Submitted:

16 August 2024

Posted:

20 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

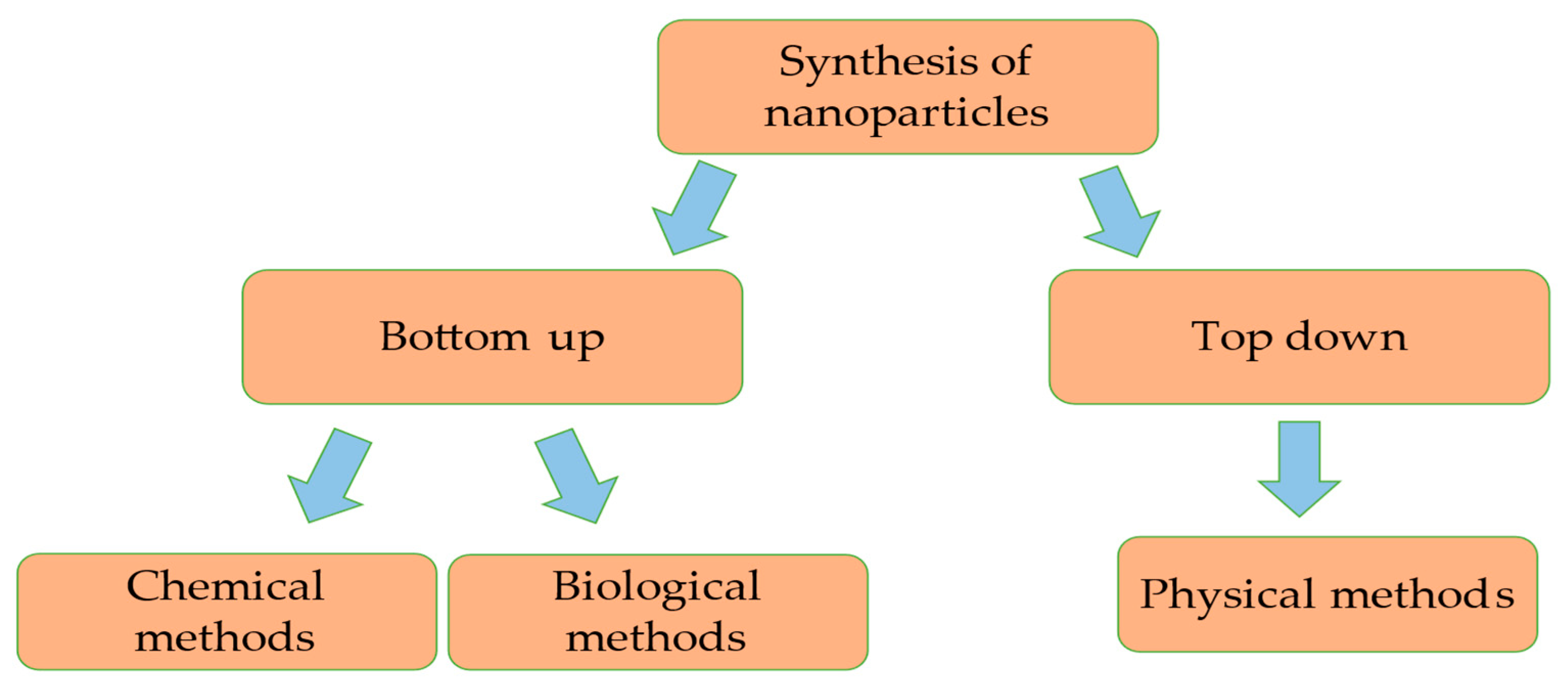

2. Synthesis of TiO2

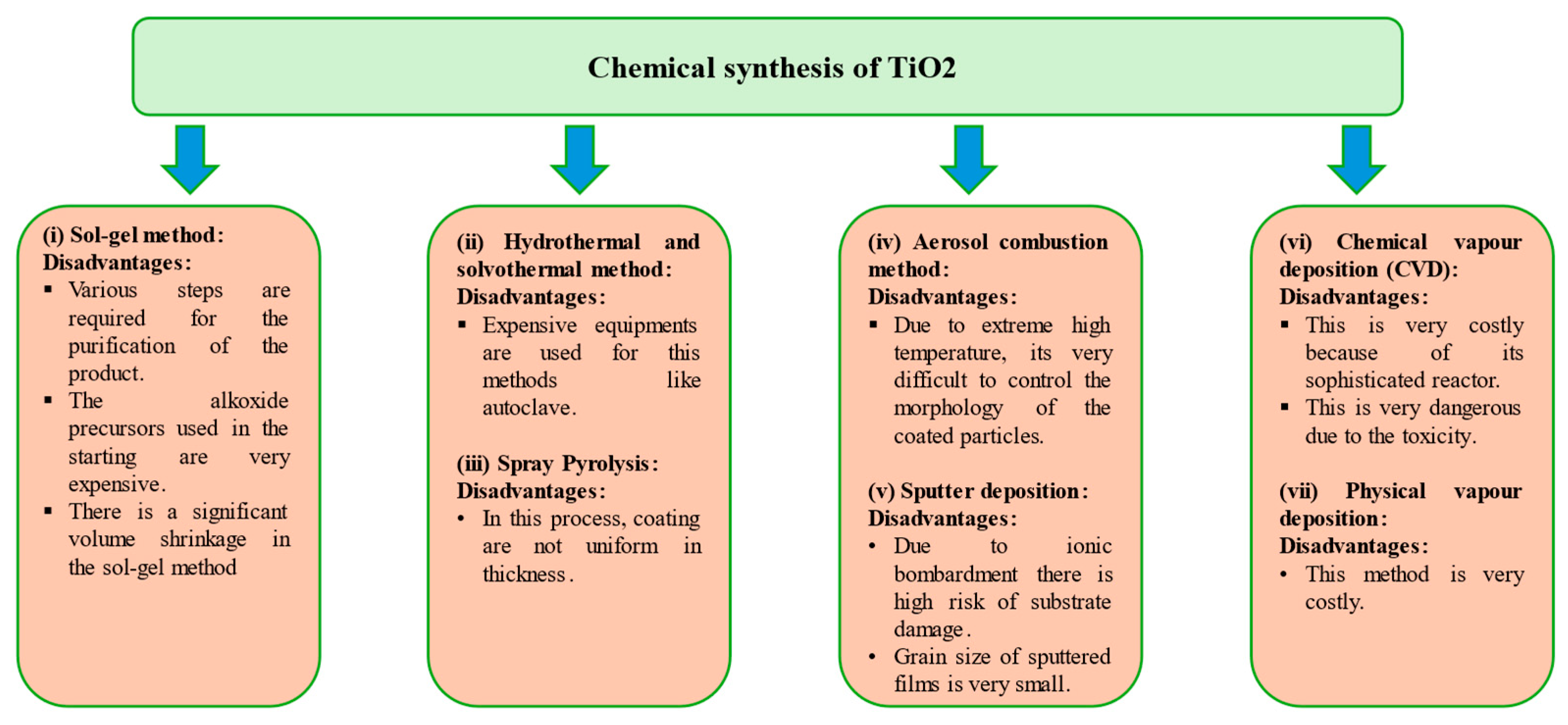

2.1. Chemical Synthesis of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles

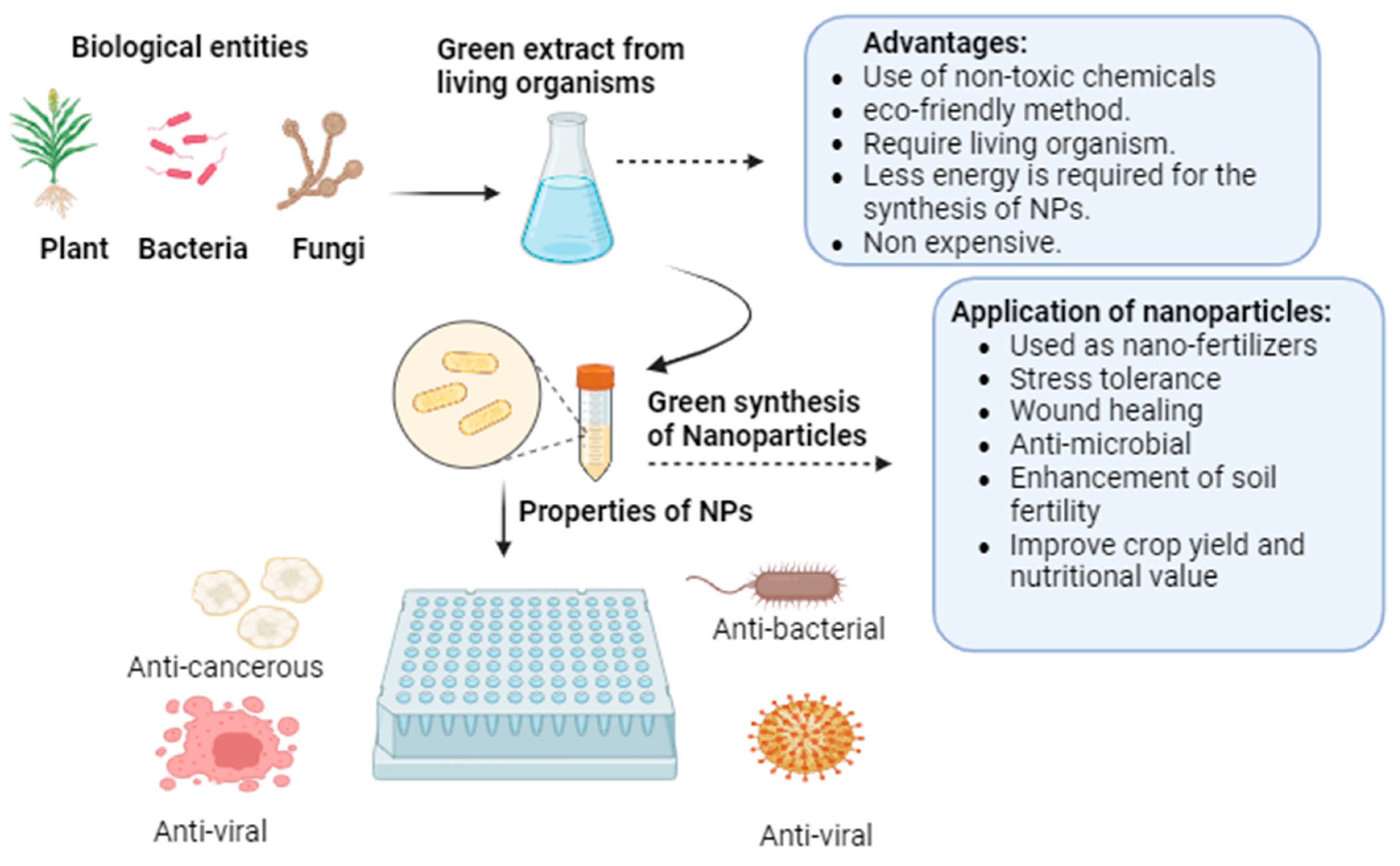

2.2. Biological Synthesis of TiO2 NPs

2.2.1. Synthesis from Green Plants Extract NPs

2.2.2. Synthesis from Microbial Extract

2.2.3. Synthesis from Other Biological Sources

3. Applications of Titanium Dioxide

3.1. Environmental Stresses and Effect of TiO2 NPs on Crop Production

3.2. Impact of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles on Sorption of Heavy Metals from Wastewater

3.3. Photolytic Properties of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles

3.4. Antimicrobial Activity of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles

4. Use of Titanium Dioxide as Nanofertilizers

5. Nanotoxicity of Titanium Dioxide

| Plant species | Particle size | concentration | Toxic effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lepidium sativum | Greater than 50 nm | Above 100mg/kg | Inhibition of root growth and no effect on seed germination |

| Lycopersicum esculentum | 25-29 nm | 80 mg/l | Reduction in the concentration of chlorophyll and increased SOD enzymatic activity |

| Oryza sativa | 10-30 nm | 2000mg/l | Inhibit microbial symbiosis around roots |

| Zea mays | Less than 100 nm and 5 nm | Above 4% in distilled water | Reduction in root growth and delay seed germination |

| Allium cepa | Less than 100 nm | Above 5 mg/l | Reduction in chlorophyll synthesis and seed germination |

| Pisum sativum | 15-20 nm, 10nm | Above 250 mg/l | Increase in concentration of chlorophyll and enzymatic activity like CAT and APOX in roots and leaves |

| Brassica sp. | Less than 500 nm | Above 1000 mg/l | Decrease in seed growth and increase in antioxidants |

6. Mechanism of Nanotoxicity

7. Gene Toxicity of Nanoparticles

8. Disposal Methods of Nanoparticles

8.1. Recycling of Waste Nanomaterials

8.2. Nanomaterial Disposal by Incineration

9. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chandran, S.P.; Chaudhary, M.; Pasricha, R.; Ahmad, A.; Sastry, M. Synthesis of gold nanotriangles and silver nanoparticles using Aloe vera plant extract. Biotechnol. Prog. 2006, 22, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraz, A.; Faizan, M.; Fariduddin, Q.; Hayat, S. Response of Titanium Nanoparticles to Plant Growth: Agricultural Perspectives. Sustain. Agric. Rev. 2020, 41, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batley, G.E.; Kirby, J.K.; McLaughlin, M.J. Fate and risks of nanomaterials in aquatic and terrestrial environments. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 46, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccinno, F.; Gottschalk, F.; Seeger, S.; Nowack, B. Industrial production quantities and uses of ten engineered nanomaterials in Europe and the world. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2012, 14, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, S.; Rashid, F.; Tahir, H.; Liaqat, I.; Latif, A.A.; Naseem, S.; Khalid, A.; Haider, N.; Hani, U.; Dawoud, R.A.; et al. Antibacterial and Cytotoxic Effects of Biosynthesized Zinc Oxide and Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racovita, A.D. Titanium Dioxide: Structure, Impact, and Toxicity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, R.J.B.; van Bemmel, G.; Herrera-Rivera, Z.; Helsper, H.P.F.G.; Marvin, H.J.P.; Weigel, S.; Tromp, P.C.; Oomen, A.G.; Rietveld, A.G.; Bouwmeester, H. Characterization of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in food products: Analytical methods to define nanoparticles. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 6285–6293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, A.; Majumdar, S.; Servin, A.D.; Pagano, L.; Dhankher, O.P.; White, J.C. Carbon nanomaterials in agriculture: A critical review. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Chen, B.; Sun, X.; Qu, K.; Ma, F.; Du, M. Interaction of TiO2 nanoparticles with the marine microalga Nitzschia closterium: Growth inhibition, oxidative stress and internalization. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 508, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raliya, R.; Biswas, P.; Tarafdar, J.C. TiO2 nanoparticle biosynthesis and its physiological effect on mung bean (Vigna radiata L.). Biotechnol. Rep. 2015, 5, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Hong, F.; You, W.; Liu, C.; Gao, F.; Wu, C.; Yang, P. Influence of nano-anatase TiO2 on the nitrogen metabolism of growing spinach. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2006, 110, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel Latef, A.A.H.; Srivastava, A.K.; El-Sadek, M.S.A.; Kordrostami, M.; Tran, L.S.P. Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles Improve Growth and Enhance Tolerance of Broad Bean Plants under Saline Soil Conditions. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, S.A.; Elsheery, N.I.; Pashkovskiy, P.; Kuznetsov, V.; Allakhverdiev, S.I.; Zedan, A.M. Impact of Titanium Oxide Nanoparticles on Growth, Pigment Content, Membrane Stability, DNA Damage, and Stress-Related Gene Expression in Vicia faba under Saline Conditions. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagadevan, S.; Imteyaz, S.; Murugan, B.; Anita Lett, J.; Sridewi, N.; Weldegebrieal, G.K.; Fatimah, I.; Oh, W.C. A comprehensive review on green synthesis of titanium dioxide nanoparticles and their diverse biomedical applications. Green Process. Synth. 2022, 11, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdallah, N.M.; Alluqmani, S.M.; Almarri, H.M.; Al-Zahrani, A.A. Physical, chemical, and biological routes of synthetic titanium dioxide nanoparticles and their crucial role in temperature stress tolerance in plants. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horti, N.C.; Kamatagi, M.D.; Patil, N.R.; Nataraj, S.K.; Sannaikar, M.S.; Inamdar, S.R. Synthesis and photoluminescence properties of titanium oxide (TiO2) nanoparticles: Effect of calcination temperature. Optik 2019, 194, 163070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Sarkar, A.; Jha, R.; Kumar Sharma, A.; Sharma, D. Sol-gel–mediated synthesis of TiO2 nanocrystals: Structural, optical, and electrochemical properties. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2020, 17, 1400–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, V.M.; Natarajan, M.; Santhanam, A.; Asokan, V.; Velauthapillai, D. Size controlled synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles by modified solvothermal method towards effective photo catalytic and photovoltaic applications. Mater. Res. Bull. 2018, 97, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ali Haidry, A.; Xie, L.; Zavabeti, A.; Li, Z.; Yin, W.; Lontio Fomekong, R.; Saruhan, B. Acetone sensing applications of Ag modified TiO2 porous nanoparticles synthesized via facile hydrothermal method. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 533, 147383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Tungmunnithum, D.; Hano, C.; Abbasi, B.H.; Hashmi, S.S.; Ahmad, W.; Zahir, A. The current trends in the green syntheses of titanium oxide nanoparticles and their applications. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2018, 11, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasirian, M.; Mehrvar, M. Photocatalytic degradation of aqueous Methyl Orange usingnitrogen-doped TiO2 photocatalyst prepared by novelmethod of ultraviolet-assisted thermal synthesis. J. Environ. Sci. 2018, 66, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, M.P.; Patterson, D.R. Hypnotic approaches for chronic pain management: Clinical implications of recent research findings. Am. Psychol. 2014, 69, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebnalwaled, A.A.; Essai, M.H.; Hasaneen, B.M.; Mansour, H.E. Facile and surfactant-free hydrothermal synthesis of PbS nanoparticles: The role of hydrothermal reaction time. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017, 28, 1958–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcony, C.; Aguilar-Frutis, M.A.; García-Hipólito, M. Spray Pyrolysis Technique; High-K Dielectric Films and Luminescent Materials: A Review. Micromachines 2018, 9, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccaccini, A.; Keim, S.; Ma, R.; Li, Y.; Zhitomirsky, I. Electrophoretic deposition of biomaterials. J. R. Soc. Interface 2010, 7, S581–S613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, D.R.; Adhikari, N. An overview on common organic solvents and their toxicity. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2019, 28, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, A.S.; Kumar, K.; Redhu, S.; Bhardwaj, S. Microwave assisted synthesis: A green chemistry approach. Int. Res. J. Pharm. Appl. Sci. 2013, 3, 278–285. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi, H.-R.; Doostmohammadi, M. Nanoparticle synthesis, applications, and toxicity. In Applications of Nanobiotechnology; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoepe, N.M.; Mathipa, M.M.; Hintsho-Mbita, N.C. Biosynthesis of titanium dioxide nanoparticles for the photodegradation of dyes and removal of bacteria. Optik 2020, 224, 165728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Kumar, S.; Alok, A.; Upadhyay, S.K.; Rawat, M.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Bolan, N.; Kim, K.-H. The potential of green synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles as nutrient source for plant growth. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhapriya, S.; Gomathipriya, P. Green synthesis of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles by Trigonella foenum-graecum extract and its antimicrobial properties. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 116, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunny, N.E.; Mathew, S.S.; Chandel, N.; Saravanan, P.; Rajeshkannan, R.; Rajasimman, M.; Vasseghian, Y.; Rajamohan, N.; Kumar, S.V. Green synthesis of titanium dioxide nanoparticles using plant biomass and their applications—A review. Chemosphere 2022, 300, 134612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabi, G.; Raza, W.; Tahir, M.B. Green Synthesis of TiO2 Nanoparticle Using Cinnamon Powder Extract and the Study of Optical Properties. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2019, 30, 1425–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethy, N.K.; Arif, Z.; Mishra, P.K.; Kumar, P. Green synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles from Syzygium cumini extract for photo-catalytic removal of lead (Pb) in explosive industrial wastewater. Green Process. Synth. 2020, 9, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanulla, A.M.; Sundaram, R. Green synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles using orange peel extract for antibacterial, cytotoxicity and humidity sensor applications. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 8, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abisharani, J.M. , Devikala, S., Kumar, R.D., Arthanareeswari, M., Kamaraj, P. Green synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles using Cucurbita pepo seeds extract. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 14: 302–307. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Dalo, M.; Jaradat, A.; Albiss, B.A.; Al-Rawashdeh, N.A.F. Green synthesis of TiO2 NPs/pristine pomegranate peel extract nanocomposite and its antimicrobial activity for water disinfection. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, D.; Srinivasan, K.; Nehru, L.C. Synthesis and Characterization of TiO2 Nanoparticles Using Cynodon Dactylon Leaf Extract for Antibacterial and Anticancer (A549 Cell Lines) Activity. J. Nanomed. Res. 2017, 5, 00138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.M.; Hasanin, M.S.; Suleiman, W.B.; Helal, E.E.-H.; Hashem, A.H. Green biosynthesis of titanium dioxide quantum dots using watermelon peel waste: Antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer activities. Biomass-Convers. Biorefinery 2024,14:6987-6998. [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.G.; Ashok, C.; Rao, K.V.; Chakra, C.S.; Tambur, P. Green Synthesis of TiO2 Nanoparticles Using Aloe Vera Extract. Int. J. Adv. Res. Phys. Sci. 2015, 2, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Velayutham, K.; Rahuman, A.A.; Rajakumar, G.; Santhoshkumar, T.; Marimuthu, S.; Jayaseelan, C.; Bagavan, A.; Kirthi, A.V.; Kamaraj, C.; Zahir, A.A. Evaluation of Catharanthus Roseus Leaf Extract-mediated Biosynthesis of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles Against Hippobosca Maculata and Bovicola Ovis. Parasitol. Res. 2012, 111(6), 2329–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, K.G.; Ashok, C.; Rao, K.V.; Chakra, C.S.; Rajendar, V. Synthesis of TiO2 Nanoparticles from Orange Fruit Waste. Synthesis 2015, 2, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, N.; Soni, D.; Chandrashekhar, B.; Sarangi, B.K.; Satpute, D.; Pandey, R.A. Synthesis and Characterization of Silver Nanoparticles Using Cynodon Dactylon Leaves and Assessment of Their Antibacterial Activity. Bioproc. Biosyst. Eng. 2013, 36, 999–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajakumar, G.; Rahuman, A.A.; Priyamvada, B.; Khanna, V.G.; Kumar, D.K.; Sujin, P. Eclipta Prostrata Leaf Aqueous Extract Mediated Synthesis of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles. Mater. Lett. 2012, 68, 115–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.S.M.; Francis, A.P.; Devasena, T. Biosynthesized and Chemically Synthesized Titania Nanoparticles: Comparative Analysis of Antibacterial Activity. J. Environ. Nanotechnol 2014, 3, 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sivaranjani, V.; Philominathan, P. Synthesize of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles Using Moringa Oleifera Leaves and Evaluation of Wound Healing Activity. Wound Med. 2016, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Nishanthini, D.; Sandhiya, N.; Abraham, J. Biosynthesis of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles Using Vigna Radiata. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2016, 9, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hunagund, S.M.; Desai, V.R.; Kadadevarmath, J.S.; Barretto, D.A.; Vootla, S.; Sidarai, A.H. Biogenic and Chemogenic Synthesis of TiO2 NPs via Hydrothermal Route and Their Antibacterial Activities. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 97438–97444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreslassie, Y.T.; Gebretnsae, H.G. Green and Cost-Effective Synthesis of Tin Oxide Nanoparticles: A Review on the Synthesis Methodologies, Mechanism of Formation, and Their Potential Applications. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiris, M.; Guansekera, T.; Jayaweera, P.; Fernando, S. TiO2 nanoparticles from baker’s yeast: A potent antimicrobial. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 28, 1664–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ağçeli, G.K.; Hammachi, H.; Kodal, S.P.; Cihangir, N.; Aksu, Z. A novel approach to synthesize TiO2 nanoparticles: biosynthesis by using Streptomyces sp. HC1. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2020, 30, 3221–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniandy, S.S.; Kaus, N.H.M.; Jiang, Z.-T.; Altarawneh, M.; Lee, H.L. Green synthesis of mesoporous anatase TiO2 nanoparticles and their photocatalytic activities. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 48083–48094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, S.; Shameli, K.; Hamid, S.B.A. Synthesis and characterization of anatase titanium dioxide nanoparticles using egg white solution via sol-gel method. J. Chem. 2013, 2013, 848205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Hao, B.; Wang, X.B.; Chen, G. Bio-inspired synthesis of titania with polyamine induced morphology and phase transformation at room-temperature: Insight into the role of the protonated amino group. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 12179–12184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulmi, D.D.; Dahal, B.; Kim, H.-Y.; Nakarmi, M.L.; Panthi, G. Optical and photocatalytic properties of lysozyme mediated titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Optik 2018, 154, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Qi, W.; Su, R.; He, Z. Peptide-Templated Synthesis of TiO2 Nanofibers with Tunable Photocatalytic Activity. Chem. A Eur. J. 2018, 24, 18123–18129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Xia, Y.; Song, K.; Liu, D. The Impact of Nanomaterials on Photosynthesis and Antioxidant Mechanisms in Gramineae Plants: Research Progress and Future Prospects. Plants 2024, 13, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, D.J.; Pietrasiak, N.; Situ, S.F.; Abenojar, E.C.; Porche, M.; Kraj, P.; Lakliang, Y.; Samia, A.C.S. Iron oxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticle effects on plant performance and root associated microbes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 23630–23650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Zhuang, W.-Q.; De Costa, Y.; Xia, S. Potential effects of suspended TiO2 nanoparticles on activated sludge floc properties in membrane bioreactors. Chemosphere 2019, 223, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahi, S.M.M.; Yazdi, M.E.T.; Einafshar, E.; Akhondi, M.; Ebadi, M.; Azimipour, S.; Iranbakhsh, A. The effects of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles on physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant properties of vitex plant (Vitex agnus-Castus L). Heliyon 2023, 9, e22144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breadmore, M.C.; Wuethrich, A.; Li, F.; Phung, S.C.; Kalsoom, U.; Cabot, J.M.; Tehranirokh, M.; Shallan, A.I.; Abdul Keyon, A.S.; See, H.H.; et al. Recent advances in enhancing the sensitivity of electrophoresis and electrochromatography in capillaries and microchips (2014–2016). Electrophoresis 2017, 38, 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comotti, A.; Castiglioni, F.; Bracco, S.; Perego, J.; Pedrini, A.; Negroni, M.; Sozzani, P. Fluorinated porous organic frameworks for improved CO2 and CH4 capture. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 8999–9002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, A.; Faraji, M.; Ebrahimi, A.A.; Nemati, S.; Abdolahnejad, A.; Miri, M. Comparing THMs level in old and new water distribution systems; seasonal variation and probabilistic risk assessment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 192, 110286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahila, M.M.H.; Najy, A.M.; Rahaie, M.; Mir-Derikvand, M. Effect of nanoparticle treatment on expression of a key gene involved in thymoquinone biosynthetic pathway in Nigella sativa L. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 1858–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekkers, S.; Wagner, J.G.; Vandebriel, R.J.; Eldridge, E.A.; Tang, S.V.Y.; Miller, M.R.; Römer, I.; de Jong, W.H.; Harkema, J.R.; Cassee, F.R. Role of chemical composition and redox modification of poorly soluble nanomaterials on their ability to enhance allergic airway sensitisation in mice. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2019, 16, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Ali, S.; Rizwan, M.; Zia ur Rehman, M.; Javed, M.R.; Imran, M.; Chatha, S.A.S.; Nazir, R. Zinc oxide nanoparticles alter the wheat physiological response and reduce the cadmium uptake by plants. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 242, 1518–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, N.; Kuo, H.-H.; Boucau, J.; Farmer, J.R.; Allard-Chamard, H.; Mahajan, V.S.; Piechocka-Trocha, A.; Lefteri, K.; Osborn, M.; Bals, J.; et al. Loss of Bcl-6-Expressing T Follicular Helper Cells and Germinal Centers in COVID-19. Cell 2020, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, E.B.; Mussoline, W.A.; Wilkie, A.C.; Ma, L.Q. Anaerobic digestion to reduce biomass and remove arsenic from as-hyperaccumulator Pteris vittata. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 250, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, W.; Yang, L.; Joseph, S.; Shi, W.; Bian, R.; Zheng, J. Utilization of biochar produced from invasive plant species to efficiently adsorb Cd (II) and Pb (II). Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 317, 124011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, R.; Zahra, Z.; Virk, N.; Shahid, M.; Pinelli, E.; Park, T.J.; Kallerhoff, J.; Arshad, M. Dose-dependent physiological responses of Triticum aestivum L. to soil applied TiO2 nanoparticles: Alterations in chlorophyll content, H2O2 production, and genotoxicity. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 255, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Contador, C.A.; Fan, K.; Lam, H.M. Interaction and regulation of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus metabolisms in root nodules of legumes. Front. Plant Sci, 2018; 1, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, L.; Abdollahi, F.; Feizi, H.; Adl, S. Improved Marjoram (Origanum majorana L.) Tolerance to Salinity with Seed Priming Using Titanium Dioxide (TiO2). Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Sci. 2022, 46, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Cai, S.; Ying, W.; Niu, T.; Yan, J.; Hu, H.; Ruan, S. Exogenous titanium dioxide nanoparticles alleviate cadmium toxicity by enhancing the antioxidative capacity of Tetrastigma hemsleyanum. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safe. 2024, 273, 116166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardar, R.; Ahmed, S.; Yasin, N.A. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles mitigate cadmium toxicity in Coriandrum sativum L. through modulating antioxidant system, stress markers and reducing cadmium uptake. Environ. Pollut. 2022; 292 , 118373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Alhussaen, K.M.; El-Alosey, A.R.; AlOmrani, M.A.M.; Kalaji, H.M. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles require K+ and hydrogen sulfide to regulate nitrogen and carbohydrate metabolism during adaptive response to drought and nickel stress in cucumber. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 334, 122008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevik, S. TiO2 nanoparticles alleviates the effects of drought stress in tomato seedlings. Bragantia 2023, 82, e20220203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, P.; Yadu, B.; Korram, J.; Satnami, M.L.; Kumar, M.; Keshavkant, S. Titanium nanoparticles attenuates arsenic toxicity by up-regulating expressions of defensive genes in Vigna radiata L. J. Environ. Sci. 2020, 92, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar, S.A.; Elsheery, N.I.; Pashkovskiy, P.; Kuznetsov, V.; Allakhverdiev, S.I.; Zedan, A.M. Impact of Titanium Oxide Nanoparticles on Growth, Pigment Content, Membrane Stability, DNA Damage, and Stress-Related Gene Expression in Vicia faba under Saline Conditions. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourozi, E.; Hosseini, B.; Maleki, R.; Abdollahi Mandoulakani, B. Inductive effect of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on the anticancer compounds production and expression of rosmarinic acid biosynthesis genes in Dracocephalum kotschyi transformed roots. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 167, 934–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ma, C.; Chen, G.; White, J.C.; Wang, Z.; Xing, B.; Dhankher, O.P. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles alleviate tetracycline toxicity to Arabidopsis thaliana (L.). ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017; 5, 3204–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zou, Y.; Li, P.; Yuan, X. Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles Promote Root Growth by Interfering with Auxin Pathways in Arabidopsis thaliana. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2020; 89, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghouri, F.; Shahid, M.J.; Zhong, M.; Zia, M.A.; Alomrani, S.O.; Liu, J.; Sun, L.; Ali, S.; Liu, X.; Shahid, M.Q. Alleviated lead toxicity in rice plant by co-augmented action of genome doubling and TiO2 nanoparticles on gene expression, cytological and physiological changes. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 911, 168709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Zavala, F.G.; Atriztan-Hernandez, K.; Mart´ınez-Irastorza, P.; Oropeza-Aburto, A.; Lopez-Arredondo, D.; Herrera-Estrella, L. Titanium nanoparticles activate a transcriptional response in Arabidopsis that enhances tolerance to low phosphate, osmotic stress and pathogen infection. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 994523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Huqail, A.A.; Alghanem, S.M.S.; Alhaithloul, H.A.S.; Saleem, M.H.; Abeed, A.H.A. Combined exposure of PVC-microplastic and mercury chloride (HgCl2) in sorghum (Pennisetum glaucum L.) when its seeds are primed titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2–NPs). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024; 31, 7837–7852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiany, T.; Pishkar, L.; Sartipnia, N.; Iranbakhsh, A.; Barzin, G. Effects of silicon and titanium dioxide nanoparticles on arsenic accumulation, phytochelatin metabolism, and antioxidant system by rice under arsenic toxicity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 34725–34737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abyari, M. The effect of titanium oxide nanoparticles on the gene expression involved in the secondary metabolite production of the medicinal plant periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus). J. Crop Breed. 2023, 15(46), 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, R.; Kołodziej, K.; Ślesak, I.; Zimak-Piekarczyk, P.; Orzechowska, A.; Gabruk, M.; Zadło, A.; Habina, I.; Knap, W.; Burda, K.; et al. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (100-1000 mg/l) can affect vitamin E response in Arabidopsis thaliana. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 213, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, S.; de Oliveira, J.M.F.; Dias, M.C.; Silva, A.; Santos, C. Antioxidant mechanisms to counteract TiO2-nanoparticles toxicity in wheat leaves and roots are organ dependent. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 380, 120889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, N.; Raja, N.I.; Ilyas, N.; Ikram, M.; Mashwani, Z.U.R.; Ehsan, M. Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress. Green Process. Synth. 2021, 10, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satti, S.H.; Raja, N.I.; Javed, B.; Akram, A.; Mashwani, Z.-u.-R.; Ahmad, M.S.; Ikram, M. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles elicited agro-morphological and physicochemical modifications in wheat plants to control Bipolaris sorokiniana. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satti, S.H.; Raja, N.I.; Ikram, M.; Oraby, H.F.; Mashwani, Z.-U.-R.; Mohamed, A.H.; Singh, A.; Omar, A.A. Plant-Based Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles Trigger Biochemical and Proteome Modifications in Triticum aestivum L. under Biotic Stress of Puccinia striiformis. Molecules 2022, 27, 4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, N.; Raja, N.I.; Ilyas, N.; Abasi, F.; Ahmad, M.S.; Ehsan, M.; Mehak, A.; Badshah, I.; Proćków, J. Exogenous Application of Green Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) to Improve the Germination, Physiochemical, and Yield Parameters of Wheat Plants under Salinity Stress. Molecules 2022, 27, 4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, H.; Adarosy, M.H.; Hegazy, H.S.; Abdelhameed, R.E. Potential of green synthesized titanium dioxide nanoparticles for enhancing seedling emergence, vigor and tolerance indices and DPPH free radical scavenging in two varieties of soybean under salinity stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badshah, I.; Mustafa, N.; Khan, R.; Mashwani, Z.-u.-R.; Raja, N.I.; Almutairi, M.H.; Aleya, L.; Sayed, A.A.; Zaman, S.; Sawati, L.; et al. Biogenic Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles Ameliorate the Effect of Salinity Stress in Wheat Crop. Agronomy 2023, 13, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally, R.A.; Soliman, S.A.; Abdalla, H.; Abdelhameed, R.E. 2024. Trichoderma cf. asperellum and plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles initiate morphological and biochemical modifications in Hordeum vulgare L. against Bipolaris sorokiniana. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 118. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Mariyam, S.; Gupta, K.J.; Thiruvengadam, M.; Ghodake, G.; Xing, B.; Seth, C.S. Comparative investigation on chemical and green synthesized titanium dioxide nanoparticles against chromium (VI) stress eliciting differential physiological, biochemical, and cellular attributes in Helianthus annuus L. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 930, 172413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zomorrodi, N.; Rezaei Nejad, A.; Mousavi-Fard, S.; Feizi, H.; Tsaniklidis, G.; Fanourakis, D. Potency of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles, Sodium Hydrogen Sulfide and Salicylic Acid in Ameliorating the Depressive Effects of Water Deficit on Periwinkle Ornamental Quality. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, P.T.; Ngoc, D.B.; Khang, D.T. Effects of Titanium Dioxide nanoparticles on salinity tolerance of rice (Oryza sativa L.) at the seedling stage. CTU Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development, 2023, 15, 60–67. [CrossRef]

- Jahan, A.; Khan, M.M.A.; Ahmad, B.; Ahmed, K.B.M.; Sadiq, Y.; Gulfishan, M. Influence of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on growth, physiological attributes and essential oil production of Mentha arvensis L. Braz. J. Bot. 2023, 46, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, R.; Harlina, P.W.; Khan, S.U.; Ihtisham, M.; Khan, A.H.; Husain, F.M.; Karuniawan, A. Physio-biochemical and transcriptomics analyses reveal molecular mechanisms of enhanced UV-B stress tolerance in rice induced by titanium dioxide nanoparticles. J. Plant Interact. 2024, 19, 2328713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hozzein, W.N.; Al-Khalaf, A.A.; Mohany, M.; Ahmed, O.M.; Amin, A.A.; Alharbi, H.M. Efficacy of two actinomycete extracts in the amelioration of carbon tetrachloride–induced oxidative stress and nephrotoxicity in experimental rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 24010–24019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, M.B.; Niazi, N.K.; Bibi, I.; Shahid, M.; Sharif, F.; Bashir, S.; Rinklebe, J. Arsenic removal by natural and chemically modified watermelon rind in aqueous solutions and groundwater. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 1444–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jyoti, J.; Kaur, R.; Sharma, J.; Tripathi, S.K. Synthesis and characterization of TiO2 nanoparticles for memory device application. AIP Conf. Proc. 2020, 2220, 020056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghapour, M.; Binaeian, E.; Pirzaman, A.K. Synthesis and surface modification of hexagonal mesoporous silicate–HMS using chitosan for the adsorption of DY86 from aqueous solution. J. Water Wastewater. 2019, 30, 86–100. [Google Scholar]

- Edmiston, P.L.; Gilbert, A.R.; Harvey, Z.; Mellor, N. Adsorption of short chain carboxylic acids from aqueous solution by swellable organically modified silica materials. Adsorption 2018, 24, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamedani, G.G.; Rasekhi, M.; Najibi, S.M.; Yousof, H.M.; Alizadeh, M. Type II general exponential class of distributions. Pak. J. Stat. Oper. Res. 2019, XV, 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Lei, H.; Luo, Y.; Huan, C.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Sun, A. The effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on cadmium bioaccumulation in ramie and its application in remediation of cadmium-contaminated soil. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 86, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikandan, V.; Velmurugan, P.; Jayanthi, P.; Park, J.H.; Chang, W.S.; Park, Y.J.; Cho, M.; Oh, B.T. Biogenic synthesis from Prunus × yedoensis leaf extract, characterization, and photocatalytic and antibacterial activity of TiO2 nanoparticles. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2018, 44, 2489–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goutam, S.P.; Saxena, G.; Singh, V.; Yadav, A.K.; Bharagava, R.N.; Thapa, K.B. Green synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles using leaf extract of Jatropha curcas L. for photocatalytic degradation of tannery wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 336, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, G.M.; Fan, H.; Tian, H. Room-temperature solid state synthesis of Co3O4/ZnO p–n heterostructure and its photocatalytic activity. Adv. Powder Technol. 2017, 28, 953–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhoshkumar, T.; Rahuman, A.A.; Jayaseelan, C.; Rajakumar, G.; Marimuthu, S.; Kirthi, A.V.; Velayutham, K.; Thomas, J.; Venkatesan, J.; Kim, S.-K. Green synthesis of titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Psidium guajava extract and its antibacterial and antioxidant properties. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2014, 7, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marimuthu, S.; Rahuman, A.A.; Jayaseelan, C.; Kirthi, A.V.; Santhoshkumar, T.; Velayutham, K.; Bagavan, A.; Kamaraj, C.; Elango, G.; Iyappan, M.; et al. Acaricidal activity of synthesized titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Calotropis gigantea against Rhipicephalus microplus and Haemaphysalis bispinosa. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2013, 6, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, A.; Khan, M.T.; Mehmood, M.; Khurshid, Z.; Ali, M.I.; Jamal, A. Synthesis and Characterization of Titanium Oxide Nanoparticles with a Novel Biogenic Process for Dental Application. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albukhaty, S.; Al-Bayati, L.; Al-Karagoly, H.; Al-Musawi, S. Preparation and characterization of titanium dioxide nanoparticles and in vitro investigation of their cytotoxicity and antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Anim. Biotechnol 2022, 33, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhan, J.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, N.; Kaur, P.; Nehra, K.; Duhan, S. Nanotechnology: the new perspective in precision agriculture. Biotechnol. Rep. 2017, 15, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmer, W.; White, J.C. The future of nanotechnology in plant pathology. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2018, 56, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, R. Nanofertilizer and Nanotechnology: A quick look. Better Crops Plant Food 2018, 102, 18–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohari, G.; Mohammadi, A.; Akbari, A.; Panahirad, S.; Dadpour, M.R.; Fotopoulos, V.; Kimura, S. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) promote growth and ameliorate salinity stress effects on essential oil profile and biochemical attributes of Dracocephalum moldavica. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raliya, R.; Franke, C.; Chavalmane, S.; Nair, R.; Reed, N.; Biswas, P. Quantitative understanding of nanoparticle uptake in watermelon plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaphle, A.; Navya, P.; Umapathi, A.; Daima, H.K. Nanomaterials for agriculture, food and environment: applications, toxicity and regulation. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2018, 16, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Interaction of titanium dioxide nanoparticles with soil components and plants: Current knowledge and future research needs—A critical review. Environ. Sci. Nano 2018, 5, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Hua, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Saleem, M.H.; Zulfiqar, F.; Chen, F.; Abbas, T.; El-Sheikh, M.A.; Yong, J.W.H.; Adil, M.F. Interaction of titanium dioxide nanoparticles with PVC-microplastics and chromium counteracts oxidative injuries in Trachyspermum ammi L. by modulating antioxidants and gene expression. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safe. 2024, 274, 116181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, D.; Dhankher, O.P.; Tripathi, R.D.; Seth, C.S. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles potentially regulate the mechanism (s) for photosynthetic attributes, genotoxicity, antioxidants defense machinery, and phytochelatins synthesis in relation to hexavalent chromium toxicity in Helianthus annuus L. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 454, 131418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skiba, E.; Pietrzak, M.; Michlewska, S.; Gruszka, J.; Malejko, J.; Godlewska-Żyłkiewicz, B.; Wolf, W.M. , Photosynthesis governed by nanoparticulate titanium dioxide. The Pisum sativum L. case study. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 340, 122735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, S.; Alias, Y.B.; Bakar, A.F.B.A.; Yusoff, I.B. Toxicity evaluation of ZnO and TiO2 nanomaterials in hydroponic red bean (Vigna angularis) plant: physiology, biochemistry and kinetic transport. J. Environ. Sci. 2018, 72, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Adeel, M.; Zain, M.; Rizwan, M.; Irshad, M.K.; Jilani, G. Physiological and biochemical response of wheat (Triticum aestivum) to TiO2 nanoparticles in phosphorous amended soil: a full life cycle study. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 263, 110365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, H.; Esmailpour, M.; Gheranpaye, A. Effects of TiO2 nanoparticles and water-deficit stress on morpho-physiological characteristics of dragonhead (Dracocephalum moldavica L.) plants. Acta Agric. Slov. 2016, 107, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghabel, V.K.; Karamian, R. Effects of TiO2 nanoparticles and spermine on antioxidant responses of Glycyrrhiza glabra L. to cold stress. Acta Bot. Croat. 2020, 79, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Liu, H.; Chen, G.; Zhao, Q.; Eitzer, B.; Wang, Z.; Cai, W.; Newman, L.A.; White, J.C.; Dhankher, O.P.; et al. Effects of titanium oxide nanoparticles on tetracycline accumulation and toxicity in Oryza sativa (L.). Environ. Sci. Nano 2017, 4, 1827–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunkunle, C.O.; Odulaja, D.A.; Akande, F.O.; Varun, M.; Vishwakarma, V.; Fatoba, P.O. Cadmium toxicity in cowpea plant: Effect of foliar intervention of nano-TiO2 on tissue Cd bioaccumulation, stress enzymes and potential dietary health risk. J. Biotechnol. 2020, 310, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S.; Wei, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Pan, D. Titanium as a beneficial element for crop production. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Raza, A.; Hashem, A.; Dolores Avila-Quezada, G.; Fathi Abd_Allah, E.; Ahmad, F.; Ahmad, A. Green fabrication of titanium dioxide nanoparticles via Syzygium cumini leaves extract: characterizations, photocatalytic activity and nematicidal evaluation. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2024, 17, 2331063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahardoli, A.; Sharifan, H.; Karimi, N.; Shiva Najafi Kakavand, S.N. Uptake, translocation, phytotoxicity, and hormetic effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2NPs) in Nigella arvensis L. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 151222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonin, M.; Richaume, A.; Guyonnet, J.P.; Dubost, A.; Martins, J.M.F.; Pommier, T. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles strongly impact soil microbial function by affecting archaeal nitrifiers. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.; Venkatachalam, P.; Sahi, S.; Sharma, N. Reprint of: Silver and titanium dioxide nanoparticle toxicity in plants: A review of current research. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 110, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demir, E.; Kaya, N.; Kaya, B. Genotoxic effects of zinc oxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles on root meristem cells of Allium cepa by comet assay. Turk. J. Biol. 2014, 38, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.; Bandyopadhyay, M.; Mukherjee, A. Genotoxicity of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles at two trophic levels: plant and human lymphocytes. Chemosphere 2010, 81, 1253–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tianyi, W.; Haitao, J.; Long, W.; Qinfu, Z.; Tongying, J.; Bing, W.; Siling, W. Potential application of functional porous TiO2 nanoparticles in light-controlled drug release and targeted drug delivery. Acta Biomater. 2015, 13, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakrashi, S.; Jain, N.; Dalai, S.; Jayakumar, J.; Chandrasekaran, P.T.; Raichur, A.M.; Chandrasekaran, N.; Mukherjee, A. In vivo genotoxicity assessment of titanium dioxide nanoparticles by Allium cepa root tip assay at high exposure concentrations. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellmann, S.; Eichert, T. Acute Effects of Engineered Nanoparticles on the Growth and Gas Exchange of Zea mays L.—What are the Underlying Causes? Water Air Soil Pollut. 2017, 228, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kořenková, L.; Šebesta, M.; Urík, M.; Kolenčík, M.; Kratošová, G.; Bujdoš, M.; Vávra, I.; Dobročka, E. Physiological response of culture media-grown barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) to titanium oxide nanoparticles. Acta Agric. Scand. 2017, 67, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, E.A.; Patil, R.P.; Mane, C.B.; Sanaei, D.; Asiri, F.; Seo, S.S.; Sharifan, H. Environmental exposure and nanotoxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in irrigation water with the flavonoid luteolin. RSC Advances 2023, 13, 14110–14118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Rosa, S.; Pérez-Reyes, O. Titanium Oxide Nanoparticles as Emerging Aquatic Pollutants: An Evaluation of the Nanotoxicity in the Freshwater Shrimp Larvae Atya lanipes. Ecologies 2023, 4, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghareeb, S.; Ragheb, D.; El-Sheakh, A.; Ashour, M.-B.A. Potential Toxic Effects of Exposure to Titanium Silicon Oxide Nanoparticles in Male Rats. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, Y.; Li, H. Toxicity of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles on the Histology, Liver Physiological and Metabolism, and Intestinal Microbiota of Grouper. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 187, 114600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Xie, H. Nanoparticles in Daily Life: Applications, Toxicity and Regulations. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 2018, 37, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadi, S., Serpooshan, V., Tao, W., Hamaly, M.A., Alkawareek, M.Y., Dreaden, E.C., Brown, D., Alkilany, A.M., Farokhzad, O.C., Mahmoudi, M. Cellular uptake of nanoparticles: journey inside the cell. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 4218–4244. [CrossRef]

- Maurer-Jones, M.A.; Gunsolus, I.L.; Murphy, C.J.; Haynes, C.L. Toxicity of engineered nanoparticles in the environment. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 3036–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samrot, A.V.; Saipriya, C.; Agnes, L.A.; Roshini, S.M.; Cypriyana, J.; Saigeetha, S.; Raji, P.; Kumar, S. Evaluation of nanotoxicity of Araucaria heterophylla gum derived green synthesized silver nanoparticles on Eudrilus eugeniae and Danio rerio. J. Clust. Sci. 2019, 30, 1017–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vankayala, R.; Kuo, C.-L.; Sagadevan, A.; Chen, P.-H.; Chiang, C.-S.; Hwang, K.C. Morphology dependent photosensitization and formation of singlet oxygen (1 Δ g) by gold and silver nanoparticles and its application in cancer treatment. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 4379–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.M.; Forte Tavčer, P.; Tomšič, B. Influence of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles on Human Health and the Environment. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, S.C.; Zheng, J.; Graham, L.; Chen, L.; Ihrie, J.; Yourick, J.J.; Sprando, R.L. Comparative cytotoxicity of nanosilver in human liver HepG2 and colon Caco2 cells in culture. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2014, 34, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wang, L.; Fan, Y.; Feng, Q.; Cui, F. Biocompatibility and Toxicity of Nanoparticles and Nanotubes. J. Nanomater. 2012, 2012, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaebuddin, S.K.; Thevenot, P.T.; Baker, D.; Eaton, J.W.; Tang, L. Nanomaterial cytotoxicity is composition, size, and cell type dependent. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2010, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, H.K.; Banerjee, S.; Chaudhuri, U.; Lahiri, P.; Dasgupta, A.K. Cell selective response to gold nanoparticles. Nanomedicine 2007, 3, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiewe, M.H.; Hawk, E.G.; Actor, D.I.; Krahn, M.M. Use of a bacterial bioluminescence assay to assess toxicity of contaminated marine sediments. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1985, 42, 1244–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Yan, D.; Yin, G.; Liao, X.; Kang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Huang, D.; Hao, B. Toxicological effect of ZnO nanoparticles based on bacteria. Langmuir 2008, 24, 4140–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, W.; Arghya, P.; Yiyong, M.; Rodes, L.; Prakash, L.R.A.S. Carbon Nanotubes for Use in Medicine: Potentials and Limitations. Synth. Appl. Carbon Nanotub. Their Compos. 2013, 13, 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengul, A.B.; Asmatulu, E. Toxicity of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 1659–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaye, N.; Thwala, M.; Cowan, D.A.; Musee, N. Genotoxicity of metal based engineered nanoparticles in aquatic organisms: A review. Mutat. Res. 2017, 773, 134–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Gao, F.; Lan, M.; Yuan, H.; Huang, Y.; Liu, J. Oxidative stress contributes to silica nanoparticle-induced cytotoxicity in human embryonic kidney cells. Toxicol. In Vitro 2009, 23, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizochenko, N.; Syzochenko, M.; Fjodorova, N.; Rasulev, B.; Leszczynski, J. Evaluating genotoxicity of metal oxide nanoparticles: Application of advanced supervised and unsupervised machine learning techniques. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 185, 109733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrian, S.K.; De Lima, R. Nanoparticles cyto and genotoxicity in plants: mechanisms and abnormalities. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2016, 6, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdolenova, Z.; Collins, A.; Kumar, A.; Dhawan, A.; Stone, V.; Dusinska, M. Mechanisms of genotoxicity. A review of invitro and in-vivo studies with engineered nanoparticles. Nanotoxicology, 2014, 8, 233–278. [CrossRef]

- Egbuna, C.; Parmar, V.K.; Jeevanandam, J.; Ezzat, S.M.; Patrick-Iwuanyanwu, K.C.; Adetunji, C.O.; Khan, J.; Onyeike, E.N.; Uche, C.Z.; Akram, M.; et al. Toxicity of Nanoparticles in Biomedical Application: Nanotoxicology. J. Toxicol. 2021, 2021, 9954443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boverhof, D.R.; Bramante, C.M.; Butala, J.H.; Clancy, S.F.; Lafranconi, M.; West, J.; Gordon, S.C. Comparative assessment of nanomaterial definitions and safety evaluation considerations. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015, 73, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, J.; Karthickraja, R.; Vignesh, J. Nanowaste. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2017, 8, 483–491. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, P.; Ong, C.; Bay, B.H.; Baeg, G.H. Nanotoxicity: An Interplay of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Cell Death. Nanomaterials 2015, 5, 1163–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živković, D.; Balanović, L.; Mitovski, A.; Talijan, N.; Štrbac, N.; Sokić, M.; Manasijević, D.; Minić, D.; Ćosović, V. Nanomaterials Environmental Risks and Recycling: Actual Issues. Reciklaza I Odrziv. Razvoj 2015, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.L.; Kiyohara, P.K.; Rossi, L.M. High performance magnetic separation of gold nanoparticles for catalytic oxidation of alcohols. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.; Christensen, F.M.; Nielsen, J.M. (Eds.). Nanomaterials in Waste: Issues and New Knowledge. Danish Ministry of the Environment, Environmental Protection Agency. 2014.

- OECD. Nanomaterials in Waste Streams: Current Knowledge on Risks and Impacts; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016; ISBN 9789264240612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, T.-J.; Lee, W.; Oh, Y.-S.; Lee, J.-K. Magnetic nanoparticles as a catalyst vehicle for simple and easy recycling. New J. Chem. 2003, 27, 227–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazar, M.F.; Shah, S.S.; Eastoe, J.; Khan, A.M.; Shah, A. Separation and recycling of nanoparticles using cloud point extraction with non-ionic surfactant mixtures. J. Colloid Interface Sci 2011, 363, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mdlovu, N.V.; Chiang, C.; Lin, K.; Jeng, R. Recycling copper nanoparticles from printed circuit board waste etchants via a microemulsion process. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cypriyana, P.J.J.; Saigeetha, S.; Samrot, A.V.; Ponniah, P.; Chakravarthi, S. Overview on toxicity of nanoparticles, it’s mechanism, models used in toxicity studies and disposal methods–A review. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 36, 102117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, A.L.; Vejerano, E.P.; Zhou, X.; Marr, L.C. Nanomaterial disposal by incineration. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2013, 15, 1652–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, N.C.; Buha, J.; Wang, J.; Ulrich, A.; Nowack, B. Modeling the flows of engineered nanomaterials during waste handling. Environ. Sci. Process. Impact. 2013, 15, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldrin, A.; Heggelund, L.; Hundebøll, N.; Hansen, S.F. Guidelines for Safe Handling of Waste Flows Containing NOAA. Deliverable Report 7.6 for the EU-FP7 Project “SUN– Sustainable Nanotechnologies”, Grant Agreement Number 604305. 2016. [CrossRef]

| Plant species | Plant parts | Morphological shape | Size of the particles | Characterization of titanium dioxide nanoparticle | References |

| Aloe vera (L.) | leaf | Irregular shape | 60nm | UV, PSA, XRD, TEM and TGA | [40] |

| Catharanthus | leaf | Cluster form | 25nm | SEM, XRD and FTIR | [41] |

| Citrus sinensis | Peel | Tetragonal shape | 19nm | PSA, XRD, TEM and TGA | [42] |

| Cynodon dactylon | leaf | Hexagonal shape | 13-34nm | SEM, XRD and FTIR | [43] |

| Eclipta prostrate | leaf | Spherical shape | 36-68nm | AFM, FTIR, FESEM and XRD | [44] |

| Hibiscus rosa-sinensis | Flower | Spherical shape | - | SEM, XRD and FTIR | [45] |

| Moringa oleifera | leaf | Spherical shape | 100nm | SEM and UV | [46] |

| Vigna radiate | Legume | Oval shape | - | FTIR and SEM | [47] |

| Piper betle | leaf | Spherical | 7nm | XRD, SEM, UV and FTIR | [48] |

| TiNPs source | size | Concentration | Effect | Gene expression | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Green |

53.18 nm 64.28 nm |

0.25% 0.1% |

Reduced arsenic toxicity in Vigna radiata. | Up-regulated SOD and CAT. | [77] |

| Rhawn Company | 5–10 nm | 10 or 20 ppm | Mitigated the harmful effects of salinity in Vicia faba. | Up-regulated heat shock protein (HSP17.9 and HSP70) genes. | [78] |

| Nanosany Company |

20 nm | 10, 20, 30 or 50 ppm | Enhanced the rosmarinic acid content in Dracocephalum kotschyi transformed roots. | Up-regulated phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (pal) and rosmarinic acid synthase (ras) genes. | [79] |

| US Research Nanomaterials, Inc. |

5–15 nm | 50, 100, or 200 ppm | Alleviated tetracycline toxicity in Arabidopsis thaliana. | Up-regulated adenylytransferase (APT), adenosine-5′-phosphosulfate reductase (APR), and sulfite reductase (SiR). | [80] |

| Macklin Co. | >20 nm | 100, 250, 500 or 1000 ppm | Promoted root growth in Arabidopsis. | Up-regulated auxin biosynthesis (YUC8), transport (PIN2) and signaling (TIR1) related genes. | [81] |

| Shanghai Chaowei Nanotechnology Co., Ltd. | 70–90 nm | 15 ppm | Alleviated lead (Pb) toxicity in rice. | Down-regulated metal transporters such as OsHMA9, OsNRAMP5, and OsHMA6. | [82] |

| Sigma-Aldrich | 21 nm | 0.1–8 mM | Enhanced resistance to Botrytis cinerea infection, drought and salt stresses in Arabidopsis. | Activated the expression of genes involved in ROS detoxification/signaling, abscisic acid, and salicylic acid signaling pathways. | [83] |

| The source is not mentioned. | 30–80 nm | 5 ppm | Alleviated cadmium toxicity in Tetrastigma hemsleyanum. | Down-regulated Cd transporter genes (HMA2 and Nramp5). | [73] |

| Sigma-Aldrich | <100 nm | 50 or 100 µg/ml | Alleviated PVC–microplastics + mercury toxicity in Pennisetum glaucum. | Upregulated antioxidant enzymes (APX, CAT, POD, and SOD) genes expressions. | [84] |

| USA-Nano | 20–30-nm | 25 or 50 ppm | Alleviated arsenic toxicity in Oryza sativa. | Down-regulated GSH1, PCS, and ABC1 genes. | [85] |

| Sigma | 25 nm | 50 or 100 ppm | Increased indole alkaloids content in Catharanthus roseus. | Up-regulated STR, SGD, DAT, and PRX. | [86] |

| Sigma-Aldrich | >20 nm | 100–1000 µg/ml | Increased tocochromanol content in Arabidopsis thaliana. | Up-regulated 2-methyl-6-phytylbenzoquinone methyltransferase (vte5). | [87] |

| Sigma Aldrich | 21 nm | 5, 50 or 150 ppm | Reduced shoot growth of Triticum aestivum. | Up-regulated SOD. | [88] |

| TiNPs source | size | Concentration | Effect | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green | 30–111 nm | 20, 40, 60 or 80 ppm | Mitigated the harmful effects of salinity in Triticum aestivum. | Not reported. | [89] |

| Green | 10–100 nm | 20, 40, 60 or 80 ppm | Reduced the severity of spot blotch disease in Triticum aestivum. | Altered agro-morphological characteristics, chlorophyll content, membrane stability, relative water content, and non-enzymatic metabolites. | [90] |

| Green | <100 nm | 20, 40, 60 or 80 ppm | Reduced the severity of yellow stripe rust disease in Triticum aestivum. | Altered enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants. Upregulated stress-related proteins. | [91] |

| Green | 30–95 nm. | 20, 40, 60 or 80 ppm | Under salinity stress, enhanced seed germination, metabolites content, and yield in Triticum aestivum. | Enhanced SOD activity and decreased MDA content. | [92] |

| Green | 10–25 nm | 30 or 50 ppm | Under salinity stress, enhanced seed germination in Glycine max. | Decreased H2O2 and MDA content. | [93] |

| Green | 25–110 nm | 25, 50, 75, or 100 µg/ml | Under salinity stress, enhanced seed germination and seedling growth in Triticum aestivum. | Enhanced activities of POD and SOD and increased free amino acids and proline contents. | [94] |

| Green | 10–25 nm | 50 ppm | Improved tolerance against spot blotch disease in barley. | Enhanced chlorophyll content, CAT, POX, and PAL activities, and decreased content of H2O2 and MDA. | [95] |

| Green Sigma-Aldrich |

8–30 nm 15 nm |

15, 30 or 60 ppm | Green TiNP was better than Sigma-Aldrich TiNP in mitigating Cr (VI) toxicity in Helianthus annuus. | Improved photosynthetic efficiency and antioxidant enzyme activity, decreased oxidative indicators, and modified the AsA-GSH cycle's functionality. | [96] |

| Iranian Nanomaterial Pioneers Company | 15–20 nm | 0.5 or 1.0 mM | Improved ornamental quality of Catharanthus roseus under drought. | Enhanced carotenoid content, CAT and POD activities, and reduced MDA content. | [97] |

| Thermo Fisher Scientific | 32 nm | 100 ppm | Improved drought tolerance in Lycopersicon esculentum. | Decreased contents of proline and MDA and enhanced photosynthesis-related proteins, plasma membrane intrinsic protein, and relative water contents. |

[76] |

| Degussa GmbH Company | 21 nm | 20, 40 or 80 ppm | Improved growth characteristics of Origanum majorana under salinity stress. | Enhanced free radical scavenging activity. | [72] |

| XFNano company |

15–25 nm |

25, 50, 75 or 100 ppm | Improved salinity tolerance in rice. | Increased CAT and POD activities. | [98] |

| Aligarh Muslim University | 22 nm | 50, 100, 150 or 200 ppm | Enhanced growth and essential oil content in Mentha arvensis. | Enhanced photosynthesis, carbonic anhydrase, and nitrate reductase activities. | [99] |

| Sigma-Aldrich | 21 nm | 15 ppm | Improve drought and Ni stress tolerance in Cucumis sativus. | Enhanced biosynthesis of potassium, hydrogen sulfide and antioxidant (CAT, POX and SOD) enzymes. | [75] |

| Sigma-Aldrich | 21 nm | 100 ppm | Enhanced UV-B stress tolerance in Oryza sativa. | Regulates varied biological and metabolic pathways. | [100] |

| Sigma-Aldrich | <100 nm | 40, 80 or 160 ppm | Mitigated the harmful effects of Cd stress and enhanced the yield of Coriandrum sativum. | Enhanced the content of proline and antioxidative (APX, CAT, GPX, and SOD) enzyme activities. | [74] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).