Introduction

Strengthening plant stress tolerance under unfavorable growing conditions, such as drought, has gained attention with increasing limitations in available resources and unpredictable weather. Phenotypic quantification of drought tolerance has been extremely difficult.

Drought tolerance is the capacity of a plant to tolerate a defined level of internal water status, but few studies have shown genotype differences in plant performance under water-limiting conditions by assessing internal water status such as relative water content or plant tissue water potential.

To assess drought tolerance in field experiments, measuring yield under both well-watered and drought conditions is required, so that yield under drought could be adjusted by taking into account the potential yield under well-watered condition. Similarly, because even a slight variation in phenology affects plant performance in the field, phenological adjustment of yield is needed. The drought response index (DRI) is an indicator of drought tolerance determined in field experiments; a high DRI indicates drought tolerance. DRI is calculated as the portion of variation of grain yield under drought adjusted by yield potential and time of flowering. DRI has been reported in rice [1], pearl millet [2] and chickpea [3]; it may be useful in crop breeding, but its ecophysiological and genetic bases are not sufficiently understood. DRI is effectively used for comparing genotypes with different phenology.

In rice, main-effect QTLs for DRI have been reported on chromosomes 1, 2, 6, 8, 9, and 10 in two types of soil (sandy and paddy) in the population from a paddy rice Zhenshan 97 (indica) and an upland rice IRAT109 (tropical japonica) [4], on chromosomes 7 and 11 in the population from CT9993-5-10-1-M (abbreviated as CT9993), an upland japonica from Colombia and IR62266-42-6-2 (abbreviated as IR62266), a lowland indica from Philippines [5], and on chromosome 12 in the population from Vandana (Aus/japonica) and Way Rarem (the upland cultivars) [6]. However, no report is available in populations obtained from temperate japonica crosses or by comprehensive eco-physiological and genetic assessment of DRI genomic information. Furthermore, it is unclear whether the drought-tolerant yield QTLs (qDTY) and QTLs for DRI are connected to one another [7].

DRI should indicate drought tolerance of a genotype, but different drought tolerance mechanisms might be involved in crop production to different degrees depending on the type of drought [8]. As the duration and intensity of drought stress can vary greatly, the genomic regions for DRI may also interact with drought conditions, but no information is available on QTL-by-environment interaction for DRI.

Drought resistance of rice has been studied using mapping populations, mostly indica × japonica [8] and fewer japonica × japonica, partly because of smaller chances of polymorphism. However, differences in putative drought resistance traits such as root architecture or root anatomy have been reported even within japonica ecotypes [9,10]. Comparing QTLs for DRI of various genetic origins would be possible with the use of mapping populations from temperate japonica parents. Moreover, a considerable number of studies on drought resistance improvement were conducted during late season or early season droughts, such as those in semi-arid tropical regions or Mediterranean climates e.g., [3,52–54]. These conditions differ greatly from mid-season water scarcity in the moderate monsoon environment of Japan e.g., [12].

The current study aimed to explore the genetic basis of DRI by using a mapping population obtained from two temperate japonica cultivars under mid-season upland drought in Japanese temperate monsoon climate conditions. The first objective was to estimate the main-effect QTLs for DRI in this population. The second objective was to estimate QTL-by-environment interaction for DRI. Earlier data on DRI QTLs from other three mapping populations [4–6] were thoroughly analyzed, along with the analysis of potential qDTY.

Materials and Method

Plant Materials

A population of 97 recombinant inbred lines (RILs) of the F8 generation was derived from a cross between two japonica waxy cultivars, lowland Otomemochi (OTM; early maturity) and upland Yumenohatamochi (YHM; intermediate maturity), at the Plant Biotechnology Institute, Ibaraki Agricultural Center, Japan. OTM has a short stature, is resistant to rice blast, and is drought susceptible, whereas YHM has a deeper root system, is drought resistant, and is well adapted to upland conditions [11–13].

Experimental Condition

The experiments were conducted in upland fields at the Institute for Sustainable Agro-ecosystem services, The University of Tokyo (U Tokyo ISAS), Nishitokyo, Japan (35 °43′ N, 39 °32′ E), from late April to early November in 2011 (Experiment 1) and 2012 (Experiment 2) (

Table S1). The soil was a volcanic ash soil of the Kanto loam type (humic Andosol). The progeny and the two parental cultivars of the mapping population (OY population) were planted in both irrigated and drought fields, each of which had three replications of an 11 × 11 Latin square design with the two parents at least once in each row and column (11 replications).

The drought field was covered by a polyvinyl rainout shelter to exclude rainfall (

Figure S1). The drought continued from 5 July to 3 September in Experiment 1 (60 days, very severe drought) and from 19 July to 2 September in Experiment 2 (45 days, severe drought). Crops were rewatered and recovered from drought. In the control fields, irrigation was provided 12 times, in total 150 mm in Experiment 1 and 175 mm in Experiment 2 during the drought.

Growth Conditions

Maximum and minimum daily air temperatures, total daily solar radiation, and daily rainfall (

Figure S2) were measured by a weather station (WatchDog 2900ET, Spectrum Technologies Inc., Aurora, IL, USA) installed at the side of the field. Average daily solar radiation from May to October was 11.6 ± 5.3 MJ m

−2 in Experiment 1 and 16.0 ± 6.8 MJ m

−2 in Experiment 2.

The daily minimum and maximum air temperatures were 19.5 ± 4.9 °C (mean ± standard deviation) and 28.8 ± 5.7 °C, respectively, in Experiment 1, and 19.3 ± 4.7 °C and 29.2 ± 5.3 °C in Experiment 2 (

Figure S1a, b). The total amount of rainfall was 926 mm in Experiment 1 and 916 mm in Experiment 2.

In Experiment 1, seeds were soaked in cups on 23 April 2011, transferred to a nursery box on 28 April, and transplanted on 22 May (

Table S1). Hill spacing was 20 cm × 20 cm. Basal fertilizer (12% N, 16% P

2O

5, 18% K

2O) and calcium silicate were applied at 50 and 100 g/m

2, respectively, on 13 May, and urea fertilizer was applied at 4.3 g /m

2 on 3 July.

In Experiment 2, seeds were soaked on 24 April 2012, transferred on 1 May, and transplanted on 25 May as in Experiment 1. Fertilizers were applied as in Experiment 1, with urea was applied on 5 July.

Measurements to Determine Drought Intensity

Soil Water Conditions

We used a time-domain reflectometer (TDR, FieldScout TDR 300 moisture meter, Spectrum Technologies, Inc.) at a depth of 0–12 cm to monitor the soil volumetric water content (VWC) around the panicle initiation and flowering stages in both years. TDR readings were calibrated with VWC (%) obtained from the core sampling of the soils in the same zone:

Soil water potential at 10 and 40 cm soil depth was measured by tensiometers (DIK 8333, Daiki Rika Kogyo Co. Ltd, Saitama, Japan) in drought and control fields.

Relative Water Content of the Leaf Blade

The relative water content (RWC) of the leaf blade was calculated as:

where FW is fresh weight, TW is turgid fresh weight, and DW is dry weight of the samples. A single leaf from each parent was collected between 0600 and 0900 on 7 August from both drought and control fields. The sampled leaves were immediately weighed in the field to determined FW, then wrapped immediately in zip lock covers, placed in an ice box to minimize respiration loss, and quickly carried to a refrigerator in the laboratory. They were stored in deionized water overnight in the fridge (4 °C), water was gently removed from the leaf surface, and the leaves were weighed to determine TW. The leaves were oven dried for 3 days at 80 °C to determine DW.

Phenotypic Evaluation

Flowering date was determined by daily monitoring as the date when about half of the panicles were flowering. Flowering delay under drought in comparison with the control was calculated for each genotype in each replication. Leaf rolling and drying scores under drought ranged from 1 (no leaf rolling/drying) to 9 (complete rolling and drying of all leaves on a plant) according to the Standard Evaluation System (SES) of Rice [14]. Plant height was recorded, and its reduction under drought in comparison with the control was also calculated. At maturity, one plant per replication was harvested and oven dried at 80 °C for 2–3 days to determine grain and aboveground dry weights per hill. Grain dry weight was calculated per area and used as a proxy for grain yield. In Experiment 1, grain dry weight was determined separately for panicles emerging before rewatering and after rewatering. Root dry weight was determined only in Experiment 1.

The drought response index (DRI) was used as a measure of the magnitude of genotypic response; the grain yield of each genotype under drought was adjusted for flowering date and potential yield of the respective control. DRI was calculated [2,15] as:

where

Yact is the actual grain yield of each line in each replication under drought,

Yest is the estimated grain yield of each line, and SD of

Yest is the standard deviation of estimated grain yield of all lines.

Yest was derived by multiple regression as:

where (

Yp)

i is the potential grain yield in the control, (FL)

i is the time to 50% flowering in the control, and

a,

b,

c are the regression parameters.

Phenotypic Data Analysis

Phenotypic data were analyzed by both general ANOVA and an unbalanced design taking row–column effects into account according to the Latin square design (GenStat 16.0). Parental values were compared by Duncan’s multiple range test (significance at P < 0.05).

QTL Analysis

The genetic map of the OY population was established at the Plant Biotechnology Institute, using 106 simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers to genotype the 212 RILs [16]. Composite interval mapping was conducted in QTL Cartographer v. 2.5 software [17] for each year and both years combined. Putative QTLs with LOD scores >2.5 (P = 0.05; 1000 permutations) were selected. The linkage map with the QTL locations was constructed in MapChart v. 2.32 software [18]. QTL-by-environment interaction was analyzed in QTLMapper v. 1.6 software [19] to compare the additive and additive-by-environment interaction effects.

Comparison between Top- and Bottom-DRI Progeny

Top- and bottom-DRI lines (10 each) were marked in each year and in combined average, and overall 10 lines were selected. Lines with top DRI in one year but negative and low values in the other year were rejected. A t-test was conducted between the two groups for phenology, growth and productivity traits, leaf rolling, and root dry weight change from the control to drought in Experiment 1. The population was phenotyped for root vascular traits such as stele transversal area (STA) and its proportion to root transversal area (%STA) [20]. These root vascular traits were also compared between the two groups.

Review of Rice DRI QTL Papers

We extracted the experimental conditions, chromosomal regions, and allelic contributions reported in three papers on QTLs for DRI in rice [4–7,21,56–59,62]. QTL positions from different studies were clarified by using the Gramene database (

https://archive.gramene.org/markers/), although only approximate positions could be identified. Collocation of previously reported QTLs for yield under drought [7] and meta-QTLs for drought response [21] were analyzed.

Selection of Putative Genes for Drought Resistance

Results

Soil Water Conditions and Relative Water Content of the Leaf Blade

In Experiment 1, VWC declined to 19.3% ± 1.7% (N = 170) on 31 August. In Experiment 2, it was maintained at 49% in the control, but declined to 28% under drought. Soil moisture content in the drought trial increased to 42% after rewatering but did not reach the control value.

At 41 days of drought in 2011 (15 August), RWC was 93% ± 2% for OTM and 88% ± 2% for YHM in the control, and 68% ± 2% for OTM and 75% ± 11% for YHM under drought. At 41 days of drought in 2012 (29 August), RWC was 83% ± 3% for OTM and 83% ± 1% for YHM in the control, and 67% ± 6% for OTM and 75% ± 12% for YHM under drought.

Phenotypic Analysis

Grain Dry Weight and Drought Response Index

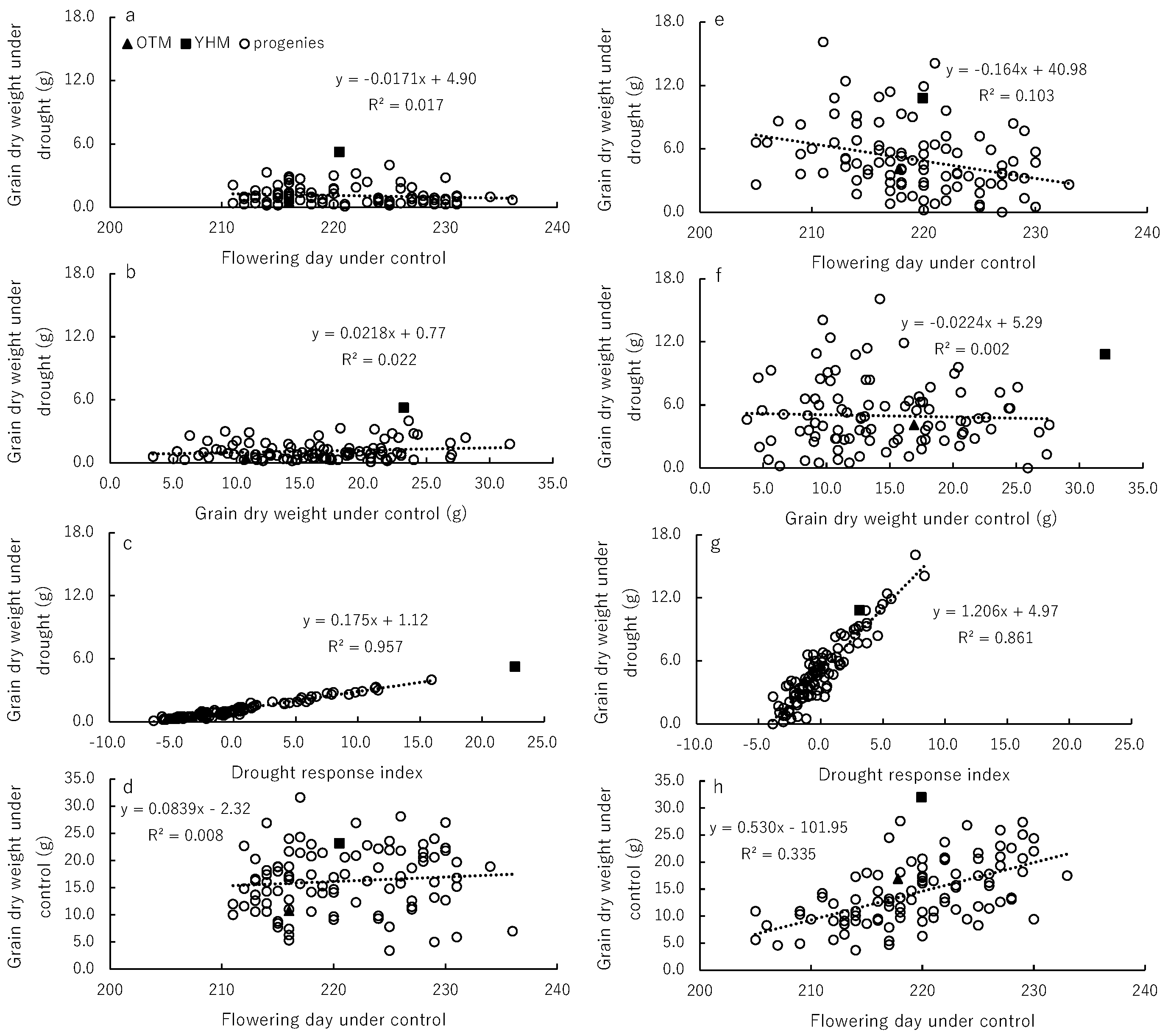

In Experiment 1, grain dry weight under drought was not related to either 50% flowering date in the control (

Figure 1a) or grain dry weight in the control (Fig 1b), but was strongly positively related to DRI (

Figure 1c). DRI was −3.6 for OTM and 22.6 for YHM, and −6.4 to 15.9 for their progeny (

Table 1). Grain dry weight in the control was related to 50% flowering date in the control (

Figure 1d) because of the poor grain filling of a few late-flowering progeny.

In Experiment 2, grain dry weight under drought was negatively related to 50% flowering date in the control (

Figure 1e) but not to grain dry weight in the control (

Figure 1f). Grain dry weight under drought was strongly positively related to DRI (

Figure 1g). DRI was −1.26 for OTM and 3.61 for YHM, and −3.9 to 8.3 for their progeny (

Table 1). Grain dry weight in the control was related to 50% flowering date in the control (

Figure 1h).

Genomic Analysis

Main-Effect QTLs for DRI

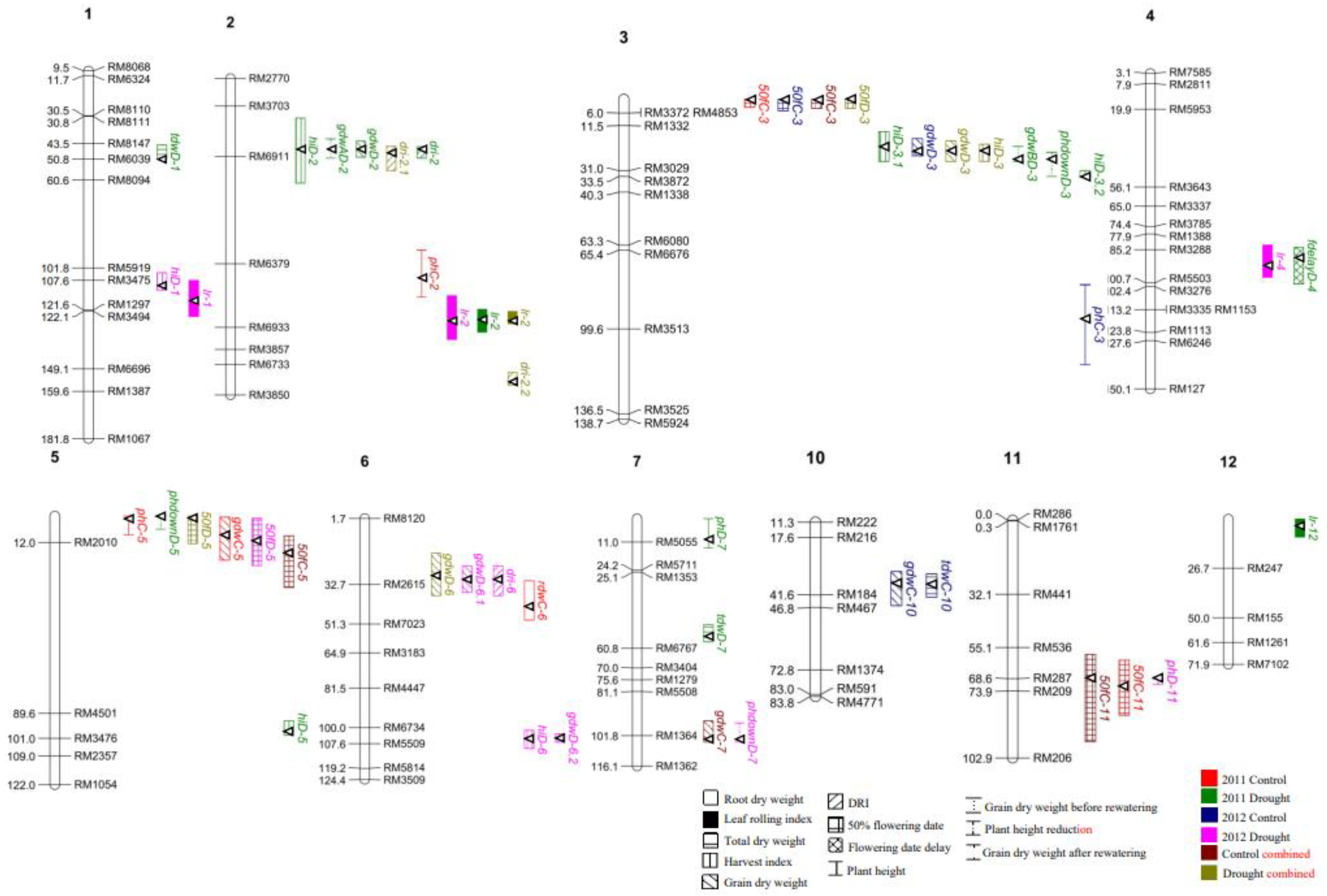

In Experiment 1, 22 main-effect QTLs (control, 6; drought, 16), in Experiment 2, 16 QTLs (control, 4; drought 12), and in combined analysis, 12 QTLs (control, 4; drought, 8) were identified (

Table S2). Among the 20 key genomic regions (

Figure 2), the following regions repeatedly showed the QTLs for production traits; RM1332–RM3029 on chromosome 3 collocated with QTLs for grain dry weight and harvest index under drought; with their positive allelic effects from YHM (

Table S2). RM216–RM467 on chromosome 10 collocated with QTLs for grain and total dry weight in the control, with their positive allelic effects from YHM. QTLs for leaf rolling score were found in RM3475–RM1297–RM6696 on chromosome 1 (Experiment 2), in RM6379–RM6933–RM3857 on chromosome 2 (both years and the combined analysis), in RM1388–RM5503 on chromosome 4 (Experiment 2), and in the short arm tip (~)–RM247 on chromosome 12 (Experiment 1). QTLs for 50% flowering date were found in ~–RM4853 on chromosome 3, in ~–RM4501 on chromosome 5, and in RM536–RM206 on chromosome 11.

QTLs for DRI were identified in three genomic regions (

Table 3,

Figure 2): (1) RM3703–RM6911–RM6379 on chromosome 2 (Experiment 1 and combined analysis), collocated with QTLs for grain dry weight after rewatering, grain dry weight, and harvest index in Experiment 1; (2) RM6733–RM3850 on chromosome 2 (combined analysis); and (3) RM8120–RM7023 on chromosome 6 (Experiment 2), collocated with QTLs for grain dry weight under drought (Experiment 2 and the combined analysis) and root dry weight in the control (Experiment 1).

QTL-by-Environment Interaction

The additive effect was higher for the QTL-by-environment interaction (0.16) than for the putative QTLs (0.08) for DRI (

Table 4), but the main effect was higher for 50% flowering date and leaf rolling. In spite of minor differences, the QTLs detected in each experiment were mostly consistent with those from the combined analysis.

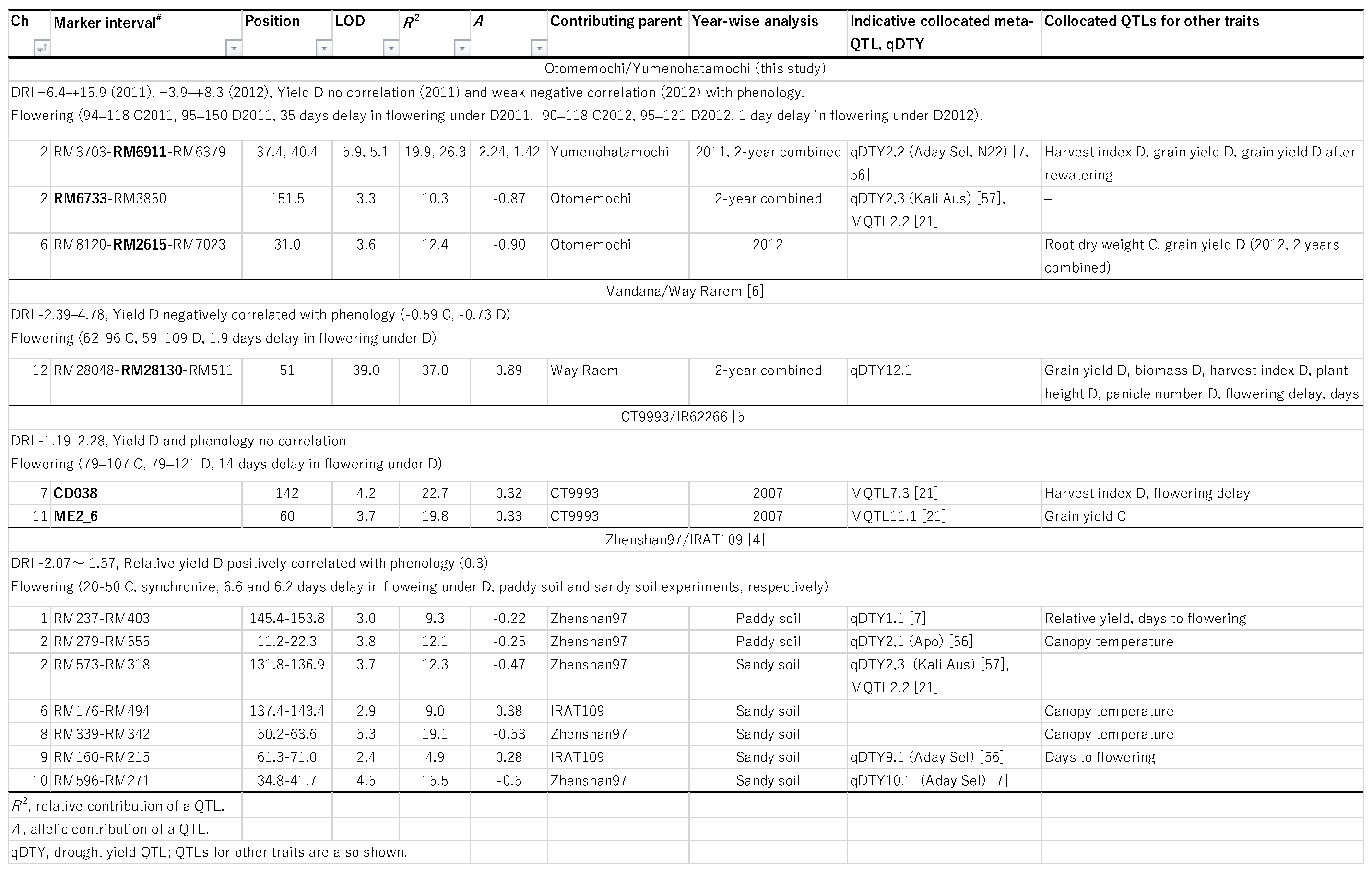

Review of Previous Studies on QTLs for DRI

We also analyzed the published data on QTLs for DRI in the crosses of Vandana/Way Rarem [6], CT9993/IR62266 [5], and Zhenshan 97/IRAT109 [4]. The effect of flowering time on grain yield under drought differed among the studies. For DRI, 7 QTLs (2 in paddy soil and 5 in sandy soil [4]) and 1 to 3 QTLs [5,6] have been identified. RM6733–RM3850, the second region on chromosome 2 in OTM/YHM, was relatively close to RM573–RM318 on chromosome 2 in Zhenshan 97/IRAT109; these are possibly collocated with a QTL for grain yield under drought, qDTY2,3. However, all the other reported QTLs were specific to each study and each population. Interestingly, a QTL on chromosome 12 [6] was collocated with the drought yield QTL on chromosome 12, qDTY12,1, and some other QTLs for DRI were found to be located close to the drought yield QTLs.

Table 6.

Genomic information of main effect QTLs for drought response index (DRI) in 4 rice mapping populations (our study and [4–6]).

Table 6.

Genomic information of main effect QTLs for drought response index (DRI) in 4 rice mapping populations (our study and [4–6]).

Putative Genes for Drought Resistance

Within the markers flanking the 3 key genomic regions for DRI, putative genes related to plant growth, grain development, or drought responses were selected from the databases (

Table 7). In the first region on chromosome 2,

GW2 encodes a RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligase, which decreases grain width and weight [22,23].

EP3 encodes a protein that controls erect panicle and its branching, as well as culm mechanical strength [24,25].

OsGTE4 encodes a bromo-domain-containing protein homologous to Arabidopsis GTE4, which maintains root meristem and regulates cell cycle [26–28].

AIM1 encodes 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase, which maintains root meristem activity [27,29,31].

RPBF [30,31] and

PYL/RCAR3 [32] encodes a transcription factor and

PYL/RCAR3 [32] encodes an abscisic acid (ABA) receptor.

In the second region on chromosome 2, MGD2 encodes monogalactosyldiacylglycerol synthase, which enhances salt, drought, and submergence stress tolerance [33]. PIP1;3 encodes a plasma membrane intrinsic protein, which promotes plant tolerance to water deficit [34, 35]. SMG1 encodes mitogen-activated protein kinase 4 involved in defense response, cell proliferation, and grainn growth [36,37]. LGS1 encodes a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, which regulates grain size [38,39]. BLS1 encodes DUF640 and ALOG domain-containing protein, which regulates plant height, floral development, grain yield, and spikelet morphogenesis [40,41]. LKR/SDH encodes lysine ketoglutarate reductase/saccharopine dehydrogenase in developing grain [30,31].

In the third region (chromosome 6), BZIP46 encodes a bZIP transcription factor, which promotes ABA signaling and drought tolerance [42,43]. P1N1B encodes PIN protein, which is an auxin efflux carrier involved in auxin transport and signaling and in the development of root, shoot, and inflorescence [44,45]. KRP2 encodes cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2 [46]. SK2 encodes shikimate kinase 2, involved in defense response and panicle development [47,48]. MADS55, which encodes a short vegetative phase (SVP)-group MADS-box protein [49], and BU1 [50,51], both regulate plant development through brassinosteroids.

Discussion

Phenotypic Assessment of DRI

This study tested DRI in a japonica × japonica mapping population in two 1-year field experiments with severe or very severe drought during the reproductive stage up to flowering (July to early September). The rainfall at the study site is generally sufficient during the rice vegetative stage (before early July) and after flowering (from early September). Owing to the extreme severity of the imposed drought, no significant link was detected in Experiment 1 between grain dry weight under drought and the 50% flowering date, nor between the grain dry weights under drought and in the control. The reduction in yield was greater in Experiment 1 than in Experiment 2 because of its extended period of very severe drought. We found that the plant capacity to respond to rewatering was positively correlated with both DRI and grain dry weight under drought; this capacity was expressed as grain dry weight derived from panicles formed after rewatering. This is the first demonstration of a link between DRI and the capacity to respond to rewatering. Prior DRI research on rice was carried out in semi-arid tropics during late-season drought, where phenology accounted for a larger portion of the fluctuation in yield during drought [1,52–54]. Our study site is located in a temperate monsoon climate, with drought mainly from mid-July to late August; in September, when many lines and cultivars were in the middle of the grain filling period, water supply was good. Experiment 1 revealed that the recovery capacity following rewatering was more important than phenology.

Genotype rankings of neither DRI nor grain dry weight under drought were consistent in 2 years, showing genotype-by-year interaction. The DRI range among the progeny was larger in Experiment 1 (from −6.4 to +15.9) than in Experiment 2 (from −3.9 to +8.3). A genotype-by-drought environment interaction has been reported for DRI [52,53]. However, the existence of genotypes with consistently high DRI was reported [1,55], and hence it is possible to select a few progeny with consistently high DRI. Such genotypes should have consistently high harvest index and associated traits for yield formation. Such efforts may gradually attain superior rice genotypes under drought-prone upland environments.

Genetic Assessment of DRI with QTLs for Other Yield-Related Traits and Drought Resistance Genes

In the temperate

japonica population, three genetic sites (two on chromosome 2 and one on chromosomes 6) for DRI QTLs affecting field drought tolerance were identified for the first time. Both regions on chromosome 2 were collocated with either the reported DRI QTL [4] or drought yield QTLs qDTY

2,2 [7,56] and qDTY

2,3 [57]. QTLs for DRI and yield under drought can be considered as genetic bases for field drought tolerance, and collocation of the QTL for DRI and qDTY

12,1 on chromosome 12 have been reported [6]. However, qDTYs could be still linked to phenology, as in the case of DTY

2,1 and qDTY

2,2 [58,59]. Since the DRI equation takes into account and minimizes influences of both phenology and yield potential, genetic analysis of DRI could be more useful as an indicator of drought tolerance and may supplement direct investigation of qDTYs. The third region (chromosome 6) was uniquely identified in the temperate

japonica population in this study. This uniqueness may be related with the different combinations of rice ecotypes (

Table 6) together with the different experimental settings including yield level, yield–phenology interaction, and drought intensity and duration.

The effects of these three genomic regions on responses to different stress intensities were assessed. The first region on chromosome 2 was detected in Experiment 1 and in the combined data; the YHM allele had a positive contribution. Together with more productive panicles and grains (data not shown), the QTL collocation suggested that this region controls drought resistance by improving drought recovery after rewatering, maintaining greater harvest index and yield under drought. This region was adjacent to a large-effect QTL for yield under drought, RM236–RM555 (qDTY

2,2; Aday Sel × IR64 population under both lowland and upland drought [7,56]). A somewhat close but differently located QTL for DRI, RM279–RM555, has been found (

indica Zhenshan 97 ×

tropical japonica IRAT109 under severe drought [4]), which is close to another large-effect QTL for yield under drought, RM3549–RM324 (qDTY

2,1; Swarna × Apo population under lowland drought [56]). This region encodes stress-responsive transcription factors such as RPBF, a Dof zinc finger transcriptional activator and transcription factor [30,31], and PYL/RCAR3, a pyrabactin resistance-like (PYL) ABA receptor family protein with cold and drought stress tolerance [32], as well as GW2, a negative regulator of grain width and size [22,23]) (

Table 7). In Experiment 1, recovery of the capacity to produce grains after rewatering may have overridden the effect of drought.

In the same region, a QTL for root vascular traits was identified in the OY population [20]. STA and % STA of roots are important for maintenance of leaf water potential and grain yield under water-limiting conditions [60]; they were larger in the 10 top-DRI lines than in the 10 bottom-DRI lines. The 10 top-DRI lines showed superior drought response to the 10 bottom-DRI lines through incremental root growth under drought, less leaf rolling, and less reduction in yield. Genes to maintain root meristem activity such as OsGTE4 and AIM1 were identified in this region [26,27]. Stele size measured under upland water-limiting conditions may be important as a drought adaptation. Stele size may be to some extent constitutive, but responsive to water deficit and depends on genotype. A drought resistance gene, DROUGHT1, is expressed in vascular bundles within stele; it is directly repressed by ERF3 and activated by ERF71 in rice (both drought-responsive transcription factors), which could adjust cell wall structure by increasing cellulose content and maintaining cellulose crystallinity [61].

The second region for DRI on chromosome 2 was collocated with a QTL for DRI detected in the Zhenshan 97 × IRAT109 population in RM573–RM318 under mild drought [4]. This region was also collocated with qDTY2,3, a QTL for yield under drought in the Kali Aus × IR64 population [57]. This region had its allelic contribution from OTM and Zhenshan 97, the drought-susceptible lowland parents. It includes stress-tolerance and stress-responsive genes for defense such as MGD2 [33] and PIP1;3 [34,35], and genes for grain growth such as LKR/SDH [30], SMG1 [36,37], LGS1 [38,39], and BLS1 [40,41]. Three QTLs for yield under drought on chromosome 2 [7,56,57,62] and 2 meta-QTLs (107.52 cM, MQTL 2.1; 132.4 cM, MQTL 2.2) for drought response have been reported on chromosome 2 [21]. MQTL 2.1 (319 genes) encodes proteins involved in protein phosphorylation, DNA integration, and RNA-dependent DNA biosynthesis, and a locus linked to ABA and mitochondrion termination factor (MTERF). MQTL 2.2 (19 genes) includes 5 genes for water transport (e.g., aquaporins PIP1 and PIP2) and isoprenoid biosynthesis (i.e., heterodimeric geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase small subunit protein). These might be candidate genes for the two putative QTLs for DRI on chromosome 2 in the OY population under severe upland drought conditions in this study.

The third region for DRI (chromosome 6) was collocated with QTLs for grain dry weight under drought and root dry weight under control, with OTM allelic contribution. This region was not close to the reported QTL for DRI on chromosome 6 [4]. QTLs for root number, root-to-shoot ratio, and index of drought resistance (defined as yield under drought relative to those in lowland treatments) have been reported in the IRAT109 × Yuefu population (tropical japonica and temperate japonica) in upland conditions [63]. Two meta-QTLs for root traits (25.86 cM) and for yield and flowering (33.84 cM) have been identified [21] relatively close to this region. Putative genes for defense (e.g., KRP2, SK2), signaling (BZIP46, P1N1B), and development associated with brassinosteroids (e.g., MADS55, BU1), a bZIP transcription factor gene that positive regulates ABA signaling and drought tolerance (BZIP46) [42,43], and a PIN protein gene for auxin transport and signaling for root development (PIN1B) [44,45], are located in this region. A transcription factor for tolerance to phosphate starvation, OsPTF1, increases rice phosphorus content [64]; as drought could lead to the immobilization of phosphate in soils, this region might be linked to better uptake or utilization of phosphate. Genes/QTLs for heading and flowering dates (e.g., Hd-3, qFL-6, RFT1) have been also identified near this region [65–67]. This region was identified only in Experiment 2; it contained genes involved in the regulation of drought-responsive hormones, such as auxin, ABA, and brassinosteroids. The nexus of these genes to drought tolerance traits would be anticipated.

The putative genes in the three DRI regions encode proteins with the functions of (1) enhancing cell defense or (2) signal transmission such as plant hormone signaling or transcription factors, and (3) regulating spikelet and grain development (

Table 7). The QTL for DRI found on chromosome 2 under severe water deficit collocated with several genes regulating grain development. Varying the magnitude of drought severity may lead not only to the identification of different genomic regions but also different categories of drought-tolerance genes. Detection of year-specific QTLs for DRI (the first region for severe prolonged drought, the third one for shorter drought) suggests that different genomic regions may be important depending on the environmental conditions. The third QTL associated with root traits may be linked to the mechanisms of resource acquisition (see [8]), which would be possible under short drought but not under very prolonged drought. The larger effect of QTL-by-environment interaction than the additive effect also supports the importance of drought severity. The additive effect was largest in the first region (2.24, 19.9% of PVE, Experiment 1; 1.42, 26.3% of PVE, combined) followed by the second region (−0.87, 10.3%) and the third region (−0.9, 12.4%). This is understandable, since the effects of drought tolerance are larger as the stress becomes more severe, as in Experiment 1. The difference in drought intensity is likely to affect DNA transcription and RNA translation, and a number of microRNAs (small noncoding regulatory RNAs that modulate gene expression during abiotic stress) have been identified that mediate drought resistance in rice [62,68]. The importance of QTL-by-environment interaction for maize shoot and root growth under well-watered and drought environments has been also reported [69]. This study demonstrates the complexity of field drought tolerance and opens up new possibilities for the genetic analysis of DRI in rice.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Acknowledgments

Seeds of the Otomemochi × Yumenohatamochi population were provided by Mr Tohru Manabe, Ibaraki Agricultural Center. The experimental fields were prepared by technical staff of ISAS, Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, University of Tokyo. This study was supported by a Grant in-Aid for Scientific Research (No. 23380011) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ouk, M.; Basnayake, J.; Tsubo, M.; Fukai, S.; Fischer, K.S.; Cooper, M.; Nesbitt, H. Use of drought response index for identification of drought tolerant genotypes in rainfed lowland rice. Field Crops Res. 2006, 99, 48–58. [CrossRef]

- Bidinger, F.; Mahalakshmi, V.; Rao, G. Assessment of drought resistance in pearl millet (Pennisetum americanum (L.) Leeke). II. Estimation of genotype response to stress. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1987, 38, 49–59. [CrossRef]

- Silim, S.N.; Saxena, M.C. Adaptation of spring-sown chickpea to the Mediterranean Basin. I. Response to moisture supply. Field Crops Res. 1993, 34, 121–136. [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.; Xiong, L.; Xue, W.; Xing, Y.; Luo, L.; Xu, C. Genetic analysis for drought resistance of rice at reproductive stage in field with different types of soil. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005, 111, 1127–1136. [CrossRef]

- Sellamuthu, R.; Liu, G.F.; Ranganathan, C.B.; Serraj, R. Genetic Analysis and validation of quantitative trait loci associated with reproductive-growth traits and grain yield under drought stress in a doubled haploid line population of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Field Crops Res. 2011, 124, 46–58. [CrossRef]

- Bernier, J.; Kumar, A.; Ramaiah, V.; Spaner, D.; Atlin, G. A Large-effect QTL for grain yield under reproductive-stage drought stress in upland rice. Crop Sci. 2007, 47, 507–518. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Dixit, S.; Ram, T.; Yadaw, R.B.; Mishra, K.K.; Mandal, N.P. Breeding high-yielding drought-tolerant rice: genetic variations and conventional and molecular approaches. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 6265–6278. [CrossRef]

- Kamoshita, A.; Babu, R.C.; Boopathi, N.M.; Fukai, S. Phenotypic and genotypic analysis of drought-resistance traits for development of rice cultivars adapted to rainfed environments. Field Crops Res. 2008, 109, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Lafitte, H.R.; Champoux, M.C.; McLaren, G.; O’Toole, J.C. Rice root morphological traits are related to isozyme group and adaptation. Field Crops Res. 2001, 71, 57–70. [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, H.; Kamoshita, A.; Manabe, T. Genetic analysis of rooting ability of transplanted rice (Oryza sativa L.) under different water conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 309–318. [CrossRef]

- Hirasawa, H.; Nemoto, H.; Suga, R.; Ishihara, M.; Hirayama, M.; Okamoto, K.; Miyamoto, M. Breeding of a new upland rice variety ‘Yumenohatamochi’ with high drought resistance and good eating quality. Breed. Sci. 1998, 48, 415–419. [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Abe, J.; Kamoshita, A.; Yamagishi, J. Genotypic variation in root growth angle in rice (Oryza sativa L.) and its association with deep root development in upland fields with different water regimes. Plant Soil 2006, 287, 117–129. [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Kamoshita, A.; Yamagishi, J.; Imoto, H.; Abe, J. Growth of rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars under upland conditions with different levels of water supply 3. root system development, soil moisture change and plant water status. Plant Prod. Sci. 2007, 10, 3–13. [CrossRef]

- IRRI. Standard Evaluation System (SES) for Rice, International Rice Research Institute, 2002.pp56. http://www.knowledgebank.irri.org/images/docs/rice-standard-evaluation-system.pdf (retrieved on 23 March 2024).

- Bidinger, F.R.; Mahalakshmei, V.; Talukdar, B.S.; Alagarswamy, G. Improvement of drought resistant in pearl millet. In: Drought Resistance in crops with emphasis on rice. 1982, IRRI, Los Banos, Philippines, 357-375.

- Manabe, T.; Hirayama, M.; Miyamoto, M.; Okamoto, K.; Okano, K.; Ishii, T. Mapping of quantitative trait loci associated with deep root dry weight in rice. In: Proceedings of the 10th International Congress of SABRAO 2005, Tsukuba, Japan, 22–23 August 2005; D-18.

- Wang, S.; Basten, C. J.; Zeng, Z. B. Windows QTL Cartographer 2.5, 2012. Department of Statistics, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC. (http://statgen.ncsu.edu/qtlcart/WQTLCart.htm).

- Voorrips, R.E. Mapchart: Software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J. Hered. 2002, 93, 77–78. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.L.; Zhu, J.; Li, Z.K.; Paterson, A.H. Mapping QTLs with epistatic effects and QTL × environment interactions by mixed linear model approaches. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1999, 99, 1255–1264. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. H. A.; Kamoshita, A.; Ramalingam, P.; Y, P. Genetic analysis of root vascular traits in a population from two temperate japonica rice ecotypes. Plant Prod. Sci. 2022, 25, 320–336. [CrossRef]

- Selamat, N.; Nadarajah, K.K. Meta-analysis of quantitative traits loci (QTL) identified in drought response in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plants 2021, 10, 716. [CrossRef]

- Song, X.J.; Huang, W.; Shi, M.; Zhu, M.Z.; Lin, H.X. A QTL for rice grain width and weight encodes a previously unknown RING-Type E3 ubiquitin ligase. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 623–630. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Segami, S.; Horikawa, M.; Chaya, G.; Kitano, H.; Iwasaki, Y.; Miura, K. Gw2 mutation increases grain width and culm thickness in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Breed. Sci. 2020, 70, 456–461. [CrossRef]

- Piao, R.; Jiang, W.; Ham, T.H.; Choi, M.S.; Qiao, Y.; Chu, S.H.; Park, J.H.; Woo, M.O.; Jin, Z.; An, G.; et al. Map-based cloning of the ERECT PANICLE 3 gene in rice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009, 119, 1497–1506. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Tang, D.; Wang, K.; Wu, X.; Lu, L.; Yu, H.; Gu, M.; Yan, C.; Cheng, Z. Mutations in the F-Box gene LARGER PANICLE improve the panicle architecture and enhance the grain yield in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2011, 9, 1002–1013. [CrossRef]

- Coudert, Y.; Bès, M.; Van Anh Le, T.; Pré, M.; Guiderdoni, E.; Gantet, P. Transcript profiling of Crown Rootless 1 mutant stem base reveals new elements associated with crown root development in rice. BMC Genomics 2011, 12, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhao, H.; Ruan, W.; Deng, M.; Wang, F.; Peng, J.; Luo, J.; Chen, Z.; Yi, K. ABNORMAL INFLORESCENCE MERISTEM 1 functions in salicylic acid biosynthesis to maintain proper reactive oxygen species levels for root meristem activity in rice. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 560–574. [CrossRef]

- Airoldi, C.A.; Della Rovere, F.; Falasca, G.; Marino, G.; Kooiker, M.; Altamura, M.M.; Citterio, S.; Kater, M.M. The Arabidopsis BET bromodomain factor GTE4 is involved in maintenance of the mitotic cell cycle during plant development. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 1320–1334. [CrossRef]

- Richmond, T.A.; Bleecker, A.B. A defect in β-oxidation causes abnormal inflorescence development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 1999, 11, 1911–1923. [CrossRef]

- Kawakatsu, T.; Takaiwa, F. Differences in transcriptional regulatory mechanisms functioning for free lysine content and seed storage protein accumulation in rice grain. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010, 51, 1964–1974. [CrossRef]

- Goto, F.; Yoshihara, T.; Shigemoto, N.; Toki, S.; Takaiwa, F. Iron fortification of rice seed by the soybean Ferritin gene. Nat. Biotechnol. 1999, 17, 282–286. [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Lv, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Niu, H.; Bu, Q. Characterization and functional analysis of Pyrabactin resistance-like abscisic acid receptor family in rice. Rice 2015, 8. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Yamauchi, Y.; Ling, J.; Kawano, N.; Li, D.; Tanaka, K. Cloning of a Putative Monogalactosyldiacylglycerol Synthase gene from rice (Oryza Sativa L.) plants and its expression in response to submergence and other stresses. Planta 2004, 219, 450–458. [CrossRef]

- Lian, H.L.; Yu, X.; Ye, Q.; Ding, X.S.; Kitagawa, Y.; Kwak, S.S.; Su, W.A.; Tang, Z.C. The role of Aquaporin RWC3 in drought avoidance in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004, 45, 481–489. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Fukumoto, T.; Gena, P.; Feng, P.; Sun, Q.; Li, Q.; Matsumoto, T.; Kaneko, T.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Ectopic expression of a rice plasma membrane intrinsic protein (OsPIP1;3) promotes plant growth and water uptake. Plant J. 2020, 102, 779–796. [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.; Rao, Y.; Zeng, D.; Yang, Y.; Xu, R.; Zhang, B.; Dong, G.; Qian, Q.; Li, Y. SMALL GRAIN 1, which encodes a mitogen-activated protein kinase 4, influences grain size in rice. Plant J. 2014, 77, 547–557. [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Duan, P.; Yu, H.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, B.; Wang, R.; Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhuang, S.; Lyu, J.; et al. Control of grain size and weight by the OsMKKK10-OsMKK4-OsMAPK6 signaling pathway in rice. Mol. Plant 2018, 11, 860–873. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ren, Y.; Cai, Y.; Niu, M.; Feng, Z.; Jing, R.; Mou, C.; Liu, X.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, X.; et al. Overexpression of OsbHLH107, a member of the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor family, enhances grain size in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Rice 2018, 11. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jiang, L.; Zheng, J.; Chen, F.; Wang, T.; Wang, M.; Tao, Y.; Wang, H.; Hong, Z.; Huang, Y.; et al. A missense mutation in Large Grain Size 1 increases grain size and enhances cold tolerance in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 3851–3866. [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.; Rao, Y.; Wu, L.; Xu, Q.; Li, Z.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Leng, Y.; Hu, J.; Zhu, L.; et al. The pleiotropic ABNORMAL FLOWER AND DWARF 1 affects plant height, floral development and grain yield in rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2016, 58, 529–539. [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Liu, L.; Fang, J.; Zhao, J.; Yuan, S.; Li, X. The rice TRIANGULAR HULL1 protein acts as a transcriptional repressor in regulating lateral development of spikelet. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Cho, J. Il; Han, M.; Ahn, C.H.; Jeon, J.S.; An, G.; Park, P.B. The ABRE-binding BZIP transcription factor OsABF2 is a positive regulator of abiotic stress and ABA signaling in rice. J. Plant Physiol. 2010, 167, 1512–1520. [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Xiao, J.; Xiong, L. Constitutive activation of transcription factor OsbZIP46 improves drought tolerance in rice. Plant Physiol. 2012, 158, 1755–1768. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zhu, L.; Shou, H.; Wu, P. A PIN1 Family Gene, OsPIN1, involved in auxin-dependent adventitious root emergence and tillering in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005, 46, 1674–1681. [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Tao, J.; Bi, Y.; Hou, M.; Lou, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Luo, L.; Xie, X.; Yoneyama, K.; et al. OsPIN1b is involved in rice seminal root elongation by regulating root apical meristem activity in response to low nitrogen and phosphate. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Barrôco, R.M.; Peres, A.; Droual, A.M.; De Veylder, L.; Nguyen, L.S.L.; De Wolf, J.; Mironov, V.; Peerbolte, R.; Beemster, G.T.S.; Inzé, D.; et al. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor Orysa;KRP1 plays an important role in seed development of rice. Plant Physiol. 2006, 142, 1053–1064. [CrossRef]

- Kasai, K.; Kanno, T.; Akita, M.; Ikejiri-Kanno, Y.; Wakasa, K.; Tozawa, Y. Identification of three shikimate kinase genes in rice: Characterization of their differential expression during panicle development and of the enzymatic activities of the encoded proteins. Planta 2005, 222, 438–447. [CrossRef]

- Nojiri, H.; Sugimori, M.; Yamane, H.; Nishimura, Y.; Yamada, A.; Shibuya, N.; Kodama, O.; Murofushi, N.; Omori, T. Involvement of jasmonic acid in elicitor-induced phytoalexin production in suspension-cultured rice cells. Plant Physiol. 1996, 110, 387–392. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Choi, S.C.; An, G. Rice SVP-group MADS-box proteins, OsMADS22 and OsMADS55, are negative regulators of brassinosteroid responses. Plant J. 2008, 54, 93–105. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A.; Nakagawa, H.; Tomita, C.; Shimatani, Z.; Ohtake, M.; Nomura, T.; Jiang, C.J.; Dubouzet, J.G.; Kikuchi, S.; Sekimoto, H.; et al. Brassinosteroid Upregulated 1, encoding a helix-loop-helix protein, is a novel gene involved in brassinosteroid signaling and controls bending of the lamina joint in rice. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151, 669–680. [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zhao, H.; Li, S.; Han, Z.; Hu, G.; Liu, C.; Yang, G.; Wang, G.; Xie, W.; Xing, Y. Genome-wide association studies reveal that members of BHLH subfamily 16 share a conserved function in regulating flag leaf angle in rice (Oryza Sativa). PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Pantuwan, G.; Fukai, S.; Cooper, M.; Rajatasereekul, S.; O’Toole, J.C. Yield Response of Rice (Oryza Sativa L.) Genotypes to different types of drought under rainfed lowlands part 1. Grain yield and yield components. Field Crops Res. 2002, 73, 153–168. [CrossRef]

- Pantuwan, G.; Fukai, S.; Cooper, M.; Rajatasereekul, S.; O’Toole, J.C. Yield Response of Rice (Oryza Sativa L.) Genotypes to drought under rainfed lowlands 2. Selection of drought resistant genotypes. Field Crops Res. 2002, 73, 169–180. [CrossRef]

- Pantuwan, G.; Fukai, S.; Cooper, M.; Rajatasereekul, S.; O’Toole, J.C.; Basnayake, J. Yield response of rice (Oryza Sativa L.) genotypes to drought under rainfed lowlands: 3. Plant factors contributing to drought resistance. Field Crops Res. 2004, 89, 281–297. [CrossRef]

- Henry, A.; Gowda, V.R.P.; Torres, R.O.; McNally, K.L.; Serraj, R. Variation in root system architecture and drought response in rice (Oryza sativa): Phenotyping of the OryzaSNP panel in rainfed lowland fields. Field Crops Res. 2011, 120, 205–214. [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Swamy, B.P.M.; Vikram, P.; Ahmed, H.U.; Sta Cruz, M.T.; Amante, M.; Atri, D.; Leung, H.; Kumar, A. Fine mapping of QTLs for rice grain yield under drought reveals sub-QTLs conferring a response to variable drought severities. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012, 125, 155–169. [CrossRef]

- Palanog, A.D.; Swamy, B.P.M.; Shamsudin, N.A.A.; Dixit, S.; Hernandez, J.E.; Boromeo, T.H.; Cruz, P.C.S.; Kumar, A. Grain yield QTLs with consistent-effect under reproductive-stage drought stress in rice. Field Crops Res. 2014, 161, 46–54. [CrossRef]

- Venuprasad, R.; Dalid, C.O.; Del Valle, M.; Zhao, D.; Espiritu, M.; Sta Cruz, M.T.; Amante, M.; Kumar, A.; Atlin, G.N. Identification and characterization of large-effect quantitative trait loci for grain yield under lowland drought stress in rice using bulk-segregant analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009, 120, 177–190. [CrossRef]

- Swamy B. P., M.; Ahmed, H.U.; Henry, A.; Mauleon, R.; Dixit, S.; Vikram, P.; Tilatto, R.; Verulkar, S.B.; Perraju, P.; Mandal, N.P.; et al. Genetic, physiological, and gene expression analyses reveal that multiple QTL enhance yield of rice mega-variety IR64 under drought. PLoS One 2013, 8, 719–729. [CrossRef]

- Y, P.; Kamoshita, A.; Norisada, M.; Deshmukh, V. Eco-physiological evaluation of stele transversal area 1 for rice root anatomy and shoot growth. Plant Prod. Sci. 2020, 23, 202–210. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Xiong, H.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Ma, S.; Duan, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Natural Variation of DROT1 confers drought adaptation in upland rice. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Panda, D.; Mishra, S.S.; Behera, P.K. Drought tolerance in rice: Focus on recent mechanisms and approaches. Rice Sci. 2021, 28, 119–132. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Mu, P.; Li, C.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X. QTL Mapping of root traits in a doubled haploid population from a cross between upland and lowland japonica rice in three environments. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005, 110, 1244–1252. [CrossRef]

- Yi, K.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Du, L.; Guo, L.; Wu, Y.; Wu, P. OsPTF1, a novel transcription factor involved in tolerance to phosphate starvation in rice. Plant Physiol. 2005, 138, 2087–2096. [CrossRef]

- Monna, L.; Lin, H.X.; Kojima, S.; Sasaki, T.; Yano, M. Genetic dissection of a genomic region for a quantitative trait locus, Hd3, into two loci, Hd3a and Hd3b, controlling heading date in rice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2002, 104, 772–778. [CrossRef]

- Begum, H.; Spindel, J.E.; Lalusin, A.; Borromeo, T.; Gregorio, G.; Hernandez, J.; Virk, P.; Collard, B.; McCouch, S.R. Genome-wide association mapping for yield and other agronomic traits in an elite breeding population of tropical rice (Oryza sativa). PLoS One 2015, 10, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Courtois, B.; Ahmadi, N.; Khowaja, F.; Price, A.H.; Rami, J.F.; Frouin, J.; Hamelin, C.; Ruiz, M. Rice root genetic architecture: Meta-analysis from a drought QTL database. Rice 2009, 2, 115–128. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kumar, A.; Panda, D.; Modi, M.K.; Sen, P. Identification and characterization of drought responsive miRNAs from a drought tolerant rice genotype of Assam. Plant Gene 2020, 21, 100213. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, S.; Zhu, P.; Pan, T.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Hao, D.; Fang, H.; Xu, C.; et al. QTL-by-environment interaction in the response of maize root and shoot traits to different water regimes. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 229. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).