Submitted:

28 August 2024

Posted:

29 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

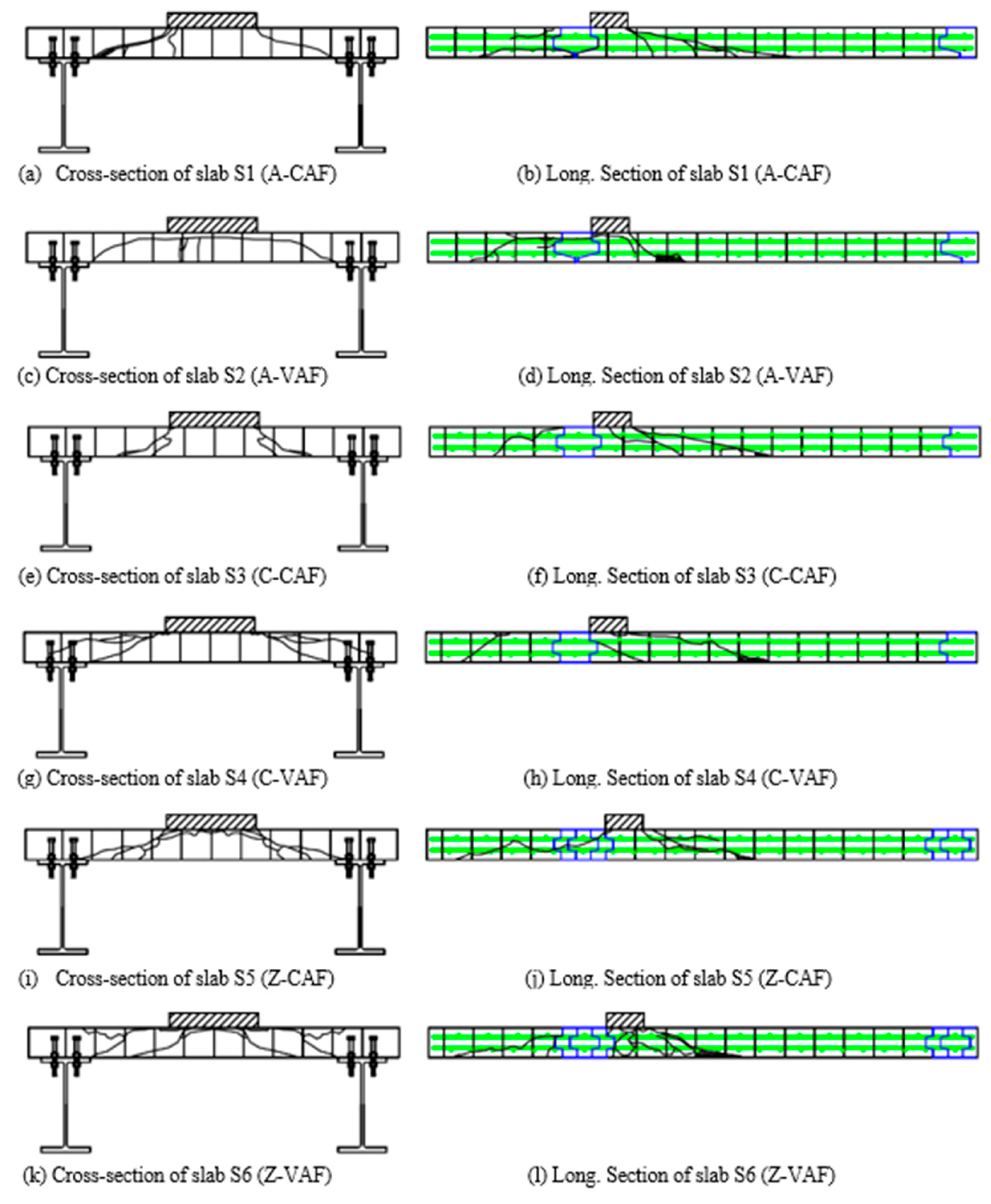

2. New Connection Details

3. Experimental Program

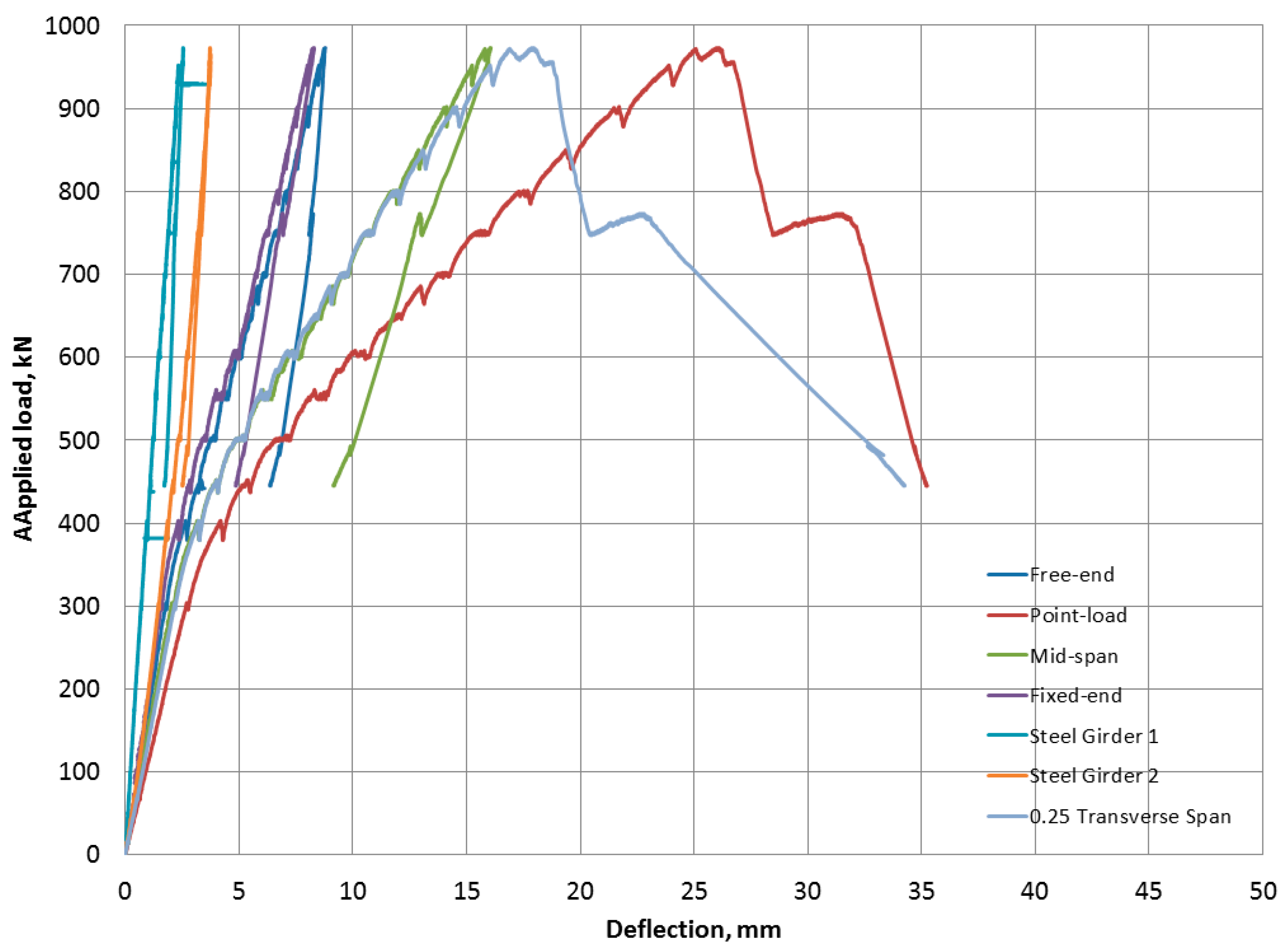

4. Experimental Test Results

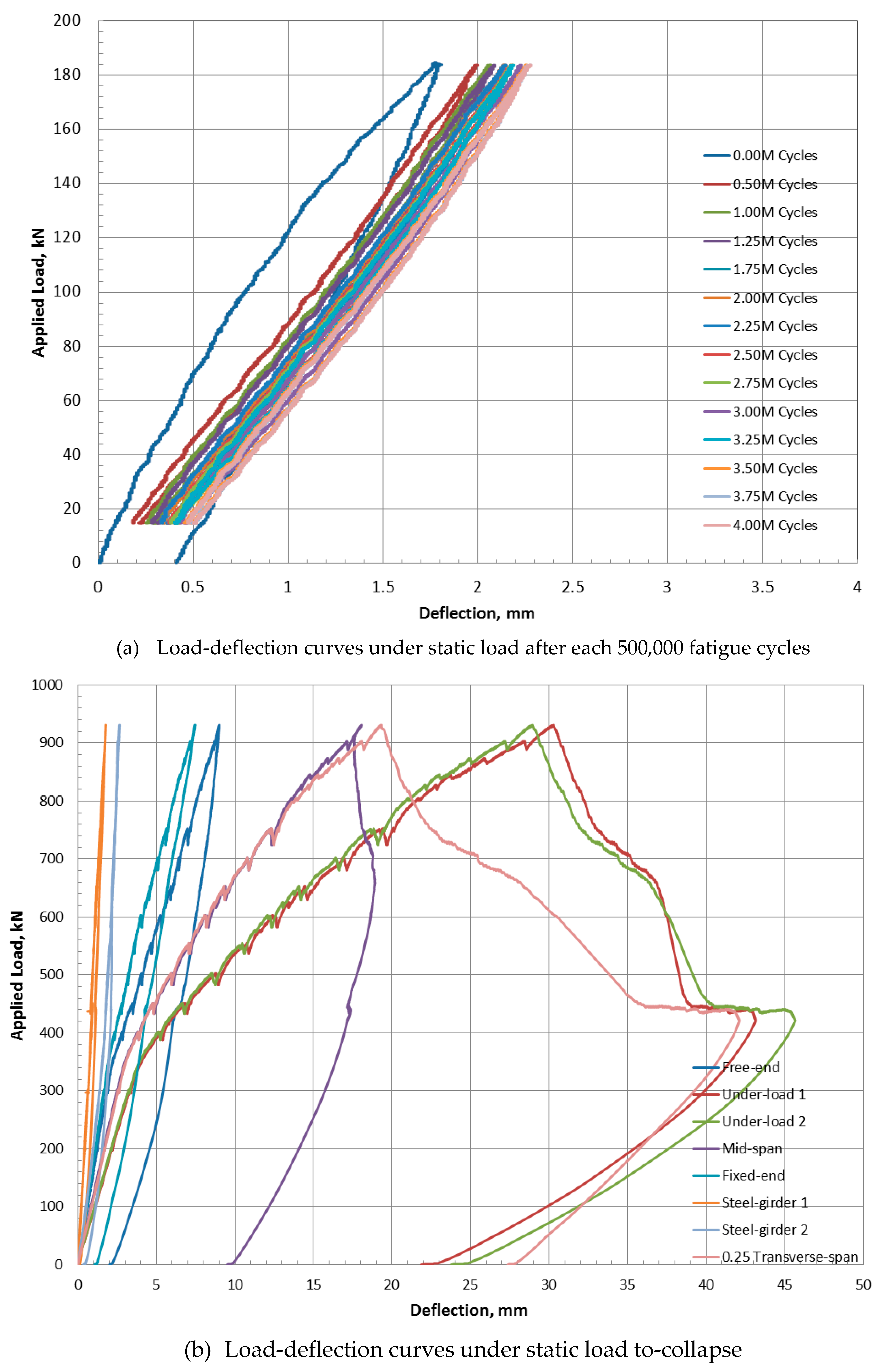

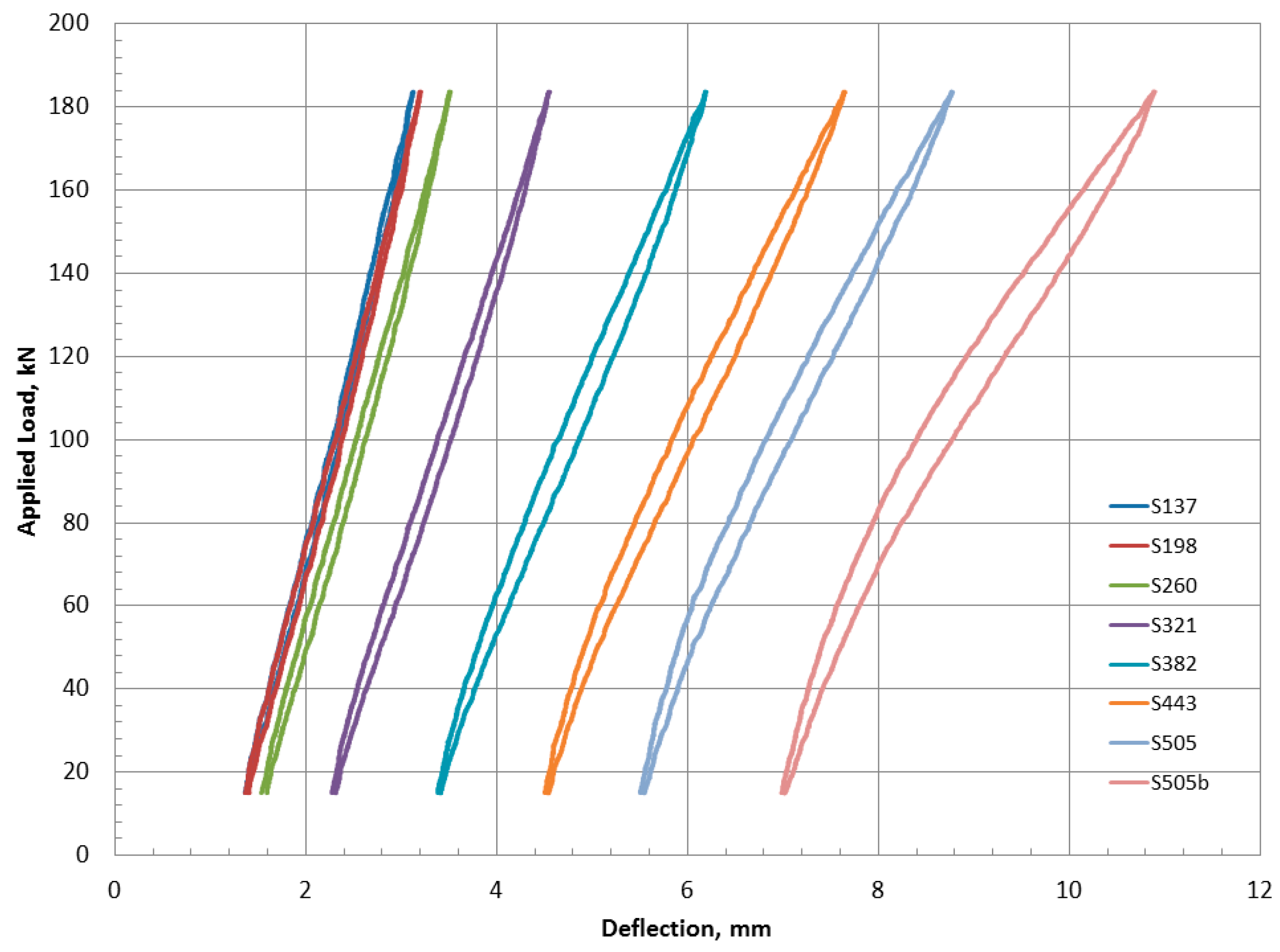

4.1. Constant Amplitude Fatigue Loading

4.1.1. Behavior of the A-Jointed Precast FDDP under CAF

4.1.2. Behavior of the C-Jointed Precast FDDP under CAF

4.1.3. Behavior of the Z-Jointed Precast FDDP under CAF

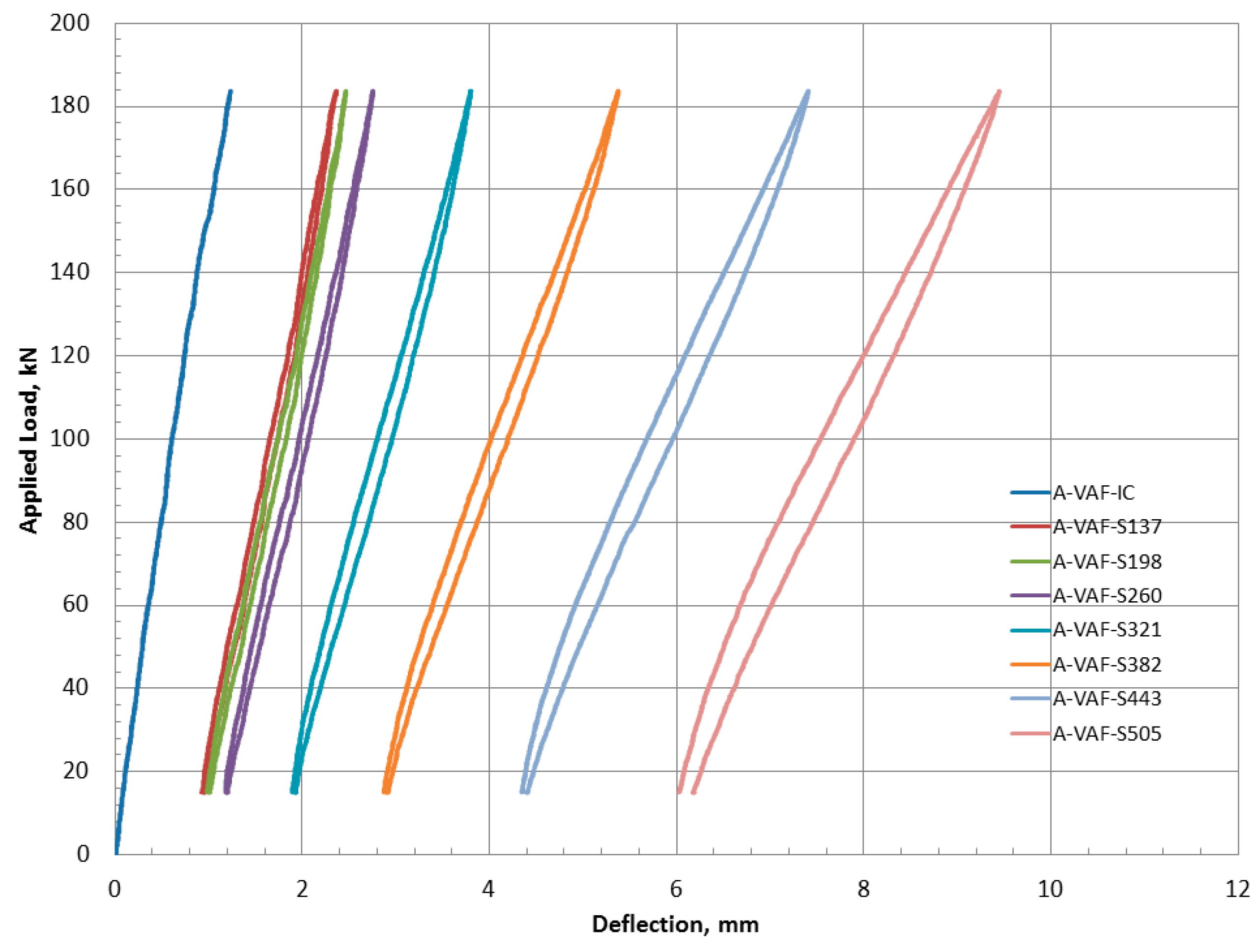

4.2. Variable Amplitude Fatigue Loading

4.2.1. Behavior of the A-Jointed Precast FDDP under VAF

4.2.2. Behavior of the C-Jointed Precast FDDP under VAF

4.2.3. Behavior of the Z-Jointed Precast FDDP under VAF

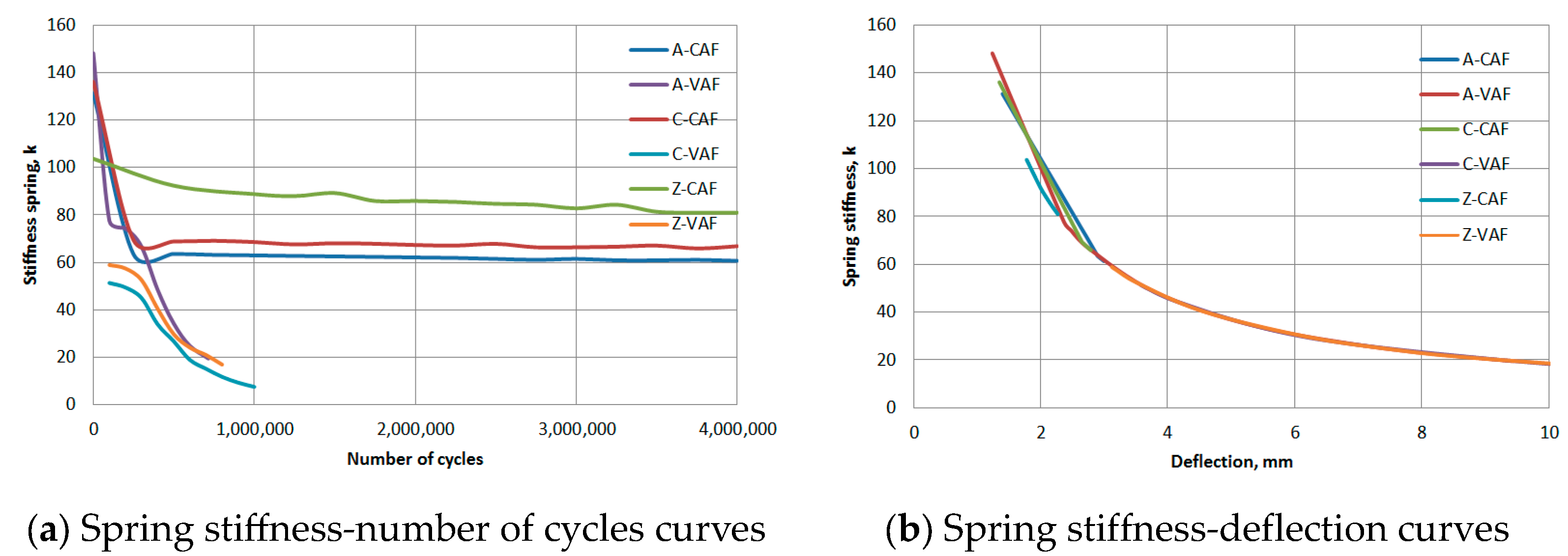

4.3. Stiffness Degradation

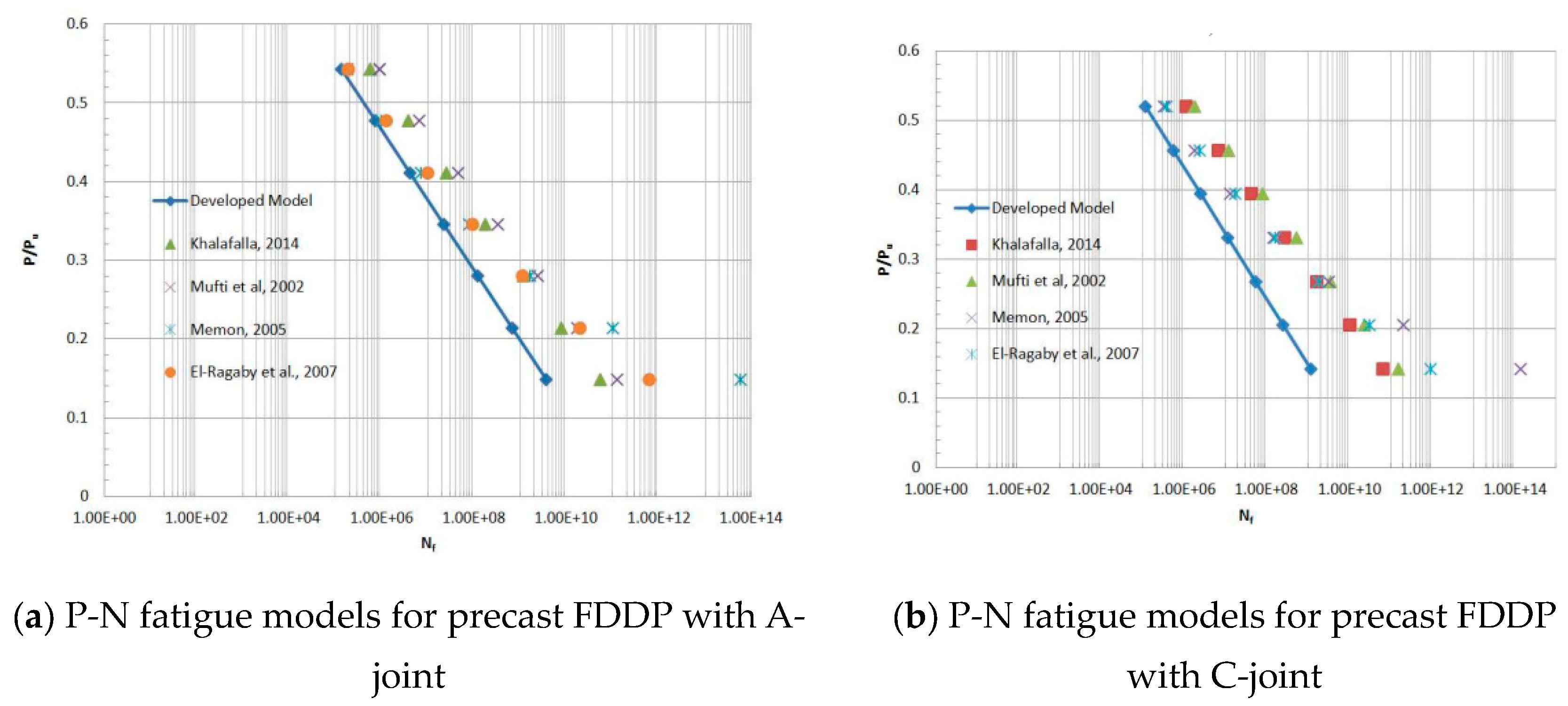

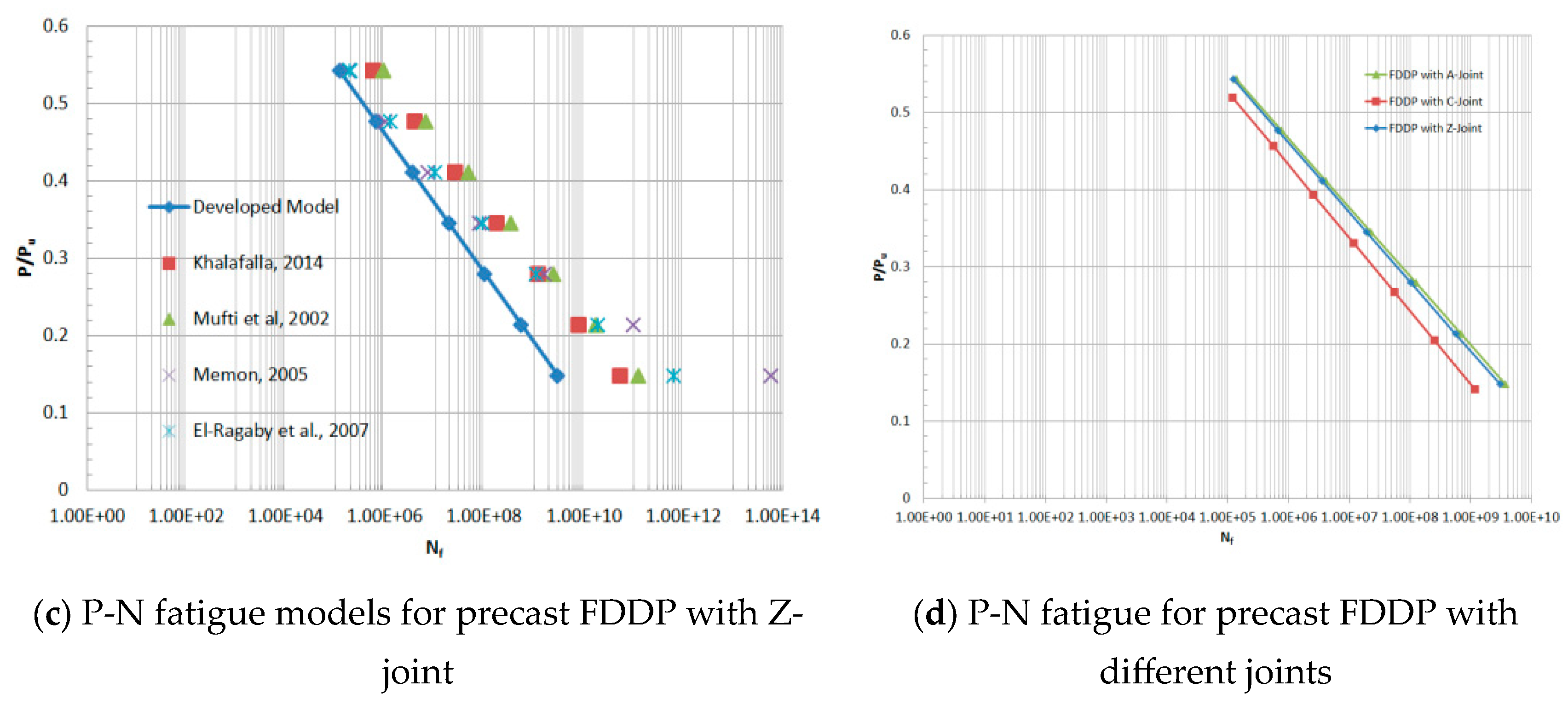

4.4. Life Estimation of Fatigue of GFRP-Reinforced Precast FDDP

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clumo, M. , 2011. Accelerated Bridge Construction - Experience in Design, Fabrication and Erection of Prefabricated Bridge Elements and Systems, FHWA-HIF-12-013, Federal Highway Administration, McLean, VA.

- CSA. 2014. Canadian Highway Bridge Design Code, CAN/CSA-S6-14. Canadian Standards Association, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada.

- Badie, S.; Tadros, M. 2008. Full-Depth Precast Concrete Bridge Deck Panel Systems. NCHRP Report 584, Transportation Research Board, Washington, D.C.

- Afefy, H.M.; Sennah, K.; Tu, S.; Ismail, M.; Kianoush, R. 2015. Experimental Study on the Ultimate Capacity of Deck Joints in Prefabricated Concrete Bulb-Tee Bridge Girders. Journal of Bridge Structures, Design, Assessment and Construction, 11 (2015) 55–71.

- Sennah, K.; Afefy, H.M. , (2015) “Development and study of deck joints in prefabricated concrete bulb-tee bridge girders: Conceptual design” Bridge Structures, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2, pp. 33–53. [CrossRef]

- Shah, B.; Sennah, K.; Kianoush, R.; Tu, S.; Clifford, L. 2007. Experimental Study on Prefabricated Concrete Bridge Girder-to-Girder Intermittent-Bolted Connection Systems. ASCE Journal of Bridge Engineering, 12(5): 570-584. [CrossRef]

- Sennah, S.K.; Kianoush, R.; Tu, S.; Lam, C. 2006. Flange-to-Flange Moment Connections for Precast Concrete Deck Bulb-Tee Bridge Girders. Journal of Prestressed Concrete Institute, PCI, 51(6): 86-107.

- PCI. 2011a. State-of-the-Art Report on Full-Depth Precast Concrete Bridge Deck Panels (SOA-01-1911), PCI Committee on Bridges and the PCI Bridge Producers Committee, Precast/Prestressed Concrete Institute, USA.

- PCI 2011b. Full Depth Deck Panels Guidelines for Accelerated Bridge Deck Replacement or Construction. Report Number PCINER-11-FDDP, Precast/Prestressed Concrete Institute, USA.

- Badie, S.; Tadros, M.; Girgis, A. , 2006. Full-Depth, Precast-Concrete Bridge Deck Panel Systems. Report No. NCHRP 12-65, Transportation Research Board, Washington, D.C.

- Hwang, H.; Park, S. 2014. A Study on the Flexural Behavior of Lap-spliced Cast-in-place Joints under Static Loading in Ultra-high Performance Concrete Bridge Deck Slabs. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering, 41: 615-623. [CrossRef]

- Russell, H.; Graybeal, B. 2013. Ultra-High Performance Concrete: A State-of-the-Art Report for the Bridge Community, Publication No. FHWA-HRT-13-060, Federal Highway Administration, McLean, VA.

- Abokifa, M. (2021). Application of Polymer Concrete and Non-Proprietary Ultra-High Performance Concrete for Pre-fabricated Bridge Decks Field Joints (Doctoral dissertation, University of Nevada, Reno).

- Afefy, H.M.; Kassem, N.; Taher, S. (2021) Strengthening of defected closure strips for full-depth RC deck slabs using CFRP sheets” Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Structures and Buildings. Volume 174 Issue 7, July, 2021, pp. 581-594. [CrossRef]

- Abdal, S.; Mansour, W.; Agwa, I.; Nasr, M.; Abadel, A.; Onuralp Özkılıç, Y. Akeed, M.H. (2023). Application of ultra-high-performance concrete in bridge engineering: current status, limitations, challenges, and future prospects. Buildings, 13(1), 185. [CrossRef]

- ACI Committee 440. 2006. Guide for the Design and Construction of Structural Concrete Reinforced with FRP Bars, ACI 440.1R-06. American Concrete Institute, Farmington Hills, MI, USA.

- Wu, W.; He, X.; Yang, W.; Dai, L.; Wang, Y.; He, J. (2022). Long-time durability of GFRP bars in the alkaline concrete environment for eight years. Construction and Building Materials, 314, 125573. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Li, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Qu, W. (2023). Prediction of the Long-Term Tensile Strength of GFRP Bars in Concrete. Buildings, 13(4), 1035. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Afefy, H.M.; Azimi, H.; Sennah, K.; Sayed-Ahmed, M. , (2021) “Bond performance of sand-coated and ribbed-surface glass fiber reinforced polymer bars in high-performance concrete” Structures, December, Vol. 34, pp. 10-19.

- Rostami, M.; Sennah, K.; Afefy, H.M. (2018) “Ultimate capacity of barrier-deck anchorage in MTQ TL-5 barrier reinforced with headed-end, high-modulus, sand-coated GFRP bars” Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering, Vol. 45, April, 263-275.

- Islam, S.; Afefy, H.M.; Sennah, K.; Azimi, H. , (2015) “Bond characteristics of straight- and headed-end ribbed-surface GFRP bars embedded in high-strength concrete” Construction & Building Materials, Vol. 83, May, pp. 283–298.

- AASHTO, 2012. AASHTO-LRFD Bridge Design Specifications, Fifth Edition. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, Washington, D.C.

- Perdikaris, P.; Beim, S. 1988. RC Bridge Decks under Pulsating and Moving Load. Journal of Structural Engineering, 114(3): 591-607. [CrossRef]

- Edalatmanesh, R.; Newhook, J. 2013a. Residual Strength of Precast Steel-Free Panels. ACI Structural Journal, 110(5): 715-721. [CrossRef]

- Edalatmanesh, R.; Newhook, J. 2013b. Investigation of Fatigue Damage in Steel-Free Bridge Decks with Application to Structural Monitoring. ACI Structural Journal, 110(4): 557-564. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.; Yoon, H.; Joh, C.; Kim, B. 2010. Punching and Fatigue Behavior of Long-Span Prestressed Concrete Deck Slabs. Engineering Structures, 32: 2861-2872. [CrossRef]

- Klowak, C.; Memon, A.; Mufti, A. 2007. Static and Fatigue Investigation of Innovative Second Generation Steel-Free Bridge Decks. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering, 34: 331-339. [CrossRef]

- Sonoda, K.; Horikawa, T. 1982. Fatigue Strength of Reinforced Concrete Slabs under Moving Load. Zurich, Switzerland, pp. 455-462.

- Hassan, T.; Rizkalla, S.; Abdelrahman, A.; Tadros, G. 2000a. Fibre Reinforced Polymer Reinforcing Bars for Bridge Decks. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering, 27: 839-849.

- Hassan, T.; Rizkalla, S.; Adelrahman, A.; Tadros, G. 2000b. Design Recommendations for Bridge Deck Slabs Reinforced by Fibre Reinforced Polymers. ACI SP, pp. 188-29.

- Hassan, M.; Ahmed, E.; Benmokrane, B. 2013. Punching Shear Strength of Normal and High-Strength Two-Way Concrete Slabs Reinforced with GFRP Bars. ASCE Journal of Composites for Construction, 04013003: 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Dulude, C.; Hassan, M.; Ahmed, E.; Benmokrance, B. 2013. Punching Shear Behavior of Flat Slabs Reinforced with Glass Fibre Reinforced Polymer Bars. ACI Structural Journal, 110(5): 723-733.

- El-Ghandour, A.; Pilakoutas, K.; Waldron, P. 1999. New Approach for Punching Shear Capacity Prediction of Fiber Reinforced Polymer Reinforced Concrete Flat Slabs. ACI Structural Journal, 188(13):135-144. [CrossRef]

- El-Ghandour, A.; Pilakoutas, K.; Waldron, P. 2003. Punching Shear Behaviour of Fiber Reinforced Polymers Reinforced Concrete Flat Slabs: Experimental Study. ASCE Journal of Composite for Construction, 7(3): 258-265. [CrossRef]

- Braimah, A.; Green, M.; Soudki, K. , 1998. Polypropylene FRC Bridge Deck Slabs Transversely Prestressed with CFRP Tendons. ASCE Journal of Composite for Construction, 2(4): 149-157. [CrossRef]

- Benmokrane, B.; El-Salakawy, E.; El-Ragaby, A.; Lackey, T. 2006. Designing and Testing of Concrete Bridge Decks Reinforced with Glass FRP Bars. ASCE Journal of Bridge Engineering, 11(2): 217-229. [CrossRef]

- El-Salakawy, E.; Benmokrane, B.; El-Ragaby, A.; Nadeau, D. 2005. Field Investigation on the First Bridge Deck Slab Reinforced with Glass FRP Bars Constructed in Canada. Journal of Composites for Construction, 9(6): 470-479. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, D.; Bank, L.; Oliva, M.; Russell, J. 2005. Punching Shear Capacity of Double Layer FRP Grid Reinforced Slabs. Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Fiber Reinforced Plastics for Reinforced Concrete Structures, American Concrete Institute, New Orleans, La., pp. 857–871.

- El-Gamal, S.; El-Salakawy, E.; Benmokrane, B. 2005. Behavior of Concrete Bridge Deck Slabs Reinforced with Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Bars under Concentrated Loads. ACI Structural Journal, 102(5): 727-735. [CrossRef]

- Khanna, O.; Mufti, A.; Bakht, B. 2000. Experimental Investigation of the Role of Reinforcement in the Strength of Concrete Deck Slabs. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering, 27: 475-480.

- Matthys, S.; Taerwe, L. 2000. Concrete Slabs Reinforced with FRP Grid. II: Punching Resistance. ASCE Journal of Composite for Constructions, 4(3): 154-161.

- Banthia, N.; Al-Asaly, M.; Ma, S. 1995. Behavior of Concrete Slabs Reinforced with Fiber-Reinforced Plastic Grid. ASCE Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 7(4): 643-652. [CrossRef]

- Mufti, A.; Jaeger, L.; Bakht, B.; Wegner, L. 1993. Experimental Investigation of FRC Slabs without Internal Steel Reinforcement. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering, 20(3): 389-406.

- Ahmad, S.H.; Zia, P.; Yu, T.; Xie, Y. 1993. Punching Shear Tests of Slabs Reinforced with 3-D Carbon Fiber Fabric. Concrete International, 16: 36-41.

- You, Y.; Kim, J.; Park, Y.; Choi, J. 2015. Fatigue Performance of Bridge Deck Reinforced with Cost-to-Performance Optimized GFRP Rebar with 900 MPa Guaranteed Tensile Strength. Journal of Advanced Concrete Technology, 13: 252-262. [CrossRef]

- Khalafalla, I.; Sennah, K. 2021. Ultimate and Fatigue Responses of GFRP-Reinforced, UHPC-Filled, Bridge Deck Joints. ACI Special Publication SP-356: Development & Applications of FRP Reinforcements, pp. 347-374. [CrossRef]

- El-Ragaby, A.; El-Salakawy, E.; Benmokrane, B. , 2007. Fatigue Life Evaluation of Concrete Bridge Deck Slabs Reinforced with Glass FRP Composite Bars. Journal of Composite for Construction, 11(3): 258-268. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; GangaRao, H. 1992. Fatigue Response of Concrete Decks Reinforced with FRB Rebars. ACI Structural Journal, 89(1): 13-19.

- Rahman, A.; Kingsley, C.; Kobayashi, K. 2000. Service and Ultimate Load Behaviour of Bridge Deck Reinforced with Carbon FRP Grid. ASCE Journal of Composite of Construction, 4(1): 16-23.

- Zhu, P.; Ma, Z.; Cao, Q.; French, C. 2012. Fatigue Evaluation of Longitudinal U-Bar Joint Details for Accelerated Bridge Construction. Journal of Bridge Engineering, 17: 201-210. [CrossRef]

- Graybeal, B. 2010. Behavior of Field-Cast Ultra-High Performance Concrete Bridge Deck Connections under Cyclic and Static Structural Loading. Report No. FHWA-HRT-11-023, Federal Highway Administration, 116 pages.

- Hwang, H.; Park, S. 2014. A Study on the Flexural Behavior of Lap-spliced Cast-in-place Joints under Static Loading in Ultra-high Performance Concrete Bridge Deck Slabs. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering, 41: 615-623. [CrossRef]

- Gar, S.; Head, M.; Hurlebaus, S.; Mander, J. 2014. Experimental Performance of AFRP Concrete Bridge Deck Slab with Full-Depth Precast Prestressed Panels. Journal of Bridge Engineering, 04013018: 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Karunananda, K.; Ohga, K.; Dissanayake, R.; Siriwardane, S. 2010. A Combined High and Low Cycle Fatigue Model to Estimate Life of Steel Bridges. Journal of Engineering and Technology Research, 2(8): 144-160.

- Adimi, M.; Rahman, A.; Benmokrane, B. 2000. New Method for Testing Fibre-Reinforced Polymers Rods under Fatigue. Journal of Composites for Construction, 4(4): 206-213.

- Katz, A. 2000. Bond to Concrete of FRP Rebars After Cyclic Loading. Journal of Composites for Construction, 4(3): 137-144. [CrossRef]

- Sayed-Ahmed MS. 2016. Development and Study of Closure Strip Between Precast Deck Panels in Accelerated Bridge Construction. PhD thesis, Ryerson University, Toronto, ON, Canada.

- Schoeck Canada Inc. ComBar Product Manual. [Online] Available at: www.schoeckcanada.com.

- Palmgren, A. Die Lebensdauer von Kugellagern. Verfahrenstechinik. Berlin, Vol. 68, pp 338-341, 1924.

- Miner, M.A. , “Cumulative Damage in Fatigue,” Journal of Applied Mechanics, Vol. 67, pp. A159-164, 1945.

- Memon, A.H. 2005. Compressive Fatigue Performance of Steel Reinforced and Steel-Free Bridge Deck Slabs. PhD Thesis, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada. 125p.

- Mufti, 4.4., Memon, 4.H., Bakht, 8., and Banthia, N. (2002). Fatigue Investigation of the Steel-Free Bridge Deck Slabs. ACI International SP 206-4, American Concrete Institute, pp.6I-70.

| Product type | Bar size | Bar area (mm2) |

Guaranteed tensile strength (MPa) | Modulus of elasticity (GPa) | Strain at failure |

| Ribbed-surface | 15M (#5) | 201 | 1188 | 64 | 2.6% |

| Slab Name | Transverse reinforcement (normal to girder) |

Longitudinal reinforcement (parallel to girder) |

||||

| Slab number | Joint type | Test type* | Bottom | Top | Bottom | Top |

| S1 | A | CAF | Straight end No. 16 @ 140 mm |

Straight end No. 16 @ 200 mm |

Straight end No. 16 @ 200 mm |

Straight end No. 16 @ 200 mm |

| S2 | VAF | |||||

| S3 | C | CAF | Straight end No. 16 @ 140 mm |

Straight end No. 16 @ 200 mm |

Straight end No. 16 @ 200 mm |

Straight end No. 16 @ 200 mm |

| S4 | VAF | |||||

| S5 | Z | CAF | Straight end No. 16 @ 140 mm |

Straight end No. 16 @ 200 mm |

Straight end No. 16 @ 200 mm |

Straight end No. 16 @ 200 mm |

| S6 | VAF | |||||

| Loading | Unloading |

| Segment shape: ramp function Rate: 5 kN/min Control mode: Force Absolute end level (machine max. load for test purpose): 183.75 kN |

Segment shape: ramp function Rate: 10 kN/min Control mode: force Absolute end level: zero kN |

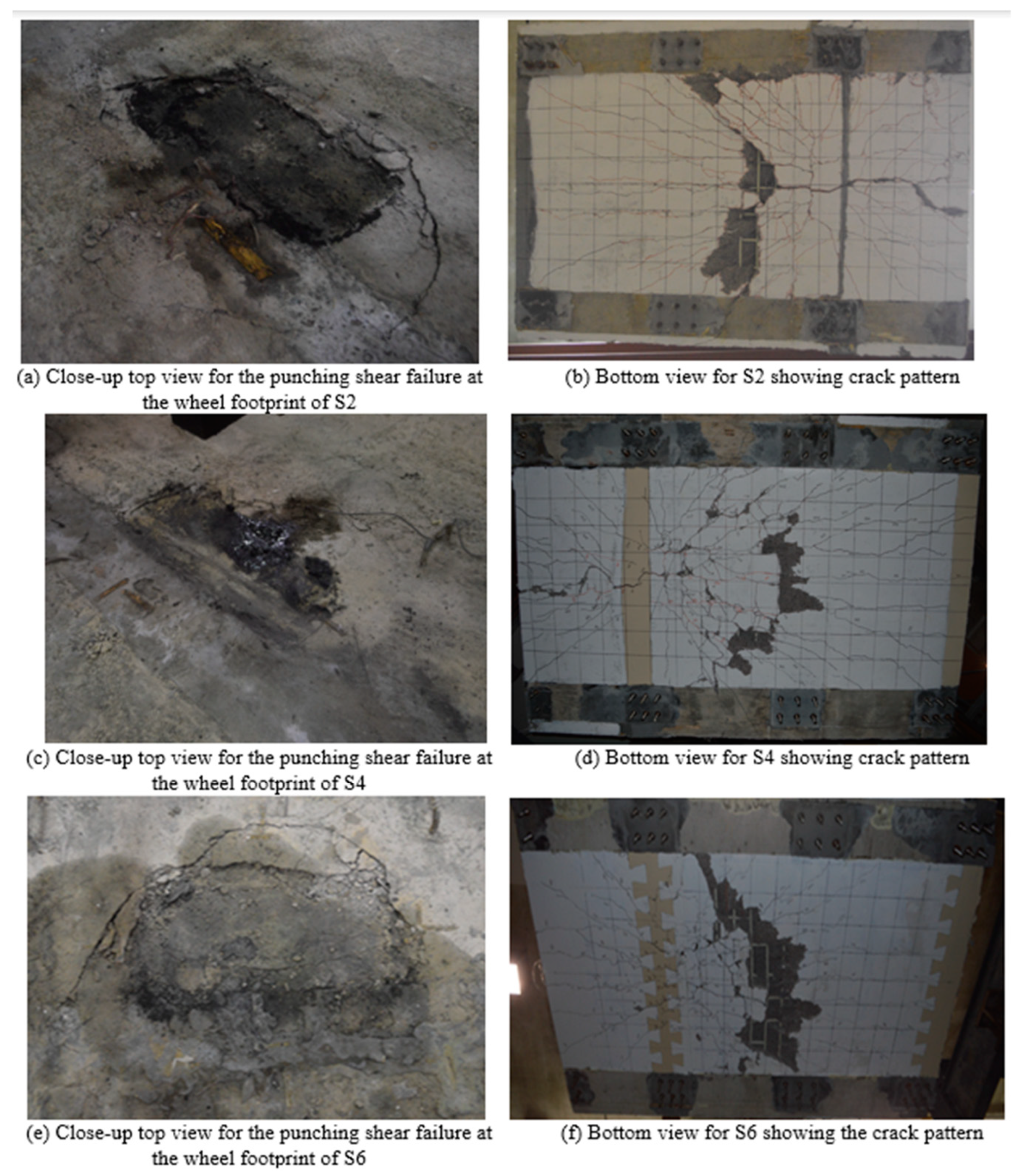

| Slab number | Joint type | Test* | Peak cyclic load (kN) | Frequency (Hz) | No. of load cycles | Ultimate load (kN) |

Ultimate deflection (mm) | Failure Mode |

| S1 | A | CAF + SUL | 137.5 | 4 | 4,000,000 | 930.92 | 23.47 | Punching |

| A | VAF | 500.0 | 2 – 0.5 | 809,493 | 487.50 | 32.46 | Punching | |

| S2 | C | CAF + SUL | 137.5 | 4 | 4,000,000 | 973.00 | 26.09 | Punching |

| C | VAF | 500.0 | 2 – 0.5 | 692,866 | 495.69 | 40.89 | Punching | |

| S3 | Z | CAF + SUL | 137.5 | 4 | 4,000,000 | 931.00 | 29.62 | Punching |

| Z | VAF | 500.0 | 2 – 0.5 | 961,540 | 488.43 | 37.03 | Punching |

| Monitoring direction | Deflection, mm | Comments | |||

| Longitudinal direction | A-Shape | C-Shape | Z-Shape | ||

| Free-end | 7.48 | 8.78 | 9.00 | Small segment | |

| Point-load 1 | 23.05 | 25.98 | 30.29 | Actual segment | |

| Point-load 2 | 23.88 | 26.20 | 28.94 | Actual segment | |

| Mid-span | 13.39 | 16.03 | 18.06 | Actual segment | |

| Fixed-end | 2.44 | 8.28 | 7.47 | Rear joint | |

| Transverse direction | |||||

| Steel-girder 1 | 10.68 | 2.54 | 1.78 | Twin girder | |

| 0.25 Transverse-span | 13.09 | 17.86 | 19.32 | Actual segment | |

| Point-load 1 | 23.05 | 25.98 | 30.29 | Actual segment | |

| Point-load 2 | 23.88 | 26.20 | 28.94 | Actual segment | |

| Steel-girder 2 | 6.8 | 3.73 | 2.65 | Twin girder | |

| Joint Type | Slab S1 with CAF loading* | Slab S2 with VAF loading* | ||||||

| Cumulative cycles (N) | Load (kN) |

Deflection (mm) | k = F/d** | Cumulative cycles, N | Load (kN) |

Deflection (mm) | k = F/d** | |

| A-type | 0 | 183.75 | 1.40 | 131.25 | 0 | 183.75 | 1.24 | 148.19 |

| 250,000 | 183.75 | 2.90 | 63.36 | 100,000 | 183.75 | 2.37 | 77.53 | |

| 500,000 | 183.76 | 2.89 | 63.58 | 200,000 | 183.76 | 2.47 | 74.39 | |

| 750,000 | 183.75 | 2.91 | 63.14 | 300,000 | 183.76 | 2.76 | 66.58 | |

| 1,000,000 | 183.75 | 2.92 | 62.92 | 400,000 | 183.76 | 3.80 | 48.35 | |

| 1,250,000 | 183.76 | 2.93 | 62.71 | 500,000 | 183.76 | 5.38 | 34.15 | |

| 1,500,000 | 183.76 | 2.94 | 62.50 | 600,000 | 183.78 | 7.41 | 24.80 | |

| 1,750,000 | 183.76 | 2.95 | 62.29 | 715,381 | 183.76 | 9.44 | 19.46 | |

| 2,000,000 | 183.77 | 2.96 | 62.08 | 809,493 | ||||

| 2,250,000 | 183.76 | 2.97 | 61.87 | |||||

| 2,500,000 | 183.75 | 2.99 | 61.45 | |||||

| 2,750,000 | 183.76 | 3.01 | 61.05 | |||||

| 3,000,000 | 183.75 | 2.99 | 61.45 | |||||

| 3,250,000 | 183.76 | 3.02 | 60.84 | |||||

| 3,500,000 | 183.76 | 3.02 | 60.84 | |||||

| 3,750,000 | 183.75 | 3.01 | 61.04 | |||||

| 4,000,000 | 183.76 | 3.03 | 60.64 | |||||

| C-type | Slab S3 with CAF loading* | Slab S4 with VAF loading* | ||||||

| 0 | 183.75 | 1.35 | 136.11 | 100,000 | 183.75 | 3.58 | 51.32 | |

| 500,000 | 183.76 | 2.65 | 69.34 | 200,000 | 183.76 | 3.72 | 49.39 | |

| 1,000,000 | 183.76 | 2.67 | 68.82 | 300,000 | 183.75 | 4.09 | 44.92 | |

| 1,250,000 | 183.76 | 2.66 | 69.08 | 400,000 | 183.75 | 5.43 | 33.84 | |

| 1,500,000 | 183.76 | 2.68 | 68.56 | 500,000 | 183.76 | 6.89 | 26.67 | |

| 1,750,000 | 183.76 | 2.72 | 67.56 | 600,000 | 183.75 | 9.74 | 18.86 | |

| 2,000,000 | 183.76 | 2.7 | 68.05 | 692,866 | ||||

| 2,250,000 | 183.76 | 2.71 | 67.80 | |||||

| 2,500,000 | 183.75 | 2.73 | 67.31 | |||||

| 2,750,000 | 183.76 | 2.74 | 67.06 | |||||

| 3,000,000 | 183.75 | 2.71 | 67.80 | |||||

| 3,250,000 | 183.75 | 2.77 | 66.33 | |||||

| 3,500,000 | 183.76 | 2.77 | 66.34 | |||||

| 3,750,000 | 183.76 | 2.76 | 66.58 | |||||

| 4,000,000 | 183.76 | 2.74 | 67.06 | |||||

| Z-shape | Slab S5 with CAF loading* | Slab S6 with VAF loading* | ||||||

| 0 | 184.55 | 1.78 | 103.68 | 100,000 | 183.74 | 3.12 | 58.89 | |

| 500,000 | 183.76 | 1.99 | 92.34 | 200,000 | 183.76 | 3.2 | 57.42 | |

| 1,000,000 | 183.75 | 2.07 | 88.77 | 300,000 | 183.76 | 3.5 | 52.5 | |

| 1,250,000 | 183.75 | 2.09 | 87.92 | 400,000 | 183.75 | 4.55 | 40.38 | |

| 1,500,000 | 183.76 | 2.06 | 89.2 | 500,000 | 183.76 | 6.19 | 29.68 | |

| 1,750,000 | 183.75 | 2.14 | 85.86 | 600,000 | 183.75 | 7.64 | 24.05 | |

| 2,000,000 | 183.77 | 2.14 | 85.87 | 700,000 | 183.75 | 8.77 | 20.95 | |

| 2,250,000 | 183.75 | 2.15 | 85.46 | 800,000 | 183.83 | 10.88 | 16.89 | |

| 2,500,000 | 183.75 | 2.17 | 84.68 | 895,000 | -- | |||

| 2,750,000 | 183.75 | 2.18 | 84.29 | 916,736 | -- | |||

| 3,000,000 | 183.75 | 2.71 | 67.80 | |||||

| 3,250,000 | 183.75 | 2.77 | 66.33 | |||||

| 3,500,000 | 183.76 | 2.77 | 66.34 | |||||

| 3,750,000 | 183.76 | 2.76 | 66.58 | |||||

| 4,000,000 | 183.76 | 2.74 | 67.06 | |||||

| Joint Pattern | H | k |

| A-Jointed Precast FDDP | 25.86 | 0.039 |

| C-Jointed Precast FDDP | 24.32 | 0.041 |

| Z-Jointed Precast FDDP | 25.61 | 0.039 |

| Segment | Pu | FLS | Pmin | Pmax | Pamp | Pmean | R | A | Pmax /Pu | n | Nf | n/Nf | ||

| MF | WL | FLS1 | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 930.92 | 1.0 | 87.5 | 122.5 | 15 | 137.50 | 61.25 | 76.25 | 0.109 | 0.803 | 0.148 | 100,000 | 3,740,491,266 | 2.673E-05 |

| 2 | 930.92 | 1.5 | 87.5 | 183.8 | 15 | 198.75 | 91.88 | 106.88 | 0.075 | 0.860 | 0.213 | 100,000 | 682,217,686 | 0.0001466 |

| 3 | 930.92 | 2.0 | 87.5 | 245.0 | 15 | 260.00 | 122.50 | 137.50 | 0.057 | 0.891 | 0.279 | 100,000 | 124,427,766 | 0.0008037 |

| 4 | 930.92 | 2.5 | 87.5 | 306.3 | 15 | 321.25 | 153.13 | 168.13 | 0.046 | 0.911 | 0.345 | 100,000 | 22,694,030 | 0.0044064 |

| 5 | 930.92 | 3.0 | 87.5 | 367.5 | 15 | 382.50 | 183.75 | 198.75 | 0.039 | 0.925 | 0.411 | 100,000 | 4,139,100 | 0.0241598 |

| 6 | 930.92 | 3.5 | 87.5 | 428.8 | 15 | 443.75 | 214.38 | 229.38 | 0.034 | 0.935 | 0.477 | 100,000 | 754,919 | 0.1324646 |

| 7 | 930.92 | 4.0 | 87.5 | 490.0 | 15 | 505.00 | 245.00 | 260.00 | 0.030 | 0.942 | 0.542 | 115,381 | 137,688 | 0.8379916 |

| 8 | 930.92 | 4.0 | 87.5 | 490.0 | 15 | 505.00 | 245.00 | 260.00 | 0.030 | 0.942 | 0.542 | 94,112 | 137,688 | 0.6835187 |

| Total | 809,493 | Σn/N | 0.9999995 | |||||||||||

| Segment | Pu | FLS | Pmin |

Pmax |

Pamp |

Pmean |

R |

A |

Pmax /Pu |

n |

Nf |

n/Nf |

||

| MF | WL | FLS1 | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 973 | 1.0 | 87.5 | 122.5 | 15 | 137.50 | 61.25 | 76.25 | 0.109 | 0.803 | 0.141 | 100,000 | 1,176,908,558 | 8.497E-05 |

| 2 | 973 | 1.5 | 87.5 | 183.8 | 15 | 198.75 | 91.88 | 106.88 | 0.075 | 0.860 | 0.204 | 100,000 | 254,549,386 | 0.0003929 |

| 3 | 973 | 2.0 | 87.5 | 245.0 | 15 | 260.00 | 122.50 | 137.50 | 0.058 | 0.891 | 0.267 | 100,000 | 55,055,586 | 0.0018163 |

| 4 | 973 | 2.5 | 87.5 | 306.3 | 15 | 321.25 | 153.13 | 168.13 | 0.047 | 0.911 | 0.330 | 100,000 | 11,907,778 | 0.0083979 |

| 5 | 973 | 3.0 | 87.5 | 367.5 | 15 | 382.50 | 183.75 | 198.75 | 0.039 | 0.925 | 0.393 | 100,000 | 2,575,491 | 0.0388275 |

| 6 | 973 | 3.5 | 87.5 | 428.8 | 15 | 443.75 | 214.38 | 229.38 | 0.034 | 0.935 | 0.456 | 100,000 | 557,044 | 0.1795191 |

| 7 | 973 | 4.0 | 87.5 | 490.0 | 15 | 505.00 | 245.00 | 260.00 | 0.030 | 0.942 | 0.519 | 92,886 | 120,481 | 0.7709595 |

| Total | 692,886 | Σn/N | 0.9999981 | |||||||||||

| Segment | Pu | FLS | Pmin |

Pmax |

Pamp |

Pmean |

R |

A |

Pmax /Pu |

n |

Nf |

n/Nf |

||

| MF | WL | FLS1 | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 931 | 1.0 | 87.5 | 122.5 | 15 | 137.50 | 61.25 | 76.25 | 0.109 | 0.803 | 0.147 | 100,000 | 3,015,323,194 | 3.316E-05 |

| 2 | 931 | 1.5 | 87.5 | 183.8 | 15 | 198.75 | 91.88 | 106.88 | 0.075 | 0.860 | 0.213 | 100,000 | 559,277,378 | 0.0001788 |

| 3 | 931 | 2.0 | 87.5 | 245.0 | 15 | 260.00 | 122.50 | 137.50 | 0.057 | 0.890 | 0.279 | 100,000 | 103,733,884 | 0.000964 |

| 4 | 931 | 2.5 | 87.5 | 306.3 | 15 | 321.25 | 153.13 | 168.13 | 0.046 | 0.911 | 0.345 | 100,000 | 19,240,397 | 0.0051974 |

| 5 | 931 | 3.0 | 87.5 | 367.5 | 15 | 382.50 | 183.75 | 198.75 | 0.039 | 0.925 | 0.411 | 100,000 | 3,568,678 | 0.0280216 |

| 6 | 931 | 3.5 | 87.5 | 428.8 | 15 | 443.75 | 214.38 | 229.38 | 0.034 | 0.935 | 0.477 | 100,000 | 661,913 | 0.1510773 |

| 7 | 931 | 4.0 | 87.5 | 490.0 | 15 | 505.00 | 245.00 | 260.00 | 0.030 | 0.942 | 0.542 | 100,000 | 122,771 | 0.8145276 |

| 8 | 931 | 4.0 | 87.5 | 490.0 | 15 | 505.00 | 245.00 | 260.00 | 0.030 | 0.942 | 0542 | 100,000 | 122,771 | 0.8145276 |

| 9 | 931 | 4.0 | 87.5 | 490.0 | 15 | 505.00 | 245.00 | 260.00 | 0.030 | 0.942 | 0.542 | 95,000 | 122,771 | 0.7738013 |

| 10 | 931 | 4.0 | 87.5 | 490.0 | 15 | 505.00 | 245.00 | 260.00 | 0.030 | 0.942 | 0.542 | 21,736 | 122,771 | 0.1770457 |

| 11 | 931 | 4.0 | 87.5 | 490.0 | 15 | 505.00 | 245.00 | 260.00 | 0.030 | 0.942 | 0.542 | 44,804 | 122,771 | 0.364941 |

| Total | 961,540 | Σn/N | 0.9999999 | |||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).