1. Introduction

Waste generation, disposal, and utilization are currently among the most pressing issues in ensuring environmental safety and protection worldwide. This is primarily due to the increasing volumes of industrial waste and the insufficiently high level of development in the waste disposal sector. One such example is silicon alloys (metallurgical grade silicon and ferrosilicon) [

1,

2], whose production has remained at 9,000 metric tons per year for the past three years (2021-2023). In 2022, production slightly decreased to 8,800 metric tons due to the consequences of COVID-19 and geopolitical conflicts. In 2023, production volumes returned to previous levels [

3,

4].

During the production of 1 ton of metallurgical silicon, about 800 kg of microsilica is captured by gas cleaning systems [

5]. Annually, enterprises worldwide produce millions of tons of microsilica, a significant portion of which is stored in dumps, posing a serious threat to the environment. For example, companies such as Elkem (Norway), Ferroglobe (USA), RW Silicium (Germany), and others are major producers of silicon-containing alloys and products, accumulating significant volumes of microsilica in the course of their activities.

Currently, there are no industries for the widespread application of this secondary technogenic raw material. Primarily, microsilica can be used in the construction industry in areas such as concrete [

6,

7], cement [

8,

9], refractory materials [

10], and so on [

11]. However, this market cannot fully absorb all the microsilica produced annually. For example, in 2020, the volume of accumulated microsilica exceeded 2.5 million tons, while the needs of the construction industry were significantly lower. Such average annual technical and economic indicators significantly worsen the economics of production, not only highlighting the problem of insufficient technological solutions for the processing/utilization of microsilica but also creating an environmental problem associated with the storage of technogenic waste [

12].

A significant amount of dust from gas cleaning systems of electric arc furnaces is directed to dumps, which worsens the environmental situation and requires additional material costs for the transportation and storage of waste. The accumulation of microsilica in dumps leads to various environmental problems, related to air and water pollution.

Microsilica, a by-product in the production of ferrosilicon alloys or industrial silicon products [

13], mainly consists of fine amorphous SiO2 together with other oxides present in only hundredths of a percent, such as MgO, K2O, Fe2O3, and ZnO [

12,

14].

Microsilica is a valuable raw material for silicon production, as it has a high silicon dioxide content and extremely low levels of harmful components. This makes it a promising raw material source for smelting silicon alloys, particularly metallurgical grade silicon. However, the problems of processing microsilica are associated with its rather small particle size (0.1-0.2 microns), high specific surface area, and moisture content. This requires its pre-treatment, such as by pelletizing, for metallurgical processing.

The ongoing research aims to develop technologies for the co-briquetting of microsilica with carbon reducers, obtaining briquetted monocharge, and smelting technical silicon from them. Achieving close contact between silicon oxides of microsilica and solid carbon of carbon reducers in the briquette provides the most favorable conditions for reduction and silicon smelting. At the same time, it becomes possible to use small fractions of scarce low-ash carbon reducers (such as special coke) as reducers.

The use of microsilica in the production of metallurgical silicon will not only find a new application for this material but also reduce the environmental impact by reducing the volume of its accumulation. The development and implementation of this technology will not only solve the environmental problems associated with silicon waste generation and storage in the form of microsilica but also increase the overall silicon recovery to 90-92%, whereas currently, the recovery rate is 65-70%. Additionally, the silicon obtained from microsilica will be of the highest purity.

In this work, a series of studies were carried out to determine the physicochemical properties (heat tolerance, briquette reactivity, briquetting force) of composite briquettes depending on their different particle size distribution. The factors of heat tolerance and reactivity of briquettes were studied for the first time. The briquettes consisted of microsilica, small fractions of carbonaceous reducing agents (special coke, charcoal), as well as quartz screenings. The compositions of the briquettes were optimal for the complete reduction of silicon, that is, the optimal amount of solid carbon.

2. Materials and Methods

The In the present work, samples of microsilica from the production of LLP "Tau-Ken Temir" (Kazakhstan) were used. The samples of microsilica used in the work were studied using a dispersion analysis method with the PSH-10A device. Experiments conducted with this device allowed for the calculation of the specific surface area and the average particle size of microsilica. The absorbent capacity of the material's particles depends on the specific surface area. The principle of operation is based on the gas adsorption method, where the amount of gas adsorbed on the surface of the powder particles is analyzed. The average particle size was determined based on the gas adsorption distribution, and the specific surface area was calculated based on the total amount of adsorbed gas.

Briquettes, which included screenings of coking oxidation coke, wood charcoal screenings, condensed microsilica, and quartz screenings, are shown in

Figure 1.

These briquettes were produced on the large laboratory briquetting press ZZXM-4 (

Figure 2).

Four variations of the particle size distribution of the briquettes were studied:

1) Fraction 0-1 mm – 15%;

Fraction 1-3 mm – 50%;

Fraction 3-5 mm – 35%.

2) Fraction 0-1 mm – 35%;

Fraction 1-3 mm – 35%;

Fraction 3-5 mm – 30%.

3) Fraction 0-1 mm – 60%;

Fraction 1-3 mm – 25%;

Fraction 3-5 mm – 15%.

4) Fraction 0-1 mm – 100%;

Fraction 1-3 mm – 0%;

Fraction 3-5 mm – 0%.

The composition of the briquettes was based on considerations of silicon recovery during smelting. The consumption of coke was determined based on the stoichiometric amount of carbon required for the reduction of silicon oxide with an excess coefficient of 1.05. The ratio of fractions 0-1, 1-3, and 3-5 mm was 60:25:15. In subsequent experiments, to adjust the granulometric composition of the briquetting charge, additional quartz screenings of 0-5 mm fraction were introduced. The average chemical and granulometric compositions of the raw materials, as well as bulk densities, were as follows:

• Microsilica: 95.5% SiO₂ (amorphous), 4% C (carbon), 0.5% total impurities (CaO+Al₂O₃+Fe₂O₃) on a dry weight basis.

• Quartz screenings: 99.85% SiO₂, the remainder being total impurities (CaO+Al₂O₃+Fe₂O₃).

• Coke screenings: Ash 4-5%, volatiles 6-7%, fixed carbon 88%, moisture 1%.

Bulk density:

• Microsilica: 0.5 g/cm³,

• Coke screenings: 0.4-0.5 g/cm³,

• Quartz screenings: 1.2-1.3 g/cm³.

Moisture content:

• Microsilica: 1-2%,

• Coke screenings: 1%,

• Quartz screenings: 2-4%.

At the same time, the optimal consumption of the binder was determined. Liquid glass was used as a binder, which provides standard indicators for the briquetted charge. Liquid glass consumption was 0.067 t/t, and charge moisture content was 8%.

The influence of briquetting conditions on the heat tolerance of briquettes was further studied. In practice, over a long period of using briquetted raw materials not only in silicon production but also in other electrothermal industries, researchers have only qualitatively described the disintegration of briquettes when they hit the top of the electric arc furnace due to a sharp change in temperature. Hence, the term " heat tolerance " was coined to qualitatively describe the most important physical property of the briquettes. Here, for the first time, a methodology for the quantitative description of this property was proposed. In this paper, for heat tolerance evaluation the methodology of SMS Demag company was used [

1,

2,

15].

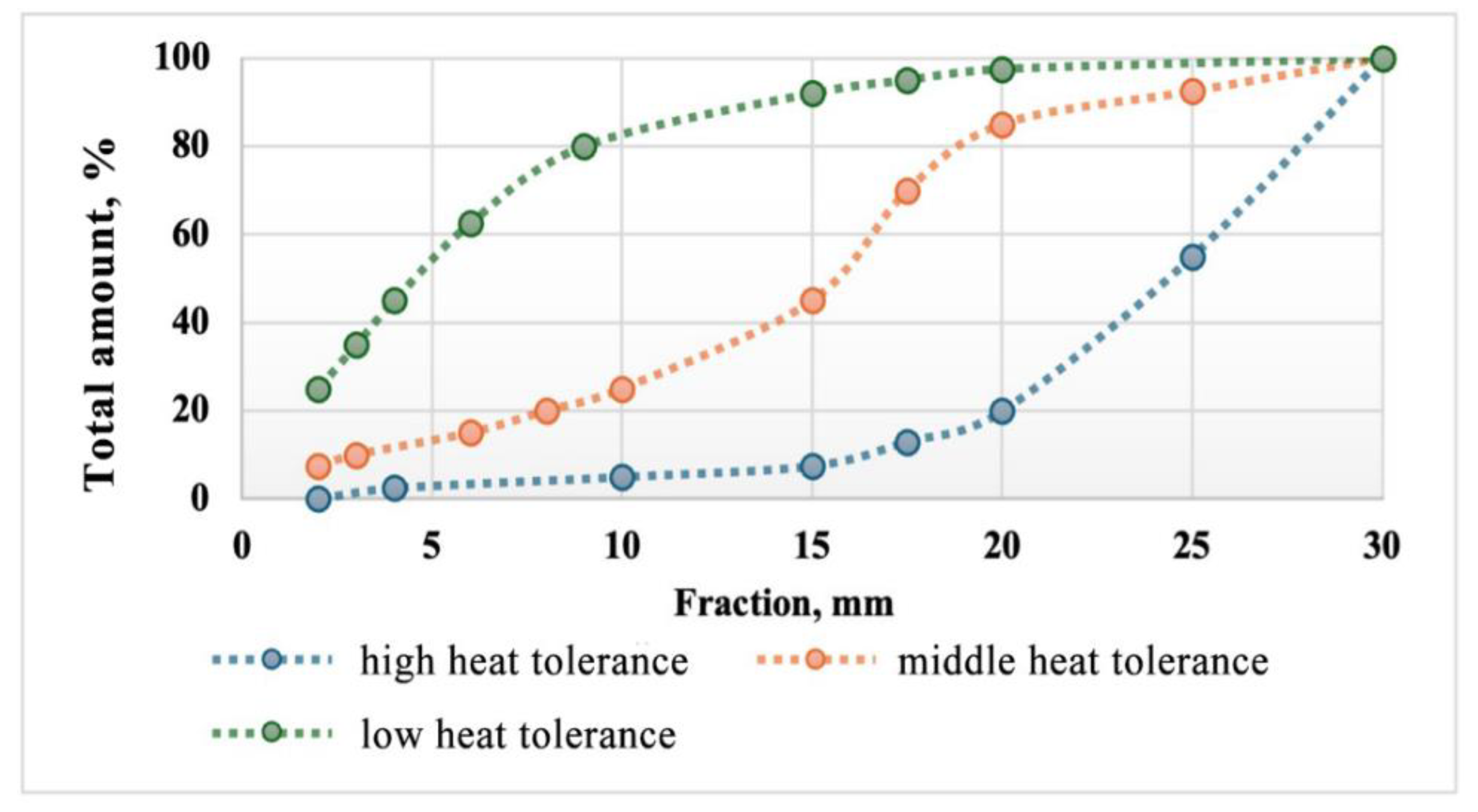

To determine heat tolerance samples of material of various fractions are placed in a heating crucible. Next, it is heated to 1300-1500 °C and held at these temperatures for an hour and cooled to room temperature. Samples of the +20 mm fraction are rolled in a steel drum 100 times at a speed of 40 rpm. After, based on the total number of sifted fractions (20, 10, 4, and 2 mm), a standard curve for assessing thermal drainage is constructed (

Figure 3).

To determine the heat tolerance of the briquettes under study, the assessment was carried out by evaluation the proportion of fine fractions after experiments (

Figure 4). It is also worth noting that for these briquettes their mechanical strength has not been studied. Since the connection between high rates of heat tolerance and mechanical strength is known. The thermal resistance of a briquette is defined as the ratio of the weight of the main body of the briquette after abrasion tests in a drum to the sum of the weight of the main body and the destroyed material.

The work also assessed the effect of drying briquettes on the heat tolerance. The briquettes were dried in two ways. The first involved natural drying during the day, during which the briquettes lose up to 50% moisture. Then the briquettes are kept in a chamber oven for 8-10 hours. At this stage, briquettes lose about 10% moisture. Afterwards, the briquettes were completely dried in air for 3-5 days. The second consisted of quick drying in an oven for 40 minutes with intensive air blowing at temperatures of 280-300 °C.

The reactive activity of the briquettes concerning the carbothermic reduction process was also evaluated. According to experimental data, in the production of technical silicon, the activity of the briquettes should be at least 40 units. The activity of the briquettes was determined by the degree of reduction of SiO2 as a result of heating for 30 minutes at 1700°C. The degree of reduction was determined by volumetric and gravimetric methods. Heating to the required temperature was carried out in a Tamman furnace in the reducing atmosphere of a sealed graphite crucible.

3. Results and Discussion

The results of measurements of the specific surface area and average particle size of microsilica are presented in

Table 1.

The obtained specific surface area (11730.67 cm²/g) is quite high for bulk materials used in metallurgical processing. At the same time, the high specific surface area indicates its fine dispersion, high absorptive, and reactive capacity. Based on measurements from the dispersion analysis instrument, it can be concluded that the specific surface area of microsilica is the sum of the surface areas of all its particles, and the smaller the size of these particles, the greater the total specific surface area.

Next, experiments of briquettes heat tolerance evaluation were conducted.

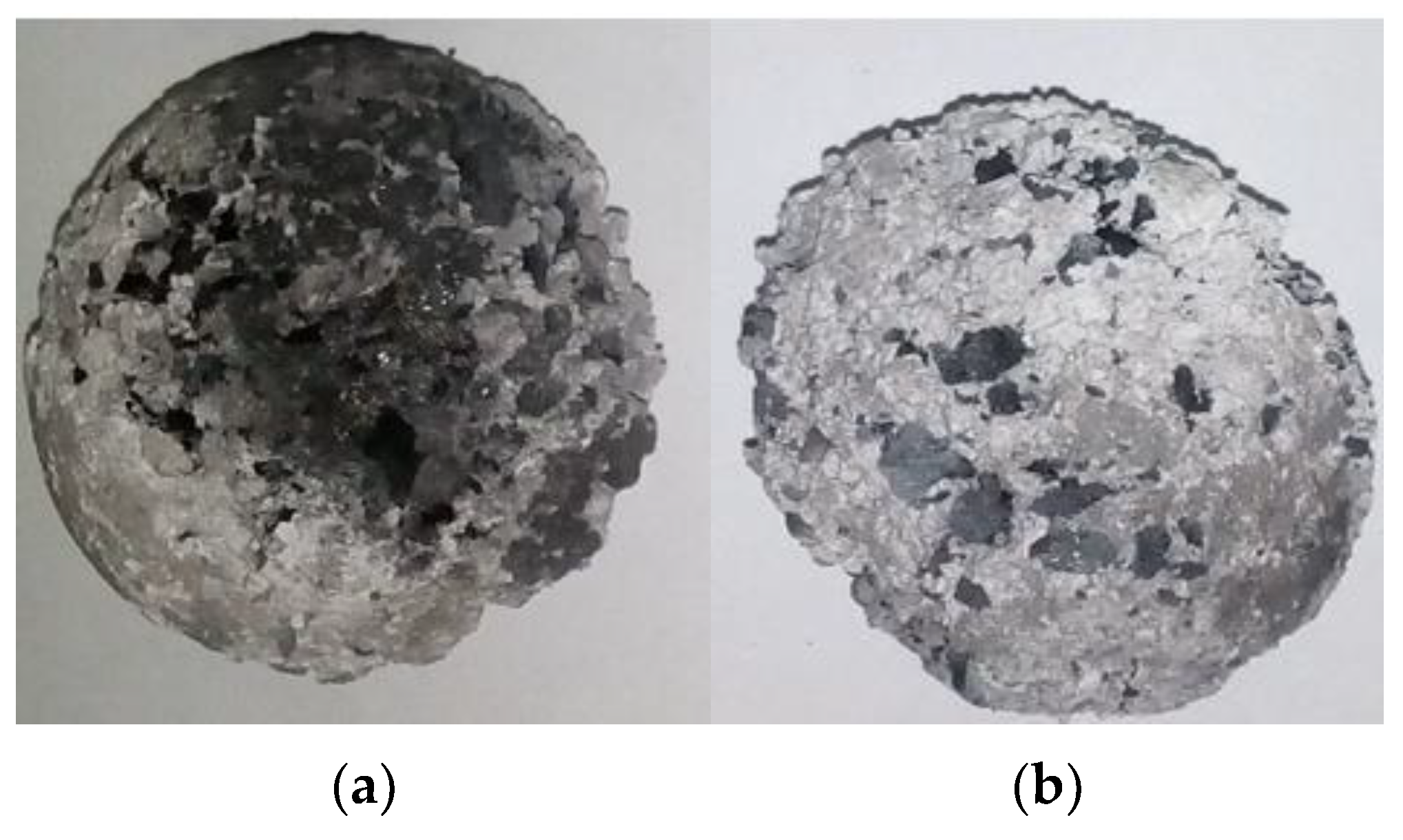

Figure 5 shows a photo of the briquette before the thermal shock (a) and immediately after it (b).

As can be seen from

Figure 5, the briquettes after thermal shock were covered with a white layer of silicon dioxide. In this layer, the carbon component burned out. As a result, the packing density of the particles was disrupted. Therefore, the oxidized layer is not mechanically strong and falls off from the surface of the briquette during the subsequent abrasion test.

Figure 6 presents the results of the briquettes heat tolerance of various compositions at various stages of the drying process.

The graph shows the heat tolerance of briquettes of different fractional compositions at various stages of drying. The highest heat tolerance (82%) was achieved with natural drying for 5–7 days for briquettes with a fractional composition of 35/35/30% (0-1; 1-3; 3-5 mm). Quick drying for 30 minutes in an oven gave the lowest results in terms of heat tolerance for all fractional compositions. In general, longer natural drying times result in better heat tolerance.

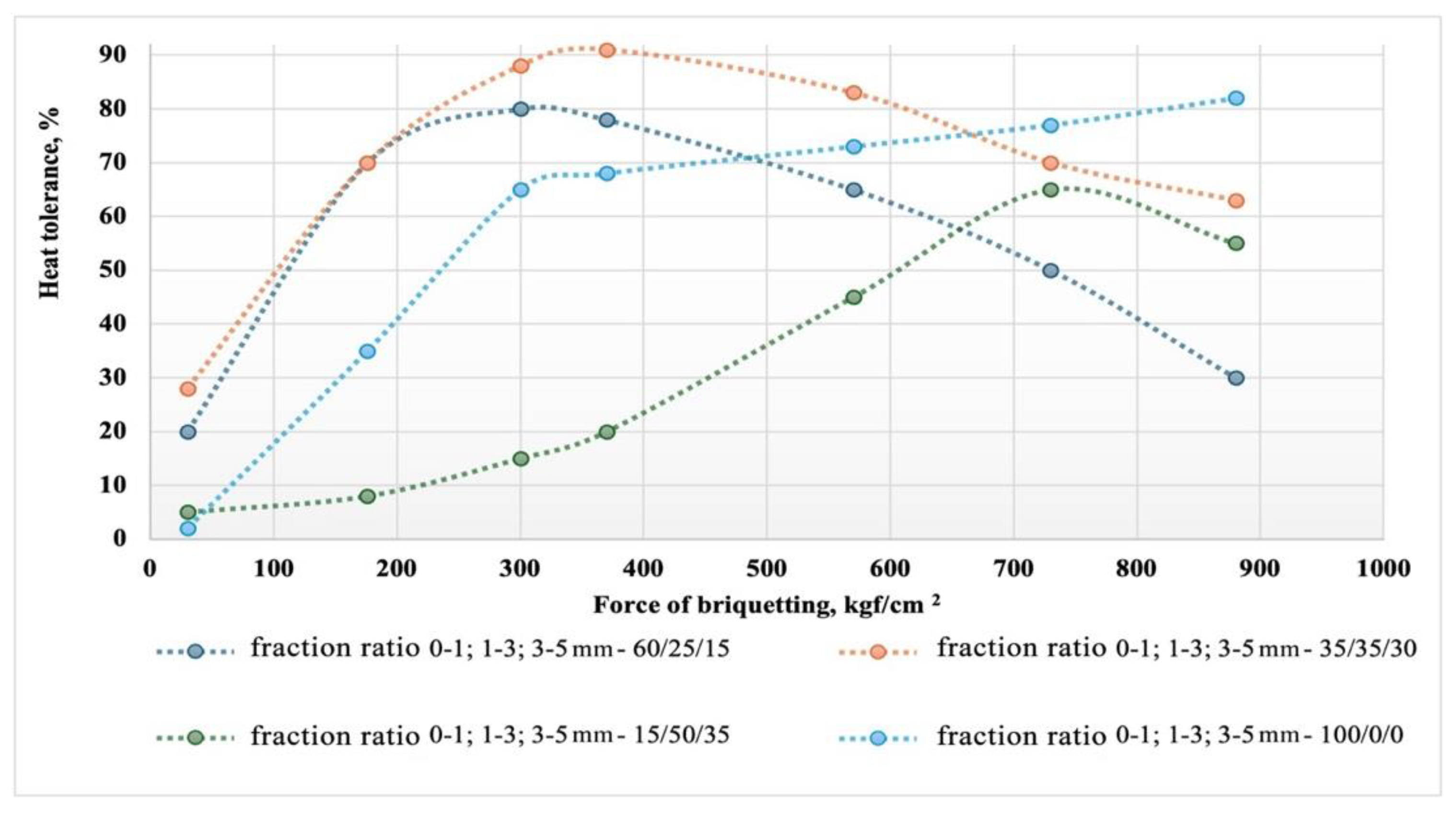

Figure 7 shows graphs of the dependence of the heat tolerance of briquettes for different types of granulometric composition of the composite briquetting charge.

The graph illustrates the impact of briquetting force and particle size distribution on the heat tolerance of briquettes made from a composite mixture of microsilica and carbon reducing agents. It was found that heat tolerance increases with the briquetting force up to a certain optimum, which varies depending on the particle size distribution. The optimal briquetting force for achieving maximum heat tolerance is in the range of 400 to 500 kgf/cm², with compositions that have a more balanced particle size distribution showing the most consistent results. Reducing the fine fraction content to 15% results in poorer briquetting conditions and necessitates an increase in pressure to 700-800 kgf/cm² to achieve optimal heat resistance, which is reduced to 60-65%. Further increasing the force (up to 900 kgf/cm²) leads to a decrease in heat tolerance for most compositions, indicating potential structural changes in the briquettes. To ensure optimal heat tolerance, it is recommended to use a briquetting pressure of approximately 370-400 kgf/cm² and a particle size distribution ratio of 0-1; 1-3; 3-5 mm in the proportion 35/35/30. However, briquettes with a high fine fraction content (0-1 mm) maintain or even improve their heat tolerance at maximum force, making them promising for use under conditions of high thermal load. These findings underscore the importance of selecting both the particle size distribution and briquetting force to optimize briquette properties in metallurgical silicon production.

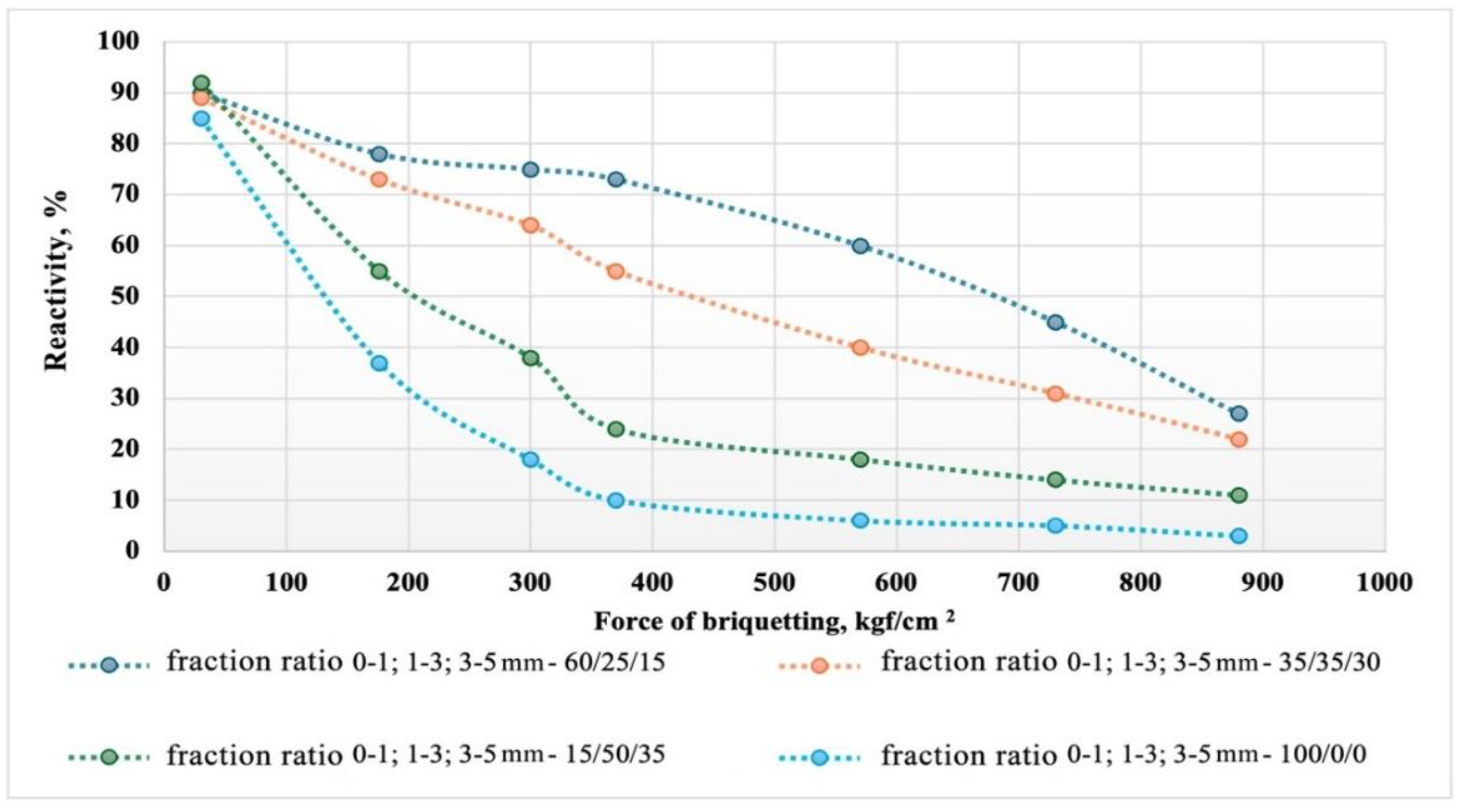

Figure 8 shows graphs of the dependence of the reactive activity of the briquettes on the briquetting pressure and the granulometric composition of the briquetting mix.

Obviously, for all studied variants of briquettes, with increasing briquetting force, the reactivity decreases. At the same time, there is a direct proportional dependence of the briquette's reactivity on the granulometric composition.

With an increase in the proportion of particles with sizes of 1-3 and 3-5 mm, the reactivity of the briquettes increases. This indirectly confirms the mechanism of the silicon reduction process through the gas phase involving silicon monoxide and silicon carbide. Despite the highly developed reactivity of the fine-dispersed component of the briquettes, increasing its share does not lead to an acceleration of the reduction. On the contrary, the over-compaction of the fine-dispersed phase leads to increased diffusion inhibition during the movement of silicon monoxide and carbon within the briquette. The presence of particles of different diameters in the briquette helps to improve the gas permeability of the reaction products layer due to the formation of macropores within the briquette during the gasification of carbon inclusions.

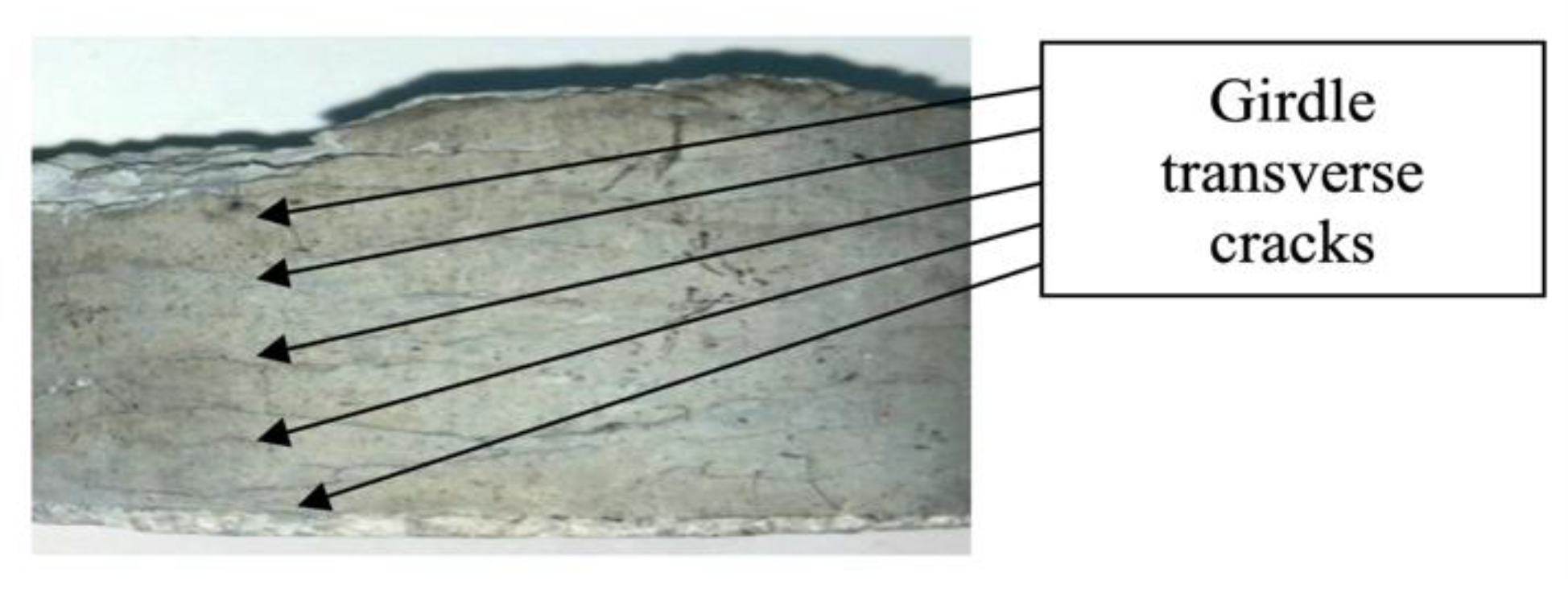

This type of briquette visually differs from briquettes made using other types of reducers, which allows it to be identified by external signs. Based on graph-analytical analysis, it was assumed that to achieve full heat tolerance of the briquette, the briquetting force should be 800-900 kgf/cm² (80-90 MPa), which corresponds to the literature data [

1,

2]. However, this did not happen. Briquetting at a pressure of 570 kgf/cm² led to significant delamination of the briquette and a decrease in heat tolerance to 65%. Delamination refers to cracks developing perpendicular to the force application vector during briquetting, encircling the briquette around its perimeter. The cracks are mainly surface-level, penetrating the briquette body to a depth of 1-3 mm as shown in

Figure 9.

However, there are cracks that penetrate through the entire body of the briquette, leading to transverse rupture either during the briquetting process with clogging of the working surface of the press, or to the rupture of the finished briquette when a slight force is applied in the corresponding direction. Thus, anisotropy of mechanical and thermomechanical properties is observed.

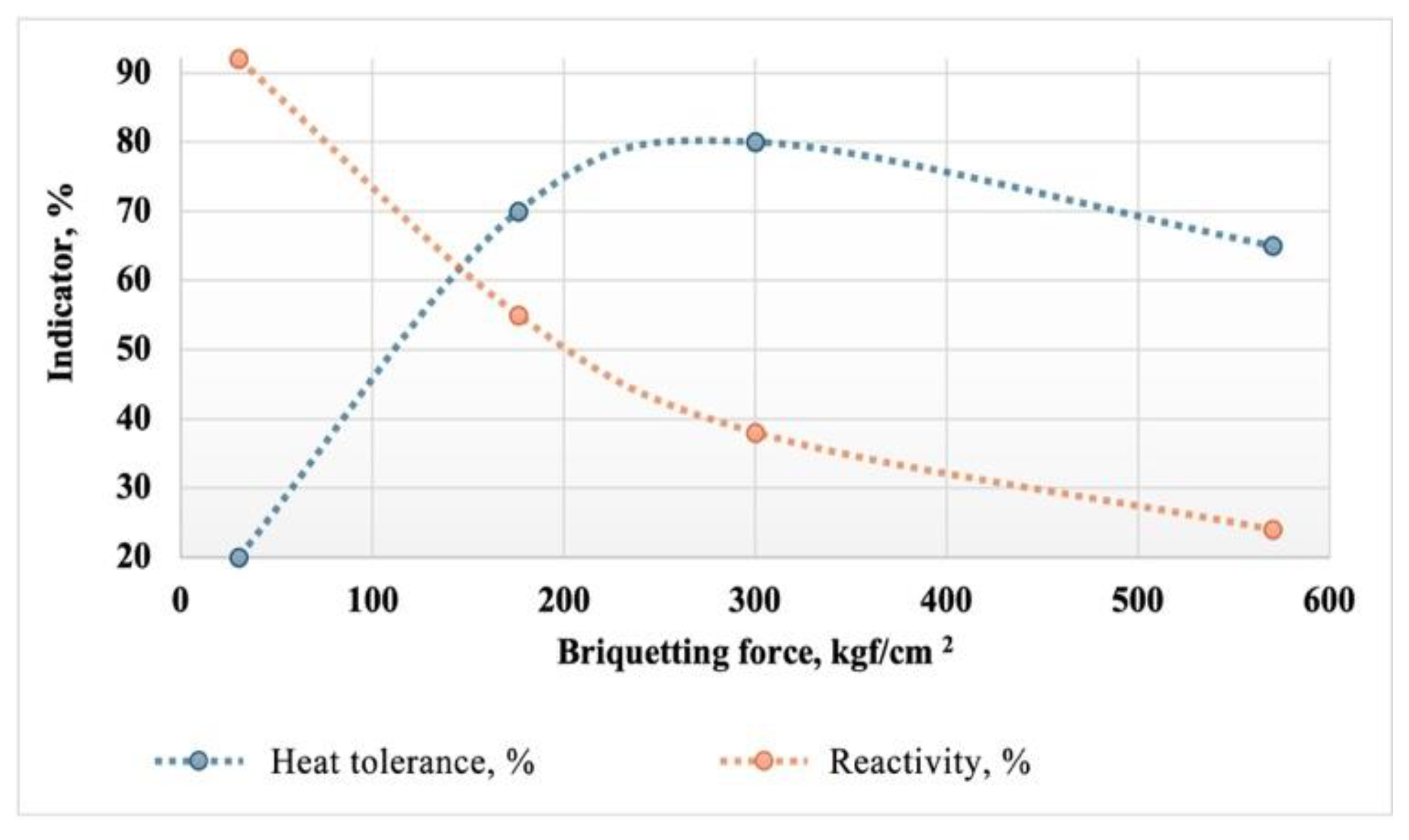

It has been established that heat tolerance depends on the specific pressing force and the granulometric composition of the charge. The dependence of the heat tolerance and reactivity of the briquettes on the briquetting force is shown in

Figure 10.

The graph shows that with increasing briquetting force, the heat tolerance of the briquettes goes through a maximum in the range of 250-350 kgf/cm². Simultaneously, with the increase in briquetting force, a decrease in the reactivity of the briquettes is observed. At the optimal force in terms of heat tolerance, the reactivity of the briquette is at critical values, around 40 %. To explore the possibility of increasing the reactivity in combination with high heat tolerance, experiments were conducted at lower briquetting forces but with a higher degree of variability in the granulometric composition. This assumption was based on the fact that polydisperse materials typically create a denser packing during briquetting without the presence of macropores within the briquette. Due to the naturally high packing density of the particles, on the one hand, the briquetting force required to ensure high heat tolerance and mechanical strength is reduced. On the other hand, the reduction in briquetting force ensures the presence of micropores, facilitating the removal of gaseous reaction products from the briquette body.

Next, batches of briquettes with the optimal raw material composition were tested as raw material for the production of metallurgical-grade silicon in a submerged arc furnace with a transformer power of 200 kVA (

Figure 11).

Silicon smelting began using a standard traditional charge mixture consisting of quartzite and reducing agents in the form of coal and charcoal, special coke, and the charge also additionally contains wood chips. The ratio of the presented components in the composition of the charge is presented in

Table 2.

Theoretically, the process of smelting metallurgical silicon can be described by the following reaction equation:

Where silica (SiO₂) is reduced by carbon to elemental silicon (Si) and silicon oxide (SiO) in the gaseous state:

The gaseous silicon oxide is then reduced to elemental silicon:

It is worth noting that silicon carbide (SiC) also forms in the high-temperature zone of the furnace:

Silicon carbide interacts with silicon oxide, leading to its decomposition and the formation of additional elemental silicon:

In these tests, a 30% replacement of the traditional charge mixture with briquettes was tested. The negative influence of the amorphous phase composition of microsilica on the process of smelting technical silicon has not been established. There was no shock destruction of briquettes under the influence of thermal and current loads on the fire pit. As a result, a batch of metallurgical silicon was obtained. The fracture of the silicon ingots (

Figure 12) had a steel-gray color with pronounced crystal plates. The structure of the alloy is dense, without shells and foreign inclusions.

The average chemical composition of silicon samples obtained as a result of testing is presented in

Table 3.

At the same time, the extraction of silicon into metal using a standard charge was 71%, and the extraction using a briquetted monocharge was 85%. The results of trial tests have proven the possibility of using briquetted monocharge as a raw material for the smelting of metallurgical grade silicon.

4. Conclusions

The article presents data on the optimization of the physicochemical properties of briquettes based on microsilica depends their composite charge. The studies showed that the granulometric composition of the charge mixture significantly affects the heat tolerance and reactivity. The most optimal composition was found to be 60% of the 0-1 mm fraction, 25% of the 1-3 mm fraction, and 15% of the 3-5 mm fraction.

The conducted tests proved the fundamental possibility of using composite briquettes, consisting of silicon production waste – microsilica and a carbon reducer, for the production of metallurgical-grade silicon. During the smelting of metallurgical silicon, it was possible to improve the smelting process through the use of composite briquettes.

The obtained data suggest the possible economic and technological feasibility of producing metallurgical-grade silicon using briquettes made from microsilica and a carbon reducer. To establish the economic and technological efficiency of using composite briquettes, a series of technological tests is necessary to fully replace the traditional charge mixture.

Thus, the presented technology will allow for the processing of both accumulated and newly formed volumes of silicon wastes (microsilica), resulting in highly liquid products. At the same time, the accumulated volumes of microsilica, which present a serious environmental problem, can be considered a reliable raw material base for the production of high-purity technical silicon.

The results showed that the briquettes maintained their integrity at high temperatures with minimal material loss, indicating excellent thermal and mechanical stability. These results highlight the potential of these briquettes for use in high-temperature metallurgical processes where heat tolerance and mechanical strength are critical. 6. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Alibek Baisanov and Yerbol Shabanov; Data curation, Aidana Baisanova, Azat Mussin and Zhanna Ibrakhimova; Formal analysis, Nina Vorobkalo and Zhanna Ibrakhimova; Investigation, Alibek Baisanov, Nina Vorobkalo, Nikolay Zobnin, Aidana Baisanova, Symbat Sharieva, Azat Mussin and Temirlan Zhumagaliev; Methodology, Alibek Baisanov, Nikolay Zobnin and Temirlan Zhumagaliev; Project administration, Alibek Baisanov; Visualization, Azat Mussin; Writing – original draft, Nina Vorobkalo; Writing – review & editing, Yerbol Shabanov, Nikolay Zobnin and Symbat Sharieva. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP 14870218).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Zobnin, N.N.; Torgovets, A.K.; Pikalova, I.A.; Yussupova, Y.S.; Atakishiyev, S.A. Influence of Thermal Stability of Quartz and the Particle Size Distribution of Burden Materials on the Process of Electrothermal Smelting of Metallurgical Silicon. Orient J. Chem. 2018, 34, 2. [CrossRef]

- Zobnin, N.; Korobko, S.; Vetkovsky, D.; Moiseev, A.; Aganin, A.; Nurumgaliev, A.; Pikalova, I. Improving the Quality of Silicon Metal by the Method of X-ray Radiometric Separation of Raw Material and Finished Products. Proc. Irkutsk State Tech. Univ. 2020, 24, 1137–1149. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Geological Survey. Mineral Commodity Summaries 2024; U.S. Geological Survey: 2024; 212 p. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Geological Survey. Mineral Commodity Summaries 2023; U.S. Geological Survey: 2023; 210 p. [CrossRef]

- Galevsky, G.V.; Rudneva, V.V.; Galevsky, S.G. Microsilica in the Production of Silicon Carbide: The Results of Testing and Evaluation of Technological Challenges. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 411, 012018. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Kumar, B. A Comprehensive Investigation on Application of Microsilica and Rice Straw Ash in Rigid Pavement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 252, 119027.

- Al-Shugaa, M.A.; Rahman, M.K.; Baluch, M.H.; Al-Gadhib, A.H.; Sadoon, A.A.; Al-Osta, M.A. Performance of Hollow Concrete Block Masonry Walls Retrofitted with Steel-Fiber and Microsilica Admixed Plaster. Struct. Concr. 2019, 20, 236–251. [CrossRef]

- Gu, G.; Song, H. Microsilica and Waste Glass Powder as Partial Replacement of Portland Cement: Electrochemical Study on the Corrosion Performance of Steel Rebar in the Blended Concrete. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2020, 15, 12291–12301. [CrossRef]

- Ghafor, K.; Mahmood, W.; Qadir, W.; Mohammed, A. Effect of Particle Size Distribution of Sand on Mechanical Properties of Cement Mortar Modified with Microsilica. ACI Mater. J. 2020, 117, 47–60. [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Sang, S.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L. Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of Al₂O₃-ZrO₂-C Refractories Using Silicon, Microsilica, or Their Combination as Additive. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 545, 148–154. [CrossRef]

- Kosciuszko, A.; Czyzewski, P.; Wajer, L.; Osciak, A.; Bielinski, M. Properties of Polypropylene Composites Filled with Microsilica Waste. Polimery 2020, 65, 99–104. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, T.; Liu, X. Amorphous Silica: Prepared by Byproduct Microsilica in the Ferrosilicon Production and Applied in Amorphous Silica-TiO₂ Composite with Favorable Pigment Properties. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 26, 235–245. [CrossRef]

- Alnahhal, M.; Kim, T.; Hajimohammadi, A. Waste-Derived Activators for Alkali-Activated Materials: A Review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 118, 103980. [CrossRef]

- Siddique, R.; Chahal, N. Use of Silicon and Ferrosilicon Industry By-Products (Silica Fume) in Cement Paste and Mortar. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 739–744. [CrossRef]

- Baisanov, A.S.; Vorobkalo, N.R.; Makhambetov, YeN.; Mynzhasar, YeA.; Zulfiadi, Z. Studies of the Thermal Stability of Briquettes Based on Microsilica. Kompl. Ispolz. Miner. Syra 2023, 327, 57–63. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).