Submitted:

02 September 2024

Posted:

03 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Relevant Sections

2.1. Theoretical Framework of Evaluation Studies

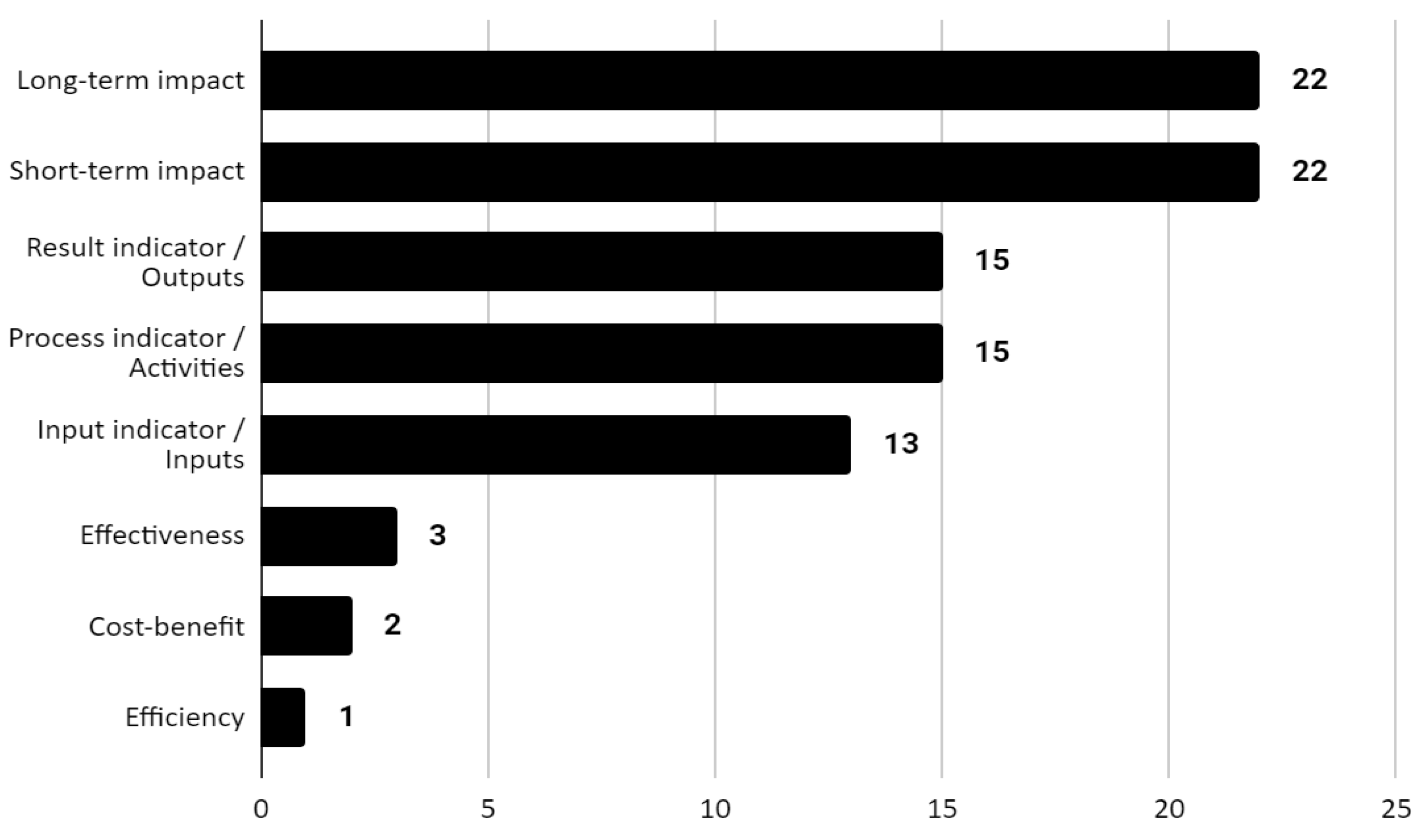

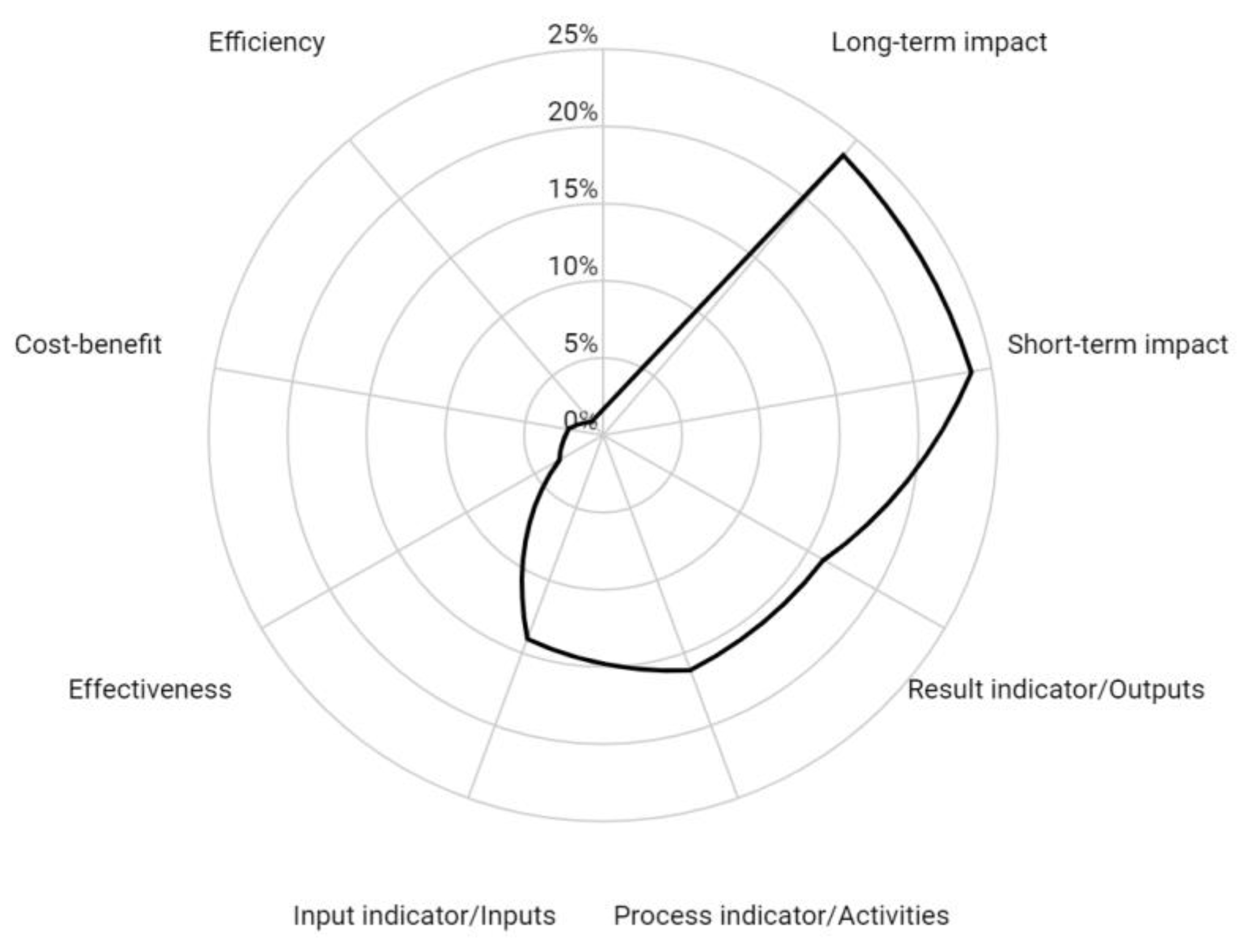

- Input indicator/Inputs: resources that ensure the functioning of food banks, such as food, financial resources, human resources, physical resources and technical resources;

- Process indicator/Activities: actions designed to meet the objectives of a program, such as food collection and redistribution activities, educational activities and also administrative and financial activities;

- Result indicator/Outputs: tangible and intangible products that result from the program's activities, such as donated food and services provided;

- Short-term impact: immediate effects of the organization's products and services, such as improved health conditions of the benefited population, increased consumption of healthy foods, increased supply of fruits and vegetables in social institutions and reduction in the generation of organic waste;

- Long-term impact: higher-level goals to which the project can contribute, such as changes in the political environment - creation of policies to encourage food donations, changes in the corporate environment - new practices to reduce food waste in the food system, improvement of the food security situation of a population.

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

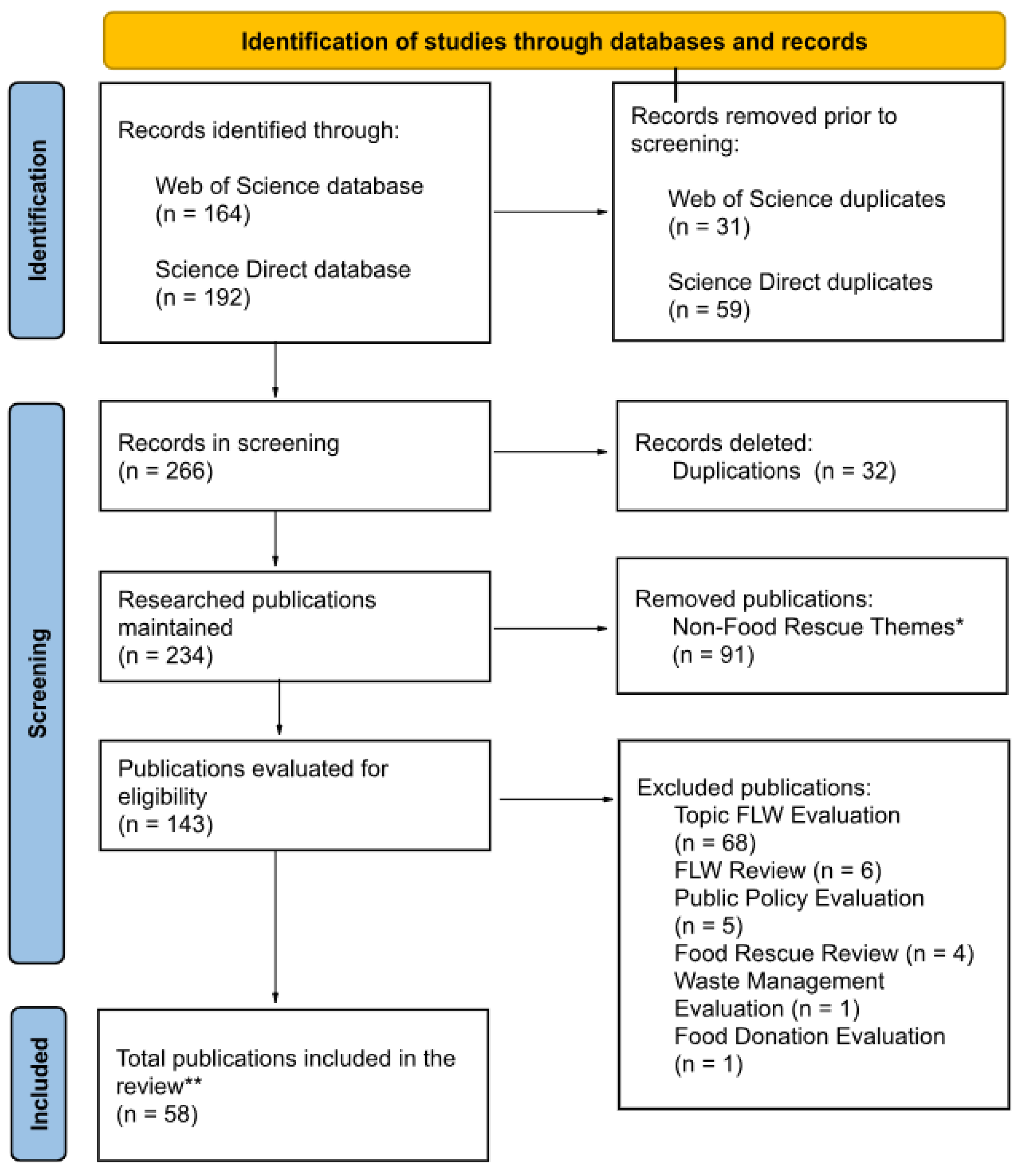

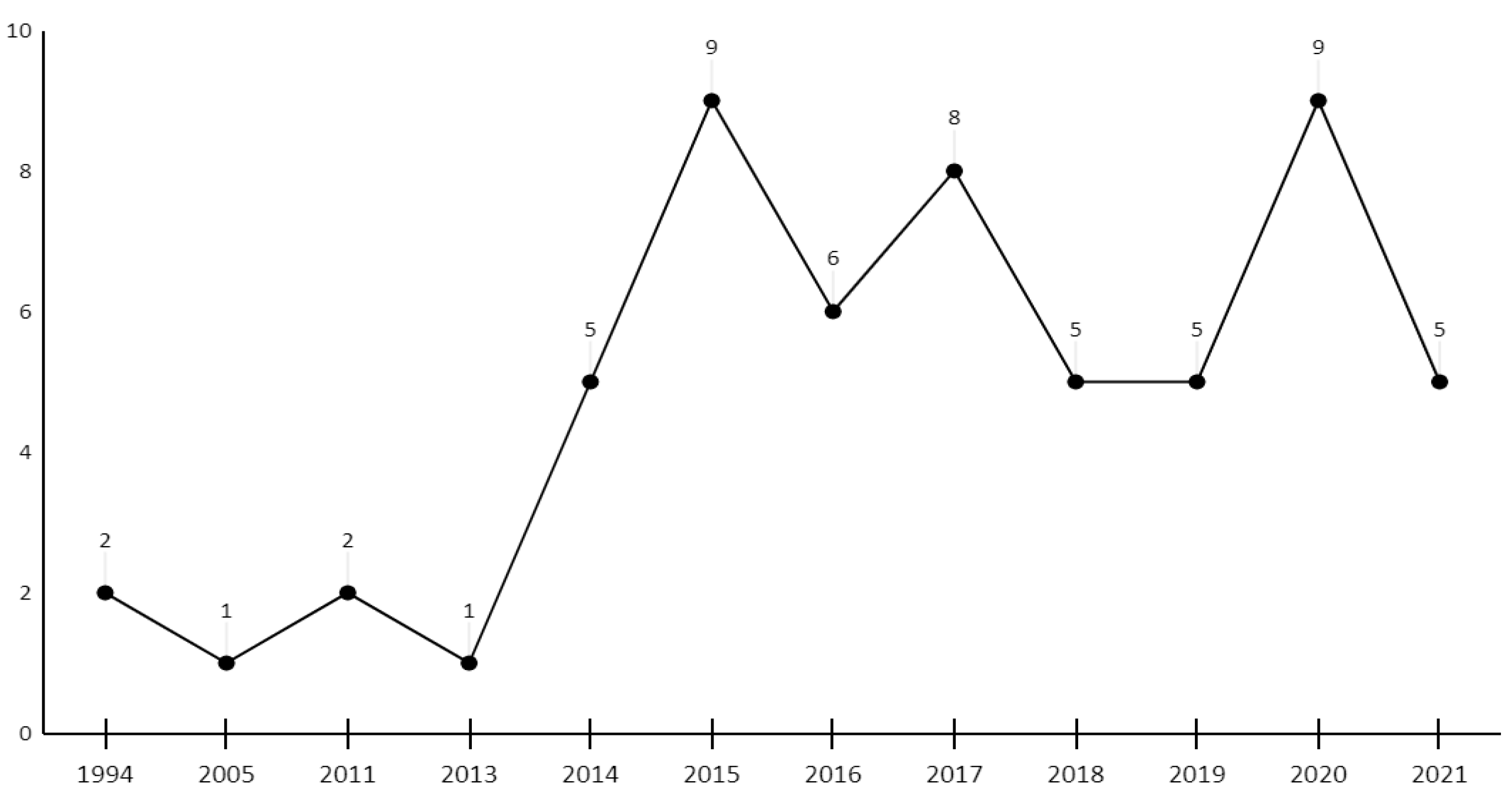

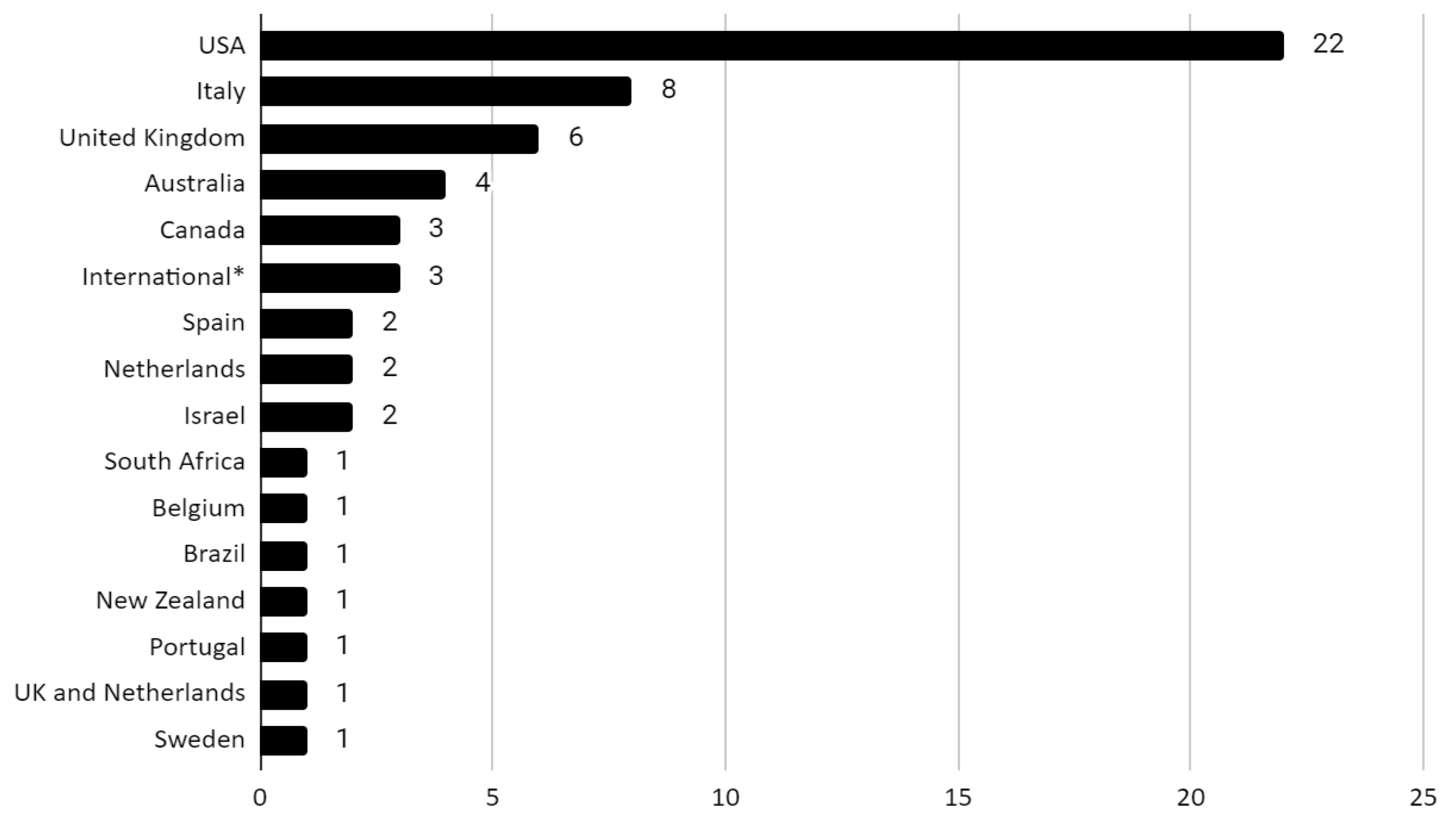

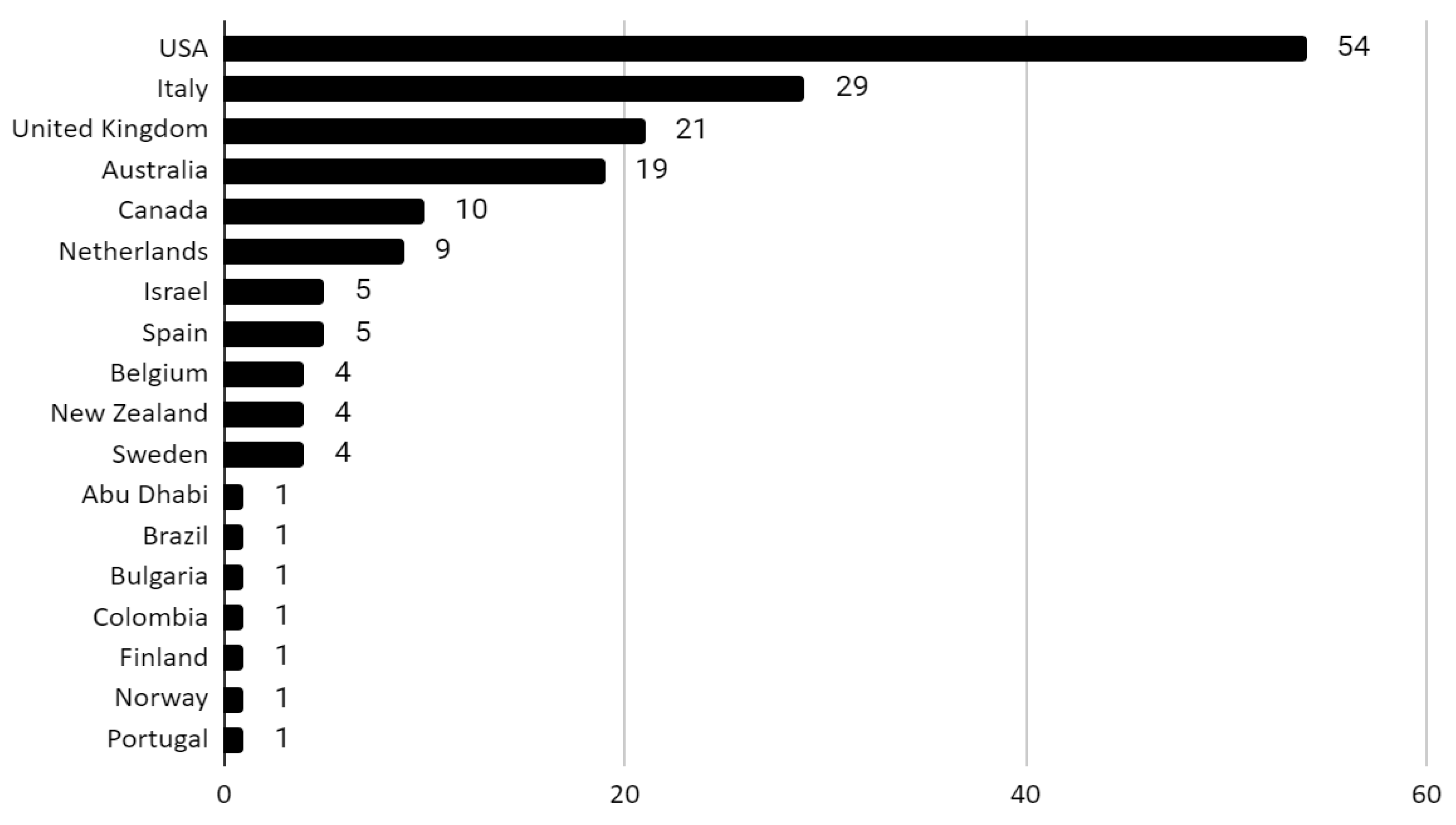

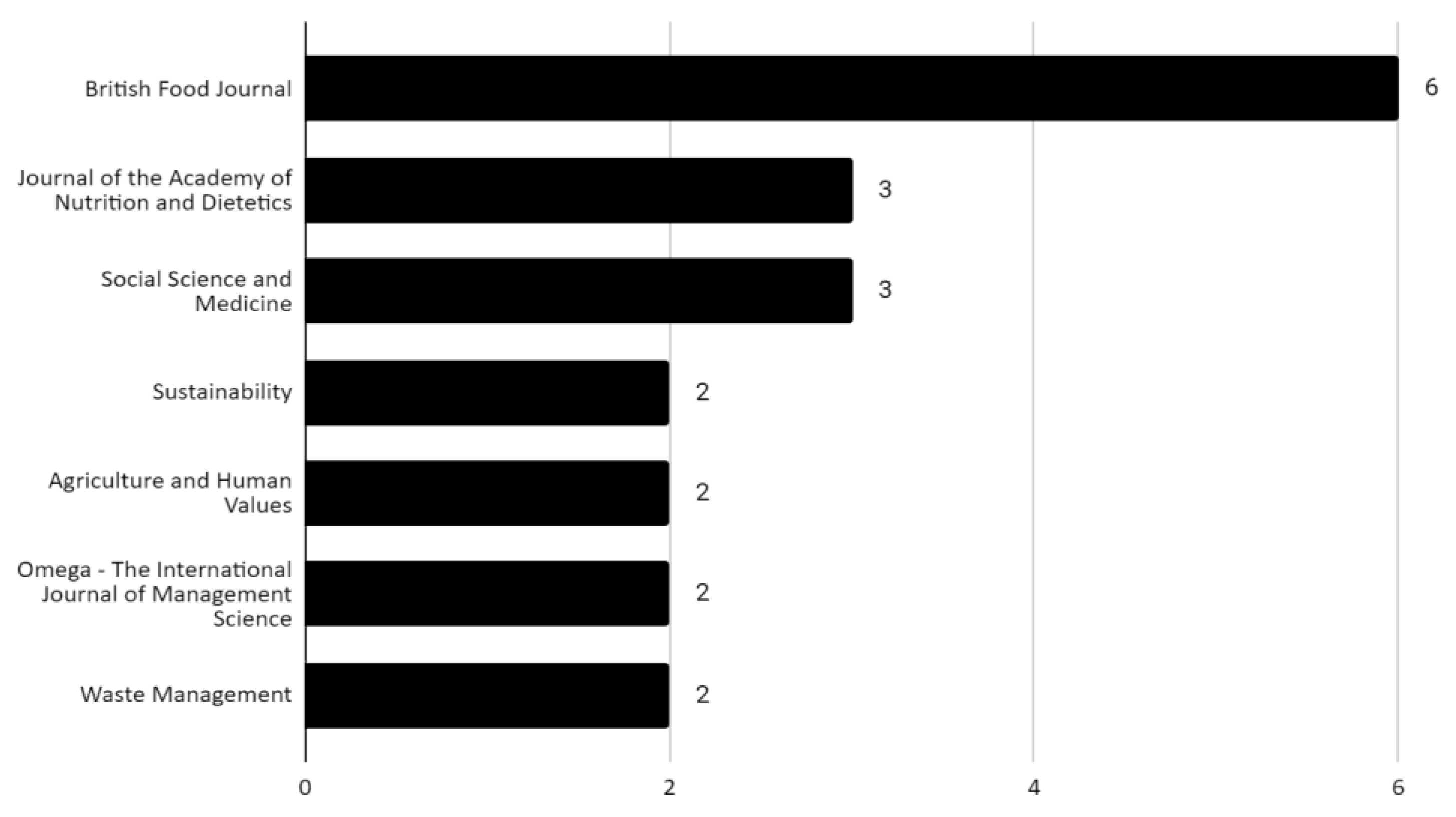

4.1. Selection of Articles

4.2. Selection of Articles

- Long-term impact

| Indicators of long-term impact | Number of cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Policy for reducing Food Loss and Waste | 4 | 18% |

| Corporate social responsibility, corporate image | 4 | 18% |

| National Food Security Policy | 3 | 14% |

| Overcoming social exclusion, social and labor market reintegration | 3 | 14% |

| Relationship between the private, public and civil society sectors | 1 | 5% |

| Potential for social transformation | 1 | 5% |

| Environmental impact | 1 | 5% |

| Potential for environmental, social, economic and political impact | 1 | 5% |

| Building ethical and justice dimensions | 1 | 5% |

| Policy to guarantee the Human Right to Adequate Food | 1 | 5% |

| Creation of social capital in food distribution network | 1 | 5% |

| Relationship between business and community | 1 | 5% |

| Total | 22 | 100% |

- Short-term impact

| Indicators of short-term impact | Number of cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Meeting beneficiaries’ nutritional needs | 6 | 27% |

| Income support for beneficiaries | 3 | 14% |

| Reaching low-income people | 3 | 14% |

| Job generation | 2 | 9% |

| Improvement in users' health | 2 | 9% |

| Knowledge acquired by beneficiaries | 2 | 9% |

| Improvement in the well-being of the elderly | 1 | 5% |

| Perceived benefits, challenges and tensions | 1 | 5% |

| Motivation of volunteers | 1 | 5% |

| Reduction of GHG emissions | 1 | 5% |

| Total | 22 | 100% |

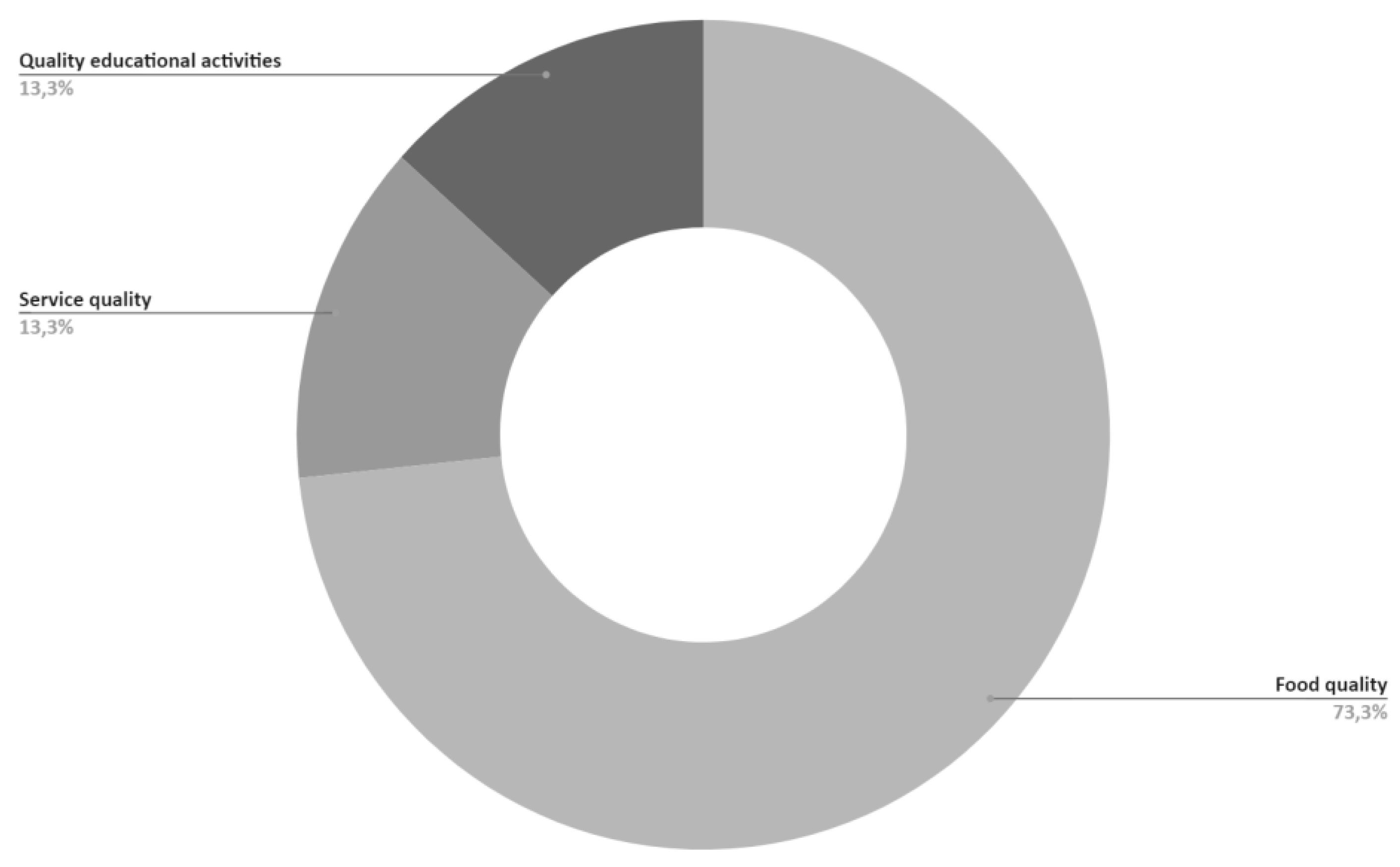

- Result indicators / outputs

| Result indicators/outputs | Number of cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Nutritional quality of donations | 7 | 47% |

| Quality of service provided | 2 | 13% |

| Quantity of donated food | 2 | 13% |

| Quality of educational activities | 2 | 13% |

| Safety of food supplied | 1 | 7% |

| Ability to supply fresh products | 1 | 7% |

| Total | 15 | 100% |

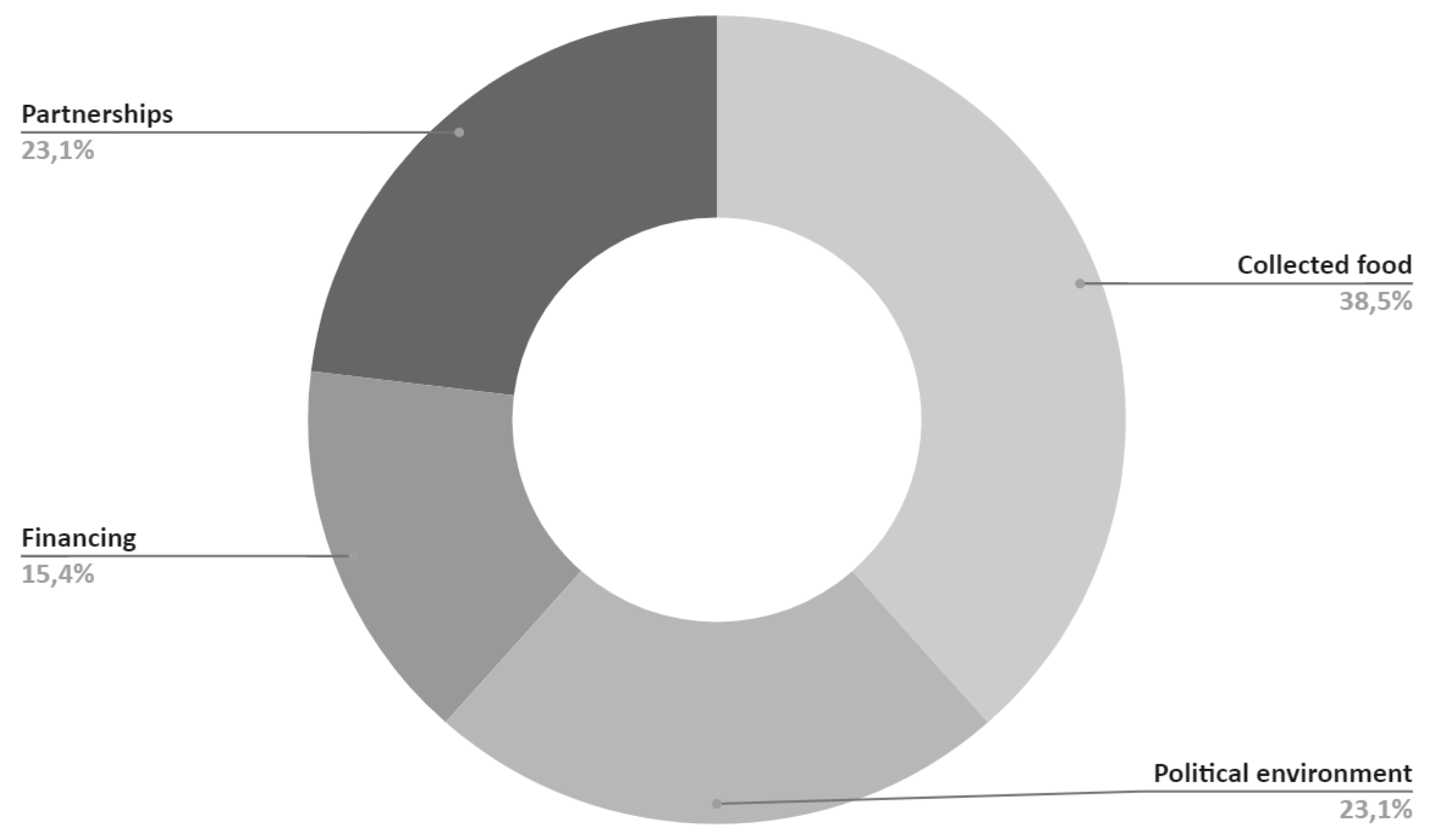

- Input indicator / inputs

| Input indicators / inputs | Number of cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Quantity of food collected | 4 | 31% |

| Public policies for food donation | 3 | 23% |

| Funding of food banks | 2 | 15% |

| Surplus food in industry and restaurants | 2 | 15% |

| Safety of collected food | 1 | 8% |

| Number of partnerships | 1 | 8% |

| Total | 13 | 100% |

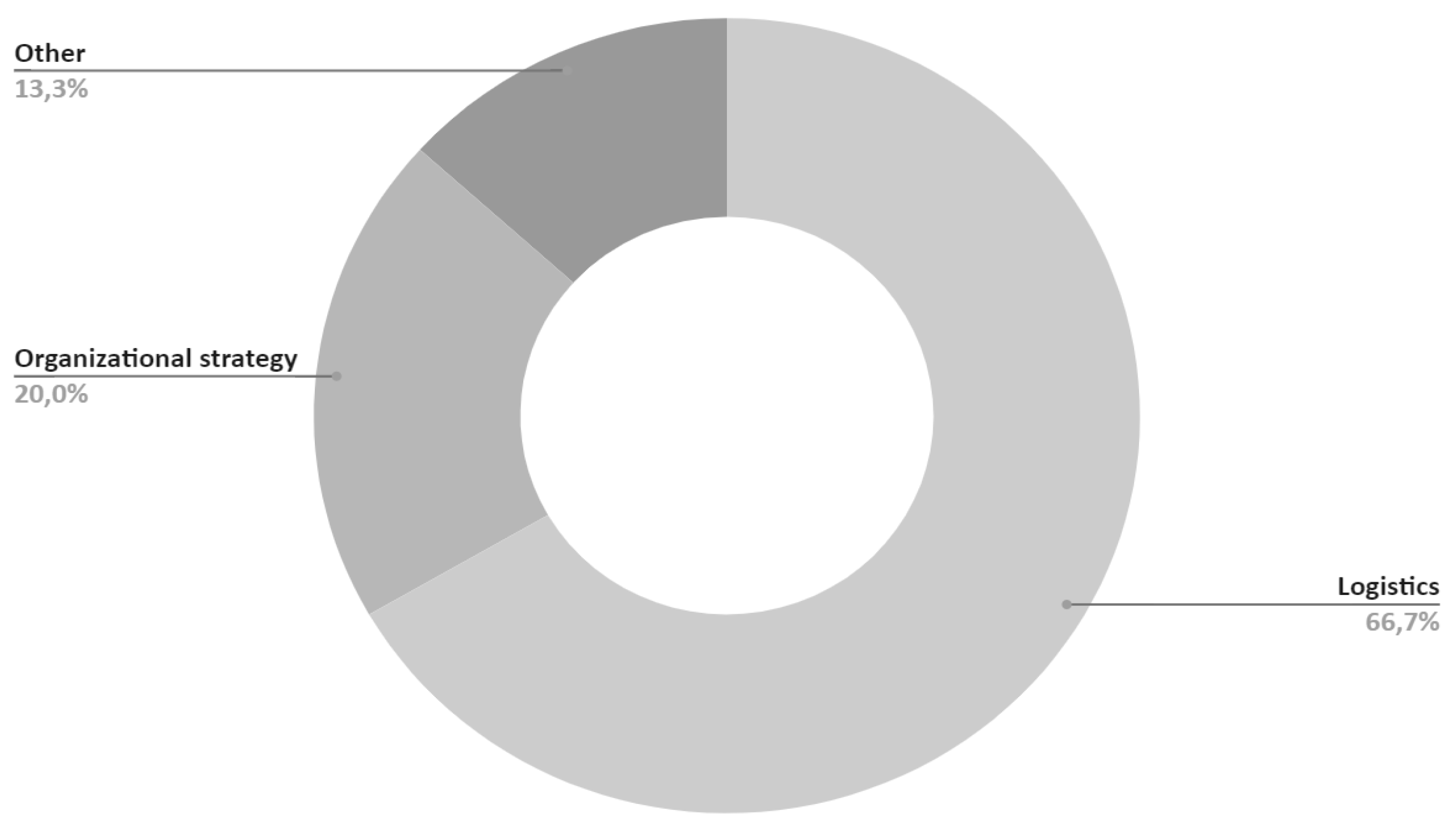

- Process indicator / activities

| Process indicator / activities | Number of cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Food collection and redistribution logistics | 5 | 33% |

| Food collection logistics | 4 | 27% |

| Organizational capacity and strategy | 2 | 13% |

| Safety in the food recovery process | 1 | 7% |

| Food bank management | 1 | 7% |

| Food distribution in digital format | 1 | 7% |

| Environment for volunteering | 1 | 7% |

| Total | 15 | 100% |

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

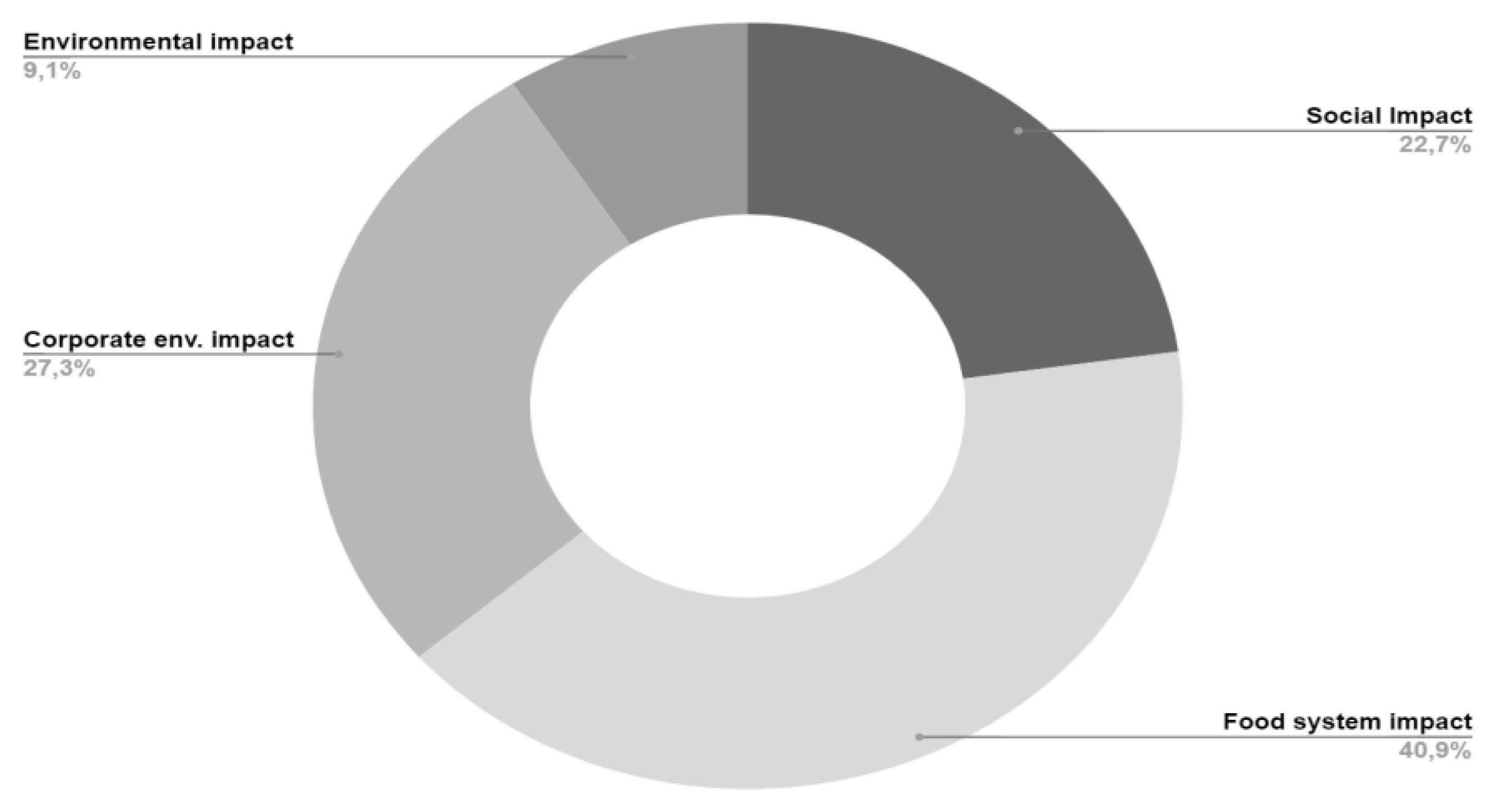

| 1 |

Impact on the Food System: Policy to reduce food losses and waste; Policy on food and nutritional security; Policy for ensuring the Human Right to Adequate Food; Creation of social capital in food distribution networks.

Impact on the Corporate Environment: Corporate social responsibility, corporate image; Relationship between the private and public sectors and civil society; Relationship between companies and the community.

Social Impact: Overcoming social exclusion, social and labor market reintegration; Potential for social transformation; Construction of ethical and justice dimensions.

Environmental Impact: Environmental impact; Potential for environmental, social, economic and political impact.

|

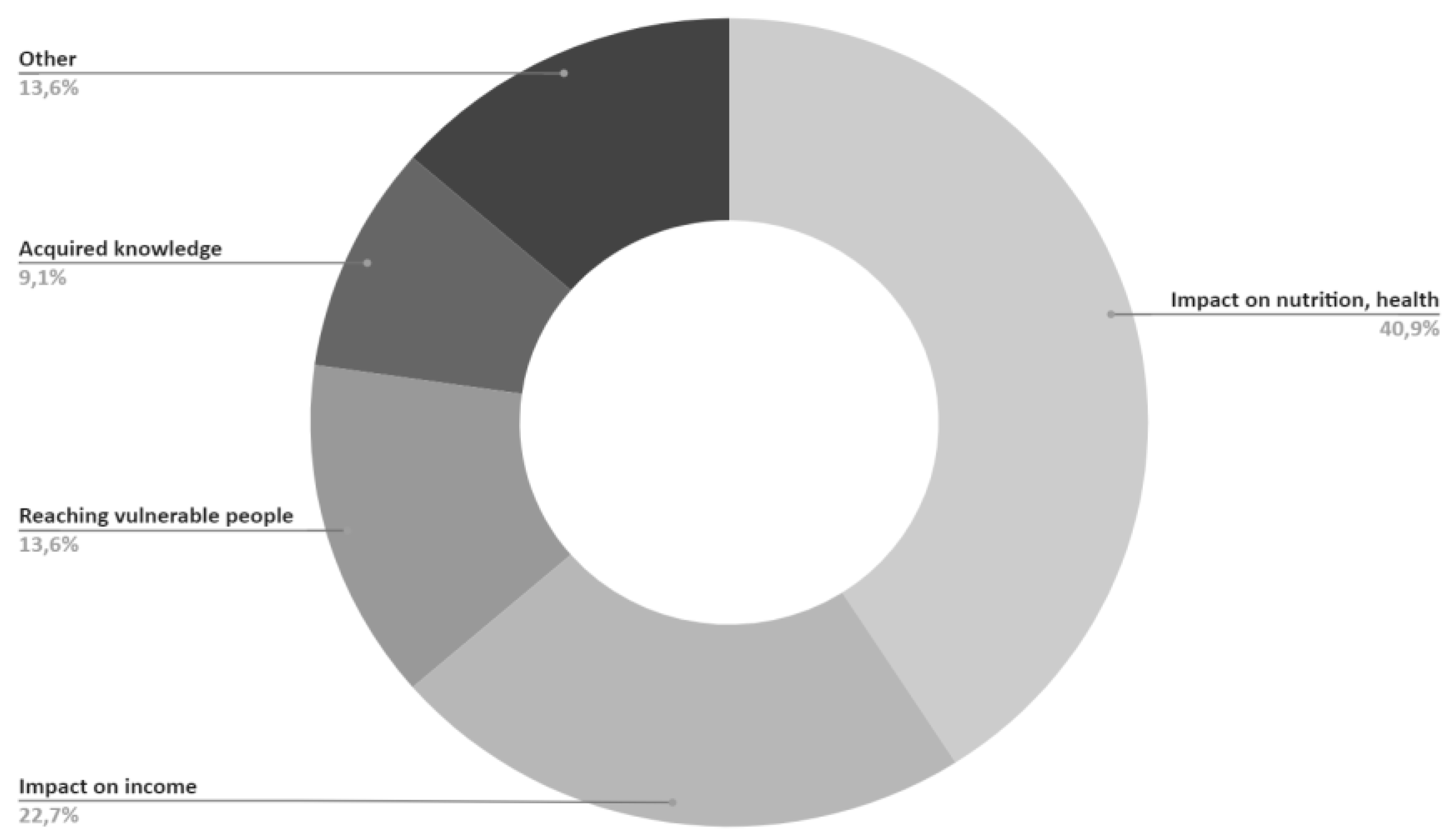

| 2 |

Impact on nutrition, health: Meeting the nutritional needs of beneficiaries; Improving the health of users; Improving the well-being of the elderly.

Impact on income: Helping beneficiaries' income; Creating jobs.

Reaching people in social vulnerability: Reaching low-income people.

Knowledge: Knowledge acquired by beneficiaries

Others: Perceived benefits, challenges and tensions; Motivating volunteers; Reducing GHG emissions.

|

References

- HLPE, F. L. (2014). Waste in the Context of Sustainable Food Systems. A Report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security.

- Nicastro, R., & Carillo, P. (2021). Food loss and waste prevention strategies from farm to fork. Sustainability, 13(10), 5443. [CrossRef]

- Belik, W. (2018). Estratégias para redução de perdas e desperdício de alimentos. Melo EV. Perdas e desperdício de alimentos: estratégias para redução. Brasília: Câmara dos Deputados, Edições Câmara, 33-52.

- Lombardi, M., & Costantino, M. (2020). A social innovation model for reducing food waste: The case study of an Italian non-profit organization. Administrative Sciences, 10(3), 45. [CrossRef]

- Shen, G., Li, Z., Hong, T., Ru, X., Wang, K., Gu, Y., ... & Guo, Y. (2024). The status of the global food waste mitigation policies: experience and inspiration for China. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 26(4), 8329-8357. [CrossRef]

- Benton, T. G., Bieg, C., Harwatt, H., Pudasaini, R., & Wellesley, L. (2021). Food system impacts on biodiversity loss. Three levers for food system transformation in support of nature. Chatham House, London, 02-03.

- Spang, E. S., Moreno, L. C., Pace, S. A., Achmon, Y., Donis-Gonzalez, I., Gosliner, W. A., ... & Tomich, T. P. (2019). Food loss and waste: measurement, drivers, and solutions. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 44, 117-156.

- FAO. (2015). Objetivos de desenvolvimento sustentável. Disponível em: https://brasil.un.org/pt-br/sdgs Acesso em: 12 abr. 2023.

- Boiteau, J. M., & Pingali, P. (2023). Can we agree on a food loss and waste definition? An assessment of definitional elements for a globally applicable framework. Global Food Security, 37, 100677. [CrossRef]

- FAO. (2019). The state of food and agriculture 2019: Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction. UN.

- Forbes, H. (2021). Food waste index report 2021.

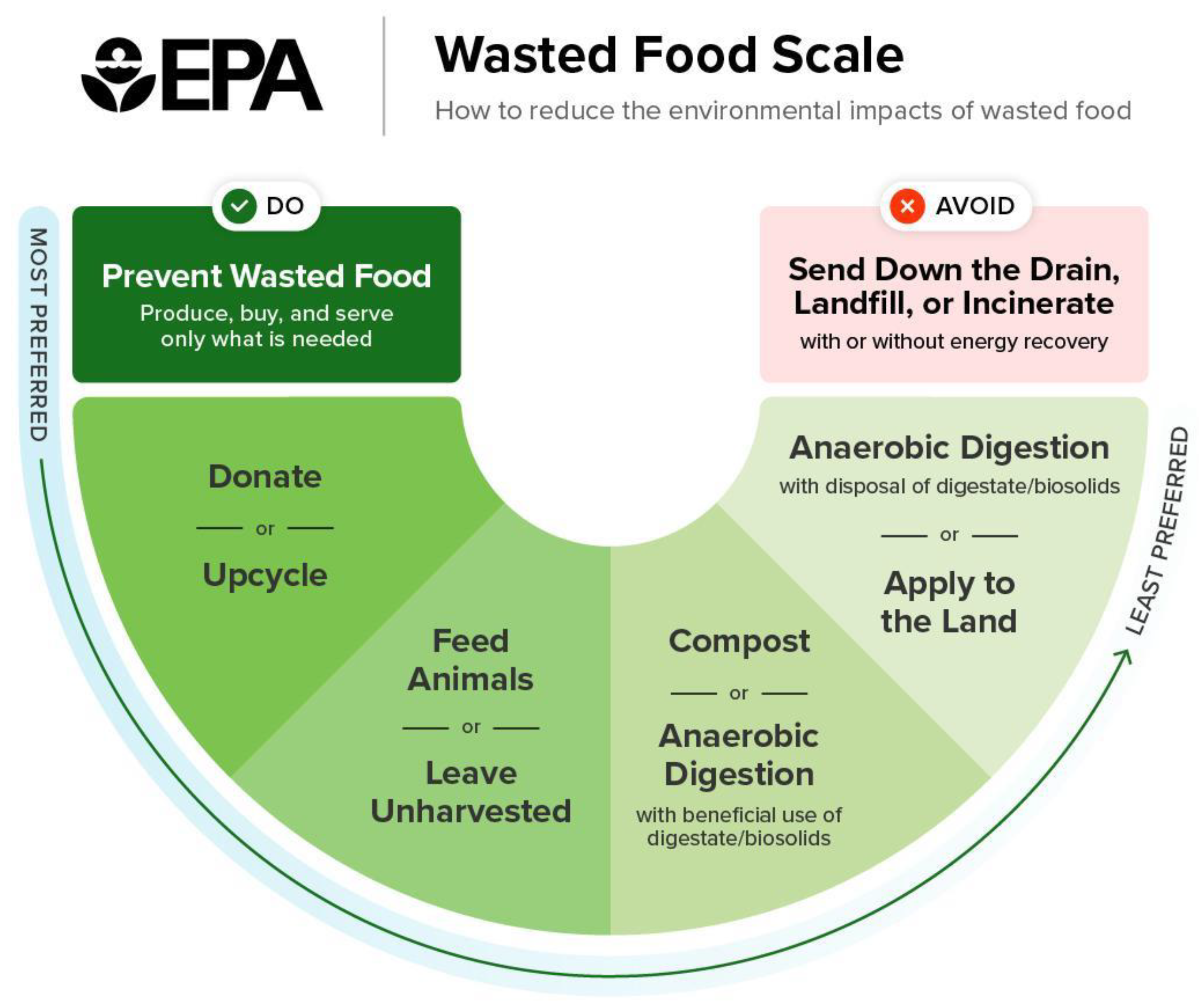

- U.S. EPA. (2023). From Field to Bin: The Environmental Impacts of U.S. Food Waste Management Pathways (Part 2).

- U.S. EPA. (2021). Sustainable management of food: Food recovery hierarchy. United States Environmental Protection Agency.

- Ceryes, C. A., Antonacci, C. C., Harvey, S. A., Spiker, M. L., Bickers, A., & Neff, R. A. (2021). “Maybe it’s still good?” A qualitative study of factors influencing food waste and application of the EPA Food recovery hierarchy in US supermarkets. Appetite, 161, 105111.

- Muth, M. K., Birney, C., Cuéllar, A., Finn, S. M., Freeman, M., Galloway, J. N., ... & Zoubek, S. (2019). A systems approach to assessing environmental and economic effects of food loss and waste interventions in the United States. Science of the Total Environment, 685, 1240-1254. [CrossRef]

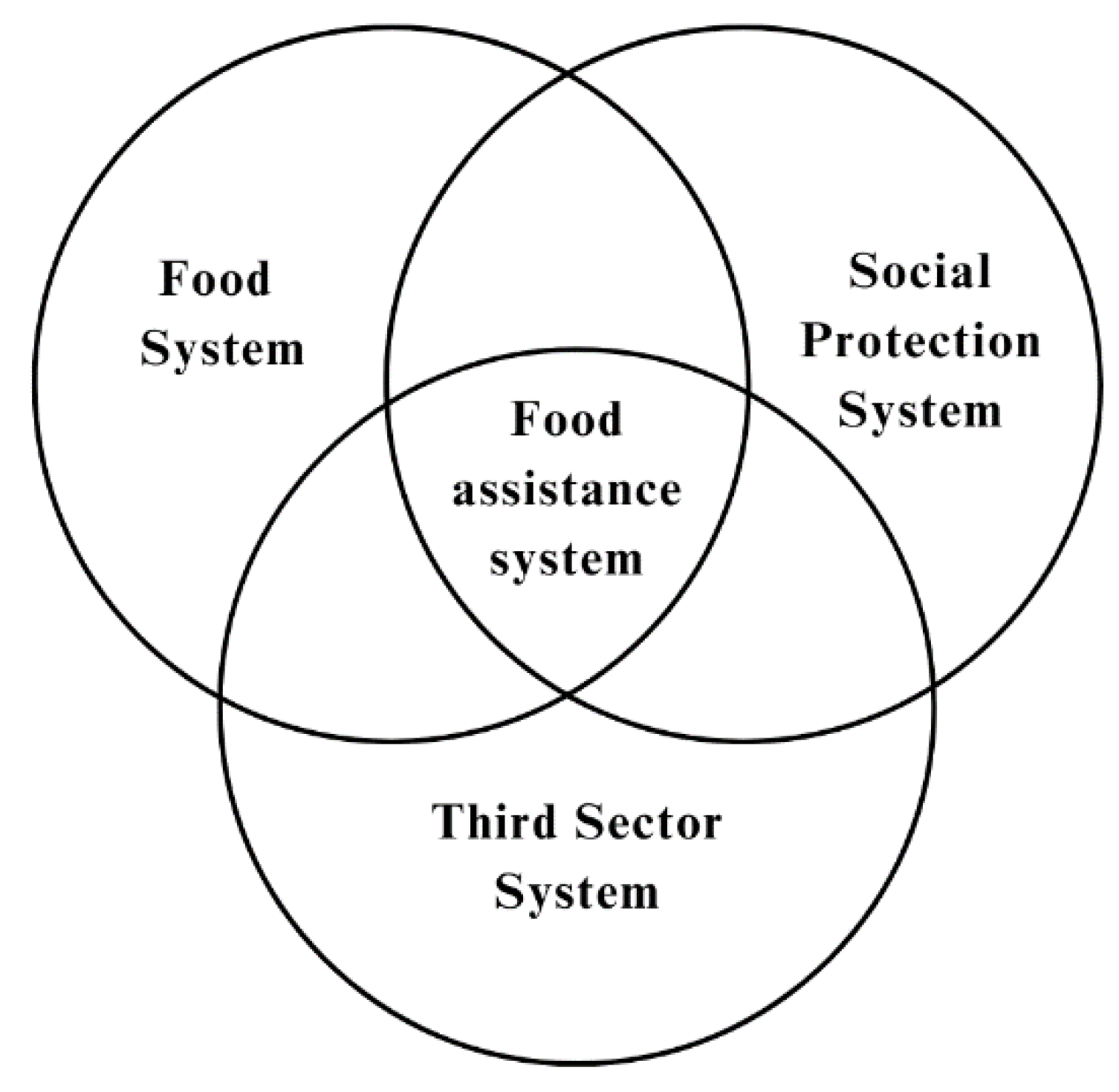

- Galli, F., Cavicchi, A., & Brunori, G. (2019). Food waste reduction and food poverty alleviation: a system dynamics conceptual model. Agriculture and Human Values, 36, 289-300. [CrossRef]

- Riches, G. (2018). Food bank nations: Poverty, corporate charity and the right to food. Routledge.

- Vansintjan, A. (2014). The political economy of food banks. McGill University (Canada).

- Watson, S. (2019). Food banks and food rescue organisations: Damned if they do; damned if they don't. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 31(4), 72-83. [CrossRef]

- Loopstra, R., & Lambie-Mumford, H. (2023). Food banks: Understanding their role in the food insecure population in the UK. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 82(3), 253-263. [CrossRef]

- Sedelmeier, T. (2023). Poverty Foodscapes: Why Food Banks Are Part of the Poverty Problem, Not the Solution. In Foodscapes: Theory, History, and Current European Examples (pp. 41-51). Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

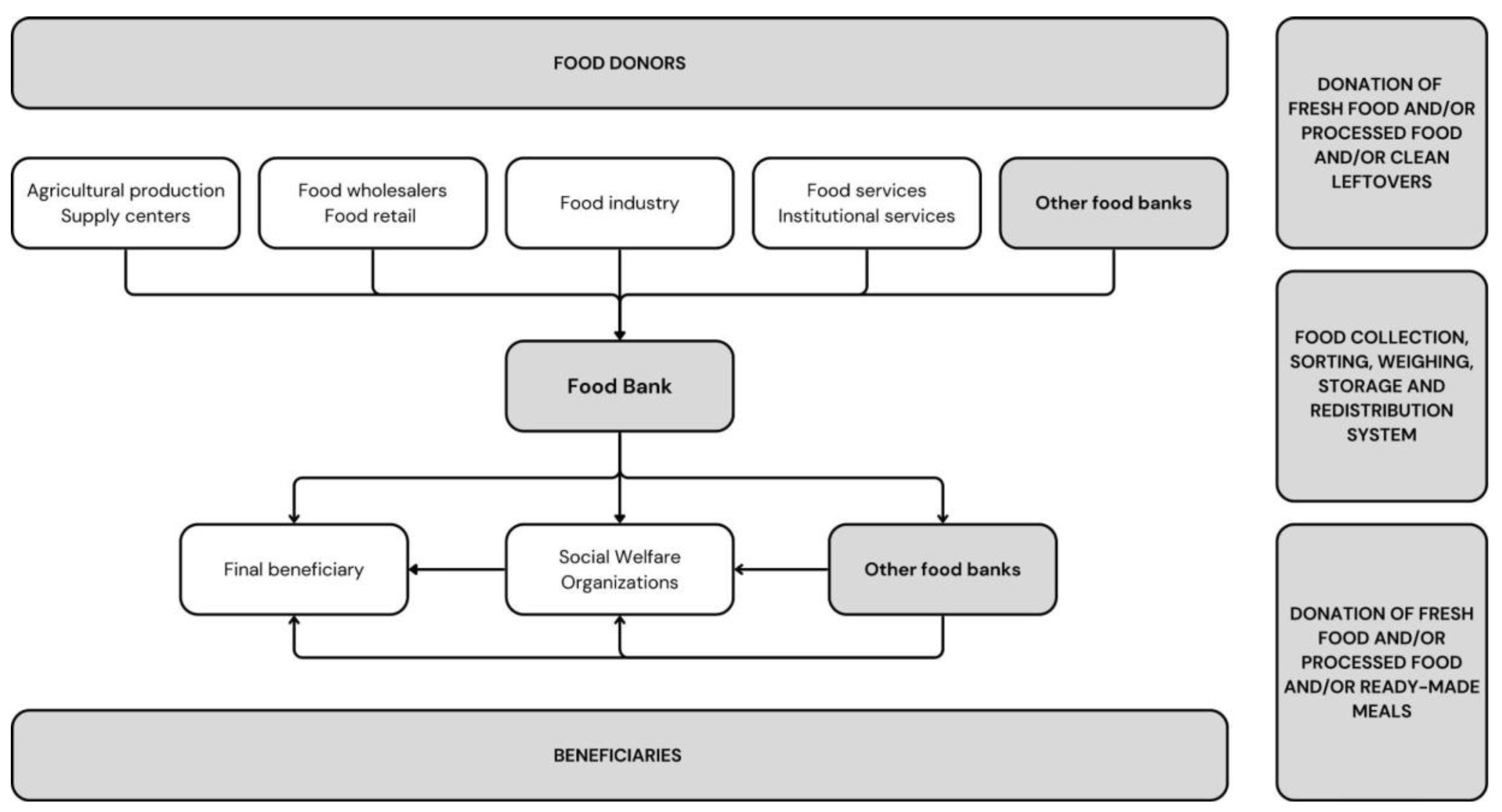

- Tenuta, N., Barros, T., Teixeira, R. A., & Paes-Sousa, R. (2021). Brazilian Food Banks: overview and perspectives. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12598.

- Lambie-Mumford, H. (2019). The growth of food banks in Britain and what they mean for social policy. Critical Social Policy, 39(1), 3-22. [CrossRef]

- Belik, W. B., de Almeida Cunha, A. R. A., & Costa, L. A. (2012). Crise dos alimentos e estratégias para a redução do desperdício no contexto de uma política de segurança alimentar e nutricional no Brasil. Planejamento e políticas públicas, (38).

- Byrne, A. T., & Just, D. R. (2022). Private food assistance in high income countries: A guide for practitioners, policymakers, and researchers. Food Policy, 111, 102300. [CrossRef]

- Rivera, A. F., Smith, N. R., & Ruiz, A. (2023). A systematic literature review of food banks’ supply chain operations with a focus on optimization models. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management, 13(1), 10-25. [CrossRef]

- González-Torre, P. L., & Coque, J. (2016). How is a food bank managed? Different profiles in Spain. Agriculture and Human Values, 33, 89-100. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, G. E., & Berlan, D. (2018). Evaluation in nonprofit organizations: An empirical analysis. Public Performance & Management Review, 41(2), 415-437. [CrossRef]

- Hecht, A. A., & Neff, R. A. (2019). Food rescue intervention evaluations: A systematic review. Sustainability, 11(23), 6718. [CrossRef]

- Kopczynski, M. E., & Pritchard, K. (2004). The use of evaluation by nonprofit organizations. Handbook of practical program evaluation, 649-669.

- Mitchell, G. E., & Berlan, D. (2016). Evaluation and evaluative rigor in the nonprofit sector. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 27(2), 237-250. [CrossRef]

- Jannuzzi, P. D. M. (2020). Avaliação de Programas Sociais em uma perspectiva sistêmica, plural e progressista: conceitos, tipologias e etapas.

- Jannuzzi, P. D. M. (2009). Indicadores sociais no Brasil: conceitos, fontes de dados e aplicações. In Indicadores sociais no Brasil: conceitos, fontes de dados e aplicações (pp. 141-141).

- Jannuzzi, P. D. M. (2022). Indicadores para diagnóstico, monitoramento e avaliação de programas sociais no Brasil. Revista do Serviço Público, 73(b), 96-123.

- Clark, M., Sartorius, R., & Bamberger, M. (2004). Monitoring and evaluation: Some tools, methods and approaches. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- DFID (2013). International Development Evaluation Policy. London: UK development aid. Disponível em: https://www.oecd.org/derec/unitedkingdom/DFID-Evaluation-Policy-2013.pdf Acesso em: 22 abr. 2023.

- Mayring, P. (2022). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken (13. Neuausgabe). Julius Beltz GmbH & Co. KG.

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., ... & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj, 372. [CrossRef]

- Galvão, M. C. B., & Ricarte, I. L. M. (2019). Revisão sistemática da literatura: conceituação, produção e publicação. Logeion: Filosofia da informação, 6(1), 57-73.

- Gentilini, U. (2013). Banking on food: The state of food banks in high-income countries. IDS Working Papers, 2013(415), 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Food Security Information Network (FSIN) and Global Network Against Food Crises. 2024. GRFC 2024. Rome. Available online: https://www.fsinplatform.org/report/global-report-food-crises-2024/ (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United States. Available online: https://www.fao.org/countryprofiles/lifdc/en/ (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- The Global Foodbanking Network. Available online: https://www.foodbanking.org/2023annualreport/ (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios Contínua : segurança alimentar : 2023; PNAD contínua : segurança alimentar : 2023. Available online: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv102084.pdf. (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- Akkerman, R., Buisman, M., Cruijssen, F., de Leeuw, S., & Haijema, R. (2023). Dealing with donations: Supply chain management challenges for food banks. International Journal of Production Economics, 262, 108926. [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilidouki, A., Rambe, M., Ardestani-Jaafari, A., Li, E., & Marcolin, B. (2023). Food bank operations: review of operation research methods and challenges during COVID-19. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 1783. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).