Submitted:

12 October 2024

Posted:

15 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. A Different Kind of Evolutionary Transition

2. Tissues and Organs

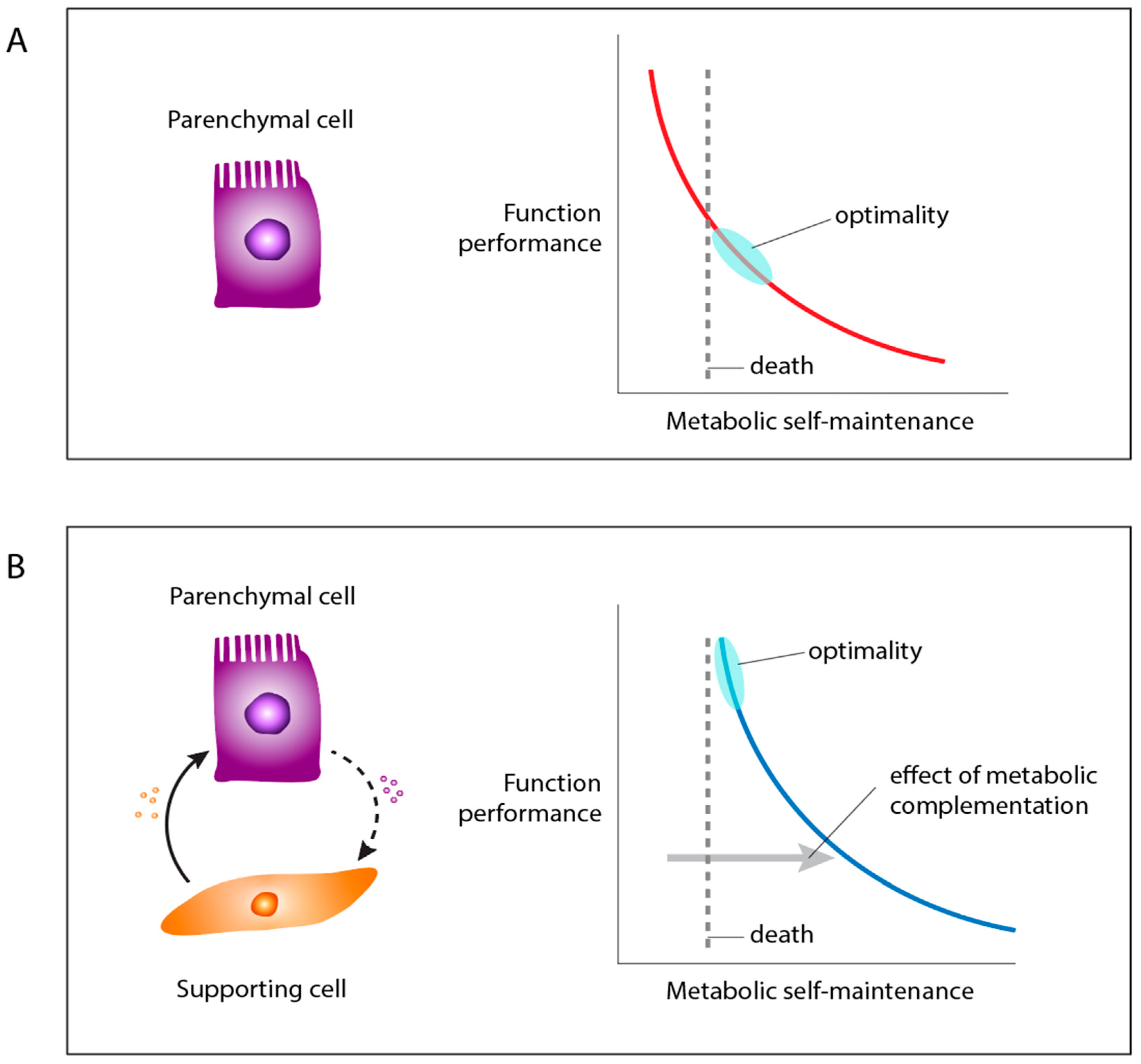

2.1. Metabolic Constraints

2.2. Metabolic Complementation

3. A hypothesis for the Origin of Tissues and Organs

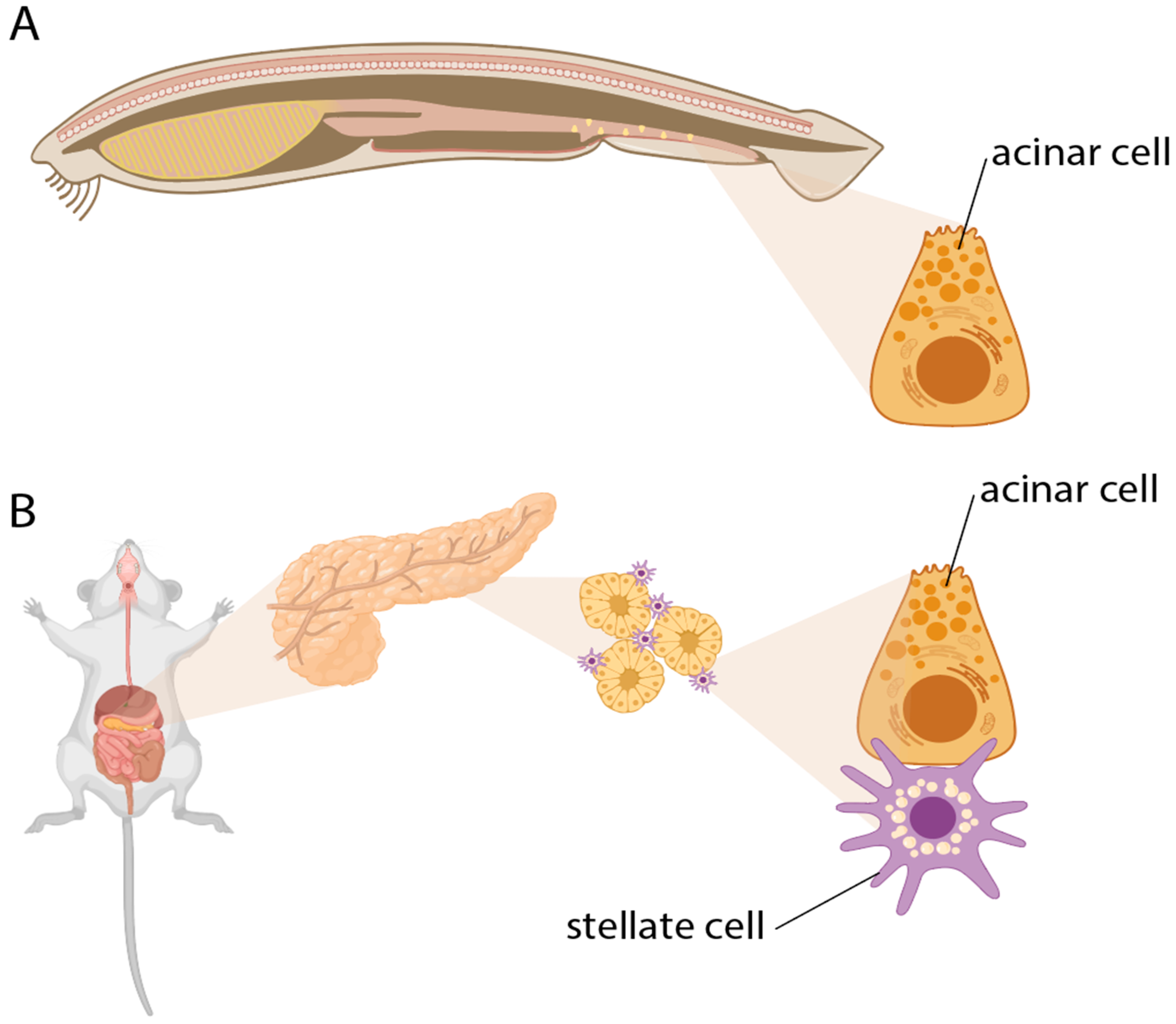

3.1. Examples of Tissue-Sustaining Metabolic Interactions

3.2. Why Was Metabolism Overlooked in Evolutionary Biology?

3.3. Implications of the Hypothesis

4. Discussion: On the Origins of Within-Organism Levels of Organization

Acknowledgements and funding

References

- Durrant, S.D.; Simpson, G.G. The Major Features of Evolution. J. Mammal. 1954, 35, 600–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, E. 1960. The Emergence of Evolutionary Novelties. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Chavan, A.R.; Griffith, O.W.; Stadtmauer, D.J.; Maziarz, J.; Pavlicev, M.; Fishman, R.; Koren, L.; Romero, R.; Wagner, G.P. Evolution of Embryo Implantation Was Enabled by the Origin of Decidual Stromal Cells in Eutherian Mammals. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 1060–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMIGUEL, D.; Azanza, B.; Morales, J. Key innovations in ruminant evolution: a paleontological perspective. Integr. Zoöl. 2013, 9, 412–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronco, F.; Salzburger, W. Tracing evolutionary decoupling of oral and pharyngeal jaws in cichlid fishes. Evol. Lett. 2021, 5, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leake, LD. 1975. Comparative Histology. An introduction to the Microscopic Structure of Animals. New York: Academic Press.

- Falkmer, S. 1985. Comparative morphology of pancreatic islets in animals. In Volk BW, Arquille ER, eds; The diabetic Pancreas. New York: Plenum medical Book coMPANY.

- Falkmer, S.; Dafgård, E.; El-Salhy, M.; Engström, W.; Grimelius, L.; Zetterberg, A. Phylogenetical aspects on islet hormone families: A minireview with particular reference to insulin as a growth factor and to the phylogeny of PYY and NPY immunoreactive cells and nerves in the endocrine and exocrine pancreas. Peptides 1985, 6, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlosser, G. 2021. Origin of Sensory and Neurosecretory Cell Types: Vertebrate Cranial Placodes: CRC Press.

- Adler, M.; Moriel, N.; Goeva, A.; Avraham-Davidi, I.; Mages, S.; Adams, T.S.; Kaminski, N.; Macosko, E.Z.; Regev, A.; Medzhitov, R.; et al. Emergence of division of labor in tissues through cell interactions and spatial cues. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, M.; Chavan, A.R.; Medzhitov, R. Tissue Biology: In Search of a New Paradigm. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 39, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Franklin, R.A.; Adler, M.; Jacox, J.B.; Bailis, W.; Shyer, J.A.; Flavell, R.A.; Mayo, A.; Alon, U.; Medzhitov, R. Circuit Design Features of a Stable Two-Cell System. Cell 2018, 172, 744–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, BK. 1988. The embryonic development of bone. American Scientist 76: 174-81.

- DiFrisco, J.; Love, A.C.; Wagner, G.P. Character identity mechanisms: a conceptual model for comparative-mechanistic biology. Biol. Philos. 2020, 35, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiße, A.Y.; Oyarzún, D.A.; Danos, V.; Swain, P.S. Mechanistic links between cellular trade-offs, gene expression, and growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, E1038–E1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenaar D, van Berlo R, de Ridder D, Teusink B. 2009. Shifts in growth strategies reflect tradeoffs in cellular economics. Mol Syst Biol 5: 323.

- Kempes CP, Dutkiewicz S, Follows MJ. 2012. Growth, metabolic partitioning, and the size of microorganisms.Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: 495-500.

- Gladden, L.B. Lactate metabolism: a new paradigm for the third millennium. J. Physiol. 2004, 558, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, G.A. Cell–cell and intracellular lactate shuttles. J. Physiol. 2009, 587, 5591–5600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.C. Regulation of glutathione synthesis. Mol. Asp. Med. 2008, 30, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLong, J.P.; Okie, J.G.; Moses, M.E.; Sibly, R.M.; Brown, J.H. Shifts in metabolic scaling, production, and efficiency across major evolutionary transitions of life. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107, 12941–12945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlicev M, Wagner GP. 2024. Reading the palimpsest of cell interactions: What questions may we ask of the data? iScience 27: 109670.

- Force, A.; Lynch, M.; Pickett, F.B.; Amores, A.; Yan, Y.-L.; Postlethwait, J. Preservation of Duplicate Genes by Complementary, Degenerative Mutations. Genetics 1999, 151, 1531–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad Kourki, A. 2022. The evolution of complex multicellularity in animals. Biology & Philosophy 37: 43.

- Parker, J. Organ Evolution: Emergence of Multicellular Function. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 40, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, D. The evolution of cell types in animals: emerging principles from molecular studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008, 9, 868–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, A.C.; Wagner, G.P. Co-option of stress mechanisms in the origin of evolutionary novelties. Evolution 2021, 76, 394–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns-Smith, A. 1995. The Complexity ratchet. In Shostak G, ed; Progress in Search for Extraterrestrial Life. San Francisco.: Astronomical Society of the Pacific. p 31-6.

- Liard, V.; Parsons, D.P.; Rouzaud-Cornabas, J.; Beslon, G. The Complexity Ratchet: Stronger than Selection, Stronger than Evolvability, Weaker than Robustness. Artif. Life 2020, 26, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukeš, J.; Archibald, J.M.; Keeling, P.J.; Doolittle, W.F.; Gray, M.W. How a neutral evolutionary ratchet can build cellular complexity. IUBMB Life 2011, 63, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, H. 1960. Direct metabolic interactions between animal cells. Their role in tissue function and development is reconsidered. Science 132: 529-32.

- Gasbarrini, A.; Borle, A.; Farghali, H.; Bender, C.; Francavilla, A.; Van Thiel, D. Effect of anoxia on intracellular ATP, Na+i, Ca2+i, Mg2+i, and cytotoxicity in rat hepatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 6654–6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brezis, M.; Epstein, F.H. Cellular Mechanisms of Acute Ischemic Injury in the Kidney. Annu. Rev. Med. 1993, 44, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbons, H.M.; Dragunow, M. Adult human brain cell culture for neuroscience research. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010, 42, 844–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.A.; Adamson, D.C. Neuronal-Astrocyte Metabolic Interactions: Understanding the Transition Into Abnormal Astrocytoma Metabolism. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2011, 70, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.; Jimenez-Blasco, D.; Bolaños, J.P. Cross-talk between energy and redox metabolism in astrocyte-neuron functional cooperation. Essays Biochem. 2023, 67, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolaños, J.P. Bioenergetics and redox adaptations of astrocytes to neuronal activity. J. Neurochem. 2016, 139, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonvento, G.; Bolaños, J.P. Astrocyte-neuron metabolic cooperation shapes brain activity. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 1546–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kastriti, M.E.; Adameyko, I. Specification, plasticity and evolutionary origin of peripheral glial cells. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2017, 47, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rey, S.; Zalc, B.; Klämbt, C. Evolution of glial wrapping: A new hypothesis. Dev. Neurobiol. 2021, 81, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Song, B.; Lee, I.-S. Drosophila Glia: Models for Human Neurodevelopmental and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Venrooij, W.J.; Henshaw, E.C.; Hirsch, C.A. Effects of deprival of glucose or individual amino acids on polyribosome distribution and rate of protein synthesis in cultured mammalian cells. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Nucleic Acids Protein Synth. 1972, 259, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, G.; Peran, S. Basolateral amino acid transport systems in the perfused exocrine pancreas: sodium-dependency and kinetic interactions between influx and efflux mechanisms. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Biomembr. 1986, 858, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosowski, H.; Schild, L.; Kunz, D.; Halangk, W. Energy metabolism in rat pancreatic acinar cells during anoxia and reoxygenation. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Bioenerg. 1998, 1367, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, S.; Matsumoto, R.; Masamune, A. Pancreatic Stellate Cells and Metabolic Alteration: Physiology and Pathophysiology. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 865105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bläuer, M.; Nordback, I.; Sand, J.; Laukkarinen, J. A novel explant outgrowth culture model for mouse pancreatic acinar cells with long-term maintenance of secretory phenotype. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 90, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, O.H. The 2022 George E Palade Medal Lecture: Toxic Ca2+ signals in acinar, stellate and endogenous immune cells are important drivers of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2022, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criddle DN, Tepkin AV. 2020. Bioenergetics of the Exocrine Pancreas: Physiology to Pathophysiology. Pancreapedia: Exocrine Pancreas knowledge base.

- Pan, Z.; Bossche, J.-L.V.D.; Rodriguez-Aznar, E.; Janssen, P.; Lara, O.; Ates, G.; Massie, A.; De Paep, D.L.; Houbracken, I.; Mambretti, M.; et al. Pancreatic acinar cell fate relies on system xC- to prevent ferroptosis during stress. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Phillips, P.; A McCarroll, J.; Wu, M.-J.; Pirola, R.; Korsten, M.; Wilson, J.S.; Apte, M.V. Rat pancreatic stellate cells secrete matrix metalloproteinases: implications for extracellular matrix turnover. Gut 2003, 52, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riopel, M.M.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; Leask, A.; Wang, R. β1 integrin–extracellular matrix interactions are essential for maintaining exocrine pancreas architecture and function. Mod. Pathol. 2013, 93, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P.A.; Yang, L.; Shulkes, A.; Vonlaufen, A.; Poljak, A.; Bustamante, S.; Warren, A.; Xu, Z.; Guilhaus, M.; Pirola, R.; et al. Pancreatic stellate cells produce acetylcholine and may play a role in pancreatic exocrine secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107, 17397–17402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.S.; Cui, Z.J. Pancreatic Stellate Cells Serve as a Brake Mechanism on Pancreatic Acinar Cell Calcium Signaling Modulated by Methionine Sulfoxide Reductase Expression. Cells 2019, 8, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaziri-Gohar, A.; Zarei, M.; Brody, J.R.; Winter, J.M. Metabolic Dependencies in Pancreatic Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa CM, Biancur DE, Wang X, Halbrook CJ, et al. 2016. Pancreatic stellate cells support tumor metabolism through autophagic alanine secretion. Nature 536: 479-83.

- Wu, B.; Xu, W.; Wu, K.; Li, Y.; Hu, M.; Feng, C.; Zhu, C.; Zheng, J.; Cui, X.; Li, J.; et al. Single-cell analysis of the amphioxus hepatic caecum and vertebrate liver reveals genetic mechanisms of vertebrate liver evolution. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 1972–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejci, A.; Tennessen, J.M. Metabolism in time and space – exploring the frontier of developmental biology. Development 2017, 144, 3193–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juliano, C.E. Metabolites play an underappreciated role in development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.J. Amino acid auxotrophy as a system of immunological control nodes. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganeshan, K.; Chawla, A. Metabolic Regulation of Immune Responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 32, 609–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H. Immunometabolism at the intersection of metabolic signaling, cell fate, and systems immunology. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2022, 19, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Xiong, X.; Danska, J.; Parkinson, J. Metatranscriptomic analysis of diverse microbial communities reveals core metabolic pathways and microbiome-specific functionality. Microbiome 2016, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiani, C.; Maspero, D.; Di Filippo, M.; Colombo, R.; Pescini, D.; Graudenzi, A.; Westerhoff, H.V.; Alberghina, L.; Vanoni, M.; Mauri, G. Integration of single-cell RNA-seq data into population models to characterize cancer metabolism. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2019, 15, e1006733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, N.; Chang, W.; Dang, P.; Lu, X.; Wan, C.; Gampala, S.; Huang, Z.; Wang, J.; Ma, Q.; Zang, Y.; et al. A graph neural network model to estimate cell-wise metabolic flux using single-cell RNA-seq data. Genome Res. 2021, 31, 1867–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Z.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, K.; Yuan, J. Metabolic reprogramming and heterogeneity during the decidualization process of endometrial stromal cells. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maynard Smith J, Szathmary E. 1995. The Major Transitions in Evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McShea, DW. 1996. Perspective metazoan complexity and evolution: is there a trend? Evolution 50: 477-92.

- Michod, R. 2000. Darwinian Dynamics: evolutionary transitions in fitness and individuality. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Michod, R.E. Evolution of individuality during the transition from unicellular to multicellular life. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007, 104, 8613–8618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okasha, S. 2006. Evolution and the levels of selection Oxford; New York: Clarendon Press ; Oxford University Press.

- West, S.A.; Fisher, R.M.; Gardner, A.; Kiers, E.T. Major evolutionary transitions in individuality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, 10112–10119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buss, LW. 1987. The Evolution of Individuality: Princeton University Press.

- Brunet, T.; King, N. The Origin of Animal Multicellularity and Cell Differentiation. Dev. Cell 2017, 43, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herron M, Conlin P, Ratcliff W. 2021. The Evolution of Multicellularity. 1.

- Niklas KJ, Newman S. 2016. Multicellularity : origins and evolution Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Wagner, GP. 2014. Homology, Genes and Evolutionary Innovation Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- McShea D, Venit EP. 2001. What is a part? In Wagner GP, ed; The Character Concept in Evolutionary Biology. San Diego: Academic Press.

- Wagner, G.P.; Altenberg, L. Perspective: Complex Adaptations and the Evolution of Evolvability. Evolution 1996, 50, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raff, RA. 1996. The shape of life : genes, development, and the evolution of animal form Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Wagner GP, Pavlicev M, Cheverud JM. 2007. The road to modularity. Nat Rev Genet 8: 921-31.

- Dighe, A.; Maziarz, J.; Ibrahim-Hashim, A.; Gatenby, R.A.; Kshitiz; Levchenko, A. ; Wagner, G.P. Experimental and phylogenetic evidence for correlated gene expression evolution in endometrial and skin fibroblasts. iScience 2023, 27, 108593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlicev, M.; Wagner, G.P. A model of developmental evolution: selection, pleiotropy and compensation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2012, 27, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilets, S. Rapid Transition towards the Division of Labor via Evolution of Developmental Plasticity. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2010, 6, e1000805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueffler, C.; Hermisson, J.; Wagner, G.P. Evolution of functional specialization and division of labor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, E326–E335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).