1. Introduction

Mineral deposition in the organic matrices of both Mammalians and Chondrichthyes plays a crucial role in skeletal growth, development and function. While calcification can occur in any matrix of living tissues due to degeneration or necrosis Mineral deposition in the organic matrices of both Mammalians and Chondrichthyes plays a crucial role in skeletal growth, development and function. While calcification can occur in any matrix of living tissues due to degeneration or necrosis [

1], cartilage and bone are unique in that their mineral deposition processes are precisely controlled and coordinated with the growth progression and function of the skeletal segments. This control provides the necessary stiffness for protection from the external environment and to meet the mechanical demands of locomotion. Although bone and matrix calcification patterns differ, in both mammals and cartilaginous fishes, skeletal segments differentiate within the median embryonic mesoderm layer. Here, cartilage “anlagen” are formed, with their shape being influenced by the distribution, frequency, and orientation of chondrocyte mitoses before mineral deposition begins [

2,

3,

4]. In the subsequent fetal developmental phase, mineral deposition in the tissue matrix also plays a crucial role in the growth of the cartilage anlage and the final shape of skeletal segments.

Recognizing the homology between fish fins and tetrapod limbs [

5], this study compares the early skeletal development of

Homo sapiens with that of the chondrichthyan

Raja asterias. The choice to morphologically compare two species so distant and evolutionary divergent is motivated by their different limb and fin stiffening patterns, which are adapted to movement on land and in the water column, respectively [

6].

Additionally, supplementary data from dolphin flipper X-rays, reproduced from a previously published study [

7], have been used to examine the effects of the marine environment on the pattern of endochondral ossification. Mammalian embryonic and fetal development is the most extensively studied model compared to all other vertebrates. In contrast, Chondrichthyes, with a much smaller number of species than Osteichthyes, offer a unique opportunity for a comparative histo-morphological analysis of skeletal stiffening patterns, shedding light on the different mechanical requirements of locomotion on land and in the water column.

In a 5-week-old human embryo approximately 1 cm in length, corresponding to stage 16 [

8], the buds of the upper and lower limbs can be observed. Over the next 3-4 weeks, the anatomical positions of the corresponding skeletal segments become identifiable [

9]. For Chondrichthyes development, Maxwell et al. [

10] provided a reference table for stage classification of the skate

Leucoraya ocellata, which was used as a rough reference for the histo-morphological comparison between

H. sapiens and the Batoidea

R. asterias.

Both species exhibit similar modeling of cartilage anlagen before calcification and early mineral deposition in the cartilage matrix, but diverge in the organization of the calcified skeletal framework. Considering the role of natural selection in species evolution, comparing the un-remodeled calcified cartilage with the more prevalent endochondral ossification (in terms of species diversity) can enhance our understanding of the relationship between mechanobiology and the structural evolutionary dynamics of the calcifying skeleton. Relevant data on marine mammals’ skeletal development from the scientific literature were also considered pertinent to this study [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

4. Discussion

Cartilage plays a key role in the ontogeny of the vertebrate skeleton, as this tissue differentiates earlier than bone in the embryo of both fish and mammals, first modeling the shape of skeletal anlagen and then serving as a precursor to endochondral ossification. The first evidence of embryonic tissues adaptation to mechanical requirements is the notochord, whose cells synthetize and store type 2 collagen matrix, which is thought to be a cartilage-type collagen [

2]. This structure is destined to disappear early in the vertebrates, while the skeletal growth in mammals progresses with a combined pattern of periosteal and endochondral ossification until the calcified cartilage scaffold is gradually replaced by bone till the growth ceases. However, among the jawed vertebrates (Gnathostomata Superclass) the class Chondrichthyes has developed a particular adaptive strategy with a growth pattern that differs from the mammal’s endochondral ossification. The first is characterized by the “tessellated” calcification that does not undergoes to remodeling [

24,

25,

26,

27].

The structural adaptation to the mechanical requirements of locomotion has stimulated a remarkable and sustained interest in the bony skeleton of mammalians, from the “Wolff’s Law” [

28,

29,

30] to the most recent computational mechano-biological studies [

31,

32]. Our interest in comparative morphology of skeletal development and growth of mammalians and Batoidea stems from the availability of histological documentation of skeletal growth of

H. sapiens and the un-remodeled calcified cartilage of Rajidae. Earlier morphology studies of

R. asterias pectoral fin radials have documented the following layout in the appendicular skeleton in the medial-lateral direction: a) bi-columnar radials stiffly tied together in the dorso-ventral plane by the two disk plates at the extremities; b) the two columns’ rotation into the horizontal plane at about half of the fin length (made possible by the lateral disk cleavage and by the visco-elasticity of the un-calcified cartilage muff around the calcified columns; c) a complete separation of the medially paired columns enabled by the medial disk further splitting combined with the complete separation of the un-calcified cartilage muff; d) in this way the lateral fin sector is transformed into a more flexible surface of mono-columnar radials [

22]. Therefore, the whole fin works as a mechanical system with a stiff pterygial arc highly movable on the pectoral girdle because of the respective ball-socket and condylar joints, while the large number of aligned radials joined longitudinally by amphiarthroses and connected at the sides by the transversal inter-radial membrane gives a variable flexibility along the fin whole width. The bi-columnar, medial sector provides a stiffer and stronger support for flapping, while the greater pliability of the mono-columnar, lateral sector and the marginal strip of the fin with an internal structure made only by the keratin fibers between the dorsal and the ventral skin assure a major flexibility for the fin undulating movement.

In both mammalians and chondrichthyans the early limb and fin cartilage anlagen (prior to the mineral deposition onset) are modeled by chondrocyte mitoses frequency, zonal density and mitotic spindle orientation [

3,

4], a pattern also confirmed by the observed trend of chondrocytes to arrange themselves in rows [

33,

34,

35]. The columnar arrangement of chondrocytes is much more evident in the mammalian metaphyseal growth plate cartilages, where the columns are densely packed and oriented along the bone longitudinal axis. However, typical chondrocytes rows are also evident in the

R. asterias radials anlagen, which grow independently of a previously established calcified scaffold but with number, density and orientation not so regular as in in the metaphyseal growth plates [

22,

23]. The fundamental difference for what concerns the skeletal development and stiffening between Mammalians and Chondrichthyan fishes is that in the first the calcified cartilage is a provisional tissue whose fate is to be reabsorbed and replaced by bone [

21,

36], whereas in the second it forms the definitive skeletal structure and does not undergo to remodeling.

The mechano-stat theory explains the skeletal framework as an adaptation to the mechanical requirement of static and dynamic loads generated by locomotion on the ground, in the air or in the water column, but no direct evidence has been so far provided to demonstrate how mechanical forces can initiate and control the chondrocytes mitotic activity and the 3-D mineral deposition layout in the cartilage anlagen. In this context, the Chondrichthyes calcifying cartilage provides a peculiar and interesting model of skeletal segments stiffening pattern, that allows to correlate skeletal growth and locomotion mechanics to the genome, evolution and natural selection [

37]. The calcified matrix of the skeleton (cartilage or bone) is characterized not only by the tissue physical properties such as mineral density, crystalline system, hardness, flexibility, but also by the respective vital tissues physiology and metabolism. For what concerns the latter two points, the difference between the bone and calcifying cartilage is that in the first the osteoblasts survive as osteocytes in the expanding calcifying bone matrix mass (by themselves produced) because both the vascular and canalicular systems develop under a coordinated plan between matrix synthesis and mineral deposition [

3,

21,

38]. In contrast, the chondrocytes embedded in the structurally calcified cartilage are less efficiently nourished by the diffusion of interstitial fluids in a collagen type 2 matrix without a canalicular network and can survive due to a less compact texture of the calcified matrix and a scattered presence of non-calcified cartilage zones.

The report of endochondral ossification of dolphin pectoral fins has been included in this article because it provides further evidence of evolutionary adaptations of the skeleton to swimming in marine mammals, which exhibit the same ossification and growth patterns as H. sapiens, but with a higher number of aligned elements in the autopodium that increase the flipper’s buoyancy in water. The comparison with the number of aligned radials of the Batoidea R. asterias is even more significant. While dolphins and humans share the common skeletal developmental pattern of endochondral ossification, R. asterias represents a different evolutionary solution to the requirements of specific aquatic locomotion. By making these comparisons, we can better understand the different strategies that each species uses to optimize their skeletal structures for the mechanical requirements of their particular environment. Thus, the reference to dolphin fins can serve as a useful link between the ossification processes in H. sapiens and cartilage calcification in R. asterias and provide insight into how similar and different evolutionary influences can shape skeletal development in different taxa.

In extant marine mammal clades, radiographs of flipper bones of young and older dolphins have been analyzed to estimate skeletal development and chronological age [

7,

12,

14,

15,

39] to provide data on the reproductive status and population demography of local species. However, these studies provide useful morphological data to highlight and compare the endochondral-ossification evolutionary changes in relation to the marine environment adaptation. Studies on paleontology, phylogenetics and molecular biology have shown that cetaceans share a common heritage with the artiodactyl clades of terrestrial mammals [

40]. Without entering into the evolutionary history of cetaceans, this study develops a comparison of upper appendicular skeletal morphology, growth/development and stiffening patterns between a terrestrial mammalian as

H. sapiens, the chondrichthyan

R. asterias and the marine mammal

T. truncates (referring for the latter to the radiographic images of the flipper skeletal segments recently published by [

7]. Moreover, the same histo-morphology we observed in human cartilage anlagen has been described in the embryonic development of the dolphins’ flipper bones [

14] whose subsequent ossification pattern is disclosed by X-rays images consistent with that of

H. sapiens, but with differences which support the hypothesis of the structural adaptation to the mechanical demand.

The general developmental scheme of the mammalian skeleton with a single bone element in the stylopodium (humerus), two elements in the zeugopodium (radius and ulna), and several elements in the autopodium (carpals, metacarpals and phalanges) is the same as in

H. sapiens, as is the distribution of the ossification centers with one diaphyseal and two epiphyseal on the extremities separated by a transverse radio-transparent line (the metaphyseal growth plate cartilage). This makes it possible to distinguish the still growing elements from those with fused epiphyseal centers (longitudinal growth completed) and also from those at an earlier stage of development, where epiphyseal ossification had not yet begun or was highlighted by a small and shallow calcification. The adaptation of the fin bones to the mechanical requirements of locomotion in the water is documented in today’s dolphin species not only by the reduction in the size of the rays of the autopod digits and the increase in the number of aligned phalanges in the middle rays [

13,

14], but also by a very early cessation of chondrocyte proliferation in the cartilages of the metaphyseal growth plate of the humerus, radius and ulnas, as indicated by the short length of the stylopodium and zeugopodium elements compared to

H. sapiens and other land mammals. These two macroscopic features support the theory of mechanical demand adaptation in the water column. The latter is further strengthened by the comparison with the structure of the pectoral fin of

R. asterias on the other side of the evolutionary scale with the extreme segmentation of the radials, the surface enlargement and the modulated flexibility as well as the reduction of stylopodium and zeugopodium to the pterygial arch.

The development and evolution of the appendicular skeletal elements takes place at different hierarchical levels of biological organization, the first being in the embryo with cartilage differentiation from the mesenchyme and the growth of the anlagen under the genetic control of chondrocyte proliferation, which is the same in both mammalian and Chondrichthyes skeletons. The stiffening of the cartilage is the subsequent step in the adaptation of the tissue to mechanical stress, which is characterized by the deposition of minerals in the organic matrix of the embryonic anlagen of Mammals and Chondrichthyes. The difference between the two classes is that in the former the calcified cartilage is resorbed and replaced by a bone matrix produced by osteoblasts (endochondral ossification), while in the latter the embryonic tissue remains and forms the final fins’ skeletal structure of the fins, whose growth pattern is documented by the “tesseral” morphology of the fin rays of R. asterias.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.P., M.Ra., and M. Re.; methodology, P.Z.; software, P.Z.; validation, F.S., C.M. and G.R.; formal analysis, G.Z.; investigation, F.S.; resources, U.P.; data curation, M.Re.; writing—original draft preparation, U.P., and G.T.; writing—review and editing, U.P., G.T., and F.S.; visualization, G.T.; supervision, U.P.; project administration, M.Ra.; funding acquisition, G.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Histology of the autopodial cartilage anlagen growth of Homo sapiens (hematoxylin-eosin, dec. sections). (A) Mitotic chondrocyte phase with dissolution of the nuclear membrane, doubling of the chromosomes and attachment to the spindle (prophase and metaphase). (B) Migration of the doubled chromosomes towards the spindle poles (anaphase). (C) Duplicated chondrocytes still in a single lacuna. (D) Paired chondrocytes have formed their own lacunae, separated by matrix septa of increasing thickness.

Figure 1.

Histology of the autopodial cartilage anlagen growth of Homo sapiens (hematoxylin-eosin, dec. sections). (A) Mitotic chondrocyte phase with dissolution of the nuclear membrane, doubling of the chromosomes and attachment to the spindle (prophase and metaphase). (B) Migration of the doubled chromosomes towards the spindle poles (anaphase). (C) Duplicated chondrocytes still in a single lacuna. (D) Paired chondrocytes have formed their own lacunae, separated by matrix septa of increasing thickness.

Figure 2.

Histology of the fetal Autopodium of Homo sapiens. (A-B) (hematoxylin-eosin, dec. section) form of the autopodium elements, with incipient mineral deposition in the middle sector of the metacarpals, not yet initiated in the short carpal bone anlagen and in the epiphyses. (C) (Alcian-blue, dec. section) initial phase of mineral deposition with swelling of the chondrocytes (usually referred to as hypertrophy). At this stage there are no signs of epiphyseal calcifying centers forming. (D) (Von Kossa-neutral red, un-dec. section) mineral deposits in the cartilage matrix between the swollen chondrocytes and early mineral deposits in the periosteal bone envelope.

Figure 2.

Histology of the fetal Autopodium of Homo sapiens. (A-B) (hematoxylin-eosin, dec. section) form of the autopodium elements, with incipient mineral deposition in the middle sector of the metacarpals, not yet initiated in the short carpal bone anlagen and in the epiphyses. (C) (Alcian-blue, dec. section) initial phase of mineral deposition with swelling of the chondrocytes (usually referred to as hypertrophy). At this stage there are no signs of epiphyseal calcifying centers forming. (D) (Von Kossa-neutral red, un-dec. section) mineral deposits in the cartilage matrix between the swollen chondrocytes and early mineral deposits in the periosteal bone envelope.

Figure 3.

Histology and primary calcified cartilage matrix resorption in Homo sapiens autopodium metacarpals. (A) (hematoxylin-eosin, dec. section) swollen chondrocytes of the central anlage zone with matrix more densely stained by hematoxylin where mineral deposition occurs. Initial formation of the bone periosteal sleeve (red arrow). (B) (hematoxylin-eosin, dec. section) vascular invasion and reabsorption of calcified cartilage matrix in the central zone of the anlage, while the upper and lower sectors retain the denser colored matrix. Increased thickness of the bone periosteal sleeve (red arrow). (C) (hematoxylin-eosin, dec. section, bar=100 μm) advanced vascular invasion and calcified matrix resorption in the central zone of the anlage. (D) (Von Kossa neutral red, un-dec. section, bar=100 μm) residual calcified cartilage matrix of the central zone and first cortical bone layer of the diaphysis. (E) (hematoxylin-eosin, dec. section) calcified matrix (*), which is resorbed by a multinucleated osteoclast, and chondrocytes embedded in the calcified matrix.

Figure 3.

Histology and primary calcified cartilage matrix resorption in Homo sapiens autopodium metacarpals. (A) (hematoxylin-eosin, dec. section) swollen chondrocytes of the central anlage zone with matrix more densely stained by hematoxylin where mineral deposition occurs. Initial formation of the bone periosteal sleeve (red arrow). (B) (hematoxylin-eosin, dec. section) vascular invasion and reabsorption of calcified cartilage matrix in the central zone of the anlage, while the upper and lower sectors retain the denser colored matrix. Increased thickness of the bone periosteal sleeve (red arrow). (C) (hematoxylin-eosin, dec. section, bar=100 μm) advanced vascular invasion and calcified matrix resorption in the central zone of the anlage. (D) (Von Kossa neutral red, un-dec. section, bar=100 μm) residual calcified cartilage matrix of the central zone and first cortical bone layer of the diaphysis. (E) (hematoxylin-eosin, dec. section) calcified matrix (*), which is resorbed by a multinucleated osteoclast, and chondrocytes embedded in the calcified matrix.

Figure 4.

Histology of (Raja asterias) pectoral fin radials. (A-B) (hematoxylin-eosin, dec. longitudinal section) high density of duplicating chondrocytes within a single lacuna and paired lacunae developing the radial (cylindrical) cartilage anlage. The matrix stained more intensely with hematoxylin corresponds to the zones of impendent mineral deposition that occur along the central axis of the radialis or in correspondence with the inter-radial amphiarthroses. Black arrows indicate the tegument. (C-D) (hematoxylin-eosin, dec., transverse section) swellings of chondrocytes with densely stained matrix reproduce the histological features of mineral deposition of H. sapiens anlagen and show the non-remodeled texture of the calcified cartilaginous skeleton of chondrocytes (left sector of figures).

Figure 4.

Histology of (Raja asterias) pectoral fin radials. (A-B) (hematoxylin-eosin, dec. longitudinal section) high density of duplicating chondrocytes within a single lacuna and paired lacunae developing the radial (cylindrical) cartilage anlage. The matrix stained more intensely with hematoxylin corresponds to the zones of impendent mineral deposition that occur along the central axis of the radialis or in correspondence with the inter-radial amphiarthroses. Black arrows indicate the tegument. (C-D) (hematoxylin-eosin, dec., transverse section) swellings of chondrocytes with densely stained matrix reproduce the histological features of mineral deposition of H. sapiens anlagen and show the non-remodeled texture of the calcified cartilaginous skeleton of chondrocytes (left sector of figures).

Figure 5.

Raja asterias mature specimen of the inter-radial joint (toluidine blue, not declined / embedded in resin, longitudinal section). The joint consists of a layer of connective tissue (#) lying between the two discs (*) of calcified cartilage held by the branches of the central columns of the radialis. In the non-calcified cartilage matrix (weakly stained with toluidine), the tendency of the chondrocytes to align themselves into columns can be seen (arrows).

Figure 5.

Raja asterias mature specimen of the inter-radial joint (toluidine blue, not declined / embedded in resin, longitudinal section). The joint consists of a layer of connective tissue (#) lying between the two discs (*) of calcified cartilage held by the branches of the central columns of the radialis. In the non-calcified cartilage matrix (weakly stained with toluidine), the tendency of the chondrocytes to align themselves into columns can be seen (arrows).

Figure 6.

X-ray image/morphometry of the central sector of the pectoral fin in dorso-ventral projection of an adult specimen of

R. asterias. (

A) The medial and lateral sectors are distinguished by the radials, the two columns of which (superimposed in the dorso-ventral plane) run horizontally approximately halfway along the length of the fin. The radials of the medial sector were numbered from 8 to 1, starting with the radials characterized by the rotation of the columns (reference plane 9 in the diagram). The single-column radials of the lateral sector are doubled and the measurements were made by the homologous radial length sum/2, numbered from 10 to 16 in the direction of the outer edge, while the length of the most apical radials was not measurable in the radiographs. This diagram illustrates the irregular basal row of radial joints in the pterygium, highlighting some columns that are fused to the pterygium (*). The diagonally scaled rows of homologous radials (dotted red lines) reflect the curved profile of the entire fin margin and the gradual reduction in the number of radials in the anterior and posterior parts of the fin (image reproduced from [

6]. (

B) Graph showing the mean length ± standard deviation in the rows of radials 1-8 of the medial fin sector and 10-16 in the lateral sector, while row 9 was the reference plane of the column turn in the horizontal plane.

Figure 6.

X-ray image/morphometry of the central sector of the pectoral fin in dorso-ventral projection of an adult specimen of

R. asterias. (

A) The medial and lateral sectors are distinguished by the radials, the two columns of which (superimposed in the dorso-ventral plane) run horizontally approximately halfway along the length of the fin. The radials of the medial sector were numbered from 8 to 1, starting with the radials characterized by the rotation of the columns (reference plane 9 in the diagram). The single-column radials of the lateral sector are doubled and the measurements were made by the homologous radial length sum/2, numbered from 10 to 16 in the direction of the outer edge, while the length of the most apical radials was not measurable in the radiographs. This diagram illustrates the irregular basal row of radial joints in the pterygium, highlighting some columns that are fused to the pterygium (*). The diagonally scaled rows of homologous radials (dotted red lines) reflect the curved profile of the entire fin margin and the gradual reduction in the number of radials in the anterior and posterior parts of the fin (image reproduced from [

6]. (

B) Graph showing the mean length ± standard deviation in the rows of radials 1-8 of the medial fin sector and 10-16 in the lateral sector, while row 9 was the reference plane of the column turn in the horizontal plane.

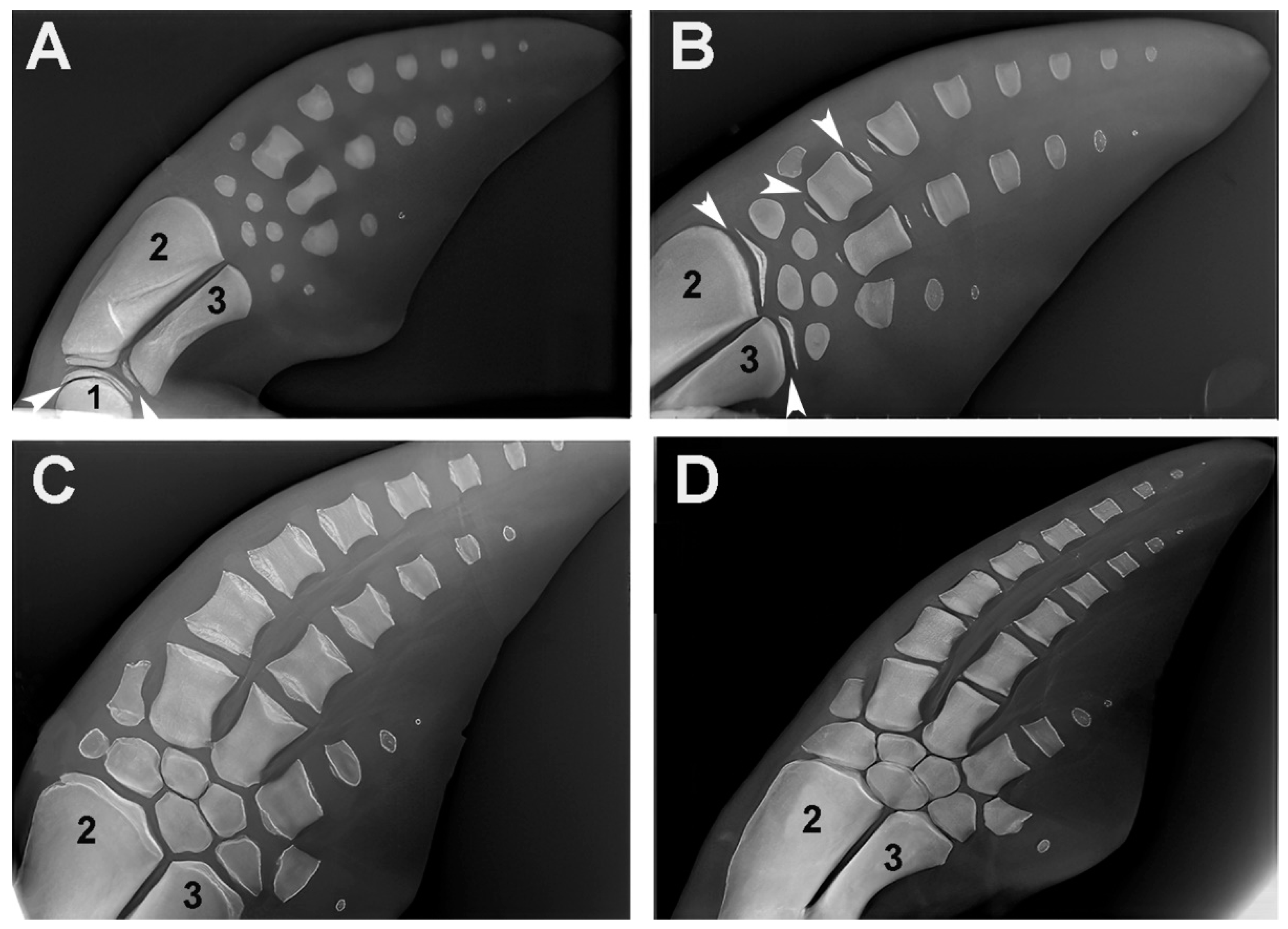

Figure 10.

Growth and ossification pattern of dolphin (

Tursipius truncatus) fins (image reproduced from [

7]. (

A) The stylopodium (1) and the two zeugopodium elements, radius (2) and ulna (3), show the ossified diaphyseal centers with flat epiphyseal ossification centers. The carpus, metacarpus and phalanges each exhibit a single ossification center. (

B) The distal epiphyseal center has also developed in the radius and ulna, the proximal and distal epiphyseal centers in two metacarpals and only the proximal epiphyseal center in the first phalanges. The transverse radio-transparent lines between the diaphyseal and epiphyseal ossification centers correspond to the metaphyseal growth plate cartilage (as in terrestrial mammals) and regulate the longitudinal growth of the skeletal segment. (

C) Recent fusion of the diaphyseal and epiphyseal ossification centers due to a stop of chondrocyte proliferation in the clefts of the metaphyseal growth plate. (

D) Completed growth of the skeleton. The comparison of the lateral and longitudinal diameter of metacarpals and phalanges indicates that the contribution of the metaphyseal plates of marine mammals to the longitudinal growth of the segment is smaller than in terrestrial mammals.

Figure 10.

Growth and ossification pattern of dolphin (

Tursipius truncatus) fins (image reproduced from [

7]. (

A) The stylopodium (1) and the two zeugopodium elements, radius (2) and ulna (3), show the ossified diaphyseal centers with flat epiphyseal ossification centers. The carpus, metacarpus and phalanges each exhibit a single ossification center. (

B) The distal epiphyseal center has also developed in the radius and ulna, the proximal and distal epiphyseal centers in two metacarpals and only the proximal epiphyseal center in the first phalanges. The transverse radio-transparent lines between the diaphyseal and epiphyseal ossification centers correspond to the metaphyseal growth plate cartilage (as in terrestrial mammals) and regulate the longitudinal growth of the skeletal segment. (

C) Recent fusion of the diaphyseal and epiphyseal ossification centers due to a stop of chondrocyte proliferation in the clefts of the metaphyseal growth plate. (

D) Completed growth of the skeleton. The comparison of the lateral and longitudinal diameter of metacarpals and phalanges indicates that the contribution of the metaphyseal plates of marine mammals to the longitudinal growth of the segment is smaller than in terrestrial mammals.

Table 1.

Data of the analyzed Raja asterias.

Table 1.

Data of the analyzed Raja asterias.

| Nr. |

Group |

Sex |

Weight (g) |

Pectoral fins width (cm) |

Total length (cm) |

| 1 |

A |

n.a. |

1.20 |

4.0 |

7.6 |

| 2 |

B |

n.a. |

2.10 |

5.0 |

8.2 |

| 3 |

B |

n.a. |

2.20 |

5.5 |

9.2 |

| 4 |

B |

n.a. |

2.80 |

6.0 |

9.6 |

| 5 |

B |

n.a. |

2.95 |

6.3 |

9.7 |

| 6 |

B |

n.a. |

3.10 |

6.3 |

9.9 |

| 7 |

B |

n.a. |

3.25 |

6.5 |

n.a. |

| 8 |

B |

n.a. |

4.30 |

7.6 |

10.8 |

| 9 |

C |

F |

8.50 |

9.9 |

12.7 |

| 10 |

C |

M |

9.70 |

10.8 |

14.6 |

| 11 |

C |

F |

9.90 |

11.7 |

16.3 |

| 12 |

C |

F |

10.50 |

12.5 |

16.9 |

| 13 |

D |

M |

260.0 |

19.0 |

25.0 |

| 14 |

D |

M |

350.0 |

27.5 |

40.0 |

| 15 |

D |

M |

769.0 |

34.0 |

52.5 |