Submitted:

07 August 2024

Posted:

08 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

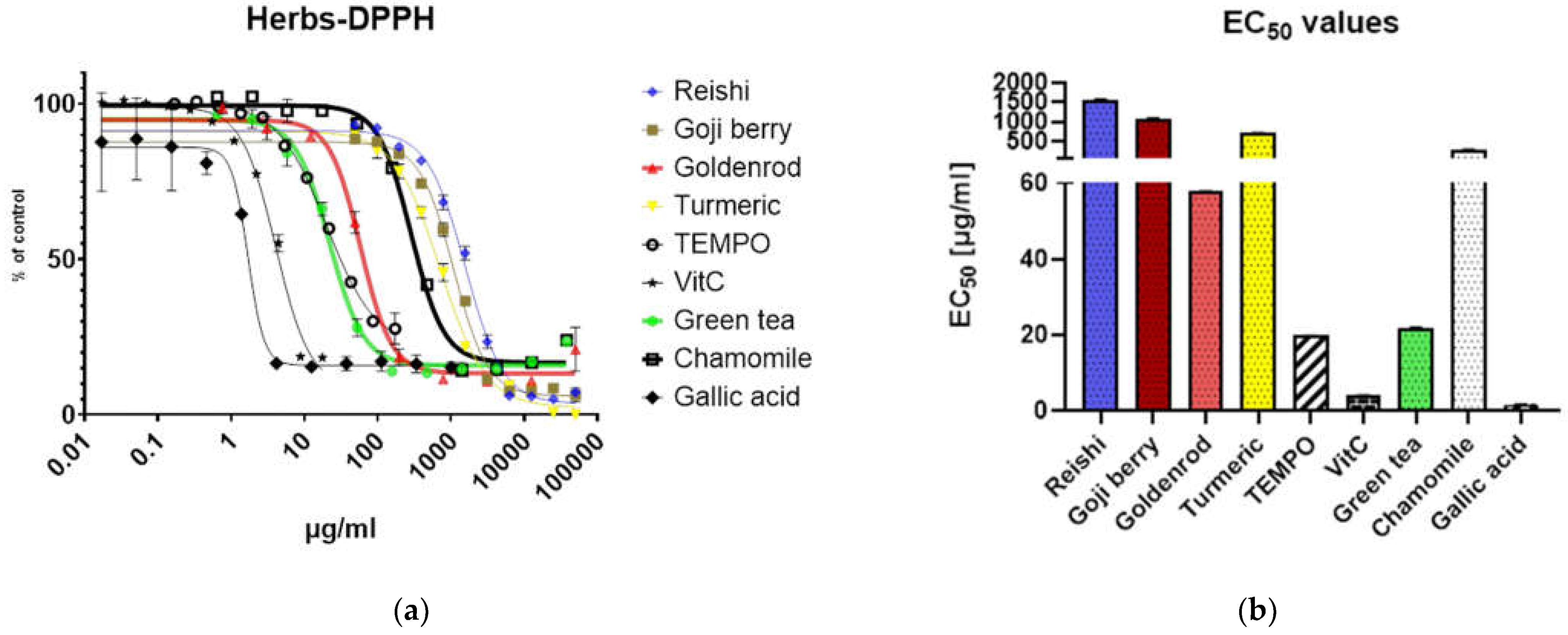

2.1. Definition of Reagents

2.1.1. Herbal Extracts and Solvents

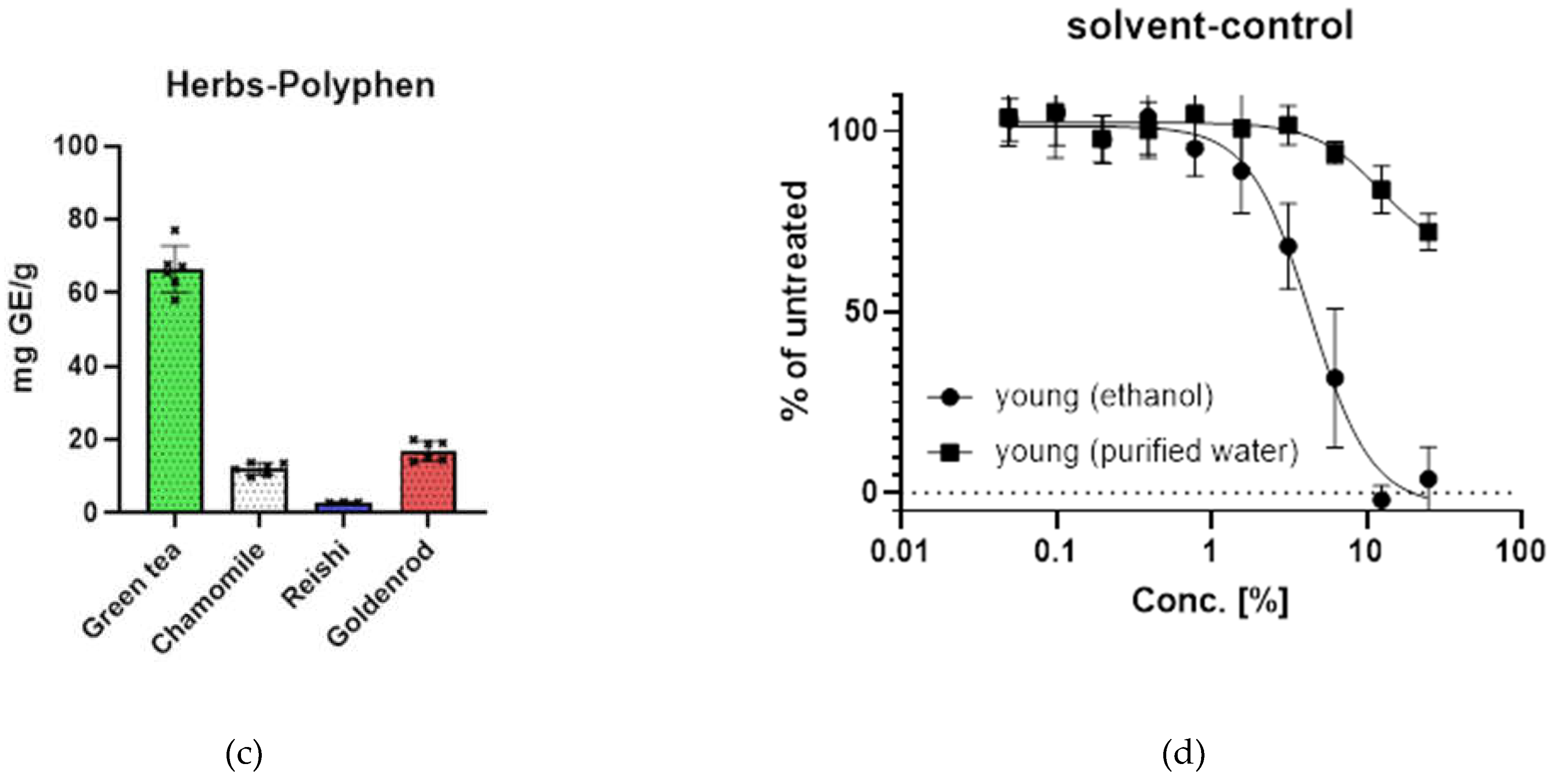

2.1.2. Cell Lines and Establishment of the Senescent State

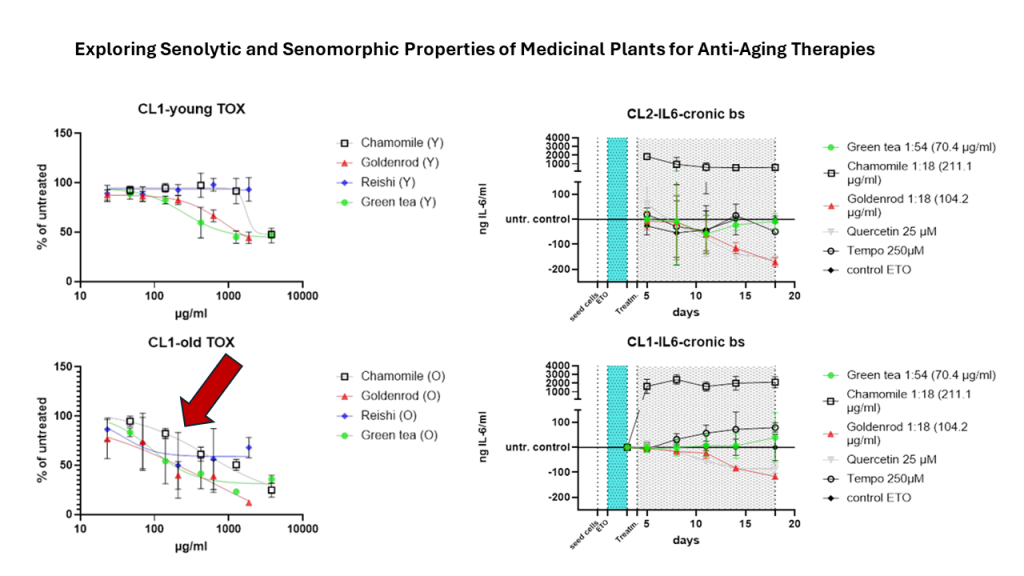

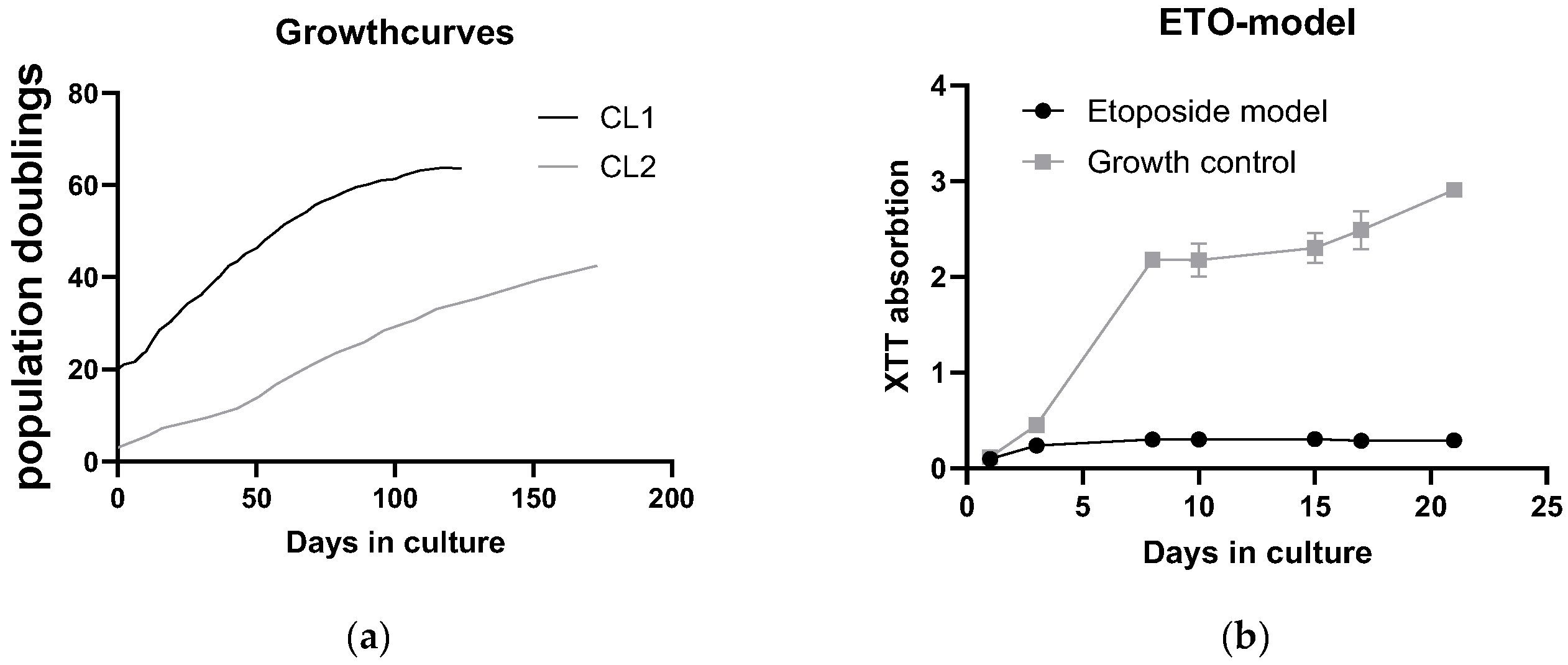

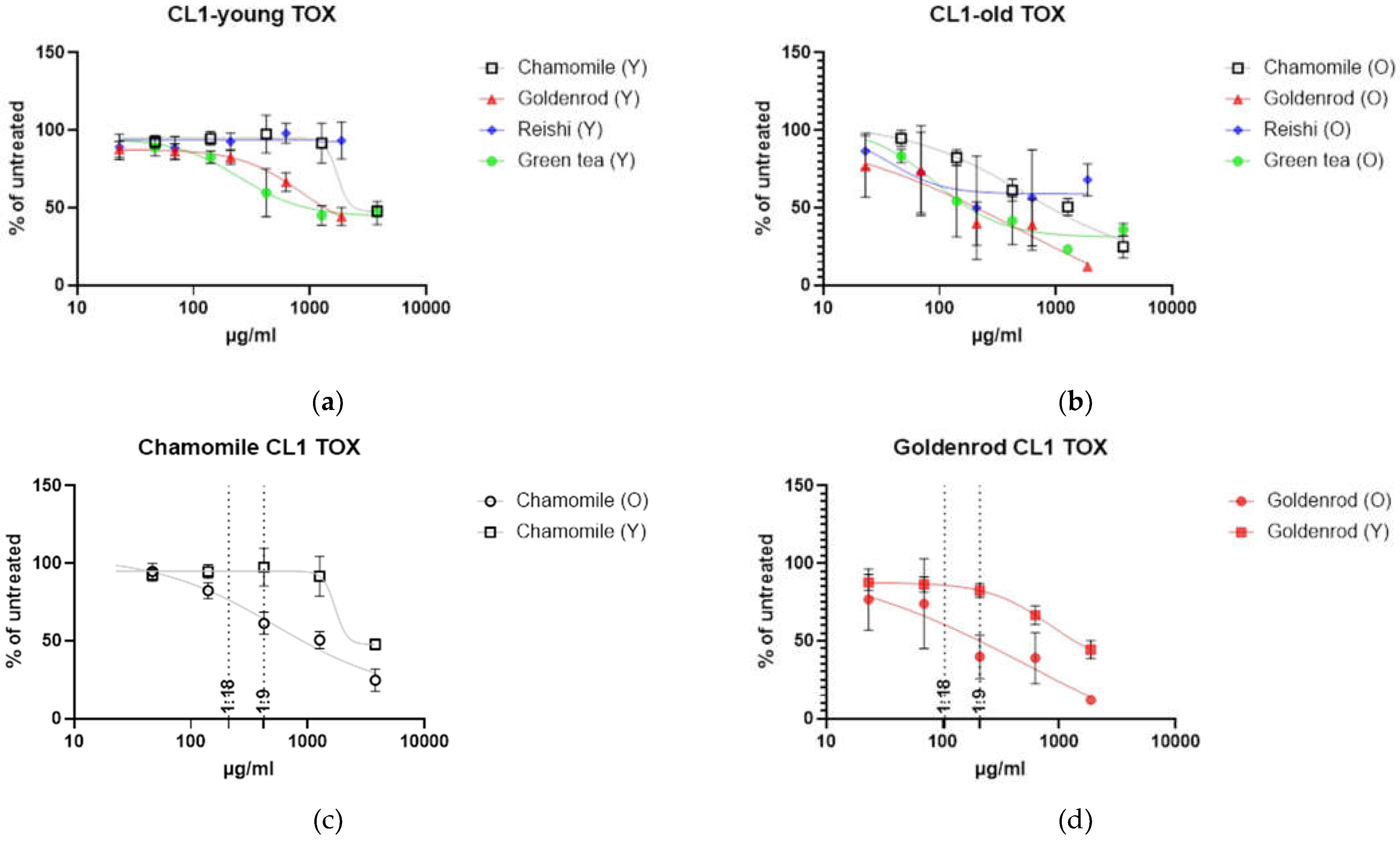

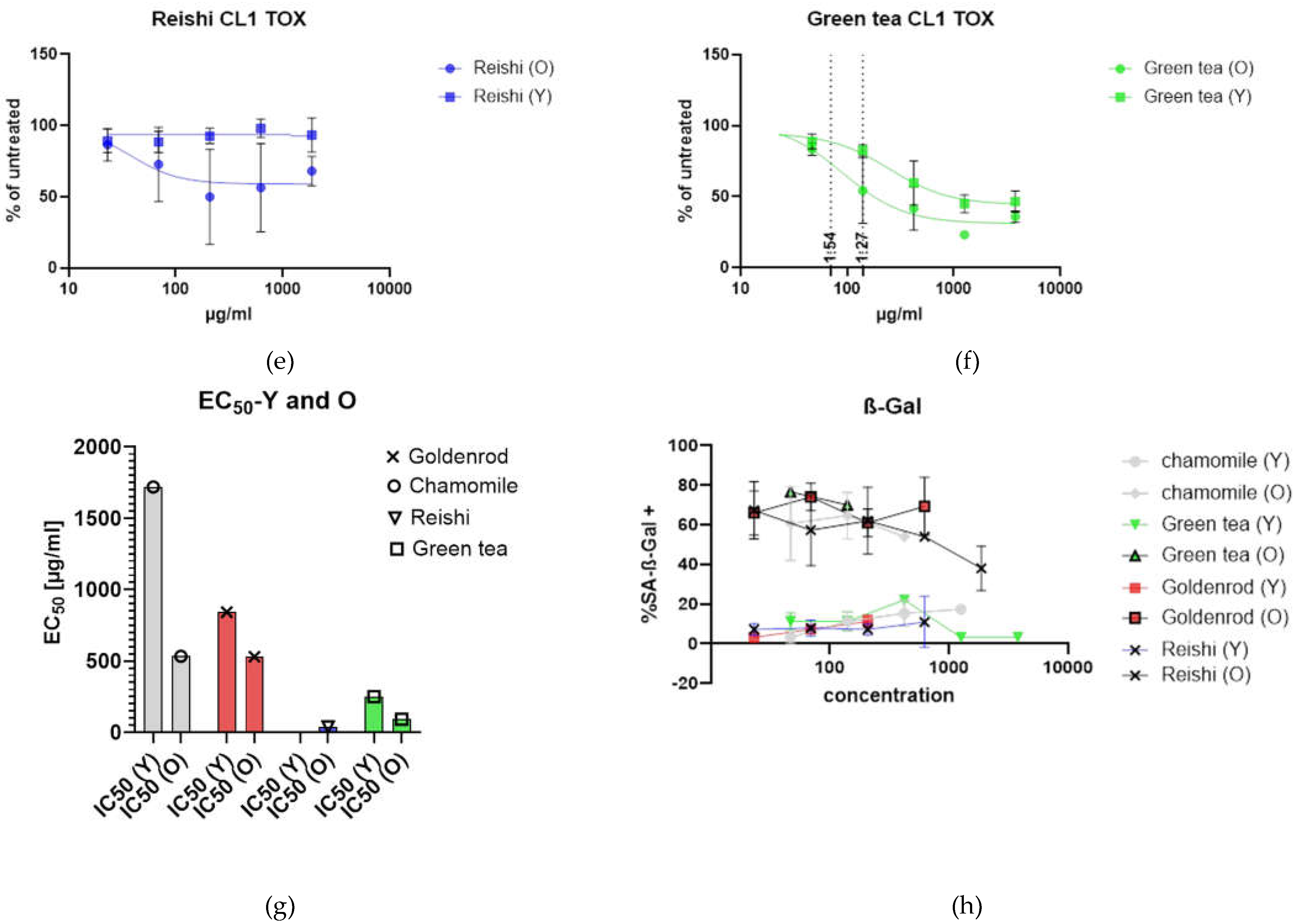

2.2. Toxicology of Herbal Extracts

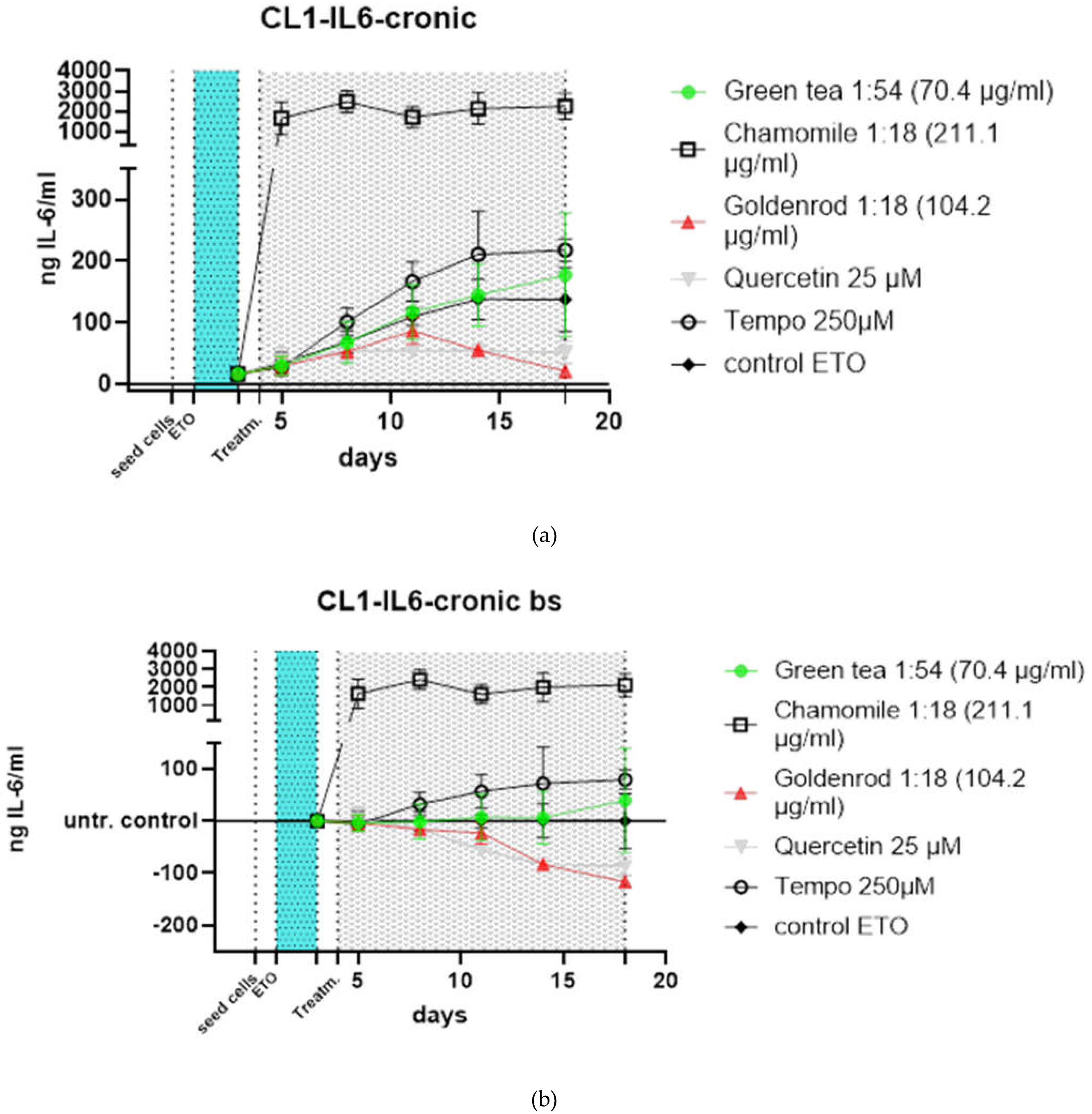

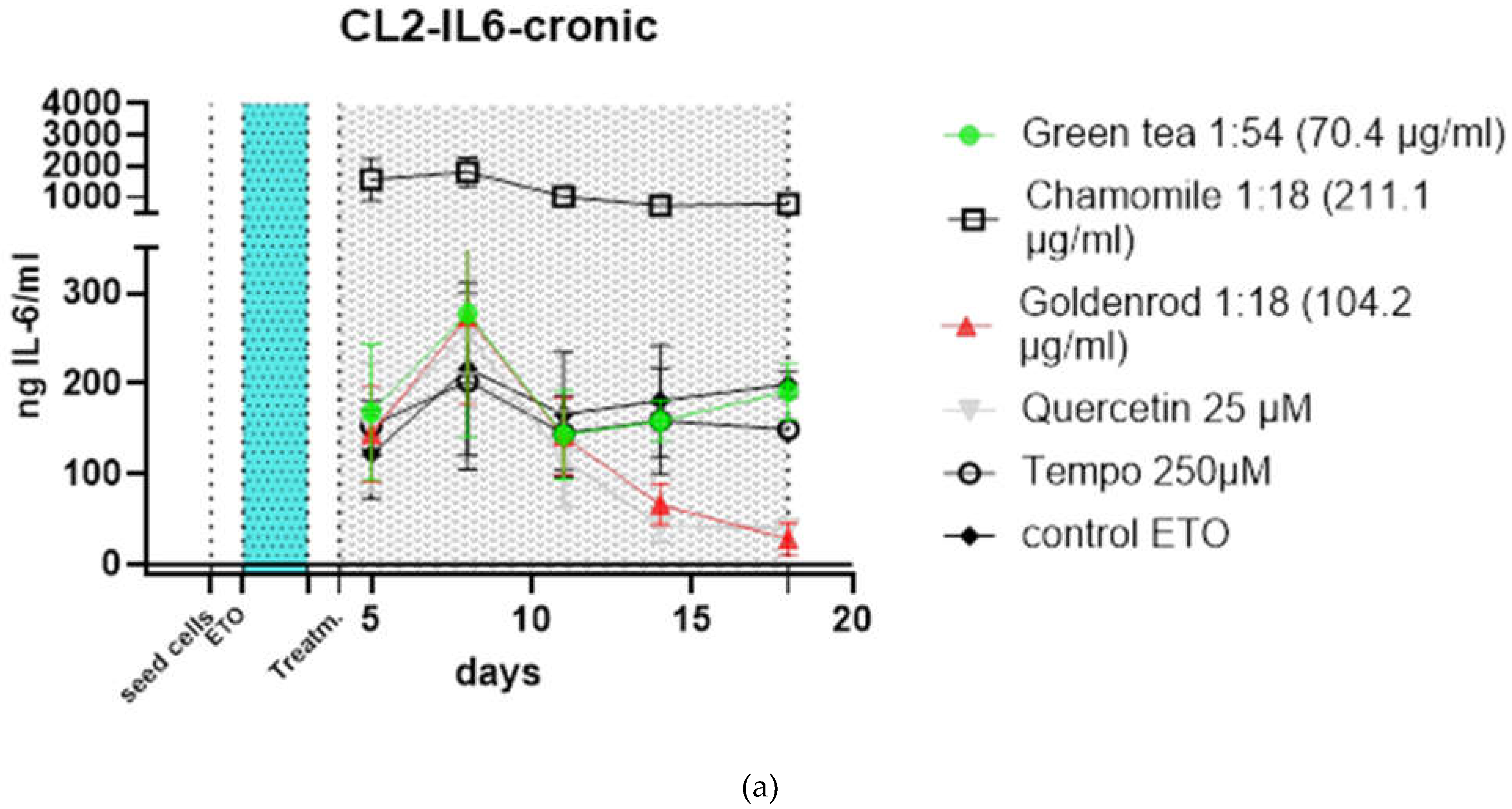

2.3. Chronic Extract Treatment Cell Line 1

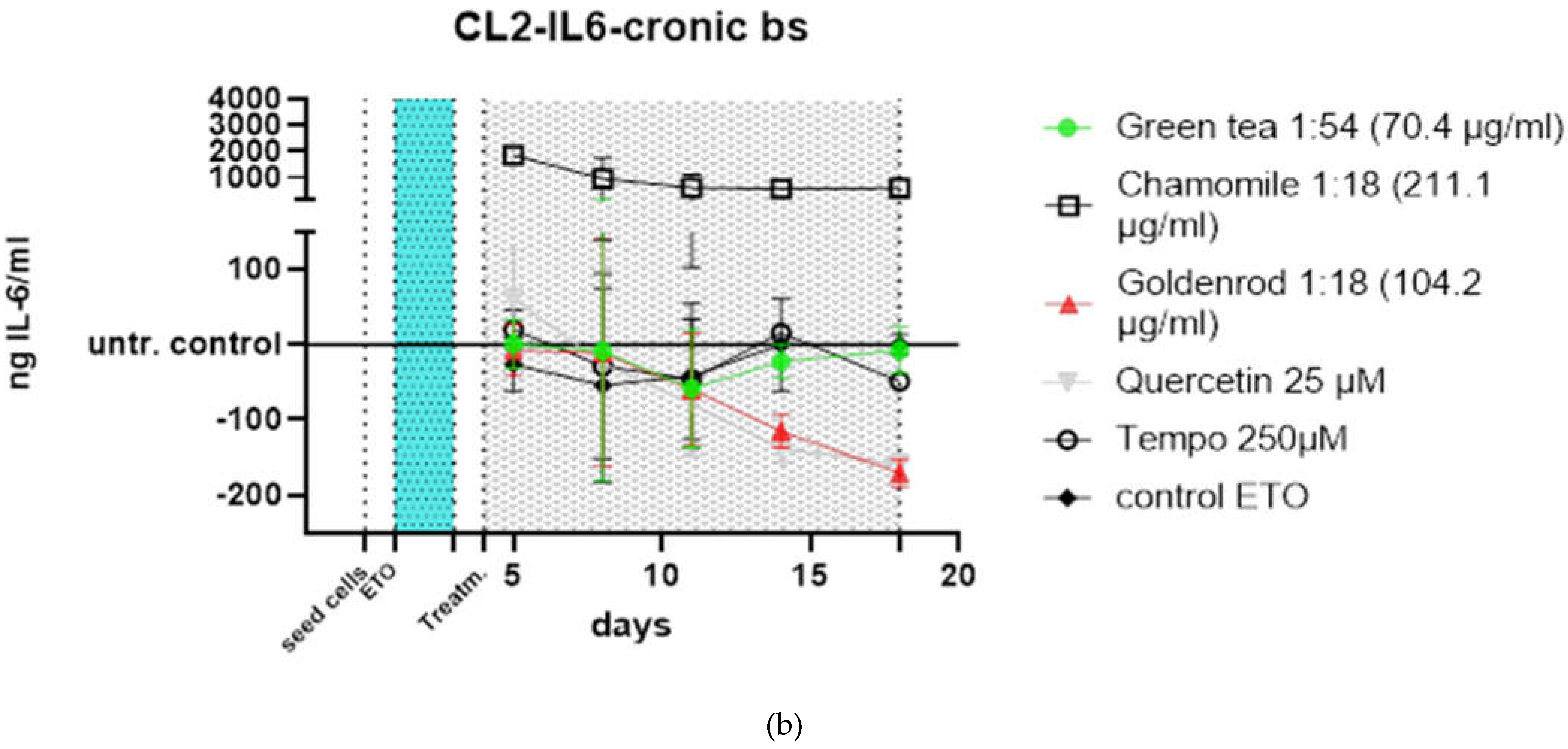

2.3.1. IL-6 Secretion (SASP Formation)

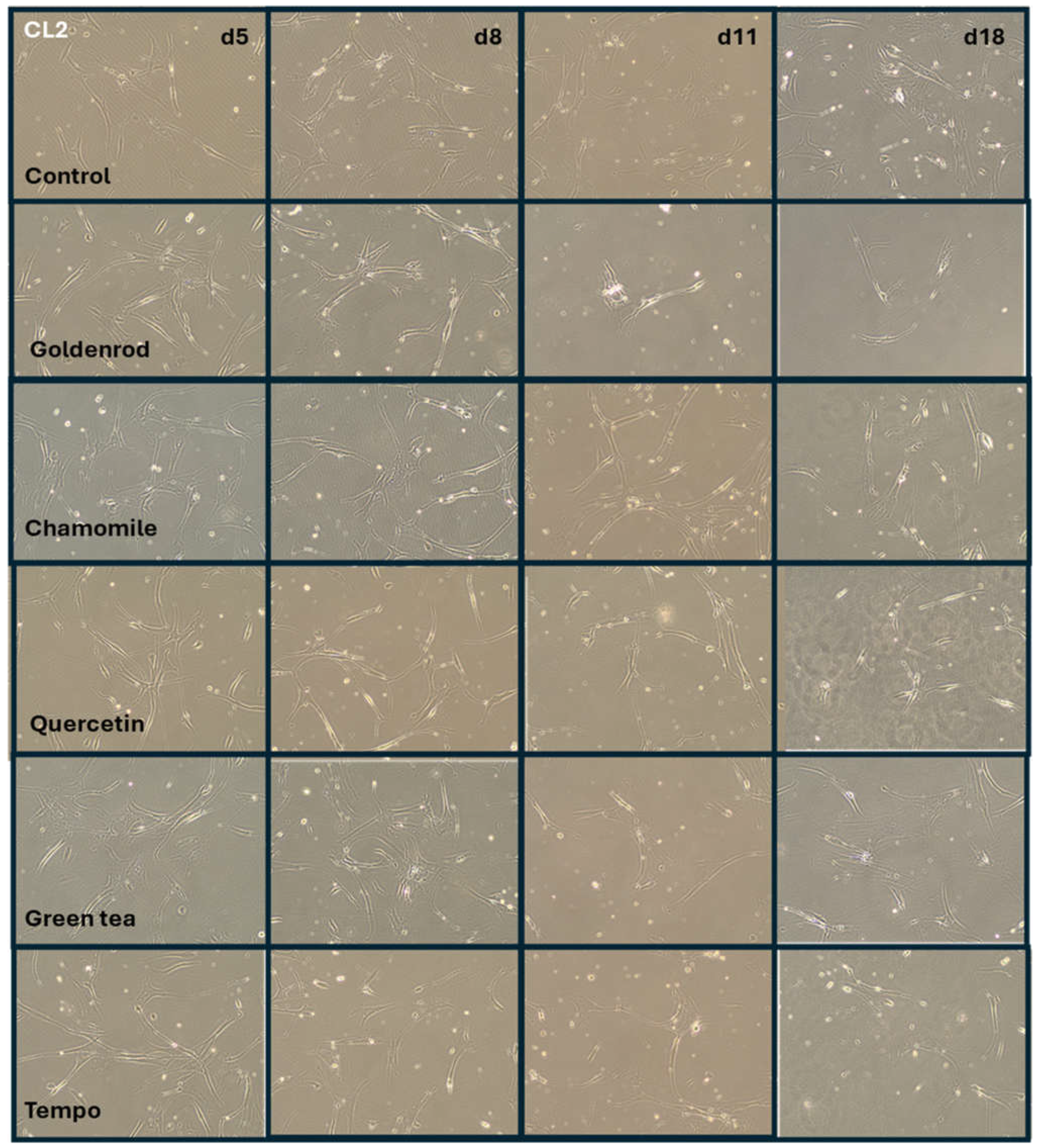

2.3.2. Cell Confluency and Morphology

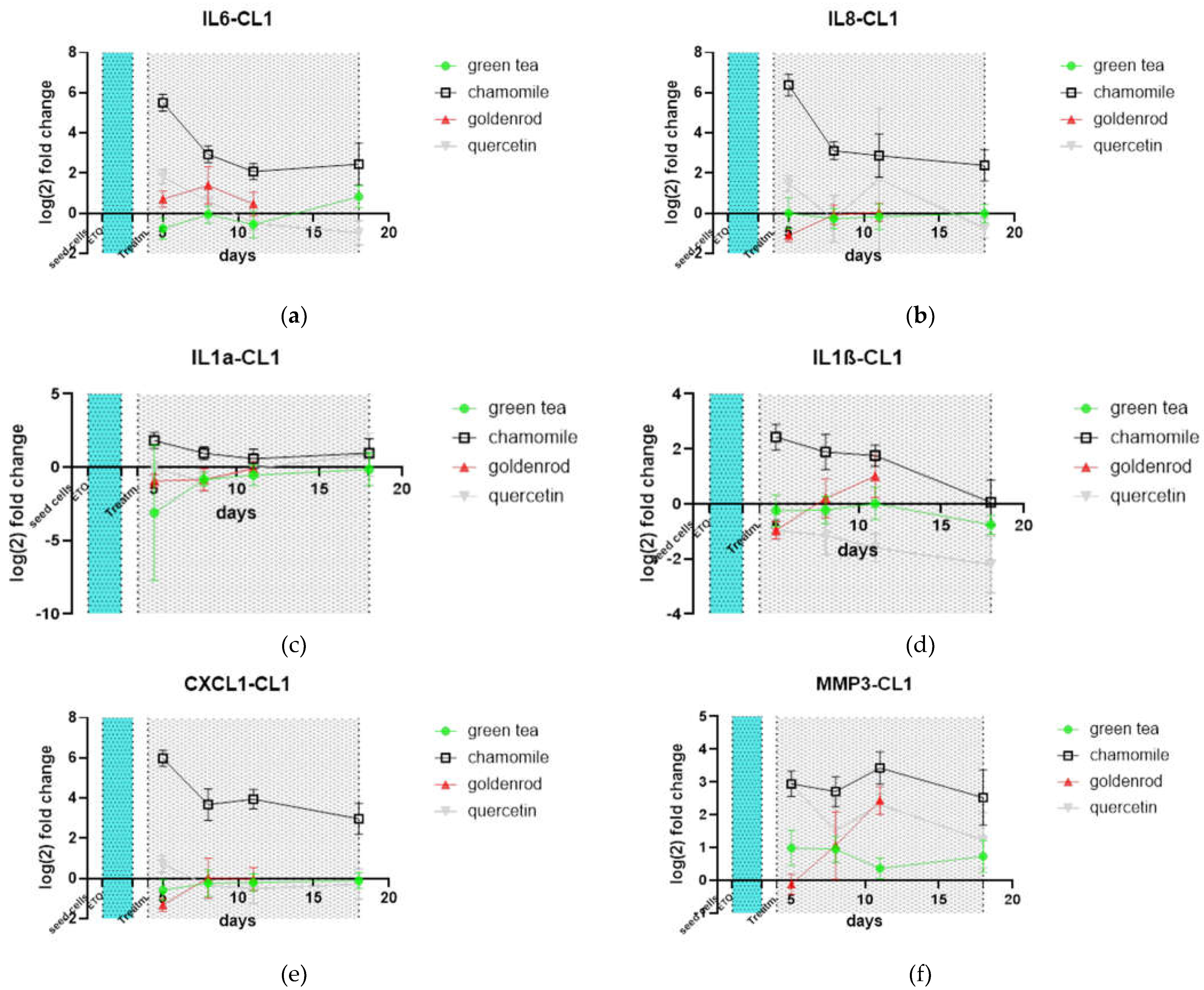

2.3.3. qPCR Investigations of SASP Related mRNA Expression

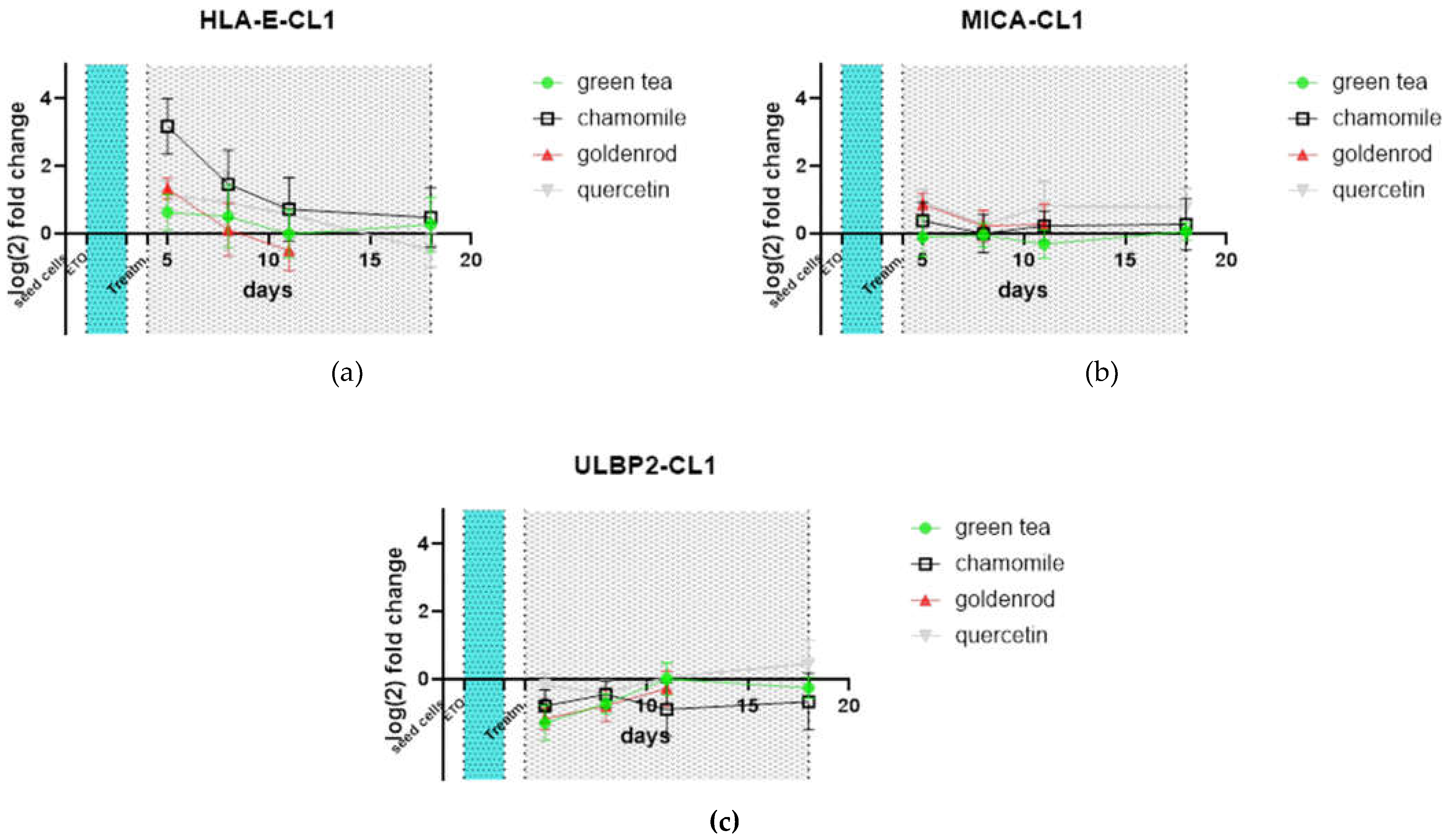

2.3.4. Cell Line 1 Receptors

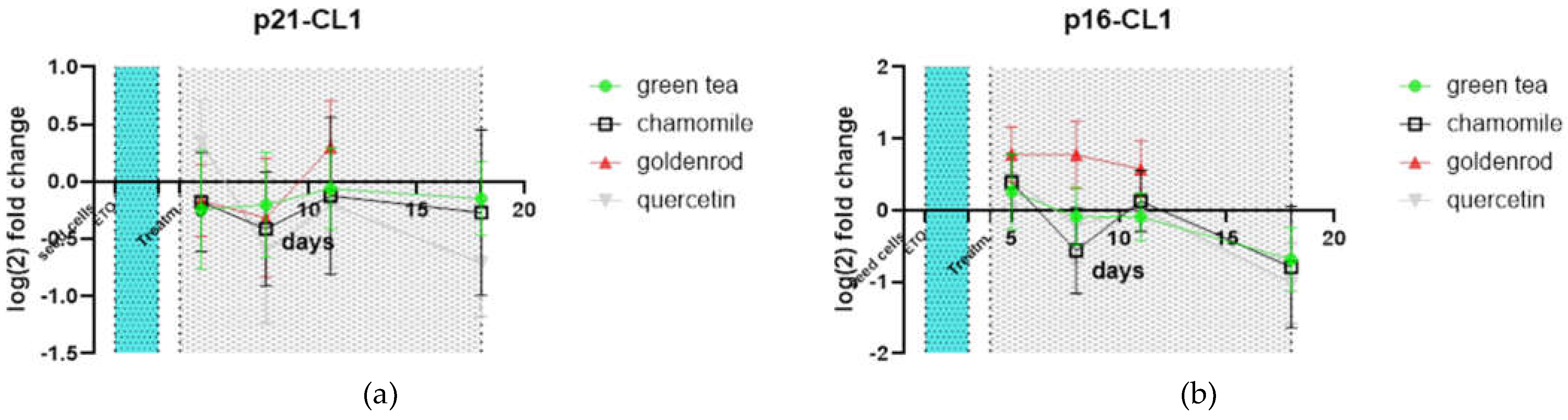

2.3.5. Senescence Related Genes (CL1)

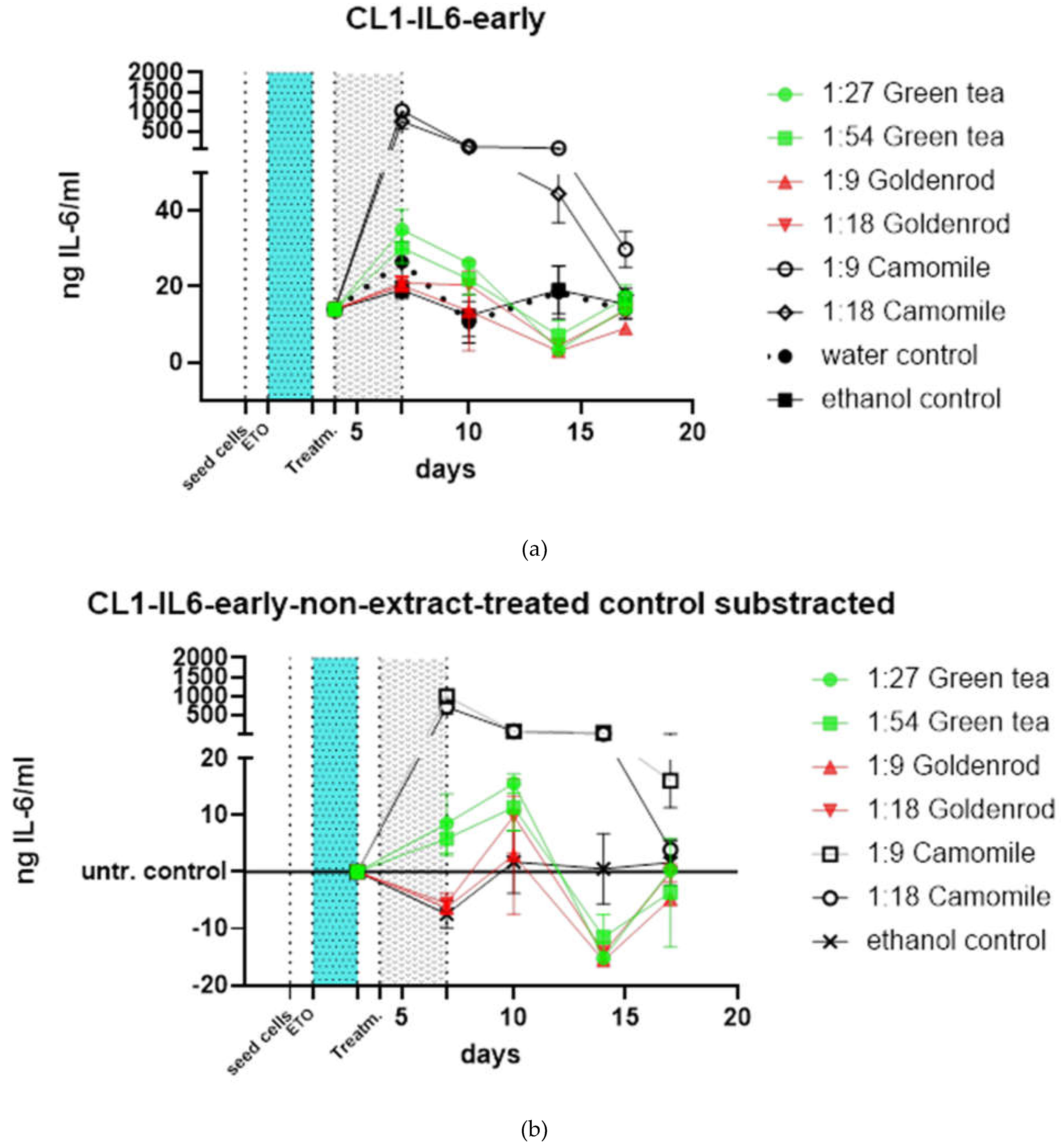

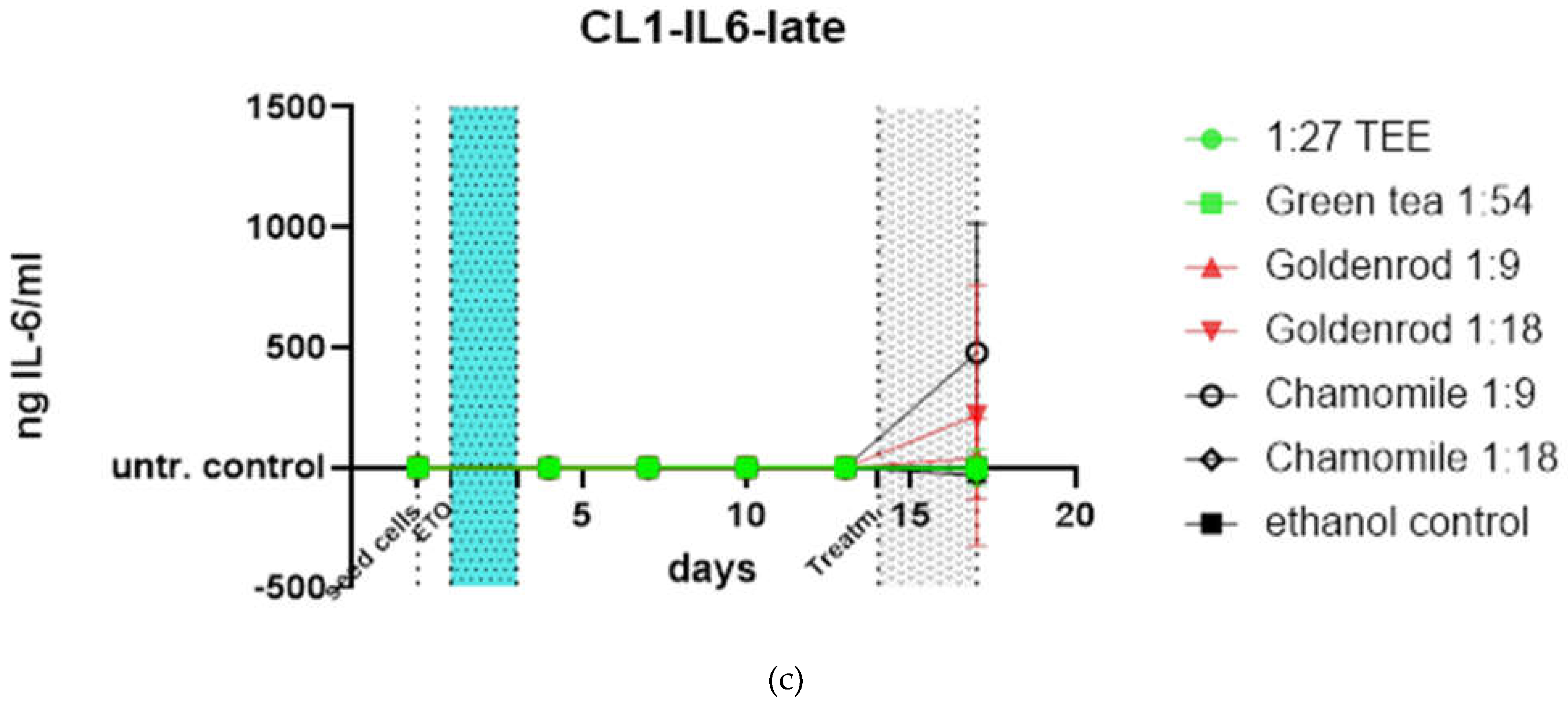

2.4. Early and Late Treatment with Herbal Extracts

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cells

4.1.1. Toxicity Testing and SA-ß-Gal Assay

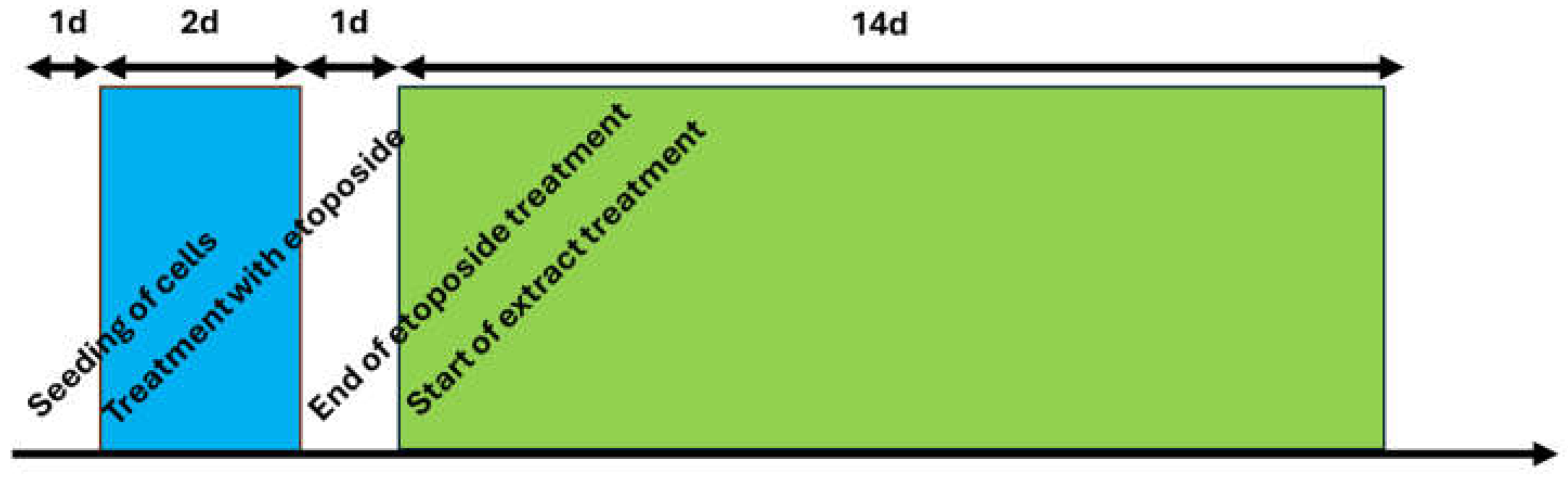

4.1.2. Main Experiment Chronical Extract Treatment for IL-6 Elisa and pPCR Investigations

| Chamomile | Green tea | Goldenrod | Reishi |

| 1:1 means 3,8 mg/mL | 1:1 means 3,8 mg/mL | 1:1 means 1.875 mg/mL | 1:1 means 1.875 mg/mL |

| 1:3 means 1,2666 mg/mL | 1:3 means 1,2666 mg/mL | 1:3 means 0.6250 mg/mL | 1:3 means 0.6250 mg/mL |

| 1:9 means 0,4222 mg/mL | 1:9 means 0,4222 mg/mL | 1:9 means 0.2083 mg/mL | 1:9 means 0.2083 mg/mL |

| 1:18 means 0.2111 mg/mL | 1:27 means 0,1407 mg/mL | 1:18 means 0.1042 mg/mL | 1:27 means 0.0694 mg/mL |

| 1:27 means 0,1407 mg/mL | 1:54 means 0.0704 mg/mL | 1:27 means 0.0694 mg/mL | 1:81 means 0.0231 mg/mL |

| 1:81 means 0,0469 mg/mL | 1:81 means 0.0469 mg/mL | 1:81 means 0.0231 mg/mL |

4.2. Preparation of Extracts

4.3. DPPH-Assay

4.4. Folin-Ciocalteu Assay

4.5. XTT (2,3-Bis-(2-Methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide) Assay

4.6. Senescence Associated ß Galactosidase (SA-ß-gal) Assay

4.7. IL-6 ELISA

4.8. Presto Blue Assay

4.9. RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis and qPCR

| Name | Forward (5’-3’) | Reverse (5’-3’) | Ref |

| p16INK4a | GAGCAGCATGGAGCCTTC | CGTAACTATTCGGTGCGTTG | [55] |

| p21 | GGCAGACCAGCATGACAGATTTC | CGGATTAGGGCTTCCTCTTGG | [56] |

| IL-1a | GGTTGAGTTTAAGCCAATCCA | TGCTGACCTAGGCTTGATGA | [55] |

| IL-1b | ACAGATGAAGTGCTCCTTCCA | GTCGGAGATTCGTAGCTGGAT | [57] |

| IL-6 | GCCCAGCTATGAACTCCTTCT | GAAGGCAGCAGGCAACAC | [55] |

| IL-8 | AGACAGCAGAGCACACAAGC | ATGGTTCCTTCCGGTGGT | [55] |

| CXCL1 | GAAAGCTTGCCTCAATCCTG | CACCAGTGAGCTTCCTCCTC | [58] |

| GAPDH | CGACCACTTTGTCAAGCTCA | TGTGAGGAGGGGAGATTCAG | [59] |

| Actin ß | CCAACCGCGAGAAGATGA | CCAGAGGCGTACAGGGATAG | [60] |

| MMP-3 | CAAAACATATTTCTTTGTAGAGGACAA | TTCAGCTATTTGCTTGGGAAA | [55] |

| HLA-E | TGCGCGGCTACTACAATCAG | TGTCGCTCCACTCAGCCTTC | [61] |

| MICA | ATGGAACACAGCGGGAATCA | GCACTTTCCCAGAGGGCAC | [54] |

| ULBP2 | TCCAGGCTCTCCTTCCATCA | AGAAGGATCTTGGTAGCGGC | [54] |

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hayflick, L. The Limited in Vitro Lifetime of Human Diploid Cell Strains. Exp Cell Res 1965, 37, 614–636. [CrossRef]

- Hayflick, L.; Moorhead, P.S. The Serial Cultivation of Human Diploid Cell Strains. Exp Cell Res 1961, 25, 585–621. [CrossRef]

- Campisi, J.; Di d’Adda Fagagna, F. Cellular Senescence: When Bad Things Happen to Good Cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007, 8, 729–740. [CrossRef]

- Sharpless, N.E.; Sherr, C.J. Forging a Signature of in Vivo Senescence. Nat Rev Cancer 2015, 15, 397–408. [CrossRef]

- Campisi, J. Aging, Cellular Senescence, and Cancer. Annu Rev Physiol 2013, 75, 685–705. [CrossRef]

- Short, S.; Fielder, E.; Miwa, S.; Zglinicki, T. Senolytics and Senostatics as Adjuvant Tumour Therapy. EBioMedicine 2019, 41, 683–692. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Espín, D.; Serrano, M. Cellular Senescence: From Physiology to Pathology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014, 15, 482–496. [CrossRef]

- Childs, B.G.; Baker, D.J.; Kirkland, J.L.; Campisi, J.; van Deursen, J.M. Senescence and Apoptosis: Dueling or Complementary Cell Fates? EMBO Rep 2014, 15, 1139–1153. [CrossRef]

- Yosef, R.; Pilpel, N.; Tokarsky-Amiel, R.; Biran, A.; Ovadya, Y.; Cohen, S.; Vadai, E.; Dassa, L.; Shahar, E.; Condiotti, R.; et al. Directed Elimination of Senescent Cells by Inhibition of BCL-W and BCL-XL. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 11190. [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.J.; Wijshake, T.; Tchkonia, T.; LeBrasseur, N.K.; Childs, B.G.; Sluis, B. van de; Kirkland, J.L.; Deursen, J.M. van Clearance of P16Ink4apositive Senescent Cells Delays Ageingassociated Disorders. Nature 2011, 479, 232. [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.J.; Childs, B.G.; Durik, M.; Wijers, M.E.; Sieben, C.J.; Zhong, J.; A. Saltness, R.; Jeganathan, K.B.; Verzosa, G.C.; Pezeshki, A.; et al. Naturally Occurring P16Ink4a-Positive Cells Shorten Healthy Lifespan. Nature 2016, 530, 184–189. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Tchkonia, T.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Gower, A.C.; Ding, H.; Giorgadze, N.; Palmer, A.K.; Ikeno, Y.; Hubbard, G.B.; Lenburg, M.; et al. The Achilles’ Heel of Senescent Cells: From Transcriptome to Senolytic Drugs. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 644–658. [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, J.L.; Tchkonia, T. Cellular Senescence: A Translational Perspective. EBioMedicine 2017, 21, 21–28. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, O.H.; Kim, C.; Laberge, R.M.; Demaria, M.; Rathod, S.; Vasserot, A.P.; Chung, J.W.; Kim, D.H.; Poon, Y.; David, N.; et al. Local Clearance of Senescent Cells Attenuates the Development of Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis and Creates a pro-Regenerative Environment. Nat Med 2017, 23, 775–781. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Farr, J.N.; Weigand, B.M.; Palmer, A.K.; Weivoda, M.M.; Inman, C.L.; Ogrodnik, M.B.; Hachfeld, C.M.; Fraser, D.G.; et al. Senolytics Improve Physical Function and Increase Lifespan in Old Age. Nat Med 2018, 24, 1246–1256. [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, J.L.; Tchkonia, T. Senolytic Drugs: From Discovery to Translation. J Intern Med 2020, 288, 518–536. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Shin, D.W. Senotherapeutics and Their Molecular Mechanism for Improving Aging. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2022, 30, 490–500. [CrossRef]

- Senolytics and Senomorphics: Natural and Synthetic Therapeutics in the Treatment of Aging and Chronic Diseases - ScienceDirect Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0891584921002847 (accessed on 13 July 2024).

- Lagoumtzi, S.M.; Chondrogianni, N. Senolytics and Senomorphics: Natural and Synthetic Therapeutics in the Treatment of Aging and Chronic Diseases. Free Radic Biol Med 2021, 171, 169–190. [CrossRef]

- Birch, J.; Gil, J. Senescence and the SASP: Many Therapeutic Avenues. Genes Dev 2020, 34, 1565–1576. [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, J.L. Translating the Science of Aging into Therapeutic Interventions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2016, 6, a025908. [CrossRef]

- Yousefzadeh, M.J.; Zhu, Y.; McGowan, S.J.; Angelini, L.; Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg, H.; Xu, M.; Ling, Y.Y.; Melos, K.I.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Inman, C.L.; et al. Fisetin Is a Senotherapeutic That Extends Health and Lifespan. EBioMedicine 2018, 36, 18–28. [CrossRef]

- Zoico, E.; Nori, N.; Darra, E.; Tebon, M.; Rizzatti, V.; Policastro, G.; De Caro, A.; Rossi, A.P.; Fantin, F.; Zamboni, M. Senolytic Effects of Quercetin in an in Vitro Model of Pre-Adipocytes and Adipocytes Induced Senescence. Scientific Reports | 123AD, 11, 23237. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H. V; Tran, D.T.; Rebuffatti, M.N.; Li, C.-S.; Knowlton, A.A. Investigation of Quercetin and Hyperoside as Senolytics in Adult Human Endothelial Cells. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Sharma, A.; Kumari, A.; Gulati, A.; Padwad, Y.; Sharma, R. Epigallocatechin Gallate Suppresses Premature Senescence of Preadipocytes by Inhibition of PI3K/Akt/MTOR Pathway and Induces Senescent Cell Death by Regulation of Bax/Bcl-2 Pathway. Biogerontology 2019, 20, 171–189. [CrossRef]

- Lammermann, I.; Terlecki-Zaniewicz, L.; Weinmullner, R.; Schosserer, M.; Dellago, H.; de Matos Branco, A.D.; Autheried, D.; Sevcnikar, B.; Kleissl, L.; Berlin, I.; et al. Blocking Negative Effects of Senescence in Human Skin Fibroblasts with a Plant Extract. NPJ Aging Mech Dis 2018, 4, 4. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, J.K.; Shankar, E.; Gupta, S. Chamomile: A Herbal Medicine of the Past with a Bright Future (Review). Mol Med Rep 2010, 3, 895–901. [CrossRef]

- Singh, O.; Khanam, Z.; Misra, N.; Srivastava, M.K. Chamomile (Matricaria Chamomilla L.): An Overview. Pharmacogn Rev 2011, 5, 82–95. [CrossRef]

- Mihyaoui, A. El; Esteves Da Silva, J.C.G.; Charfi, S.; Castillo, M.E.C.; Lamarti, A.; Arnao, M.B. Chamomile (Matricaria Chamomilla L.): A Review of Ethnomedicinal Use, Phytochemistry and Pharmacological Uses. Life 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Avonto, C.; Rua, D.; Lasonkar, P.B.; Chittiboyina, A.G.; Khan, I.A. Identification of a Compound Isolated from German Chamomile (Matricaria Chamomilla) with Dermal Sensitization Potential. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2017, 318, 16–22. [CrossRef]

- McKay, D.L.; Blumberg, J.B. A Review of the Bioactivity and Potential Health Benefits of Chamomile Tea (Matricaria Recutita L.). Phytotherapy Research 2006, 20, 519–530. [CrossRef]

- De Cicco, P.; Ercolano, G.; Sirignano, C.; Rubino, V.; Rigano, D.; Ianaro, A.; Formisano, C. Chamomile Essential Oils Exert Anti-Inflammatory Effects Involving Human and Murine Macrophages: Evidence to Support a Therapeutic Action. J Ethnopharmacol 2023, 311, 116391. [CrossRef]

- Shevchuk, Y.; Kuypers, K.; Janssens, G.E. Fungi as a Source of Bioactive Molecules for the Development of Longevity Medicines. Ageing Res Rev 2023, 87, 101929. [CrossRef]

- Kühnel, H.; Pasztorek, M.; Kuten-Pella, O.; Kramer, K.; Bauer, C.; Lacza, Z.; Nehrer, S. Effects of Blood-Derived Products on Cellular Senescence and Inflammatory Response: A Study on Skin Rejuvenation. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2024, 46, 1865–1885. [CrossRef]

- Varesi, A.; Chirumbolo, S.; Irene Maria Campagnoli, L.; Pierella, E.; Bavestrello Piccini, G.; Carrara, A.; Ricevuti, G.; Scassellati, C.; Bonvicini, C.; Pascale, A. The Role of Antioxidants in the Interplay between Oxidative Stress and Senescence. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kuhnel, H.; Adilijiang, A.; Dadak, A.; Wieser, M.; Upur, H.; Stolze, K.; Grillari, J.; Strasser, A. Investigations into Cytotoxic Effects of the Herbal Preparation Abnormal Savda Munziq. Chin J Integr Med 2015. [CrossRef]

- Petrova, N. V; Velichko, A.K.; Razin, S. V; Kantidze, O.L. Small Molecule Compounds That Induce Cellular Senescence. Aging Cell 2016, 15, 999–1017. [CrossRef]

- Odeh, A.; Dronina, M.; Domankevich, V.; Shams, I.; Manov, I. Downregulation of the Inflammatory Network in Senescent Fibroblasts and Aging Tissues of the Long-Lived and Cancer-Resistant Subterranean Wild Rodent, Spalax. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13045. [CrossRef]

- Bientinesi, E.; Lulli, M.; Becatti, M.; Ristori, S.; Margheri, F.; Monti, D. Doxorubicin-Induced Senescence in Normal Fibroblasts Promotes in Vitro Tumour Cell Growth and Invasiveness: The Role of Quercetin in Modulating These Processes. Mech Ageing Dev 2022, 206. [CrossRef]

- Lammermann, I.; Terlecki-Zaniewicz, L.; Weinmullner, R.; Schosserer, M.; Dellago, H.; de Matos Branco, A.D.; Autheried, D.; Sevcnikar, B.; Kleissl, L.; Berlin, I.; et al. Blocking Negative Effects of Senescence in Human Skin Fibroblasts with a Plant Extract. NPJ Aging Mech Dis 2018, 4, 4. [CrossRef]

- Matos, L.; Gouveia, A.M.; Almeida, H. Resveratrol Attenuates Copper-Induced Senescence by Improving Cellular Proteostasis. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 2017, 3793817. [CrossRef]

- Matos, L.; Gouveia, A.; Almeida, H. Copper Ability to Induce Premature Senescence in Human Fibroblasts. Age (Dordr) 2012, 34, 783–794. [CrossRef]

- Severino, J.; Allen, R.G.; Balin, S.; Balin, A.; Cristofalo, V.J. Is β-Galactosidase Staining a Marker of Senescence in Vitro and in Vivo? Exp Cell Res 2000, 257, 162–171. [CrossRef]

- Tayeh, Z.; Ofir, R. Asteriscus Graveolens Extract in Combination with Cisplatin/Etoposide/Doxorubicin Suppresses Lymphoma Cell Growth through Induction of Caspase-3 Dependent Apoptosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences Communication. [CrossRef]

- Kluska, M.; Wo´zniak, K.W. Molecular Sciences Natural Polyphenols as Modulators of Etoposide Anti-Cancer Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2021, 22, 6602. [CrossRef]

- Jamil, S.; Lam, I.; Majd, M.; Tsai, S.-H.; Duronio, V. Etoposide Induces Cell Death via Mitochondrial-Dependent Actions of P53. Cancer Cell Int 2015, 15, 79. [CrossRef]

- OyetakinWhite, P.; Tribout, H.; Baron, E. Protective Mechanisms of Green Tea Polyphenols in Skin. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2012, 2012, 560682. [CrossRef]

- Türkoğlu, M.; Uğurlu, T.; Gedik, G.; Yılmaz, A.M.; Süha Yalçin, A. In Vivo Evaluation of Black and Green Tea Dermal Products against UV Radiation. Drug Discov Ther 2010, 4, 362–367.

- Unno, K. Prevention of Brain Aging by Green Tea Components: Role of Catechins and Theanine. J Phys Fit Sports Med 2016, 5, 117–122. [CrossRef]

- Türkoğlu, M.; Uğurlu, T.; Gedik, G.; Yılmaz, A.M.; Süha Yalçin, A. In Vivo Evaluation of Black and Green Tea Dermal Products against UV Radiation. Drug Discov Ther 2010, 4, 362–367.

- Yamamoto, T.; Lewis, J.; Wataha, J.; Dickinson, D.; Singh, B.; Bollag, W.B.; Ueta, E.; Osaki, T.; Athar, M.; Schuster, G.; et al. Roles of Catalase and Hydrogen Peroxide in Green Tea Polyphenol-Induced Chemopreventive Effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2004, 308, 317–323. [CrossRef]

- Bientinesi, E.; Ristori, S.; Lulli, M.; Monti, D. Quercetin Induces Senolysis of Doxorubicin-Induced Senescent Fibroblasts by Reducing Autophagy, Preventing Their pro-Tumour Effect on Osteosarcoma Cells. Mech Ageing Dev 2024, 220, 111957. [CrossRef]

- Russo, C.; Edwards, K.D.; Margetts, G.; Kleidonas, S.; Zaibi, N.S.; Clapham, J.C.; Zaibi, M.S. Effects of Salvia Officinalis L. and Chamaemelum Nobile (L.) Extracts on Inflammatory Responses in Two Models of Human Cells: Primary Subcutaneous Adipocytes and Neuroblastoma Cell Line (SK-N-SH). J Ethnopharmacol 2021, 268, 113614. [CrossRef]

- Sagiv, A.; Burton, D.G.A.; Moshayev, Z.; Vadai, E.; Wensveen, F.; Ben-Dor, S.; Golani, O.; Polic, B.; Krizhanovsky, V. NKG2D Ligands Mediate Immunosurveillance of Senescent Cells. Aging 2016, 8, 328–344. [CrossRef]

- Chinta, S.J.; Woods, G.; Demaria, M.; Rane, A.; Zou, Y.; McQuade, A.; Rajagopalan, S.; Limbad, C.; Madden, D.T.; Campisi, J.; et al. Cellular Senescence Is Induced by the Environmental Neurotoxin Paraquat and Contributes to Neuropathology Linked to Parkinson’s Disease. Cell Rep 2018, 22, 930–940. [CrossRef]

- Velichutina, I.; Shaknovich, R.; Geng, H.; Johnson, N.A.; Gascoyne, R.D.; Melnick, A.M.; Elemento, O. EZH2-Mediated Epigenetic Silencing in Germinal Center B Cells Contributes to Proliferation and Lymphomagenesis. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Cappellano, G.; Ploner, C.; Lobenwein, S.; Sopper, S.; Hoertnagl, P.; Mayerl, C.; Wick, N.; Pierer, G.; Wick, G.; Wolfram, D. Immunophenotypic Characterization of Human T Cells after in Vitro Exposure to Different Silicone Breast Implant Surfaces. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.-F.; Hu, T.-L.; Soutto, M.; Belkhiri, A.; El-Rifai, W. Glutathione Peroxidase 7 Suppresses Bile Salt-Induced Expression of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in Barrett’s Carcinogenesis. J Cancer 2014, 5, 510–517. [CrossRef]

- Terlecki-Zaniewicz, L.; Lämmermann, I.; Latreille, J.; Bobbili, M.R.; Pils, V.; Schosserer, M.; Weinmüllner, R.; Dellago, H.; Skalicky, S.; Pum, D.; et al. Small Extracellular Vesicles and Their MiRNA Cargo Are Anti-Apoptotic Members of the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype. Aging 2018, 10, 1103–1132. [CrossRef]

- Chhunchha, B.; Fatma, N.; Kubo, E.; Singh, D.P.; Singh, D.P. Aberrant Sumoylation Signaling Evoked by Reactive Oxygen Species Impairs Protective Function of Prdx6 by Destabilization and Repression of Its Transcription. [CrossRef]

- Seliger, B.; Jasinski-Bergner, S.; Quandt, D.; Stoehr, C.; Bukur, J.; Wach, S.; Legal, W.; Taubert, H.; Wullich, B.; Hartmann, A. HLA-E Expression and Its Clinical Relevance in Human Renal Cell Carcinoma; Vol. 7;

| Chamomile | Goldenrod | Reishi | Green tea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (Y) | 1719 µg/ml | 841,6 µg/ml | Not stable | 250,1 µg/ml |

| IC50 (O) | 533,8 µg/ml | 530,5 µg/ml | 38,5 µg/ml | 91,97 µg/ml |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).