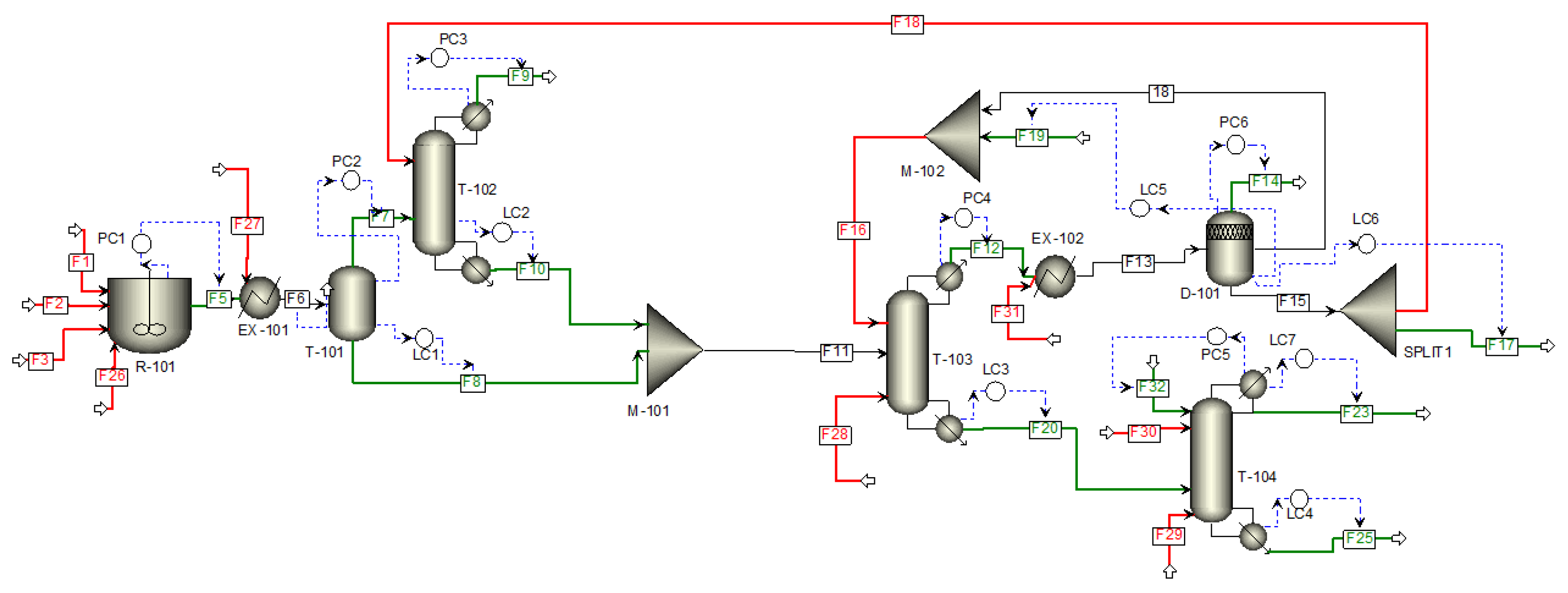

3.2. Safety Risks during Plant Operation

4. Stochastic Optimization of Acrylic Acid Production: Managing Uncertainties in Plantwide Control

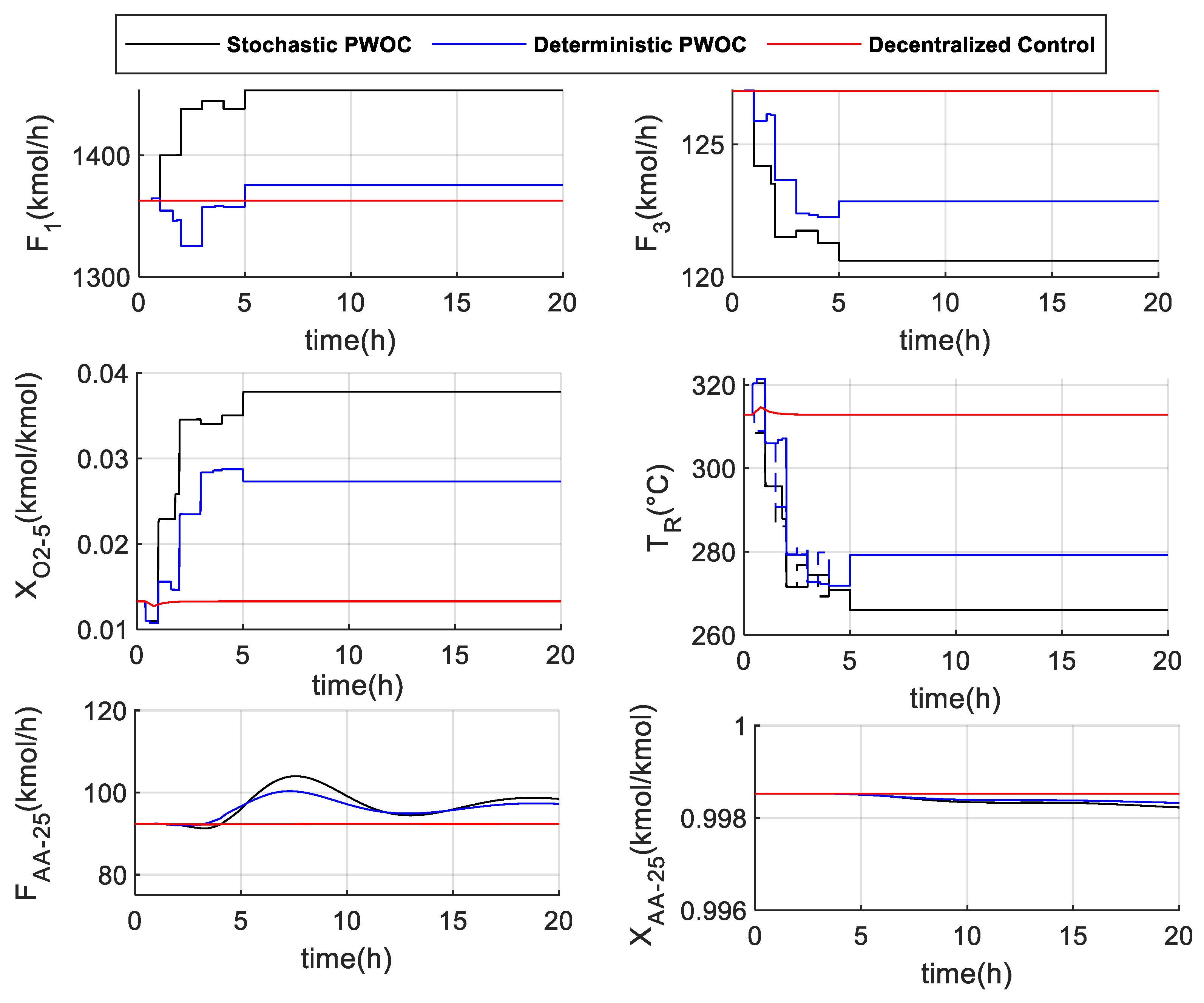

5. S-PWOC for the Acrylic Acid Process: Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Juliani Correa de Godoy, R.; Garcia, C. Plantwide Control: A Review of Design Techniques, Benchmarks, and Challenges. Ind Eng Chem Res 2017, 56, 7877–7887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Shang, S. Managing Uncertainty in AI-Enabled Decision Making and Achieving Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia, S.; Andersson, J.A.E.; Brandt, H.; Diehl, M.; Engell, S. Handling Uncertainty in Economic Nonlinear Model Predictive Control: A Comparative Case Study. J Process Control 2014, 24, 1247–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, S.; Wozny, G.; Repke, J.U. Plantwide Optimizing Control of a Continuous Bioethanol Production Process. In Journal of Process Control; 2010; Vol. 20, pp 983–998. [CrossRef]

- Duque, A.; Ochoa, S.; Odloak, D. Stochastic Multilayer Optimization for an Acrylic Acid Reactor. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 26150–26169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- globenewswire.com.

- ICIS.com web site. https://www.icis.com/explore/.

- Jean-Paul Lange. Production of Acrylic Acid. 2015035 3465, 2016.

- Murthy Konda, N.V.S.N.; Rangaiah, G.P.; Krishnaswamy, P.R. Plantwide Control of Industrial Processes: An Integrated Framework of Simulation and Heuristics. Ind Eng Chem Res 2005, 44, 8300–8313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangaiah, G.P.; Kariwala, V. Plantwide Control: Recent Developments and Applications; John Wiley and Sons Ltd, Ed.; United Kingdom, 2012.

- Buckley, P.S. Techniques of Process Control; Wiley, Ed.; New York, 1964.

- Scattolini, R. Architectures for Distributed and Hierarchical Model Predictive Control - A Review. J Process Control 2009, 19, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, J.B.; Stewart, B.T. Coordinating Multiple Optimization-Based Controllers: New Opportunities and Challenges. J Process Control 2008, 18, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, S.; Wozny, G.; Repke, J.U. Plantwide Optimizing Control of a Continuous Bioethanol Production Process. In Journal of Process Control; Elsevier, 2010; Vol. 20, pp 983–998. [CrossRef]

- Pataro, I.M.L.; da Costa, M.V.A.; Joseph, B. Closed-Loop Dynamic Real-Time Optimization (CL-DRTO) of a Bioethanol Distillation Process Using an Advanced Multilayer Control Architecture. Comput Chem Eng 2020, 143, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, A.; Kaisare, N.S. A Multi-Objective Dynamic RTO for Plant-Wide Control. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Rodelo, K.; Francisco, M.; Alvarez, H.; Vega, P.; Revollar, S. Collaborative Control Applied to BSM1 for Wastewater Treatment Plants. Processes. [CrossRef]

- Ravi, A.; Kaisare, N.S. Two-Layered Dynamic Control for Simultaneous Set-Point Tracking and Improved Economic Performance. J Process Control 2021, 97, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahi, E.; Krishnamoorthy, D.; Codas, A.; Foss, B.; Skogestad, S. Plantwide Control of an Oil Production Network. Comput Chem Eng 2020, 136, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujiyanti, S.F.; Biyanto, T.R.; Pratama, I.P.E.W.; Kurniawan, I.A. The Control Design Optimization of Gas Processing Plant Based on Plantwide Control Method. AIP Conf Proc 2023, 2580, 40014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engell, S. Feedback Control for Optimal Process Operation. J Process Control 2007, 17, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricker, N.L. and Lee, J.H. Non-Linear Model-Predictive Control of the Tennessee Eastman Challenge Process. Comput Chem Eng 1995, 19, 961–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aske, E.M.B.; Skogestad, S. Consistent Inventory Control. Ind Eng Chem Res 2008, 48, 10892–10902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assali, W.A. and McAvoy, T. Optimal Selection of Dominant Measurements and Manipulated Variables for Production Control. Ind Eng Chem Res 2010, 49, 7832–7842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, J.; Vazquez, F.; Morilla, F. Centralized Multivariable Control by Simplified Decoupling. J Process Control 2012, 22, 1044–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, A.; Ochoa, S. Dynamic Optimization for Controlling an Acrylic Acid Process. In 2017 IEEE 3rd Colombian Conference on Automatic Control, CCAC 2017 - Conference Proceedings; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2017; Vol. 2018-Janua, pp 1–6. [CrossRef]

- G. E. P. Box. Robustness in the Strategy of Scientific Model Building, 1979.

- Li, P.; Wendt, M.; Wozny, G. Optimal Production Planning for Chemical Processes under Uncertain Market Conditions. Chem Eng Technol 2004, 27, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navia, D.; Sarabia, D.; Gutiérrez, G.; Cubillos, F.; de Prada, C. A Comparison between Two Methods of Stochastic Optimization for a Dynamic Hydrogen Consuming Plant. Comput Chem Eng 2014, 63, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia, S.; Finkler, T.; Engell, S. Multi-Stage Nonlinear Model Predictive Control Applied to a Semi-Batch Polymerization Reactor under Uncertainty. J Process Control 2013, 23, 1306–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.; Illner, M.; Esche, E.; Pogrzeba, T.; Schmidt, M.; Schomäcker, R.; Biegler, L.T.; Wozny, G.; Repke, J.-U. Dynamic Real-Time Optimization under Uncertainty of a Hydroformylation Mini-Plant. Comput Chem Eng 2017, 106, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Cremer, J.L.; Grossmann, I.E.; Sundaramoorthy, A.; Pinto, J.M. Risk-Based Integrated Production Scheduling and Electricity Procurement for Continuous Power-Intensive Processes. Comput Chem Eng 2016, 86, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Cremaschi, S. Multistage Stochastic Models for Shale Gas Artificial Lift Infrastructure Planning. In 13 International Symposium on Process Systems Engineering (PSE 2018); Eden, M.R., Ierapetritou, M.G., Towler, G.P.B.T.-C. A. C. E., Eds.; Elsevier, 2018; Vol. 44, pp 1285–1290. [CrossRef]

- Al-Aboosi, F.Y.; El-Halwagi, M.M. A Stochastic Optimization Approach to the Design of Shale Gas/Oil Wastewater Treatment Systems with Multiple Energy Sources under Uncertainty. Sustainability. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, M.; Jiang, H.; Yuan, Z.; Chen, B. Optimal Design and Operation of Refinery Hydrogen Systems under Multi-Scale Uncertainties. Comput Chem Eng 2020, 138, 106822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petsagkourakis, P.; Sandoval, I.O.; Bradford, E.; Galvanin, F.; Zhang, D.; Rio-Chanona, E.A. del. Chance Constrained Policy Optimization for Process Control and Optimization. J Process Control 2022, 111, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Singh, V.P.; Ebrahimnejad, A.; Chakraborty, D. Solving a Multi-Objective Chance Constrained Hierarchical Optimization Problem under Intuitionistic Fuzzy Environment with Its Application. Expert Syst Appl 2023, 217, 119595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Grossmann, I.E. A Review of Stochastic Programming Methods for Optimization of Process Systems Under Uncertainty. Frontiers in Chemical Engineering 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turton, R.; Bailie, R.C.; Whiting, W.B.; Shaeiwitz, J.A.; Bhattacharyya, D. Analysis, Synthesis, and Design of Chemical Processes, Fouth.; Prentice Hall, Ed.; New York:, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Suo, X.; Zhang, H.; Ye, Q.; Dai, X.; Yu, H.; Li, R. Design and Control of an Improved Acrylic Acid Process. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2015, 104, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyben, W.L. Economic Trade-Offs in Acrylic Acid Reactor Design. Comput Chem Eng 2016, 93, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyben, W.L. Integrator / Deadtime Processes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res 1996, 35, 3480–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyben, W.L. Tuning Proportional - Integral Controllers for Processes with Both Inverse Response and Deadtime. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res 2000, 39, 973–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, S.; Wozny, G.; Repke, J.-U. Plantwide Optimizing Control of a Continuous Bioethanol Production Process. J Process Control 2010, 20, 983–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, P.S. Techniques of Process Control. 1964.

- Shinskey, F.G. Distillation Control: For Productivity and Energy Conservation, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill, Ed.; New York, 1984.

- Douglas, J.M. Conceptual Design of Chemical Processes; McGraw-, Hill, Eds.; New York, 1988.

- Downs, J.J. Distillation Control in a Plantwide Control Environment. In Practical Distillation Control; Springer, New York, NY, 1992; pp 413–439. [CrossRef]

- Luyben, W.L.; Tyréus, B.D.; Luyben, M.L. Plantwide Process Control; McGraw-Hill, 1998.

- Luyben, M.L.; Tyreus, B.D.; Luyben, W.L. Plantwide Control Design Procedure. AIChE Journal 1997, 43, 3161–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganzer, G.; Freund, H. Kinetic Modeling of the Partial Oxidation of Propylene to Acrolein: A Systematic Procedure for Parameter Estimation Based on Non-Isothermal Data. Industrial and Engineering Chemistry Research 2019, 58, 1857–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engell, S. Online Optimizing Control: The Link between Plant Economics and Process Control. In Computer Aided Chemical Engineering; Elsevier B.V., 2009; Vol. 27, pp 79–86. [CrossRef]

- Lucia, S. Robust Multi-Stage Nonlinear Model Predictive Control, Dortmund, 2015.

- López, D.A.N. Handling Uncertainties in Process Optimization, Valladolid University, 2012.

- Martí, R.; Lucia, S.; Sarabia, D.; Paulen, R.; Engell, S. Improving Scenario Decomposition Algorithms for Robust Nonlinear Model Predictive Control. Computers and Chemical Engineering 2015, 79, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, E.; Reble, M.; Bouaswaig, A.; Imsland, L. Economic Stochastic Nonlinear Model Predictive Control of a Semi-Batch Polymerization Reaction. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirunavukkarasu, M.; Sawle, Y.; Lala, H. A Comprehensive Review on Optimization of Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems Using Various Optimization Techniques. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 176, 113192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockafellar, R.T. Optimization under Uncertainty; University of Washington: Washington, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wendt, M.; Li, P.; Wozny, G. Nonlinear Chance-Constrained Process Opti-Mization under Uncertainty. Ind Eng Chem Res 2002, 41, 3621–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louveaux, F.; Birge, J.R. Introduction to Stochastic Programming., Second Edi.; Springer: New York, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Manipulated Variables at Local Level | Manipulated variables at Plantwide level |

|---|---|

| Liquid flowrate (F8) for controlling liquid level in flash(V-101) | Flowrate of air at reactor inlet |

| Liquid flowrate(F10) for controlling liquid level in absorber(T-101) | Flowrate of propylene at reactor inlet |

| Liquid steam (F20) to control the liquid level in the azeotropic column (T-102) | Steam flowrate at the reactor inlet |

| Liquid steam (F25) to control the liquid level in the rectification column(T-103) | Reactor utility flowrate |

| Liquid steam (F19) to control the liquid organic level in decanter(D-101) | Heat exchanger E-101 utility fluid flowrate |

| Liquid steam (F17) to control the liquid water level in decanter(D-101) | Heat exchanger E-102 utility fluid flowrate |

| Liquid steam of distillate (F23) to control the liquid level for reflux drum (V-102) in rectification column | Steam of aqueous phase recycled into the absorber column |

| Vapor steam (F5) to control the pressure in the reactor (R-101) | Steam of organic phase recycled into the azeotropic column |

| Vapor steam (F7) to control the pressure in flash drum (V-101) | Steam of utility fluid in the reboiler azeotropic column |

| Vapor flowrate (F9) for controlling pressure in absorber (T-101) | Reflux rate in the rectification column |

| Vapor flowrate(F12) for controlling pressure in azeotropic column(T-102) | Flowrate of utility fluid used in reboiler rectification column |

| Utility fluid flowrate(F32) used in E-105 heat exchanger for controlling pressure in rectification column(T-103) | |

| Vapor flowrate(F14) for controlling pressure in decanter(D-101) |

| Description | EA1 (kJ/kmol) | Profit (USD/h) | EA2 (kJ/kmol) | Profit (USD/h) | EA3 (kJ/kmol) | Profit (USD/h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | 13927,02 | 12300,00 | 16718,90 | 4537,30 | 18602,80 | 4664,50 |

| Nominal Value | 15000,00 | 9248,20 | 20000,00 | 9248,20 | 25000,00 | 9248,20 |

| Upper Limit | 16072,97 | 1186,70 | 23281,07 | 9769,20 | 30397,20 | 10680,54 |

| Average | 15000,00 | 7578,30 | 19999,99 | 7851,57 | 24666,67 | 8197,75 |

| Slope | -5,18 | 0,80 | 0,52 | |||

| Global sensitivity index | 10,25 | 2,03 | 1,55 |

| Description | k01 (kJ/kmol. s) |

profit (USD/h) |

k02 (kJ/kmol. s) | profit (USD/h) | k03 (kJ/kmol. s) |

profit (USD/h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | 3,09E-05 | 8679,82 | 1,72E-04 | 10591,45 | 0,04 | 11524,28 |

| Nominal Value | 4,42E-05 | 9248,20 | 2,45E-04 | 9248,20 | 0,05 | 9248,20 |

| Upper Limit | 5,74E-05 | 11510,91 | 3,19E-04 | 10363,33 | 0,07 | 9475,43 |

| Average | 4,42E-05 | 9812,98 | 2,45E-04 | 10067,66 | 0,05 | 10082,64 |

| Slope | 106752654,31 | -1513891,22 | -67842,72 | |||

| Global sensitivity index | 0,48 | 0,04 | 0,34 |

| Description | AAprice (USD/kmol) | Profit (USD/h) | ACEprice (USD/kmol) |

Profit (USD/h) |

C3H6price (USD/kmol) | Profit (USD/h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | 121,233 | 4382,7 | 62,958 | 9094,6 | 38,9130 | 11402,5 |

| Nominal Value | 173 | 9248,2 | 89,94 | 9248,2 | 55,59 | 9248,2 |

| Upper Limit | 225,147 | 14222,5 | 116,922 | 9473,8 | 72,267 | 7166,2 |

| Average | 173,216 | 9284,47 | 89,949 | 9272,20 | 55,59 | 9272,30 |

| Slope | 0,02 | 1,81E-03 | 7,90E-03 | |||

| Global sensitivity index | 0,25 | 0,01 | 0,13 |

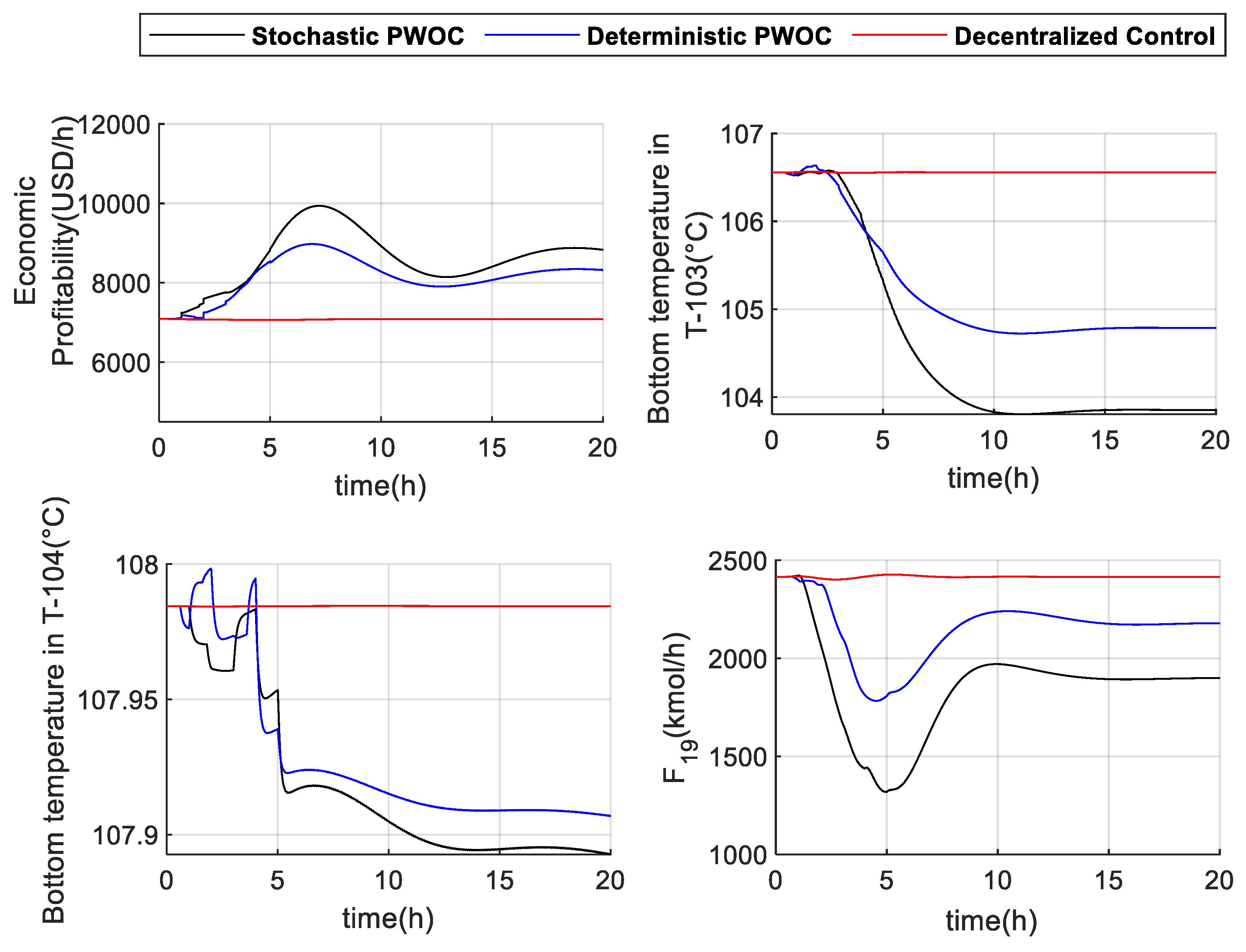

| Tested Architecture. | Cumulative Profitability (USD) |

|---|---|

| Stochastic PWOC approach | 1.7166 x105 |

| Deterministic PWOC approach | 1.6274 x105 |

| Decentralized PWC approach | 1.4158 x105 |

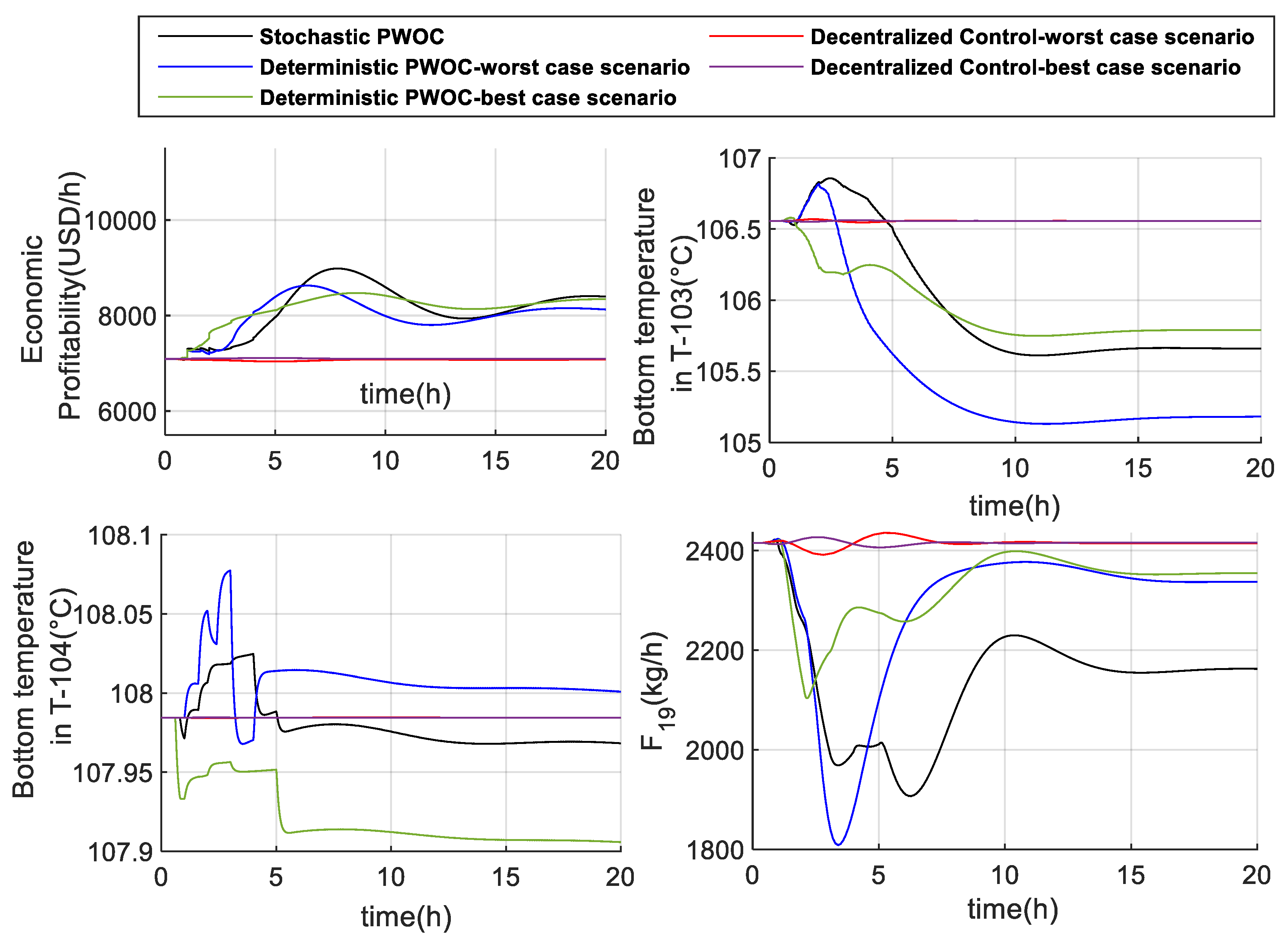

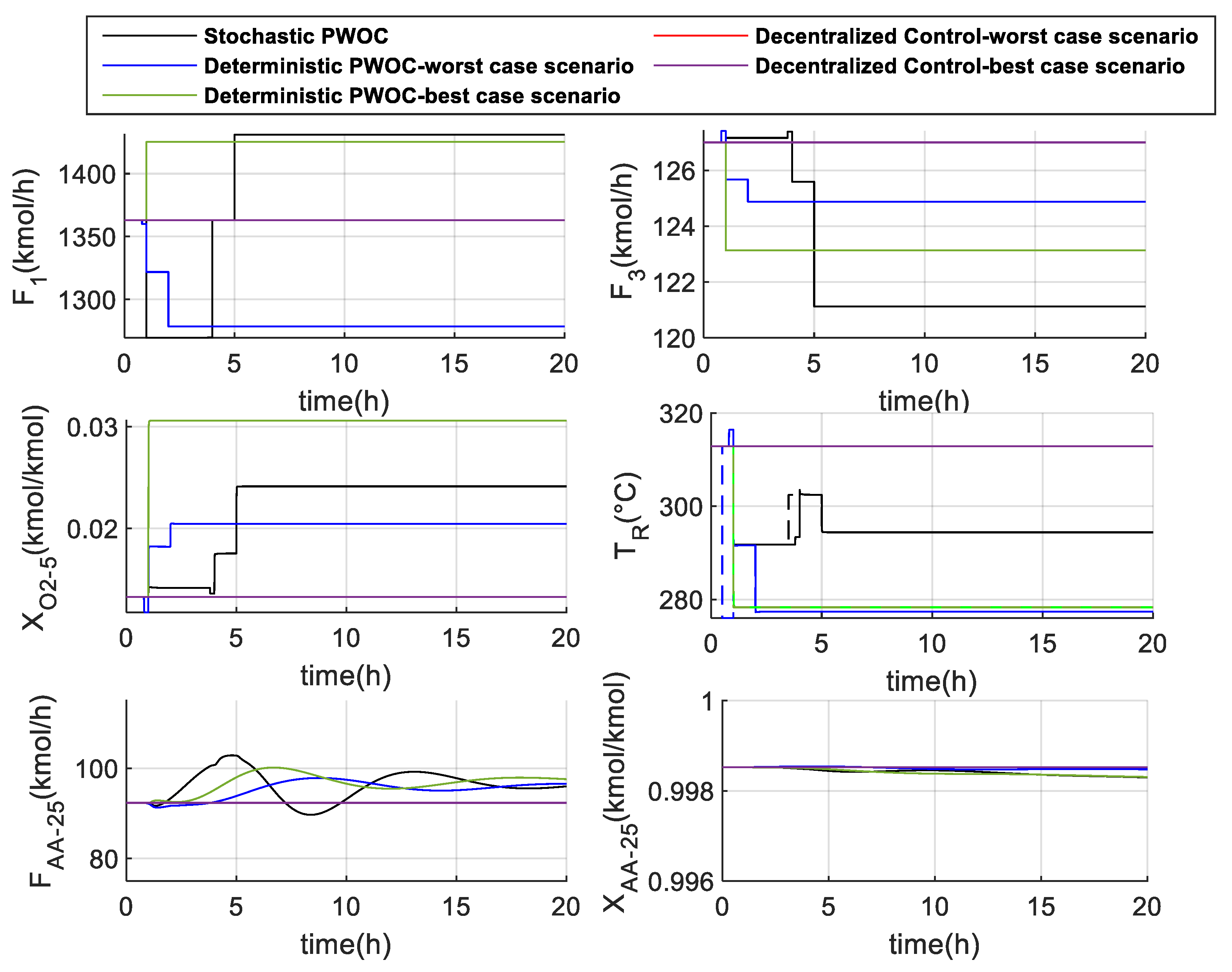

| Tested Architecture | Cumulative Profitability (USD) |

|---|---|

| Stochastic PWOC approach | 1.6243x105 |

| Deterministic PWOC approach best case- scenario |

1.6259x105 |

| Deterministic PWOC approach worst-case scenario |

1.5966x105 |

| Decentralized Control worst-case scenario |

1.4139x105 |

| Decentralized Control best-case scenario |

1.4198x105 |

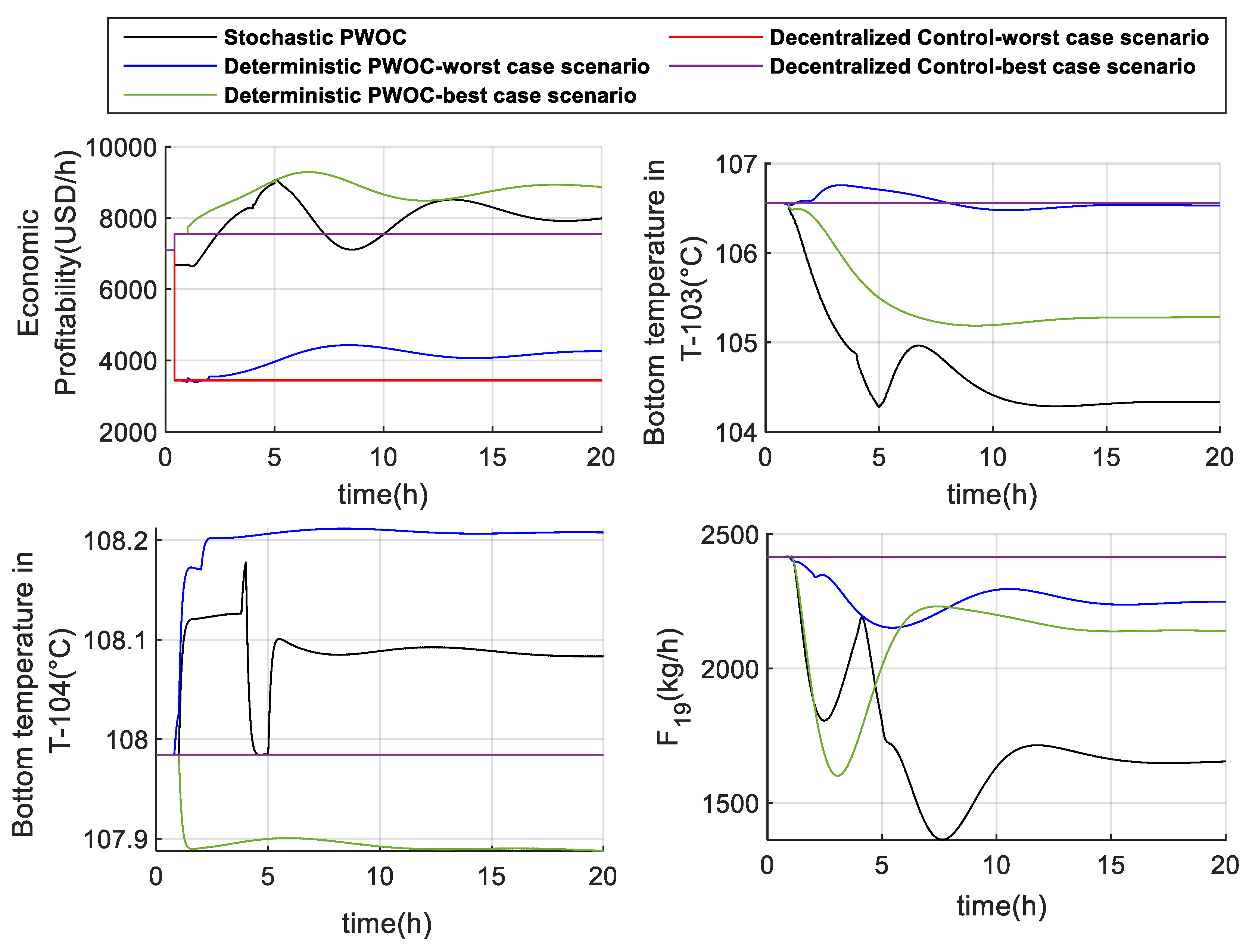

| Tested Architecture. | Cumulative Profitability (USD) |

|---|---|

| Stochastic PWOC approach | 1.5855x105 |

| Deterministic PWOC approach worst-case scenario |

8.2747x104 |

| Deterministic PWOC approach best-case scenario |

1.7391x105 |

| Decentralized Control worst-case scenario |

7.0264x104 |

| Decentralized Control best-case scenario |

1.5080x105 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).