Submitted:

08 August 2024

Posted:

09 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Section “Materials and Methods “explains the research methodology, detailing the green facade’s characteristics, the thermal simulation model employed, and the specific wall configurations under investigation.

- Section “Results and Discussions” presents the study’s findings, offering recommendations and highlighting the limitations encountered, thereby setting the stage for future research directions in this field.

2. Materials and Methods

- Walls made of insulated lightweight sandwich panels (W_LW) which represents the physical experimental mock-ups currently in place at the University Campus of Catania.

- Walls constructed with Poroton blocks (W_POR) which is a theoretical scenario explored solely within the simulation environment.

- Walls built from lava stone blocks (W_LST) which is another theoretical scenario investigated within the simulation environment.

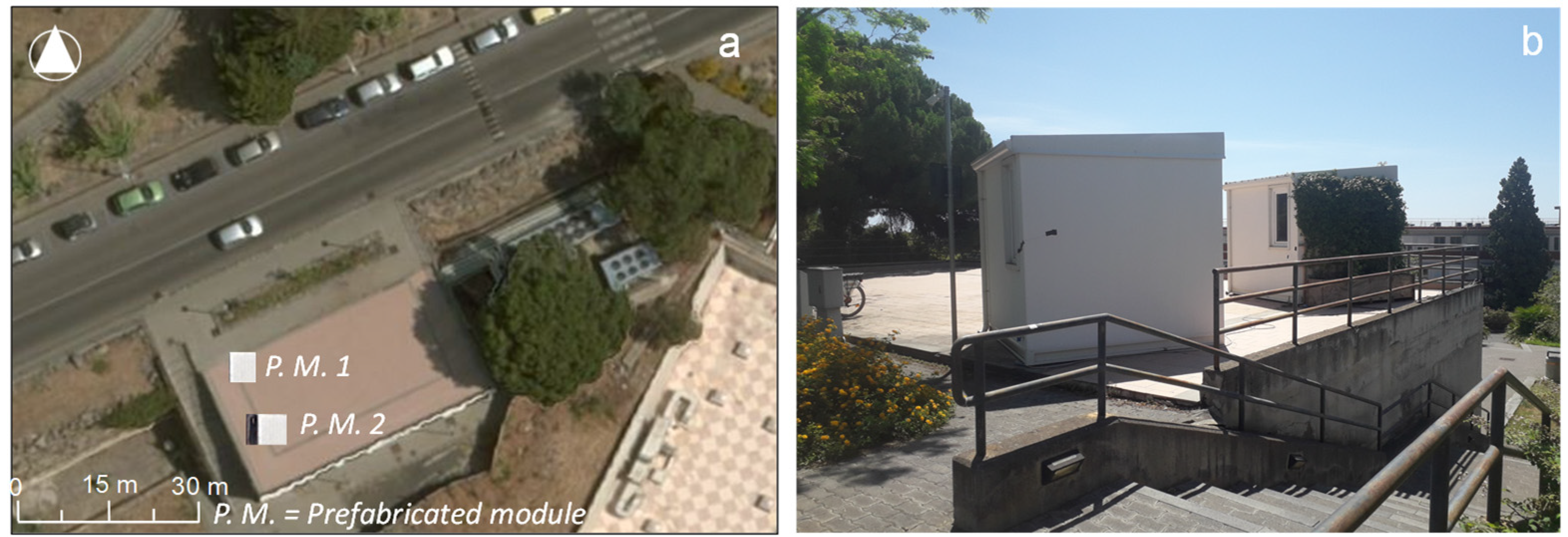

2.1. Case Study

2.2. Features of Thermal Simulation Model and Modeling Assumptions

- Shortwave Solar Radiation: Direct and diffuse solar radiation impacting the vegetation and wall surfaces.

- Longwave Radiation: Interactions between the wall, vegetation, ground, and sky.

- Radiant Exchanges: Between the vegetation and the wall surface.

- Heat Transfer Processes: Including convection and evapotranspiration.

| Parameter | Name | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf Area Index | LAI | m²/m² | 4.0 [15] |

| Leaf absorptance | αl | - | 0.54 [15] |

| Leaf stomatal conductance | gs | mol/m²s | 0.40 [16] |

| Leaf typical dimension | D | m | 0.11 [17] |

| Leaf radiation attenuation coefficient | k | - | 0.70 [18] |

| Leaf emissivity | εl | - | [15] |

- Unoccupied Interior Space: The interior space was treated as unoccupied, devoid of internal heat gains, and lacking any active heating or cooling systems.

- Adiabatic Surfaces: To isolate the thermal effects of the green facade, all external opaque surfaces of the prefabricated modules were modeled as adiabatic, except for the west-facing wall equipped with the VGS. This was achieved by setting the “boundary=identical” option for the external components in the TRNSYS model, ensuring equal air temperatures on both sides of the roof, floor, and walls, thus prventing them from contributing to thermal exchanges.

- Air Infiltration Rate: Standardized at a constant rate of 0.5 h⁻¹.

- Simulations were conducted over a typical summer week, from the 8th to the 14th of July, using a one-hour timestep. The initial conditions for the simulation, including the temperature and relative humidity of the indoor air, were based on measurements recorded at 1:00 a.m. on the 8th of July during the experimental campaign.

2.3. Investigated Wall Configurations

3. Results and Discussion

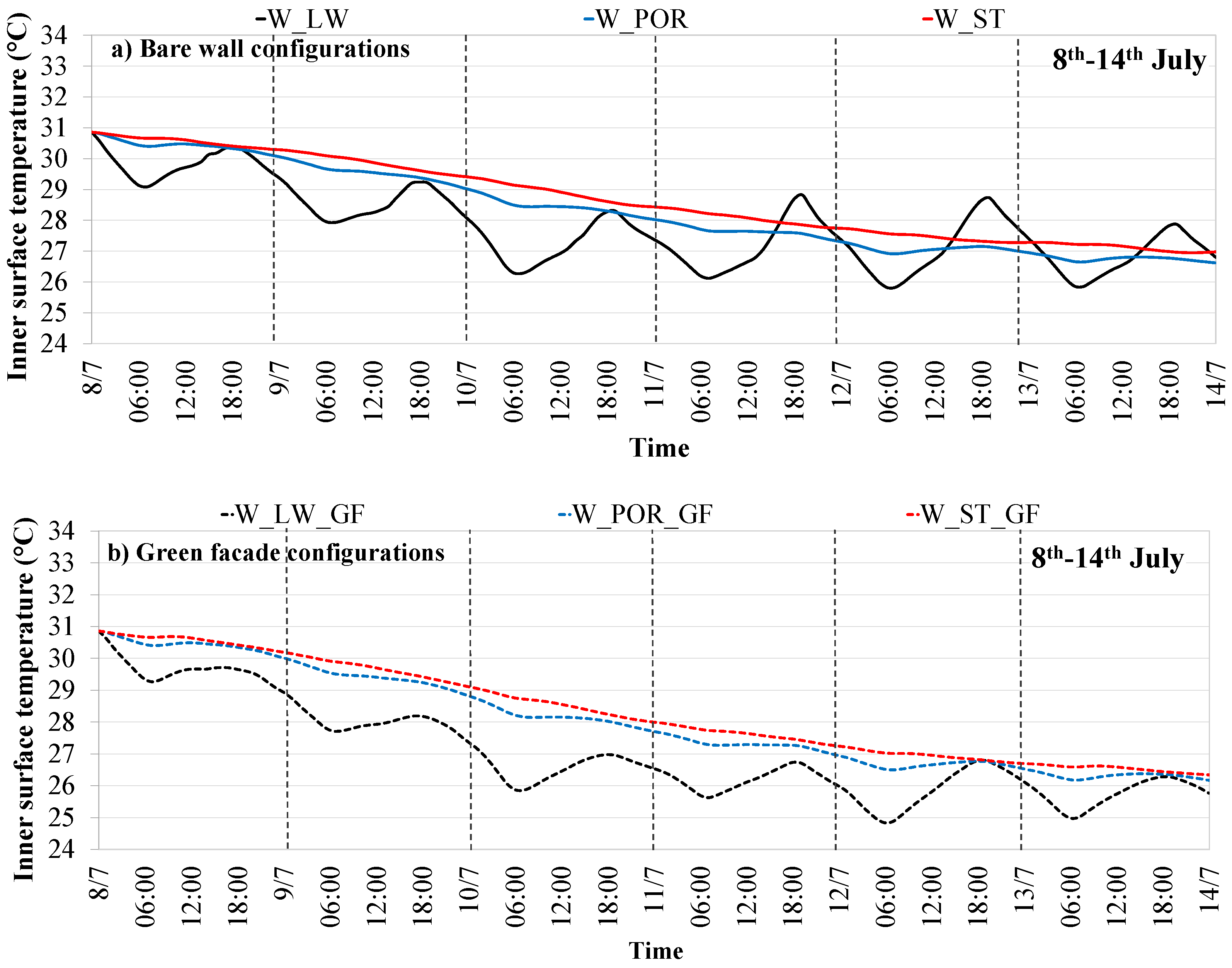

- Lightweight Wall (W_LW): The lightweight wall exhibits the highest fluctuations in Tis, with temperatures peaking during the day and dropping at night. From July 11th to 14th, Tis oscillates between a minimum of 25.9°C and a maximum of 28.9°C. The addition of the VGS (W_LW_GF) results in a marked reduction in peak Tis, moderating it to a narrower range between 25.0°C and 26.9°C, effectively reducing the peak temperature by up to 1.9°C. This indicates an enhanced buffering capacity against external temperature swings, showcasing the VGS’s significant impact on improving thermal comfort.

- Poroton Wall (W_POR): The Poroton wall shows moderate fluctuations in Tis, indicative of its higher thermal mass compared to the lightweight wall. The temperature fluctuations are significantly dampened, with Tis ranging between 26.0°C and 27.5°C. The incorporation of the VGS (W_POR_GF) further reduces the peak Tis by around 1.0°C, highlighting the combined effect of the wall’s inherent insulation and the green façade.

- Lava Stone Wall (W_ST): The lava stone wall presents the most stable Tis profile, with peak values marginally exceeding 27.0°C, reflecting the substantial thermal inertia of the material. The VGS (W_ST_GF) results in a slight reduction in peak Tis, demonstrating a modest improvement due to the already high thermal inertia of the lava stone.

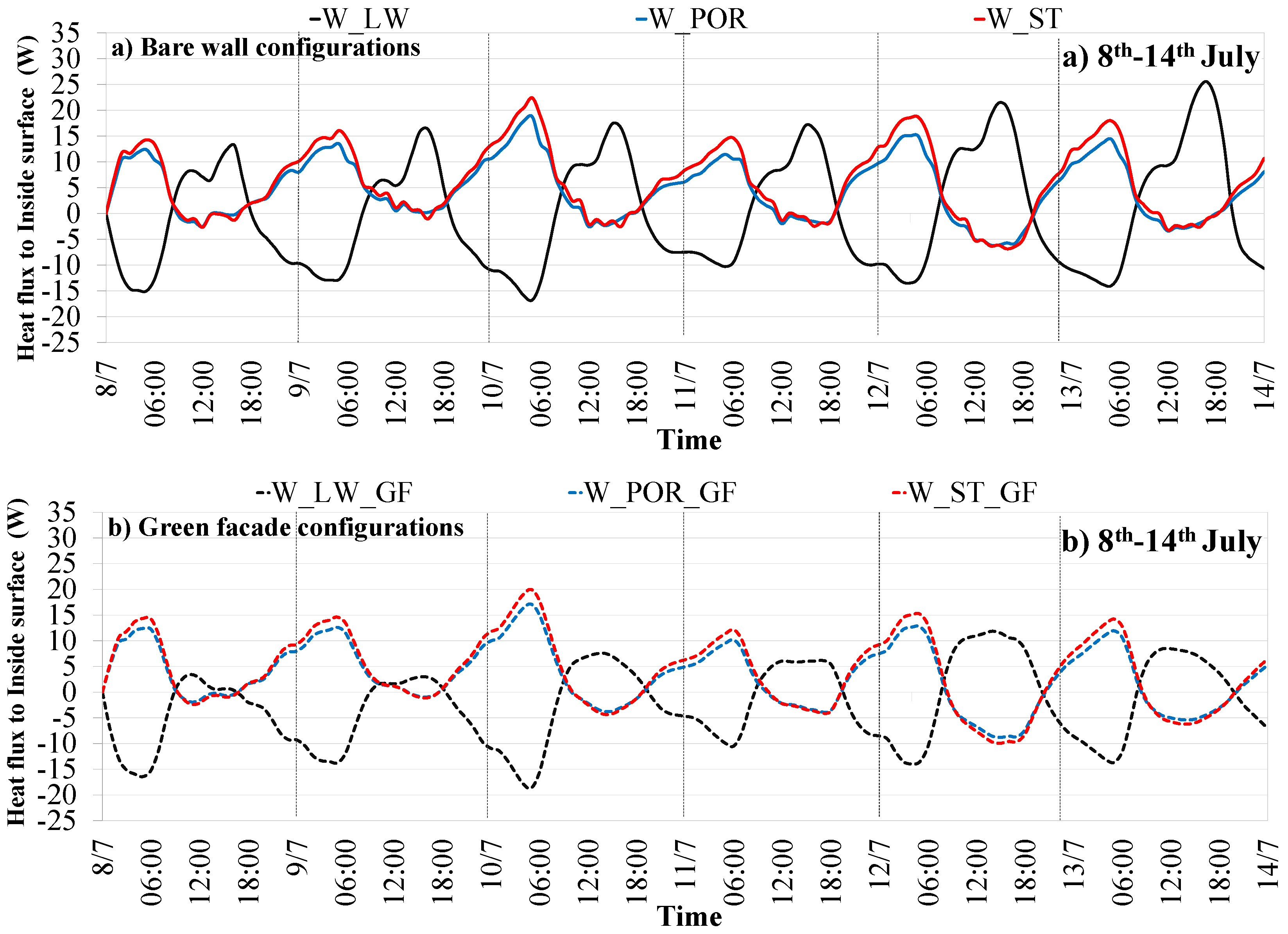

- Lightweight Wall (W_LW): The lightweight wall configuration shows significant daily variations in Qis, with the peak heat flux aligning with periods of maximum solar irradiation. This suggests a quick response to external temperature changes due to the wall’s low thermal mass. The VGS (W_LW_GF) significantly reduces the peak value and amplitude of Qis fluctuations, lowering the peak heat flux by approximately 15 W, demonstrating the VGS’s efficacy in shielding against solar radiation and enhancing thermal stability.

- Poroton Wall (W_POR): The Poroton wall exhibits a reduced amplitude in heat flux fluctuations compared to the lightweight wall, indicating a more gradual response to thermal inputs from the outdoors. The peak heat flux occurs about 10 hours later than in the lightweight wall, illustrating the delayed response associated with its higher thermal mass. The addition of the VGS (W_POR_GF) further dampens the heat flux, reducing the peak values by around 3 W.

- Lava Stone Wall (W_ST): The lava stone wall exhibits the smallest fluctuations in Qis, with a nearly flat profile and a substantially delayed peak heat flux by about 10 hours. This underscores the ability of lava stone blocks to absorb and slowly release heat, buffering the building’s interior from extreme outdoor temperatures. The VGS (W_ST_GF) adds a layer of thermal protection, further enhancing the wall’s ability to mitigate the effects of external thermal variations.

- Combining VGS with modern insulated materials like lightweight panels or Poroton blocks yields significant thermal comfort benefits, suggesting a synergistic approach to sustainable building design.

- The application of VGS on traditional heavy masonry walls, such as those made from lava stone, can provide measurable thermal improvements, making it a viable retrofitting strategy for enhancing the energy efficiency of historical buildings.

- The effectiveness of VGS in reducing heat ingress and stabilizing indoor temperatures makes it particularly suitable for Mediterranean climates, where high solar radiation and temperature fluctuations are common.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Mazzella, L.: Energy retrofit of historic and existing buildings. The legislative and regulatory point of view. Energy and Buildings 95, 23-31 (2015).

- Gagliano, A., Nocera, F., Patania, F., Moschella, A., Detommaso, M., Evola, G.: Synergic effects of thermal mass and natural ventilation on the thermal behaviour of traditional massive buildings. International Journal of Sustainable Energy, 2014.

- European Parliament, Directive 2010/31/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 May 2010 on the Energy Performance of Buildings (Recast), Official Journal of the European Union, 18 June 2010.

- Caponnetto, R., Cuomo, M., Detommaso, M., Giuffrida, G., Lo Presti, A., Nocera, F.: Performance assessment of Giant Reed-based building components. Sustainability 15, 2114 (2023).

- Assimakopoulos, M.N., De Masi, R.F., de Rossi, F., Papadaki, D., Ruggiero, S.: GreenWall Design Approach Towards Energy Performance and Indoor Comfort Improvement: A Case Study in Athens, Sustainability 12, 3772 (2020).

- Coma, J., Solé, C., Castell, A., Cabeza, L.F.: New green facades as passive systems for energy savings on buildings. Energy Procedia 57, 1851-1859 (2014).

- Vox, G., Blanco, L., Schettini, E.: Green façades to control wall surface temperature in buildings, Building and Environment 129, 154-166 (2018).

- Peng, Y., Huang, Z., Yang, Y., Wang, P., Hou, C.: Experimental Investigation on the Effect of Vertical Greening Facade on the Indoor Thermal Environment: A Case Study of Dujiangyan City, Sichuan Province. Earth and Environmental Science 330, 032068 (2019).

- Flores Larsen, S., Filippin, C., Lesino, G.: Modeling double skin green facades with traditional thermal simulation software. Solar Energy 121, 56-67 (2015).

- Kenai, M.A., Libessart, L., Lassue, S., Defer, D.: Impact of green walls occultation on energy balance: Development of a TRNSYS model on a brick masonry house. Journal of building Engineering 44, 102634 (2021).

- Transient System Simulation program (TRNSYS), University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA. Available online: https://www.trnsys.com/index.html#2 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Detommaso, M., Costanzo, V., Nocera, F., Evola, G.: Evaluation of the cooling potential of a vertical greenery system coupled to a building through an experimentally transient model. Building and Environment 244, 110769 (2023).

- Trnsys component Type 9644. Green façade - vertical foliage - VFC. CIM-mes Projekt Sp. z o.o. Warsaw, February 2022.

- UNI ISO 9869-1:2015. Isolamento termico - Elementi per l’edilizia - Misurazioni in situ della resistenza termica e della trasmittanza termica - Parte 1: Metodo del termoflussimetro.

- Convertino, F., Schettini, E., Blanco, I., Bibbiani, C., Vox, G.: Effect of Leaf Area Index on Green Facade Thermal Performance in Buildings. Sustainability 14, 2966 (2022).

- Susorova, I., Angulo, M., Bahrami, P., Stephens, B.: A model of vegetated exterior façades for evaluation of wall thermal performance. Building and Environment 67, 1-13 (2013).

- Campbell, G.S., Norman, J.M.: An introduction to environmental biophysics. Springer, New York, 1998.

- Levitt, J.: Responses of plants to environmental stresses: chilling, freezing, and high temperature stresses, Academic Press, San Diego,1980.

- Grabowiecki, K., Jaworski, A., Niewczas, T., Belleri, A.: Green solutions- climbing vegetation impact on building - energy balance element. Energy Procedia 111, 377 - 386 (2017).

- POROTON® P800 30X25X19. https://t2d.it/prodotti/poroton-p800-30x25x19-2/. Available online: https://t2d.it/prodotti/poroton-p800-30x25x19-2/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

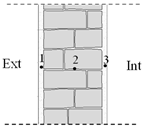

| No | Layer | s (m) | λ (W/m2K) | ρ (kg/m3) | Cp (J/kgK) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | OSB panel (Outer plaster) |

0.009 | 0.12 | 650 | 1700 |

| 2 | Polystirene | 0.065 | 0.04 | 15 | 1450 |

| 3 | OSB panel (Inner plaster) |

0.006 | 0.12 | 650 | 1700 |

| No | Layer | s (m) | λ (W/m2K) | ρ (kg/m3) | Cp (J/kgK) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lime and cement mortar (Outer plaster) | 0.03 | 0.90 | 1800 | 1000 |

| 2 | Hollow clay block-POROTON850 [20] | 0.30 | 0.18 | 850 | 1000 |

| 3 | Lime and cement mortar (Inner plaster) | 0.03 | 0.90 | 1800 | 1000 |

| No | Layer | s (m) | λ (W/m2K) | ρ (kg/m3) | Cp (J/kgK) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lime mortar (Outer plaster) | 0.03 | 0.90 | 1800 | 1000 |

| 2 | Lava stone block and lime mortar [2] | 0.30 | 1.70 | 2200 | 1000 |

| 3 | Lime and gypsum mortar (Inner plaster) | 0.03 | 0.70 | 1800 | 1000 |

| W_LW | W_POR | W_ST | |

|

|

|

|

| W_LW_GF | W_POR_GF | W_ST_GF | |

|

|

|

|

| U (W/m2K) | 0.52 | 0.52 | 1.85 |

| SM (kg/m2) | 13 | 255 | 1100 |

| s (m) | 0.08 | 0.36 | 0.56 |

| DF (-) | 0.99 | 0.13 | 0.07 |

| TL (h) | 1 | 15 | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).