Submitted:

28 August 2024

Posted:

28 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

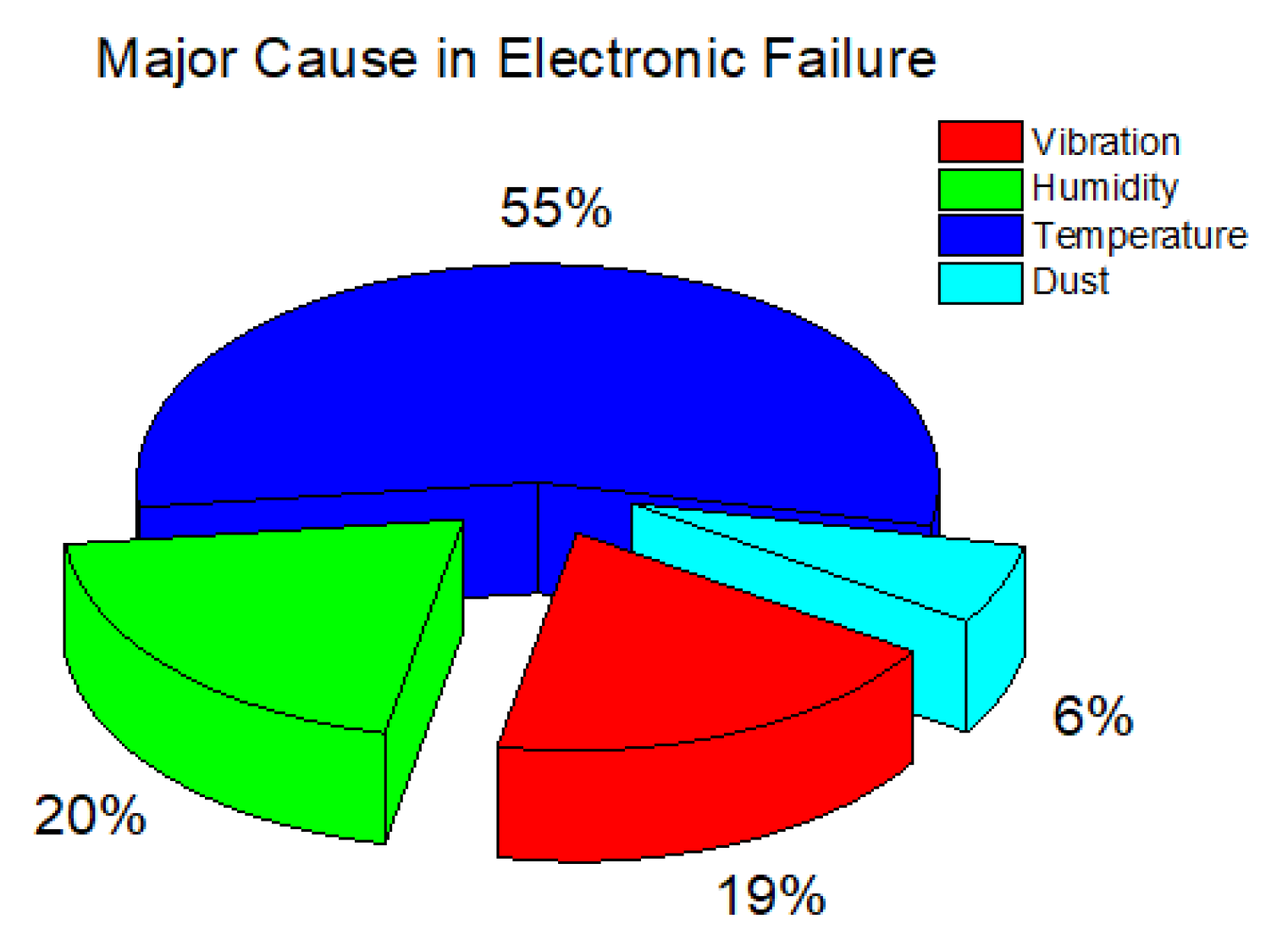

1. Introduction

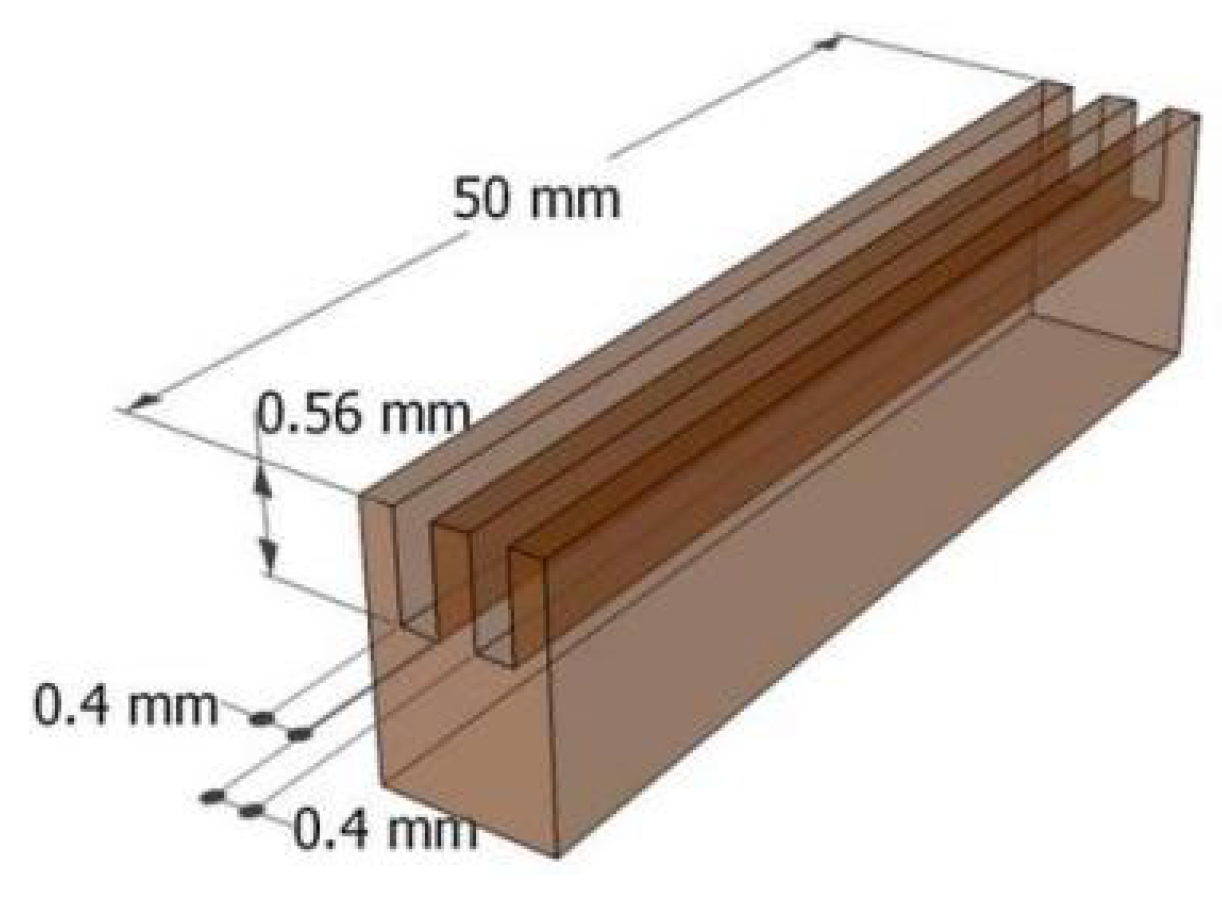

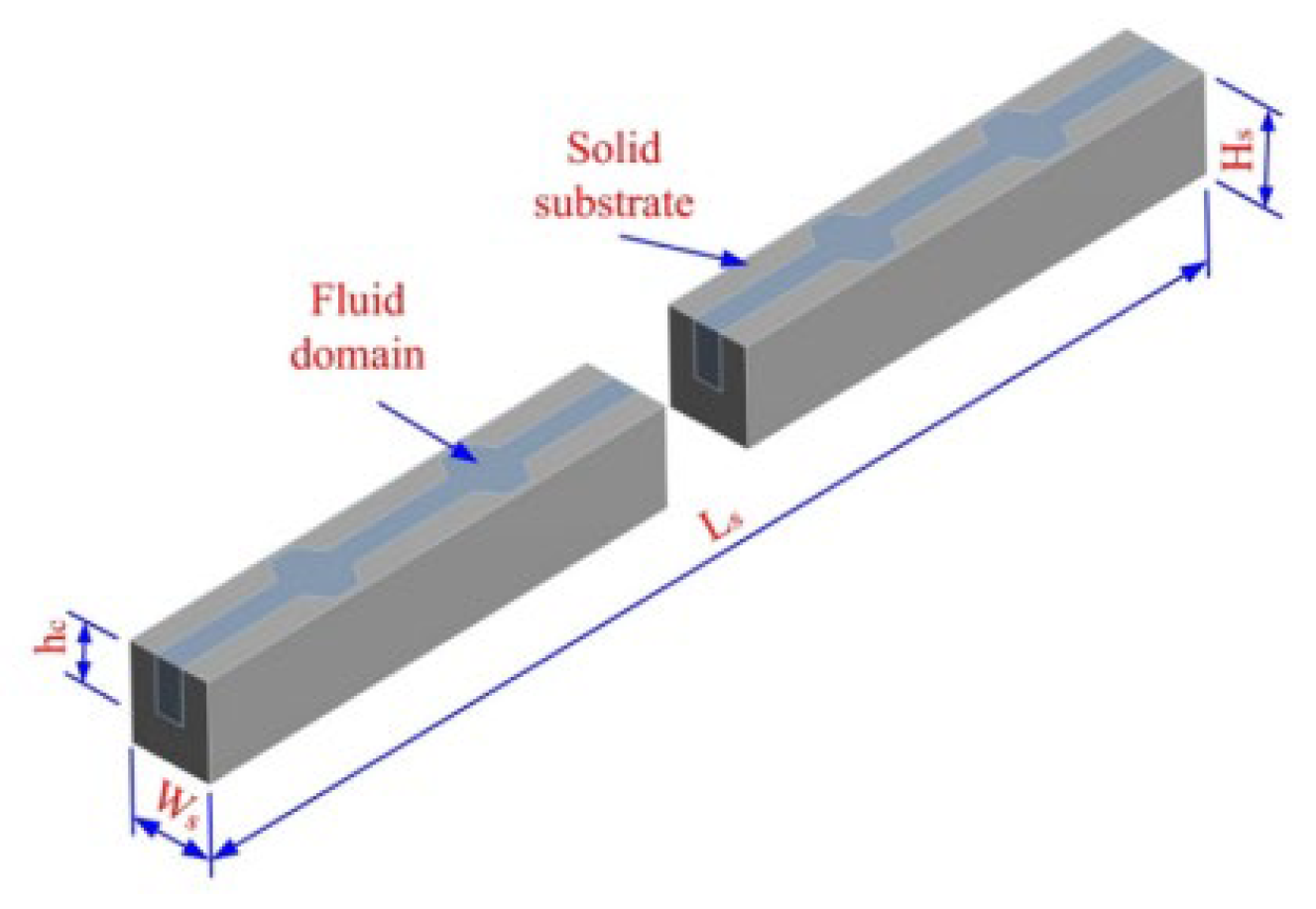

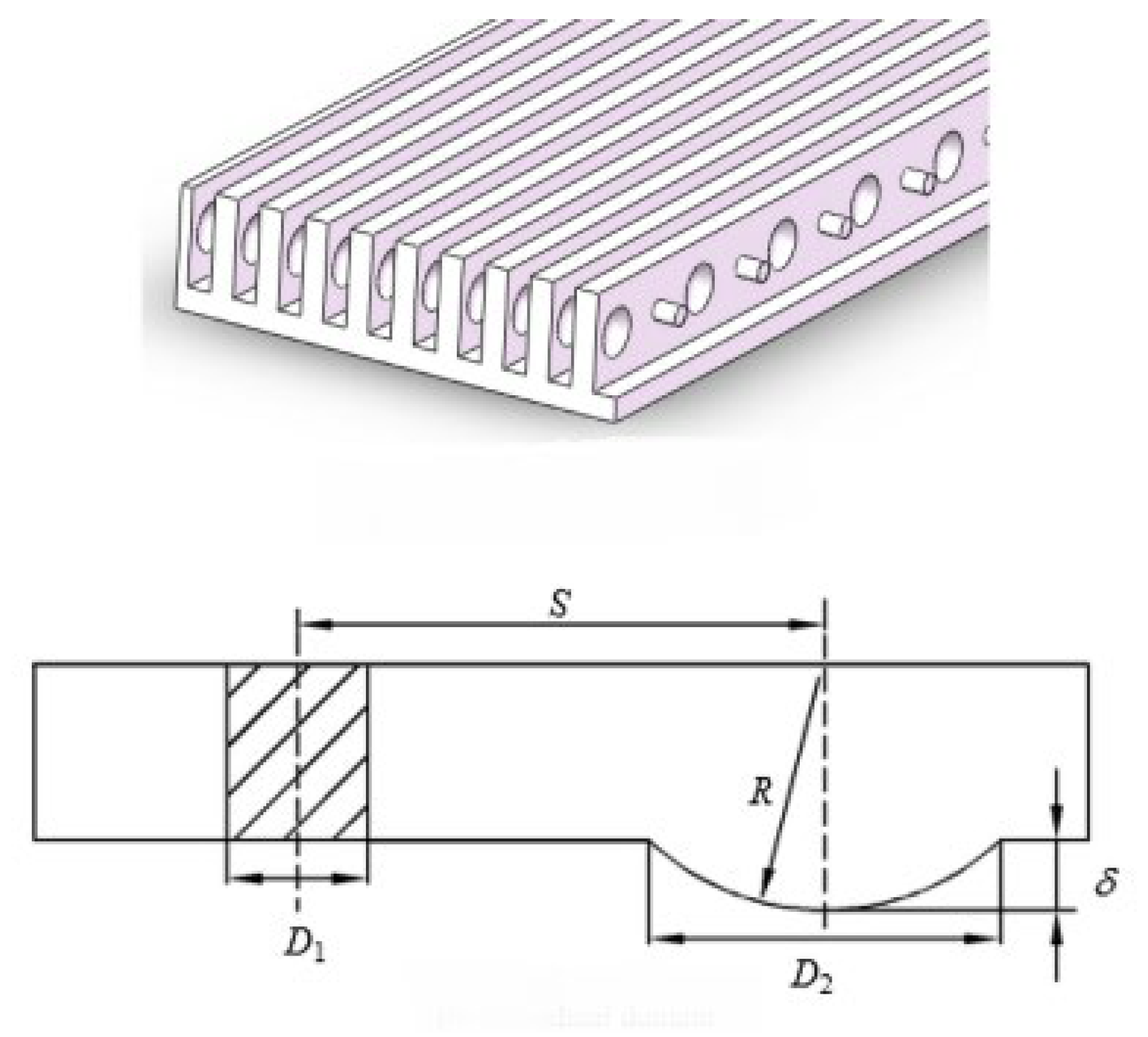

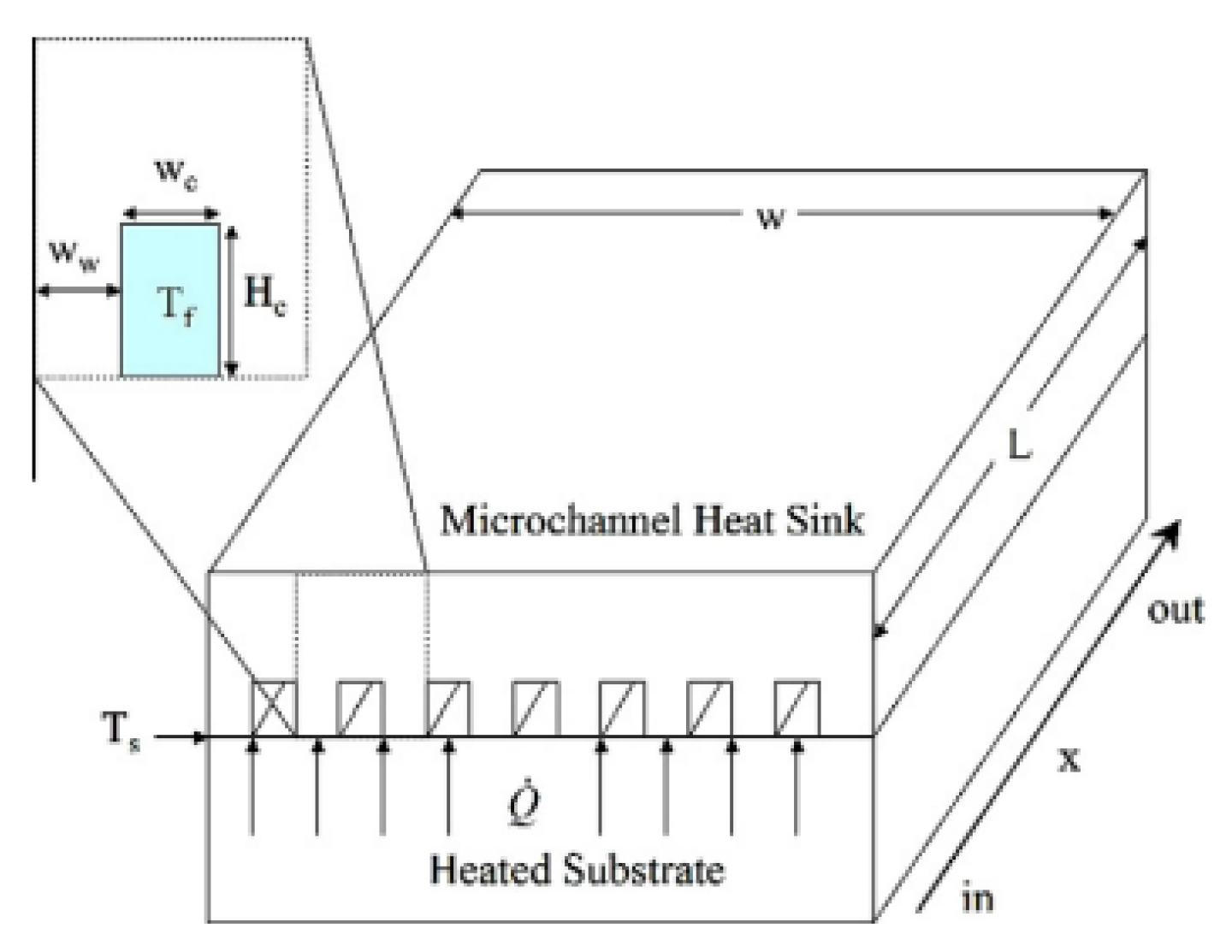

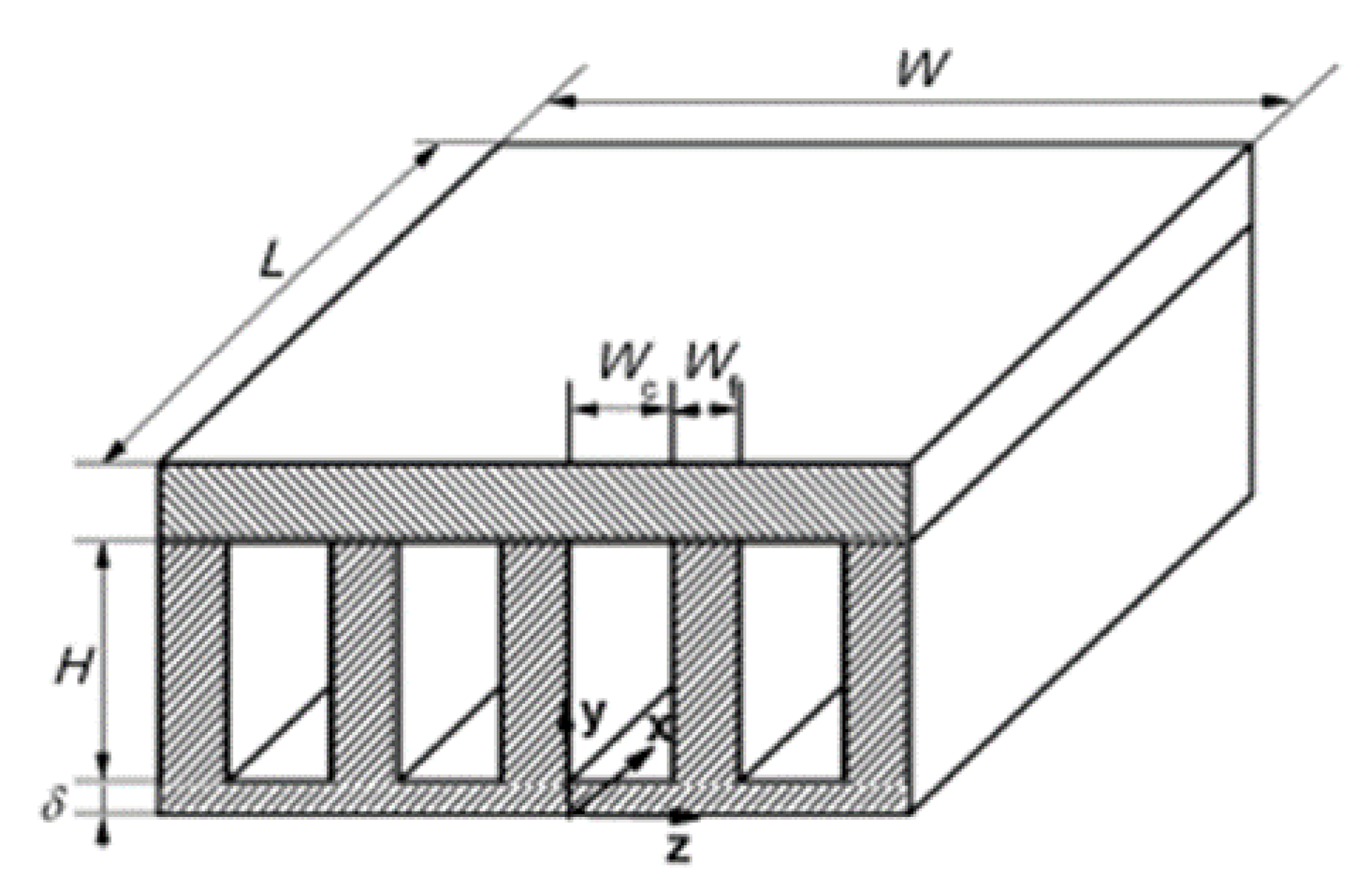

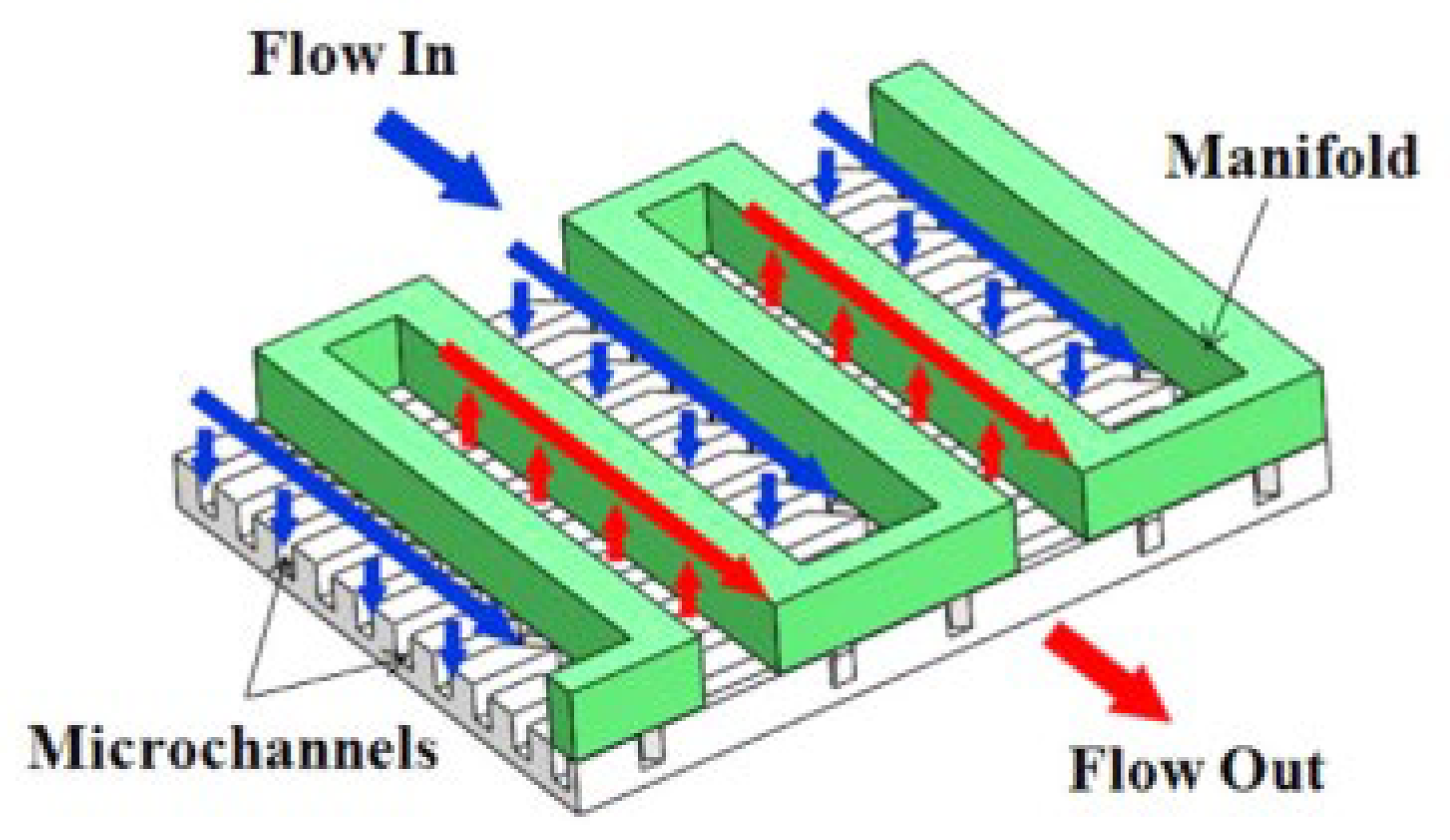

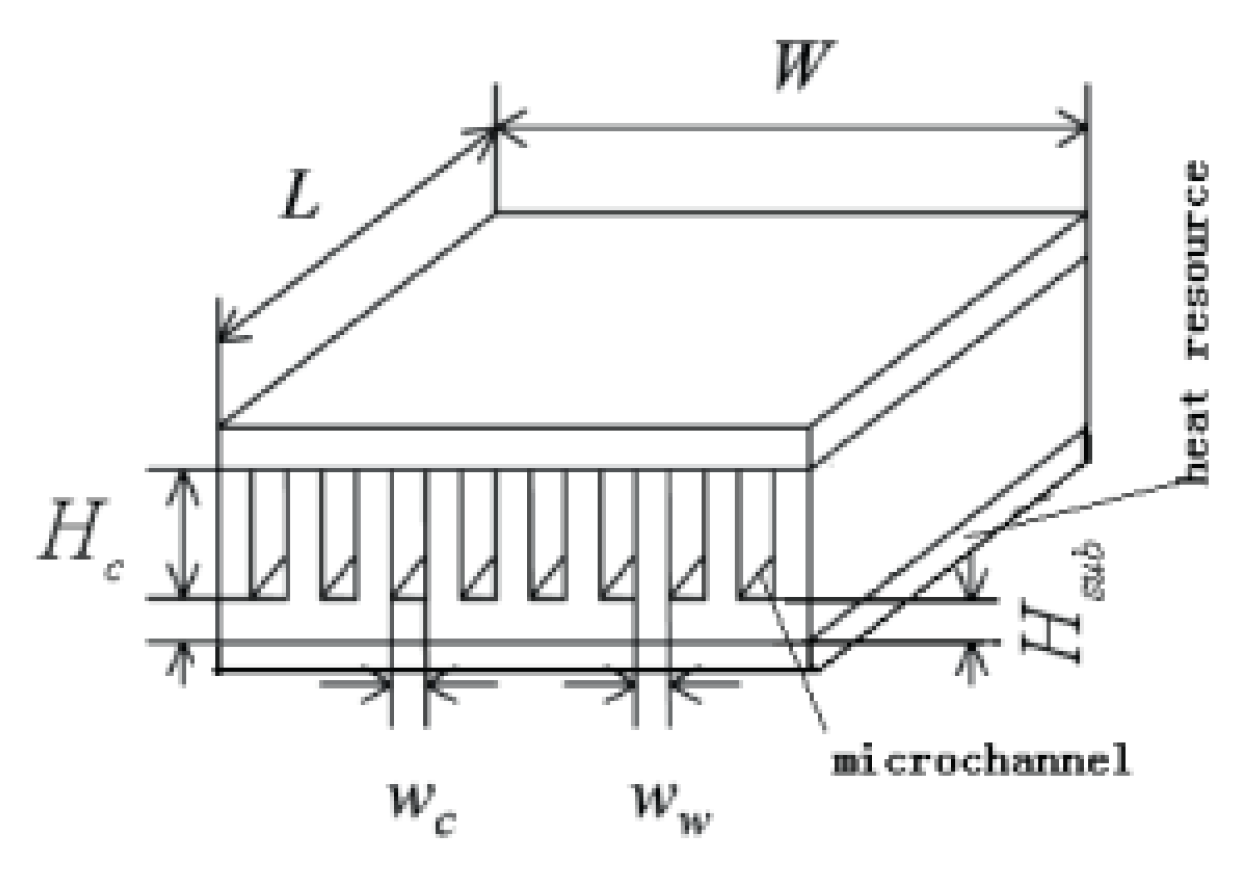

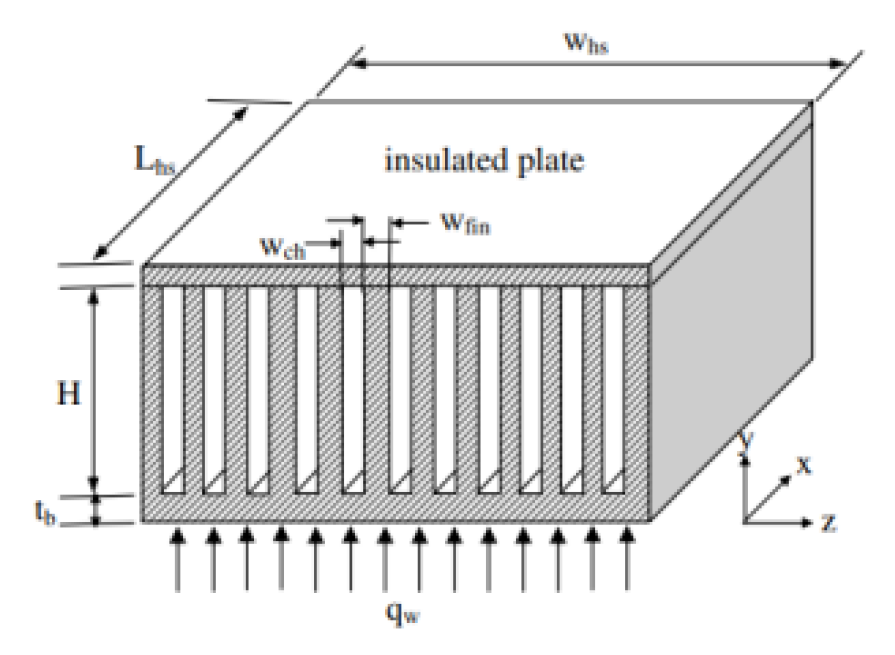

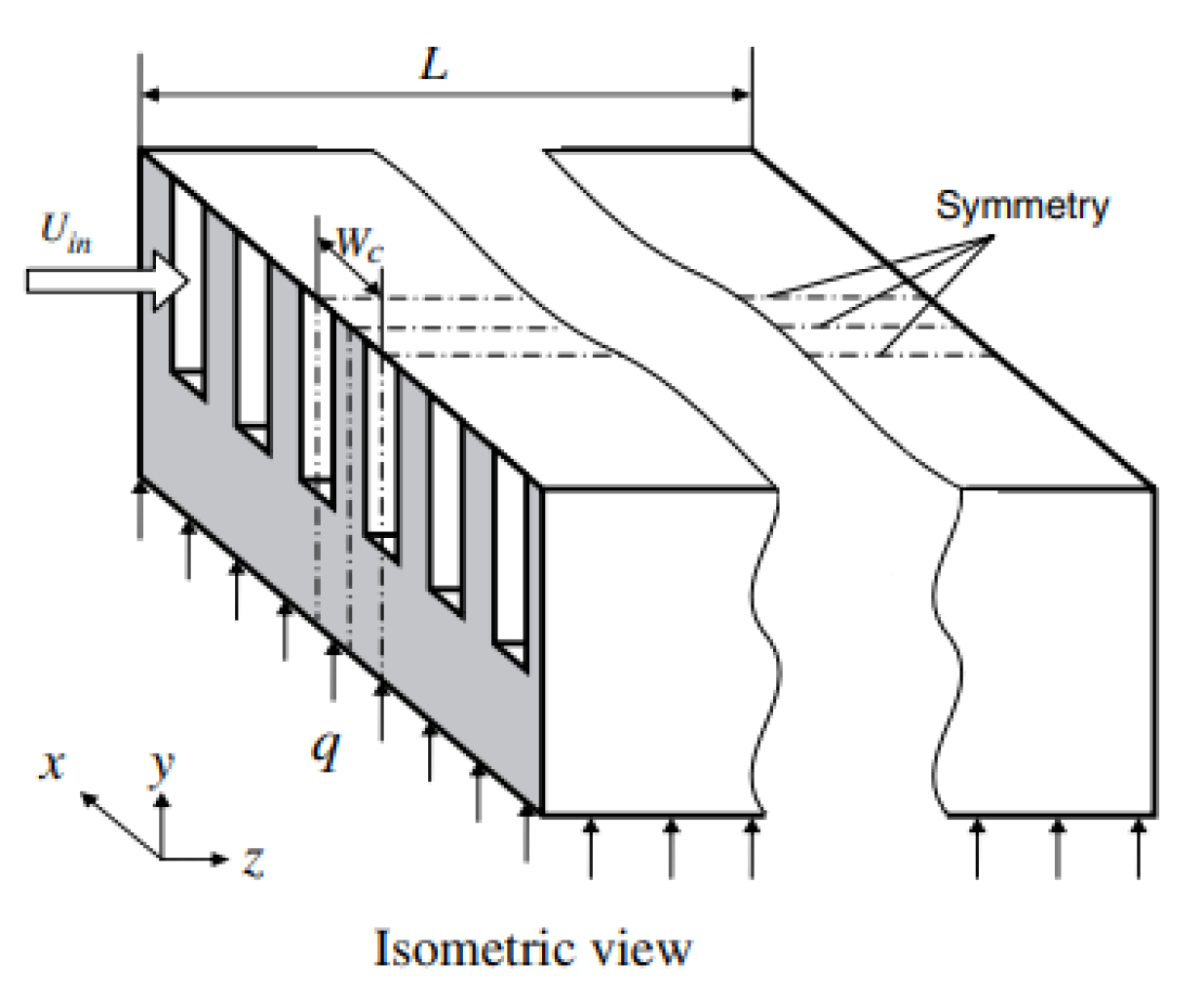

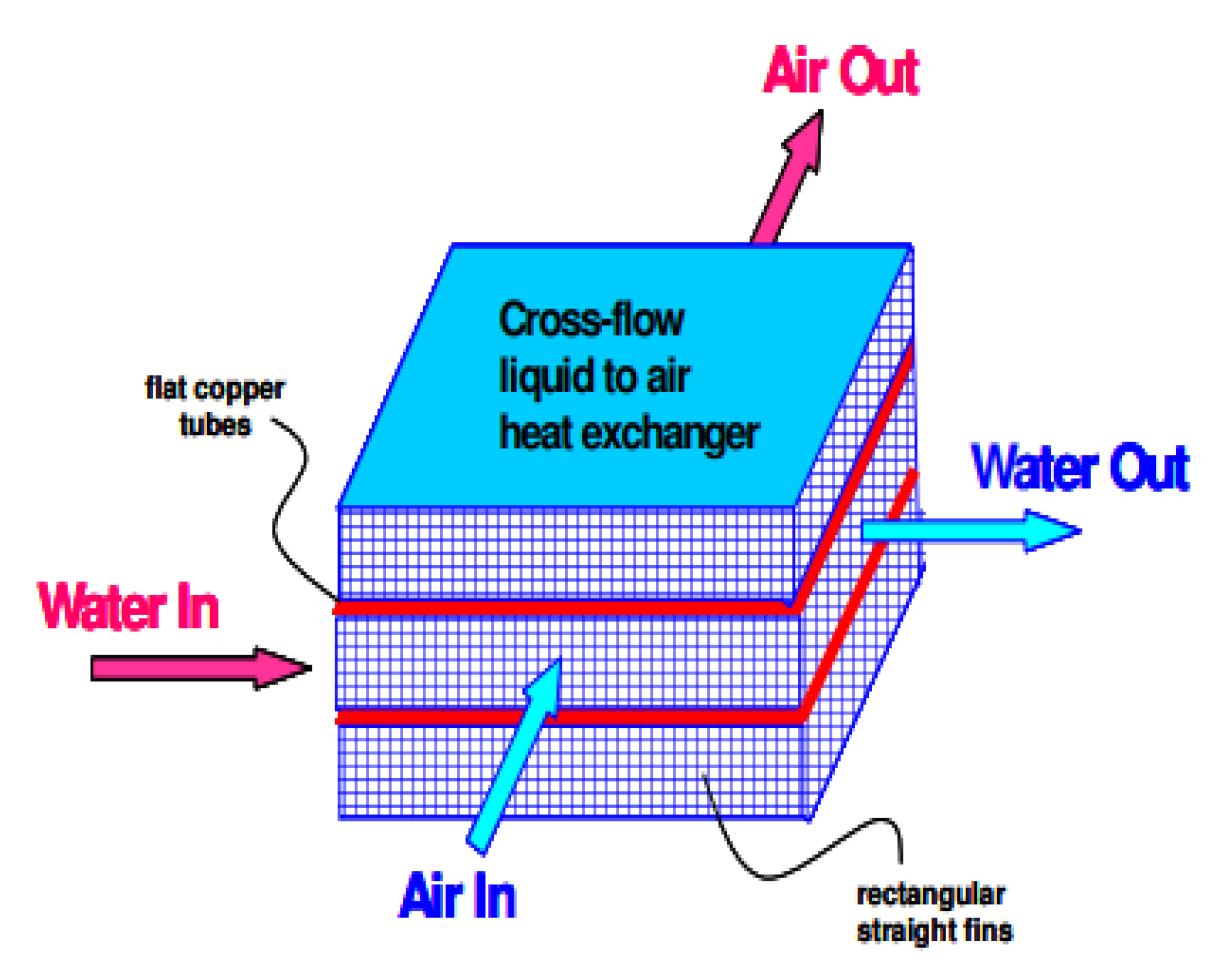

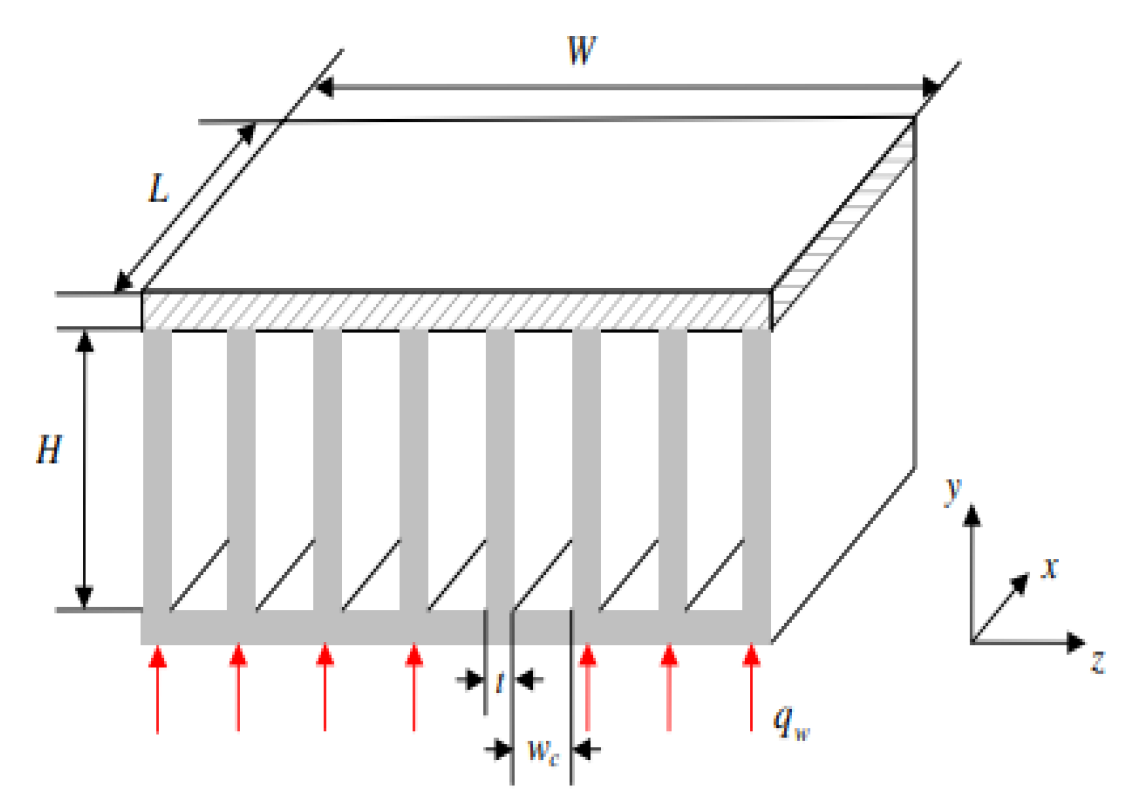

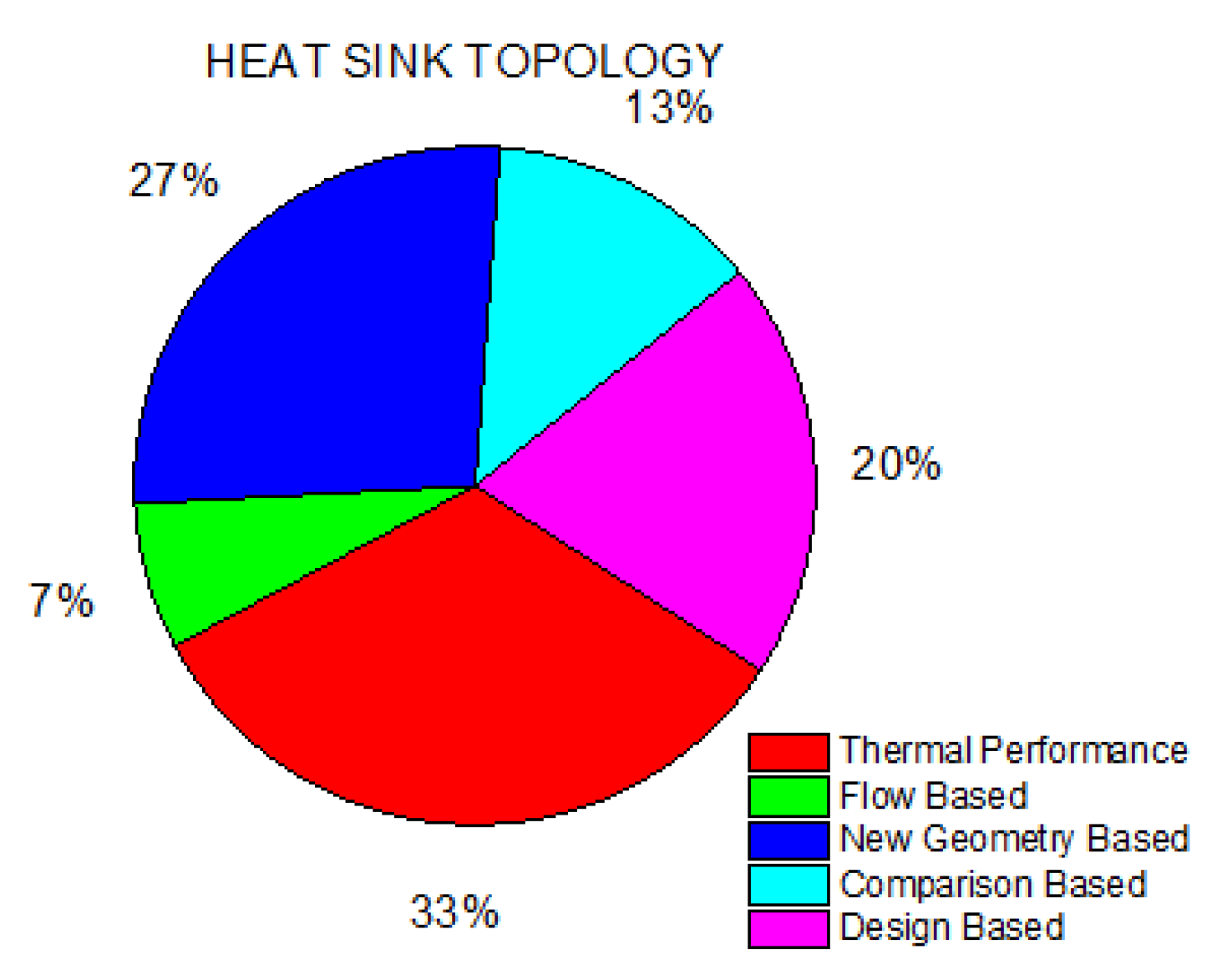

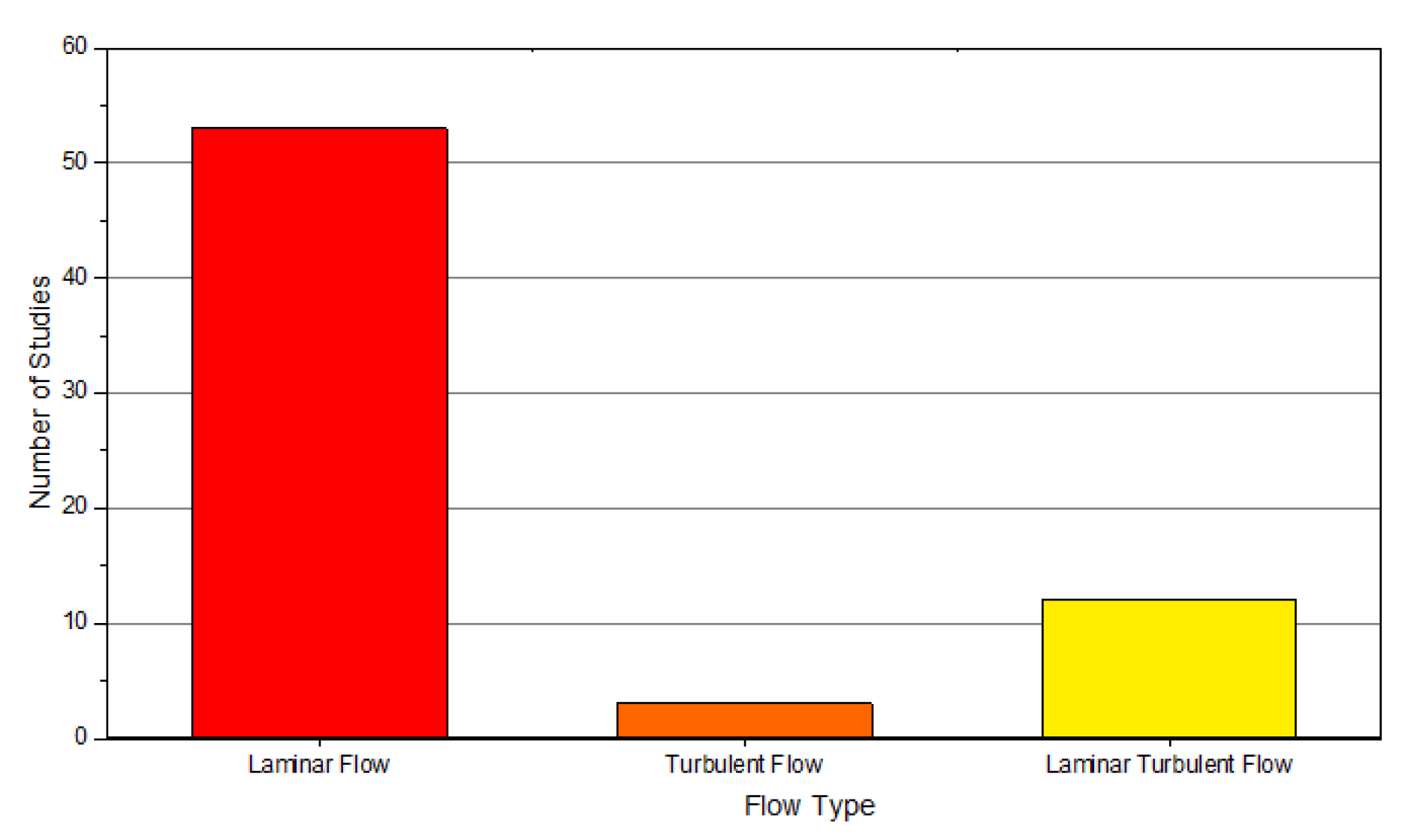

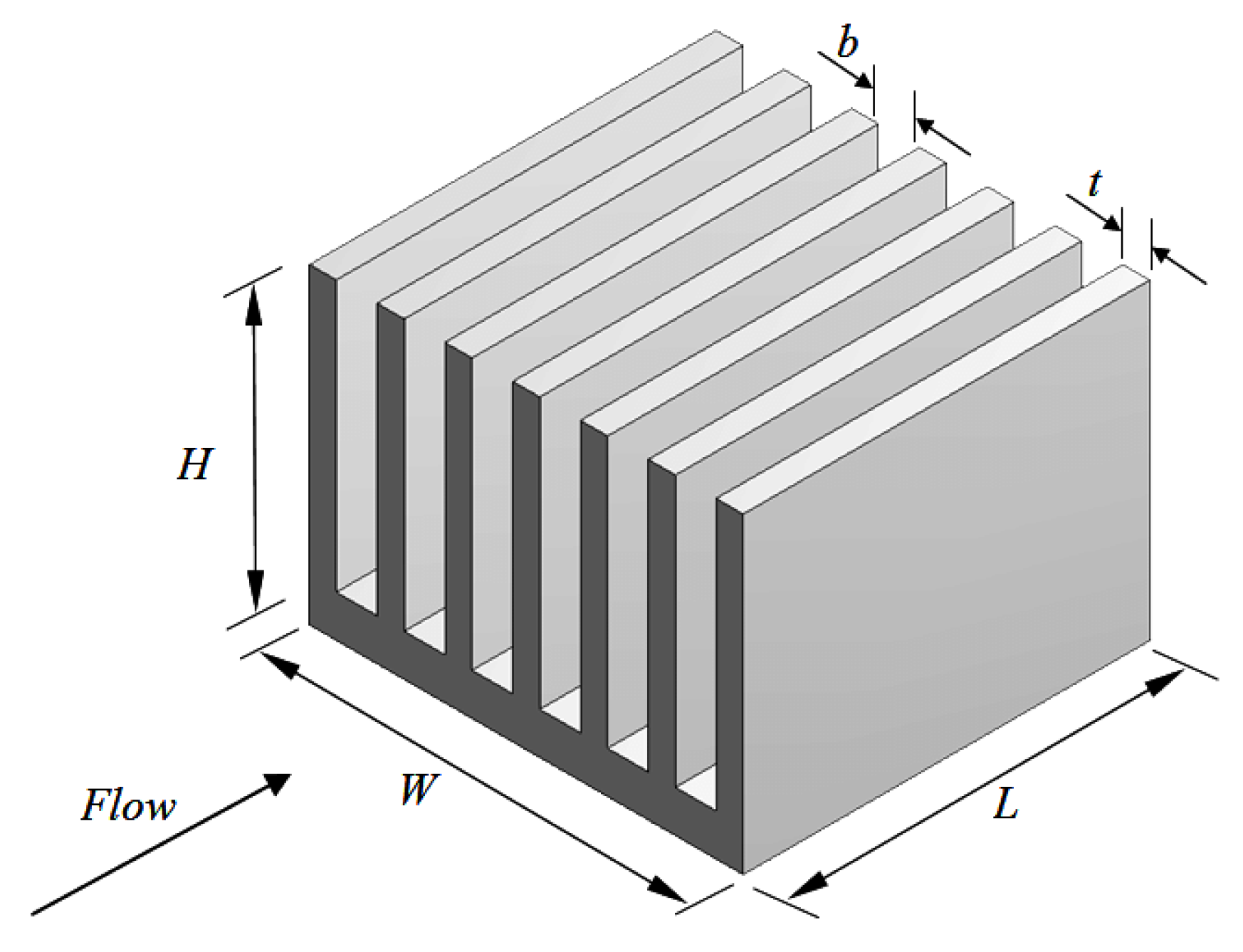

Microchannel Heat Sink (MCHS)

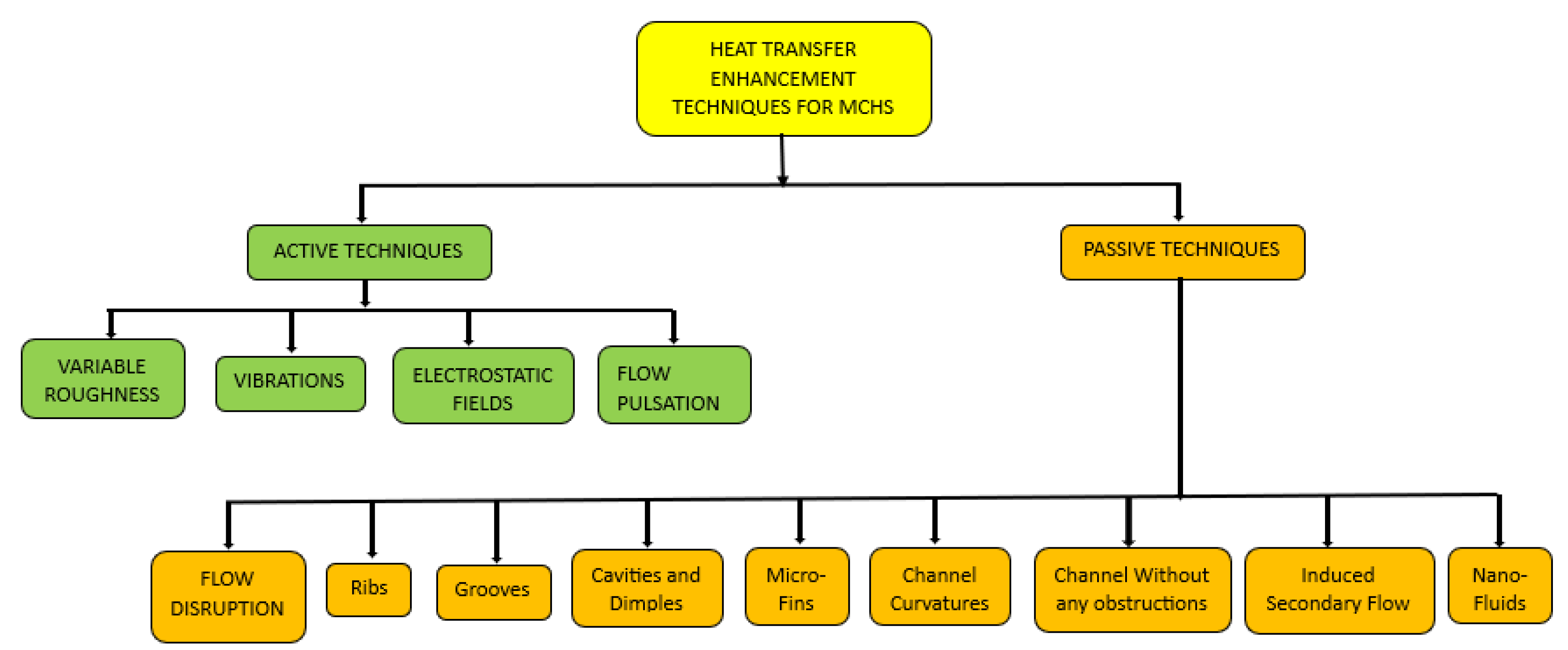

2. Methods Used to Enhance the Thermal Efficiency of MCHS

2.1. Active Techniques

2.2. Passive Techniques

2.2.1. Flow Disruption Technique

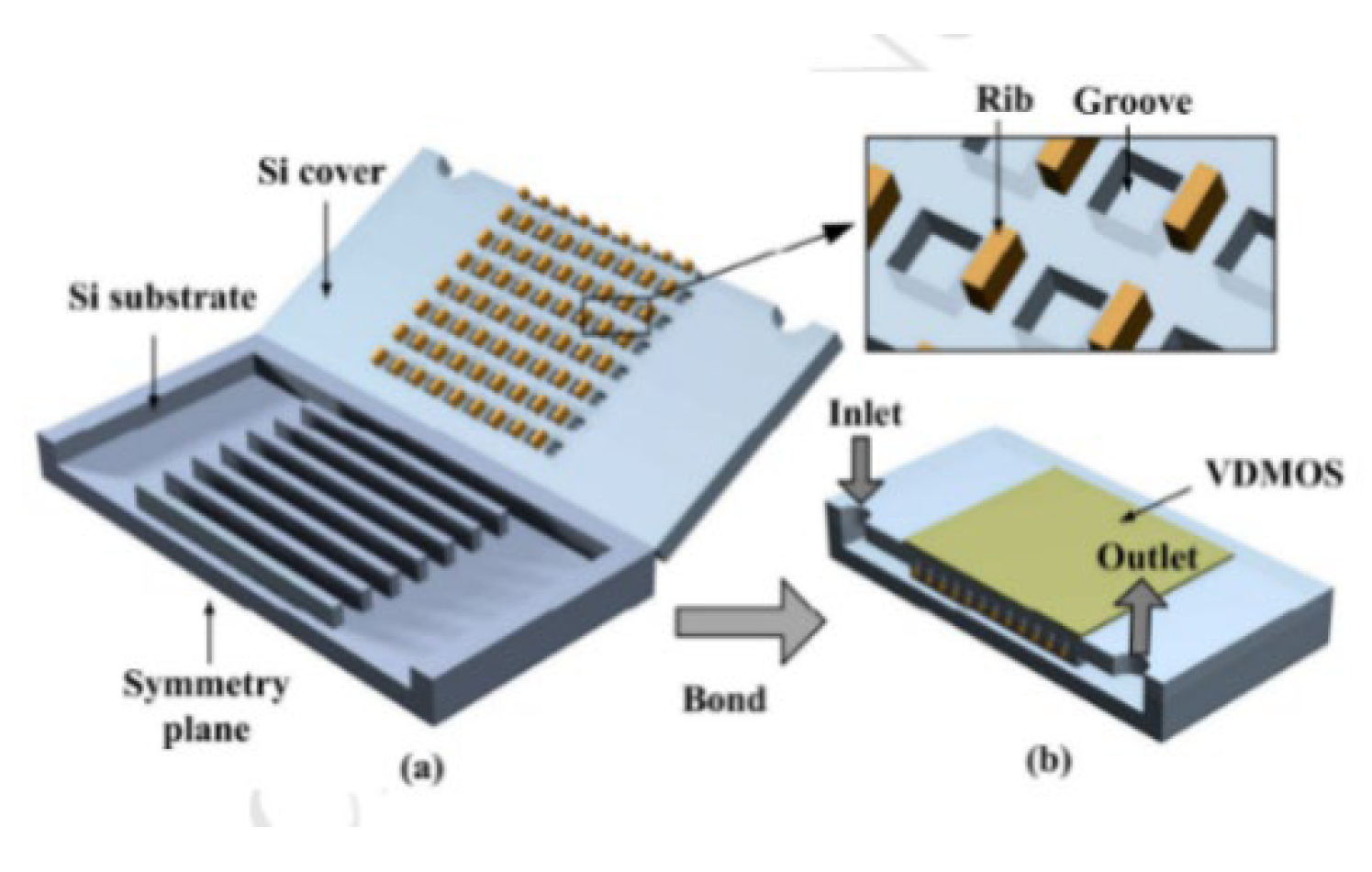

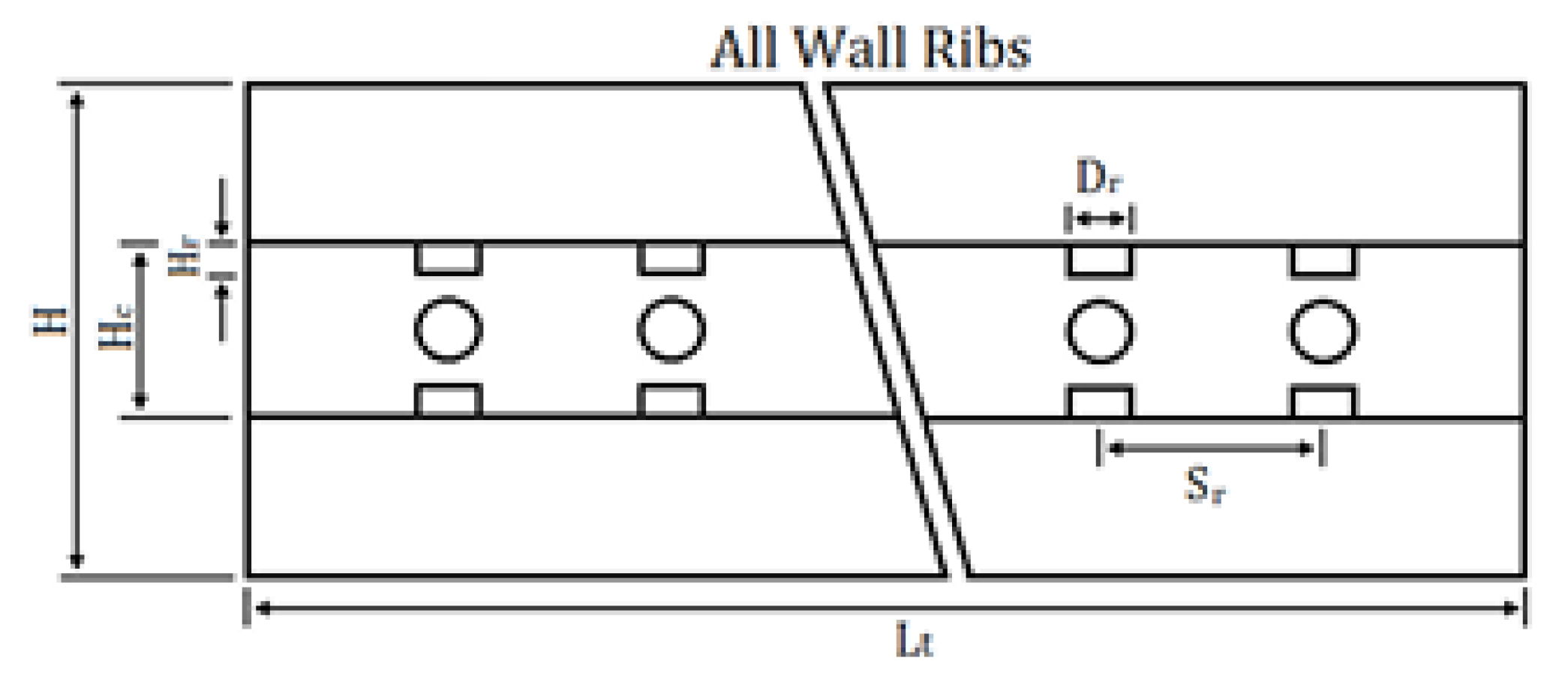

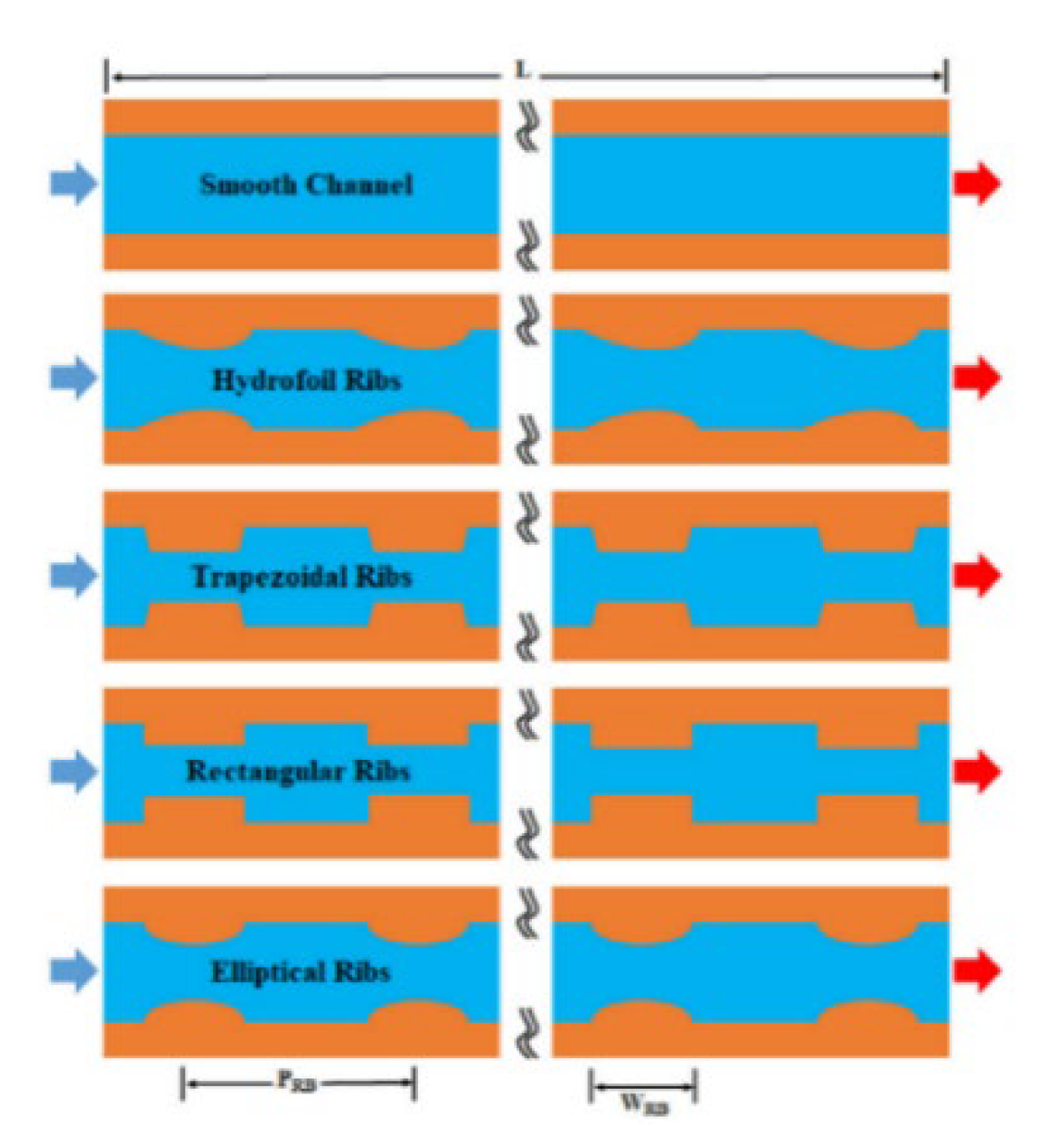

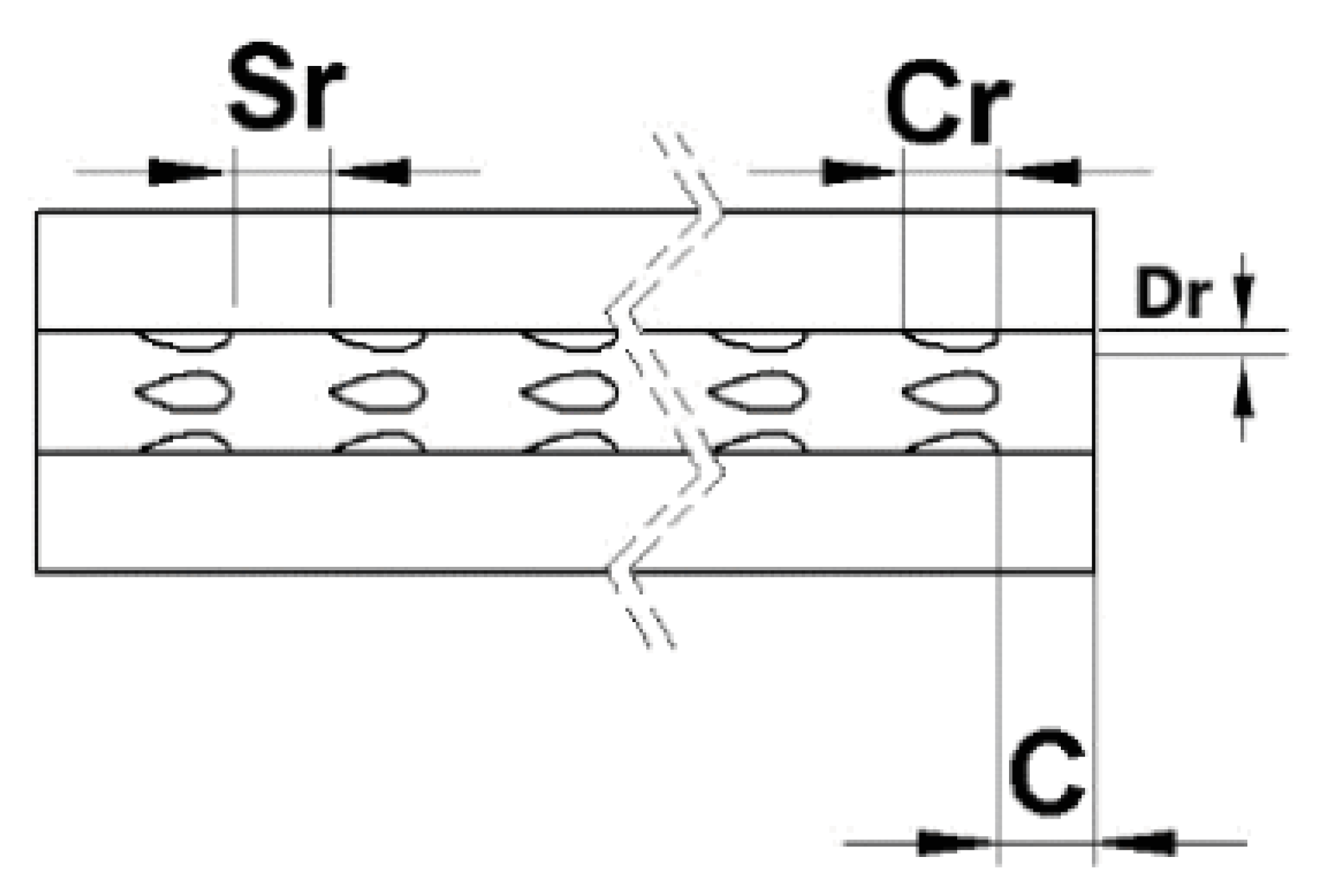

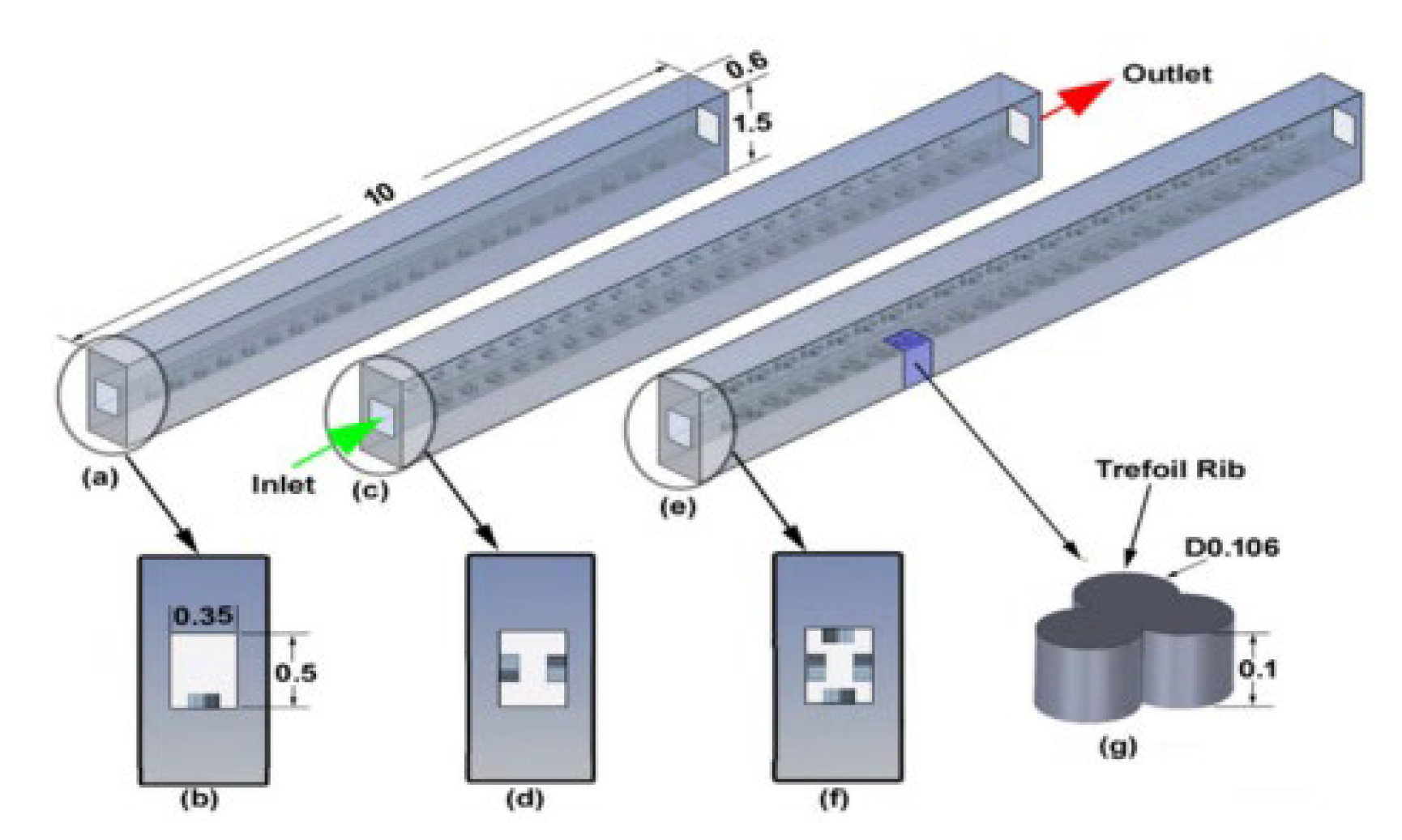

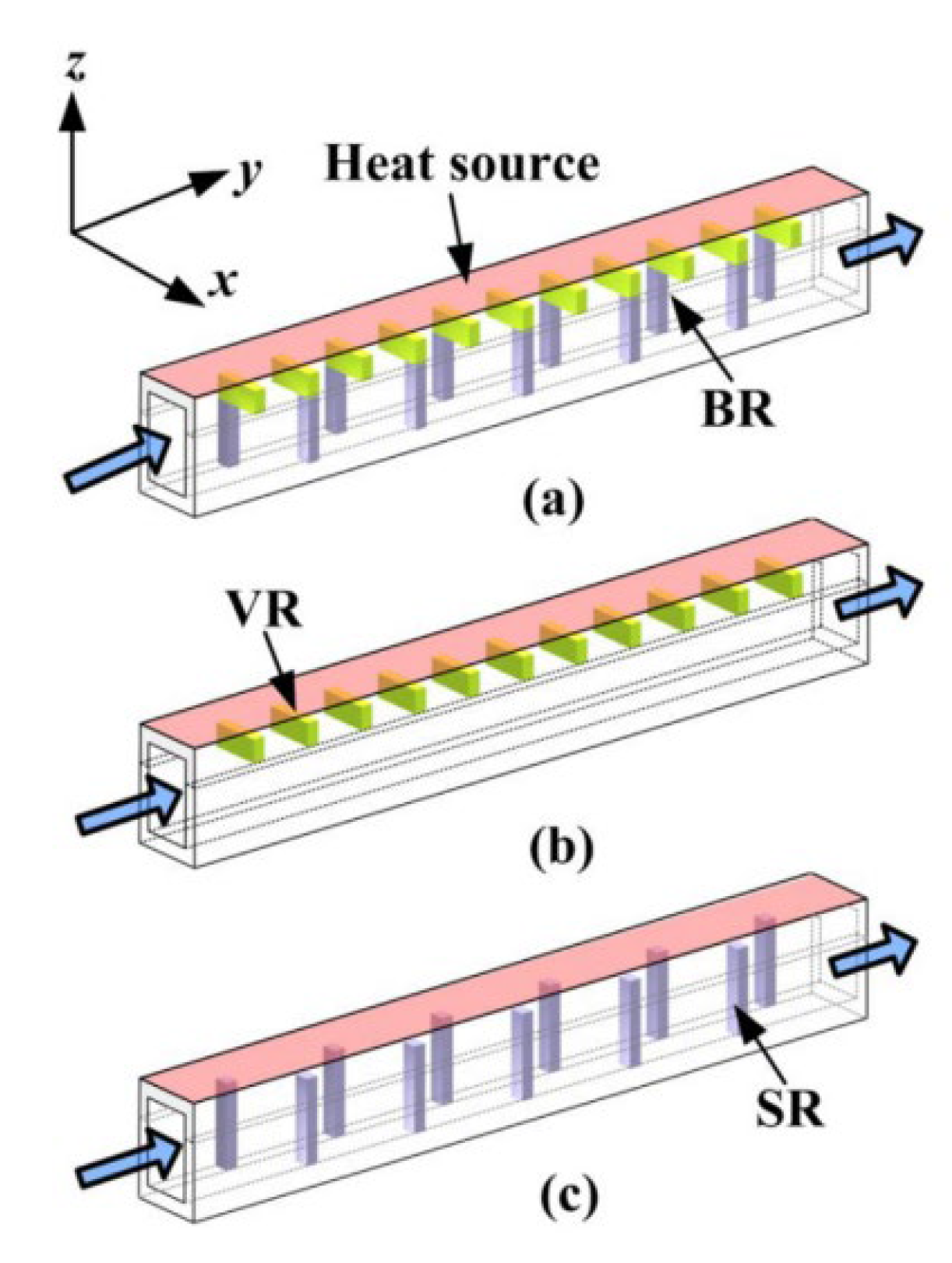

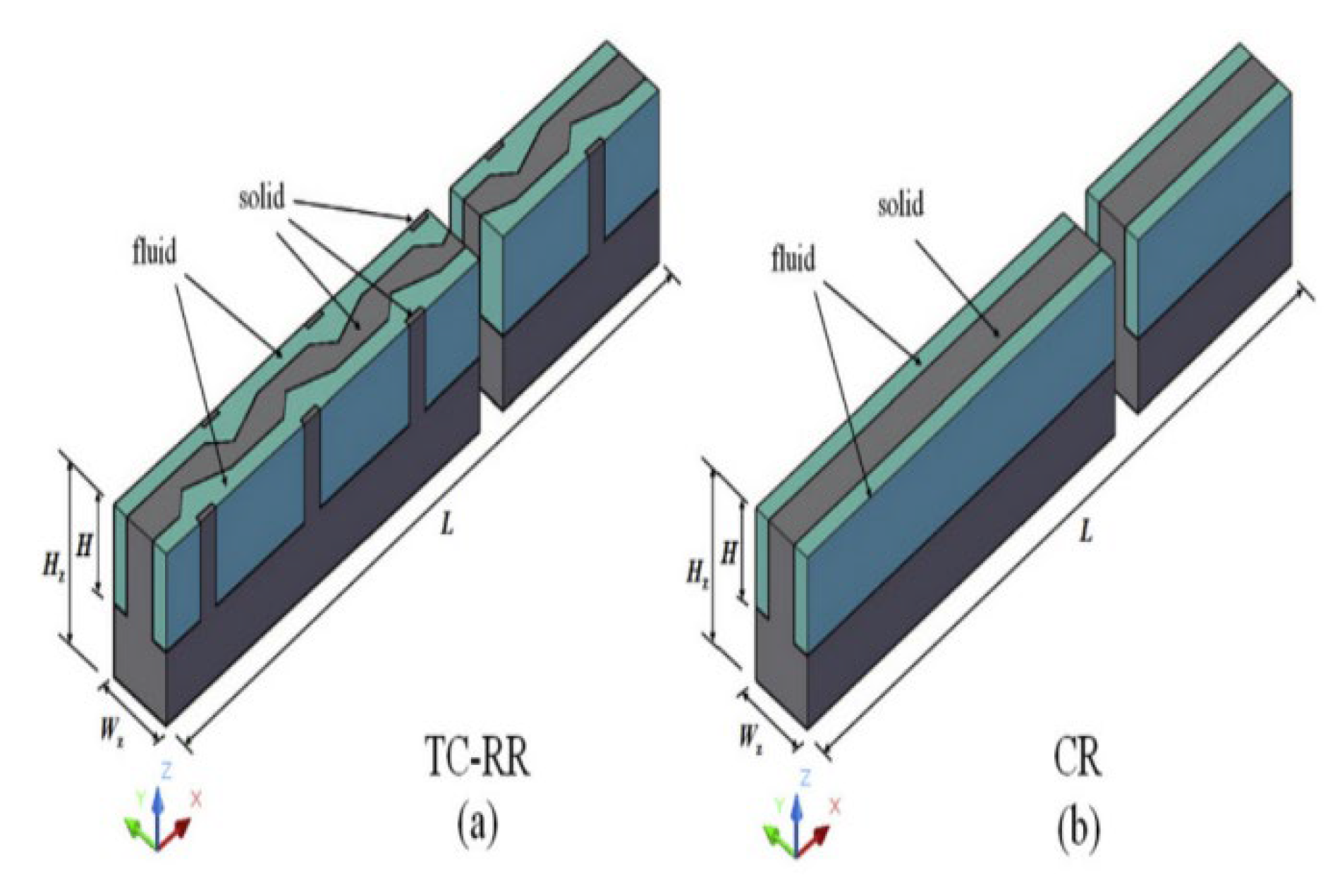

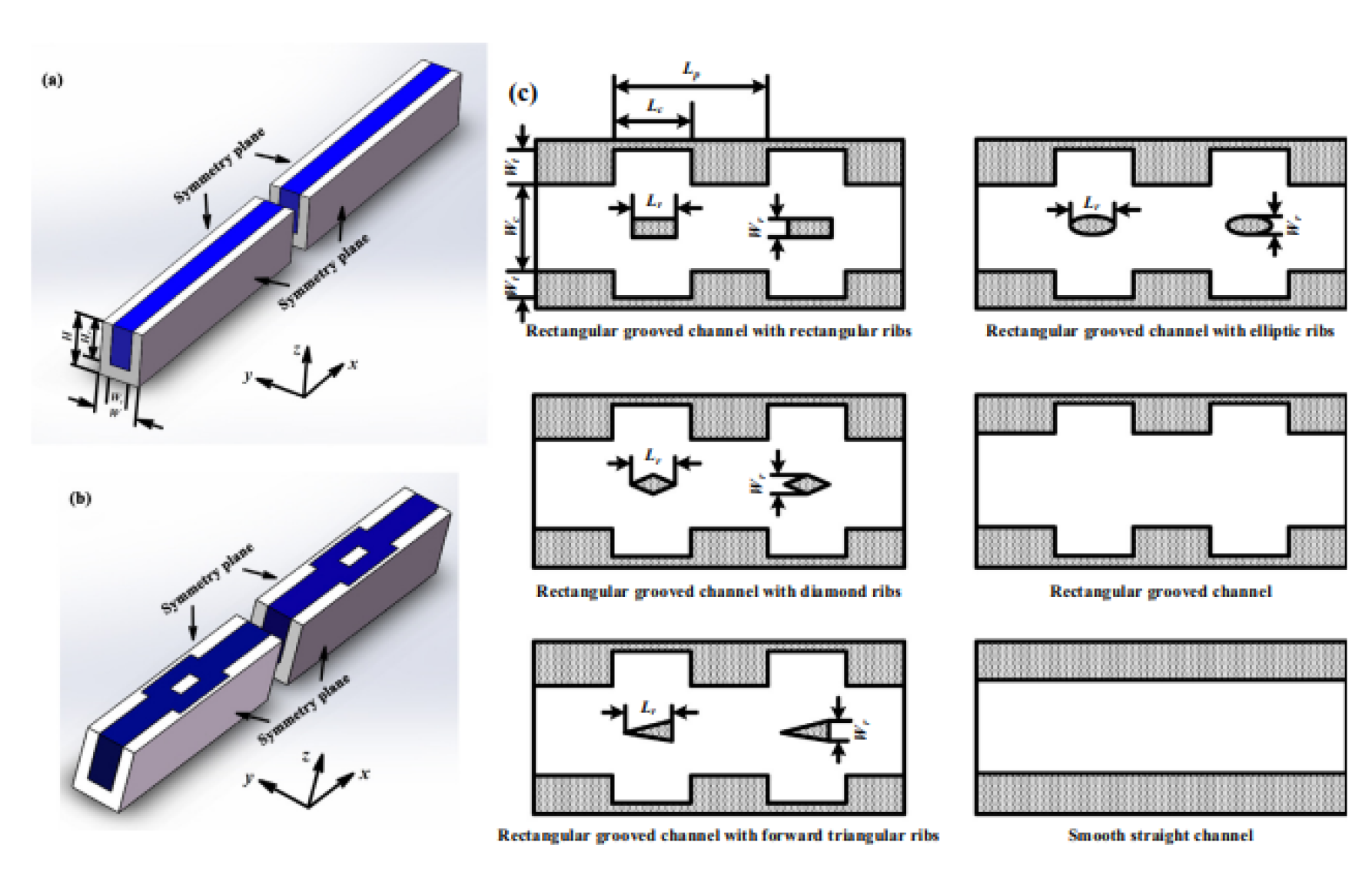

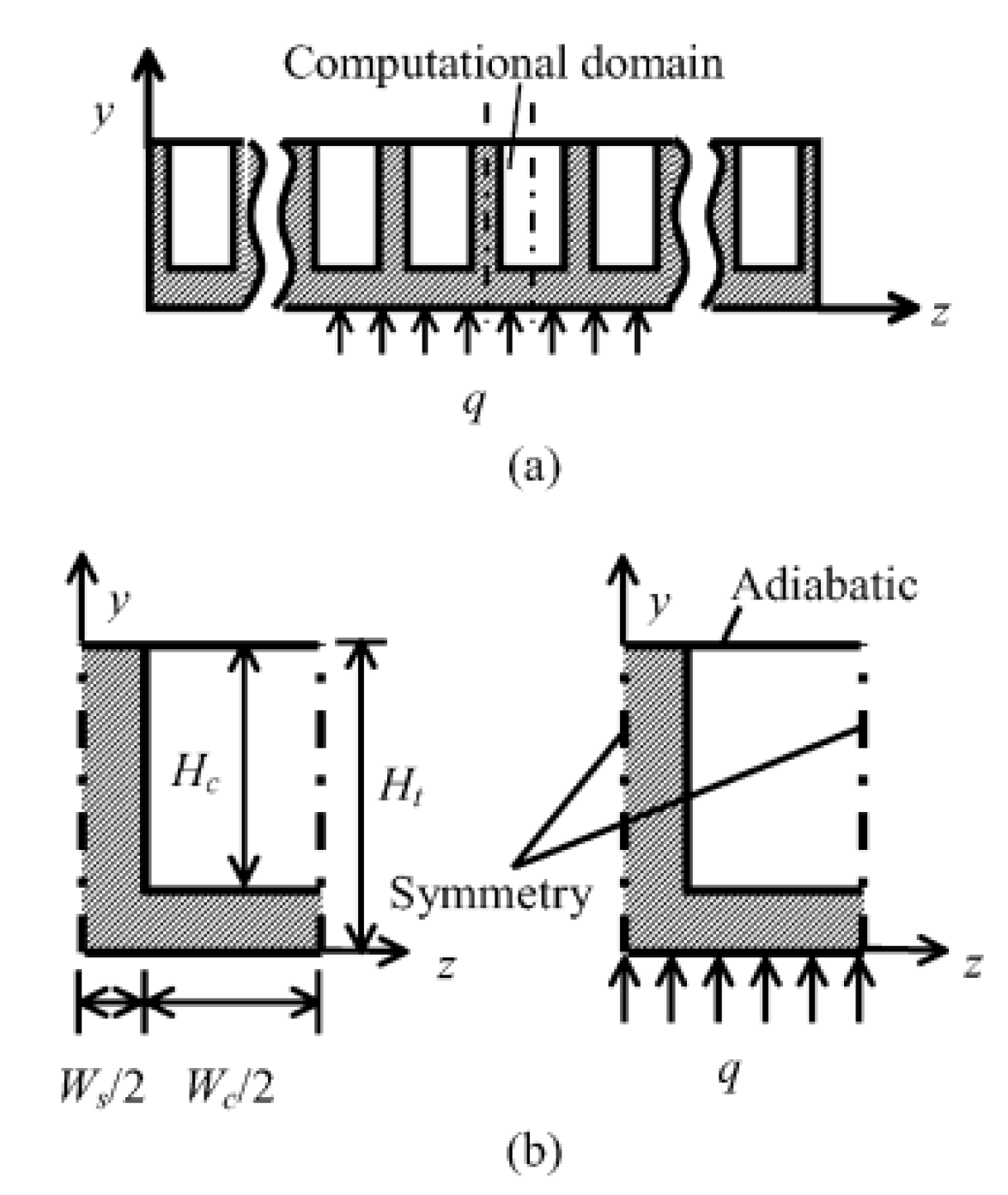

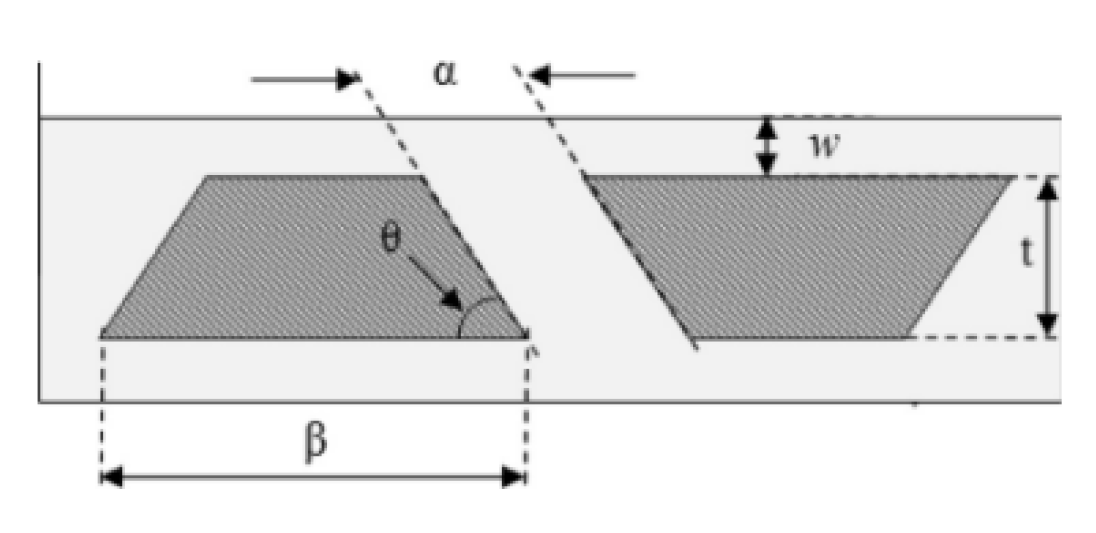

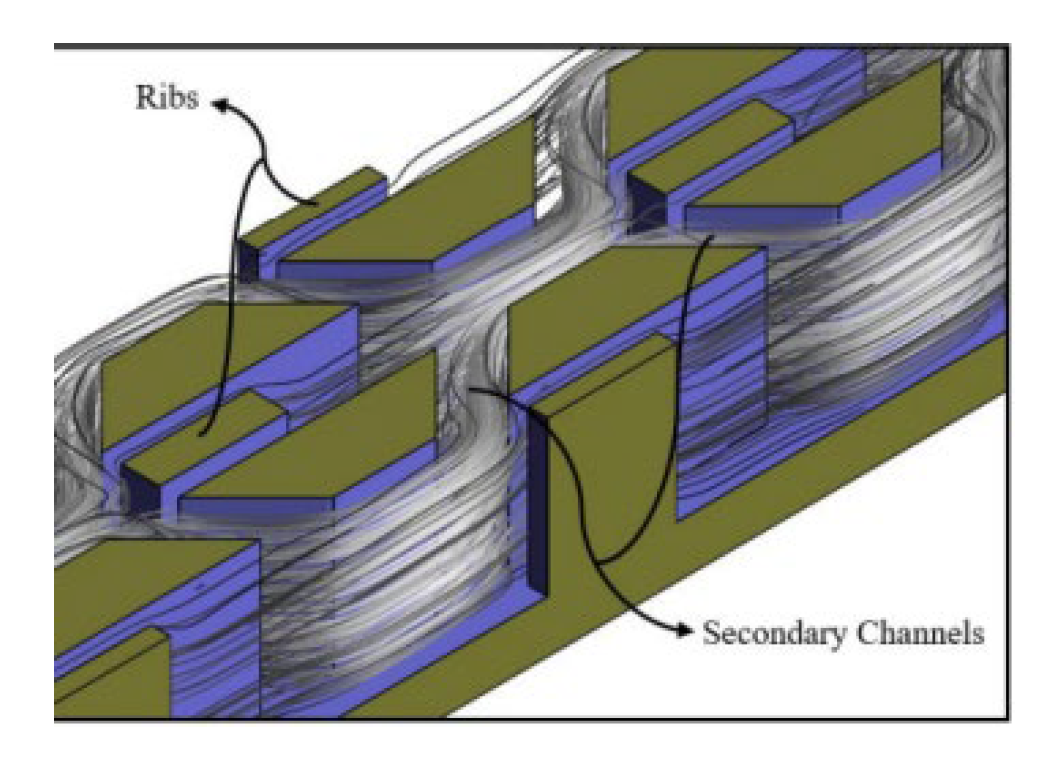

2.2.2. Ribs

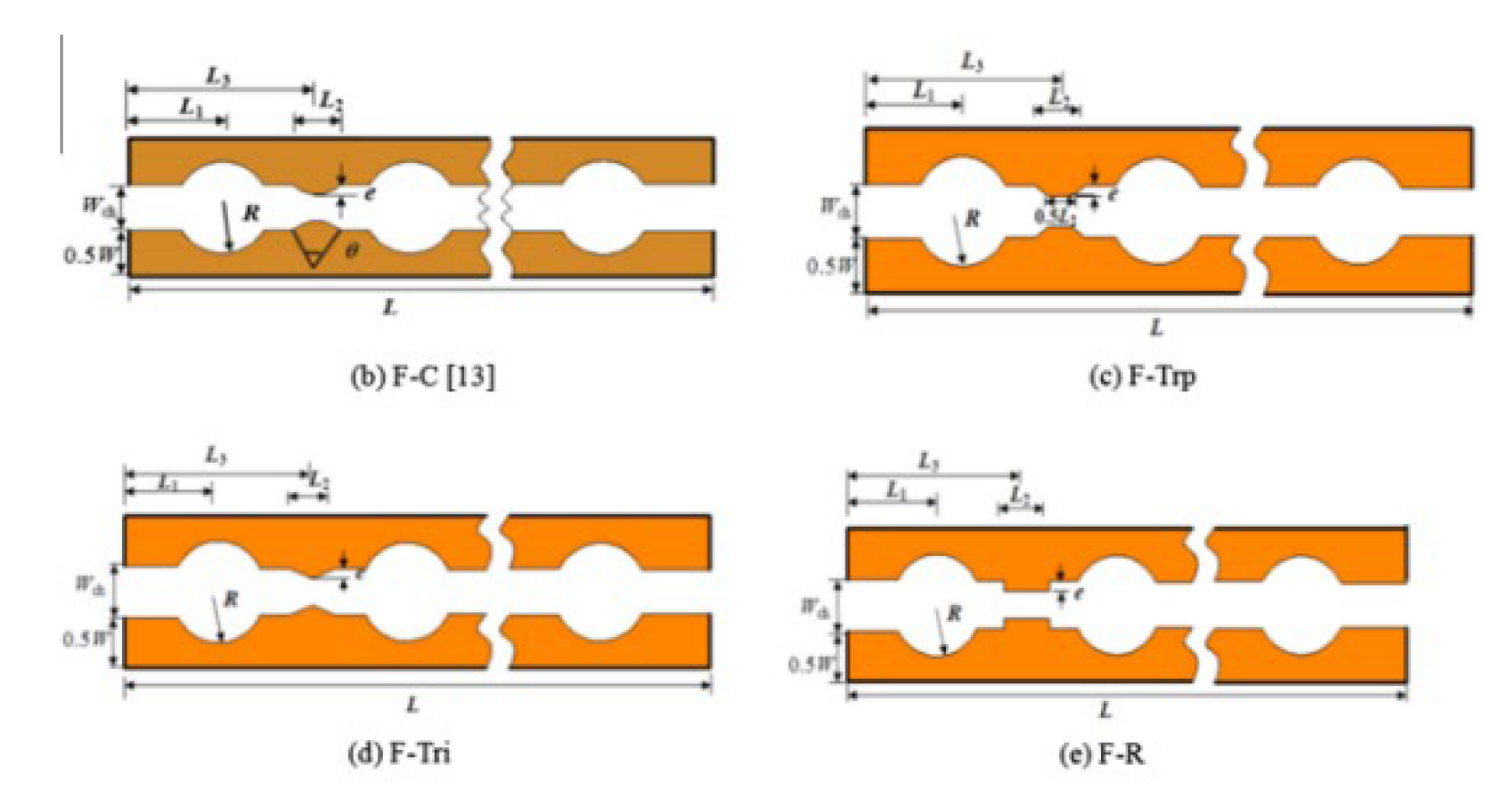

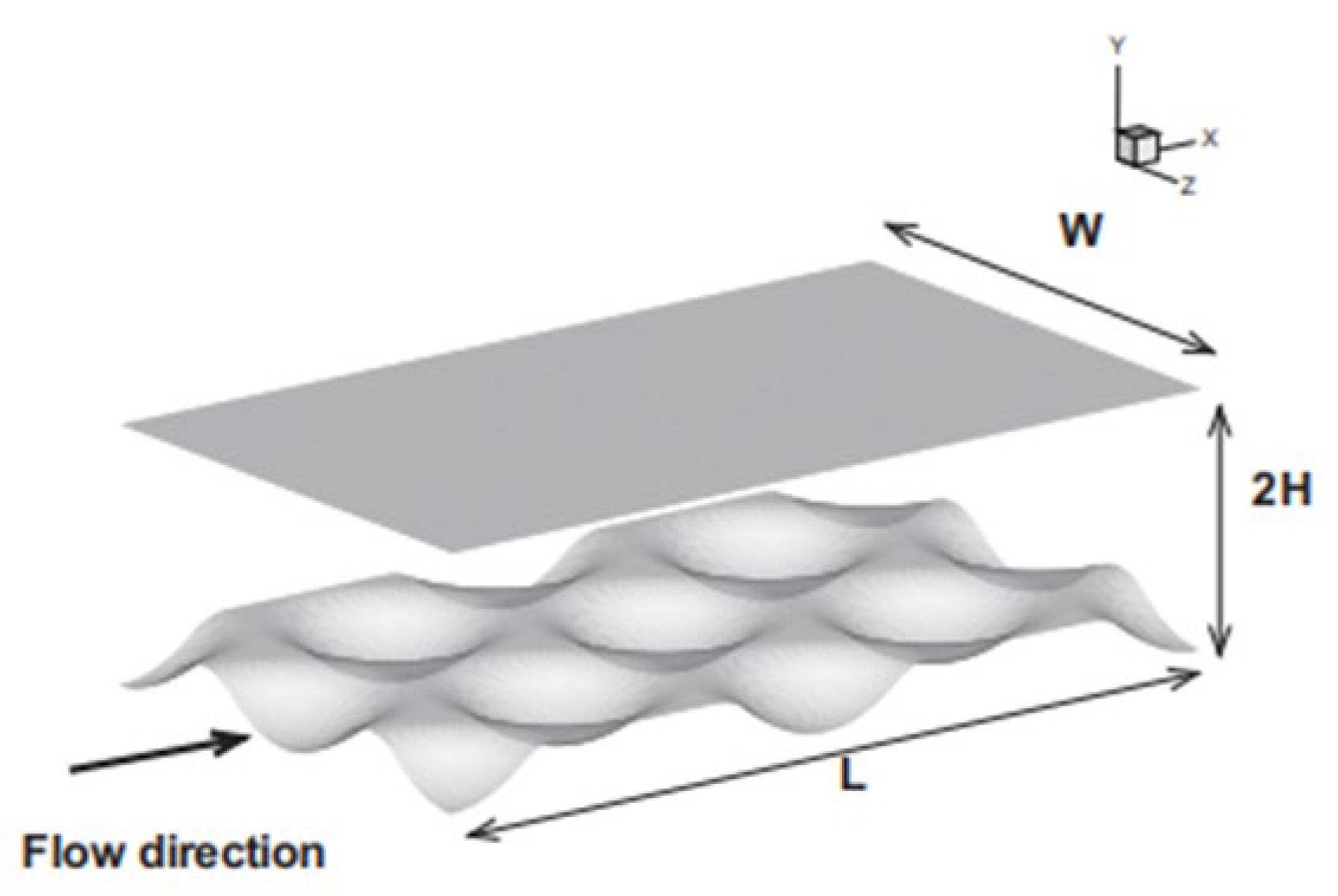

2.2.3. Grooves

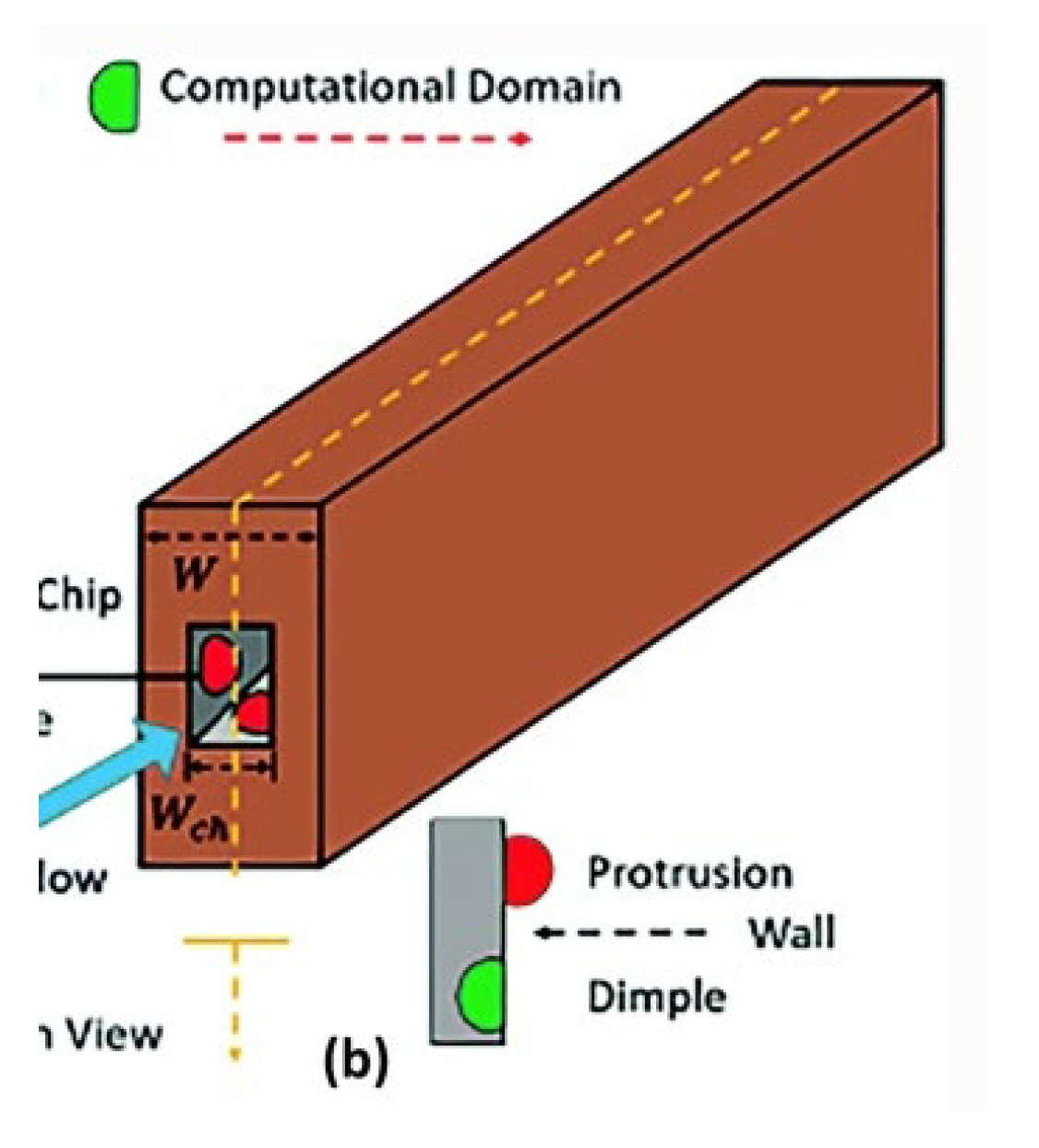

2.2.4. Cavities and Dimples

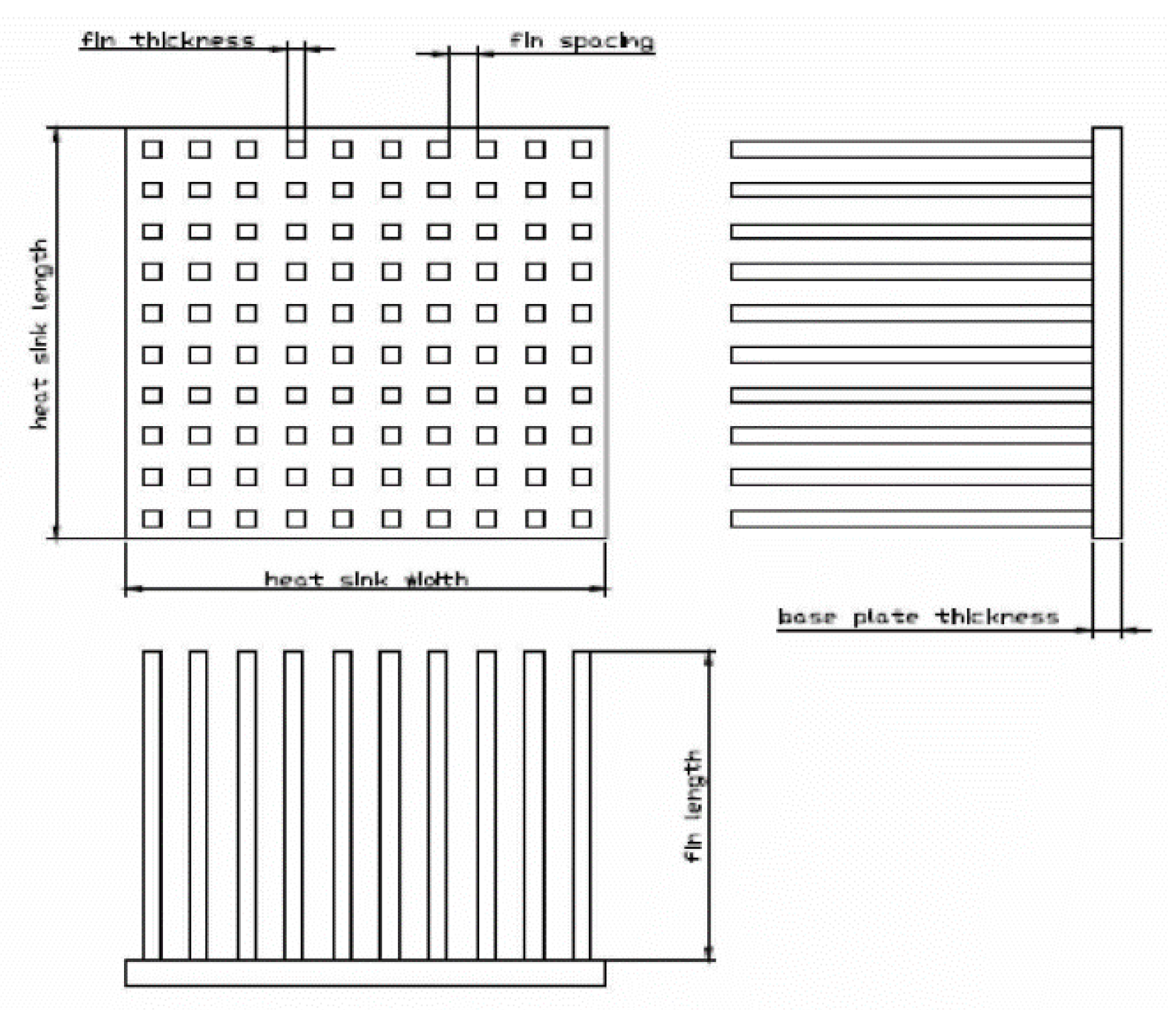

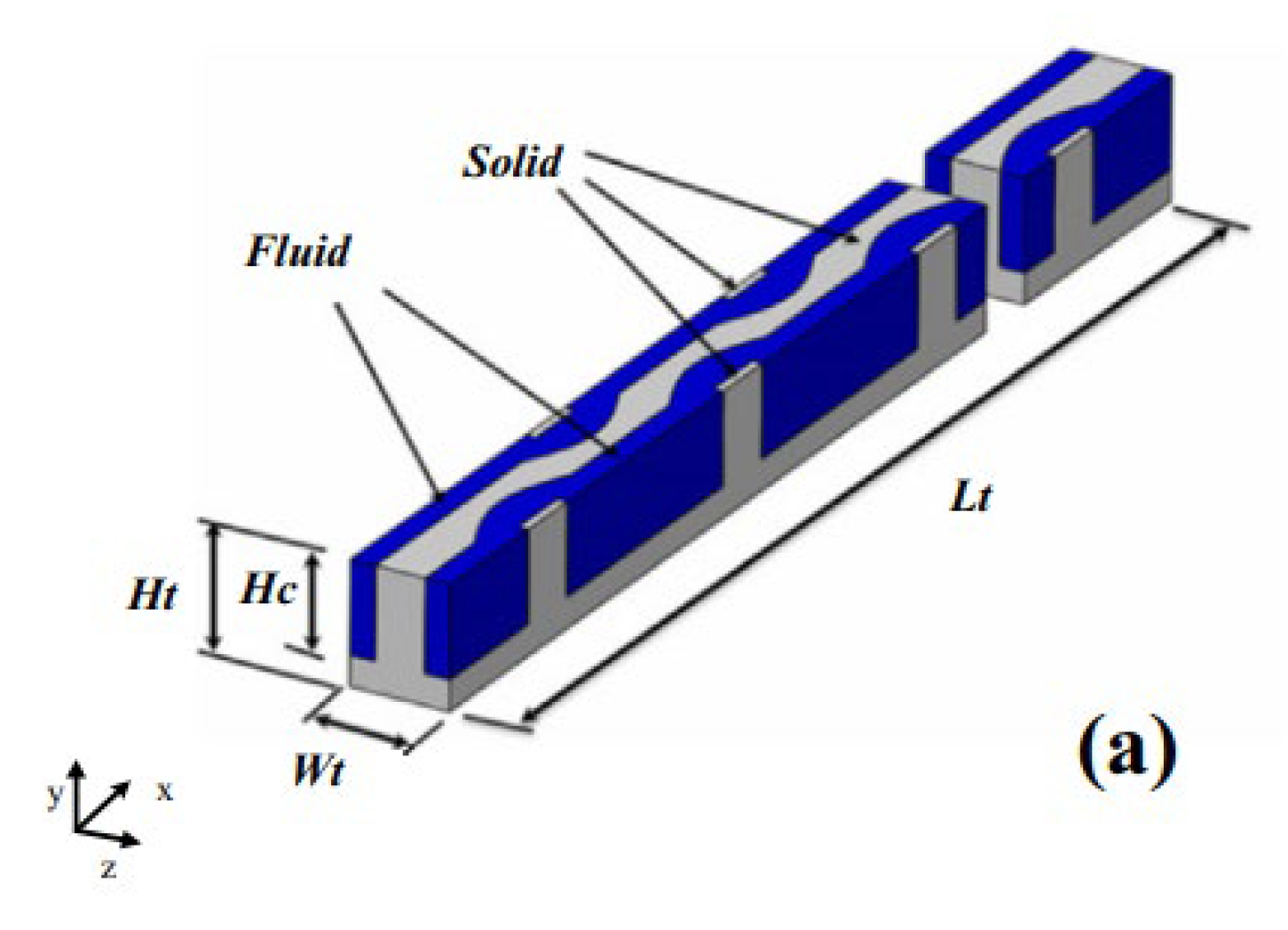

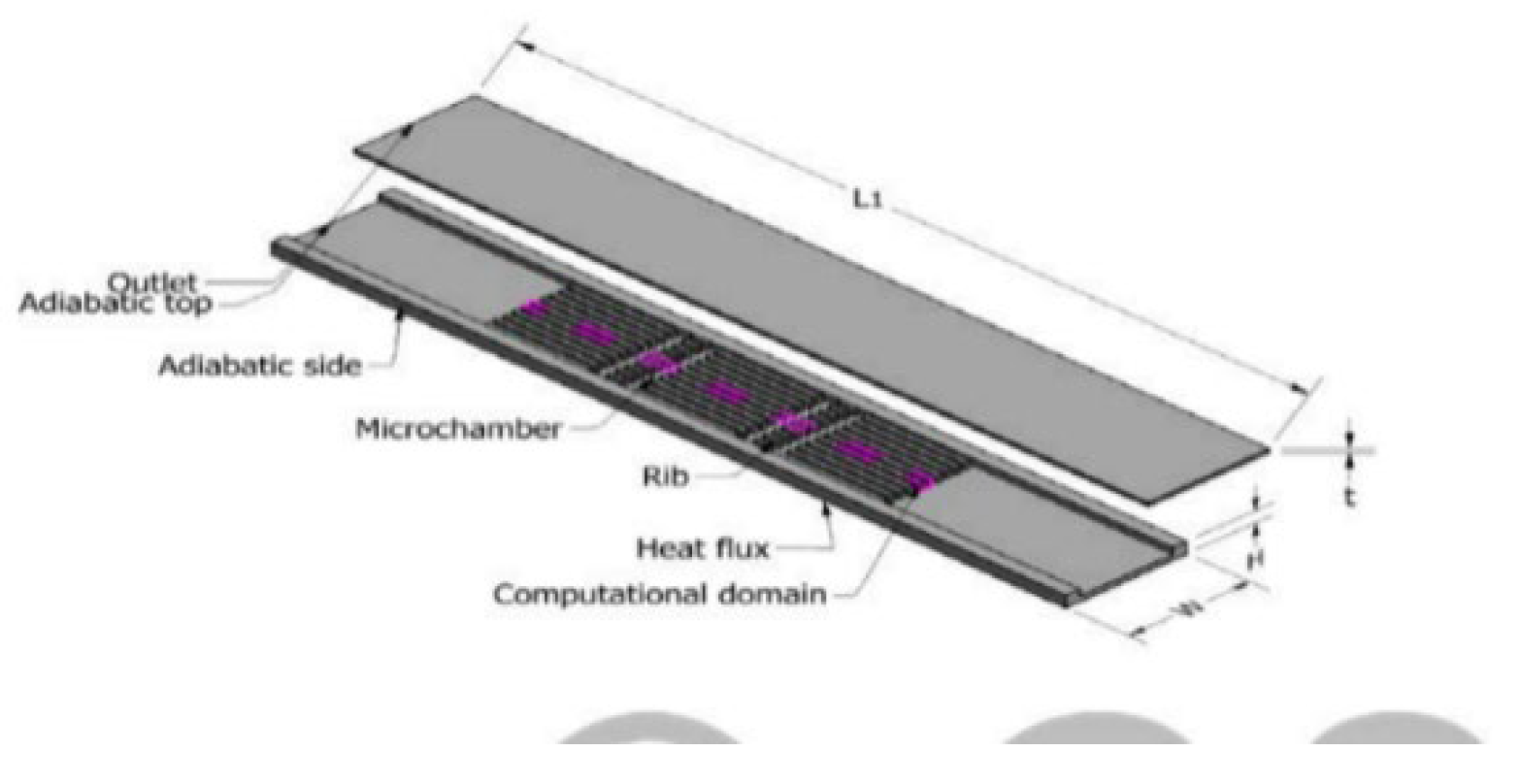

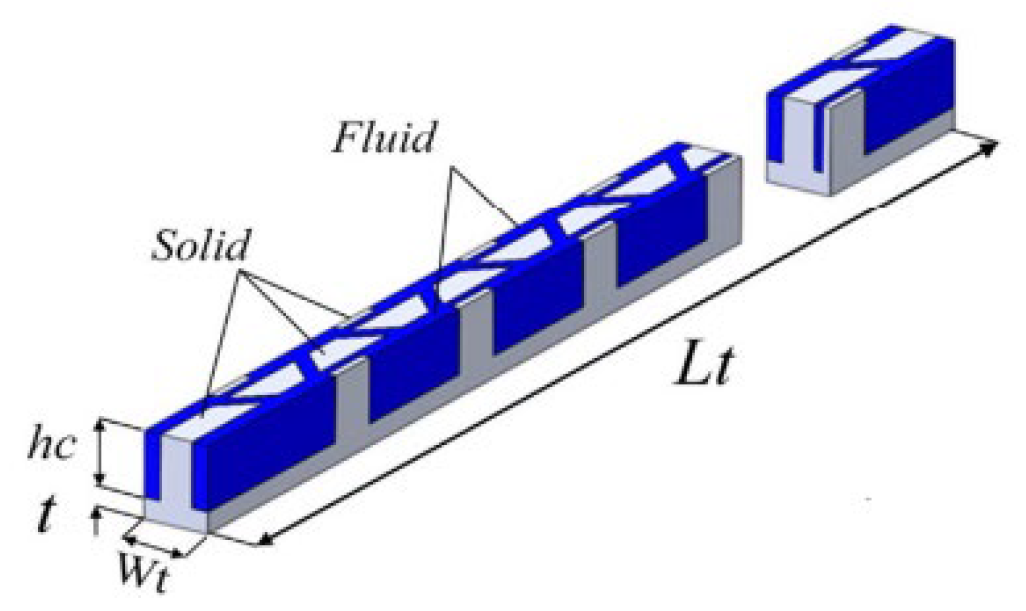

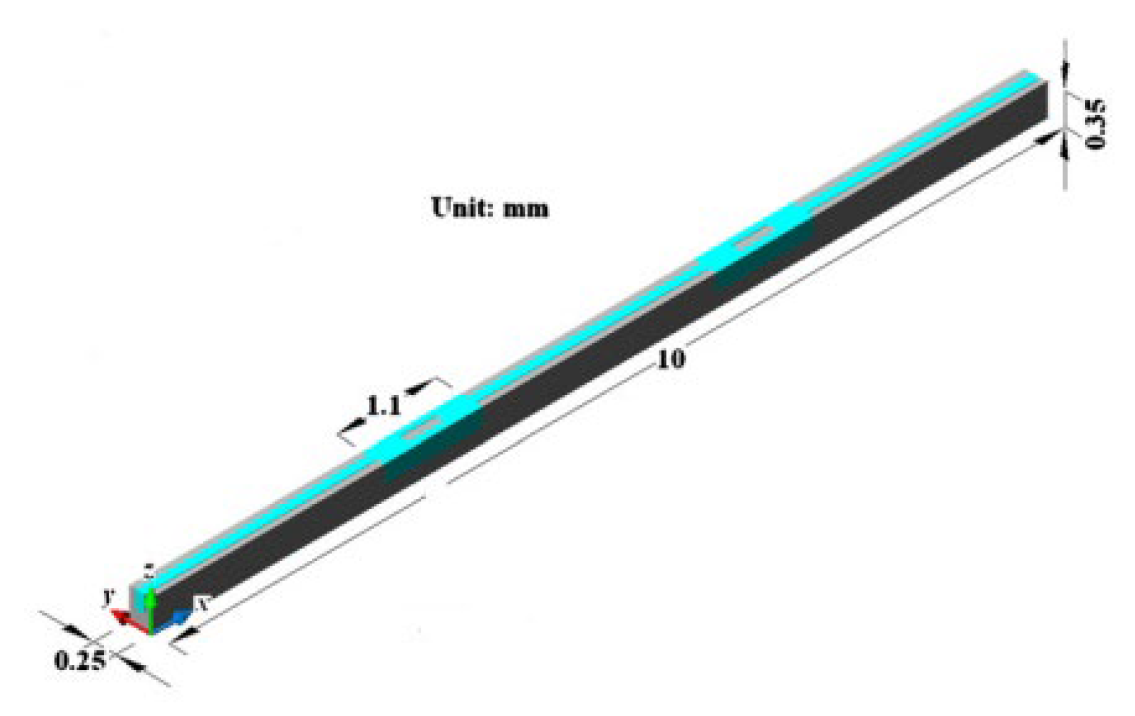

2.2.5. Micro-Fins

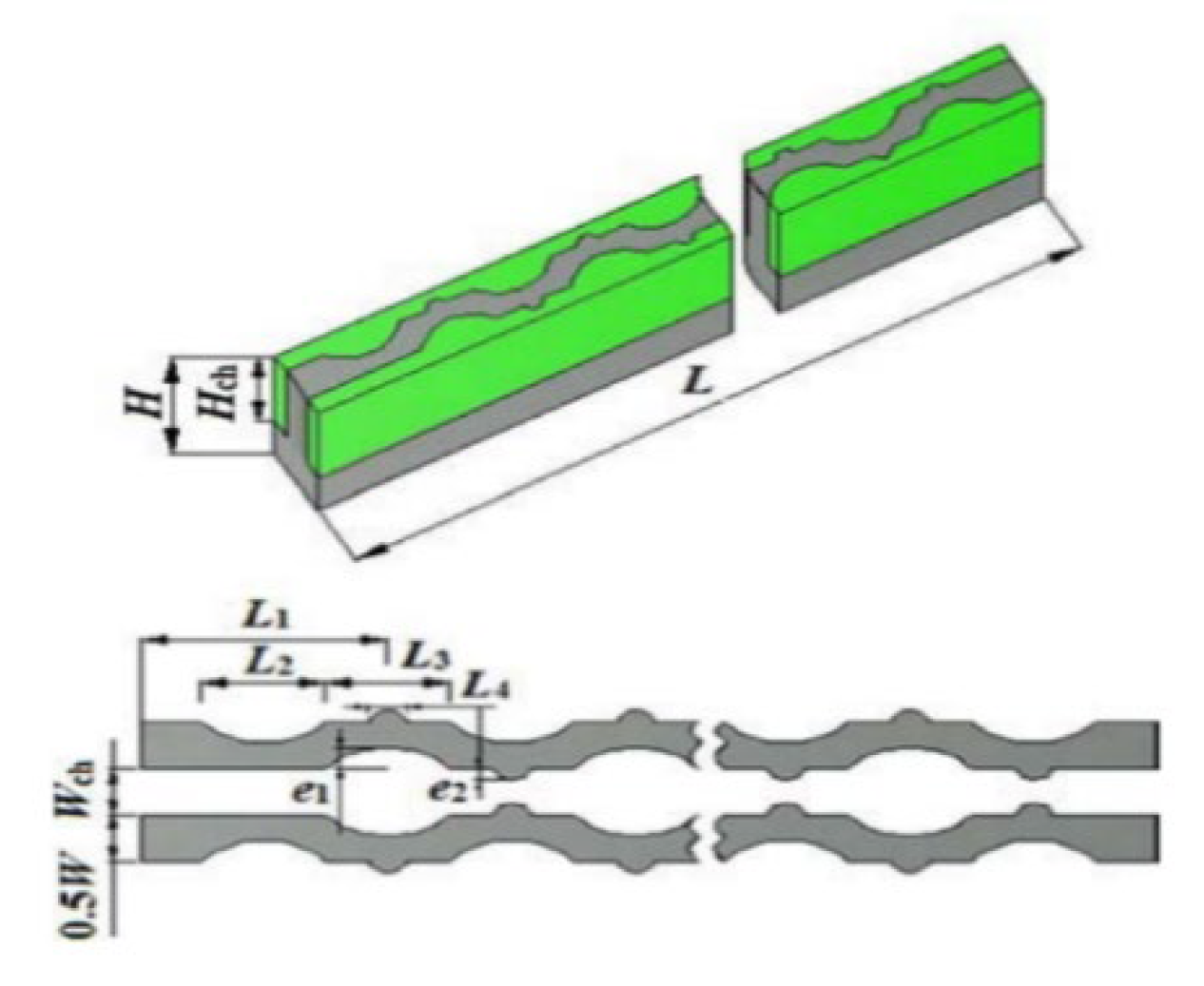

2.2.6. Channel Curvatures

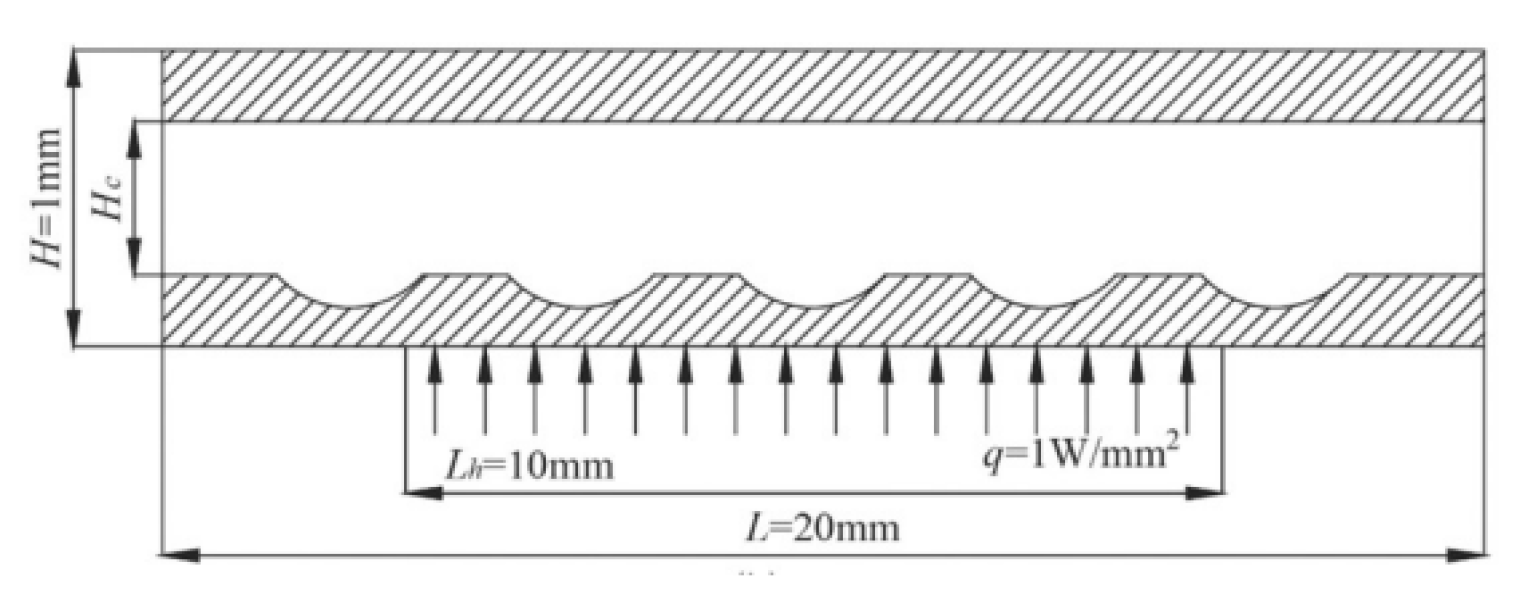

2.2.7. Thermal Enhancement Techniques and Analysis for Smooth Microchannel Heat Sinks

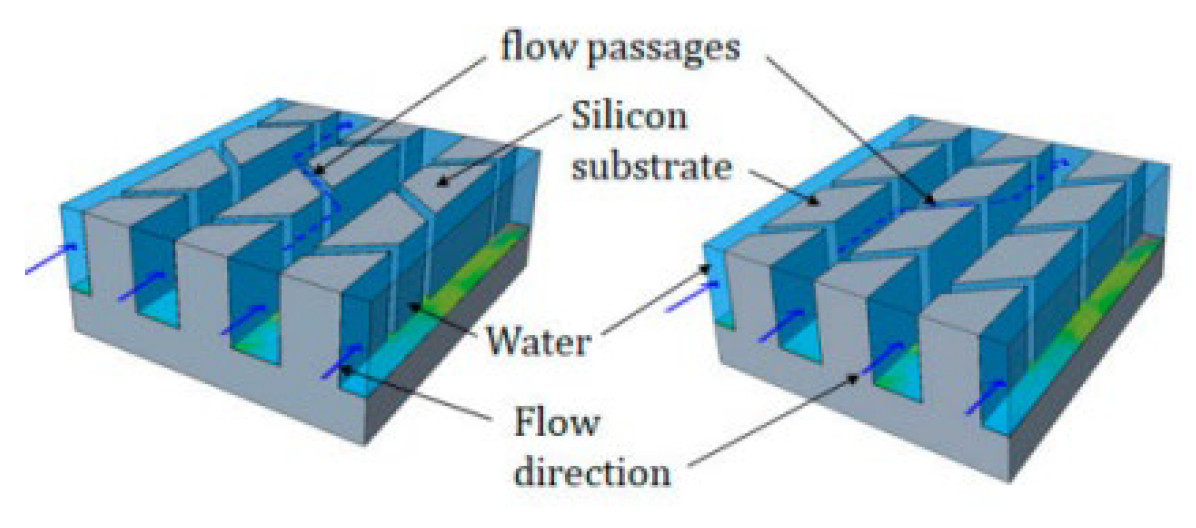

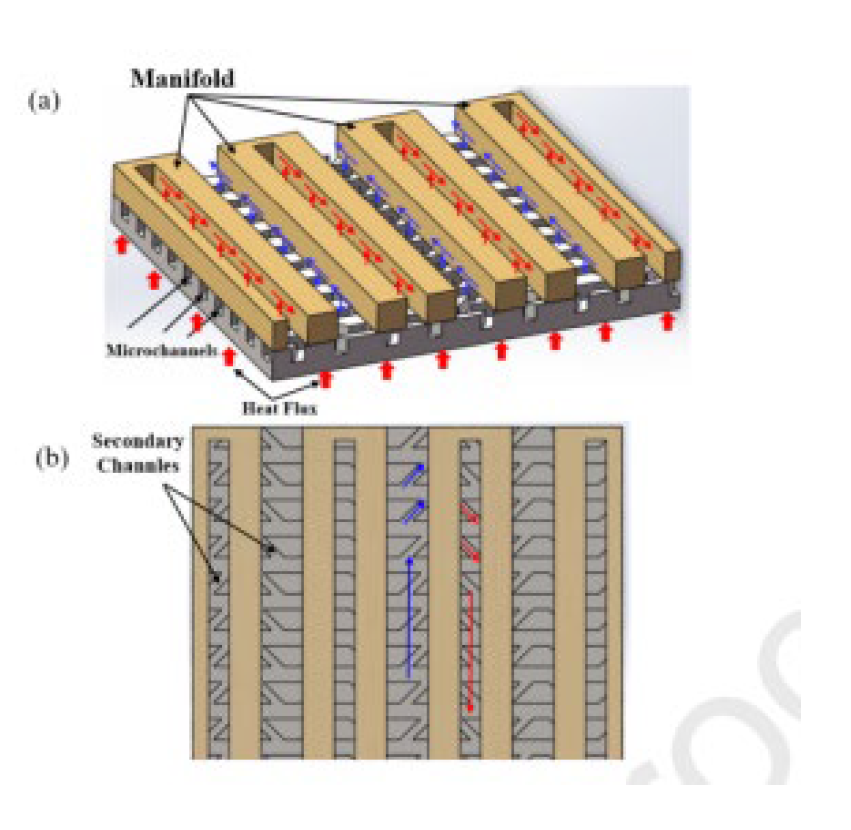

2.2.8. Induced Secondary Flow

2.2.9. Nano Fluids

3. Conclusions

- The outcomes of this review paper suggest that flow disruption techniques, optimization, secondary flows, and the use of nanofluids are all promising approaches for optimizing the thermal performance of MCHS.

- Flow disruption techniques such as ribs, grooves, cavities, dimples, and fins play an important role in enhancing the thermal performance of MCHS by disturbing the flow of the coolant and promoting better heat transfer between the coolant and the heat sink surface.

- Optimization is a crucial step in adjusting various design parameters of heat sink to obtain optimal performance, while using secondary flow promotes better mixing of fluid and enhances convective heat transfer.

- The use of nanofluids combined with flow disruption methods is also promising for enhancing MCHS thermal performance by boosting the convective heat transfer coefficient and promoting improved coolant mixing.

4. Future Recommendations

- The optimization of different design MCHSs should be carried out to obtain their ideal geometries and enhance heat transfer efficiency. Future research should look at the use of multi-objective optimization approaches to balance various design features for microchannel heat sinks. We can achieve optimal solutions that go beyond conventional single-objective optimization techniques by taking into account several performance indicators at once, including pressure drop, heat transfer coefficient, and uniformity of temperature distributions.

- Future research should explore the concept or introduction of secondary flows in various designs of microchannel heat sinks, such as asymmetric, tapered, or curved channels. Researchers can find the best designs that best use secondary flows and enhance overall performance by carefully investigating the effects of various geometries on heat transfer characteristics.

- Investigate the manufacturing of, MCHS with unconventional fin geometry using advanced manufacturing techniques like 3D printing, and selective laser sintering. Complex and complicated fin structures that were previously challenging or impossible to construct using conventional techniques can now be made because of this technology. Researchers can investigate unconventional fin shapes, such as elliptical, triangular, and conical structures or customised arrangements, by using advanced manufacturing to improve heat transfer efficiency.

- Future studies should focus on developing nanoparticles with tailored properties specifically for microchannel heat sink applications. Explore more use of nanomaterials besides traditional metallic or oxides nanoparticles. Go through the possibility of adding carbon-based nanomaterials to nanofluids, such as carbon nanotubes or graphene. Evaluate their effect on thermal stability, heat transfer performance, and compatibility with microchannel heat sink materials.

- Study the advantages of including more than one layer in the microchannel structure. Investigate patterns with various channel widths, heights, or shapes across multiple layers. This can improve heat transfer uniformity, flow mixing, and efficient fluid distribution. Explore the effects of multiple-layer arrangements on pressure drop and overall thermal performance.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Furber, S. (2017). Microprocessors: the engines of the digital age. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Science, 473(2199), 20160893. [CrossRef]

- Krazit, T. Intel unveils its first 10-nanometer Ice Lake processors. The Seattle Times. [cited 2019, August 1]. Intel Ice Lake Processors: Specs, Details, Release Date | WIRED.

- Hanafi, M. Z. M., Ismail, F. S., & Rosli, R. (2015). Radial plate fins heat sink model design and optimization. 2015 10th Asian Control Conference (ASCC). [CrossRef]

- Black, J. R. (1969). Electromigration—A brief survey and some recent results. IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices, 16(4), 338–347. [CrossRef]

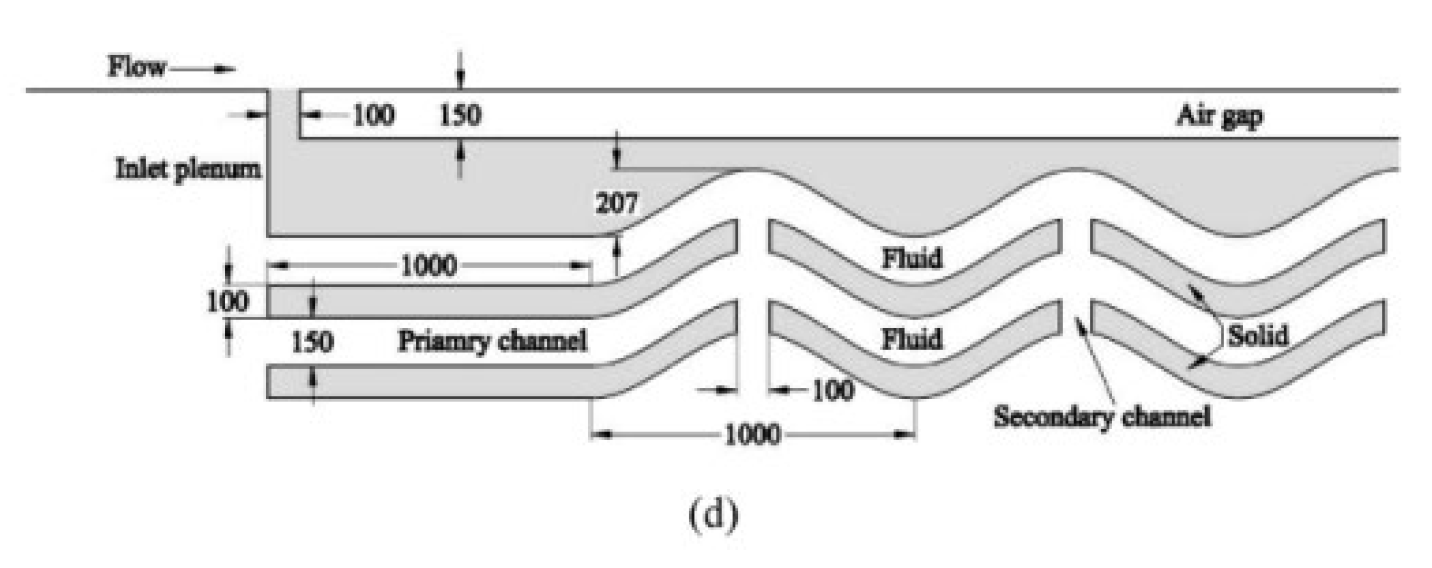

- Deng, D., Xie, Y., Huang, Q., & Wan, W. (2017). On the flow boiling enhancement in interconnected reentrant microchannels. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 108, 453–467.

- Ghani, I. A., Sidik, N. A. C., & Kamaruzaman, N. (2017). Hydrothermal performance of microchannel heat sink: The effect of channel design. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 107, 21–44.

- Vinoth, R., & Senthil Kumar, D. (2017). Channel cross section effect on heat transfer performance of oblique finned microchannel heat sink. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, 87, 270–276.

- Wan Mohd. Arif Aziz Japar , Nor Azwadi Che Sidik , Rahman Saidur , Yutaka Asako and Siti Nurul Akmal Yusof A review of passive methods in microchannel heat sink application through advanced geometric structure and nanofluids: Current advancements and challenges. 2020. 9(1): p. 1192-1216. [CrossRef]

- Khattak, Z., & Ali, H. M. (2019). Air cooled heat sink geometries subjected to forced flow: A critical review. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 130, 141–161.

- Adham, A., N. Mohd-Ghazali, and R. Ahmad, Thermal and hydrodynamic analysis of microchannel heat sinks: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2013. 21: p. 614-622. [CrossRef]

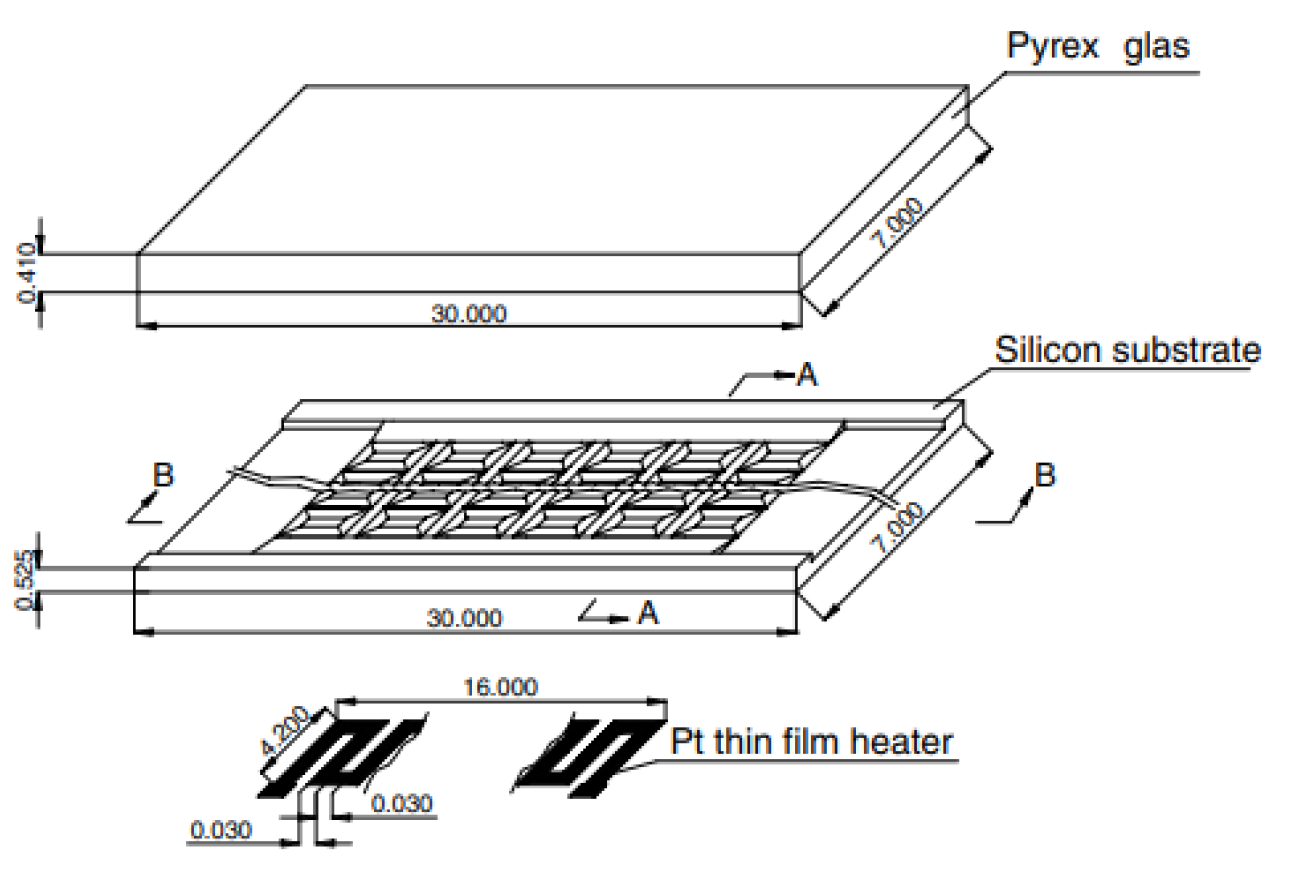

- Tuckerman, D. B., & Pease, R. F. W. (1981). High-performance heat sinking for VLSI. IEEE Electron Device Letters, 2(5), 126–129. [CrossRef]

- Shizhong Zhang, Faraz Ahmad, Amjid Khan, Nisar Ali & Mohamed Badran et al. Performance improvement and thermodynamic assessment of microchannel heat sink with different types of ribs and cones, Scientific Reports volume 12, Article number: 10802 (2022).

- Nemati, H., A General Equation Based on Entropy Generation Minimization to Optimize Plate Fin Heat Sink. Engineering Journal, 2018. 22: p. 159-174. [CrossRef]

- Koşar, A,, Effect of substrate thickness and material on heat transfer in microchannel heat sinks. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, 2010. 49(4): p. 635-642.

- Woodcraft, A.L., Recommended values for the thermal conductivity of aluminium of different purities in the cryogenic to room temperature range, and a comparison with copper. Cryogenics, 2005. 45(9): p. 626-636.

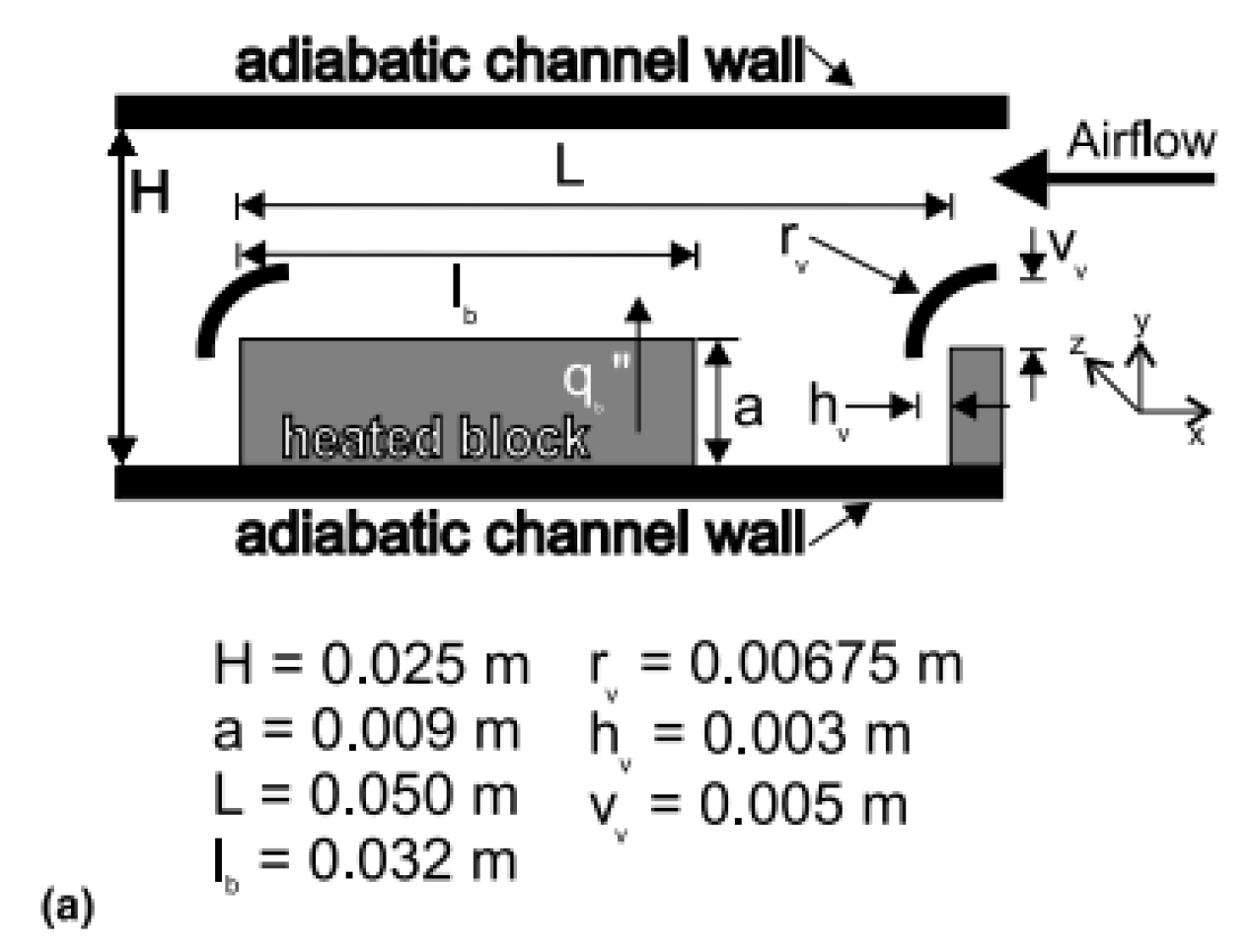

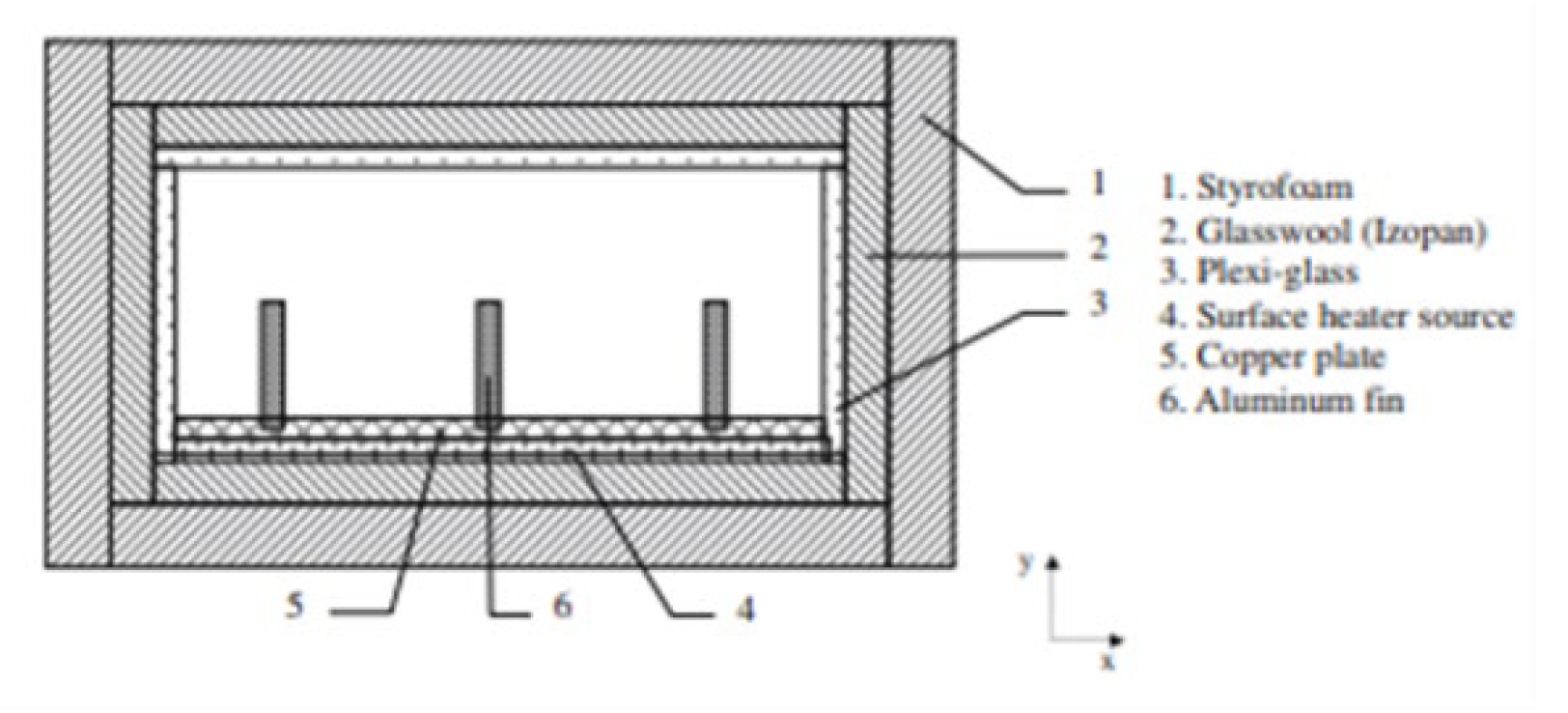

- Dogan, M., & Sivrioglu, M., Experimental investigation of mixed convection heat transfer from longitudinal fins in a horizontal rectangular channel. 2010. 53(9-10): p. 2149-2158.

- Khan, M. N., & Karimi, M. N.: Journal of Process Mechanical Engineering, Analysis of heat transfer enhancement in microchannel by varying the height of pin fins at upstream and downstream region. 2021. 235(4): p. 758-767. [CrossRef]

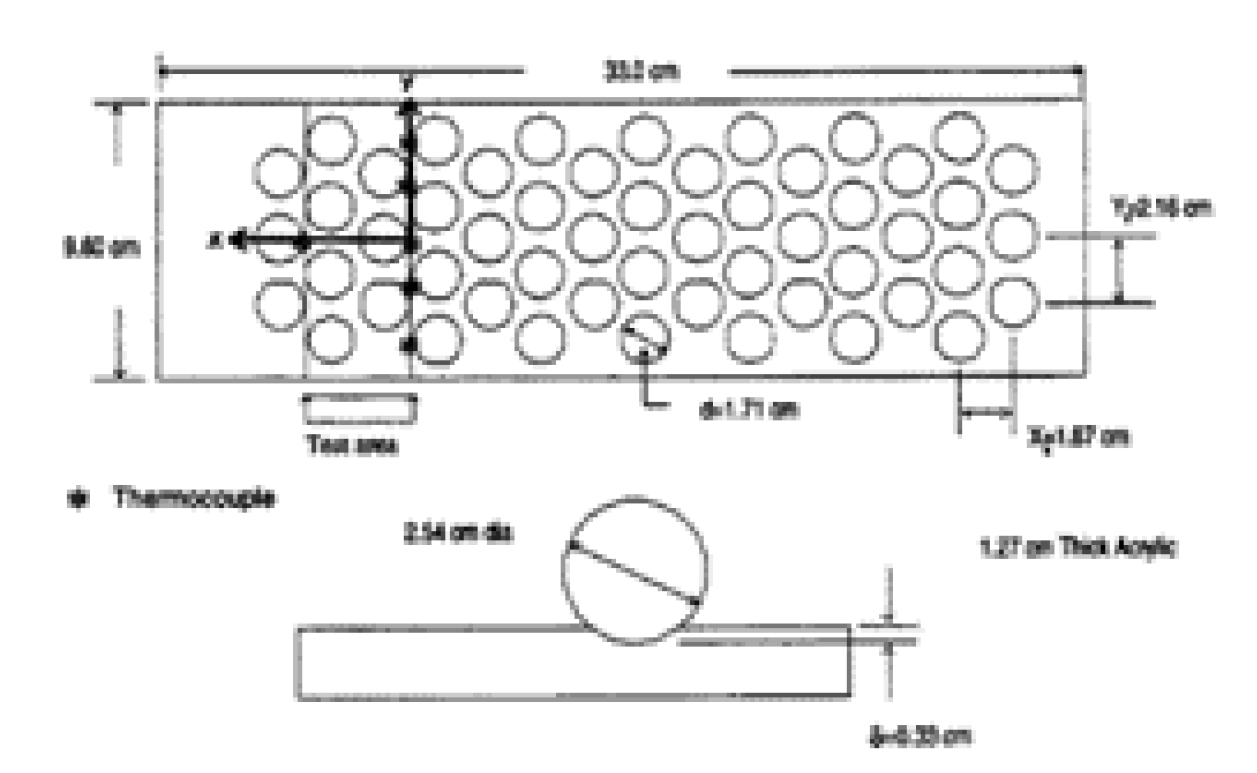

- Yang, D., Wang, Y., Ding, G., Jin, Z., Zhao, J., & Wang, G. et al., Numerical and experimental analysis of cooling performance of single-phase array microchannel heat sinks with different pin-fin configurations. Applied Thermal Engineering, 2017. 112: p. 1547-1556.

- Chen, C.-H. (2007). Forced convection heat transfer in microchannel heat sinks. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 50(11-12), 2182–2189.

- Qu, W., & Mudawar, I., Experimental and numerical study of pressure drop and heat transfer in a single-phase micro-channel heat sink. 2002. 45(12): p. 2549-2565. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y. L., Xia, G. D., Liu, X. F., & Li, Y. F. (2014). Heat transfer in the microchannels with fan-shaped reentrant cavities and different ribs based on field synergy principle and entropy generation analysis. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 68, 224–233.

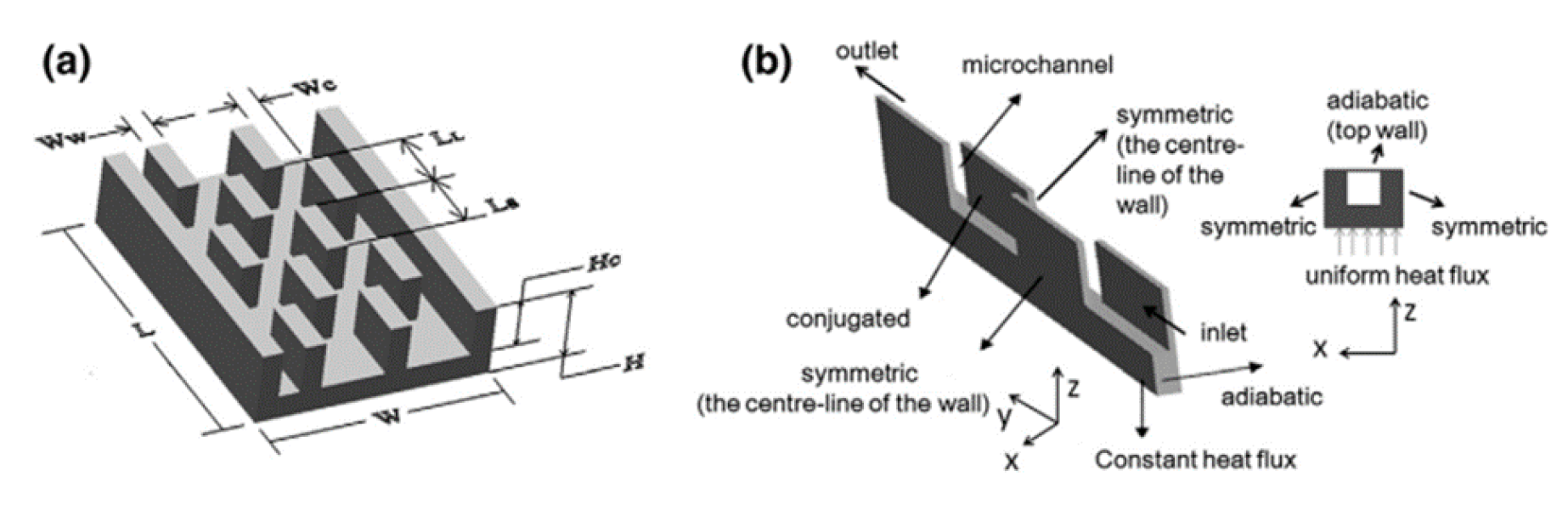

- Li, Y., Zhang, F., Sunden, B., & Xie, G. (2014). Laminar thermal performance of microchannel heat sinks with constructal vertical Y-shaped bifurcation plates. Applied Thermal Engineering, 73(1), 185–195.

- Go, J.S., Design of a microfin array heat sink using flow-induced vibration to enhance the heat transfer in the laminar flow regime. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 2003. 105(2): p. 201-210. [CrossRef]

- Hessami, M.-A., A. Berryman, and P. Bandopdhayay, Heat Transfer Enhancement in an Electrically Heated Horizontal Pipe Due to Flow Pulsation. Vol. 374. 2003. ISBN: 0-7918-3718-1.

- T. Krishnaveni, T. Renganathan, J. R. Picardo, and S. Pushpavanam et al., Numerical study of enhanced mixing in pressure-driven flows in microchannels using a spatially periodic electric field. Physical Review E, 2017. 96(3): p. 033117. [CrossRef]

- Morini, G. L., Lorenzini, M., Salvigni, S., & Spiga, M. (2006). Thermal performance of silicon micro heat-sinks with electrokinetically-drivenflows. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, 45(10), 955–961. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y., Lee, Y. J., & Zhang, X. (2013). Trapezoidal Microchannel Heat Sink With Pressure-Driven and Electro-Osmotic Flows for Microelectronic Cooling. IEEE Transactions on Components, Packaging and Manufacturing Technology, 3(11), 1851–1858. [CrossRef]

- Narrein, K., Sivasankaran, S., & Ganesan, P. (2016). Numerical investigation of two-phase laminar pulsating nanofluid flow in a helical microchannel. Numerical Heat Transfer, Part A: Applications, 69(8), 921–930. [CrossRef]

- Nandi, T. K., & Chattopadhyay, H. (2013). Numerical investigations of simultaneously developing flow in wavy microchannels under pulsating inlet flow condition. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, 47, 27–31.

- Wang, G., Niu, D., Xie, F., Wang, Y., Zhao, X., & Ding, G. et al., Experimental and numerical investigation of a microchannel heat sink (MCHS) with micro-scale ribs and grooves for chip cooling. 2015. 85: p. 61-70.

- Xia, G. D., Jia, Y. T., Li, Y. F., Ma, D. D., & Cai, B., et al., Numerical simulation and multiobjective optimization of a microchannel heat sink with arc-shaped grooves and ribs. Numerical Heat Transfer, Part A: Applications, 2016: p. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F., T.A. Cheema, and M.M.U. Rehman, Flow and heat transfer characteristics of microchannel heat sink with cylindrical ribs and cavities. Ahmad, F., T.A. Cheema, and M.M.U. Rehman, Fflow... - Google Scholar.

- Shahzad Ali, Faraz Ahmad, Muhammad Hassan, Zabdur Rehman, Abdul Wadood,Khurshid Ahmad and Herie Park, et al., Thermo-fluid characteristics of microchannel heat sink with multi-configuration NACA 2412 hydrofoil ribs. 2021. 9: p. 128407-128416.

- Khan, A. A., Kim, S.-M., & Kim, K.-Y. (2016). Performance Analysis of a Microchannel Heat Sink with Various Rib Configurations. Journal of Thermophysics and Heat Transfer, 30(4), 782–790. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-H., Lo, Y.-H., Li, X.-X., & Huh, M. (2016). Heat Transfer and Friction in a Square Channel with Ribs and Grooves. Journal of Thermophysics and Heat Transfer, 30(1), 144–151. [CrossRef]

- LAU, S. C., KUKREJA, R. T., & MCMILLIN, R. D. (1992). Turbulent heat transfer in a square channel with staggered discrete ribs. Journal of Thermophysics and Heat Transfer, 6(1), 171–173.

- Zhang, S,Faraz Ahmad; Haseeb Ali; Sadiq Ali; Kareem Akhtar and Nisar Ali et al., Computational Study of Hydrothermal Performance of Microchannel Heat Sink With Trefoil Shape Ribs. 2022. 10: p. 74412-74424.

- Wang, G., Qian, N., & Ding, G. (2019). Heat transfer enhancement in microchannel heat sink with bidirectional rib. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 136, 597–609.

- Ali, S,Faraz Ahmed, Kareem Akhtar, Numan, Habib,Muhammad, Aamirkhaled Giasin, Ana Vafadar and Danil Yurievich Pimenov et al., Numerical investigation of microchannel heat sink with trefoil shape ribs. 2021. 14(20): p. 6764.

- Rehman, M. M. U., Cheema, T. A., Ahmad, F., Khan, M., & Abbas, A. (2019). Thermodynamic Assessment of Microchannel Heat Sinks with Novel Sidewall Ribs. Journal of Thermophysics and Heat Transfer, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Ghani, I. A., Kamaruzaman, N., & Sidik, N. A. C. (2017). Heat transfer augmentation in a microchannel heat sink with sinusoidal cavities and rectangular ribs. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 108, 1969–1981.

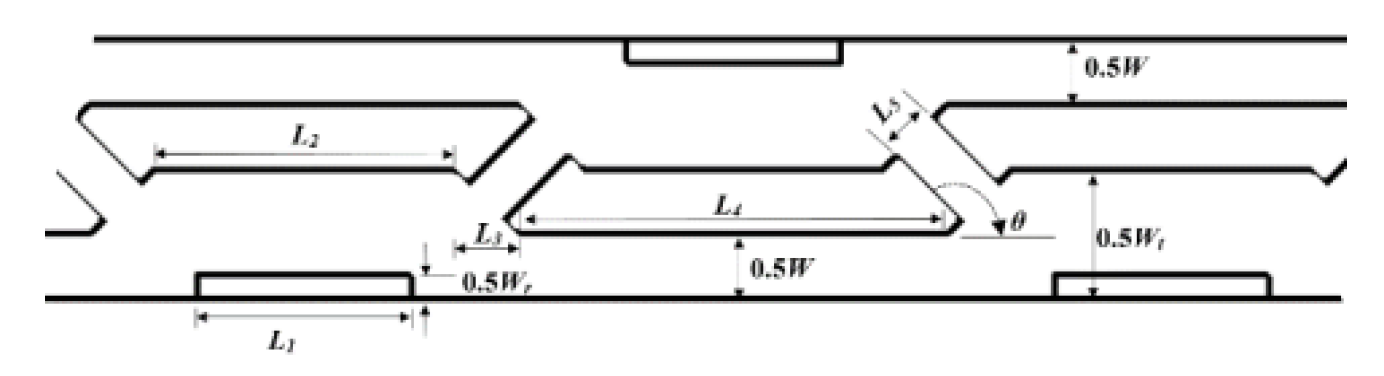

- Chai, L., Xia, G., Zhou, M., Li, J., & Qi, J. (2013). Optimum thermal design of interrupted microchannel heat sink with rectangular ribs in the transverse microchambers. Applied Thermal Engineering, 51(1-2), 880–889.

- Li, Y. F., Xia, G. D., Ma, D. D., Jia, Y. T., & Wang, J. (2016). Characteristics of laminar flow and heat transfer in microchannel heat sink with triangular cavities and rectangular ribs. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 98, 17–28.

- Binuyo, A.S. Numerical Investigation Of Two-Phase Laminar Pulsating Nanofluid Flow In AnInterruptedMicrochannel Heat Sink. 2020. View article (google.com).

- Korichi, A., & Oufer, L. (2007). Heat transfer enhancement in oscillatory flow in channel with periodically upper and lower walls mounted obstacles. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow, 28(5), 1003–1012.

- Datta, A., Sharma, V., Sanyal, D., & Das, P. (2019). A conjugate heat transfer analysis of performance for rectangular microchannel with trapezoidal cavities and ribs. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, 138, 425–446.

- Ahmad, F., et al., Thermodynamic Analysis of Microchannel Heat Sink With Cylindrical Ribs and Cavities. Journal of Heat Transfer, 2020. 142(9). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q., Chang, K., Chen, J., Zhang, X., Xia, H., Zhang, H., … Jin, Y. (2020). Characteristics of heat transfer and fluid flow in microchannel heat sinks with rectangular grooves and different shaped ribs. Alexandria Engineering Journal. [CrossRef]

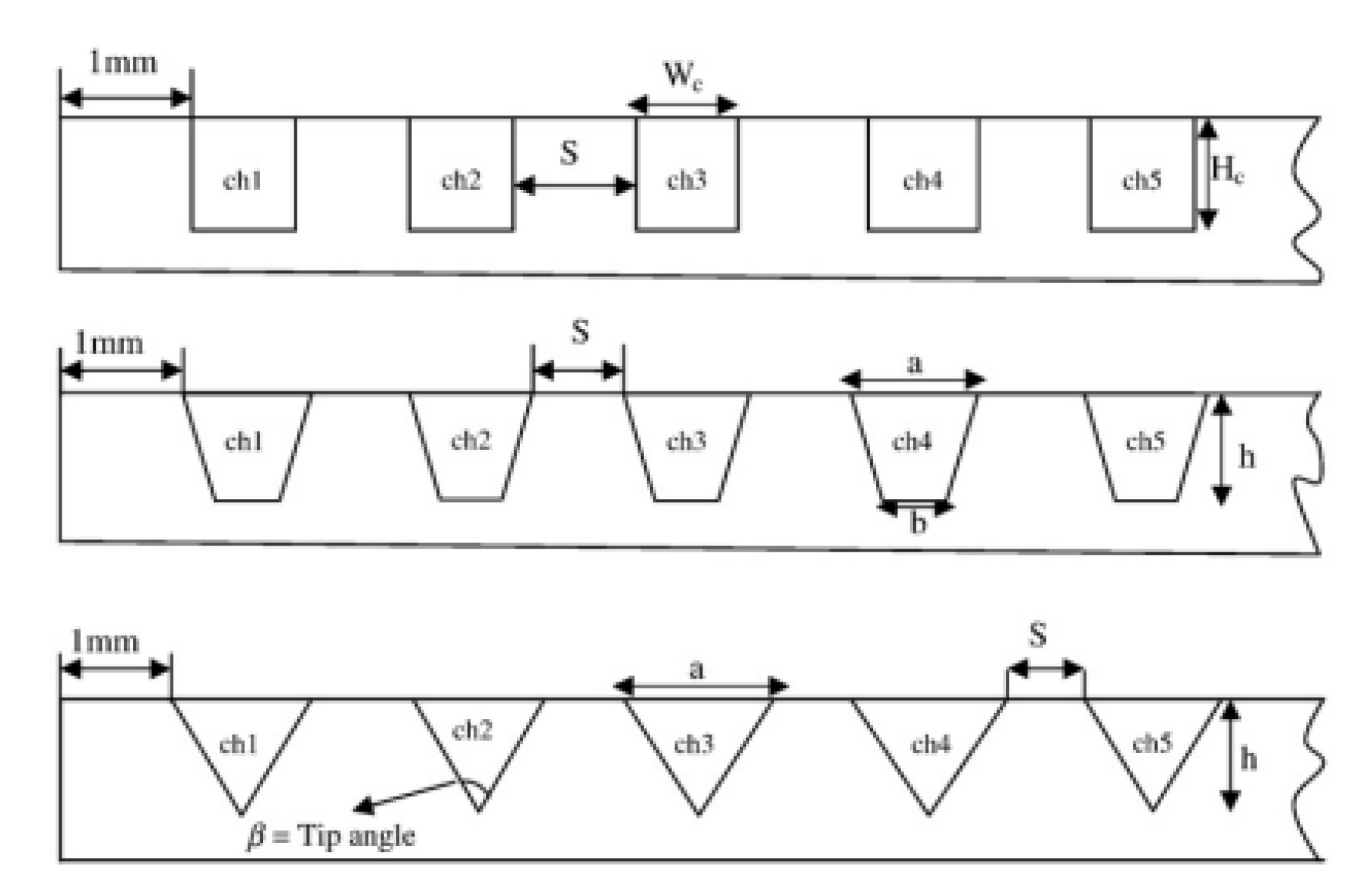

- Ahmed, H. E., & Ahmed, M. I. (2015). Optimum thermal design of triangular, trapezoidal and rectangular grooved microchannel heat sinks. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, 66, 47–57.

- Kumar, P. (2019). Numerical investigation of fluid flow and heat transfer in trapezoidal microchannel with groove structure. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, 136, 33–43. [CrossRef]

- Xia, G., Chai, L., Wang, H., Zhou, M., & Cui, Z. (2011). Optimum thermal design of microchannel heat sink with triangular reentrant cavities. Applied Thermal Engineering, 31(6-7), 1208–1219.

- Herman, C., & Kang, E. (2002). Heat transfer enhancement in a grooved channel with curved vanes. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 45(18), 3741–3757. [CrossRef]

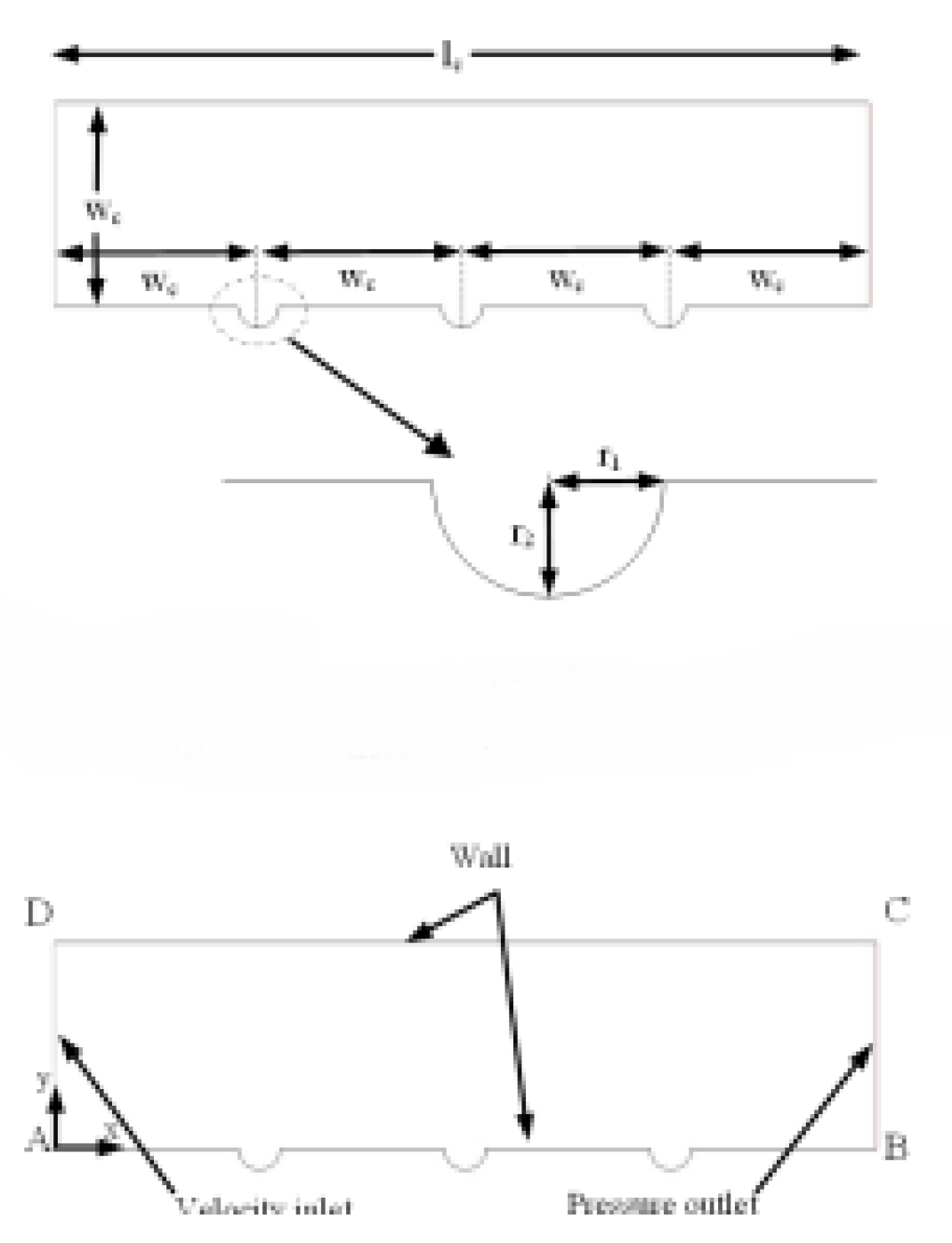

- Rehman, M. M. U., Cheema, T. A., Ahmad, F., Abbas, A., & Malik, M. S. (2019). Numerical investigation of heat transfer enhancement and fluid flow characteristics in a microchannel heat sink with different wall/design configurations of protrusions/dimples. Heat and Mass Transfer. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M., Lu, H., Gong, L., Chai, J. C., & Duan, X. (2016). Parametric numerical study of the flow and heat transfer in microchannel with dimples. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, 76, 348–357.

- Chen, Y., Chew, Y. T., & Khoo, B. C. (2012). Enhancement of heat transfer in turbulent channel flow over dimpled surface. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 55(25-26), 8100–8121.

- Moon, H., T. O’connell, and B. Glezer. Channel height effect on heat transfer and friction in a dimpled passage. in Turbo Expo: Power for Land, Sea, and Air. 1999. American Society of Mechanical Engineers.ezer. [CrossRef]

- Gururatana, S.J.A.J.o.A.S., Numerical simulation of micro-channel heat sink with dimpled surfaces. 2012. 9(3): p. 399.

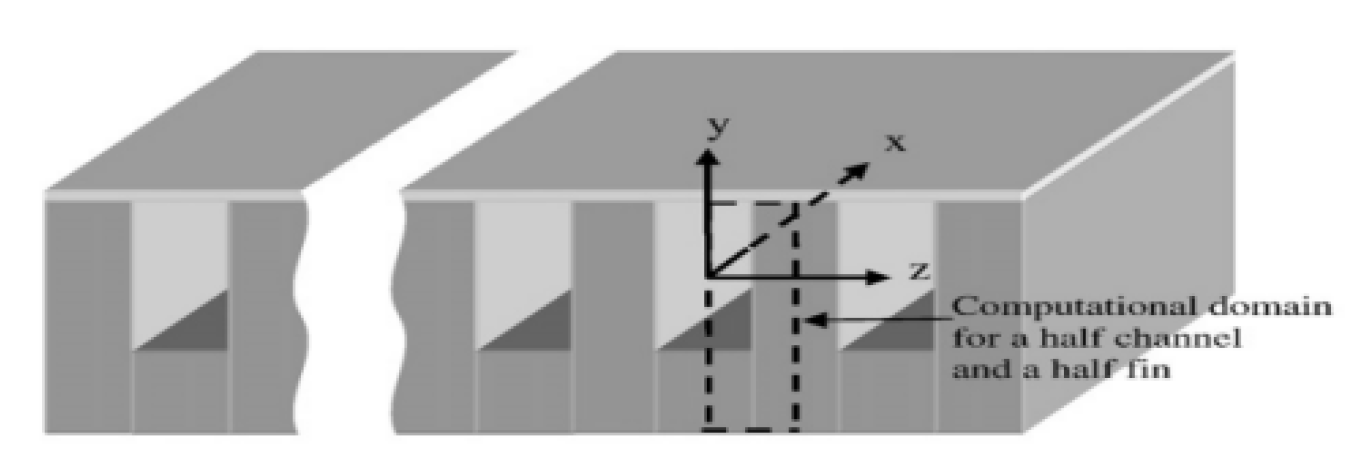

- Hong, F., & Cheng, P., Three dimensional numerical analyses and optimization of offsetstrip-fin microchannel heat sinks. 2009. 36(7): p. 651-656.

- Li, P., Luo, Y., Zhang, D., & Xie, Y. (2018). Flow and heat transfer characteristics and optimization study on the water-cooled microchannel heat sinks with dimple and pin-fin. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 119, 152–162.

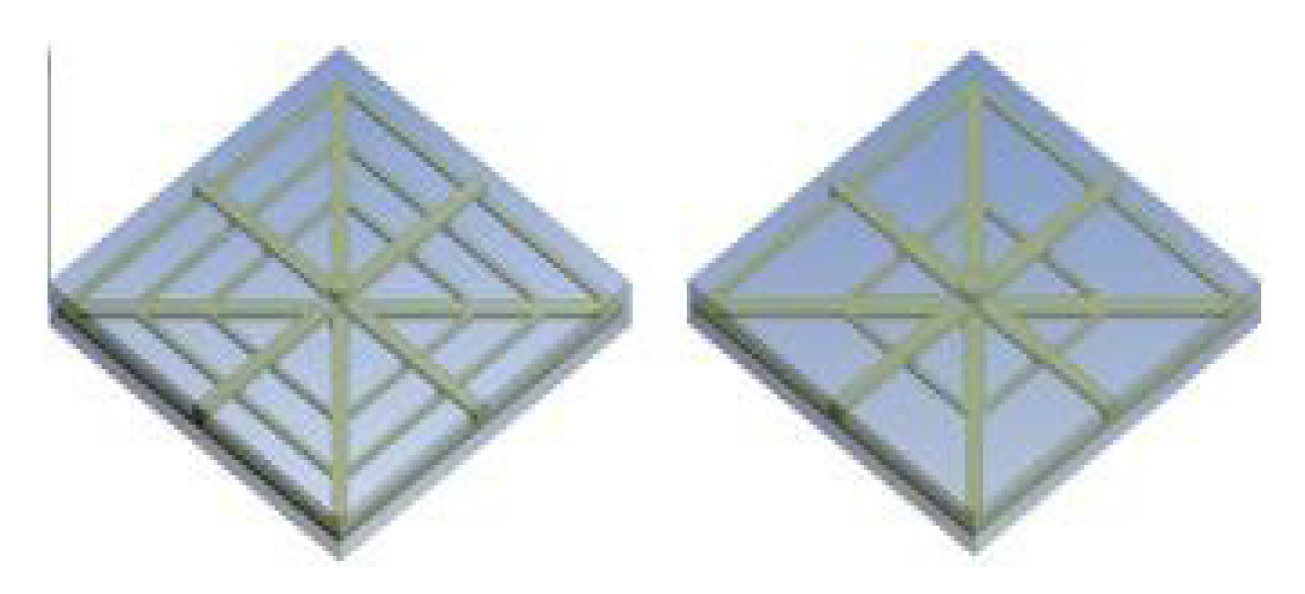

- Wazir, M.A., et al., Thermal enhancement of microchannel heat sink using pin-fin configurations and geometric optimization. Engineering Research Express, 2024. DOI.

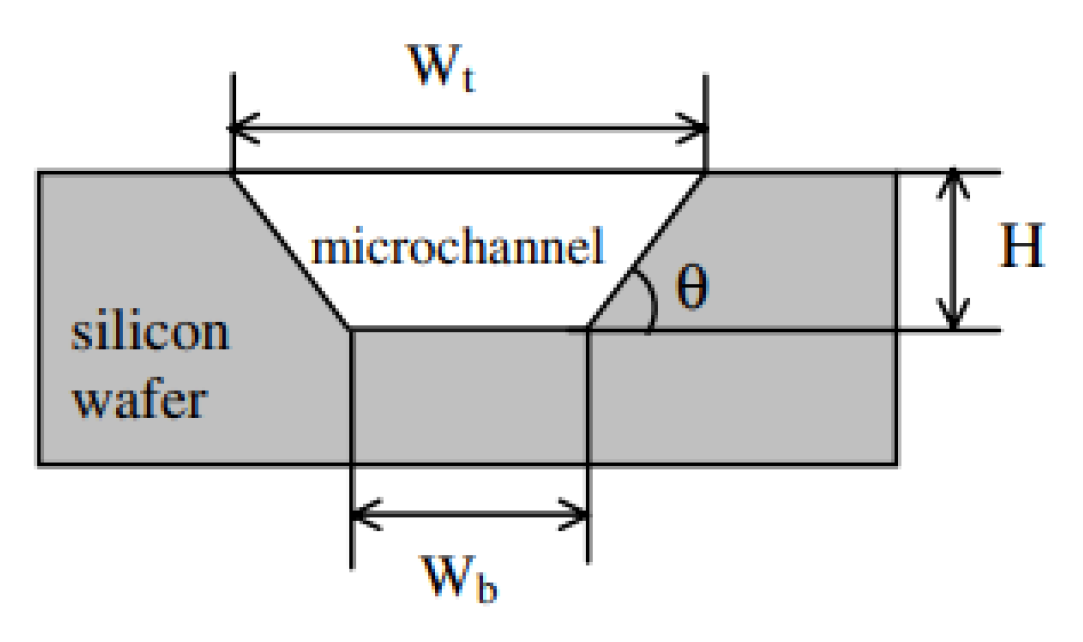

- Chu, J.-C., et al., Heat transfer for water flow in triangular silicon microchannels. 2008. 3(3): p. 410-420. [CrossRef]

- Deng, D., Wan, W., Tang, Y., Shao, H., & Huang, Y. (2015). Experimental and numerical study of thermal enhancement in reentrant copper microchannels. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 91, 656–670.

- Wu, H. ., & Cheng, P. (2003). An experimental study of convective heat transfer in silicon microchannels with different surface conditions. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 46(14), 2547–2556. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, H., et al., Numerical simulation of heat transfer enhancement in wavy microchannel heat sink. 2011. 38(1): p. 63-68.

- Gunnasegaran, P., et al., The effect of geometrical parameters on heat transfer characteristics of microchannels heat sink with different shapes. 2010. 37(8): p. 1078-1086.

- Ghaedamini, H., P.S. Lee, and C.J. Teo, Developing forced convection in converging–diverging microchannels. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 2013. 65: p. 491-499.

- Peng, X.F., G.P. Peterson, and B.X. Wang, Heat transfer characteristics of water flowing through microchannels. Experimental Heat Transfer, 1994. 7(4): p. 265-283. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-Q., A.S. Mujumdar, and C.J.I.J.o.T.S. Yap, Thermal characteristics of tree-shaped microchannel nets for cooling of a rectangular heat sink. 2006. 45(11): p. 1103-1112. [CrossRef]

- McHale, J. P., & Garimella, S. V. (2010). Heat transfer in trapezoidal microchannels of various aspect ratios. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 53(1-3), 365–375.

- Harley, J.C., et al., Gas flow in micro-channels. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 1995. 284: p. 257-274.

- Tiselj, I., Hetsroni, G., Mavko, B., Mosyak, A., Pogrebnyak, E., & Segal, Z. (2004). Effect of axial conduction on the heat transfer in micro-channels. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 47(12-13), 2551–2565.

- Harms, T.M., M.J. Kazmierczak, and F.M. Gerner, Developing convective heat transfer in deep rectangular microchannels. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow, 1999. 20(2): p. 149-157. [CrossRef]

- Toh, K.C., X.Y. Chen, and J.C. Chai, Numerical computation of fluid flow and heat transfer in microchannels. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 2002. 45(26): p. 5133-5141. [CrossRef]

- Gamrat, G., et al., Conduction and entrance effects on laminar liquid flow and heat transfer in rectangular microchannels. 2005. 48(14): p. 2943-2954.

- Xu, J. L., Gan, Y. H., Zhang, D. C., & Li, X. H. (2005). Microscale heat transfer enhancement using thermal boundary layer redeveloping concept. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 48(9), 1662–1674.

- Peng, X., G.J.I.J.o.H. Peterson, and M. Transfer, The effect of thermofluid and geometrical parameters on convection of liquids through rectangular microchannels. 1995. 38(4): p. 755-758. [CrossRef]

- Betz, A. R., & Attinger, D. (2010). Can segmented flow enhance heat transfer in microchannel heat sinks? International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 53(19-20), 3683–3691.

- Zade, A.Q., et al., Heat transfer characteristics of developing gaseous slip-flow in rectangular microchannels with variable physical properties. 2011. 32(1): p. 117-127.

- Deng, B., Y. Qiu, and C.N.J.A.t.e. Kim, An improved porous medium model for microchannel heat sinks. 2010. 30(16): p. 2512-2517.76.

- Saenen, T. and M.J.I.j.o.t.s. Baelmans, Numerical model of a two-phase microchannel heat sink electronics cooling system. 2012. 59: p. 214-223.

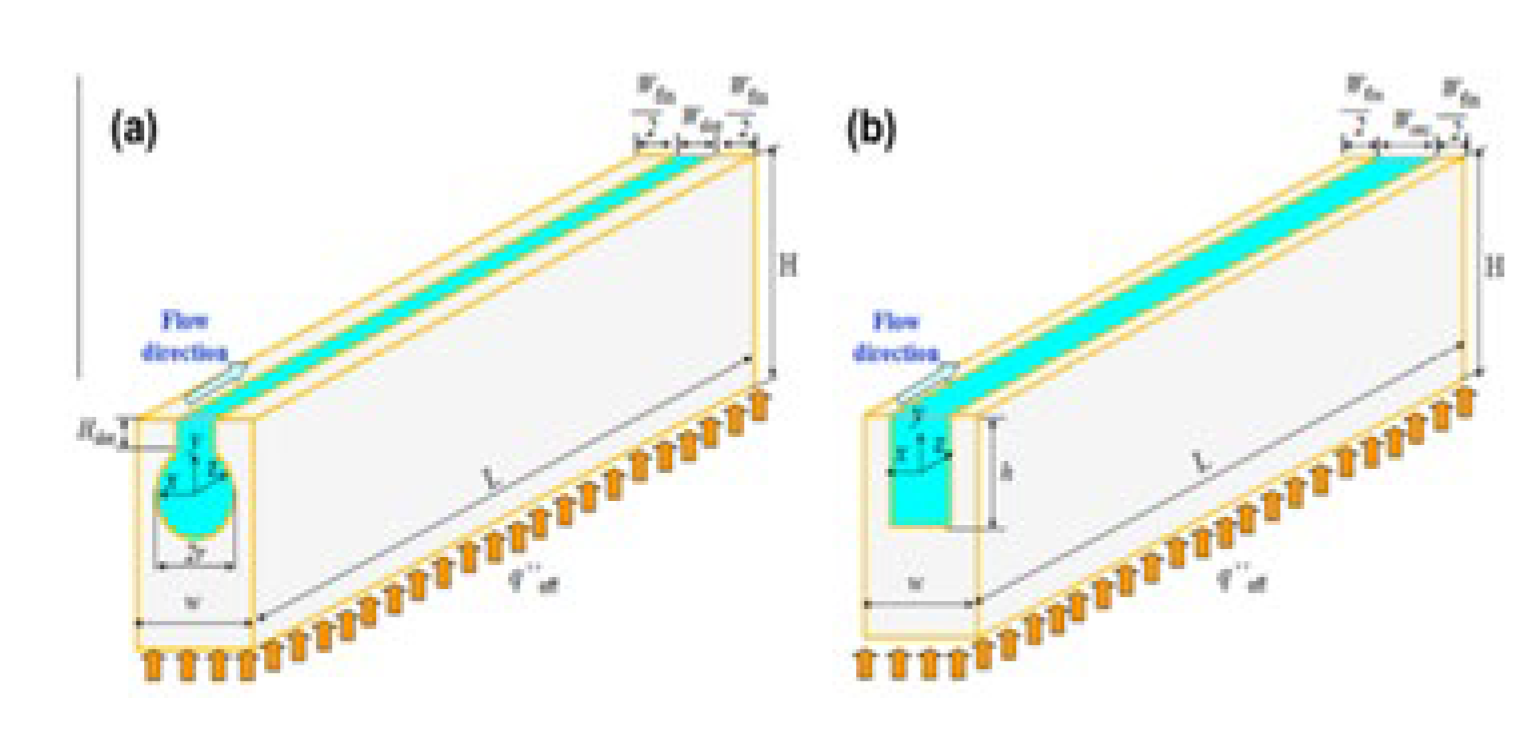

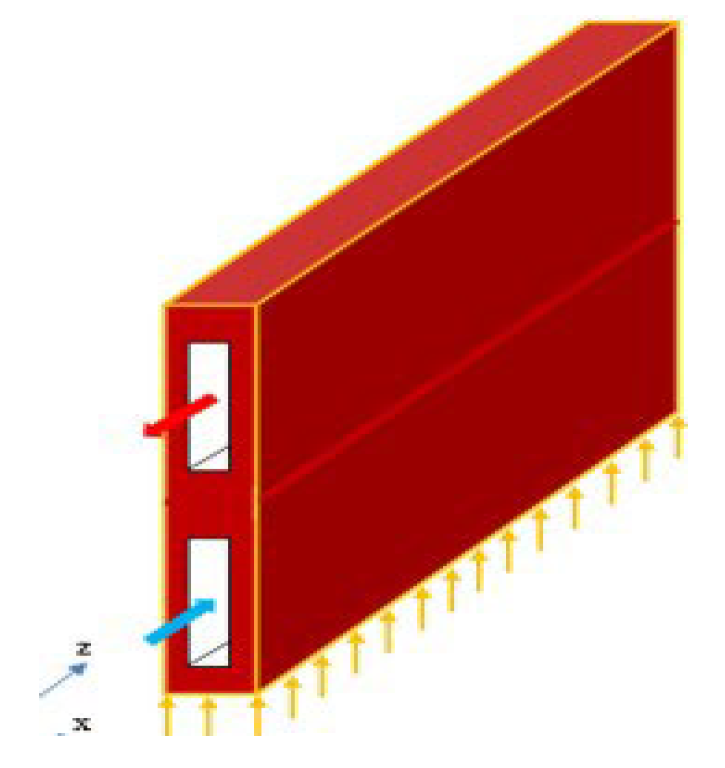

- Yang, M., Li, M.-T., Hua, Y.-C., Wang, W., & Cao, B.-Y. (2020). Experimental study on single-phase hybrid microchannel cooling using HFE-7100 for liquid-cooled chips. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 160, 120230.

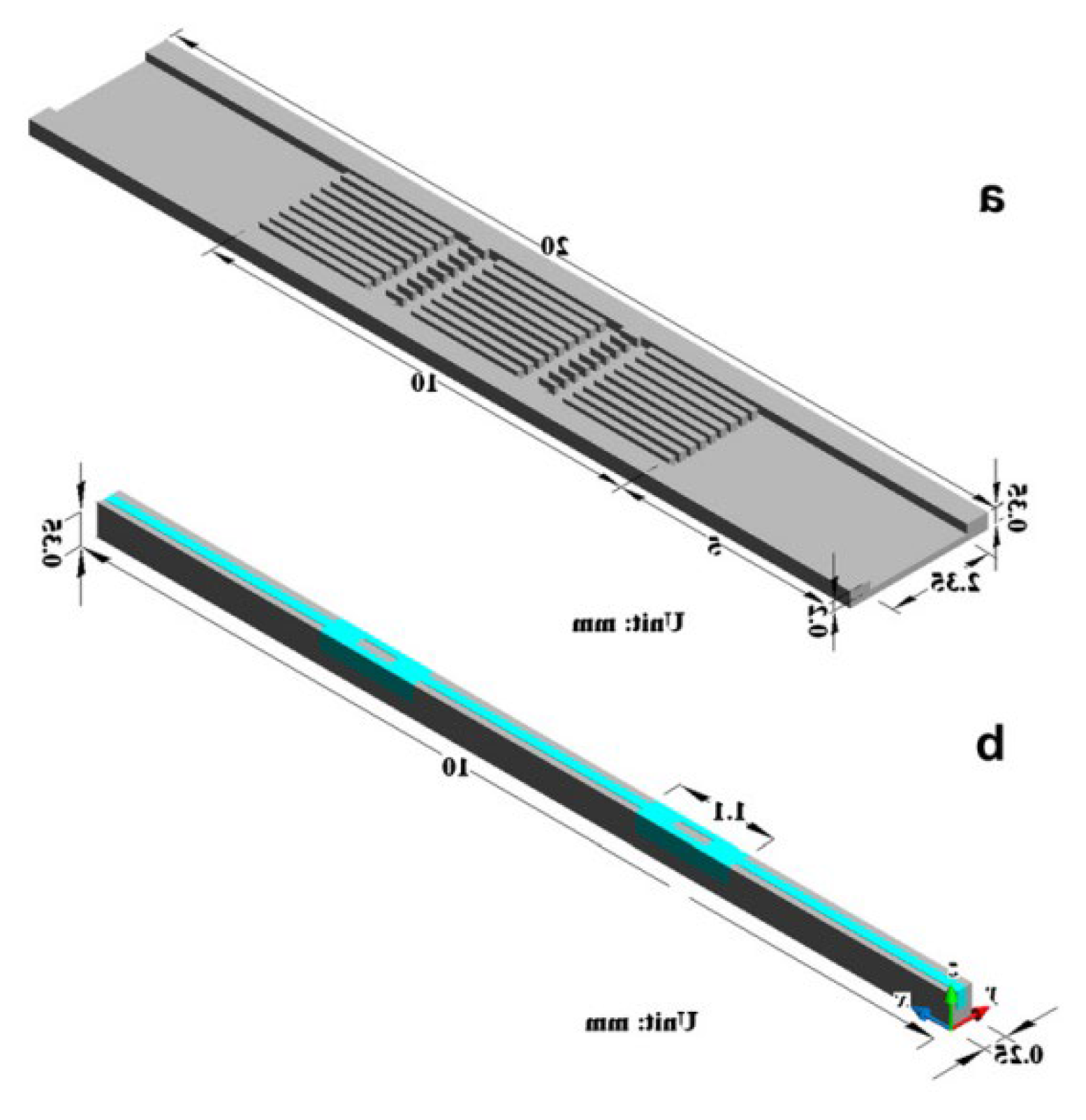

- Zhi-Qiang Yu, Mo-Tong Li and Bing-Yang Cao, International Journal of Extreme Manufacturing, Volume 6, Number 2.

- Min Yang , Mo-Tong Li , Xin-Gang Yu, Lei Huang , Hong-Yang Zheng , Jian-Yin Miao and Bing-Yang Cao, Applied Thermal Engineering Volume 212, 25 July 2022, 118550. [CrossRef]

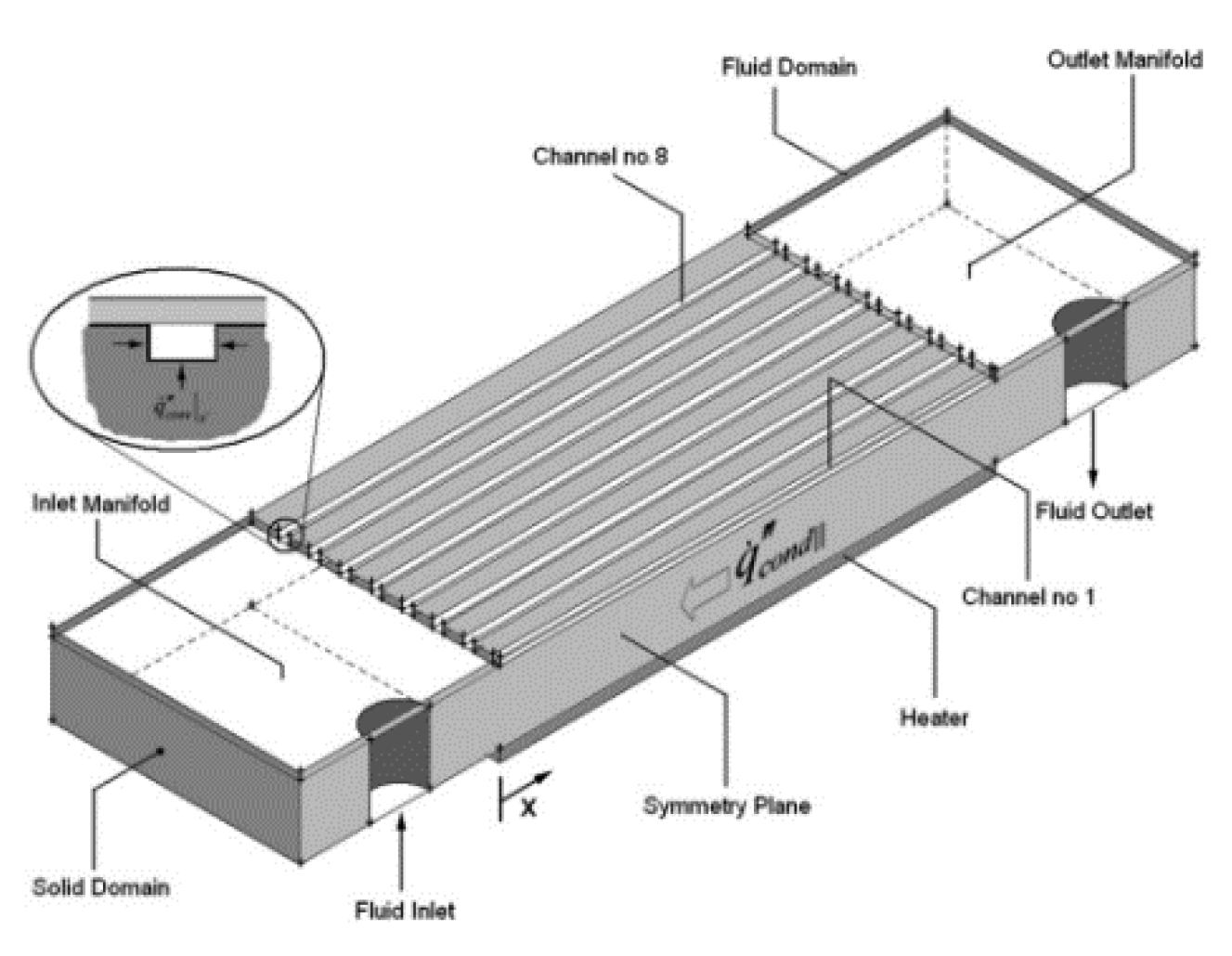

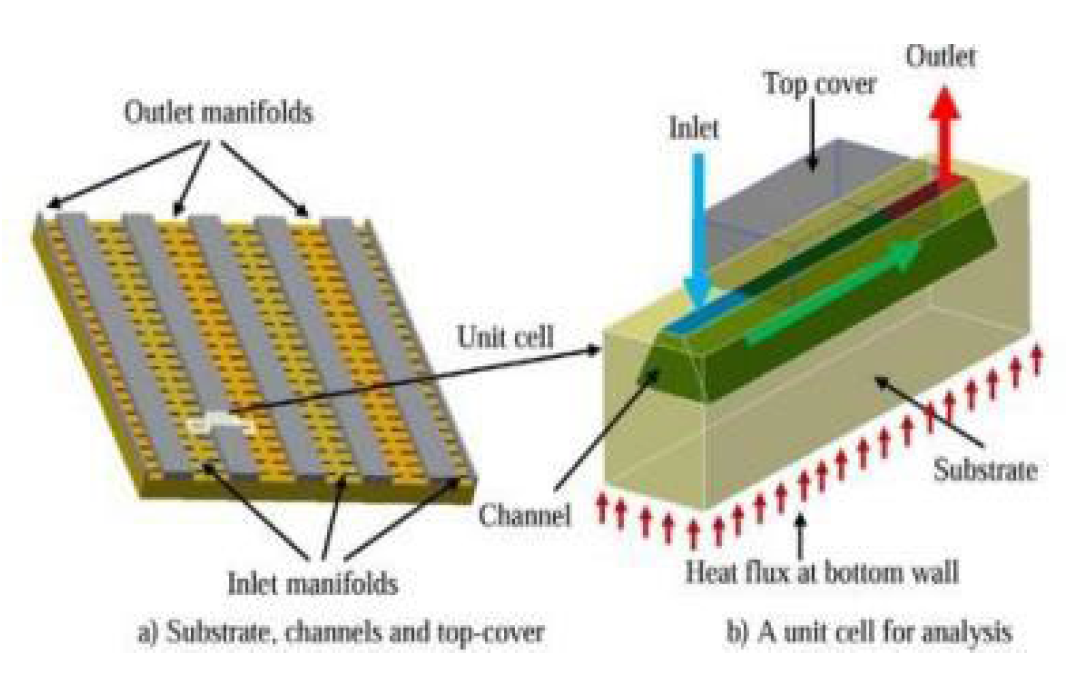

- Sharma, C.S., et al., Thermofluidics and energetics of a manifold microchannel heat sink for electronics with recovered hot water as working fluid. 2013. 58(1-2): p. 135-151.

- Li, Z., et al., Effects of thermal property variations on the liquid flow and heat transfer in microchannel heat sinks. 2007. 27(17-18): p. 2803-2814.

- Chen, C.-W., et al., Optimum thermal design of microchannel heat sinks by the simulated annealing method. 2008. 35(8): p. 980-984.

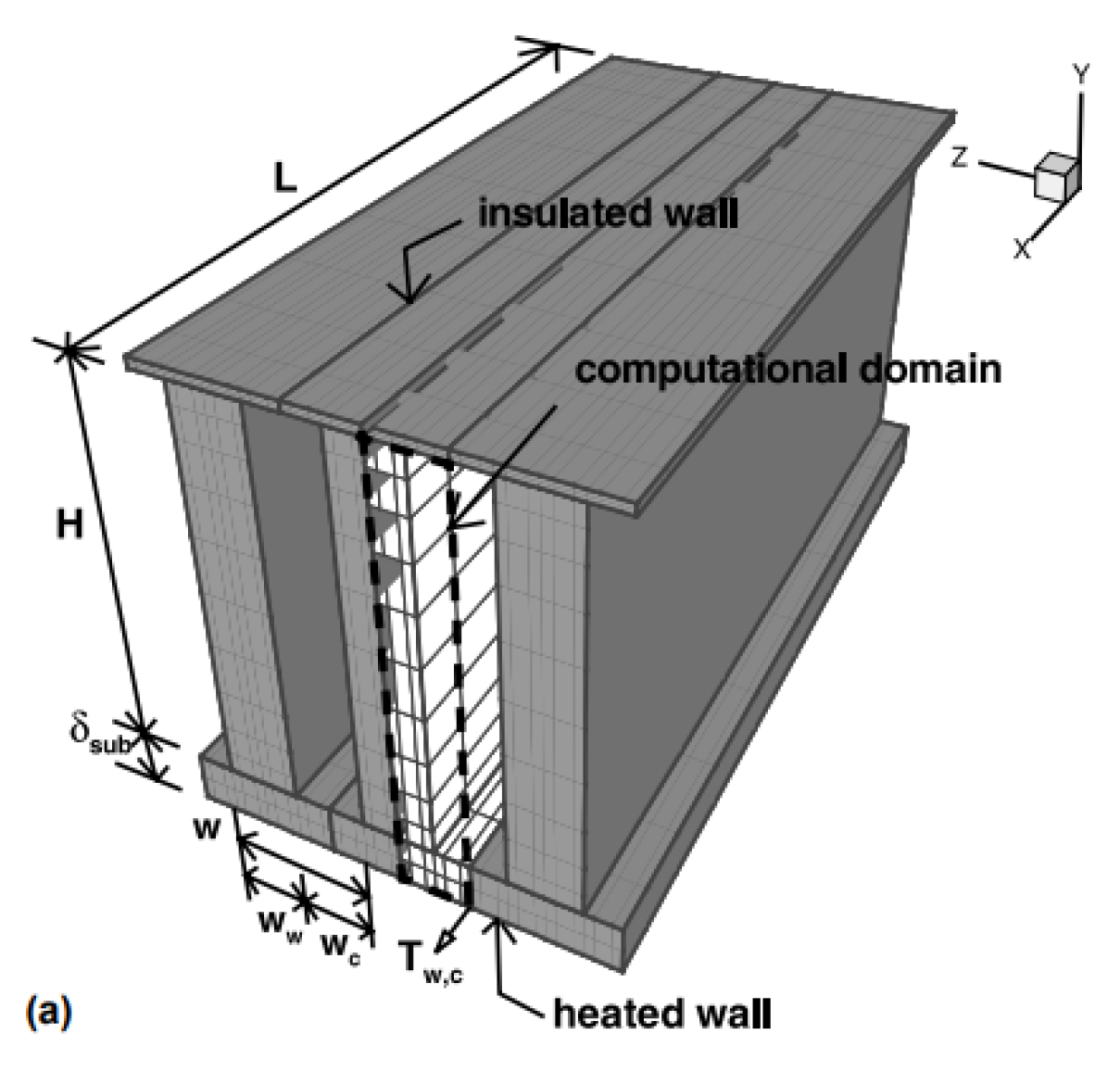

- Japar, W. M. A. A., Sidik, N. A. C., & Mat, S. (2018). A comprehensive study on heat transfer enhancement in microchannel heat sink with secondary channel. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, 99, 62–81.

- Chai, L., et al., Heat transfer enhancement in microchannel heat sinks with periodic expansion–constriction cross-sections. 2013. 62: p. 741-75182.

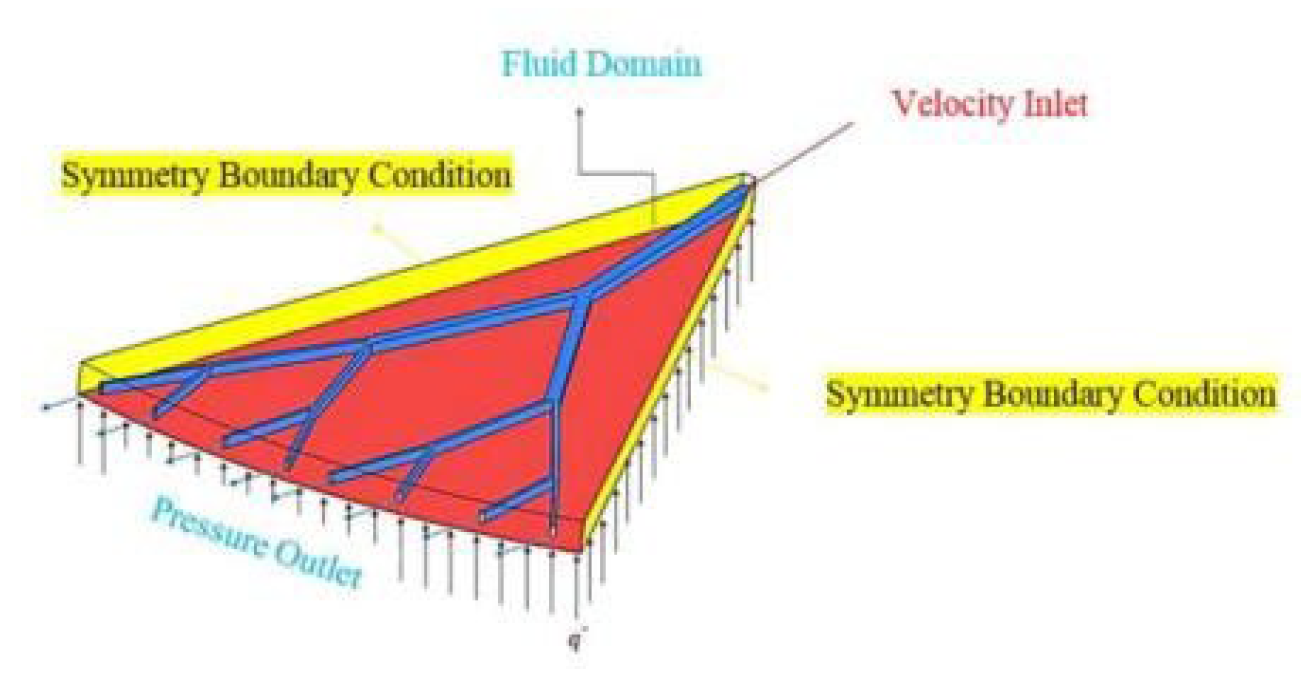

- Memon, S.A., et al., Hydrothermal investigation of a microchannel heat sink using secondary flows in trapezoidal and parallel orientations. 2020. 13(21): p. 5616.

- Yang, M., & Cao, B.-Y. (2020). Multi-objective optimization of a hybrid microchannel heat sink combining manifold concept with secondary channels. Applied Thermal Engineering, 115592.

- Gao, W., Zhang, J. F., Qu, Z. G., & Tao, W. Q. (2021). Numerical investigations of heat transfer in hybrid microchannel heat sink with multi-jet impinging and trapezoidal fins. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, 164, 106902.

- Raja Kuppusamy, N., Saidur, R., Ghazali, N. N. N., & Mohammed, H. A.., et al., Numerical study of thermal enhancement in micro channel heat sink with secondary flow. 2014. 78: p. 216-223.

- Bahiraei, M., Jamshidmofid, M., & Goodarzi, M., Efficacy of a hybrid nanofluid in a new microchannel heat sink equipped with both secondary channels and ribs. 2019. 273: p. 88-98.

- Wang, S.-L., Zhu, J.-F., An, D., Zhang, B.-X., Chen, L.-Y., Yang, Y.-R., … Wang, X.-D. (2022). Heat transfer enhancement of symmetric and parallel wavy microchannel heat sinks with secondary branch design. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, 171, 107229.

- Ma, D., Y. Tang, and G.J.A.T.E. Xia, Experimental investigation of flow boiling performance in sinusoidal wavy microchannels with secondary channels. 2021. 199: p. 117502.

- Razali, S., N. Sidik, and S. Yusof. Numerical studies of fluid flow and heat transfer in microchannel heat sink with trapezoidal cavities, ribs and secondary channel. in Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2021. DOI.

- Farzaneh, M., Salimpour, M. R., & Tavakoli, M. R. (2016). Design of bifurcating microchannels with/without loops for cooling of square-shaped electronic components. Applied Thermal Engineering, 108, 581–595.

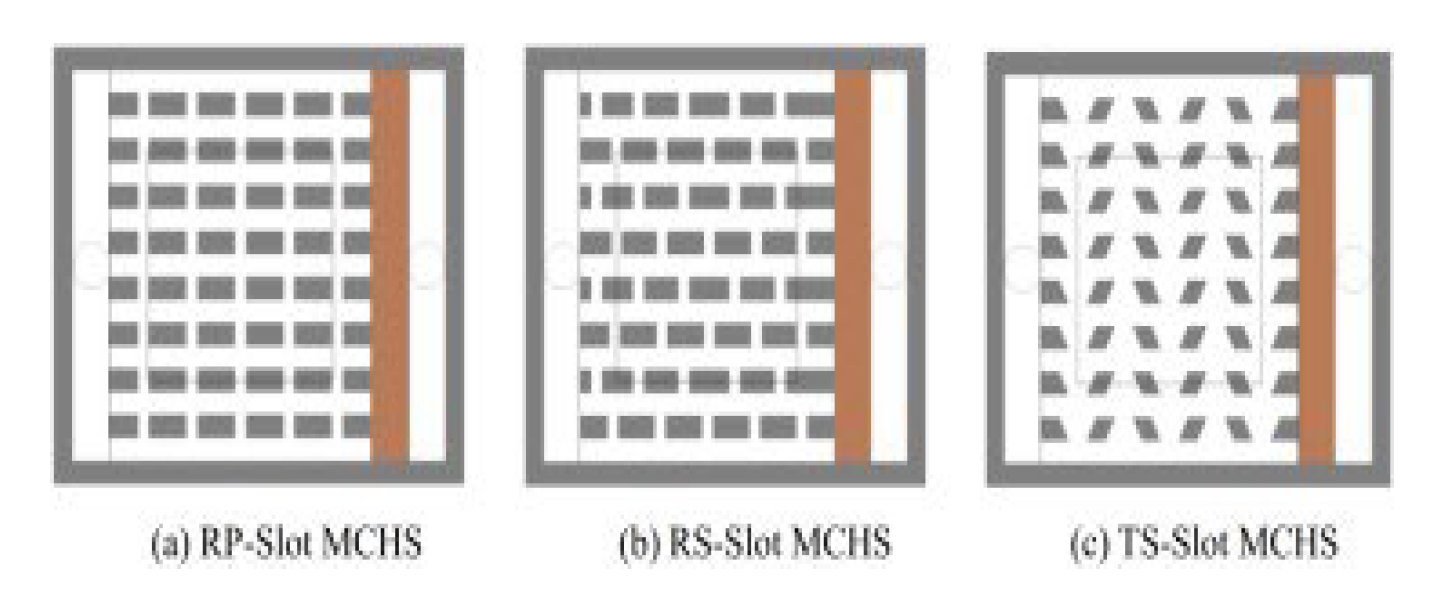

- Huang, S., et al., Thermal performance and structure optimization for slotted microchannel heat sink. 2017. 115: p. 1266-1276.

- Poh Seng Lee, Y.-J., P.-S. Lee, and S.-K. Chou. Experimental investigation of oblique finned microchannel heat sink+. in 2010 12th IEEE Intersociety Conference on Thermal and Thermomechanical Phenomena in Electronic Systems. 2010. IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y., et al. Numerical simulations of forced convection in novel cylindrical oblique-finned heat sink. in 2011 IEEE 13th Electronics Packaging Technology Conference. 2011. IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Ghani, I. A., Sidik, N. A. C., Mamat, R., Najafi, G., Ken, T. L., Asako, Y., & Japar, W. M. A. A. (2017). Heat transfer enhancement in microchannel heat sink using hybrid technique of ribs and secondary channels. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 114, 640–655.

- Lyu, Z., Pourfattah, F., Arani, A. A. A., Asadi, A., & Foong, L. K et al., On the Thermal Performance of a Fractal Microchannel Subjected to Water and Kerosene Carbon Nanotube Nanofluid. Scientific Reports, 2020. 10(1): p. 7243. [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, S., C.N. Azwadi, and A.J.J.A.R.M.S. Ahmad, The use of Fe3O4-H2O4 nanofluid for heat transfer enhancement in rectangular microchannel heatsink. 2016. 23: p. 15-24.

- Sivakumar, A., Alagumurthi, N., & Senthilvelan, T. (2015). Effect of Serpentine Grooves on Heat Transfer Characteristics of Microchannel Heat Sink with Different Nanofluids. Heat Transfer-Asian Research, 46(3), 201–217. [CrossRef]

- Snoussi, L., et al., Numerical simulation of nanofluids for improved cooling efficiency in a 3D copper microchannel heat sink (MCHS). Physics and Chemistry of Liquids, 2018. 56(3): p. 311-331. [CrossRef]

- Sarafraz, M. M., Nikkhah, V., Nakhjavani, M., & Arya, A.., et al., Fouling formation and thermal performance of aqueous carbon nanotube nanofluid in a heat sink with rectangular parallel microchannel. Applied Thermal Engineering, 2017. 123: p. 29-39.

- Thansekhar, M. R., & Anbumeenakshi, C. (2017). Experimental Investigation of Thermal Performance of Microchannel Heat Sink with Nanofluids Al2O3/Water and SiO2/Water. Experimental Techniques, 41(4), 399–406. [CrossRef]

- Arani, A. A. A., Akbari, O. A., Safaei, M. R., Marzban, A., Alrashed, A. A. A. A., Ahmadi, G. R., & Nguyen, T. K. et al., Heat transfer improvement of water/single-wall carbon nanotubes (SWCNT) nanofluid in a novel design of a truncated double-layered microchannel heat sink. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 2017. 113: p. 780-795.

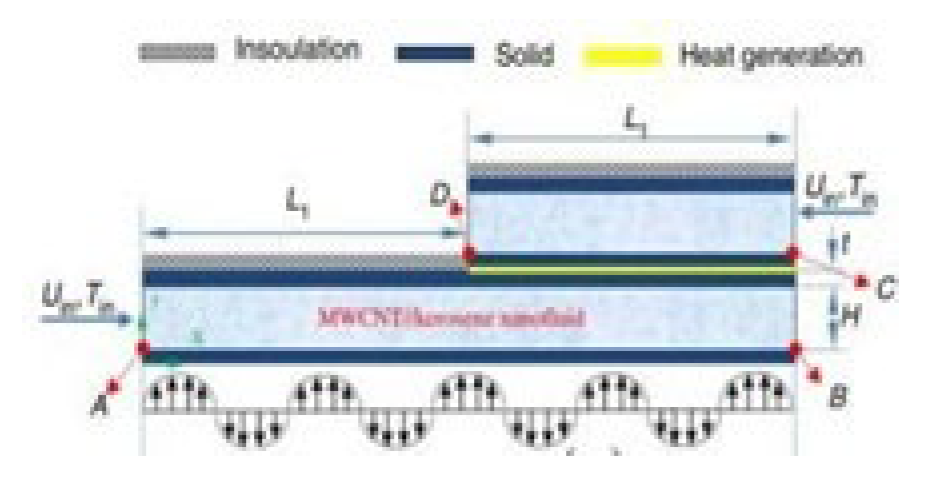

- Arabpour, A., Karimipour, A., & Toghraie, D. (2017). The study of heat transfer and laminar flow of kerosene/multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) nanofluid in the microchannel heat sink with slip boundary condition. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 131(2), 1553–1566. [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, A., Sharma, R. N., Mohammed, H. A., & Vatani, A., et al., Heat transfer and flow analysis of Al 2 O 3 -Water nanofluids in interrupted microchannel heat sink with ellipse and diamond ribs in the transverse microchambers. Heat Transfer Engineering, 2017. 39. [CrossRef]

- Altayyeb ALFARYJAT1, Adina-Teodora GHEORGHIAN2, Ahmed NABBAT3, Mariana-Florentina ȘTEFĂNESCU4, Alexandru DOBROVICESCU5, et al., The impact of different base nanofluids on the fluid flow and heat transfer characteristics in rhombus microchannels heat sink. UPB Scientific Bulletin, Series D: Mechanical Engineering, 2018. 80: p. 181-194.

- Sarafraz, M. M., Nikkhah, V., Nakhjavani, M., & Arya, A. (2018). Thermal performance of a heat sink microchannel working with biologically produced silver-water nanofluid: Experimental assessment. Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science, 91, 509–519.

- Tran, N., Y.-J. Chang, and C.-C. Wang, Optimization of thermal performance of multi-nozzle trapezoidal microchannel heat sinks by using nanofluids of Al2O3 and TiO2. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 2018. 117: p. 787-798.

- Razali, A.A., A. Sadikin, and S.A. Ibrahim, Heat transfer of Al2O3 nanofluids in microchannel heat sink. 2017. 1831(1): p. 020050.

- Chabi, A. R., Zarrinabadi, S., Peyghambarzadeh, S. M., Hashemabadi, S. H., & Salimi, M. (2016). Local convective heat transfer coefficient and friction factor of CuO/water nanofluid in a microchannel heat sink. Heat and Mass Transfer, 53(2), 661–671. [CrossRef]

- Manay, E. and B. Sahin, Heat Transfer and Pressure Drop of Nanofluids in a Microchannel Heat Sink. Heat Transfer Engineering, 2017. 38(5): p. 510-522. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.-H., & Chein, R. (2007). Performance analysis of nanofluid-cooled microchannel heat sinks. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow, 28(5), 1013–1026.

| S.No | Authors | Geometry | Nature of Work | Substrate Material | Coolant Type | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | D. B. Tuckerman. et al. [11] | Rectangular | Experimental | Silicon | Water | Maximum thermal resistance of 0.1oC/W for 1cm2 area Thermal resistance depends on water flow rate |

| 2 | Guilian Wang.et al [30] | Rectangular with Microscale Ribs and Grooves | Experimental and Numerical | Silicon | Water | Nusselt number is 1.55 times and friction factor is 4.09 greater than smooth channel |

| 3 | G. D. Xia et al [31] | Rectangular with arc-shaped ribs and grooves | Numerical | Silicon | Water | Relative rib height shows best performance in terms of thermal resistance |

| 4 | Faraz Ahmad.et al [32] | Rectangular with cylindrical ribs and cavities | Numerical | Silicon | Water | Maximum Nu value of 20 at Re 1000 Maximum thermal enhancement factor of 1.02 |

| 5 | Shahzad Ali. et al. [33] | Rectangular with Hydrofoil Ribs | Numerical | Copper | Water | Nu value of 15 at Re 1000 Thermal enhancement factor value of 1.07 |

| 6 | Aatif Ali Khan. et [34] | Rectangular heat sink with different ribs configuration. | Numerical | Silicon | Water | Rectangular ribs show greatest pressure drop of 100kpa Nu value of 8.5 at Re 500 Thermal enhancement factor of 0.91 |

| 7 | Yao Hsien. et al. [35] | Rectangular with ribs and grooves | Experimental | Copper | Water | Heat transfer coefficient increased by 40% (Nu value of 300) Thermal enhancement factor of 2.8 for discrete ribs and grooves |

| 8 | Lau. et al. [36] | Square with Staggered Ribs | Experimental | Copper | Water | Discrete ribs show superior performance than ribbed walls |

| 9 | Shizhong Zhang. et al. [37] |

Rectangular with trefoil-shaped ribs |

Numerical | Copper | Water | Maximum Nu of 30 at Re 1000 Thermal Enhancement factor of 1.5 Maximum entropy augmentation number of 0.72 |

| 10 | Guilian Wang.et al [38] | Rectangular with bidirectional Ribs | Experimental and Numerical | Silicon | Water | Thermal enhancement factor greater than 1 Nu 1.42 times higher with bidirectional ribs (Nu value of 13) |

| 11 | Sadiq Ali. et al. [39] | Rectangular with trefoil-shaped ribs | Numerical | Copper | Water | Maximum pressure drop of 60kpa Maximum Nu value of 29 Thermal Enhancement factor of 1.60 at Re 1000 |

| 12 | M. M. U. Rehman.et al [40] | Rectangular with Side wall Ribs | Numerical | Copper | Water | Maximum thermal enhancement factor of 1.10 Maximum average heat transfer coefficient value of 19 at Re 1000 Highest pressure drop of 19kpa at Re 1000 |

| 13 | Ihsan Ali Ghani.et al [41] | Rectangular with rectangular ribs and sinusoidal cavities | Numerical | Silicon | Water | Performance factor value of 1.83 at Re 800 Average Nu value of 24 at Re 1000 |

| 14 | Lei Chai. et al. [42] | Interrupted with rectangular ribs | Numerical | Silicon | Water | Thermal enhancement factor of 1.3 Interrupted channel without ribs shows high heat transfer |

| 15 | Y.F. Li. et al. [43] | Rectangular with rectangular ribs and triangular cavities | Numerical | Silicon | Water | Thermal enhancement factor of 1.6 at Re 500 Entropy augmentation number of 0.95 Average Nu value of 17 |

| 16 | Y.L. Zhai. et al. [21] | Rectangular with rectangular, trapezoidal, and circular ribs | Numerical | Water | Maximum Nu value of 15 at Re 600 Thermal enhancement factor of 1.6 Field synergy number of 14 Entropy augmentation number of 0.94 |

|

| 17 | Ayodeji S. Binuyo [44] | Interrupted | Numerical | Silicon | Water | Highest Nu value of 14 Average friction factor value of 0.08 |

| 18 | Abdelkader Korichi.et al [45] | Rectangular with heated obstacles | Numerical | Highest Nu value of 23 Increase in friction factor by factor of 19 |

||

| 19 | Aparesh Datta. et al. [46] | Microchannel with Triangular cavities and ribs | Numerical | Silicon | Water | Highest Nu value of 18 Highest friction factor value of 0.80 Performance factor value of 1.45 |

| 20 | Faraz Ahmad. et al. [47] | Rectangular with side wall ribs | Numerical | Copper | Water | Base and side walls ribs show superior performance than all wall |

| 21 | Q.Zhu et al. [48] | Rectangular with rectangular grooves and different-shaped ribs | Numerical | Silicon | Water | Highest pressure drop value of 119kpa Average Nu value of 22 Maximum thermal efficiency of 145% |

| S. No | Author | Nature of work |

Geometry | Coolant type |

Substrate Material | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pankaj Kumar [50] | Numerical | trapezoidal MCHS with the groove structure | Water | Silicon | Performance factor of 0.62 Friction factor of 0.026 Maximum Pressure drop of 140kpa |

| 2 | Hamdi E. Ahmed.et al [49] | Numerical | Grooved MCHS | Water | Aluminum | Maximum Performance evaluation factor of 2 Average Nusselt number ratio of 1.9 |

| 3 | Guodong Xia.et al [51] | Numerical | MCHS with triangular reentrant cavities | Water | Silicon | Highest thermal enhancement factor of 1.6 Friction factor value of 73 |

| 4 | Cila Herman.et al [52] | Experimental | grooved MCHS with curved vanes |

Air | Copper | Pressure drop increase by 3-5 times than smooth channel Heat transfer increase by 1.5-3.5 times than smooth channel |

| S. No | Author | Nature of Work | Geometry | Coolant type | Substrate Material | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mohib-ur-Rehman.et al [46] | Numerical | MCHS with hemispherical shape protrusions/ dimples |

Water | Copper | Maximum pressure drop value of 50kpa Friction factor value of 3.5 Entropy augmentation number of 0.85 |

| 2 | Minghai Xu. et al. [54] | Numerical | MCHS with dimples | Water | Copper | Highest Nusselt number value of 20 Performance improved by increasing number of dimples |

| 3 | Yu Chen. et al. [55] | Numerical | MCHS with turbulent flow over the dimpled surface | _ | _ | Highest Performance ratio of 2.8 |

| 4 | Moon. et al. [56] | Experimental | Rectangular MCHS with concavities | _ | _ | Normalized Nu value of 2.1 Thermal enhancement factor of 1.75 |

| 5 | Suabsakul Gururatana [57] | Numerical | Rectangular MCHS with dimpled surfaces | Air | _ | Maximum pressure drop of 8Pa at Re 350 Local Nu value of 17 Performance factor of 1.016 |

| S. No | Author | Nature of Work |

Geometry | Coolant type | Substrate Material | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nawaz Khan. et al. [17] |

Numerical | Rectangular MCHS having pin fins configuration of varying height | Deionized ultra-filtered water | Copper | Highest pressure drop of 7000Pa Nu value of 13 Thermal enhancement factor of 1.4 |

| 2 | Dogan.et al [16] | Experimental | Rectangular MCHS with Longitudinal fins |

Air | Silicon | Maximum convection heat transfer coefficient value of 27 Highest Nu value of 250 |

| 3 | F.Hong.et al [58] |

Numerical | Rectangular MCHS with offset strip-fin | Water | Silicon | Pumping power value of 0.21 W Maximum Presssure drop value of 120kPa |

| Ping Li. et al. [59] | Numerical | Rectangular MCHS with dimple and pin-fin | Water |

- |

Performance factor of 1.9 Highest Nu ratio value of 2.3 |

| S. No | Author | Nature of Work |

Geometry | Coolant type |

Substrate Material | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chu.et al61] | Experimental | Triangular MCHS | Water | Silicon | Friction factor value of 21 Highest Nu value of 0.7 |

| 2 | Daxiang Deng. et al. [62] | Numerical and Experimental | MCHS with semi-closed omega-shaped configuration. | Deionized Water | Oxygen-free Pure copper | Pressure drop of 8kpa Maximum thermal resistance value of 0.41oC/W |

| 3 | Ping cheng.et al [63] | Experimental | trapezoidal MCHS | Water | Silicon | Nu value of 4 at Re 700 Apparent friction factor value of 32 |

| 4 | H.A. Mohammed. et al. [64] | Numerical | Rectangular MCHS with various wavy amplitudes | Water | Aluminum | Maximum friction factor value of 0.55 Pressure drop value of 6.2kPa |

| 5 | Gunnasegran.et al [65] | Numerical | zigzag, curvy, and step microchannel heat sinks | Water | Aluminum | Heat transfer coefficient value of 9.64 Maximum pressure drop of 2800Pa Poiseuille number value of 25 |

| 6 | H. Ghaedamini.et al [66] | Numerical | converging-diverging MCHS | Water | Silicon | Highest Nu value of 30 Performance factor of 1.18 |

| 7 | X. F. Peng.et al [67] | Experimental | Squared Shape MCHS | Water | Silicon | Highest Nu value of 4.61 Heat transfer coefficient value of 30500W/m2 |

| 8 | Xiang-Qi Wang.et al [68] | Numerical | Rectangular (tree shape ) MCHS |

Water | Silicon | Pressure drop value of 320Pa Studied temperature distribution |

| 9 | John P. Mchale.et al [69] | Numerical | Trapezoidal and square shape MCHS | Water, ethylene glycol, air, and mercury | Silicon and polycarbonate aluminum | Local Nu value of 70 Average Nu value of 90 |

| S.No | Authors | Geometry | Nature of Work | Substrate Material | Coolant Type | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wang. X.Q. et al. [68] | Pin fins | numerical | copper | Air | Pressure drop value of 330Pa |

| 2 | Mchale. et al. [69] | Pin fins | numerical | aluminum | air | Friction factor value of 24 Nu value of 70 |

| 3 | Harley, J.C. et al. [70] | Plate fin heat sink | numerical | Aluminum alloy | air | Khudsen number less than 0.38 |

| 4 | Ping. et al. [59] | MCHS with dimple and pin fin | numerical | air | Performance factor of 1.9 Highest Nu ratio of 2.4 Maximum friction factor ratio of 1.9 |

|

| 5 | Tiseli.I .et al [71] | Plate fin heat sink | Analytical | copper | Ambient air | Nu value of 5.1 Average temperature of 330K |

| 6 | Harms. et al. [72] | MCHS variable pin fin configuration | Numerical | copper | water | Nu value of 110 Pressure drop value of 60kPa |

| 7 | Toh, K.C. et al. [73] | Rectangular Micro channel | Numerical | Silicon | Water | Thermal resistance value of 0.30 cm2. K/W Friction factor value of 150 |

| 8 | Gamrat, G,. et al. [74] | Rectangular Microchannel | Numerical | Silicon | Water | Nu value of 30 Poiseuille number value of 40 |

| 9 | Xu, J. L. et al. [75] | Rectangular MCHS | numerical | Copper, aluminum, silicon | Water | Nu value of 16 Friction factor value of 0.02 |

| 10 | Peng, X. et al. [76] | Rectangular MCHS | Numerical | Silicon | water | Nu value of 10 Heat transfer coefficient value of 7000W/m2. K |

| 11 | Betz, A.R. et al. [77] | Rectangular MCHS | Numerical | Silicon | Water | Nu value of 14 Pressure drop of 38kPa |

| 12 | Toh, K.C. et al. [73] | Rectangular MCHS | Numerical | Silicon | Air | Friction factor value of 70 Thermal resistance of 0.28cm2/K/W |

| 13 | Zade, A.Q al [78] | Rectangular MCHSs | Numerical | Copper | Water-Air | Nu value of 33 Friction factor value of 70 |

| S.No | Authors | Geometry | Nature of Work | Substrate Material | Coolant Type | Results Obtained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Weilin Qu. et al. [19] | Rectangular Microchannel | Experimental and Numerical | Silicon | Water | Average Nu value of 30 Average temperature of 120oC |

| 2 | Deng, B. et al. [79] | Rectangular Microchannel | Experimental | Silicon | Water | Thermal resistance value of 0.19K/W |

| 3 | Saenen. T. et al. [80] | Triangular Microchannel | Experimental and Numerical | Silicon | Water | Average temperature of 128oC |

| 4 | Sharma, C.S. et al. [84] | Rectangular Microchannel | Experimental | Silicon | Water | Pressure drop of 1600Pa Fluid outlet temperature of 65oC Thermal resistance of 0.285oCcm2/W |

| 5 | Japar, W.M.A.A. Al [87] | Rectangular Microchannel | Experimental | Silicon | Water | Nu value of 10 Pressure drop value of 70kPa Nu ratio of 2.3 |

| 6 | Chai, L et al. [88] | Rectangular Microchannel | Experimental | Silicon | Water | Pressure Drop of 60kPa Friction factor value of 60 Nu value of 15 |

| 7 | Chen,C.W.et al [86] | Rectangular Microchannel | Numerical and Experimental | Bronze Block | Water | Thermal resistance of 0.4o C/W/cm2 Large flow power can develop low thermal resistance MCHS |

| 8 | Memon, S.A.et al [89] | Rectangular Microchannel | Experimental | Aluminium | Water | Pressure drop of 2.8Pa Minimum Average temperature of 311K |

| 9 | Yang, M [90] | Rectangular Microchannel | Numerical | - | - | Pumping power of 2.1W Thermal resistance of 1.3K/W |

| 10 | Gao, W.. et al. [91] | Rectangular Microchannel | Numerical | - | - | Pressure drop of 32000Pa Pumping power of 0.01W Nu value of 22 |

| 11 | Kuppusammy,N.R.. et al. [92] | Array Minichannel | Experimental and Numerical | Copper | Water | Nu value of 12.5 with pressure drop of 20kPa |

| 12 | Bahiraei. et al. [93] | Microchannel Heat Sink | Numerical | Silicon | Water | 17% improvement in convective heat transfer coefficient |

| 13 | Min Yang. Et al [83] | Microchannel heat sink with manifold and oblique channels | Experimental | Copper | Water |

Pressure drop of 4.2kPa Friction factor value of 17 |

| S. No | Author | Geometry | Nature of work | Substrate Material | Coolant type | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saenen, T. et al. [80] | Rectangular MCHS | Numerical | Silicon | Air | Maximum temperature of 126oC |

| 2 | Wang S.l. et al. [94] | Rectangular MCHS with turbulent flow | Numerical | Copper | Hot Water | Studied Dean vortex Secondary branches weaken dean vortex |

| 3 | Ali Kosar [14] | Rectangular MCHS |

Numerical | Polyimide, Silica Glass, Quartz, Steel, Silicon, Copper | Water | Nu value of 4 Friction factor of 0.7 |

| 4 | Tsung-Hsun Tsai.et al [117] | Rectangular MCHS with Porous medium | Numerical | Silicon | Cu–water CNT–water | Pressure drop of 350kPa Thermal resistance of 0.073oC/W |

| 5 | Zhigang. et al. [85] | Rectangular microchannels | Numerical | Copper silicon stainless steel | Water | Local friction coefficient of 1 Heat transfer coefficient of 200kW/m2.K Nu vlaue of 25 |

| 6 | Chien-Hsin Chen [18] | Rectangular MCHS |

Numerically | Nu value of 280 Dimensionless velocity of 0.6 |

||

| 7 | Chih-Wei Chen. et al. [86] | Rectangular MCHS |

Silicon | Water | Thermal resistance of 0.4oC/W/cm2 |

| S.No | Author | Geometry | Nature of work | Substrate Material | Coolant type | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wan Mohd. et al. [8] | Rectangular MCHS | numerical | copper | water | Review of literature |

| 2 | Lei chai. et al. [51] | Rectangular MCHS with triangular cavities | Experimental and numerical | silicon | water | Thermal enhancement factor of 1.6 Nu ratio f 1.8 |

| 3 | Ghani. et al. [101] | Rectangular MCHS with ribs and cavities | numerical | copper | water | Friction factor ratio of 4 Nu ratio of 2.2 Performance factor of 1.7 |

| 4 | Bahirae. et al. [93] | MCHS with ribs and secondary channels | numerical | Copper | Graphene–silver Nano particles | Secondary channel increases area thus reducing pressure drop |

| 5 | Shou lin wang. et al. [94] | Secondary flow branched design | numerical | Silicon | Water | Nu value of 18 Performance factor of 2.3 Thermal resistance value of 1.2 |

| 6 | GD Xia. et al. [95] | Sinusoidal secondary flow MCHS | Experimental | Silicon | Water | Heat trasfer coefficient value of 45 Pressure drop value of 240kPa |

| 7 | SA Razali. et al. [96] | MCHS design with trapezoidal cavities, ribs, and secondary channels | Numerical | Copper | Water | Performance factor of 1.8 Maximum Nu ratio of 2.3 Highest Friction facto ratio of 5.7 |

| 8 | Farzaneh. et al. [97] | Square-shaped MCHS with one and two initial loops. | Experimental | Silicon | Water | Pressure drop reduced by 25% |

| 9 | Huang. et al. [98] | Rectangular Parallel-Slot MCHS | Numerical | Copper | Water | Nu value of 21 Pressure drop ratio of 2000 Performance factor value of 1.95 |

| 10 | Poh Seng Lee. et al. [99] | Secondary flow MCHS with oblique fins | Experimental | Copper | Water | Average Nu value of 16 Thermal resistance value of 0.097OC/W Pressure drop value of 3000Pa |

| 11 | Yan Fan. et al. [100] | novel cylindrical discrete oblique fin MCHS with secondary flow | Numerical | Copper | Water | Pressure drop of 90Pa Heat transfer coefficient value of 3000W/m2. K |

| S. No |

Author | Geometry | Nature of work | Substrate Material | Coolant type | Results Obtained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | S.abubakar. et al. [103] | Straight Rectangular MCHS | numerical | silicon | Pure water, Fe3O4- H2O4 | Maximum average temperature of 316K |

| 2 | A.Sivakumar. et al. [104] | serpentine-shaped MCHS | Experimental and numerical | copper | Ethylene glycol-based CuO, water-based CuO, and Al2O3 | Heat transfer coefficient value of 42kW/m2. K Pressure Drop of 0.30kPa |

| 3 | L.snoussi. et al. [105] | Rectangular Cross section 3D MCHS | numerical | copper | Al2O3-water, Cu–water | Heat transfer coefficient value of 16kW/m2.K Friction factor value of 0.07 |

| 4 | Sarafraz. et al. [106] | Rectangular MCHS | experimental | copper | Multi-walled carbon nanotubes | Heat transfer coefficient value of 7000W/m2.K Thermal resistance value of 0.11W/o C |

| 5 | Thansekhar. et al. [107] | Rectangular MCHS | experimental | copper | Al2O3/water,SiO2/water | Heat transfer coefficient value of 180W/m2.K Thermal resistance value of 1.1K/W Pressure drop value of 0.035bar |

| 6 | A.A.A Arani. et al. [108] | Truncated double-layer MCHS | numerical | silicon | water/single-wall carbon nanotubes (SWCNT) | Maximum Pressure drop value of 500kPa Highest Friction factor value of 0.21 Average Nu value of 3 |

| 7 | Arabpour, A.et al [109] | Zigzag flow channels |

experimental | copper | SiO2/ DI water | Nu value of 14 Enhancement ratio of 1.2 Maximum Pressure drop value of 110kPa |

| 8 | R.Vinoth. et al. [7] | Oblique finned MCHS with square, semicircle, and trapezoidal cross-sections | experimental | copper | Al2O3/water | Nu value of 19 Pressure drop of 20kPa Friction factor of 3.8 |

| 9 | Abollahi.et al [110] | Interrupted MCHS with ellipse and diamond ribs. |

numerical | copper | Al2O3/water | Highest Nu value of 13 Maximum Friction factor value of 0.34 Highest performance factor of 1.3 |

| 10 | Altayyeb Alfaryajat.et al [111] | 3D rhombus MCHS | numerical |

- |

Al2O3 mixed with different four base fluids pure water engine oil glycerin ethylene glycol |

Heat transfer coefficient value of 27kW/m2. K Highest friction factor value of 0.040 |

| 11 | MM Sarafraz. et al. [112] | Straight rectangular MCHS | experimental | copper | Biologically produced silver-water | Highest heat transfer coefficient value of 7000W/m2.K Thermal resistance value of 0.11W/o C Maximum Pressure drop of 55kPA |

| 12 | Nagoctan Tran. et al. [113] | Multi nozzle trapezoidal MCHS | numerical | copper | Al2O3and TiO2 | Thermal resistance value of 0.35OC/W Highest Pressure drop of 55kPa |

| 13 | Zongjie Lyu. et al. [104] | Single-layer fractal MCHS |

numerical | silicon | water and kerosene | Highest Nu value of 45 Pumping power value of 0.15W Maximum performance factor of 2.3 |

| 14 | A.A Razali. et al. [114] | Rectangular MCHS | Experimental and numerical | copper | Al2O3 | Nu value of 6 |

| 15 | AR Chabi. et al. [115] | Rectangular MCHS | experimental | copper | CuO/water | Heat transfer coefficient value of 20000W/m2. K Average Nu value of 13 |

| 16 | Manay. et al. [116] | Rectangular MCHS | experimental | copper | TiO2–water | Nu value of 12 Thermal resistance value of 0.8OC/W |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).