Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

24 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

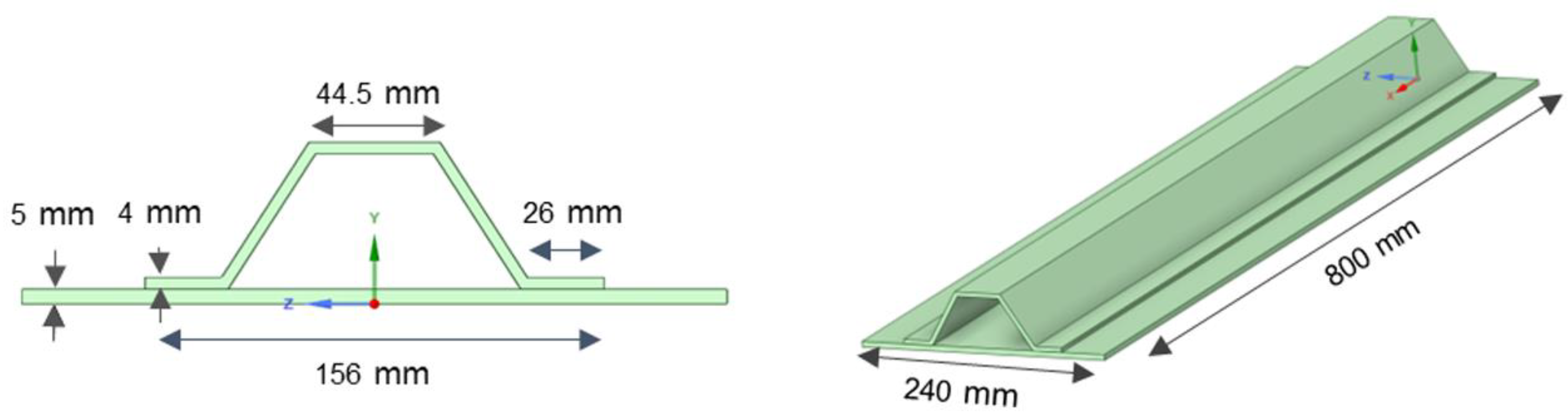

2. Dataset – Exploited Use Case for Sustainability Evaluation

3. Methodology

3.1. MCDM Methods Considered

3.1.1. Weighted Sum Method (WSM)

3.1.2. Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to an Ideal Solution (TOPSIS).

3.1.3. Modified TOPSIS

3.1.4. VIKOR

3.1.5. COPRAS

3.2. Normalization Methods

4. Results

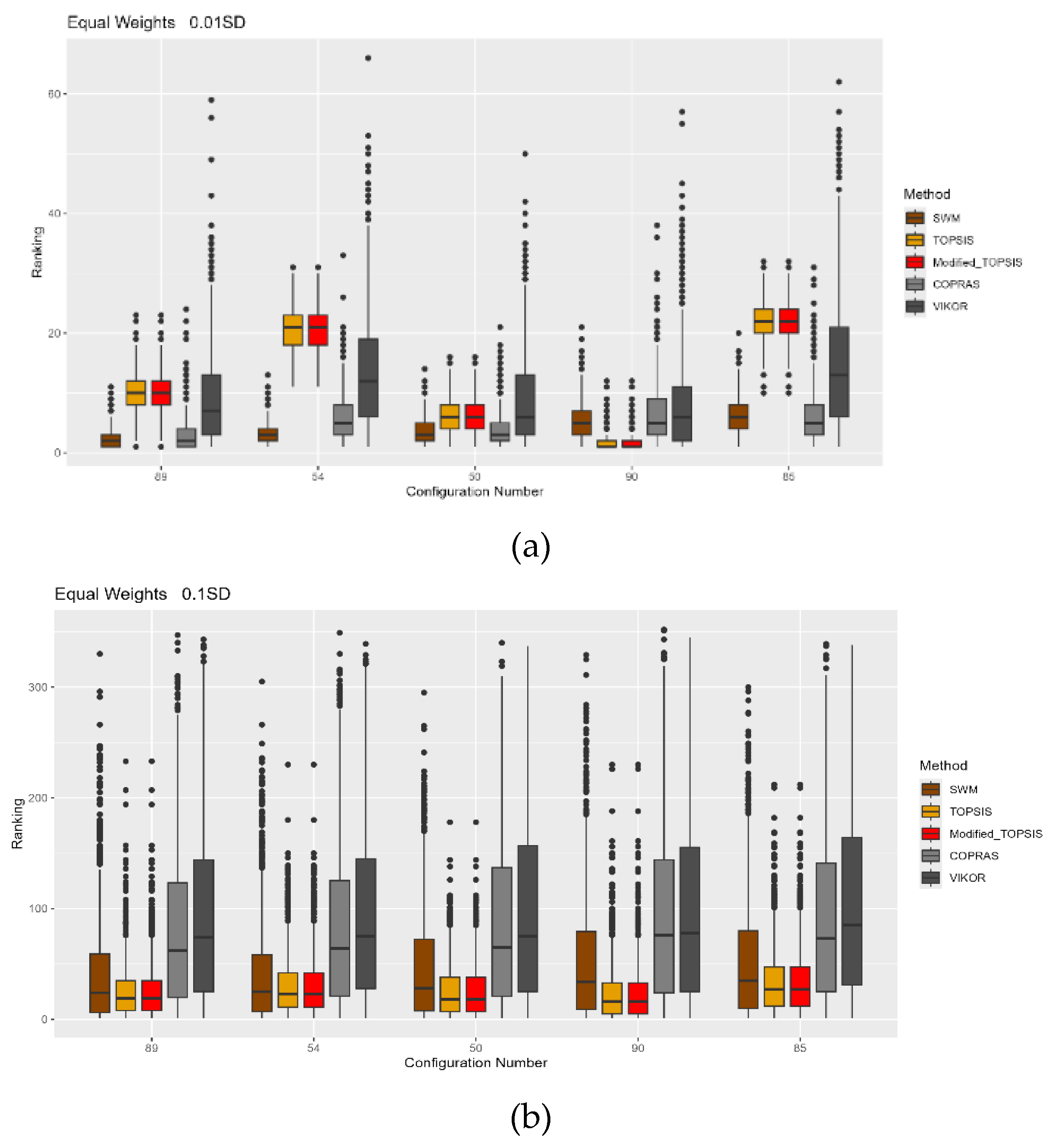

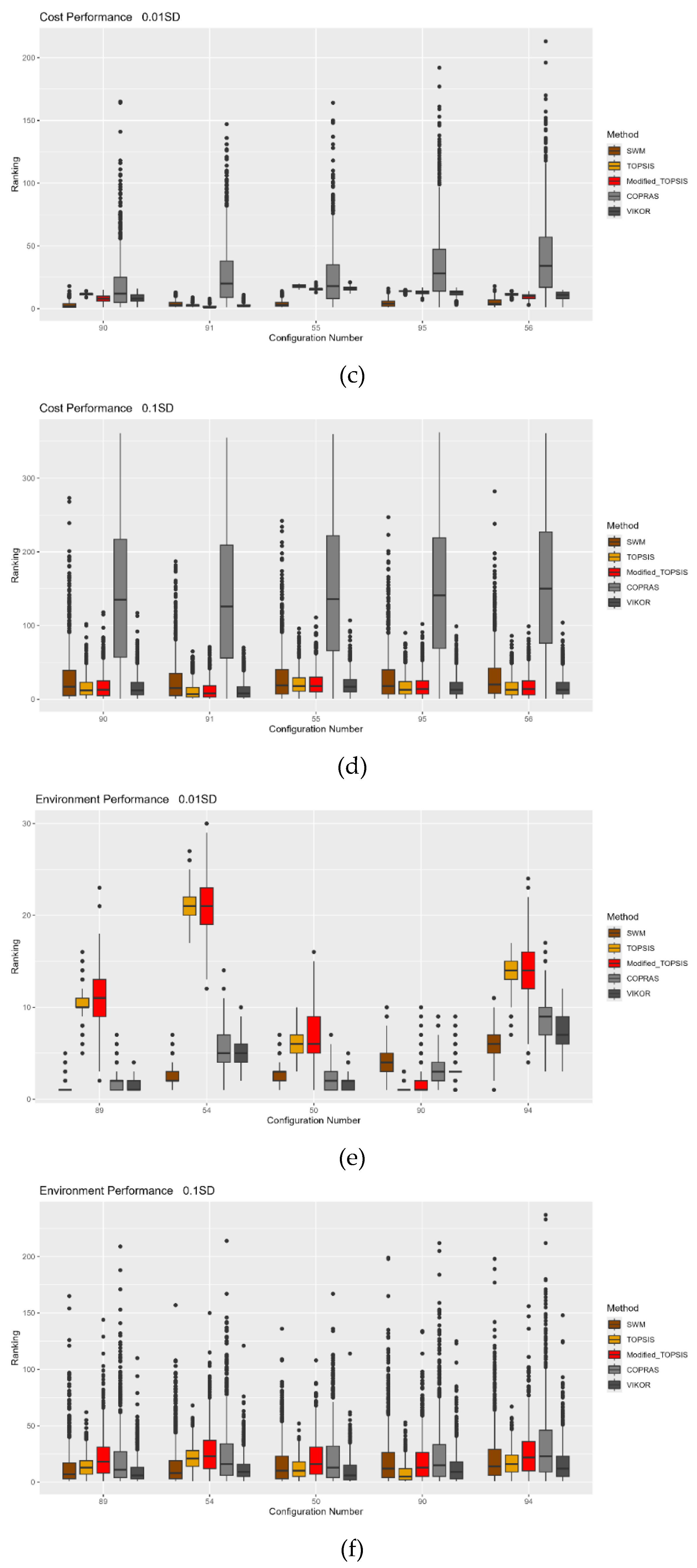

4.1. MCDM Impact Results

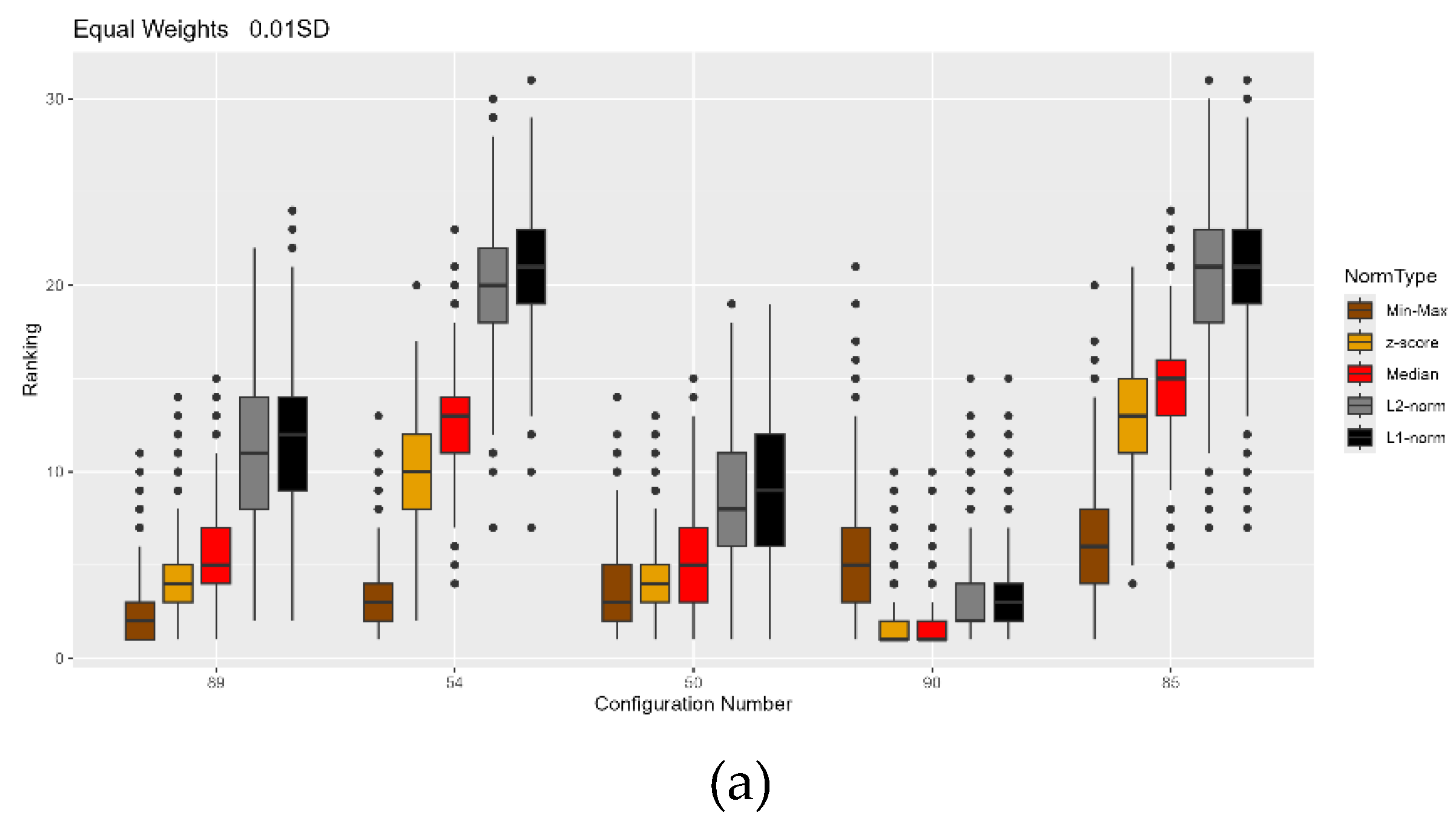

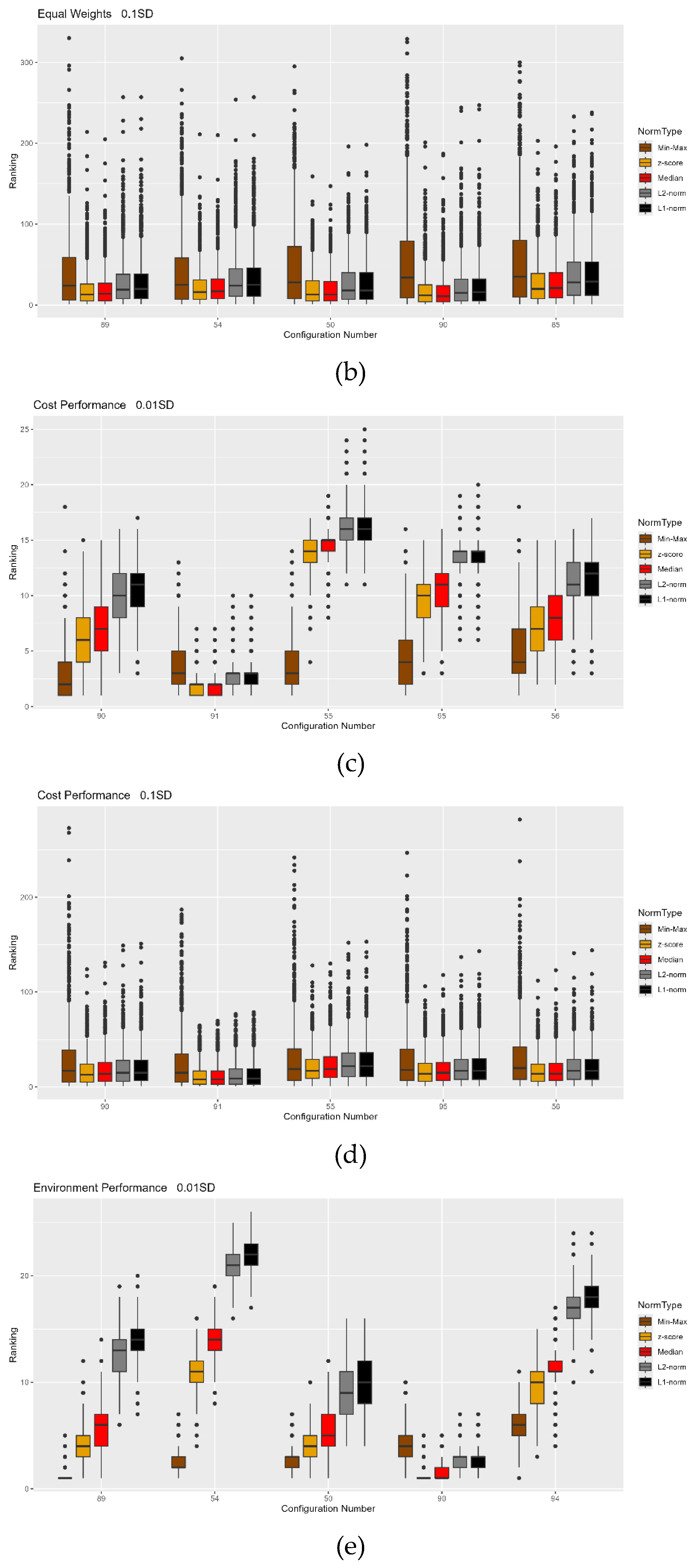

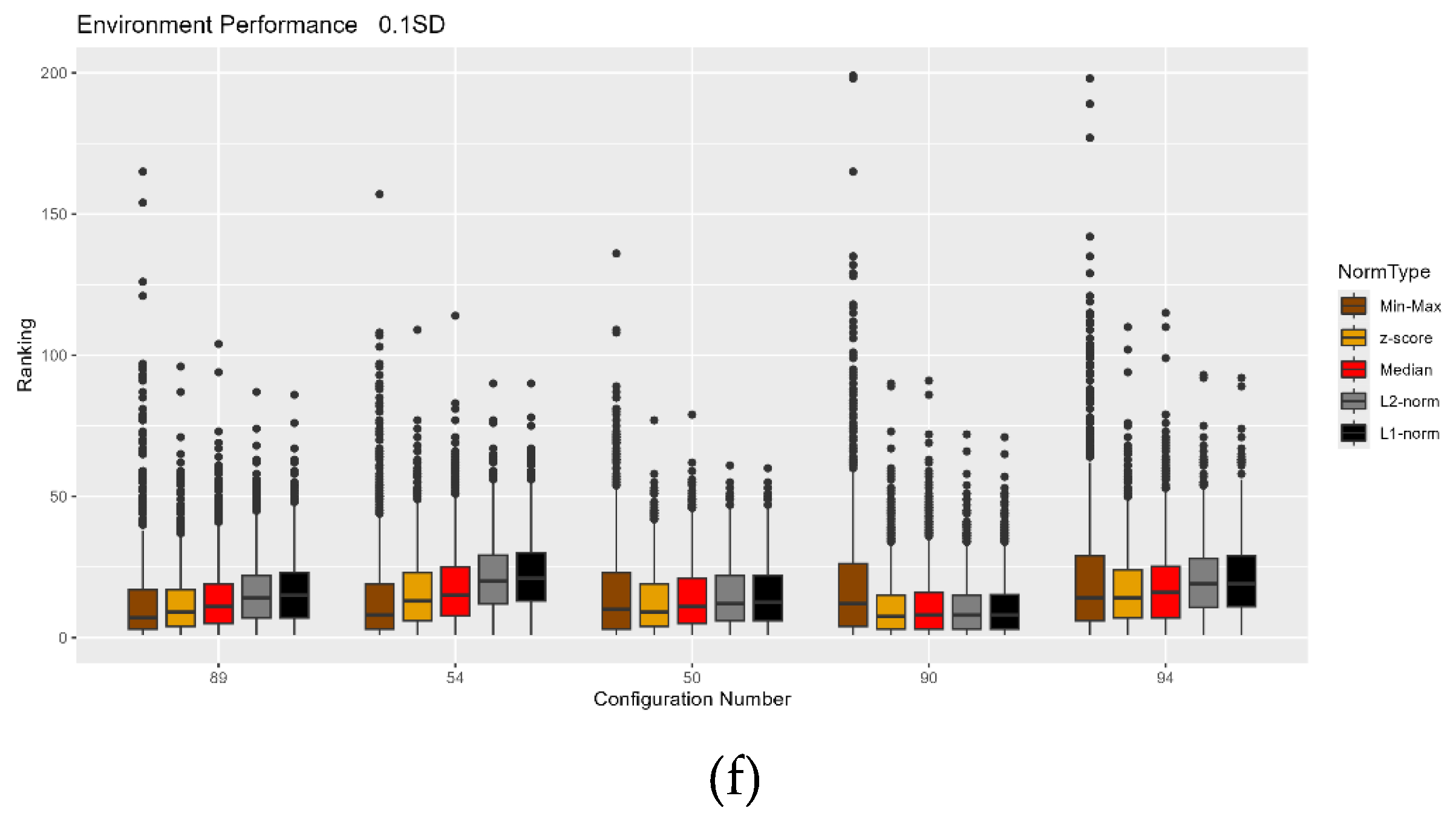

4.2. Normalization Impact Results

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Acknowledgments

References

- G. P. Bhole. MultiCriteria Decision Making (MCDM) Methods and its applications. Int J Res Appl Sci Eng Technol 2018, 6, 899–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Harirchian, K. Jadhav, K. Mohammad, S. E. A. Hosseini, and T. Lahmer. A Comparative Study of MCDM Methods Integrated with Rapid Visual Seismic Vulnerability Assessment of Existing RC Structures. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 6411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, Y. Peng, G. Tian, D. Wang, and P. Xie. Green material selection for sustainability: A hybrid MCDM approach. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0177578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Żak, Y. J. Żak, Y. Hadas, and R. Rossi, Eds.. Advanced Concepts, Methodologies and Technologies for Transportation and Logistics. vol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Santos, J. C. O. Matias, and A. Abreu. A Decision-Making Tool to Provide Sustainable Solutions to a Consumer. IFIP Adv Inf Commun Technol 2020, 577, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Streimikiene, T. Balezentis, I. Krisciukaitien, and A. Balezentis. Prioritizing sustainable electricity production technologies: MCDM approach. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012, 16, 3302–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. . A review of multi criteria decision making (MCDM) towards sustainable renewable energy development. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 69, 596–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindfors. Assessing sustainability with multi-criteria methods: A methodologically focused literature review. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators 2021, 12, 100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Dožić. Multi-criteria decision making methods: Application in the aviation industry. J Air Transp Manag 2019, 79, 101683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. R. Elhmoud and A. A. Kutty. Sustainability Assessment in Aviation Industry: A Mini- Review on the Tools, Models and Methods of Assessment. 2020, Accessed: Dec. 08, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://qspace.qu.edu. 1057.

- K. Kiracı and E. Akan. Aircraft selection by applying AHP and TOPSIS in interval type-2 fuzzy sets. J Air Transp Manag 2020, 89, 101924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bağcı and, M. Kartal. A combined multi criteria model for aircraft selection problem in airlines. J Air Transp Manag 2024, 116, 102566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Dožić and M. Kalić. Comparison of Two MCDM Methodologies in Aircraft Type Selection Problem. Transportation Research Procedia 2015, 10, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardil. Commercial Aircraft Selection Decision Support Model Using Fuzzy Combinative Multiple Criteria Decision Making Analysis. Journal of Sustainable Manufacturing in Transportation, 2023; 2. [CrossRef]

- N. Markatos and S. G. Pantelakis. Implementation of a Holistic MCDM-Based Approach to Assess and Compare Aircraft, under the Prism of Sustainable Aviation. Aerospace 2023, 10, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. T. Lu, C. C. Hsu, J. J. H. Liou, and H. W. Lo. A hybrid MCDM and sustainability-balanced scorecard model to establish sustainable performance evaluation for international airports. J Air Transp Manag 2018, 71, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Janic and A. Reggiani. An Application of the Multiple Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) Analysis to the Selection of a New Hub Airport. European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research. [CrossRef]

- N. Chai and W. Zhou. A novel hybrid MCDM approach for selecting sustainable alternative aviation fuels in supply chain management. Fuel 2022, 327, 125180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Chen and J. Ren. Multi-attribute sustainability evaluation of alternative aviation fuels based on fuzzy ANP and fuzzy grey relational analysis. J Air Transp Manag 2018, 68, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Singh, S. Rana, A. B. Abdul Hamid, and P. Gupta. Who should hold the baton of aviation sustainability? Social Responsibility Journal 2023, 19, 1161–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Chatterjee and S. Chakraborty. Flexible manufacturing system selection using preference ranking methods: A comparative study. International Journal of Industrial Engineering Computations 2014, 5, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytekin. Comparative Analysis of the Normalization Techniques in the Context of MCDM Problems. Decision Making: Applications in Management and Engineering 2021, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Jafaryeganeh, M. Ventura, and C. Guedes Soares. Effect of normalization techniques in multi-criteria decision making methods for the design of ship internal layout from a Pareto optimal set. Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 2020, 62, 1849–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. T. Mhlanga and M. Lall. Influence of Normalization Techniques on Multi-criteria Decision-making Methods. J Phys Conf Ser 2022, 2224, 012076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Vafaei, R. A. Ribeiro, and L. M. Camarinha-Matos. Assessing Normalization Techniques for Simple Additive Weighting Method. Procedia Comput Sci 2022, 199, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacprzak. A new similarity measure for rankings obtained in MCDM problems using different normalization techniques. Operations Research and Decisions 2024, 34, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Kosareva, A. Krylovas, and E. K. Zavadskas. Statistical analysis of MCDM data normalization methods using Monte Carlo approach. The case of ternary estimates matrix. Econ Comput Econ Cybern Stud Res 2018, 52, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. T. Do, V. D. D. T. Do, V. D. Tran, V. D. Duong, and N.-T. Nguyen. Investigation of the Appropriate Data Normalization Method for Combination with Preference Selection Index Method in MCDM. Operational Research in Engineering Sciences: Theory and Applications, 2023; 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Mukhametzyanov. Normalization of Multidimensional Data for Multi-Criteria Decision Making Problems. vol. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Vafaei, R. A. N. Vafaei, R. A. Ribeiro, and L. M. Camarinha-Matos. Comparison of Normalization Techniques on Data Sets With Outliers. https://services.igi-global.com/resolvedoi/resolve.aspx?doi=10.4018/IJDSST.286184, 1. [CrossRef]

- D. D. Trung. Development of data normalization methods for multi-criteria decision making: applying for MARCOS method. Manuf Rev (Les Ulis) 2022, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Upadhyay. Effect Of Normalization Techniques In Robot Selection Using Weighted Aggregated Sum Product Assessment. 2017.

- T. M. Lakshmi and V. P. Venkatesan. A Comparison Of Various Normalization In Techniques For Order Performance By Similarity To Ideal Solution (topsis). International Journal of Computing Algorithm, /: Dec. 2014, Accessed: Dec. 08, 2024. [Online]. Available: http, 2014; 08.

- D. N. Markatos, S. Malefaki, and S. G. Pantelakis. Sensitivity Analysis of a Hybrid MCDM Model for Sustainability Assessment—An Example from the Aviation Industry. Aerospace 2023, 10, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Ardil. Aircraft Selection Using Multiple Criteria Decision Making Analysis Method with Different Data Normalization Techniques. International Journal of Industrial and Systems Engineering, /: Accessed: Dec. 08, 2024. [Online]. Available: https, 2019; 08.

- Angelos Filippatos, D. N. Markatos, Athina Theochari, Sonia Malefaki, Thomas Kalampoukas & S.G. Pantelakis ‘‘A proposal towards a step change from eco-driven to sustainability-driven design of aircraft components.” In: Proceedings of the ICAS 2024 Conference, Florence, Italy [Online] Available: https://www.researchgate. 3852. [Google Scholar]

- D. N. Markatos and S. G. Pantelakis. Assessment of the Impact of Material Selection on Aviation Sustainability, from a Circular Economy Perspective. Aerospace, 2022; 2. [CrossRef]

- Filippatos, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. . Sustainability-Driven Design of Aircraft Composite Components. Aerospace, 2024; 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. C. Fishburn. Letter to the Editor—Additive Utilities with Incomplete Product Sets: Application to Priorities and Assignments. 1967, 15, 537–542. [CrossRef]

- T. Saaty. The analytic hierarchy process: Planning, priority setting, resource allocation: Thomas L. SAATY McGraw-Hill, New York, 1980, xiii. Eur J Oper Res 1980, 9, 97–98. [Google Scholar]

- T. L. Saaty. A scaling method for priorities in hierarchical structures. J Math Psychol 1977, 15, 234–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. L. Saaty. How to make a decision: The analytic hierarchy process. Eur J Oper Res 1990, 48, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C.-L. Hwang and K. Yoon. Multiple Attribute Decision Making. vol. 1981. [CrossRef]

- Ciardiello and, A. Genovese. A comparison between TOPSIS and SAW methods. Ann Oper Res 2023, 325, 967–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akay and, M. Baduna Koçyiğit. Investigation of Flood Hazard Susceptibility Using Various Distance Measures in Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 7023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. S. García-Cascales and M. T. Lamata. On rank reversal and TOPSIS method. Math Comput Model, 2012; 6. [CrossRef]

- H.-J. Shyur and H.-S. Shih. Resolving Rank Reversal in TOPSIS: A Comprehensive Analysis of Distance Metrics and Normalization Methods. Informatica, 2024; 4. [CrossRef]

- Deng, C. H. Yeh, and R. J. Willis. Inter-company comparison using modified TOPSIS with objective weights. Comput Oper Res, 2000; 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Opricovic, S. (1998) Multicriteria Optimization of Civil Engineering Systems. PhD Thesis, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Belgrade, 302 p. - References - Scientific Research Publishing.” Accessed: Dec. 11, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- L. Duckstein and S. Opricovic. Multiobjective optimization in river basin development. Water Resour Res, 1980; 1. [CrossRef]

- S. Opricovic and G. H. Tzeng. Multicriteria Planning of Post-Earthquake Sustainable Reconstruction. Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering 2002, 17, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E.K. Zavadskas, A. E.K. Zavadskas, A. Kaklauskas, & V. Šarka (1994). The new method of multicriteria complex proportional assessment of projects. “The new method of multicriteria complex proportional assessment of projects.

- L. Kraujalienė. Comparative analysis of multicriteria decision-making methods evaluating the efficiency of technology transfer. Business, Management and Economics Engineering, 2019; 1. [CrossRef]

- R. Krishnan. Past efforts in determining suitable normalization methods for multi-criteria decision-making: A short survey. Front Big Data 2022, 5, 990699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component Configurations | ||

|---|---|---|

| No | Skin | Stringer |

| 1 | Aluminium 2024 T3 | Aluminium 2024 T3 |

| 2 | CFRP | Aluminium 2024 T3 |

| 3 | Aluminium 2024 T3 | CFRP |

| 4 | CFRP | CFRP |

| 5 | 17-4PH Stainless Steel | CFRP |

| Method | for the attribute that needs to be maximized | for the attribute that need to be minimized |

|---|---|---|

| Min -Max | ||

| Z -score | ||

| Robust scaling | ||

| L1 – norm | ||

| L2 – norm |

| Ranking No | Material Combination | SWM | TOPSIS | Modified TOPSIS | COPRAS | VIKOR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equal Weighting | ||||||

| 1 | AL-AL | 89 | 90 | 90 | 89 | 90 |

| 2 | AL-AL | 54 | 51 | 51 | 50 | 50 |

| 3 | AL-AL | 50 | 91 | 91 | 85 | 91 |

| 4 | AL-AL | 90 | 52 | 52 | 90 | 89 |

| 5 | AL-AL | 85 | 50 | 50 | 54 | 51 |

| 6 | AL-AL | 94 | 55 | 55 | 46 | 55 |

| 7 | AL-AL | 55 | 95 | 95 | 51 | 52 |

| 8 | AL-AL | 123 | 56 | 56 | 123 | 92 |

| 9 | AL-AL | 51 | 92 | 92 | 94 | 54 |

| 10 | AL-AL | 128 | 89 | 89 | 55 | 85 |

| Prioritization to Performance and Costs Terms | ||||||

| Ranking No | Material Combination | SWM | TOPSIS | Mod. TOPSIS | COPRAS | VIKOR |

| 1 | AL-AL | 90 | 92 | 91 | 89 | 92 |

| 2 | AL-AL | 91 | 93 | 92 | 50 | 93 |

| 3 | AL-AL | 55 | 91 | 93 | 85 | 91 |

| 4 | AL-AL | 95 | 97 | 52 | 54 | 52 |

| 5 | AL-AL | 56 | 98 | 96 | 90 | 97 |

| 6 | AL-AL | 94 | 53 | 53 | 46 | 53 |

| 7 | AL-AL | 96 | 52 | 97 | 51 | 96 |

| 8 | AL-AL | 51 | 96 | 57 | 123 | 90 |

| 9 | AL-AL | 89 | 57 | 90 | 94 | 57 |

| 10 | AL-AL | 92 | 58 | 56 | 55 | 98 |

| Prioritization to Performance and Environment Terms | ||||||

| Ranking No | Material Combination | SWM | TOPSIS | Mod. TOPSIS | COPRAS | VIKOR |

| 1 | AL-AL | 89 | 90 | 90 | 89 | 89 |

| 2 | AL-AL | 54 | 51 | 91 | 50 | 50 |

| 3 | AL-AL | 50 | 91 | 51 | 90 | 90 |

| 4 | AL-AL | 90 | 52 | 52 | 85 | 54 |

| 5 | AL-AL | 94 | 50 | 50 | 51 | 85 |

| 6 | AL-AL | 85 | 55 | 55 | 54 | 51 |

| 7 | AL-AL | 55 | 95 | 95 | 91 | 94 |

| 8 | AL-AL | 123 | 56 | 56 | 55 | 55 |

| 9 | AL-AL | 51 | 92 | 92 | 94 | 86 |

| 10 | AL-AL | 128 | 89 | 89 | 86 | 91 |

| Aggregation Method | SWM | TOPSIS | Modified TOPSIS | COPRAS | VIKOR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equal Weights | |||||||

| SWM | 1 | 0.866 | 0.866 | 0.958 | 0.948 | ||

| TOPSIS | 0.866 | 1 | 1 | 0.943 | 0.869 | ||

| Modified TOPSIS | 0.866 | 1 | 1 | 0.943 | 0.869 | ||

| COPRAS | 0.958 | 0.943 | 0.943 | 1 | 0.976 | ||

| VIKOR | 0.948 | 0.869 | 0.869 | 0.976 | 1 | ||

| Prioritization to Performance and Environment Terms | |||||||

| SWM | 1 | 0.856 | 0.890 | 0.898 | 0.941 | ||

| TOPSIS | 0.856 | 1 | 0.932 | 0.912 | 0.886 | ||

| Modified TOPSIS | 0.890 | 0.932 | 1 | 0.976 | 0.853 | ||

| COPRAS | 0.898 | 0.912 | 0.976 | 1 | 0.854 | ||

| VIKOR | 0.941 | 0.886 | 0.853 | 0.854 | 1 | ||

| Prioritization to Performance and Costs Terms | |||||||

| SWM | 1 | 0.908 | 0.923 | 0.931 | 0.917 | ||

| TOPSIS | 0.908 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.826 | 0.987 | ||

| Modified TOPSIS | 0.923 | 0.999 | 1 | 0.843 | 0.988 | ||

| COPRAS | 0.931 | 0.826 | 0.843 | 1 | 0.809 | ||

| VIKOR | 0.917 | 0.987 | 0.988 | 0.809 | 1 | ||

| Ranking No | Material | Min - Max | z -score | Median | L2 - Norm | L1 - Norm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equal Weighting | ||||||

| 1 | AL-AL | 89 | 90 | 90 | 91 | 91 |

| 2 | AL-AL | 54 | 91 | 91 | 90 | 90 |

| 3 | AL-AL | 50 | 50 | 51 | 92 | 92 |

| 4 | AL-AL | 90 | 89 | 50 | 51 | 51 |

| 5 | AL-AL | 85 | 51 | 89 | 52 | 52 |

| 6 | AL-AL | 94 | 55 | 55 | 50 | 93 |

| 7 | AL-AL | 55 | 95 | 92 | 56 | 56 |

| 8 | AL-AL | 123 | 56 | 95 | 93 | 50 |

| 9 | AL-AL | 51 | 94 | 56 | 95 | 96 |

| 10 | AL-AL | 128 | 92 | 52 | 96 | 95 |

| Prioritization to Performance and Costs Terms | ||||||

| 1 | AL-AL | 90 | 92 | 92 | 92 | 92 |

| 2 | AL-AL | 91 | 91 | 91 | 93 | 93 |

| 3 | AL-AL | 55 | 93 | 93 | 91 | 91 |

| 4 | AL-AL | 95 | 96 | 96 | 97 | 97 |

| 5 | AL-AL | 56 | 90 | 97 | 52 | 53 |

| 6 | AL-AL | 94 | 97 | 57 | 53 | 52 |

| 7 | AL-AL | 96 | 56 | 90 | 96 | 98 |

| 8 | AL-AL | 51 | 57 | 52 | 98 | 96 |

| 9 | AL-AL | 89 | 52 | 56 | 57 | 57 |

| 10 | AL-AL | 92 | 95 | 95 | 58 | 58 |

| Prioritization to Performance and Environment Terms | ||||||

| 1 | AL-AL | 89 | 90 | 90 | 91 | 91 |

| 2 | AL-AL | 54 | 91 | 91 | 92 | 92 |

| 3 | AL-AL | 50 | 51 | 51 | 90 | 90 |

| 4 | AL-AL | 90 | 50 | 50 | 51 | 51 |

| 5 | AL-AL | 94 | 89 | 89 | 52 | 52 |

| 6 | AL-AL | 85 | 55 | 92 | 93 | 93 |

| 7 | AL-AL | 55 | 95 | 55 | 56 | 56 |

| 8 | AL-AL | 123 | 56 | 95 | 50 | 96 |

| 9 | AL-AL | 51 | 92 | 56 | 96 | 95 |

| 10 | AL-AL | 128 | 94 | 52 | 95 | 50 |

| Normalization Method |

Min - Max | z-score | Median | L2 - Norm | L1 - Norm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equal Weights | |||||

| Min - Max | 1 | 0.947 | 0.892 | 0.946 | 0.942 |

| z -score | 0.947 | 1 | 0.990 | 0.996 | 0.996 |

| Median | 0.892 | 0.990 | 1 | 0.983 | 0.984 |

| L2 - Norm | 0.946 | 0.996 | 0.983 | 1 | 1 |

| L1 - norm | 0.942 | 0.996 | 0.984 | 1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).