Submitted:

18 September 2024

Posted:

19 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

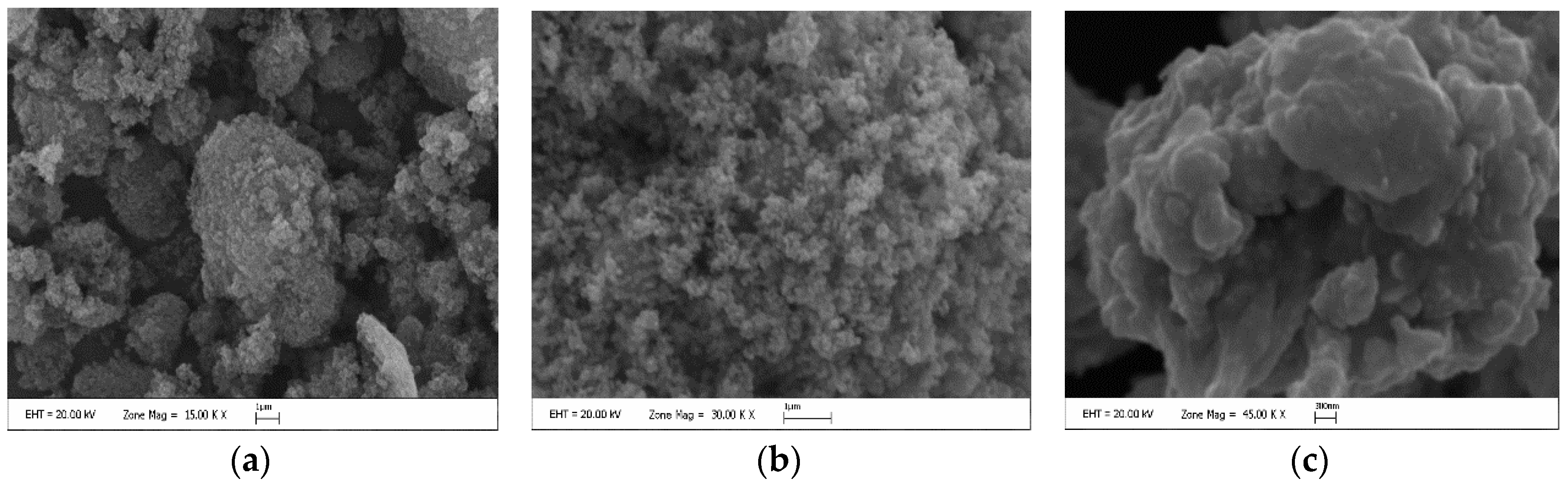

2.1. Materials

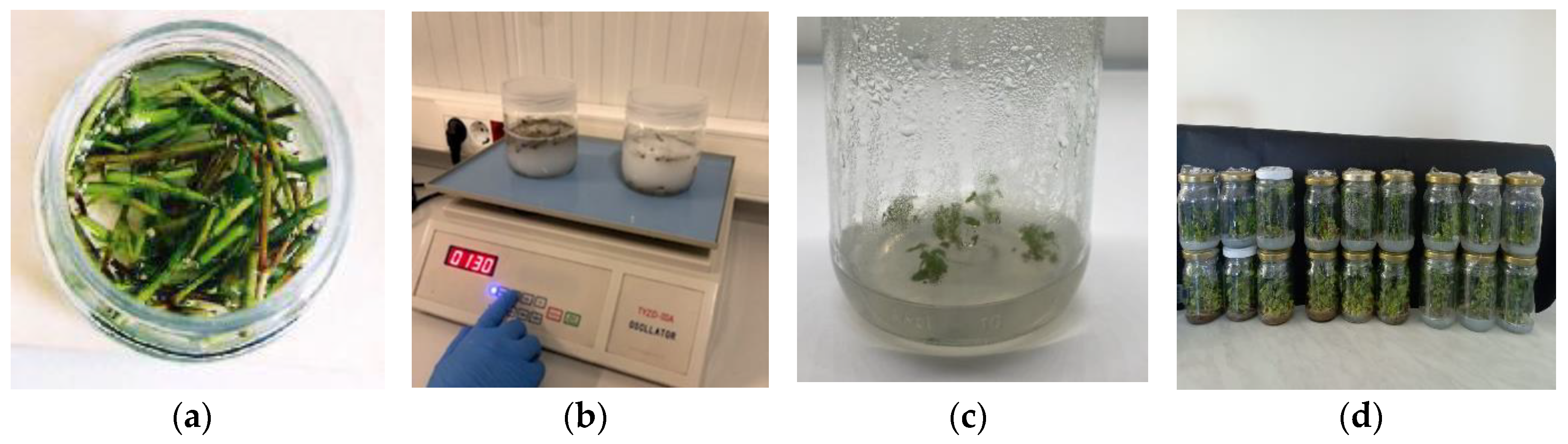

2.2. Method

2.2.1. NP Applications

2.2.2. Morphological Parameters

2.2.3. Physiological Parameters

2.2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

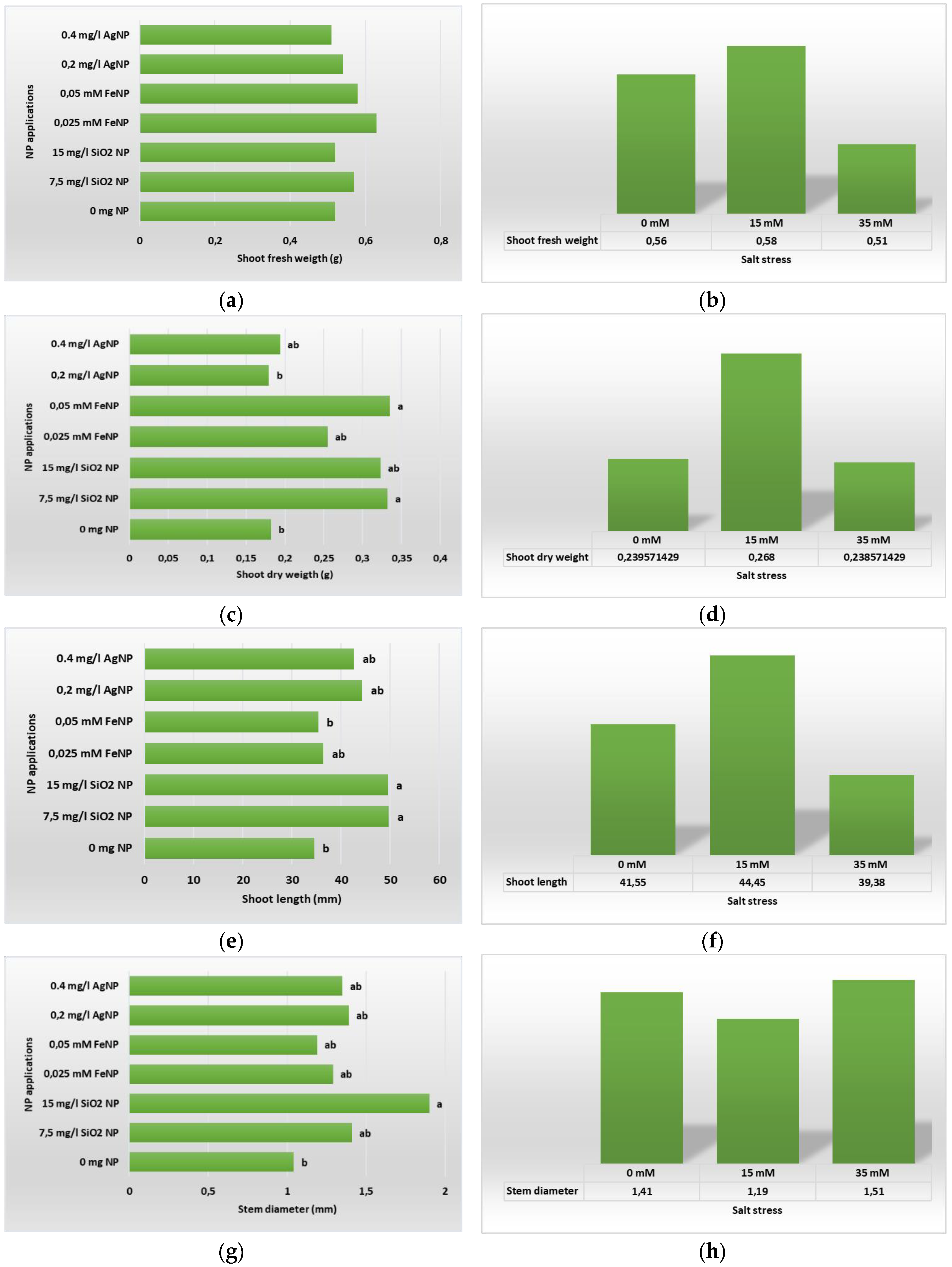

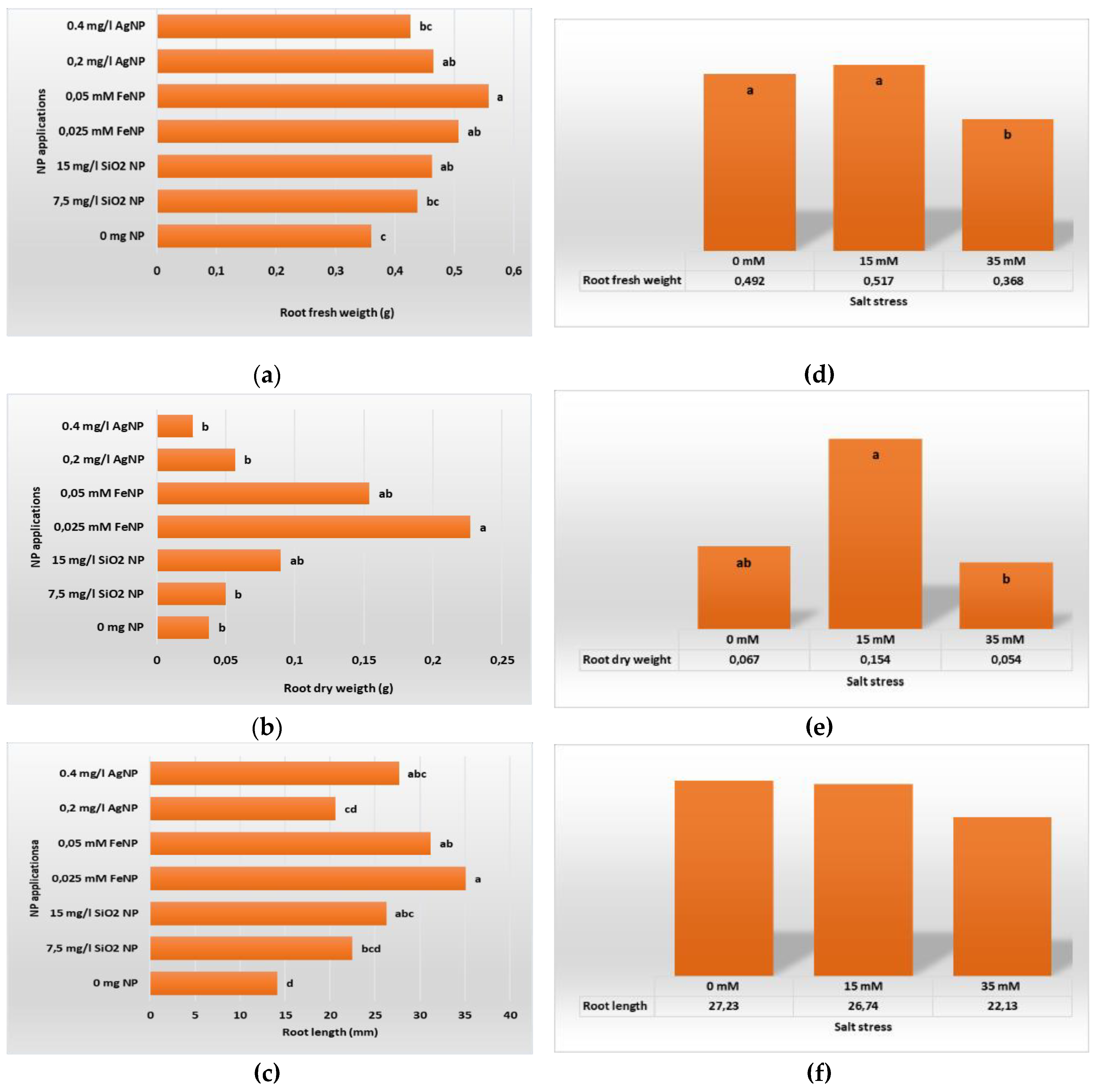

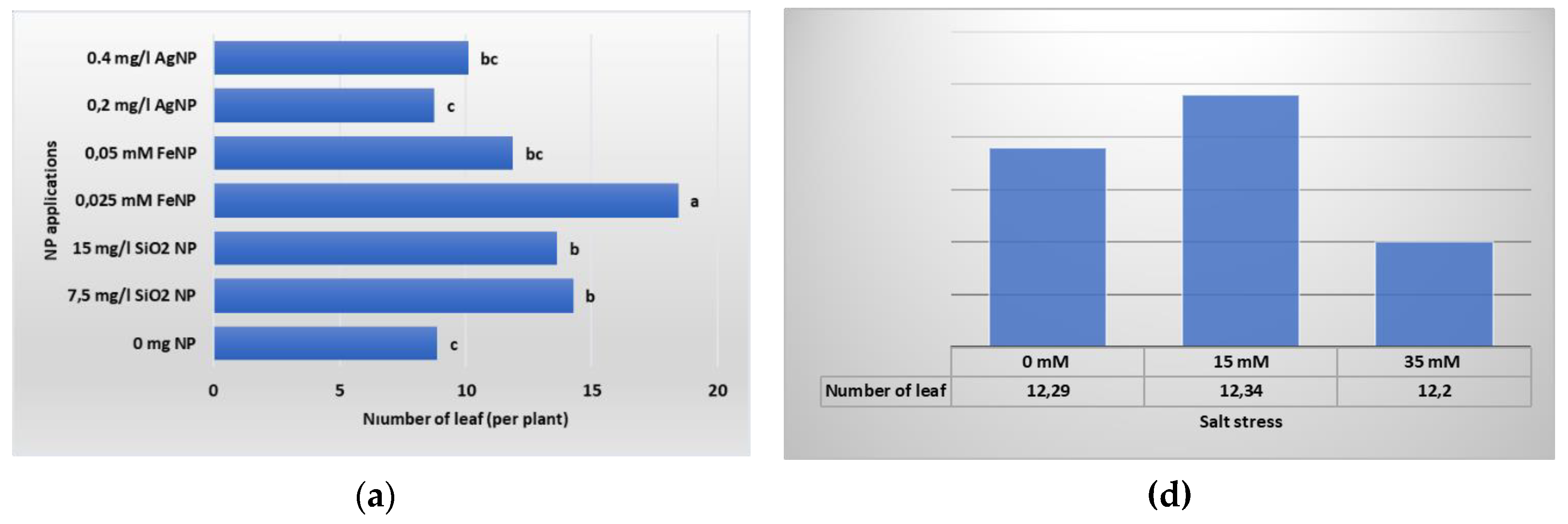

3.1. Morphological

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hummer, K.E.; Janick, J. Rubus iconography: Antiquity to the renaissance. Acta Hort. 2007, 759, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Gangrade, T.; Punasiya, R.; Ghulaxe, C. Rubus fruticosus (blackberry) use as an herbal medicine. G.R.Y. Institute of Pharmacy, "Vidhya Vihar" Borawan, Khargone, Madhya Pradesh, India. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Zia-Ul-Haq, M.; Riaz, M.; de Feo, V.; Jaafar, H.; Moga, M. Rubus fruticosus L.: Constituents, biological activities and health related uses. Molecules 2014, 19, 10998–11029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruner, L.A.; Kornilov, B.B. Priority trends and prospects of blackberry breeding in conditions of Central Russia. Vavilovskii Zhurnal Genet Selektsii. 2020, 24, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, H.K.; Langford, G. The'Boysenberry': development of the cultivar and industries in California, Oregon and New Zealand. In IX International Rubus and Ribes Symposium. 2005, 777, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcı, G.; Keles, H. Bazı böğürtlen çeşitlerinin yozgat ekolojisinde adaptasyon yeteneklerinin belirlenmesi. Adnan Menderes Üniversitesi Ziraat Fakültesi Dergisi. 2019, 16, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, W.A.; Gutiérrez, J.S.; Monsalve, O.I.; Bonilla, C.R. Salinity effect on the vegetative growth of Andean blackberry plants (Rubus glaucus Benth.) inoculated and non-inoculated with mycorrhizal fungi. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Hortícolas. 2017, 11, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Jimenez, S.L.; Castillo-Gonzalez, A.M.; del Rosario Garcia-Mateos, M.; Valdez-Aguilar, L.A.; Ybarra-Moncada, C.; Avitia-Garcia, E. Response of blackberry (Rubus spp.) Cv. tupy to salinity. Revısta Fıtotecnıa Mexıcana. 2020, 43, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R.; Tester, M. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 2008, 59, 651–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, B.S.; Appels, R.; Botha-Oberholster, A.-M.; Buell, C.R.; Bennetzen, J.L.; Chalhoub, B.; Chumley, F.; Dvorak, J.; Iwanaga, M.; Keller, B.; Li, W.; McCombie, W.R.; Ogihara, Y.; Quetier, F.; Sasaki, T. A Workshop report on wheat genome sequencing: international genome research on wheat consortium. Genetics. 2004, 168, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-K. Plant Salt Stress. In eLS, (Ed.). 2007. [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Astorga, G.I.; Alcaraz-Melendez, L. Salinity effects on protein content, lipid peroxidation, pigments, and proline in Paulownia imperialis (Siebold & Zuccarini) and Paulownia fortunei (Seemann & Hemsley) grown in vitro. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology. 2010, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agastian, P.; Kingsley, S.J.; Vivekanandan, M. Effect of salinity on photosynthesis and biochemical characteristics in Mulberry genotypes. Photosynthetica. 2000, 38, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannachi, S.; Steppe, K.; Eloudi, M.; Mechi, L.; Bahrini, I.; Van Labeke, M.-C. Salt Stress induced changes in photosynthesis and metabolic profiles of one tolerant (‘Bonica’) and one sensitive (‘Black Beauty’) eggplant cultivars (Solanum melongena L.). Plants. 2022, 11, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, M.; Foolad, M.R. Improving plant abiotic-stress resistance by exogenous application of osmoprotectants glycinebetaine and proline. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 2007, 59, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Zhu, J.K. Molecular and genetic aspects of plant responses to osmotic stress. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2007, 25, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, R.S.; Mesquita, R.O.; Freitas, N.S.; Prisco, J.T.; Filho, E.G. Nitrate: ammonium nutrition alleviates detrimental effects of salinity by enhancing photosystem II efficiency in sorghum plants. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental, 2014; ISSN 1807-1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.; Suzuki, N.; Ciftci-Yilmaz, S.; Mittler, R. Reactive oxygen species homeostasis and signalling during drought and salinity stresses. Plant and Cell Environment. 2009, 33, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marček, T.; Velić, D.; Sabo, M.; Dugalić, K.; Velić, N.; Pranjić, A.; Klarić, I.; et al. Salinity effects on blackberry plants (Rubus fructicosus L.) grown in vitro. In 8th International Scientific/Professional Conference, Agriculture in Nature and Environment Protection, Vukovar, Croatia. 2015, 298-302. Croatian Soil Tillage Research Organization (CROSTRO). Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20173162760 (accessed on 09 March 2023).

- Deliboran, A.; Savran, Ş. Toprak tuzluluğu ve tuzluluğa bitkilerin dayanım mekanizmaları. Türk Bilimsel Derlemeler Dergisi. 2015, 1, 57–61. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/derleme/issue/35094/389309 (accessed on 09 March 2023).

- Winicov, I. Characterization of rice (Oryza sativa L.) plants regenerated from salt tolerant cell lines. Plant Science, 1996, 113, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadiji, A.E.; Mthiyane, D.M.N.; Onwudiwe, D.C.; Babalola, O.O. Harnessing the known and unknown impact of nanotechnology on enhancing food security and reducing postharvest losses: constraints and future prospects. Agronomy. 2022, 12, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.T. Probing the nanoscale architecture of clay minerals. Clay Minerals. 2010, 45, 245–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, N.A.; Gill, S.S.; Duarte, A.C.; Pereira, E.; Ahmad, I. Silver nanoparticles in soil–plant systems. Journal of Nanoparticle Research. 2013, 15, 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfani, M.; Firouzabadi, M.B.; Farrokhi, N.; Makarian, H. Some physiological responses of black-eyed pea to iron and magnesium nanofertilizers. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2014, 45, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudi, M.; Daniel Ruan, H.; Wang, L.; Lyu, J.; Sadler, R.; Connell, D.; Chu, C.; Phung, D.T. Agriculture development, pesticide application and its impact on the environment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şener, S.; Sayğı, H. The role of silver nanoparticles in response of in vitro boysenberry plants to drought stress. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocsoy, I.; Paret, M.L.; Ocsoy, M.A.; Kunwar, S.; Chen, T.; You, M.; Tan, W. Nanotechnology in plant disease management: DNA-directed silver nanoparticles on graphene oxide as an antibacterial against Xanthomonas perforans. Acs Nano. 2013, 7, 8972–8980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almutairi, Z.M. Expression Profiling of certain MADS-Box Genes in Arabidopsis Thaliana plant treated by silver nanoparticles. Czech Journal of Genetics and Plant Breeding. 2017, 53, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djanaguiraman, M.; Nair, R.; Giraldo, J.P.; Prasad, P.V.V. Cerium oxide nanoparticles decrease drought induced oxidative damage in sorghum leading to higher photosynthesis and grain yield. ACS omega. 2018, 3, 14406–14416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Shabala, L.; Shabala, S.; Giraldo, J. P. Hydroxyl radical scavenging by cerium oxide nanoparticles improves Arabidopsis salinity tolerance by enhancing leaf mesophyll potassium retention. Environmental Science: Nano. 2018, 5, 1567–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.H.; Al-Whaibi, M.H.; Faisal, M.; Al Sahli, A.A. Nano-silicon dioxide mitigates the adverse effects of salt stress on Cucurbita pepo L. Environmental Toxicology Chemistry, 2014, 33, 2429–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brecht, M.O.; Datnoff, L.E.; Kucharek, T.A.; Nagata, R.T. Influence of silicon and chlorothalonil on the suppression of gray leaf spot and increase plant growth in St. Augustinegrass. Plant Disease. 2004, 88, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, J.; Mohsenzadeh, S. 'Effects of silicon oxide nanoparticles on growth and physiology of wheat seedlings'. Russian Journal of plant physiology. 2016, 63, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şener, S.; Sayğı, H.; Duran, C.N. Responses of in vitro strawberry plants to drought stress under the influence of nano-silicon dioxide. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelali, N.; Dell'Orto, M.; Rabhi, M.; Zocchi, G.; Abdelly, C.; Gharsalli, M. Physiological and biochemical responses for two cultivars of Pisum sativum ("Merveille de Kelvedon" and "Lincoln") to iron deficiency conditions. Scientia horticulturae. 2010, 124, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Shieh, J.P.; Tzeng, J.I.; Chia-Hui, H.; Cheng, Y.L.; Huang, K.L.; Wang, J.J. Noveldepots of ketorolac esters have long-acting antinociceptive and antiinflammatory effects. Anesth. Analg. 2005, 101, 785–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askary, M.; Talebi, S.; Amini, F.; Bangan, A. D. Effect of NaCl and iron oxide nanoparticles on Mentha Piperita essential oil composition. Environmental and Experimental Biology. 2016, 14, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafariyan, M.H.; Malakouti, M.J.; Dadpour, M.R.; Stroeve, P.; Mahmoudi, M. Effects of magnetite nanoparticles on soybean chlorophyll. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 10645–10652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armin, A.; Fotouhi, R.; Szyszkowski, W. On the FE modeling of soil-blade interaction in tillage operations. Finite Elements in Analysis and Design, 2014, 92, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beykaya, M.; Çağlar, A. Bitkisel özütler kullanılarak gümüş nanopartikül (AgNP) sentezlenmesi ve antimikrobiyal etkinlikleri üzerine bir araştırma. Afyon Kocatepe Üniversitesi Fen Ve Mühendislik Bilimleri Dergisi 2016, 16, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prathna, T.C.; Sharma, S.K.; Kennedy, M. Nanoparticles in household level water treatment: an overview. Separation and Purification Technology, 2018, 199, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, A. Brief overview of the application of silver nanoparticles to improve growth of crop plants. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2018, 12, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Jha, A.B.; Dubey, R.S.; Pessarakli, M. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J Bot. 2012, 12, 134–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaveh, R.; Li, Y.S.; Ranjbar, S.; Tehrani, R.; Brueck, C.L.; Van Aken, B. Changes in Arabidopsis thaliana gene expression in response to silver nanoparticles and silver ions. Environ Sci Technol. 2013, 47, 10637–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannini, N.; Girotra, M.; Naveiras, O.; Nikitin, G.; Campos, V.; Giger, S.; Roch, A.; Auwerx, J.; Lutolf, M.P. Specification of haematopoietic stem cell fate via modulation of mitochondrial activity. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 13125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, A.; Chen, Z. Impacts of silver nanoparticles on plants: A focus on the phytotoxicity and underlying mechanism. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatami, M.; Ghorbanpour, M. Effect of nanosilver on physiological performance of pelargonium plants exposed to dark storage. J. Hort. Res. 2013, 21, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighi, M.; Pessarakli, M. Influence of silicon and nano-silicon on salinity tolerance of cherrytomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum L.) at early growth stage. Scientia Horticulturae 2013, 161, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalteh, M.; Alipour, Z.T.; Ashraf, S.; Aliabadi, M.M.; Nosratabadi, A.F. Effect of silica nanoparticles on basil (Ocimum basilicum) under salinity stress. J Chem Health Risks. 2014, 4, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, M.; Raja, N.; Mashwani, Z.R.; Hussain, M.; Ejaz, M.; Yasmeen, F. Effect of silver nanoparticles on growth of wheat under heat stress. Iran J Sci Technol Trans Sci, 2017, 43, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, P.G.M.; Chung, I.M. Impact of copper oxide nanoparticles exposure on Arabidopsis thaliana growth, root system development, root lignificaion, and molecular level changes. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2019, 21, 12709–12722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuesombat, P.; Hannongbua, S.; Akasit, S.; Chadchawan, S. Effect of silver nanoparticles on rice (Oryza sativa L. cv. KDML 105) seed germination and seedling growth. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf, 2014, 104, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimkpa, C.O.; Latta, D.E.; McLean, J.E.; Britt, D.W.; Boyanov, M.I.; Anderson, A.J. Fate of CuO and ZnO nano- and microparticles in the plant. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 4734–4742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Ming, D.; Liu, D.; Wan, G.; Geng, X.; Gong, H.; Zhou, W. Silicon improves the tolerance to water-deficit stress induced by polyethylene glycol in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seedlings. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2010, 29, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şener, S.; Kurt, Z. The effects of Benzyl Amino Purine (BAP) and Indole Butyric Acid (IBA) on in vitro shoot proliferation and rooting of Boysenberry. COMU J. of Agr. F. 2022, 10, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A. Revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiological Plantarum, 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Colman, B.P.; McGill, B.M.; Wright, J.P.; Bernhardt, E.S. Effects of silver nanoparticle exposure on germination and early growth of eleven wetland plants. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, F.J.; de Andrés, E.F.; Tenorio, J.L.; Ayerbe, L. Growth of epicotyls, turgor maintenance and osmotic adjustment in pea plants (Pisum sativum L.) subjected to water stress. Field Crop. Res. 2004, 86, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, S. Relative contribution of meristem activities and specific leaf area to shoot relative growth rate in C3 grass species. Functional Ecology, 2005, 19, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, I. Activity of ascorbate-dependent H2O2-scavenging enzymes and leaf chlorosis are enhanced in magnesium-and potassium-deficient leaves, but not in phosphorus-deficient leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 1994, 45, 1259–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, W.F.; Fridovich, I. Assaying for superoxide dismutase activity: Some large consequences of minor changes in conditions. Anal. Biochem. 1987, 161, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turhan, E.; And Eriş, A. Growth and stomatal behaviour of two strawberry cultivars under long-term salinity stress. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, 2007, 31, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Olur, Ü.; Uçar, C.; Akköprü, A. Tuz stresi altında gelişen bitkilerden izole edilen endofit bakterilerin bazı bitki gelişimini teşvik etme mekanizmalarının ve hıyar fide gelişimine etkilerinin belirlenmesi. Mustafa Kemal Üniversitesi Tarım Bilimleri Dergisi 2021, 26, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuzlar, E.E.; Karadal, S.; Adak, N. in vitro koşullarda farklı glisin konsantrasyonlarının çileklerde tuzluluk stresi üzerine etkileri. Anadolu Tarım Bilimleri Dergisi 2021, 36, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmazloum, I.; Eisa, E.A.; Honfi, P.; Tilly-Mándy, A. Exogenous melatonin application ınduced morpho-physiological and biochemical regulations conferring salt tolerance in Ranunculus asiaticus L. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hort Americas. Fresh Weight vs. Dry Weight. 2022. Available online: https://hortamericas.com/blog/fresh-weight-vs-dry-weight/ (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Azimi, R.; Borzelabad, M.J.; Feizi, H.; Azimi, A. Interaction of SiO2 nanoparticles with seed prechilling on germination and early seedling growth of tall wheatgrass (Agropyron elongatum L.). Polish J Chem Technol, 2014, 16, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.; Rahmatullah, A.; Aziz, T.; Ashraf, M. Wheat genotypes differed signifi cantly in their response to silicon nutrition under salinity stress. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 2010, 33, 1658–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, A. Bazı Yerel Taze Fasulye Genotiplerinin Tuza (NaCl) Tolerans Düzeylerinin Belirlenmesi. Selçuk Üniversitesi, Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Bahçe Bitkileri Anabilim Dalı, 2012, 54. Available online: https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/tezSorguSonucYeni.jsp (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Omar, R.A.; Afreen, S.; Talreja, N.; Chauhan, D.; Ashfaq, M. Impact of nanomaterials in plant systems. In Plant Nanobionics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Can, B.; Gürel, A. Nanopartiküllerin bitki sistemlerinde ve bitki doku kültürlerinde uygulamalarına yönelik genel bir bakış. International Journal of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, 2023, 6, 335–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Saeed, K.; Khan, I. Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 908–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, J.; Mohsenzadeh, S. Effects of silicon oxide nanoparticles on growth and physiology of wheat seedlings. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 63, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şener, S.; Duran, C.N.; Kurt, Z. The effect of silica gel application on plant growth, yield and fruit quality in greenhouse strawberry production. ANADOLU Ege Tarımsal Araştırma Enstitüsü Dergisi 2021, 31, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, N.; Ashraf, M. Role of silicon in mitigating the adverse effects ofsalt stress on growth and photosynthetic attributes of two maize (Zea mays L.) cultivars grown hydroponically. Pak. J. Bot. 2010, 42, 1675–1684. [Google Scholar]

- El-Kady, M.E.; El-Boray, M.S.; Shalan, A.M.; Mohamed, L.M. Effect of silicon dioxide nanoparticles on growth improvement of banana shoots in vitro within rooting stage. Journal of Plant Production 2017, 8, 913–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, R. Importance of individual root traits to understand crop root system in agronomic and environmental contexts. Breed Sci. 2021, 71, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, H.-S.; Jeong, H.-W.; Jo, H.-G.; Kang, J.-H.; Hwang, S.-J. Rooting and growth characteristics of 'Maehyang' strawberry cutting transplants affected by different growing media including decomposed granite. Rhizosphere 2022, 22, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.S.; Kumar, D.S. Effect of nanoparticles on plants with regard to physiological attributes. In Plant Nanotechnology; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 119–153. [Google Scholar]

- Badawy, S.A.; Zayed, B.A.; Bassiouni, S.M.A.; Mahdi, A.H.A.; Majrashi, A.; Ali, E.F.; Seleiman, M.F. Influence of Nano Silicon and Nano Selenium on Root Characters, Growth, Ion Selectivity, Yield, and Yield Components of Rice (Oryza sativa L.) under Salinity Conditions. Plants 2021, 10, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salih, A.M.; Qahtan, A.A.; Al-Qurainy, F.; Al-Munqedhi, B.M. Impact of biogenic ag-containing nanoparticles on germination rate, growth, physiological, biochemical parameters, and antioxidants system of tomato (Solanum tuberosum L.) in vitro. Processes 2022, 10, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, M. Çilekte Kadmiyum Toksitesi Altındaki Bitkiler Üzerine Hümik Asit ve Silikonun Etkilerinin İncelenmesi. Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Harran Üniversitesi, Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Bahçe Bitkileri Anabilim Dalı, 2018, 46. Available online: https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/tezSorguSonucYeni.jsp (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Wang, C.; He, J.; Zhao, T.-H.; Cao, Y.; Wang, G.; Sun, B.; Yan, X.; Guo, W.; Li, M.-H. The smaller the leaf ıs, the faster the leaf water loses in a temperate forest. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bora, M. Değişik Vejetasyon Dönemlerine Kadar Uygulanan Farklı Tuz Konsantrasyonlarının Biberde Meydana Getirdiği Fizyolojik, Morfolojik ve Kimyasal Değişikliklerin Belirlenmesi. Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Namık Kemal Üniversitesi, Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Tekirdağ. 2014. Available online: https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/tezSorguSonucYeni.jsp (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Bernal, O.B.; Spinoso-Castillo, J.L.; Mancilla-Álvarez, E.; Trujillo, R.A.M.M.; Bello-Bello, J.J. In vitro conservation and regeneration of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.): role of paclobutrazol and silver nanoparticles. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avestan, S.; Ghasemnezhad, M.; Esfahani, M.; Byrt, C.S. Application of nano-silicon dioxide improves salt stress tolerance in strawberry plants. Agronomy 2019, 9, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoundnejad, Y.; Baran, Ş.; Karakaş, Ö.; Mısırdalı, H. Farklı Dozlardaki Gümüş Nanopartiküllerinin Taze Soğan (Allium Cepa) Üzerine Etkisi. Şırnak Üniversitesi. Şırnak Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Dergisi. 2019. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/sufbd/issue/46848/551480 (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Abou-Shlell, M.K.; El-Emary, F.A.; KHalifa, A.A. Effect of nanoparticle on growth, biochemical and anatomical characteristics of moringa plant (Moringa oleifera L.) under salinity stress condition. Archives of Agricultural Sciences Journal 2020, 3, 186–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, Z.; Alharbi, A. Effect of silver nanoparticles on seed germination of crop plants. J. Adv. Agric. 2015, 4, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, N.; Ashraf, M. Role of silicon in mitigating the adverse effects ofsalt stress on growth and photosynthetic attributes of two maize (Zea mays L.) cultivars grown hydroponically. Pak. J. Bot. 2010, 42, 1675–1684. [Google Scholar]

- Bayramzadeh, V.; Ghadiri, M.; Davoodi, M.H. Effects of silver nanoparticle exposure on germination and early growth of Pinus sylvestris and Alnus subcordata. Sains Malays. 2019, 48, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-aghabary, K.; Zhu, Z.; Shi, Q. Influence of silicon supply on chlorophyll content, chlorophyll fluorescence, and antioxidative enzyme activities in tomato plants under salt stress. Journal of Plant Nutrition 2005, 27, 2101–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuşvuran, Ş.; Yaşar, F.; Abak, K.; Ellialtıoğlu, Ş. tuz stresi altında yetiştirilen tuza tolerant ve duyarlı Cucumis sp.’nin bazı genotiplerinde lipid peroksidasyonu, klorofil ve iyon miktarlarında meydana gelen değişimler. YY Üniversitesi Tarım Bilimleri Dergisi (J. Agric. Sci.) 2008, 18, 13–20. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/yyutbd/issue/21987/236073 (accessed on 09 March 2023).

- Gökçe, Z.Z. Gümüş Nanopartiküllerinin Domates (Lycopersicon Esculentum Mill.) Tohumları Üzerindeki Fizyolojik ve Biyokimyasal Etkilerinin Araştırılması. Yüksek Lisans Tezi, İstanbul Üniversitesi, Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Biyoloji Anabilim Dalı. 2019. Available online: https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/tezSorguSonucYeni.jsp (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Soltys-Kalina, D.; Plich, J.; Strzelczyk-Żyta, D.; Śliwka, J.; Marczewski, W. The effect of drought stress on the leaf relative water content and tuber yield of a half-sib family of 'Katahdin'-derived potato cultivars. Breeding science 2016, 66, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Shen, W.; Vanessa, P.; Cheng, F. Synergistic effect of Si and K in improving the growth, ion distribution and partitioning of Lolium perenne L. under saline-alkali stress. Journal of Integrative Agriculture. 2021, 20, 1660–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, S.M.; Moharrami, F.; Sarikhani, S.; Padervand, M. Selenium and silica nanostructure-based recovery of strawberry plants subjected to drought stress. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 17672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syu, Y.Y.; Hung, J.H.; Chen, J.C.; Chuang, H.W. Impact of size and shape of silver nanoparticles on Arabidopsis plant growth and gene expression. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 83, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiruvengadam, M.; Gurunathan, S.; Chung, I.-M. Physiological, metabolic, and transcriptional effects of biologically-synthesized silver nanoparticles in turnip (Brassica rapa ssp. rapa L.). Protoplasma 2015, 252, 1031–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landa, P.; Prerostova, S.; Petrova, S.; Knirsch, V.; Vankova, R.; Vanek, T. The transcriptomic response of Arabidopsis thaliana to zinc oxide: A comparison of the impact of nanoparticle, bulk, and ionic zinc. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 14537–14545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, S.M.; Turoop, L.; Runo, S.; Nyanjom, S. The effect of foliar application of zinc oxide nanoparticles and Moringa oleifera leaf extract on growth, biochemical parameters and in promoting salt stress tolerance in faba bean. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2022, 21, 252–266. [Google Scholar]

- Semida, W.M.; Abdelkhalik, A.; Mohamed, G.F.; Abd El-Mageed, T.A.; Abd El-Mageed, S.A.; Rady, M.M.; Ali, E.F. Foliar application of zinc oxide nanoparticles promotes drought stress tolerance in eggplant (Solanum melongena L.). Plants 2021, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.-S.; Li, K.; Wang, Q.-M.; Song, X.-Y.; Su, H.-N.; Xie, B.-B.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Huang, F.; Bai-Cheng, Z.; Zhou, B.-C.; et al. Nitrogen starvation impacts the photosynthetic performance of porphyridium cruentum as revealed by chlorophyll a fluorescence. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pommerening, A.; Muszta, A. Methods of modelling relative growth rate. For. Ecosyst. 2015, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.H.; Al-Whaibi, M.H.; Firoz, M.; Al-Khaishany, M.Y. Role of Nanoparticles in Plants. In Nanotechnology and Plant Sciences; Siddiqui, M., Al-Whaibi, M., Mohammad, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elatafi, E.; Fang, J. Effect of Silver Nitrate (AgNO3) and Nano-Silver (Ag-NPs) on physiological characteristics of grapes and quality during storage period. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Peng, B.; Hernandez-Viezcas, J.A.; Rico, C.; Sun, Y.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Tang, X.; Niu, G.; Jin, L.; Varela-Ramirez, A.; et al. Stress response and tolerance of Zea mays to CeO2 nanoparticles: Cross talk among H2O2, Heat Shock Protein and Lipid Peroxidation. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 9615–9622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günalp, B. Patlıcan (Solanum melongena L.) Embriyo Kültüründe, Jasmonik Asit ve Tuz Stresi Etkileşiminin İncelenmesi. Ankara Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü (Basılmamış), Yüksek Lisans Tezi. Ankara, 2011, 77. Available online: https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/tezSorguSonucYeni.jsp (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Zulfiqar, F.; Ashraf, M. Nanoparticles potentially mediate salt stress tolerance in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 160, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abogadallah, G.M. Antioxidative defense under salt stress. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010, 5, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Media | Applications |

|---|---|

| MS1 | 0 mM NaCl |

| MS2 | 15 mM NaCI |

| MS3 | 35 mM NaCI |

| MS4 | 7.5 mg L-1 SiNP |

| MS5 | 15 mM NaCI + 7.5 mg L-1 SiNP |

| MS6 | 35 mM NaCI +7.5 mg L-1 SiNP |

| MS7 | 15 mg L-1 SiNP |

| MS8 | 15 mM NaCI + 15 mg L-1 SiO2 NP |

| MS9 | 35 mM NaCI + 15 mg L-1 SiO2 NP |

| MS10 | 0.025 mM FeNP |

| MS11 | 15 mM NaCI + 0.025 mM FeNP |

| MS12 | 35 mM NaCI + 0.025 mM FeNP |

| MS13 | 0.05 mM FeNP |

| MS14 | 15 mM NaCI + 0.05 mM FeNP |

| MS15 | 35 mM NaCI + 0.05 mM FeNP |

| MS16 | 0.2 mg L-1 Ag |

| MS17 | 15 mM NaCI + 0.2 mg L-1 Ag |

| MS18 | 35 mM NaCI + 0.2 mg L-1 Ag |

| MS19 | 0.4 mg L-1 Ag |

| MS20 | 15 mM NaCI + 0.4 mg L-1 Ag |

| MS21 | 35 mM NaCI + 0.4 mg L-1 Ag |

| NP Applications | NaCl Concentrations | SFW (g) | SDW (g) | SL (mm) | SD (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mg L-1 NP | 0 mM | 0.423 cd | 0.137 c | 33.62 b | 0.95 b |

| 15 mM | 0.617 abcd | 0.186 ab | 40.42 ab | 1.06 ab | |

| 35 mM | 0.526 bcd | 0.258 ab | 29.56 b | 1.12 ab | |

| 7.5 mg L-1 SiNP | 0 mM | 0.614 abcd | 0.137 b | 46.14 ab | 1.21 ab |

| 15 mM | 0.487 bcd | 0.180 ab | 51.30 ab | 0.83 b | |

| 35 mM | 0.610 abcd | 0.230 ab | 51.71 ab | 2.20 ab | |

| 15 mg L-1 SiNP | 0 mM | 0.651 abc | 0.356 ab | 52.19 ab | 2.46 a |

| 15 mM | 0.537 bcd | 0.363 ab | 47.39 ab | 1.65 ab | |

| 35 mM | 0.376 d | 0.250 ab | 48.88 ab | 1.60 ab | |

| 0.025 mM FeNP | 0 mM | 0.516 bcd | 0.132 b | 35.19 b | 1.39 ab |

| 15 mM | 0.841 a | 0.446 a | 35.01 b | 1.29 ab | |

| 35 mM | 0.522 bcd | 0.355 ab | 39.09 ab | 1.19 ab | |

| 0.05 mM FeNP | 0 mM | 0.688 ab | 0.453 a | 49.46 ab | 1.18 ab |

| 15 mM | 0.565 bcd | 0.293 ab | 29.78 b | 1.09 ab | |

| 35 mM | 0.477 bcd | 0.328 ab | 27.08 b | 1.29 ab | |

| 0.2 mg L-1AgNP | 0 mM | 0.537 bcd | 0.168 b | 29.41 b | 1.60 ab |

| 15 mM | 0.519 bcd | 0.232 ab | 61.10 a | 1.14 ab | |

| 35 mM | 0.572 bcd | 0.136 b | 42.47 ab | 1.42 ab | |

| 0.4 mg L-1AgNP | 0 mM | 0.478 bcd | 0.287 ab | 44.83 ab | 1.07 ab |

| 15 mM | 0.528 bcd | 0.176 ab | 46.14 ab | 1.24 ab | |

| 35 mM | 0.520 bcd | 0.120 b | 36.88 ab | 1.73 ab |

| NP Applications | NaCl Concentrations | RFW (g) | RDW (g) | RL (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mg L-1 NP | 0 mM | 0.495 abcde | 0.066 b | 15.64 ef |

| 15 mM | 0.483 abcde | 0.031 b | 15.76 ef | |

| 35 mM | 0.103 f | 0.018 b | 11.09 ef | |

| 7.5 mg L-1 SiNP | 0 mM | 0.513 abcd | 0.117 b | 47.16 ab |

| 15 mM | 0.429 abcde | 0.023 b | 11.87 ef | |

| 35 mM | 0.371 cde | 0.010 b | 8.50 f | |

| 15 mg L-1 SiNP | 0 mM | 0.475 abcde | 0.042 b | 29.28 bcde |

| 15 mM | 0.508 abcd | 0.120 b | 19.47 def | |

| 35 mM | 0.402 bcde | 0.107 b | 30.10 bcde | |

| 0.025 mM FeNP | 0 mM | 0.355 de | 0.099 b | 36.89 abcd |

| 15 mM | 0.613 a | 0.571 a | 54.07 a | |

| 35 mM | 0.552 abc | 0.012 b | 14.34 ef | |

| 0.05 mM FeNP | 0 mM | 0.596 bc | 0.076 b | 15.56 ef |

| 15 mM | 0.587 ab | 0.246 b | 36.11 abcd | |

| 35 mM | 0.489 abcde | 0.141 b | 41.95 abc | |

| 0.2 mg L-1AgNP | 0 mM | 0.529 abcd | 0.043 b | 21.80 def |

| 15 mM | 0.519 abcd | 0.057 b | 19.37 def | |

| 35 mM | 0.347 de | 0.070 b | 20.72 def | |

| 0.4 mg L-1AgNP | 0 mM | 0.483 abcde | 0.027 b | 24.28 cdef |

| 15 mM | 0.452 abcde | 0.029 b | 30.53 bcde | |

| 35 mM | 0.313 e | 0.021 b | 28.20 bcde |

| NP Applications | NaCl Concentrations | NL (per plant) | LL (mm) | LW (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mg L-1 NP | 0 mM | 8.75 cdef | 14.85 abc | 12.85 ab |

| 15 mM | 13.25 bcde | 7.19 bcd | 6.43 bc | |

| 35 mM | 4.50 f | 5.34 e | 5.21 c | |

| 7.5 mg L-1 SiNP | 0 mM | 12.50 bcdef | 11.44 abcd | 11.54 abc |

| 15 mM | 17.50 ab | 13.26 abcd | 11.75 abc | |

| 35 mM | 12.75 bcdef | 10.66 abcd | 10.60 abc | |

| 15 mg L-1 SiNP | 0 mM | 10.75 bcdef | 14.56 abc | 13.26 ab |

| 15 mM | 12.75 bcdef | 13.66 abc | 10.75 abc | |

| 35 mM | 17.25 abc | 12.75 abcd | 11.62 abc | |

| 0.025 mM FeNP | 0 mM | 23.25 a | 14.24 abc | 13.34 ab |

| 15 mM | 17.50 ab | 13.82 abc | 11.93 abc | |

| 35 mM | 14.50 bcd | 10.43 bcd | 11.59 abc | |

| 0.05 mM FeNP | 0 mM | 10.75 bcdef | 6.61 cd | 7.58 abc |

| 15 mM | 11.00 bcdef | 12.46 abcd | 11.84 abc | |

| 35 mM | 13.75 bcde | 14.40 abc | 11.89 abc | |

| 0.2 mg L-1AgNP | 0 mM | 8.25 def | 12.32 abcd | 10.65 abc |

| 15 mM | 9.00 bcdef | 18.70 a | 14.46 a | |

| 35 mM | 9.00 bcdef | 9.97 bcd | 9.70 abc | |

| 0.4 mg L-1AgNP | 0 mM | 11.50 bcdef | 10.14 bcd | 9.08 abc |

| 15 mM | 5.25 ef | 15.37 ab | 11.55 abc | |

| 35 mM | 13.50 bcde | 14.45 abc | 11.77 abc |

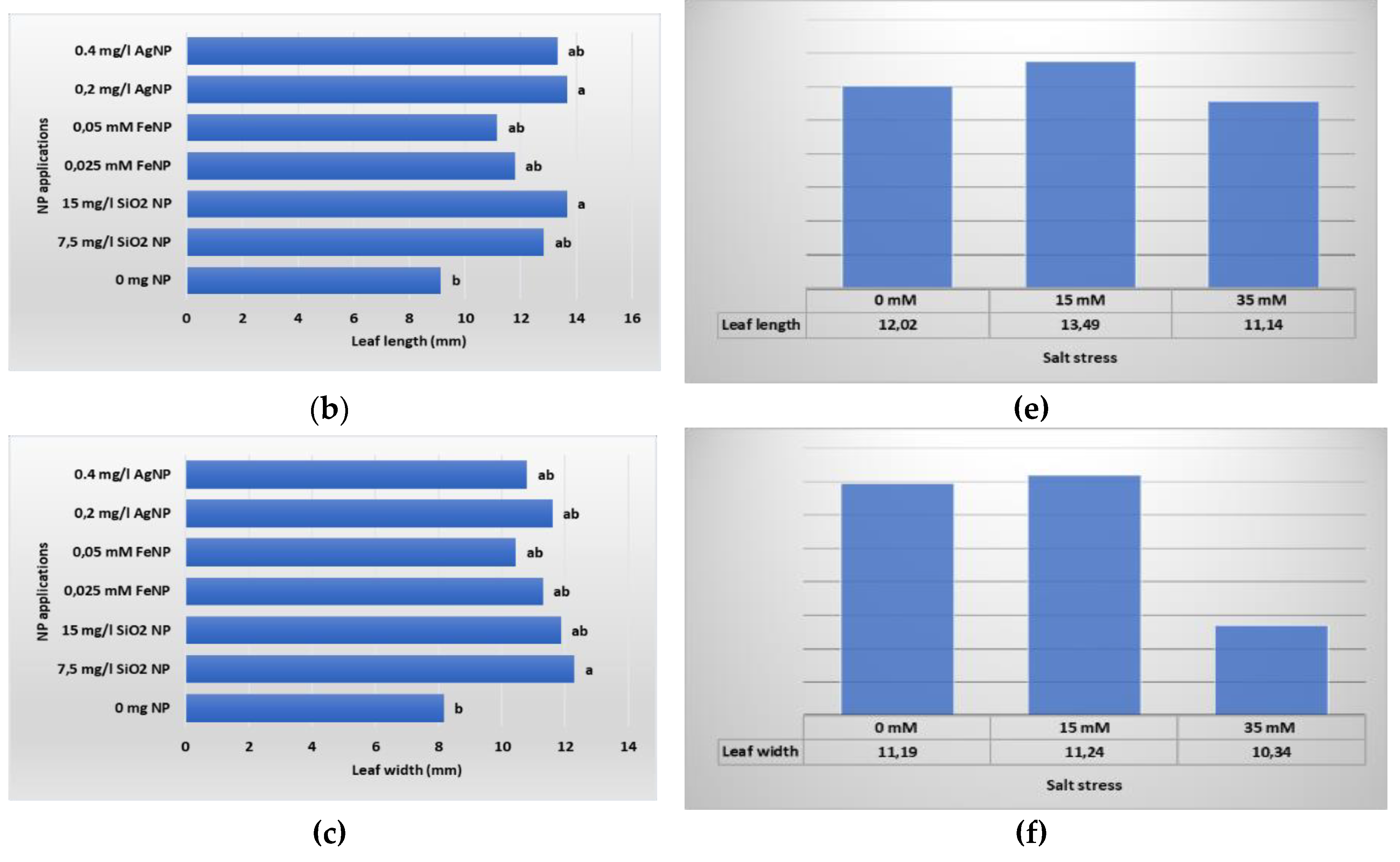

| NP Applications | NaCl Concentrations | SPAD value | LRWC (%) | RGR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mg L-1 NP | 0 mM | 65.35 cd | 46.05 g | 0.011 ef |

| 15 mM | 87.48 ab | 32.06 ı | 0.008 fgh | |

| 35 mM | 55.04 d | 35.23 hı | 0.006 h | |

| 7.5 mg L-1 SiNP | 0 mM | 69.16 cd | 58.33 ef | 0.020 d |

| 15 mM | 63.98 cd | 92.87 a | 0.008 fgh | |

| 35 mM | 58.62 d | 63.92 d | 0.008 fgh | |

| 15 mg L-1 SiNP | 0 mM | 58.52 d | 54.35 ef | 0.024 c |

| 15 mM | 58.30 d | 52.71 f | 0.011 ef | |

| 35 mM | 72.36 bcd | 45.67 g | 0.007 gh | |

| 0.025 mM FeNP | 0 mM | 78.70 abc | 62.83 d | 0.013 e |

| 15 mM | 64.95 cd | 78.89 c | 0.010 efg | |

| 35 mM | 63.12 cd | 53.33 e | 0.006 h | |

| 0.05 mM FeNP | 0 mM | 65.81 cd | 52.74 f | 0.007 gh |

| 15 mM | 57.58 d | 32.25 ı | 0.011 ef | |

| 35 mM | 56.73 d | 44.95 g | 0.008 fgh | |

| 0.2 mg L-1AgNP | 0 mM | 69.85 cd | 52.59 f | 0.056 a |

| 15 mM | 57.03 d | 77.42 c | 0.034 b | |

| 35 mM | 77.25 abc | 36.75 h | 0.013 e | |

| 0.4 mg L-1AgNP | 0 mM | 69.20 cd | 84.71 b | 0.025 c |

| 15 mM | 89.63 a | 65.17 d | 0.010 efg | |

| 35 mM | 65.00 cd | 64.60 d | 0.013 e |

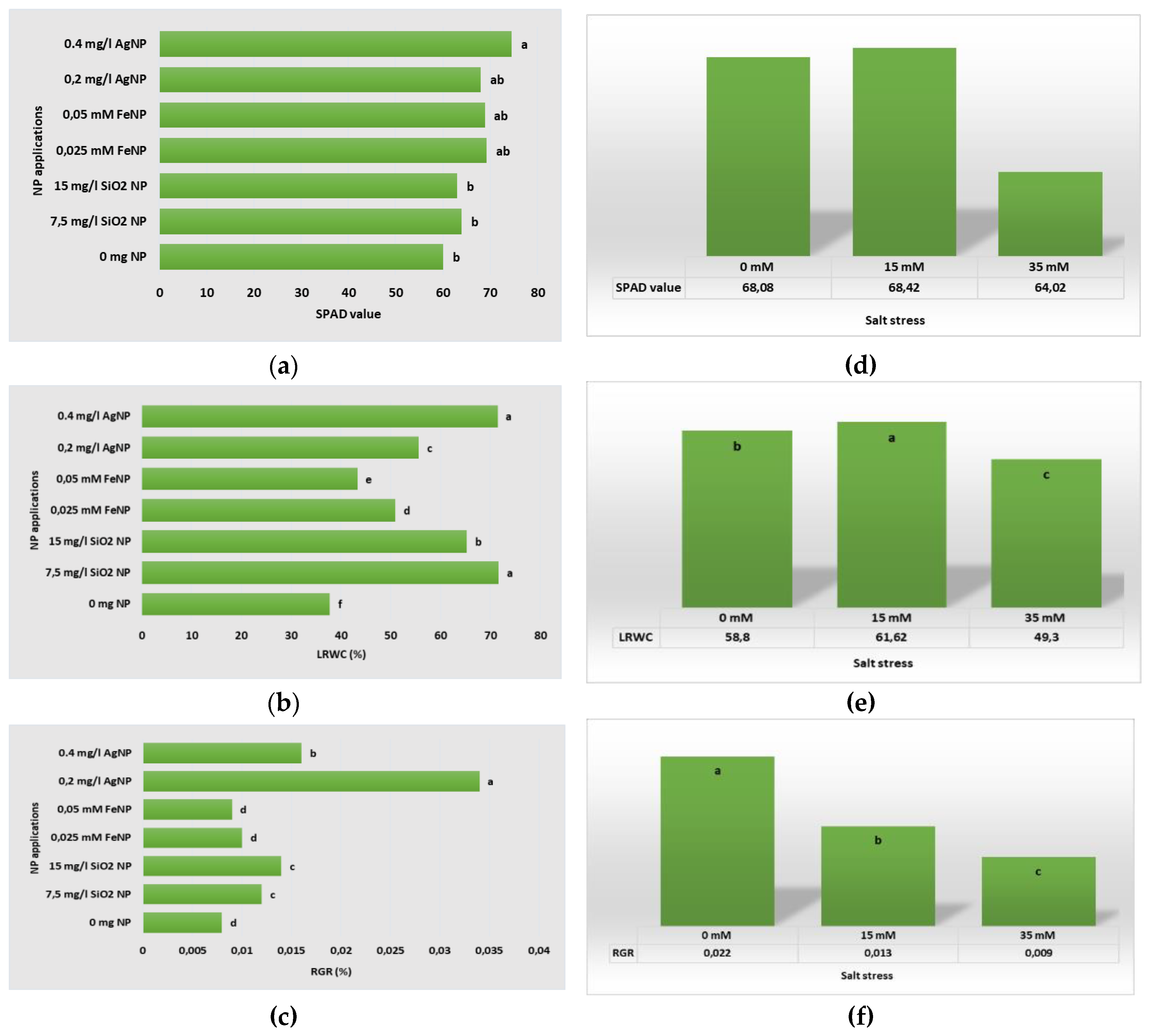

| NP Applications | NaCl Concentrations | CAT activity (U/g TA) | SOD activity (U/g TA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mg L-1 NP | 0 mM | 16.81 h | 59.20 h |

| 15 mM | 17.42 bcd | 96.34 fgh | |

| 35 mM | 17.67 ab | 101.54 fgh | |

| 7.5 mg L-1 SiNP | 0 mM | 17.27 cdef | 89.19 fgh |

| 15 mM | 16.98 fgh | 146.07 defg | |

| 35 mM | 17.43 bcd | 200.22 bcd | |

| 15 mg L-1 SiNP | 0 mM | 16.86 gh | 53.93 h |

| 15 mM | 17.57 abc | 263.49 ab | |

| 35 mM | 17.45 abcd | 61.85 h | |

| 0.025 mM FeNP | 0 mM | 17.44 bcd | 94.61 fgh |

| 15 mM | 17.37 bcde | 101.71 fgh | |

| 35 mM | 17.45 abcd | 68.23 gh | |

| 0.05 mM FeNP | 0 mM | 16.99 fgh | 112.98 efgh |

| 15 mM | 17.42 bcd | 162.75 cdef | |

| 35 mM | 17.82 a | 311.55 a | |

| 0.2 mg L-1AgNP | 0 mM | 17.38 bcde | 88.04 fgh |

| 15 mM | 17.23 cdefg | 239.31 abc | |

| 35 mM | 17.50 abcd | 184.79 bcde | |

| 0.4 mg L-1AgNP | 0 mM | 17.03 efgh | 198.63 bcd |

| 15 mM | 17.13 defgh | 155.70 def | |

| 35 mM | 17.19 cdefg | 212.81 bcd |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).