1. Introduction

The Water-Energy-Food-Ecosystems (WEFE) Nexus approach is increasingly recognized as vital for addressing interconnected challenges related to water, energy, food, and ecosystem management issues. The WEFE Nexus paradigm entails the coordination, integration, and cost-effective planning and management of interconnected natural resources across these sectors. Strategic collaboration and synergistic efforts within this approach can yield enhanced overall resource security compared to conventional fragmented strategies. This methodology facilitates the identification of synergies in natural resource management to achieve objectives such as ensuring WEFE security, conserving ecosystems and their functions, bolstering climate resilience, and facilitating the transition to green economies. However, achieving these objectives necessitates inter-sectoral capacity building and cooperation among professionals engaged in relevant water, energy, food and ecosystem strategic and operational initiatives, particularly within food production [

1,

2]. The adoption of a WEFE Nexus approach promotes resource efficiency by optimizing the use of water, energy, and food resources. For instance, improving irrigation efficiency not only conserves water but also saves energy used for pumping water and enhances agricultural productivity [

3]. Similarly, renewable energy technologies such as solar and wind can reduce water usage compared to fossil fuel-based energy generation [

4]. The WEFE Nexus acknowledges the interdependencies and trade-offs between water, energy, food, and ecosystems. Changes or disruptions in one sector can have cascading effects on others. For example, water scarcity can impact energy production (e.g., hydropower), agricultural productivity, and ecosystem health [

5,

6]. Understanding these interconnected relationships is also vital for reaching sustainable development goals (SDGs). With regard to sustainable development, the WEFE Nexus is closely aligned with several SDGs, particularly Goal 2 (Zero Hunger), Goal 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), Goal 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), Goal 13 (Climate Action), and Goal 15 (Life on Land) [

7].

Adopting a Nexus approach can facilitate the achievement of these goals by promoting integrated solutions and holistic planning [

8]. Consequently, climate change intensifies existing challenges within the WEFE Nexus. Increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, such as droughts and floods, disrupt water availability, agricultural production, and energy infrastructure [

9]. By adopting a Nexus approach, countries can enhance their resilience to climate change impacts by integrating adaptation and mitigation strategies across sectors [

10]. Hence, ensuring access to water, energy, and food is essential for human security and socio-economic stability. The WEFE Nexus approach helps identify vulnerabilities and risks within these systems, allowing for more effective management and mitigation strategies [

11]. By addressing the root causes of resource scarcity and enhancing resilience, the Nexus approach contributes to reducing conflicts over natural resources. Of no less importance and in line with the previous statement is the fact that managing these shared resources effectively requires cooperation and collaboration among countries. The WEFE Nexus provides a framework for dialogue and cooperation, fostering regional partnerships and promoting sustainable management of transboundary resources, eventually leading to improved higher education curricula [

12]. The multi-dimensional concept of the WEFE Nexus approach is important from a global perspective because it recognizes the interconnected nature of water, energy, food, and ecosystems, promotes resource efficiency, enhances climate resilience, contributes to security and stability, aligns with sustainable development goals, and encourages transboundary cooperation [

13,

14].

Nevertheless, the WEFE Nexus approach is not an ideal concept and should not be seen as

panacea universalis for all natural resource management challenges. However, the multidimensional nature of the WEFE Nexus approach allows adjustments, with appropriate focus on emerging challenges [

15]. For instance, the adjusted WEFE Nexus approach is promoted by COST Action CA20138: Network on water-energy-food Nexus for a low-carbon economy in Europe and beyond, where the advantages of the adjusted WEF Nexus approach are used to target a low-carbon economy [

16]. This unequivocally suggests that WEFE Nexus approach should be focused on carbon footprint management, greenhouse gas (GHG) elimination, and climate change mitigation strategies [

17]. The coupling of the relevant ISO sectoral standards requirements, primarily ISO 22000 and ISO 140067, results in more carbon-sensitive, participatory-based and climate-responsible WEFE Nexus application [

18,

19]. This modification reveals a tendency toward more climate resilient societies, ready to combat greenhouse gas emissions [

20,

21,

22]. Since later stages of modified WEFE Nexus approach create the need for an adequate decision-making process in significantly modified surroundings compared to the initial WEFE Nexus approach, the introduction of multi-criteria decision analysis backed by expert decisions is more than welcome [

23,

24,

25].

In accordance with the aforementioned facts, the aim of this paper is to analyze the advantages of the WEFE Nexus approach, elaborate the intensity of standardization in the field of food safety on the example of Balkan countries, provide a brief insight into carbon footprint relevant standards, and provide an adequate MCDA structure, referencing the WEFE Nexus needs and standards requirements.

The introduction offers an in-depth analysis of the characteristics of the Water-Energy-Food-Ecosystems (WEFE) Nexus, highlighting its advantages. This includes assessments of the benefits associated with adopting a WEFE Nexus approach, such as improved resource efficiency, enhanced resilience to climate change impacts, and greater socio-economic stability.

The second part of the paper delves into the practical aspects of standardization within the WEFE Nexus domain and carbon footprint management. This involves qualitative evaluations of the feasibility and effectiveness of implementing standardized protocols and methodologies across various sectors. It includes discussions on the potential benefits of standardization, such as improved comparability of data, enhanced transparency, and streamlined decision-making processes. The paper concludes with the presentation of a robust Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) hierarchical model. This model is developed based on expert-based assessments of selected relevant criteria, factors, and alternatives joined within the WEFE Nexus framework, food safety and carbon footprint management. Additionally, it includes a detailed example of an expert choice session, demonstrating the application of the MCDA model in real-world decision-making scenarios. The quantitative analysis within this section provides insights into the effectiveness and applicability of the MCDA approach in addressing complex interdependencies within the food safety as a part of the WEFE Nexus and carbon footprint mitigation.

2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review

Standardization holds immense importance across various fields and industries for several reasons. Standardization ensures that different systems, products, and processes can work together seamlessly [

26,

27,

28]. This is particularly important in sectors such as technology, manufacturing, healthcare, waste management, education, etc., where compatibility between various components is essential for efficiency and effectiveness [

29]. Standards define best practices and specifications, helping to maintain and improve the quality of products and services. By adhering to standardized processes and procedures, organizations can ensure consistency in their output, thereby enhancing customer satisfaction and trust.

With regard to environment and risk management, standardization can contribute to environmental sustainability by promoting eco-friendly practices. Standardized risk management frameworks and practices help organizations identify, assess, and mitigate risks more effectively [

30]. By following established protocols, businesses can anticipate and respond to potential threats in a guided manner, safeguarding their operations and reputation. Environmental standards ensure that products and materials are sourced, produced, and distributed in an environmentally responsible manner. Standards for sustainable forestry, water, responsible mining, and fair trade promote transparency and accountability across supply chains, reducing deforestation, habitat destruction, and social inequalities [

31]. Standards for land use planning, habitat restoration, and biodiversity management contribute to the conservation of ecosystems and wildlife. By establishing criteria for sustainable land development and ecosystem restoration, standardization helps preserve biodiversity/ecosystems. Standardization provides frameworks for environmental monitoring, data collection, and reporting [

32]. Standards for environmental management systems (e.g., ISO 14001) allow organizations to assess and improve their environmental performance, track progress towards sustainability goals, and communicate their efforts to stakeholders [

33]. Additionally, standardization is crucial for food safety across various stages of the food supply chain. Standardization ensures that food products meet established safety requirements, protecting consumers from health risks associated with foodborne illnesses or any kind of contamination. Adherence to food safety standards raises confidence in consumers, enhancing trust in the food supply chain, which is dominantly achieved through implementation of the ISO 22000 standard [

34].

In line with the previous statement, food production, particularly agriculture, contributes to greenhouse gas emissions through activities such as land use change, livestock rearing, fertilizer application, and machinery use. The carbon footprint of food production varies depending on factors such as production methods, inputs used, and transportation. The carbon footprint of food production contributes to climate change by releasing greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide (CO

2), methane (CH

4), and nitrous oxide (N

2O) into the atmosphere [

35]. Climate change, in turn, affects food production through changes in temperature, precipitation patterns, and extreme weather events, leading to disruptions in agricultural productivity and food security. So, addressing the carbon footprint of food production is essential for promoting sustainable agriculture practices minimizing environmental impact while ensuring food security and livelihoods [

36].

Sustainable agriculture emphasizes resource efficiency, biodiversity conservation, soil health, and resilience to climate change, aiming to balance economic, social, and environmental objectives. Efforts to reduce the carbon footprint of food production involve implementing mitigation strategies such as improving agricultural practices, enhancing soil carbon sequestration, reducing fertilizer and pesticide use, increasing energy efficiency, and transitioning to low-carbon technologies [

37]. These strategies can help mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, enhance carbon storage, and promote environmental sustainability in food systems [

38]. Consequently, the answer in the context of searching for an appropriate carbon footprint mitigation strategy is to apply the corresponding sector standard, in this case ISO 14067:2018 [

35].

Indeed, the comprehensive ISO 14060 series aims to offer clarity and uniformity concerning the measurement, tracking, declaration, and authentication or confirmation of GHG emissions or removals, with the goal of fortifying sustainable development within economies striving for low carbon footprints [

39]. ISO 14064-1 provides counsel to entities on how to measure and declare their GHG emissions and removals, encompassing the principles, prerequisites, and guidelines for conducting GHG inventories. This involves delineating boundaries, selecting emission sources, quantifying emissions, and reporting outcomes. ISO 14064-1 is applicable to organizations of various sizes and types [

20]. ISO 14064-2 is centered on GHG projects, offering guidance on quantifying, monitoring, and reporting emission reductions or enhancements achieved through specific projects. It stipulates requirements for project design, establishing baselines, monitoring, reporting, and verifying. ISO 14064-2 is especially pertinent for organizations executing GHG reduction projects, such as those related to renewable energy or energy efficiency enhancements [

21]. ISO 14064-3 sets forth requirements and guidance for the validation and verification of GHG assertions, spanning GHG inventories and project emission reductions. It delineates the roles and responsibilities of validators and verifiers, along with the procedures and criteria for validation and verification activities. ISO 14064-3 aims to ensure the trustworthiness, precision, and openness of GHG information reported by organizations and projects [

22].

Finally, ISO 14067 specifies principles, prerequisites, and guidelines for quantifying and communicating the carbon footprint of products, encompassing goods and services. It applies to all organizations engaged in product production, distribution, and consumption, regardless of the size, sector, or location. This standard outlines methodologies and procedures for computing the carbon footprint of products across their life cycles, covering stages such as raw material extraction, production, transportation, use, and disposal or recycling. It provides guidance on data collection, emission factors, allocation methods, and calculation tools to ensure consistency and accuracy in carbon footprint assessments. ISO 14067 necessitates defining a functional unit for the product, serving as a benchmark for comparing different products and assessing their carbon footprints relative to their intended purpose. The standard also specifies the system boundary for carbon footprint assessments, requiring organizations to justify their choices regarding included or excluded life cycle stages or emission sources based on relevance, materiality, and consistency with established methodologies. ISO 14067 offers guidance on the allocation of GHG emissions among co-products or multi-functional processes within the product system, recommending transparent and scientifically sound allocation methods while emphasizing the importance of data quality and uncertainty assessment in carbon footprint calculations. Furthermore, ISO 14067 advocates for clear, transparent, and understandable communication of carbon footprint results to stakeholders, promoting informed decision-making and sustainable consumption and production patterns [

35].

To conclude, in terms of food safety requirements, ISO 22000:2018 requires the establishment of a food safety management system (FSMS). Furthermore, in the domain of standardization, detailed insight on carbon footprint management is provided by the ISO 14067:2018 standard. Yet, what is common to all the standards mentioned here is that they do not offer methods for selecting priority measures (although they define the obligation to plan and define goals – for instance, organizations must establish procedures to manage food safety hazards during production, storage, and distribution but there is no guidance on how to identify procedure priorities), so in the decision-making phase, it is desirable to establish straight decision-making mechanisms, which are given below through the proposed MCDA model.

3. Materials and Methods

For the purpose of this research, a comprehensive literature research approach was employed, coupled with relevant standards requirements analysis and ISO survey data usage [

40]. Initial ISO survey data were used to assess the level of standardization on the level of Balkan countries, with addition of the two new indicators: number of ISO 22000 certificates per one billion of the GDP (Cert/BGDP) and number of ISO 22000 certificates per one hundred thousand inhabitants (Cert/kinh) [

41,

42]. A similar approach in the creation of derived meta-indicators can be found in recent literature [

43]. This involved amalgamating and collaborating on pertinent academic literature related to the Water-Energy-Food-Ecosystem (WEFE) Nexus, along with utilizing accessible online databases. Additionally, a comparative analysis of the rate of implementation of various system standards at the global level was conducted, where, in the first part of the research, ISO Survey data are used to present the quantitative data on the total count of system standard certificates [

44].

The second part of the research is aimed at descriptive analysis of the ISO 22000:2018 system standard requirements and its connections with the WEFE Nexus approach, food safety, and environmental aspects. Given that the focus of the ISO 22000:2018 standard is the production of health-safe food, but also the establishment of a mutually beneficial relationship with stakeholders and environmentally responsible businesses, as a supplement to this system standard in the context of sustainable management of the carbon footprint and greenhouse gases, the ISO 14067:2018 standard was identified which targets the inventory of GHG sources as well as specific areas for carbon footprint mitigation.

What is common to all system standards and what is also found in ISO 14067:2018 is the fact that these types of standards provide an extremely high-quality conceptual framework and standardized, highly traceable procedures. The fact is that the requirements of the standard are clearly definable, that the organization that applies them is obliged to define a related, relevant policy, to analyze the relevant aspects (in the case of 14067, carbon footprint), carry out a planning process and define the methods, resources and activities with which it intends to reach the desired goals.

Regarding the definition of goals and methods of achieving them, the system standards do not define the methodology for choosing priority goals in the specific case of carbon footprint mitigation, so for the purpose of prioritization as well as the analysis of the level of influence of different alternatives, the multi-criteria decision-making method was applied in [

45]. A defined decision-making hierarchy in the selection of priority areas of carbon footprint mitigation was created with reference to the requirements of ISO 22000:2018, ISO 14067:2018, as well as the guidelines of the BREF document for the production of food, drink and milk, which provides a significant level of identification of environmental risks in the food production process [

46].

The created hierarchical decision-making model represents a unique combination of the requirements of one system and one technical standard as well as one BREF document, and thus follows the integrative nature of the WEFE Nexus approach to a proper extent [

47,

48]. Considering the importance of the input data, adequate online surveys were used. The relevant institutions that observe the standardization process are primarily ISO and IAF, followed by CEN and OECD.

4. Results and Discussion

Table 1 displays the quantitative data on the total count of certificates issued annually (Year 2022 in this case) for each system standard, sourced from the International Accreditation Forum (IAF), available as ISO survey documents [

40]. Additionally, it presents the percentage distribution of individual system standards relative to the overall count of issued certificates across all system standards. Similarly, an examination of the number of registered locations where these certificates are utilized is provided as a percentage share. The variance between the number of issued certificates and the places of application arises due to the possibility of one economic entity possessing a single certificate applicable across multiple locations or work units.

In the context of the analysis of the data obtained using the calculation presented in

Table 1, it is noticeable that the so-called key system standards have the largest number of confirmed certificates in 2022, namely ISO 9001 (about 52%), ISO 14001 (about 23%) and ISO 45001 (about 16%), and that together they make up 90% of all certified certificates. Another interesting fact is that these standards often form the basis of most integrated management systems.

Considering the fact that standardization follows trends in society and the economy, it is not surprising that ISO 27001 is represented by approximately 3% of the total certificates issued in 2022. Concerning the WEFE Nexus and the safe food production system, the share of the total number of issued ISO 22000 certificates is almost 2%, with a steady growth trend, which indicates the relevance of this standard.

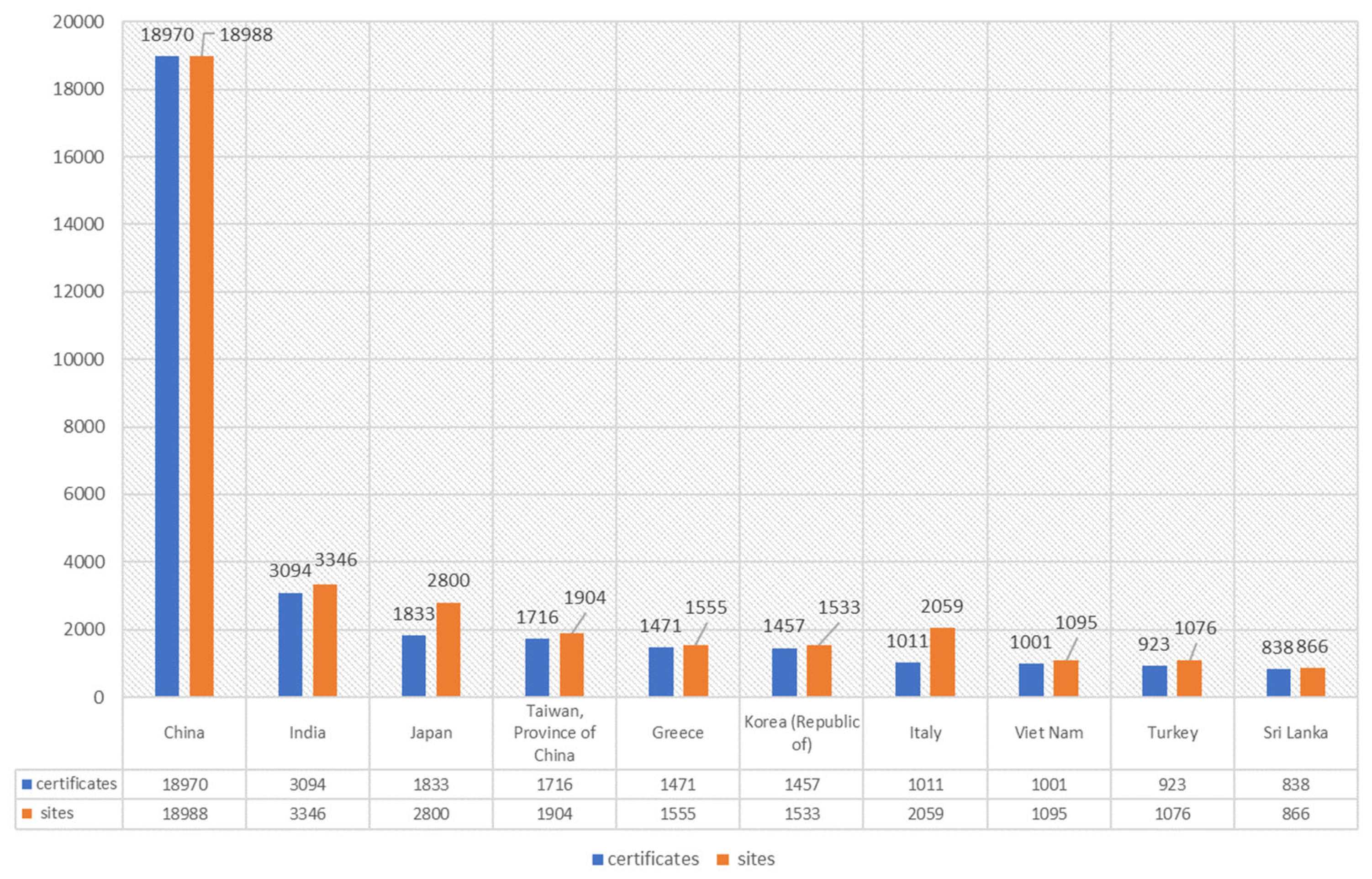

In a similar way,

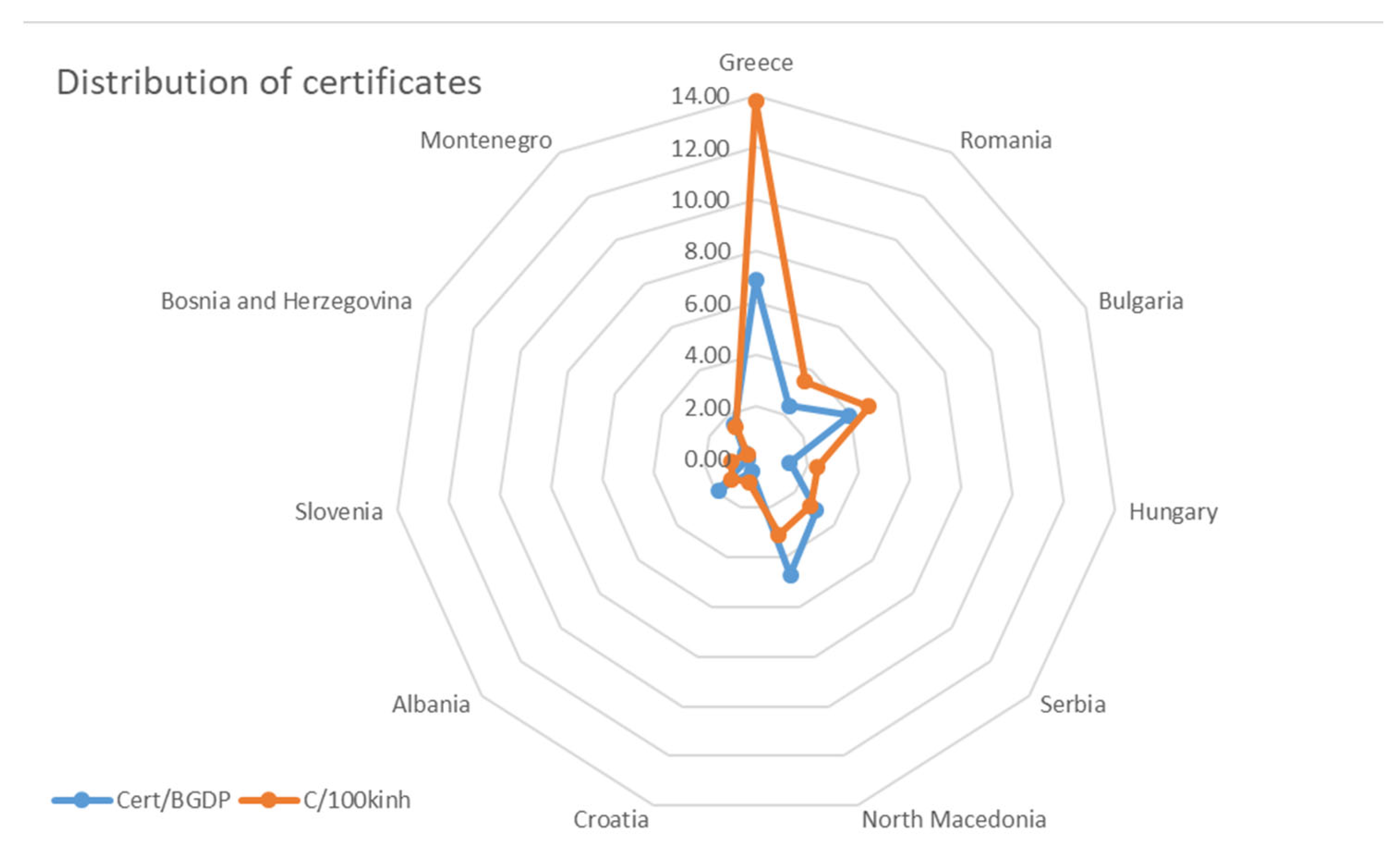

Figure 1 shows the world’s ten leading countries in issued certificates while

Figure 2 shows the distribution of ISO 22000:2018 certificates among Balkan countries.

In the context of the analysis of the number of certificates issued by the countries of the world, it is interesting to note that there is a huge difference between the two most populous countries in the world, China and India, since the number of issued certificates is 6 times higher in China (18,970 versus 3,094). In addition to this non-compliance, it is interesting that Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan have a significant number of registered certificates, while from Europe, Greece and Italy are among the ten countries with the largest number of certificates issued. It is also worth noting that the countries that are considered as synonyms for quality (Germany, France, Great Britain, USA...) are not ranked among the top ten countries.

In the context of the analysis of the number of ISO 22000 certificates issued among Balkan countries, Greece takes the first place with by far the largest number of certificates, followed by Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary. Interestingly, Serbia and North Macedonia, although not members of the EU, have a respectable number of registered certificates, while Croatia and Slovenia, as members of the EU, do not have a significant number of certificates issued in this area. Somewhat unexpectedly, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina are at the bottom of the list.

Given that the nominal number of certificates issued provides only a rough insight into the level of standardization in a certain area, for the purpose of a more detailed assessment of the intensity of standardization and for the purpose of this paper, two new meta-indicators were created, specifically the number of issued certificates per one billion GDP (Cert/BGDP) and the number of issued certificates per 100 thousand inhabitants (Cert/100kinh). Data on GDP and population were taken from Eurostat databases. After creating new indicators and applying them to the Balkan countries, it is possible to conclude the following (

Figure 3):

Greece is the absolute leader in the field of standardization, with 6.85 Cert/BGDP and 13.80 Cert/100kinh, followed by Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary, creating the same order as in the example of the total number of certificates issued.

It is interesting to note that, on the example of Serbia and North Macedonia, a difference can be observed in the comparison between the total number of certificates issued and the number of certificates issued. Namely, North Macedonia has more certificates issued per one billion GDP than Serbia (4.71 versus 3.1), as well as in the category of the number of certificates issued per 100 thousand inhabitants (3.10 versus 2.80). In a similar way, the difference is observed between Albania and Croatia (1.91 vs. 0.55) or Montenegro and Slovenia (1.53 vs. 0.32).

Based on the given analyses, it is possible to conclude that there is a significant but not linear correlation between the number of certificates issued and the development of the national economy, i.e., the number of inhabitants of a certain country. This confirms the view that the intensity of standardization is the result of several factors, starting from the development and diversification of the economy, historical heritage, quality culture, international connections, as well as stimulation and incentives in the field of standardization.

The performed analysis points to the fact that there is a well-developed practice of applying standards for the production of health-safe food (a typical example is Greece) and that it is necessary to think about a harmonized decision-making model in the context of creating a balance between the requirements for the production of health-safe food and the minimization of the carbon footprint, wherein the following MCDA decision-making model should be seen as a proactive component.

The proposed ISO 22000/ISO 14067 balanced hierarchical structure consists of three levels, as shown in

Table 2. Factors at the second level influence each individual criterion at the first level, while the alternatives describe the individual factors in more detail.

The analytic hierarchy process is used for ranking. It is applied in the fuzzy domain, using triangular fuzzy numbers [

49]. The standard fuzzified Saaty scale is used, with values from (1,1,3) to (7,7,9). The influence of expert

i is described by the coefficient

θi, which is determined based on the expert's work experience (

ei), experience in food production (

fi), and sustainability in general (

si), as follows:

where n is the total number of experts (1≤

i≤

n), while

fi,

fj,

ei,

ej,

si, and

sj are from the set {1,3,5}, which represents the quantitative values of the experts’ experience [

22]. A value of 5 represents more than 10 years of experience, while a value of 1 represents a maximum of 5 years of experience.

Five experts participated in determining the weights of influential criteria and factors. Their influence on the final decision is defined by the set

Θ={0.12,0.18,0.18,0.26,0.26}. All expert matrices were consistent, and the CCI index for group decision-making had acceptable values [

45]. The aggregate matrix for the criteria was

on the basis of which the fuzzy weights of criteria

wC1=(0.18,0.43,0.78),

wC2=(0.18,0.43,0.78), and

wC3=(0.18,0.43,0.78) were determined. Crisp values of criteria weights, obtained by defuzzification, are presented by the vector

WC={0.386, 0.287, 0.327}.

The elements of aggregate matrices of factors in relation to criteria (

Ci) and fuzzy weights (

FWs) are shown in

Table 3.

Based on the fuzzy weights of the factors, the following crisp weights were determined: WF={0.229, 0.191, 0.201, 0.168, 0.212}.

The elements of the matrix of alternatives in relation to the criteria are shown in the following

Table 4.

Expert ranking gave the following results. Among the criteria, Environment (wC1=0.386) stands out as the most important, followed by Society (wC2=0.287) and Economy (wC3=0.327). The factors have very close weight values, viewed collectively in relation to all three criteria. Among the factors, Production (wF1=0.229), Waste/disposal (wF5=0.212), and Processing (wF3=0.201) are more prominent. Comparing a number of alternatives in relation to factors and criteria can lead to the fact that, if the factor is not dominant and the alternatives have similar importance, their overall importance for sustainable food production would be much lower than the real impact. Therefore, without diminishing the importance of the global ranking, we highlight alternatives in relation to each individual influencing factor.

In relation to factor F1, alternative P1 (Land use) with weight wP1=0.080 has the greatest importance. In relation to factor F2, the experts highlighted the importance of alternatives T2 (Route options) and T3 (Fuel usage), with weights wT2=0.053 and wT3=0.062.

Regarding factor F3, described by five alternatives, PR2 (Emission to water), PR3 (Emission to air), and PR4 (Processing waste) were highlighted as particularly significant alternatives, with weights wPR2=0.054, wPR3=0.053, and wPR4=0.051, respectively. With regard to factor F4, the experts identified S2 (Cooling and heating) and S3 (Package) as key alternatives, with weights of wS2=0.054 and wS3=0.056. Finally, a very significant factor for sustainable food production is F5, with particularly prominent alternatives WD3 (Treatment and reuse) and WD4 (Disposal), and their weights wwd3=0.064 and wwd4=0.059.

The difference between the individual weights of the alternatives, viewed globally, is small. Sensitivity to changes in weights is much more pronounced globally than locally, as observed within individual groups of alternatives, where there are always dominant alternatives.

5. Conclusions

This paper presented a research on the integrative nature of the WEFE Nexus approach that may be observed from different perspectives, namely standardization, carbon neutrality, and safe food production. The fact is that there is no harmonized implementation model of the WEFE nexus approach, and thus no appropriate metric of the performance of Nexus actions at different levels. This can be replaced by an analysis of the degree of standardization in different fields, which is illustrated in the first part of the paper. A critical review of the combination of applied methods lays the foundation for improving the used model and for considering limitations. The basic flaw in the system standards intended for the production of health-safe food is an excessive focus on the delivery of a health-safe product, with little or no reference to environmental aspects. As standardization in itself, especially in the domain of system standards, enables the integration of the requirements of several standards into a single integrated management system, it is desirable in the future to always recommend the integration of the requirements of ISO 22000 and ISO 14067, with the possibility of including ISO 14090. This is very important to bear in mind because of the fact that for most researchers and other stakeholders, integration implies the inclusion of ISO 9001, 14001, or 45001 standards only. In addition, as there are no instructions for the selection of priorities in the requirements of system and sector standards, the proposed MCDA model is an appropriate scientific and professional step forward. In the context of objective decision-making as well as the sustainability of defined decisions, the engagement of a larger number of experts from different backgrounds enables an additional level of compliance, diverse capacity, and flexibility-adaptability in the decision-making process. Relevant to the research topic, by viewing the food production process as part of a larger system, stakeholders can identify feedback loops, interdependencies, and potential unintended consequences of decisions. Integration of all these concepts – systems thinking, resilience, resource management, food safety (ISO 22000), and multi-criteria decision-making – creates a synergistic approach to addressing modern food production challenges. Together, they allow stakeholders to design adaptive, sustainable, and safe food systems that not only meet present demands but also preserve resources and resilience for future generations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.V. and Ž.V.; methodology, T.R.; formal analysis, G.J.; resources, D.V.; data curation, S.Ž.; writing—original draft preparation, D.V. and G.J.; writing—review and editing, D.V.; visualization, G.J. and Ž.V.; supervision, D.V.; project administration, S.Ž.; funding acquisition, D.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research was conducted with integrity, fidelity, and honesty. All ethical procedures were considered.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia (Contracts No. 451-03-66/2024-03/200148 and 451-03-66/2024-03/200371). Part of this publication is based upon work from the COST Action <CA20138: Network on water-energy-food Nexus for a low-carbon economy in Europe and beyond – NEXUSNET>, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adamovic, M.; Al-Zubari, W.; Amani, A.; Ameztoy Aramendi, I.; Bacigalupi, C.; Barchiesi, S.; Bisselink, B.; Bodis, K.; Bouraoui, F.; Caucci, S.; Dalton, J.; De Roo, A.; Dudu, H.; Dupont, C.; El Kharraz, J.; Embid, A.; Farajalla, N.; Fernandez Blanco Carramolino, R.; Ferrari, E.; Ferrini, L.; Filali-Meknassi, Y.; Franca, M.; Ghaffour, N.; Girardi, V.; Grizzetti, B.; Hannah, C.; Hidalgo Gonzalez, I.; Houmoller, O.; Jaeger-Waldau, A.; Jimenez Cisneros, B.; Kavvadias, K.; Kougias, I.; Laamrani, H.; Lemessa Tesgera, S.; Liebaerts, A.; Lipponen, A.; Lorentzen, J.; Makarigakis, A.; Marence, M.; Martin, L.; Michalena, E.; Mishra, A.; Mohtar, R.; Moner Gerona, M.; Moreno-Abat, M.; Mpakama, Z.; Pastori, M.; Pistocchi, A.; Sartori, M.; Schmeier, S.; Schmidt-Vogt, D.; Sehring, J.; Smakhtin, V.; Szabo, S.; Takawira, A.; Thiem, M.; Tiruneh, J.; Tsani, S.; Van Hullebusch, E.; Verbist, K.; Xenarios, S.; Zaragoza, G. Position Paper on Water, Energy, Food and Ecosystem (WEFE) Nexus and Sustainable development Goals (SDGs), Carmona Moreno, C., Dondeynaz, C., Biedler, M. editor(s), EUR 29509 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2019, ISBN 978-92-79-98276-7, doi:10.2760/5295, JRC114177. [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, J.D.; Bottaro, G.; Barci, L.; Beltrán, L.M.; Londoño-Behaine, M.; Masiero, M. Assessing the Impacts of Nature-Based Solutions on Ecosystem Services: A Water-Energy-Food-Ecosystems Nexus Approach in the Nima River Sub-Basin (Colombia). Forests 2024, 15, 1852. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15111852. [CrossRef]

- European Commission, (2021). Understanding the climate-water-energy-food nexus and streamlining water-related policies. Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/news/all-research-and-innovation-news/understanding-climate-water-energy-food-nexus-and-streamlining-water-related-policies-2021-03-19_en#:~:text=A%20climate%2Dwater%2Denergy%2D,trade%2Doffs%20between%20different%20policies (Accessed 05.12.2024.).

- Shehadeh, A.; Alshboul, O.; Arar, M. Enhancing Urban Sustainability and Resilience: Employing Digital Twin Technologies for Integrated WEFE Nexus Management to Achieve SDGs. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7398. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177398. [CrossRef]

- Cremades, R.; Mitter, H.; Tudose, N.C.: Sanchez-Plaza, A.; Graves, A.; Broekman, A.; Bender, S.; Giupponi; C., Koundouri; P., Bahri; M., Cheval, S. Ten principles to integrate the water-energy-land nexus with climate services for co-producing local and regional integrated assessments. Sci. Tot. Env. 2019 693, 133662 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.133662. [CrossRef]

- Nanfuka, J.; Oosthuizen, R. (2023). System dynamics modelling of the water-energy nexus in South Africa: a case of the Inkomati-Usuthu water management area. S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. 2023, 34(3), 170–181. https://doi.org/10.7166/34-3-2946. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme – UNDP, 2016. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals (Accessed 06.12.2024.).

- Papadopoulou, C.-A.; Papadopoulou, M.P.; Laspidou, C. Implementing Water-Energy-Land-Food-Climate Nexus Approach to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals in Greece: Indicators and Policy Recommendations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4100. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074100. [CrossRef]

- Simane, B.; Kapwata, T.; Naidoo, N.; Cissé, G.; Wright, C.Y.; Berhane, K. Ensuring Africa’s Food Security by 2050: The Role of Population Growth, Climate-Resilient Strategies, and Putative Pathways to Resilience. Foods 2025, 14, 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14020262. [CrossRef]

- Laspidou, C.S.; Mellios, N.; Kofinas, D. Towards Ranking the Water–Energy–Food–Land Use–Climate Nexus Interlinkages for Building a Nexus Conceptual Model with a Heuristic Algorithm. Water 2019, 11, 306. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11020306. [CrossRef]

- Terrapon-Pfaff, J.; Ortiz, W.; Dienst, C.; Gröne, M. C. Energising the WEF Nexus to enhance sustainable development at local level. J. of Env. Manag. 2018, 223, 409-416. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.06.037. [CrossRef]

- EU, (2022). EU supports integration of Water-Energy-Food Nexus approach into educational curricula in Tajikistan. Available online: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/delegations/tajikistan/eu-supports-integration-water-energy-food-nexus-approach-educational-1_en?s=228 (Accessed 08.02.2024).

- Benavides, L.; Avellán, T.; Caucci, S.; Hahn, A.; Kirschke, S.; Müller, A. Assessing Sustainability of Wastewater Management Systems in a Multi-Scalar, Transdisciplinary Manner in Latin America. Water 2019, 11, 249. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11020249. [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, M.P.; Vlachou, A. Conceptualization of NEXUS elements in the marine environment (Marine NEXUS). Euro-Mediterr. J. Environ. Integr. 7 2022, 399–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41207-022-00322-6. [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, A.; Aghababaei, F.; Pignitter, M.; Hadidi, M. Artificial Intelligence in Agro-Food Systems: From Farm to Fork. Foods 2025, 14, 411. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14030411. [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, A.E.; Laspidou, C.S. Cross-Mapping Important Interactions between Water-Energy-Food Nexus Indices and the SDGs. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8045. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108045. [CrossRef]

- Galic, M.; Bilandzija, D.; Percin, A.; Sestak, I.; Mesic, M.; Blazinkov, M.; Zgorelec, Z. Effects of Agricultural Practices on Carbon Emission and Soil Health. J. of Sust. Dev. of En. Wat. and Env. Syst, 2019 7 (3), 539-552. https://doi.org/10.13044/j.sdewes.d7.0271. [CrossRef]

- Malamataris, D.; Chatzi, A.; Babakos, K.; Pisinaras, V.; Hatzigiannakis, E.; Willaarts, B.A.; Bea, M.; Pagano, A.; Panagopoulos, A. A. Participatory Approach to Exploring Nexus Challenges: A Case Study on the Pinios River Basin, Greece. Water 2023, 15, 3949. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15223949. [CrossRef]

- Angelakis, A.; Manioudis, M.; Koskina, A. Τhe Political Economy of Green Transition: The Need for a Two-Pronged Approach to Address Climate Change and the Necessity of “Science Citizens”. Economies 2025, 13, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13020023. [CrossRef]

- International Standard Organization – ISO, ISO 14064-1:2018 Greenhouse gases Part 1: Specification with guidance at the organization level for quantification and reporting of greenhouse gas emissions and removals. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/66453.html (Accessed 10.12.2024.).

- International Standard Organization – ISO, ISO 14064-2:2019 Greenhouse gases Part 2: Specification with guidance at the project level for quantification, monitoring and reporting of greenhouse gas emission reductions or removal enhancements. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/66454.html (Accessed 10.12.2024.).

- International Standard Organization – ISO, ISO 14064-3:2019 Greenhouse gases Part 3: Specification with guidance for the verification and validation of greenhouse gas statements. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/66455.html (Accessed 10.12.2024.).

- Janaćković, G.; Vasović, D. Hybrid method for selection of optimal safety improvement strategy in micro-enterprises. FU Work. Liv. Env. Prot. 2023, 20(2), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.22190/FUWLEP2302077J. [CrossRef]

- Manumpil, F.E.; Utomo, S.W.; Koestoer, R.H.S.; Soesilo, T.E.B. Multicriteria Decision Making in Sustainable Tourism and Low-Carbon Tourism Research: A Systematic Literature Review. Tourism: An Internat. Interdisc. J. 2023, 71 (3), 447-471. https://doi.org/10.37741/t.71.3.2. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wei, M.; Gao, X. Modeling an Optimal Environmentally Friendly Energy-Saving Flexible Workshop. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11896. https://doi.org/10.3390/app132111896. [CrossRef]

- Knapp, F.; Šimon, M. Standardization of Project Management Practices of Automotive Industry Suppliers - Systematic Literature Review. Tech. Gazz. 2023, 17 (3), 432-439. https://doi.org/10.31803/tg-20230504094426. [CrossRef]

- Milone, M.; Mokkapaty, S. Harnessing the power of digitalization in the transformer industry for sustainability. Transf. Mag. 2023, 10 (SE2), 60-67. https://hrcak.srce.hr/309738.

- Blind, K. (2025). Standardization and Standards: Safeguards of Technological Sovereignty? Techn. Forec. and Soc. Chan. 2025, 210, 123873, ISSN 0040-1625, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2024.123873. [CrossRef]

- Marinović, M.; Viduka, D.; Lavrnić, I.; Stojčetović, B.; Skulić, A.; Bašić, A.; Balaban, P.; Rastovac, D. An Intelligent Multi-Criteria Decision Approach for Selecting the Optimal Operating System for Educational Environments. Electronics 2025, 14, 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14030514. [CrossRef]

- European Commission, 2022. An EU Strategy on Standardisation Setting global standards in support of a resilient, green and digital EU single market. Brussels, 2.2.2022 COM (2022). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52022DC0031 (Accessed 20.12.2024.).

- Dasallas, L.; Lee, J.; Jang, S.; Jang, S. Development and Application of Technical Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for Smart Water Cities (SWCs) Global Standards and Certification Schemes. Water 2024, 16, 741. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16050741. [CrossRef]

- International Standard Organization - ISO, 2017. ISO 14001:2015 - Environmental management systems - A practical guide for SMEs. Available online: https://www.iso.org/publication/PUB100411.html (Accessed 16.12.2024.).

- Sušnik, J.; Chew, C.; Domingo, X.; Mereu, S.; Trabucco, A.; Evans, B.; Vamvakeridou-Lyroudia, L.; Savić, DA.; Laspidou, C.; Brouwer F. Multi-Stakeholder Development of a Serious Game to Explore the Water-Energy-Food-Land-Climate Nexus: The SIM4NEXUS Approach. Water 2018, 10 (2):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10020139. [CrossRef]

- International Standard Organization – ISO, ISO 22000:2018 Food safety management systems Requirements for any organization in the food chain. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/65464.html (Accessed 15.12.2024.).

- International Standard Organization – ISO, ISO 14067:2018 Greenhouse gases Carbon footprint of products Requirements and guidelines for quantification. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/71206.html (Accessed 17.12.2024.).

- Jiali, M.; Ting, L.; Maqbool, A. Environmental higher education-renewable energy consumption nexus in China: pathways toward carbon neutrality. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023 30, 102260–102270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-29261-7. [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, C.-A.; Papadopoulou, M.P.; Laspidou, C.; Munaretto, S.; Brouwer, F. Towards a Low-Carbon Economy: A Nexus-Oriented Policy Coherence Analysis in Greece. Sustainability 2020, 12, 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010373. [CrossRef]

- Barreca, F. Sustainability in Food Production: A High-Efficiency Offshore Greenhouse. Agronomy 2024, 14, 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14030518. [CrossRef]

- Cano, N.; Berrio, L.; Carvajal, E.; Arango, S. Assessing the carbon footprint of a Colombian University Campus using the UNE-ISO 14064–1 and WRI/WBCSD GHG Protocol Corporate Standard. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 3980–3996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-22119-4. [CrossRef]

- International Standard Organization – ISO, ISO Survey data. Available online: https://www.iso.org/the-iso-survey.html (Accessed 15.12.2024.).

- Eurostat (2023), National accounts and GDP. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=National_accounts_and_GDP (Accessed 20.12.2024.).

- Eurostat (2023), Population and population change statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Population_and_population_change_statistics (Accessed 22.12.2024.).

- Vranjanac, Ž.; Rađenović, Ž.; Rađenović, T.; Živković, S. Modelling circular economy innovation and performance indicators in European Union countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 81573–81584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-26431-5. [CrossRef]

- Vranjanac, Ž.; Vasović, D.; Janaćković, G.; Živković, N.; Malenović-Nikolić, J. Comparative Analysis of Selected Environmental Indicators within Adjusted Savings in Serbia and Romania. J. Env. Protec. Ecol. 2019, 20 (2), 906–911.

- Bulut, E.; Duru, O.; Keçeci, T.; Yoshida, S. Use of consistency index, expert prioritization and direct numerical inputs for generic fuzzy-AHP modeling: A process model for shipping asset management. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2012, 39(2),1911–1123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2011.08.056. [CrossRef]

- European IPPC Bureau – EIPPCB, Best Available Techniques (BAT) Reference Document for the Food, Drink and Milk Industries. Available online: https://eippcb.jrc.ec.europa.eu/reference (Accessed 23.12.2024.).

- Laspidou, C.S.; Mellios, N.K.; Spyropoulou, A.E.; Kofinas, D.T.; Papadopoulou, M.P. Systems thinking on the resource nexus: Modeling and visualisation tools to identify critical interlinkages for resilient and sustainable societies and institutions. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 717, 137264.

- Ioannou, A.E.; Laspidou, C.S. Resilience Analysis Framework for a Water–Energy–Food Nexus System Under Climate Change. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 820125.

- Radojković, I.; Milosavljević, P.; Janaćković, G.; Grozdanović, M. The key risk indicators of road traffic crashes in Serbia, Niš region. Int. J. In.j Contr. Saf. Promot. 2019, 26 (1), 45–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457300.2018.1476384. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).