Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

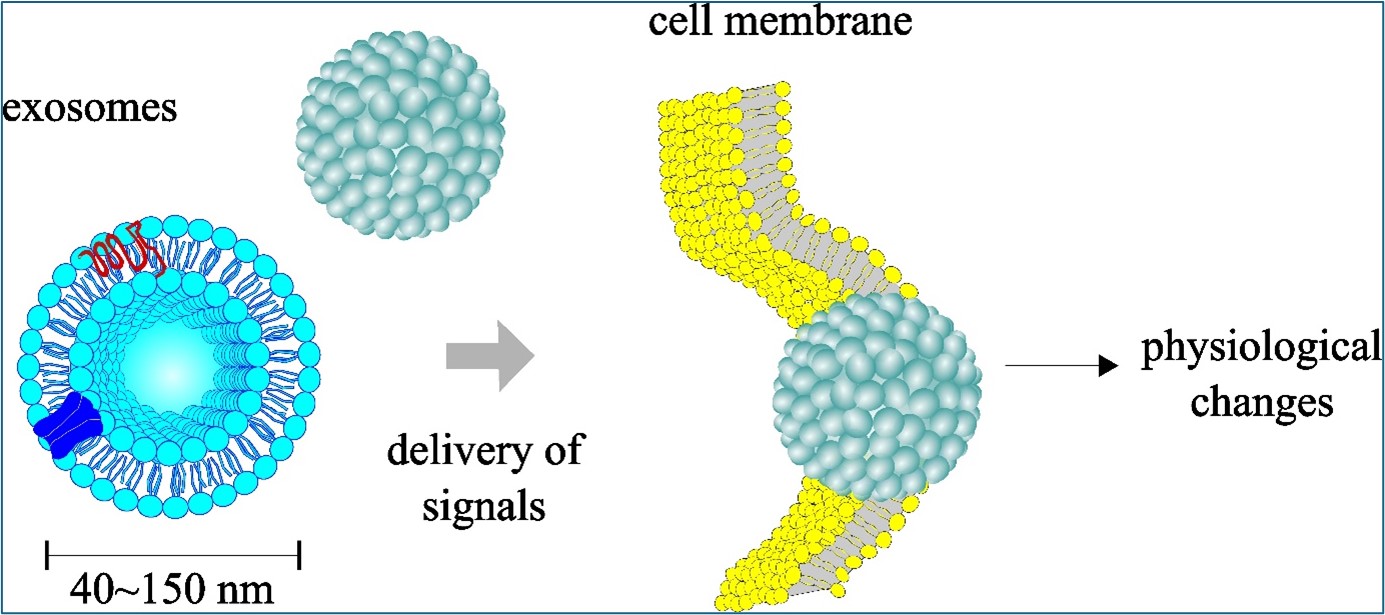

1. Introduction

2. Results

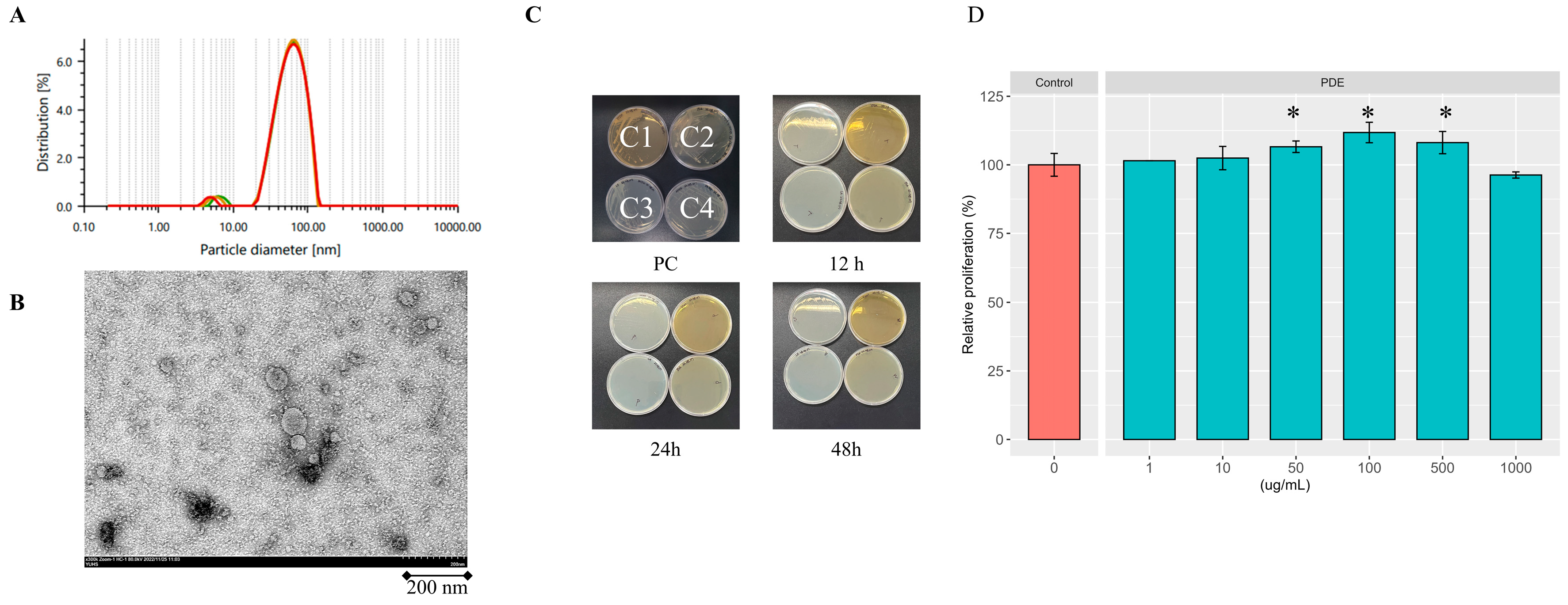

2.1. Profile of Isolated SDEs

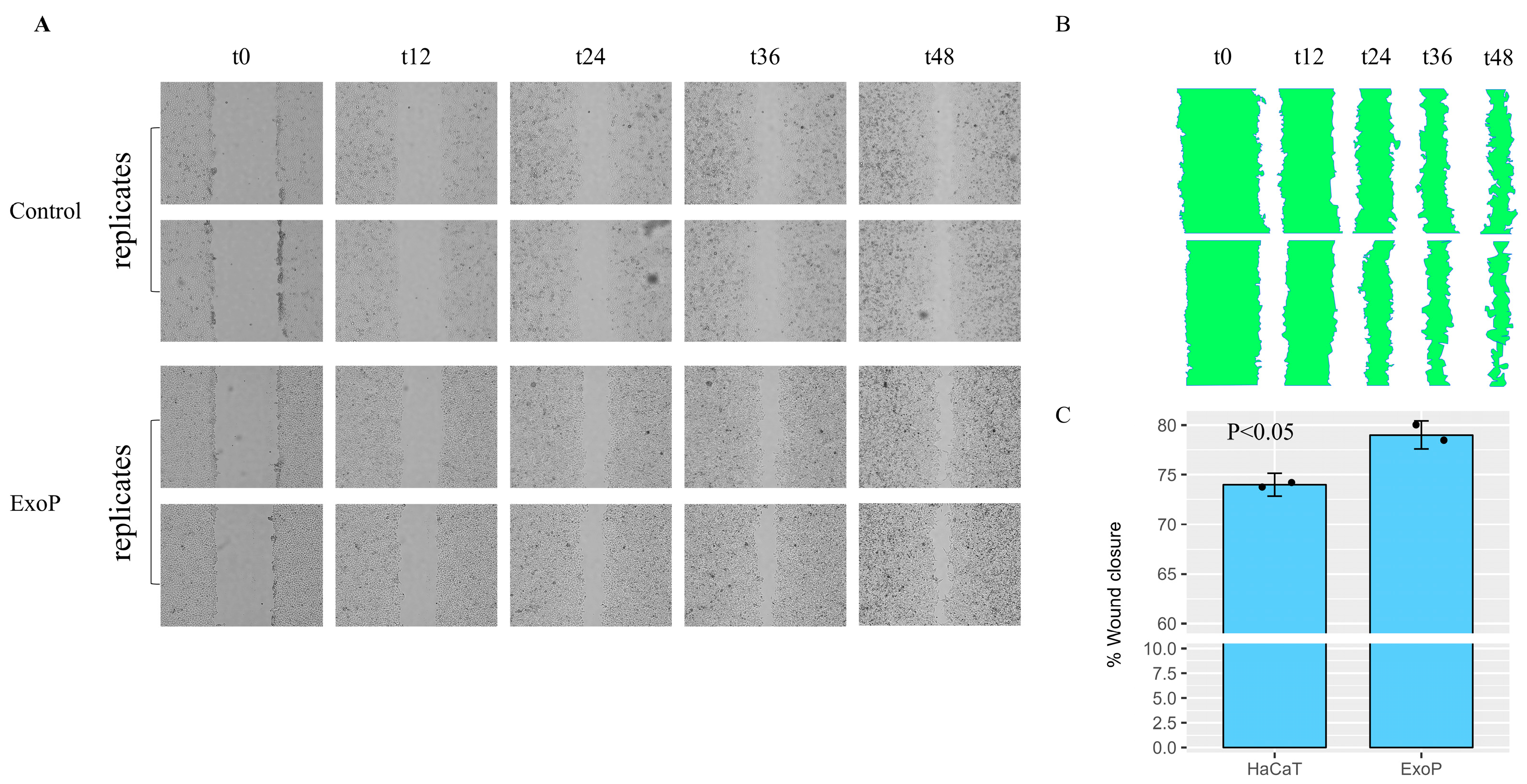

2.2. Impact of SDEs on HaCaT Keratinocyte Wound Healing

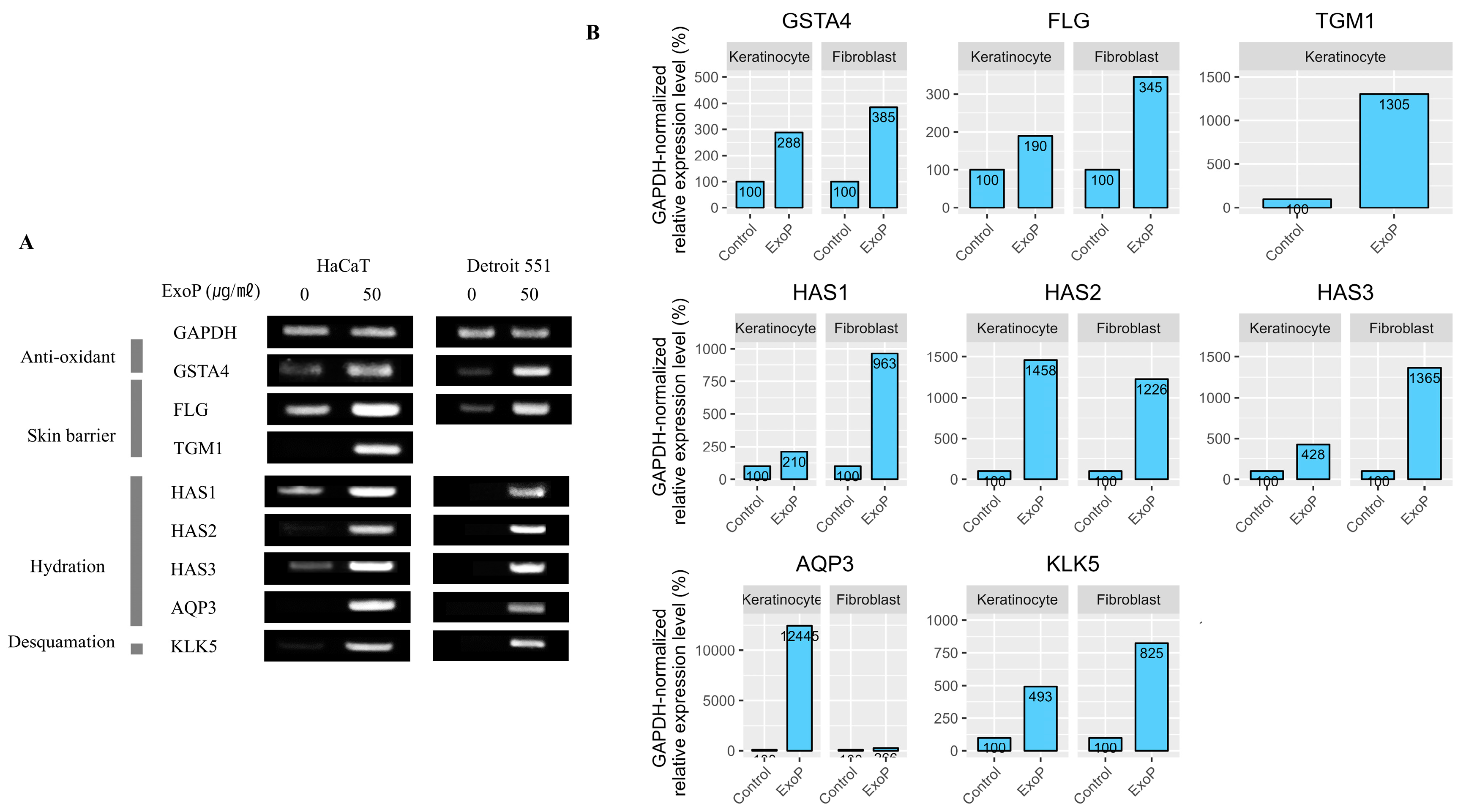

2.3. Impact of SDEs on the Expression of Genes Associated with the Skin Barrier

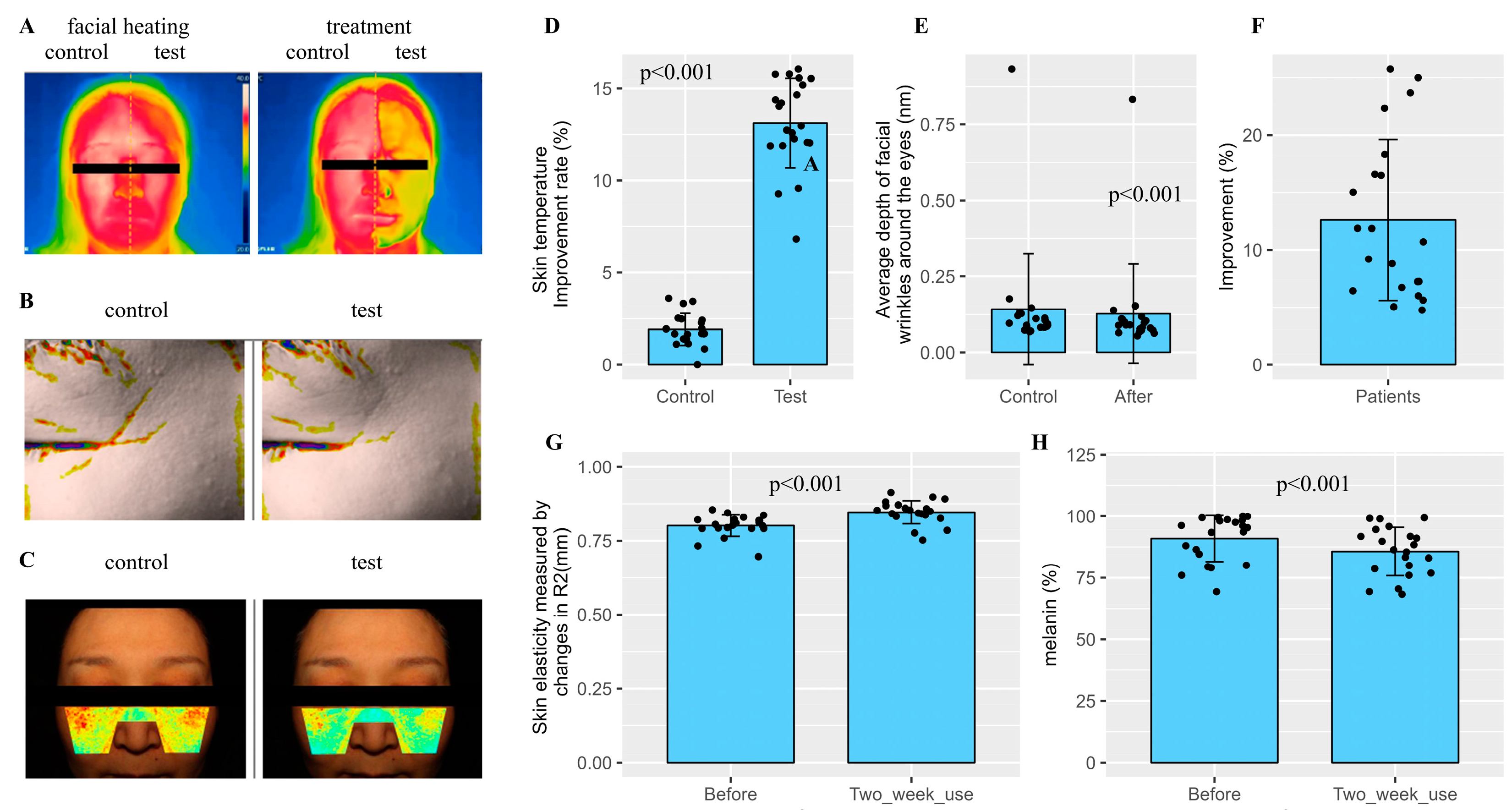

2.4. Clinical Skin Assessment with Prototype Cosmetics Featuring SDEs as the Primary Component

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

4.2. Preparation and Characterization of SDEs

4.3. Cell Culture and SDE Administration

4.4. Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

4.5. Wound Healing Evaluations

4.6. Dermatological Clinical Assessment

Author Contributions

Funding

Declaration of Competing Interest

References

- Kim, D.J.; Iwasaki, A.; Chien, A.L.; Kang, S. UVB-Mediated DNA Damage Induces Matrix Metalloproteinases to Promote Photoaging in an AhR- and SP1-Dependent Manner. JCI Insight 2022, 7(9):e156344. [CrossRef]

- Brenneisen, P.; Sies, H.; Scharffetter-Kochanek, K. Ultraviolet-B Irradiation and Matrix Metalloproteinases: From Induction via Signaling to Initial Events. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2002, 973:31-43.

- Candi, E.; Schmidt, R.; Melino, G. The Cornified Envelope: A Model of Cell Death in the Skin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2005, 6(4):328-340. [CrossRef]

- Montero-Vilchez, T.; Segura-Fernández-nogueras, M.V.; Pérez-Rodríguez, I.; Soler-Gongora, M.; Martinez-Lopez, A.; Fernández-González, A.; Molina-Leyva, A.; Arias-Santiago, S. Skin Barrier Function in Psoriasis and Atopic Dermatitis: Transepidermal Water Loss and Temperature as Useful Tools to Assess Disease Severity. J Clin Med 2021, 10(2):359. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.E.; Howell, M.D.; Guttman, E.; Gilleaudeau, P.M.; Cardinale, I.R.; Boguniewicz, M.; Krueger, J.G.; Leung, D.Y.M. TNF-α Downregulates Filaggrin and Loricrin through c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase: Role for TNF-α Antagonists to Improve Skin Barrier. J Invest Dermatol. 2011, 131(6):1272-1279. [CrossRef]

- Wikramanayake, T.C.; Stojadinovic, O.; Tomic-Canic, M. Epidermal Differentiation in Barrier Maintenance and Wound Healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2014, 3(3):272-280. [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, R.G.; Unverdorben, M. Wound Cleaning and Wound Healing: A Concise Review. Adv Skin Wound Care 2013, 26(4):160-163.

- Rezaie, J.; Feghhi, M.; Etemadi, T. A Review on Exosomes Application in Clinical Trials: Perspective, Questions, and Challenges. Cell Commun Signal. 2022, 20(1):145. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Erviti, L.; Seow, Y.; Yin, H.; Betts, C.; Lakhal, S.; Wood, M.J.A. Delivery of SiRNA to the Mouse Brain by Systemic Injection of Targeted Exosomes. Nat Biotechnol 2011, 29(4):341-345. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, J.; Stewart, T.; Sheng, L.; Li, N.; Bullock, K.; Song, N.; Shi, M.; Banks, W.A.; Zhang, J. Transmission of α-Synuclein-Containing Erythrocyte-Derived Extracellular Vesicles across the Blood-Brain Barrier via Adsorptive Mediated Transcytosis: Another Mechanism for Initiation and Progression of Parkinson’s Disease? Acta Neuropathol Commun 2017, 5(1):71.

- Banks, W.A.; Sharma, P.; Bullock, K.M.; Hansen, K.M.; Ludwig, N.; Whiteside, T.L. Transport of Extracellular Vesicles across the Blood-Brain Barrier: Brain Pharmacokinetics and Effects of Inflammation. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21(12):4407. [CrossRef]

- Tenchov, R.; Sasso, J.M.; Wang, X.; Liaw, W.S.; Chen, C.A.; Zhou, Q.A. Exosomes Nature’s Lipid Nanoparticles, a Rising Star in Drug Delivery and Diagnostics. ACS Nano 2022, 16(11):17802-17846. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Huang, H.; Tang, S.; Chai, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, M.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Yang C. Recent Advances in Exosome-Mediated Nucleic Acid Delivery for Cancer Therapy. J Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20(1):279. [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Zhuang, X.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, H.; Deng, Z. Bin; Wang, B.; Zhang, L.; Kakar, S.; Jun, Y.; Miller, D.; et al. Interspecies Communication between Plant and Mouse Gut Host Cells through Edible Plant Derived Exosome-like Nanoparticles. Mol Nutr Food Res 2014, 58(7):1561-1573. [CrossRef]

- Dad, H.A.; Gu, T.W.; Zhu, A.Q.; Huang, L.Q.; Peng, L.H. Plant Exosome-like Nanovesicles: Emerging Therapeutics and Drug Delivery Nanoplatforms. Mol Ther 2021, 29(1):13-31. [CrossRef]

- Yi, Q.; Xu, Z.; Thakur, A.; Zhang, K.; Liang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Yan, Y. Current Understanding of Plant-Derived Exosome-like Nanoparticles in Regulating the Inflammatory Response and Immune System Microenvironment. Pharmacol Res 2023, 190:106733. [CrossRef]

- Arif, S.; Larochelle, S.; Trudel, B.; Gounou, C.; Bordeleau, F.; Brisson, A.R.; Moulin, V.J. The Diffusion of Normal Skin Wound Myofibroblast-derived Microvesicles Differs According to Matrix Composition. J Extracell Biol 2023, 3(1):e131. [CrossRef]

- Faria-Silva, C.; Ascenso, A.; Costa, A.M.; Marto, J.; Carvalheiro, M.; Ribeiro, H.M.; Simões, S. Feeding the Skin: A New Trend in Food and Cosmetics Convergence. Trends Food Sci Technol 2020, 95, 21–32. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Jeong, D.-Y.; Jeun, Y.C.; Choe, H.; Yang, S. Preventive and Ameliorative Effects of Potato Exosomes on UVB-induced Photodamage in Keratinocyte HaCaT Cells. Mol Med Rep 2023, 28(3):167. [CrossRef]

- Ashcroft, G.S.; Jeong, M.J.; Ashworth, J.J.; Hardman, M.; Jin, W.; Moutsopoulos, N.; Wild, T.; McCartney-Francis, N.; Sim, D.; McGrady, G.; et al. Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha (TNF-α) Is a Therapeutic Target for Impaired Cutaneous Wound Healing. Wound Repair Regen 2012, 20(1):38-49.

- Bhat, B.B.; Kamath, P.P.; Chatterjee, S.; Bhattacherjee, R.; Nayak, U.Y. Recent Updates on Nanocosmeceutical Skin Care and Anti-Aging Products. Curr Pharm Des 2022, 28(15):1258-1271. [CrossRef]

- Verbavatz, J.M.; Boury-Jamot, M.; Daraspe, J.; Bonté, F.; Perrier, E.; Schnebert, S.; Dumas, M. Skin Aquaporins: Function in Hydration, Wound Healing, and Skin Epidermis Homeostasis. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2009, 190, 205–217.

- Bollag, W.B.; Aitkens, L.; White, J.; Hyndman, K.A. Aquaporin-3 in the Epidermis: More than Skin Deep. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2020, 18(6):C1144-C1153. [CrossRef]

- Drislane C,; Irvine AD. The Role of Filaggrin in Atopic Dermatitis and Allergic Disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020, 124(1):36-43. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.M.; Ahn, K.S.; Cho, M.O.; Yoneda, K.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, E.S.; Candi, E.; Melino, G.; Ahvazi, B.; et al. Novel Mutations of the Transglutaminase 1 Gene in Lamellar Ichthyosis. J Invest Dermatol 2001, 117(2):214-218. [CrossRef]

- Caubet, C.; Jonca, N.; Brattsand, M.; Guerrin, M.; Bernard, D.; Schmidt, R.; Egelrud, T.; Simon, M.; Serre, G. Degradation of Corneodesmosome Proteins by Two Serine Proteases of the Kallikrein Family, SCTE/KLK5/HK5 and SCCE/KLK7/HK7. J Invest Dermatol. 2004, 122(5):1235-1244. [CrossRef]

- Milstone, L.M. Epidermal Desquamation. J Dermatol Sci 2004, 36(3):131-140. [CrossRef]

- Nauroy, P.; Nyström A. Kallikreins: Essential Epidermal Messengers for Regulation of the Skin Microenvironment during Homeostasis, Repair and Disease. Matrix Biol Plus 2019 21;6-7:100019. [CrossRef]

- Göllner, I.; Voss, W.; von Hehn, U.; Kammerer, S. Ingestion of an Oral Hyaluronan Solution Improves Skin Hydration, Wrinkle Reduction, Elasticity, and Skin Roughness: Results of a Clinical Study. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med 2017, 22. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guo, H.; Lei, C.; Liu, L.; Xu, L.; Feng, Y.; Ke, J.; Fang, W.; Song, H.; Xu, C. and Yu, C, Nanotherapy in joints: increasing endogenous hyaluronan production by delivering hyaluronan synthase 2. Adv Mater 2019, 31(46):e1904535 . [CrossRef]

- Sayo, T.; Sugiyama, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Ozawa, N.; Sakai, S.; Ishikawa, O.; Tamura, M.; Inoue, S. Hyaluronan Synthase 3 Regulates Hyaluronan Synthesis in Cultured Human Keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 2002, 118(1):43-8. [CrossRef]

| N=21 (No. 01~02, 04~22) | ||

| Skin adverse reaction | After one-time use | After 2 weeks |

| 1. Erythema (redness) | 0 | 0 |

| 2. Edema (swelling) | 0 | 0 |

| 3. Squama (keratin) | 0 | 0 |

| 4. Itching | 0 | 0 |

| 5.Tingling sensations (pain) | 0 | 0 |

| 6. Burning sensation | 0 | 0 |

| 7. Stiffness | 0 | 0 |

| 8. Tingling | 0 | 0 |

| Symbol | Name | size (bp) | Primer (5'→ 3') |

| GAPDH | glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 380 | ATTCCATGGCACCGTCAAGG |

| TGATGGCATGGACTGTGGTC | |||

| GSTA4 | glutathione S-transferase alpha 4 | 332 | GAGGGGACACTGGATCTGCT |

| GGAGGCTTCTTCTTGCTGCC | |||

| FLG | filaggrin | 458 | AGTGAGGCATACCCAGAGGA |

| CCAAACGCACTTGCTTTACA | |||

| TGM1 | transglutaminase1 | 413 | AATCCTCTGATCGCATCACC |

| GTGGTCAAACTGGCCGTAGT | |||

| HAS1 | hyaluronan synthase 1 | 459 | ACTCGGACACAAGGTTGGAC |

| TGTACAGCCACTCACGGAAG | |||

| HAS2 | hyaluronan synthase 2 | 463 | TTTGGGTGTGTTCAGTGCAT |

| TAAGGCAGCTGGCAAAAGAT | |||

| HAS3 | hyaluronan synthase 3 | 493 | AGAAACCCGTGACCACTGAC |

| ACCATCGAGATGCTTCGAGT | |||

| AQP3 | aquaporin 3 | 427 | CACACGATAAGGGAGGCTGT |

| CCCTCATCCTGGTGATGTTT | |||

| KLK5 | kallikrein related peptidase 5 | 554 | TGTGACCACCCCTCTAACAC |

| TCCTCGCACCTTTTCTGACT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).