Submitted:

06 August 2024

Posted:

06 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Urine Samples

2.3. C. elegans Strain

2.4. Synchronization of Developmental Stages of C. elegans

2.5. Preparation of the Test Plates for Chemotactic Tests

2.6. Statistical Analysis

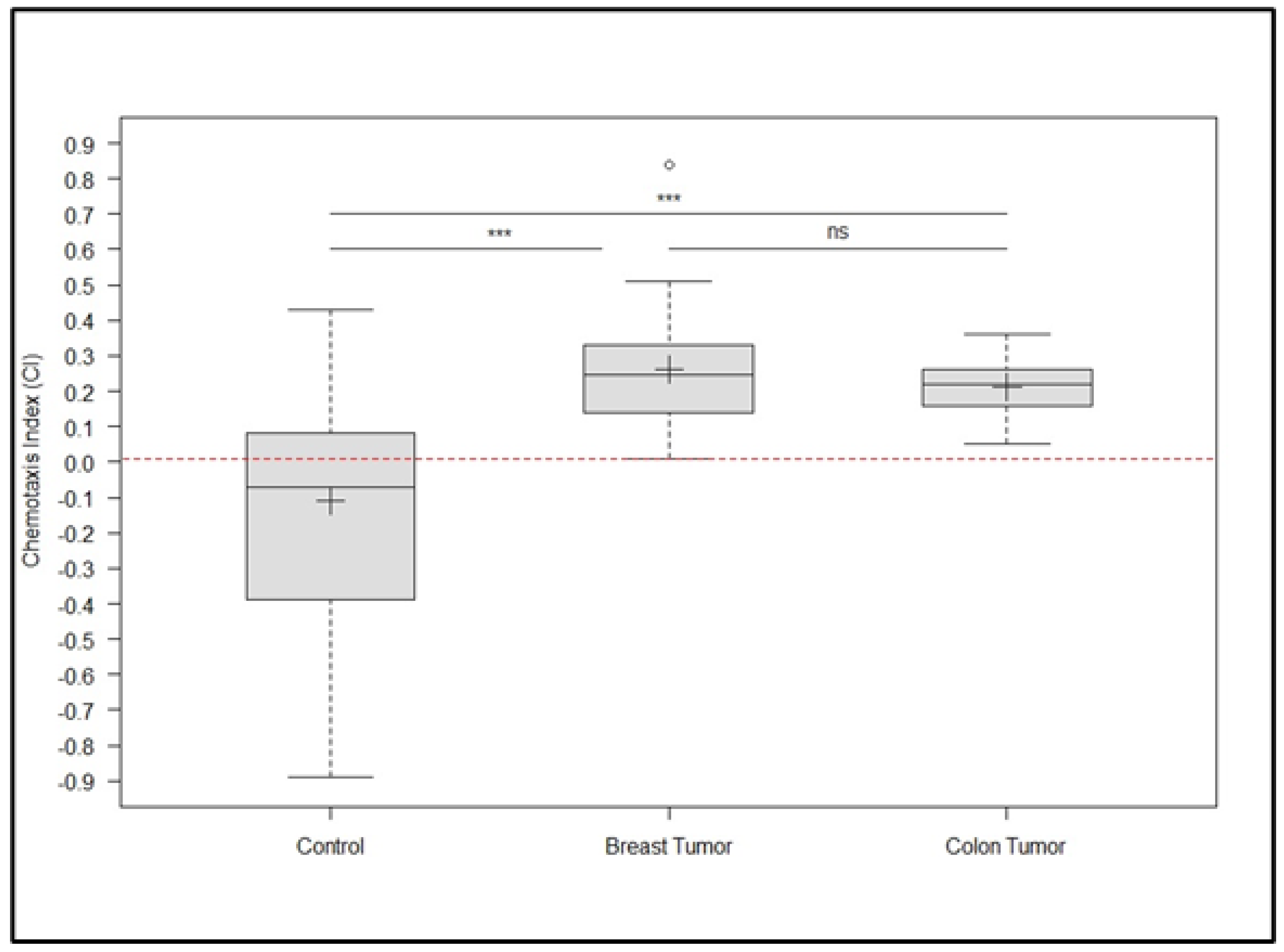

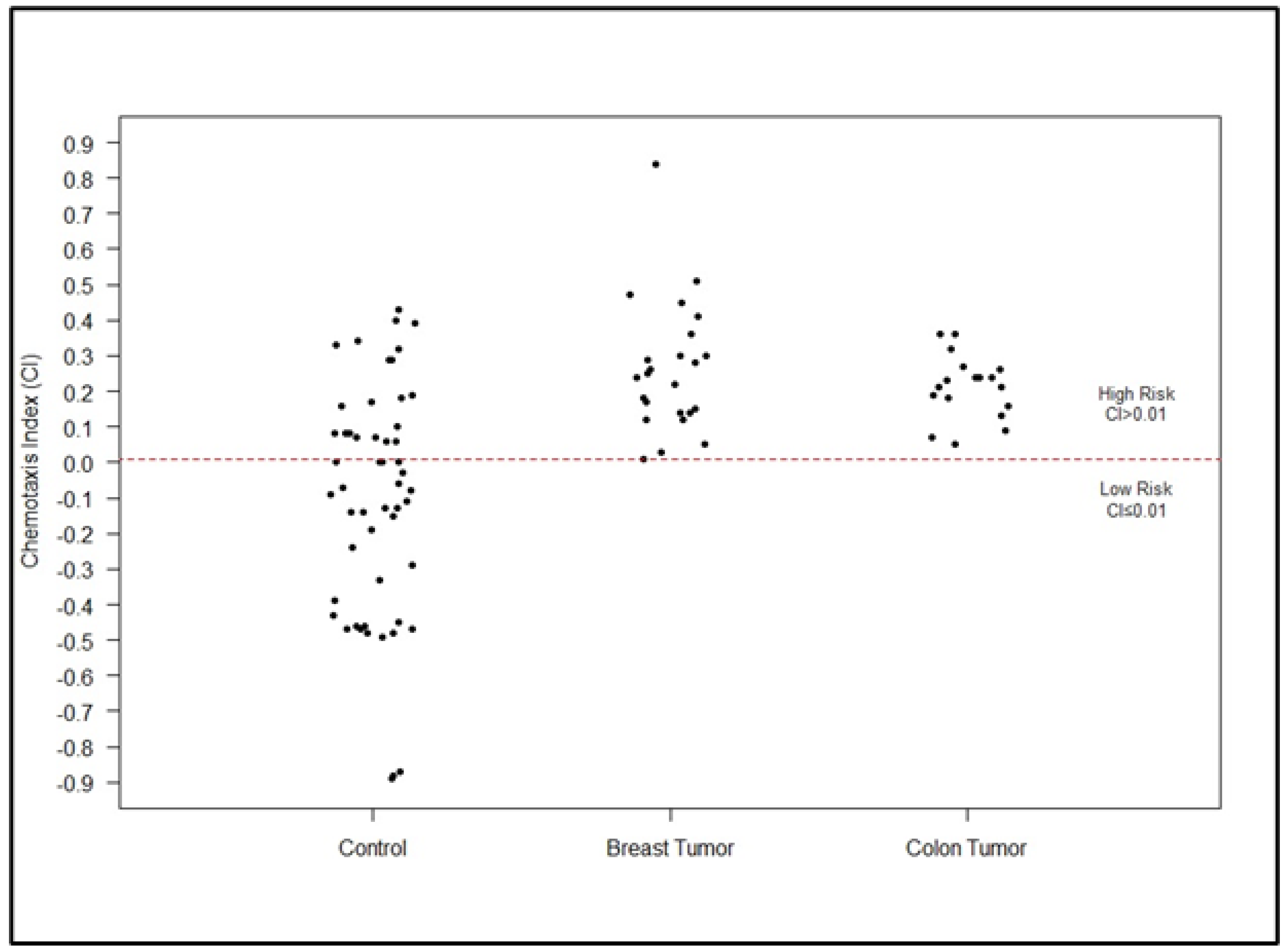

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brenner, S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 1974, 77, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium Genome Sequence of the Nematode C. elegans: A Platform for Investigating Biology. Science (80-. ) 1998, 282, 2012–2018. [CrossRef]

- Truong, L.-L.; Scott, L.; Pal, R.S.; Jalink, M.; Gunasekara, S.; Wijeratne, D.T. Cancer and cardiovascular disease: Can understanding the mechanisms of cardiovascular injury guide us to optimise care in cancer survivors? Ecancermedicalscience 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehlmann, T.; Kahraman, M.; Ludwig, N.; Backes, C.; Galata, V.; Keller, V.; Geffers, L.; Mercaldo, N.; Hornung, D.; Weis, T.; et al. Evaluating the Use of Circulating MicroRNA Profiles for Lung Cancer Detection in Symptomatic Patients. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinestrosa, J.P.; Kurzrock, R.; Lewis, J.M.; Schork, N.J.; Schroeder, G.; Kamat, A.M.; Lowy, A.M.; Eskander, R.N.; Perrera, O.; Searson, D.; et al. Early-stage multi-cancer detection using an extracellular vesicle protein-based blood test. Commun. Med. 2022, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamshidi, A.; Liu, M.C.; Klein, E.A.; Venn, O.; Hubbell, E.; Beausang, J.F.; Gross, S.; Melton, C.; Fields, A.P.; Liu, Q.; et al. Evaluation of cell-free DNA approaches for multi-cancer early detection. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 1537–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mencel, J.; Slater, S.; Cartwright, E.; Starling, N. The Role of ctDNA in Gastric Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, B.D.; Oke, J.; Virdee, P.S.; Harris, D.A.; O’Doherty, C.; Park, J.E.; Hamady, Z.; Sehgal, V.; Millar, A.; Medley, L.; et al. Multi-cancer early detection test in symptomatic patients referred for cancer investigation in England and Wales (SYMPLIFY): A large-scale, observational cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Yue, Y.; Zihan, R.; Youbin, C.; Tianyu, L.; Rui, W. Clinical application of liquid biopsy based on circulating tumor DNA in non-small cell lung cancer. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1200124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- di Luccio, E.; Morishita, M.; Hirotsu, T.C. elegans as a Powerful Tool for Cancer Screening. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M. These ‘supersniffer’ mice could one day detect land mines, diseases. Science (80-. ) 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Flores, H.; Apresa-García, T.; Garay-Villar, Ó.; Sánchez-Pérez, A.; Flores-Villegas, D.; Bandera-Calderón, A.; García-Palacios, R.; Rojas-Sánchez, T.; Romero-Morelos, P.; Sánchez-Albor, V.; et al. A non-invasive tool for detecting cervical cancer odor by trained scent dogs. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bargmann, C.I.; Horvitz, H.R. Chemosensory neurons with overlapping functions direct chemotaxis to multiple chemicals in C. elegans. Neuron 1991, 7, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bargmann, C.I. Chemosensation in C. elegans. WormBook 2006, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Q.; Boshier, P.; Myridakis, A.; Belluomo, I.; Hanna, G.B. Urinary Volatile Organic Compound Analysis for the Diagnosis of Cancer: A Systematic Literature Review and Quality Assessment. Metabolites 2020, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirotsu, T.; Sonoda, H.; Uozumi, T.; Shinden, Y.; Mimori, K.; Maehara, Y.; Ueda, N.; Hamakawa, M. A highly accurate inclusive cancer screening test using Caenorhabditis elegans scent detection. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusumoto, H.; Tashiro, K.; Shimaoka, S.; Tsukasa, K.; Baba, Y.; Furukawa, S.; Furukawa, J.; Niihara, T.; Hirotsu, T.; Uozumi, T. Efficiency of gastrointestinal cancer detection by nematode-NOSE (N-NOSE). In Vivo (Brooklyn). 2020, 34, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asai, A.; Konno, M.; Ozaki, M.; Kawamoto, K. Scent test using Caenorhabditis elegans to screen for early- stage pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget 2021, 12, 1687–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inaba, S.; Shimozono, N.; Yabuki, H.; Enomoto, M.; Morishita, M.; Hirotsu, T.; di Luccio, E. Accuracy evaluation of the C. elegans cancer test (N-NOSE) using a new combined method. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2021, 27, 100370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.; Feria, N.S.; Yoshioka, A.; Tu, E.; Civitci, F.; Estes, S.; Wagner, J.T. A Caenorhabditis elegans behavioral assay distinguishes early stage prostate cancer patient urine from controls. Biol. Open 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrow, M.; Olmedo, M. In situ Chemotaxis Assay in Caenorhabditis elegans (for the Study of Circadian Rhythms). BIO-PROTOCOL 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta-de-la-Riva, M.; Fontrodona, L.; Villanueva, A.; Cerón, J. Basic Caenorhabditis elegans Methods: Synchronization and Observation. J. Vis. Exp. 2012, e4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margie, O.; Palmer, C.; Chin-Sang, I.C. elegans Chemotaxis Assay. J. Vis. Exp. 2013, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yan, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, K.; Huang, X. The olfactory signal transduction for attractive odorants in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, N.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, D.; Yan, J.; Zou, W.; Zhang, K.; Huang, X. The signaling pathway of Caenorhabditis elegans mediates chemotaxis response to the attractant 2-heptanone in a Trojan Horse-like pathogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 23618–23627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S. Chemotaxis by the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: Identification of attractants and analysis of the response by use of mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1973, 70, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthy, S.E.; Haynes, L.; Chambers, M.; Bethune, D.; Kan, E.; Chung, K.; Ota, R.; Taylor, C.J.; Glater, E.E. Identification of attractive odorants released by preferred bacterial food found in the natural habitats of C. elegans. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queirós, L.; Marques, C.; Pereira, J.L.; Gonçalves, F.J.M.; Aschner, M.; Pereira, P. Overview of Chemotaxis Behavior Assays in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guirao Montes, Á.; Molins López-Rodó, L.; Ramón Rodríguez, I.; Sunyer Dequigiovanni, G.; Viñolas Segarra, N.; Marrades Sicart, R.M.; Hernández Ferrández, J.; Fibla Alfara, J.J.; Agustí García-Navarro, Á. Lung cancer diagnosis by trained dogs†. Eur. J. Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2017, 52, 1206–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namgong, C.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, M.H.; Midkiff, D. Non-invasive cancer detection in canine urine through Caenorhabditis elegans chemotaxis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küntzel, A.; Oertel, P.; Fischer, S.; Bergmann, A.; Trefz, P.; Schubert, J.; Miekisch, W.; Reinhold, P.; Köhler, H. Comparative analysis of volatile organic compounds for the classification and identification of mycobacterial species. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaim, O.; Bouchikhi, B.; Motia, S.; Abelló, S.; Llobet, E.; El Bari, N. Discrimination of Diabetes Mellitus Patients and Healthy Individuals Based on Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs): Analysis of Exhaled Breath and Urine Samples by Using E-Nose and VE-Tongue. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Health and Consumers; von Karsa, L.; Holland, R.; Broeders, M.; de Wolf, C.; Perry, N.; Törnberg, S. European guidelines for quality assurance in breast cancer screening and diagnosis: Fourth edition, supplements; European Commission, 2013; ISBN 978-92-79-32970-8. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, T.; Guraya, S. Breast cancer screening programs: Review of merits, demerits, and recent recommendations practiced across the world. J. Microsc. Ultrastruct. 2017, 5, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radecka, B.; Litwiniuk, M. Breast cancer in young women. Ginekol. Pol. 2016, 87, 659–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, U.; Guidi, G.; Martins, D.; Vieira, B.; Leal, C.; Marques, C.; Freitas, F.; Dupont, M.; Ribeiro, J.; Gomes, C.; et al. Breast cancer in young women: A rising threat: A 5-year follow-up comparative study. Porto Biomed. J. 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.-L.; Li, Y.-M. Current noninvasive tests for colorectal cancer screening: An overview of colorectal cancer screening tests. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2016, 8, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallafré-Muro, C.; Llambrich, M.; Cumeras, R.; Pardo, A.; Brezmes, J.; Marco, S.; Gumà, J. Comprehensive Volatilome and Metabolome Signatures of Colorectal Cancer in Urine: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2021, 13, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, E.; Di Rocco, M.; Schwartz, S.; Caprini, D.; Milanetti, E.; Ferrarese, G.; Lonardo, M.T.; Pannone, L.; Ruocco, G.; Martinelli, S.; et al. C. elegans-based chemosensation strategy for the early detection of cancer metabolites in urine samples. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daulton, E.; Wicaksono, A.N.; Tiele, A.; Kocher, H.M.; Debernardi, S.; Crnogorac-Jurcevic, T.; Covington, J.A. Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) for the non-invasive detection of pancreatic cancer from urine. Talanta 2021, 221, 121604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lett, L.; George, M.; Slater, R.; De Lacy Costello, B.; Ratcliffe, N.; García-Fiñana, M.; Lazarowicz, H.; Probert, C. Investigation of urinary volatile organic compounds as novel diagnostic and surveillance biomarkers of bladder cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2022, 127, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).