1. Introduction

Costa Rica is globally recognized for its exemplary environmental stewardship, particularly in biodiversity conservation and renewable energy. The country generates over 98% of its electricity from renewable sources and has designated more than a quarter of its land as protected, underscoring its commitment to sustainability [

1,

2]. However, beneath this success lies a significant and escalating challenge: waste management. Severe landfill management problems and low public participation in recycling not only threaten to undermine the country’s environmental achievements but also pose serious risks to public health and ecosystems [

3,

4].

This study addresses a critical gap in the literature by focusing on Costa Rica’s waste management challenges, an area that has received comparatively less attention in both academic and policy discussions. While extensive research exists on Costa Rica’s achievements in renewable energy and conservation, the waste management sector, particularly in urban areas like San José—which generates nearly 47% of the nation’s waste—has been plagued by inefficiencies and inadequate infrastructure [

5,

6]. The closure of major landfills, such as Los Pinos in Cartago, alongside the limited success of government initiatives like the Environmental Health Route policy, further underscores the severity of the situation [

7].

In response to these challenges, Costa Rica has enacted several legislative measures aimed at reducing waste and promoting sustainable practices. Notably, the “Ley para Combatir la Contaminación por Plástico y Proteger el Ambiente” (Law No. 9786), enacted in 2019, targets the reduction of single-use plastics and the promotion of circular economy practices. This law prohibits the distribution of plastic straws and non-reusable plastic bags, mandates the inclusion of recycled materials in plastic products, and emphasizes public education on plastic waste reduction [

8]. These efforts underscore the government’s commitment to tackling plastic pollution, a critical component of the broader waste management strategy.

In addition to infrastructural and logistical challenges, cultural and social factors contribute to the low levels of public participation in recycling programs, with less than 10% of the population actively engaged [

9,

10]. This study critiques the effectiveness of current government policies and compares Costa Rica’s situation with global waste management practices, particularly those of Germany and Japan, to identify strategies that could be adapted locally. The findings have broader implications for other developing nations facing similar challenges, offering insights into the effective implementation of sustainable waste management practices.

The objectives of this paper are to analyze the current state of waste management in Costa Rica, identify the primary challenges, evaluate the effectiveness of government initiatives, and propose innovative solutions based on successful practices from both local and international contexts. The paper is structured into three core sections: an overview of waste management in Costa Rica, an analysis of the challenges leading to the crisis, and an evaluation of government responses and policies. Through this structured approach, the study aims to contribute valuable insights into the intersection of waste management and environmental sustainability in developing countries.

2. Methodology

This study analyzed waste minimization practices in Costa Rican laboratories from 2015 to 2023, focusing on practices such as substituting nonhazardous materials (SNM), chemical treatment (CT), distillation (D), redistributing surplus chemicals (RSC), reducing the scale of experiments (RS), and purchasing less (PL). The dataset, sourced from relevant environmental and governmental organizations, was organized into pandas DataFrames, and missing data points were addressed through multiple imputation methods to ensure the dataset’s integrity. To predict future trends, a **hybrid modeling approach** combining **Linear Regression** with **AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA)** models was employed. Linear Regression was first used to establish a baseline trend, capturing the linear relationship between time and the adoption of waste minimization practices. ARIMA was then applied to model the residuals, incorporating autoregressive and moving average components to account for non-linear patterns, seasonal effects, and temporal dependencies in the data, resulting in more robust predictions for 2024 to 2050.

The reliability of these predictions was ensured through cross-validation, dividing the dataset into training and testing sets, which demonstrated a good fit for the hybrid model. A sensitivity analysis revealed that forecasts are particularly sensitive to changes in public engagement with recycling programs, highlighting the importance of this variable in predicting future trends. While this approach provides valuable insights, it acknowledges the limitations of assuming linearity in the initial regression step and the ARIMA model’s reliance on historical patterns, which may not account for sudden external changes. Future research could explore alternative modeling techniques, such as machine learning, to provide more comprehensive predictions and a deeper understanding of the factors influencing waste management practices in Costa Rica.

3. Current State of Waste Management

3.1. Overview of Waste Production

Despite its global reputation for environmental sustainability, Costa Rica faces significant challenges in effectively managing its waste. Recent studies indicate varying waste generation rates across the country, reflecting diverse socioeconomic conditions and infrastructure capabilities. In the Metropolitan Area of Costa Rica, the average waste generation rate is approximately 0.59 kg per person per day, with organic waste comprising 55.9% of the total waste stream [

11]. Similarly, in the Guácimo municipality, the average generation rate is slightly lower at 0.55 kg per person per day, with waste composed of 35% recyclable materials, 45% biodegradable waste, and 20% destined for landfills [

12].

Landfill capacities are under increasing strain, necessitating improved management practices, particularly in estimating leachate movement to design more efficient systems under tropical conditions [

13]. The closure of the Los Pinos landfill, a significant disposal site in Cartago, has exacerbated the waste management crisis, forcing municipalities to seek alternative solutions [

2]. These issues are compounded by regional disparities in waste management practices; while urban areas like San José generate nearly 47% of the nation’s waste, placing a substantial burden on existing infrastructure, rural regions face challenges such as inadequate waste collection services and limited access to recycling facilities [

2].

Comparing Costa Rica’s waste management system with those of other countries in the region reveals shared challenges, such as inadequate recycling infrastructure and high rates of waste leakage into the environment [

14]. Adopting best practices from countries with more advanced systems could help Costa Rica improve its overall waste management efficiency [

15].

3.2. Landfill capacities and regional waste management practices

Effective waste management is essential for preserving environmental health and ensuring sustainability. As Costa Rica continues to experience rapid urban growth, it is increasingly important to comprehend the current conditions of waste generation and management to achieve a balance with environmental conservation. The waste production in Costa Rica is substantial and concentrated in urban areas. The Greater Metropolitan Area (GAM), which includes San José, is home to approximately 50% of the country’s population, totaling approximately 2.6 million people. San José alone generates 47% of the nation’s waste [

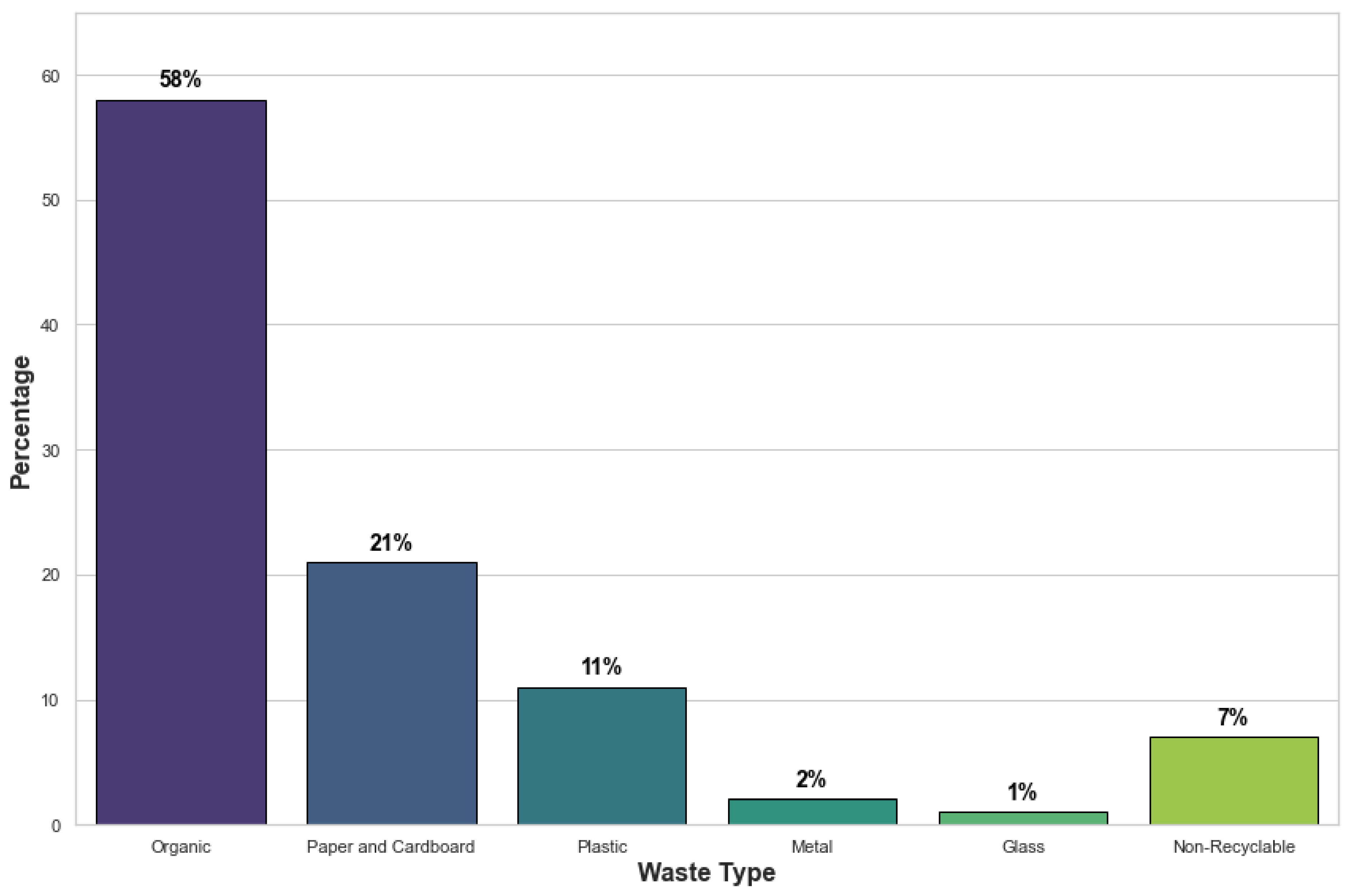

11]. The waste composition in San José is diverse, with organic waste comprising 58%, paper and cardboard 21%, plastic 11%, metal 2%, glass 1%, and non-recyclable waste 7% [

12].

In 2021, Costa Rica’s Ministry of Health reported that a total of 1,282,057 tonnes of waste were sent to landfills. However, only 9.6% of this waste was recoverable, indicating a low rate of recycling and waste recovery. This figure includes 3.9% for recycling, 2.7% for composting, and 2.4% for co-processing, reflecting the challenges in meeting the country’s waste recovery goals [

13]. The high concentration of waste production in urban areas, particularly San José, underscores the need for targeted waste management solutions. The diverse composition of waste, with a significant proportion of organic materials, suggests considerable potential for composting and organic waste treatment initiatives. Compared to global averages, Costa Rica’s recycling rate of 9.6% is significantly lower, highlighting the need for improved recycling infrastructure and increased public participation in recycling programs [

16].

The low recovery rate of 9.6% in 2021, combined with the high reliance on landfill disposal, indicates significant challenges in Costa Rica’s waste management system. This is further compounded by the rapid urbanization in regions like San José, where the waste production far outstrips the available infrastructure for recycling and recovery. The OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Costa Rica 2023 has underscored the urgency of addressing these issues, noting that without substantial improvements in waste management practices, the environmental and public health risks could escalate significantly. To address these challenges, Costa Rica must prioritize the expansion of recycling programs, invest in composting infrastructure for organic waste, and consider alternative waste treatment technologies such as waste-to-energy [

17].

The data underscore the urgent need for effective waste management policies, such as the Environmental Health Route policy, which aims to increase the recycling rate to 25% by 2033 and ensure regular garbage collection services for at least 34% of the country by 2023.

Table 1 details the waste production and recovery rates in Costa Rica, while

Figure 1 presents the waste composition in San José.

Caption: The waste in San José includes a significant proportion of organic materials (58%), followed by paper and cardboard (21%), plastic (11%), metal (2%), glass (1%), and non-recyclable waste (7%).

The waste production statistics reveal that a significant portion of Costa Rica’s waste is generated in urban areas, particularly San José, which accounts for nearly half of the nation’s total waste. The low recycling rate and high concentration of organic waste indicate areas where targeted policies and initiatives could make substantial improvements. Effective waste management strategies are crucial for mitigating environmental impacts and promoting sustainability in Costa Rica. Moving forward, it is essential to address the current challenges and implement innovative solutions to enhance waste recovery and recycling rates.

3.3. Landfill Capacities

The capacity of existing landfills in Costa Rica is a critical issue, with many sites nearing or exceeding their maximum capacity. Significant landfills such as those in La Carpio and Aserrí are on the verge of collapse, each receiving 600 tonnes of waste per day and having only a few years of useful life remaining [

11]. These sites have been in operation for several decades, and the volume of ordinary waste now surpasses their designed capacities. The Los Pinos landfill in Cartago was officially closed in January 2024 after reaching full capacity and failing to meet the necessary operational conditions due to geological risks and structural failures [

17].

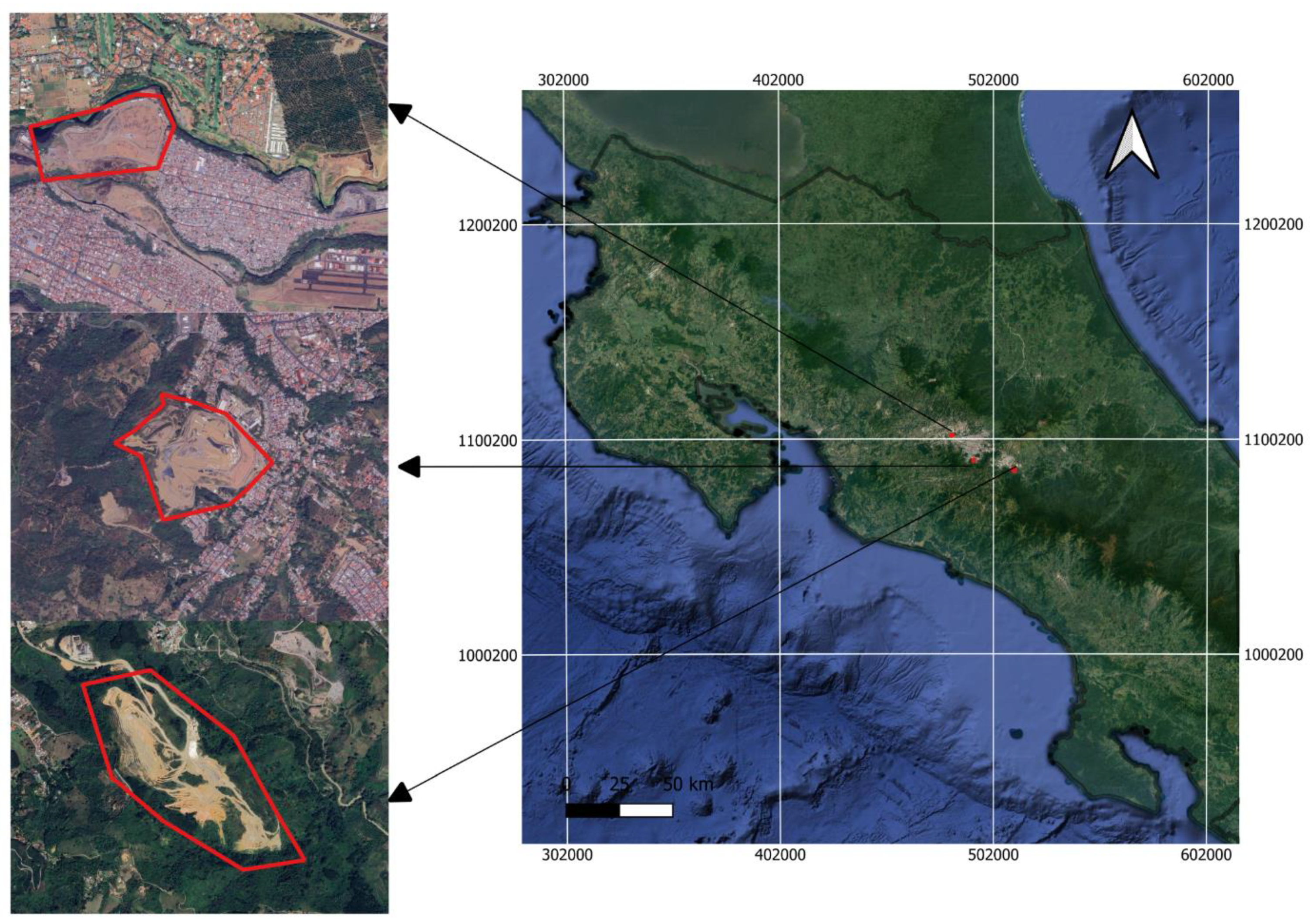

Figure 2 illustrates the geographic locations and extents of the La Carpio, Aserrí, and Los Pinos landfills, highlighting the proximity of these sites to urban areas and the environmental challenges associated with their operations.

Table 2 details the daily waste received and the estimated remaining life for the major landfill sites in Costa Rica.

Given this situation, Costa Rica must develop new waste disposal methods to alleviate the pressure on landfills and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. Currently, 94% of solid waste in Costa Rica ends up in landfills, designated waste disposal sites, or open-air dumps, posing significant risks to surface and groundwater quality. In urban areas such as San José, waste collection services are more accessible; however, the efficiency and frequency of these services vary, leading to inconsistent waste management. Urban expansion has caused environmental deterioration, exposing groundwater to nitrate pollution and contributing to air pollution-related diseases [

18]. Rural regions face greater challenges due to logistical issues and a lack of infrastructure. Many communities lack access to regular waste collection services, resulting in improper disposal practices such as burning or burying waste. This improper disposal poses environmental hazards and impacts public health, as unregulated waste management can lead to soil and water contamination [

19].

To address these challenges, Costa Rica must improve its waste management infrastructure, especially in rural areas, and adopt innovative waste disposal methods. Additionally, enhancing public education on proper waste disposal practices and increasing government support for waste management initiatives are crucial. These steps can mitigate the adverse effects of inadequate landfill capacity and promote a more sustainable waste management system.

4. Government Initiatives and Policies

The Costa Rican government has launched several significant initiatives aimed at improving waste management and promoting sustainability. One of the key initiatives is the

Environmental Health Route policy, introduced in April 2023. This policy includes ambitious goals, such as increasing the national recycling rate to 25% by 2033 and ensuring regular garbage collection services for at least 34% of the national territory by the end of 2023.Additionally, this policy sets specific sub-goals, including reducing per capita waste generation by 10% by 2025, expanding public education campaigns on waste separation, and developing new infrastructure for waste sorting and processing in underserved areas [

20].Another notable initiative is the

National Circular Economy Strategy, introduced in 2023. This strategy aims to enhance waste management practices and reduce emissions by promoting a circular economy model, where materials are reused, recycled, and repurposed to minimize waste. It also encourages businesses and consumers to adopt more sustainable practices, reduce the use of single-use plastics, and improve infrastructure for recycling and waste management [

21]. Additionally, the strategy focuses on fostering sustainable production and consumption patterns and promoting the use of recycled materials in new products [

22].

In addition to these policies, Costa Rica has implemented the ‘Ley para Combatir la Contaminación por Plástico y Proteger el Ambiente’ (Law No. 9786), passed in 2019. This law aims to drastically reduce single-use plastic usage through various measures, including the prohibition of plastic straws and non-reusable plastic bags, the promotion of reusable materials, and the integration of plastic waste education into the national curriculum. The law also mandates the creation of special programs for research and innovation to support the transition away from plastics, aligning with the goals of circular economy practices [

8].

These efforts highlight Costa Rica’s dedication to overcoming waste management issues and progressing toward sustainability. By establishing clear objectives and enacting strategic policies, the government aims to lessen environmental impact, enhance public health, and drive economic growth through sustainable practices. The ambitious targets of the

Environmental Health Route policy and the

National Circular Economy Strategy underscore the government’s strong commitment to improving waste management across various sectors.

Table 3 summarizes these government initiatives and their goals:

These initiatives represent Costa Rica’s comprehensive approach to addressing the multifaceted challenges of waste management. The Environmental Health Route policy and the National Circular Economy Strategy are central to this effort, setting ambitious targets for recycling and waste reduction while also focusing on the expansion of infrastructure and public education. By integrating immediate and long-term goals, these policies aim to minimize environmental impact, promote public health, and drive sustainable economic growth. The government’s strong commitment to these initiatives reflects a recognition of the need for tailored solutions that address the distinct challenges faced by both urban and rural areas. The emphasis on circular economy practices further underscores the strategic importance of reducing waste generation through innovative approaches. The effectiveness of these programs will ultimately depend on their implementation, public participation, and continuous evaluation. As Costa Rica advances these efforts, it has the potential to strengthen its environmental stewardship and serve as a model for other nations confronting similar waste management challenges.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Public Participation in Recycling

Despite government efforts, fewer than 10% of the population actively participates in recycling programs [

23]. To address this issue, the ecoins program was launched in 2017, promoting recycling through a technological economic reward scheme that encourages citizen participation in solid waste management. The program has established 520 collection sites and awarded 179,101,620.8 ecoins to 46,162 registered users. As a result, the program collected 3,762 tonnes of recyclable ordinary waste and avoided 4,592 tonnes of CO2 emissions [

17].

Table 4 highlights the impact of the ecoins program.

The ecoins program represents a significant step toward increasing public participation in recycling by providing tangible incentives for citizens. However, the overall participation rate remains low, indicating that further efforts are needed to enhance engagement. Comparative analysis with similar programs from other countries, such as Brazil’s EcoPontos and South Korea’s Eco Mileage Program, could provide valuable insights into different incentive structures and the effectiveness of such initiatives. For example, Brazil’s EcoPontos offers discounts on goods and services, while South Korea’s program rewards households for reducing energy consumption, both of which have contributed to higher engagement rates [

24,

25,

26,

27].To further boost participation, innovative approaches like gamification and blockchain technology could be explored. Gamification, as seen in Estonia’s Trash and Seek app, can make recycling more engaging and educational by rewarding users for correct sorting and recycling [

28]. Additionally, integrating blockchain technology could enhance transparency and accountability within the ecoins program by providing immutable records of recycling activities and ensuring the fair distribution of rewards [

29].

Expanding the digital presence of the ecoins program through a dedicated mobile app could also be an effective strategy. An app similar to Japan’s Pirika, which tracks recycling habits, offers real-time feedback, and connects users with local recycling initiatives, could significantly improve participation rates [

30]. Combined with comprehensive educational campaigns and targeted outreach, particularly in rural areas, these strategies could foster a stronger and more inclusive recycling culture across Costa Rica.

5.2. Additional Findings

Recent advancements in waste management and recycling technologies offer promising avenues for improving Costa Rica’s waste management systems. Developments in hydrological modeling, such as HydroGeoSphere and MODFLOW, have enabled more precise simulations of groundwater flow and contaminant transport, which are critical for landfill management in tropical climates. In Costa Rica, where tropical rainfall and humidity significantly influence leachate production, adopting tools like HYDRUS-2D/3D could enhance leachate estimation accuracy by integrating specific climate data and soil characteristics, complementing the existing HELP model to improve the overall efficiency and reliability of landfill management practices [

31,

32].

Costa Rica’s efforts to reduce plastic waste through single-use plastics bans and recycling programs have begun to align more closely with global best practices. However, comparisons with countries like Japan and Germany reveal that, despite commendable progress, Costa Rica still has room for improvement, particularly in public engagement and enforcement of these initiatives. Japan’s stringent recycling laws and Germany’s Green Dot system have effectively increased recycling rates by incentivizing producers and engaging the public. Adopting similar strategies in Costa Rica could potentially increase its recycling rates and reduce plastic waste more effectively [

33,

34]. Moreover, the variability in waste management financing across Costa Rican municipalities presents an opportunity for innovation. Implementing Pay-as-You-Throw (PAYT) systems, as seen in South Korea and parts of the United States, could encourage waste reduction by charging residents based on the amount of waste they dispose of. Similarly, Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs), successfully employed in Singapore’s waste management infrastructure, could attract private investment to enhance financial efficiency and sustainability in Costa Rica’s municipal waste management [

35,

36].

Costa Rica’s ongoing collaboration with the Netherlands in promoting a circular economy has shown positive outcomes, particularly in developing sustainable business models and facilitating technology transfers. Expanding these collaborations to include countries like Denmark and Finland, which are leaders in circular economy practices, could further support Costa Rica’s efforts, especially in sectors such as construction and manufacturing. These partnerships could enable the adoption of circular practices, such as converting organic waste into compost and bioenergy, thereby reducing overall waste and enhancing sustainability [

37,

38]. Additionally, the integration of innovative technologies, such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) and blockchain, presents valuable opportunities for advancing Costa Rica’s waste management strategies. AI can optimize waste collection routes, improving efficiency and reducing operational costs, and it can also be used in recycling facilities to enhance the sorting process, thereby increasing overall recycling efficiency. Blockchain technology could enhance transparency and accountability within the waste management system by providing secure, immutable records of transactions and recycling credits. Combined with platforms that encourage public participation, these technologies could help Costa Rica build a more engaged, transparent, and accountable waste management system, driving progress toward its sustainability goals [

38,

40].

5.3. Waste Minimization Practices

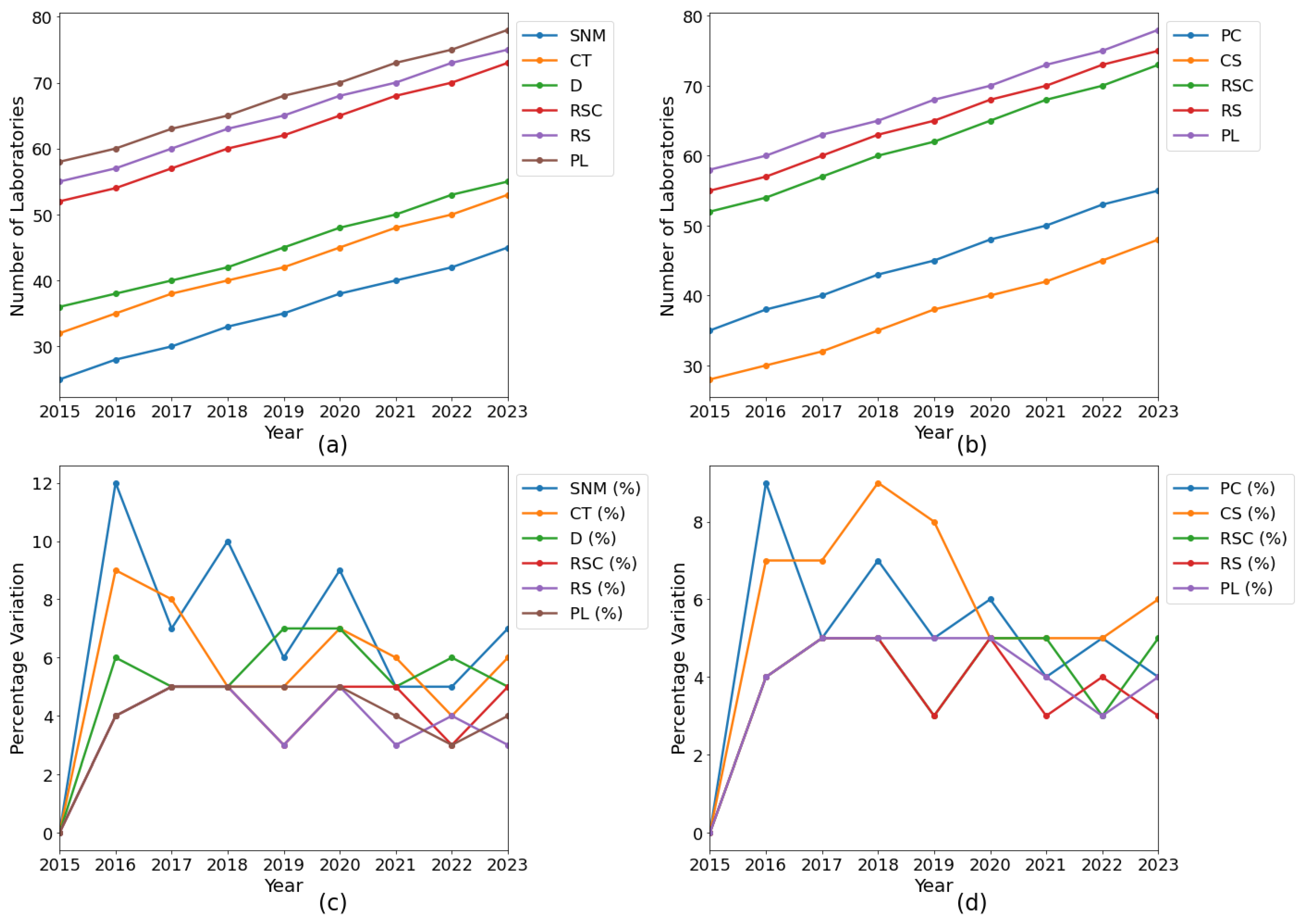

To better understand the effectiveness of waste minimization practices, it is imperative to examine the number of laboratories implementing various waste minimization strategies over time. The data indicate a significant increase in the adoption of six key waste minimization practices from 2015 to 2023: substituting nonhazardous materials (SNM), chemical treatment (CT, referring to the use of chemical processes to neutralize or convert hazardous substances), distillation (D), redistributing surplus chemicals (RSC), reducing the scale of experiments (RS), and purchasing less (PL)

(Figure 3a). Additionally, there has been an increase in laboratories performing five other practices, including purchase control (PC) and computer simulation (CS)

(Figure 3b).

The annual percentage variation for these waste minimization practices demonstrates the effectiveness of training and policy implementation over the years. This variation highlights the progress made in adopting these strategies and identifies areas needing further improvement (Figure 3c and 3d).

Caption: This comprehensive figure illustrates the trends in the number of laboratories performing six and five waste minimization practices from 2015 to 2023, as well as the annual percentage variation in these practices. The data, sourced from Supplementary Tables S1, S2, S3, and S4, highlight the progress made in adopting various waste minimization strategies, emphasizing the effectiveness of training and policy implementation over the years.

Costa Rica, recognized globally for its environmental sustainability efforts, still faces substantial challenges in effective waste management. The growing implementation of waste minimization strategies in laboratories throughout the country signals progress toward more sustainable practices. Notable increases in activities such as substituting nonhazardous materials and redistributing surplus chemicals highlight the success of current training programs and policy measures. Nonetheless, to further advance waste minimization efforts, it is crucial to continuously identify and address areas needing improvement.

By fostering a culture of sustainability within laboratories and other institutions, Costa Rica can continue to lead, for example, in environmental stewardship. Continued support for educational programs, investment in infrastructure, and the promotion of innovative waste management practices will be crucial in addressing the country’s waste management challenges and achieving long-term sustainability goals.

6. Comparative analysis: Costa Rica’s recycling rate vs. global averages

Assessing Costa Rica’s recycling rate relative to global standards is crucial for identifying areas requiring improvement and setting realistic goals for sustainable waste management. Currently, Costa Rica recycles only about 9.6% of its waste, reflecting significant challenges within its waste management system. The vast majority of waste is either sent to landfills (83.8%) or disposed of inappropriately, highlighting the urgent need for strategic interventions.

To contextualize Costa Rica’s position,

Table 5 presents recycling rates from various regions and countries, illustrating where Costa Rica stands in comparison to global standards. This comparison underscores the significant gaps in Costa Rica’s waste management practices and the necessity for robust reforms.

6.1. Key Factors Influencing Recycling Rates

Several factors contribute to these varying recycling rates across countries.

Table 6 provides a summary of these influencing factors, highlighting their impact on recycling rates and offering examples from different countries.

In comparison to these global practices, Costa Rica’s recycling efforts reveal substantial room for improvement. Strengthening and enforcing waste management policies could drive better recycling practices. Investment in recycling infrastructure and technology is crucial for effectively handling recyclable materials. Increasing public awareness and participation through comprehensive education campaigns could significantly enhance recycling rates. Additionally, implementing economic incentives, such as tax breaks for companies engaged in recycling or deposit return schemes, could encourage more robust recycling activities.

By focusing on these areas, Costa Rica can better align with global standards and support broader sustainability goals. This analysis underscores the need for a comprehensive waste management strategy, encompassing policy development, infrastructure enhancement, public involvement, and economic incentives to achieve significant progress in recycling and environmental sustainability.

7. Predictive Modeling and Policy Impact

The Environmental Health Route policy, launched in April 2023, serves as a cornerstone of Costa Rica’s strategy to address its waste management challenges. This policy aims to increase the national recycling rate to 25% by 2033 and ensure regular garbage collection across 34% of the national territory by 2023. Since its inception, the policy has achieved notable successes, particularly in urban areas where increased awareness and participation have led to recycling rates rising by as much as 15% in some neighborhoods [

20,

37]. The establishment of new recycling facilities in key urban centers has also enhanced the logistics of waste collection and processing, further supporting these gains [

38]. However, significant challenges persist, especially in rural areas where logistical issues and a lack of infrastructure have resulted in recycling participation rates of less than 10% [

39]. Even in urban areas, where some progress has been observed, the overall national recycling rate remains relatively low, suggesting that the policy has not yet achieved the widespread behavioral changes necessary for long-term impact [

40].

Projections based on predictive models indicate that if key improvements—such as increased funding for rural infrastructure, enhanced public education campaigns, and incentives for recycling participation—are implemented, the national recycling rate could reach 20% by 2028 and 25% by 2033 [

41]. Additionally, these models predict a 30% reduction in landfill use, significantly mitigating environmental degradation.

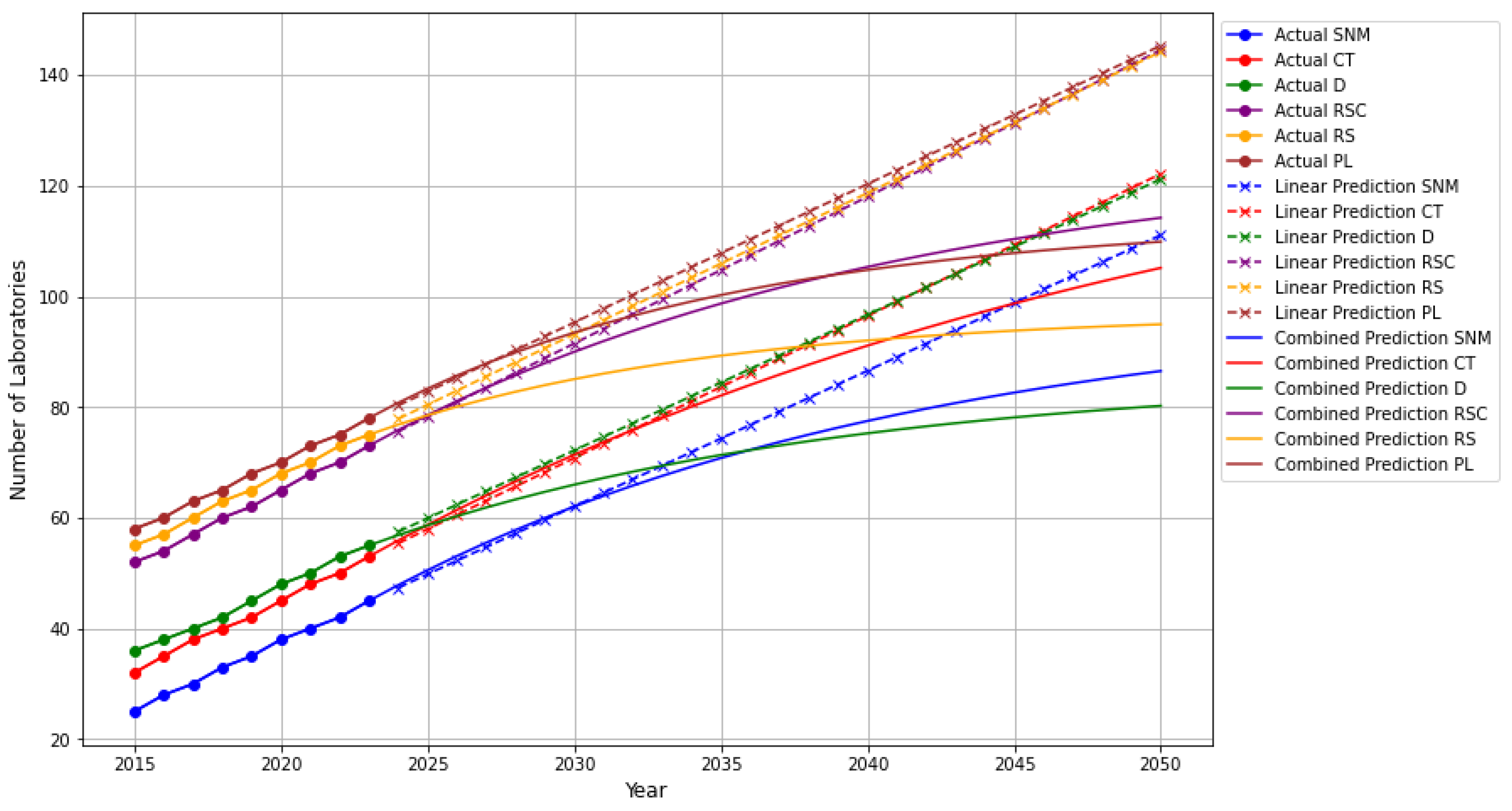

Figure 4 illustrates these projections, as well as the trends in the adoption of six key waste minimization practices—Source-Segregated Non-Metallics (SNM), Chemical Treatment (CT), Disposal (D), Recycling Systems (RSC), Reuse Systems (RS), and Process-Level Minimization (PL)—from 2015 to 2050.

Caption:This figure illustrates the actual and predicted number of laboratories performing six waste minimization practices from 2015 to 2050, based on data from Supplementary Tables S1 and S3. The solid lines represent actual data collected from 2015 to 2023, while the dashed lines indicate predictions for the years 2024 to 2050. The practices include Source-Segregated Non-Metallics (SNM), Chemical Treatment (CT), Disposal (D), Recycling Systems (RSC), Reuse Systems (RS), and Process-Level Minimization (PL). The projections suggest a continued increase in the number of laboratories adopting these practices, reflecting the long-term impact of ongoing government initiatives and policy improvements on national waste management and recycling efforts.

Costa Rica’s regulatory framework for waste management also includes comprehensive laws, such as the “Law for Comprehensive Waste Management” (2010), the “National Strategy to Phase Out Single-Use Plastic” (2017), and the more recent “Ley para Combatir la Contaminación por Plástico y Proteger el Ambiente” (Law No. 9786) enacted in 2019 [

8,

42]. These laws provide a robust legal structure addressing various aspects of waste management, including specific bans on single-use plastics and promoting circular economy practices. However, despite these strengths, enforcement challenges persist, particularly in rural areas where logistical barriers continue to hinder effective policy implementation [

39]. Furthermore, public participation in recycling programs remains lower than in countries like Germany and Japan [

43]. To address these weaknesses, it is recommended to strengthen enforcement by increasing resources for monitoring and implementing waste management regulations, particularly in rural regions. Encouraging public-private partnerships could also help attract investment in recycling infrastructure and technology [

44]. Economic incentives, such as tax breaks or subsidies for businesses and individuals actively participating in recycling efforts, could further enhance recycling rates [

45].

Predictive models suggest that with these targeted improvements—such as increased funding for rural infrastructure, enhanced public education campaigns, and incentives for recycling participation—the national recycling rate could reach 20% by 2028 and 25% by 2033 [

41]. Additionally, these models predict a 30% reduction in landfill use, significantly mitigating environmental degradation. Furthermore, enhanced infrastructure and public-private partnerships could improve waste collection efficiency by 40%, reducing overall waste management costs by 25% [

44]. By integrating successful frameworks from countries such as Germany, Costa Rica could see its recycling rate approach the EU average of 47% by 2040 [

43]. The projected increase in the adoption of waste minimization practices underscores the importance of maintaining and strengthening current initiatives to achieve the ambitious targets set by Costa Rica’s environmental policies.

7.1. Stakeholder Perspectives

Stakeholder perspectives on waste management in Costa Rica highlight a complex interplay of regulatory, cultural, and economic factors that significantly impact the effectiveness of recycling initiatives. Government officials stress the need for comprehensive policies and stricter enforcement, particularly in rural areas where infrastructure deficiencies and traditional waste disposal practices, such as burning or burying waste, persist. This emphasis suggests that future legislative actions may include developing more robust rural waste management infrastructure and implementing stricter penalties for non-compliance with recycling regulations. Additionally, these officials may advocate for legislation that mandates educational programs tailored to address cultural barriers in rural communities, ensuring that waste management practices are adapted to local contexts, as seen in the study by Wang et al. (2021) on rural China [

49].

Environmental groups argue for stronger government action and deeper community engagement, asserting that current enforcement mechanisms are insufficient. Without comprehensive public education campaigns that are sensitive to local cultural contexts, they believe recycling initiatives will continue to fall short. These groups may influence the development of policies that integrate Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) frameworks, which balance environmental, economic, and social criteria to create more effective and inclusive waste management strategies, as proposed by Knickmeyer (2020) [

50]. Businesses, on the other hand, support economic incentives, such as tax breaks and subsidies, to encourage corporate investment in recycling infrastructure. Their willingness to invest, provided there is adequate regulatory support, highlights the potential for public-private partnerships (PPPs) to drive innovation in waste management. Costa Rica could implement similar economic strategies to those in Chile, fostering greater corporate participation in sustainable waste management through targeted tax incentives and subsidies, as noted by Araya-Córdova et al. (2021) [

51].

Advanced methodologies, such as Social Network Analysis (SNA) and Geographic Information Systems (GIS), could further enhance the understanding of stakeholder dynamics and regional influences on waste management. SNA could map relationships and uncover power dynamics among stakeholder groups, providing insights into communication pathways that influence policy implementation and engagement. This could lead to policies that specifically target key influencers in the waste management system, thereby improving policy rollouts. Similarly, GIS tools could inform the spatial planning of waste management infrastructure by identifying regions with the most urgent needs, ensuring that investments in waste management infrastructure are strategically allocated [

48]. Predictive modeling techniques, such as System Dynamics Modeling, could play a crucial role in shaping future waste management strategies by offering a forward-looking assessment of the long-term impact of current policies on stakeholder engagement. For example, machine learning models could analyze historical data to forecast the success of educational programs aimed at changing cultural norms around waste management, enabling policymakers to refine strategies and ensure more effective promotion of sustainable waste management practices across Costa Rica [

51].

7.2. Global Case Studies

Costa Rica’s waste management practices can be compared with successful models from other countries to identify valuable insights and practical solutions. Germany is renowned for its high recycling rates and efficient waste management system, with household waste recycling rates ranging from 65% to 70%. This success is attributed to stringent regulations, extensive public awareness campaigns, and advanced recycling infrastructure. Key initiatives, such as the deposit return scheme for beverage containers and the Green Dot program, which requires manufacturers to consider the end-of-life disposal of their products, contribute significantly to Germany’s impressive recycling performance [

42]. These initiatives highlight the importance of a robust legislative framework and the integration of economic incentives, both of which could be adapted to Costa Rica’s context to enhance its recycling rates and overall waste management efficiency.

Japan’s waste management strategy is characterized by a comprehensive approach that emphasizes waste reduction, recycling, and environmentally sound disposal methods. The recycling rate in Japan varies depending on the type of waste, with the material recycling rate for plastics at approximately 23.8% to 24.4%. When including thermal recycling (incineration with energy recovery), the rate for plastics can reach as high as 84% [

52]. Japan’s approach, which includes strong legislative frameworks, public participation through mandatory recycling practices, and the use of advanced technologies for waste treatment, has led to significant increases in recycling rates over the past decades [

44]. For Costa Rica, adopting Japan’s focus on public participation and the integration of advanced waste treatment technologies could be instrumental in overcoming its current waste management challenges.Brazil, on the other hand, exhibits a recycling rate for municipal waste of approximately 1% to 3%, although this rate can be higher in urban areas where informal waste pickers and cooperatives are active. Brazil’s waste management system is significantly driven by these informal workers, who play a crucial role in the recycling process. Despite these challenges, Brazil has achieved notable successes in integrating informal workers into formal waste management systems, thereby improving recycling rates in certain regions [

45]. Costa Rica, facing similar challenges with informal waste sectors, could benefit from examining Brazil’s strategies for integrating informal workers into a more structured system, thereby enhancing the efficiency and reach of its waste management efforts.

By examining these case studies, Costa Rica can identify specific strategies to enhance its waste management practices. Strengthening regulations and ensuring strict enforcement can significantly boost recycling rates, while continuous education campaigns and public participation are crucial for effective waste management. Additionally, investing in advanced recycling infrastructure and technology is essential for efficient waste management. Implementing economic incentives such as deposit return schemes and producer responsibility programs, similar to those in Germany, can encourage recycling and reduce waste. Incorporating these global best practices, alongside the continued efforts of Costa Rican policies and initiatives, can lead to significant improvements in the country’s waste management system. By learning from successful models worldwide, Costa Rica can serve as a strong example for other nations facing similar challenges, reinforcing its reputation as a leader in environmental stewardship.

7.3. Technological Innovations

Implementing advanced technologies in Costa Rica’s waste management practices can significantly enhance their efficiency and effectiveness. Waste-to-energy (WtE) technologies, which convert non-recyclable waste into usable heat, electricity, or fuel, have proven successful in countries such as Sweden and Germany. These technologies not only reduce landfill waste but also provide a renewable energy source, potentially alleviating landfill pressure in Costa Rica while contributing to the country’s renewable energy goals [

53]. In Costa Rica, companies like Holcim and Cementos Progreso are utilizing waste as fuel in their cement kilns as part of broader strategies to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and minimize environmental impact. For instance, Holcim has been steadily increasing the percentage of waste used as fuel, with recent upgrades targeting an increase from 30% to 60% [

54]. The waste used includes a mix of household and industrial sources, such as refuse-derived fuel (RDF), non-recyclable plastics, used motor oil, and tires [

55].The use of robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning in automated waste sorting systems can dramatically improve the accuracy and speed of sorting recyclable materials. Such technologies have enhanced the efficiency and purity of recovered materials in countries like Japan and South Korea, offering significant potential benefits for Costa Rica’s recycling infrastructure [

56]. Moreover, digital platforms integrated with IoT devices and sensors provide real-time data on waste generation, collection, and processing. These platforms facilitate better planning and decision-making by optimizing collection routes and reducing operational costs. Cities like Barcelona and Singapore have successfully implemented smart waste management solutions, resulting in more efficient waste collection and reduced environmental impact [

57].

The development and adoption of biodegradable and compostable materials offer environmentally friendly alternatives to traditional plastics. These materials naturally decompose, thereby reducing the environmental impact of plastic waste. Promoting the use of biodegradable packaging and products in Costa Rica, alongside developing the necessary composting infrastructure, could lead to significant environmental benefits. However, financing these initiatives remains a challenge. Various countries employ different financial mechanisms to support such efforts, including subsidies, taxes, and international support. In Europe, subsidies are commonly used to encourage biodegradable waste management, though the effectiveness of these subsidies varies. For example, Sweden imposes landfill taxes to discourage landfill use and promote recycling and composting. Two decades ago, Sweden’s landfill tax was approximately

$25 per ton, and this tax has likely increased to continue supporting waste management initiatives [

58]. However, such a tax may not be suitable for contexts like Costa Rica, where a significant portion of waste is not even collected.In contrast, countries like the Netherlands and the United States finance advanced recycling technologies through a mix of taxes, subsidies, and incentives, enabling the development of chemical recycling and pyrolysis technologies capable of handling mixed and contaminated plastics [

59]. Developing countries often rely on international financial mechanisms, such as Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) projects, which attract investments for waste management initiatives that reduce greenhouse gas emissions [

59]. Additionally, mechanisms like organic waste buyback programs and international support from organizations such as the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and the World Bank help finance composting infrastructure and advanced recycling technologies in resource-limited regions [

46,

57]. By investing in these advanced recycling technologies and exploring various financial mechanisms, Costa Rica could significantly enhance its recycling capabilities and develop sustainable waste management practices.

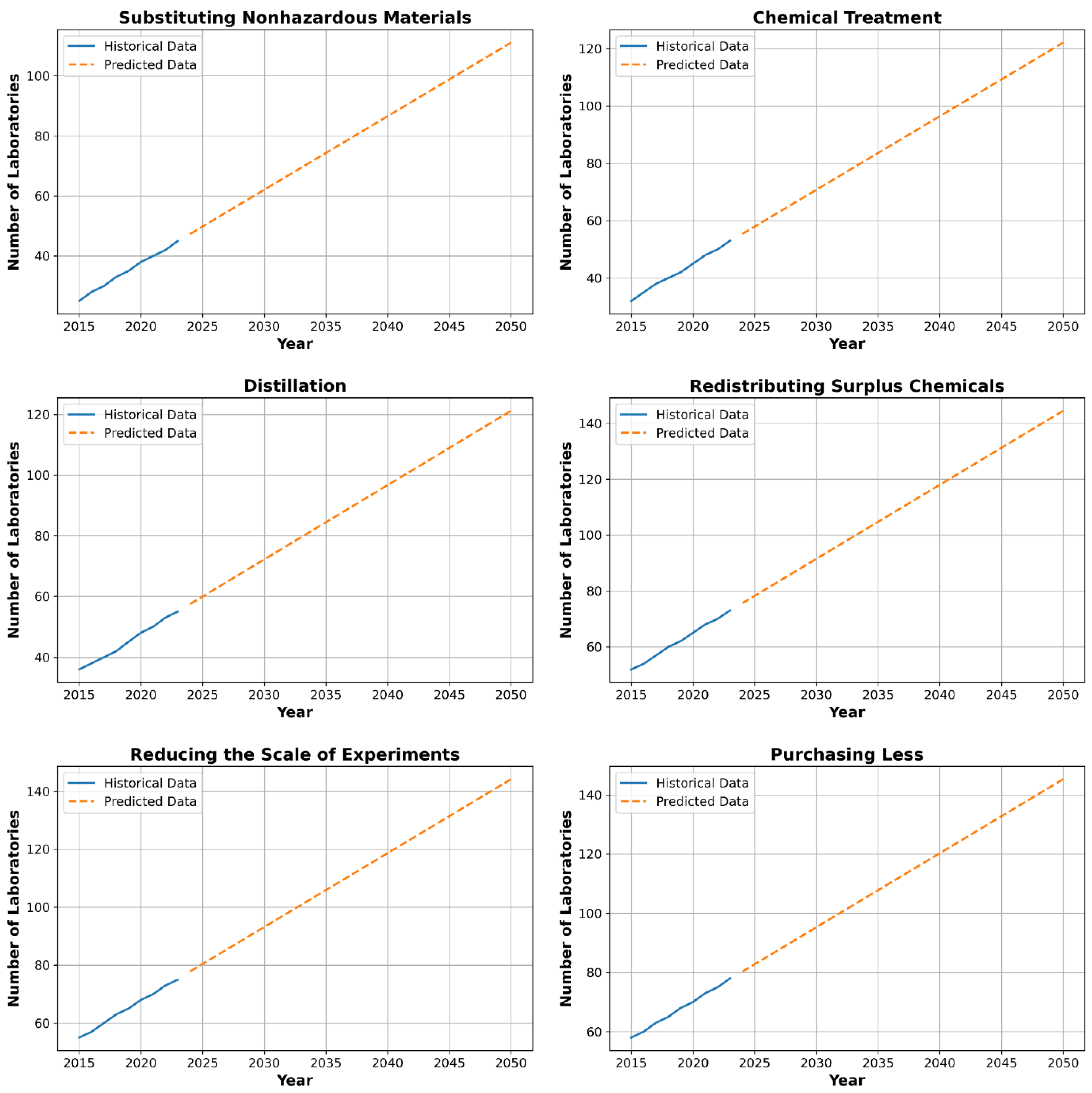

The analysis of the number of laboratories performing six waste minimization practices from 2015 to 2023, along with the predicted numbers for 2024 and 2050, is illustrated in

Figure 5. The detailed data supporting these trends are available in Supplementary Tables S1 and S3.

Caption: This figure illustrates the actual and predicted number of laboratories performing six waste minimization practices from 2015 to 2050. The solid lines represent actual data collected from 2015 to 2023, while the dashed lines indicate predictions for the years 2024 to 2050. The practices include substituting nonhazardous materials (SNM), chemical treatment (CT), distillation (D), redistributing surplus chemicals (RSC), reducing the scale of experiments (RS), and purchasing less (PL). The projections suggest a steady increase in the number of laboratories adopting these practices, reflecting the potential impact of ongoing government initiatives and policy improvements on national waste management and recycling efforts.

The trends depicted highlight significant progress in waste minimization practices across Costa Rican laboratories, demonstrating the effectiveness of recent technological innovations and policy initiatives. The steady rise in practices such as substituting nonhazardous materials and advanced recycling techniques indicates a growing integration of sustainability into laboratory operations, likely driven by regulatory pressures and increased awareness of the benefits of these practices, including cost efficiency and reduced environmental impact. The data suggests not only a wider adoption of these strategies but also improvements in their implementation, positioning Costa Rican laboratories as potential leaders in sustainable research practices within the region. However, the trends also reveal opportunities for further enhancement, particularly in broadening the reach of these practices beyond early adopters and increasing public engagement. Overall, the visualized trends underscore the pivotal role of innovation and regulation in advancing environmental sustainability within the research sector, offering valuable insights into the ongoing and future potential of waste minimization efforts in Costa Rica.

8. Discussion

The findings of this study highlight significant challenges in Costa Rica’s waste management system, exposing gaps between policy intentions and on-the-ground realities. Despite the strong commitment demonstrated by initiatives like the Environmental Health Route policy and the National Circular Economy Strategy, their limited success, particularly in rural areas, underscores the need for more targeted interventions. Low participation rates in recycling, despite ambitious goals, suggest that without addressing fundamental barriers such as inadequate infrastructure, socio-economic disparities, and limited public engagement, these policies may fall short.

The introduction of the ‘Ley para Combatir la Contaminación por Plástico y Proteger el Ambiente’ represents a significant legislative effort to combat environmental degradation by targeting single-use plastics. This law aims to alleviate pressure on the waste management system by promoting sustainable alternatives and integrating plastic waste education. However, the success of this law will depend on effective enforcement, public compliance, and industrial adaptation. Without robust implementation, even the most well-intentioned legislation risks falling short of its potential.

While technological innovations such as waste-to-energy systems and AI-driven sorting technologies offer promising solutions, their widespread adoption is constrained by the current state of Costa Rica’s infrastructure. Significant investment in upgrading facilities and training personnel is essential to align these technologies with the country’s sustainability goals. Moreover, public participation remains crucial; addressing cultural and educational barriers is key to increasing engagement in recycling programs.

Ultimately, the sustainability of Costa Rica’s waste management strategies hinges on effective stakeholder collaboration, involving government agencies, businesses, environmental groups, and the public. Public-private partnerships (PPPs) could play a crucial role in advancing waste management infrastructure. However, for these partnerships to succeed, clear regulatory frameworks, financial incentives, and a shared commitment to environmental sustainability are essential. Continuous monitoring, evaluation, and adaptation of policies, supported by legislation like the Ley para Combatir la Contaminación por Plástico y Proteger el Ambiente, are necessary to respond to emerging challenges and ensure the resilience and effectiveness of Costa Rica’s waste management system.

9. Conclusion

This study highlights the critical need for targeted reforms in Costa Rica’s waste management system, particularly in addressing the low recycling rates and the over-reliance on landfills. While the government has demonstrated a strong commitment to environmental sustainability, significant challenges remain, especially in rural areas where infrastructure deficiencies and limited public participation are prevalent. Moving forward, the expansion of recycling infrastructure, coupled with enhanced public education efforts, will be essential. Additionally, fostering public-private partnerships and integrating advanced technologies like AI-driven sorting systems and biodegradable materials are vital steps toward modernizing waste management practices. To ensure lasting impact, these strategies must be adaptable to local contexts and supported by robust legislative frameworks. By focusing on these areas, Costa Rica can not only overcome its current waste management challenges but also position itself as a model for sustainable practices on a global scale.

Author Contributions

Andrea Navarro Jimenez conceived and designed the research, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- Montero, A. , Marull, J., Tello, E., Cattaneo, C., Coll, F., Pons, M., & Vargas, M. (2021). The impacts of agricultural and urban land-use changes on plant and bird biodiversity in Costa Rica (1986–2014). Regional Environmental Change, 21. [CrossRef]

- Groves, D. , Syme, J., Molina-Pérez, E., Hernandez, C., Victor-Gallardo, L., Godínez-Zamora, G., & Vogt-Schilb, A. (2020). The benefits and costs of decarbonizing Costa Rica’s economy: Informing the implementation of Costa Rica’s National Decarbonization Plan under uncertainty. Inter-American Development Bank. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, I. (2024, July 17). Costa Rica on the brink of a garbage crisis. The Tico Times, Retrieved from https://ticotimes.net/2024/07/17/costa-rica-on-the-brink-of-a-garbage-crisis.

- Campos-Rodríguez, R. , Quirós-Bustos, N., & Navarro-Garro, A. (2015). Alternatives and actions regarding solid residues, presented by Jimenez and Oreamuno municipalities and their relation to development and sustainability. Tecnología en Marcha, Retrieved from https://typeset.io/papers/alternatives-and-actions-regarding-solid-residues-presented-3uy0tpod8z.

- Jiménez-Antillón, J. , Rodríguez-Rodríguez, A., & Pino-Gómez, M. (2019). Recuperación de los residuos sólidos en el Tecnológico de Costa Rica a 15 años de la creación de la actividad permanente Manejo de Residuos Institucionales MADI. Tecnología en Marcha, Retrieved from https://typeset.io/papers/recuperacion-de-los-residuos-solidos-en-el-tecnologico-de-1vnzauhce9.

- Campos-Rodríguez, R. , & Soto-Córdoba, S. (2014). Análisis de la situación del estado de la Gestión Integral de Residuos (GIR) en el Cantón de Guácimo, Costa Rica. Tecnología en Marcha, Retrieved from https://typeset.io/papers/analisis-de-la-situacion-del-estado-de-la-gestion-integral-yhxgl9vzn5.

- Villalobos-Portilla, E. , Quesada-Román, A., & Campos-Durán, D. (2020). Hydrometeorological disasters in urban areas of Costa Rica, Central America. Environmental Hazards, 20(3), 264-278. [CrossRef]

- Procuradoria de la Republica de Costa Rica: “Ley para Combatir la Contaminación por Plástico y Proteger el Ambiente, N° 9786.” Sistema Costarricense de Información Jurídica. Available at: http://www.pgrweb.go.cr/scij/Busqueda/Normativa/Normas/nrm_texto_completo.aspx?nValor1=1&nValor2=90187. Accessed on August 13, 2024.

- Keramitsoglou, K. M. , & Tsagarakis, K. (2013). Public participation in designing a recycling scheme toward maximum public acceptance, Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 70, 55-67. [CrossRef]

- May, E. S. , & Goldstein, J. M. (2006). Improved waste management in Costa Rica’s Uruca River Basin. Tecnología en Marcha, Retrieved from https://typeset.io/papers/improved-waste-management-in-costa-rica-s-uruca-river-basin-56odu54kwy.

- Herrera-Murillo, J. , Rojas-Marín, J. F., & Anchía-Leitón, D. (2016). Tasas de generación y caracterización de residuos sólidos ordinarios en cuatro municipios del Área Metropolitana Costa Rica. Revista Geológica de América Central. [CrossRef]

- Campos Rodríguez, R. , & Soto Córdoba, S. M. (2014). Estudio de generación y composición de residuos sólidos en el cantón de Guácimo, Costa Rica. Tecnología en Marcha, 27, 122-135.

- Baltodano-Goulding, R. , & Poveda-Montoya, A. (2023). Unsaturated seepage analysis for an ordinary solid waste sanitary landfill in Costa Rica. E3S Web of Conferences. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, A. L. , Wang, S., & Jambeck, J. R. (2020). Plastic Waste Management and Leakage in Latin America and the Caribbean. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 160, 111713. [CrossRef]

- Graham, E. A. (2024). The Role of Geographic Information Systems in Mitigating Plastics Pollution in the Global South. Global Environmental Change, 74, 102432. [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2023). OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Costa Rica 2023. OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Chaves Brenes, K. (2024, February 14). San José: ecoins – promoting the circular economy and decarbonisation through public-private partnerships. International Institute for Environment and Development, Retrieved from https://www.iied.org/san-jose-ecoins-promoting-circular-economy-decarbonisation-through-public-private-partnerships.

- Brenes-Peralta, L. , Rojas-Vargas, J., Monge-Fernández, Y., Jiménez-Morales, M. F., Arguedas-Camacho, M., Hidalgo-Víquez, C., Peña-Vásquez, M., & Vásquez-Rodríguez, B. (2021). Food loss and waste in food services from educational institutions in Costa Rica. Technology and Management, 34(2). [CrossRef]

- González-Maya, J. F. , Víquez-R., L., Belant, J., & Ceballos, G. (2015). Effectiveness of protected areas for representing species and populations of terrestrial mammals in Costa Rica. PLoS ONE, 10(4), e0124480. [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Salud de Costa Rica. (2023). Informe Anual de Gestión Ambiental 2023, Retrieved from https://www.ministeriodesalud.go.cr/index.php/informes-de-gestion.

- Gómez, C. C. (2023). Circular economy plastic policies in Costa Rica: A critical policy analysis. Circular Innovation Lab. ISBN 978-87-94507-05-9.

- Holland Circular Hotspot. (2021). Waste Management Country Report: Costa Rica, Retrieved from https://hollandcircularhotspot.nl/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Report_Waste_Management_Costa_Rica_20210329.pdf.

- Hidalgo Arroyo, I. (2021, July 2). Ahora podrá adquirir ecoins cada vez que deposite residuos ordinarios de forma correcta. Delfino CR, Retrieved from https://delfino.cr/2021/07/ahora-podra-adquirir-ecoins-cada-vez-que-deposite-residuos-ordinarios-de-forma-correcta.

- Wilson, D. C. , Velis, C., & Cheeseman, C. (2012). Role of informal sector recycling in waste management in developing countries. Habitat International, 30(4), 797-808. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y. , & Kim, H. (2018). Public Participation in Environmental Management in South Korea: The Eco Mileage Program. Sustainability, 10(11), 4013. [CrossRef]

- Bilitewski, B. (2008). Waste Management in Germany. Waste Management World, 9(5), 43-51.

- Zhao, G. , Fan, X., & Yan, J. (2016). Overview of business innovations and research opportunities in blockchain and introduction to the special issue. Financial Innovation, 2(1), 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J. , Koivisto, J., & Sarsa, H. (2014). Does gamification work?--a literature review of empirical studies on gamification. In 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (pp. 3025-3034). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y. J. , & Woo, C. (2020). The effect of environmental education on environmental attitudes and behavior: A case study of the Pirika App in Japan. Journal of Environmental Management, 269, 110766. [CrossRef]

- McKenzie-Mohr, D. (2000). Promoting sustainable behavior: An introduction to community-based social marketing. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 543-554. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (2004). The Hydrologic Evaluation of Landfill Performance (HELP) model: Engineering documentation for Version 3. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov.

- Plastic Pollution Coalition. (2021). Costa Rica’s battle against plastic pollution, Retrieved from https://www.plasticpollutioncoalition.org.

- Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). (2020). Financing waste management: A comparison among Latin American countries, Retrieved from https://www.iadb.org.

- Netherlands Enterprise Agency. (2021). Circular economy collaboration between the Netherlands and Costa Rica, Retrieved from https://www.rvo.nl.

- Scheinberg, A. , Simpson, M. H., & Gupt, Y. (2010). Economic Aspects of the Informal Sector in Solid Waste Management. GIZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit), Retrieved from https://www.giz.de.

- Huber, J. , Horbach, J., & Schlör, H. (2020). Transition towards a Circular Economy: Municipal Waste Management Case Studies from Germany and Sweden. Sustainability, 12(1), 123. [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P. , Cialani, C., & Ulgiati, S. (2016). A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. Journal of Cleaner Production, 114, 11-32. [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J. , Reike, D., & Hekkert, M. (2018). Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions, Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 127, 221-232. [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilian, B. , Wang, B., Lewis, K., & Duarte, F. (2018). Blockchain for Waste Management in Smart Cities: A Survey on Applications and Future Trends. Journal of Environmental Management, 225, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Hammi, B. , Hammi, B., Bellot, P., & Serhrouchni, A. (2018). BCoT: A Blockchain-based IoT Framework for Secure Smart City. Internet of Things Journal, 5(2), 1038-1050. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2020). Waste statistics - recycling rates, Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Waste_statistics.

- Dornack, C. (2017). Waste policy for source separation in Germany. In Source Separation and Recycling (pp. 3-10). [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (2020). National Overview: Facts and Figures on Materials, Wastes and Recycling, Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/national-overview-facts-and-figures-materials.

- Tanaka, M. (1999). Recent trends in recycling activities and waste management in Japan. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management, 1(1), 10-16. [CrossRef]

- Troschinetz, A. M. , & Mihelcic, J. R. (2009). Sustainable recycling of municipal solid waste in developing countries. Waste Management, 29(2), 915-923. [CrossRef]

- Korea Environment Institute (KEI). (2020). Waste Management Policies and Practices in South Korea, Retrieved from https://www.kei.re.kr.

- Avfall Sverige. (2021). The Swedish Waste Management System: A Model for Sustainability, Retrieved from https://www.avfallsverige.se.

- Han, Z. , Liu, Y., Zhong, M., Shi, G., Li, Q., Zeng, D., Zhang, Y., Fei, Y., & Xie, Y. (2018). Influencing factors of domestic waste characteristics in rural areas of developing countries. Waste Management, 72, 45-54. [CrossRef]

- Wang, A. , Dang, S., Luo, W., & Ji, K. (2021). Cultural consumption and knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding waste separation management in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19. [CrossRef]

- Knickmeyer, D. (2020). Social factors influencing household waste separation: A literature review on good practices to improve the recycling performance of urban areas. Journal of Cleaner Production, 245, 118605. [CrossRef]

- Araya-Córdova, P. J. Dávila, S., Valenzuela-Levi, N., & Vásquez, Ó. C. (2021). Income inequality and efficient resources allocation policy for the adoption of a recycling program by municipalities in developing countries: The case of Chile. Journal of Cleaner Production, 309, 127305. [CrossRef]

- Amemiya, T. (2018). Current state and trend of waste and recycling in Japan. International Journal of Earth & Environmental Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, O. , & Finnveden, G. (2009). Waste management in Sweden and its environmental benefits. Waste Management, 29(3), 1063-1073. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Esquivel, L. G. , & Acuña-Piedra, A. (2020). Hazardous waste management in Costa Rica: An academic–small company collaboration. Waste Management and the Environment IX, 247, 161-170. [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, K. , & Kawamoto, S. (2021). Advances in AI and robotics in waste management: Japan’s automated sorting systems. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management, 23(2), 198-207. [CrossRef]

- Kaza, S. , Yao, L., Bhada-Tata, P., & Van Woerden, F. (2018). What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050. The World Bank. [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, H. Meegoda, J., & Ryu, S. (2018). Organic Waste Buyback as a Viable Method to Enhance Sustainable Municipal Solid Waste Management in Developing Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15. [CrossRef]

- Barton, J. , Issaias, I., & Stentiford, E. (2008). Carbon--making the right choice for waste management in developing countries. Waste Management, 28(4), 690-698. [CrossRef]

- Briguglio, M. (2021). Taxing household waste: Intended and unintended consequences. Journal of Cleaner Production. [CrossRef]

- Cimpan, C. , Rothmann, M., Hamelin, L., & Wenzel, H. (2015). Towards increased recycling of household waste: Documenting cascading effects and material efficiency of commingled recyclables and biowaste collection. Journal of Environmental Management, 157, 69-83. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).