1. Introduction

Heart transplantation is the treatment of choice for patients experiencing advanced heart failure that does not respond to medical, pharmacological, or surgical interventions [

1]. After transplantation, patients must begin treatment with immunosuppressive drugs, which they will continue throughout their lives to prevent rejection of the transplanted organ. However, these drugs also have side effects, with atherosclerosis being particularly notable.

Currently, supervised exercise training in cardiac rehabilitation programs is safe and is recommended by professional societies both before (pre-habilitation) and after heart transplantation [

2]. Moreover, physical exercise is recognized as an important non-pharmacological therapy for heart transplant recipients (HTR) to enhance mobility, muscle strength, quality of life, and chronotropic response [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Nonetheless, the health status of HTR in relation to their level of physical activity (-PA-, low, moderate or high) remains unknown. This information would be relevant and valuable for researchers and professionals. Among other key utilities, it would provide a deeper understanding of the effect of the exercise on HTR, guide the design of interventional studies aiming to assess the effect of different training protocols and optimize the supervised exercise that they must perform (

e.g., addressing the exercise to higher or lower intensity and volume, in more or fewer sessions per week).

Thus, considering the importance of physical exercise as a non-pharmacological therapy for HTR and the lack of studies examining the health status of these patients in relation to their PA level, the objectives of this study were to assess the health status of a group of HTR and their PA level and to compare their health status with that of a group of healthy sedentary individuals (S). It was hypothesized that HTR with higher levels of PA would exhibit better health statuses than those with moderate or low PA levels, and similar health statuses to the sedentary group.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Design

The present cross-sectional observational study (clinicaltrials.gov ID: NCT05282342, date of registration 29/12/2021;

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05282342) was designed following the recommendations of the declaration of standards for cross-sectional observational studies called Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE). The Research Ethics Committee of the University of León, ETICA-ULE-038-2021, approved and authorized the implementation of the study, which was conducted in accordance with the updated version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Participants

The study´s sample size was determined according to Cohen's power analysis for analysis of variance (ANOVA) designs [

8] using R software (

www.r-project.org, version 3.3.1., 2016.06.21). Four groups of people, an effect size (Cohen's f [

8]) of 0.40, a maximum significance level of 0.05 and a minimum power of 0.80 were established. The resulting sample size was 18 participants in each group.

Thus, fifty-four HTR and eighteen S participated in the project. Informed written consent was obtained from all the participants. The study eligibility criteria were as follows: men and women adult people (≥18 years) HTR who had undergone heart transplantation at least twelve months before the data collection of the study, HTR classified as having low, moderate, and high levels of PA practice, according to the results of The International Physical Activity Questionnaire - Long Form (IPAQ-L) [

9] and healthy people classified as sedentary based on the results of the IPAQ-L. People who did not meet the eligibility criteria were excluded from the study. This included individuals with physical disabilities and/or other limiting pathologies that affected their level of PA, as well as those who had undergone cardiac rehabilitation programs within the twelve months prior to the study.

Participants were assigned to four groups: patients with a low level of PA (HTRL,

n=18), patients with a moderate level of PA (HTRM,

n=18), patients with a high level of PA (HTRH,

n=18), and sedentary individuals (S,

n=18). The HTR and S were assigned to each group based on the results obtained from the Spanish version of the IPAQ-L [

10], which was used as an instrument to determine their level of PA.

2.3. Protocol

All participants underwent an anthropometric assessment. Subsequently, to gain a broad insight into the health status of the patients, they underwent a basic blood analysis and several tests to assess their cardiovascular, neuromuscular, and functional mobility conditions. All tests were brief, simple and easy to carry out (they do not require complicated protocols or expensive devices) but very useful as clinical outcomes. Finally, participants were also required to evaluate their quality of life. The tests were conducted by the same group of researchers over two to three data collection sessions.

2.4. Outcomes

The primary outcomes of the current study were:

Cardiovascular condition assessment. It was determined by the measurements of the systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP), the basal heart rate (HR) and the 2 Min Step Test (2MST) [

11]. The SBP and DBP were measured after 5 min in the seated position using an automatic blood pressure monitor (Omron HEM-7130, Kyoto, Japan) and the basal HR after 5 min in the supine position [

12]. The HR was recorded using a HR monitor (Polar S810, OY, Oulu, Finland) with a chest strap.

Neuromuscular condition assessment. It was determined by the measurements of the dominant and non-dominant hand grip strength, the Arm Curl Test (ACT) [

11] and the 30-Second Chair Stand Test (30SCST) [

13]. The grip strength was measured in the dominant and non-dominant hands according to a standard protocol [

14]. Measurements were taken with a digital hand dynamometer (JAMAR smart -Jamar, Lafayette, United States-).

The secondary outcomes of the current study were:

Basic blood analysis. It included the levels of glucose, creatine, uric acid, total cholesterol, high-density lipoproteins (HDL), low-density lipoproteins (LDL), triglycerides, total proteins, albumin and N-terminal pro-B type Natriuretic peptide pro-hormonal (NT Pro-BNP) (only for HTR since this is a heart damage marker).

Functional mobility condition assessment: It was evaluated with the Sit and Reach Test (SRT) [

15], the Back Scratch Test (BST) [

11], the Functional Balance Test [

16], the Timed up and Go Test (TUG) [

17] and the 10 Meters Walk Test (10MWT) [

18].

Complementary assessment: The patient´s quality of life was assessed with the Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36) [

19] in its Spanish version [

20].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using R software (

www.rproject.org, version 3.3.1, 2016.06.21) and were presented as means and standard deviations unless otherwise noted.

Differences in the characteristics among S, HTRH, HTRM and HTRL were assessed through the Fisher’s Exact test and the 1-way ANOVA test or the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test (if the assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity were not satisfied [Shapiro-Wilk and Bartlett tests, respectively]), for sex and rest of the parameters, respectively (p>0.05).

Given the dependent variables of the study, whether the assumptions were satisfied, the 1-way ANOVA was performed to determine whether there were significant differences among them (p<0.05). On the contrary, if the assumptions were not met, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was performed (p<0.05). As a result, the Tukey HSD post-hoc test or the Dunn´s test, were employed to determine specific differences between the variables, for the 1-way ANOVA and the Kruskal-Wallis test, respectively.

Effect size was also calculated to establish the magnitude of change when significant differences were detected. Cohen’s f (f=PostM

EX - PostM

C/PostSD

C; small=f>0.1, medium=f>0.25, and large=f>0.40) [

8] was used when data normality and homoscedasticity were verified. Rosenthal’s r (r=Z/√N; the “Z” value was obtained performing the Exact Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test; small=r>0.20, moderate=r>0.50, and great=r>0.80) [

21] was used when they were not.

3. Results

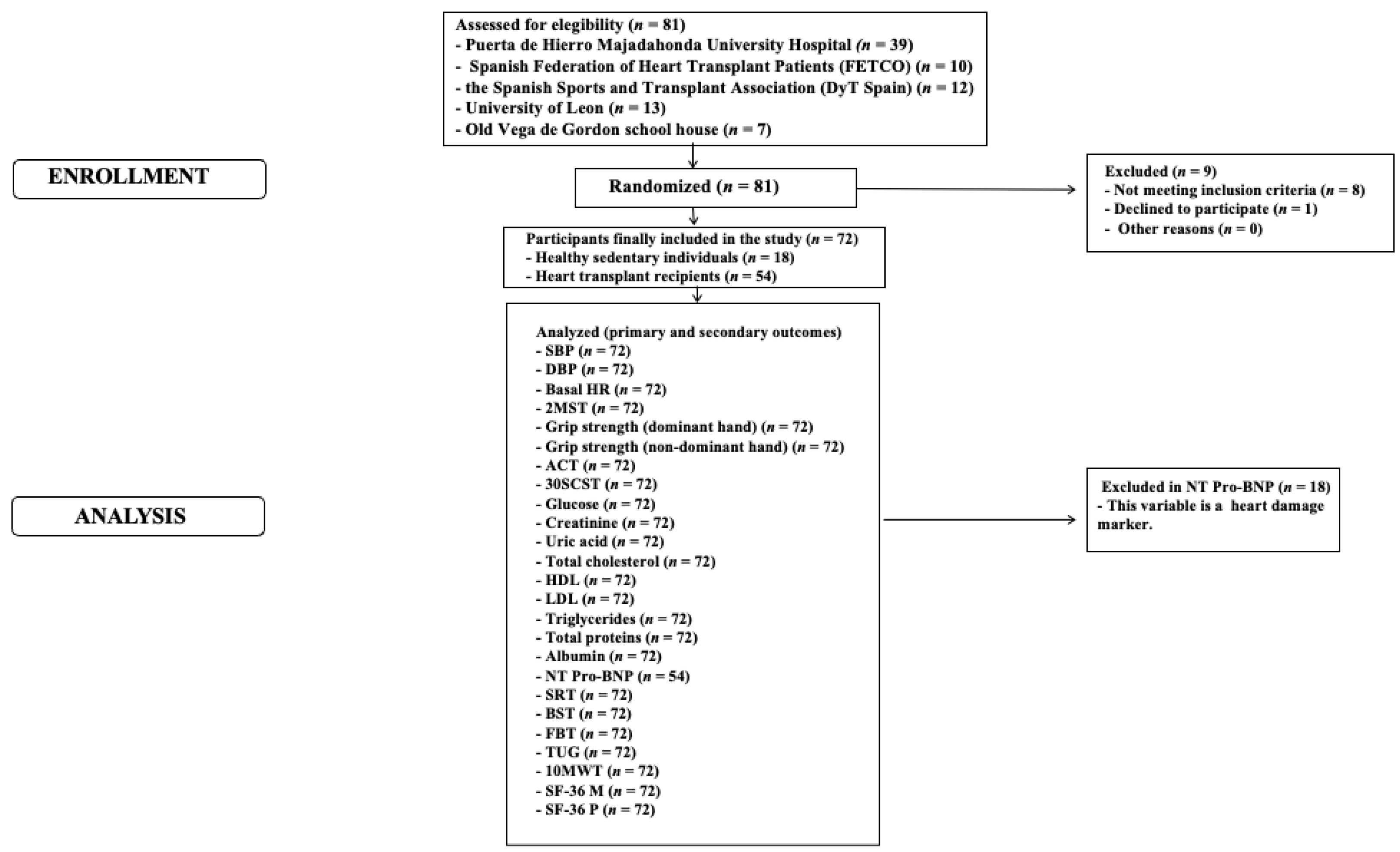

The STROBE diagram depicting the study's phases is shown in

Figure 1. Significant between-group differences were found in the number of men and women in each group and in age (

Table 1). No adverse events were reported during the data acquisition process.

Regarding the primary outcomes of the study, concerning the BP and the basal HR, no differences were detected among groups (

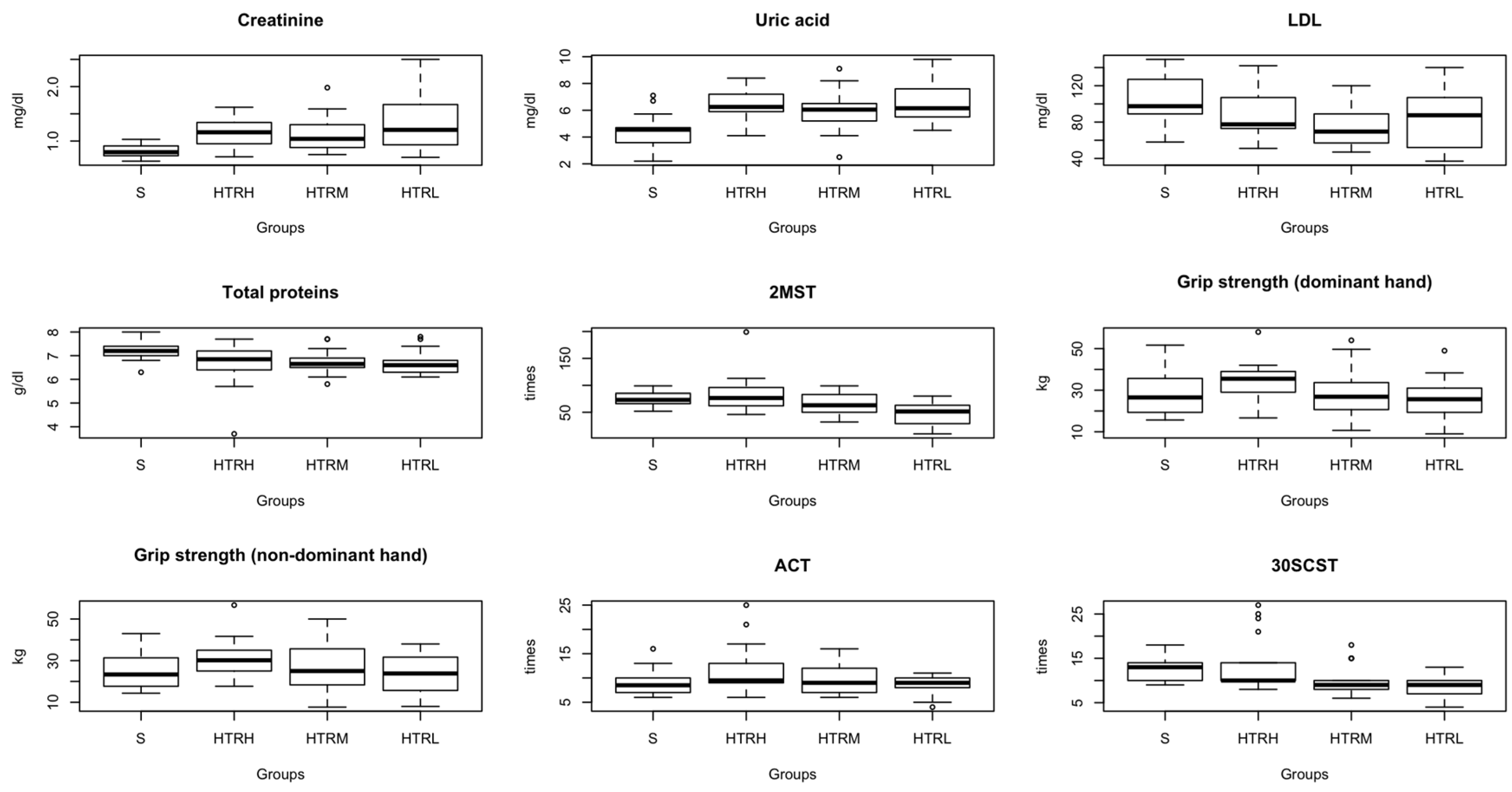

Table 2). The 2MST revealed differences between S and HTRM (

p=0.036, small effect), S and HTRL (

p=0.000, moderate effect), HTRH and HTRM (

p=0.029, small effect), HTRH and HTRL (

p=0.000, moderate effect) and HTRM and HTRL (

p=0.008, small effect) (

Table 2,

Figure 2).

Respecting the grip strength, considering the dominant hand, significant differences were detected between S and HTRH (

p=0.003, small effect), HTRH and HTRM (

p=0.029, small effect) and HTRH and HTRL (

p=0.006, small effect). Regarding the non-dominant hand differences were expressed between S and HTRH showed significant differences (

p=0.004, small effect) and HTRH and HTRL (

p=0.021, small effect) (

Table 2,

Figure 2).

About the ACT

, significant differences were detected between HTRH and HTRL (

p=0.034, small effect) (

Table 2,

Figure 2).

Regarding the 30SCST, differences were observed between S and HTRM (

p=0.001, small effect) and S and HTRL (

p=0.000, moderate effect). (

Table 2,

Figure 2).

Concerning the secondary outcomes of the study, concerning the basic blood analysis, creatinine showed significant differences between S and all HTR groups (all comparisons with a

p-value of 0.000 and a moderate effect) (

Table 2,

Figure 2). For uric acid, significant differences were observed between S and HTRH (

p=0.000, large effect), between S and HTRM (

p=0.024, large effect), and between S and HTRL (

p=0.000, large effect) (

Table 2,

Figure 2). About LDL, significant differences were identified between S and HTRH (

p=0.035, small effect), between S and HTRM (

p=0.001, moderate effect), and between S and HTRL (

p=0.035, small effect) (

Table 2,

Figure 2). As for total proteins, significant differences were found between S and HTRH (

p=0.019, small effect), between S and HTRM (p=0.008, small effect), and between S and HTRL (

p=0.004, small effect) (

Table 2,

Figure 2). No significant differences were found among the patient groups in NT Pro-BNP (

Table 2,

Figure 2).

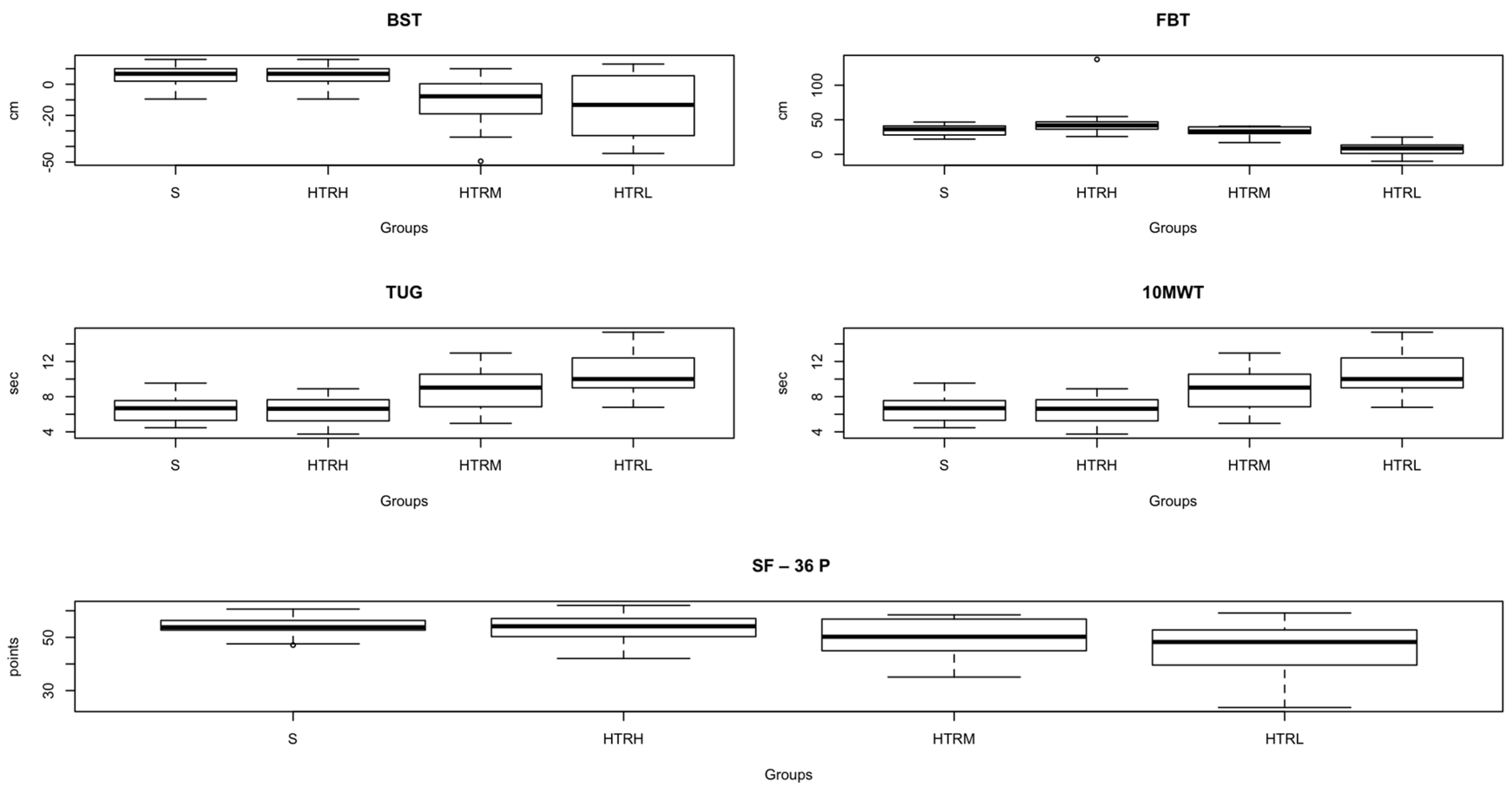

Given the SRT, no differences were detected among groups (Supplemental

Table 1). Concerning the BST, differences were found between S and HTRM (

p=0.001, small effect), S and HTRL (

p=0.003, small effect), HTRH and HTRM (

p=0.040, small effect) and HTRH and HTRL (

p=0.046, small effect) (

Table 2,

Figure 3).

Considering the FBT

, differences were detected between HTRH and HTRL (

p=0.002, great effect) (

Table 2,

Figure 3). Results of the TUG showed differences between S and HTRM (

p=0.003, small effect), S and HTRL (

p=0.000, moderate effect), HTRH and HTRM (

p=0.001, small effect), HTRH and HTRL (

p=0.000, moderate effect) and HTRM and HTRL (

p=0.046, small effect) (

Table 2,

Figure 3). Given data of the 10MWT

, differences were revealed between S and HTRM (

p=0.010, great effect), S and HTRL (

p=0.000, moderate effect) and HTRH and HTRL (

p=0.000, great effect) (

Table 2,

Figure 3).

Finally, the SF-36 (complementary assessment), within the mental health, no differences were observed among any of the groups (

Table 2). Concerning the section of the physical health, differences were found between S and HTRL (

p=0.002, small effect) and TPH and TPL (

p=0.001, small effect) (

Table 2,

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

The goals of this study were to determine the health status of a group of HTR and their level of PA and to compare their health status with that of a group of S. The study's hypothesis was partially confirmed, as HTRH did not exhibit better data than the other groups of patients across all variables, nor did they demonstrate similar health status to the S across all assessed variables. Overall, the S and HTRH were very similar in terms of BP, HR and blood analysis while HTRM and HTRL differed from both S and HTRH in these parameters. Regarding the cardiovascular, neuromuscular, functional mobility, and quality of life variables assessed in this study, HTRH showed the best results across all of them, followed by S, HTRM, and HTRL.

Considering the cardiovascular function assessment, notably, all groups exhibited healthy BP values. Thus, it is suggested that the patients of the current study expressed healthy BP levels due to PA, since HTR can improve their BP levels through PA [

22]. The fact that the basal HR of both S and HTR in the current study did not show any significant differences is a positive finding, since HTR often experience elevated resting HR [

23]. Thus, PA could serve as an effective tool in maintaining healthy basal HR levels for HTR. Concerning the 2MST, results suggest that the aerobic condition of S and HTRH are similar and that HTRH is better than the rest of patients. Consequently, the outcomes of this study underscore the potential of PA in aiding patients to attain and sustain aerobic fitness levels akin to those observed in S.

Given the neuromuscular assessment, in terms of handgrip strength, the HTRH and HTRM expressed the highest performance in the dominant and in the non-dominant hand. Observations in healthy individuals revealed a positive correlation between the PA levels and the handgrip strength levels [

24]. The present study's findings align with this trend; a higher level of PA among patients corresponds to a higher level of handgrip strength. In the ACT, no disparities emerged between S and HTR. This observation might stem from the fact that HTR often experience reduced muscle mass and strength owing to their immunosuppressive treatment [

25]. These findings deserve attention as they reflect a positive outcome; the patients' performance closely approximates that of healthy sedentary individuals. In the 30SCST, the HTRH achieves the highest scores. Therefore, it is suggested that PA holds the potential to contribute to the attainment and maintenance of robust lower extremity extension muscle strength and endurance in the HTR.

In respect to the blood analysis, no differences among groups were expressed in the values of glucose, total cholesterol, HDL, triglycerides, and albumin. Given that all groups in this study exhibited healthy values for these variables, it can be hypothesized that exercise has a positive effect on these variables in HTR. It is important to note that one of the side effects of immunosuppressive medication in HTR is an increase in blood glucose levels, increasing the risk of developing diabetes [

26] and the patients’ groups of the study presented healthy levels of this variable. Regarding the rest of the blood variables (creatinine, uric acid, LDL and total proteins levels), all groups of the study also expressed healthy values of them, but significative differences between S and HTR were observed. S showed healthier values than the HTR, what might be attributed to immunosuppressive´s toxic effects (HTR may exhibit elevated creatinine levels due to the immunosuppressive´s toxic effects) [

27]. Thus, it is suggested that PA could help to HTR to maintain these markers in healthy levels. No differences were found among the patient´s groups in the NT Pro-BNP levels. In studies with patients with heart failure, the NT Pro-BNP levels can be lowered with supervised exercise training [

28]. Thus, considering the present study´s results, a moderate level of PA could be the most beneficial for this variable in HTR, since HTRM expressed the lowest NT pro-BNP values.

Considering the functional assessment, a common trend is identified for the SRT, BST, FBT, TUG and 10MWT; engaging in PA graded as of high level, enables HTR to express performance levels in these outcomes comparable to those seen in S. The 10MWT´s results merge special consideration since the gait speed has been shown to be an indicator of disability [

29], health care utilization [

30] and survival [

31], in older adults. Thus, it is suggested a high level of PA is recommended for this aspect of the health of the HTR.

Finally, about the SF-36 questionnaire (complementary assessment), no differences among groups in terms of mental health were observed. However, differences were detected in physical health between S and HTRL, as well as between HTRH and HTRL. These findings suggest that engaging in graded high-intensity physical activities may foster a self-perceived state of physical health among HTR, akin to that of S.

Analyzing results of the primary outcomes within this study globally, it becomes evident that HTR engaging in high levels of PA exhibit a healthier status compared to those practicing moderate or low levels of activity. Remarkably, in some variables, patients with high PA levels even outperform to healthy sedentary individuals. Echoing this trend, the secondary variables follow a similar pattern, where heightened degrees of PA seem to be linked to better evaluation outcomes.

The results of this study can be applied to the rehabilitation process of HTR. Firstly, the weekly level of PA for HTR should be high (according to the IPAQ´s criteria). This level of PA should be achieved by practicing at least three days per week, although more days could be used (also according to the IPAQ´s criteria). The recommendations of Schmidt et al. (2021) (7) for the planning and execution of exercise training after heart transplantation should be considered when making this decision, including the current clinical condition, the individual comorbidities and possible transplant-related complications of the patients). Secondly, the topics of the supervised exercise for HTR could be all those that can improve the cardiovascular condition, the neuromuscular condition, basic blood parameters, the functional mobility condition and the quality of life of the patients. Finally, the tests used in this study to assess the health status of the patients might be also used to evaluate the effects of the exercise over HTR and as clinical outcomes for them. Additionally, the tests´ results of the present study of HTR with a high level of PA might serve as benchmarks.

This study has limitations. Firstly, there are significant differences in the number of men and women of the groups as well as in the mean age of the members of the groups. However, given the study's sample size, the results can be considered a valid reference for both sexes. And secondly, the PA levels of participants were assessed through self-reported measures as the IPAQ-L. However, the IPAQ has been widely used in numerous epidemiological studies globally and has undergone extensive validation in various populations and its widespread use allows for comparability with existing literature, promoting a more comprehensive understanding of PA patterns across different cohorts.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the results of this study reveal that heart transplant recipients who engage in high levels of physical activity exhibit better overall health compared to those who express moderate or low levels. Moreover, these high physically active patients achieve better results in certain health variables than healthy sedentary individuals. Thus, it is suggested that the weekly level of physical activity of heart transplant recipients should be high, what might help them to enhance their health and quality of life.

Author Contributions

I.S.R.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Roles/Writing - original draft and Writing - review & editing. J.I.R.B.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation and Writing - review & editing. P.A.F.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation and Writing - review & editing. L.S.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Roles/Writing - original draft and Writing - review & editing.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Research Ethics Committee of the University of León, ETICA-ULE-038-2021, approved and authorized the implementation of the study, which was conducted in accordance with the updated version of the Declaration of Helsinki. Additionally, it was registered as a clinical trial (clinicaltrials.gov ID: NCT05282342, date of registration 29/12/2021;

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05282342).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed written consent was obtained from all the participants.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sánchez-Enrique C, Jorde UP, González-Costello J. Heart Transplant and Mechanical Circulatory Support in Patients with Advanced Heart Failure. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2017, 70(5), 371–381. [CrossRef]

- Squires RW, Bonikowske AR. Cardiac rehabilitation for heart transplant patients: Considerations for exercise training. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2022, 70, 40-48. [CrossRef]

- Bernardi L, Radaelli A, Passino C, Falcone C, Auguadro C, Martinelli L, Rinaldi M, Viganò M, Finardi G. Effects of physical training on cardiovascular control after heart transplantation. Int J Cardiol. 2007, 118(3). [CrossRef]

- Nóbilo Pascoalino L, Gomes Ciolac E, Tavares AC, Ertner Castro R, Moreira Ayub-Ferreira S, Bacal F, Sarli Issa V, Alcides Bocchi E, Veiga Guimarães G. Exercise training improves ambulatory blood pressure but not arterial stiffness in heart transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015, 34(5). [CrossRef]

- Yardley M, Gullestad L, Bendz B, Bjørkelund E, Rolid K, Arora S, Nytrøen K. Long-term effects of high-intensity interval training in heart transplant recipients: A 5-year follow-up study of a randomized controlled trial. Clin Transplant. 2017, 31(1). [CrossRef]

- Yardley M, Gullestad L, Nytrøen K. Importance of physical capacity and the effects of exercise in heart transplant recipients. World J Transplant. 2018, 8(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt T, Bjarnason-Wehrens B, Predel HG, Reiss N. Exercise after Heart Transplantation: Typical Alterations, Diagnostics and Interventions. Int J Sports Med. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 1988, 8–14.

- Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003, 35(8), 1381-1395.

- Roman-Viñas B, Serra-Majem L, Hagströmer M, Ribas-Barba L, Sjöström M, Segura-Cardona R. International physical activity questionnaire: Reliability and validity in a Spanish population. Eur J Sport Sci. 2010, 10(5), 297–304. [CrossRef]

- Rikli RE, Jones CJ. Functional fitness normative scores for community residing older adults ages 60-94. J Aging Phys Act. 1999, 7, 160–179.

- Gibson AL, Wagner D, Heyward V. Advanced Fitness Assessment and Exercise Prescription. 8th ed. Human Kinetics. 2018.

- Jones CJ, Rikli RE, Beam WC. A 30-s chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength in community-residing older adults. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1999,70(2), 113-9. [CrossRef]

- Roberts HC, Denison HJ, Martin HJ, et al. A review of the measurement of grip strength in clinical and epidemiological studies: towards a standardised approach. Age Ageing. 2011, 40, 423-429.

- Wells KF, Dillon EK. The Sit and Reach—A Test of Back and Leg Flexibility. Res Q. 1952, 23(1), 115–118. [CrossRef]

- Duncan PW, Weiner DK, et al. Functional reach: a new clinical measure of balance. J Gerontol. 1990, 45(6):M192-197.

- Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991, 39(2), 142–148.

- Lang JT, Kassan TO, Devaney LL, Colon-Semenza C, Joseph MF. Test-Retest Reliability and Minimal Detectable Change for the 10-Meter Walk Test in Older Adults with Parkinson's disease. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2016, 39(4), 165–170. [CrossRef]

- Ware JE Jr. SF-36 Health Survey. In: Maruish ME, ed. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1999.

- Vilagut G, Ferrer M, Rajmil L, Rebollo P, Permanyer-Miralda G, Quintana JM, Santed R, Valderas JM, Ribera A, Domingo-Salvany A, Alonso J. El Cuestionario de Salud SF-36 español: una década de experiencia y nuevos desarrollos. Gac Sanit. 2005, 19(2). [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal R. Meta-analytic procedures for social research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991.

- Rengo G, Pagano G, Parisi V, Femminella GD, de Lucia C, Liccardo D, Cannavo A, Zincarelli C, Komici K, Paolillo S, Fusco F, Koch WJ, Filardi PP, Ferrara N, Leosco D. Changes of plasma norepinephrine and serum N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide after exercise training predict survival in patients with heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2014, 171(3), 201, 384-389. [CrossRef]

- Stehlik J, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, Benden C, Christie JD, Dipchand AI, Dobbels F, Kirk R, Rahmel AO, Hertz MI. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: 29th official adult heart transplant report-2012. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012, 31(10), 1052–1064. [CrossRef]

- Alphonsus CS, Govender P, Rodseth RN, Biccard BM. The role of cardiac rehabilitation using exercise to decrease natriuretic peptide levels in non-surgical patients: a systematic review. Perioper Med (Lond). 2019, 18;8:14. [CrossRef]

- Hermann TS, Dall CH, Christensen SB, Goetze JP, Prescott E, Gustafsson F. Effect of high intensity exercise on peak oxygen uptake and endothelial function in long-term heart transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2011, 1:536-541. [CrossRef]

- Wachter SB, McCandless SP, Gilbert EM, Stoddard GJ, Kfoury AG, Reid BB, McKellar SH, Nativi-Nicolau J, Saidi A, Barney J, McCreath L, Koliopoulou A, Wright SE, Fang JC, Stehlik J, Selzman CH, Drakos SG. Elevated resting heart rate in heart transplant recipients: innocent bystander or adverse prognostic indicator? Clin Transplant. 2015, 29(9), 829-34. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez SH, Carrero JJ, López DG, Alonso JA H, Alegre HM, Ruiz JR. Fitness and quality of life in kidney transplant recipients: case-control study. Med Clin (Engl Ed). 2016, 146(8), 335–338.

- Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Newman AB, et al. Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. Added value of physical performance measures in predicting adverse health-related events. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009, 57(2), 251–259.

- Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Penninx BWHJ, et al. Prognostic value of usual gait speed in well-functioning older people – results from the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005, 53(10), 1675–1680.

- Ostir GV, Berges I, Kuo YF, Goodwin JS, Ottenbacher KJ, Guralnik JM. Assessing gait speed in acutely ill older patients admitted to an acute care for elders hospital unit. Arch Intern Med. 2012, 172(4), 353–358.

- Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K, et al. Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA. 2011, 305(1), 50–58.

Figure 1.

STROBE diagram of the study´s phases. Abbreviations: SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure, HR, heart rate; 2MST, 2 Min Step Test; ACT, Arm Curt Test; 30SCST, 30-Second Chair Stand Test; HDL, high-density lipoproteins; LDL, low-density lipoproteins; NT Pro- BNP, N-terminal pro-B type Natriuretic peptide pro-hormonal; SRT, Sit and Reach Test; BST, Back Scratch Test; FBT, Functional Balance Test; TUG, Time and Up Go Test; 10MWT, 10 Meters Walking Test; SF – 36 M, The Short Form-36 Mental Health Survey; SF – 36 P, The Short Form-36 Physical Health Survey.

Figure 1.

STROBE diagram of the study´s phases. Abbreviations: SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure, HR, heart rate; 2MST, 2 Min Step Test; ACT, Arm Curt Test; 30SCST, 30-Second Chair Stand Test; HDL, high-density lipoproteins; LDL, low-density lipoproteins; NT Pro- BNP, N-terminal pro-B type Natriuretic peptide pro-hormonal; SRT, Sit and Reach Test; BST, Back Scratch Test; FBT, Functional Balance Test; TUG, Time and Up Go Test; 10MWT, 10 Meters Walking Test; SF – 36 M, The Short Form-36 Mental Health Survey; SF – 36 P, The Short Form-36 Physical Health Survey.

Figure 2.

The primary outcomes that expressed significant differences among groups. Abbreviations: S, healthy sedentary individuals; HTRH, transplanted with a high level of physical activity; HTRM, transplanted with a moderate level of physical activity; HTRL, transplanted with a low level of physical activity; 2MST, 2 Min Step Test; ACT, Arm Curt Test; 30SCST, 30-Second Chair Stand Test.

Figure 2.

The primary outcomes that expressed significant differences among groups. Abbreviations: S, healthy sedentary individuals; HTRH, transplanted with a high level of physical activity; HTRM, transplanted with a moderate level of physical activity; HTRL, transplanted with a low level of physical activity; 2MST, 2 Min Step Test; ACT, Arm Curt Test; 30SCST, 30-Second Chair Stand Test.

Figure 3.

The secondary outcomes that expressed significant differences among groups. Abbreviations: S, healthy sedentary individuals; HTRH, transplanted with a high level of physical activity; HTRM, transplanted with a moderate level of physical activity; HTRL, transplanted with a low level of physical activity; LDL, low-density lipoproteins; BST, Back Scratch Test; FBT, Functional Balance Test; TUG, Time and Up Go Test; 10MWT, 10 Meters Walking Test; SF – 36 P, The Short Form-36 Physical Health Survey.

Figure 3.

The secondary outcomes that expressed significant differences among groups. Abbreviations: S, healthy sedentary individuals; HTRH, transplanted with a high level of physical activity; HTRM, transplanted with a moderate level of physical activity; HTRL, transplanted with a low level of physical activity; LDL, low-density lipoproteins; BST, Back Scratch Test; FBT, Functional Balance Test; TUG, Time and Up Go Test; 10MWT, 10 Meters Walking Test; SF – 36 P, The Short Form-36 Physical Health Survey.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants.

| Characteristics |

S

(n=18) |

HTRH

(n=18) |

HTRM

(n=18) |

HTRL

(n=18) |

P-value |

Sex

(men/women)

|

7/11 |

17/1 |

13/5 |

14/4 |

0.003* |

Age

(years)

|

56.3 ± 12 |

54.2 ± 11.5 |

61.1 ± 14.5 |

67 ± 9 |

0.003$ |

Weight

(kg)

|

70 ± 14 |

74.1 ± 12.4 |

79 ± 27.5 |

72 ± 15 |

0.653$

|

Height

(cm)

|

161.1 ± 22 |

170.4 ± 6.5 |

161.5 ± 24.2 |

167 ± 10.5 |

0.291$

|

BMI

(kg/m2)

|

25.2 ± 5 |

25.5 ± 3.4 |

26 ± 4 |

26 ± 4.5 |

0.943&

|

Reason of

Transplant

|

- |

4 HM/ 2 IM/ 8 DM/ 4 OR |

1 HM/ 4 IM/ 6 DM/ 7 OR |

3 HM/ 7 IM/ 5 DM/ 3 OR |

- |

Table 2.

Comparison of the whole outcomes among the four groups of the participants; healthy sedentary individuals, transplanted with a high level of physical activity, transplanted with a moderate level of physical activity and transplanted with a low level of physical activity.

Table 2.

Comparison of the whole outcomes among the four groups of the participants; healthy sedentary individuals, transplanted with a high level of physical activity, transplanted with a moderate level of physical activity and transplanted with a low level of physical activity.

| Outcomes |

S

(n=18) |

HTRH

(n=18) |

HTRM

(n=18) |

HTRL

(n=18) |

p-value |

Effect size

(f/r) |

SBP

(mmHg)

|

133.3 ± 18 |

133.9 ± 18.1 |

132.4 ± 18.1 |

126.11 ± 15.1 |

0.645 |

- |

DBP

(mmHg)

|

75 ± 10 |

81.2 ± 10 |

81.3 ± 9.2 |

77.2 ± 10.1 |

0.060 |

- |

Basal HR

(bpm)

|

79 ± 11.7 |

87 ± 12 |

86 ± 18.5 |

87 ± 14 |

0.553 |

- |

2MST

(times)

|

75.4 ± 15 |

85 ± 35 |

65.3 ± 19.3 |

45 ± 21.2 |

0.000

|

S vs. HTRM; r = 0.30

S vs. HTRL; r = 0.70

HTRH vs. HTRM; r = 0.30

HTRH vs. HTRL; r = 0.70

HTRM vs. HTRL; r = 0.40 |

Grip strength

(dominant hand)

(kg)

|

29 ± 11.1

|

34.1 ± 9.1

|

29 ± 12.1

|

26.1 ± 9.3 |

0.025 |

S vs. HTRH; r = 0.30

HTRH vs. HTRM; r = 0.30

HTRH vs. HTRL; r = 0.40 |

Grip strength

(non-dominant hand)

(kg)

|

26 ± 10

|

31 ± 9

|

28 ± 12.1

|

24.3 ± 8.2

|

0.051 |

S vs. HTRH; r = 0.30

HTRH vs. HTRL; r = 0.30 |

ACT

(times)

|

9.2 ± 2.5 |

12 ± 5.1 |

9.4 ± 3 |

8.5 ± 2 |

0.246 |

HTRH vs. HTRL; r = 0.32 |

30SCST

(times)

|

13 ± 3 |

14 ± 6.2 |

10.1 ± 3.3 |

9 ± 2.5 |

0.000

|

S vs. HTRM; r = 0.50

S vs. HTRL; r = 0.60

HTRH vs. HTRM; r = 0.40

HTRH vs. HTRL; r = 0.50 |

Glucose

(mg/dl)

|

94 ± 14 |

94 ± 10.3 |

102 ± 21.5 |

94 ± 30.2 |

0.816 |

- |

Creatinine

(mg/dl)

|

0.81 ± 0.1 |

1.1 ± 0.3 |

1.1 ± 0.3 |

1.4 ± 0.5 |

0.000

|

S vs. HTRH; r = 0.61

S vs. HTRM; r = 0.57

S vs. HTRL; r = 0.65 |

Uric acid

(mg/dl)

|

4.5 ± 1.2 |

6.4 ± 1.2 |

5.9 ± 1.2 |

6.7 ± 1.5 |

0.000

|

S vs. HTRH; f = 1.70

S vs. HTRM; f = 0.90

S vs. HTRL; f = 1.30 |

Total colesterol

(mg/dl)

|

179 ± 35 |

161 ± 32.4 |

165.1 ± 28 |

173 ± 46 |

0.331 |

- |

HDL

(mg/dl)

|

60.4 ± 15 |

56 ± 16.4 |

67.3 ± 19.4 |

58 ± 25.1 |

0.388 |

- |

LDL

(mg/dl)

|

105± 24.5 |

86.3 ± 24.5 |

74 ± 22 |

81 ± 33 |

0.026 |

S vs. HTRH; r = 0.41

S vs. HTRM; r = 0.56

S vs. HTRL; r = 0.35 |

Triglycerides

(mg/dl)

|

100 ± 29 |

110 ± 54.1 |

120.4 ± 55 |

136.2 ± 80.4 |

0.490 |

- |

Total proteins

(g/dl)

|

7.2 ± 0.4 |

7 ± 1 |

7 ± 0.5 |

7 ± 0.5 |

0.042

|

S vs. HTRH; r = 0.33

S vs. HTRM; r = 0.42

S vs. HTRL; r = 0.45 |

Albumin

(g/dl)

|

5 ± 1 |

4.3 ± 0.5 |

4.5 ± 0.4 |

5 ± 2 |

0.740 |

- |

NT Pro-BNP*

(pg/ml)

|

- |

1434 ± 3125.3 |

765.3 ± 782 |

948.3 ± 1650 |

0.944 |

- |

SRT

(cm)

|

12.5 ± 8.1 |

13.3 ± 7.3 |

9.3 ± 7 |

11 ± 7 |

0.491 |

- |

BST(cm)

|

5.1 ± 7.1 |

0.14 ± 10 |

-9 ± 17 |

-10 ± 21 |

0.004

|

S vs. HTRM; r = 0.50

S vs. HTRL; r = 0.40

HTRH vs. HTRM; r = 0.40

HTRH vs. HTRL; r = 0.27 |

FBT

(cm)

|

34 ± 8.2 |

41 ± 8 |

33.2 ± 6.4 |

30 ± 12 |

0.004

|

HTRH vs. HTRL; f = 0.9 |

TUG

(sec)

|

7 ± 1.3 |

6.4 ± 2 |

9 ± 2.2 |

11 ± 2.5 |

0.000

|

S vs. HTRM; r = 0.66

S vs. HTRL; r = 1.32

HTRH vs. HTRM; r = 0.40

HTRH vs. HTRL; r = 0.22 |

10MWT

(sec)

|

3 ± 0.5 |

3.2 ± 0.5 |

4 ± 1 |

4.3 ± 2 |

0.000

|

S vs. HTRM; f = 1.26

S vs. HTRL; f = 0.80

HTRH vs. HTRL; f = 2.26 |

SF - 36 M

(points)

|

51 ± 9.1 |

53 ± 7.9 |

50 ± 10 |

52.4 ± 11.5 |

0.778 |

- |

SF - 36 P

(points)

|

54 ± 4 |

53.4 ± 5.2 |

50 ± 7.1 |

44.5 ± 10.2 |

0.007 |

S vs. HTRL; r = 0.50

HTRH vs. HTRL; r = 0.50 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).