1. Introduction

Inflammation is a physiological response inherent to organisms with blood vessels, arising in reaction to damage or pathological stimuli induced by physical, chemical, or biological agents. It serves as a primary defense mechanism and is often marked by hallmark symptoms including swelling, pain, redness, and heat. Inflammation is initiated by vasodilation, fluid extravasation, or the release of growth mediators. In severe cases, inflammation may lead to impaired tissue function [

1,

2].

The immune response in the inflammatory process can be either innate (nonspecific) or adaptive (specific). The innate response is the initial reaction and acts rapidly against pathogens. Conversely, the adaptive response ensues later in response to a significant pathogen load, activating lymphocytes that identify and eliminate the invading antigen. This process establishes an immunological memory, enabling the organism to respond more efficiently upon re-exposure [

3].

A delicate balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators must be maintained to resolve inflammation. An imbalance can lead to a systemic inflammatory response [

4], and the prolonged presence of these stimuli can contribute to various disorders, including cancer, diabetes, obesity, arthritis, neurodegenerative conditions, and cardiovascular diseases [

5,

6].

Numerous medications can modulate the release of pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators to mitigate the inflammatory response by interfering with crucial pathways of the inflammatory cascade, including cyclooxygenases (COX), Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK), and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB), among others [

7]. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and steroidal drugs (SAIDs or glucocorticoids) are the most commonly prescribed medications for inflammatory disorders. Additionally, traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are administered to manage inflammatory arthritis, connective tissue diseases, and certain types of cancer [

8,

9,

10]. However, prolonged use of these drugs can lead to adverse effects such as weight gain, reduced carbohydrate tolerance, skin reactions, and irritation of the gastrointestinal mucosa [

11].

New therapies have targeted inflammatory cytokines and other mediators as effective targets for anti-inflammatory interventions. However, there is a heightened risk of exacerbating opportunistic infections or even triggering cancer [

12,

13].

Considering the common adverse effects associated with the use of conventional medications, it is imperative to explore phytotherapy. Utilizing medicinal plants offers an effective alternative to traditional therapies, with increased accessibility and reduced cost, which is particularly beneficial for economically disadvantaged populations. Moreover, certain groups of plants contain secondary metabolites with documented pharmacological activity [

14].

Brazilian traditional medicine utilizes the aqueous infusion and macerated bark of

V.

elongata, prepared with sugar cane brandy (cachaça) or white wine to address various ailments. These include infections, cancer, high cholesterol, heart, back, or stomach pain, gastric ulcer, uterine inflammation, snake bites, and wound healing [

15]. Previous studies investigating the hydroethanolic extract from the stem bark of

V.

elongata (HEVe) have revealed its gastroprotective and antioxidant properties while the phytochemical analysis has revealed the presence of phenolic compounds, flavonoids, alkaloids, and phytosterols. HEVe exhibits no cytotoxic effects in CHO-k1 and AGS cells [

16]. When acute toxicity was evaluated in mice, a single administration of HEVe (2000 mg/kg orally) did not result in animal mortality. Similarly, treatment with HEVe (300, 600, or 900 mg/kg orally) for 30 days did not induce subacute toxicity in rats [

17].

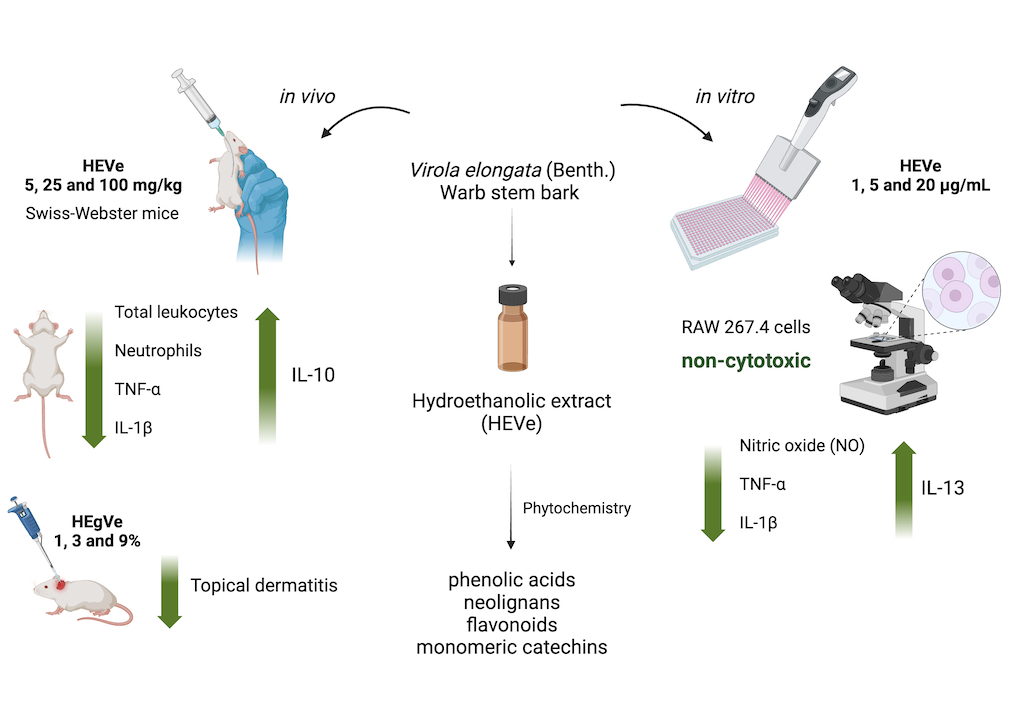

This research was undertaken to assess the anti-inflammatory activity and mechanism of action of HEVe in in vivo and in vitro models of acute inflammation given the extensive utilization of stem bark preparations from this species to address inflammation-related, coupled with the lack of studies validating this activity. Additionally, the study aimed to delineate the phytochemical profile of the extract.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

The stem bark of

V.

elongata was collected in the municipality of Santa Terezinha (10°26'54'' S, 50°37'41'' W), Mato Grosso (MT), Brazil, in August 2015. The research project leading to this article was registered in the National System for the Management of Genetic Heritage and Associated Traditional Knowledge (SisGen no. A070DE0A). Voucher speciments of flowers were deposited in the UFMT herbarium, and assigned specimen number 42580. The latest standardized name of the plant was verified using the Reflora (floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br) [

18] and World Flora Online (WFO) plant list (

https://wfoplantlist.org/) [

19].

2.2. Drugs, Reagents and Kits

Ultrapure water was generated using a Milli-Q system (Millipore, USA). Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), doxorubicin, lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli (serotype 055:B5), dexamethasone acetate, rezasurin, and croton oil were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (USA). Turk’s solution and Instant Prov® (Quick Panoptic dye) were obtained from New Prov, Brazil. Other reagents included 70% ethanol, trypan blue solution (Dinâmica Química Contemporânea Ltda, Brazil), ketamine and xylazine (Syntec, Brazil), lecithin (Lecigel®, Biovital, Brazil), and hydroxyethylcellulose (Natrosol®, Aqia, Brazil). Streptomycin, penicillin, fetal bovine serum (FBS), TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-10, and IL-13 ELISA detection kits were sourced from Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA.

2.3. Extract Preparation

The stem bark (2 kg) of V. elongata was cleansed, cut into 2 cm pieces, and then dried in an oven (model MA035/5 MARCONI, São Paulo, Brazil) with forced air circulation at 35 ± 1 ºC until reaching a constant weight, signifying complete moisture elimination. Subsequently, the dried bark was ground using a knife mill with a 40-mesh sieve (Tecnal TE-625, Brazil), and the resulting powder was macerated in a 70% hydroethanolic solution (1:3, w/v) for 7 days, with twice daily agitation. Following this period, the material was filtered through filter paper (No. 1), and the macerate obtained was concentrated using a rotary evaporator (model 801, Fisatom, Brazil) under reduced pressure (600 mmHg). Any residual solvent was eliminated by placing the extract in an oven at 38 ± 1 ºC for 48 h. The resulting extract was frozen at -86 ºC (Indrel® Ultra Freezer IULT 335D, Brazil) and then lyophilized (Scientific LJJ02, Brazil) to obtain the hydroethanolic extract of V. elongata (HEVe). This extract was identified, stored in amber bottles at -30 ºC (Brastemp, Brazil), and dissolved in sterile distilled water before use.

2.4. Gel Preparation

The HEVe gel (HEgVe) was formulated at the Formula Certa Manipulation Pharmacy in Cuiabá-MT, under the supervision of pharmacist Silveliane Nogueira Alves de Andrade. Initially, 0.15, 0.45, and 1.35 g of HEVe were weighed. A suitable amount of sterile distilled water was then added to each mass of HEVe for dilution, utilizing a vortex tube shaker (Coleman, Brazil). Subsequently, lecithin (Lecigel®, Biovital, Brazil), a powdered agent possessing emulsifying properties, was incorporated in the necessary quantity (q.s.) to enhance the viscosity and bioavailability of the active ingredient. Additionally, hydroxyethylcellulose (Natrosol®, Aqia, Brazil), an aqueous and non-ionic gelling agent, was added in sufficient quantity to achieve a total volume of 15 g for the incorporation of the active ingredient, resulting in HEgVe at concentrations of 1%, 3%, and 9%.

2.5. Animals

Female Swiss-Webster mice (Mus musculus) weighing 20 to 25 g were obtained from the central animal house of UFMT. The mice were housed for 5 days prior to experimentation in polypropylene cages under controlled environmental conditions (temperature: 25 ± 1 ºC; light/dark cycles: 12 h) and provided with a standard diet (Nuvlab® food, Quimtia, Brazil) and ad libitum access to treated water. Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles in animal experimentation established by the Brazilian College of Animal Experimentation (COBEA) and were approved by the Ethics Committee on the Use of Animals (CEUA) of UFMT under authorization number 23108.01799/2022-47.

2.6. Cell Line

RAW 264.7 murine macrophages (BCRJ, code: 0212) were obtained from the cell bank of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (BCRJ), Brazil. Upon thawing, the cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), supplemented with streptomycin (10 mg/mL), penicillin (6 mg/mL), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% non-essential amino acids, and 1% glutamine at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

2.7. Phytochemical Analysis

The HEVe underwent solid-phase extraction (SPE) clean-up using a C18 cartridge (3 mL, Macherey-Nagel, Chromabond C18, Duren, Germany; particle size 45 μm, diameter and pore size 60 Å). Initially, 10 mg of HEVe was dissolved in 1.5 mL of methanol:water (MeOH:H2O, 80:20, v/v; MeOH: LC-MS grade, LiChrosolv®, and ultrapure MilliQ® EQ 7000 water). The cartridge was preconditioned with 450 µL of MeOH and 450 µL of MeOH:H2O (80:20, v/v). Subsequently, sample of the extract was added to the cartridge and eluted with 1.5 mL of MeOH:H2O (80:20, v/v). The eluate was collected and dried under compressed air at room temperature. The dried sample was then dissolved in methanol to a concentration of 10 ppm and analyzed by mass spectrometry.

Direct flow infusion coupled with electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (DFI-ESI-IT-MSn) and ultra high performance iquid chromatography coupled to photodiode array and electrospray ionization mass detectors (UHPLC-PDA-ESI-MSn) analysis

Direct flow infusion of the samples was conducted on a Thermo Scientific LTQ XL linear ion trap analyzer equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source, operating in negative mode (Thermo, USA) (DFI-ESI-IT-MSn). A fused-silica capillary tube was utilized at 300 ◦C, with a spray voltage of 4.5 kV, capillary voltage of - 47 V, and tube lens voltage of - 226 V. Nitrogen (a flow of 50 arbitrary units) and helium (a flow of 10 arbitrary units) were employed as gases. Initially, a full scanning of the mass spectrum was performed to acquire the ions’ data within the established m/z range of 100-2,000. Subsequently, MSn experiments were carried out based on the data obtained in the initial scan, targeting preselected precursor ions, and utilizing a collision energy of 30% and an activation time of 30 ms.

UHPLC-PDA-ESI-IT-MS analysis was conducted using a Thermo Scientific ultra-performance liquid chromatography system, comprising an Accela AS autosampler and a quaternary Accela pump 600 coupled with the LTQ XL linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo, USA). Chromatographic separations were performed on a C18 reversed-phase column (Phenomenex®️ Luna C18 column, 250 x 4.6 mm, 5 µm). The injection volume was 10 µL, and the flow rate was set at 350 μL/min. The column temperature was maintained at 25 °C, and UV detection was conducted at 254 and 354 nm. Sample elution was achieved using a linear gradient of water acidified with 0.1% formic acid (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B), ranging from 5 to 100% (B) over 60 min. Data acquisition and processing were performed using Xcalibur™ version 1.3 (Thermo Finigan, USA) software.

2.8. In Vivo Assays

The doses of HEVe chosen for this trial were based on the work of Almeida et al. (2019)16, which used doses of 100, 300 and 900 mg/kg p.o. in antiulcer activity trials; these doses were equally effective in most trials. Therefore, the lowest dose (100 mg/kg) with antiulcer activity was selected and from this, lower (5 mg/kg) and intermediate (25 mg/kg) doses were determinated to evaluate the anti-inflammatory effect of HEVe.

2.8.1. Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Peritonitis

The peritonitis model [

20] was employed to assess the anti-inflammatory potential of HEVe. Following a 12-h fast for food and a 1-h fast for water, female mice (n=8/group) were pretreated via orogastric gavage (p.o.), with either vehicle (distilled water, 0.1 mL/10 g b.w.), HEVe (at doses of 5, 25, and 100 mg/kg), or dexamethasone (0.5 mg/kg). The naive group received distilled water (0.1 mL/10 g) via the same route. Subsequently, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from

Escherichia coli serotype 055:B5 (250 ng/well/0.2 mL in sterile 0.9% saline solution) was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.), except for the naive group, which received an equal volume of 0.9% sterile saline solution i.p. Six hours post-inflammatory stimulus, mice were euthanized with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) overdose of ketamine and xylazine, followed by injection of 3 mL of ice-cold 0.1% phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% bovine serum albumin. Peritoneal lavage was collected and utilized for total and differential leukocyte counts. Aliquots of the peritoneal lavage were centrifuged at 3,100 x g for 10 min, and the supernatant was stored at -86 ºC for subsequent determination of cytokines [

21].

2.8.1.1. Total and Differential Leukocyte Count

Peritoneal lavage was utilized for both total and differential leukocyte cell counts. The total leukocyte count was determined by diluting 20 µL of the lavage in 380 µL of Turk’s solution (1:19 v/v), and the count was performed using a Neubauer chamber under an optical microscope at 100x magnification. For the differential count, slides were prepared by smearing 20 µL of peritoneal lavage and staining with Instant Prov® dye (New Prov, Brazil). A total of 100 cells per slide were counted under the microscope, and they were classified as polymorphonuclear (PMN) or mononuclear (MN) based on conventional morphological criteria. The results were expressed as the number of cells x 106.

2.8.1.2. Cytokine Assay

The concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-10 in the peritoneal lavage of mice were assessed using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits, following the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a microplate reader spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific), and the results were graphically expressed in pg/mL.

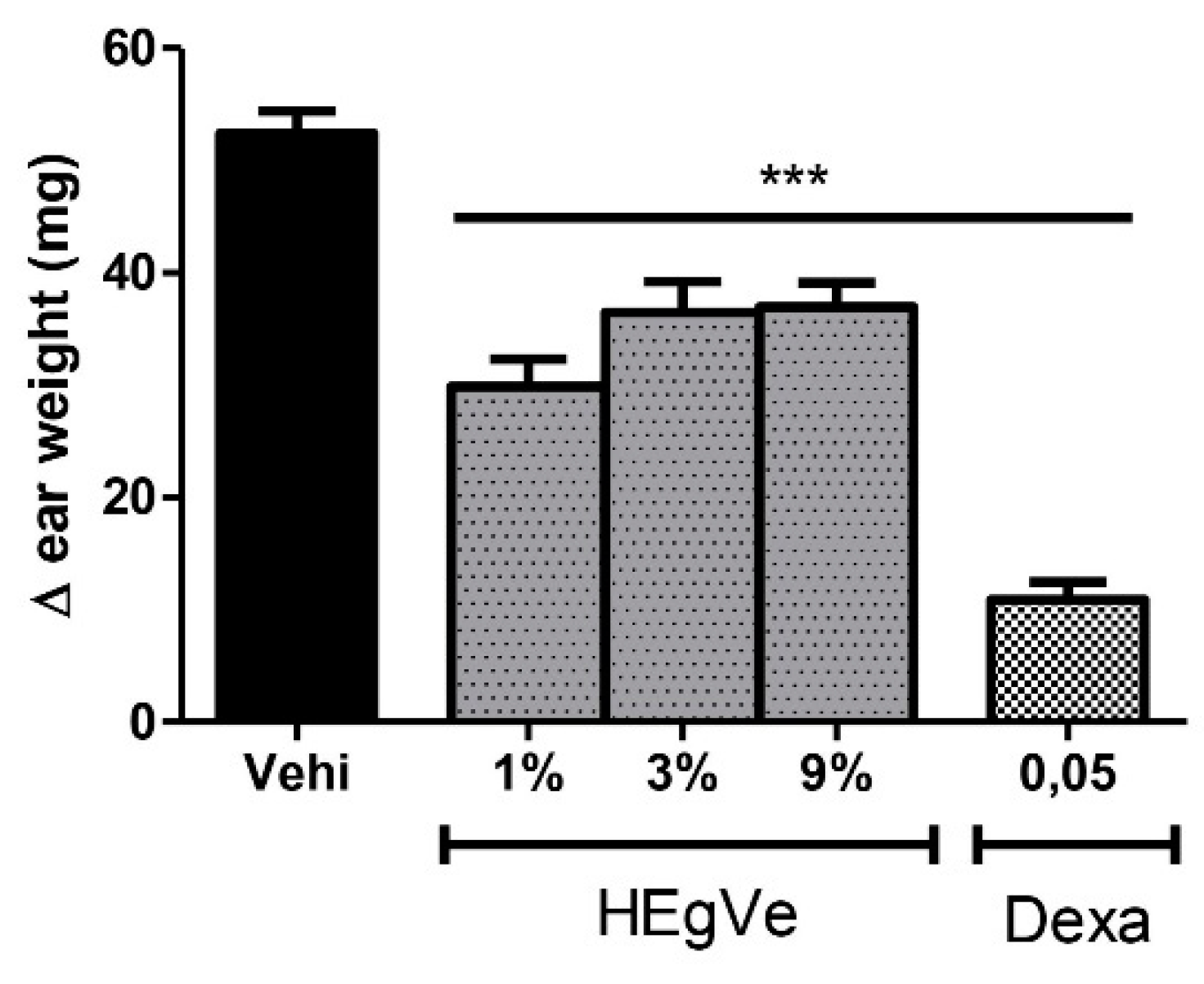

2.8.2. Croton Oil-Induced Topical Dermatitis

Topical dermatitis [

22] was used to evaluate the potential local anti-inflammatory effect of HEgVe. The inner surface of both ears of mice (n=8/group) was topically treated with either vehicle (Natrosol

® gel) or HEgVe (at concentrations of 1%, 3%, and 9%), or 0.25% dexamethasone (0.05 mg/ear/20 µL). After 25 min, 20 µL of croton oil (2.5% in acetone:water, 7:3 v/v) was applied to the left ear of each animal, while 20 µL of acetone:water (7:3 v/v) was applied to the right ear, serving as a control. Six hours after the administration of the inflammatory stimulus, the animals were euthanized with an anesthetic overdose of xylazine (30 mg/kg) and ketamine (300 mg/kg) intraperitoneally (i.p.), and both ears were excised at the base and weighed individually. Topical inflammation was assessed by the local edema formed, calculated by the differences in weight (Δ mg) between the left (inflamed) and right (uninflamed) ear.

2.9. In Vitro Assays

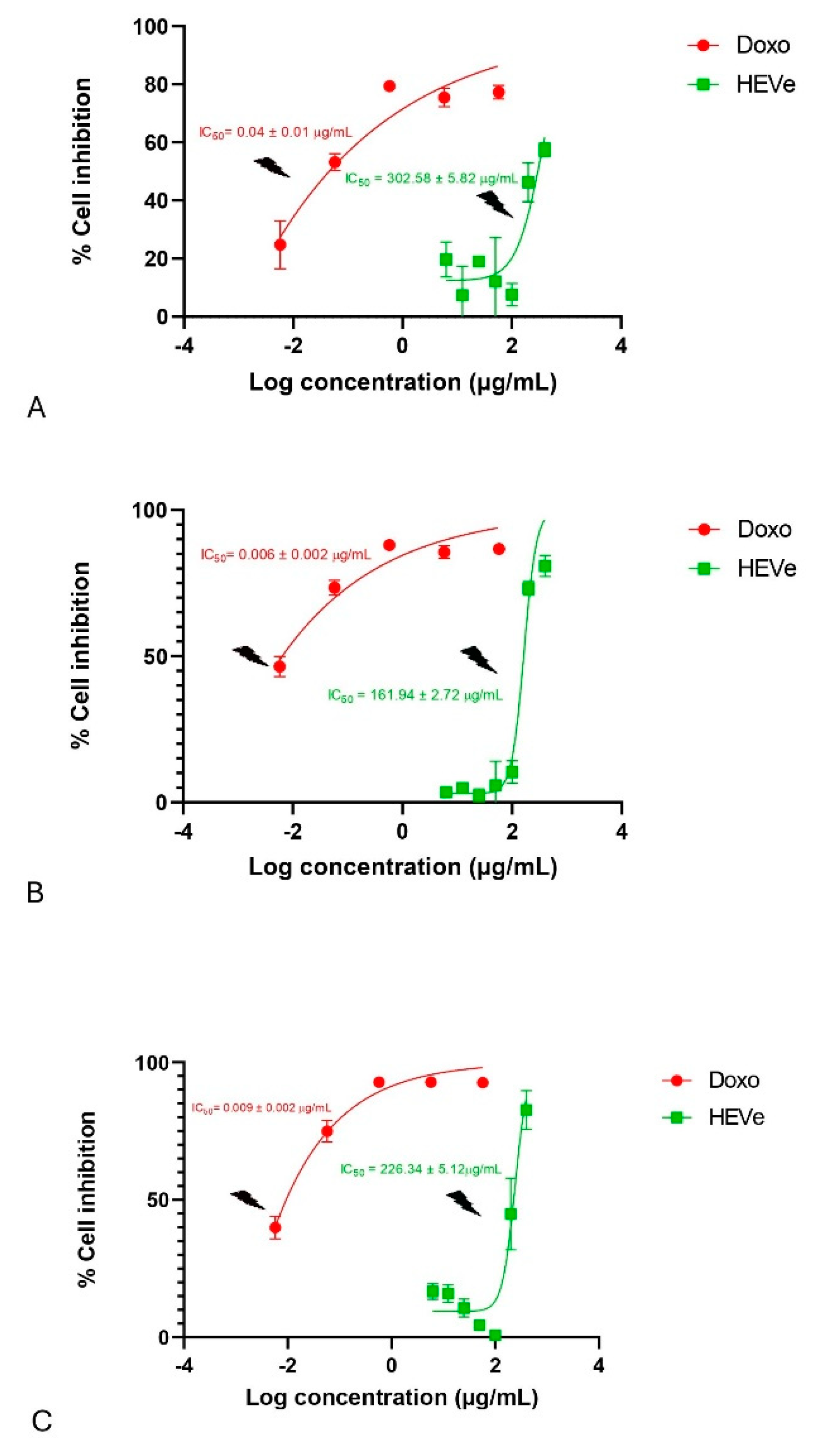

2.9.1. Cell Viability Assay

This assay was conducted to determine non-cytotoxic concentrations of HEVe for use in in vitro pharmacological assays. The Alamar Blue® (resazurin) test, based on Nakayama’s colorimetric method [

23], was employed to assess cell viability. RAW 264.7 cells, cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO

2, were seeded at a density of 2x10

4 cells/mL in duplicate in a 96-well plate. The wells were filled with DMEM culture medium (sterility control) supplemented with 10% FBS, and after 24 h, treated with various concentrations of HEVe (ranging from 6.25 to 400 µg/mL) and doxorubicin (0.01 to 100 µg/mL) as a positive control. After 1 h, the cells were stimulated with LPS (1 µg/mL), and at 24, 48, and 72 h, the treatments were removed, and rezasurin (10% v/v) in DMEM medium was added to the plates. The plates were then incubated for 6 h at 37 °C and 5% CO

2 for reading. The percentages of resazurin and its reduced form (resorufin) were calculated, and the results were expressed as the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC

50), which represents the concentration of the drug that inhibits 50% of the cells. The samples were read using a microplate reader at absorbances of 540 and 620 nm. IC

50 values less than 4 µg/mL and 30 µg/mL were considered cytotoxic for pure and impure substances, respectively [

24].

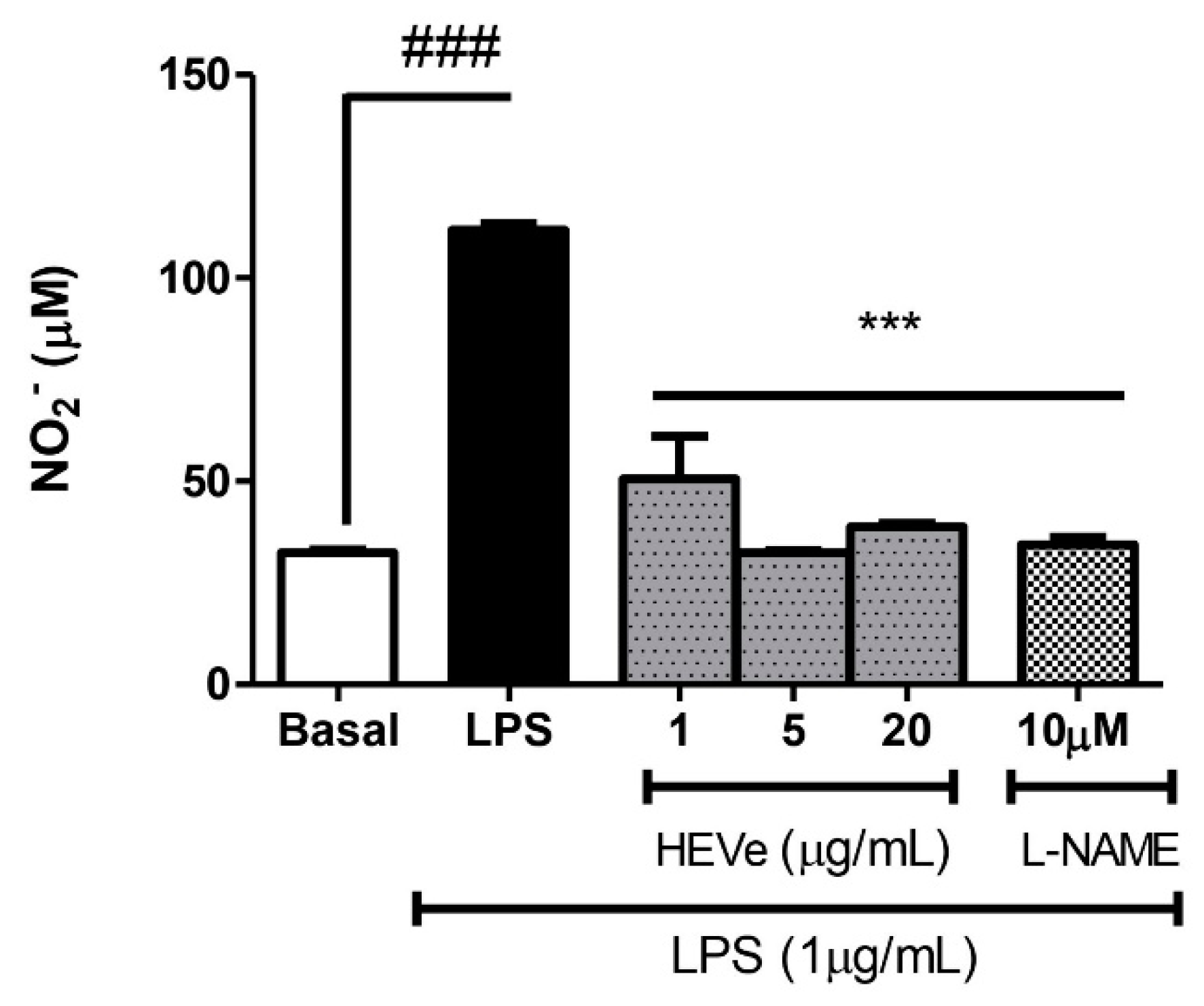

2.9.2. Indirect Determination of Nitric Oxide Production

NO production was determined by the quantity of nitrite (NO2-), which was calculated using the colorimetric method based on the Griess reaction25. RAW 264.7 cells were treated with three concentrations of HEVe (1, 5, and 20 µg/mL) and Nω-Nitro-L-arginine-methyl-ester (L-NAME, 10 mM). Cells were also maintained with only the culture medium and no phenol red (for basal control). After 1 h, they were stimulated with LPS (1 µg/ml), except for the basal group. After 24 h in the oven, the supernatant was collected (100 µL) after 30 min in the centrifuge at 15,000 x g and incubated with an equal volume of Griess reagent (1% sulfanilamide, 0.1% N-(1-naphthyl)-ethylenediamine dihydrochloride, 2.5% H3PO4) in another 96-well culture plate for 15 min at room temperature. The absorbance (540 nm) was measured in an automatic microplate reader, and nitrite concentrations were calculated by extrapolation to a sodium nitrite (NaNO2) standard curve, with data expressed in μM.

2.9.3. Cytokine Assay

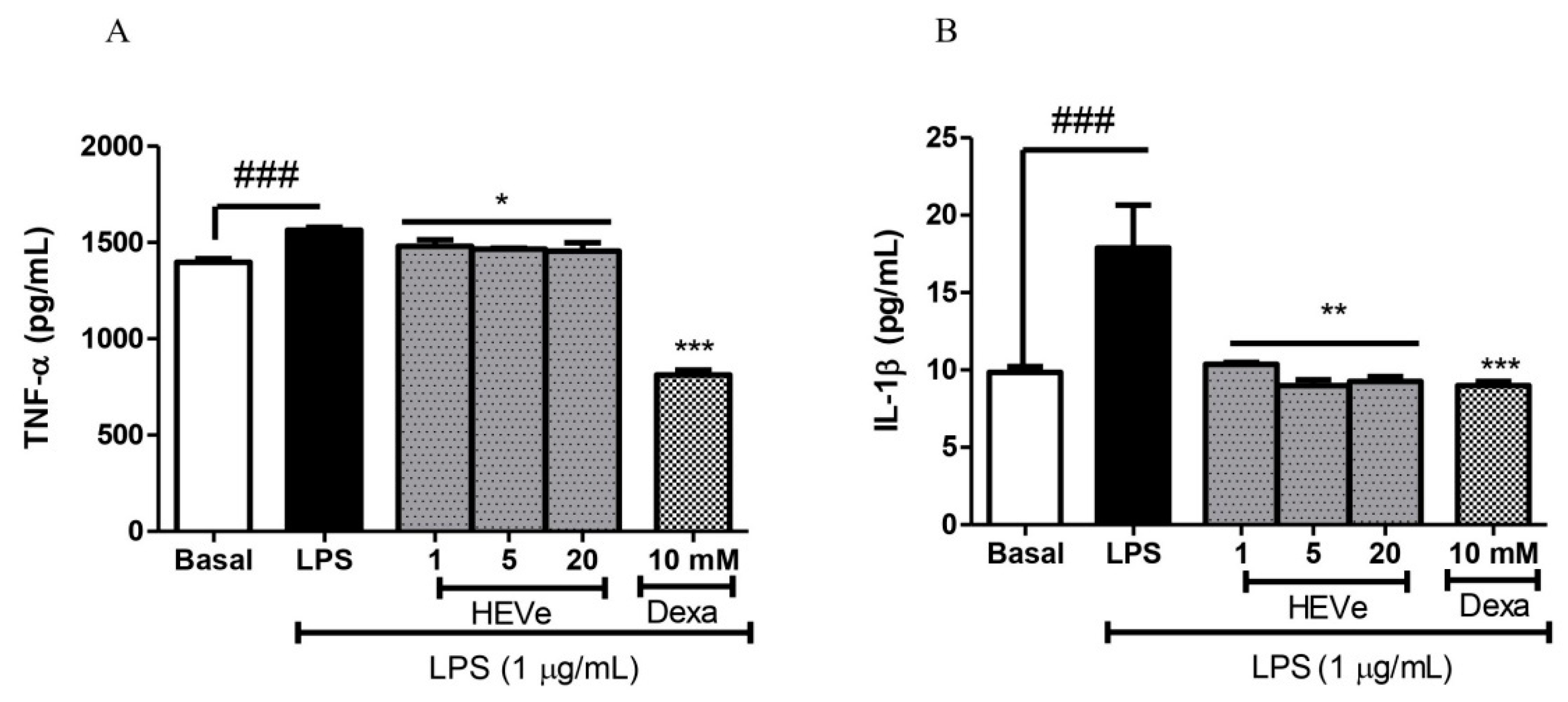

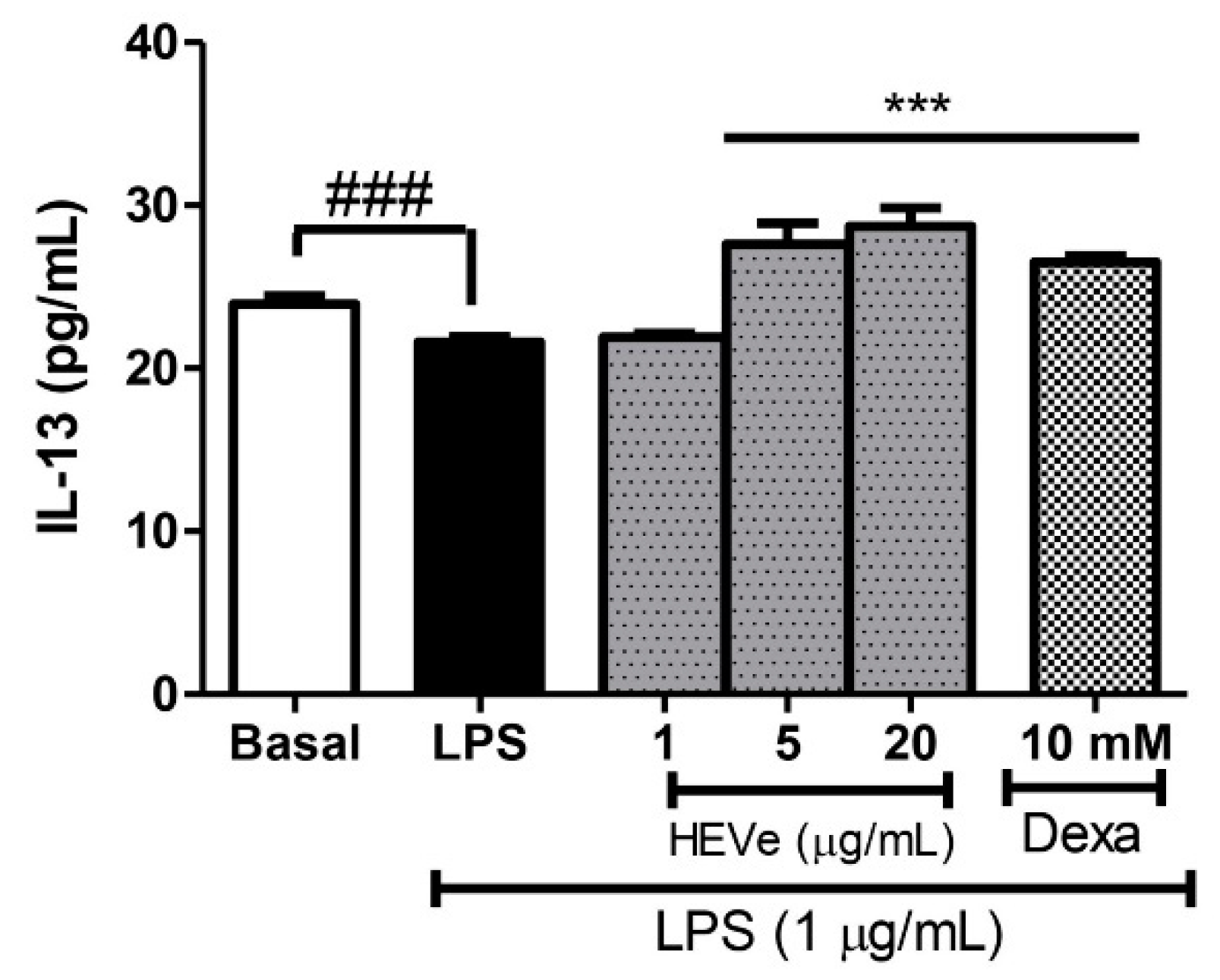

Initially, RAW 264.7 cells were seeded at a density of 1.5 x 105 cells/well in 24-well plates and incubated in DMEM culture medium supplemented with fetal bovine serum (10%) overnight at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Following a 1-h treatment with HEVe (1, 5, and 20 µg/mL) and dexamethasone (10 mM), cells were stimulated with LPS (1 µg/mL). A control group was maintained with only the culture medium (for basal control). After 24 h of incubation, the supernatant from the stimulated cells was collected, centrifuged at 15,000 x g for 30 min, and stored at -86 ºC for subsequent cytokine quantification. TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-13 concentrations in RAW 264.7 cells stimulated by LPS (1 µg/mL) were determined using commercially available ELISA kits following the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Absorbance readings were taken at 540 nm using a spectrophotometric microplate reader (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA), and the results were graphically expressed in pg/mL.

2.10. Data Analysis

Parametric data were presented as mean ± standard error (S.E.) and analyzed using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) technique for group comparison. Post hoc analysis was performed using the Student-Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test whenever statistical significance was observed. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The IC50 value was determined by linear regression, correlating the percentage of inhibition with the logarithm of the concentrations tested, with a confidence level of 99% (p < 0.01) for the curve. In vitro assay results that did not involve statistical analysis were expressed as the mean ± standard error (S.E.) of two or three independent experiments. Data tabulation and analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 5.01, USA).

4. Discussion

The riverine community of Mato Grosso, a North Araguaia Microregion, utilizes an aqueous infusion or maceration of dried stem bark of

V.

elongata in cachaça or white wine to treat inflammations and other illnesses [

15]. To emulate the traditional method of use, this study prepared an extract of

V.

elongata (HEVe) was prepared for this study by macerating the inner stem bark in a hydroethanolic solution.

To assess the activity and anti-inflammatory mechanism of HEVe, this study employed in vivo experimental models of LPS-induced acute peritonitis and topical dermatitis induced by applying 2.5% croton oil to the ears of female mice, alongside in vitro assays using RAW 264.7 cells stimulated by LPS. Additionally, the phytochemical composition of HEVe was determined using UHPLC-PDA-ESI-IT-MS analysis.

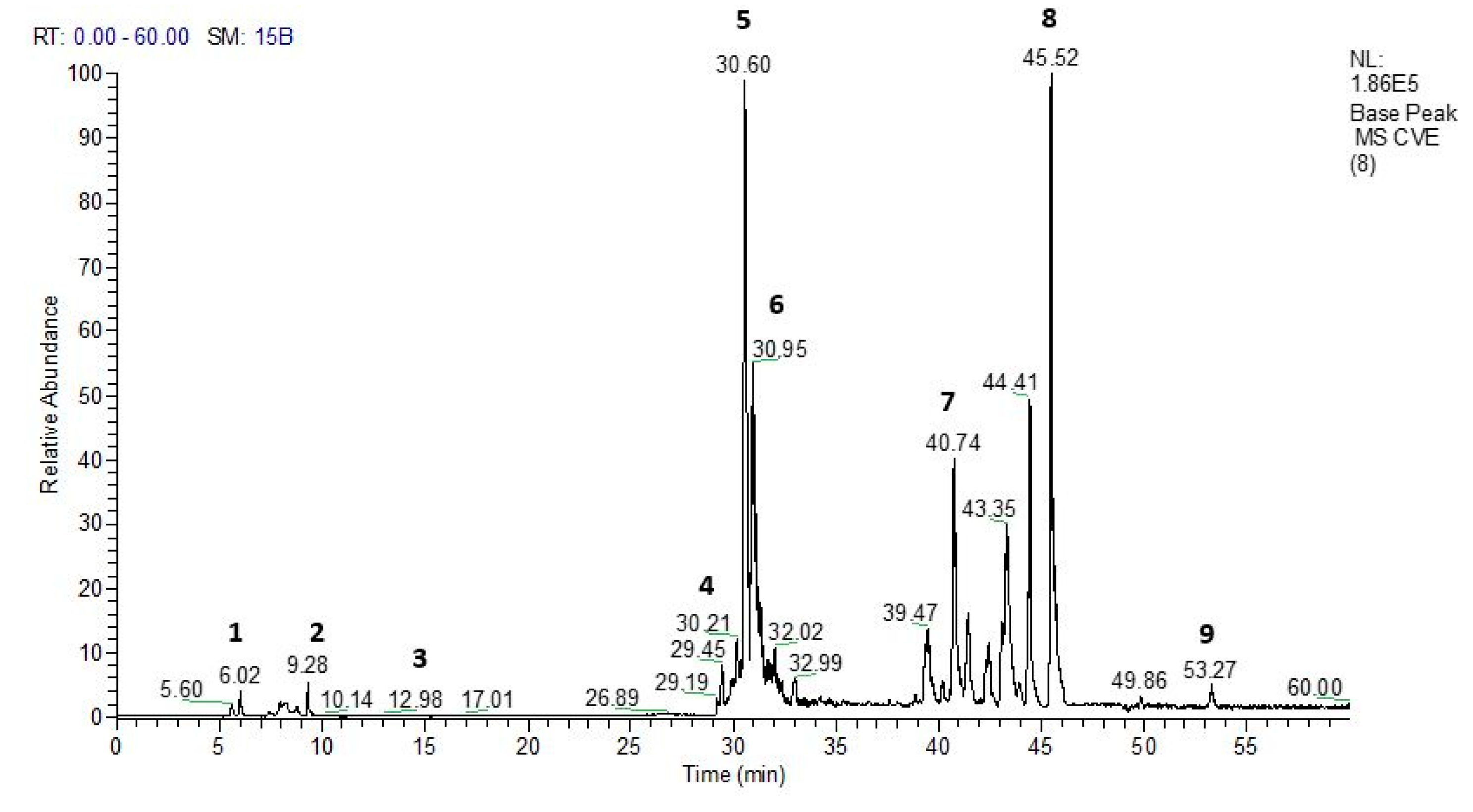

Mass spectrometry analysis revealed the presence of an important stilbene compound, resveratrol (3,4',5-trihydroxystilbene), and a phenolic acid, quinic acid, which were identified in the UHPLC-MS chromatogram. Some of the anti-inflammatory effects of resveratrol are attributed to its ability to inhibit the production of IL-2 and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) by lymphocytes and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) or IL-12 by macrophages [

29]. Quinic acid, previously identified

16, is a phenolic acid that inhibits vascular inflammation in vascular smooth muscle cells stimulated by TNF-α [

30]. UHPLC-MS also identified a compound from the lignan class (3',4'-dimethoxy-3,4-methylenedioxy-6 7',8 8'-neolignan). Some articles report that dietary lignans and their metabolites derived from the intestinal microbiota control the inflammatory response by suppressing inflammatory pathways by blocking the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines through the negative regulation of the JAK/STAT, NF-κB and AP-1 [

31].

Flavonoids are among the most prevalent polyphenols found in plants and fruits. They are widely utilized to treat chronic inflammation and as dietary supplements [

32]. According to Maleki et al. [

33], flavonoids impact the metabolism of arachidonic acid by inhibiting PLA

2, COX, and LOX enzymes, thus reducing the production of pro-inflammatory mediators such as PGs, TXs, and leukotrienes. Additionally, they modulate transcription factors like NF-κB, GATA-3, and STAT-6, leading to decreased transcription of pro-inflammatory genes.

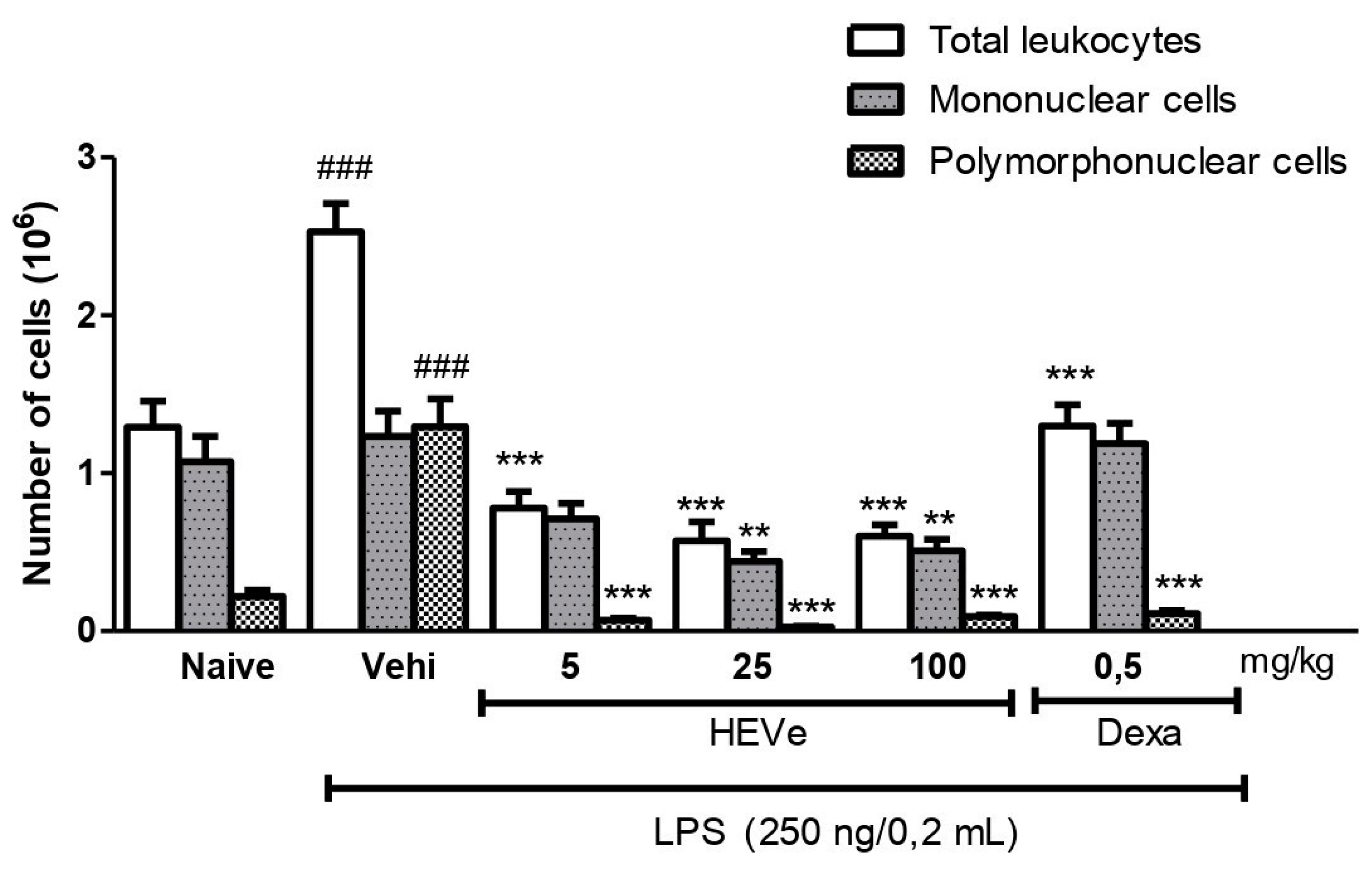

The effect of HEVe on leukocyte recruitment was evaluated by inducing acute peritonitis in animals by intraperitoneal injection of the endoxin LPS, the main component in the membranes of Gram-negative bacteria) [

34]. The induction of peritonitis produces an inflammatory response in the peritoneal cavity, increasing the amount of existing proteins and the number of defense cells (leukocytes) in the exudate, with a predominance of polymorphonuclear cells [

35,

36].

Based on the literature, it is plausible that the anti-inflammatory properties of HEVe stem, at least in part, from the collective action of phenolic acids, neolignans, and flavonoids. Further studies are warranted to isolate these compounds and conduct tests to ascertain whether they are active markers of HEVe or merely analytical indicators. In the experimental model of acute peritonitis, mice pre-treated with HEVe (5, 25, and 100 mg/kg) showed a reduction in the total number of leukocytes, and polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), which are the major effectors of the acute inflammatory response [

37]. The reduced presence of these cells in the peritoneal lavage indicates reduced cell migration, suggesting that the anti-inflammatory action of the extract involves this mechanism.

The inflammatory process involves the recruitment of certain cells to the site of inflammation, which generates a local response to combat the phlogistic agent [

38]. PMNs are the first cells to migrate to the inflamed site, being the host’s initial defense against several pathogens [

39] such as LPS, which can stimulate the cells that secrete pro-inflammatory (e.g.,TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β and IFNɣ) and anti-inflammatory (e.g., IL-4, IL-10, IL-11, and IL-13) cytokines [

40,

41,

42].

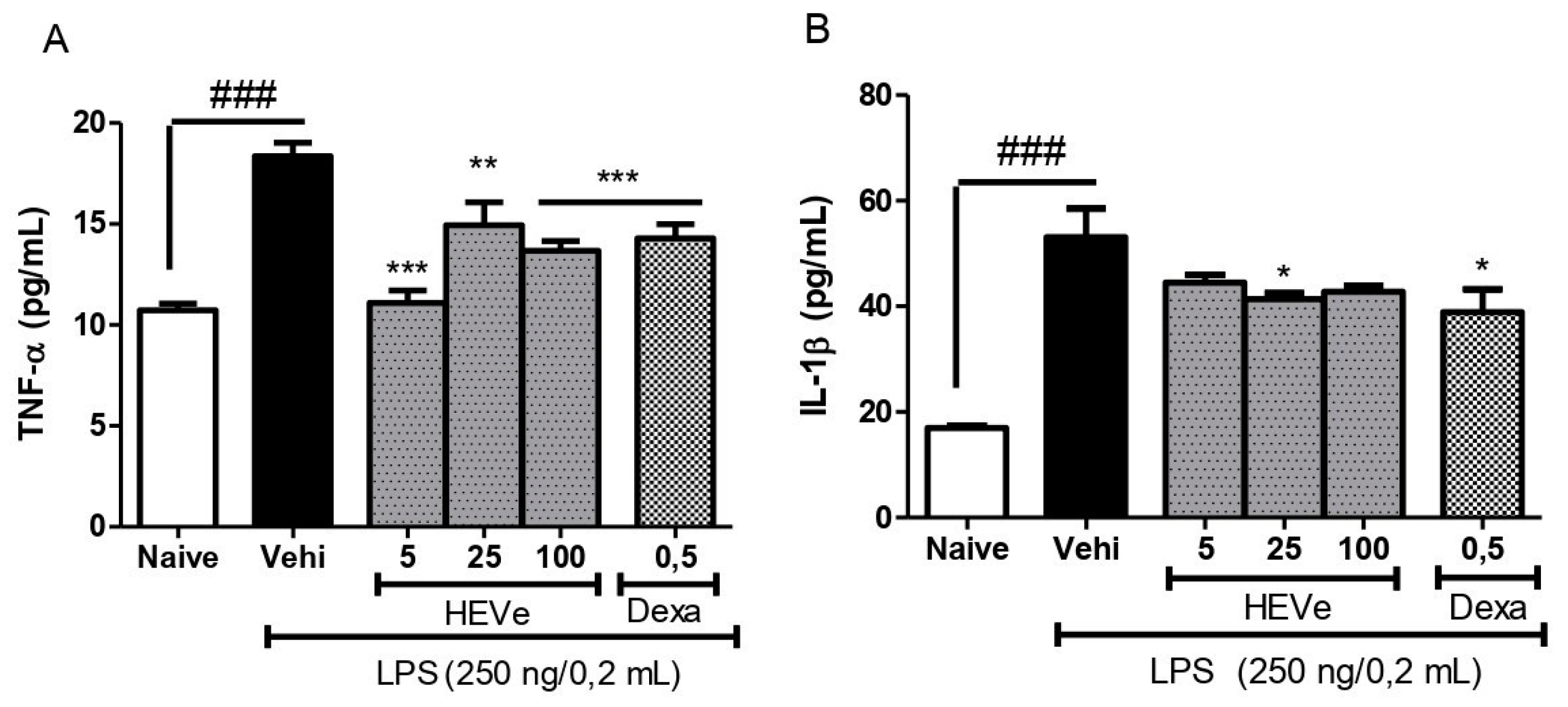

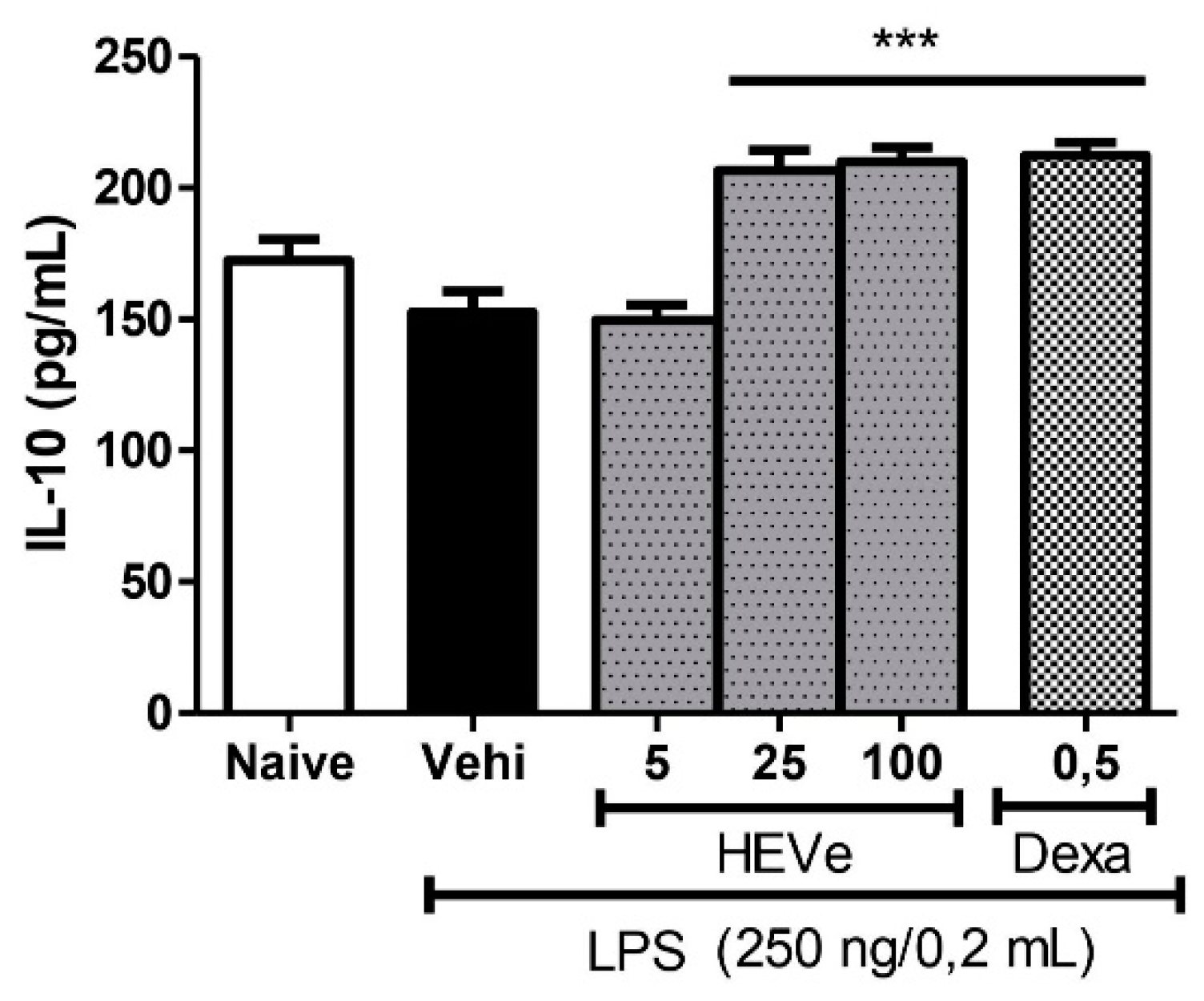

The quantification of cytokines provides valuable insights for monitoring patient’s immune system status and adjusting therapies for various inflammatory conditions [

43]. We measured TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-10 levels in peritoneal lavage to assess the involvement of cytokines in the anti-inflammatory effect of HEVe. Pretreatment with HEVe resulted in reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1β) and increased levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β play crucial roles in immune responses, serving as vital mediators that communicate tissue distress due to infection or injury. Inhibiting excessive levels of these cytokines by HEVe can lead to reduced cellular activation, including macrophages, thereby modulating the immune response and, consequently, dampening the acute phase of inflammation [

44].

A range of immunoregulatory molecules, including IL-10, are produced to mitigate the potentially detrimental effects of sustained or excessive pro-inflammatory reactions [

43]. IL-10 functions by inhibiting the production of various pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IFN-ɣ, expressed by activated macrophages. Additionally, it promotes the proliferation of B cells and antibody production while suppressing cellular immunity and mast cell growth [

42]. The increased levels of IL-10 induced by HEVe can mitigate inflammation progression progression by modulating the extent and duration of the inflammatory response [

14,

45]. After HEVe’s anti-inflammatory effect on lipopolysaccharide-induced peritonitis was demonstrated, its local anti-inflammatory effect was evaluated using the topical dermatitis model, induced by the topical application of croton oil in the ears of female mice. Tetradecanoyl-phorbol acetate is a highly irritating substance derived from croton oil, which stimulates an inflammatory response in the epidermis, through changes in the production of cytokines, adhesion molecules, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes [

46]. Topical pre-treatment with HEgVe (1, 3, and 9%) promoted edema inhibition, which may be associated with the consequent reduction of inflammatory factors, such as vascular permeability, vasodilation and swelling [

47].

In vitro experimental tests were conducted on RAW 264.7 murine macrophage cells to assess whether the anti-inflammatory action of HEVe stems from a direct effect on inflammatory cells.

Murine macrophage cells have been widely utilized in studies due to their ease of cultivation and rapid growth [

44], alongside their pivotal roles in the inflammatory response. Hence, preclinical evaluation in these cells is a crucial step in analyzing the efficacy of novel anti-inflammatory drug candidates, as the cells undergo various processes such as phagocytosis, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and cytokine secretion when stimulated by LPS [

49,

50].

RAW 264.7 cells stimulated with LPS (1 µg/mL) were pretreated with different concentrations of HEVe (6.25 - 400 µg/mL) to determine the appropriate concentrations of HEVe for in vitro experiments, and cell viability was assessed using the Alamar Blue® (resazurin) assay at 24, 48, and 72 h. Similar to its non-cytotoxic effects in CHO-K1 cells at 24 and 72 h (IC

50 > 200 μg/mL)

17, HEVe exhibited an IC

50 of 288 ± 19.56 μg/mL at 24 h in these RAW 264.7 studies. Consequently, concentrations of 1, 5, and 20 µg/mL were selected for further investigations of HEVe’s anti-inflammatory properties. Consistent with in vivo assays, pretreatment with HEVe also mitigated inflammatory effects in RAW 264.7 cells by directly reducing levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α, while increasing levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-13. The reduction of excessive concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines in RAW 264.7 cells caused by HEVe may result from the direct suppression of specific cytokine pathways, preventing the development of pathological states through the exacerbated expression of immunological mediators [

40,

48]. The increase in IL-13 levels caused by HEVe favors the inhibition of inflammatory effects due to the reduction in the expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1 in endothelial cells, the proliferation of B cells, and the inhibition of many pro-inflammatory cytokines, inflammatory agents and other mediators of inflammation (e.g., granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) PGs, reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates)[

40,

51]. Based on these findings, it can be stated that the anti-inflammatory effect of HEVe results from changes in the balance of cytokine production.

Another crucial inflammatory mediator is NO, which, at normal levels, plays roles in maintaining low vascular tone, preventing leukocyte and platelet adhesion to the vascular wall, and neuromodulation. However, during the inflammatory process, the production of nitric oxide in macrophages is activated by the enzyme inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), leading to the release of large amounts of NO, which can be toxic to the organism [

53,

54].

Due to its instability, NO rapidly convertsto nitrate and nitrite [

24]. Therefore, the indirect production of NO was determined by measuring NO

2- levels in RAW 264.7 cells stimulated by LPS was carried out. Treatment with HEVe (1, 5, and 20 µg/mL) resulted in a significant reduction in NO levels, which may be attributed to the consequent inhibition of iNOS. This reduction could mitigate effects such as tissue and endothelial damage, vascular permeability, and vasodilation [

53,

55]. These findings align with the results of Carvalho et al.[

56], who reported that the resin of

Virola oleifera directly inhibited the LPS-induced production of NO in RAW 264.7 cells. Previous studies of HEVe reported gastroprotective and antioxidant activity, and identified its secondary metabolites as phenolic acids (gallic acid), stilbenes (3,3,4 – trihydroxystilbene), flavonoids (catechin and rutin), and neolignans (arylnaphthalene and dibenzylbutane) [

16].

Phenolic compounds, such as gallic acid, exhibit anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity [

57]. Similarly, stilbenes, synthesized by plants like grapes, peanuts, rhubarb, and berries, serve as defense mechanisms against stressful conditions [

58].

Corroborating the findings of Ribeiro et al.[

15], which highlighted the traditional use of macerated extract of

V. elongata’s dried inner stem bark in cachaça for inflammation treatment, our in vivo and in vitro analyses of HEVe confirmed the anti-inflammatory activity of this species’ bark. HEVe reduced total leukocytes and PMN counts in the peritoneal cavity of mice, partially inhibited the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β, and increased the level of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. Meanwhile, in studies involving RAW 264.7 cells, HEVe exhibited low cytotoxicity, decreased nitric oxide and pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and elevated the levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-13. These results are likely driven by the activity of HEVe’s secondary metabolites.

Figure 1.

UHPLC-PDA-ESI-IT-MSn analysis of the hydroethanolic extract of Virola elongata inner stem bark (HEVe) was conducted, with detection using Base Peak Ion (BPI).

Figure 1.

UHPLC-PDA-ESI-IT-MSn analysis of the hydroethanolic extract of Virola elongata inner stem bark (HEVe) was conducted, with detection using Base Peak Ion (BPI).

Figure 2.

Effect of oral administration of vehicle (Vehi 0.1 mL/10 g distilled water), hydroethanolic extract from the inner stem bark of Virola elongata (HEVe 5, 25, and 100 mg/kg), and dexamethasone (Dexa 0.5 mg/kg) on total cells, mononuclear (MN) cells, and polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells present in the intraperitoneal fluid of mice with LPS-induced peritonitis (250 ng/0.2 mL/well). Each column represents the meanE of 8 animals/group. One-way ANOVA, followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test, ### p < 0.001 vs. Naive, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 vs. Vehi.

Figure 2.

Effect of oral administration of vehicle (Vehi 0.1 mL/10 g distilled water), hydroethanolic extract from the inner stem bark of Virola elongata (HEVe 5, 25, and 100 mg/kg), and dexamethasone (Dexa 0.5 mg/kg) on total cells, mononuclear (MN) cells, and polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells present in the intraperitoneal fluid of mice with LPS-induced peritonitis (250 ng/0.2 mL/well). Each column represents the meanE of 8 animals/group. One-way ANOVA, followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test, ### p < 0.001 vs. Naive, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 vs. Vehi.

Figure 3.

Effect of oral administration of the vehicle (Vehi 0.1 mL/10 g of distilled water), hydroethanolic extract from the inner stem bark of Virola elongata (HEVe 5, 25, and 100 mg/kg), and dexamethasone (Dexa 0.5 mg/kg) on (A) the concentration of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and (B) interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) in the peritoneal lavage of mice with peritonitis induced by intraperitoneal injection of LPS (250 ng/well/0.2 mL). The Naive group received distilled water (0.1 mL/10 g p.o.) and 0.9% saline (0.2 mL/well i.p.). Each column represents the meanE of 8 animals/group. One-way ANOVA, followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test, *p < 0.05 vs. Vehi, **p < 0.01 vs. Vehi, ***p < 0.001 vs. Vehi, ### p < 0.001 vs. Naive.

Figure 3.

Effect of oral administration of the vehicle (Vehi 0.1 mL/10 g of distilled water), hydroethanolic extract from the inner stem bark of Virola elongata (HEVe 5, 25, and 100 mg/kg), and dexamethasone (Dexa 0.5 mg/kg) on (A) the concentration of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and (B) interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) in the peritoneal lavage of mice with peritonitis induced by intraperitoneal injection of LPS (250 ng/well/0.2 mL). The Naive group received distilled water (0.1 mL/10 g p.o.) and 0.9% saline (0.2 mL/well i.p.). Each column represents the meanE of 8 animals/group. One-way ANOVA, followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test, *p < 0.05 vs. Vehi, **p < 0.01 vs. Vehi, ***p < 0.001 vs. Vehi, ### p < 0.001 vs. Naive.

Figure 4.

Effect of oral administration of the vehicle (Vehi 0.1 mL/10 g of distilled water), hydroethanolic extract from the inner stem bark of Virola elongata (HEVe 5, 25, and 100 mg/kg), and dexamethasone (Dexa 0.5 mg/kg), on the concentration of interleukin 10 (IL-10) in the peritoneal lavage of mice with peritonitis induced by intraperitoneal injection of LPS (250 ng/well/0.2 mL). The Naive group received distilled water (0.1 mL/10 g p.o.) and 0.9% saline (0.2 mL/well i.p.). Each column represents the meanE of 8 animals/group. One-way ANOVA, followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test, ***p < 0.001 vs. Vehi.

Figure 4.

Effect of oral administration of the vehicle (Vehi 0.1 mL/10 g of distilled water), hydroethanolic extract from the inner stem bark of Virola elongata (HEVe 5, 25, and 100 mg/kg), and dexamethasone (Dexa 0.5 mg/kg), on the concentration of interleukin 10 (IL-10) in the peritoneal lavage of mice with peritonitis induced by intraperitoneal injection of LPS (250 ng/well/0.2 mL). The Naive group received distilled water (0.1 mL/10 g p.o.) and 0.9% saline (0.2 mL/well i.p.). Each column represents the meanE of 8 animals/group. One-way ANOVA, followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test, ***p < 0.001 vs. Vehi.

Figure 5.

Difference in weight of the ears of female mice after topical treatment with the vehicle [Vehi 20 µL of 2.5% croton oil in acetone:water (70:30)], hydroethanolic extract gel from the inner stem bark of Virola elongata (HEgVe 1, 3, and 9%), and dexamethasone (Dexa 0.05 mg/ear/20 µL). Each column represents the meanE of 8 animals/group. One-way ANOVA, followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test, *** p < 0.001 vs. Vehi.

Figure 5.

Difference in weight of the ears of female mice after topical treatment with the vehicle [Vehi 20 µL of 2.5% croton oil in acetone:water (70:30)], hydroethanolic extract gel from the inner stem bark of Virola elongata (HEgVe 1, 3, and 9%), and dexamethasone (Dexa 0.05 mg/ear/20 µL). Each column represents the meanE of 8 animals/group. One-way ANOVA, followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test, *** p < 0.001 vs. Vehi.

Figure 6.

Cytotoxicity assesment of the hydroethanolic extract from the bark of the stem of Virola elongata (HEVe 6.25 - 400 µg/mL) and doxorubicin (Doxo 0.01 – 100 µM) in RAW 264.7 cells stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS 1 µg/mL) for 24 (A), 48 (B), and 72 h (C). Inhibitory concentration at 50% (IC50 ± S.E.). Nonlinear regression analysis (curve fitting).

Figure 6.

Cytotoxicity assesment of the hydroethanolic extract from the bark of the stem of Virola elongata (HEVe 6.25 - 400 µg/mL) and doxorubicin (Doxo 0.01 – 100 µM) in RAW 264.7 cells stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS 1 µg/mL) for 24 (A), 48 (B), and 72 h (C). Inhibitory concentration at 50% (IC50 ± S.E.). Nonlinear regression analysis (curve fitting).

Figure 7.

Effect of in vitro treatment with hydroethanolic extract from the bark of the stem of Virola elongata (HEVe 1, 5, and 20 µg/mL) and Nω-Nitro-L-arginine-methyl-ester (L-NAME 10 mM) on nitric oxide (NO) concentrations in RAW 264.7 cells stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS 1 μg/mL) for 24 h. Cells in the basal group were treated with DMEM culture medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). One-way ANOVA, followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test, ### p < 0.001 vs. Basal, ***p < 0.001 vs. LPS.

Figure 7.

Effect of in vitro treatment with hydroethanolic extract from the bark of the stem of Virola elongata (HEVe 1, 5, and 20 µg/mL) and Nω-Nitro-L-arginine-methyl-ester (L-NAME 10 mM) on nitric oxide (NO) concentrations in RAW 264.7 cells stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS 1 μg/mL) for 24 h. Cells in the basal group were treated with DMEM culture medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). One-way ANOVA, followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test, ### p < 0.001 vs. Basal, ***p < 0.001 vs. LPS.

Figure 8.

Effect of in vitro treatment with hydroethanolic extract from the inner stem bark of Virola elongata (HEVe 1, 5, and 20 µg/mL) and dexamethasone (Dexa 10 mM) on the concentration of the cytokines (A) TNF-α and (B) IL-1β in LPS (1 µg/mL) stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Cells in the basal group were treated only with DMEM culture medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). One-way ANOVA, followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test, *p < 0.05 vs. LPS, **p < 0.01 vs. LPS, ***p < 0.001 vs. LPS, ### p < 0.001 vs. Basal.

Figure 8.

Effect of in vitro treatment with hydroethanolic extract from the inner stem bark of Virola elongata (HEVe 1, 5, and 20 µg/mL) and dexamethasone (Dexa 10 mM) on the concentration of the cytokines (A) TNF-α and (B) IL-1β in LPS (1 µg/mL) stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Cells in the basal group were treated only with DMEM culture medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). One-way ANOVA, followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test, *p < 0.05 vs. LPS, **p < 0.01 vs. LPS, ***p < 0.001 vs. LPS, ### p < 0.001 vs. Basal.

Figure 9.

Effect of in vitro treatment with hydroethanolic extract from the inner stem bark of Virola elongata (HEVe 1, 5, and 20 µg/mL) and dexamethasone (Dexa 10 mM) on the concentration of the cytokine IL-13 in LPS (1 µg/mL) stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Cells in the basal group were treated only with DMEM culture medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). One-way ANOVA, followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test, *** p < 0.001 vs. LPS, ### p < 0.001 vs. Basal.

Figure 9.

Effect of in vitro treatment with hydroethanolic extract from the inner stem bark of Virola elongata (HEVe 1, 5, and 20 µg/mL) and dexamethasone (Dexa 10 mM) on the concentration of the cytokine IL-13 in LPS (1 µg/mL) stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Cells in the basal group were treated only with DMEM culture medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). One-way ANOVA, followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test, *** p < 0.001 vs. LPS, ### p < 0.001 vs. Basal.

Table 1.

Compounds identified through fragmentation pattern analysis obtained both by UHPLC-ESI-IT- and by DFI-ESI- IT-MSn in the hydroethanolic extract of Virola elongata inner stem bark.

Table 1.

Compounds identified through fragmentation pattern analysis obtained both by UHPLC-ESI-IT- and by DFI-ESI- IT-MSn in the hydroethanolic extract of Virola elongata inner stem bark.

| N° |

Rt (min) |

[M-H]-

|

MS/MS |

Compound (Molecular formula) |

Reference |

| 1 |

6.02 |

191 |

173, 127 |

Quinic acid (C7H12O6) |

(16) |

| 2 |

9.28 |

277 |

185,183 |

Resveratrol (C14H12O3) |

(25) |

| 3 |

12.98 |

399 |

321,295,183 |

3′,4′-dimethoxy-3,4-methylenedioxy-6 7′,8 8′-neolignan (C21H24O6) |

(16) |

| 4 |

29.45 |

447 |

301 |

Quercetin (C15H10O7) |

(26) |

| 5 |

30.60 |

577 |

559,451, 425,407, 289 |

Catechin dimer (C30H24O12) |

(27) |

| 6 |

30.95 |

595 |

577,505,475,415,355 |

Diglycosyl-flavonoid (C-glycoside) (C26H28O16) |

(16) |

| 7 |

40.74 |

865 |

|

Catechin trimer (C45H38O18) |

(27) |

| 8 |

45.52 |

1153 |

576 |

Catechin tetramer (C60H50O24) |

(27) |

| 9 |

53.27 |

1441 |

720 |

Catechin pentamer (C75H62O30) |

(27) |