1. Introduction

The economic viability of electric vehicles in Africa is derailed by various obstacles, such as the requirement for sufficient charging infrastructure, tax incentives, and public awareness [

1]. [

2] highlights the significance of social and economic sustainability factors in the production of electric vehicles in sub-Saharan Africa, whereas [

3] emphasises the influence of government policy in tackling issues such as car cost and charging infrastructure. Nevertheless, [

4] highlights a crucial concern, emphasising that in nations such as South Africa, where coal is the main source of energy generation, the environmental repercussions of electric vehicles may not be substantially superior to those of internal combustion engine vehicles.

Transportation plays a crucial role within the energy system, and in the African region, there has been a notable rise in the need for road transportation services [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. This rise may be attributed, at least in part, to population growth and advancements in economic development. To illustrate the magnitude of this heightened demand, it is worth noting that emissions originating from the transport sector in Africa had a substantial growth of 84% over a span of six years during the previous decade [

10]. This trend persisted until 2018, when the transport sector in Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 15% of the total energy consumption [

11].

Nevertheless, there is currently a global shift in road-passenger transport, characterised by a transition away from conventional internal combustion engine vehicles that contribute to pollution, towards the adoption of electric vehicles with far lower emissions. The transition discussed is expected to impact sub-Saharan Africa, an area that now relies significantly on the importation of used automobiles. Moreover, the adoption of electric vehicles in this region could potentially yield advantages in terms of emission reduction and improvements in air quality. However, as of 2019, there were barely 500 electric vehicles present on South African roads [

12]; however, this narrative has rapidly changed in the last three years with the rapid production of electric vehicles by major car manufacturers, and there has been a rise in the demand for electric vehicles in South Africa.

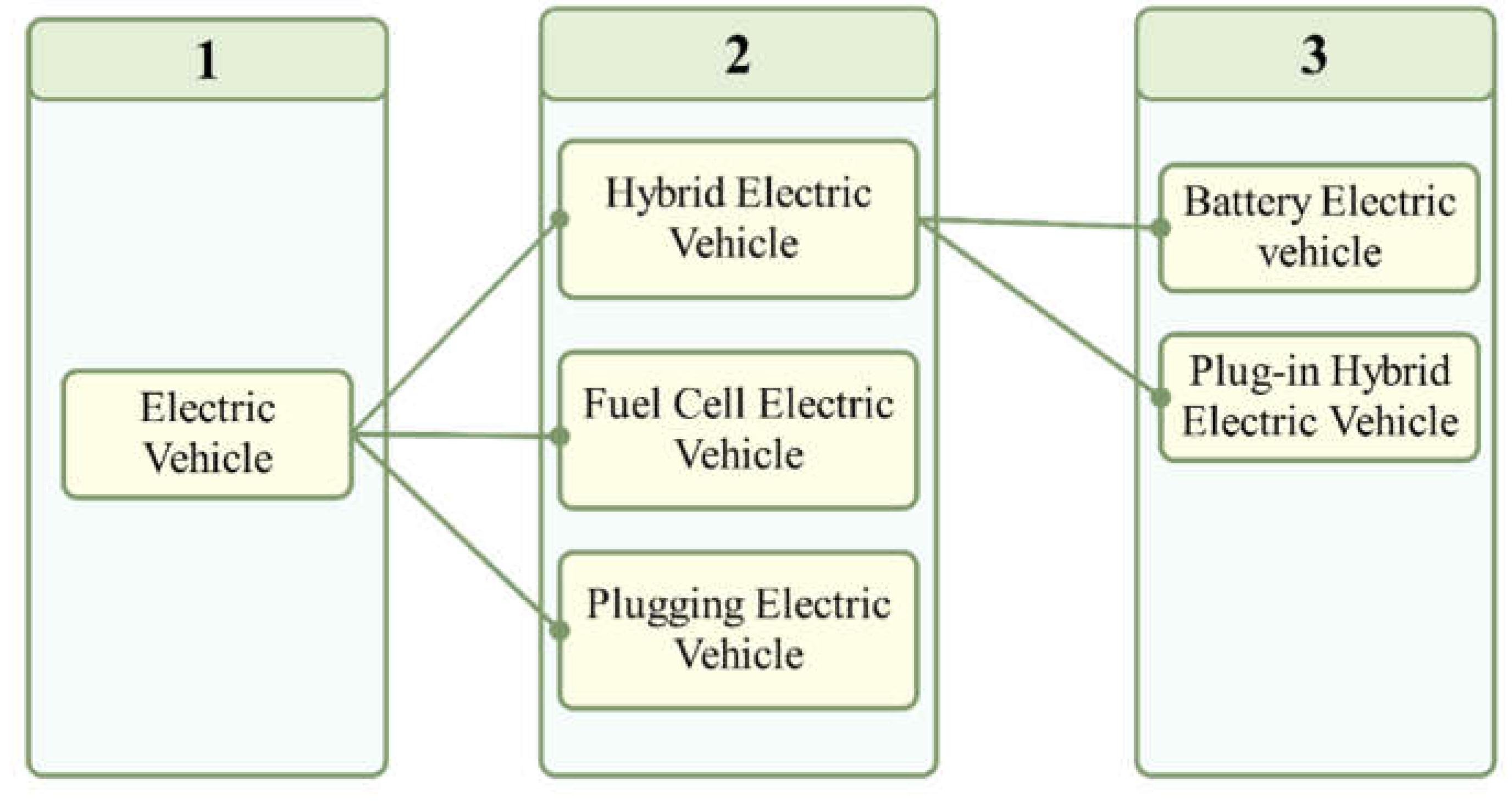

Electric vehicles have become widely adopted as viable alternatives to traditional technologies and are now an essential component of modern transportation systems. Electric cars are typically categorised into three groups depending on the energy source utilized for propulsion , as outlined by [

13] and [

14].

Hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs)

Electric vehicles that can be connected to an external power source for charging, referred to as plug-in electric vehicles (PEVs).

Fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs)

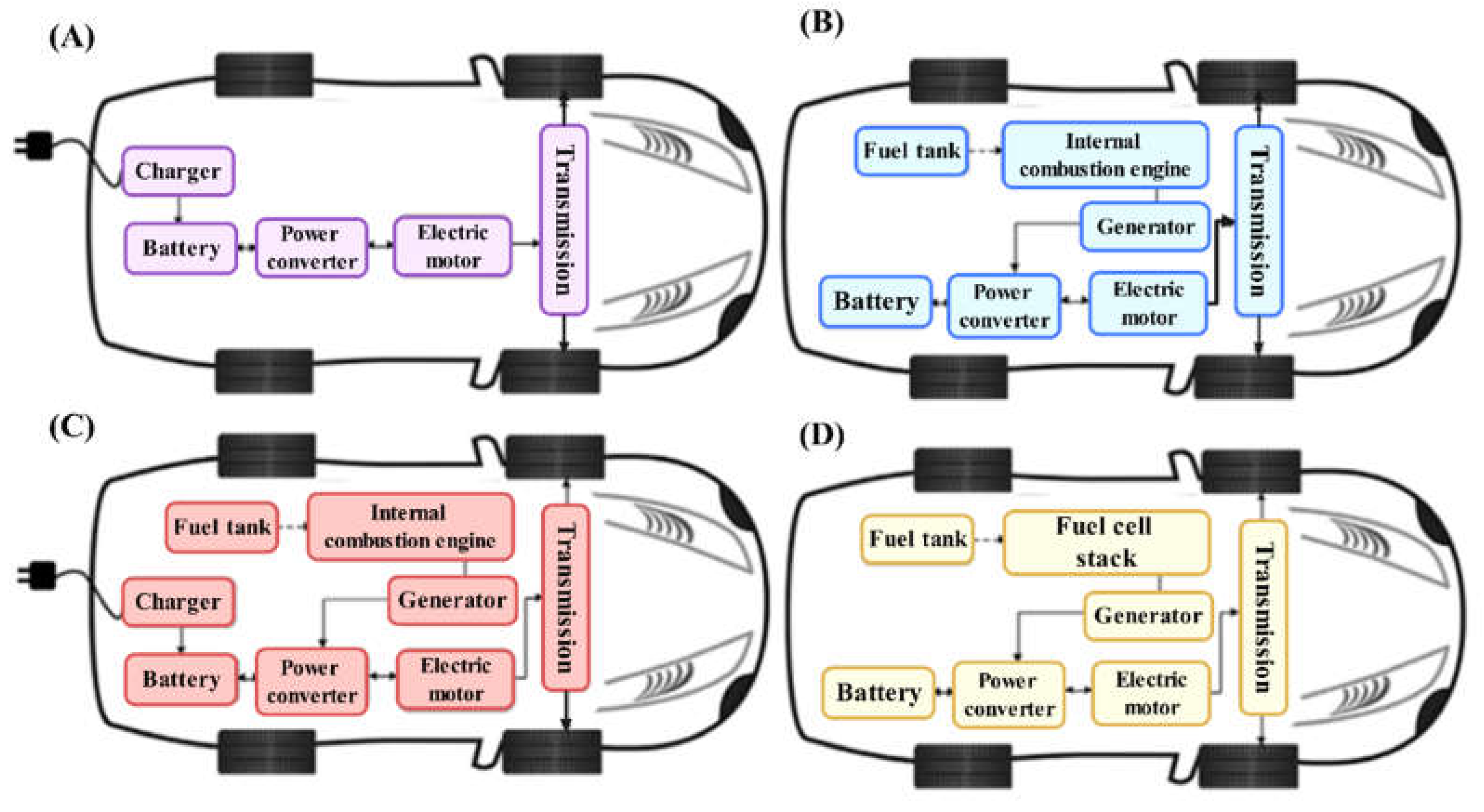

Hybrid electric vehicles are powered by both an internal combustion engine and an electric propulsion system. In comparison to traditional internal combustion engine vehicles, this allows vehicles to achieve higher fuel efficiency, emit fewer pollutants, and have extended driving options, among other benefits. PEVs encompass two main categories: Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) and Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs). Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) are propelled by electric motors and derive their power from rechargeable batteries. Once the battery is depleted, a petrol engine serves as a supplementary power source. A plug-in hybrid electric vehicle (PHEV) is typically driven by an electric propulsion system, although it can also be fitted with a petrol engine. Fuel cell-powered vehicles utilise fuel cells as their propulsion mechanism, as opposed to relying on batteries or a combination of batteries and supercapacitors (

Figure 1) illustrates the categorisation of different vehicle types.

Battery electric vehicles (BEVs) operate exclusively by using electrical power. They use an electric propulsion system and rely on the energy provided by the battery pack. The battery is replenished by external charging stations through the utilisation of recuperated braking energy, which is known as regenerative braking [

16]. Lithium-based batteries dominate the battery chemistry and architecture of several BEV models [

17]. BEVs offer numerous advantages compared to the currently prevalent fossil fuel combustion engines. In addition to its lack of exhaust emissions and independence from fossil fuels, BEVs have superior vehicle efficiency and acceleration compared to other types of vehicles [

18,

19]. BEVs possess various disadvantages, including their excessively high cost, limited durability, safety concerns related to flammable batteries, and relatively shorter driving distances than internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles. (attributed to the current low energy density of existing batteries). Moreover, only a limited number of countries or cities possess the necessary infrastructure to accommodate a significant number of new charging stations, in contrast to the widespread availability of petrol and diesel refuelling stations. According to [

20], the average battery capacity of BEV is approximately 39 kWh, calculated based on yearly sales data.

Hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) integrate an electrical power source with another power source. A HEVs typically integrates an electric motor and battery storage with a conventional internal combustion engine and fuel tank. The electric motor and combustion engine connections can be configured in a series, parallel, or series-parallel arrangements [

16]. HEVs commonly utilise lithium-based battery packs, similar to BEVs. Nickel metal hydride (Ni MH) batteries is used for the manufacturing of HEVs batteries. However, the demand for Nickel Metal Hydride (Ni MH) batteries is declining since Toyota, the primary supporter of Ni MH, is shifting to lithium batteries. [

17]. Plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) are equipped with an external charging mechanism that allows the battery to be charged by connecting to a power outlet, like battery electric vehicles (BEVs). Conventional HEV batteries receive charges exclusively from regenerative braking and internal combustion engines [

21]. PHEVs and HEVs often feature smaller battery packs than BEVs owing to the presence of an internal combustion engine [

22]. According to [

20], the average battery capacity of PHEVs is approximately 11 kWh, as calculated based on yearly sales data.

Fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), like BEVs, they only use an electric propulsion system. However, the main energy source for FCEVs is fuel cells. FCEVsare considered hybrid vehicles because they also have a battery. However, the battery in FCEVs is significantly smaller than that in BEVs. The primary purpose of batteries in FCEVs is to provide regenerative braking. Fuel cells utilise electrochemical processes to convert a fuel, usually hydrogen, into electricity and water as the sole by-product, resulting in no emissions from the exhaust. Fuel cells possess a lower weight and smaller size compared to batteries, allowing for swift recharging of the vehicle owing to the utilisation of a chemical fuel. Currently, FCEVs are more costly than Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) due to the production expenses of hydrogen (

). Additionally, various components of FCEVs must be decreased in price to be competitive, as stated by [

23] and [

24]. The predominant fuel cell utilised in fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) is the polymer electrolyte membrane [

18,

25].

Figure 2 shows the different types of electric vehicles.

Approximately 70% of transportation-related emissions in Africa are predominantly concentrated among a select group of seven nations, with Nigeria, South Africa, and Ghana being among them [

27]. Transportation emissions in Africa are experiencing a yearly growth rate of 7%, as stated by [

28], in light of the existing utilisation of 72 million vehicles. Electric vehicles (EVs) have been recognised as the most effective method for mitigating emissions within the transportation industry. According to [

29], the worldwide electric vehicle fleet experienced significant expansion in 2020, reaching a total of 10 million units over 370 distinct models. However, it is important to note that these figures only account for approximately 1% of the global vehicle fleet. The majority of electric vehicles (EVs) are located in selected regions, namely China (45%), Europe (24%), and the United States of America (22%) [

11]. Eighteen of the twenty top Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) have publicly declared their intentions to adopt electrification strategies by 2030. The European Union has recently declared its intention to fully eliminate internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) from its market within the next three decades, as reported by the International Energy Agency (IEA, 2021). Globally, approximately 22 nations have committed to implementing either a comprehensive prohibition on internal combustion engine vehicle (ICEV) sales or setting targets for 100% zero-emission vehicle sales by 2050.

The United States of America (USA) and the European Union have formulated a joint objective to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. Cape Verde remains the only African nation committed to systematically eliminating internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) by progressively establishing a collection of electric vehicles (EVs) for public and private transportation purposes by the year 2050. This is because a significant majority of original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) now have no intention of marketing or constructing electric vehicles (EVs) in Africa within the foreseeable future. Certain original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), exemplified by Volkswagen (VW), have made a firm commitment to exclusively produce electric vehicles (EVs) in the European market by the year 2035. However, it is noteworthy that these OEMs have not indicated any plans to commence the sale of new EVs in Africa until 2050. Nevertheless, a portion of the utilised electric vehicles (EVs) is anticipated to be introduced to the African market sooner than initially projected. This is mainly because a significant proportion of imported used vehicles in Africa originate from Europe and the United States [

30].

Electric vehicles (EVs) in developed nations share several key attributes. First, they are typically regarded as premium products and are produced on a large scale. Second, they primarily serve as privately owned passenger cars and are predominantly used in urban environments. Additionally, these EVs often benefit from the financial incentives provided by the government. Finally, their introduction is accompanied by the belief that the electricity industry will adequately meet the increased power demand they generate. Upon conducting a comparative analysis of these qualities in relation to the African setting, three fundamental justifications emerge as to why the strategies employed by industrialised nations in the realm of vehicle electrification may not be suitable for implementation in Africa. The three key factors that influence transportation systems are mobility patterns and vehicle characteristics, availability of finance, and unreliable state of electricity networks. Noteworthy is that, the characteristics of transport networks in Africa differ significantly from those found in affluent countries [

31]. In the African context, a significant proportion of travel is facilitated through privately owned and informally operated modes of transportation commonly referred to as paratransit. These vehicles are characterised by their demand-responsive nature and are frequently overlooked by transportation planners. Paratransit vehicles encompass many modes of transportation, such as motorbike taxis (often known as boda-bodas), 16-seater minibuses (referred to as matatus), and auto-rickshaws (also known as tuk-tuks) [

32].

In contrast, in the United Kingdom, a mere 13% of automobile journeys are carried out by public transit, whereas the overwhelming majority, accounting for 85%, are accomplished through the use of private cars [

33]. Considering the aforementioned disparities in transport systems, it can be inferred that the private electric vehicle (EV) model is not well suited to cater for the prevailing transport requirements in Africa. To address transportation needs in Africa, it is imperative to devise novel strategies for the development of electric vehicles (EVs) that are tailored specifically to the region. This includes the design and implementation of EVs, such as minibuses and motorbikes, which are suitable for the African context. Additionally, it is crucial to establish acceptable business models that cater to paratransit vehicle owner operators, who play a significant role in the transportation sector.

Furthermore, it is worth emphasising that access to finance in most African countries is far lower than in western countries. The acquisition of pre-owned automobiles from industrialised countries is mostly driven by a scarcity of finance. According to a study, it has been observed that in Africa, a significant proportion of yearly vehicle registrations, more than 60%, are attributed to the acquisition of pre-owned automobiles [

30]. In certain nations, such as Nigeria and Uganda, the prevalence rates may reach as high as 90% [

34]. According to the source [

30], reports indicate that these pre-owned automobiles exhibit substandard safety and environmental measures. Given these factors, to facilitate the shift towards electric cars (EVs), it is imperative that the price be deemed reasonable by owner-operators, comparable to that of pre-owned vehicles powered by internal combustion engines (ICE).

Additionally, it is worth noting that the electrical system in numerous African countries is characterised by its unreliability and insufficiency [

35]. In Sierra Leone, the occurrence of unscheduled blackouts reached a daily average of 53 incidents in 2017. Rolling blackouts are a frequent occurrence in South Africa, which is considered one of the wealthier nations on the African continent [

36]. In affluent nations, there is a prevailing assumption that power is reliably accessible as needed. However, it is obvious that this cannot be similarly asserted in African countries. Hence, it is imperative that the development of electric transport is closely aligned with the electricity infrastructure. The utilisation of electric vehicles in Africa has been hindered by a dearth of financial support from governmental entities and the inconsistent power supply required for charging infrastructure. Electric vehicles (EVs) have the potential to bring about a significant transformation in the African transportation system. This transformation can be achieved through the reduction of traffic congestion at intersections and freeways as well as the decrease in greenhouse gas emissions [

6,

9,

37,

38]. Hence, it is imperative to prioritise the sustainability of electric vehicles usage and actualisation of smart cities in Africa. The key issues facing the usage and sustainability of African electric vehicles are as follows:

The absence of sufficient charging infrastructure, especially in rural areas, obstructs the ability of electric vehicle (EV) users to use charging stations. This is mostly due to the inconsistent performance of the power grid, which can have a substantial impact on the charging process of EVs.

High Initial Cost: Electric vehicles are less accessible to a large segment of the public owing to their greater upfront cost compared to internal combustion engine automobiles.

Energy source: Electric vehicles may have fewer environmental benefits in fossil fuel-heavy locations.

Technology Access: Limited availability of new EV technology and infrastructure can slow adoption.

Awareness and Education: Electric vehicles’ benefits, performance, and cost-effectiveness may be unknown to many.

Policy and regulations: Electric vehicle development and acceptance can be hampered by insufficient legislation and laws.

Battery Technology: Buyers may be deterred by battery longevity and replacement costs.

Supply Chain Issues: Market availability of electric automobiles may limit consumer choice.

Maintenance and Repair Services: Lack of trained electric car maintenance and repair professionals can be difficult.

Perception and Culture: Cultural preferences and perceptions may affect electric car uptake.

Distance and Range Anxiety: Range anxiety may be caused by electric vehicle range concerns, especially in large countries with long distances.

Government Support: Lack of government incentives, subsidies, and support for EVs can slow adoption.

Some of these issues are linked and require a multifaceted approach from governments, businesses, and communities. The primary objective of this overview research paper is to provide a thorough analysis of the existing state of electric vehicle (EV) usage in Africa by addressing these research questions:

RQ1: What are the challenges encountered by governments regarding electric vehicle adoption and what are the viable strategies to expedite the shift towards electric mobility?

RQ2: What is the significance of African countries’ investment in electric vehicle (EV) infrastructure and overcoming obstacles that impede its mainstream adoption through the examination of successful case studies and creative efforts?

RQ3: What is the valuable contribution towards the advancement of comprehensive solutions that foster sustainable transport and facilitate the transition towards an eco-friendlier future within the African road transportation system?

The format of this overview consists of nine sections, including an introduction section that explores the various types of electric vehicles and the research questions employed in the current study. The second section begins by outlining the theoretical framework of the global growth of electric vehicles. Section three is concerned with the evolution of electric vehicles in Africa and section four is composed of the challenges associated with electric vehicles adoption in Africa. Section five presents the solution for the implementation of sustainable electric vehicles adoption in Africa. Section six gives an overview of the environmental and economic benefits of electric vehicles in Africa. Section seven includes the discussion of the whole research overview and section eight presents the policy recommendations towards the sustainability of electric vehicles in Africa based on the United Nations Sustainability development goals. Section nine draws upon the entire research overview, tying upon the various theoretical and empirical strands surrounding the sustainability of electric vehicles in Africa.

2. Global Growth of Electric Vehicles

The utilisation of electric propulsion in vehicles is not a novel concept [

39]. Thomas Devenport, in 1834, constructed a compact automobile propelled by a voltaic battery, establishing himself as the trailblazer in the field of electric vehicles [

40]. The lead-acid battery, invented by Gaston Planté in 1859, and the generator, created by Warner von Siemens in 1866, had a profound impact on the development of electric vehicles. In 1882, Percy and Ayton created a tricycle, which was the first successful electric vehicle. Batteries operated the tricycle with an approximate weight of 45 kg. Electric vehicles at that time offered several advantages over steam vehicles, including quiet operation, user-friendly controls, excellent performance, compact engine size, and simplified drive system installation [

39].

During the late 19th century, electric carriages and small two-seater electric vehicles appeared in some European cities. These vehicles could travel up to about 48 kilometres. In 1898, an electric vehicle attained a remarkable velocity of 63.2 km/h, establishing a pioneering milestone. Conventional electric vehicles failed to replace horse-drawn transportation due to their limited range, high production costs, and the frequent need for battery recharging [

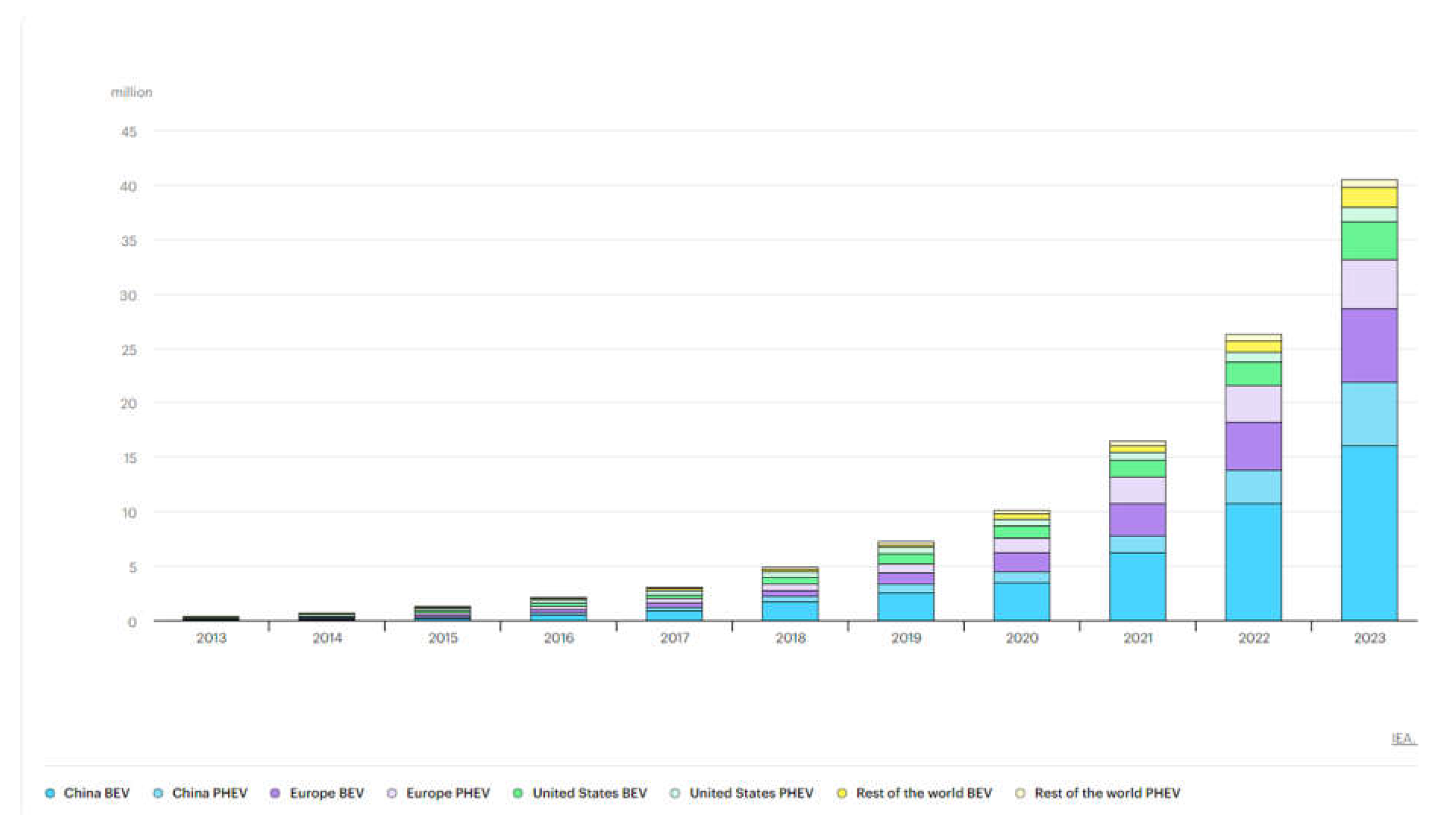

39]. Even though there were problems in the supply chain, high commodity and energy costs, and uncertainty in the macroeconomy and geopolitics, 2022 was another record year for the sales of electric vehicles. In a world where car sales are falling, the sales of all cars will fall by 3% in 2022 compared to 2021. Simultaneously, there was an increase in the sales of electric vehicles. In 2022, more than 10 million BEVs and PHEVs were sold, which was 55% more than that in 2021.

Based on Error! Reference source not found, global sales of EVs are projected to reach ten million, surpassing the 9.5 million cars expected to be sold in the European Union and nearly half of the cars projected to be sold in China in 2022. EV sales surged from around 1 million to over 10 million in a span of just five years, from 2017 to 2022 The period from 2012 to 2017 experienced a five-year span during which the sales of electric vehicles (EVs) escalated from 100,000 units to one million units. This shows how quickly EV sales grew. Electric cars will make up 14% of all new cars sold in 2022, up from 9% in 2021. That is more than 10 times their share in 2017 [

41]. Owing to increased sales, there are now 26 million electric cars on the roads around the world, which is 60% more than in 2021. As in previous years, BEVs account for over 70% of all annual growth. Because of this, approximately 70% of all electric cars on the road in 2022 were BEVs. From 2021 to 2022, sales went up by 3.5 million, which is the same amount as from 2020 to 2021. However, from 2020 to 2021, sales grew more slowly (twice as much). EV markets may have been making up after the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic, which could explain the huge growth in 2021. In 2022, the annual growth rate for electric car sales was approximately similar to the average rate observed from 2015 to 2018, compared to the preceding years. Similarly, the annual growth rate for the global stock of electric cars was approximately the same as that in 2021 and from 2015 to 2018. This shows that the EV market is growing at a strong rate again, just as it did before the pandemic [

41].

Electric vehicles have existed for the previous two centuries, with many prototypes created in the late-1800s [

42]. However, it was not until the 2000s that electric vehicles suitable for highway usage became widely accessible globally. Nevertheless, the waning interest in electric vehicles might be attributed to the constrained storage capabilities of batteries and advancements in internal combustion engines [

42]. The oil crisis in the 1970s sparked renewed interest with electric vehicles [

18]. Since then, electric vehicles have experienced periodic comebacks, with the most recent and significant rise occurring since the 2000s [

43]. Battery electric vehicles currently hold a dominant position in the electric vehicle market. Companies such as Tesla in the United States have contributed to increased market penetration, along with the introduction of revolutionary vehicle types such as the Chevrolet Bolt and Nissan Leaf. Furthermore, battery electric vehicles exhibit superior fuel efficiency compared to internal combustion engine vehicles, enabling them to travel longer distances with less energy use. Battery electric vehicles have lower overall greenhouse gas emissions than internal combustion engine rivals. These attributes are favourable indicators for future advancements in battery-electric vehicles. Other options for battery electric vehicles are currently under development [

42].

In 2016, Toyota, Honda, and Hyundai offered passenger models of Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles (FCEVs). Additional vehicle manufacturers have declared their plans to create Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles (FCEVs) in the future, as indicated by [

23,

44]. However, prominent car manufacturers such as BMW, Daimler, and VW appear to be exclusively concentrating on Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) at present. Future sales of Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles (FCEVs) are expected to be primarily focused on heavy-duty passenger and freight transportation in specialised areas [

42].In recent years, the international electric vehicle market has experienced significant growth. Currently, the number of electric vehicles in circulation exceeds five million, encompassing not only electric cars but also electric buses. China has been the primary driver of growth in recent years, with its vehicle fleet increasing from 11,600 in 2012 to 350,000 in 2016, surpassing 2 million vehicles in 2019. China aims to achieve a target of five million electric vehicles by 2020 and is now the global leader in electric vehicle production, with BYD being the top manufacturer. Other prominent manufacturers in this sector include Renault Nissan from France and Japan, Tesla from the United States, and BMW from Germany [

45,

46,

47]. In 2017, the worldwide sales of vehicles surpassed 1 million for the first time, excluding non-plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs). On a global scale, Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) account for 66% of all electric vehicle sales. PHEVs dominate the majority of new sales in certain areas, such as Japan, accounting for two-thirds of the total. Within the European Union (EU), the annual sales of Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) and Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs) are approximately equal [

42].

Currently, over 75% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions originate from the energy sector [

48] and road transportation (traffic congestion) [

37,

49,

50]. To achieve the objective of restricting global warming to

, the energy sector must reach a state where carbon emissions are completely offset by the middle of the century [

51]. The rising energy demand is a significant obstacle in lowering emissions, as fossil fuels have primarily been the main cause of it and have grown at an average annual rate of 1.9% since 2000 [

52,

53,

54]. Despite a potential decrease in the carbon intensity of the global energy system, it would require approximately 150 years to completely eradicate carbon dioxide emissions at the current rate [

55]. By 2022, the global concentration of carbon dioxide will reach an unprecedented level of 417.2 parts per million, primarily due to emissions induced by human activities related to energy production. The continuous rise in concentrations of these primary greenhouse gases, including the unprecedented increase in methane levels, [

56]leads to a rise in the Earth’s temperature and causes environmental concerns [

11].

The Paris Agreement was implemented in 2015 to address the increasing levels of greenhouse gases and rising global temperatures [

57]. The initiative aimed to constrain the increase in world temperature to 2 ◦C by the year 2100. In addition, countries have declared their commitment to attaining carbon neutrality and reaching a state of net-zero carbon emissions by either the year 20250 or 2060. To achieve the goals set by the Paris Accord and advance sustainable development, it is crucial to reduce carbon emissions in the energy sector and significantly increase the use of renewable energy and energy-efficient technologies, especially in the transportation sector [

58]. The transition to electric vehicles (EVs) is recognised as a powerful component in reducing the environmental effect of the transportation industry and cutting greenhouse gas emissions, as stated in the existing plans [

59].

EVs, which emerged as a new technology following the Industrial Revolution, have been around for almost a century. Thomas Parker pioneered the development of the first operational electric vehicles in 1884 [

60]. However, throughout the 20th century, there have been fluctuating levels of interest in electric vehicles. In 2021, China led the global market in electric vehicle (EV) sales, with a share of 50.31%. Germany, the United States, and the United Kingdom followed with sales percentages of 10.22%, 9.89%, and 4.83% respectively [

61]. This suggests that the electric vehicle (EV) fleet worldwide has experienced significant growth and is expected to continue expanding rapidly in the next ten years. Projections indicate that by 2040, electric vehicles (EVs) are predicted to make up 57% of all passenger car sales and over 30% of global passenger vehicle fleets [

62].

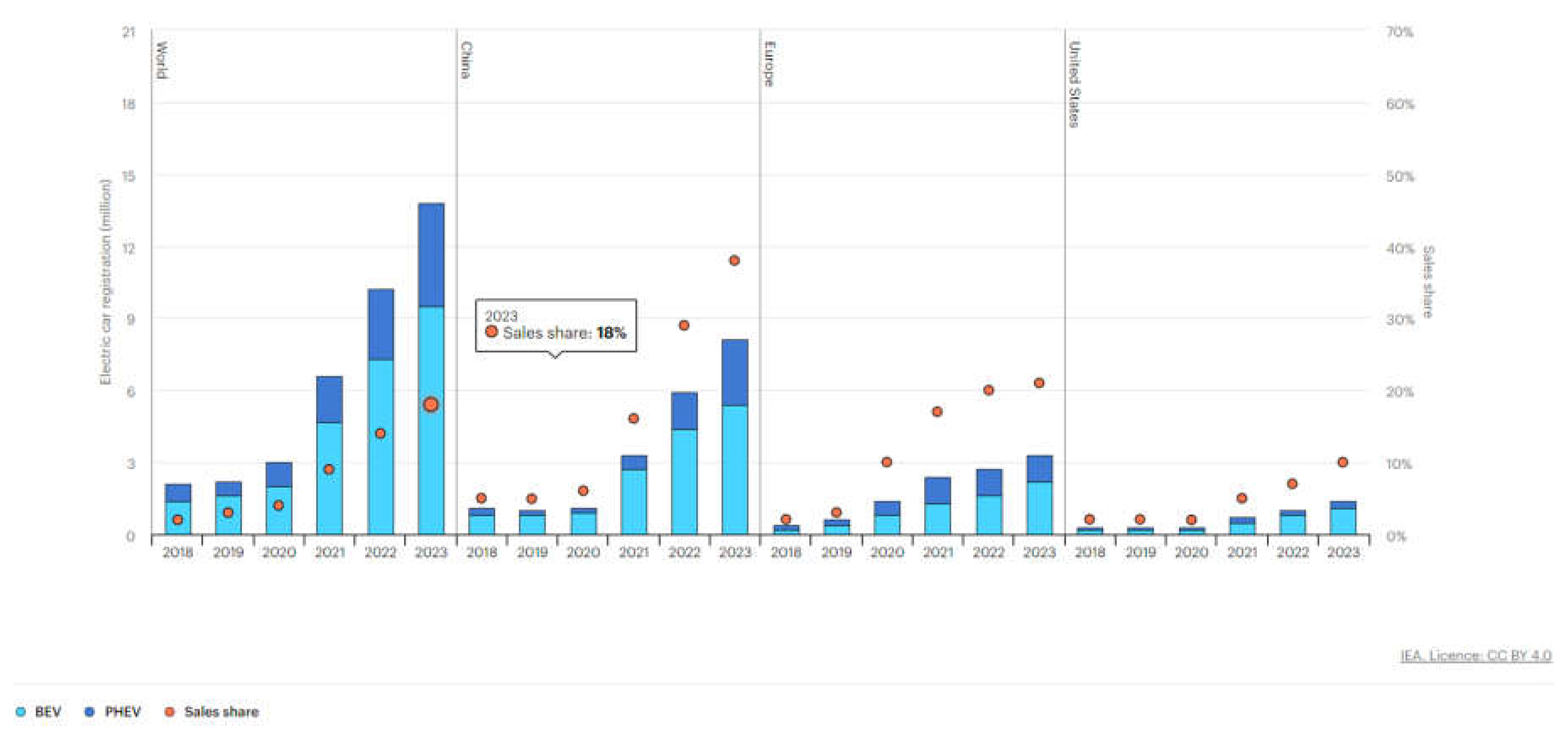

A total of 14 million new electric cars were registered worldwide in 2023 (

Figure 4), resulting in a cumulative number of 40 million electric cars on the roads. These figures closely align with the sales projection outlined in the 2023 edition of the Global EV Outlook (GEVO-2023) in

Figure 3. The sales of electric cars in 2023 exceeded those in 2022 by 3.5 million units, representing a year-on-year growth of 35%. This represents an increase of over sixfold compared to the year 2018, which occurred only five years prior. In 2023, the number of new registrations each week exceeded 250,000, surpassing the total number of registrations in 2013, which occurred ten years prior. In 2023, electric vehicles constituted around 18% of total car sales, a significant increase from 14% in 2022 and a mere 2% in 2018, five years prior. These data suggest that the growth of electric car markets continues to be strong as they become more established. In 2023, battery electric cars constituted 70% of the total number of electric automobiles [

63].

Although there is a global increase in the sales of electric automobiles, they are still predominantly centred in a limited number of big markets. In 2023, about 60% of newly registered electric cars were in China, while Europe accounted for just under 25% and the United States for 10%. These three regions collectively represented nearly 95% of global electric car sales. Electric cars have a significant presence in the car markets of various countries: in 2023, more over 33% of new car registrations in China were electric, over 20% in Europe, and 10% in the United States. Nevertheless, sales in other regions, including countries with well-established automotive industries like Japan and India, continue to be restricted. Due to the concentration of sales, the worldwide inventory of electric cars is likewise becoming more concentrated. However, it is important to note that China, Europe, and the United States collectively account for around two-thirds of both automobile sales and stocks worldwide. This implies that the shift towards electric vehicles (EVs) in these areas has significant implications for global trends [

63].

China experienced a 35% increase in new electric car registrations in 2023, reaching a total of 8.1 million registrations. This figure is compared to the previous year, 2022. The primary driver of growth in the overall auto industry was the rising sales of electric vehicles. While conventional cars experienced an 8% decline, the entire car market expanded by 5%, underscoring the ongoing success of electric car sales as the market evolves. In 2023, China’s New Energy Vehicle (NEV) industry operated without relying on national subsidies for electric vehicle (EV) purchases for the first time. These subsidies had been important in driving market growth for almost ten years.

The tax exemption for electric vehicle purchases and non-financial support will continue to be in effect, following an extension, due to the recognition of the automotive industry as a crucial catalyst for economic expansion. There is still ongoing backing and investment from provinces that are crucial to China’s electric vehicle industry. With the market reaching a more advanced stage, the industry is now experiencing a period characterised by heightened price competition and consolidation. Furthermore, China’s automobile exports reached a staggering 4 million units in 2023, solidifying its position as the leading global exporter in the automotive industry. Notably, out of these exports, 1.2 million were electric vehicles (EVs). The car exports for the current year have significantly surpassed those of the previous year, with an increase of about 65%. Additionally, the exports of electric cars have experienced a remarkable growth of 80%. Europe Europe and countries in the Asia Pacific area, such as Thailand and Australia, were the primary export markets for these cars [

63].

In 2023, the number of newly registered electric vehicles in the United States reached 1.4 million, representing a growth of over 40% compared to the previous year, 2022. Although the rate of yearly growth in 2023 was slower compared to the previous two years, the demand for electric cars and the overall increase in numbers remained robust. In 2023, the updated criteria for the Clean Vehicle Tax Credit, together with reductions in the prices of electric cars, resulted in certain popular electric vehicle models becoming eligible for the credit. The sales of the Tesla Model Y experienced a 50% growth in comparison to 2022 following its qualification for the complete USD 7,500 tax credit. In general, the newly implemented criteria of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) seem to have positively influenced sales in 2023, despite initial worries about stricter domestic content regulations for electric vehicle (EV) and battery production causing potential bottlenecks or delays, as shown with the Ford F-150 Lightning. Starting in 2024, revised guidelines for tax credits have resulted in a decrease in the number of eligible car models to less than 30, down from approximately 45.4. This includes the exclusion of various trim levels of the Tesla Model. However, starting in 2023 and 2024, electric cars can still be eligible for tax credits under leasing business models, even if they don’t completely match the requirements. This is because leased cars can qualify for a less stringent tax credit intended for commercial vehicles, and the savings from these tax credits can be transferred to the individuals leasing the cars. These techniques have also helped in the continuous implementation of electric cars.

Figure 4.

Electric vehicle registrations and sales market share in China, the United States, and Europe from 2018 to 2023 [

64].

Figure 4.

Electric vehicle registrations and sales market share in China, the United States, and Europe from 2018 to 2023 [

64].

Table 1.

Studies on EVs in Africa.

Table 1.

Studies on EVs in Africa.

| Related Studies |

Significant findings |

Research Questions |

Conclusions |

| [1] |

The study presents a thorough examination of the present condition, difficulties, and prospective prospects for widespread acceptance of electric vehicles (EVs) in South Africa. Furthermore, it underscores the significance of elements such as charging infrastructure, tax incentives, public awareness, stakeholder involvement, and material availability in facilitating the widespread adoption of electric vehicles. |

What obstacles and potential advantages are there for the widespread adoption of electric vehicles in South Africa? |

The automotive sector in South Africa ranks among the leading contributors to carbon emissions. |

| [2] |

The study introduces a set of metrics for assessing the social and economic sustainability of manufacturing facilities in the least developed nations. Furthermore, these signs are elaborated upon to offer a more thorough evaluation. Furthermore, it summarises the changes in the electric vehicle manufacturing industry towards sustainability, the acceptance of electric vehicles, and the rise of new markets. Moreover, it highlights the capacity of the automotive sector to exert a lasting impact on areas in a sustainable manner. |

What methods may be used to assess and enhance the sustainability of vehicle production in the least developed nations? |

This research presents sustainability indicators for car production. OEMs in developed and developing nations use the indicators. They made recommendations for our ‘aCar mobility’ initiative. Based on their research they recommend the following:

Long-term location planning: Sustainability-wise,

location decisions for least developed countries are long-term.

Population benefits rise with local production duration.

Collaboration with local government and research institutions:

Local government engagement helps enterprises survive economically.

Local R&D relies on long-term collaboration with educational institutions. |

| [3] |

The key findings of the paper include the recognition that the cost of electric vehicles is perceived as the primary obstacle to their adoption, the significance of policy incentives in boosting electric vehicle sales, and the government’s role in offering incentives to companies that invest in electric vehicle manufacturing and consider consumer subsidies. The government’s implementation of the Green Transport strategy by the South African Government emphasises the promotion of electric vehicles on a large scale. |

“What are the potential catalysts that can be investigated to enhance the proliferation of electric vehicles in the South African automotive market?” |

In the research, participants in a study in Gauteng have identified numerous challenges to the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs), underscoring the necessity for policy and incentive reforms. The study highlights the substantial influence of the South African government in encouraging the use of electric vehicles (EVs), which includes offering financial incentives to consumers, assisting in the production of EVs, and investing in research and development. Furthermore, the crucial elements for success in the adoption of EVs in South Africa include developing charging infrastructure in partnership with the private sector, as well as transport-related incentives such as toll exemptions. The efficacy of electric vehicles (EVs) in other nations, supported by governmental initiatives, underscores the potential influence of the Green Transport Plan in South Africa. However, the study acknowledges its limits in terms of sample size and recommends the necessity for more comprehensive future research. |

| [4] |

In addition to increasing emissions of sulphur oxides and nitrogen oxides in 2010 and beyond (2030), electric vehicles in South Africa do little to mitigate emissions of greenhouse gases. Currently, there isn’t much of an environmental benefit to using electric vehicles. In addition to increasing emissions of and , implementing EVs in South Africa would have little effect on reducing overall GHG emissions. |

What are the present and future energy and environmental implications of electric vehicle adoption in South Africa? |

By eliminating user emissions, South Africa’s electric automobiles improve air quality. Electric vehicles emit 35 to 50 times more SOx than conventional automobiles, limiting their environmental benefits. Advanced coal-fired power plant technology and renewable energy make the grid cleaner, while electric vehicles emit more GHGs. Electric vehicles minimise CO2 emissions by 18% to 31% per kilometre in 2030. Electric vehicles still emit four to six times more life cycle NOx than liquid fuel vehicles. New solutions to reduce SOx and NOx emissions for electricity generation are needed to improve electric automobiles. |

| [65] |

Among the most significant findings are the following: the difficulties of implementing EVs in smart cities, the role EVs play in cutting down on carbon emissions, the growth of EVs’ worldwide market share, and the bright future that EVs have due to improvements in battery technology and enabling regulations. |

In smart cities, how can electric vehicles be best integrated, and what kind of collaboration is required to overcome the most significant challenges? |

Smart cities are embracing electric vehicles (EVs) because they can build sustainable and efficient ecosystems. Their acceptance may be hindered by high upfront costs, inadequate charging infrastructure and limited driving range. These can be overcome with government legislation, private-sector investment, and public education. Governments offer financial incentives, set minimum targets for electric vehicle (EV) sales, and provide financing for charging infrastructure. Private firms can establish charging infrastructure, develop innovative business models, and collaborate with automakers. EVs driving range anxiety and people’s perception of using EVs can be addressed by public awareness. EVs will become cheaper and more convenient as battery technology improves, making transportation more sustainable. |

| [66] |

The primary findings are as follows: - Traditional automobiles release a considerably higher amount of CO2 emissions in comparison to electric vehicles, mostly due to Ghana’s energy composition.- The ownership expenses of an electric vehicle are at least 13.5% more in comparison to a Toyota Corolla.- To enhance electric vehicles adoption in Ghana and other African countries, it is crucial to tackle obstacles such as shortage of expertise in electric vehicle maintenance, limited availability of spare parts, and inadequate charging infrastructure. |

In Ghana and across Africa, what are the pros and cons of owning an electric vehicle? |

The study found that Toyota Prius has a 30% lower cost per mile than Toyota Corolla, however electric vehicles cost 13.5% more to own. Tax incentives to remove import charge in Ghana will only lower cost per mile by 2.5%. The energy excess of 98.59 GWh in Ghana could charge 1.5 million electric automobiles. However, a major skills gap in electric vehicle maintenance, lack of replacement parts, charging infrastructure, and the initial cost of electric automobiles are the key obstacles to electric vehicle penetration in Ghana and other African countries. |

| [67] |

Considering the storage capacity of electric vehicles or electric motorcycles, the research advocates for a linked approach to energy and mobility improvements. |

How can electric vehicle and motorcycle storage capabilities be considered in the development of energy access and mobility in Africa to spur economic growth? |

Electric mobility approaches have the potential to add distributed energy storage capabilities to electrical grids, according to their analysis of current and future smart grid technologies. |

| [68] |

The key findings encompass the growing significance of incorporating social factors into the evaluation of e-mobility sustainability, the comprehensive examination of existing scholarly articles that concentrate on the social dimension of electric vehicles, the identification of priorities such as “climate actions” and “sustainable cities and communities”, the prevalent utilisation of methods for assessing social impact, the dissemination of published papers across various journals, and their relationship to certain UN Sustainable Development Goals. |

What are the current and future study objectives regarding the public perception of electric vehicles and their relationship with specific UN Sustainable Development Goals? |

The UN has performed study on the social sustainability of electric vehicles (EVs), specifically examining user experience, societal readiness, and welfare. The study emphasises the necessity for more thorough assessments that incorporate social effect, environmental, and economic dimensions. Subsequent studies ought to establish quantitative measures for evaluating the societal impact of electric vehicles (EVs). |

3. Evolution of Electric Vehicles in Africa

According to related research, Africa emerges as the continent most susceptible to the impacts of climate change, particularly under warming scenarios exceeding 1.5 °C [

69]. In the year 2020, Sub-Saharan Africa exhibited the greatest levels of

exposure globally, leading to the highest observed rate of newborn mortality associated with air pollution [

70]. The adoption of electric vehicles in transportation fleets offers a promising avenue for mitigating the environmental impact of vehicle emissions by reducing carbon footprints. Renewable energy sources have the potential to be utilised to enhance a nation’s energy security, promote sustainable development, fulfil the objectives of many sustainable development goals, and enhance a country’s appeal for investment [

71].

Electric vehicles (EVs) have been found to be three times more efficient than internal combustion engines (ICE). This notable advantage of EVs presents a substantial opportunity to effectively mitigate vehicular emissions, enhance air quality, and reduce noise pollution [

72]. The carbon dioxide emissions from vehicles in Africa are experiencing a yearly growth rate of 7% on average

. The aforementioned percentage exhibits a significant disparity when compared to the average rates of 0.8% in the United States and 0.12% in the United Kingdom, despite Africa having more than four times the number of vehicles [

73]. Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Libya, Morocco, Nigeria and South Africa (SA) collectively accounted for a minimum of 70% of Africa’s automotive emissions. The increasing emissions from vehicles can be attributed to several issues, including the ageing of vehicle fleets, inadequate maintenance practices, subpar fuel quality, the absence of stringent vehicle regulations, and insufficient enforcement of existing vehicle standards.

The substandard nature of fuels has emerged as a significant obstacle to achieving reduced emissions, especially for more recent automobile models. European vehicles produced after 2011 have been engineered to operate on fuel containing a maximum sulphur content of 10 parts per million (ppm) [

74]. Vehicles produced in the year 2015 are engineered to adhere to sulphur restrictions that are set at levels below 10 parts per million [

75]. These vehicles were equipped with emission systems that exhibited sensitivity to elevated levels of sulphur content. An illustration of this may be seen in the Lean NOx traps, which are engineered to mitigate the release of nitrogen oxide emissions.

However, their efficacy is contingent upon the fuel sulphur content being maintained at levels below 15 parts per million [

76]. Regarding the reduction of emissions, the efficacy of modern automobiles equipped with advanced emission devices is contingent upon the calibration of the fuels they utilise. The utilisation of unclean energy sources poses a significant obstacle to ongoing endeavours and initiatives aimed at mitigating vehicular emissions. Several countries, including Algeria, Egypt, Mali, Nigeria, Togo, Somalia, and Zambia, have sulphur concentrations ranging from 2000 ppm to 10,000 ppm in their diesel fuels [

30]. Globally, this has adverse effects on emissions, maintenance expenses, and the overall lifespan of vehicles.

A significant majority of African nations (47 out of the total 54) lack established regulations pertaining to gasoline quality. Furthermore, the majority of the fuel supplied across Africa falls below the Euro 0 level in terms of quality, as indicated by previous research [

77]. The availability of the recommended gasoline quality for imported automobiles in Africa is limited in practice. The pursuit of cleaner fuels and advancements in vehicle emission technologies in Africa is a formidable challenge. The integration of electric mobility is of utmost importance for fostering the advancement of a sustainable and environmentally friendly trajectory for Africa.

3.1. Electric vehicles Usage in Africa

Over the next two decades, the African agenda acknowledges that poverty, inequality, and unemployment are all associated with a lack of viable energy on the continent [

78,

79]. This would necessitate the implementation of pragmatic and efficient strategies. These proactive approaches could help Africa progress towards a prosperous path by establishing an energy supply system that is inclusive and has a minimum impact on the environment. Decarbonisation, the process of shifting the road transport system to electric vehicles in both developed and developing nations, is a crucial strategy for attaining this objective. This is especially pertinent considering the results of the 26th Conference of Parties (COP26) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) that took place in Glasgow, Scotland. The conference, organised jointly by the United Kingdom and Italy, occurred between the dates of 12 October and 12 November 2021. The primary focus of the outcomes of COP26 was on countries worldwide implementing decisive measures in four crucial domains: mitigation, adaptation, finance, and cooperation. The energy challenge in Africa necessitates a multifaceted strategy, which includes reducing carbon emissions from the current thermal electricity generation infrastructure, specifically coal-powered plants, as well as transitioning away from fuel-driven vehicles. Performing a comprehensive examination of research on these methods is an essential initial stage in comprehending the overall system.

Scientific evidence abundantly shows that climate change exists on a global, continental, and national level, as indicated by greenhouse gas emissions. This is evident through various indicators, such as rising surface temperatures, altered rainfall and weather patterns, increased frequency of extreme weather events, loss of Arctic Sea ice, rising sea levels, melting of Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets, shifts in the distribution of plant and animal species, earlier leaf unfolding in spring, and changes in bird migration patterns. These changes include inherent hazards that impact individuals, the environment, and the economy. Climate change arises from the release of greenhouse gases (GHG) into the environment through natural and/or human activities. Recent evidence indicates that human activities, which produce greenhouse gases (GHG), are mostly responsible for current climate change.

Since 2010, the nation of Mauritius in East Africa has effectively developed a fiscal incentive framework to facilitate the importation of electric vehicles. According to [

80], 242 battery electric vehicles were registered during the period from 2011 to June 2020. According to [

81], a total of 15,079 hybrid electric vehicles were registered throughout the period spanning from 2009 to June 2020. Among the total, 1030 units, or 7% of the sample, were classified as new registrations, while the remaining 14,049 units, accounting for 93% of the sample, were classified as used or second-hand registrations. According to the National Land Transport Authority [

80], in Mauritius, the annual rates for renewing electric vehicle licences and one-time registration fees are reduced by 50% compared to those for conventional vehicles. Additionally, import taxes for electric vehicles are up to 30% lower than those for conventional vehicles. The outcome demonstrates a significant increase of 350% in the use of electric vehicles from 2009 to 2020.

The assessment of inhibiting issues for electric vehicle (EV) growth, in order to address them through policy measures, can be achieved by considering the total cost of ownership (TCO). The total cost of ownership (TCO) of electric cars offers the advantage of evaluating the enduring value of their acquisition over a specific duration. The analysis examines the cost structure to identify the factors that impact the total cost of ownership. The identification of key factors will provide guidance for policy direction to facilitate the rapid adoption of electric vehicles. Additionally, the provision of this information could assist consumers and supply chains make informed decisions about transitioning their fleets, independent of government subsidies.

Typically, Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) models for automobiles encompass many factors such as the initial purchase cost, applicable taxes, ongoing maintenance expenses, and the projected resale value. However, previous studies have been unable to accurately assess the complete cost of ownership. Despite their similarities, TCO models have yielded divergent outcomes owing to variations in the characteristics and assumptions of the countries under consideration. In certain instances, meteorological conditions have exerted a notable influence on the results of the TCO. According to Hao (2020), the total cost of ownership (TCO) for BEV is reduced in cold weather conditions because of enhanced battery performance in such circumstances.

According to a study conducted by [

82], the length of time that individuals own Electric Vehicles (EV) has a substantial impact on both the overall Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) and the probability of prospective buyers deciding to buy them. In a study conducted by [

83] on EV consumer preferences and deployment in Lebanon, it was determined that the provision of free public charging facilities resulted in a notable 7.22% increase in new EV registrations. According to [

84], the competitiveness of electric vehicles (EVs) is contingent upon the provision of subsidies, as they argue that EVs can only effectively compete with conventional automobiles under such circumstances. The provision of subsidies is contingent upon several factors, such as the fluctuation of ownership costs, encompassing initial price and import tax, as well as inflation, fuel price, and electricity price.

However, the dynamics of these elements that impact the total cost of ownership (TCO) vary based on the specific country or location of the study. Regrettably, there is a limited body of research available pertaining to the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO), specifically for countries and cities located in Africa. Numerous research endeavours have been undertaken globally to investigate electric vehicles (EV), encompassing aspects such as charging infrastructure and regulatory incentives [

85]. There is a limited body of literature pertaining to electric vehicle research in Africa, with the majority of studies undertaken in South Africa [

1,

86], Ghana [

27], and Tunisia [

87].

The promotion of electric vehicles (EVs) often centres on the concept of environmental awareness [

88]. Nevertheless, the utilisation of electric vehicles alone does not lead to significant reductions in carbon dioxide emissions. Instead, it is imperative to combine electric vehicles with a decarbonised energy supply to charge them. In contrast, electric vehicles possess a higher probability of mitigating carbon emissions in instances where the energy composition predominantly consists of renewable sources. Numerous scholars have posited that the overall impact of electric car utilisation on the environment is intricately linked to the composition of the power generation mix employed within a given nation. Countries lacking an energy mix that prioritises environmental sustainability and reduces greenhouse gas emissions may not experience substantial advantages from the adoption of electric vehicles [

82,

83,

84]. An illustrative instance can be observed in South Africa, where the grid infrastructure can accommodate up to 4 million electric vehicles (EVs). However, the environmental benefits derived from this potential are minimal owing to the substantial carbon intensity of the country’s electrical system, as evidenced by [

86].

On a global scale, the future of the automotive industry is becoming increasingly focused on electric vehicles. This is mostly because of the implementation of stricter regulations, such as upcoming bans on the sale of vehicles with internal combustion engines. Additionally, changes in customer preferences and continuous advancements in battery and charging technologies have contributed to this shift. It is projected that by 2035, the primary automotive markets in the world, namely the United States, European Union, and China, will exclusively provide electric vehicles (EVs) for sale. Furthermore, it is anticipated that by 2050, electric vehicles will account for 80 percent of global vehicle sales. Electric vehicles (EVs) play a crucial role in achieving climate neutrality. For instance, in Europe, the overall emissions produced throughout the life cycle of an EV are approximately 65–85 percent lower than those of a traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle. Additionally, EVs contribute to enhancing the quality of life in urban areas by minimising air and noise pollution.

Africa’s transport sector currently contributes for 10 percent of the continent’s total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This percentage is projected to increase along with the increasing number of vehicles in sub-Saharan Africa. Within the six countries of South Africa, Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, Ethiopia, and Nigeria, which comprise approximately 70 percent of sub-Saharan Africa’s annual vehicle sales and 45 percent of the region’s population (), the number of vehicles is projected to increase from 25 million at present to approximately 58 million by 2040. This growth is primarily attributed to urbanisation and the rise in incomes. As the number of automobiles in sub-Saharan Africa increases, the region will face the issue of promoting sustainable transport while avoiding the potential problem of becoming a destination for discarded and undesired old internal combustion engine vehicles worldwide.

Several governments in sub-Saharan Africa have recently declared their goals for increasing the use of electric cars (EVs) and have introduced measures to encourage their adoption. For instance, Rwanda announced tax concessions specifically for the sale of EVs. Furthermore, there is a developing start-up ecosystem in the region that is specifically focused on electric vehicles, with a special emphasis on electric two-wheelers. By the end of 2021, McKinsey estimated that the ecosystem housed over 20 start-ups. Collectively, these startups secured funding exceeding $25 million during that year.

Sub-Saharan Africa has distinct obstacles in its shift towards electric mobility, despite the growing momentum. These issues encompass intermittent electricity provision, limited affordability of automobiles, and prevalence of second-hand vehicles. Several nations have made notable progress in enhancing electricity accessibility, with all six countries having urban-electricity-access rates exceeding 70 percent, and several even surpassing 90 percent. Nonetheless, the reliability of the energy supply continues to be a concern. According to a 2019 poll across 34 African countries, less than 50% of individuals linked to the electrical grid have access to dependable energy. Furthermore, the SAIDI for sub-Saharan Africa in 2020 was reported to be 39.30, while OECD high-income countries had an SAIDI of 0.87. The second obstacle is affordability, which is influenced by relatively low household incomes, limited access to asset financing with reasonable interest rates, and higher price ranges for electric vehicles (EVs).

A further concern is the prevalence of pre-owned automobiles in most parts of the continent, with the exception of a few countries like South Africa, where the importation of used vehicles is prohibited. Approximately 85 percent of all four-wheel vehicle purchases in the majority of sub-Saharan African countries consist of pre-owned automobiles. The import of automobiles over 15 years old and with relatively low emissions regulations is permitted by several nations owing to affordability issues and inadequate regulations. According to a 2020 assessment by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 40 out of 49 nations in sub-Saharan Africa have inadequate or extremely inadequate legislation for old vehicles. Consequently, upcoming electric vehicles may face difficulties in rivalling older, inexpensive internal combustion engine (ICE) automobiles that are easily accessible in the area. With 40 percent of all old automobiles being exported to Africa, there is a concern that the continent may become a repository for discarded internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, while the rest of the world transitions towards an electric transportation future.

4. Challenges to Electric Vehicle Adoption in Africa

Africa is a continent characterised by persistent poverty, deteriorating economic conditions, and increasing levels of air pollution. Nevertheless, the emergence of electric vehicles offers a glimmer of optimism for this continent, which ranks second in the world. African electric car manufacturers are establishing production facilities and employing large numbers of individuals, thereby offering a means of sustenance to the local population. Furthermore, the adoption of electric vehicles has resulted in decreased pollution levels, thereby making Africa more environmentally friendly. While North America (United States of America and Canada), Europe (Germany and Netherlands), and Asia (China and Singapore) have already begun switching to electric vehicles, Africa is gradually following suit. Nonetheless, the shift to Africa brings forth distinct prospects and obstacles that we examine in this section.

4.1. Scarcity of Charging Infrastructure

Several African countries experience constraints in their electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure, which might hinder the development of strong and reliable electric grids [

89]. The lack of sufficient grid capacity and the unreliability of power sources can impede the integration of extensive electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure, leading to concerns regarding the viability and long-term viability of such initiatives. For example, African countries such as Nigeria are facing severe power issues, especially with the perennial collapse of the National Grid, in a country of more than 200 million people, ensuring that there is adequate charging infrastructure is going to be an uphill task for the government.

The African continent is plagued with infrastructural challenges such as inadequate energy grids, substandard road conditions, and a scarcity of public e-chargers for electric vehicles. Although European energy grids have successfully managed the increasing adoption of electric mobility, the electrical infrastructure across many African countries is already experiencing significant pressure. Owing to frequent power outages in certain countries, the demand for electric vehicles among consumers may be constrained by poor transportation accessibility. Typical examples of these problems are in Nigeria, in which the average duration of energy availability is roughly 12 h per day (less than 5 h in some areas), and in South Africa, where the electricity supplying company (Eskom) is now relying on electricity load shedding to sustain the power grid of the country. There is also a lack of publicly accessible electric vehicle (EV) charging facilities in most African countries. By 2022, the global count of charge stations reached over 2.7 million, with China accounting for almost two-thirds of this total. It is projected that the number of charge stations will increase to approximately 17 million by 2030. Only a few African nations, including South Africa, Morocco, and Rwanda, have made significant efforts to invest in e-mobility businesses, with backing from private organisations.

4.2. Affordability and Accessibility

Africa is known for its epileptic power supply and worsening economic conditions. This has severely hindered the sustainability of electric vehicles in Africa, especially when it comes to affordability (considering that more than 80% of Africans in developing countries earn below

$1), and most African countries only have access to used cars, and accessibility to electric vehicles is usually limited. Electric vehicles (EVs) and HEVs are alternatives to public transportation that are more environmentally friendly owing to their low emissions of air pollutants and greenhouse gases (GHGs). Compared with traditional internal combustion engines (ICEs), electric vehicles (EVs) demonstrate superior energy conversion efficiency and operating performance. However, they can be constrained by a restricted driving range, lengthy recharging time, expensive batteries, and large kerb weight. Battery electric powertrains have higher capital expenses than traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) powertrains. According to [

90], it is anticipated that the cost of batteries will decrease substantially by 2030 owing to advancements in battery technology. Compared with hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs), electric vehicles (EVs) can offer more benefits if they can be charged using renewable energy sources or by generating electricity onboard [

91].

Plug-in hybrid electric cars (PHEVs) closely resemble conventional hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) but are equipped with an additional battery pack that can be charged by connecting to an electrical outlet. This allows for an extended driving range while simultaneously reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. PHEVs are considered the leading electric car technology in the multifunctional vehicle sector [

92]. PHEVs demonstrate competitiveness when covering extended distances only for electric power and/or when there is a substantial reduction in battery costs [

93]. Upgrading the electricity network requires the least amount of effort when a single overnight charge utilising a household power supply can provide 80% of the total driving miles.

In their study, [

94] demonstrated that vehicles equipped with advanced internal combustion engines or hybrid electric choices could offer a lower overall cost compared to traditional internal combustion engines, taking into account factors such as environmental impact and oil insecurity. This was demonstrated for an annual driving distance of 12,000 miles over a span of 10 years. The cost of insecurity was estimated to be between

$0.35 and

$1.05 per gallon of gasoline equivalent. This estimation considers the military expenses required to maintain access to oil resources in the Persian Gulf. To achieve the goal of diversify oil-importing sources, it is important to thoroughly evaluate the so-called insecurity cost. This will help prevent overestimation of the total cost over the lifespan of traditional internal combustion engines (ICEs). [

95] conducted a comprehensive assessment of alternative fuel vehicles, including their energy consumption, energy security, greenhouse gas emissions, and the environmental and economic implications. They additionally conducted research to evaluate the effects of various techniques and assumptions regarding alternative fuels and vehicles.

Access to dependable and cost-effective power continues to be a significant obstacle in most African nations. Multiple locations experience regular power interruptions, blackouts, and variations in voltage, which cause significant difficulties for electric vehicle owners. Despite the efforts of green electric vehicle (EV) start-ups in Africa to make EVs more affordable for the general populace, the initial purchase cost of EV remains prohibitively high. The reason for this is the imposition of import tariffs, the absence of government subsidies, and the restricted availability of charging infrastructure.

4.3. Risks of Usage of EVs

Risk perceptions, environmental concerns and perceived costs significantly influence paratransit owners’ and drivers’ likehood to adopt electric vehicles (EVs) , especially in South Africa. Enhancing adoption intention necessitates a concentrated effort on the crucial aspects of safety and business advantages associated with electric vehicles (EVs) [

96].

4.4. Environmental Factors

The main reasons hindering people from adopting electric vehicles (EVs) in urban areas are their environmental concerns and potential economic savings. Nevertheless, the presence of charging infrastructure and income levels play a crucial role in shaping individuals’ perceptions of embracing electric vehicles. To expedite the shift to electric vehicles (EVs) in Africa, it is crucial to customise financial incentives and tackle infrastructure obstacles (Jerry A. Madrid).

4.5. Government Policies

In South Africa, government policies such as taxation have a direct influence on the pricing of electric vehicles (EVs). Additionally, limited accessibility to energy has a detrimental effect on consumer confidence and the ability of the local manufacturing sector to produce EVs. The authors, Albertus Scholtz et al., argue that to increase the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs), it is necessary to tackle these difficulties. Technological obstacles and resolutions: Implementing electric vehicles (EVs) in the last leg of parcel deliveries encounters difficulties such as the magnitude of the fleet, scheduling, and adjustments to the infrastructure. The proposed ways to overcome these challenges include dynamic wireless charging, mobile charging stations, and battery-swapping stations [

97].

5. Solutions for Sustainable Electric Vehicle Adoption in Africa

The increasing acceptance of electric vehicles (EVs) throughout Africa has encountered numerous obstacles, although there are feasible remedies that can expedite a sustainable shift. This section provides an in-depth review of various options, drawing on recent academic literature.

Establishing a resilient electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure is of utmost importance. This entails establishing sufficient charging infrastructure and maintaining the uniformity and compatibility of charging systems among various types of electric vehicles (EV). Efficiently integrating these technologies with current electrical grids is of paramount importance [

98]. For example, a study conducted in Morocco proposed enhancing the affordability and availability of electric vehicles, as well as expanding technical training facilities to enhance maintenance efforts [

99].

The adoption of electric vehicles is significantly influenced by the effectiveness of African government programs and incentives. These might include economic incentives, such as tax deductions, financial aid, and financial awards for the acquisition or manufacturing of electric vehicles. Furthermore, the implementation of environmental legislation that prioritises electric vehicles (EVs) over conventional combustion engine vehicles might expedite the acceptance and usage of EVs [

100].

Public Awareness and Education: It crucial to increase public knowledge regarding the advantages of electric vehicles (EVs), such as their diminished carbon emissions and lower maintenance expenses. Educational campaigns have the potential to debunk false beliefs and misunderstandings regarding the performance and dependability of electric vehicles, hence promoting a favourable disposition towards the adoption of EVs [

101].

Advancements in battery technology, such as batteries with increased energy density and enhanced charging speed, have the potential to alleviate concerns about the limited driving range and enhance the overall attractiveness of electric vehicles (EVs). Incorporating cutting-edge charging methods, such as wireless charging or solar-powered charging stations, can also be advantageous [

102].

Integrating renewable energy sources such as solar and wind power into the EV charging infrastructure can guarantee a sustainable EV ecosystem. This entails the creation of intelligent power networks capable of effectively handling the sporadic characteristics of renewable energy sources and delivering consistent electricity for electric vehicle charging [

103].

Promoting the use of Hybrid Electric Vehicles (HEVs) can serve as an intermediate measure towards achieving complete Electric Vehicle (EV) adoption. Hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) do not necessitate the use of charging stations and provide improved fuel efficiency, rendering them a more viable choice in regions where electric vehicle (EV) infrastructure is still in the process of being established [

104].

Market segmentation and consumer targeting include comprehending distinct consumer segments and customising techniques accordingly, which might yield favourable outcomes. This involves categorising individuals according to their level of environmental awareness, proficiency in technology, and socio-economic standing to encourage the adoption of electric vehicles in a manner that aligns with their beliefs and requirements [

105].

Collaboration among governments, private sector entities, and international organisations can result in the pooling of knowledge, cost reduction, and improved execution of electric vehicle (EV) initiatives. Public-private partnerships can expedite the establishment of charging infrastructure and offer financial support for research and development in electric vehicle technologies.

Customised Solutions: Adapting solutions particular to African circumstances is crucial. This entails considering the regional climate, road conditions, and socio-economic considerations during the process of creating and promoting electric vehicles (EVs). The domestic production of electric vehicles (EVs) and their components can effectively save expenses and generate job prospects.

Implementing techniques for battery recycling and second-life uses can effectively address concerns regarding battery waste and sustainability in the context of electric vehicle (EV) batteries. This encompasses the process of converting used electric vehicle (EV) batteries for use in stationary storage applications, thereby providing further support for the integration of renewable energy.

The widespread adoption of electric vehicles in Africa necessitates a comprehensive strategy that encompasses government policy backing, the establishment of charging infrastructures, local production, the utilisation of renewable energy sources, and public awareness campaigns. By implementing these strategies, Africa can surmount the existing obstacles to electric vehicle (EV) adoption and progress towards a transportation system that is both sustainable and environmentally benign. To summarise, the crucial factors for promoting sustainable electric vehicle (EV) adoption in Africa include a blend of technological advancements, favourable regulations, public education initiatives, and cooperative endeavours. These solutions not only tackle the current obstacles but also establish the foundation for a more sustainable and eco-friendly transport future in the continent.

6. Environmental and Economic Benefits of Electric Vehicles in Africa

The shift from fossil fuel-based to electric-based vehicles has gathered steam during the past ten years. [

106] projects that all the main global end-use industries will see continued growth in global energy use. Over the present and future years (2020–50), total final consumption (TFC) is expected to rise by almost 20%. As people increasingly rely on hydrogen, renewable energy, and electricity, the demand for fossil fuel will diminish. With the move to electric vehicles (EV), which can save up to three times as much energy as traditional internal combustion engines, transport is the sector with the biggest drop in energy consumption [

107].

As for [

106], by 2050, batteries are expected to account for more than 60% of the clean energy technology equipment market. Three terawatt-hours of battery storage and over three billion electric cars on the road by 2050 will make batteries essential to the new energy economy. Essential minerals such as lithium, nickel, and cobalt will also emerge as the single largest source of demand [

106]. Over the past ten years, sales of electric cars have increased quickly in a number of nations, particularly in North America, Europe, and Asia. The existence of official policy backing is one of the elements that determines how well electric cars penetrate the market [

108].

Several African nations are planning to invest significantly in their power industries in the upcoming years. Their goal was to enhance energy accessibility and simultaneously promote environmental sustainability. These findings are supported by various studies conducted by [

109,

110] and [

111]. Furthermore, the African continent is anticipated to have a significant increase in vehicle ownership due to the predicted population growth rate, urbanisation, and widespread aspiration for private car ownership. Therefore, African nations can capitalise on the current worldwide surge in electric vehicle (EV) ownership by adopting an environmentally friendly and cost-effective energy strategy, without committing to carbon-reliant energy infrastructure [

112]. Upon deeper investigation into an accurate portrayal of the African continent, it becomes evident that Nigeria holds the distinction of being the most populated country on the continent. Furthermore, Nigeria’s ownership of vehicles constitutes approximately 8.4% of the overall number of vehicles in operation on the African continent [

34].

The burgeoning population of Nigeria is placing increasing pressure on the country’s infrastructure, transportation, and energy resources, as highlighted by [

113]. The transportation sector in Nigeria relies heavily on petrol and diesel derived from fossil fuels, which is not aligned with long-term climate mitigation efforts [

114]. This transport system also imposes a financial burden on Nigerians and a fiscal burden on the government. The Nigerian federal government (FGN) provides significant subsidies for transportation fuels, particularly for petrol. The Federal Government of Nigeria allocates approximately US

$3.9 billion towards fuel subsidies, an amount that is nearly twice the health budget and equivalent to 2% of the gross domestic product (GDP) [

115].

Numerous studies in the literature have looked into how EVs fit into the energy system’s strategic planning of various countries [

116]. The capacity of EVs to act as a demand management solution is anticipated to be significantly influenced by the EV charging strategy at the national [

117] and local [

118] levels. Other researchers have investigated various aspects of EV commercialisation, including the influence of social class and behaviour [

119], EVs impact on household electricity costs [