Submitted:

24 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

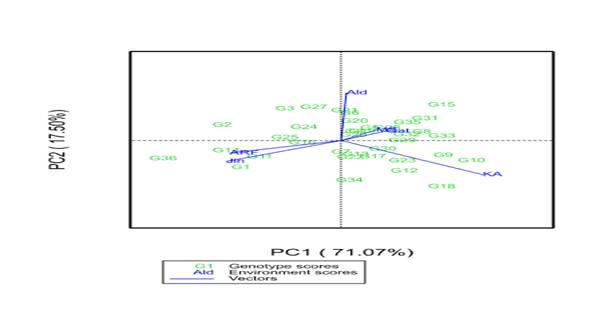

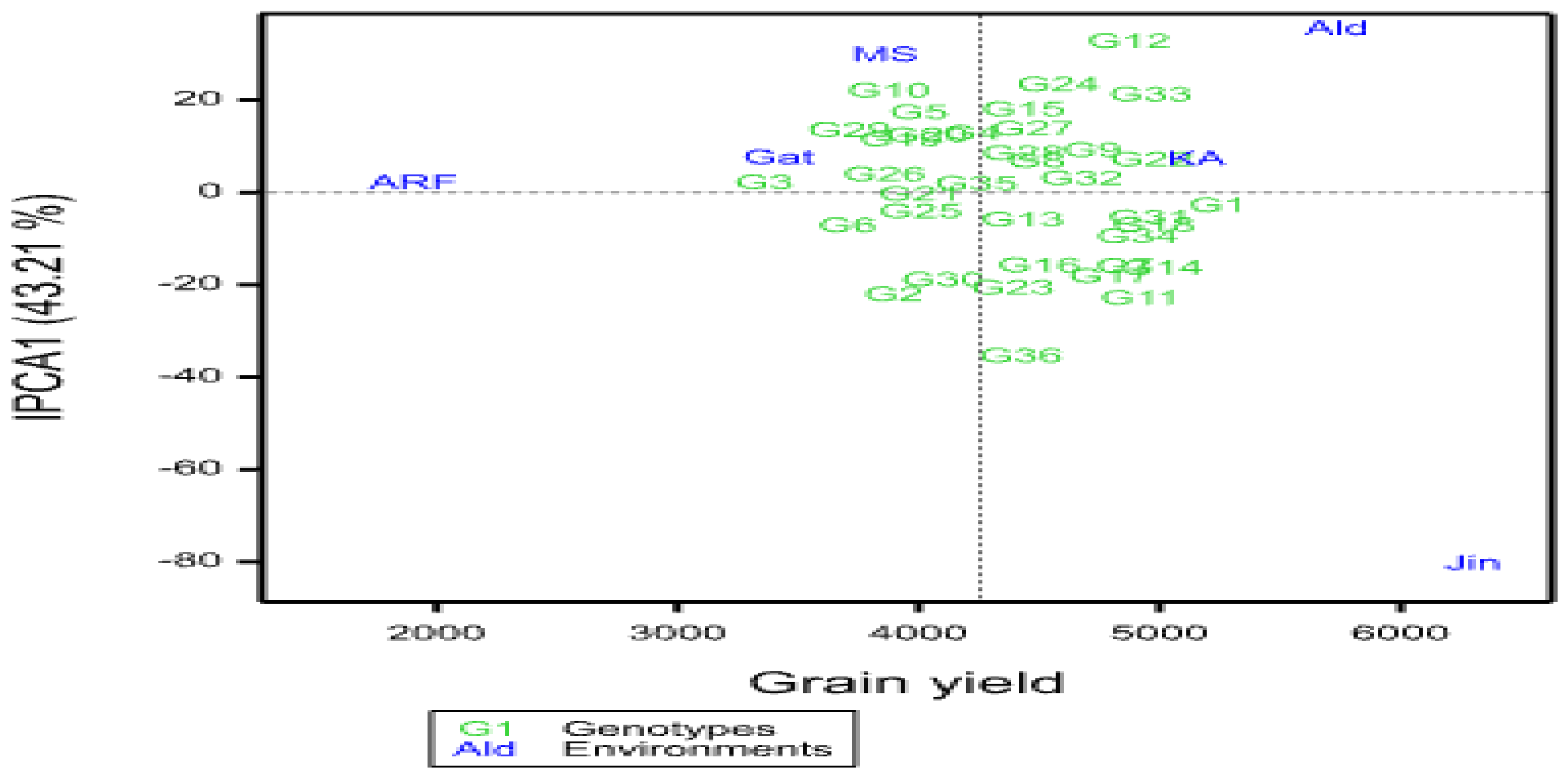

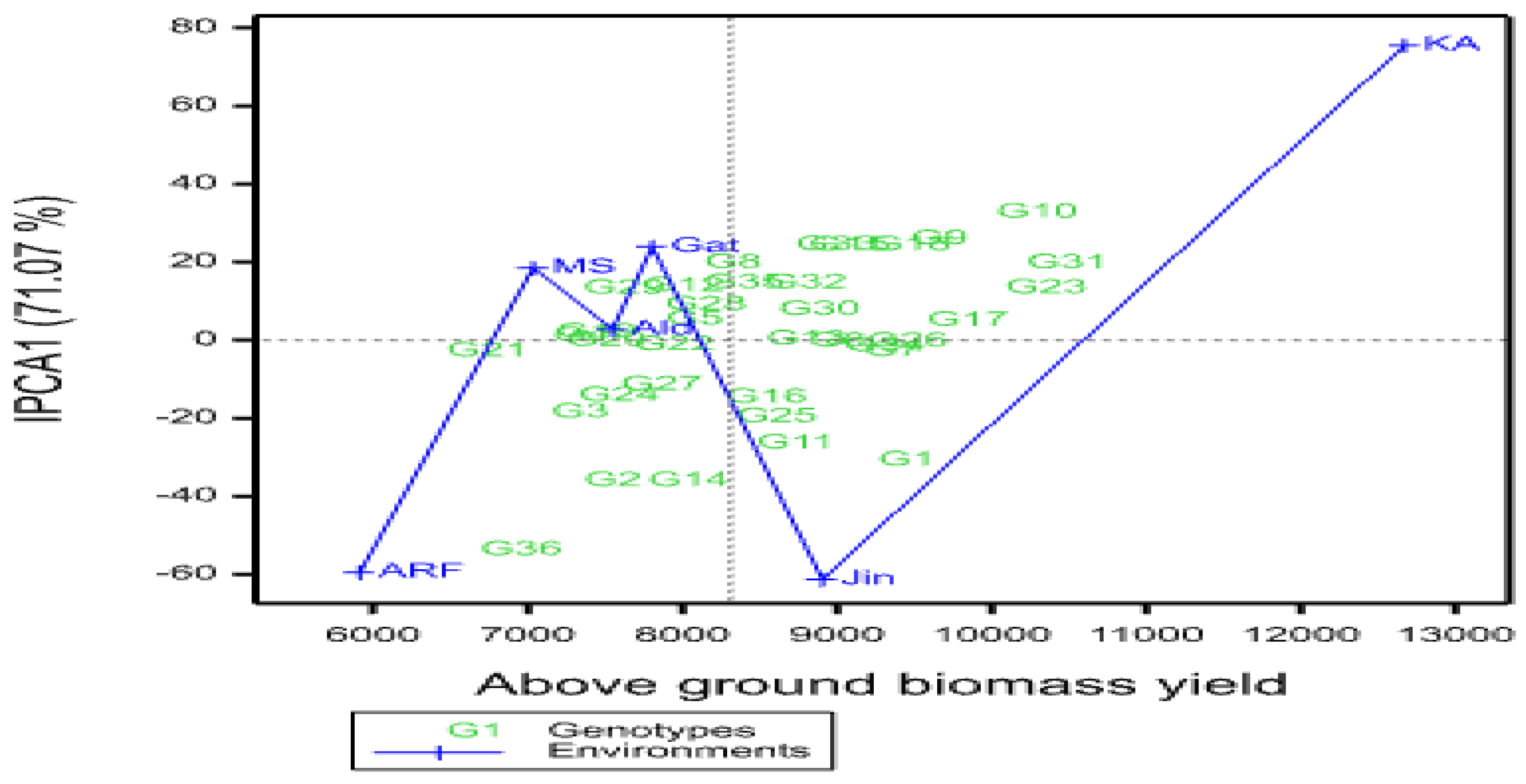

A multi-environment evaluation of sorghum genotypes was conducted across six environments in the 2021 main growing season in a randomized complete block design with three replications. The objectives of the study were to estimate the magnitude of genotypes by environment interaction (GEI) and grain yield stability of drought-tolerant sorghum genotypes across different environments. Data were subjected to analysis of variance, Additive Main Effects and Multiplicative Interaction (AMMI), and GGE biplot analysis. Combined analysis of variance revealed significant variations among genotypes, environments, and GEI for yield and yield-related traits, indicating that these factors significantly affected grain yield. The maximum mean grain yield value of genotypes due to the mean effect of the environment was obtained from G1 (5119.93kg ha-1), followed by G14 (4834.57 kg ha-1), and G18 (4801.20 ha-1), while the least mean grain yield was obtained from G3 (3314.50 kg ha-1). The multiplicative variance of the treatment sum of squares due to GEI was partitioned into four principal component axes (PCA). Sum squares of the first and second interaction principal component axis (IPCA) explained 71.07% and 17.50% of the GEI variation, respectively. The IPCA1&2 mean squares were highly significant (P≤0.01), indicating the adequacy of the AMMI model with the first two IPCAs for cross-validation of grain yield variation. The magnitude of the GEI sum squares was 3.9 times that of the genotype sum squares for grain yield, indicating the presence of substantial differences in genotypic responses across environments. The results of cultivar superiority measure (Pi), yield stability index (YSI), AMMI stability value (ASV), regression coefficient (bi), and deviation from regression (S2di) depicted that genotypes G18, G22, G31, and 32 were the most stable genotypes for grain yield and biomass yield, respectively. AMMI2 biplot showed Jinka, Alduba, and Kako were the most discriminating environments as indicated by the long distance from the origin; whereas testing locations Meioso and Gato with short vector length indicated that these locations had less discriminating power on the genotypes' performance. The study has provided precious information on the yield stability status of the sorghum genotypes and the best environments for future improvement programs in Ethiopia.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

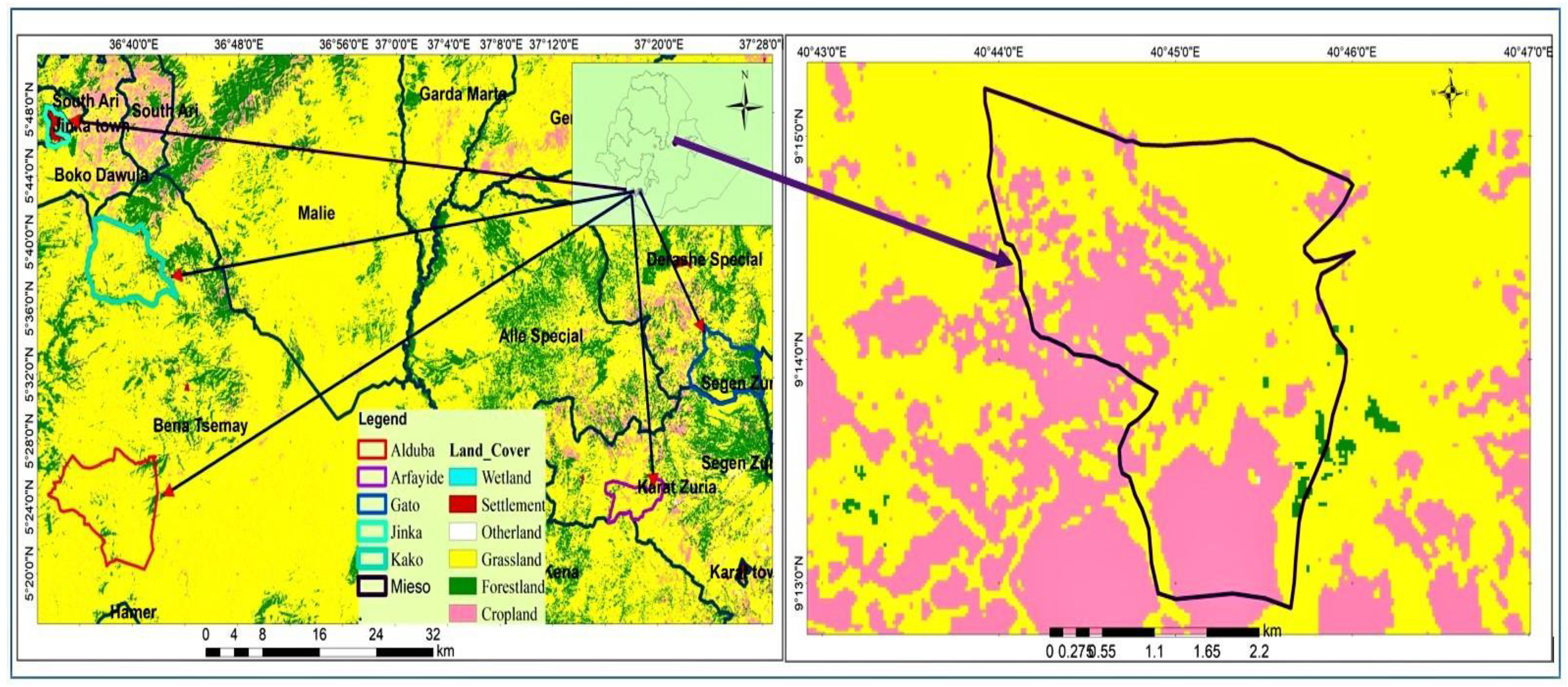

2.1. Description of the study area

2.2. Trial Materials

2.2.3. Experimental Design and Procedures

2.2.4. Data Collection

2.2.5. Data Analyses

2.2.5.1. Analysis of Variance for Individual Location and Combined Data Over the Location

2.2.5.2. Stability Analysis

2.2.5.3. AMMI Analysis

2.2.5.4. AMMI stability value (ASV)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Combined Analysis of Variance

3.2. Mean Performance of Genotypes

3.2.1. Grain Yield

| Genotype | Jinka | Kako | Alduba | Arfayide | Gato | Mieso | Mean |

| G1 | 7694abcd | 5852abc | 8440ab | 1816.0abcde | 3669.6a | 3248abcd | 5119.93 |

| G2 | 7749abcd | 3639c | 5096bcdefg | 1957.2abcde | 1455.8bc | 3311abcd | 3868.00 |

| G3 | 5176abcd | 3555c | 4992dcefg | 1331.6bcde | 1269.4c | 3563abcd | 3314.50 |

| G4 | 4957bcd | 6080abc | 4851defg | 1034.9e | 4092.1ab | 4859abc | 4312.33 |

| G5 | 4134d | 5354abc | 4277efg | 1333.3bcde | 3581.1a | 4596abc | 3879.23 |

| G6 | 5406abcd | 5347abc | 2677g | 1837.3abcde | 3490.6a | 2737bcd | 3582.48 |

| G7 | 7798abcd | 6844a | 5511bcdefg | 1503.7bcde | 3864.1ab | 2878bcd | 4733.13 |

| G8 | 5596abcd | 5665abc | 4533defg | 1639.2bcde | 3694.4ab | 5063abc | 4365.10 |

| G9 | 6058abcd | 5230abc | 7816abcd | 1612.5bcde | 3658.1a | 3211abcd | 4597.60 |

| G10 | 3879d | 4167bc | 5872abcdefg | 1960.0abcde | 2447.2abc | 3893abcd | 3703.03 |

| G11 | 8869ab | 5301abc | 6528abcdef | 1573.3bcde | 3173.0a | 3074abcd | 4753.05 |

| G12 | 4353cd | 4876abc | 8336abc | 2010.6abcd | 3675.1a | 4941abc | 4698.62 |

| G13 | 6425abcd | 6093abc | 5126bcdefg | 1277.0cde | 3887.6ab | 2737bcd | 4257.60 |

| G14 | 8333abc | 5267abc | 6654abcdef | 1917.5abcde | 3539.9a | 3296abcd | 4834.57 |

| G15 | 4467cd | 5923abc | 4109efg | 1475.6bcde | 3916.1ab | 5678a | 4261.45 |

| G16 | 7674abcd | 4350bc | 4543defg | 1787.7abcde | 3113.2a | 4485abcd | 4325.48 |

| G17 | 8209abc | 4350bc | 5333bcdefg | 1360.5bcde | 3665.4a | 4015abcd | 4488.82 |

| G18 | 7658abcd | 5722abc | 6383abcdef | 1158.5ed | 3415.7a | 4470abcd | 4801.20 |

| G19 | 4556cd | 4706abc | 5291bcdefg | 2234.1ab | 2585.8abc | 3141abcd | 3752.32 |

| G20 | 4636cd | 4706abc | 4365efg | 1410.4bcde | 3416.4a | 4563abc | 3849.47 |

| G21 | 5484abcd | 4765abc | 4230efg | 2020.7abcd | 3199.3a | 3300abcd | 3833.17 |

| G22 | 6019abcd | 7274a | 6519abcdef | 1583.5bcde | 3488.7a | 3530abcd | 4735.70 |

| G23 | 7649abcd | 5101abc | 4285efg | 2013.8abcd | 3161.9a | 3093abcd | 4217.28 |

| G24 | 4952bcd | 4303bc | 7467abcde | 1867.7abcde | 2579.5abc | 5270ab | 4406.53 |

| G25 | 6015abcd | 4134bc | 5956abcdef | 2136.3abc | 2985.3ab | 1778d | 3834.10 |

| G26 | 5548abcd | 3534c | 5600bcdefg | 1226.7cde | 2610.7abc | 3584abcd | 3683.90 |

| G27 | 5168abcd | 4862abc | 6198abcdef | 1459.3bcde | 4045.2ab | 4078abcd | 4301.75 |

| G28 | 5342abcd | 5559abc | 5353bcdefg | 2151.1abc | 3149.0a | 4007abcd | 4260.18 |

| G29 | 4067d | 4683abc | 5084bcdefg | 1828.5abcde | 3008.4ab | 2567bcd | 3539.65 |

| G30 | 7212abcd | 3957c | 4312efg | 2638.8a | 2722.7ab | 2723bcd | 3927.58 |

| G31 | 7339abcd | 5362abc | 6257abcdef | 1860.7abcde | 3676.4a | 4211abcd | 4784.35 |

| G32 | 6064abcd | 5849abc | 5481bcdefg | 2088.1abcd | 3451.3a | 4080abcd | 4502.23 |

| G33 | 5627abcd | 4548abc | 9022a | 1837.0abcde | 3316.1a | 4381abcd | 4788.52 |

| G34 | 7669abcd | 5647abc | 5931abcdefg | 1148.1de | 3758.4ab | 4252abcd | 4734.25 |

| G35 | 5644abcd | 4934abc | 5719abcdefg | 1983.8abcd | 3626.5a | 2489cd | 4066.05 |

| G36 | 9137a | 3554c | 3531fg | 1902.9abcde | 3353.8a | 4022abcd | 4250.12 |

| Mean | 6182.31 | 5030.36 | 5602.17 | 1721.61 | 3270.66 | 3753.44 |

3.3. Stability Analyses

3.3.1. Additive Main Effects and Multiplicative Interaction Analysis

| Source of variations | Grain yield | biomass | |||||

| df | MS | Percent | Accumulated | MS | Percent | Accumulated | |

| Genotype(G) | 35 | 1274121.2 | 6.22 | 6.22 | 1.99E+08 | 13.61 | 13.61 |

| Environments(E) | 5 | 99329874.8 | 69.29 | 75.51 | 9.93E+08 | 67.78 | 81.39 |

| Interactions(GxE) | 175 | 1003128.411 | 24.49 | 100.00 | 2.72E+08 | 18.61 | 100.00 |

| PC1 | 39 | 1944759.538 | 43.21 | 43.21 | 1.94E+08 | 71.07 | 71.07 |

| PC2 | 37 | 1454432.622 | 30.65 | 73.86 | 47685656 | 17.50 | 88.57 |

| PC3 | 35 | 703341.9714 | 14.02 | 87.88 | 25943186 | 9.52 | 98.10 |

| PC4 | 33 | 472733.0303 | 8.89 | 96.77 | 4233067 | 1.55 | 99.65 |

| Residuals | 31 | 182925.3226 | 3.23 | 953107 | 0.35 | ||

| Total | 215 | 3.33E+06 | 1.46E+09 | ||||

3.3. AMMI Stability Value (ASV)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Statistical database, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy. 2015, http://faostat3.fao.org/home/E.

- Vavilov, N.I. The origin, variation, immunity and breeding of cultivated plants. Chronica Botanica, 1951, 13:1-366. [CrossRef]

- Seyoum, A., Gebreyohannes, A., Nega, A., Nida, H., Tadesse, T., Tirfessa, A. and Bejiga, T. Performance evaluation of Sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] genotypes for grain yield and yield related traits in drought prone areas of Ethiopia. Advances in Crop Science and Technology. 2019, 7(2), p.423.

- Belete, T. and Bediru, N. Yielding and stability appraisal of released varieties of sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench.]. Journal of Agricultural Research Advances. 2020. Vol 02 No 4, pp 31-35/31.

- Belay, F., Mekbib, F. and Tadesse, T. Genotype by environment interaction and grain yield stability of Striga resistant sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] genotypes in Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Crop Science. 2020, 8(2), pp.79-99.

- Anum, W., Yasmeen, S., Ali, L., Riaz, U., Ali, A., Ahmed, R.I., Akhtar, I., Manzoor, N., Ur-Rahman, A., Maan, N.A. and Hussain, A. Environment X Genetic Stability of Different Sorghum Bicolor Varieties/Promising Lines Under Various Environmental Conditions. AGJSR. 2021, 39 (2): 69-81. [CrossRef]

- Enyew, M., Feyissa, T., Geleta, M., Tesfaye, K., Hammenhag, C. and Carlsson, A.S. Genotype by environment interaction, correlation, AMMI, GGE biplot and cluster analysis for grain yield and other agronomic traits in sorghum [Sorghum bicolor L. Moench],” Plos one. 2021, 16(10), p.e0258211.

- Abate, M. Genotype by environment interaction and yield stability analysis of open pollinated maize varieties using AMMI model in Afar Regional State, Ethiopia. Journal of Plant breeding and crop science. 2020. 12(1), pp.8-15.

- Belay, N. Genotype-by-environment interaction of maize testcross hybrids evaluated for grain yield using GGE biplots. International Journal of Food Science and Agriculture. 2022, 6(2), 216-227.

- Alemu, G., Dabi, A., Geleta, N., Duga, R., Solomon, T., Zegaye, H., Getamesay, A., Delesa, A., Asnake, D., Asefa, B. and Shewaye, Y. Genotype× environment interaction and selection of high yielding wheat genotypes for different wheat-growing areas of Ethiopia. Am. J. Biosci. 2021, 9, pp.63-71. [CrossRef]

- Jifar, H., Assefa, K., Tesfaye, K., Dagne, K. and Tadele, Z. Genotype-by-environment interaction and stability analysis in grain yield of improved Tef ( Eragrostis tef) varieties evaluated in Ethiopia. Journal of experimental agriculture international. 2019, 35(5), pp.1-13. [CrossRef]

- Haile, S. Genotype x Environment Interaction and Grain Yield Stability of Finger Millet [Eleusine coracana(L) subsp. Coracana] Varieties in Eastern and Western, Ethiopia. MSc Thesis, Haramaya, Haramaya University.2020.

- IBGR and ICRISAT. Descriptors for sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench]. International Board for Plant Genetic Resources. 1993. Rome, Italy, p.432.

- SAS Institute. SAS/STAT User’s Guide. 2004. SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina. USA.

- Angela, P., Mateo, V., Gregorio, A., Francisco, R., Marco, L., José, C and Juan, B. GEAR (Genotype x Environment Analysis with R for Windows) Version 4.1.2016. CIMMYT Research Data and Software Repository Network. The Crop Journal. 2020, Volume 8, Issue 5, 745-756.

- Gomez, K.A. and Gomez, A.A. Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research. 2nd Edition John Wiley and Sons Inc. 1984, New York. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.S. Multivariate analysis. Supplement to the journal of the royal statistical society.1947, 9(2), pp.176-197.

- Hussein, M.A., Bjornstad, A.S. and Aastveit, A.H. SASG× ESTAB: A SAS program for computing genotype× environment stability statistics. Agronomy journal. 2000, 92(3), pp.454-459. [CrossRef]

- Purchase, J.L. Parametric analysis to describe genotype x environment interaction and yield stability in winter wheat. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Agronomy, Faculty of Agriculture of the University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. 1997.http://hdl.handle.net/11660/1966.

- Amare, A., Mekbib, F., Tadesse, W. and Tesfaye, K. Genotype X environment interaction and stability of drought tolerant bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes in Ethiopia. International Journal of Research. 2020, 6(3), pp.26-35.

- Belay, F., Mekbib, F. and Tadesse, T. Genotype by environment interaction and grain yield stability of Striga resistant sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.)Moench] genotypes in Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Crop Science. 2020, 8(2), pp.79-99.

- Yitayeh, Z.S., Mindaye, T.T. and Bisetegn, K.B. AMMI and GGE Analysis of GxE and Yield Stability of Early Maturing Sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.)Moench] Genotypes in Dry Lowland Areas of Ethiopia. Adv. in Crop Sci. T.2019.

- Mulugeta, B., Tesfaye, K., Geleta, M., Johansson, E., Hailesilassie, T., Hammenhag, C., Hailu, F. and Ortiz, R. Multivariate analyses of Ethiopian durum wheat revealed stable and high yielding genotypes. PloS One. 2022, 17(8), p.e0273008. [CrossRef]

- Amare, A., Mekbib, F., Tadesse, W. and Tesfaye, K. Screening of drought tolerant bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes using yield based drought tolerance indices. Ethiopian Journal of Agricultural Sciences. 2019, 29(2), pp.1-16.

- Crossa, J., Gauch Jr, H.G. and Zobel, R.W. Additive main effects and multiplicative interaction analysis of two international maize cultivar trials. Crop science. 1990, 30(3), pp.493-500. [CrossRef]

- Ganta, T., Mekbib, F., Amsalu, B., & Tadele, Z. Genotype by Environment Interaction and Yield Stability of Drought Tolerant Mung Bean [Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek] Genotypes in Ethiopia. Journal of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences. 2022, 7 (1), 43-62.

- Legesse, A. and Mekbib, F. Genotype X environment interaction and stability of early maturing sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] genotypes in Ethiopia, 2015. MSc. Thesis, Alemaya University of Agriculture, Ethiopia.

- Belete, T., Tulu, L.A. and Senbetay, T. Evaluation of finger millet [Eleusine coracana (L.) Gaertn.] varieties at different locations of southwestern Ethiopia. Journal of Genetic and Environmental Resources Conservation. 2020, 8(2), pp.9-17.

- Yan, W. and Rajcan, I. Biplot analysis of test sites and trait relations of soybean in Ontario. Crop science. 2002, 42(1), pp.11-20.

- Yan, W. and Tinker, N.A. Biplot analysis of multi-environment trial data: Principles and applications. Canadian journal of plant science, 2016, 86(3), pp.623-645. [CrossRef]

- Jifar, H., Assefa, K., Tesfaye, K., Dagne, K. and Tadele, Z. Genotype-by-environment interaction and stability analysis in grain yield of improved tef (Eragrostis tef) varieties evaluated in Ethiopia. Journal of experimental agriculture international. 2019, 35 (5), pp.1-13. [CrossRef]

- Worede, F., Mamo, M., Assefa, S., Gebremariam, T. and Beze, Y. Yield stability and adaptability of lowland sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] in moisture-deficit areas of Northeast Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture. 2020, 6(1), p.1736865.

- Birhanu, C., Bedada, G., Dessalegn, K., Lule, D., Chemeda, G., Debela, M. and Gerema, G. Genotype by environment interaction and grain yield stability analysis for Ethiopian sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] genotypes. Int. J. Plant Breeding and Crop Sci. 2021, 8, pp.975-986.

- Worede, F., Tarekegn, F. and Teshome, K. Simultaneous selection for grain yield and stability of sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] genotypes in Northeast Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research. 2021, 17(10), pp.1316-1323.

- Gauch Jr, H.G. and Zobel, R.W. Optimal replication in selection experiments,” Crop Science. 1996, 36(4), pp.838-843.

- Yan, W., Hunt, L.A., Sheng, Q. and Szlavnics, Z. Cultivar evaluation and mega-environment investigation based on the GGE biplot” Crop science, 2000, 40(3), pp.597-605.

- Al-Naggar, A.M.M., Abd El-Salam, R.M., Hovny, M.R.A. and Yaseen, W.Y. Genotype× Environment Interaction and Stability of Sorghum bicolor Lines for Some Agronomic and Yield Traits in Egypt. Asian Journal of Agricultural and Horticultural Research. 2018, pp.1-14. [CrossRef]

- Admas, S. and Tesfaye, K. (2017), Genotype-by-environment interaction and yield stability analysis in sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] genotypes in North Shewa, Ethiopia. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Agriculture and Environment. 2017, 9(1), pp.82-94.

- Alemu, B., Negash, G., Raga, W. and Abera, D. Multi-locations evaluation of sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] genotypes for grain yield and yield related traits at western Oromia, Ethiopia,” Journal of Cereals and Oilseeds. 2020, 11(2), pp.44-51.

| Serial no. | Genotypes | Code | Region | Zone | District |

| 1 | 27907 | G1 | South West | Bench Maji | Gura Farda |

| 2 | 69321 | G2 | South | Konso | Karat zuria |

| 3 | 69331 | G3 | South | Ari | Bakodawla |

| 4 | 70084 | G4 | South | Konso | Karat zuria |

| 5 | 70154 | G5 | South | Dirashe | Dirashe |

| 6 | 70229 | G6 | South | Dirashe | Dirashe |

| 7 | 71010 | G7 | South | Konso | Kena |

| 8 | 74667 | G8 | South | Dirashe | Dirashe |

| 9 | 74669 | G9 | South | Konso | Segen zuria |

| 10 | 74679 | G10 | South | Konso | Segen zuria |

| 11 | 74680 | G11 | South | Dirashe | Dirashe |

| 12 | 74684 | G12 | South | Dirashe | Dirashe |

| 13 | 74686 | G13 | South | Dirashe | Dirashe |

| 14 | 74691 | G14 | South | Dirashe | Dirashe |

| 15 | 74693 | G15 | South | Dirashe | Dirashe |

| 16 | 74704 | G16 | South | Dirashe | Dirashe |

| 17 | 74705 | G17 | South | Dirashe | Dirashe |

| 18 | 200617 | G18 | South | Dirashe | Dirashe |

| 19 | 201453 | G21 | South | Dirashe | Dirashe |

| 20 | 204602 | G22 | South | Dirashe | Gumade |

| 21 | 204619 | G23 | South | Konso | Karat zuria |

| 22 | 204629 | G24 | South | Konso | Segen zuria |

| 23 | 204631 | G25 | South | Konso | Segen zuria |

| 24 | 204633 | G26 | South | Konso | Kena |

| 25 | 204634 | G27 | South | Konso | Kena |

| 26 | 206285 | G28 | South | Konso | Karat zuria |

| 27 | 206286 | G29 | South | Burji | Karat zuria |

| 28 | 213008 | G30 | South | Konso | Kena |

| 29 | 213017 | G31 | South | Burji | Burji |

| 30 | 213019 | G32 | South | Dirashe | Dirashe |

| 31 | 213026 | G33 | South | Gamo | Bonke |

| 32 | 214010 | G34 | South | South omo | Hamer Bena |

| 33 | 214109 | G35 | South | South omo | Benatesmy |

| 34 | 216906 | G36 | South | Gamo | Gofa Zuria |

| 35 | Dekeba( check ) | G19 | |||

| 36 | Melkam(check) | G20 |

| Trait | DF | MD | GFP | PHT | ||||||||||

| Source of variation | df | MS | Percent | MS | Percent | MS | Percent | MS | Percent | |||||

| Environment(E) | 5 | 3026.16** | 28.64 | 17357.93** | 56.66 | 8170.96** | 44.99 | 120104.56** | 28.38 | |||||

| Genotype (G) | 35 | 150.20** | 9.95 | 150.84** | 3.45 | 77.04** | 3.01 | 13494.25** | 22.32 | |||||

| GxE interactions Rep(E) Error |

175 12 420 |

71.95** 226.2** 40.77 |

23.84 5.14 |

61.46** 3167.80** |

7.02 24.82 |

72.61** 1337.36** |

13.97 17.64 |

2023.64** 9735.66** |

16.74 5.52 |

|||||

| 32.42 | 29.39 | 8.06 | 44.27 | 20.45 | 44.27 | 27.05 | ||||||||

|

Trait |

PL | PY | PW | SW | ||||||||||

| Source of variation | df | MS | Percent | MS | Percent | MS | Percent | MS | Percent | |||||

| Environment(E) | 5 | 3631.75** | 34.65 | 418611.32** | 58.85 | 366168.77** | 40.70 | 419507928** | 47.34 | |||||

| Genotype (G) | 35 | 137.87** | 9.21 | 2025.96* | 3.18 | 7848.58** | 6.11 | 15762275** | 12.45 | |||||

| GxE interactions Rep(E) Error |

175 12 420 |

85.18** 82.24** 32.21 |

28.44 1.88 25.82 |

3042.56** 9413.07** 1779.34 |

14.97 3.18 21.01 |

5260.07** 19546.56** 2946.62 |

20.46 5.21 27.51 |

2353159** | 9.29 | |||||

| 70190040** | 19.01 | |||||||||||||

| 1255266 | 11.90 | |||||||||||||

|

Trait |

BM | TKW | GY | HI | ||||||||||

| Source of variation | df | MS | Percent | MS | Percent | MS | Percent | MS | Percent | |||||

| Environment(E) | 5 | 597883554** | 43.59 | 1799.68** | 43.90 | 298875131** | 48.30 | 419507928** | 39.58 | |||||

| Genotype (G) | 35 | 16989501** | 8.67 | 74.47** | 12.72 | 3897432** | 4.14 | 15762275** | 7.68 | |||||

| GxE interactions Rep(E) Error |

175 12 420 |

4667812** 103932563** 2881993 |

11.91 18.18 17.65 |

16.20** 75.54** 12.27 |

13.83 4.42 0.06 |

3031950** 12269443** 1877757 |

16.98 4.77 25.81 |

2353159** | 21.12 | |||||

| 70190040** | 3.24 | |||||||||||||

| 1255266 | 28.38 | |||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).