Submitted:

09 August 2024

Posted:

13 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

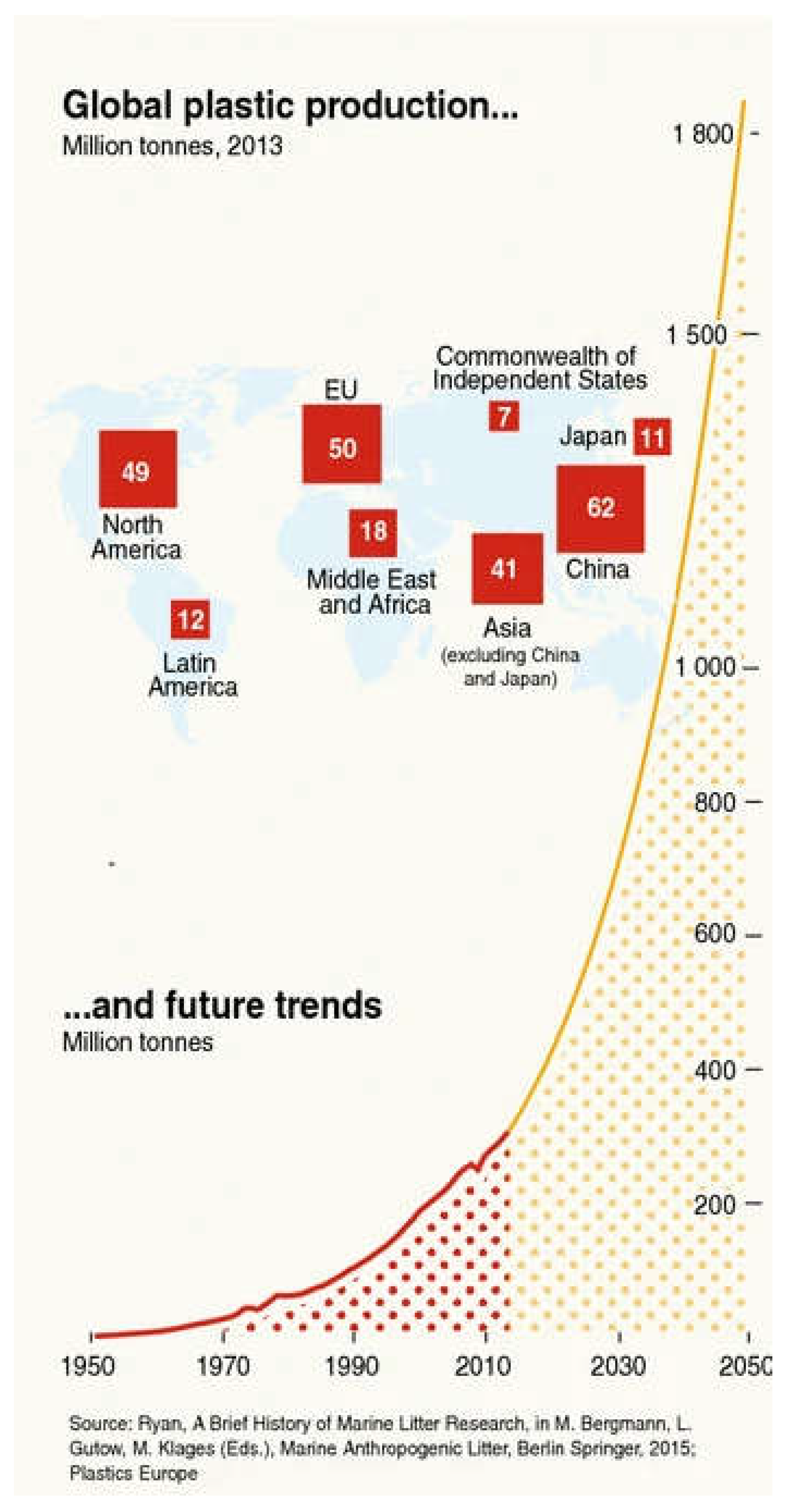

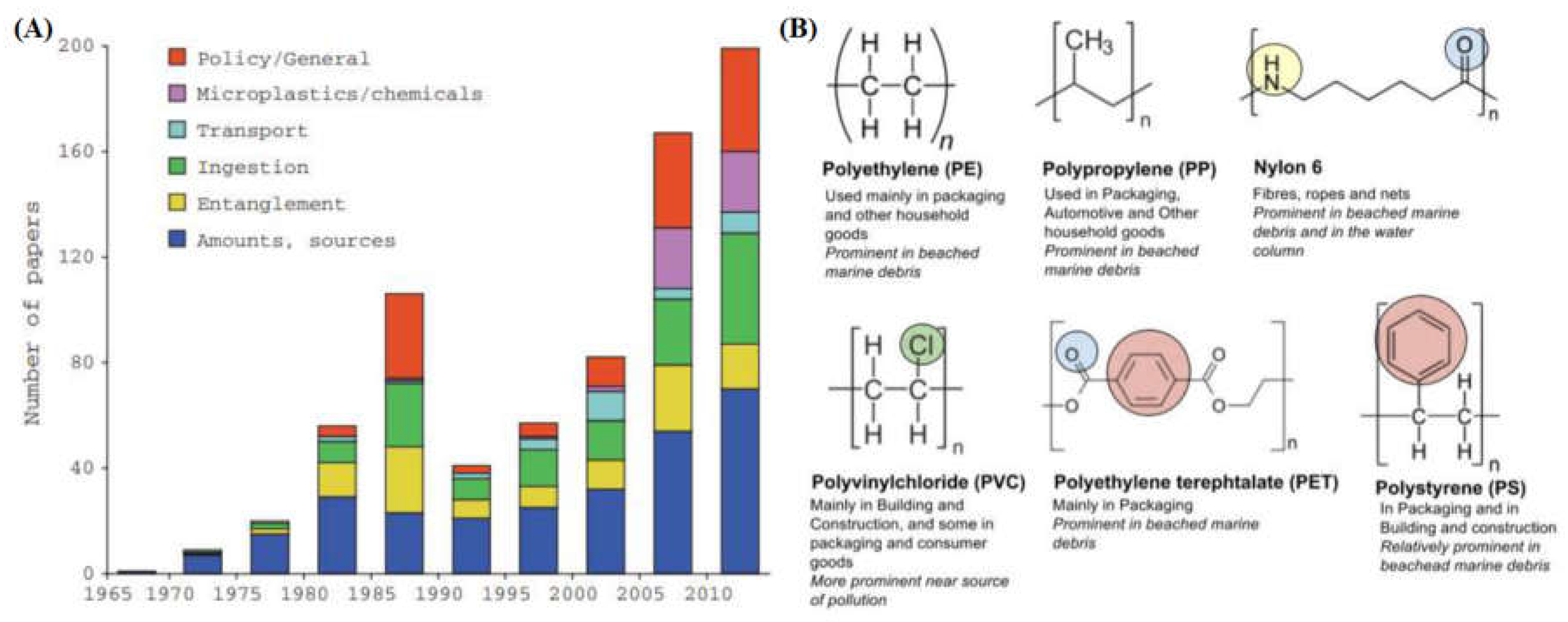

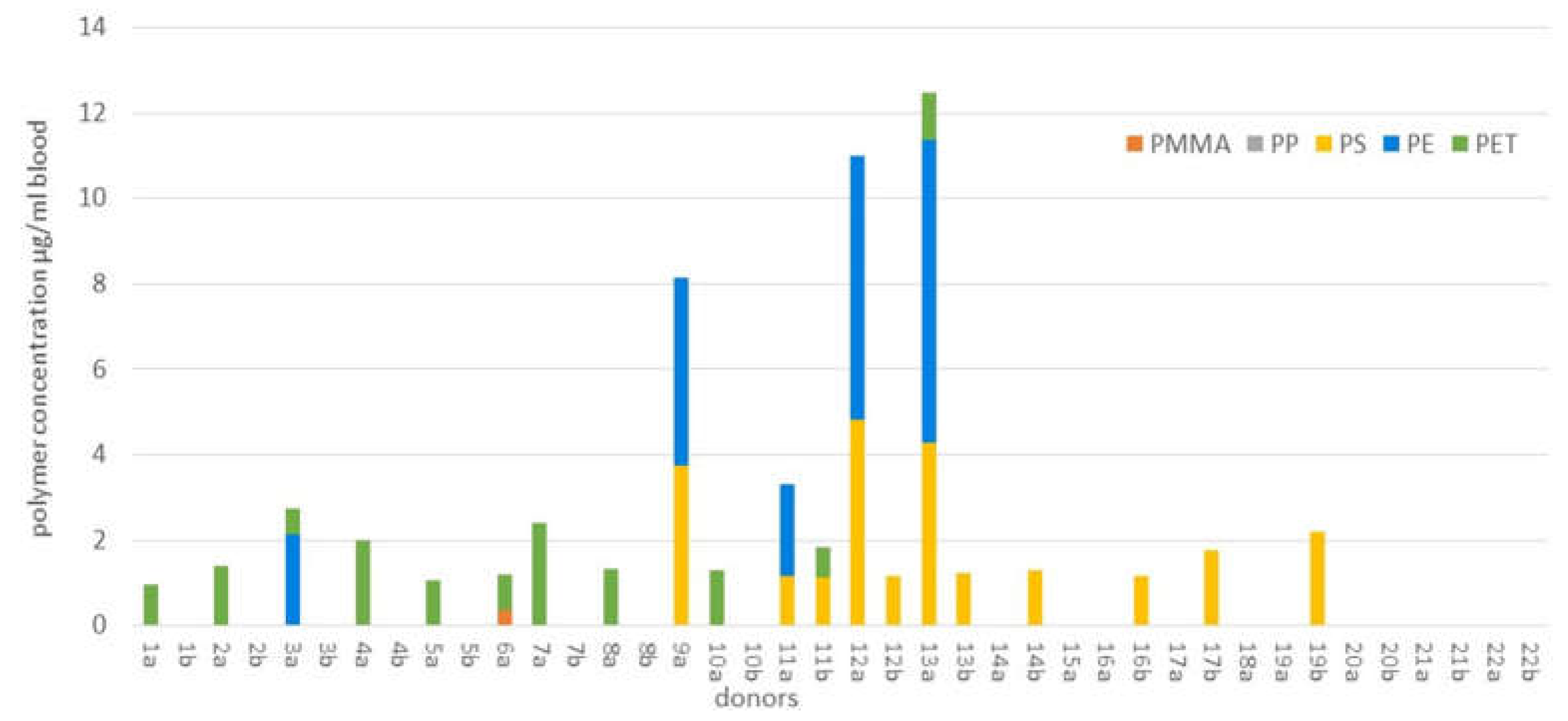

1. Introduction

2. Characterization

2.1. Characterization Overview (Introduction)

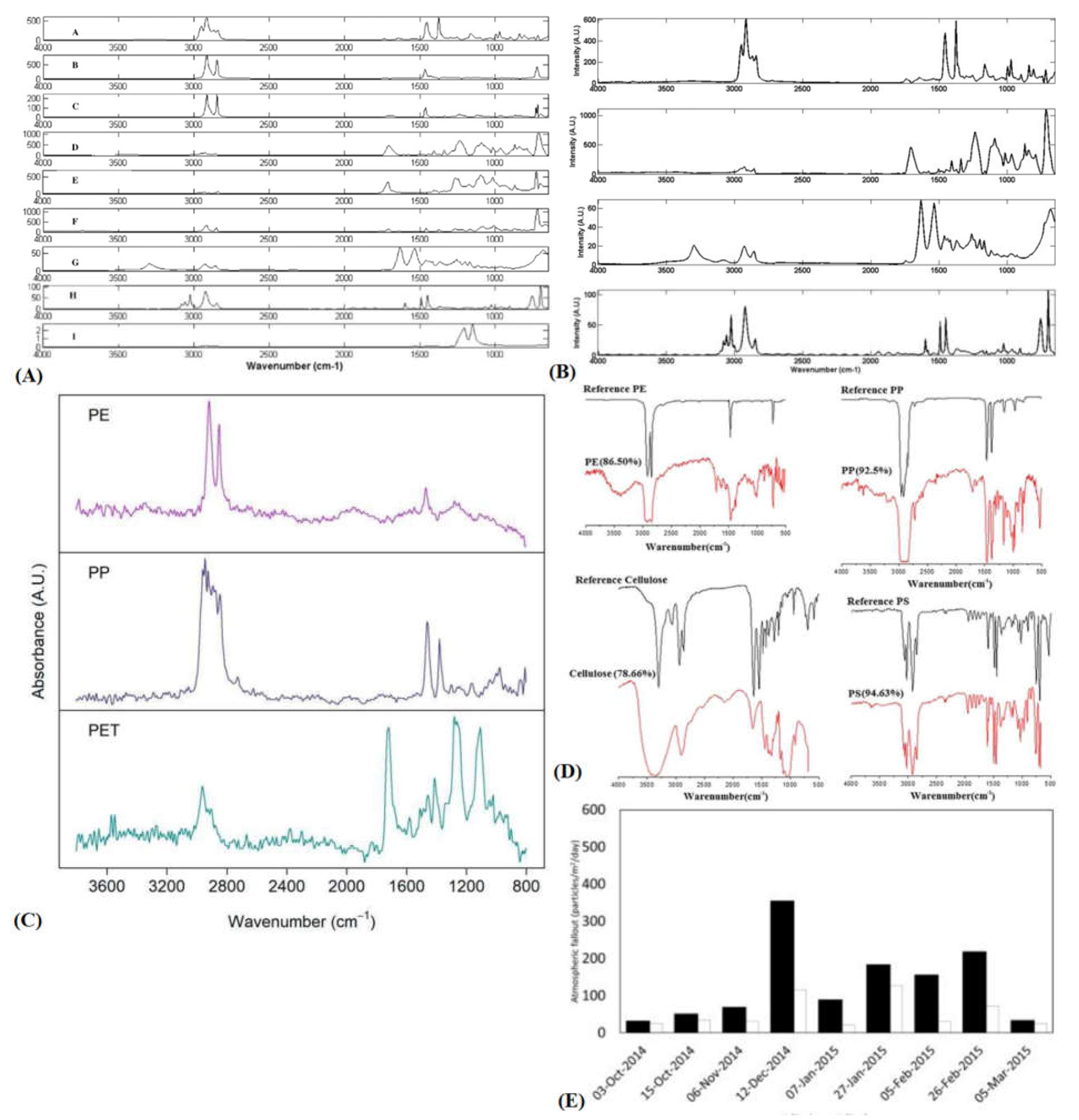

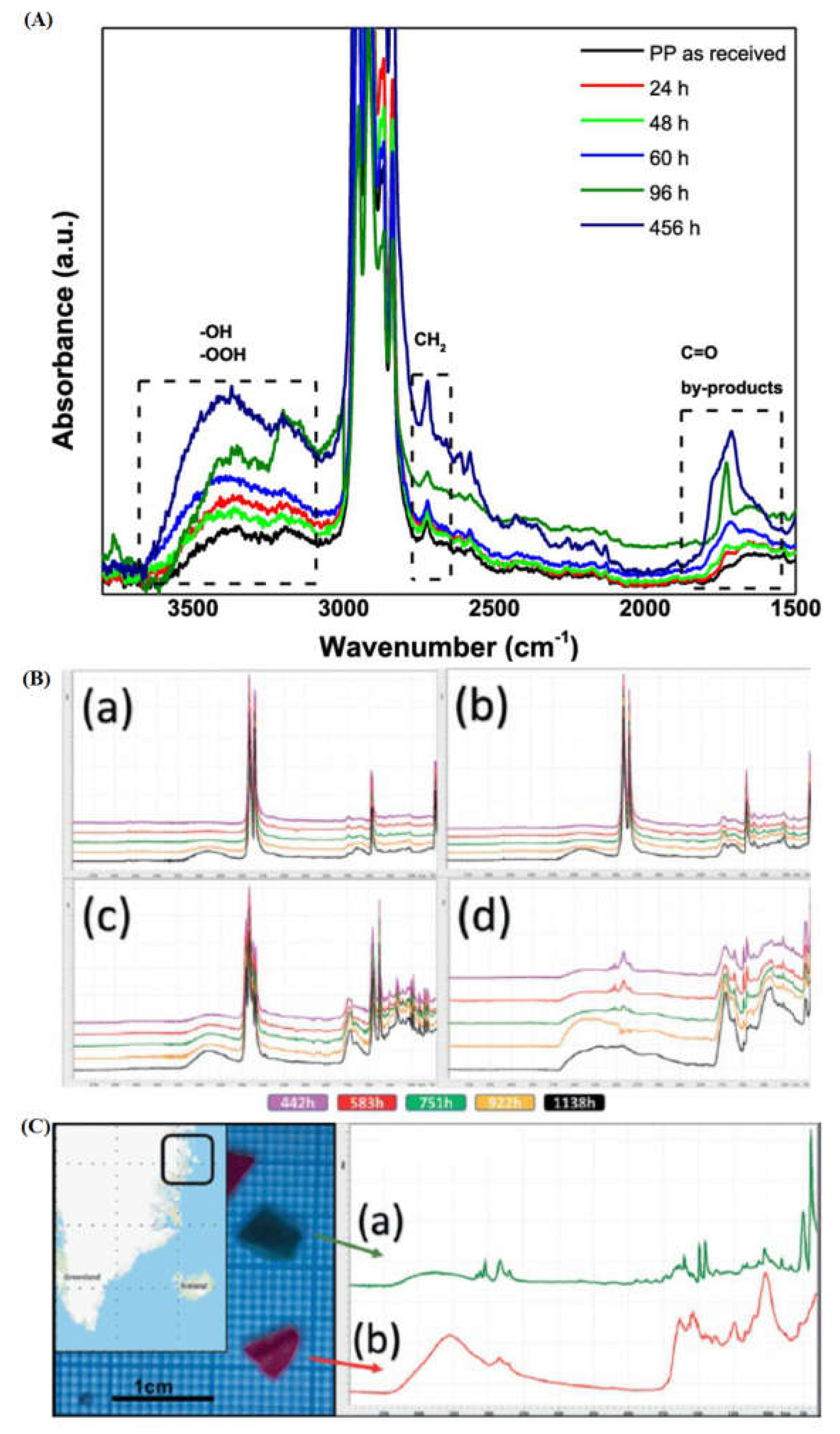

2.2. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

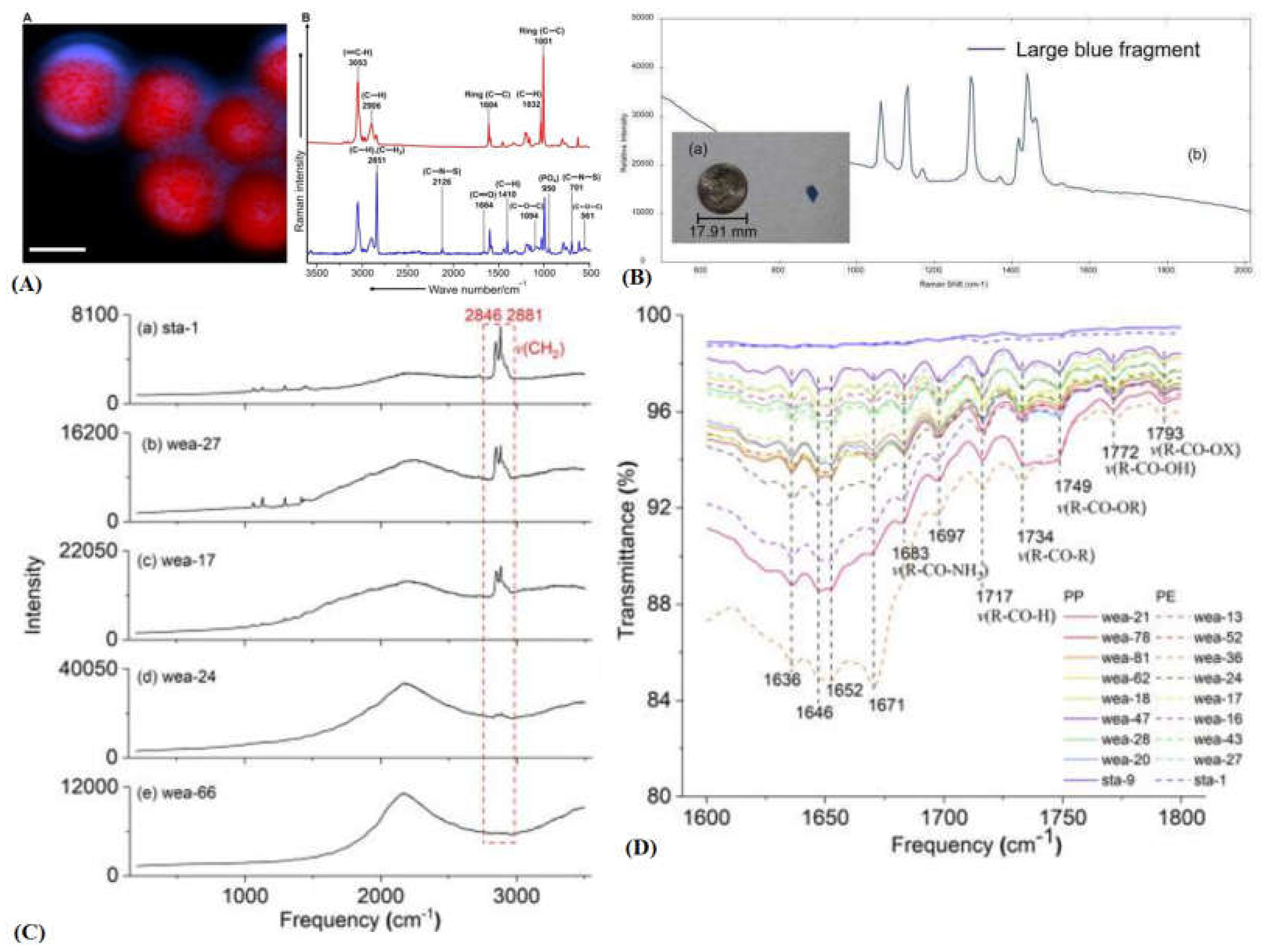

2.3. Raman Spectroscopy

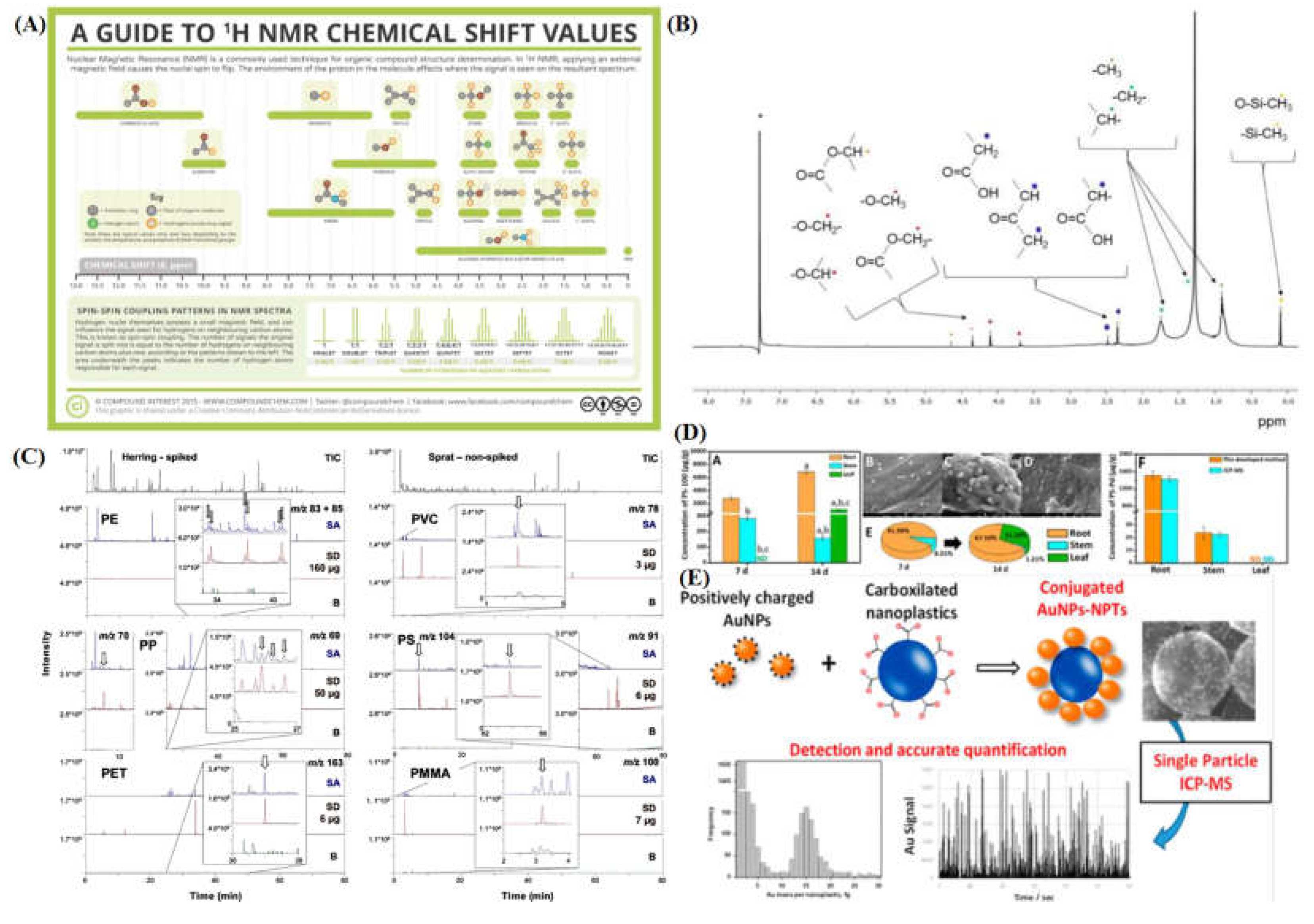

2.4. Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (H-NMR)

2.5. Pyrolysis: Curie Point-Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry and Induced Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry

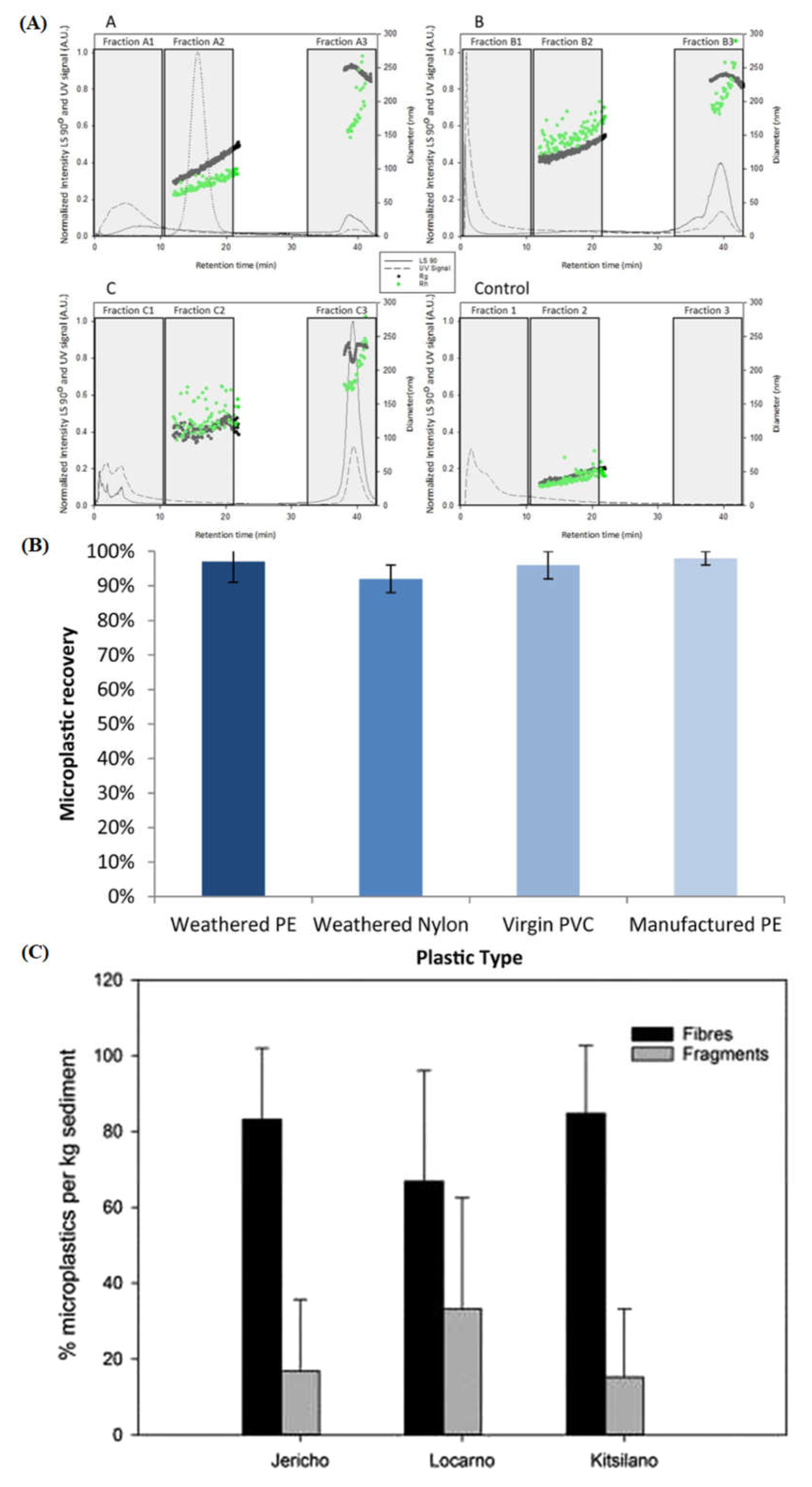

2.6. Miscellaneous Identification, Isolation, and Quantification Techniques

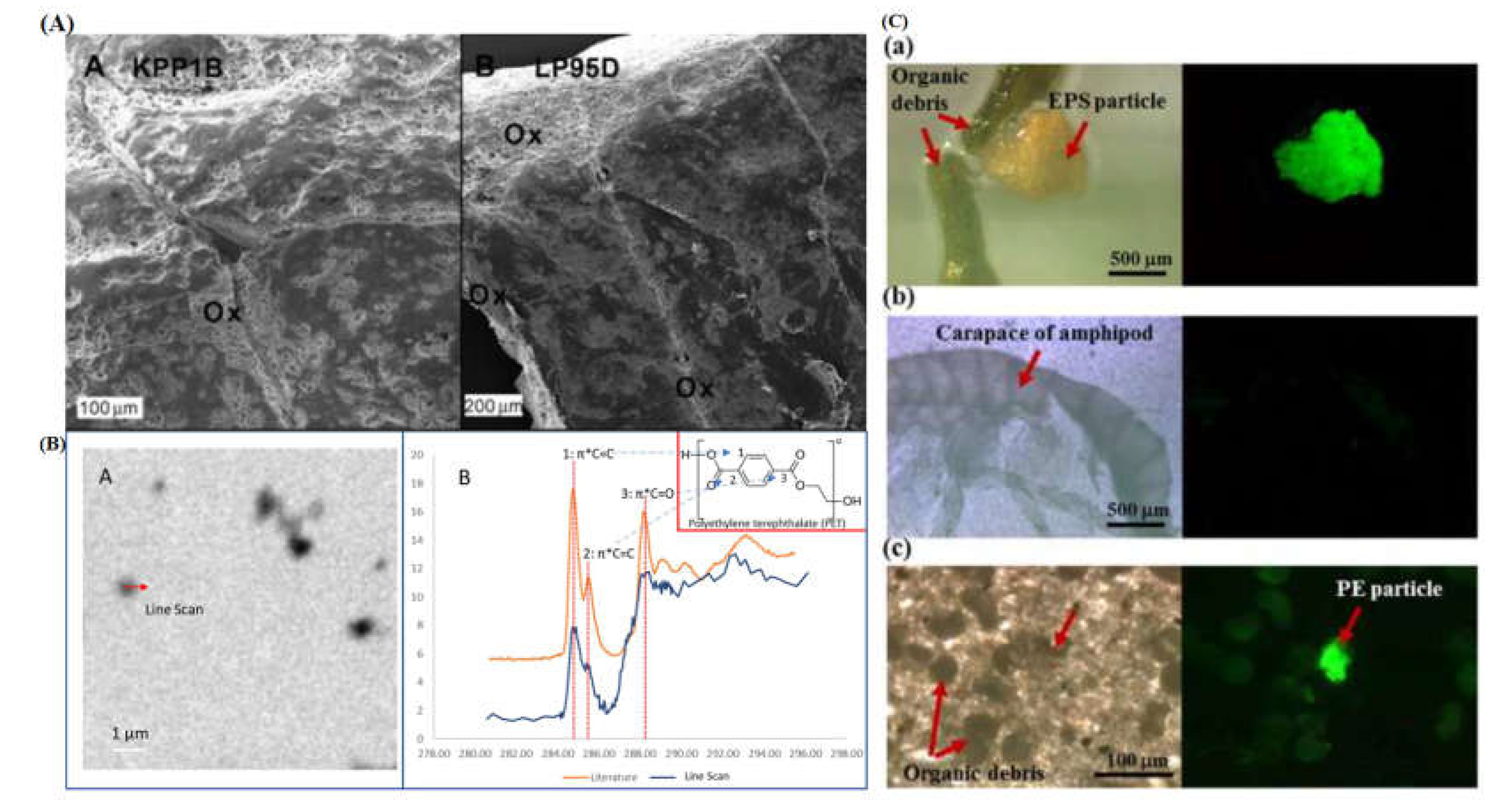

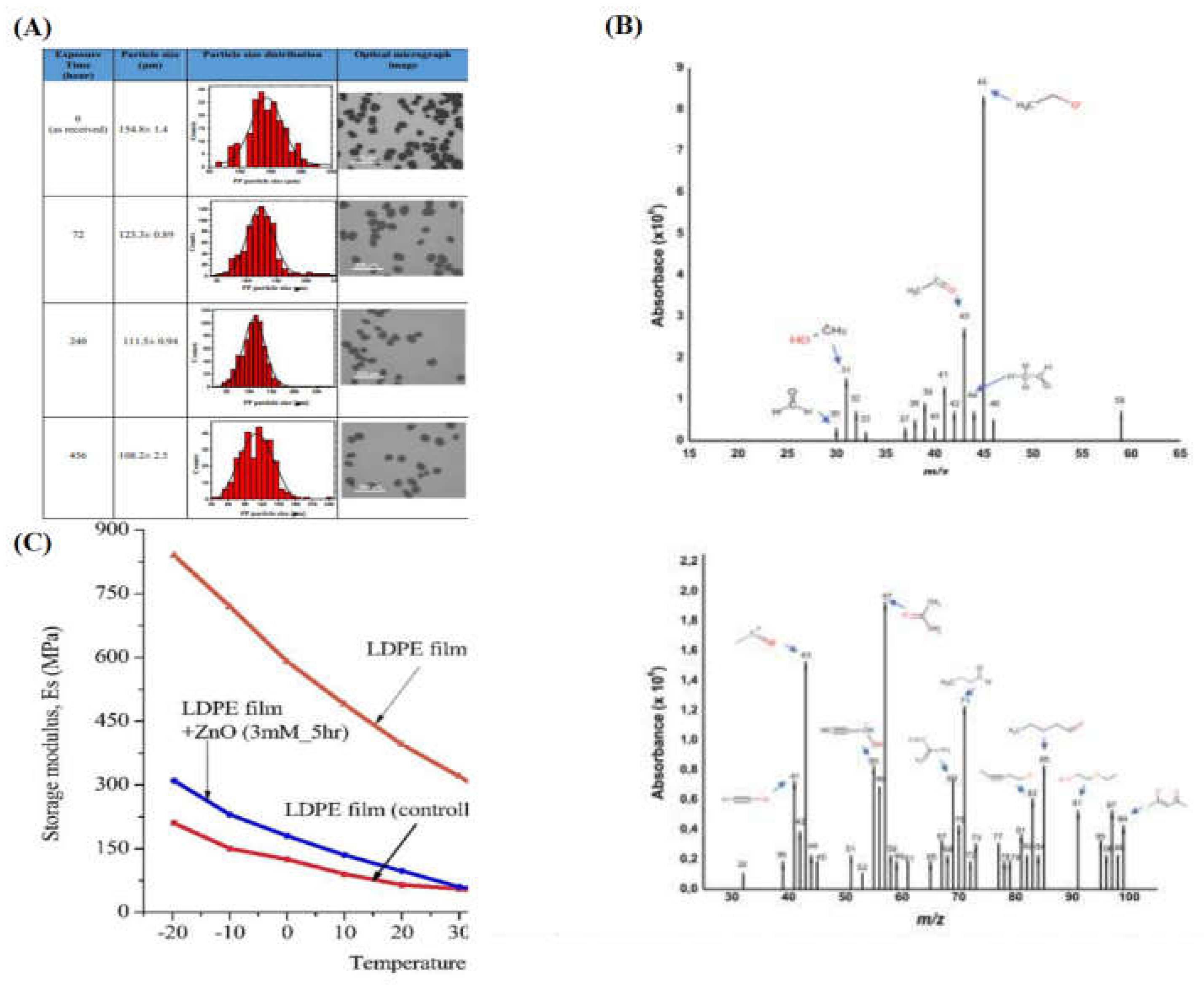

2.7. Morphological Characterization

2.8. Isolation and Sample Pretreatment

2.9. Characterization Overview (Conclusion)

3. Existing and Theoretical Modes of Remediation

3.1. Existing Modes of Remediation

| Method | Category | Particle Size Regime | Sample Preparation | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTIR | Identification | MPLs | Dry | Adequate resolution and well reported method. Identifies polymers, additives, and adsorbents. Spectral libraries available | Sensitive to confounding chemical noise from additives/adsorbents. |

| Raman | Identification/Quantification | MPLs/NPLs | Dry (Wet: Raman Tweezers) | Higher spatial resolution, well reported method. Identifies polymers, additives, and adsorbents. Spectral libraries available | Sensitive to confounding chemical noise from additives/adsorbents. Fluorescence from material can be an issue. |

| H-NMR | Identification | MPLs | Wet | Possible confirmatory technique for structural analysis. Identifies structure of oxidized species. | Extensive sample preparation. |

| Pyrolysis | Identification/Quantification | MPLs/NPLs | Wet | LoD is low for concentration and size of particles. Great application for biological samples. | Sample destruction. Extensive sample preparation. |

| FFF-MALS | Identification/Quantification | MPLs/NPLs | Wet | Various size regimes can be studied based on applied mode (field/pore shape nature and size. | Not well studied. Largely proprietary. |

| Counting/Weighing | Quantification | MPLs (counting)/MPLs and NPLs weighing | Dry | Mainly benefits larger MPLs and mesoplastics. | NPL and lower MPL regime more challenging to weigh/count. |

| Method | Category | Particle Size Regime | Sample Preparation | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

DLS |

Quantification |

MPLs/NPLs |

Wet (colloid) |

Gives average diameter in addition to concentration of MPLs and NPLs. |

Engineered MPL and NPL colloids with adequate serial dilutions for calibration needed. Samples tested must be within range of calibration. |

| Turbidometry |

Quantification | MPLs | Wet/Dry | Facile: Measures opacity. | Turbidometry not as common as DLS in literature for nanoparticles. |

| AFM/SEM/TEM | Identification | MPLs/NPLs | Dry | Elucidates morphological nature to particles. | AFM not well studied for MPLs |

|

STXM |

Identification |

MPLs/NPLs/Microfibrils |

Dry |

Offers spatial determination of material type present in a given sample | Extensive preparation for particle type and size. Grid needed for centrifugal capture. |

|

NTA |

Quantification |

MPLs/NPLs (by particle conc.) |

Wet |

Fairly facile and quick method for particle concentration determination. |

Limited to specific ranges of particle concentrations. |

|

TGA |

Identification |

MPLs (heterogeneous sample may contain NPLs/Mesoplastic etc.) |

Dry |

Concentration of PE/PP determined in heterogeneous sample | No clear determination of MPL and NPL presence (general plastic concentration). |

| DSC | Identification | MPLs (specific extraction for higher regime MPLs) | Dry | Heating steps improves SNR | Sample not heterogenous. |

3.2. Theoretical Modes of Remediation via Nanotechnology

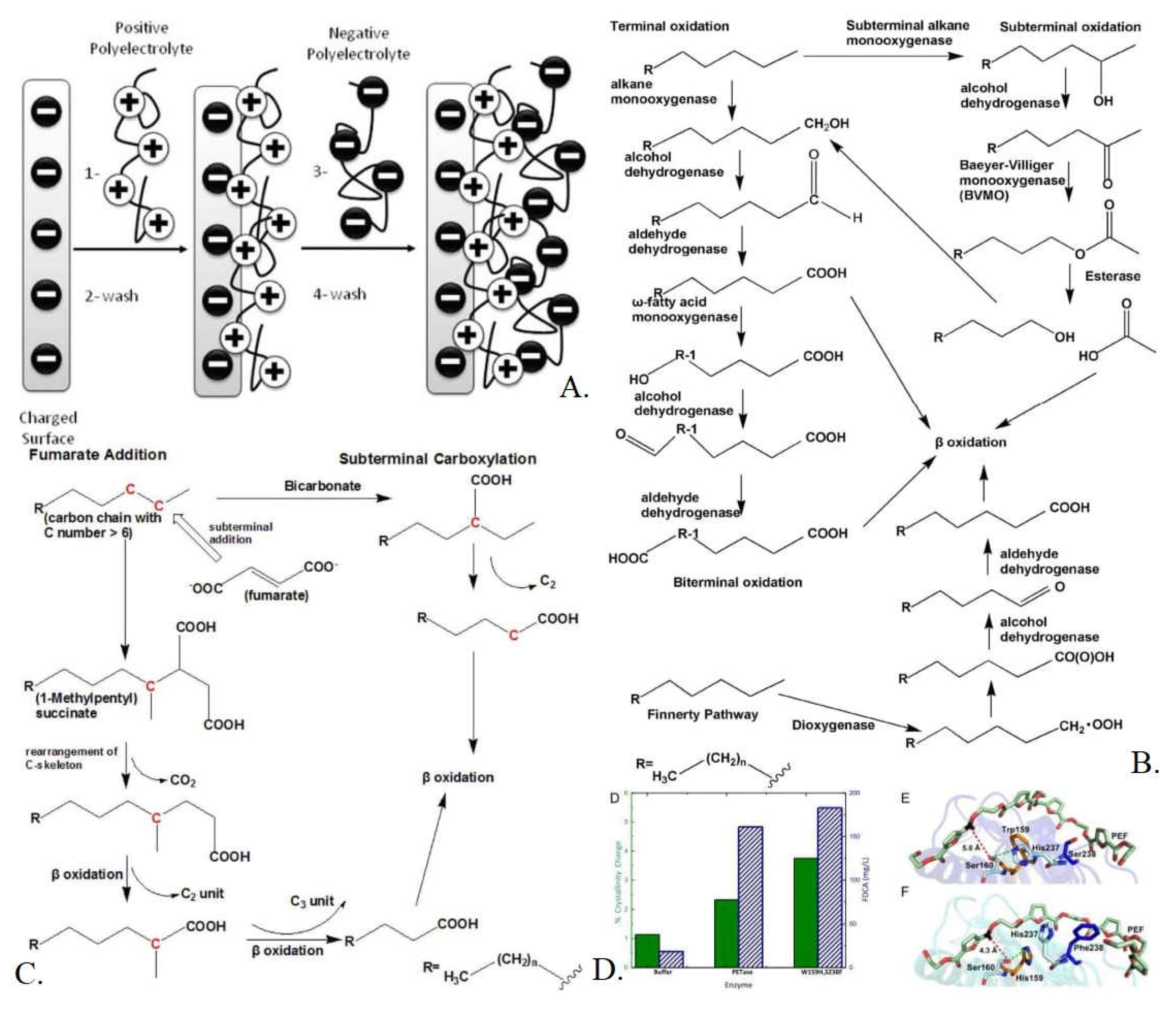

3.2.1. Layer-by-layer (LBL) Nanoparticle Remediator

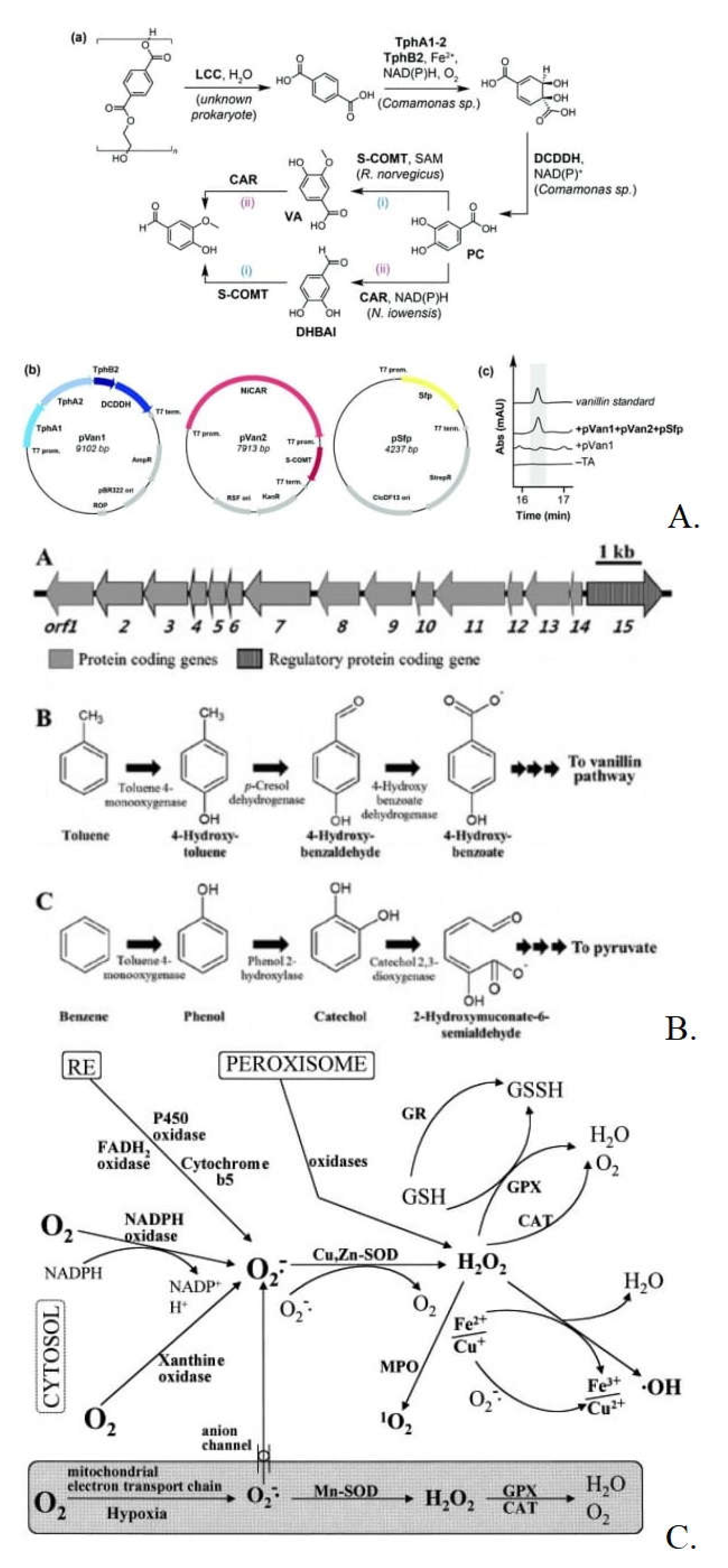

3.2.2. Enzyme Selection

3.2.3. Processing Implementation in Wastewater Management

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. Bergmann, L. Gutow, and M. Klages, “Marine anthropogenic litter,” Mar. Anthropog. Litter, pp. 1–447, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. Gallo et al., “Marine litter plastics and microplastics and their toxic chemicals components: The need for urgent preventive measures,” Environ. Sci. Eur., vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 1–14, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Chamas et al., “Degradation Rates of Plastics in the Environment,” ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng., vol. 8, no. 9, pp. 3494–3511, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Uheida, H. G. Mejía, M. Abdel-Rehim, W. Hamd, and J. Dutta, “Visible light photocatalytic degradation of polypropylene microplastics in a continuous water flow system,” J. Hazard. Mater., vol. 406, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. L. Corcoran, M. C. Biesinger, and M. Grifi, “Plastics and beaches: A degrading relationship,” Mar. Pollut. Bull., vol. 58, no. 1, pp. 80–84, 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Mecozzi, M. Pietroletti, and Y. B. Monakhova, “FTIR spectroscopy supported by statistical techniques for the structural characterization of plastic debris in the marine environment: Application to monitoring studies,” Mar. Pollut. Bull., vol. 106, no. 1–2, pp. 155–161, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- F. Lachmann et al., “Marine Plastic Litter on Small Island Developing States (SIDS),” no. May, pp. 1–76, 2017. [CrossRef]

- ter Halle and J. F. Ghiglione, “Nanoplastics: A Complex, Polluting Terra Incognita,” Environ. Sci. Technol., vol. 55, no. 21, pp. 14466–14469, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Ren et al., “Weathering of microplastics and their enhancement on the retention of cadmium in coastal soil saturated with seawater,” J. Hazard. Mater., vol. 440, p. 129850, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Alharbi, A. A. Basheer, R. A. Khattab, and I. Ali, “Health and environmental effects of persistent organic pollutants,” J. Mol. Liq., vol. 263, pp. 442–453, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Zhao et al., “Adsorption of Different Pollutants by Using Microplastic with Different Influencing Factors and Mechanisms in Wastewater: A Review,” Nanomaterials, vol. 12, no. 13, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Atugoda et al., “Interactions between microplastics, pharmaceuticals and personal care products: Implications for vector transport,” Environ. Int., vol. 149, p. 106367, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Ye et al., “Neurotoxicity of microplastics: A CiteSpace-based review and emerging trends study,” Environ. Monit. Assess., vol. 195, no. 8, p. 960, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Agboola and N. U. Benson, “Physisorption and Chemisorption Mechanisms Influencing Micro (Nano) Plastics-Organic Chemical Contaminants Interactions: A Review,” Front. Environ. Sci., vol. 9, p. 167, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- Koelmans et al., “Nanoplastics in the Aquatic Environment. Critical Review,” Mar. Anthropog. Litter, pp. 325–340, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Shao, Z. Han, N. Krasteva, and D. Wang, “Identification of signaling cascade in the insulin signaling pathway in response to nanopolystyrene particles,” Nanotoxicology, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 174–188, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. G. N. Thushari and J. D. M. Senevirathna, “Plastic pollution in the marine environment,” Heliyon, vol. 6, no. 8, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Debruyn and F. A. P. C. Gobas, “A bioenergetic biomagnification model for the animal kingdom,” Environ. Sci. Technol., vol. 40, no. 5, pp. 1581–1587, Mar. 2006. [CrossRef]

- T. S. Galloway, “Micro- and nano-plastics and human health,” Mar. Anthropog. Litter, pp. 343–366, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Leslie, M. J. M. van Velzen, S. H. Brandsma, A. D. Vethaak, J. J. Garcia-Vallejo, and M. H. Lamoree, “Discovery and quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood,” Environ. Int., p. 107199, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Marfella et al., “Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Atheromas and Cardiovascular Events,” N. Engl. J. Med., vol. 390, no. 10, pp. 900–910, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Asamoah, E. Uurasjärvi, J. Räty, A. Koistinen, M. Roussey, and K. E. Peiponen, “Towards the Development of Portable and In Situ Optical Devices for Detection of Micro-and Nanoplastics in Water: A Review on the Current Status,” Polymers (Basel)., vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 1–30, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Cai et al., “Characteristic of microplastics in the atmospheric fallout from Dongguan city, China: Preliminary research and first evidence,” Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., vol. 24, no. 32, pp. 24928–24935, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Dris, J. Gasperi, M. Saad, C. Mirande, and B. Tassin, “Synthetic fibers in atmospheric fallout: A source of microplastics in the environment?,” Mar. Pollut. Bull., vol. 104, no. 1–2, pp. 290–293, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Sandt, J. Waeytens, A. Deniset-Besseau, C. Nielsen-Leroux, and A. Réjasse, “Use and misuse of FTIR spectroscopy for studying the bio-oxidation of plastics,” Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc., vol. 258, p. 119841, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Pik Leung; Forster, Rodney; McCumskay, Rick; Rogerson, Mike; Waller, “Handheld FT-IR Spectroscopy for the Triage of Micro- and Meso-Sized Plastics in the Marine Environment Incorporating an Accelerated Weathering Study and an Aging Estimation,” Spectroscopy. Accessed: Mar. 01, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.spectroscopyonline.com/view/handheld-ft-ir-spectroscopy-triage-micro-and-meso-sized-plastics-marine-environment-incorporating-ac.

- V. Nava, M. L. Frezzotti, and B. Leoni, “Raman Spectroscopy for the Analysis of Microplastics in Aquatic Systems,” Appl. Spectrosc., vol. 75, no. 11, pp. 1341–1357, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- “PublicSpectra | Raman Spectral Database.” Accessed: May 04, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://publicspectra.com/.

- P. J. Clunies-Ross, G. P. S. Smith, K. C. Gordon, and S. Gaw, “Synthetic shorelines in New Zealand? Quantification and characterisation of microplastic pollution on Canterbury’s coastlines,” New Zeal. J. Mar. Freshw. Res., vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 317–325, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Gillibert et al., “Raman tweezers for small microplastics and nanoplastics identification in seawater,” Environ. Sci. Technol., vol. 53, no. 15, pp. 9003–9013, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. R. M. Ramsperger et al., “Environmental exposure enhances the internalization of microplastic particles into cells,” Sci. Adv., vol. 6, no. 50, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Dong, Q. Zhang, X. Xing, W. Chen, Z. She, and Z. Luo, “Raman spectra and surface changes of microplastics weathered under natural environments,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 739, p. 139990, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- “Portable Raman Microscopy for Identification of Microplastics.” Accessed: Mar. 04, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.azom.com/article.aspx?ArticleID=19941.

- “Analytical Chemistry – A Guide to Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) – Compound Interest.” Accessed: Mar. 05, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.compoundchem.com/2015/02/24/proton-nmr/.

- N. Peez, M. C. Janiska, and W. Imhof, “The first application of quantitative 1H NMR spectroscopy as a simple and fast method of identification and quantification of microplastic particles (PE, PET, and PS),” Anal. Bioanal. Chem., vol. 411, no. 4, pp. 823–833, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Corti et al., “Thorough Multianalytical Characterization and Quantification of Micro- and Nanoplastics from Bracciano Lake’s Sediments,” Sustain. 2020, Vol. 12, Page 878, vol. 12, no. 3, p. 878, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Fischer and B. M. Scholz-Böttcher, “Simultaneous Trace Identification and Quantification of Common Types of Microplastics in Environmental Samples by Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry,” Environ. Sci. Technol., vol. 51, no. 9, pp. 5052–5060, May 2017. [CrossRef]

- Li et al., “Quantification of Nanoplastic Uptake in Cucumber Plants by Pyrolysis Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry,” Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., vol. 8, no. 8, pp. 633–638, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Jiménez-Lamana, L. Marigliano, J. Allouche, B. Grassl, J. Szpunar, and S. Reynaud, “A Novel Strategy for the Detection and Quantification of Nanoplastics by Single Particle Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS),” Anal. Chem., vol. 92, no. 17, pp. 11664–11672, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bühler and W. Simon, “Curie Point Pyrolysis Gas Chromatography,” J. Chromatogr. Sci., vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 323–329, Jun. 1970. [CrossRef]

- P. Arenas-Guerrero et al., “Determination of the size distribution of non-spherical nanoparticles by electric birefringence-based methods,” Sci. Rep., vol. 8, no. 1, p. 9502, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Hanif, N. Ibrahim, F. A. Dahalan, U. F. Md Ali, M. Hasan, and A. A. Jalil, “Microplastics and nanoplastics: Recent literature studies and patents on their removal from aqueous environment,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 810, p. 152115, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Misra et al., “Water Purification and Microplastics Removal Using Magnetic Polyoxometalate-Supported Ionic Liquid Phases (magPOM-SILPs),” Angew. Chemie Int. Ed., vol. 59, no. 4, pp. 1601–1605, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Batool and S. Valiyaveettil, “Surface functionalized cellulose fibers – A renewable adsorbent for removal of plastic nanoparticles from water,” J. Hazard. Mater., vol. 413, p. 125301, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Elkhatib, V. Oyanedel-Craver, and E. Carissimi, “Electrocoagulation applied for the removal of microplastics from wastewater treatment facilities,” Sep. Purif. Technol., vol. 276, p. 118877, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Aslan, S. Arslan, M. Eyvaz, S. Güçlü, E. Yüksel, and İ. Koyuncu, “A novel nanofiber microfiltration membrane: Fabrication and characterization of tubular electrospun nanofiber (TuEN) membrane,” J. Memb. Sci., vol. 520, pp. 616–629, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Rajala, O. Grönfors, M. Hesampour, and A. Mikola, “Removal of microplastics from secondary wastewater treatment plant effluent by coagulation/flocculation with iron, aluminum and polyamine-based chemicals,” Water Res., vol. 183, p. 116045, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Lambert and M. Wagner, “Characterisation of nanoplastics during the degradation of polystyrene,” Chemosphere, vol. 145, p. 265, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. K. R. Williams, J. R. Runyon, and A. A. Ashames, “Field-flow fractionation: Addressing the nano challenge,” Anal. Chem., vol. 83, no. 3, pp. 634–642, Feb. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Meier and G. Heinzmann, “Field-Flow Fractionation: A powerful technology for the separation and advanced characterization of proteins, antibodies, viruses, polymers and nano-/microparticles,” Researchgate.Net, no. September, pp. 1–34, 2017, [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319505751_Field-Flow_Fractionation_A_powerful_technology_for_the_separation_and_advanced_characterization_of_proteins_antibodies_viruses_polymers_and_nano-microparticles.

- M. Majewsky, H. Bitter, E. Eiche, and H. Horn, “Determination of microplastic polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) in environmental samples using thermal analysis (TGA-DSC),” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 568, pp. 507–511, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Bitter and S. Lackner, “Fast and easy quantification of semi-crystalline microplastics in exemplary environmental matrices by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC),” Chem. Eng. J., vol. 423, p. 129941, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. J. Wlasits, A. Stoellner, G. Lattner, K. Maggauer, and P. M. Winkler, “Size characterization and detection of aerosolized nanoplastics originating from evaporated thermoplastics,” Aerosol Sci. Technol., vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 176–185, 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Yang, J. Luo, and B. Nowack, “Characterization of Nanoplastics, Fibrils, and Microplastics Released during Washing and Abrasion of Polyester Textiles,” Environ. Sci. Technol., vol. 55, no. 23, pp. 15873–15881, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Mariano, S. Tacconi, M. Fidaleo, M. Rossi, and L. Dini, “Micro and Nanoplastics Identification: Classic Methods and Innovative Detection Techniques,” Front. Toxicol., vol. 0, p. 2, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. J. Shim, Y. K. Song, S. H. Hong, and M. Jang, “Identification and quantification of microplastics using Nile Red staining,” Mar. Pollut. Bull., vol. 113, no. 1–2, pp. 469–476, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. Maes, R. Jessop, N. Wellner, K. Haupt, and A. G. Mayes, “A rapid-screening approach to detect and quantify microplastics based on fluorescent tagging with Nile Red,” Sci. Rep., vol. 7, no. 1, p. 44501, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Araujo, M. M. Nolasco, A. M. P. Ribeiro, and P. J. A. Ribeiro-Claro, “Identification of microplastics using Raman spectroscopy: Latest developments and future prospects,” Water Res., vol. 142, pp. 426–440, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Valsesia et al., “Detection, counting and characterization of nanoplastics in marine bioindicators: A proof of principle study,” Microplastics Nanoplastics 2021 11, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–13, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Schwaferts, R. Niessner, M. Elsner, and N. P. Ivleva, “Methods for the analysis of submicrometer- and nanoplastic particles in the environment,” TrAC Trends Anal. Chem., vol. 112, pp. 52–65, Mar. 2019, Accessed: May 28, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0165993618304631.

- R. L. Coppock, M. Cole, P. K. Lindeque, A. M. Queirós, and T. S. Galloway, “A small-scale, portable method for extracting microplastics from marine sediments,” Environ. Pollut., vol. 230, pp. 829–837, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Díaz-Jaramillo, M. S. Islas, and M. Gonzalez, “Spatial distribution patterns and identification of microplastics on intertidal sediments from urban and semi-natural SW Atlantic estuaries,” Environ. Pollut., vol. 273, p. 116398, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Crichton, M. Noël, E. A. Gies, and P. S. Ross, “A novel, density-independent and FTIR-compatible approach for the rapid extraction of microplastics from aquatic sediments,” Anal. Methods, vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 1419–1428, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B. Schütze, W. M. Heinze, and Z. Steinmetz, “Sample Preparation Techniques for the Analysis of Microplastics in Soil—A Review,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 21, p. 9074, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. S. Tofa, K. L. Kunjali, S. Paul, and J. Dutta, “Visible light photocatalytic degradation of microplastic residues with zinc oxide nanorods,” Environ. Chem. Lett., vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 1341–1346, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Sakr and G. Borchard, “Encapsulation of enzymes in layer-by-layer (LbL) structures: Latest advances and applications,” Biomacromolecules, vol. 14, no. 7, pp. 2117–2135, Jul. 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. N. Talbert and J. M. Goddard, “Influence of nanoparticle diameter on conjugated enzyme activity,” Food Bioprod. Process., vol. 91, no. 4, pp. 693–699, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ji, G. Mao, Y. Wang, and M. Bartlam, “Structural insights into diversity and n-alkane biodegradation mechanisms of alkane hydroxylases,” Front. Microbiol., vol. 0, p. 58, 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. Wei and W. Zimmermann, “Microbial enzymes for the recycling of recalcitrant petroleum-based plastics: How far are we?,” Microb. Biotechnol., vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 1308–1322, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. Austin et al., “Characterization and engineering of a plastic-degrading aromatic polyesterase,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 115, no. 19, pp. E4350–E4357, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Sadler and S. Wallace, “Microbial synthesis of vanillin from waste poly(ethylene terephthalate),” Green Chem., vol. 23, no. 13, pp. 4665–4672, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Choi, H. M. Jin, S. H. Lee, R. K. Math, E. L. Madsen, and C. O. Jeon, “Comparative genomic analysis and benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and o-, m-, and p-xylene (BTEX) degradation pathways of Pseudoxanthomonas spadix BD-a59,” Appl. Environ. Microbiol., vol. 79, no. 2, pp. 663–671, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhe, H. Peng, D. Yang, G. Zhang, J. Zhang, and F. Ju, “Polyvinyl Chloride Biodegradation Fuels Survival of Invasive Insect Larva and Intestinal Degrading Strain of Klebsiella,” bioRxiv, p. 2021.10.03.462898, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Yasuhira et al., “6-Aminohexanoate oligomer hydrolases from the alkalophilic bacteria Agromyces sp. strain KY5R and Kocuria sp. strain KY2,” Appl. Environ. Microbiol., vol. 73, no. 21, pp. 7099–7102, Nov. 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Matés, C. Pérez-Gómez, and I. N. De Castro, “Antioxidant enzymes and human diseases,” Clin. Biochem., vol. 32, no. 8, pp. 595–603, Nov. 1999. [CrossRef]

- C. Yu, Z. Shao, B. Liu, Y. Zhang, and S. Wang, “Inhibition of 2-Amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo [4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP) Formation by Alkoxy Radical Scavenging of Flavonoids and Their Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship in a Model System,” J. Food Sci., vol. 81, no. 8, pp. C1908–C1913, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. Arregui et al., “Laccases: Structure, function, and potential application in water bioremediation,” Microb. Cell Factories 2019 181, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 1–33, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Oliveira et al., “Toward the Mechanistic Understanding of Enzymatic CO2 Reduction,” ACS Catal., vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 3844–3856, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Tchobanoglous and Metcalf and Eddy Incorporated, Wastewater Engineering: Treatment, Disposal, Reuse, Second. New York London McGraw-Hill, 1979.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).