1. Introduction

Protective coatings have proven effective in extending the lifespan of metallic structures and various parts used in multiple sectors including automation, with the recent trend to employ aluminium due to its fuel economy benefits [

1]. Examples of these coatings include paints, organic and inorganic coatings, diffusion layers, metallic coatings applied via thermal spray, and galvanization [

2]. Thermal spray is a highly versatile technology suitable for a wide range of applications and components. It is effective against wear, corrosion, and harsh high-temperature environments, and it enhances thermal efficiency, such as through insulation in aluminium engine cylinders [

3]. Additionally, it is ideal for the repair and restoration of components [

4].

Within the thermal spray techniques, several processes are noteworthy, including cold spray [

4], HVOF, twin wire arc spraying, powder or detonation flame spraying, atmospheric plasma spraying, and arc spraying [

5]. These methods differ in their application techniques such as the form of feedstock, material generation and transport medium velocity, transport medium temperature, and the unique properties they impart.

Among the advanced thermal spray techniques, HVOF technology stands out. This innovative method employs a combustion system with high-pressure fuel and oxidizer gases to induce detonation within the combustion chamber. This process partially or fully melts the material, accelerating it to adhere effectively to the substrate. The result is a high-velocity fluid haze with temperatures reaching up to 3000 ºC and supersonic speeds ranging between 400 and 1.000 m/s [

6,

7]. By optimizing parameters such as the fuel and oxygen flow rate, powder feed rate, spray distance, and carrier gas flow rate, it is possible to produce compact coatings with excellent resistance to abrasion, heat, friction, and wear [

8,

9,

10]. Notably, thermal sprayed coating with a thickness of just 1 mm can achieve hardness values up to 2000 HV [

11].

Compared to other thermal spray processes, HVOF coatings offer superior surface quality [

12]. Additionally, when compared to other high-performance techniques like Atmospheric Plasma Spraying (APS), HVOF reduces the thermal degradation of the material [

13].

Regarding the parameters, porosity which influences corrosion alongside nanocrystalline amorphous phases, and the hardness of the coating, will depend on the oxygen flow rate followed by powder feed rate and spray distance [

12]. On the other hand, phase degradation, deposition efficiency, and bonding strength will also be affected principally by the spray distance [

8]. Additionally, the angle of incidence impacts the final properties; higher preheating and a lower angle of incidence enhance the corrosion resistance of coatings [

14]. Also, gun speed can be important in the final properties of the coating. Faster gun movement reduces torch dwell time, spraying less powder and lowering the coating temperature [

15].

Certain studies have reported the application of HVOF techniques on aluminium alloy substrates [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], using ceramic materials such as carbides and oxides as the primary coating material due to their high melting points. In some cases, carbides and oxides are combined with metals like Co, Ni, and Cr to achieve low oxygen content and excellent adhesion properties [

22].

In one study [

23], WC10Co4C coating on an aluminium substrate resulted in reduced mechanical properties. Additionally, during friction tests, the carbide particles caused abrasion and fragmentation of the coating layers. The refinement of the microstructure, influenced by the feedstock powders, and the reduction of porosity, led to an increase in hardness from 68 HV up to 920HV in the Cr

3C

2 thermal spray coating on the Al-Si substrate [

24]. Another study [

25] demonstrated that an alumina coating up to 150 µm thick over an A6061 alloy resulted in hardness values ten times higher than the base. During the friction test with an alumina ball as the counter face, the substrate exhibited an abrasion wear mechanism and secondary adhesion, causing severe plastic deformation and delamination while the coating layer showed some cracks but not scratches or grooves characteristics of abrasion wear. On AlZn5.5MgCu aluminium alloy, AlCuFe quasicrystal was deposited as a coating [

26] with the new materials showing friction coefficient values between 0.92 and 1.00. For A390 aluminium alloys, Al

2O

3 coating showed lower adhesion and unstable friction behaviour, with a dynamic coefficient of friction of 0.8, compared to WC-based coating with a coefficient of friction of around 0.6. Hardness values exceeded 1000 HV for WC-based coatings, while Al

2O

3-base coating reached 315 HV. Abrasion and adhesion wear mechanisms were observed in all cases [

27]. Combining Al

2O

3 with Y

2O

3 and TiO

2 in coatings has been reported to further enhance wear properties [

28].

Some studies have explored aluminium-based coating on aluminium substrates, but there is limited information on the wear characteristics of ceramic and metallic coating on aluminium alloys. However, it has been demonstrated that metals such as aluminium are also beneficial for coating technologies, creating new demands for surface pre-treatment coatings for corrosion protection and paint adhesion in the automotive sector [

29]. A notable recent development is the Alcoat project, which focuses on creating a new recycled aluminium coating for steel products [

30].

A current trend and emerging opportunity that has garnered significant research attention over the past decade is the production of High Entropy Alloys (HEAs), also known as compositional complex alloys (CCAs) and multicomponent alloys [

31]. The distinctiveness of these new alloys lies in their substantial improvement in mechanical properties. One of the fundamental concepts is to achieve a more disordered structure with five or more elements at or near equimolar composition, forming a solid solution phase, in contrast to conventional alloys, which are based on the central areas of phase diagrams [

32]. Despite these new opportunities and their excellent mechanical properties [

33,

34], the large-scale production of Light High Entropy Alloys (LWHEAs) is limited, with vacuum die casting being the primary manufacturing process [

35]. In some special cases, the investigated alloys include expensive elements such as Ag, which increases hardness and yield strength by more than 10% and elongation by 21% [

36], or Nb [

37]. However, the addition of these elements results in non-cost-effective alloys. Recently, it has been reported that rapid solidification processes can enhance the single-phase microstructures in these alloys and the absence of dendrite microstructure [

38], although, in some instances, this requirement is not met, resulting predominantly in intermetallic phases [

39]. New studies have demonstrated that, despite the limited understanding of intermetallic in HEA alloys, they can act as very effective second phases [

40].

The development of multi-component materials based on aluminium alloys holds promise. Aluminium matrix composite brake drums and rotors have been used in vehicles such as the Lotus Elise, Volkswagen Lupo 3L, Chrysler Plymouth Prowler, and General Motors EV-1 due to their thermal and wear properties [

41].

The use of HVOF technology is limited due to economic reasons, stemming from relatively expensive equipment and operational costs, particularly for powders [

42]. From this perspective, employing secondary aluminium alloys for thermal spray powders could yield cost-effective results.

In this research, a new thermal spray process combining HVOF and plasma technologies is employed. This new device utilizes a thermal plasma to enhance the combustion process within the HVOF spray torch and incorporates an auxiliary cold gas to assist in controlling the process temperature. The use of thermal plasma to assist combustion aims to increase the flexibility of the spray system in terms of operating parameters and the range of materials that can be sprayed [

43].

Additionally, the grain size of the coating influences the final mechanical properties. In this case, gas atomization has been selected as the method to convert a new multicomponent cast alloy into powder. This process provides grain sizes ranging from 10 µm to 150 µm [

44]. Moreover, the alloy has been manufactured using the High-Pressure Die-Casting (HPDC) process, which also produces smaller grain sizes that are favourable for atomization [

45].

It is noteworthy that due to oxidation, accelerated by process temperatures, these coatings can serve as effective thermal barrier coatings for components exposed to hot gases. This characteristic renders them suitable not only for transportation applications but also for hydrogen utilization.

4. Discussion

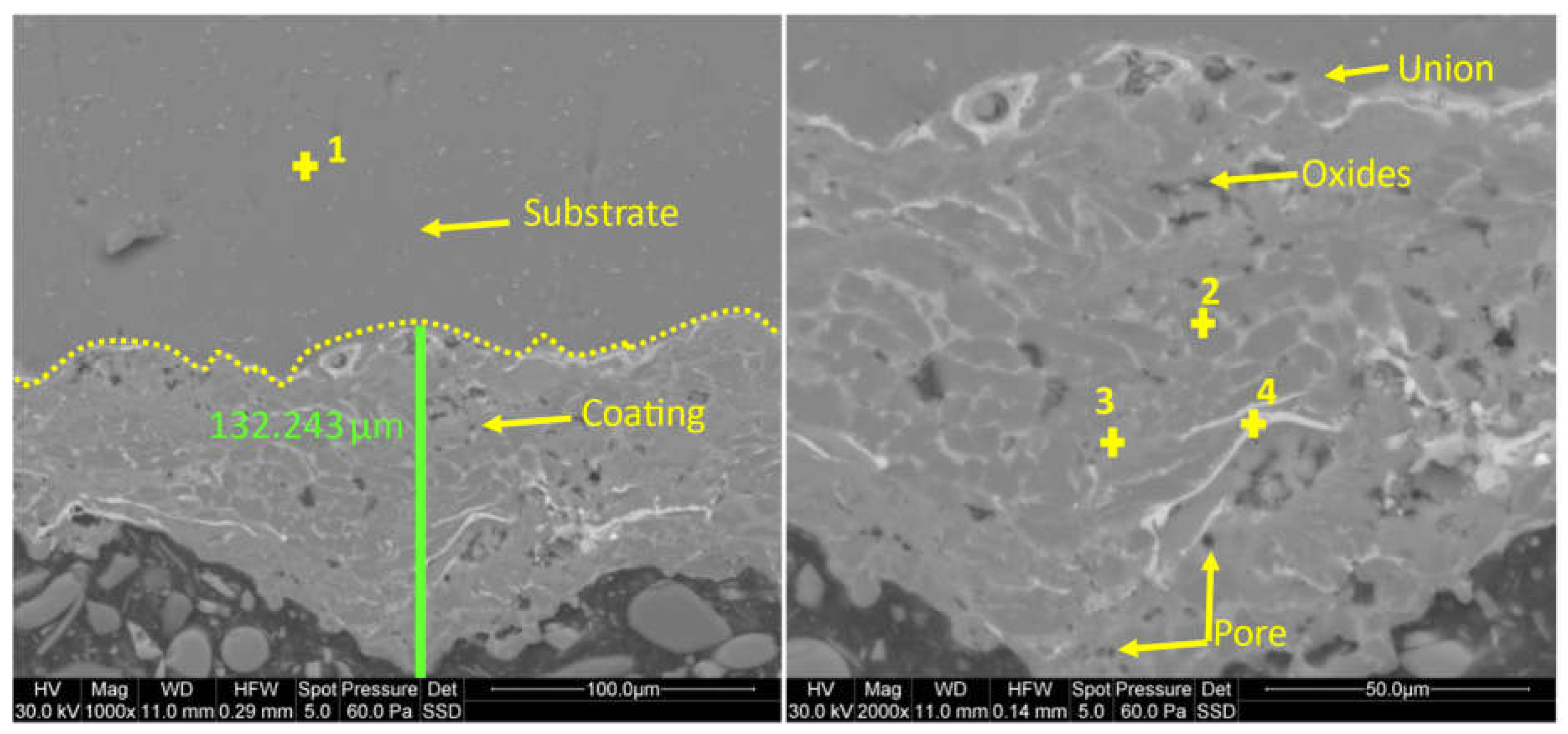

It has been demonstrated that using new multicomponent Al80Mg10Si5Cu5 aluminium alloys as a coating material for aluminium alloys improves mechanical, electrical, and tribological properties. Additionally, there was a slight improvement in corrosion resistance. The newly designed HVOAF process provided a high-quality coating with a thickness of up to 130 µm, though some pores were presented at the bottom of the coating, accounting for less than 2% of the area. These pores are characteristic of this process. This thermal process requires experienced handling and optimization of parameters to achieve consistent coating quality. Parameters such as oxygen flow rate, spray distance, and powder feed rate can be optimized to improve porosity and coating thickness.

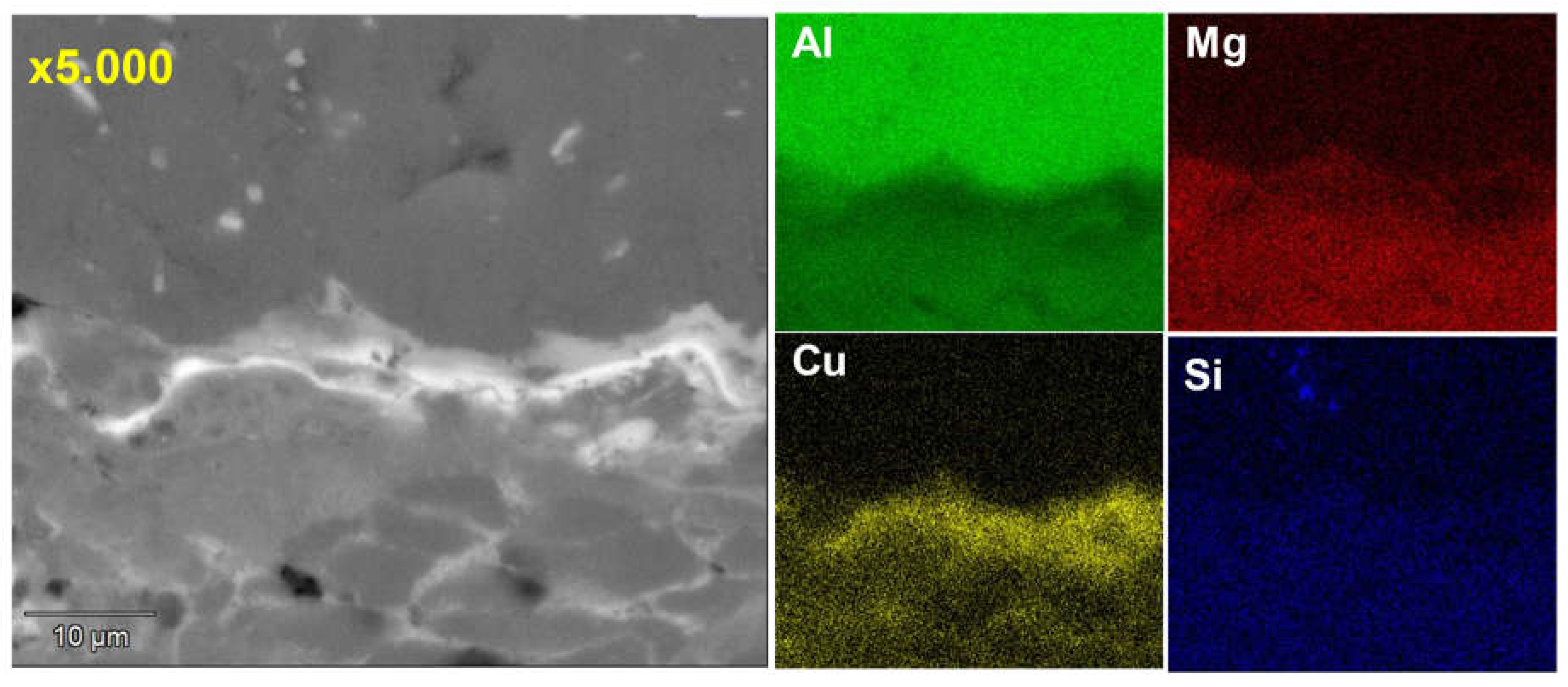

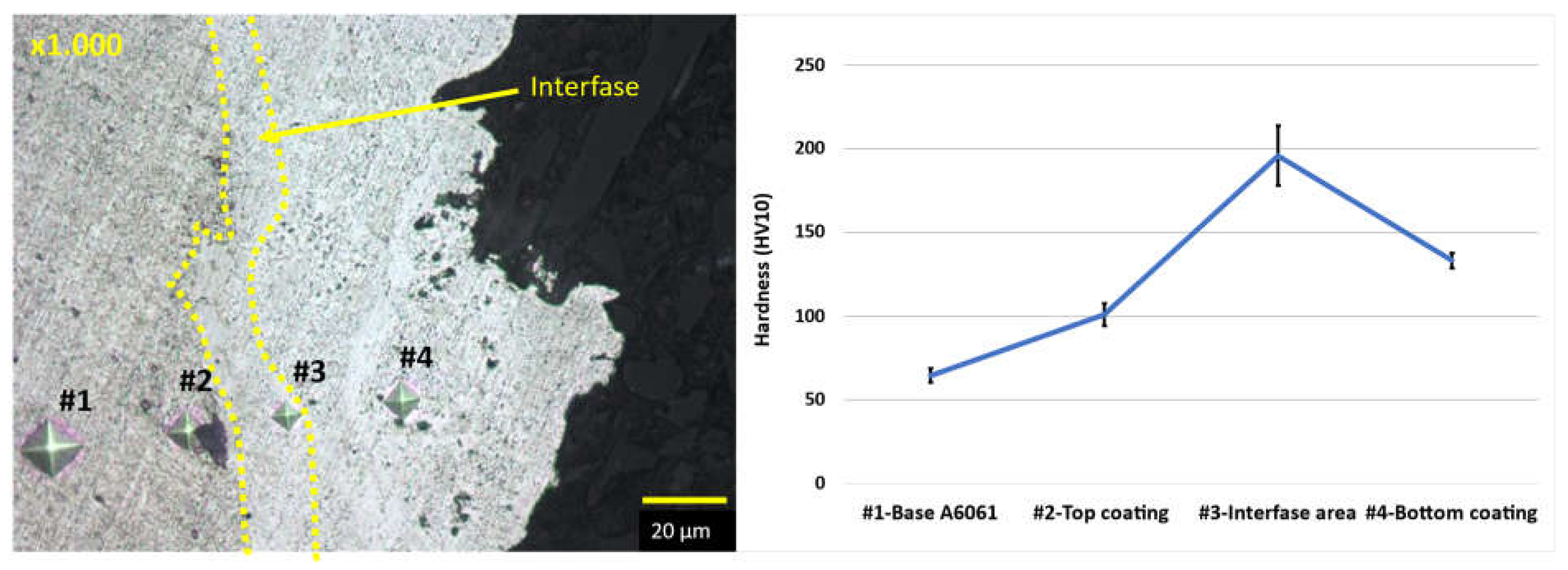

Microstructure and chemical analysis results indicated good adhesion between the substrate and the coating. The high solidification rates led to fewer phases and a finer microstructure, resulting in the disappearance of the Al2Cu phase and the precipitation of Mg2Si throughout the matrix. In the interface area, a high presence of elemental copper precipitated as the Al2CuMg phase, providing high hardness without cracking.

Hardness results demonstrated a 50% increase in the new multicomponent-based coated material compared to the A6061 substrate alloy, reaching values up to 220 HV.

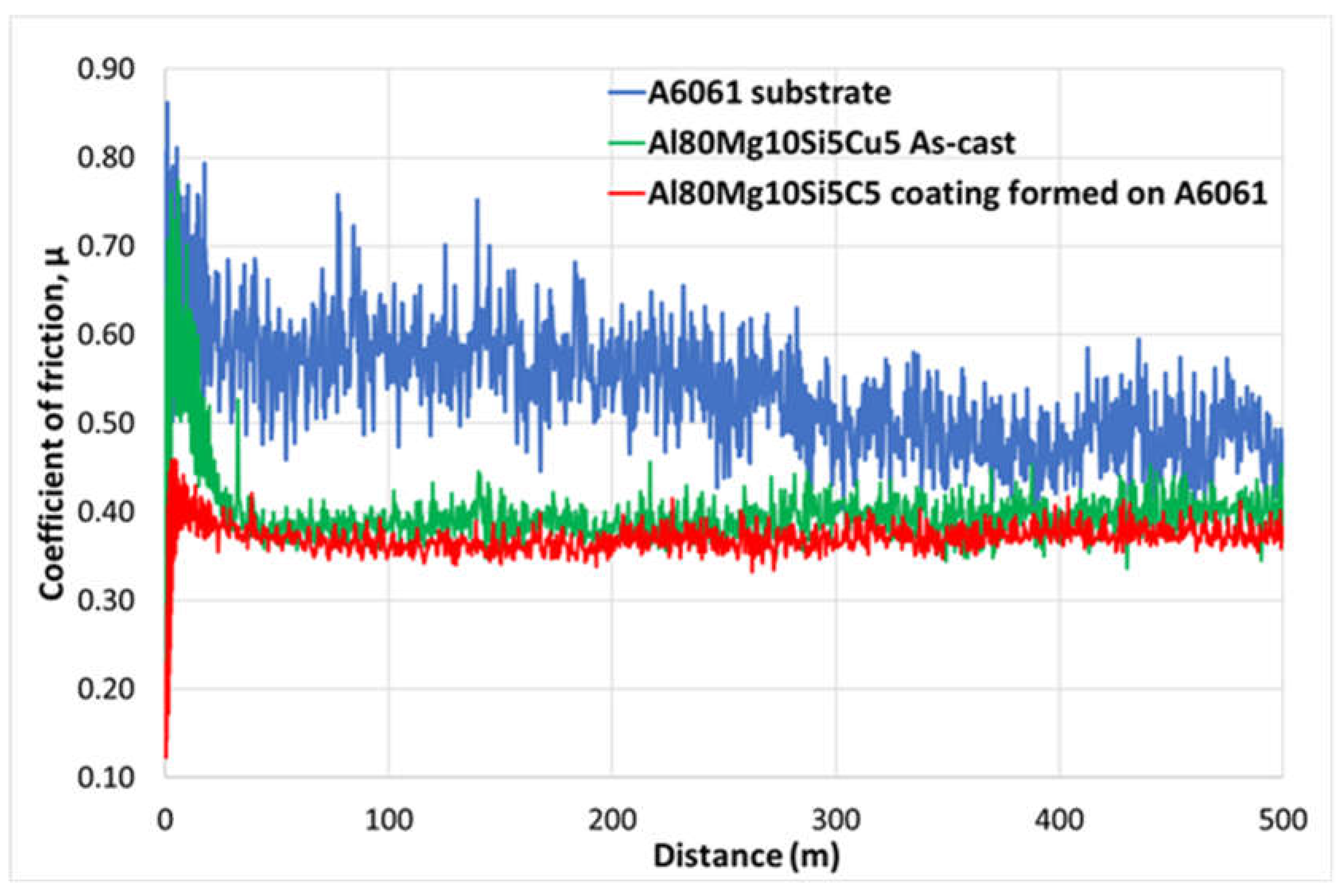

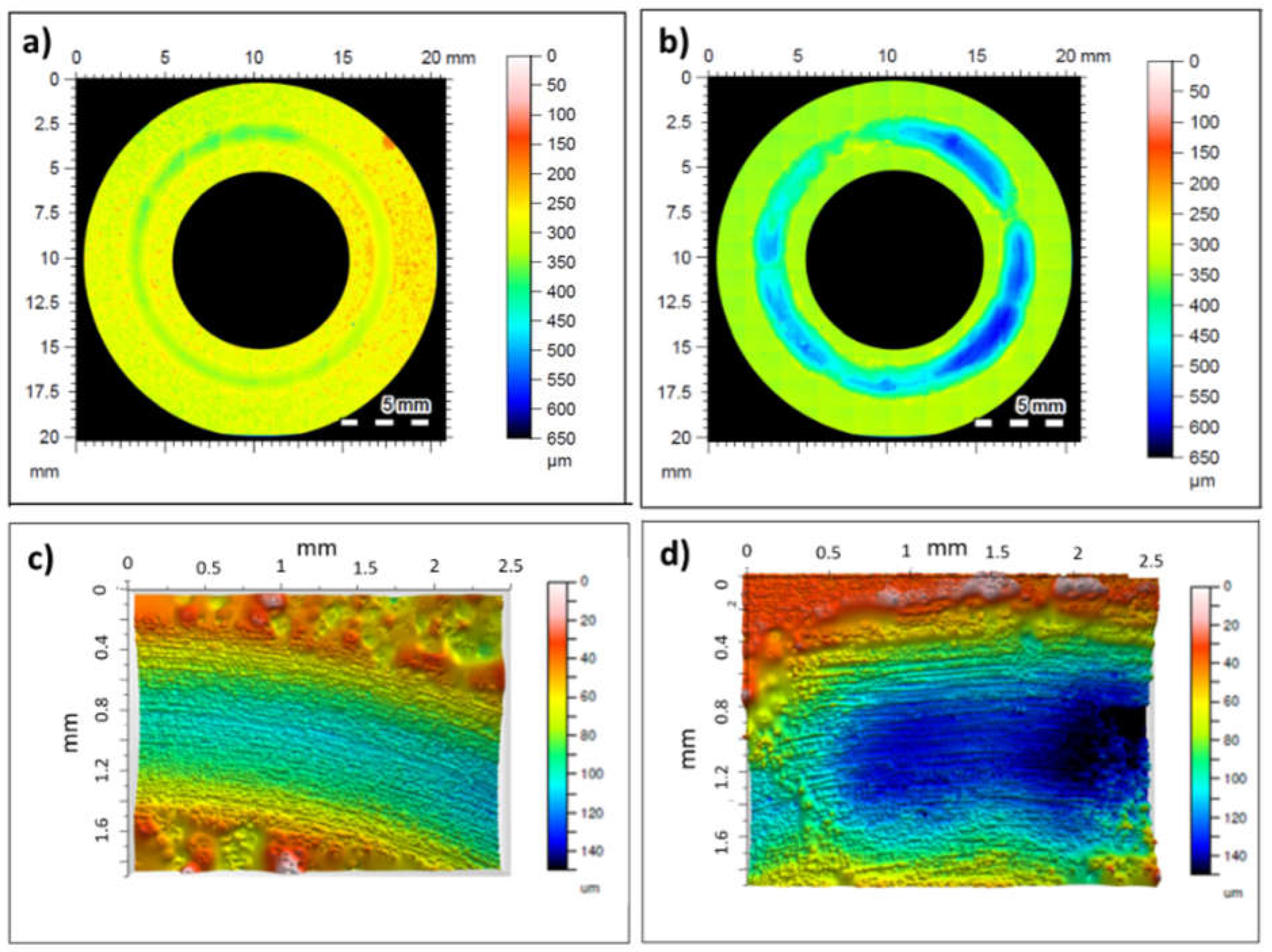

Tribological property results showed that the friction coefficient decreased by more than 20% in the new multicomponent alloy-based coated material compared to the A6061 substrate alloy, achieving a steady-state friction coefficient value of 0.40. This value was similar to that observed for the new multicomponent alloy in its as-cast state. Additionally, the wear coefficient also decreased significantly, approximately 2.5 times lower than that of the uncoated sample.

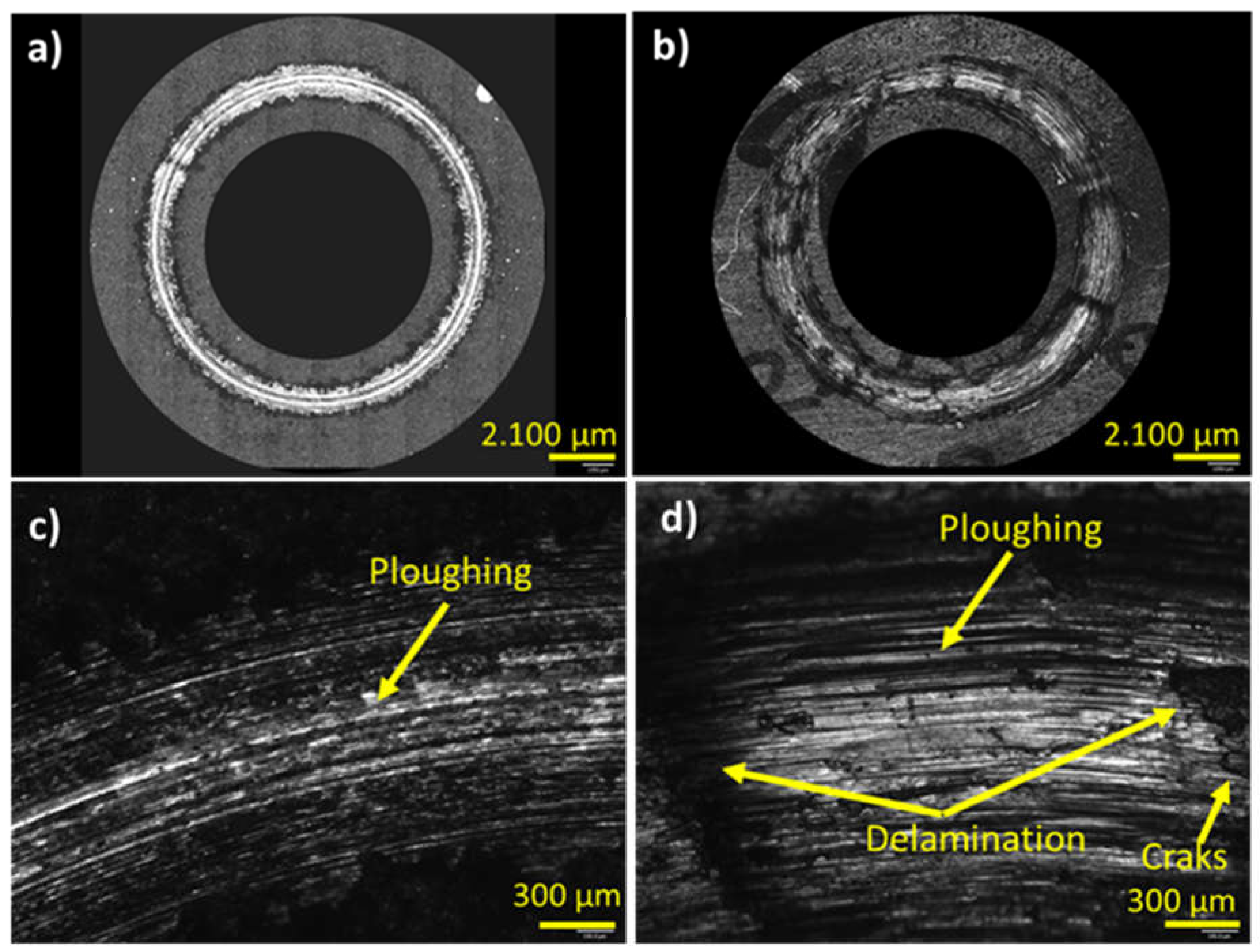

The wear rate coefficient and examination of the microstructure of the wear track surface and cross-sectional surface in the new coated material indicated mild wear conditions characterized by abrasion as the principal wear mechanism. In contrast, the substrate without the coating exhibited moderate to severe wear, showing delaminated areas alongside ploughed areas attributed to a combination of abrasion and delamination mechanisms.

Comparing the hardness values of the experimental alloys revealed that samples with higher hardness demonstrated a lower coefficient of friction during the sliding process. Additionally, it was observed that samples with significantly higher values for the coefficient of friction corresponded to the highest wear rate. However, it was noted that samples with a similar coefficient of friction did not necessarily exhibit a linear relation with the wear rate.

The electrical conductivity results showed a significant improvement (x3.3 times) compared to the multicomponent alloy in its as-cast state. The conductivity values approached those of the A6061 substrate and were comparable to pure aluminum alloy. The analysis demonstrated a strong influence of the cooling rate and morphology of the constituents on electrical conductivity.

Corrosion resistance results demonstrated that the multicomponent alloy had higher values compared to other conventional and multicomponent aluminum alloys and were also higher than those of heat treated A6061 alloy. However, they were higher than the values for A6061 alloy in its as-cast state. Parameters such as preheating, and angle of incidence should be investigated to further increase the corrosion resistance of the coating.

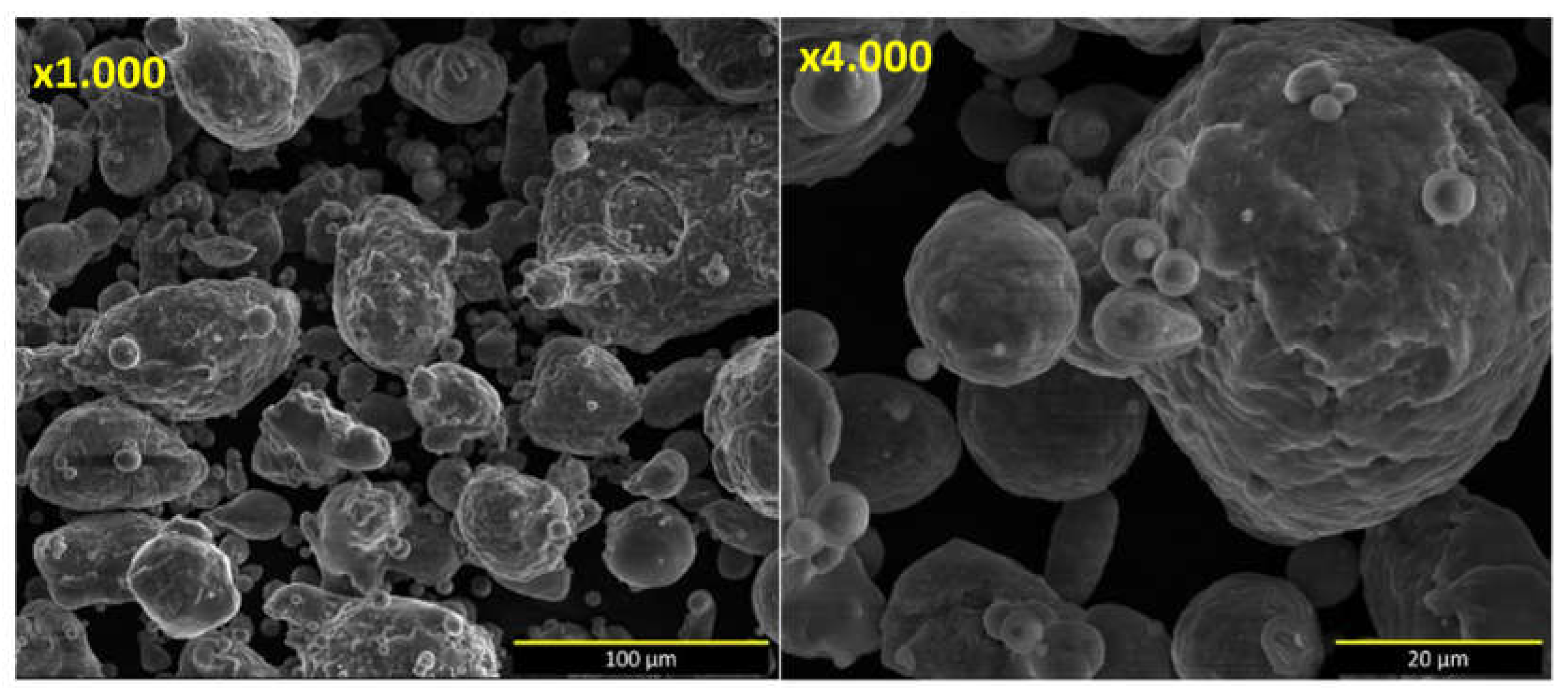

Figure 1.

SEM image of microstructure of Al80Mg10Si5Cu5 powder at x1.000 and x4.000 magnifications.

Figure 1.

SEM image of microstructure of Al80Mg10Si5Cu5 powder at x1.000 and x4.000 magnifications.

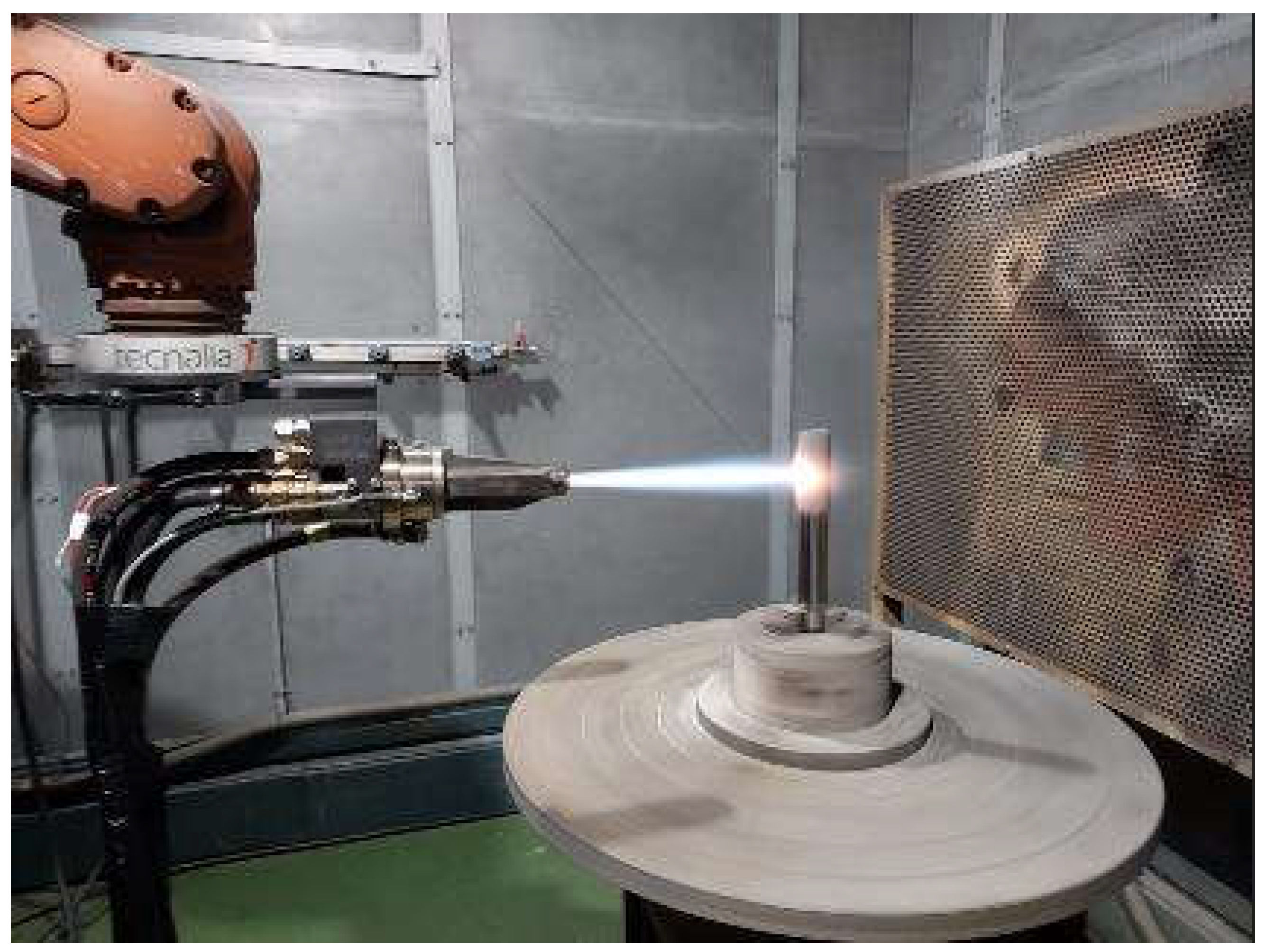

Figure 2.

Plasma projecting with the robot.

Figure 2.

Plasma projecting with the robot.

Figure 3.

SEM micrographics of the new multicomponent-based coating at the magnification of x1.000 and x2.000.

Figure 3.

SEM micrographics of the new multicomponent-based coating at the magnification of x1.000 and x2.000.

Figure 4.

Line scan EDS analysis showing the distribution of each element across the different alloys and interface.

Figure 4.

Line scan EDS analysis showing the distribution of each element across the different alloys and interface.

Figure 5.

EDS map of element distribution in the alloys and interface.

Figure 5.

EDS map of element distribution in the alloys and interface.

Figure 6.

OM image showing indentations of a sample at the magnification of x1.000 and hardness graph.

Figure 6.

OM image showing indentations of a sample at the magnification of x1.000 and hardness graph.

Figure 7.

Evolution of the coefficient of friction for the experimental alloys: A6061 with and without the coating, and multicomponent Al80Mg10SiCu5 in as-cast state.

Figure 7.

Evolution of the coefficient of friction for the experimental alloys: A6061 with and without the coating, and multicomponent Al80Mg10SiCu5 in as-cast state.

Figure 8.

Wearing surface topographies. a) 3D profile of A6061 with the coating, b) 3D profile of A6061 without the coating, c) 2D profile of A6061 with the coating, d) 2D profile of A6061 without the coating.

Figure 8.

Wearing surface topographies. a) 3D profile of A6061 with the coating, b) 3D profile of A6061 without the coating, c) 2D profile of A6061 with the coating, d) 2D profile of A6061 without the coating.

Figure 9.

Laser confocal imagen of wear track at low magnification a) A6061 with the coating, b) A6061 without the coating; at high magnification c) A6061 with the coating, d) A6061 without the coating.

Figure 9.

Laser confocal imagen of wear track at low magnification a) A6061 with the coating, b) A6061 without the coating; at high magnification c) A6061 with the coating, d) A6061 without the coating.

Figure 10.

Laser confocal imagen of the cross-sectional microstructure, a) A6061 with the coating at low magnification, c) at high magnification; b) A6061 without the coating at low magnification d) at high magnification.

Figure 10.

Laser confocal imagen of the cross-sectional microstructure, a) A6061 with the coating at low magnification, c) at high magnification; b) A6061 without the coating at low magnification d) at high magnification.

Figure 11.

Comparison of microstructures in the Al80Mg10Si5Cu5 multicomponent alloy at different cooling rates.

Figure 11.

Comparison of microstructures in the Al80Mg10Si5Cu5 multicomponent alloy at different cooling rates.

Figure 12.

Correlation of %IACS with solution components and cooling rates.

Figure 12.

Correlation of %IACS with solution components and cooling rates.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of experimental alloys in %wt.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of experimental alloys in %wt.

| Alloy |

Al |

Mg |

Si |

Cu |

Mn |

Fe |

Zn |

| Al80Mg10Si5Cu5 |

78.9 |

10.3 |

5.6 |

4.7 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

| A6061 |

98.2 |

0.9 |

- |

0.9 |

- |

- |

- |

Table 2.

Mechanical, electrical, and thermal properties of experimental alloys.

Table 2.

Mechanical, electrical, and thermal properties of experimental alloys.

| Alloy |

Hardness (HV3) |

Electrical conductivity (%IACS) |

Melting point (ºC) |

| Al80Mg10Si5Cu5 |

130 ± 13.01 |

17 ± 0.55 |

592 |

| A6061 |

68 ± 4.17 |

57 ± 0.41 |

585 |

Table 3.

Sliding wear test parameters.

Table 3.

Sliding wear test parameters.

| Test Parameters |

Selected Value |

| Load (N) |

15.0 |

| Velocity (m/s) |

0.1 |

| Rotation speed (rpm) |

127.3 |

| Sliding distance (m) |

500.0 |

| Track diameter (mm) |

15 |

| Environment |

Dry air |

Table 4.

Chemical composition (wt%) of new multicomponent-based coated material.

Table 4.

Chemical composition (wt%) of new multicomponent-based coated material.

| Point |

Al |

Mg |

Si |

Cu |

Mn |

Fe |

| 1 |

97.14 |

1.0 |

- |

1.30 |

|

0.6 |

| 2 |

82.8 |

7.9 |

5.5 |

3.6 |

0.4 |

|

| 3 |

78.6 |

8.1 |

5.9 |

6.8 |

0.2 |

0.5 |

| 4 |

68.9 |

6.5 |

4.8 |

25.4 |

|

0.4 |

Table 5.

Friction (µ) and Wear rate (K) coefficients.

Table 5.

Friction (µ) and Wear rate (K) coefficients.

| Sample |

µ |

K (mm3/N.m) |

| A6061 substrate |

0.52 ± 0.05 |

1.2 x 10 -3 ± 0.000223 |

| As-cast Al80Mg10Si5Cu5 |

0.40 ± 0.04 |

9.9 x 10 -4 ± 0.000191 |

| A6061 with the Al80Mg10Si5Cu5 coating |

0.40 ± 0.01 |

5.3 x 10 -4 ± 0.000019 |

Table 6.

Electrical conductivity (%IACS) of new coated A6061 alloy.

Table 6.

Electrical conductivity (%IACS) of new coated A6061 alloy.

| Alloy |

%IACS |

| A6061 with the Al80Mg10Si5Cu5 coating c |

56 ± 0.23 |

Table 7.

Results of corrosion of multicomponent Al80Mg10Si5Cu5 alloy, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy.

Table 7.

Results of corrosion of multicomponent Al80Mg10Si5Cu5 alloy, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy.

| OCP (V) |

Rs (Ω) |

Rc (Ω) |

Rp (Ω) |

Icor (µA/cm2) |

Rcor (mm/year) |

| -0.874 |

7.9 |

6,909 |

31,890 |

0.681 |

0.007 |

Table 8.

Results of corrosion of multicomponent Al80Mg10Si5Cu5 alloy, potentiodynamic polarization in the TAFEL region.

Table 8.

Results of corrosion of multicomponent Al80Mg10Si5Cu5 alloy, potentiodynamic polarization in the TAFEL region.

| Ecor (V) |

Rp (Ω) |

Icor (µA/cm2) |

Rcor (mm/year) |

| -0.743 |

154,600 |

0.118 |

0.001 |

Table 9.

Approx. Chemical composition (wt.%) of phases contained in Al80Mg10Si5Cu alloy.

Table 9.

Approx. Chemical composition (wt.%) of phases contained in Al80Mg10Si5Cu alloy.

| Phase |

Gravity Sand |

Gravity Die Cast |

HPDC |

Thermal spray |

| Primary Mg2Si |

32Mg, 33Al, 34Si, 1Cu |

34Mg, 31Al, 34Si, 1Cu |

30Mg, 42Al, 25Si, 3Cu |

- |

| Eutectic Mg2Si |

27Mg, 42Al, 29Si, 1Cu |

28Mg, 41Al, 30Si, 1Cu |

17Mg, 67Al, 14Si, 3Cu |

- |

| Aluminium |

93Al, 3Mg, 1Si, 2Cu |

93Al, 4Mg, 1Si, 2Cu |

88Al, 7Mg, 2Si, 3Cu |

84Al, 8Mg, 6Si, 3Cu |

| Al2Cu |

66Al, 34Cu |

66Al, 4Mg, 1Si, 29Cu |

66Al, 8Mg, 1Si, 24Cu |

- |

| Al2CuMg |

80Al, 15Mg, 1Si, 10Cu |

75Al, 12Mg, 2Si, 11Cu |

76Al, 11Mg, 2Si, 12Cu |

76Al, 6Mg, 4Si, 15Cu |