Submitted:

03 September 2024

Posted:

04 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fruit Material

2.2. Nanovesicles Isolation

2.3. Total Antioxidant Activity Assay

2.4. Ascorbic Acid Assay

2.5. ATP Assay Kit

2.6. Catalase Activity Assay

2.7. Citric Acid Assay

2.8. Reduced Glutathione (GSH) Detection and Quantification Assay

2.9. Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Activity Assay

2.10. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis

2.11. Dynamic Light Scattering

2.12. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.13. Cell line

2.14. Staining Protocol of PDEVs with a fluorescent probe (DIl 1,1′-Dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate)

2.15. Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Measurement

2.16. Mitochondrial Superoxide Assay

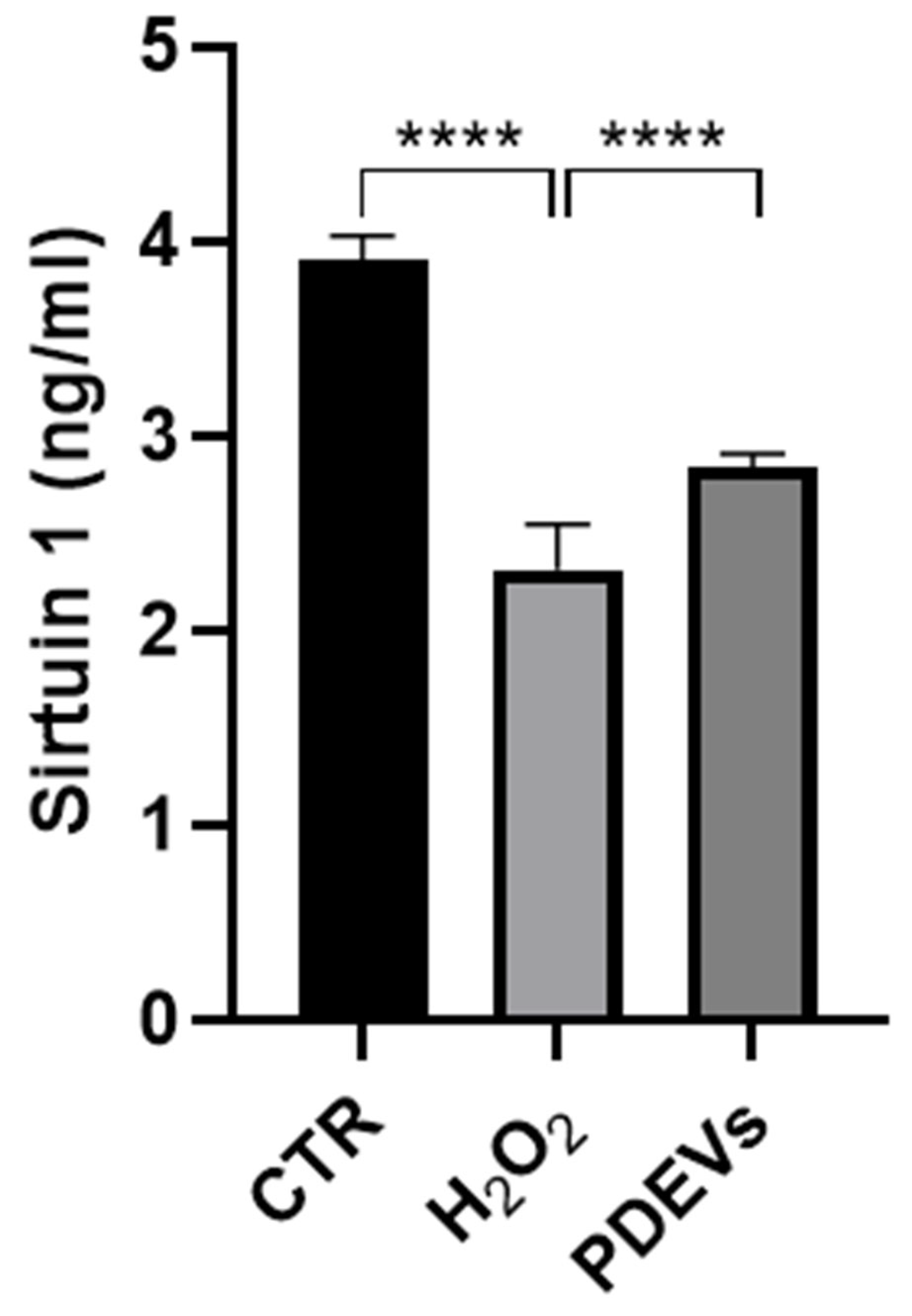

2.17. Sirtuin quantification

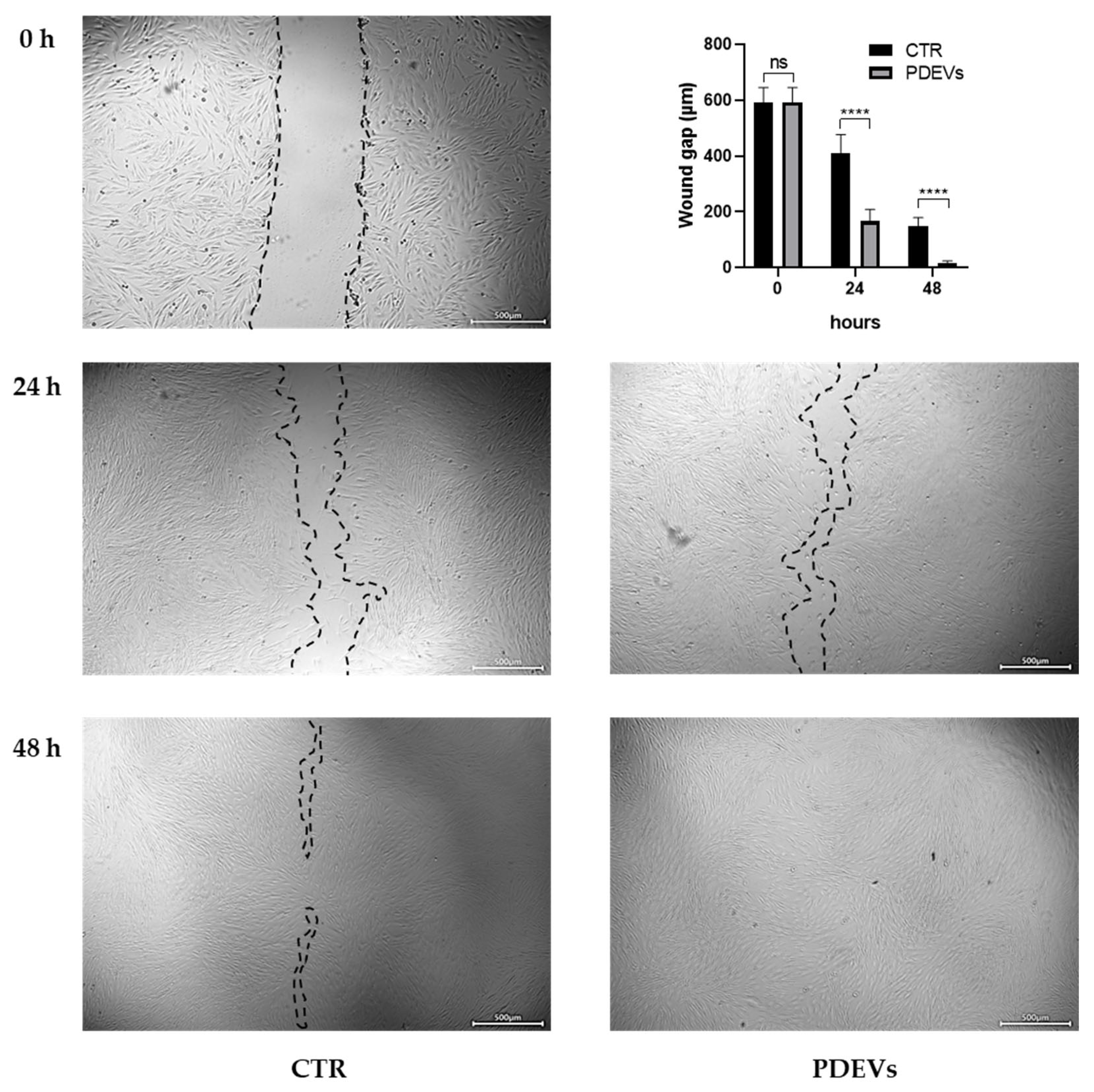

2.18. Wound healing Assay

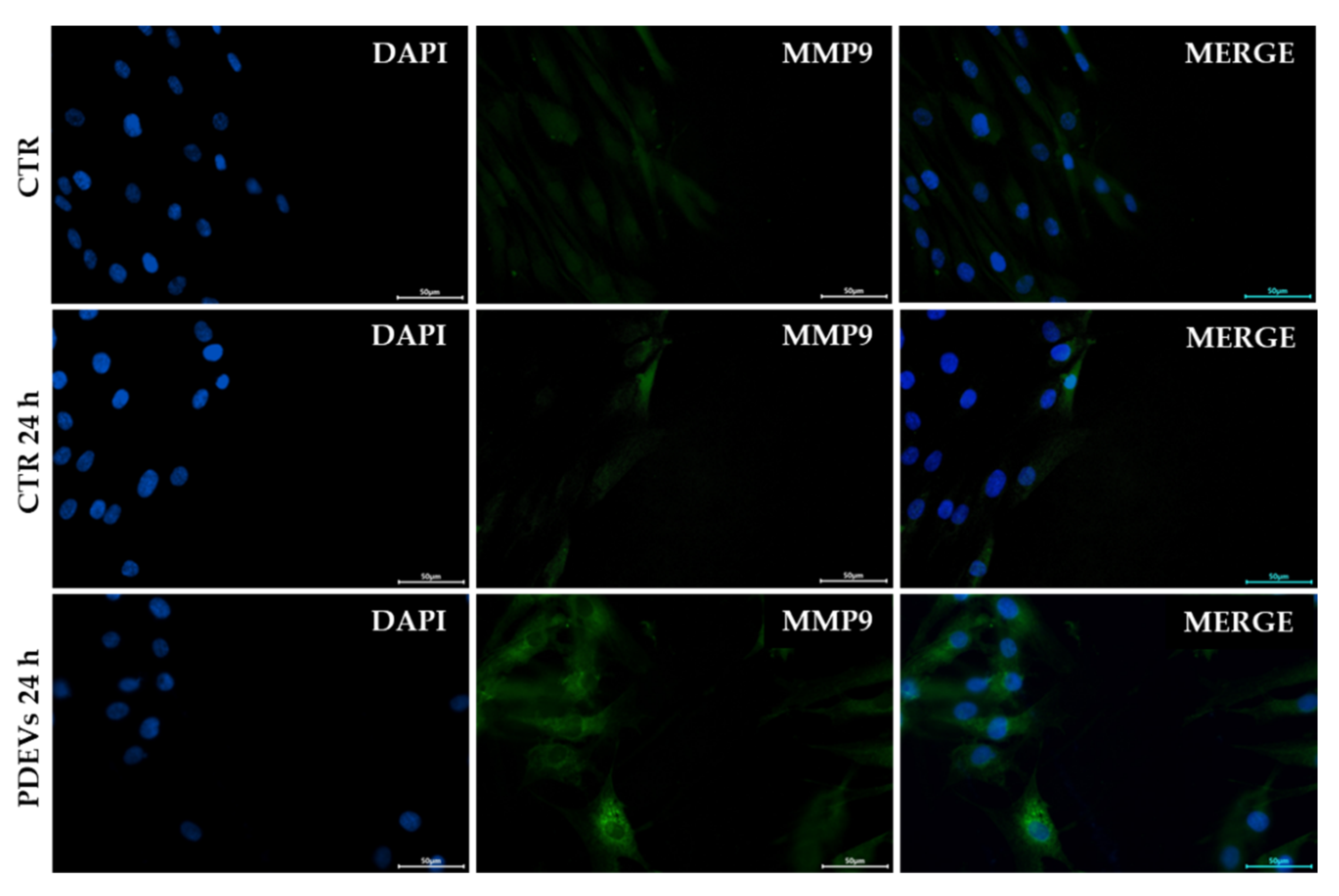

2.19. Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 evaluation

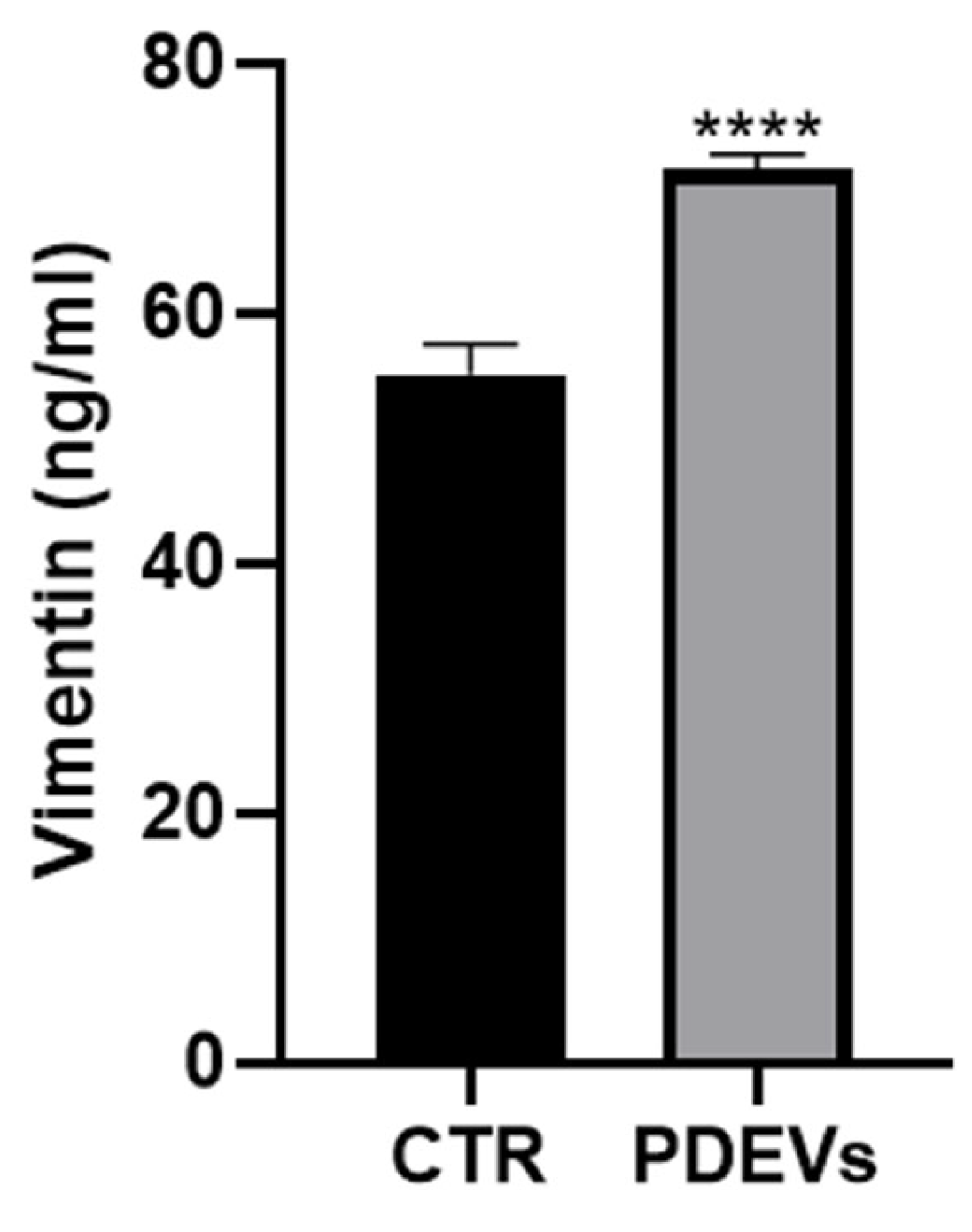

2.20. Vimentin quantification

2.21. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the PDEVs mix.

3.1.1. Bioactives’ content

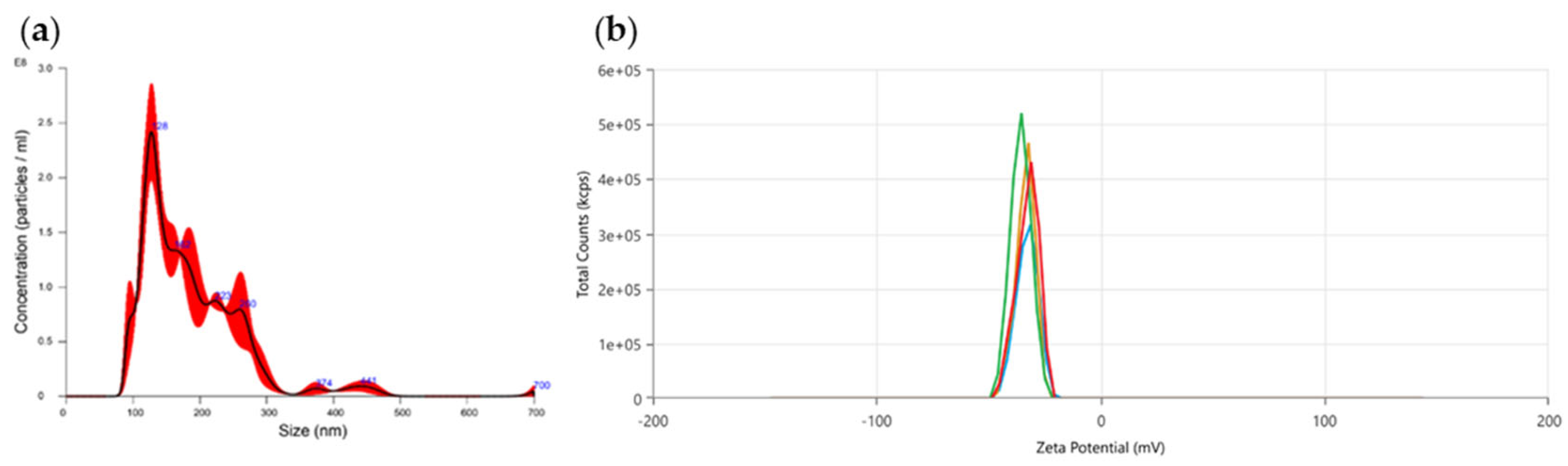

3.1.2. Size distribution and zeta potential analysis

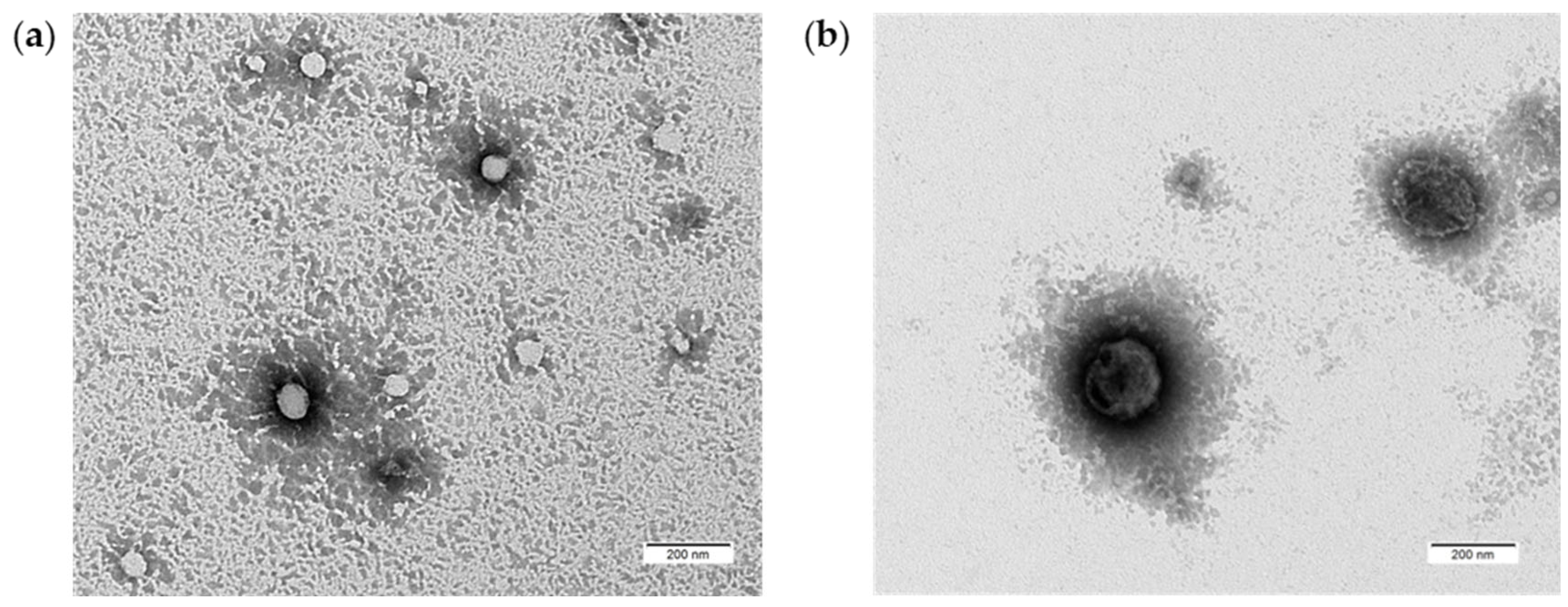

3.1.3. Morphological Characterization

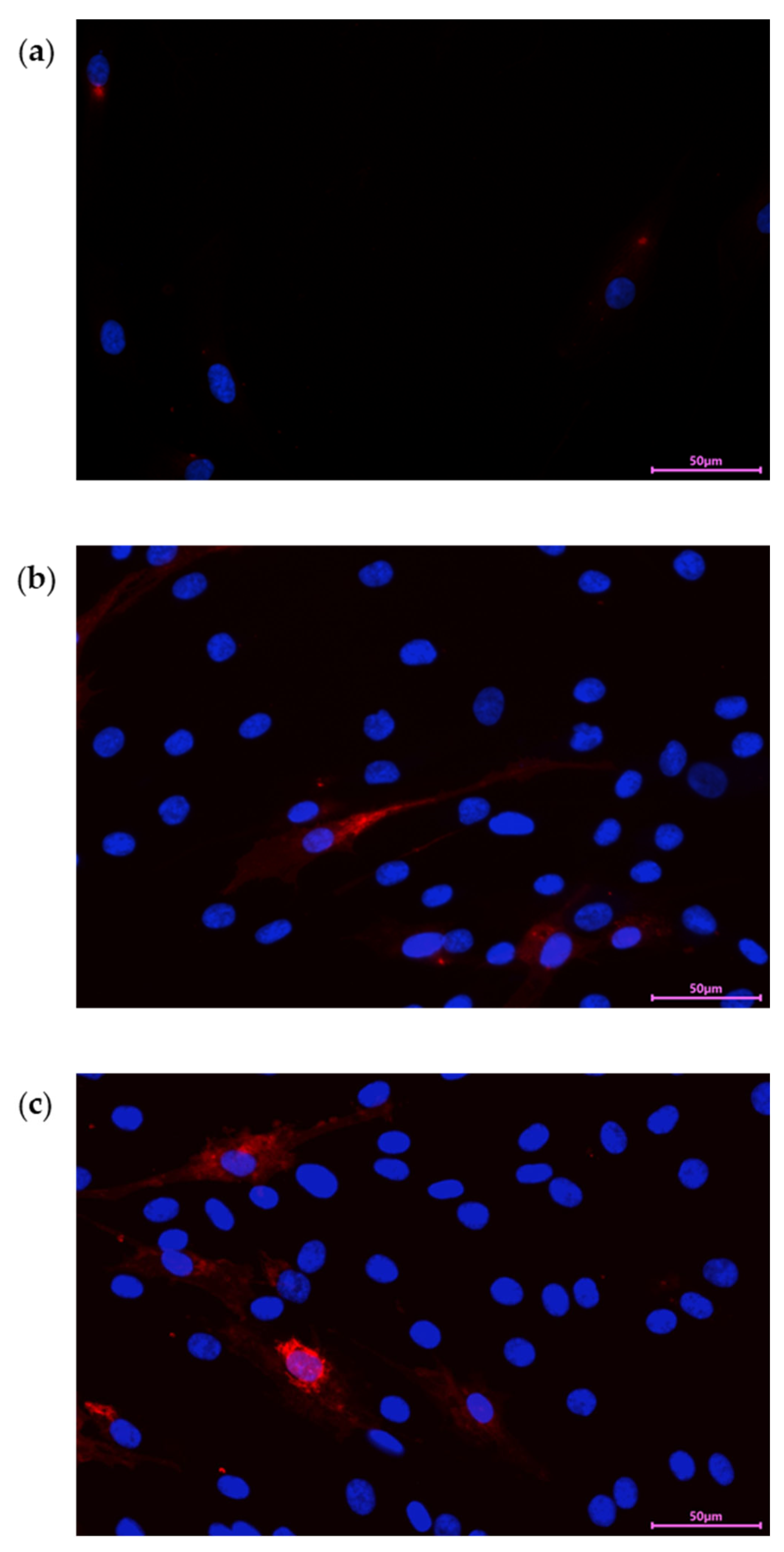

3.2. PDEVs uploading into Human Skin Fibroblasts

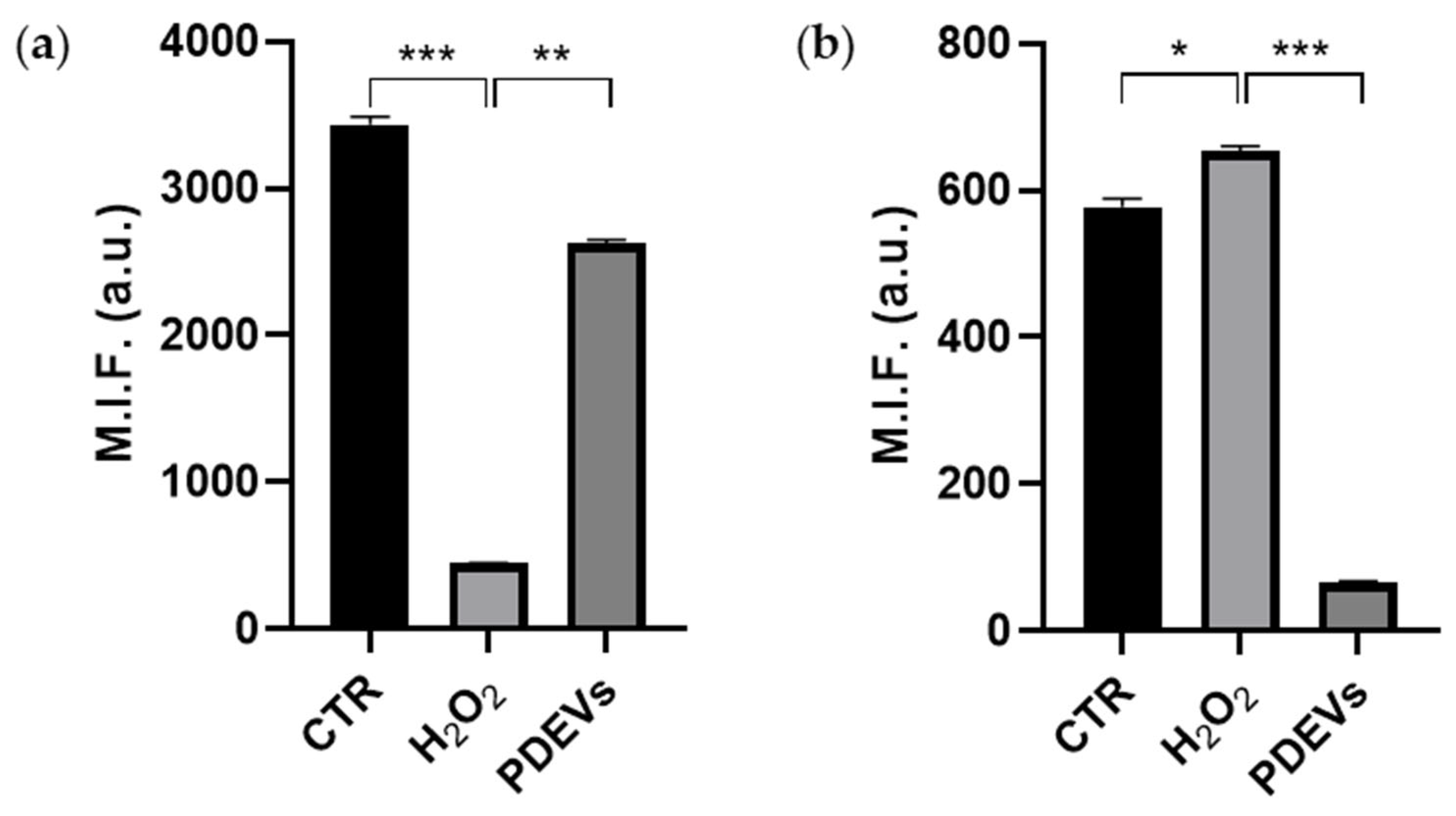

3.3. Effect on mitochondrial metabolism

3.4. Effects of the PDEVs’ mix on some aging-related molecules

3.5. Skin repair: Wound healing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abels, C.; Angelova-Fischer, I. Skin Care Products: Age-Appropriate Cosmetics. Curr Probl Dermatol 2018, 54, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Qiu, J. Oxidative Stress in the Skin: Impact and Related Protection. Intern J of Cosmetic Sci 2021, 43, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yosipovitch, G.; Misery, L.; Proksch, E.; Metz, M.; Ständer, S.; Schmelz, M. Skin Barrier Damage and Itch: Review of Mechanisms, Topical Management and Future Directions. Acta Derm Venereol 2019, 99, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilforoushzadeh, M.A.; Amirkhani, M.A.; Zarrintaj, P.; Salehi Moghaddam, A.; Mehrabi, T.; Alavi, S.; Mollapour Sisakht, M. Skin Care and Rejuvenation by Cosmeceutical Facial Mask. J of Cosmetic Dermatology 2018, 17, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, H.T.; Moon, J.-Y.; Lee, Y.-C. Natural Antioxidants from Plant Extracts in Skincare Cosmetics: Recent Applications, Challenges and Perspectives. Cosmetics 2021, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrest, B.A. Skin Aging and Photoaging: An Overview. J Am Acad Dermatol 1989, 21, 610–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, C.; Jiang, G. Research Progress on Skin Photoaging and Oxidative Stress. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 2021, 38, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaccio, F.; D’Arino, A.; Caputo, S.; Bellei, B. Focus on the Contribution of Oxidative Stress in Skin Aging. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, J.B.; Haigis, M.C. The Multifaceted Contributions of Mitochondria to Cellular Metabolism. Nat Cell Biol 2018, 20, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorova, L.D.; Popkov, V.A.; Plotnikov, E.Y.; Silachev, D.N.; Pevzner, I.B.; Jankauskas, S.S.; Babenko, V.A.; Zorov, S.D.; Balakireva, A.V.; Juhaszova, M.; et al. Mitochondrial Membrane Potential. Analytical Biochemistry 2018, 552, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, S.W.; Norman, J.P.; Barbieri, J.; Brown, E.B.; Gelbard, H.A. Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Probes and the Proton Gradient: A Practical Usage Guide. BioTechniques 2011, 50, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izyumov, D.S.; Avetisyan, A.V.; Pletjushkina, O.Y.; Sakharov, D.V.; Wirtz, K.W.; Chernyak, B.V.; Skulachev, V.P. “Wages of Fear”: Transient Threefold Decrease in Intracellular ATP Level Imposes Apoptosis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 2004, 1658, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkov, A.A.; Fiskum, G. Regulation of Brain Mitochondrial H 2 O 2 Production by Membrane Potential and NAD(P)H Redox State. Journal of Neurochemistry 2003, 86, 1101–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skulachev, V.P. Role of Uncoupled and Non-Coupled Oxidations in Maintenance of Safely Low Levels of Oxygen and Its One-Electron Reductants. Quart. Rev. Biophys. 1996, 29, 169–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirichen, H.; Yaigoub, H.; Xu, W.; Wu, C.; Li, R.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species and Their Contribution in Chronic Kidney Disease Progression Through Oxidative Stress. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 627837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadenas, E.; Davies, K.J.A. Mitochondrial Free Radical Generation, Oxidative Stress, and aging11This Article Is Dedicated to the Memory of Our Dear Friend, Colleague, and Mentor Lars Ernster (1920–1998), in Gratitude for All He Gave to Us. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2000, 29, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.D.; Affourtit, C.; Esteves, T.C.; Green, K.; Lambert, A.J.; Miwa, S.; Pakay, J.L.; Parker, N. Mitochondrial Superoxide: Production, Biological Effects, and Activation of Uncoupling Proteins. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2004, 37, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Williams, E.; Cadenas, E. Mitochondrial Respiratory Chain-Dependent Generation of Superoxide Anion and Its Release into the Intermembrane Space. Biochemical Journal 2001, 353, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazyluk, A.; Malyszko, J.; Hryszko, T.; Zbroch, E. State of the Art - Sirtuin 1 in Kidney Pathology - Clinical Relevance. Adv Med Sci 2019, 64, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielach-Bazyluk, A.; Zbroch, E.; Mysliwiec, H.; Rydzewska-Rosolowska, A.; Kakareko, K.; Flisiak, I.; Hryszko, T. Sirtuin 1 and Skin: Implications in Intrinsic and Extrinsic Aging-A Systematic Review. Cells 2021, 10, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerr, P.; Palumbo-Zerr, K.; Huang, J.; Tomcik, M.; Sumova, B.; Distler, O.; Schett, G.; Distler, J.H.W. Sirt1 Regulates Canonical TGF-β Signalling to Control Fibroblast Activation and Tissue Fibrosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016, 75, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michan, S.; Sinclair, D. Sirtuins in Mammals: Insights into Their Biological Function. Biochemical Journal 2007, 404, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarente, L. Sirtuins in Aging and Disease. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology 2007, 72, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, C.A.; Santos, M.A.; Araújo, G.R.; Lara, R.C.; Franco, F.N.; Chaves, M.M. Resveratrol: Change of SIRT 1 and AMPK Signaling Pattern during the Aging Process. Experimental Gerontology 2021, 146, 111226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, V.; Jun, M.; Jeong, W. Role of Resveratrol in Regulation of Cellular Defense Systems against Oxidative Stress. BioFactors 2018, 44, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, M.; Nikpayam, O.; Tavakoli-Rouzbehani, O.M.; Papi, S.; Amrollahi Bioky, A.; Ahmadiani, E.S.; Sohrab, G. A Comprehensive Insight into the Potential Effects of Resveratrol Supplementation on SIRT-1: A Systematic Review. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 2021, 15, 102224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iside, C.; Scafuro, M.; Nebbioso, A.; Altucci, L. SIRT1 Activation by Natural Phytochemicals: An Overview. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiciński, M.; Erdmann, J.; Nowacka, A.; Kuźmiński, O.; Michalak, K.; Janowski, K.; Ohla, J.; Biernaciak, A.; Szambelan, M.; Zabrzyński, J. Natural Phytochemicals as SIRT Activators—Focus on Potential Biochemical Mechanisms. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.K.; Chhabra, G.; Ndiaye, M.A.; Garcia-Peterson, L.M.; Mack, N.J.; Ahmad, N. The Role of Sirtuins in Antioxidant and Redox Signaling. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2018, 28, 643–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Azzini, E.; Zucca, P.; Maria Varoni, E.; Anil Kumar, N.V.; Dini, L.; Panzarini, E.; Rajkovic, J.; Valere Tsouh Fokou, P.; Peluso, I.; et al. Plant-Derived Bioactives and Oxidative Stress-Related Disorders: A Key Trend towards Healthy Aging and Longevity Promotion. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C.; Nigam, Y. Naturally Derived Factors and Their Role in the Promotion of Angiogenesis for the Healing of Chronic Wounds. Angiogenesis 2013, 16, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Lin, Q.; Liang, Y. Plant-Derived Antioxidants Protect the Nervous System From Aging by Inhibiting Oxidative Stress. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roleira, F.M.F.; Tavares-da-Silva, E.J.; Varela, C.L.; Costa, S.C.; Silva, T.; Garrido, J.; Borges, F. Plant Derived and Dietary Phenolic Antioxidants: Anticancer Properties. Food Chem 2015, 183, 235–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Raimo, R.; Mizzoni, D.; Spada, M.; Dolo, V.; Fais, S.; Logozzi, M. Oral Treatment with Plant-Derived Exosomes Restores Redox Balance in H2O2-Treated Mice. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logozzi, M.; Di Raimo, R.; Mizzoni, D.; Fais, S. Nanovesicles from Organic Agriculture-Derived Fruits and Vegetables: Characterization and Functional Antioxidant Content. IJMS 2021, 22, 8170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logozzi, M.; Di Raimo, R.; Mizzoni, D.; Fais, S. Anti-Aging and Anti-Tumor Effect of FPP® Supplementation. Eur J Transl Myol 2020, 30, 8905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logozzi, M.; Mizzoni, D.; Di Raimo, R.; Macchia, D.; Spada, M.; Fais, S. Oral Administration of Fermented Papaya (FPP®) Controls the Growth of a Murine Melanoma through the In Vivo Induction of a Natural Antioxidant Response. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Wan, F.; Su, W.; Xie, W. Research Progress on Skin Aging and Active Ingredients. Molecules 2023, 28, 5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-M.; Cheng, M.-Y.; Xun, M.-H.; Zhao, Z.-W.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, W.; Cheng, J.; Ni, J.; Wang, W. Possible Mechanisms of Oxidative Stress-Induced Skin Cellular Senescence, Inflammation, and Cancer and the Therapeutic Potential of Plant Polyphenols. IJMS 2023, 24, 3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addis, R.; Cruciani, S.; Santaniello, S.; Bellu, E.; Sarais, G.; Ventura, C.; Maioli, M.; Pintore, G. Fibroblast Proliferation and Migration in Wound Healing by Phytochemicals: Evidence for a Novel Synergic Outcome. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 17, 1030–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdai, F.; Risaliti, C.; Monici, M. Role of Fibroblasts in Wound Healing and Tissue Remodeling on Earth and in Space. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10, 958381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoedler, S.; Broichhausen, S.; Guo, R.; Dai, R.; Knoedler, L.; Kauke-Navarro, M.; Diatta, F.; Pomahac, B.; Machens, H.-G.; Jiang, D.; et al. Fibroblasts – the Cellular Choreographers of Wound Healing. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1233800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel, J.A.; Gawronska-Kozak, B. Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) Is Upregulated during Scarless Wound Healing in Athymic Nude Mice. Matrix Biology 2006, 25, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caley, M.P.; Martins, V.L.C.; O’Toole, E.A. Metalloproteinases and Wound Healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2015, 4, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auf Dem Keller, U.; Sabino, F. Matrix Metalloproteinases in Impaired Wound Healing. MNM 2015, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandhwal, M.; Behl, T.; Singh, S.; Sharma, N.; Arora, S.; Bhatia, S.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Sachdeva, M.; Bungau, S. Role of Matrix Metalloproteinase in Wound Healing. Am J Transl Res 2022, 14, 4391–4405. [Google Scholar]

- Ivaska, J.; Pallari, H.-M.; Nevo, J.; Eriksson, J.E. Novel Functions of Vimentin in Cell Adhesion, Migration, and Signaling. Experimental Cell Research 2007, 313, 2050–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, M.G.; Kojima, S.-I.; Goldman, R.D. Vimentin Induces Changes in Cell Shape, Motility, and Adhesion during the Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition. FASEB J 2010, 24, 1838–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, J.M.; Bayless, K.J. Vimentin as an Integral Regulator of Cell Adhesion and Endothelial Sprouting. Microcirculation 2014, 21, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliogeryte, K.; Gavara, N. Vimentin Plays a Crucial Role in Fibroblast Ageing by Regulating Biophysical Properties and Cell Migration. Cells 2019, 8, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, W.; Bai, M.; Luo, Q.; Zheng, Q.; Xu, Y.; Li, X.; Jiang, C.; Cho, W.C.; Fan, Z. Edible Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Serve as Promising Therapeutic Systems. Nano TransMed 2023, 2, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, F.; Koçak, P.; Güneş, M.Y.; Özkan, İ.; Yıldırım, E.; Kala, E.Y. In Vitro Wound Healing Activity of Wheat-Derived Nanovesicles. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2019, 188, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savcı, Y.; Kırbaş, O.K.; Bozkurt, B.T.; Abdik, E.A.; Taşlı, P.N.; Şahin, F.; Abdik, H. Grapefruit-Derived Extracellular Vesicles as a Promising Cell-Free Therapeutic Tool for Wound Healing. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 5144–5156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunaway, S.; Odin, R.; Zhou, L.; Ji, L.; Zhang, Y.; Kadekaro, A.L. Natural Antioxidants: Multiple Mechanisms to Protect Skin From Solar Radiation. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguly, B.; Hota, M.; Pradhan, J. Skin Aging: Implications of UV Radiation, Reactive Oxygen Species and Natural Antioxidants. In Biochemistry; Ahmad, R., Ed.; IntechOpen, 2022; Vol. 28 ISBN 978-1-83968-281-0.

- Michalak, M. Plant-Derived Antioxidants: Significance in Skin Health and the Ageing Process. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varani, J.; Warner, R.L.; Gharaee-Kermani, M.; Phan, S.H.; Kang, S.; Chung, J.; Wang, Z.; Datta, S.C.; Fisher, G.J.; Voorhees, J.J. Vitamin A Antagonizes Decreased Cell Growth and Elevated Collagen-Degrading Matrix Metalloproteinases and Stimulates Collagen Accumulation in Naturally Aged Human Skin1. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2000, 114, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, Y.C. Ascorbic Acid (Vitamin C) as a Cosmeceutical to Increase Dermal Collagen for Skin Antiaging Purposes: Emerging Combination Therapies. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullar, J.; Carr, A.; Vissers, M. The Roles of Vitamin C in Skin Health. Nutrients 2017, 9, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilasoniya, A.; Garaeva, L.; Shtam, T.; Spitsyna, A.; Putevich, E.; Moreno-Chamba, B.; Salazar-Bermeo, J.; Komarova, E.; Malek, A.; Valero, M.; et al. Potential of Plant Exosome Vesicles from Grapefruit (Citrus × Paradisi) and Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum) Juices as Functional Ingredients and Targeted Drug Delivery Vehicles. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemidkanam, V.; Chaichanawongsaroj, N. Characterizing Kaempferia Parviflora Extracellular Vesicles, a Nanomedicine Candidate. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, S.; Koo, Y.; Yang, A.; Dai, Y.; Khant, H.; Osman, S.R.; Chowdhury, M.; Wei, H.; Li, Y.; et al. Characterization of and Isolation Methods for Plant Leaf Nanovesicles and Small Extracellular Vesicles. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine 2020, 29, 102271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, S.P.; Paolini, A.; D’Oria, V.; Sarra, A.; Sennato, S.; Bordi, F.; Masotti, A. Extracellular Vesicles Derived From Citrus Sinensis Modulate Inflammatory Genes and Tight Junctions in a Human Model of Intestinal Epithelium. Front Nutr 2021, 8, 778998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rikkert, L.G.; Nieuwland, R.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M.; Coumans, F. a. W. Quality of Extracellular Vesicle Images by Transmission Electron Microscopy Is Operator and Protocol Dependent. J Extracell Vesicles 2019, 8, 1555419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, C.; Xiang, H.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, Q.; Huang, F.; Mao, L. A Review of Labeling Approaches Used in Small Extracellular Vesicles Tracing and Imaging. Int J Nanomedicine 2023, 18, 4567–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikiforova, N.; Chumachenko, M.; Nazarova, I.; Zabegina, L.; Slyusarenko, M.; Sidina, E.; Malek, A. CM-Dil Staining and SEC of Plasma as an Approach to Increase Sensitivity of Extracellular Nanovesicles Quantification by Bead-Assisted Flow Cytometry. Membranes (Basel) 2021, 11, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viveiros, A.; Kadam, V.; Monyror, J.; Morales, L.C.; Pink, D.; Rieger, A.M.; Sipione, S.; Posse De Chaves, E. In-Cell Labeling Coupled to Direct Analysis of Extracellular Vesicles in the Conditioned Medium to Study Extracellular Vesicles Secretion with Minimum Sample Processing and Particle Loss. Cells 2022, 11, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.Y.; Kang, M.; Hisey, C.L.; Chamley, L.W. Studying Exogenous Extracellular Vesicle Biodistribution by in Vivo Fluorescence Microscopy. Dis Model Mech 2023, 16, dmm050074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhdanova, D.Y.; Poltavtseva, R.A.; Svirshchevskaya, E.V.; Bobkova, N.V. Effect of Intranasal Administration of Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Exosomes on Memory of Mice in Alzheimer’s Disease Model. Bull Exp Biol Med 2021, 170, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimaletdinov, A.M.; Gomzikova, M.O. Tracking of Extracellular Vesicles’ Biodistribution: New Methods and Approaches. IJMS 2022, 23, 11312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, H.J.; Kim, K.B.; An, I.-S.; Ahn, K.J.; Han, H.J. Protective Effects of Rosmarinic Acid against Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Cellular Senescence and the Inflammatory Response in Normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts. Molecular Medicine Reports 2017, 16, 9763–9769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, H.; Man, M.; Hu, L. Aging in the Dermis: Fibroblast Senescence and Its Significance. Aging Cell 2023, e14054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Mobashery, S.; Chang, M. Roles of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Cutaneous Wound Healing. In Wound Healing - New insights into Ancient Challenges; Alexandrescu, V.A., Ed.; InTech, 2016 ISBN 978-953-51-2678-2.

- P., B. Wound Healing and the Role of Fibroblasts. J Wound Care 2013, 22, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yan, L.; Du, W.; Zhang, M.; Chen, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, G.; Li, J.; Dong, Y.; et al. MMP-2 and MMP-9 Contribute to the Angiogenic Effect Produced by Hypoxia/15-HETE in Pulmonary Endothelial Cells. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 2018, 121, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legrand, C.; Gilles, C.; Zahm, J.M.; Polette, M.; Buisson, A.C.; Kaplan, H.; Birembaut, P.; Tournier, J.M. Airway Epithelial Cell Migration Dynamics. MMP-9 Role in Cell-Extracellular Matrix Remodeling. J Cell Biol 1999, 146, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menko, A.S.; Bleaken, B.M.; Libowitz, A.A.; Zhang, L.; Stepp, M.A.; Walker, J.L. A Central Role for Vimentin in Regulating Repair Function during Healing of the Lens Epithelium. Mol Biol Cell 2014, 25, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieminen, M.; Henttinen, T.; Merinen, M.; Marttila-Ichihara, F.; Eriksson, J.E.; Jalkanen, S. Vimentin Function in Lymphocyte Adhesion and Transcellular Migration. Nat Cell Biol 2006, 8, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci-Guyon, E.; Portier, M.M.; Dunia, I.; Paulin, D.; Pournin, S.; Babinet, C. Mice Lacking Vimentin Develop and Reproduce without an Obvious Phenotype. Cell 1994, 79, 679–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Jang, H.; Kim, W.; Kim, D.; Park, J.H. Therapeutic Applications of Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles as Antioxidants for Oxidative Stress-Related Diseases. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.H.; Hong, Y.D.; Kim, D.; Park, S.J.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, H.-M.; Yoon, E.J.; Cho, J.-S. Confirmation of Plant-Derived Exosomes as Bioactive Substances for Skin Application through Comparative Analysis of Keratinocyte Transcriptome. Appl Biol Chem 2022, 65, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafan, M.; Malinowska, M.A.; Ekiert, H.; Kwaśniak, B.; Sikora, E.; Szopa, A. Vitis Vinifera (Vine Grape) as a Valuable Cosmetic Raw Material. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apraj, V.D.; Pandita, N.S. Evaluation of Skin Anti-Aging Potential of Citrus Reticulata Blanco Peel. Pharmacognosy Res 2016, 8, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.-D.; Lu, Y.-N.; Liu, Q.; Shi, X.-M.; Tian, J. Modulation of TRPV1 Function by Citrus Reticulata (Tangerine) Fruit Extract for the Treatment of Sensitive Skin. J Cosmet Dermatol 2023, 22, 1369–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.S.; Silva, A.M.; Nunes, F.M. Citrus Reticulata Blanco Peels as a Source of Antioxidant and Anti-Proliferative Phenolic Compounds. Industrial Crops and Products 2018, 111, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.R.; Jong, Y.X.; Balakrishnan, M.; Bok, Z.K.; Weng, J.K.K.; Tay, K.C.; Goh, B.H.; Ong, Y.S.; Chan, K.G.; Lee, L.H.; et al. Beneficial Role of Carica Papaya Extracts and Phytochemicals on Oxidative Stress and Related Diseases: A Mini Review. Biology (Basel) 2021, 10, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattanapitayakul, S.K.; Jarisarapurin, W.; Kunchana, K.; Setthawong, V.; Chularojmontri, L. Unripe Carica Papaya Fresh Fruit Extract Protects against Methylglyoxal-Mediated Aging in Human Dermal Skin Fibroblasts. Prev Nutr Food Sci 2023, 28, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.H.; Lim, C.Y.; Jung, J.I.; Kim, T.Y.; Kim, E.J. Protective Effects of Red Orange ( Citrus Sinensis [L.] Osbeck [Rutaceae]) Extract against UVA-B Radiation-Induced Photoaging in Skh:HR-2 Mice. Nutr Res Pract 2023, 17, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobile, V.; Burioli, A.; Yu, S.; Zhifeng, S.; Cestone, E.; Insolia, V.; Zaccaria, V.; Malfa, G.A. Photoprotective and Antiaging Effects of a Standardized Red Orange (Citrus Sinensis (L.) Osbeck) Extract in Asian and Caucasian Subjects: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrijevic, J.; Tomovic, M.; Bradic, J.; Petrovic, A.; Jakovljevic, V.; Andjic, M.; Živković, J.; Milošević, S.Đ.; Simanic, I.; Dragicevic, N. Punica Granatum L. (Pomegranate) Extracts and Their Effects on Healthy and Diseased Skin. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbarnejad, F. Dermatology Benefits of Punica Granatum: A Review of the Potential Benefits of Punica Granatum in Skin Disorders. Asain J. Green Chem. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, M.; Gabrielli, M.; Adinolfi, E.; Verderio, C. Role of ATP in Extracellular Vesicle Biogenesis and Dynamics. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 654023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedhar, A.; Aguilera-Aguirre, L.; Singh, K.K. Mitochondria in Skin Health, Aging, and Disease. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, B.; Essick, E.; Ehringer, W.; Murphree, S.; Hauck, M.A.; Li, M.; Chien, S. Enhancing Skin Wound Healing by Direct Delivery of Intracellular Adenosine Triphosphate. Am J Surg 2007, 193, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wan, R.; Mo, Y.; Li, M.; Tseng, M.T.; Chien, S. Intracellular Adenosine Triphosphate Delivery Enhanced Skin Wound Healing in Rabbits. Ann Plast Surg 2009, 62, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akuma, P.; Okagu, O.D.; Udenigwe, C.C. Naturally Occurring Exosome Vesicles as Potential Delivery Vehicle for Bioactive Compounds. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comino-Sanz, I.M.; López-Franco, M.D.; Castro, B.; Pancorbo-Hidalgo, P.L. The Role of Antioxidants on Wound Healing: A Review of the Current Evidence. JCM 2021, 10, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Q.; Thakur, A.; Liu, W.; Yan, Y. Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles (PDEVs) in Nanomedicine for Human Disease and Therapeutic Modalities. J Nanobiotechnology 2023, 21, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Cai, Q.; Qiao, L.; Huang, C.-Y.; Wang, S.; Miao, W.; Ha, T.; Wang, Y.; Jin, H. RNA-Binding Proteins Contribute to Small RNA Loading in Plant Extracellular Vesicles. Nat Plants 2021, 7, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-López, C.M.; Manzaneque-López, M.C.; Pérez-Bermúdez, P.; Soler, C.; Marcilla, A. Characterization and Bioactivity of Extracellular Vesicles Isolated from Pomegranate. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 12870–12882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Park, J.H. Isolation of Aloe Saponaria-Derived Extracellular Vesicles and Investigation of Their Potential for Chronic Wound Healing. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Choi, Y.C.; Cho, S.H.; Choi, J.S.; Cho, Y.W. The Antioxidant Effect of Small Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Aloe Vera Peels for Wound Healing. Tissue Eng Regen Med 2021, 18, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bioactive compound | Concentration |

| Total Antioxidant Capacity | 2,3 ± 0,2 nMol/µL |

| Ascorbic Acid | 1910 ± 1 ng |

| ATP | 61,3 ± 16,6 mM |

| Catalase | 499,1 ± 2,2 mU/ml |

| Citric Acid | 37,67 ± 1,34 µmol/L |

| Glutathione | 11,8 ± 0,3 µM |

| SOD | 7392,00 ± 6,03 U/ml |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).