4. Discussion

The retrospective study conducted on equine gas gangrene in the Amazon Biome, which involved the analysis of 20 horses almost a decade, offers critical insights into the prevalence, risk factors and impact of

C. septicum as the causative agent. Although in horses the disease is most often caused by

C. perfringens type A [

2,

3,

6,

7,

10,

14,

15,

17,

18,

21,

24], sporadic cases associated with other clostridial species have been described, such as

C. septicum, but never described in the Amazon Biome and only two case reports in all Brazil [

19,

27]. All the horses studied died to gas gangrene, underscoring the severe nature of the disease and the rapid progression that leads to high mortality rates. The exclusive identification of

C. septicum through PCR in these cases is particularly noteworthy, as it suggests a strong regional association of this pathogen with gas gangrene in horses. This finding raises important considerations for both diagnostic approaches and preventive strategies tailored to the Amazon Biome. Gas gangrene in horses is a severe and often fatal condition that requires immediate veterinary intervention. The disease’s rapid progression and the nonspecific nature of early signs make early diagnosis and treatment challenging, underscoring the importance of preventive measures, such as vaccination [

18,

22,

23], the main prevention measure, particularly in high-risk regions like the Amazon Biome. Understanding the epidemiological factors and clinical presentation of gas gangrene is crucial for effective management and improving the prognosis for affected horses.

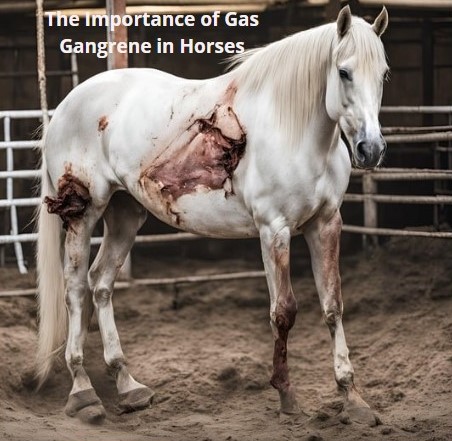

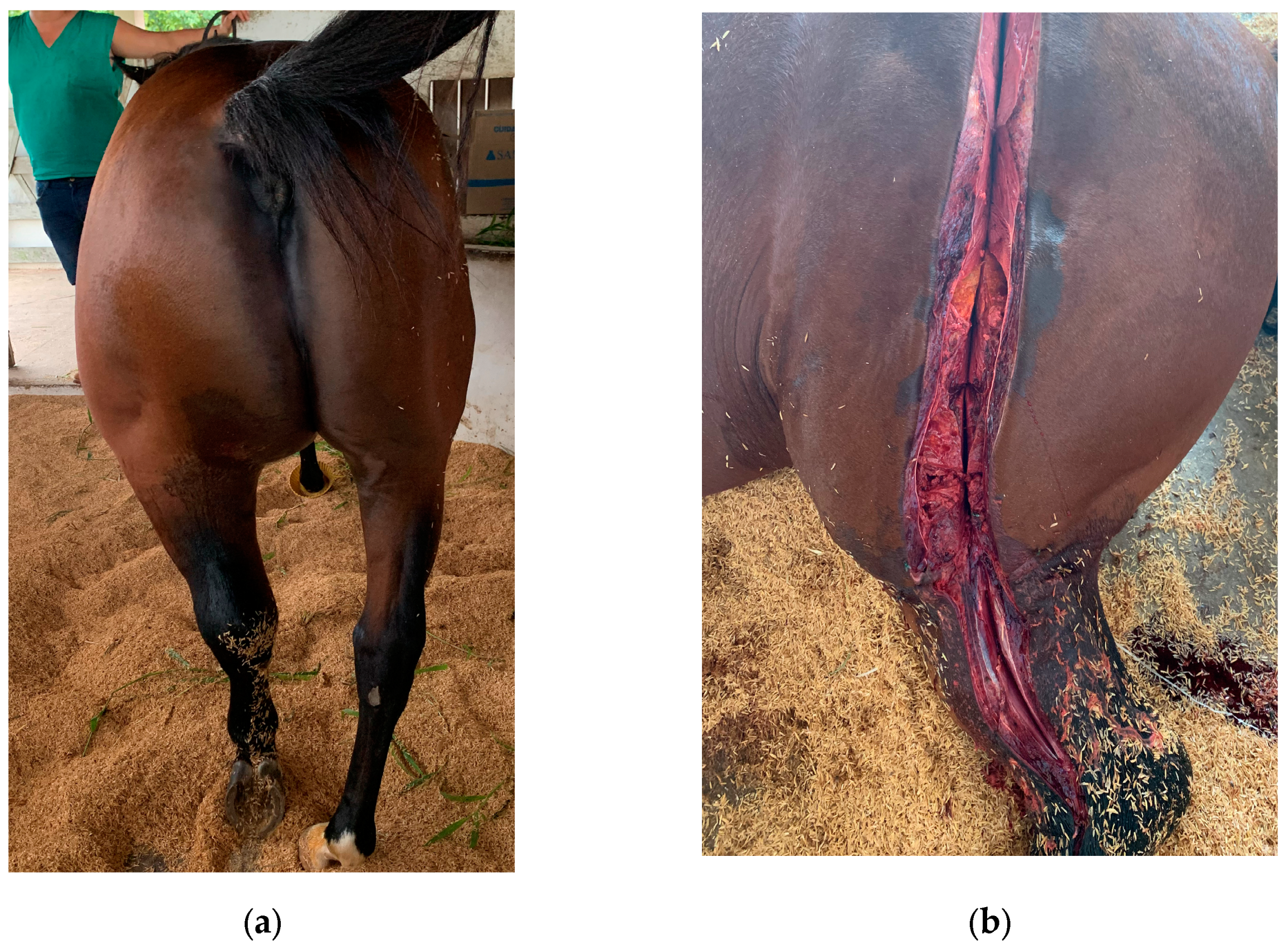

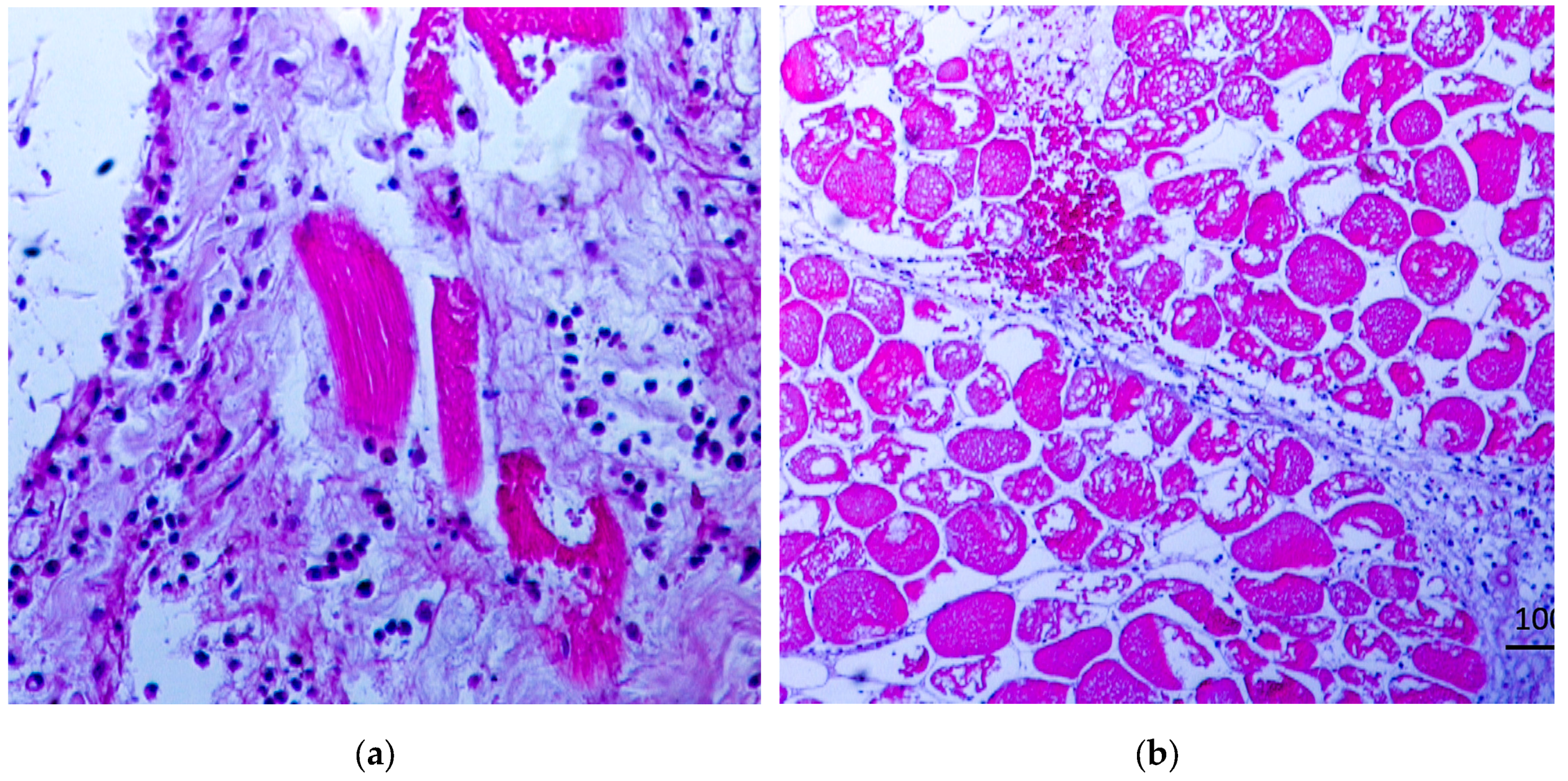

Gas gangrene causes characteristic anatomical and histopathological changes, which can be observed during post-mortem examinations or from biopsy samples [

5,

6]. In this study and in the literature [

2,

4,

6,

7,

13] the affected muscles are typically swollen, dark, and friable, with extensive necrosis. There has gas bubbles within the muscle tissue, giving it a “bubble wrap” appearance on palpation. The necrotic tissue exudes a foul-smelling, dark, serosanguineous fluid. The odor is typically pungent due to the anaerobic metabolism of

Clostridium bacteria [

6]. Gas production by the bacteria leads to subcutaneous emphysema, with palpable crepitus in the overlying skin. This can extend over a significant area of the body, depending on the severity and extent of the infection as observed in the 20 animals. Extensive edema is often present, not only in the affected muscles but also in the surrounding tissues. This edema contributes to circulatory impairment and further tissue damage [

15]. The disease progresses quickly, often within hours of infection [

14]. The affected area typically presents with severe pain, swelling, and edema. The swelling may rapidly increase in size and is often warm to the touch. The skin over the affected area may change color, becoming pale, reddish, or darkened as the tissue becomes necrotic [

24]. As the infection progresses, horses develop a high fever and an elevated heart rate. The horse becomes increasingly lethargic, weak, and reluctant to move due to the severe pain and systemic effects of the toxins [

15]. Systemic toxemia leads to multi-organ failure. The disease can progress rapidly to systemic toxemia, sepsis, and death within 24-48 hours if not treated aggressively [

6] which was done in the animals in the present study, but because they were not vaccinated, they all died, demonstrating the importance of vaccination in horses against clostridial diseases. In many cases, the progression of gas gangrene is so swift that death occurs before treatment can be effectively administered [

18]. The importance of this disease for equine health cannot be overstated, particularly in regions like the Amazon Biome where environmental conditions favor the proliferation of clostridial bacteria, such as

C. septicum. The study highlights the critical need for increased awareness, diagnostic capabilities, and preventive measures to mitigate the impact of this devastating disease on equine populations. In equines, the disease’s rapid progression often leaves little time for effective intervention, underscoring the necessity for early detection and treatment, which are currently hampered by a lack of data and awareness among veterinarians and horse owners in the region [

6,

16,

21].

The only detection of

C. septicum across all cases indicates that this pathogen may have a unique niche in the Amazon Biome, where environmental factors such as high humidity, warm temperatures, and organic-rich soils create ideal conditions for its survival and proliferation. Unlike other clostridial species, which are often more commonly associated with gas gangrene in temperate climates [

6,

11,

13,

14,

17],

C. septicum appears to dominate in this tropical region. This dominance could be due to the bacterium’s ability to thrive in anaerobic conditions that are more prevalent in the warm, moist environment of the Amazon. Furthermore, the rapid onset of gas gangrene symptoms following trauma or other predisposing factors in these horses highlights the need for immediate intervention upon the first signs of the disease [

13,

14,

15]. Contaminated wounds, particularly deep puncture wounds, surgical sites, or areas of tissue necrosis, are the most common associations with the disease. Gas gangrene in horses is reported worldwide but is particularly prevalent in regions where the bacterium’s spores are common in the soil, such as tropical and subtropical areas [

6,

7]. The Amazon Biome, with its warm and humid environment, provides ideal conditions for the proliferation of clostridial spores, making horses in this region particularly susceptible.

The incidence of gas gangrene in horses tends to increase during wet seasons, when the soil is more likely to harbor clostridial spores, and horses are more prone to injuries from working in muddy or uneven terrain [

3,

6,

27]. Horses that suffer from penetrating injuries, particularly those involving muscle tissue, are at high risk for gas gangrene. Additionally, surgical procedures, injections with contaminated needles, or even parturition can create favorable conditions for infection. Poor hygiene, inadequate wound care, and inadequate management of surgical sites increase the likelihood of infection [

6,

7,

15]. While the exact incidence of gas gangrene in horses is difficult to determine due to underreporting, it is recognized as a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in horses, particularly in areas with endemic clostridial spores. In this present retrospective study the main predisposing factors observed were the reuse of needles, use of contaminated surgical instruments, sharp tree stumps and barbed wire fences in pastures have also been observed to possibly cause skin lacerations, as have spurs used by riders inflicting puncture wounds . However, the biggest and most important problem observed was lack of vaccination, the main isolated prevention measure against any clostridial disease.

The implications of this study are significant when compared to other Brazilian and global studies on clostridial infections [

3,

10,

11,

12,

14,

15,

17,

20]. While

C. perfringens type A,

C. novy type A

C. sordelli,

C. chauvoei are often reported as primary agents of gas gangrene in livestock worldwide [

2,

4,

7], the predominance of

C. septicum in this study suggests a region-specific pathogen profile in the Amazon Biome. This contrasts with findings from other regions where different species of

Clostridium are more prevalent. For example, in Brazil [

3,

10,

19,

27] and other parts of the world [

11,

12,

15,

24,

25],

C. septicum is not frequently implicated in clostridial myonecrosis. However, the Amazon’s unique ecological conditions appear to select for

C. septicum, making it the leading cause of gas gangrene in horses in this area.

The high mortality rate observed in this study highlights the critical need for more effective prevention and control measures [

2,

4,

21,

22,

23]. Current strategies, including vaccination, have not been fully developed or implemented for

C. septicumin equines, particularly in the Amazon Biome. Given the rapid progression of gas gangrene and the high mortality associated with

C. septicum infections, there is an urgent need for the development of equine-specific vaccines that target this pathogen [

20]. Additionally, the study emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis and prompt treatment. The consistent use of PCR in this study underscores its utility as a diagnostic tool for clostridial infections. However, the reliance on advanced laboratory techniques also points to a gap in diagnostic capabilities in rural and remote areas, where access to such facilities may be limited [

21].

In the context of Brazil, and especially within the Amazon Biome, the significance of gas gangrene in equines is magnified by several factors. The Amazon is a vast, remote, and ecologically unique region where veterinary services are often limited, and the infrastructure for disease surveillance and management is underdeveloped. This geographical and infrastructural challenge contributes to the lack of data on the occurrence of gas gangrene in horses, which in turn hinders efforts to understand the true prevalence and impact of the disease. The scarcity of epidemiological data on clostridial infections in the Amazon further complicates the development of targeted prevention and control strategies, leaving equine populations vulnerable to outbreaks with potentially devastating consequences. The study underscores the urgent need for comprehensive epidemiological surveys and the establishment of robust reporting systems to address this gap in knowledge [

21,

22,

23]. Furthermore, horses in the Amazon are frequently exposed to environmental wounds, cuts, and abrasions due to their role in rural activities, which can become easily contaminated with soil and organic matter harboring

C. septicum spores. While

C. perfringens and

C. sordellii [

10,

12,

13,

15,

17,

24] is more commonly reported globally as the primary cause of gas gangrene in horses, our study suggests that in the Amazon,

C. septicum plays a predominant role due to these particular environmental factors, however they are necessary more studies to explain this greater occurrence of

C. speticum spores to the detriment of other species. This finding in this current study adds to the growing understanding of how geographical and ecological factors can influence pathogen prevalence and disease patterns, making the Amazon Biome a region of special interest for veterinary epidemiology.

Moreover, the lack of diagnosis and awareness among veterinarians and producers about gas gangrene poses a significant barrier to effective disease management in the Amazon Biome. Many veterinarians and equine breeders in the region may be unfamiliar with the clinical signs of gas gangrene, leading to misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis, which reduces the chances of successful treatment. The disease’s nonspecific early symptoms can be easily overlooked or mistaken for less severe conditions, further complicating timely intervention. This lack of knowledge not only affects animal health and welfare but also has significant economic implications [

25,

26,

27]. The financial impact of gas gangrene on equine breeding in the Amazon is substantial, as the loss of valuable animals to the disease can result in direct financial losses for breeders, as well as broader economic effects on the equine industry in the region.

The findings of this retrospective study highlight the critical need for enhanced veterinary education and training focused on the recognition and management of gas gangrene in equines [

28,29]. Additionally, there is an urgent need for the development and dissemination of practical diagnostic tools that can be used in the field by veterinarians and producers in remote areas of the Amazon. The study also calls for increased investment in research to develop effective vaccines [

2,

4,

22,

23] and treatment protocols tailored to the specific challenges of managing clostridial infections in equines within the Amazon Biome. By addressing these gaps in knowledge, diagnostics, and disease management, it is possible to reduce the incidence and impact of gas gangrene in equines, ultimately improving the health and productivity of equine populations in the Amazon and beyond.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has emerged as the most widely used diagnostic tool for clostridial myonecrosis [

9], primarily due to its high sensitivity, specificity, and rapid turnaround time. Unlike traditional culture methods [

26,

28], which can be time-consuming and often complicated by the fastidious nature of

Clostridium species, PCR allows for the direct detection of clostridial DNA from clinical samples, leading to faster diagnosis and treatment [

6]. One of the main advantages of PCR is its ability to detect specific gene sequences that are indicative of pathogenic strains by detecting the genes that encode the presence of clostridial toxin [

9]. The ability to identify specific

Clostridium species, such as

C. perfringens,

C. septicum, and others, allows for more targeted treatment strategies, which can be critical in managing the rapid progression of gas gangrene. PCR’s role in the diagnosis of clostridial myonecrosis is further solidified by its application in multiplex assays, which can simultaneously detect multiple pathogens or toxins from a single sample. This multiplexing capability is particularly beneficial in polymicrobial infections or when rapid differentiation between toxin-producing and non-toxin-producing strains is necessary [

6,

7,

9]. Furthermore, the adoption of PCR in veterinary medicine, particularly in regions like the Amazon Biome where clostridial diseases are prevalent, has enhanced the ability of veterinarians to manage outbreaks more effectively. PCR is not only faster but also more accurate than other diagnostic methods, reducing the likelihood of false positives or negatives. Microbiological examination, for example, typically involves the correct collection and immediate shipment of samples. The samples for microbiological analysis can be obtained from affected tissues, fluids from the site of infection, or aspirates from subcutaneous gas pockets [

6].

Clostridium species are cultured on specific anaerobic media. However, identification is only confirmed through PCR or MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, which differentiates between the various

Clostridium species. The identification of specific toxins, such as alpha, beta, and other toxins produced by

C. perfringens or the lethal toxins of

C. septicum, may be performed to confirm the diagnosis and understand the pathogenesis, but it is extremely difficult, as it requires inputs and professionals trained to perform in vivo serumneutralization [

2], which is currently discussed from the point of view of the use of laboratory animals for diagnosis.

Gas gangrene in horses, caused primarily by

C. septicum, presents with severe clinical pathology, microbiological, and histopathological changes. Understanding these findings is crucial for the accurate diagnosis, treatment, and management of this rapidly progressing and often fatal disease. The comprehensive examination of clinical samples, coupled with detailed anatomical and histopathological analysis, is essential for confirming the diagnosis and understanding the pathogenesis of gas gangrene in horses. Diagnostic improvements: further research should explore the development of rapid and more sensitive diagnostic tools, particularly molecular methods such as real-time PCR, which could allow for earlier and more accurate detection of

C. septicum and other clostridial species in equines. Additionally, serological assays could be improved to better identify subclinical or early-stage infections, which may help in preventing the progression of gas gangrene. Vaccine development: given the prevalence of

C. septicum in the cases studied and its pathogenicity in horses, the development of a vaccine targeted against this species should be a priority. Research could focus on recombinant vaccine development that targets key virulence factors of

C. septicum. Studies assessing the efficacy of multivalent clostridial vaccines in equines, particularly in regions with environmental conditions similar to the Amazon Biome, would be crucial to improving preventive measures. Gas gangrene, primarily caused by histotoxic

Clostridium species such as

C. septicum, is a severe and often fatal condition in horses [

2,

4,

20,

21]. Preventing gas gangrene is critical for maintaining the health and productivity of horses, especially in regions where these infections are prevalent. Various preventive measures can be employed: a). Prompt and thorough cleaning of wounds is essential to prevent the introduction and proliferation of

Clostridium spores, which thrive in anaerobic conditions; b). Applying antiseptics to wounds and administering prophylactic antibiotics can help reduce the risk of infection, especially in deep or puncture wounds; c). Maintaining clean and dry stables reduces the risk of environmental contamination with

Clostridium spores. Proper disposal of manure and organic waste is also crucial to minimize exposure; d). Ensuring that feed and bedding materials are free from contamination with

Clostridium spores can prevent infections originating from the environment; e). Where available, regular vaccination schedules should be adhered to, especially in regions prone to clostridial infections; f). Regular veterinary examinations can help detect early signs of infection, allowing for prompt treatment before the disease progresses.

While vaccines for clostridial diseases are available for other livestock, such as cattle and sheep, there is a notable gap in the availability of equine-specific vaccines for gas gangrene [

2,

4,

22,

23,

24]. The development of such vaccines is crucial for several reasons: 1). Species-specific immunogenicity: horses may respond differently to vaccines designed for other species, necessitating the development of vaccines tailored to their immune systems for optimal protection. 2). Disease prevalence: in regions where gas gangrene is common among equines, an equine-specific vaccine could significantly reduce the incidence and severity of the disease, thereby reducing mortality rates and improving animal welfare. 3). Economic impact: gas gangrene can cause significant economic losses in equine industries, particularly in areas where horses are used for labor, transportation, or competitive sports. Vaccines could mitigate these losses by preventing outbreaks and reducing the need for costly treatments.

The development of new vaccines and vaccine methodologies [

2,

4,

21,

22] is critical to advancing equine husbandry and preventing clostridial diseases like gas gangrene. Key areas of focus include: 1). Next-Generation Vaccines: a) Subunit vaccines: these vaccines use specific antigens, such as toxins or surface proteins, to elicit an immune response without using whole bacteria. They offer a safer alternative with fewer side effects; b).Toxoid vaccines: which use inactivated toxins, could be particularly effective against gas gangrene, as the disease’s pathology is largely driven by toxin production. 2). Adjuvants and delivery systems: a). Innovative adjuvants: the use of advanced adjuvants can enhance the immune response, allowing for lower doses of the antigen and potentially reducing the frequency of booster shots; b). Novel delivery systems: research into delivery systems such as nanoparticles or liposomes could improve the stability and efficacy of vaccines, making them more effective in challenging environmental conditions. 3). DNA and mRNA vaccines: these vaccines involve the introduction of plasmid DNA encoding the antigen into the host, prompting the production of the antigen and an immune response. DNA vaccines are stable, easy to produce, and offer the potential for rapid development. mRNA vaccines the success of mRNA vaccines in human medicine, particularly for COVID-19, suggests that similar technologies could be adapted for use in equines. These vaccines can be rapidly designed and produced, offering a flexible platform for responding to emerging clostridial strains. 4). Field-applicable vaccines thermostable formulations: developing vaccines that do not require refrigeration would be particularly beneficial in remote or resource-limited areas, where cold chain logistics are challenging. 5). Single-dose vaccines: single-dose formulations would simplify vaccination protocols, making them more practical for use by farmers and veterinarians in the field. Preventing gas gangrene in equines requires a multifaceted approach, combining proper wound care, environmental management, and vaccination. The development of equine-specific vaccines is a critical step in enhancing disease prevention strategies. Continued research and innovation in vaccine technologies are essential for creating more effective, accessible, and field-ready vaccines. These advancements will not only improve equine health and productivity but also contribute to the sustainability of equine industries world wide [

2,

4,

21,

23].

In conclusion, the findings from this study provide valuable epidemiological data on gas gangrene in horses in the Amazon Biome and highlight the need for region-specific interventions. The predominance of C. septicum in these cases suggests that this pathogen is a major threat to equine health in this region, necessitating targeted research, improved diagnostic tools, and the development of vaccines tailored to the unique challenges of the Amazon environment. The study also calls for increased awareness among veterinarians and horse owners about the risks of C. septicum and the importance of rapid response to prevent the high mortality associated with gas gangrene. In the Amazon Biome, the hot, humid, and tropical climate creates an ideal environment for the proliferation of Clostridium species, which are responsible for gas gangrene. These conditions favor the survival of the bacteria in the soil, water, and organic material, leading to a higher risk of infection in horses that may have wounds or injuries, particularly in humid pastures or wetlands. The constant exposure to these environmental factors increases the likelihood of contamination and may exacerbate the progression of the disease. The management of gas gangrene in this context requires careful attention to the early detection of wounds, proper wound care, and effective sanitation practices. The challenges of maintaining hygiene in the Amazon’s rural areas, where access to veterinary care may be limited, can delay treatment and result in more severe cases. Additionally, the rapid onset and progression of gas gangrene, often exacerbated by the local climate, underscore the importance of timely interventions such as aggressive surgical debridement and the administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Considering the endemicity of clostridial bacteria in this region, preventive measures, including vaccination programs and controlled grazing practices, become critical for reducing the incidence of gas gangrene in horses. Overall, the environmental conditions of the Amazon Biome significantly impact the development, progression, and management of gas gangrene, necessitating tailored approaches to veterinary care in this unique setting.