Submitted:

08 August 2024

Posted:

09 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- —

- morphological form of POS related to its urban function

- —

- ownership and control over POS

- —

- social environment

- —

- natural environment

- —

- multi-faceted categorization.

1.1. Bunnik Municipality as the Object of a Field Study

- —

- Diverse histories of the country towns belonging to the commune

- —

- Varied landscapes (urbanized, rural, natural)

- —

- Diversity of settlement forms, ranging from the most frequent single-family housing estates to multifamily housing estates, and farms

- —

- Presence of public utility facilities, including service-commercial, educational, sports, and social functions, both of local and supra-local importance

- —

- Varied forms of greenery (e.g., urban green spaces, agricultural areas, waterfront and forested areas)

- —

- Diverse forms of mobility, including wide accessibility for pedestrians and cyclists to open areas within three zones of reach: central, local, and peripheral.

1.2. Gathering, and Recreation Places as a Public Space Consumed and Co-Created by the Local Community

2. Research Design and Methods

- It focuses on the exploration of existing local gathering and recreation places.

- It offers a division of observed places by capturing them as spatial-functional units

- Utilizes survey instruments (mainly analyses of physical traces, non-participatory observation, and analysis of hedonic quality of space) that allow the identification of a variety of relations in the spatial-functional arrangement of the studied places.

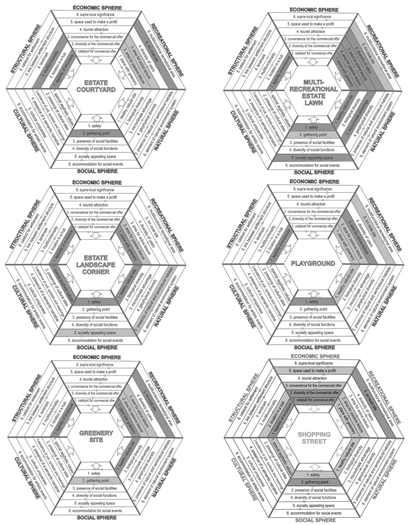

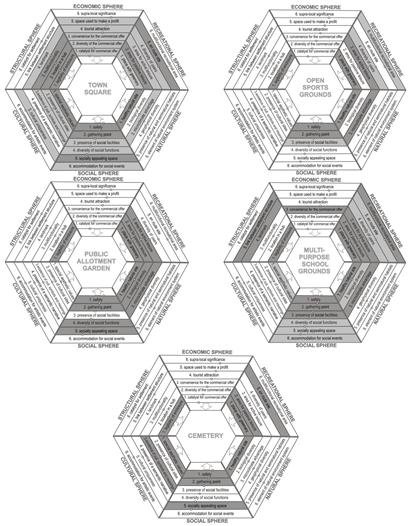

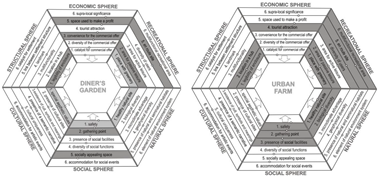

- The POS spheres method takes into account urban, natural, and social determinants of POS development and represents an interdisciplinary approach to the study of public space that captures the structural, economic, natural, recreational, social, and cultural aspects of POS.

- (a)

-

A preliminary study to analyze the urban background of the commune, including:

- —

- Indication of landmarks based on iconographic analysis of online sources (OpenStreetMap, n.d.)

- —

- Indication of the location of communication hubs for each of the villages of the Bunnik commune and the public buildings (educational, health, cultural and sacral centers, the local government office, shopping centers and supermarkets)

- —

- Analysis of the communication system with particular emphasis on the course of communication arteries (OpenStreetMap, n.d.)

- —

- Indication of the access zones for pedestrian traffic (Villanueva et al., 2015) for each of the villages of the Bunnik commune (central, local and peripheral zone)

- —

- Analysis of the landscape character based on analysis of photo documentary, cartographic and online resources (Google Maps, n.d.)

- (b)

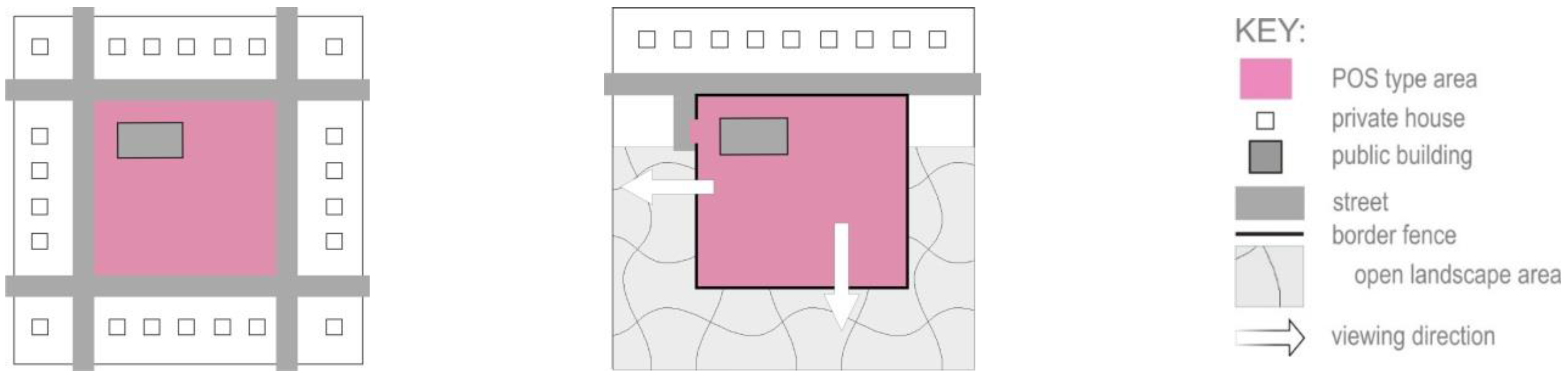

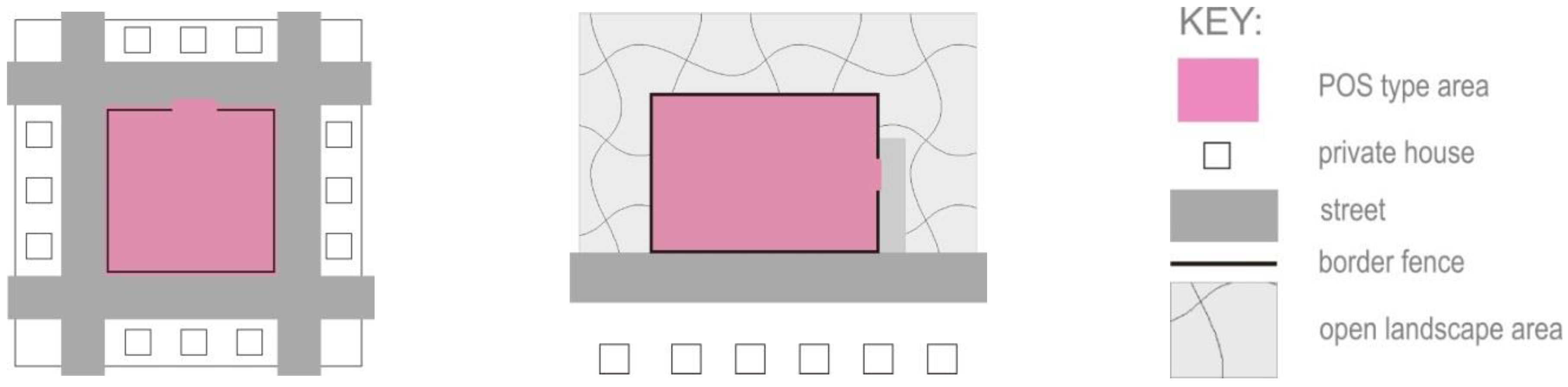

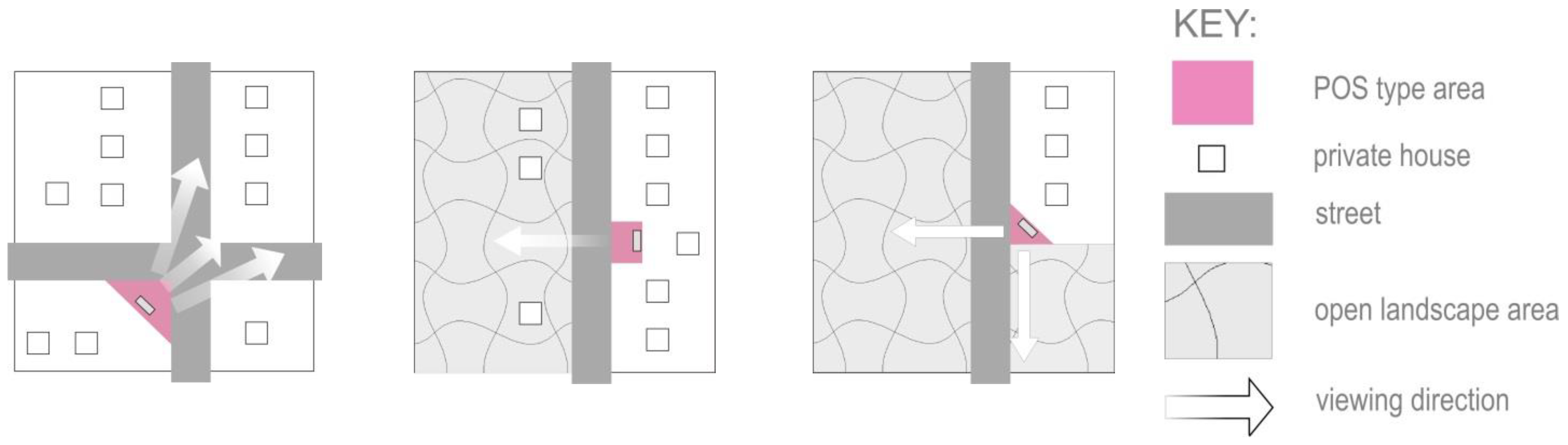

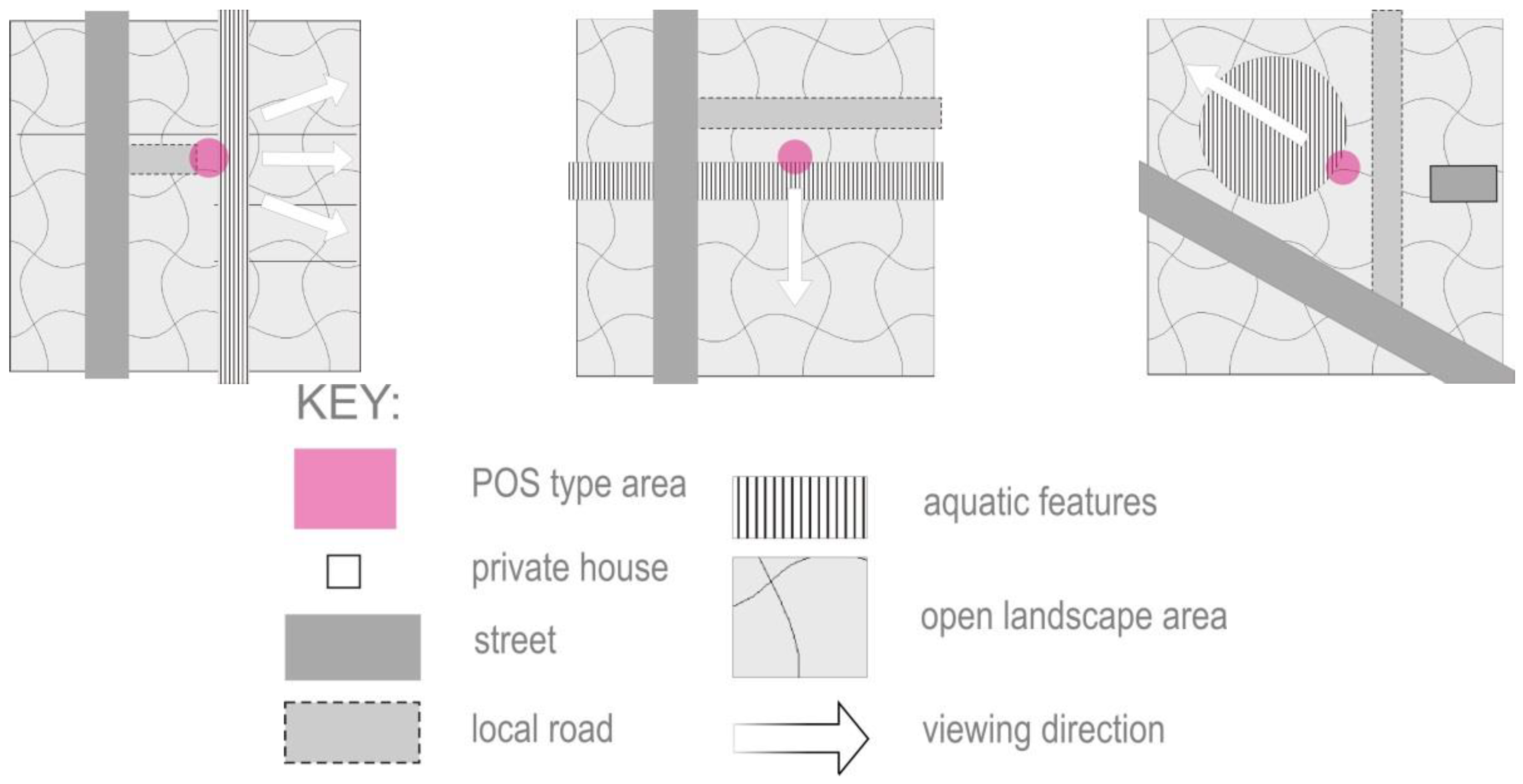

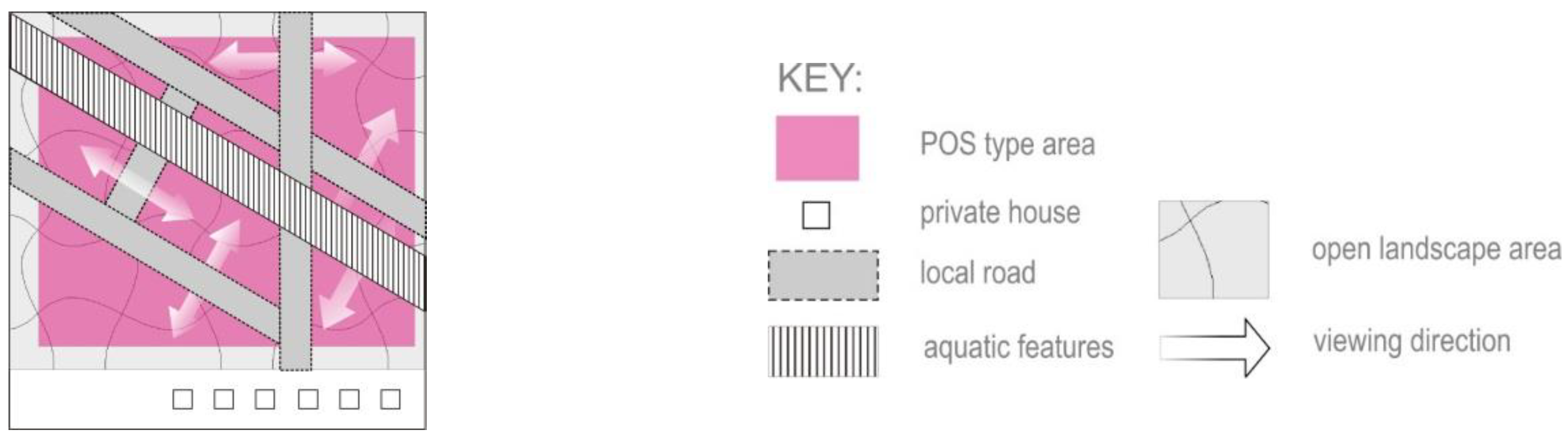

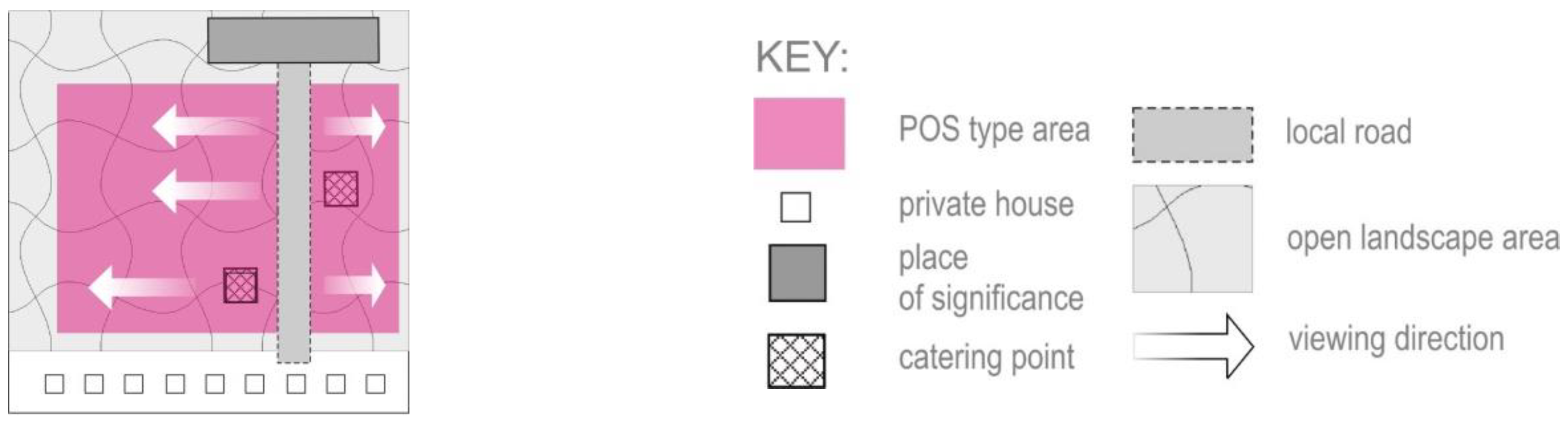

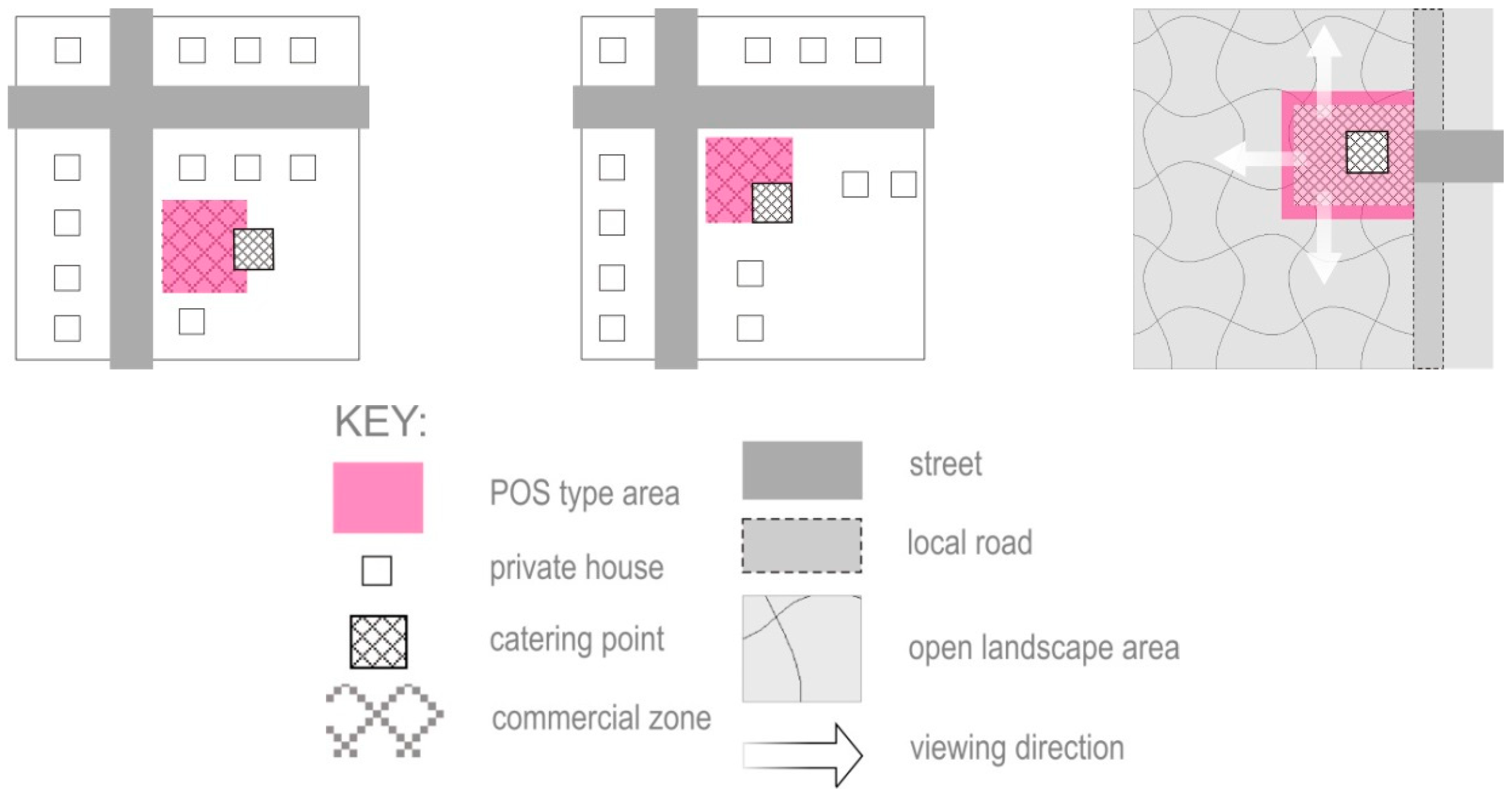

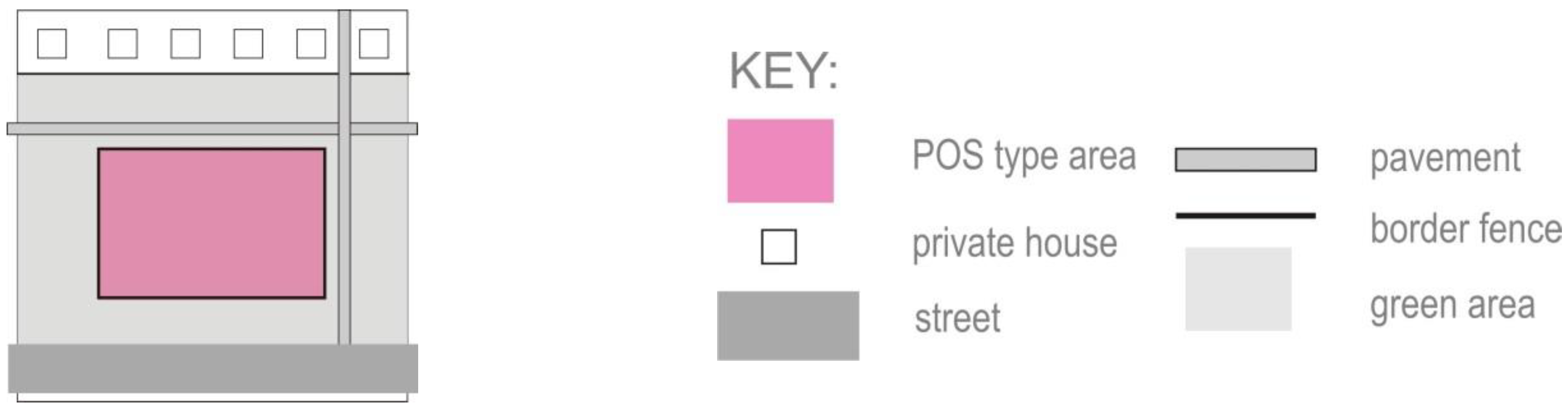

- Distinguishing the gathering and recreation places (so called: POS objects) located in the commune and characterizing them based on the criteria and principles described in the dataset repository (POS sphere diagrams were deposited for each of them)

- (c)

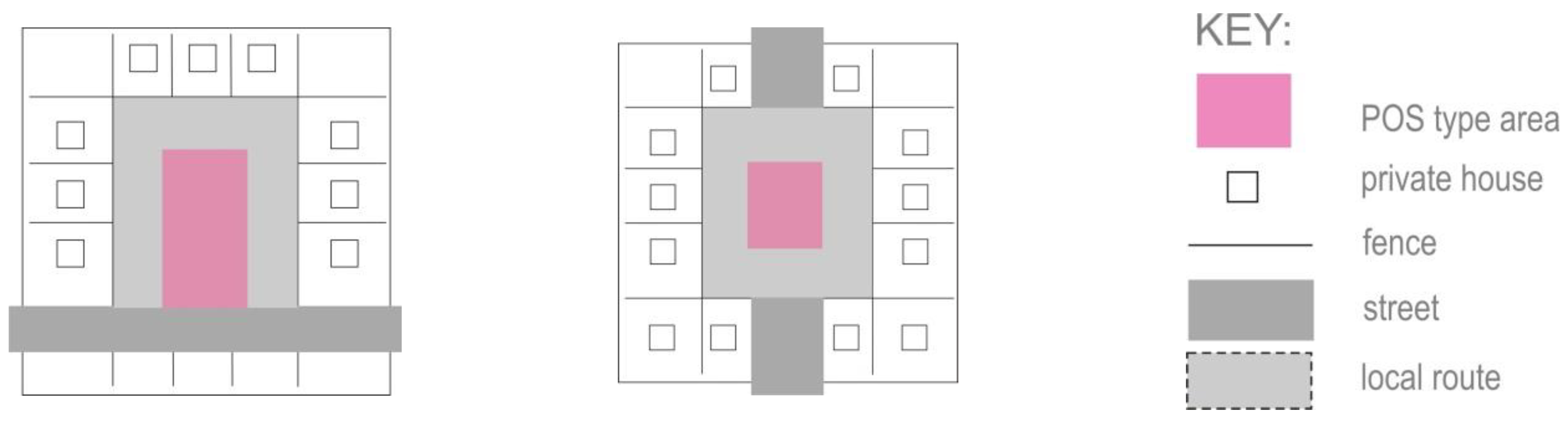

- Combining the identified POS objects into groups (so called: POS types).

- (d)

- Developing characteristics of POS types in tables (Appendix A) of the scope described in the dataset repository (including development of POS sphere diagrams)

- (e)

- Discussing the POS types obtained as a result of the research.

- (a)

- Analysis of POS types for top-down design and planning based on spatial-functional analysis of POS objects and land ownership.

- (b)

- Indicating forms of top-down design and planning

- (c)

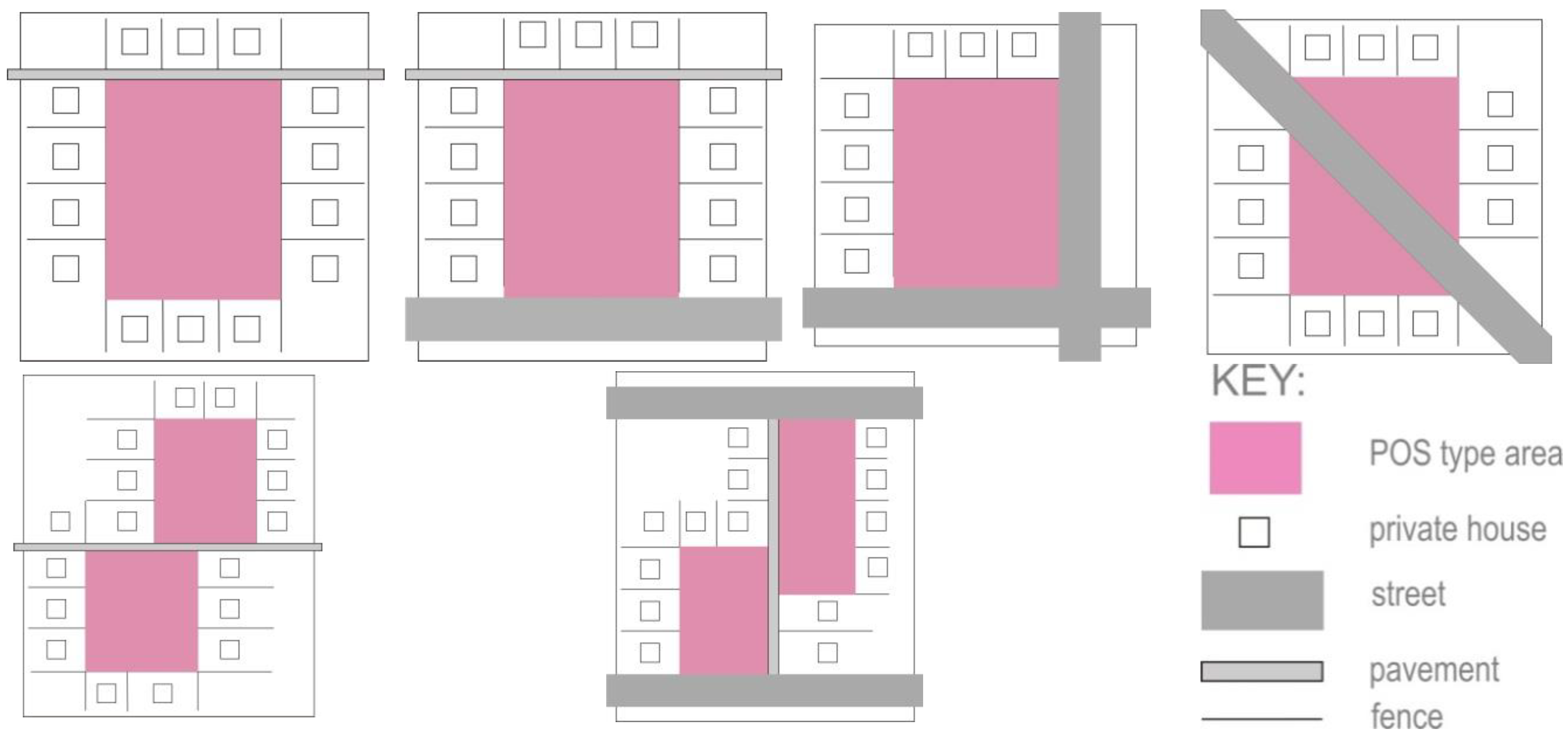

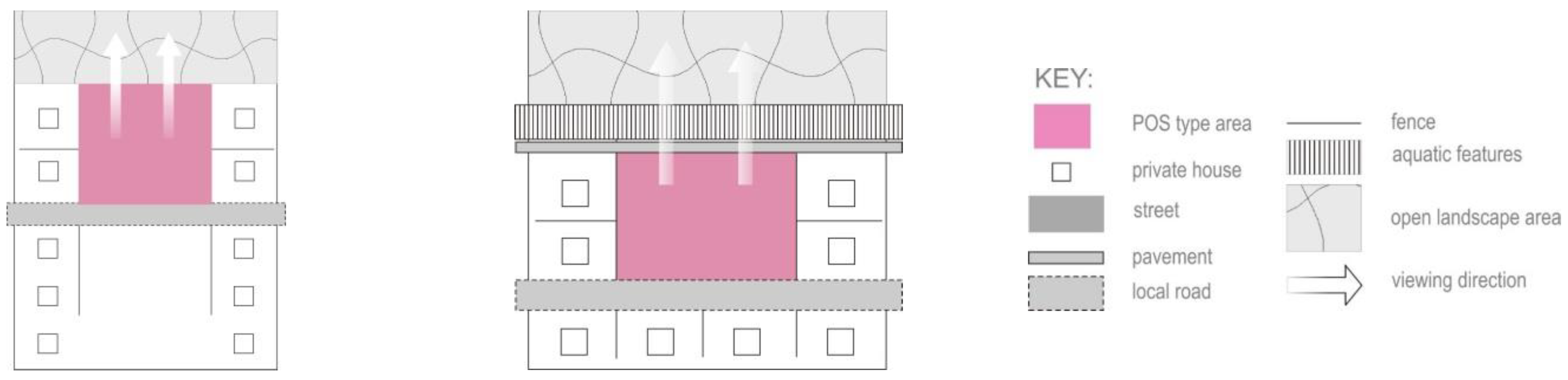

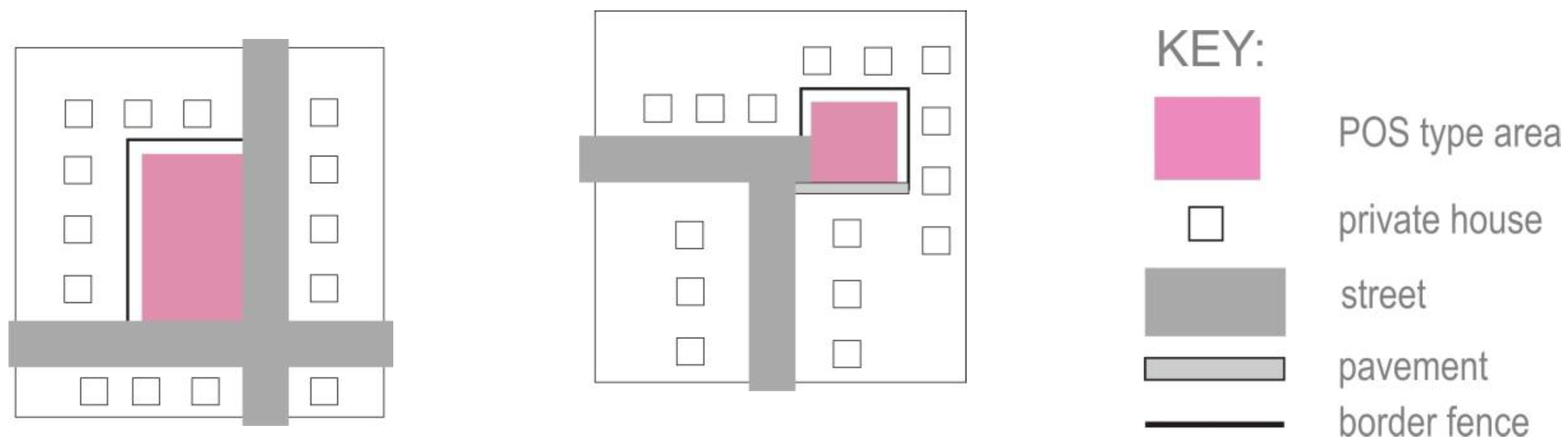

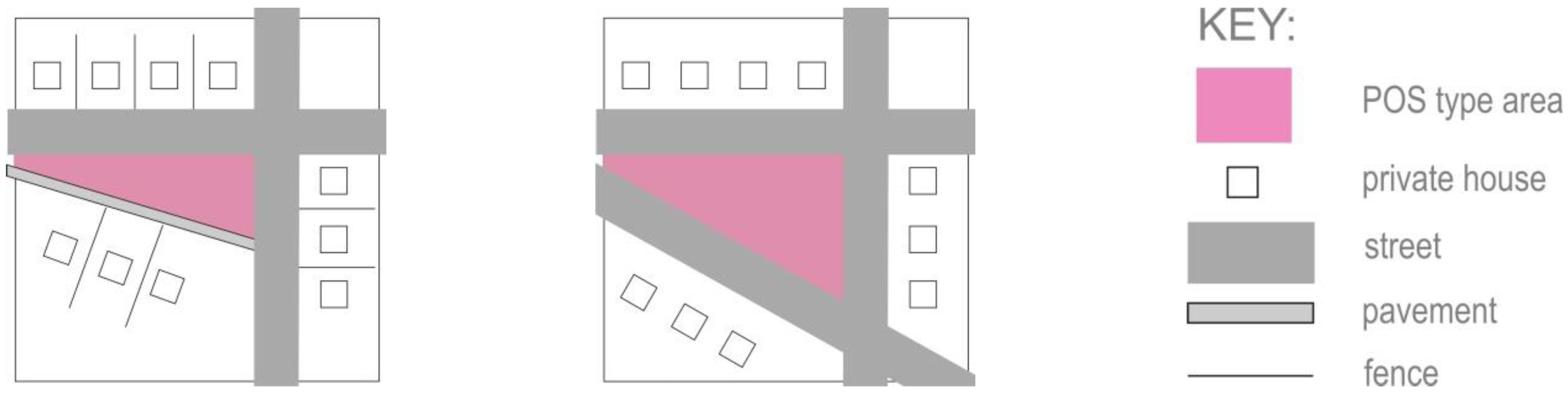

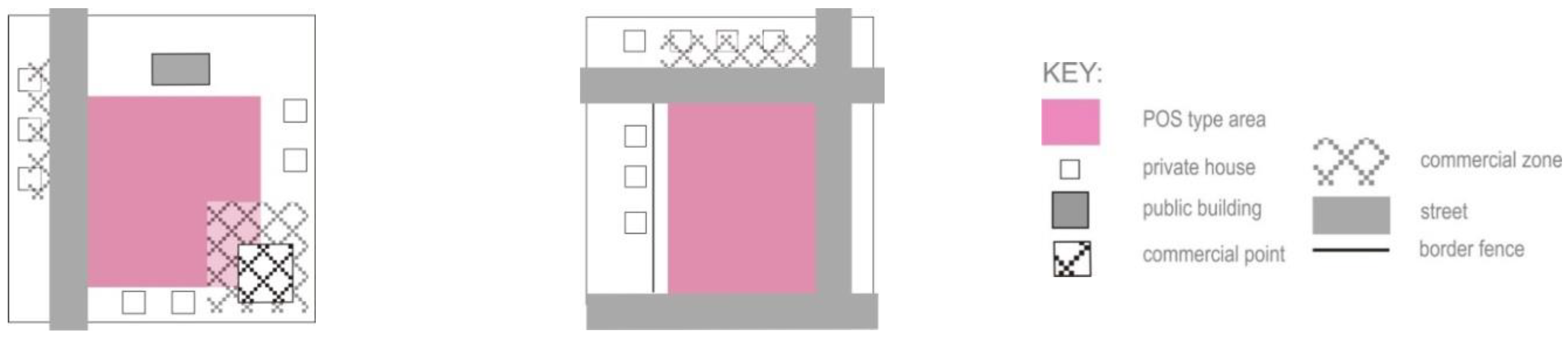

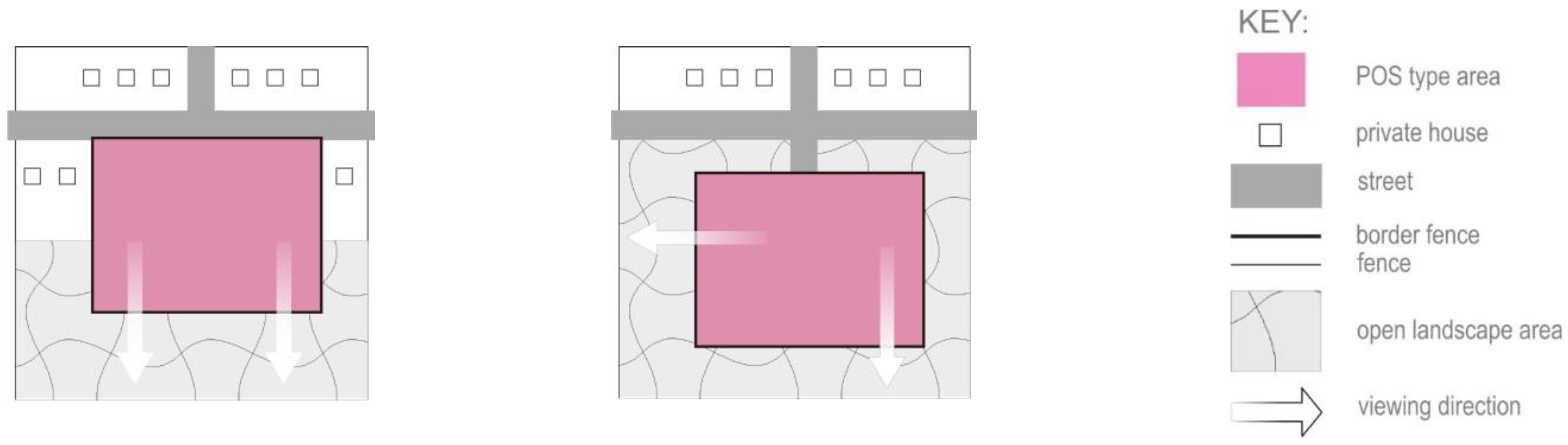

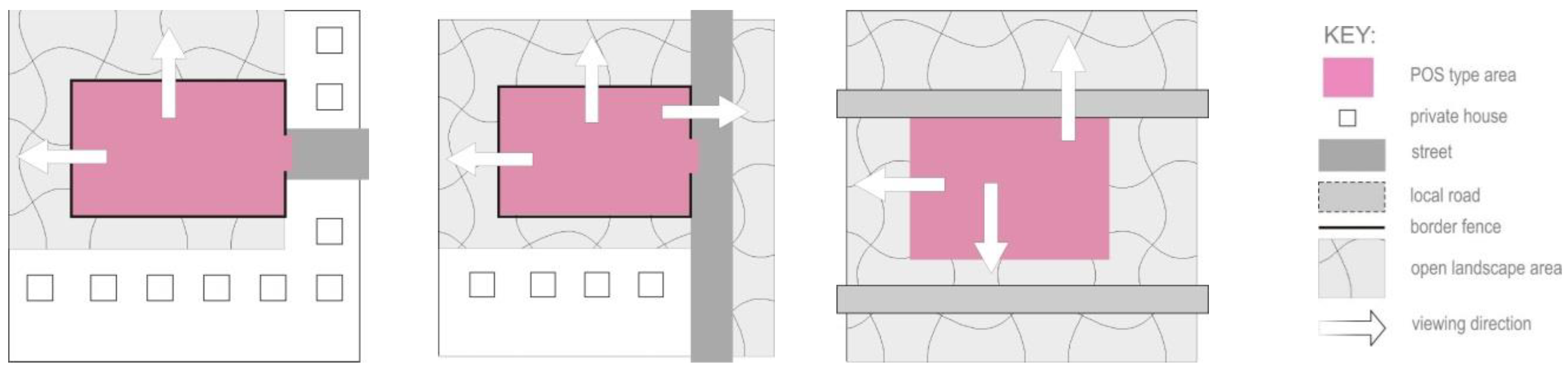

- Development of the resulting characteristics of POS types supplemented by the set of diagrams of POS spheres (Appendix B), photos of exemplary POS objects that represent a given type, as well as structural models that describe it (Appendix C).

- (d)

- Compiling a of POS types in terms of top-down design and planning. The presented types were ordered by taking into account the quantitative share of POS objects in each type.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Distinguishing of the POS Objects

3.3. Identification of the POS Types

3.4. Analysis of Top-Down Design and Planning Development

- —

- Estates with a recreational areas dedicated to the neighborhood community

- —

- Communal (extra-neighborhood) playgrounds

- —

- Greeneries by pedestrian routes

- —

- Social places in central zone

- —

- Multi-purpose recreational areas at schools, available to residents

- —

- Open sports grounds in every countryside town

- —

- Community allotment gardens in every countryside town

- —

- Communal facilities generating informal meetings

- —

- Entrance zones to public facilities with a social space value

- —

- Viewpoints accompanying pedestrian routes

- —

- Network of green walks for recreation in rural and natural landscapes.

3.5. Discussing of the Research Results

- —

- gateways to public utility facilities that are at the same time community spaces

- —

- benches with the view as viewpoints “en route”

- —

- a network of green walkways in peripheral areas intended for recreation in agricultural and natural landscapes

- —

- places that facilitate meetings (get-togethers):

- —

- of families and neighbors: estate courtyard, multi-recreational estate lawn, playground, diner's garden, open sports grounds, public allotment gardens, urban farm

- —

- of community/club members: open sports grounds, public allotment gardens

- —

- of those eager for contemplation: landscape corner, bench with a view, cemetery, landscape walkways

- —

- of casual bystanders: public gateway, playground, greenery site, shopping street, town square, multi-purpose school ground, cemetery, countryside promenade

- —

- of “gather and stare” partakers: public gateway, diner's garden, bench with a view, town square

- —

- places that serve:

- —

- active recreation: multi-recreational estate lawn, playground, open sports grounds, multi-purpose school ground, landscape walkways, countryside promenade, and (to some extent) public allotment gardens

- —

- leisure: estate courtyard, multi-recreational estate lawn, public gateway, greenery site, estate landscape corner, diner's garden, bench with a view, waterside corner, town square and landscape walkways.

4. Conclusions

5. POS Types Created Solely as a Result of Top-Down Planning and Design

5.1. Estates with a Recreational Areas Dedicated to the Neighborhood Community

5.1.1. Estate Courtyard

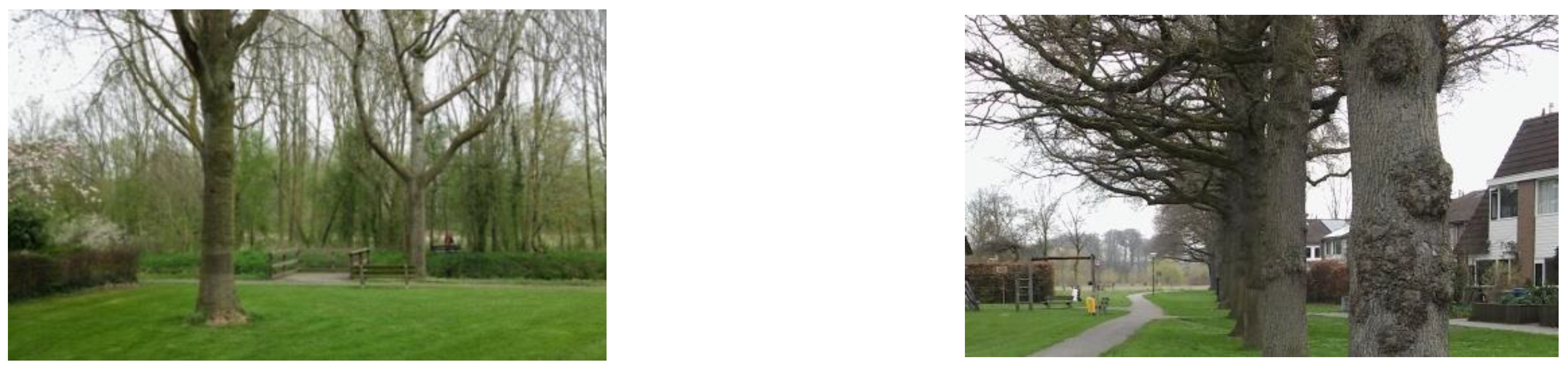

5.1.2. Multi-Recreational Estate Lawn

5.1.3. Estate Landscape Corner

5.2. Communal (Extra-Neighborhood) Playgrounds

The Playground

5.3. Greeneries by Pedestrian Routes

Greenery Site

5.4. Social Places in Central Zone

5.4.1. Shopping Street

5.4.2. Town Square

- —

- social (as a place for various types of meetings)

- —

- economic (some buildings and cabins serve as commercial and catering facilities)

- —

- natural (e.g., lawn with ornamental plants, the square overgrown with tall trees)

- —

- recreational (frequent of seats for passive relaxation, and paths for walks)

- —

- cultural (spatial arrangement with elements of street furniture, a vista from the square and objects of cultural and historical significance)

- —

- structural (objects forming a legible urban enclosure and mark points).

5.5. Open Sports Grounds in Every Countryside Town

Open Sports Grounds

5.6. Community Allotment Gardens in Every Countryside Town

Public Allotment Gardens

5.7. Multi-Purpose Recreational Areas at Schools, Available to Residents

Multi-Purpose School Grounds

5.8. Communal Facilities Generating Informal Meetings

Cemetery

6. POS Types Created as a Result of Both Top-Down Planning and Design and Bottom-Up Development:

6.1. Entrance Zones to Public Facilities with a Social Space Value

Public Gateway

6.2. Viewpoints Accompanying Pedestrian Routes

Bench with a View

6.3. Network of Green Walks for recreation in Rural and Natural Landscapes

6.3.1. Waterside Corner

6.3.2. Landscape Walkways

6.3.3. Countryside Promenade

7. Other POS Types (Resulting from Bottom-Up Development):

7.1. Diner's Garden

7.2. Urban Farm

8. Summary

- —

- Estates with a recreational areas dedicated to the neighborhood community: estate courtyard, multi-recreational estate lawn, estate landscape corner

- —

- Communal (extra-neighborhood) playgrounds: playground

- —

- Greeneries by pedestrian routes: greenery site

- —

- Social places in central zone: shopping street, town square

- —

- Multi-purpose recreational areas at schools, available to residents: multi-purpose school ground

- —

- Open sports grounds in every countryside town: open sports grounds

- —

- Community allotment gardens in every countryside town: public allotment gardens

- —

- Communal facilities generating informal meetings: cemetery

- —

- Entrance zones to public facilities with a social space value: public gateway

- —

- Viewpoints accompanying pedestrian routes: bench with a view

- —

- Network of green walks for recreation in rural and natural landscapes. landscape walkways, countryside promenade ,waterside corner

Funding

Appendix A. The Table with an Exemplary Characteristics of a POS Type (in this Case an Estate Courtyard)

| TYPE OF FEATURE | FEATURE DESCRIPTION | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Leading function | communication |

| 2 | Urban arrangement | urban enclosure of intimate scale (courtyard or small traffic island) |

| 3 | Equipment | always: paved surface (sidewalk, roadway, parking lot, square), lighting, waste bins; often: playground equipment, seats, grill;sometimes: a patch of grass |

| 4 | Presumed purpose | access to own property located in a housing estate |

| 5 | Accessibility (access zones: central, local, peripheral; type of traffic; access restrictions) | located in all access zones;available for road, bicycle and pedestrian traffic;local traffic only |

| 6 | Area size | medium |

| 7 | Presumed type of users | residents of the estate and their acquaintances |

| 8 | Presumed form of meetings and integration | always: informal meeting of the neighbors;often: socializing among neighbors (e. g., grilling, gardening, talking, sitting on benches, engaging in games; children playing) |

| 9 | Presumed type of leisure | sitting on benches; playing; grilling; gardening |

| 10 | Type of vegetation | Occasional: lawn, trees, ornamental plants |

| 11 | Landscape values | Small-town landscape |

| 12 | Spatial relations with the environment | in the heart of the estate, adjacent to the nearest street |

| 13 | Degree of urbanization of the area | high |

| 14 | Safety level | average due to traffic, but a very local one |

| 15 | Prevalence | numerous |

| 16 | Local or regional significance | local |

| 17 | Type of land ownership | property of the estate authorities |

| 18 | Observed top-down form of development | a place designed by the developer's designers |

Appendix B. Diagrams of POS Types

Appendix C. Photos of Exemplary POS Objects that Represent a Given Type, as well as Structural Models that Describe It

References

- Kępkowicz, Agnieszka (2023), “Method for creating public open space typology in line with the idea of place-making”, Mendeley Data, V1. [CrossRef]

- Airgood-Obrycki, W., Hanlon, B., & Rieger, S. (2021). Delineate the U.S. suburb: An examination of how different definitions of the suburbs matter. Journal of Urban Affairs, 43(9). [CrossRef]

- Al-hagla, K., & Al-hagla, K. (2008). Towards a sustainable neighborhood: the role of open spaces. International Journal of Architectural Research, 2(2).

- Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., & Silverstein, M. (1977). A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. University Press.

- Basu, R., & Fiedler, R. S. (2017). Integrative multiplicity through suburban realities: exploring diversity through public spaces in Scarborough. Urban Geography, 38(1). [CrossRef]

- Bell, P. A., Greene, T. C., Fisher, J. D., & Baum, A. S. (2001). Environmental Psychology (5th ed.). Harcourt College Publishers. [CrossRef]

- Bravo, L., & Crawford, M. (2014). Publics and their spaces. Renewing urbanity in city and suburb. New Urban Configurations.

- Buckenberger, C. (2015). Good Cities, Better Lives—How Europe Discovered the Lost Art of Urbanism. Housing Studies, 30(4). [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. (2010). Contemporary public space, part two: Classification. Journal of Urban Design, 15(2). [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. (2022). The existential crisis of traditional shopping streets: the sun model and the place attraction paradigm. Journal of Urban Design, 27(1). [CrossRef]

- Cattell, V., Dines, N., Gesler, W., & Curtis, S. (2008). Mingling, observing, and lingering: Everyday public spaces and their implications for well-being and social relations. Health and Place, 14(3). [CrossRef]

- Chase, J., Crawford, M., & John, K. (1999). Everyday Urbanism. New York: Monacal Press.

- Classification framework for public open space. healthier, happier and safer communities. (2012).

- Davidson, R. A. (2013). “Friendly authoritarianism” and the bedtaun: Public space in a Japanese suburb. Journal of Cultural Geography, 30(2). [CrossRef]

- Dines, N., Cattell, V., Gesler, W., & Curtis, S. (2006). Public spaces, social relations and well-being in East London. The Policy Press.

- Dinic, M., & Mitkovic, P. (2016). SUBURBAN DESIGN: FROM ``BEDROOM COMMUNITIES{’’} TO SUSTAINABLE NEIGHBORHOODS. GEODETSKI VESTNIK, 60(1). [CrossRef]

- Eriawan, T., & Setiawati, L. (2017, June 15). Improving the quality of urban public space through the identification of space utilization index at Imam Bonjol Park, Padang city. AIP Conference Proceedings 1855, 040018 (2017).

- Fieldhouse, K. (2002). Parks and green spaces: Unlocking a fresh vision. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: Municipal Engineer, 151(3). [CrossRef]

- Flusty, S. (2021). Building paranoia. In Public Space Reader. [CrossRef]

- Francis, M., & Griffith, L. (2011). The meaning and design of farmers’ markets as public space: An issue- based case study. In Landscape Journal (Vol. 30, Issue 2). [CrossRef]

- Gachowski, M. (2008). Przestrzeń publiczna w mieście jako towar pożądany, przestrzeń publiczna w mieście jako towar niebezpieczny. Biblioteka “Urbanisty”.

- Galle, M., & Modderman, E. (1997). Vinex: national spatial planning policy in the netherlands during the nineties. Netherlands Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 12(1), 9–35. [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. (2011). Life between Buildings: Using Public Space. Washington DC: Island Press.

- Gehl, J., & Gemzøe, L. (2001). New city spaces (2. rev. ed). The Danish Architectural Press.

- Goffman, E. (1966). Behavior in Public Places: Notes on the Social Organization of Gatherings. Free Press.

- Google Maps. (n.d.). Retrieved December 3, 2022. Available online: https://www.google.pl/maps/.

- Gulick, J. (1997). The ``Disappearance of Public Space’’: An Ecological Marxist and {L}efebvrian Approach. In Philosophy and Geography II: The Production of Public Space.

- Hall, P. (2021). Building Sustainable Suburbs in the Netherlands. In Routledge (Ed.), Good Cities, Better Lives. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/mono/10.4324/9781315888446-13/building-sustainable-suburbs-netherlands-peter-hall.

- Harris, R. (2015). Using Toronto to explore three suburban stereotypes, and vice versa. Environment and Planning A, 47(1). [CrossRef]

- Harris, R., & Lehrer, U. (2018). The Suburban land question: A global survey. In The Suburban Land Question: A Global Survey.

- Horrigan, D. (2019, May 16). Why Public Spaces Are Critical Social Infrastructure. GOVERNING - The Future of States and Localities. Available online: https://www.governing.com/gov-institute/voices/col-parks-community-centers-public-spaces-critical-social-infrastructure.html.

- Huang, Y., Hui, E. C. M., Zhou, J., Lang, W., Chen, T., & Li, X. (2020). Rural Revitalization in China: Land-Use Optimization through the Practice of Place-making. Land Use Policy, 97. [CrossRef]

- Jałowiecki, B. (2010). Społeczne wytwarzanie przestrzeni. Scholar.

- Karsten, L., Lupi, T., & Stigter-Speksnijder de, M. (2013). The middle classes and the remaking of the suburban family community: Evidence from the Netherlands. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 28(2). [CrossRef]

- Kępkowicz, A. (2019). Identyfikacja typów przestrzeni publicznej. In Identyfikacja typów przestrzeni publicznej. University of Warsaw PRESS. [CrossRef]

- Kępkowicz, A., Lipińska, H., & Mantey, D. (2019). Suburbs vs Third Places? IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 471(9). [CrossRef]

- Kępkowicz, A., & Mantey, D. (2016). Suburbs as None-Places? The Need for Gathering Places: a Case Study of the Warsaw Suburbs. Landscape Architecture, 1, 67–83.

- Kępkowicz, A., Mantey, D., Lipińska, H., & Wańkowicz, W. (2014). The “club” landscape as an kind of substitutive public spaces of suburbia (Krajobraz „klubowy” jako wyraz substytutywnych przestrzeni publicznych suburbiów). Architektura Krajobrazu, 3, 67–83.

- Kohn, M. (2021). Brave new neighborhoods: The privatization of public space. In Public Space Reader. [CrossRef]

- Lörzing, H. (2006). Reinventing Suburbia in the Netherlands. Built Environment, 32(3). [CrossRef]

- Ma, X., Tian, Y., Du, M., Hong, B., & Lin, B. (2021). How to design comfortable open spaces for the elderly? Implications of their thermal perceptions in an urban park. Science of the Total Environment, 768. [CrossRef]

- Madden, K., Wiley-Schwartz, A., & Antoshak, A. (2010). How to Turn a Place Around: A Handbook for Creating Successful Public Spaces. NY: Project for Public Spaces.

- Majer, A. (2010). Socjologia i przestrzeń miejska. WN PWN.

- Malone, K. (2002). Street life: Youth, culture and competing uses of public space. Environment and Urbanization, 14(2). [CrossRef]

- Mantey, D. (2017). The ‘publicness’ of suburban gathering places: The example of Podkowa Leśna (Warsaw urban region, Poland). Cities, 60. [CrossRef]

- Mantey, D., & Kępkowicz, A. (2018). Types of Public Spaces: The Polish Contribution to the Discussion of Suburban Public Space. Professional Geographer, 70(4). [CrossRef]

- Mantey, D., & Kępkowicz, A. (2020). Models of community-friendly recreational public space in warsaw suburbs. Methodological approach. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(17). [CrossRef]

- Mantey, D., & Sudra, P. (2019). Types of suburbs in post-socialist Poland and their potential for creating public spaces. Cities, 88. [CrossRef]

- Martinuzzi, C., & Lahoud, C. (2020). Public space site-specific assessment Guidelines to achieve quality public spaces at neighbourhood level (C. Andersson (Ed.)). United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat).

- McCormick, K. (2016, April 29). More Open Space, Walkability, and Multifamily Are Future of Suburbs. Urban Land Magazine.

- Muminovic, M., & Caton, H. (2018). Sustaining suburbia - The importance of the public private interface in the case of Canberra, Australia. Archnet-IJAR, 12(3). [CrossRef]

- Nochian, A., Mohd Tahir, O., Maulan, S., & Rakhshandehroo, M. (2015). A comprehensive public open space categorization using classification system for sustainable development of public open spaces. ALAM CIPTA, International Journal on Sustainable Tropical Design Research & Practice, 8(spec.1).

- Oldenburg, R. (1989). The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Community Centers, Beauty Parlors, General Stores, Bars, Hangouts and How They Get You Through the Day (1st ed.). Paragon House.

- OpenStreetMap. (n.d.). Retrieved June 5, 2022. Available online: https://www.openstreetmap.org/.

- Parker, C. (2021). Homelessness in the public landscape: A typology of informal infrastructure. Landscape Journal, 40(1). [CrossRef]

- Parysek, J. (2011). University of British Columbia w Vancouver (Kanada) jako przestrzeń publiczna szczególnego rodzaju. In Przestrzeń publiczna miast (pp. 51-67.). Wydawnictwo UŁ.

- Peng, Y., Feng, T., & Timmermans, H. J. P. (2021). Heterogeneity in outdoor comfort assessment in urban public spaces. Science of The Total Environment, 790, 147941. [CrossRef]

- Piątkowska, K. (1983). Zieleń i wypoczynek. Instytut Kształtowania Środowiska.

- Praliya, S., & Garg, P. (2019). Public space quality evaluation: prerequisite for public space management. The Journal of Public Space, 4 n 1.

- Project for Public Spaces. (2016, March 3). You Asked, We Answered: 6 Examples of What Makes a Great Public Space. Available online: https://www.pps.org/article/you-asked-we-answered-6-examples-of-what-makes-a-great-public-space.

- Remøy, H., & Street, E. (2018). ‘The dynamics of “post-crisis” spatial planning: A comparative study of office conversion policies in England and The Netherlands. Land Use Policy, 77. [CrossRef]

- Rogowska, M. (2014). The quality of public space in the development of urban areas. Research Papers of Wrocław University of Economics - Local and Regional , No 334, 223–230.

- Sibley, D. (1995). Geographies of Exclusion Society and Difference in the West (1 st.). Routledge.

- Solecka, I., Rinne, T., Caracciolo Martins, R., Kytta, M., & Albert, C. (2022). Important places in landscape – investigating the determinants of perceived landscape value in the suburban area of Wrocław, Poland. Landscape and Urban Planning, 218. [CrossRef]

- Stanley, B., Stark, B., Johnston, K., & Smith, M. (2012). Urban open spaces in historical perspective: A transdisciplinary typology and analysis. In Urban Geography (Vol. 33, Issue 8). [CrossRef]

- StoneCreek Partners. (2015). Gathering Places, Available online: https://stonecreekllc.com/.

- Szumański, M. (2005). Strukturalizacja terenów zieleni. Wydawnictwo SGGW.

- Tao, H., Zhou, Q., Tian, D., & Zhu, L. (2022). The Effect of Leisure Involvement on Place Attachment: Flow Experience as Mediating Role. Land, 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Van Melik, R., Van Aalst, I., & Van Weesep, J. (2007). Fear and fantasy in the public domain: The development of secured and themed urban space. Journal of Urban Design, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Veal, A. J. (1992). Definitions of Leisure and Recreation. Australian Journal of Leisure and Recreation, 2(52).

- Villanueva, K., Badland, H., Hooper, P., Koohsari, M. J., Mavoa, S., Davern, M., Roberts, R., Goldfeld, S., & Giles-Corti, B. (2015). Developing indicators of public open space to promote health and wellbeing in communities. Applied Geography, 57. [CrossRef]

- Visser, A. J., Jansma, J. E., Schoorlemmer, H., & Slingerland, M. (2009). How to deal with competing claims in peri-urban design and development: The DEED framework in the agromere project. In Transitions Towards Sustainable Agriculture and Food Chains in Peri-Urban Areas. [CrossRef]

- Woolley, H., Rose, S., Carmona, M., & Freedman, J. (2003). The Value of Public Space How high quality parks and public spaces create economic, social and environmental value. In https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/asset/document/the-value-of-public-space1.pdf. CABE Space.

- Worpole, K., & Knox, K. (2007). The social value of public spaces.

| 1 | A detailed discussion of the arguments for choosing the Bunnik municipality as a case study is provided in the subsection 1.1. and 3.1. |

| No. | POS type | Bunnik | Odijk | Werk | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Estate courtyard | 8 | 11 | 9 | 28 |

| 2 | Multi-recreational estate lawn | 10 | 8 | 1 | 19 |

| 3 | Public gateway | 11 | 3 | 3 | 17 |

| 4 | Playground | 7 | 3 | - | 10 |

| 5 | Greenery site | 5 | 3 | 1 | 9 |

| 6 | Estate landscape corner | 3 | 3 | 1 | 7 |

| 7 | Diner’s garden | 5 | - | - | 5 |

| 8 | Bench with a view | - | - | 4 | 4 |

| 9 | Waterside corner | 2 | 2 | - | 4 |

| 10 | Shopping street | 2 | 1 | - | 3 |

| 11 | Open sports grounds | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 12 | Public allotment gardens | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 13 | Town square | - | - | 2 | 2 |

| 14 | Multi-purpose school grounds | 1 | - | 1 | 2 |

| 15 | Cemetery | 1 | 1 | - | 2 |

| 16 | Landscape walkways | 1 | 1 | - | 2 |

| 17 | Urban farm | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| 18 | Countryside promenade | 1 | - | - | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).