Submitted:

03 September 2024

Posted:

04 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Researching Field | Methodology | Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical modeling | Short-circuit blowing in center of Laval nozzle theory [6]. | Lacking specific experimental evaluations and universality because of ignoring entire manipulation factors. |

| Gas-liquid two-phase interface evolution modeling of blowing [1]. | ||

| Simulation considering flowing area of sea valve of blowing [3]. | ||

| Simulation considering outboard back pressure, high-pressure cylinder group gas pressure and cylinder volume of blowing [4]. | ||

| Simulation considering the gas or water supply pipeline [5]. | ||

| Real ship or bench experiments | Emergency short-circuit blowing test on a Spanish S-80 submarine [7]. | Too risky. |

| Experiments considering the depth of 100m [8,9]. | Restriction of scale effect. | |

| Experiments of small-scale short-circuit blowing test bench [10,11]. | ||

| Experiments of proportional short-circuit blowing model test [2]. | Incomplete working conditions, ignoring entire manipulation factors. |

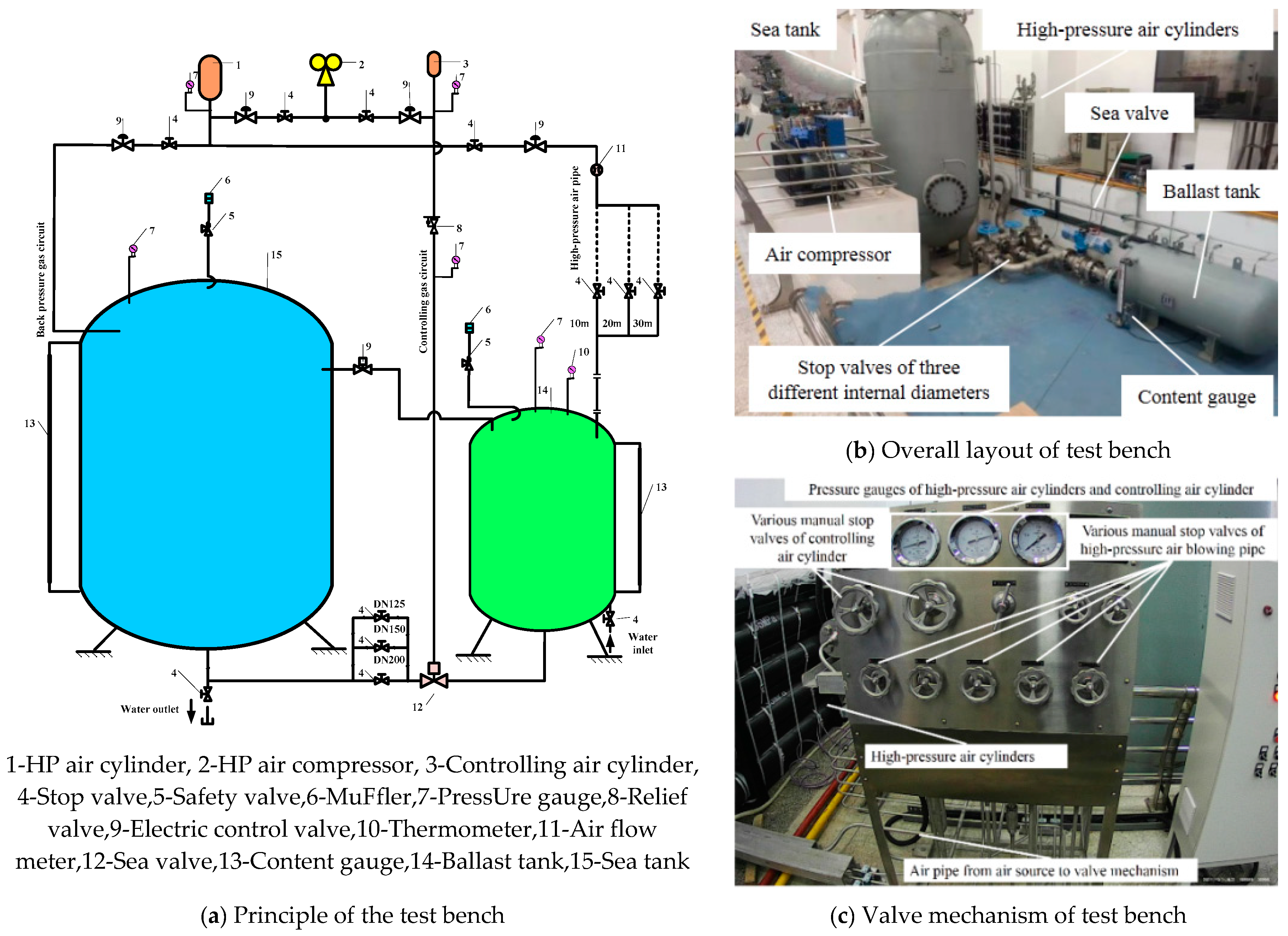

- First, in section 2, seven detailed influencing factors of 3 levels of high pressure short-circuit blowing were further considered in and corresponding proportional model test bench had been built, L18(37) orthogonal experiments were carried out.

- Second, in section 3, by analysis of extreme variance and variance, the correlation coefficients of blowing duration, sea tank back pressure, gas blowing pressure of the cylinder group, and sea valve flowing area were 0.6535, 0.8105, 0.5569, 0.5373, of which the F-ratio of blowing duration is over critical value 3.24.

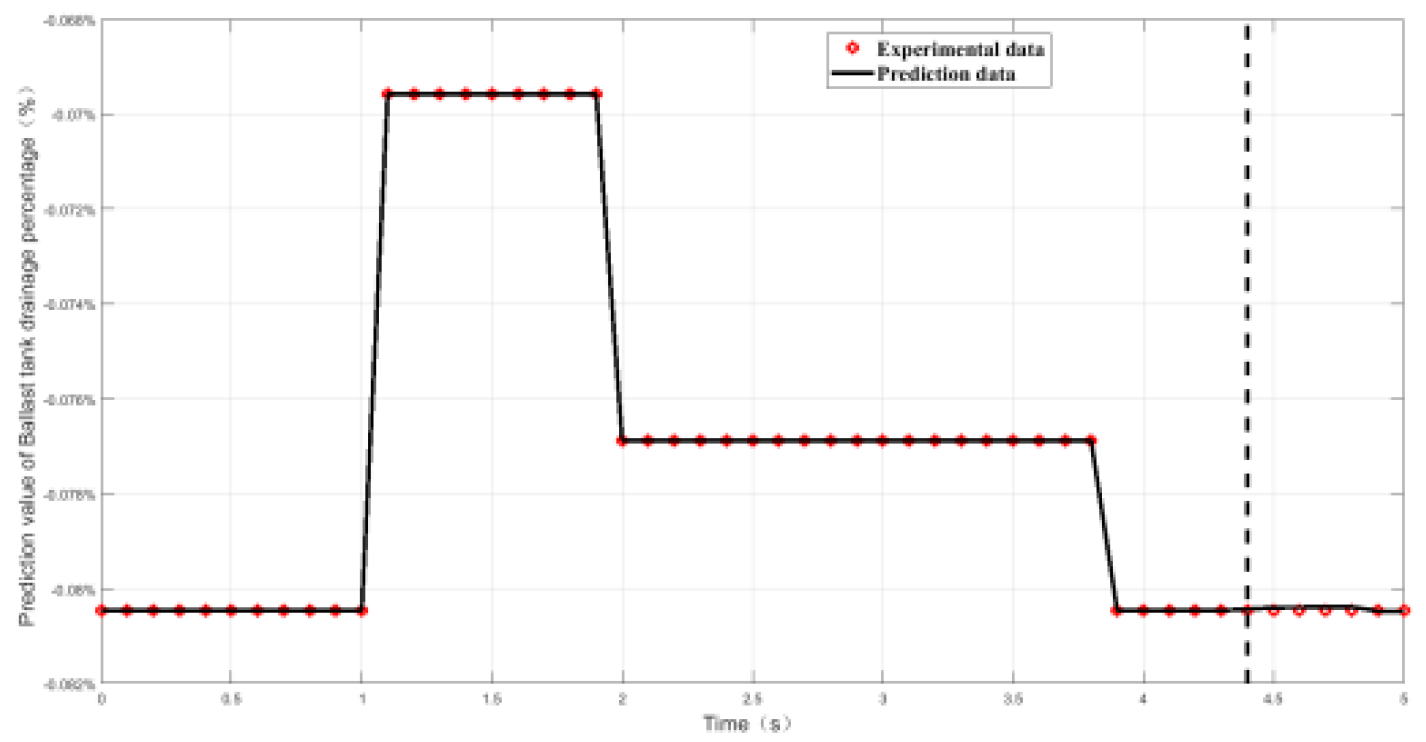

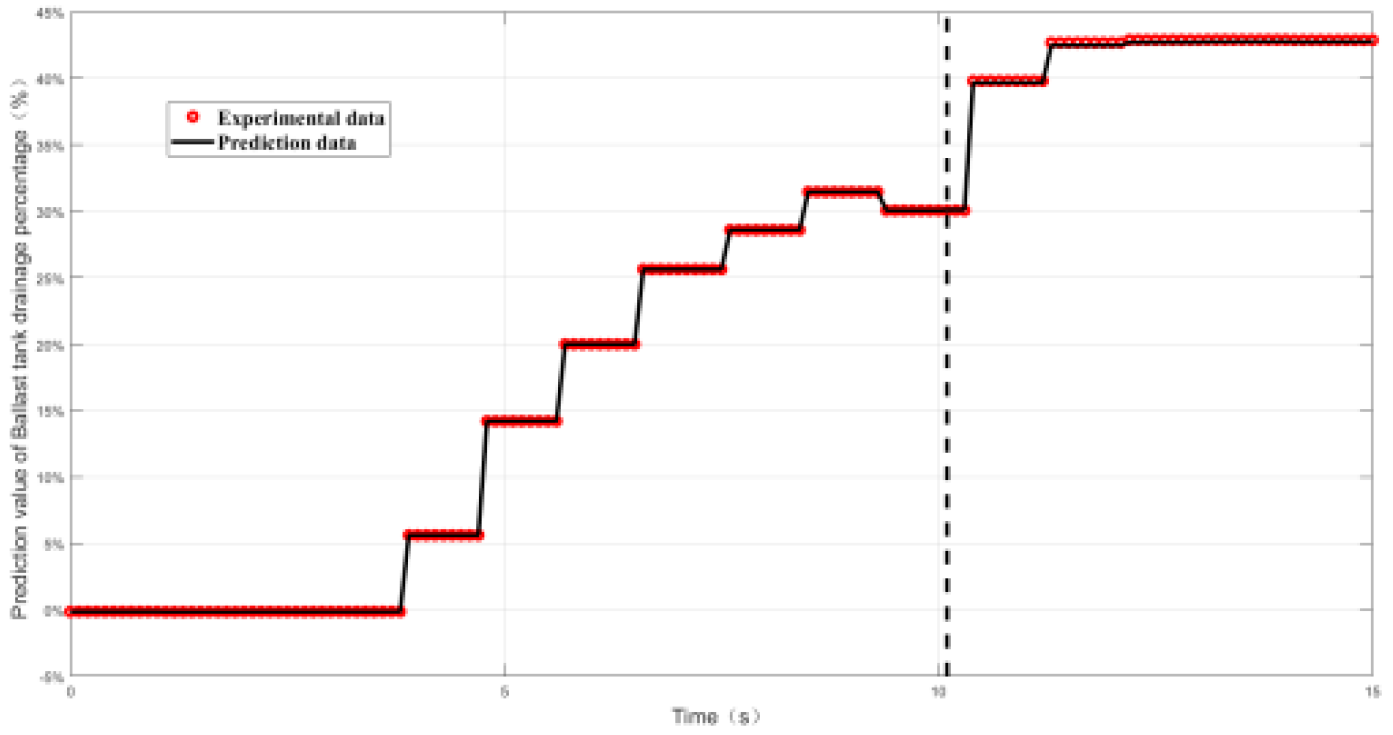

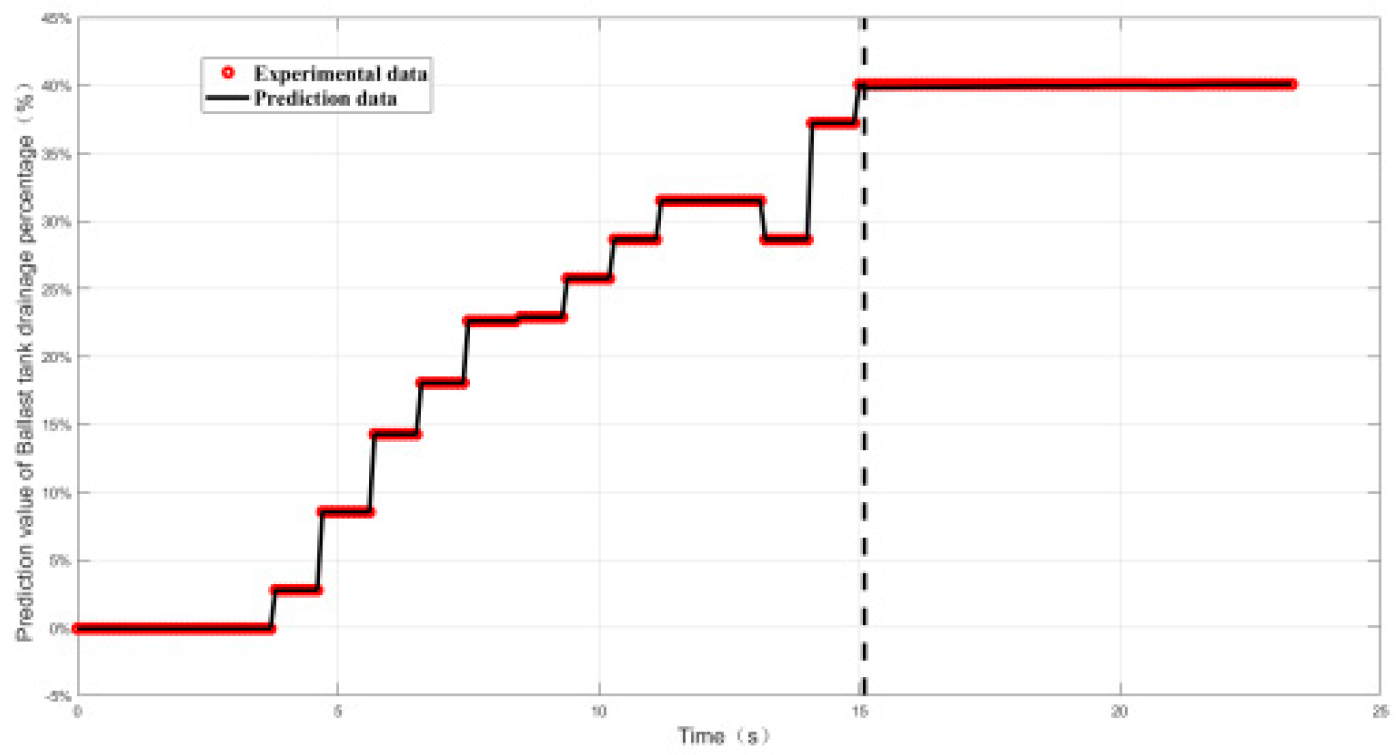

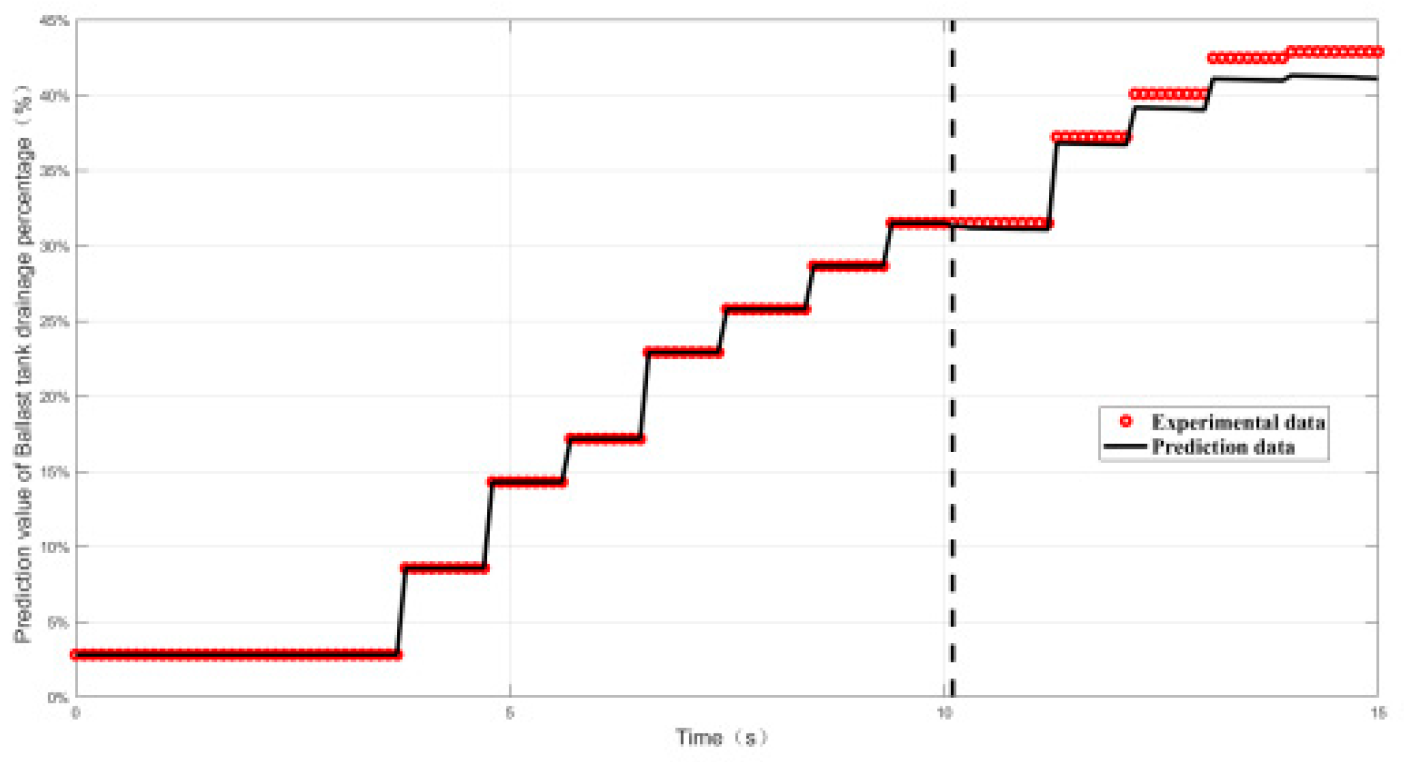

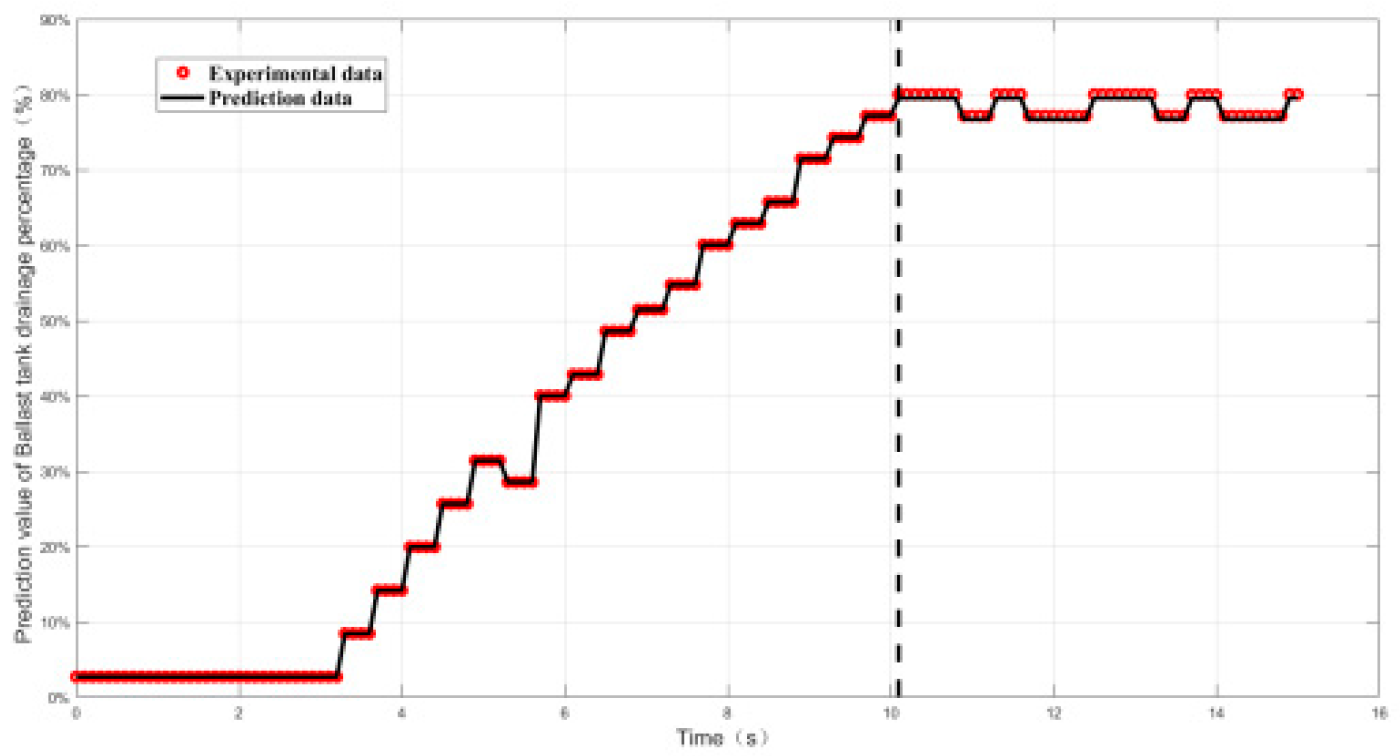

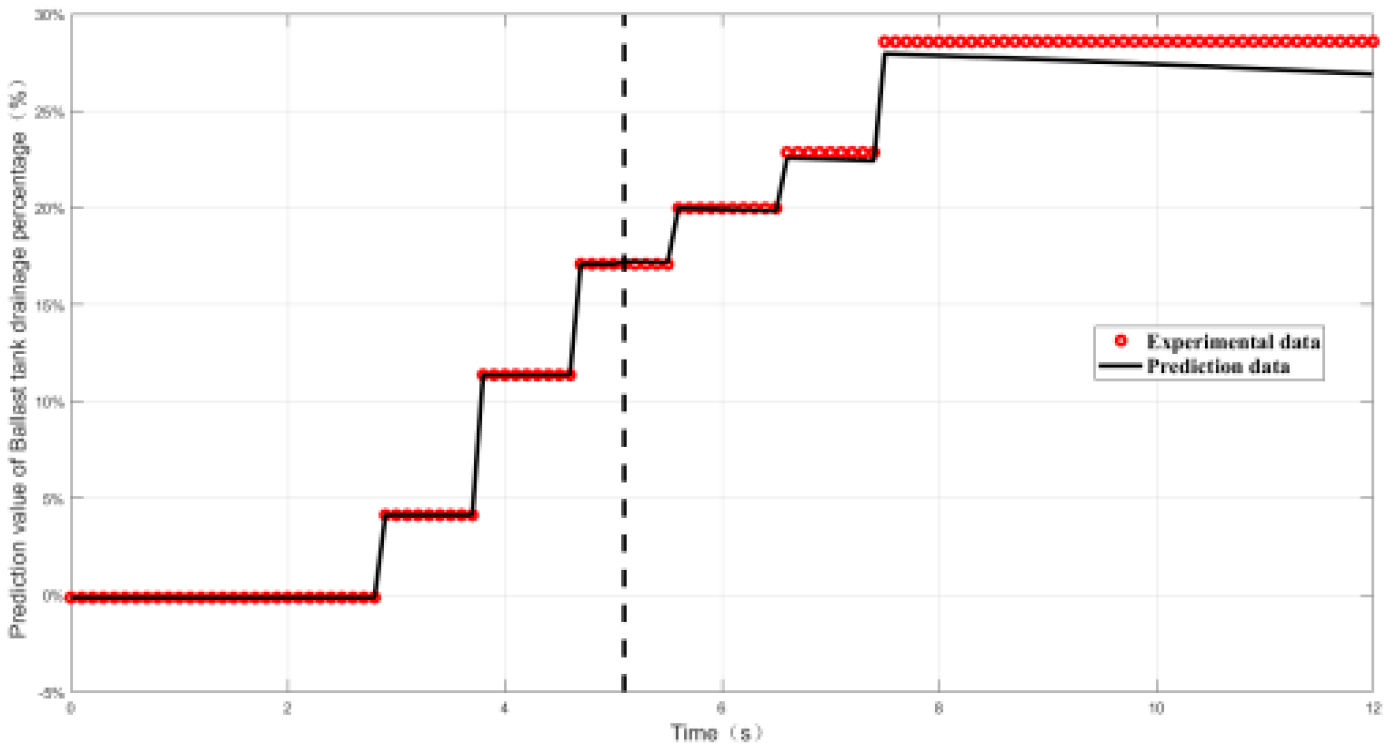

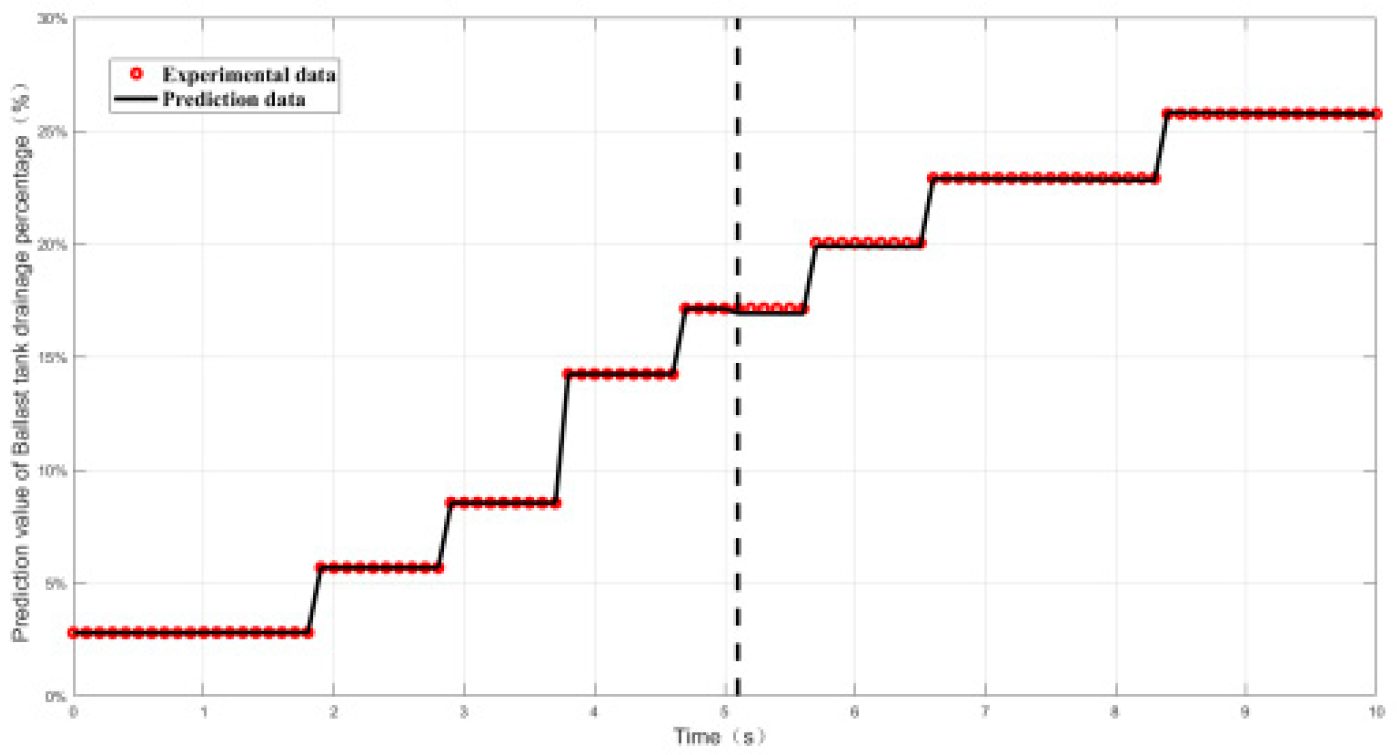

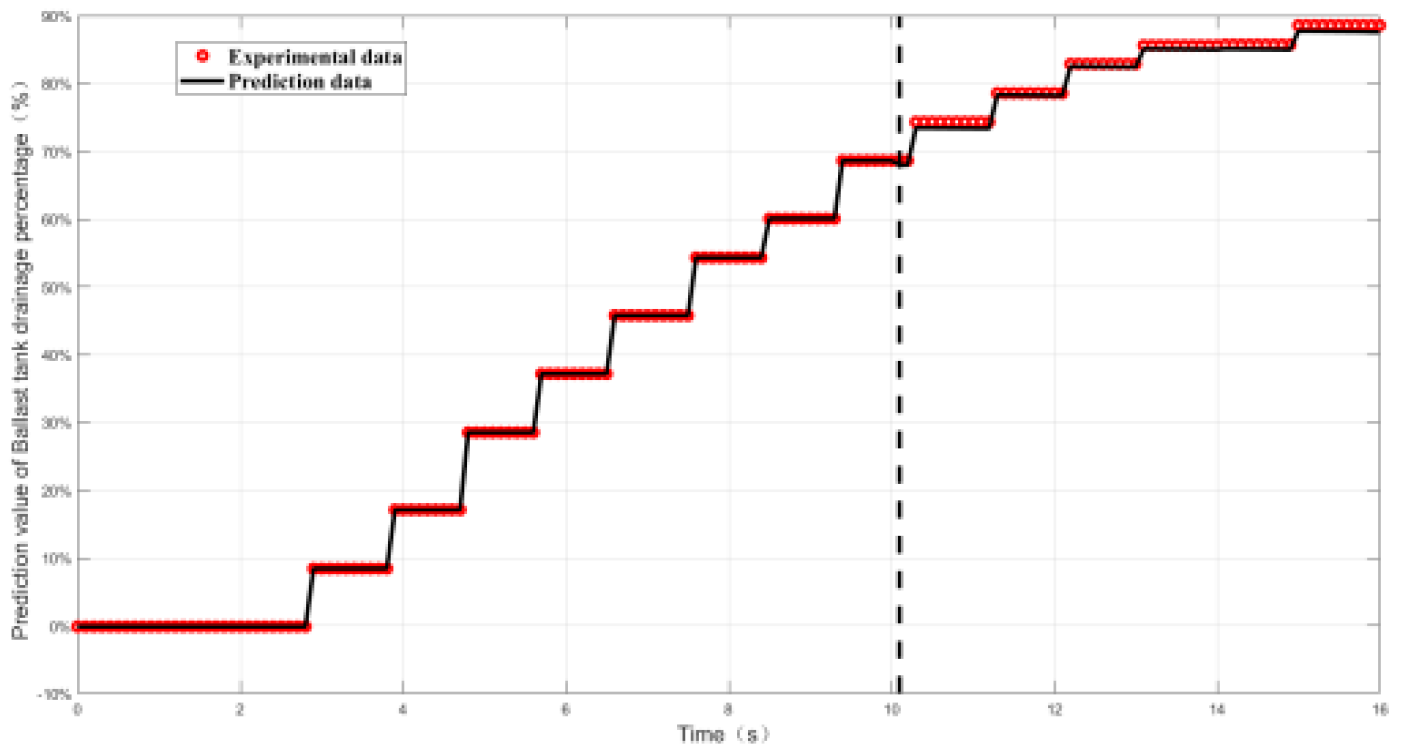

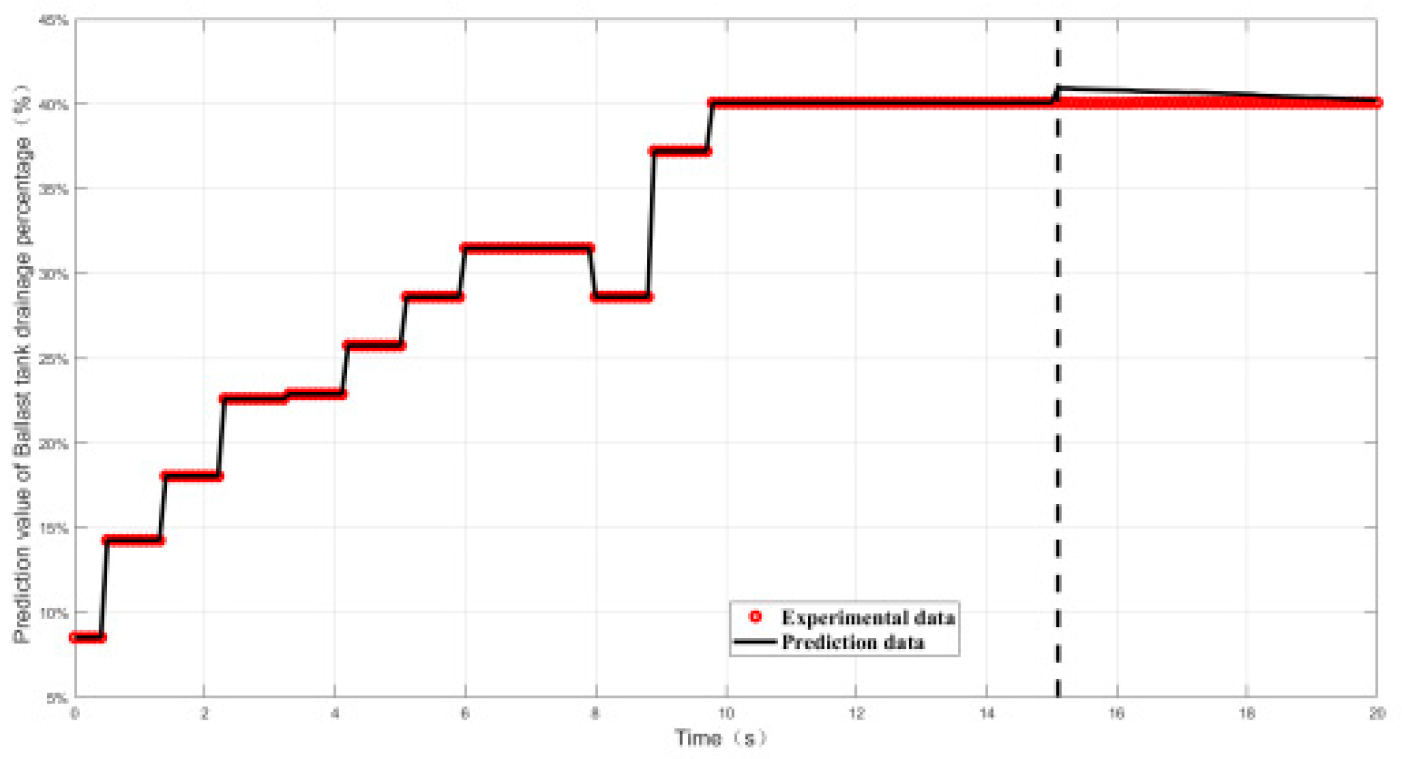

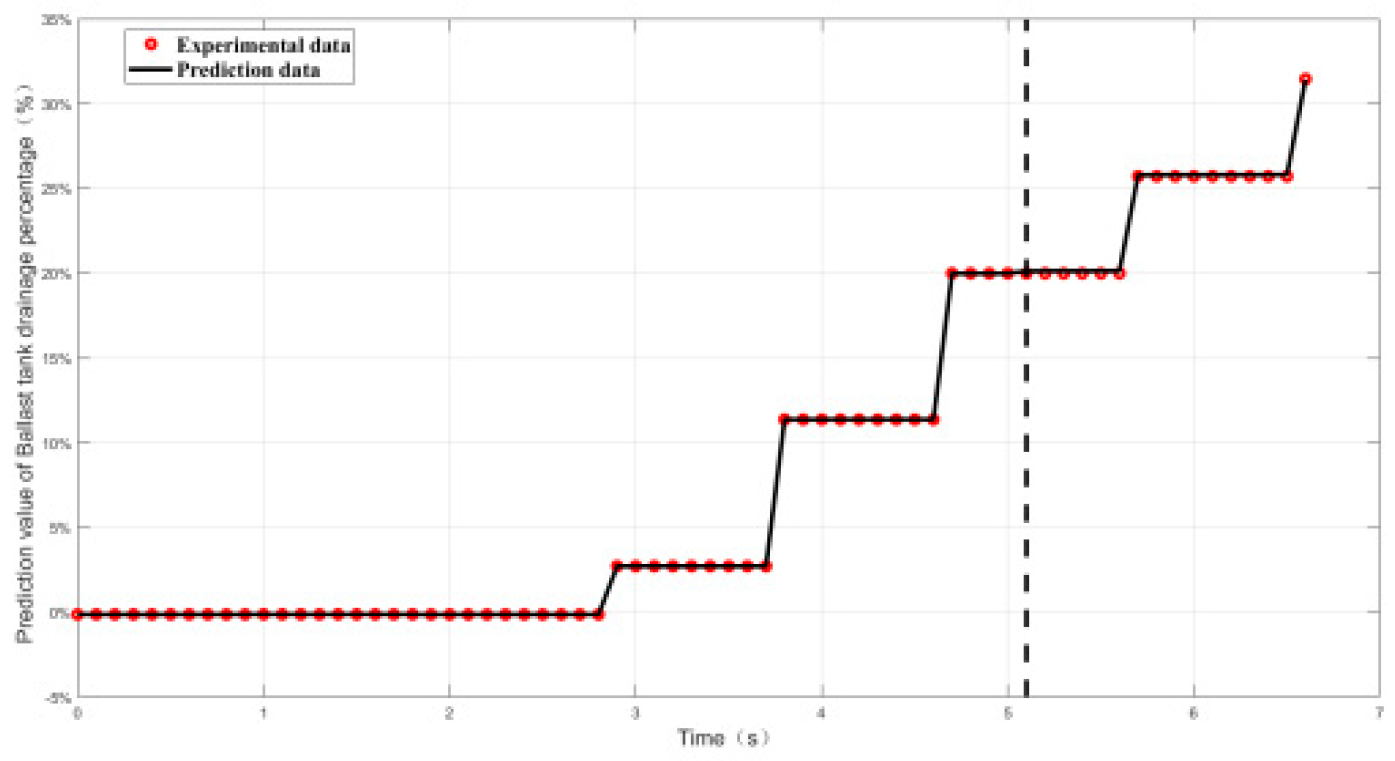

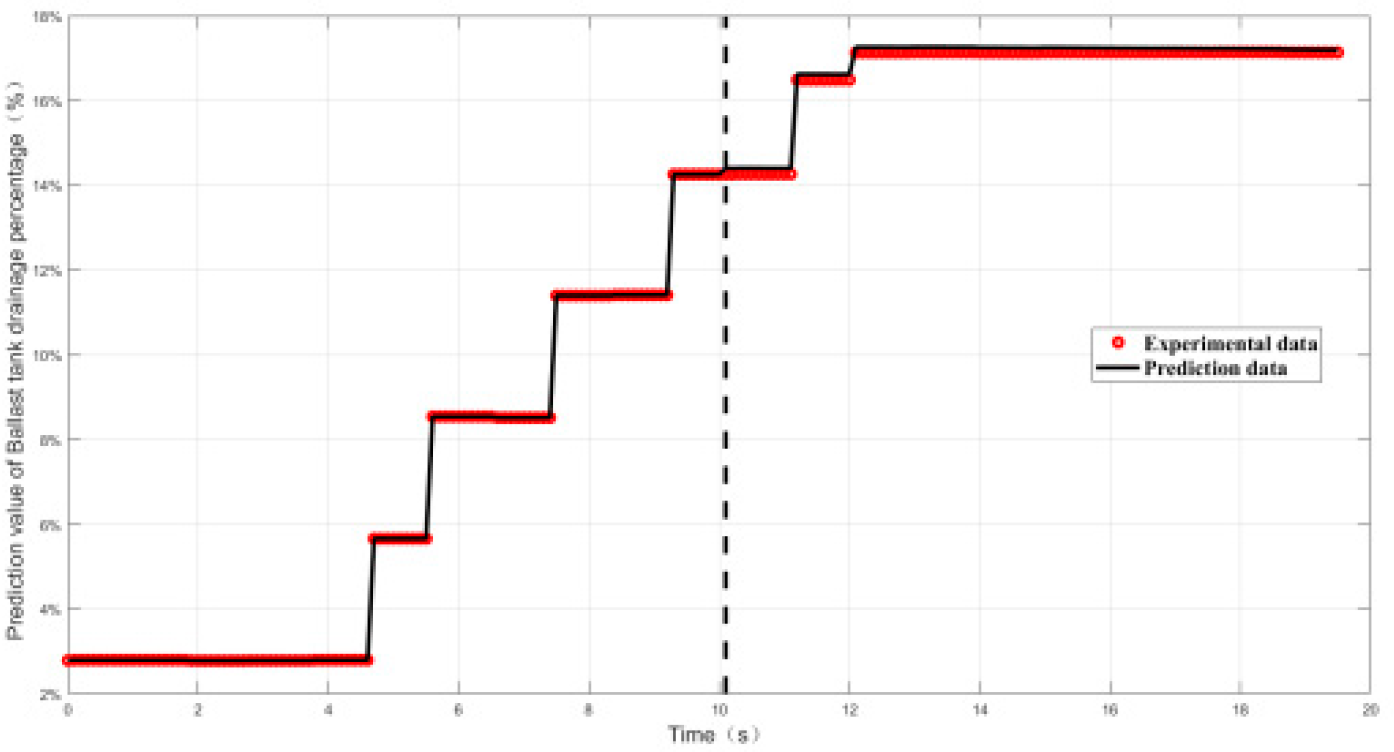

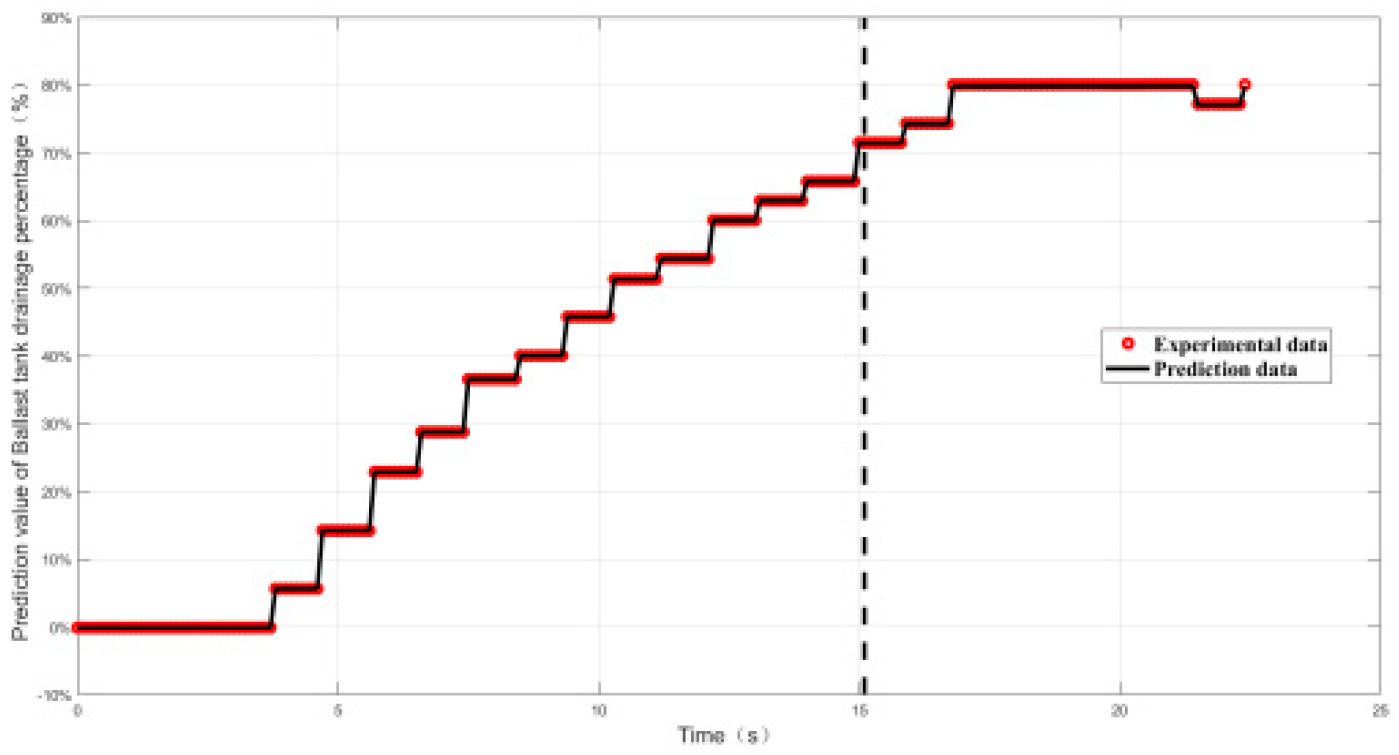

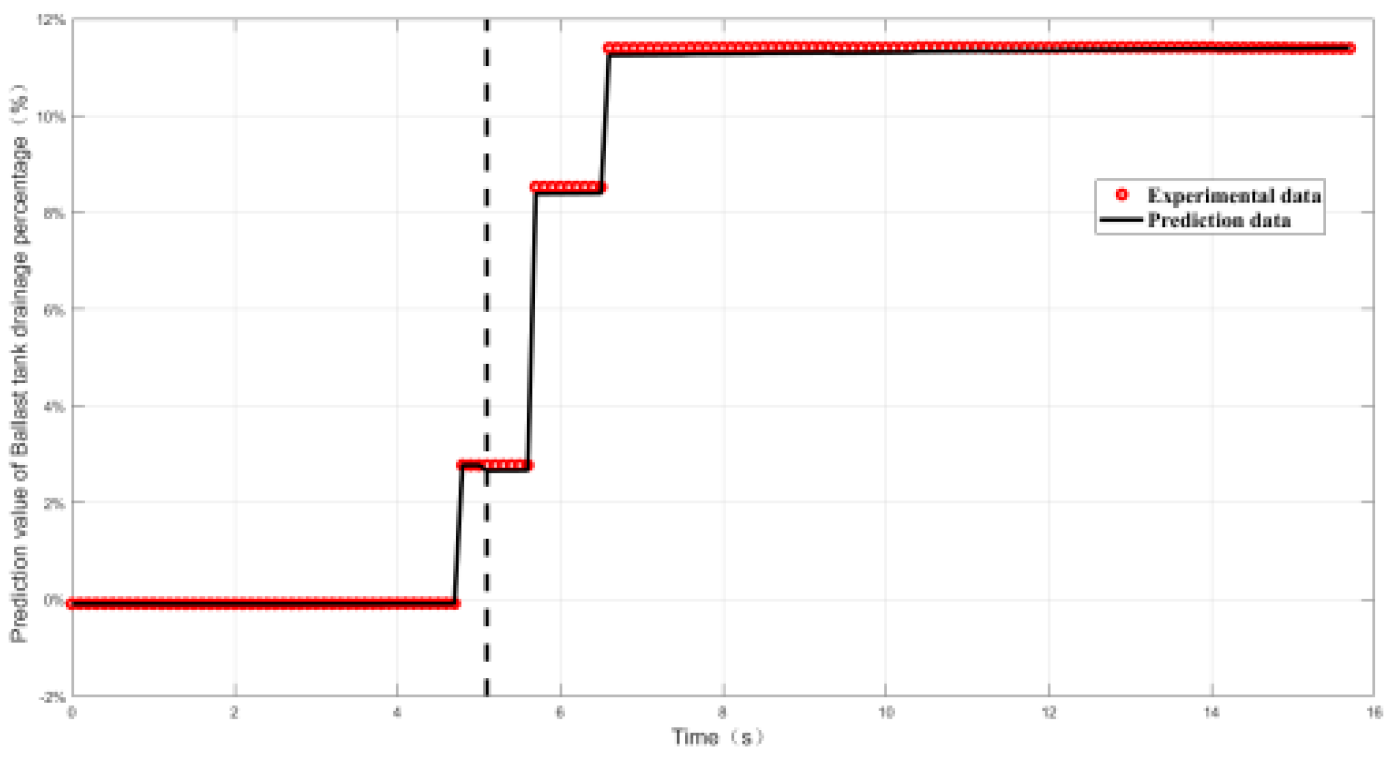

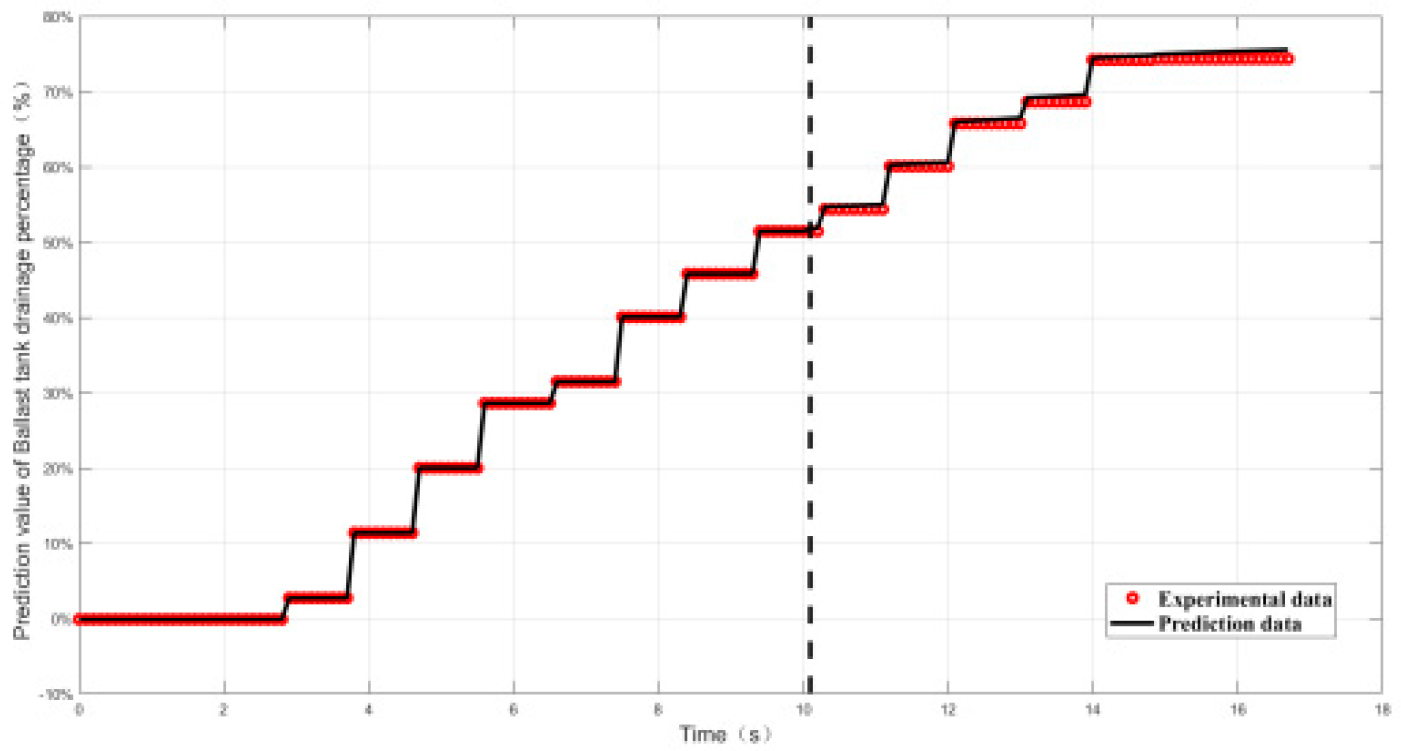

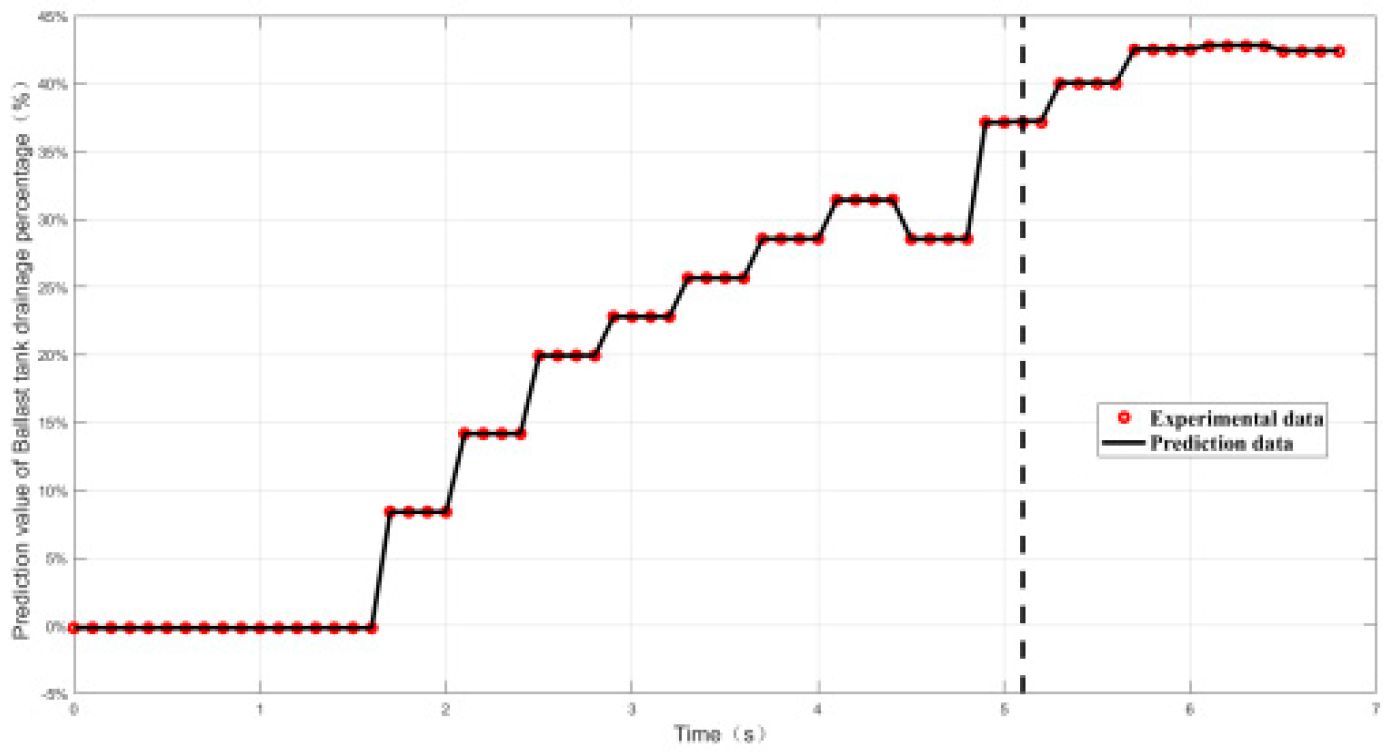

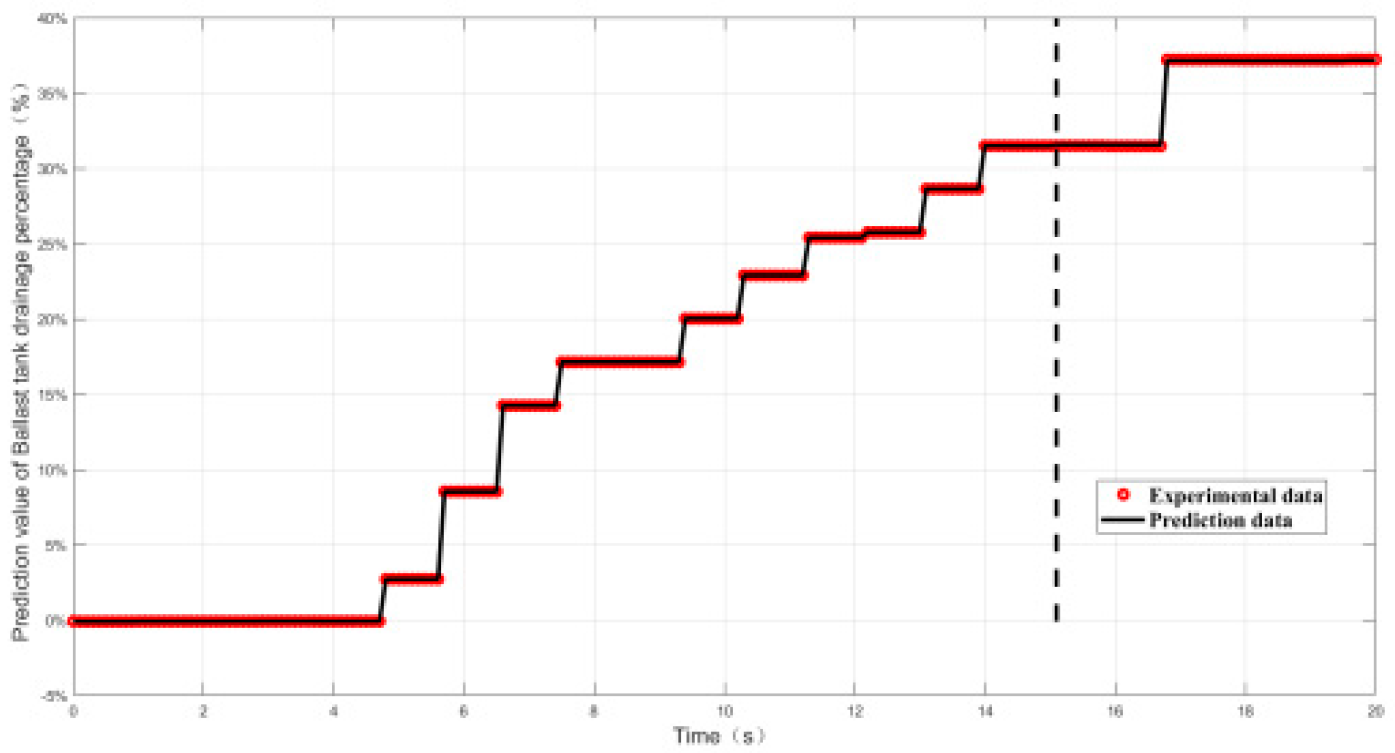

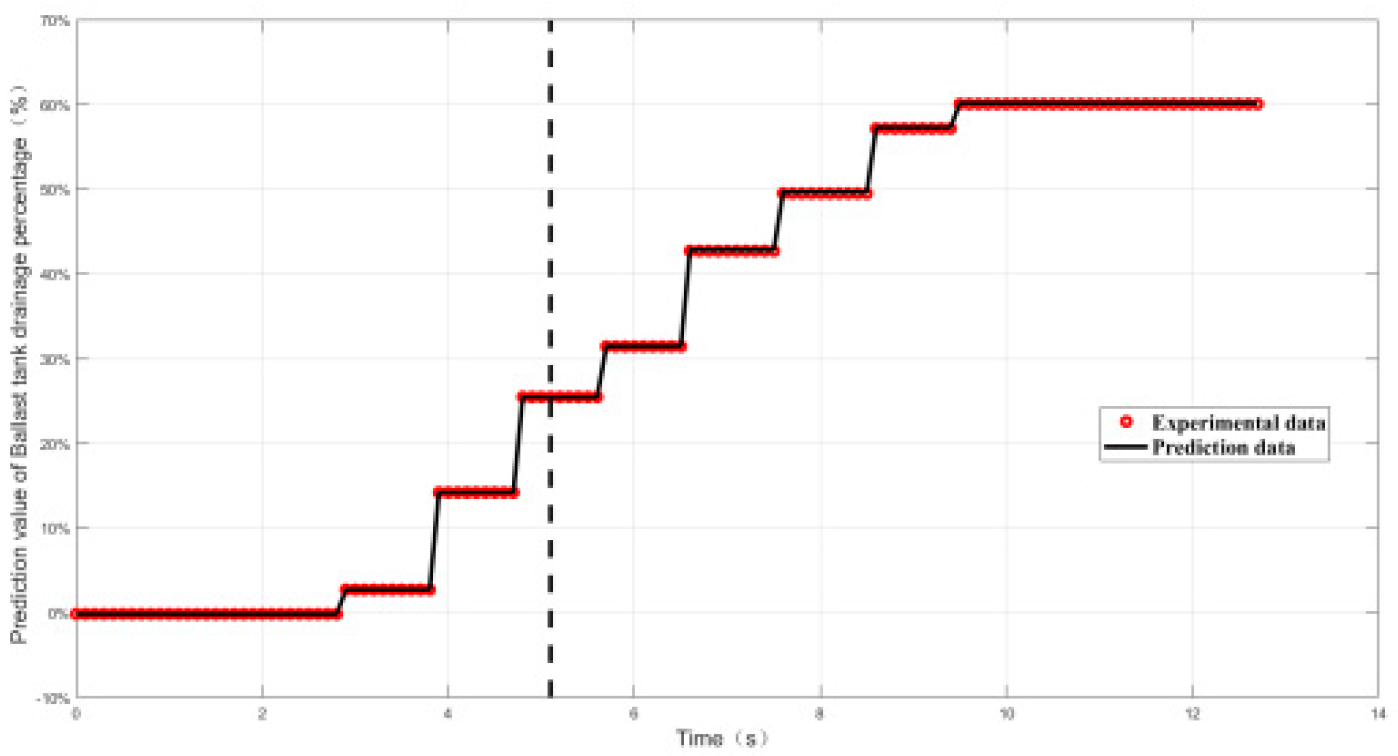

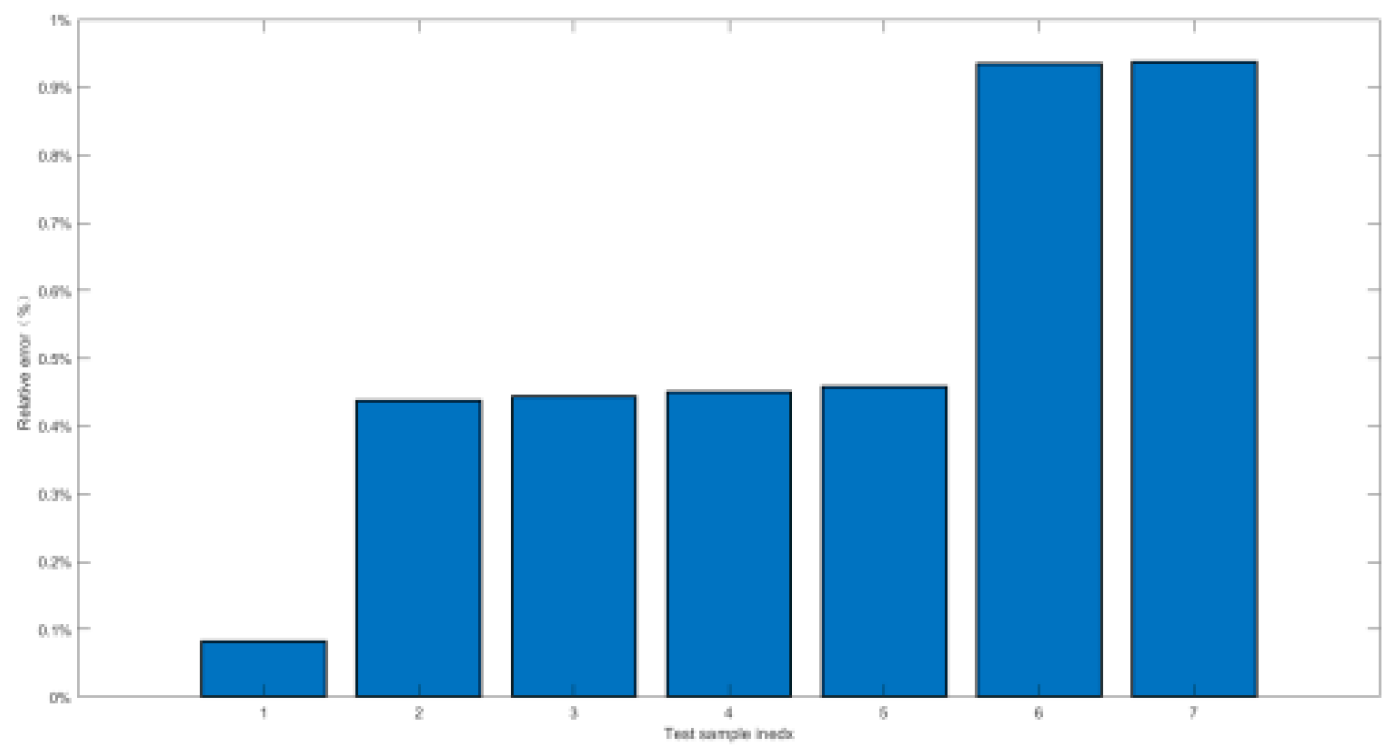

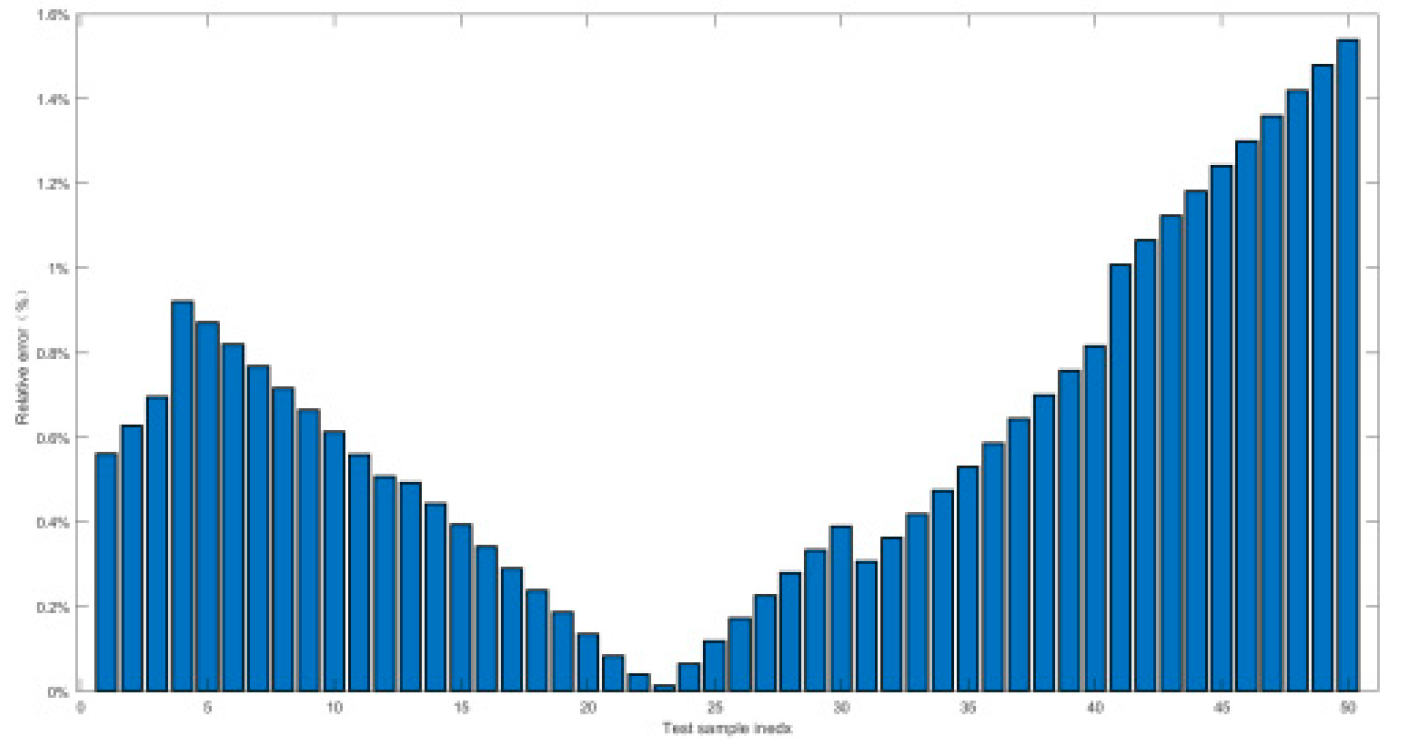

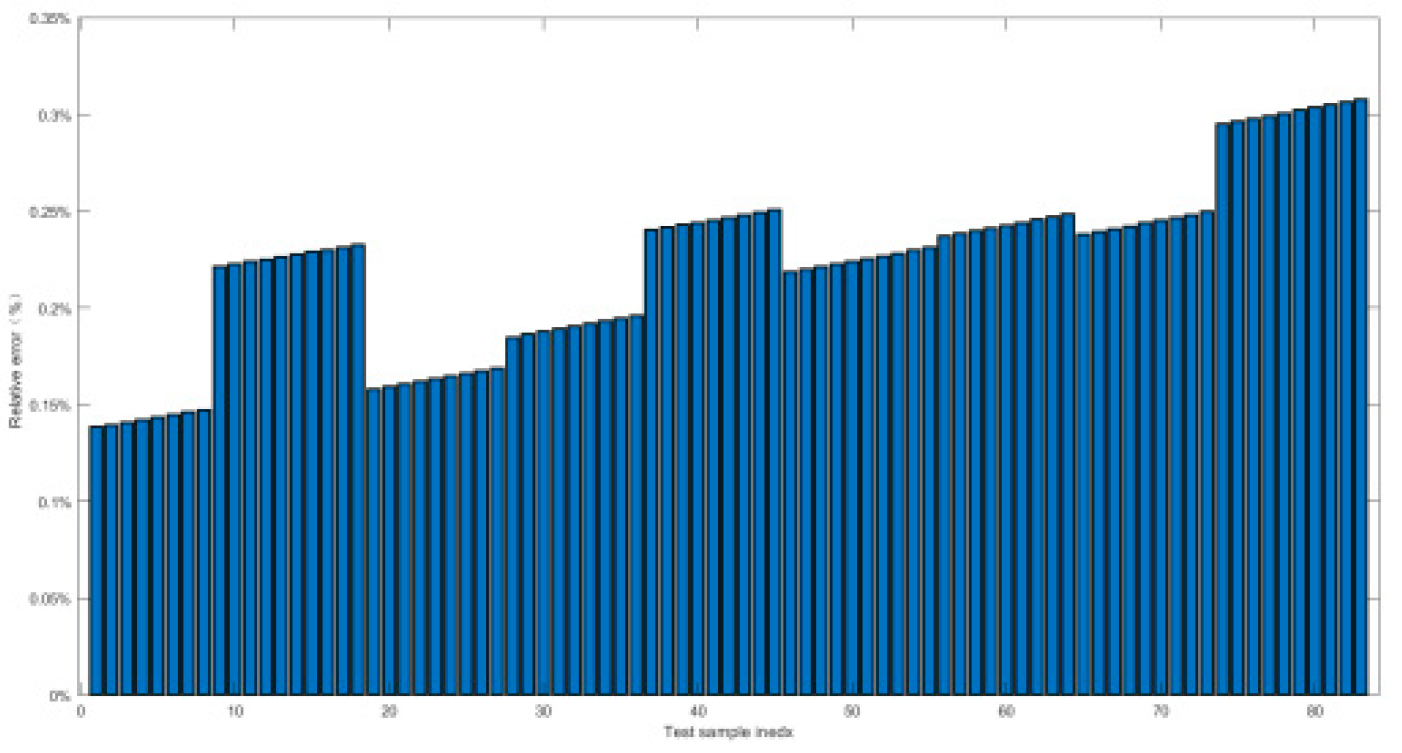

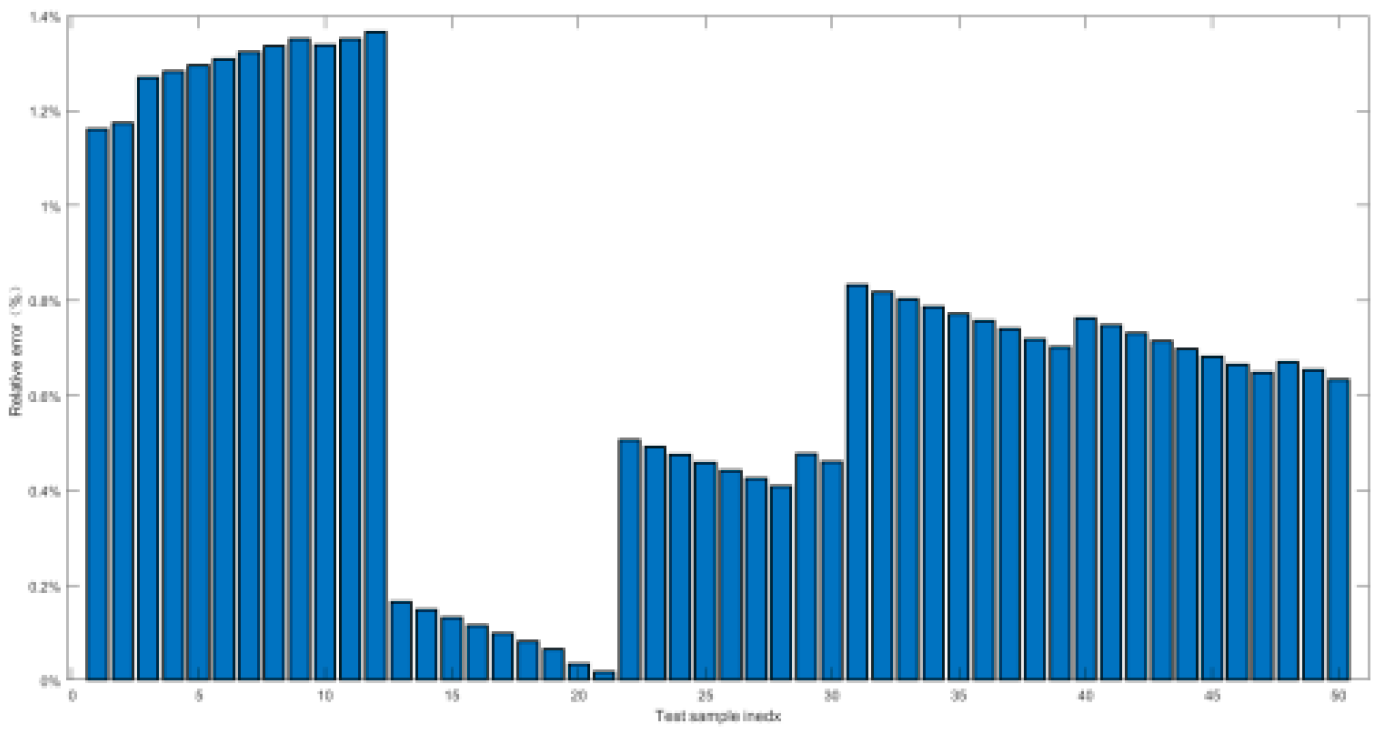

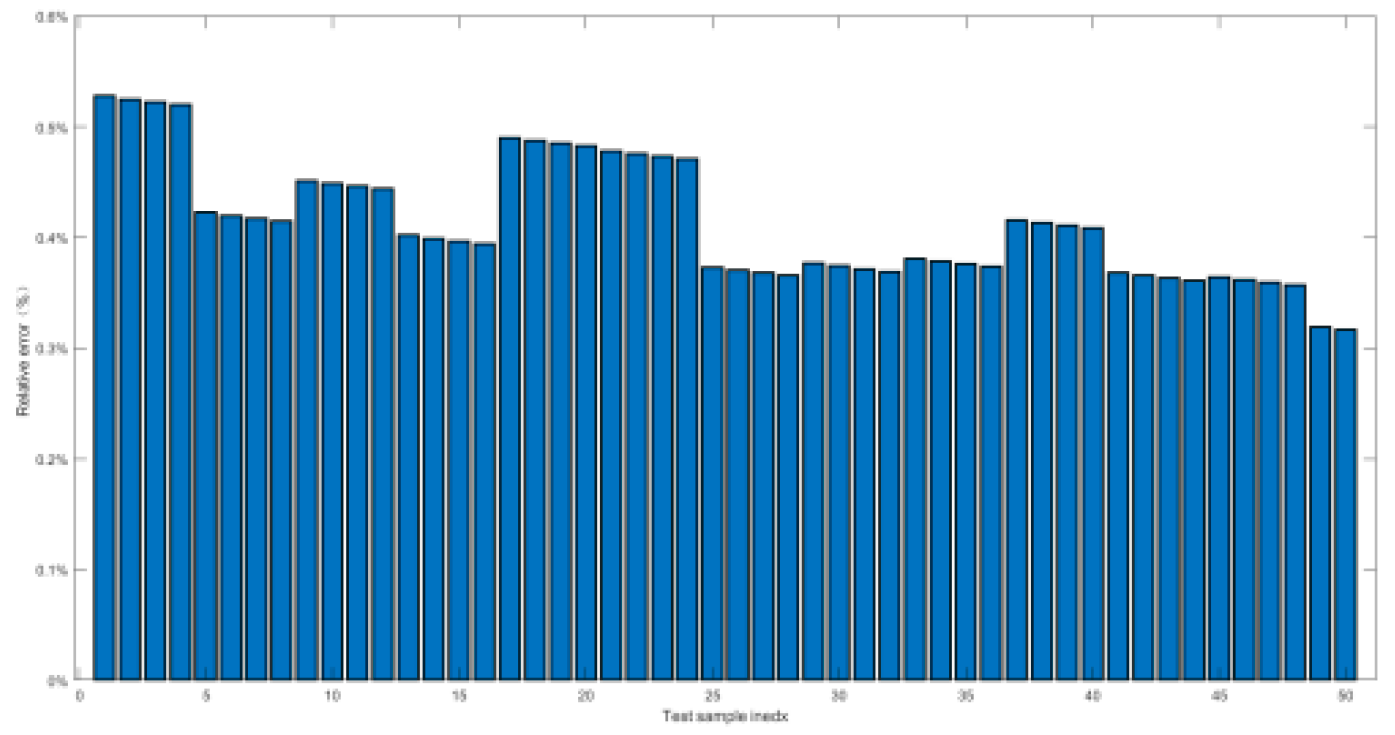

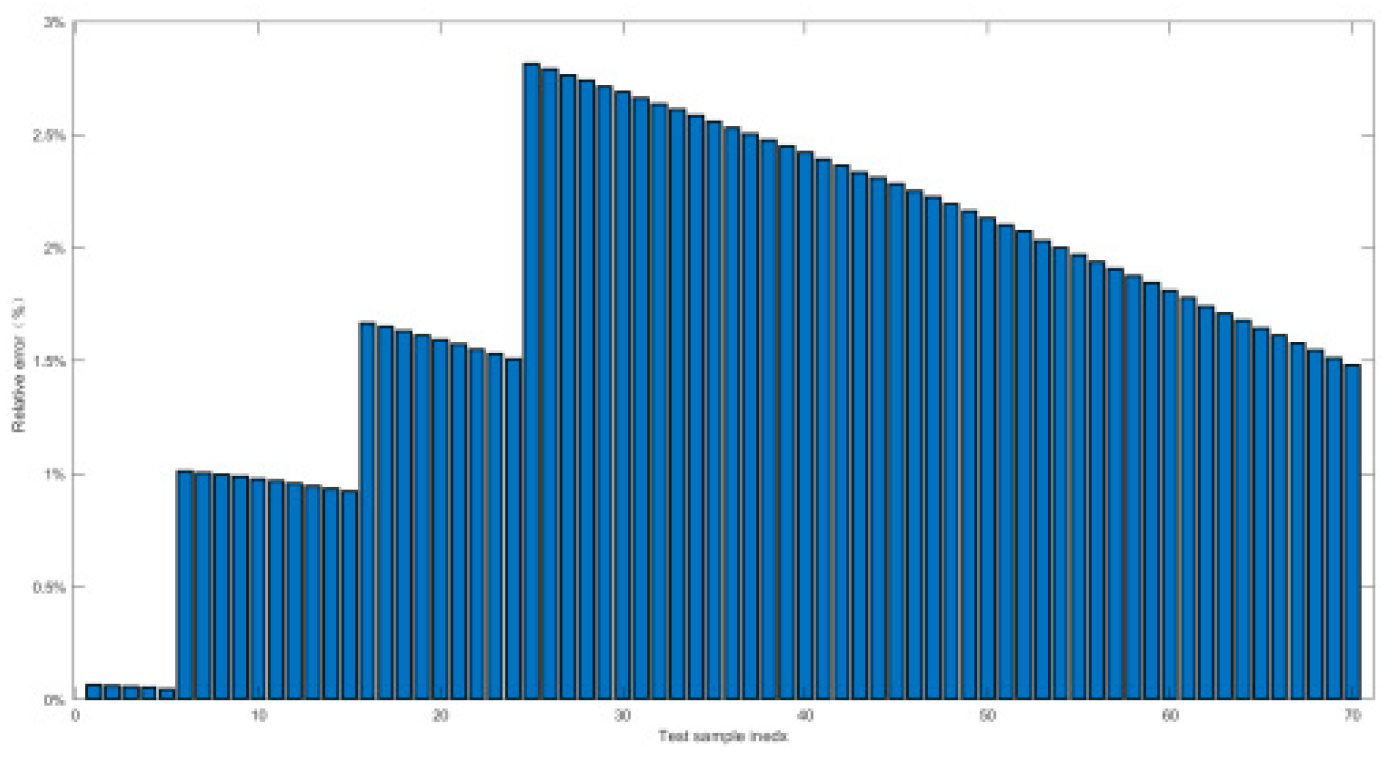

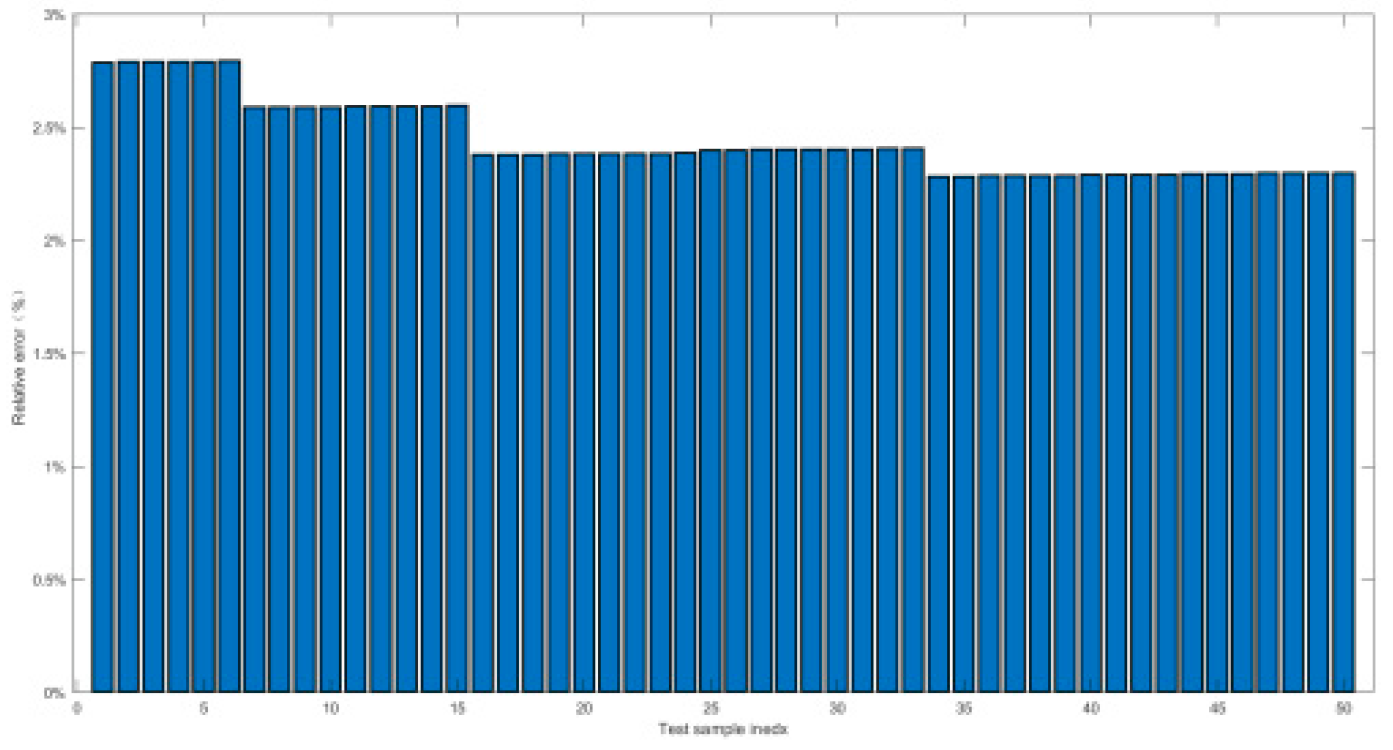

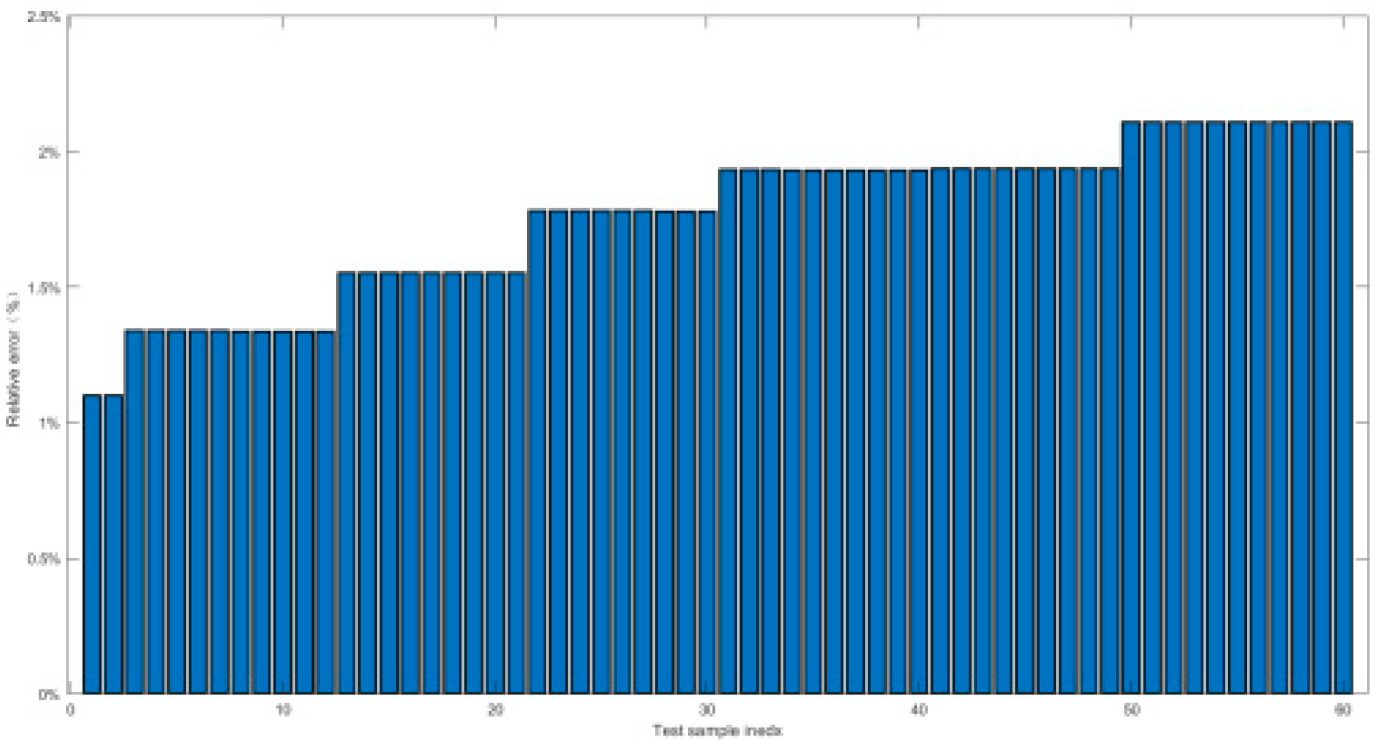

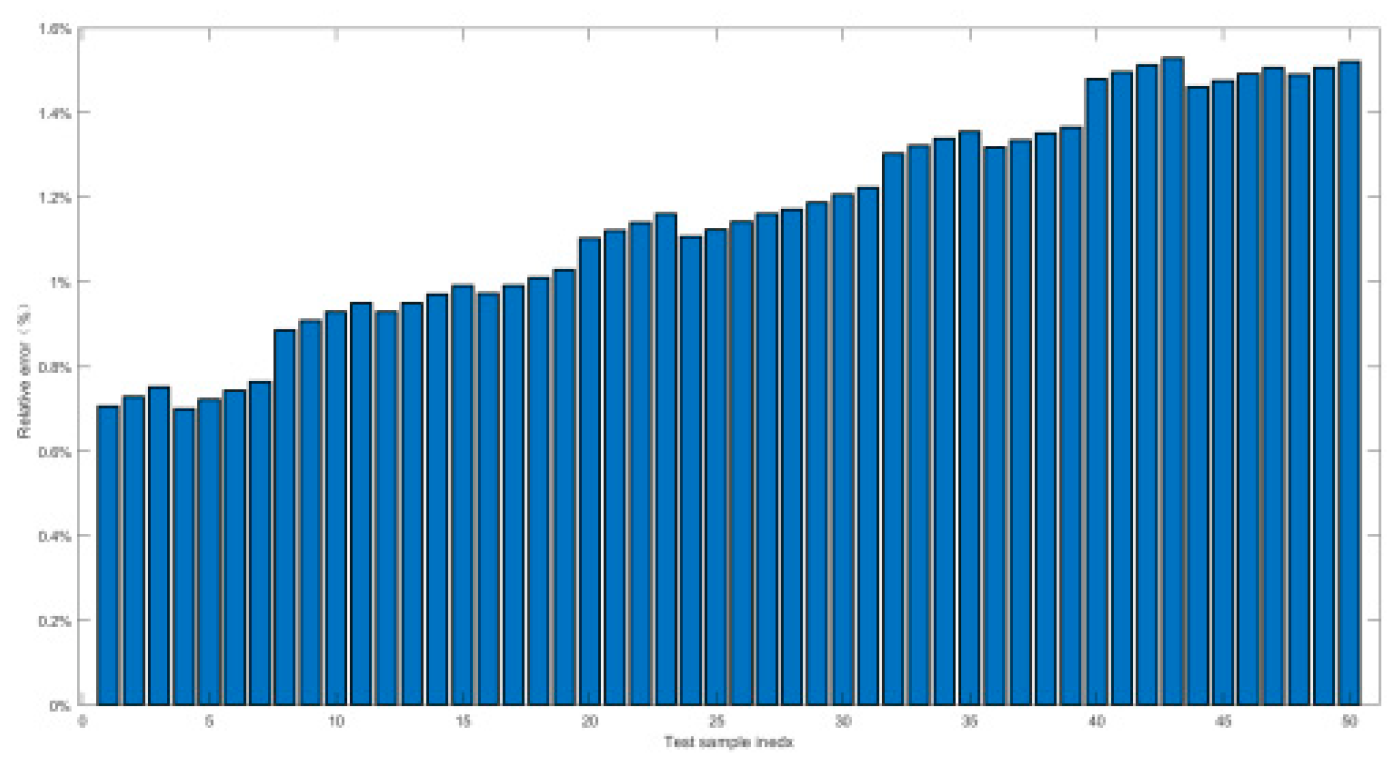

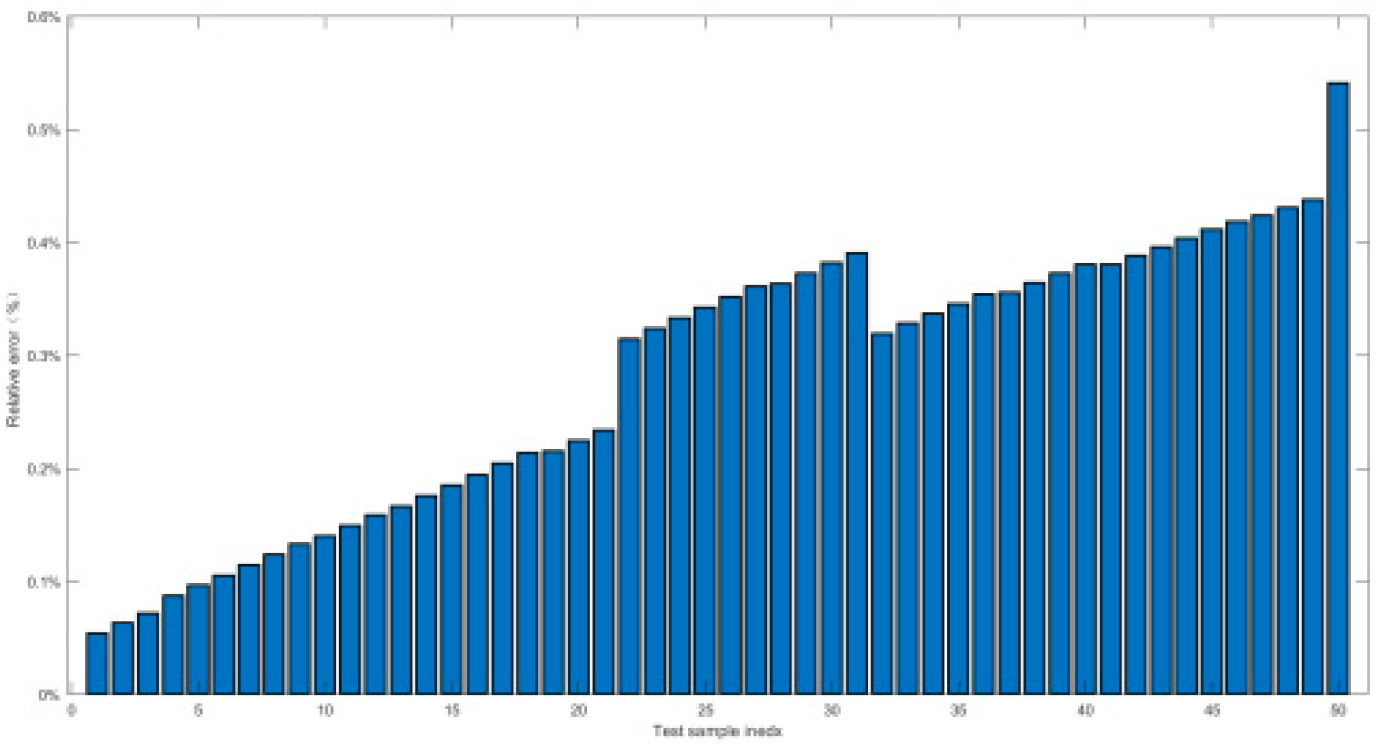

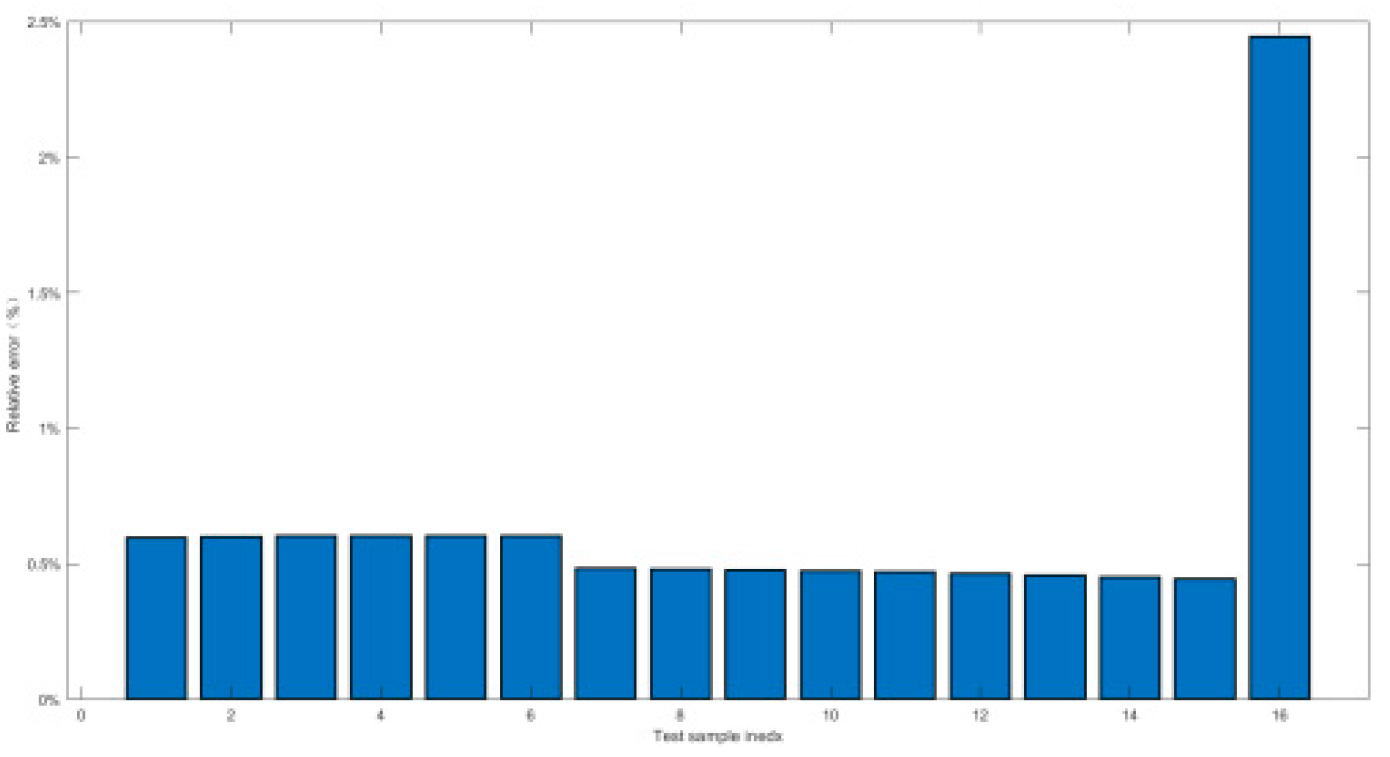

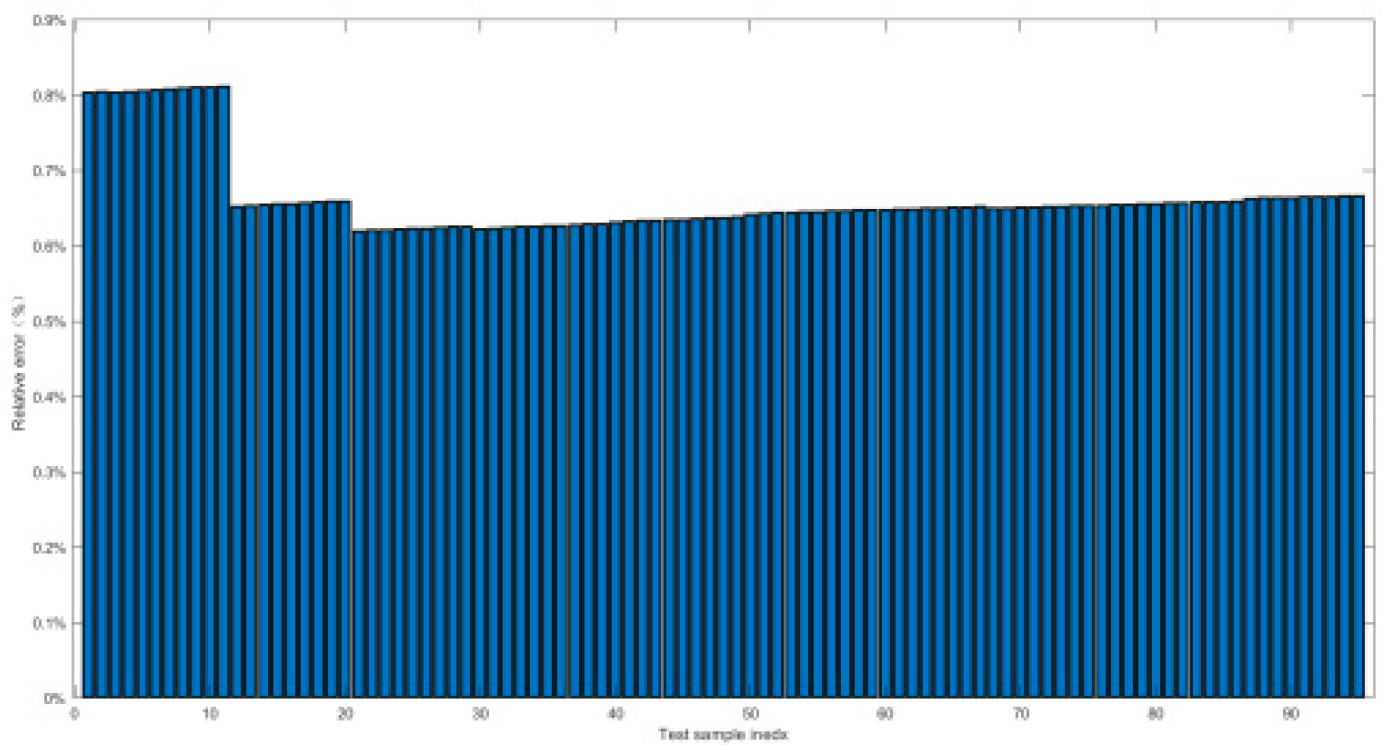

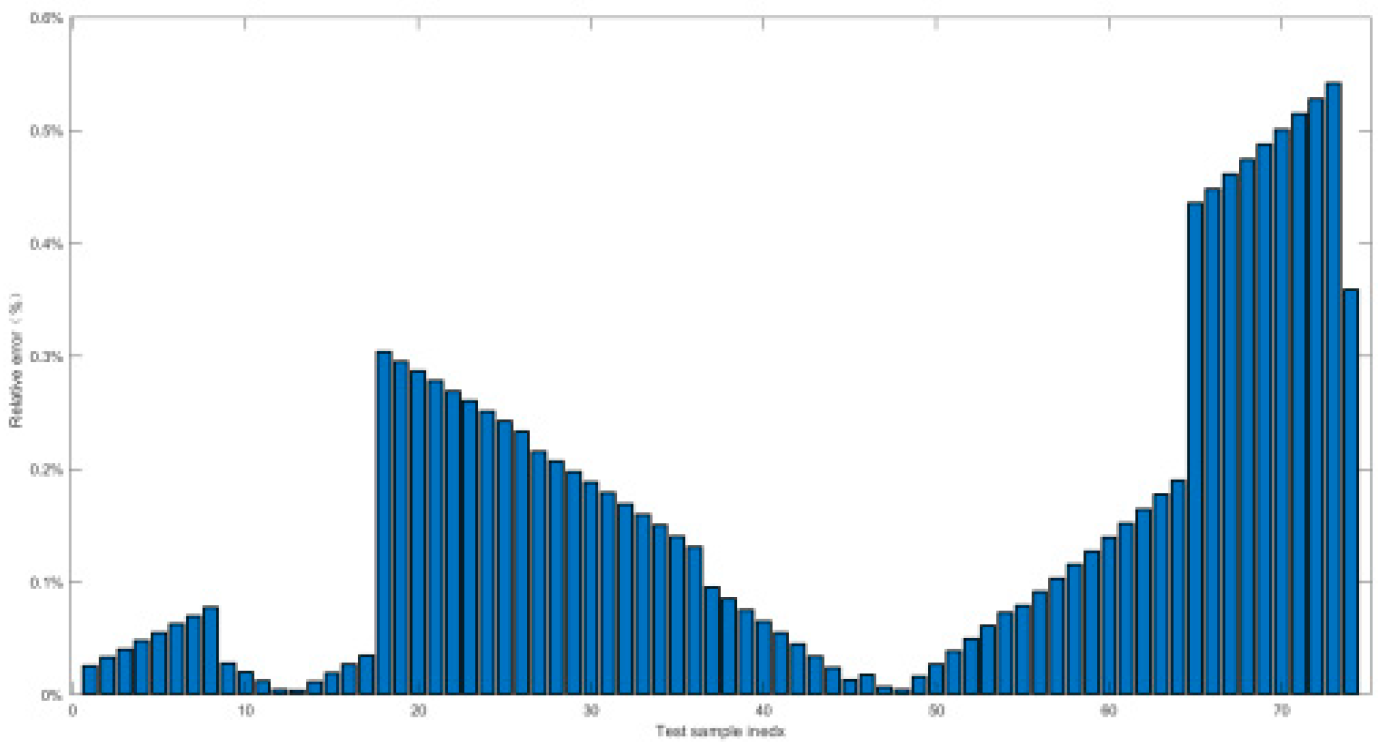

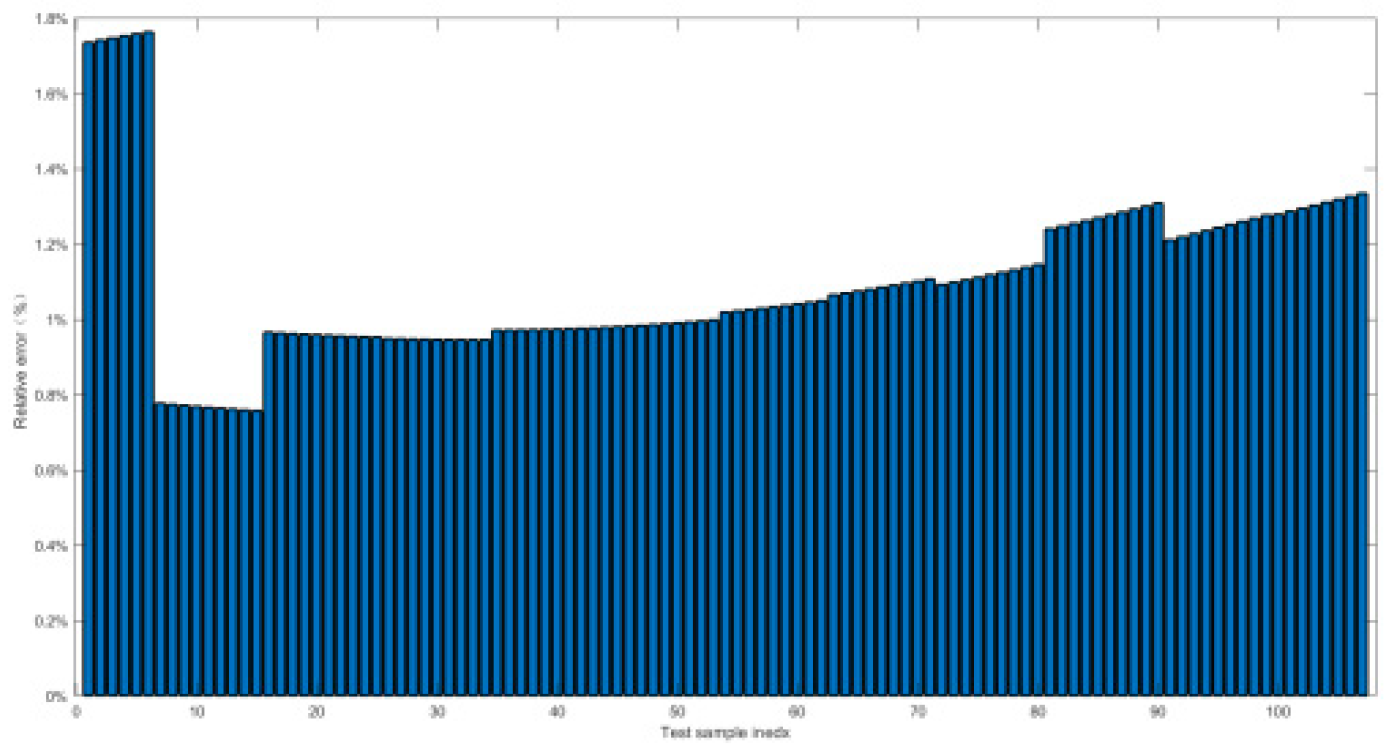

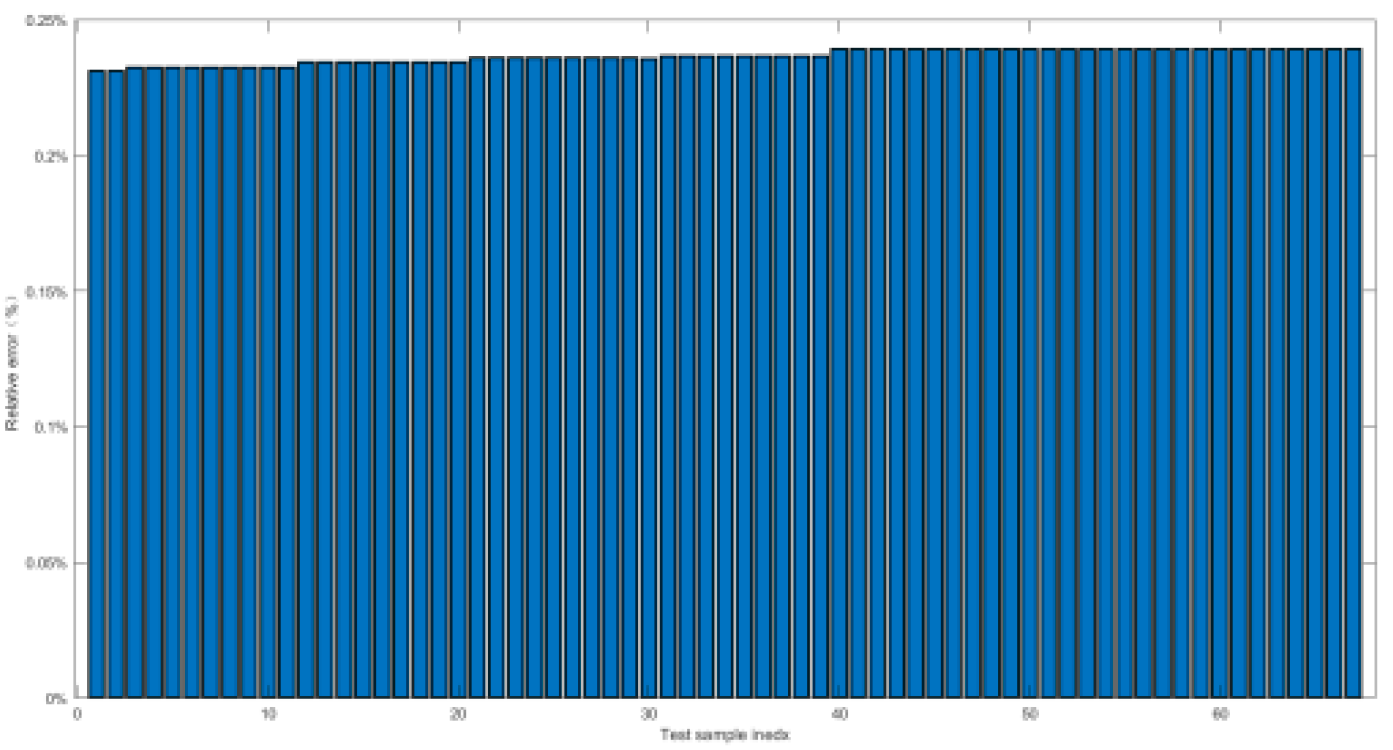

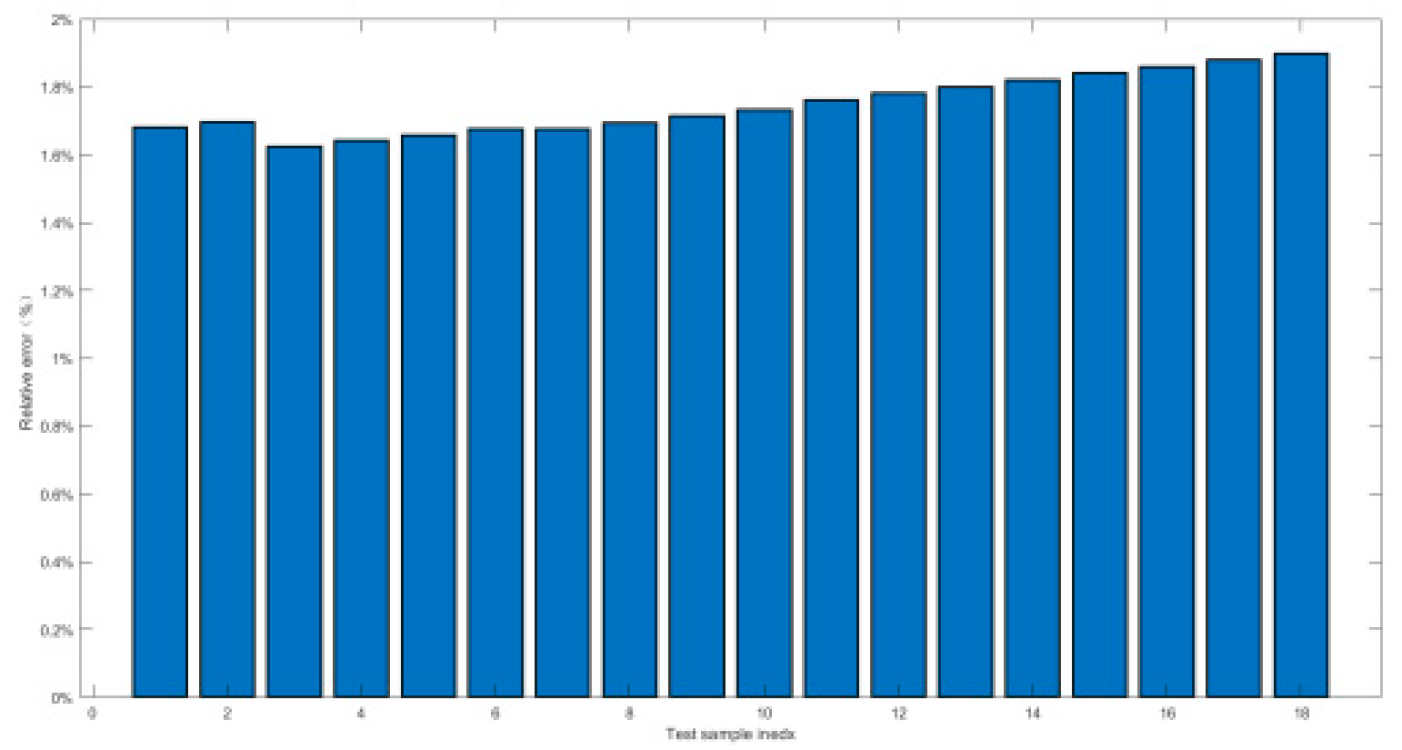

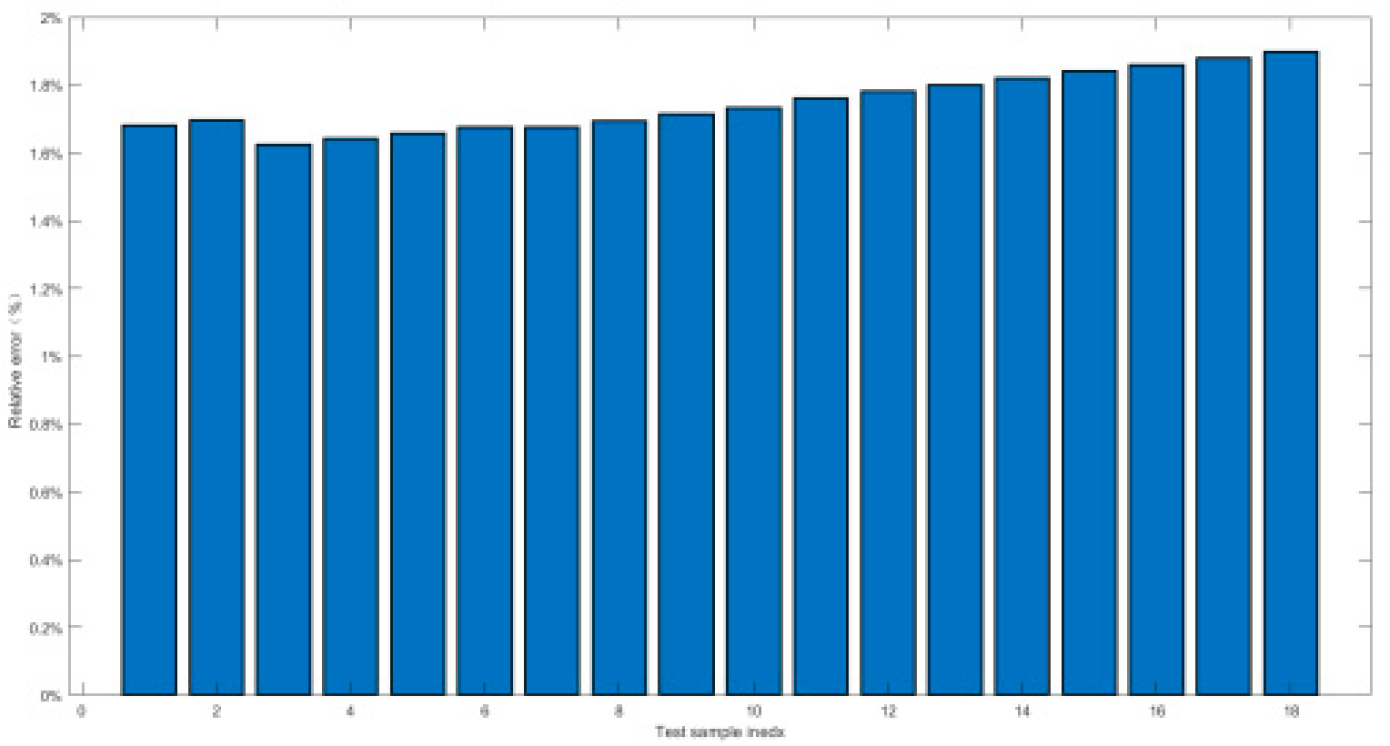

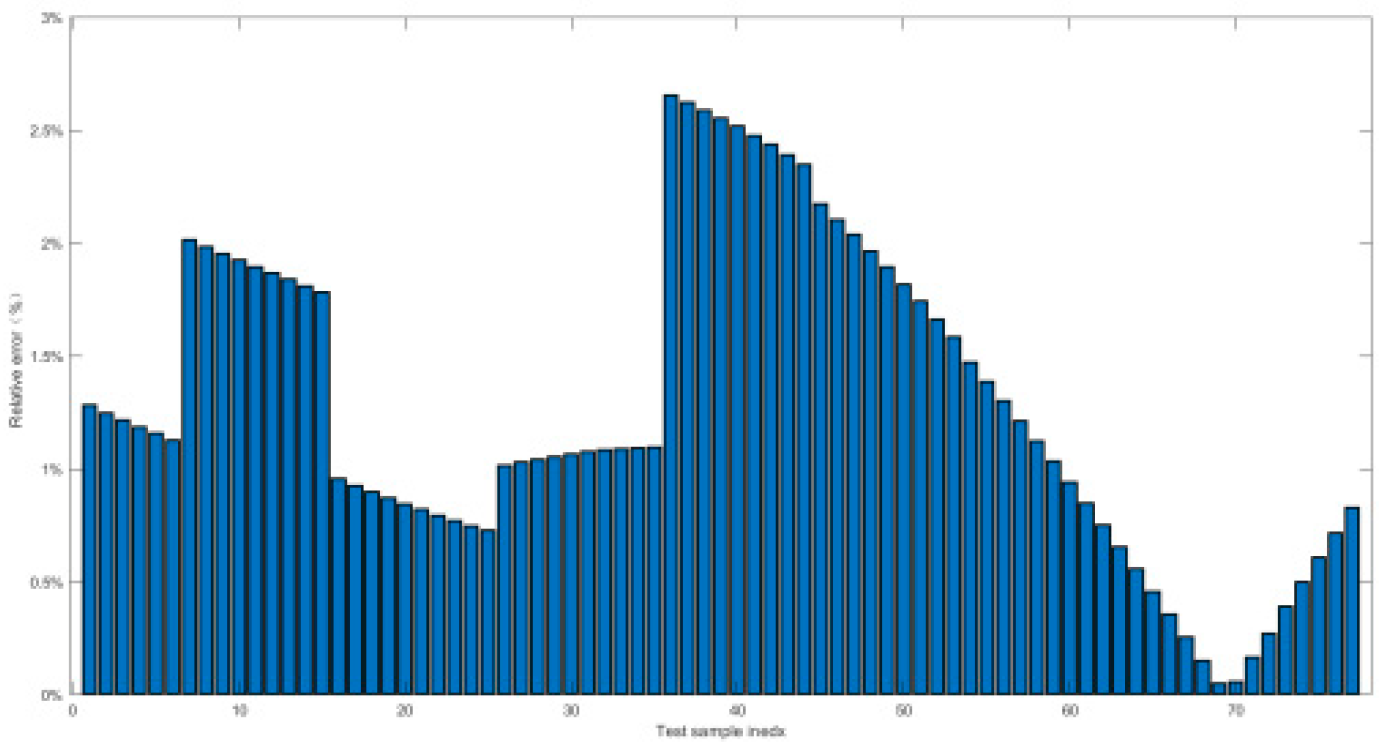

- Third, in section 4.1, the orthogonal experimental data had been trained by Back propagation Neural Network, of which the statistical indicators were between 10e-2 and 10e-13, the relative errors of prediction was less than 3%, and the prediction error accuracy was 100%.

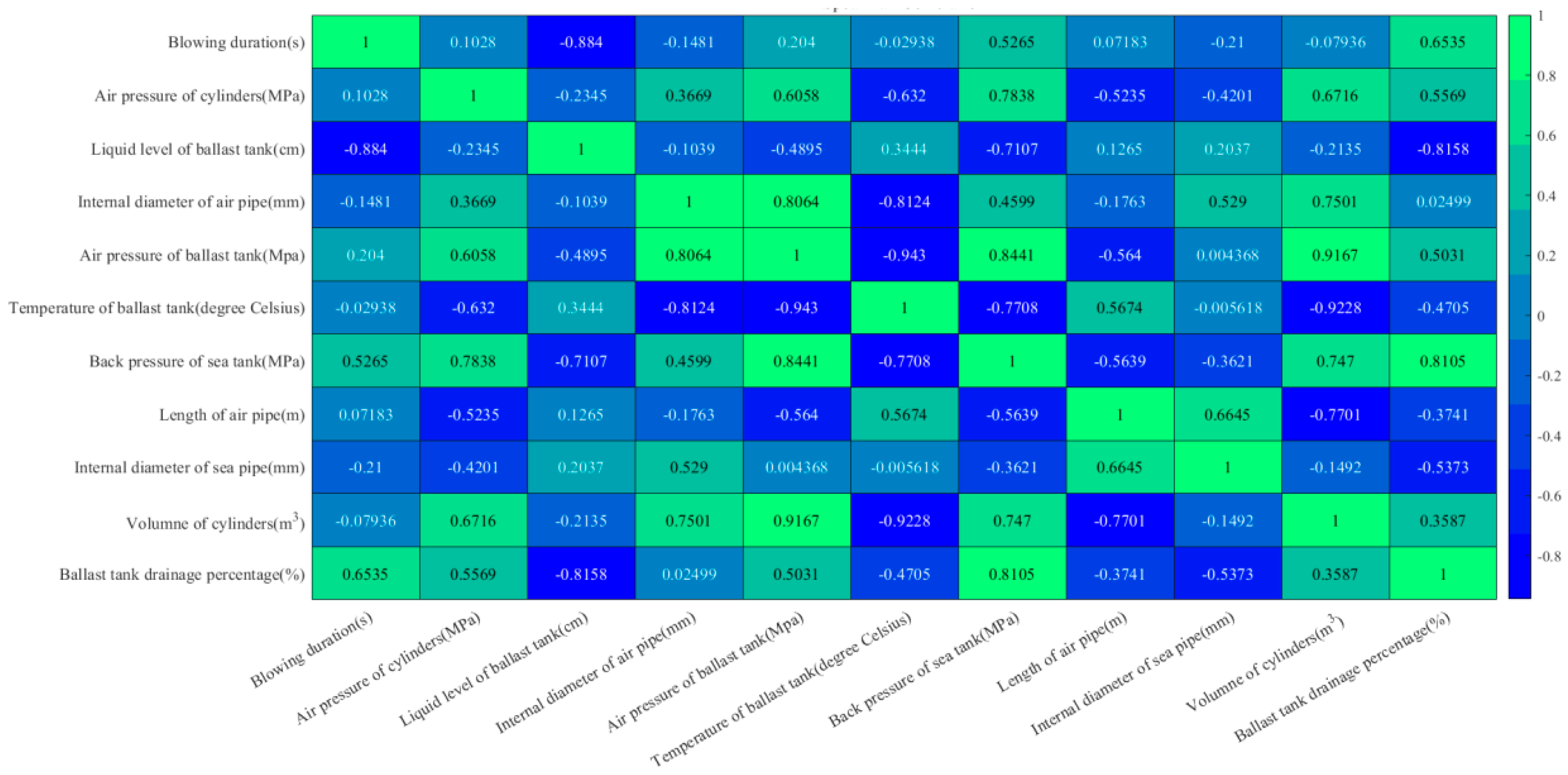

- Fourth, in section 4.2, through Pearson correlation analysis based on orthogonal experimental data, the correlation coefficient between individual factor and blowing had been explored, forming in-depth supplements to the conclusions of orthogonal experiments.

2. Proportional Short-Circuit Blowing Model Test Bench and Orthogonal Experiments Design

2.1. Detailed Setup of Model Test Bench

2.2. Orthogonal Experiment Design

3. Orthogonal Experimental Data Analysis

3.1. Analysis of Extreme Variance

- First, 500L cylinder group volume provided the optimal balance of gas-water interactions in the ballast tank in the context of the other factors available, and it was most conducive to provide sufficient high-pressure gas to enhance the blowing effect [3].

- Second, 20m gas supply pipeline length could satisfy the sufficient gas mass flowing into the ballast tank per unit time with the existing combination of other factors [23];

- Third, 200mm, corresponding to the maximum flowing area of the sea valve, under the same conditions it could maximize the discharging volume of water during per unit time [24];

- Fourth, 15s, corresponding to the maximum blowing duration, ensured that the gas flowing into the ballast tank to the maximum extent;

- Fifth, 10 mm, corresponding to the maximum inner diameter of the gas supply pipe, ensured that the maximum gas mass flowing into the ballast tank during per unit time;

- Sixth, 20MPa was the maximum blowing pressure of cylinder group and 0.2MPa was the minimum back pressure, which can maximize the blowing effect [19].

3.2. Analysis of Variance

4. BP Neural Network and Pearson Correlation Analysis

4.1. Model Setting

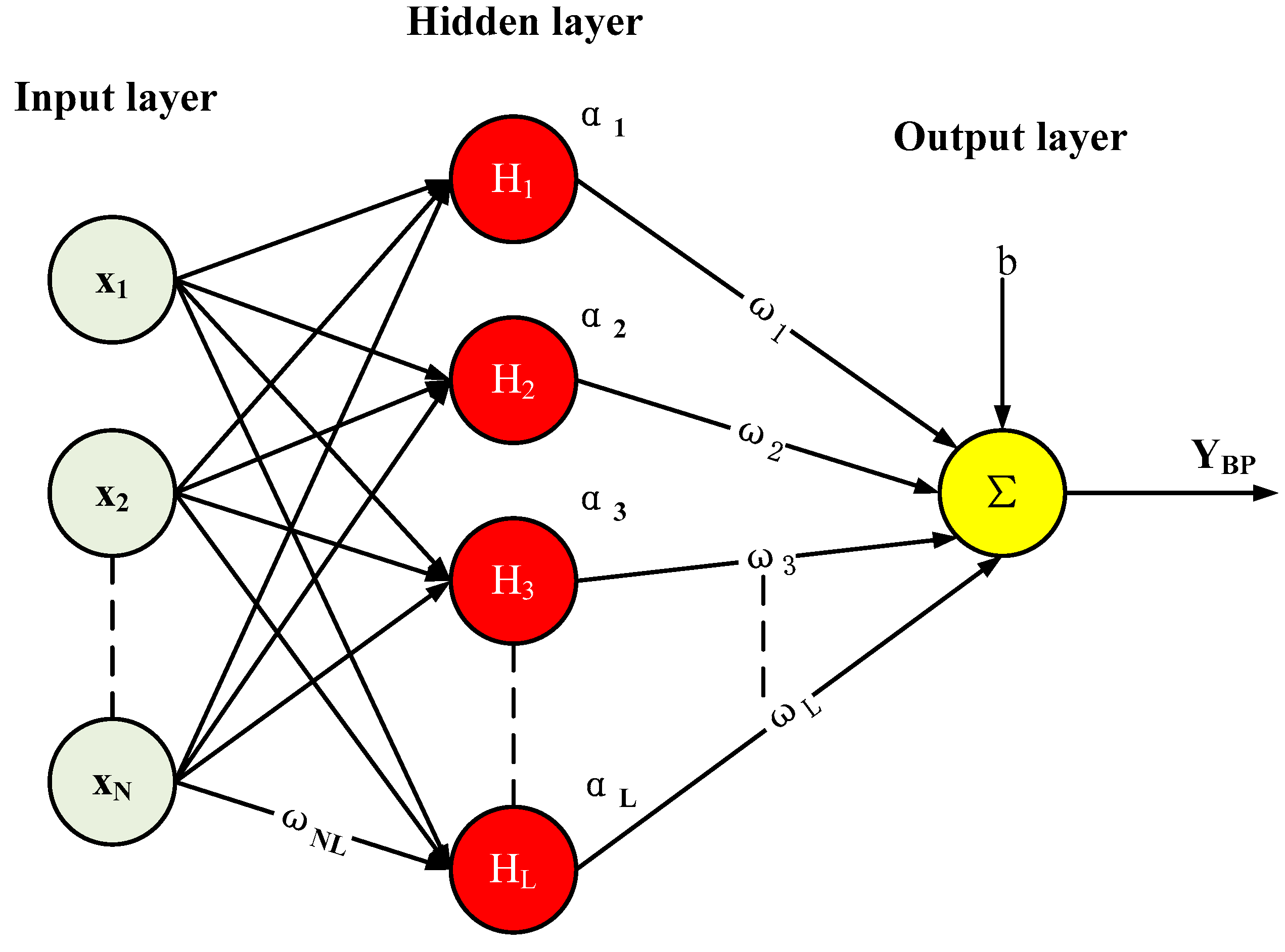

4.1.1. Principles of Mathematics

4.1.2. Evaluation Indicators

- The precision percentage (PP%), 1 is the indicator function, which is 1 if the condition in parentheses is satisfied with, and 0 otherwise;

- The relative error δ, which identifies the percentage of the ratio between the absolute value of subtraction from the Xi to Yi and the absolute value of Xi;

- The square sum of errors, ESSE, measures the fit between the Yi and Xi. The smaller the value is, the better the model is. But, this metric tends to ignore the effect of model complexity;

- The mean absolute error, EMAE, calculates the average of the absolute value between Yi and Xi. The smaller the value is, the better the model is. But, it can not characterize the direction of the error;

- The mean absolute percentage error EMAP, measures the error between datasets of different magnitudes by calculating the average of sum of the absolute ratio between the prediction error and Xi. Its limitations are reflected in the distribution errors when Xi is zero;

- The mean square error EMSE, reflects the average of the square sum of the prediction errors, but it is too sensitive to large error which may easily cause over-fittings;

- The root mean square Error ERMSE, which represents the square root of EMSE, is a standard measure of the difference between the Yi and Xi, and is less sensitive to errors than EMSE. But, it does not accurately measure the magnitude of the error when the actual values are very small;

- Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient, R, has a value between -1 and 1, where 0-1 can be subdivided as below: 0.0-0.2 referred to as very weak or no correlation, 0.2-0.4 referred to as a weak correlation, 0.4-0.6 referred to as a moderate correlation, 0.6-0.8 referred to as a strong correlation, and 0.8-1.0 referred to as a very strong correlation; and the same is true for the division of the -1-0 interval.

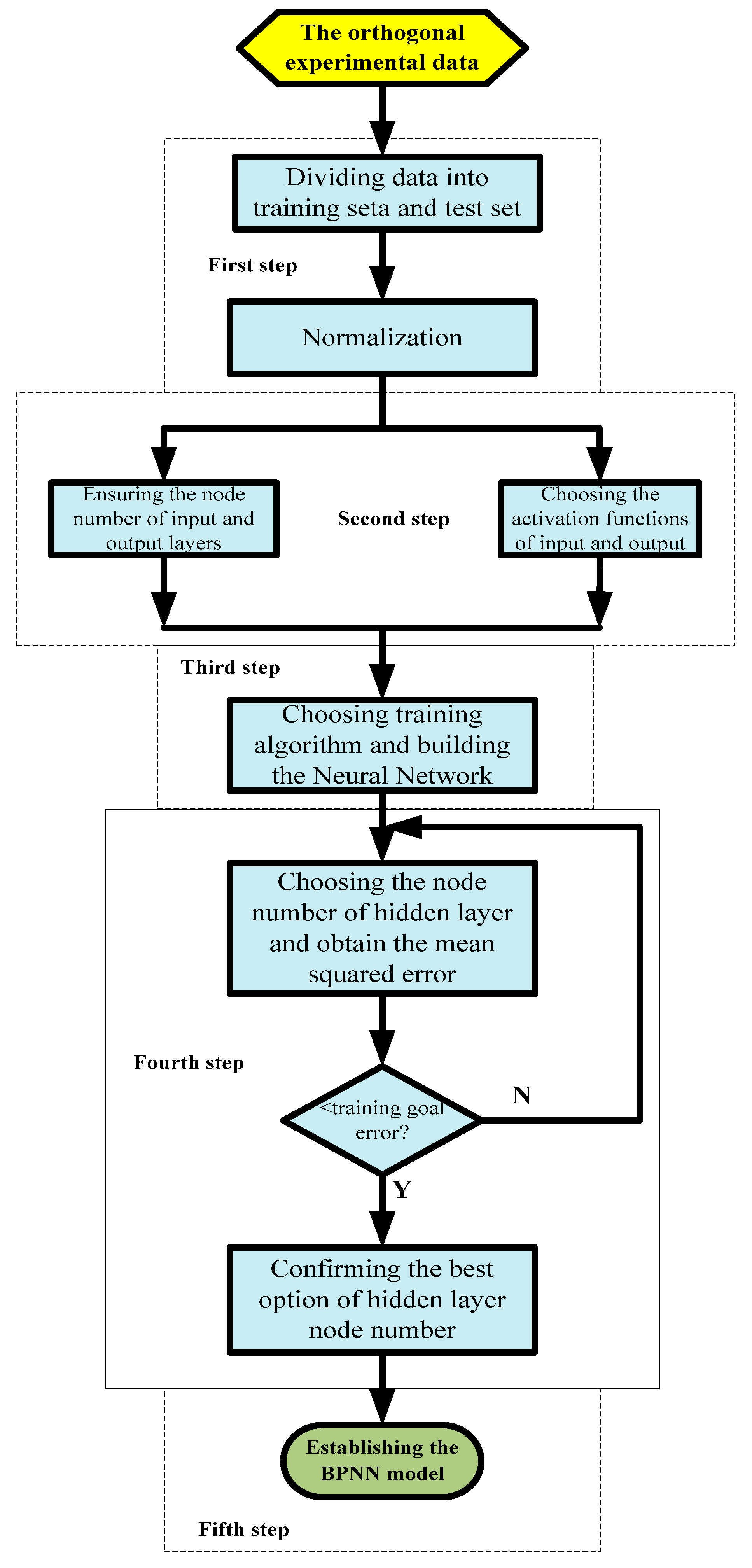

4.1.3. Proposing Algorithm

- First, collecting the orthogonal experimental data and dividing them into training set and testing set. Then, normalizing them so as to capture the real characteristics, excluding the scale restriction of the data set [26].

- Second, ensuring node numbers of input and output based on criteria of section 4.1.1, choosing activation functions of input and output as tansig and purelin by default.

- Third, choosing training algorithm of Levenberg-Marquard and building the neural network, whose parameters include training epochs of 1000, learning rate of 0.01 and minimal training goal error of 1e-5.

- Fourth, choosing the number of hidden layer based on equation (13) and using the prepared neural network to obtain mean squared error. Under condition that when it is below training goal error, the corresponding node number of hidden layer will be confirmed as the best option.

- Fifth, confirming the BPNN model including the data and information above and beginning predictions.

- Sixth, arranging the data set into matrix and calculate Pearson’s linear correlation coefficients, generating heat map.

| Algorithm 1 Detailed code of BPNN and Pearson Analysis |

|

%First step, setting the training set and test set input=data_total(:,1:end-1); %input output=data_total(:,end); %output trainNum=length(data(:,end)); % Number of training set testNum=length(exp(:,end)); %Number of test set input_train=input(1:trainNum,:)’; %input of training set output_train=output(1:trainNum,:)’; %output of training set input_test=input(trainNum+1:trainNum+testNum,:)’; %input of test set output_test=output(trainNum+1:trainNum+testNum,:)’; %output of test set [inputn,inputps]=mapminmax(input_train,0,1); %Normalization of train set input [outputn,outputps]=mapminmax(output_train); %Normalization of train set output inputn_test=mapminmax(‘apply’,input_test,inputps); %Normalization of test set input %Second step, ensuring node numbers of input and output layers %Choosing the activation functions of input and output inputnum=size(input,2); %inputnum is the node number of input layer outputnum=size(output,2); %outputnum is the node number of output layer transform_func={‘tansig’,‘purelin’}; %activation functions of input and output %Third step,choosing the training algorithm and building the neural network train_func=‘trainlm’; %training algorithm For hiddennum=fix(sqrt(inputnum+outputnum))+1:fix(sqrt(inputnum+outputnum))+10; net=newff(inputn,outputn,hiddennum,transform_func,train_func );%set the BPNN net.trainParam.epochs=1000; %epochs net.trainParam.lr=0.01; %learning rate net.trainParam.goal=1e-5; %minimal training goal error %Fourth step,obtain the mean squared error and check whether it’s less than 1e-5 net=train(net,inputn,outputn); an0=sim(net,inputn); mse0=mse(outputn,an0); %obtain the mean squared error if mse0<1e-5 hiddennum_best=hiddennum; %obtain the best node number of hidden layer end End %Fifth step,confirming the BPNN model and starting prediction net=newff(inputn,outputn,hiddennum_best,transform_func,train_func); %Sixth step, calculating Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient, generating heat map data_correlation=[input,output]; data_correlation1=[input,output]; rho=corr([data_correlation;data_correlation1],‘type’,‘pearson’); %Pearson’s linear %correlation analysis string_name={‘blowing duration(s)’,‘air pressure of cylinders(MPa)’,‘liquid level of ballast tank(cm)’,‘air volume of ballast tank(m^3)’,‘air pressure of ballast tank(MPa)’,‘temperature of ballast tank(degree Celsius)’,‘back pressure of sea tank(MPa)’,‘Length of air pipe(m)’,‘Internal diameter of sea pipe(mm)’,‘Volume of cylinders(m^3)’,‘Ballast tank drainage percentage(%)’}; %String name of heat map xvalues=string_name;yvalues=string_name; h=heatmap(xvalues,yvalues,rho); %Generating the heat map |

4.2. Computation Analysis

4.2.1. Evaluation of Working Conditions

4.2.2. Relative Error and Prediction Accuracy Analysis

4.2.3. Correlation Analysis of Individual Influencing Factor

- First, blowing duration was 0.6535, which was a strong positive correlation. Theoretically, the longer the duration of gas supply was, the more the amount of water had been blew off [28];

- Second, sea tank back pressure was 0.8105,which was an extremely strong positive correlation. It indicated that the drainage of the ballast tank was closely related to the outboard back pressure with a very complicated relationship. Firstly, the magnitude of back pressure affected the pressure change of blowing in the ballast tank [29,30]. Then, the magnitude of back pressure affected dynamic balance between gas and water and the corresponding blowing efficiency [2,30]. Finally, the back pressure magnitude affected the energy consumption and system efficiency during blowing [27,29];

- Third, the volume of the gas cylinder group was 0.3587, which was a weak positive correlation. According to the aerodynamic computation theories, there was a certain direct relationship between gas consumption and drainage of the ballast tank [31];

- Fourth, the gas pressure of cylinder group was 0.5569, which was a moderately strong positive correlation. Theoretically, the gas pressure of cylinder group can significantly affect the blowing effect [28];

- Fifth, the inner diameter of gas supply pipeline was 0.02499, which was a very weak positive correlation. Theoretically, the larger the inner diameter was, the higher the gas supply efficiency would be during per unit time, which was conducive for a faster establishment of the gas cushion at top of the ballast tank, causing improvement of the blowing [32]. However, because the inner diameter of the gas supply pipeline in this bench was only 6mm, 8mm and 10mm, and its length was 0.3m, which had size restriction on the overall flowing;

- Sixth, the gas supply pipeline length was -0.3741, which was a medium-strength negative correlation. It proved that the shorter the pipeline length was, the better the blowing effect was with other constant conditions. And, it further proved the advantage of the short-circuit blowing over the conventional blowing [32];

- Seventh, the internal diameter of the sea valve was 0.5373, which was moderately positively correlated. It indicated that enhancing the flowing area of the sea valve would increase the drainage during per unit time and improved the blowing efficiency [28].

4.2.4. Comparison Analysis with Existing Resolutions

- In reference [10,11], the small-scale short-circuit experimental test bench was focused on the flowing-rate of high-pressure gas cylinder group, which was closely related with drainage percentage of ballast tank, and the relative error was 8% which was much larger than maximal relative error in Table 7 in section 4.2.2;

- From the comparison analysis can we infer that the BPNN method has a much higher prediction accuracy than traditional numerical modeling, and there were none of statistical correlation researches above between manipulation factors and blowing process in section 3.1, section 3.2 and section 4.2.3.

5. Conclusion

- First, analyzing the orthogonal experimental data by extreme variance method, the optimal combination of multiple factors including the blowing duration(39.16%), back pressure(33.35%), gas blowing pressure of cylinder group(10.94%) and sea valve flowing area(9.02%). Of which, the blowing duration was the most sensitive with F-ratio of 3.27;

- Second, the training and prediction of orthogonal experimental data had been carried out by BPNN. It had been proved that the high nonlinear fitting ability of BPNN could well forecast the high-pressure gas short-circuit blowing, of which the statistical evaluation indicators were distributed from 10e-2 to 10e-13, the relative errors were within the 3% threshold, and the prediction accuracy was all up to 100%. BPNN method had been proved to be a reasonable AI prediction method for submersible short-circuit blowing;

- Third , the BPNN training set data was collected for Pearson correlation analysis between individual factor and the result, which showed that the ballast blowing duration (0.6535), the sea tank back pressure (0.8105), the gas cylinder group pressure (0.5569), and the internal diameter of the sea valve (0.5373) all demonstrated positive correlations, whereas the negative correlation (-0.3741) of the gas supply pipeline length demonstrated higher efficiency of short-circuit blowing than conventional blowing.

- First, in terms of the blowing method, short-circuit blowing provides higher blowing efficiency than conventional method because of shorter length of gas supply pipeline;

- Second, in terms of engineering design, Multiple manipulation factors, including larger volume and gas pressure of cylinder group, flowing area of sea valve have direct positive impacts on blowing. Additionally, reasonable gas supply pipeline specification, including inner diameter and length should be set;

- Third, in terms of operations, ensuring reasonable blowing duration to achieve the best effect according to outboard back pressure changing when blowing.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Nomenclature1. Orthogonal experiment | |

| The sum of the experimental results of either factor | |

| The ratio of the sum of the experimental results of either factor to total number of levels | |

| The average of the results of all orthogonal experiments | |

| The offset between and | |

| The extreme variance | |

| The total square sum of the deviations of all the experimental results, i.e., the variance | |

| The square sum of individual factor x’s deviations, i.e., the variance | |

| The sum of squared error deviations | |

| The total degree of freedom | |

| m | The number of levels of each factor |

| n | The number of orthogonal experiments |

| The degree of freedom of each factor | |

| The error degree of freedom | |

| The mean square of | |

| The mean square of | |

| The F-ratio of individual factor x | |

| Nomenclature2. BPNN and Pearson correlation analysis | |

| L | The number of neurons in the hidden layer |

| N | The number of neurons in the input layer |

| M | The number of neurons in the output layer |

| a | Constant taken to be between 1 and 10 |

| ωj | The weight of the the j-th hidden neuron |

| b | The bias term of the output neuron |

| YBP(t) | Output of the BPNN |

| Hj(t) | The output of the j-th hidden neuron |

| ωij | The connection weight between the i-th input neuron and the j-th hidden neuron |

| xi(t) | The input from the i-th neuron at time t |

| αj | The bias term for the j-th hidden neuron |

| f(x) | The activation function of the hidden layer |

| α | The rake ratio of activation function |

| PP% | Predictive accuracy |

| δ | Relative Error Percentage |

| ESSE | Sum of Squared Errors |

| EMAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| EMAP | Mean absolute Percentage Error |

| EMSE | Mean Square Error |

| ERMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| R | Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient |

| S | The number of data |

| Xi | the actual value |

| the average of the actual values | |

| Yi | the predicted value |

| the average of the actual values | |

References

- Zhang, J.H.; Hu, K.; Liu, C.B. Numerical simulation on compressed gas blowing ballast tank of submarine. Journal of Ship Mechanics 2015, 19, 363–368. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Q.; Lin, B.; Zhang, W.; Qian, Y.; Zou, W.; Zhang, K. Simulation and experimental verification of main ballast tank blowing based on short circuit blowing model. Chinese Journal of Ship Research 2022, 17, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, D. Experiment and Mathematics Model of High Pressure Air Blowing. Chinese Journal of Ship Research 2014, 9, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, H.; Liu, G.; Hu, K. Numerical simulation of blowing characteristics of submarine main ballast tanks using VOF model. Journal of Ordnance Equipment Engineering 2022, 43, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-H.; Hu, K.; Huang, H.-F.; Wei, J.-G. Analysis of the influence of 90° elbow on the pressure loss along the submarine high pressure gas pipe. Ship Science and Technology 2020, 42, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.-Q.; Yang, F. Emergency recovery of submarine with flooded compartment. Journal of Ship Mechanics 2010, 14, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wilgenhof, J.D.; Giménez, J.J.C.; Peláez, J.G. Performance of the main ballast tank blowing system. In Undersea Defense Technology Conference 2011; UDT Europe: London, Britain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Yu, J.Z.; Cheng, D. , et al. Theoretical analysis and experimental validation on gas jet blowing-off process of submarine emergency. Journal of Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics 2009, 35, 411–416. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Yu, J.Z.; Cheng, D. , et al. Numerical simulation and experimental validation on gas jet blowing-off process of submarine emergency. Journal of Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics 2010, 36, 227–230. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Pu, J.Y.; Li, Q.X. , et al. The experiment research of submarine high-pressure air blowing off main ballast tanks. Journal of Harbin Engineering University 2013, 34, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, Q.X.; Wu, X.J. , et al. The establishing of pipe flow model and experimental analysis on submarine high pressure air blowing system. Ship Science and Technology 2015, 37, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-L.; Fang, Y.-L.; Su, G.-H.; Tian, W.-X.; Qiu, S.-Z. A high temperature and high flowing rate gas flow heat transfer experimental device and experimental method. 201910377151.1[P]. 2020-7-10. (in Chinese)

- Yang, X.-Q.; Ren, Z.-L. Design and Analyses of Orthogonal Test with Null Ratio Factor. Journal of Biomathematics 2006, 2, 291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Xu, Z.; Teng, K.; Yan, S.; Zhang, L. Process Parameters Optimization for 2AL2 Aluminum Alloy Laser Cutting Based on Orthogonal Experiment and BP Neural Network. Machine Tool&Hydraulics 2018, 46, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. Ship structure optimization based on PSO-BP neural network; Dalian Maritime University, June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Han, D.; Guo, C. Modeling of the principal dimensions of large vessels based on a BPNN trained by an improved PSO. Journal of Harbin Engineering University 2012, 33, 806–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pān, J.-S.; Shàn, P. Fundamentals of Gas Dynamics, (in Chinese), 1st ed.; National Defense Industry Press, 2017; p. 164. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, H.-Y. Times Series Forecasting based on Feed-forward Neural Networks; Nanjing University, May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Design and Key Technology Research on High Pressure Pneumatic Blowing Valve With Differential Pressure Control; Wuhan Institute of Technology, May 2015.

- Shao, D.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Sun, S.; Sun, C.; Xu, L. Dynamic measurement of gas volume fraction in a CO2 pipeline throughcapacitive sensing and data driven modelling. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 2020, 94, 102950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Yu, Y. Optimization of Gas-liquid Two-phase Flow Liquid Hold-up Prediction Model with BP Neural Network Based on Genetic Algorithm. Journal of Xi’an Shiyou University (Natural Science Edition) 2019, 34, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Research on Temperature Prediction Based on Artificial Neural Network Applied in High-pressure Airtight Detection; University of Science and Technology, May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Assani, N.; Matic, P.; Kastelan, N.; Cavka, I.R. A review of artificial neural networks application in Maritime Industry. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 139823–139848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, Q.W.; Li, H.L.; Li, J.Y.; Liu, T.C.; Chen, Y.T.; Ai, M.Y.; Dong, J.Y. A Bacl Propagation Neural Network-Based Radiometric Correction Method (BPNNRCM) for UAV Multispectral Image. IEEE Journal Of Selected Topics In Applied Earth Observations And Remote Sensing 16, 112–125. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. Variance Analysis of Orthogonal Experimental Design; Northeast Forestry University, April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Analysis of Normalization for Deep Neural Networks; Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications, 2019; Volume 12, p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, R. ; Mukherjee; et al. The generalized higher criticism for testing SNP-Set Effects in Genetic Association studies. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Q.; Lin, B.-Q.; Zhang, W.-L. Analysis of the blowing process of high pressure air from the bottom into the main ballast tank. Ship Science And Technology 2020, 42, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Q.; Lin, B.-Q.; Zhang, W.-L.; Chen, S.; Zou, W.-T.; Zhang, K. CFD simulation and experimental verification of blowing process of main ballast tank. Journal of Ship Mechanics 2023, 27, 218–226. [Google Scholar]

- Font, R.; Garcia-Peláez, J. On a submarine hovering system based on blowing and venting of ballast tanks. Ocean Engineering 2013, 72, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-J.; Yang, P.; Li, S.; Liu, K.; Wang, K.; Zhou, X. Online modeling and prediction of maritime autonomous surface ship maneuvering motion under ocean waves. Ocean Engineering 2023, 276, 114183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Pu, J.-Y.; Jin, T. Research on system model of high pressure air blowing submarine’s main ballast tanks. Ship Science And Technology 32, 26–30. [CrossRef]

| Index | Apparatus | Main Parameters | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Air compressor | Maximal air inflation pressure is 20.0MPa | |

| 2 | Gas cylinder group | Maximal air working pressure, is 35MPa,volume is 750L | gas source of blowing and back pressure of sea tank |

| 3 | Ballast tank | Volume is 1.2m3 and able to handle pressure of 7MPa | |

| 4 | Sea tank | Volume is 13m3 and able to handle pressure of 5MPa | The back pressure is larger than the maximum working depth of the real ship |

| 5 | Gas supply pipeline | Setting up three kinds of length specifications: 10m, 20m and 30m | Inlet with three replaceable pipe sections of 6mm, 8mm and 10mm internal diameters, 0.3m in length. |

| 6 | Sea pipeline | Setting of 125mm, 150mm and 200mm internal diameters | Connection of ballast tank outlet and sea water tank inlet |

| Index of experiment | Influencing factors | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 6 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 7 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| 8 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| 9 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 10 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 11 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 12 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 13 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| 14 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| 15 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 16 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| 17 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 18 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Parameters | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1 | 213.56% | 263.62% | 197.98% | 105.98% | 226.47% | 189.25% | 329.18% |

| K2 | 243.51% | 225.09% | 224.78% | 227.95% | 213.33% | 230.70% | 216.61% |

| K3 | 217.80% | 260.53% | 252.11% | 340.94% | 235.07% | 254.92% | 129.08% |

| k1 | 35.59% | 43.94% | 33.00% | 17.66% | 37.74% | 31.54% | 54.86% |

| k2 | 40.58% | 37.52% | 37.46% | 37.99% | 35.56% | 38.45% | 36.10% |

| k3 | 36.30% | 43.42% | 42.02% | 56.82% | 39.18% | 42.49% | 21.51% |

| T1 | -1.90% | 6.44% | -4.50% | -19.83% | 0.25% | -5.95% | 17.37% |

| T2 | 3.09% | 0.02% | -0.03% | 0.50% | -1.94% | 0.96% | -1.39% |

| T3 | -1.19% | 5.93% | 4.53% | 19.33% | 1.69% | 4.99% | -15.98% |

| Rx | 4.99% | 6.42% | 9.02% | 39.16% | 3.62% | 10.94% | 33.35% |

| Priority | D>G>F>C>B>A>E | ||||||

| Optimal level | A2 | B1 | C3 | D3 | E3 | F3 | G1 |

| Optimal combination | A2B1C3D3E3F3G1 | ||||||

| Parameters | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1 | 213.56% | 263.62% | 197.98% | 105.98% | 226.47% | 189.25% | 329.18% |

| K2 | 243.51% | 225.09% | 224.78% | 227.95% | 213.33% | 230.70% | 216.61% |

| K3 | 217.80% | 260.53% | 252.11% | 340.94% | 235.07% | 254.92% | 129.08% |

| k1 | 35.59% | 43.94% | 33.00% | 17.66% | 37.74% | 31.54% | 54.86% |

| k2 | 40.58% | 37.52% | 37.46% | 37.99% | 35.56% | 38.45% | 36.10% |

| k3 | 36.30% | 43.42% | 42.02% | 56.82% | 39.18% | 42.49% | 21.51% |

| T1 | -1.90% | 6.44% | -4.50% | -19.83% | 0.25% | -5.95% | 17.37% |

| T2 | 3.09% | 0.02% | -0.03% | 0.50% | -1.94% | 0.96% | -1.39% |

| T3 | -1.19% | 5.93% | 4.53% | 19.33% | 1.69% | 4.99% | -15.98% |

| Sx | 0.11% | 1.25% | 0.61% | 11.80% | 0.00% | 1.06% | 9.05% |

| fx | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 0.05% | 0.62% | 0.30% | 5.90% | 0.00% | 0.53% | 4.53% | |

| F-ratio | 0.03 | 0.35 | 0.17 | 3.27 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 2.51 |

| Critical value,α=0.05 | 3.24 | 3.24 | 3.24 | 3.24 | 3.24 | 3.24 | 3.24 |

| Effect | insignificant | insignificant | insignificant | significant | insignificant | insignificant | insignificant |

| Index | Evaluation indicators | Data | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working condition1 | Sum of Square Errors, ESSE | 1.8906e-12 | Fit between predicted and actual values |

| Mean Absolute Error, EMAE | 4.4939e-7 | Average of the absolute value between the predicted values and actual values | |

| Mean absolute Percentage Error, EMAP | 0.00055853 | Error between datasets of different magnitudes | |

| Mean Square Error, EMSE | 2.7008e-13 | Average of the sum of squares of the prediction errors | |

| Root Mean Square Error, ERMSE | 5.1969e-7 | The square root of the mean of the Square sum of the predicted and actual values | |

| Working condition2 | Sum of Square Errors, ESSE | 0.00012022 | Fit between predicted and actual values |

| Mean Absolute Error, EMAE | 0.001514 | Average of the absolute value between the predicted values and actual values | |

| Mean absolute Percentage Error, EMAP | 0.0036052 | Error between datasets of different magnitudes | |

| Mean Square Error, EMSE | 2.4043e-6 | Average of the sum of squares of the prediction errors | |

| Root Mean Square Error, ERMSE | 0.0015506 | The square root of the mean of the Square sum of the predicted and actual values | |

| Working condition3 | Sum of Square Errors, ESSE | 0.00016132 | Fit between predicted and actual values |

| Mean Absolute Error, EMAE | 0.0011673 | Average of the absolute value between the predicted values and actual values | |

| Mean absolute Percentage Error, EMAP | 0.0029131 | Error between datasets of different magnitudes | |

| Mean Square Error, EMSE | 1.9436e-6 | Average of the sum of squares of the prediction errors | |

| Root Mean Square Error, ERMSE | 0.0013941 | The square root of the mean of the Square sum of the predicted and actual values | |

| Working condition4 | Sum of Square Errors, ESSE | 0.0061557 | Fit between predicted and actual values |

| Mean Absolute Error, EMAE | 0.0096929 | Average of the absolute value between the predicted values and actual values | |

| Mean absolute Percentage Error, EMAP | 0.023948 | Error between datasets of different magnitudes | |

| Mean Square Error, EMSE | 0.00012311 | Average of the sum of squares of the prediction errors | |

| Root Mean Square Error, ERMSE | 0.011096 | The square root of the mean of the Square sum of the predicted and actual values | |

| Working condition5 | Sum of Square Errors, ESSE | 0.001105 | Fit between predicted and actual values |

| Mean Absolute Error, EMAE | 0.0046973 | Average of the absolute value between the predicted values and actual values | |

| Mean absolute Percentage Error, EMAP | 0.0059697 | Error between datasets of different magnitudes | |

| Mean Square Error, EMSE | 2.21e-5 | Average of the sum of squares of the prediction errors | |

| Root Mean Square Error, ERMSE | 0.004701 | The square root of the mean of the Square sum of the predicted and actual values | |

| Working condition6 | Sum of Square Errors, ESSE | 0.0064002 | Fit between predicted and actual values |

| Mean Absolute Error, EMAE | 0.0080078 | Average of the absolute value between the predicted values and actual values | |

| Mean absolute Percentage Error, EMAP | 0.028729 | Error between datasets of different magnitudes | |

| Mean Square Error, EMSE | 9.1432e-5 | Average of the sum of squares of the prediction errors | |

| Root Mean Square Error, ERMSE | 0.009562 | The square root of the mean of the Square sum of the predicted and actual values | |

| Working condition7 | Sum of Square Errors, ESSE | 5.5945e-5 | Fit between predicted and actual values |

| Mean Absolute Error, EMAE | 0.00081209 | Average of the absolute value between the predicted values and actual values | |

| Mean absolute Percentage Error, EMAP | 0.004057 | Error between datasets of different magnitudes | |

| Mean Square Error, EMSE | 1.1189e-6 | Average of the sum of squares of the prediction errors | |

| Root Mean Square Error, ERMSE | 0.0010578 | The square root of the mean of the Square sum of the predicted and actual values | |

| Working condition8 | Sum of Square Errors, ESSE | 0.00635 | Fit between predicted and actual values |

| Mean Absolute Error, EMAE | 0.0095017 | Average of the absolute value between the predicted values and actual values | |

| Mean absolute Percentage Error, EMAP | 0.011281 | Error between datasets of different magnitudes | |

| Mean Square Error, EMSE | 0.00010583 | Average of the sum of squares of the prediction errors | |

| Root Mean Square Error, ERMSE | 0.010288 | The square root of the mean of the Square sum of the predicted and actual values | |

| Working condition9 | Sum of Square Errors, ESSE | 0.00030943 | Fit between predicted and actual values |

| Mean Absolute Error, EMAE | 0.0024449 | Average of the absolute value between the predicted values and actual values | |

| Mean absolute Percentage Error, EMAP | 0.0061119 | Error between datasets of different magnitudes | |

| Mean Square Error, EMSE | 6.1887e-6 | Average of the sum of squares of the prediction errors | |

| Root Mean Square Error, ERMSE | 0.0024877 | The square root of the mean of the Square sum of the predicted and actual values | |

| Working condition10 | Sum of Square Errors, ESSE | 7.5391e-5 | Fit between predicted and actual values |

| Mean Absolute Error, EMAE | 0.0011243 | Average of the absolute value between the predicted values and actual values | |

| Mean absolute Percentage Error, EMAP | 0.0028055 | Error between datasets of different magnitudes | |

| Mean Square Error, EMSE | 1.5078e-6 | Average of the sum of squares of the prediction errors | |

| Root Mean Square Error, ERMSE | 0.0012279 | The square root of the mean of the Square sum of the predicted and actual values | |

| Working condition11 | Sum of Square Errors, ESSE | 8.0629e-5 | Fit between predicted and actual values |

| Mean Absolute Error, EMAE | 0.0016049 | Average of the absolute value between the predicted values and actual values | |

| Mean absolute Percentage Error, EMAP | 0.0064002 | Error between datasets of different magnitudes | |

| Mean Square Error, EMSE | 5.0393e-6 | Average of the sum of squares of the prediction errors | |

| Root Mean Square Error, ERMSE | 0.0022448 | The square root of the mean of the Square sum of the predicted and actual values | |

| Working condition12 | Sum of Square Errors, ESSE | 0.00011633 | Fit between predicted and actual values |

| Mean Absolute Error, EMAE | 0.0011062 | Average of the absolute value between the predicted values and actual values | |

| Mean absolute Percentage Error, EMAP | 0.0066337 | Error between datasets of different magnitudes | |

| Mean Square Error, EMSE | 1.2245e-6 | Average of the sum of squares of the prediction errors | |

| Root Mean Square Error, ERMSE | 0.0011066 | The square root of the mean of the Square sum of the predicted and actual values | |

| Working condition13 | Sum of Square Errors, ESSE | 0.00021467 | Fit between predicted and actual values |

| Mean Absolute Error, EMAE | 0.0012303 | Average of the absolute value between the predicted values and actual values | |

| Mean absolute Percentage Error, EMAP | 0.0015655 | Error between datasets of different magnitudes | |

| Mean Square Error, EMSE | 2.9009e-6 | Average of the sum of squares of the prediction errors | |

| Root Mean Square Error, ERMSE | 0.0017032 | The square root of the mean of the Square sum of the predicted and actual values | |

| Working condition14 | Sum of Square Errors, ESSE | 0.00014928 | Fit between predicted and actual values |

| Mean Absolute Error, EMAE | 0.0011504 | Average of the absolute value between the predicted values and actual values | |

| Mean absolute Percentage Error, EMAP | 0.010992 | Error between datasets of different magnitudes | |

| Mean Square Error, EMSE | 1.3951e-6 | Average of the sum of squares of the prediction errors | |

| Root Mean Square Error, ERMSE | 0.0011812 | The square root of the mean of the Square sum of the predicted and actual values | |

| Working condition15 | Sum of Square Errors, ESSE | 0.00017113 | Fit between predicted and actual values |

| Mean Absolute Error, EMAE | 0.0015861 | Average of the absolute value between the predicted values and actual values | |

| Mean absolute Percentage Error, EMAP | 0.0023651 | Error between datasets of different magnitudes | |

| Mean Square Error, EMSE | 2.5542e-6 | Average of the sum of squares of the prediction errors | |

| Root Mean Square Error, ERMSE | 0.0015982 | The square root of the mean of the Square sum of the predicted and actual values | |

| Working condition16 | Sum of Square Errors, ESSE | 0.00094847 | Fit between predicted and actual values |

| Mean Absolute Error, EMAE | 0.0072352 | Average of the absolute value between the predicted values and actual values | |

| Mean absolute Percentage Error, EMAP | 0.017463 | Error between datasets of different magnitudes | |

| Mean Square Error, EMSE | 5.2693e-5 | Average of the sum of squares of the prediction errors | |

| Root Mean Square Error, ERMSE | 0.007259 | The square root of the mean of the Square sum of the predicted and actual values | |

| Working condition17 | Sum of Square Errors, ESSE | 0.00049875 | Fit between predicted and actual values |

| Mean Absolute Error, EMAE | 0.002734 | Average of the absolute value between the predicted values and actual values | |

| Mean absolute Percentage Error, EMAP | 0.0077481 | Error between datasets of different magnitudes | |

| Mean Square Error, EMSE | 9.975e-6 | Average of the sum of squares of the prediction errors | |

| Root Mean Square Error, ERMSE | 0.0031583 | The square root of the mean of the Square sum of the predicted and actual values | |

| Working condition18 | Sum of Square Errors, ESSE | 0.0043433 | Fit between predicted and actual values |

| Mean Absolute Error, EMAE | 0.0063359 | Average of the absolute value between the predicted values and actual values | |

| Mean absolute Percentage Error, EMAP | 0.012839 | Error between datasets of different magnitudes | |

| Mean Square Error, EMSE | 5.6407e-5 | Average of the sum of squares of the prediction errors | |

| Root Mean Square Error, ERMSE | 0.0075104 | The square root of the mean of the Square sum of the predicted and actual values |

| Index | Maximal value of δ | Prediction accuracy PP% |

|---|---|---|

| Working conditon1 | 0.9% | 100% |

| Working conditon2 | 1.5% | 100% |

| Working conditon3 | 1.5% | 100% |

| Working conditon4 | 1.38% | 100% |

| Working conditon5 | 0.52% | 100% |

| Working conditon6 | 2.7% | 100% |

| Working conditon7 | 2.7% | 100% |

| Working conditon8 | 2% | 100% |

| Working conditon9 | 1.5% | 100% |

| Working conditon10 | 0.55% | 100% |

| Working conditon11 | 2.5% | 100% |

| Working conditon12 | 0.8% | 100% |

| Working conditon13 | 0.55% | 100% |

| Working conditon14 | 1.74% | 100% |

| Working conditon15 | 0.23% | 100% |

| Working conditon16 | 1.8% | 100% |

| Working conditon17 | 1.6% | 100% |

| Working conditon18 | 2.7% | 100% |

| Index of literature | Relative error | Researching Objects | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference [2] | 0.53%-39.17% | Peak pressure of ballast tank, which was directly related with drainage percentage | None of statistical correlation researches between manipulation factors and blowing |

| Reference [10,11] | 8% | Flowing-rate of high-pressure gas cylinder group, which was closely related with drainage percentage | |

| Reference [8] | <5% | Drainage percentage by gas jet blowing-off, which was a similar method with short-circuit blowing | |

| Reference [9] | <10% | Drainage percentage by gas jet blowing-off, which was a similar method with short-circuit blowing | |

| This paper | 0.23%-2.7% | Drainage percentage of ballast tank during short-circuit blowing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).