Submitted:

16 August 2024

Posted:

20 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

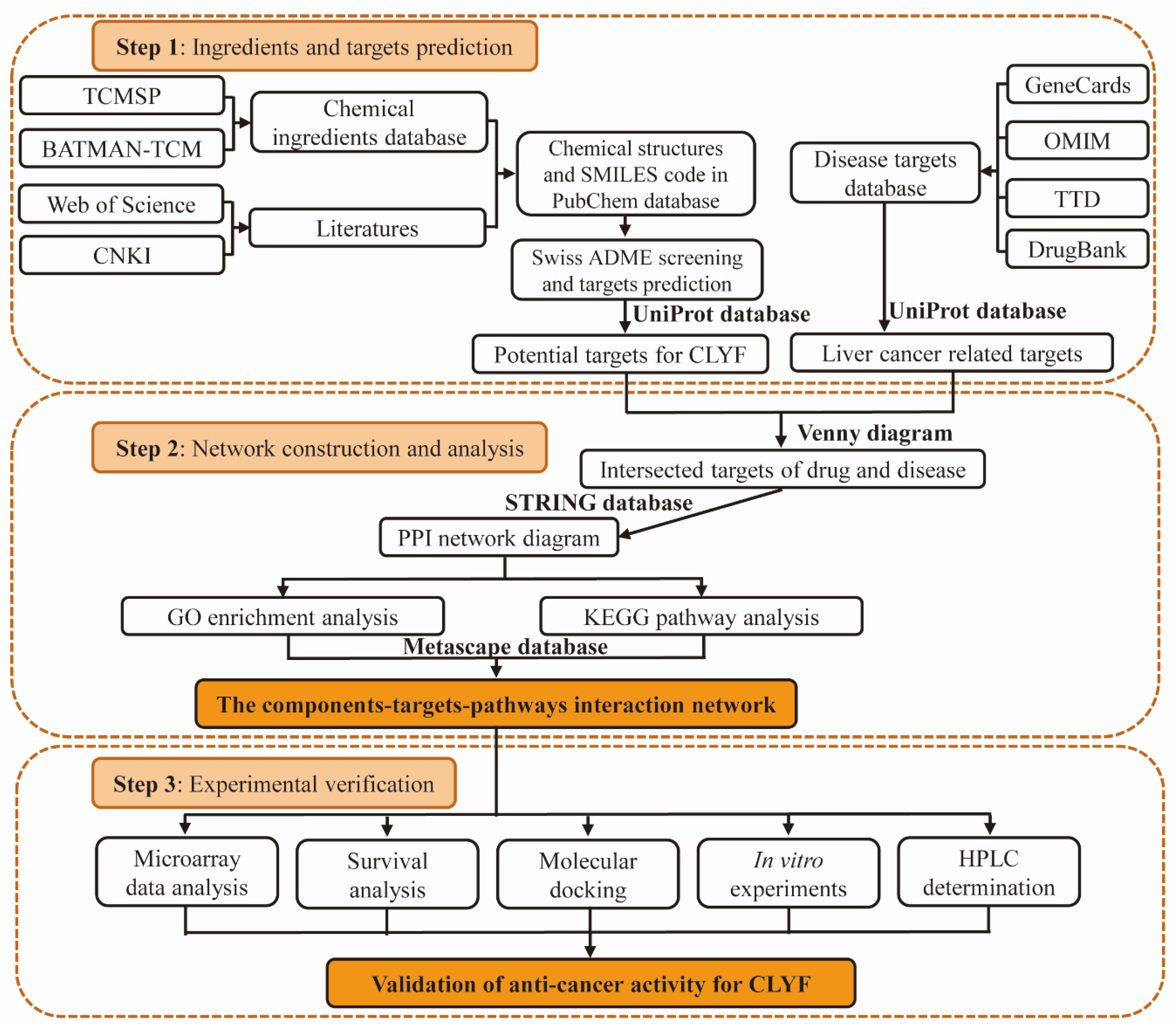

2. Results

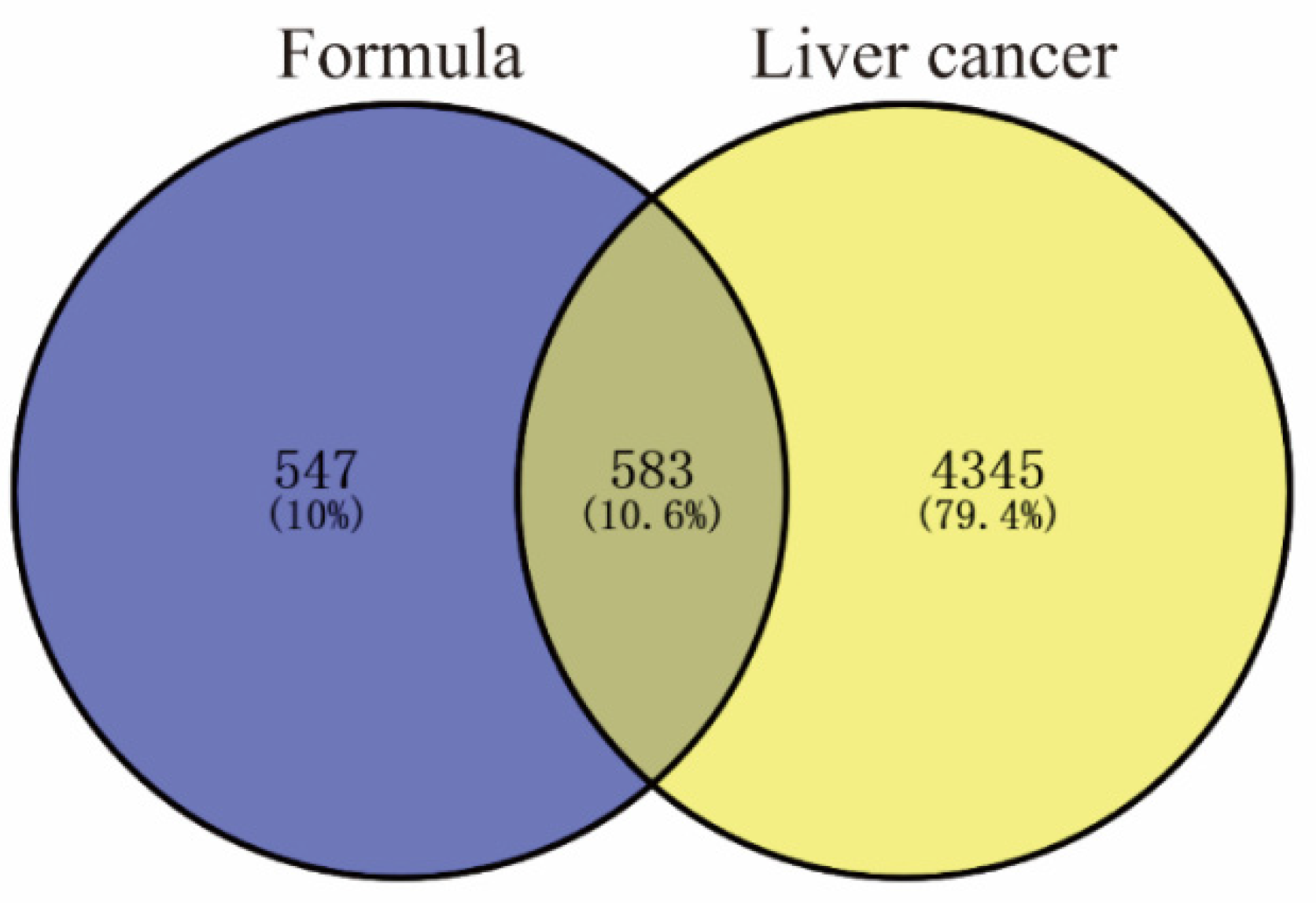

2.1. Screening for the Active Ingredients in CLYF and Their Therapeutic Targets

2.2. Targets for Liver Cancer

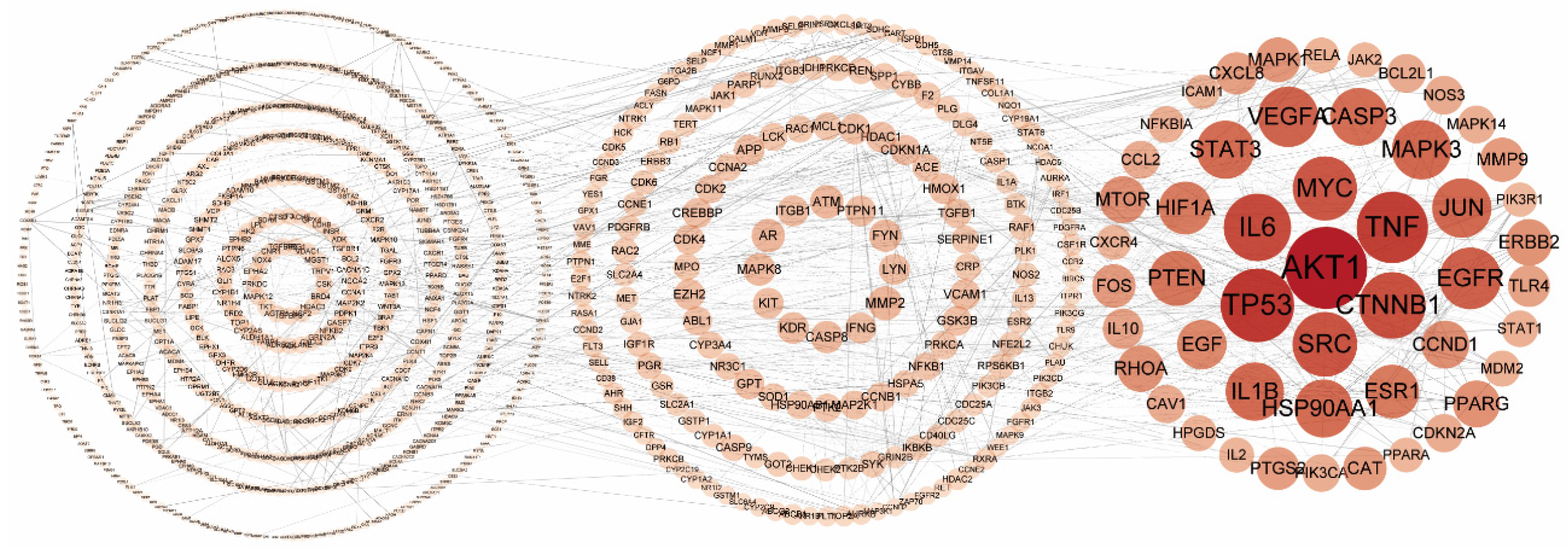

2.3. Protein–Protein Interaction Network of the Putative Therapeutic Targets of CLYF for Treating Liver Cancer

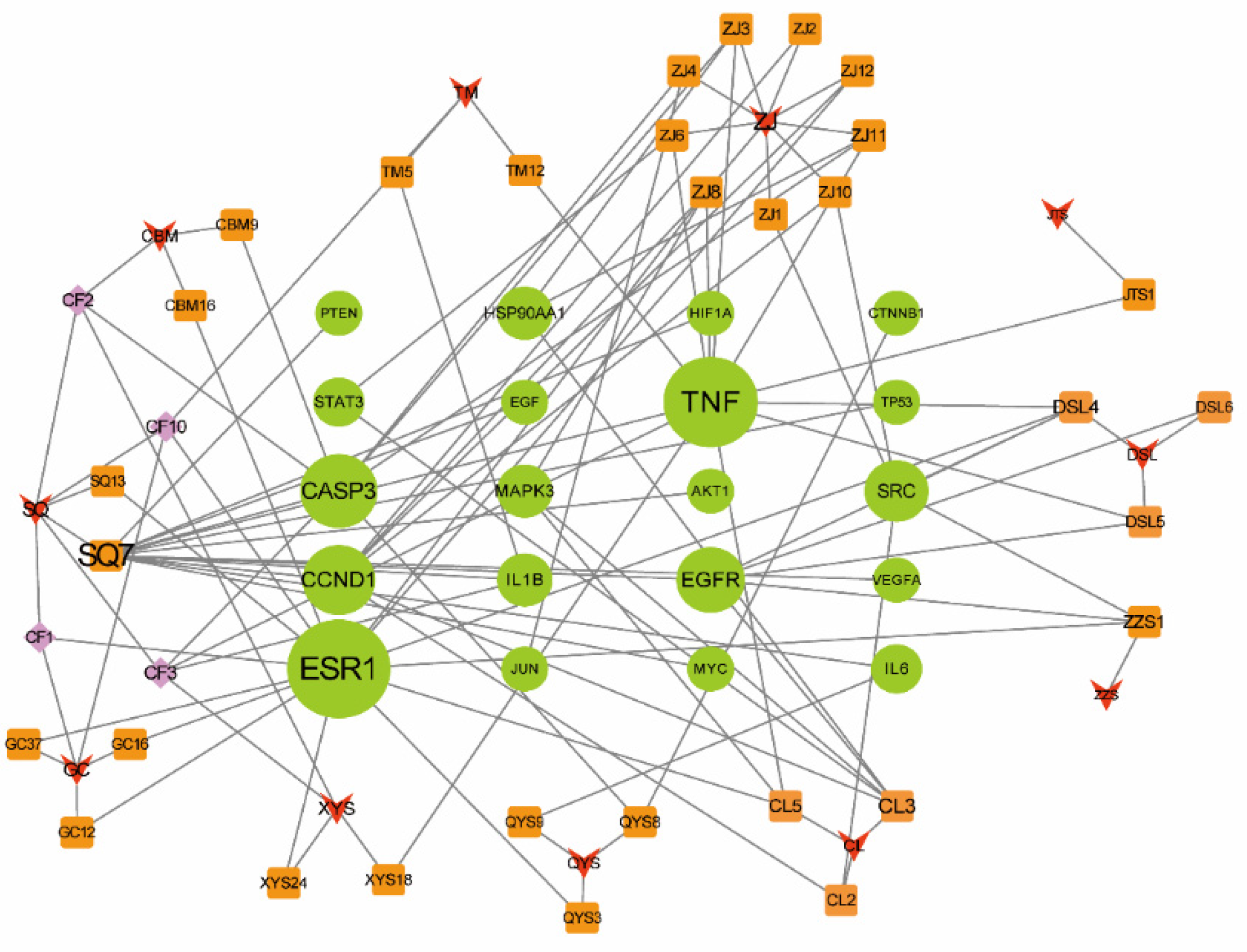

2.4. Determining the Main Active Compounds of CLYF against Liver Cancer through Target–Pathway Network Analysis

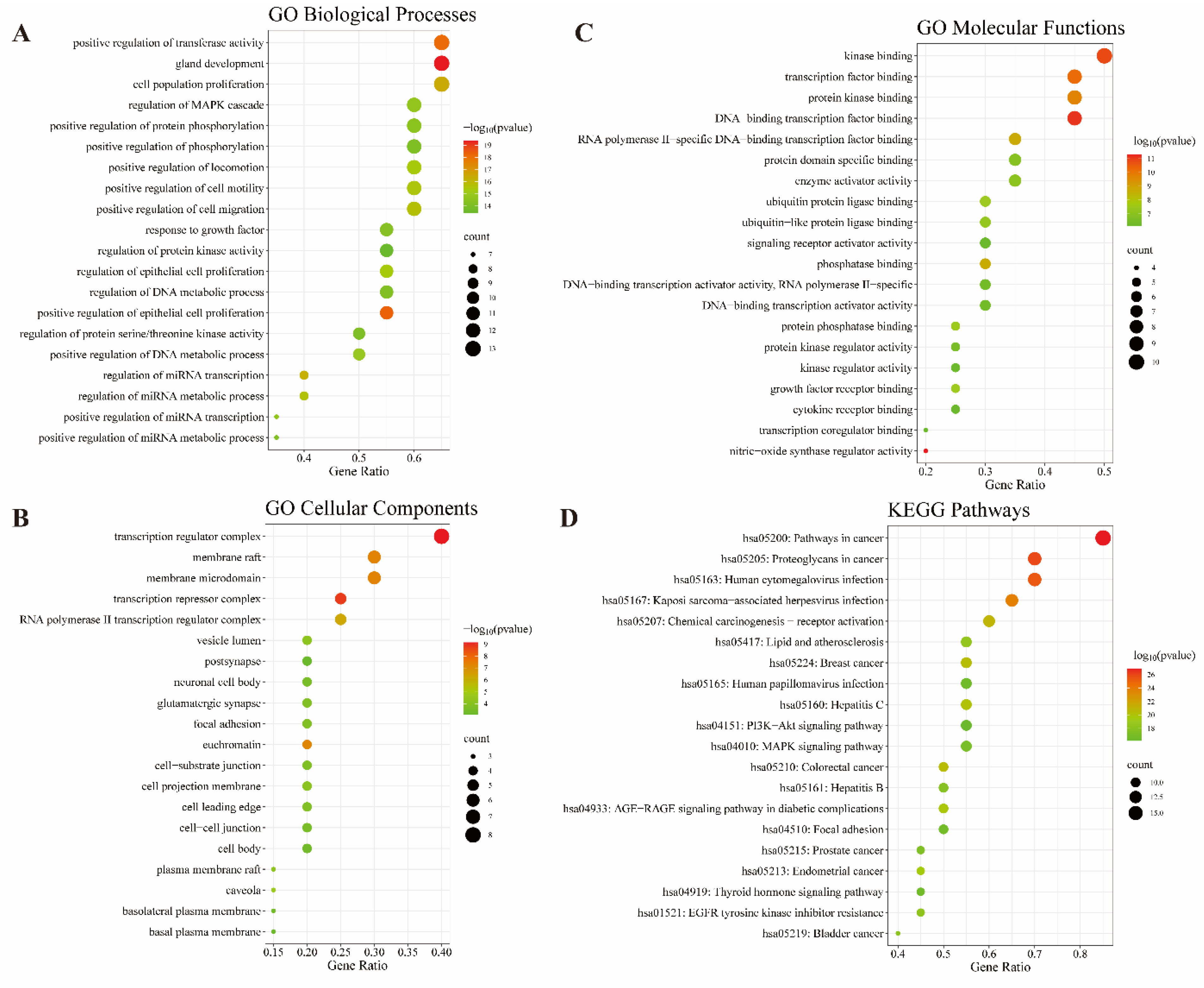

2.5. GO and KEGG Enrichment Analyses Identifies Key Signaling Pathways in Treatment of Liver Cancer by CLYF

2.6. Network Pharmacology Analysis through Generating a Compound–Therapeutic Target–pathway Interaction Network

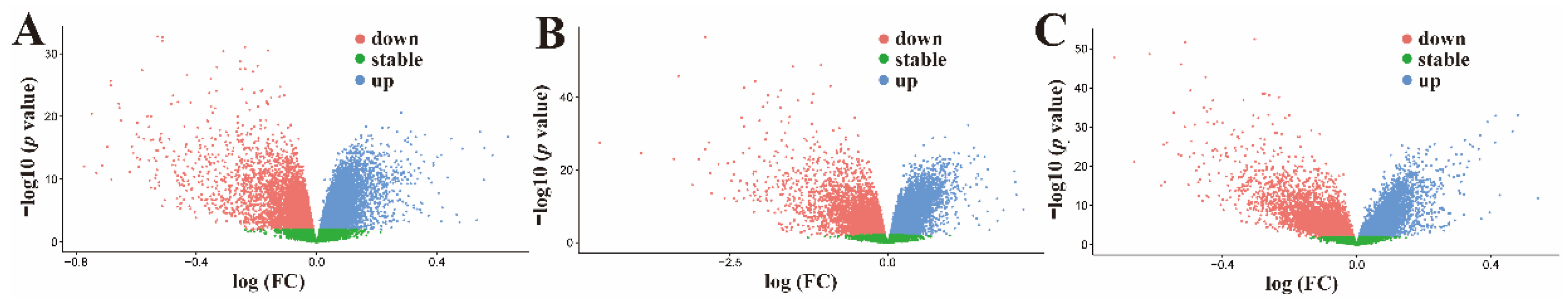

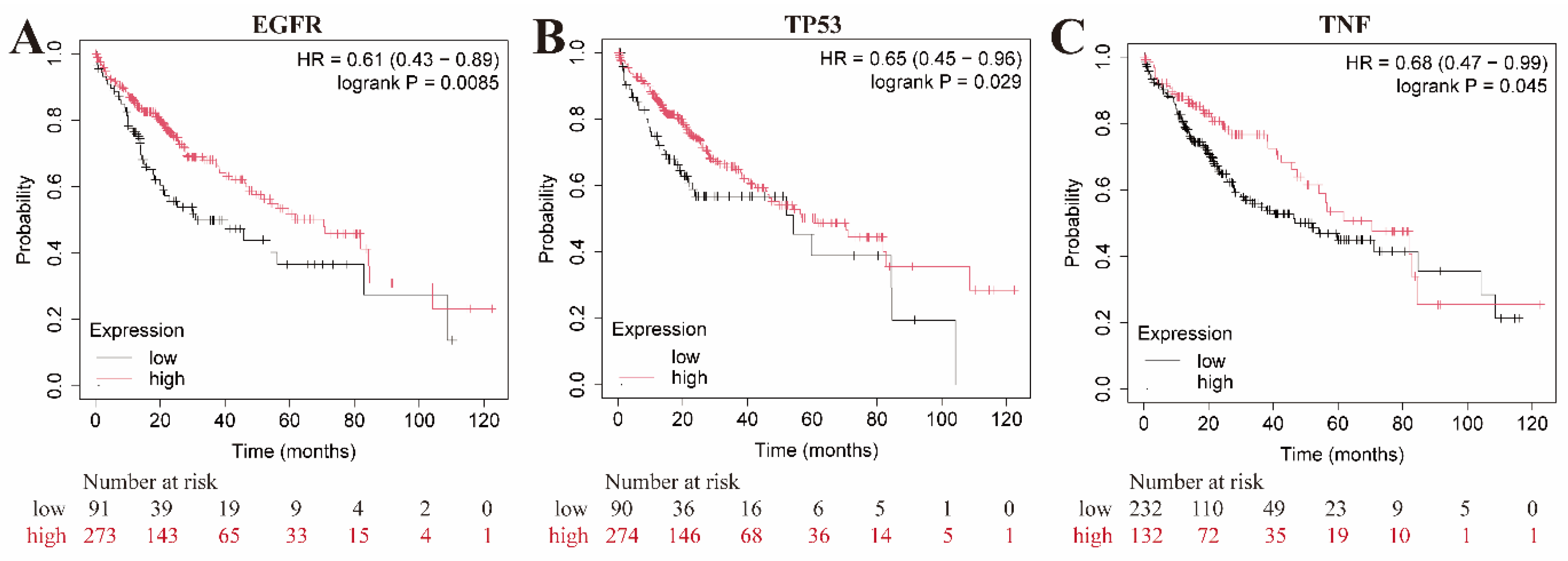

2.7. Microarray data analysis and survival analysis

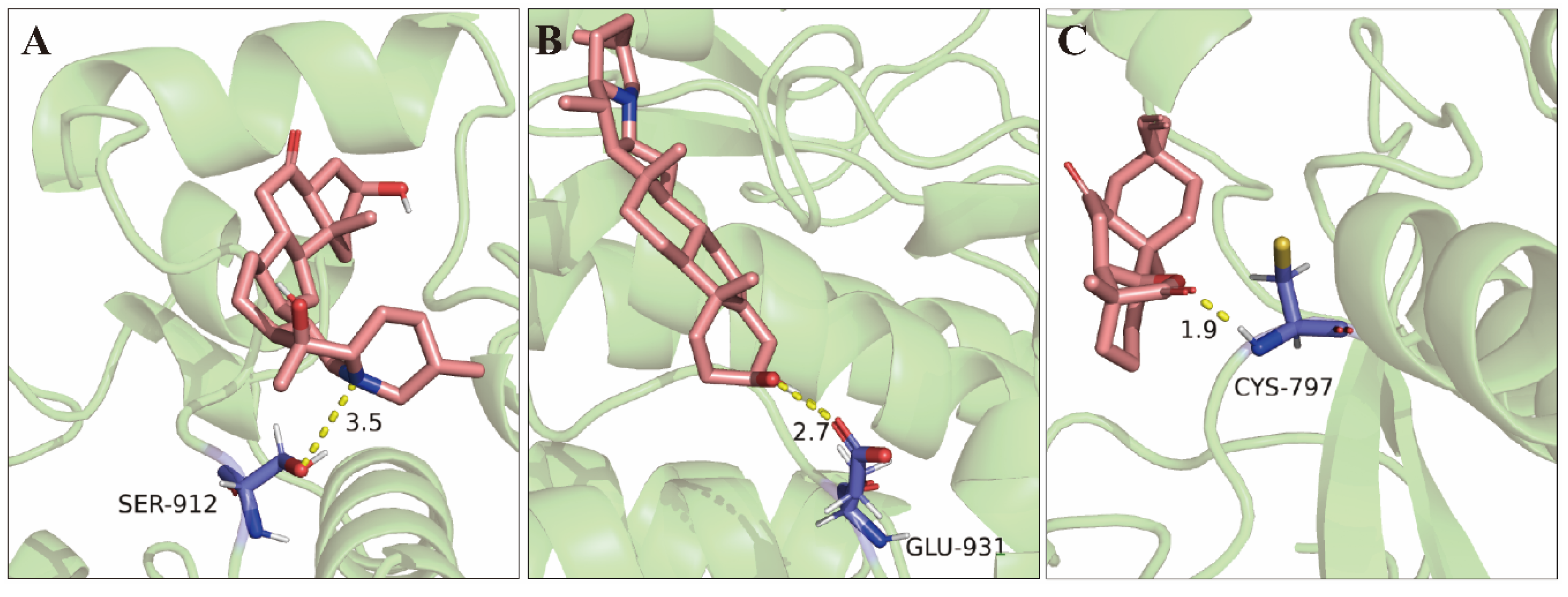

2.8. Molecular Docking Validation of Key Targets with Active Compounds

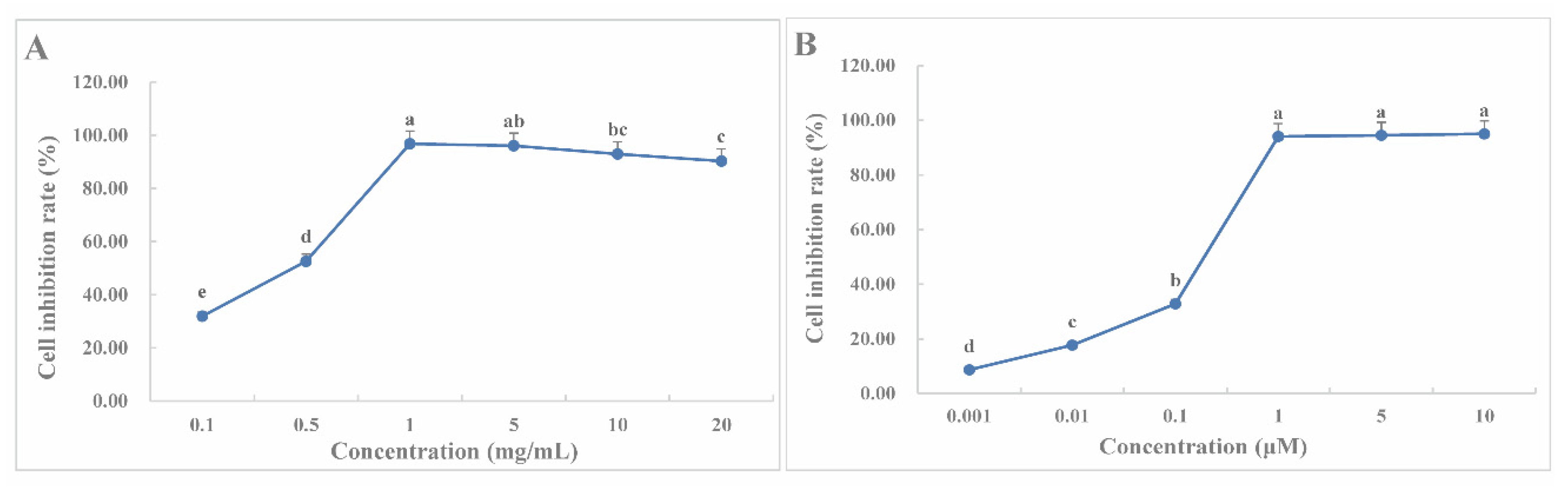

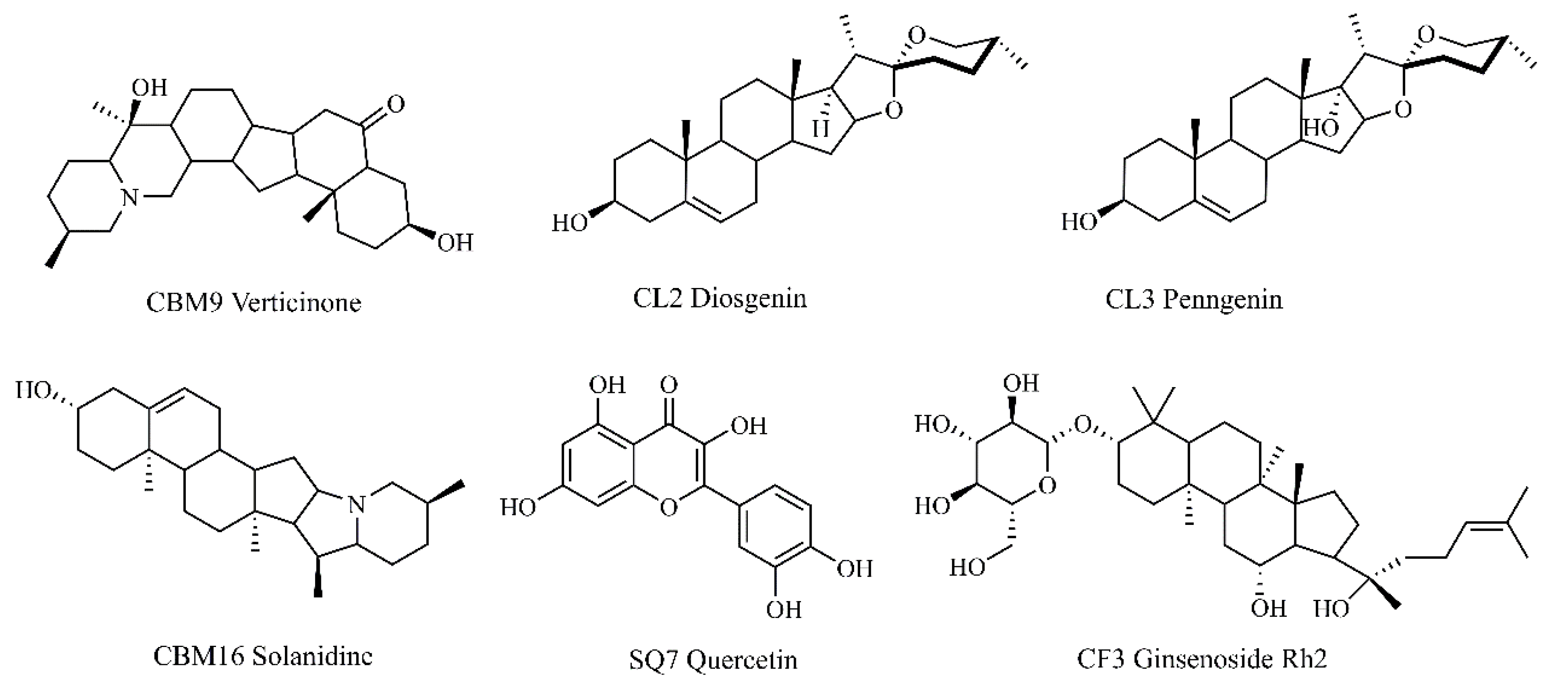

2.9. CLYF Inhibits the Proliferation of HepG2 cells

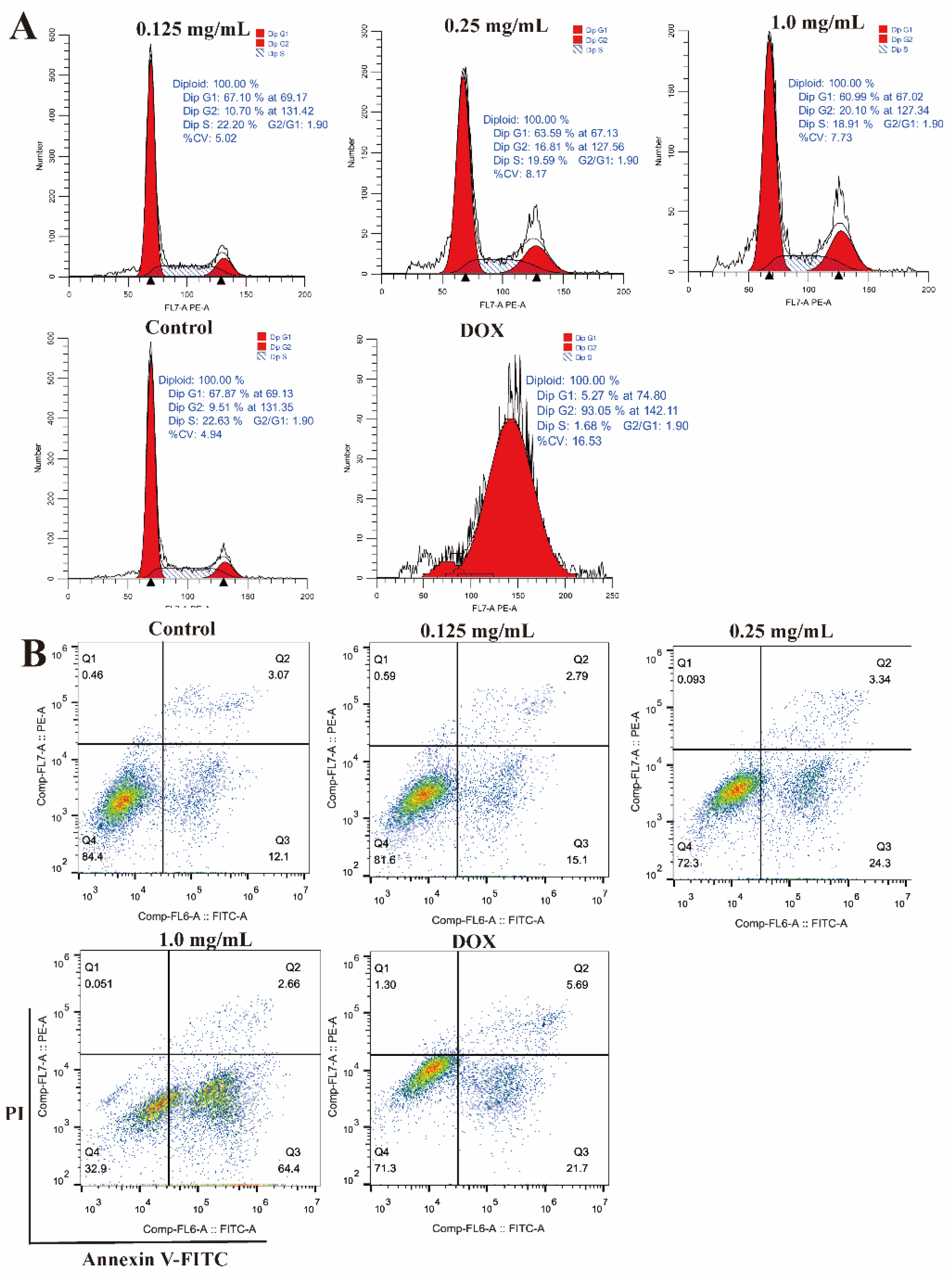

2.10. Effects of CLYF on the Cell Cycle and Apoptosis

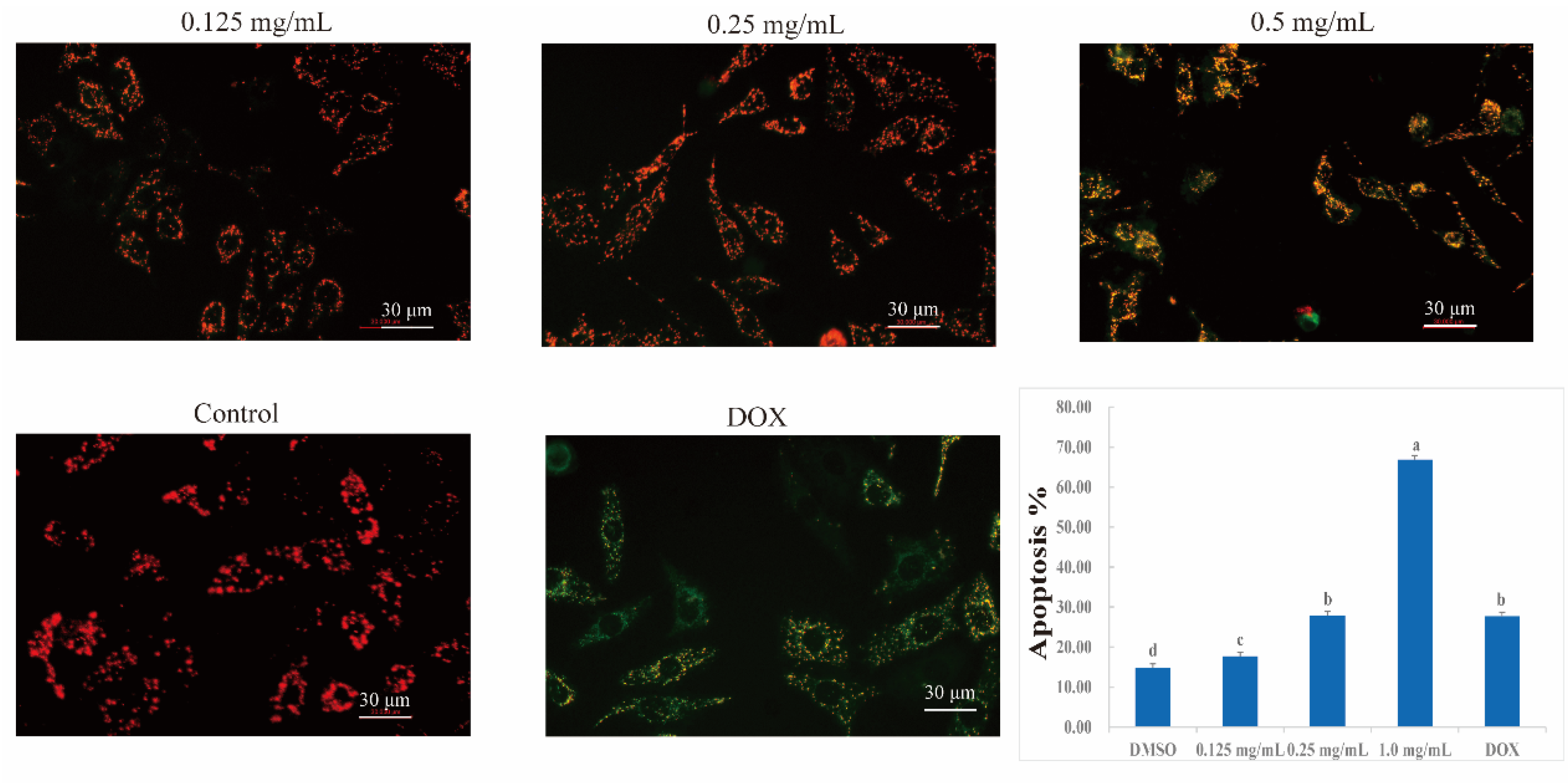

2.11. Effects of CLYF on Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Medicinal Materials, Chemicals, Reagents, Cell Culture and Treatment

4.2. CLYF Preparation and Extraction

4.3. Collection of Active Chemical Compounds and Their Corresponding Targets in CLYF

4.4. Collection of Disease-Related Proteins and Therapeutic Targets

4.5. Network Construction and Analysis

4.6. GO and KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analyses

4.7. Microarray data analysis

4.8. Survival analysis

4.9. Molecular Docking between CLYF Active Compounds and Their Target Proteins

4.10. Determination of Six Core Active Compounds Content

4.11. Cell Proliferation Assay

4.12. Cell Cycle and Apoptosis Assays

4.13. Determination of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

4.14. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA-A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Niu, H.M.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Hu, X.Y.; Li, H. Medicinal values and their chemical bases of Paris. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2015, 40, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Wang, W.; Fang, B.; Ma, F.Y.; Zheng, Q.; Deng, P.Y.; Zhao, S.S.; Chen, M.J.; Yang, G.X.; He, G.Y. Antitumor effect of germacrone on human hepatoma cell lines through inducing G2/M cell cycle arrest and promoting apoptosis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 698, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.D.; Roberts, L.R. Hepatocellular carcinoma: a global view. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 7, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Dikshit, R.; Eser, S.; Mathers, C.; Rebelo, M.; Parkin, D.M.; Forman, D.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, E359–E386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, H.; Yu, C.X.; Liu, R.; Xing, B.; Jia, B.; He, J.C.; Jia, X.T.; Feng, X.J.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Dang, W.L.; Hu, Z.M.; Deng, X.P.; Guo, P.; Liu, Z.D.; Pan, W.S. Phytoestrogen-derived multifunctional ligands for targeted therapy of breast cancer. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 18, 100827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.M.; Shi, H.X.; Sugimoto, M.; Bandow, K.; Sakagami, H.; Amano, S.; Deng, H.B.; Ye, Q.Y.; Gai, Y.; Xin, X.L.; Xu, Z.Y. Feiyanning formula induces apoptosis of lung adenocarcinoma cells by activating the mitochondrial pathway. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 690878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaou, M.; Pavlopoulou, A.; Georgakilas, A.G.; Kyrodimos, E. The challenge of drug resistance in cancer treatment: a current overview. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 2018, 35, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, B.; Zhao, C.P.; Zhang, C.H.; Xiao, Y.; Yan, G.L.; Liu, L.; Pan, H.D. Elucidation of the anti-inflammatory mechanism of Er Miao San by integrative approach of network pharmacology and experimental verification. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 175, 106000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.Q.; Jia, C.X.; Wu, H.X.; Liao, Y.J.; Yang, K.; Li, S.S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.L.; Li, G.; Guan, F.X.; Leung, E.; Yuan, Z.Q.; Hua, Q.; Pan, R.Y. Nao Tan Qing ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology by regulating glycolipid metabolism and neuroinflammation: A network pharmacology analysis and biological validation. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 185, 106489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, G.H.; Wu, C.H.; Li, J.; Liang, B.L.; Zhang, F.L.; Fan, X.X.; Li, Z.W.; Wang, Y.J.; Li, Z.H.; Liu, D.; Leung, E.L.H.; Chen, J.X. Network pharmacology based investigation into the effect and mechanism of Modified Sijunzi Decoction against the subtypes of chronic atrophic gastritis. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 144, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.X.; Zhao, Y.Q.; He, Y.; Disayathanoowat, T.; Pandith, H.; Inta, A.; Yang, L.X. Cytotoxic and pro-apoptotic effects of botanical drugs derived from the indigenous cultivated medicinal plant Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1100825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.H.; Wang, Z.J.; Huang, Y.; O'Barr, S.A.; Wong, R.A.; Yeung, S.; Chow, M.S.S. Ginseng and anticancer drug combination to improve cancer chemotherapy: a critical review. Evid. base Compl. Alternative Med. 2014, 2014, 168940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demain, A.L.; Vaishnav, P. Natural products for cancer chemotherapy. Microb. Biotechnol. 2011, 4, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.H.; Li, C.I.; Lin, C.C.; Lin, J.G.; Chiang, J.H.; Li, T.C. Traditional Chinese medicine as adjunctive therapy improves the long-term survival of lung cancer patients. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 143, 2425–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Song, S.Y.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Ren, X.; Zhang, P.; Li, X.; Fu, X.M.; Wang, C.Y. The underlying mechanisms of anti-hepatitis B effects of formula Le-Cao-Shi and its single herbs by network pharmacology and gut microbiota analysis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 148, 112692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Cheng, J.T.; Liu, A. Research and development strategies in classical herbal formulae. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2017, 42, 1814–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Pharmacopoeia Committee, Pharmacopoeia of the people's Republic of China (I). China Pharmaceutical Science and Technology Press, Beijing, 2020.

- Li, H. The Genus Paris (Trilliaceae). Science press, Beijing, 1998.

- Ji, Y.H. A Monograph of Paris (Melanthiaceae): Morphology, Biology, Systematics and Taxonomy. Science press, Beijing, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, A.L. Network pharmacology, Nat. Biotechno. 2007, 25, 1110–1111. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.X.; Gao, W.H.; Zeng, P.H.; Chen, C.L.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J.Y. Exploring the effect of Gupi Xiaoji Prescription on hepatitis B virus-related liver cancer through network pharmacology and in vitro experiments. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 139, 111612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.H.; He, C.F.; Mo, A.E.; Zhan, X.K.; Yang, C.Z.; Guo, W.; Sun, L.L.; Su, W.W.; Lin, L.Z. A Mechanism Exploration for the Yi-Fei-San-Jie Formula against Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Based on UPLC-MS/MS, Network Pharmacology, and In Silico Verification. J. Evidence-Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2023, 2023, 3436814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zhang, F.Y.; Liu, S.; Jiang, Y.P.; Ouyang, D.S. Systematic investigation of the pharmacological mechanism for renal protection by the leaves of Eucommia ulmoides Oliver using UPLC-Q-TOF/ MS combined with network pharmacology analysis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 140, 111735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Lee, T.K.W. Network-pharmacology-based study on active phytochemicals and molecular mechanism of cnidium monnieri in treating hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.L.; Fu, X.J.; Wang, Z.Q.; Yang, L.; Yang, J.; Deng, H.B. Integrating network pharmacology prediction and experimental investigation to verify ginkgetin anti-invasion and metastasis of human lung adenocarcinoma cells via the Akt/GSK-3 beta/Snail and Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1135601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaqat, M.; Qasim, M.; ul Qamar, M.T.; Masoud, M.S.; Ashfaq, U.A.; Noor, F.; Fatima, K.; Allemailem, K.S.; Alrumaihi, F.; Almatroudi, A. Advanced network pharmacology study reveals multi-pathway and multi-gene regulatory molecular mechanism of Bacopa monnieri in liver cancer based on data mining, molecular modeling, and microarray data analysis. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 161, 107059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, S.L.; Zhao, S.H.; Tian, X.C.; Liu, F.; Lu, X.L.; Zang, H.C.; Li, F.; Xiang, L.Q.; Li, L.N.; Jiang, S.L. Molecular and metabolic mechanisms of bufalin against lung adenocarcinoma: New and comprehensive evidences from network pharmacology, metabolomics and molecular biology experiment. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 157, 106777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.L.; Hong, Y.J.; Huang, M.A.; Chen, M.M.; Gan, H.J. Effect of kaempferol on hedgehog signaling pathway in rats with-chronic atrophic gastritis–Based on network pharmacological screening and experimental verification. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 145, 112451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.L.; Yan, Q.; Luo, Y.H.; Wang, B.Q.; Deng, S.C.; Luo, H.Y.; Ye, B.Q.; Wang, X.W. Molecular mechanism of Ganji Fang in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma based on network pharmacology, molecular docking and experimental verification technology. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1016967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.Z.; Li, P.; Fu, B.Z.; Chuo, W.J.; Gao, K.; Zhang, W.X.; Wang, J.Y.; Chen, J.X.; Wang, W. Systems-biology dissection of mechanisms and chemical basis of herbal formula in treating chronic myocardial ischemia. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 114, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Li, H.; Shen, X.; Zeng, J.; Yue, L.; Lin, J.; Yang, J.; Zou, W.J.; Li, Y.; Qin, D.L. Elucidation of the molecular mechanism of Sanguisorba officinalis L. against leukopenia based on network pharmacology. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 132, 110934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.S.; Sun, J.J.; Wang, X.; Hu, Y.Y.; Feng, Q.; Gou, X.J. Research on the Mechanism of Qushi Huayu Decoction in the Intervention of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Based on Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking Technology. BioMed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 1704960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, F.; Lu, C.L.; Wang, C.G.; Hu, C.W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.L.; Han, L.; Chen, Z. Uncovering the mechanism of Kang-ai injection for treating intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma based on network pharmacology, molecular docking, and in vitro validation. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1129709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Wang, X.Q.; Cao, G.; Sun, L.; Ho, R.J.Y.; Han, Y.Q.; Hong, Y.; Wu, D.L. Prediction of the potential mechanism of compound gingerol against liver cancer based on network pharmacology and experimental verification. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2022, 74, 869–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lv, P.; Ma, J.M.; Chen, N.; Guo, H.S.; Chen, Y.; Gan, X.R.; Wang, R.; Liu, X.Q.; Fan, S.F.; Cong, B.; Kang, W.Y. Antrodia cinnamomea exerts an anti-hepatoma effect by targeting PI3K/AKT-mediated cell cycle progression in vitro and in vivo. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 890–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Lan, Y.X.; Ran, Q.Q.; Gan, Q.R.; Tang, S.Q.; Huang, W. Exploration of the Potential Targets and Molecular Mechanism of Carthamus tinctorius L. for Liver Fibrosis Based on Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking Strategy. Processes 2022, 10, 1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, S.; Javed, M.R.; Aslam, S.; Noor, F.; Javed, H.M.F.; Seemab, R.; Rehman, A.; Aslam, M.F.; Paray, B.A.; Gulnaz, A. Network Pharmacology and Bioinformatics Approach Reveals the Multi-Target Pharmacological Mechanism of Fumaria indica in the Treatment of Liver Cancer. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kron, A.; Alidousty, C.; Scheffler, M.; Merkelbach-Bruse, S.; Seidel, D.; Riedel, R.; Ihle, M.A.; Michels, S.; Nogova, L.; Fassunke, J.; Heydt, C.; Kron, F.; Ueckeroth, F.; Serke, M.; Kruger, S.; Grohe, C.; Koschel, D.; Benedikter, J.; Kaminsky, B.; Schaaf, B.; Braess, J.; Sebastian, M.; Kambartel, K.O.; Thomas, R.; Zander, T.; Schultheis, A.M.; Buttner, R.; Wolf, J. Impact of TP53 mutation status on systemic treatment outcome in ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 2068–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, H.Y.; Gao, W.H.; Tan, X.N.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, K.X.; Zeng, P.H. Effect of Gupi Xiaoji Decoction on Pyroptosis of HepG2.2.15 Cells Based on Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking. Chin. J. Exp. Tradit. Med. Formulae 2022, 28, 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Ma, Z.S.; Dong, L.F.; Gao, S.; Ma, P.Z.; Zhang, W. Mechanisms of Cidan capsules in the treatment of liver cancer based on network pharmacology and molecular docking. Chin. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 38, 2766–2770. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Jin, C.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Zhang, Q.X.; Li, X.X.; Zhang, L. Molecular mechanism of Spatholobi Caulis in treatment of lung cancer based on network pharmacology and molecular docking. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2021, 46, 837–844. [Google Scholar]

- Bailly, C.; Xiang, C.; Zhang, J.H. Traditional Uses and Phytochemical Constituents of Cynanchum otophyllum C.K.Schneid (Qingyangshen). World J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2023, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batiha, G.E.; Beshbishy, A.M.; El-Mleeh, A.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Devkota, H.P. Traditional Uses, Bioactive Chemical Constituents, and Pharmacological and Toxicological Activities of Glycyrrhiza glabra L. (Fabaceae). Biomolecules 2020, 10, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, A.B.; Brinckmann, J.A.; Pei, S.J.; Luo, P.; Schippmann, U.; Long, X.; Bi, Y.F. High altitude species, high profits: Can the trade in wild harvested Fritillaria cirrhosa (Liliaceae) be sustained? J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 223, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.B.; Xu, J.; Xu, Y.Q.; Zhang, C.C.; Wang, H.W.; He, Y.M.; Wang, T.; Yuan, D. Cardioprotective effects of saponins from Panax japonicus on acute myocardial ischemia against oxidative stress-triggered damage and cardiac cell death in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 140, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, J.C.; Woo, S.U.; Son, M.; Park, J.Y.; Choi, W.S.; Chang, K.T.; Kim, S.U.; Yoon, E.K.; Kim, Y.H.; Shin, H.M.; Lee, S.H. Anti-tumor activity of Gastrodia elata Blume is closely associated with a GTP-Ras-dependent pathway. Oncol. Rep. 2007, 18, 849–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancuso, C.; Santangelo, R. Panax ginseng and Panax quinquefolius: From pharmacology to toxicology. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 107, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, J.; Cheng, Y.T.; Gao, Y.T.; Zhao, C.F.; Li, L.J.; She, R.; Yang, X.Y.; Xiao, W.; Yang, X. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer function of Engleromyces goetzei Henn aqueous extract on human intestinal Caco-2 cells treated with t-BHP. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 3450–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhou, X.L. Review on study advances on rare and endangered medicinal herb Psammosilene tunicoides. China J. Trad. Chin. Med. Phar. 2011, 26, 1795–1797. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, S.Y.; Wang, C.; Han, S.W.; Sun, M.H.; Li, S. Phenanthrenequinone enantiomers with cytotoxic activities from the tubers of Pleione bulbocodioides. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.G.; Zhao, Y.L.; Zhang, J.; Zuo, Z.T.; Zhang, Q.Z.; Wang, Y.Z. The traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacological properties of Paris L. (Liliaceae): A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 278, 114293–114324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.R.; Yuen, S.C.; Fan, G.Y.; Cong, W.H.; Leung, S.W.; Lee, S.M.Y. Identification of certain Panax species to be potential substitutes for Panax notoginseng in hemostatic treatments. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 134, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, D.; Xiang, T.T.; Huo, Y.X.; Liu, C.Q.; Wang, T.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Dun, Y.Y.; Zhao, H.X.; Zhang, C.C. Preventive effects of total saponins of Panax japonicus on fatty liver fibrosis in mice. Arch. Med. Sci. 2018, 14, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, C.F.; Liu, C.Q.; Wang, T.; He, Y.M.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Dun, Y.Y.; Zhao, H.X.; Ren, D.M.; Wang, J.J.; Zhang, C.C.; Yuan, D. Chikusetsu saponin IVa ameliorates high fat diet-induced inflammation in adipose tissue of mice through inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and NF-kappa B signaling. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 31023–31040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.X.; Fan, L.Z.; Jiang, S.; Yang, X.R.; Wang, X.T.; Yang, C.J. Recent progress of chemical constituents and pharmacological effects of Fritillaria. Chin. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 32, 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Wang, M.Y.; Zafar, S.; Jiang, L.; Luo, J.Y.; Zhao, H.M.; Tian, S.Y.; Zhu, Y.Q.; Peng, C.Y.; Wang, W. Phytochemistry, pharmacology and clinical applications of the traditional Chinese herb Pseudobulbus Cremastrae seu Pleiones (Shancigu): A review. Arabian J. Chem. 2022, 15, 104090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.W.; Shao, S.Y.; Sun, H.; Li, S. Two new phenylpropanoid glycosidic compounds from the pseudobulbs of Pleione bulbocodioides and their hepatoprotective activity. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 36, 1980–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.W.; Wang, C.; Cui, B.S.; Sun, H.; Zhang, J.J.; Li, S. Hepatoprotective activity of glucosyloxybenzyl succinate derivatives from the pseudobulbs of Pleione bulbocodioides. Phytochem. 2019, 157, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.S. Yu Long Ben Cao. Yunnan Science and Technology Publishing House, Kunming, 2016.

- Bai, X.; Zhang, G.Q.; Liu, T.X. Research Progress in Chemical Compoents, Pharmacological Effectiveness and secondary metabolism of Psammosilene tunicoides. Shizhen Med. Mater. Res. 2014, 25, 429–431. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.P.; Choi, H.K.; Brinckmann, J.A.; Jiang, X.; Huang, L.F. Chemical analysis of Panax quinquefolius (North American ginseng): A review. J. Chromatogr. A 2015, 1426, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.Z.; Hu, Y.; Wu, W.Y.; Ye, M.; Guo, D.A. Saponins in the genus Panax L. (Araliaceae): A systematic review of their chemical diversity. Phytochem. 2014, 106, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.H.; Kuruganti, R.; Gao, Y. Recent Advances in Ginsenosides as Potential Therapeutics Against Breast Cancer. Curr. Trends Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 2334–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, R.B.; Zhong, Y.; Navas, V. Li, M.Z.C.; Toy, B.R.; Alavarez, J.G. American ginseng and breast cancer therapeutic agents synergistically inhibit MCF-7 breast cancer cell growth. J. Surg. Oncol. 1999, 72, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.L.; Wang, X.H.; Wu, G. Mushrooms of Yunnan. Science Press, Beijing, 2022.

- Liu, J.K. Biologically active substances from mushrooms in Yunnan, China. Heterocycles 2002, 57, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Xiang, C.; Qin, Y.; He, J.; Li, B.C.; Li, P. Cytotoxicity of pregnane glycosides of Cynanchum otophyllum. Steroids 2016, 104, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.F.; Wang, Y.Q.; Yang, B.; Zhang, R.S. Cytotoxic and apoptosis-inducing properties of a C-21-steroidal glycoside isolated from the roots of Cynanchum auriculatum. Oncol. Lett. 2013, 5, 1407–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.R.; Yue, G.G.L.; Lee, J.K.M.; Lau, C.B.S.; Qiu, M.H. Potential neurotrophic activity and cytotoxicity of selected C21 steroidal glycosides from Cynanchum otophyllum. Med. Chem. Res. 2020, 29, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.B.; Hou, J.L.; Li, W.B.; Luo, L.; Ye, M.; Zhao, Z.Z.; Wang, W.Q. A review on the plant resources of important medicinal licorice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 301, 115823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salawu, S.O.; Ibukun, E.O.; Esan, I.A. Nutraceutical values of hot water infusions of moringa leaf (Moringa oleifera) and licorice root (Glycyrrhiza glabra) and their effects on liver biomarkers in Wistar rats. J. Food Meas Charact. 2018, 13, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.S.; Thakur, K.; Hussain, S.S.; Zhang, J.G.; Xiao, G.R.; Wei, Z.J. Licochalcone A from licorice root, an inhibitor of human hepatoma cell growth via induction of cell apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 120, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, H.D.; Zhou, H.Y.; Sui, Y.P.; Du, X.L.; Wang, W.H.; Dai, L.; Sui, F.; Huo, H.R.; Jiang, T.L. The rhizome of Gastrodia elata Blume-An ethnopharmacological review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 189, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, G.W.; Yang, T.M.; Wang, C.Y.; Su, H.W.; Xiang, M.X. Gastrodin stimulates anticancer immune response and represses transplanted H22 hepatic ascitic tumor cell growth: involvement of NF-kappa B signaling activation in CD4+T cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013, 269, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Dai, H.H.; Dong, H.Y.; Sun, C.T.; Yang, Z.; Han, J.Q. EGFR mutations and clinical outcomes of chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Lung Cancer 2014, 85, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruix, J.; Sherman, M.; Llovet, J.M.; Beaugrand, M.; Lencioni, R.; Burroughs, A.K.; Christensen, E.; Pagliaro, L.; Colombo, M.; Rodes, J. Clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona-2000 EASL Conference. J. Hepatol. 2001, 35, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Bi, T.T.; Shen, G.H.; Li, Z.M.; Wu, G.L.; Wang, Z.; Qian, L.Q.; Gao, Q.G. Lupeol induces apoptosis and inhibits invasion in gallbladder carcinoma GBC-SD cells by suppression of EGFR/MMP-9 signaling pathway. Cytotechnology 2016, 68, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyati, M.K.; Morgan, M.A.; Feng, F.Y.; Lawrence, T.S. Integration of EGFR inhibitors with radiochemotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, H.; Makino, T.; Yamasaki, M.; Tanaka, K.; Miyazaki, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Kurokawa, Y.; Nakajima, K. , Takiguchi, S.; Mori, M.; Doki, Y. PRIMA-1 induces p53-mediated apoptosis by upregulating Noxa in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma with TP53 missense mutation. Cancer Sci. 2018, 109, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, P.; White-Gilbertson, S.; Beeson, G.; Beeson, C.; Ogretmen, B.; Norris, J. Ceramide Synthase 6 Maximizes p53 Function to Prevent Progeny Formation from Polyploid Giant Cancer Cells. Cancers 2021, 13, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.; Wang, F.; Chen, Q.Q.; Liu, J.J.; Huang, Q.F.; Tang, H.; Ding, C.S.; Zhu, K.J. Exploration of Mechanism of Huxiang OUYANGs Genre of Miscellaneous Diseases on Treating Lung Cancer Based on Data Mining, Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking. Trad. Chin. Drug Res. Clin. Plarm. 2022, 33, 1071–1082. [Google Scholar]

- Noorolyai, S.; Shajari, N.; Baghbani, E.; Sadreddini, S.; Baradaran, B. The relation between PI3K/AKT signalling pathway and cancer. Gene 2019, 698, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogel, A.; Willoughby, J.E.; Buchan, S.L.; Leonard, H.J.; Thirdborough, S.M.; Al-Shamkhani, A. Akt signaling is critical for memory CD8(+) T-cell development and tumor immune surveillance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017, 114, E1178–E1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.Y.; Huang, D.Y.; Xu, J.W. ARHGAP20 expression inhibited HCC progression by regulating the PI3K-akt signaling pathway. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 2021, 8, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezatabar, S.; Karimian, A.; Rameshknia, V.; Parsian, H.; Majidinia, M.; Kopi, T.A.; Bishayee, A.; Sadeghinia, A.; Yousefi, M.; Monirialamdari, M.; Yousefi, B. RAS/MAPK signaling functions in oxidative stress, DNA damage response and cancer progression. EMBO J. 2019, 234, 14951–14965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.Y.; Zhou, B.; Pache, L.; Chang, M.; Khodabakhshi, A.H.; Tanaseichuk, O.; Benner, C.; Chanda, S.K. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, E.R.; Truesdale, A.T.; McDonald, O.B.; Yuan, D.; Hassell, A.; Dickerson, S.H.; Ellis, B.; Pennisi, C.; Horne, E.; Lackey, K.; Alligood, K.J.; Rusnak, D.W.; Gilmer, T.M.; Shewchuk, L. A unique structure for epidermal growth factor receptor bound to GW572016 (Lapatinib): relationships among protein conformation, inhibitor off-rate, and receptor activity in tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 6652–6659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiley, K.Z.; Shokat, K.M. A Small Molecule Reacts with the p53 Somatic Mutant Y220C to Rescue Wild-type Thermal Stability. Cancer Discovery 2023, 13, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, N.; Salguero, A.L.; Liu, A.Z.; Chen, Z.; Dempsey, D.R.; Ficarro, S.B.; Alexander, W.M.; Marto, J.A.; Li, Y.; Amzel, L.M.; Gabelli, S.B.; Cole, P.A. Akt Kinase Activation Mechanisms Revealed Using Protein Semisynthesis. Cell 2018, 174, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zheng, S.L.; Li, X.; Li, J.L.; Qiang, O.; Liu, R.; He, L. Synthesis and anti-breast cancer activity of new indolylquinone derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 54, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.Z.; Wei, W.T.; Chen, H.; Chen, K.J.; Tong, H.F.; Wang, Z.H.; Ni, Z.L.; Liu, H.B.; Guo, H.C.; Liu, D.L. Antitumor activity of emodin against pancreatic cancer depends on its dual role: promotion of apoptosis and suppression of angiogenesis. PLoS One 2012, 7, e42146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Wei, W.; Wang, C.; Yue, H.; Ma, D.; Zhu, C.; Ma, G.H.; Du, Y.G. Apoferritin-camouflaged Pt nanoparticles: surface effects on cellular uptake and cytotoxicity. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 7105–7110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tominaga, H.; Ishiyama, M.; Ohseto, F.; Sasamoto, K.; Hamamoto, T.; Suzuki, T.; Watanabe, M. A water-soluble tetrazolium salt useful for colorimetric cell viability assay. Anal. Commun. 1999, 36, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Kang, S.S.; Kim, Y.S. Antitumor activity of jujuboside B and the underlying mechanism via induction of apoptosis and autophagy. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rank | Pathways | Number of genes | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | hsa05200: Pathways in cancer | 17 | 1.21E−27 |

| 2 | hsa05205: Proteoglycans in cancer | 14 | 1.03E−26 |

| 3 | hsa05163: Human cytomegalovirus infection | 14 | 3.94E−26 |

| 4 | hsa05167: Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection | 13 | 1.54E−24 |

| 5 | hsa05207: Chemical carcinogenesis–receptor activation | 12 | 1.23E−21 |

| 6 | hsa05210: Colorectal cancer | 10 | 3.63E−21 |

| 7 | hsa05224: Breast cancer | 11 | 3.95E−21 |

| 8 | hsa05160: Hepatitis C | 11 | 8.33E−21 |

| 9 | hsa04933: AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications | 10 | 1.77E−20 |

| 10 | hsa05213: Endometrial cancer | 9 | 3.02E−20 |

| 11 | hsa05417: Lipid and atherosclerosis | 11 | 2.87E−19 |

| 12 | hsa01521: EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance | 9 | 5.80E−19 |

| 13 | hsa05219: Bladder cancer | 8 | 6.86E−19 |

| 14 | hsa05161: Hepatitis B | 10 | 2.59E−18 |

| 15 | hsa05215: Prostate cancer | 9 | 4.00E−18 |

| 16 | hsa04010: MAPK signaling pathway | 11 | 9.44E−18 |

| 17 | hsa04510: Focal adhesion | 10 | 2.59E−17 |

| 18 | hsa04919: Thyroid hormone signaling pathway | 9 | 3.14E−17 |

| 19 | hsa05165: Human papillomavirus infection | 11 | 3.52E−17 |

| 20 | hsa04151: PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | 11 | 7.40E−17 |

| NO. | Target | PDB ID | Protein name | Compound name | Binging energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | EGFR | 1XKK | CBM9 | Verticinone | −6.36 |

| 2 | CBM16 | Solanidine | −7.65 | ||

| 3 | ZJ2 | Rosenonolactone | −7.07 | ||

| 4 | TP53 | 8DC6 | CBM9 | Verticinone | −4.01 |

| 5 | CBM16 | Solanidine | −5.03 | ||

| 6 | ZJ2 | Rosenonolactone | −3.60 | ||

| 7 | AKT1 | 6NPZ | CBM9 | Verticinone | −3.92 |

| 8 | CBM16 | Solanidine | −4.28 | ||

| 9 | ZJ2 | Rosenonolactone | −3.97 |

| No. | Extract or compound | Compound name | IC50 ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLYF-A | Crude extract (mg/mL) | Not applicable | 0.25 ± 0.03e |

| CLYF-W | > 5 | ||

| CBM9 | Compound (μM) | Verticinone | 76.44 ± 0.88d |

| CBM16 | Solanidine | 128.17 ± 16.00d | |

| SQ7 | Quercetin | 194.97 ± 5.31b | |

| CL2 | Diosgenin | 244.80 ± 0.79a | |

| CL3 | Pennogenin | 151.23 ± 9.32c | |

| CF3 | Ginsenoside Rh2 | 74.78 ± 2.48d | |

| DOX | Positive control (μM) | Doxorubicin | 0.15 ± 0.03e |

| G0/G1 (%) | S (%) | G2/M (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 68.24±0.93a | 22.15±0.84a | 9.62±0.17d |

| 0.125 mg/mL | 66.77±0.65a | 22.21±0.15a | 11.02±0.51d |

| 0.25 mg/mL | 62.76±1.36b | 20.62±0.93b | 16.62±1.43c |

| 1.0 mg/mL | 60.76±1.42b | 19.16±0.39c | 20.08±1.09b |

| DOX | 5.34±0.57c | 1.80±0.26d | 92.87±0.37a |

| Live cells (%) | Early apoptosis (%) | Late apoptosis (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 84.60±0.92a | 11.97±0.71e | 2.89±0.31c |

| 0.125 mg/mL | 81.83±0.32b | 14.93±0.38d | 2.78±0.08c |

| 0.25 mg/mL | 71.93±0.64c | 24.43±0.23b | 3.50±0.37b |

| 1.0 mg/mL | 33.03±1.21d | 64.03±1.19a | 2.83±0.16c |

| DOX | 70.83±0.64c | 21.67±1.25c | 6.02±0.31a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).