Submitted:

22 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Halodule uninervis Leaves and Powder Preparation

2.2. Preparation of Halodule uninervis Ethanolic Extract (HUE)

2.3. Cell Culture

2.4. Cell Viability Assay

2.5. Whole-Cell Extracts and Western Blotting

2.6. Real-Time PCR

| COX-2 Forward | 5′-GATACTCAGGCAGAGATGATCTACCC-3′ |

| COX-2 Reverse | 5′-AGACCAGGCACCAGACCAAAGA-3′ |

| TNF-α Forward | 5′-GTAGCCCACGTCGTAGCAAACCAC-3′ |

| TNF-α Reverse | 5′-GGTACAACCCATCGGCTGGCAC-3′ |

| IL-6 Forward | 5′-CCTCTCTGCAAGAGACTTCCATCCA-3′ |

| IL-6 Reverse | 5′-TCCTCTGTGAAGTCTCCTCTCCGG-3′ |

2.7. Trans-Well Migration Assay

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

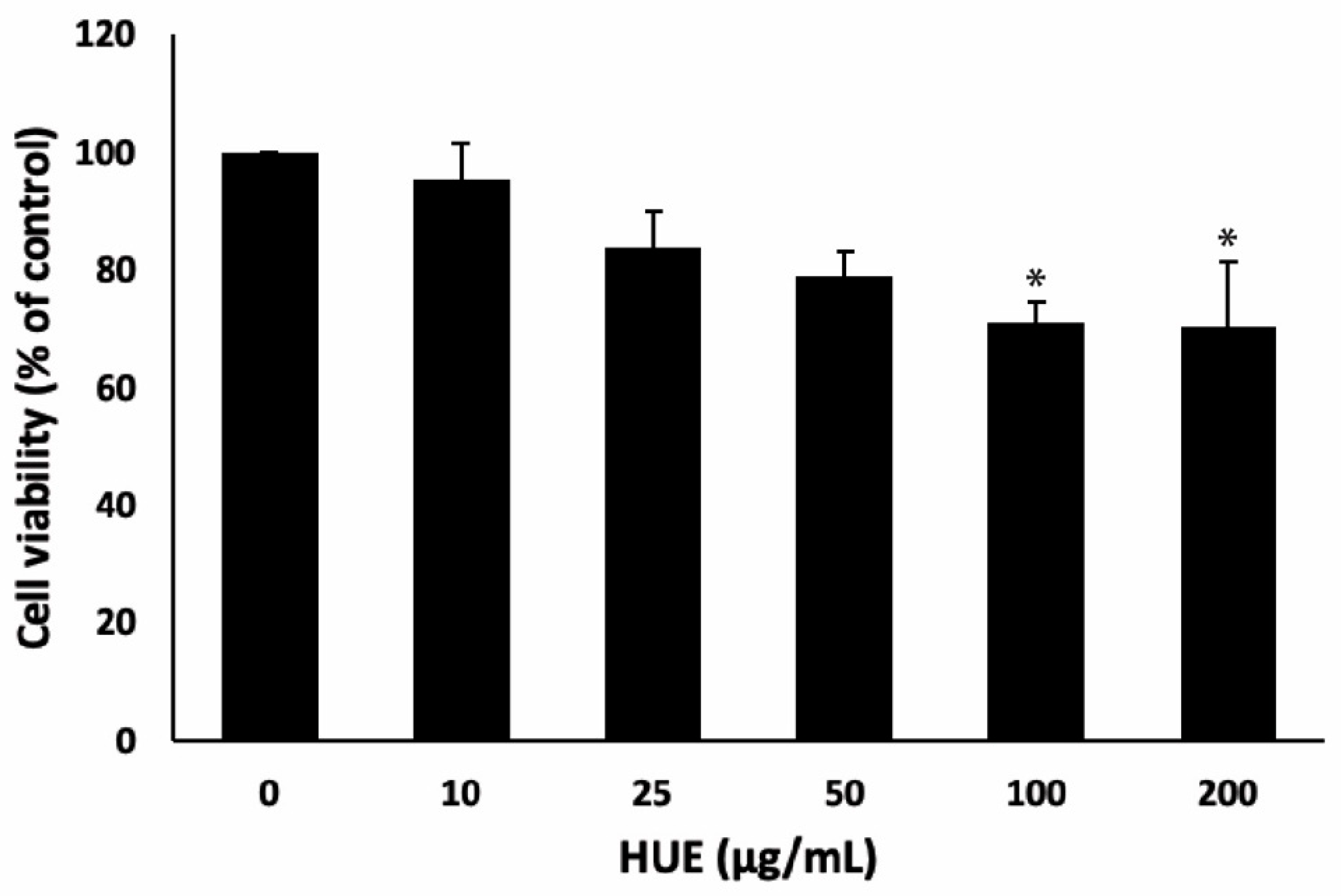

3.1. Effects of HUE on RAW 264.7 Cell Viability

3.2. HUE Decreases Levels of COX-2 and iNOS in LPS-Stimulated RAW 264.7 Cells

3.3. HUE Reduces TNF-α and IL-6 Cytokines mRNA Expression Levels in LPS-Stimulated RAW 264.7 Cells

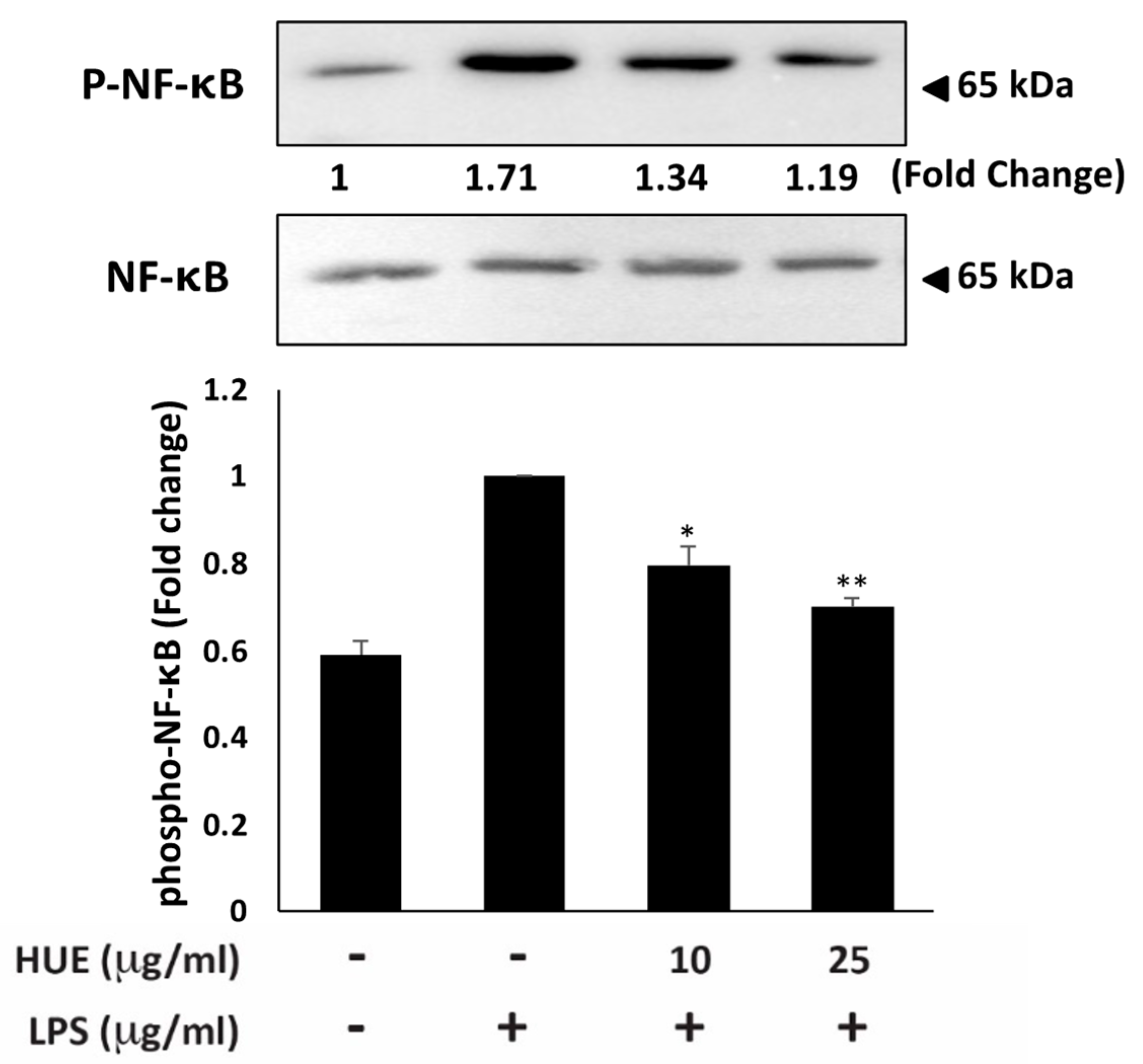

3.4. HUE Inhibits the Phosphorylation of NF-κB in LPS-Stimulated RAW 264.7 Cells

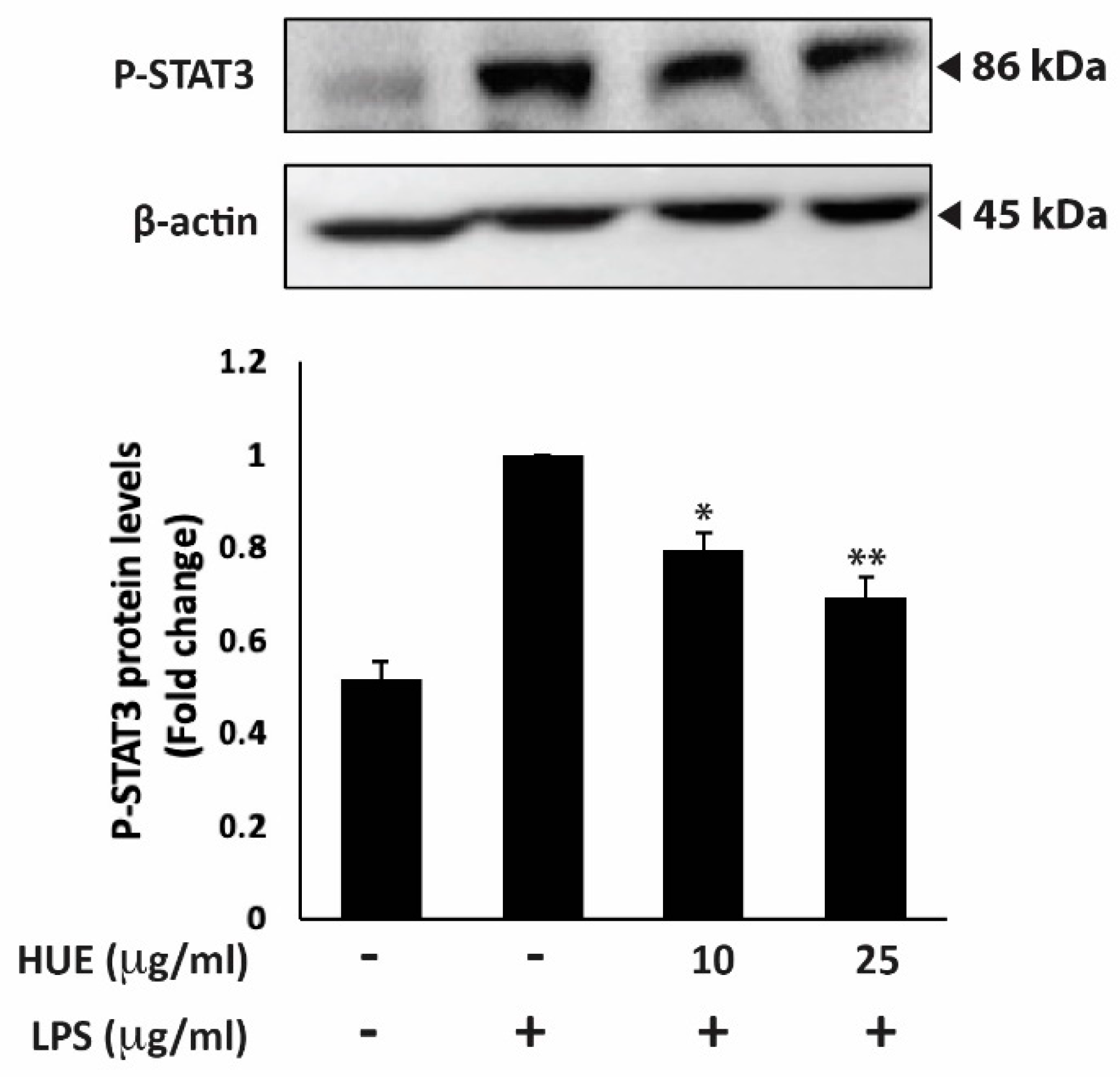

3.5. HUE Inhibits the STAT3 Pathway in LPS-Stimulated RAW 264.7 Cells

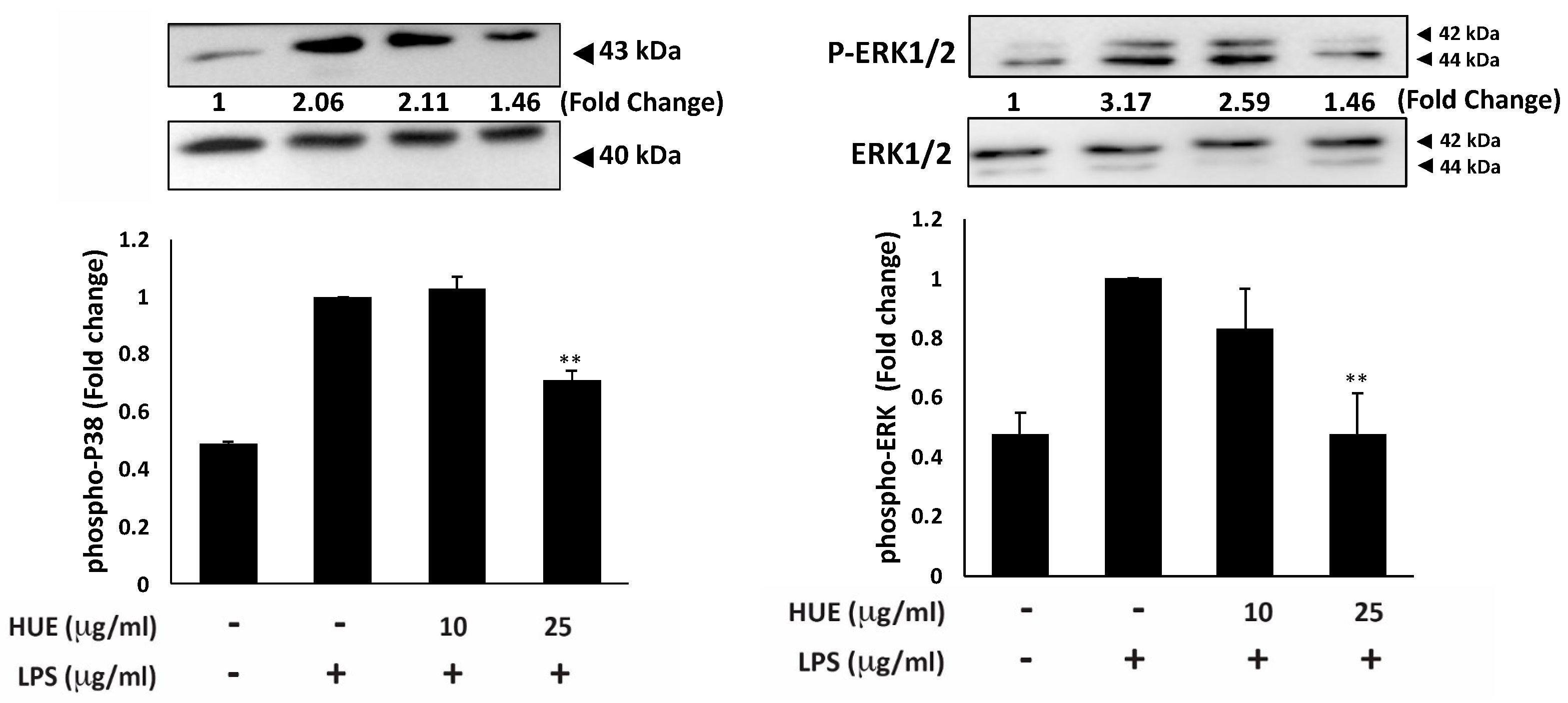

3.6. HUE Inhibits the MAPKs Pathway in LPS-Stimulated RAW 264.7 Cells

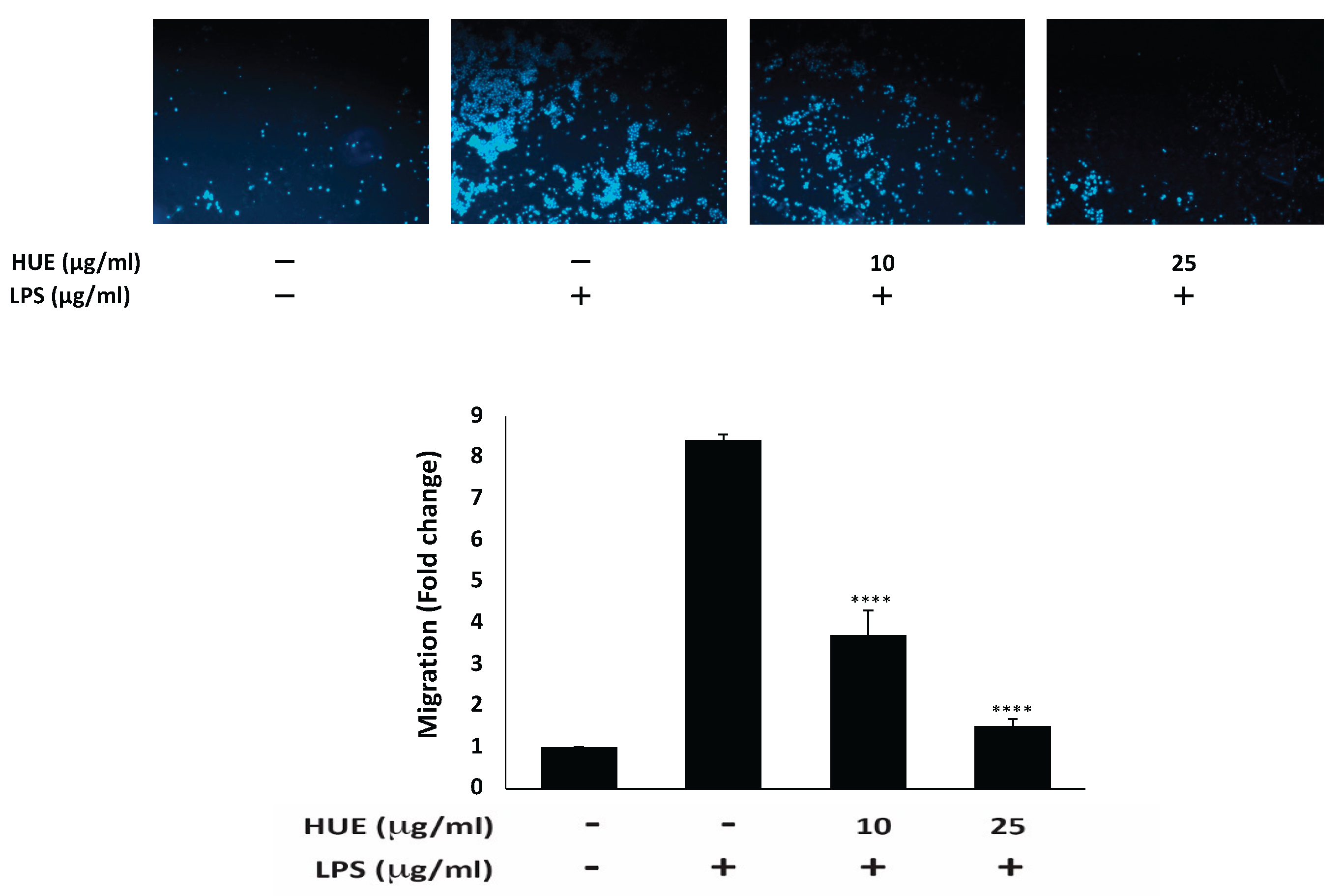

3.7. HUE Inhibits the Cellular Migration of LPS-Stimulated RAW 264.7 Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Netea, M.G. , et al., A guiding map for inflammation. Nature immunology, 2017. 18(8): p. 826-831.

- Rather, L.J. , Disturbance of function (functio laesa): the legendary fifth cardinal sign of inflammation, added by Galen to the four cardinal signs of Celsus. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 1971. 47(3): p. 303.

- Luster, A.D., R. Alon, and U.H. von Andrian, Immune cell migration in inflammation: present and future therapeutic targets. Nature immunology, 2005. 6(12): p. 1182-1190.

- Roh, J.S. and D.H. Sohn, Damage-associated molecular patterns in inflammatory diseases. Immune network, 2018. 18(4).

- Liu, T. , et al., NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal transduction and targeted therapy, 2017. 2(1): p. 1-9.

- Zhang, J.-M. and J. An, Cytokines, inflammation, and pain. International anesthesiology clinics, 2007. 45(2): p. 27-37.

- Feghali, C.A. and T.M. Wright, Cytokines in acute and chronic inflammation. Front Biosci, 1997. 2(1): p. d12-d26.

- Pan, M.-H. , et al., Acacetin suppressed LPS-induced up-expression of iNOS and COX-2 in murine macrophages and TPA-induced tumor promotion in mice. Biochemical pharmacology, 2006. 72(10): p. 1293-1303.

- Zamora, R., Y. Vodovotz, and T.R. Billiar, Inducible nitric oxide synthase and inflammatory diseases. Molecular medicine, 2000. 6: p. 347-373.

- Simon, L.S. , Role and regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 during inflammation. The American journal of medicine, 1999. 106(5): p. 37S-42S.

- Xia, T. , et al., Advances in the role of STAT3 in macrophage polarization. Frontiers in immunology, 2023. 14: p. 1160719.

- Hannoodee, S. and D.N. Nasuruddin, Acute inflammatory response. 2020.

- Pahwa, R., A. Goyal, and I. Jialal, Chronic inflammation. 2018.

- Bindu, S., S. Mazumder, and U. Bandyopadhyay, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and organ damage: A current perspective. Biochemical pharmacology, 2020. 180: p. 114147.

- Patrignani, P. and C. Patrono, Cyclooxygenase inhibitors: from pharmacology to clinical read-outs. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids, 2015. 1851(4): p. 422-432.

- Nunes, C.d.R. , et al., Plants as Sources of Anti-Inflammatory Agents. Molecules, 2020. 25(16): p. 3726.

- Tasneem, S. , et al., Molecular pharmacology of inflammation: Medicinal plants as anti-inflammatory agents. Pharmacological research, 2019. 139: p. 126-140.

- Potouroglou, M. , et al., Measuring the role of seagrasses in regulating sediment surface elevation. Scientific reports, 2017. 7(1): p. 11917.

- Ondiviela, B. , et al., The role of seagrasses in coastal protection in a changing climate. Coastal Engineering, 2014. 87: p. 158-168.

- Nagelkerken, I. , et al., Importance of mangroves, seagrass beds and the shallow coral reef as a nursery for important coral reef fishes, using a visual census technique. Estuarine, coastal and shelf science, 2000. 51(1): p. 31-44.

- Kim, D.H. , et al., Nutritional and bioactive potential of seagrasses: A review. South African Journal of Botany, 2021. 137: p. 216-227.

- Baehaki, A. , et al., Antidiabetic Activity with N-Hexane, Ethyl-Acetate and Ethanol Extract of Halodule uninervis Seagrass. Pharmacognosy Journal, 2020. 12(4).

- Karthikeyan, R. and M. Sundarapandian, Antidiabetic activity of methanolic extract of Halodule uninervis in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, 2017. 9(10): p. 1864-1868.

- Supriadi, A., A. Baehaki, and M.C. Pratama, Antibacterial activity of methanol extract from seagrass of Halodule uninervis in the coastal of Lampung. Pharm Lett, 2016. 8: p. 77-79.

- Wehbe, N. , et al., The Antioxidant Potential and Anticancer Activity of Halodule uninervis Ethanolic Extract against Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Antioxidants, 2024. 13(6): p. 726.

- Ghandourah, M. , et al., Fatty Acids and Other Chemical Compositions of Some Seagrasses Collected from the Saudi Red Sea with Potential of Antioxidant and Anticancer Agents. Thalassas: An International Journal of Marine Sciences, 2021. 37: p. 13-22.

- Baehaki, A., A. Supriadi, and M.C. Pratama, Antioxidant Activity of Methanol Extract of Halodule uninervis Seagrass from the Coastal of Lampung, Indonesia. RESEARCH JOURNAL OF PHARMACEUTICAL BIOLOGICAL AND CHEMICAL SCIENCES, 2016. 7(3): p. 1173-1177.

- Ramah, S. , et al., Prophylactic antioxidants and phenolics of seagrass and seaweed species: A seasonal variation study in a Southern Indian Ocean Island, Mauritius. Internet Journal of Medical Update-EJOURNAL, 2014. 9(1): p. 27-37.

- Parthasarathi, P. , et al., Phytochemical screening and in-vitro anticancer activity of ethyl acetate fraction of Seagrass Halodule uninervis from Mandapam Coastal Region Rameswaram Gulf of Mannar India. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Drug Research, 2021. 13(6): p. 677-684.

- Kawahara, K. , et al., Prostaglandin E2-induced inflammation: Relevance of prostaglandin E receptors. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids, 2015. 1851(4): p. 414-421.

- Korhonen, R. , et al., Nitric oxide production and signaling in inflammation. Current Drug Targets-Inflammation & Allergy, 2005. 4(4): p. 471-479.

- Parameswaran, N. and S. Patial, Tumor necrosis factor-α signaling in macrophages. Critical Reviews™ in Eukaryotic Gene Expression, 2010. 20(2).

- Tanaka, T., M. Narazaki, and T. Kishimoto, IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology, 2014. 6(10): p. a016295.

- Kasembeli, M.M. , et al., Contribution of STAT3 to inflammatory and fibrotic diseases and prospects for its targeting for treatment. International journal of molecular sciences, 2018. 19(8): p. 2299.

- Cargnello, M. and P.P. Roux, Activation and function of the MAPKs and their substrates, the MAPK-activated protein kinases. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews, 2011. 75(1): p. 50-83.

- Kaminska, B. , MAPK signalling pathways as molecular targets for anti-inflammatory therapy—from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic benefits. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Proteins and Proteomics, 2005. 1754(1-2): p. 253-262.

- Choudhari, A.S. , et al., Phytochemicals in cancer treatment: From preclinical studies to clinical practice. Frontiers in pharmacology, 2020. 10: p. 1614.

- Nisar, A. , et al., Phytochemicals in the treatment of inflammation-associated diseases: the journey from preclinical trials to clinical practice. Frontiers in pharmacology, 2023. 14: p. 1177050.

- Ginwala, R. , et al., Potential role of flavonoids in treating chronic inflammatory diseases with a special focus on the anti-inflammatory activity of apigenin. Antioxidants, 2019. 8(2): p. 35.

- Kadioglu, O. , et al., Kaempferol is an anti-inflammatory compound with activity towards NF-κB pathway proteins. Anticancer research, 2015. 35(5): p. 2645-2650.

- Wang, X.-L. , et al., The effects of resveratrol on inflammation and oxidative stress in a rat model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Molecules, 2017. 22(9): p. 1529.

- Page, M.J., D. B. Kell, and E. Pretorius, The role of lipopolysaccharide-induced cell signalling in chronic inflammation. Chronic Stress, 2022. 6: p. 24705470221076390.

- Fujihara, M. , et al., Molecular mechanisms of macrophage activation and deactivation by lipopolysaccharide: roles of the receptor complex. Pharmacology & therapeutics, 2003. 100(2): p. 171-194.

- Kawai, T. and S. Akira, The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nature immunology, 2010. 11(5): p. 373-384.

- Sheppe, A.E. , et al., PGE2 augments inflammasome activation and M1 polarization in macrophages infected with Salmonella Typhimurium and Yersinia enterocolitica. Frontiers in microbiology, 2018. 9: p. 2447.

- Williams, J.A. and E. Shacter, Regulation of macrophage cytokine production by prostaglandin E2: distinct roles of cyclooxygenase-1 and-2. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1997. 272(41): p. 25693-25699.

- Suriyaprom, S. , et al., Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity on LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophage cells of white mulberry (Morus alba L.) leaf extracts. Molecules, 2023. 28(11): p. 4395.

- Duan, X. , et al., Chemical component and in vitro protective effects of Matricaria chamomilla (L.) against lipopolysaccharide insult. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 2022. 296: p. 115471.

- Nguyen, T.Q. , et al., Anti-inflammatory effects of Lasia spinosa leaf extract in lipopolysaccharide-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2020. 21(10): p. 3439.

- Begum, S.A. , et al., Halodule pinifolia (Seagrass) attenuated lipopolysaccharide-, carrageenan-, and crystal-induced secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines: mechanism and chemistry. Inflammopharmacology, 2021. 29: p. 253-267.

- Kany, S., J. T. Vollrath, and B. Relja, Cytokines in inflammatory disease. International journal of molecular sciences, 2019. 20(23): p. 6008.

- Okuda-Hanafusa, C. , et al., Turmeronol A and turmeronol B from Curcuma longa prevent inflammatory mediator production by lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW264. 7 macrophages, partially via reduced NF-κB signaling. Food & function, 2019. 10(9): p. 5779-5788.

- Yu, M.-H. , et al., Suppression of LPS-induced inflammatory activities by Rosmarinus officinalis L. Food Chemistry, 2013. 136(2): p. 1047-1054.

- Sharif, O. , et al., Transcriptional profiling of the LPS induced NF-κB response in macrophages. BMC immunology, 2007. 8: p. 1-17.

- Tak, P.P. and G.S. Firestein, NF-κB: a key role in inflammatory diseases. The Journal of clinical investigation, 2001. 107(1): p. 7-11.

- Christian, F., E. L. Smith, and R.J. Carmody, The regulation of NF-κB subunits by phosphorylation. Cells, 2016. 5(1): p. 12.

- Naumann, M. and C. Scheidereit, Activation of NF-kappa B in vivo is regulated by multiple phosphorylations. The EMBO journal, 1994. 13(19): p. 4597-4607.

- Moreno, R. , et al., Specification of the NF-κB transcriptional response by p65 phosphorylation and TNF-induced nuclear translocation of IKKε. Nucleic acids research, 2010. 38(18): p. 6029-6044.

- Vasarri, M. , et al., Anti-inflammatory properties of the marine plant Posidonia oceanica (L.) Delile. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 2020. 247: p. 112252.

- Zhao, J. , et al., Protective effect of suppressing STAT3 activity in LPS-induced acute lung injury. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology, 2016. 311(5): p. L868-L880.

- Yaqin, Z. , et al., Resveratrol alleviates inflammatory bowel disease by inhibiting JAK2/STAT3 pathway activity via the reduction of O-GlcNAcylation of STAT3 in intestinal epithelial cells. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2024. 484: p. 116882.

- Liu, Y. , et al., 6-Gingerol attenuates microglia-mediated neuroinflammation and ischemic brain injuries through Akt-mTOR-STAT3 signaling pathway. European Journal of Pharmacology, 2020. 883: p. 173294.

- Li, L. , et al., Echinacoside alleviated LPS-induced cell apoptosis and inflammation in rat intestine epithelial cells by inhibiting the mTOR/STAT3 pathway. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 2018. 104: p. 622-628.

- Liu, L. , et al., Curcumin ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium-induced experimental colitis by blocking STAT3 signaling pathway. International immunopharmacology, 2013. 17(2): p. 314-320.

- An, H.-J. , et al., STAT3/NF-κB decoy oligodeoxynucleotides inhibit atherosclerosis through regulation of the STAT/NF-κB signaling pathway in a mouse model of atherosclerosis. International Journal of Molecular Medicine, 2023. 51(5): p. 1-11.

- Liu, X. , et al., LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokine expression in human airway epithelial cells and macrophages via NF-κB, STAT3 or AP-1 activation. Molecular medicine reports, 2018. 17(4): p. 5484-5491.

- Basu, A. , et al., STAT3 and NF-κB are common targets for kaempferol-mediated attenuation of COX-2 expression in IL-6-induced macrophages and carrageenan-induced mouse paw edema. Biochemistry and biophysics reports, 2017. 12: p. 54-61.

- Seo, Y.-J. , et al., Isocyperol, isolated from the rhizomes of Cyperus rotundus, inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory responses via suppression of the NF-κB and STAT3 pathways and ROS stress in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. International immunopharmacology, 2016. 38: p. 61-69.

- Li, X. , et al., Sorafenib inhibits LPS-induced inflammation by regulating Lyn-MAPK-NF-kB/AP-1 pathway and TLR4 expression. Cell Death Discovery, 2022. 8(1): p. 281.

- Han, Y.-H. , et al., Anti-inflammatory effect of hispidin on LPS induced macrophage inflammation through MAPK and JAK1/STAT3 signaling pathways. Applied Biological Chemistry, 2020. 63: p. 1-9.

- Linghu, K.-G. , et al., Comprehensive comparison on the anti-inflammatory effects of three species of Sigesbeckia plants based on NF-κB and MAPKs signal pathways in vitro. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 2020. 250: p. 112530.

- Li, R., P. Hong, and X. Zheng, β-Carotene attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation via inhibition of the NF-κB, JAK2/STAT3 and JNK/p38 MAPK signaling pathways in macrophages. Animal Science Journal, 2019. 90(1): p. 140-148.

- Yu, Q. , et al., Resokaempferol-mediated anti-inflammatory effects on activated macrophages via the inhibition of JAK2/STAT3, NF-κB and JNK/p38 MAPK signaling pathways. International immunopharmacology, 2016. 38: p. 104-114.

- Guak, H. and C.M. Krawczyk, Implications of cellular metabolism for immune cell migration. Immunology, 2020. 161(3): p. 200-208.

- Cui, S. , et al., Quercetin inhibits LPS-induced macrophage migration by suppressing the iNOS/FAK/paxillin pathway and modulating the cytoskeleton. Cell Adhesion & Migration, 2019. 13(1): p. 1-12.

- Chen, Y.-C. , et al., Morus alba and active compound oxyresveratrol exert anti-inflammatory activity via inhibition of leukocyte migration involving MEK/ERK signaling. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2013. 13: p. 1-10.

- Tripathi, S., D. Bruch, and D.S. Kittur, Ginger extract inhibits LPS induced macrophage activation and function. BMC complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2008. 8: p. 1-7.

- Charalabopoulos, A. , et al., Apigenin exerts anti-inflammatory effects in an experimental model of acute pancreatitis by down-regulating TNF-α. in vivo, 2019. 33(4): p. 1133-1141.

- Ai, X.-Y. , et al., Apigenin inhibits colonic inflammation and tumorigenesis by suppressing STAT3-NF-κB signaling. Oncotarget, 2017. 8(59): p. 100216.

- Malik, S. , et al., Apigenin ameliorates streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy in rats via MAPK-NF-κB-TNF-α and TGF-β1-MAPK-fibronectin pathways. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology, 2017. 313(2): p. F414-F422.

- Wang, J. , et al., Anti-inflammatory effects of apigenin in lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory in acute lung injury by suppressing COX-2 and NF-kB pathway. Inflammation, 2014. 37: p. 2085-2090.

- Zhang, X. , et al., Flavonoid apigenin inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response through multiple mechanisms in macrophages. PloS one, 2014. 9(9): p. e107072.

- Hämäläinen, M. , et al., Anti-inflammatory effects of flavonoids: Genistein, kaempferol, quercetin, and daidzein inhibit STAT-1 and NF-κB activations, whereas flavone, isorhamnetin, naringenin, and pelargonidin inhibit only NF-κB activation along with their inhibitory effect on iNOS expression and NO production in activated macrophages. Mediators of inflammation, 2007. 2007(1): p. 045673.

- García-Mediavilla, V. , et al., The anti-inflammatory flavones quercetin and kaempferol cause inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase, cyclooxygenase-2 and reactive C-protein, and down-regulation of the nuclear factor kappaB pathway in Chang Liver cells. European journal of pharmacology, 2007. 557(2-3): p. 221-229.

- Singh, B. , et al., Protective effect of vanillic acid against diabetes and diabetic nephropathy by attenuating oxidative stress and upregulation of NF-κB, TNF-α and COX-2 proteins in rats. Phytotherapy Research, 2022. 36(3): p. 1338-1352.

- Huang, X. , et al., Vanillic acid attenuates cartilage degeneration by regulating the MAPK and PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathways. European journal of pharmacology, 2019. 859: p. 172481.

- Calixto-Campos, C. , et al., Vanillic acid inhibits inflammatory pain by inhibiting neutrophil recruitment, oxidative stress, cytokine production, and NFκB activation in mice. Journal of natural products, 2015. 78(8): p. 1799-1808.

- Kim, M.-C. , et al., Vanillic acid inhibits inflammatory mediators by suppressing NF-κB in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated mouse peritoneal macrophages. Immunopharmacology and immunotoxicology, 2011. 33(3): p. 525-532.

- Ferreira, J.C. , et al., Baccharin and p-coumaric acid from green propolis mitigate inflammation by modulating the production of cytokines and eicosanoids. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 2021. 278: p. 114255.

- Kheiry, M. , et al., p-Coumaric acid attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced lung inflammation in rats by scavenging ROS production: an in vivo and in vitro study. Inflammation, 2019. 42: p. 1939-1950.

- Zhu, H. , et al., Anti-inflammatory effects of p-coumaric acid, a natural compound of Oldenlandia diffusa, on arthritis model rats. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2018. 2018(1): p. 5198594.

- Pragasam, S.J., V. Venkatesan, and M. Rasool, Immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effect of p-coumaric acid, a common dietary polyphenol on experimental inflammation in rats. Inflammation, 2013. 36: p. 169-176.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).