Submitted:

02 March 2024

Posted:

05 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Public Policy around the World on Utilizing Landfills

1.2. Israel’s Landfilling Policy

2. Methodology

3. Findings

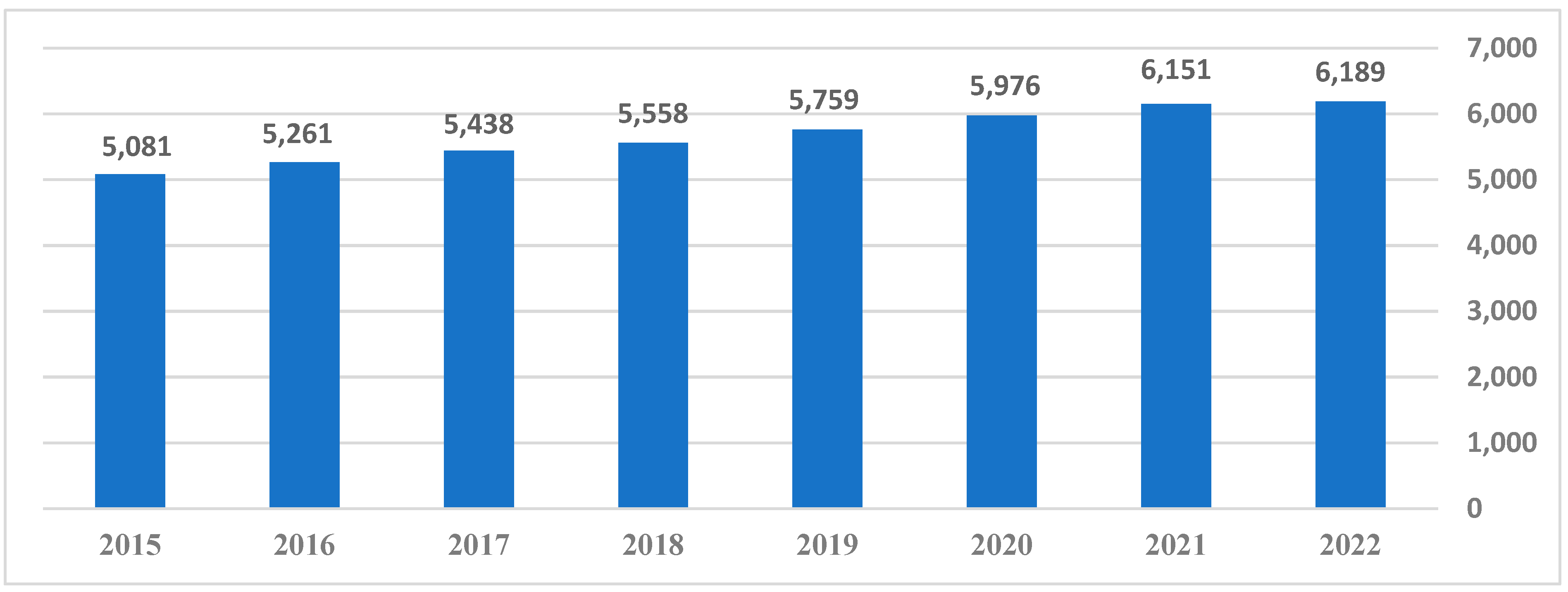

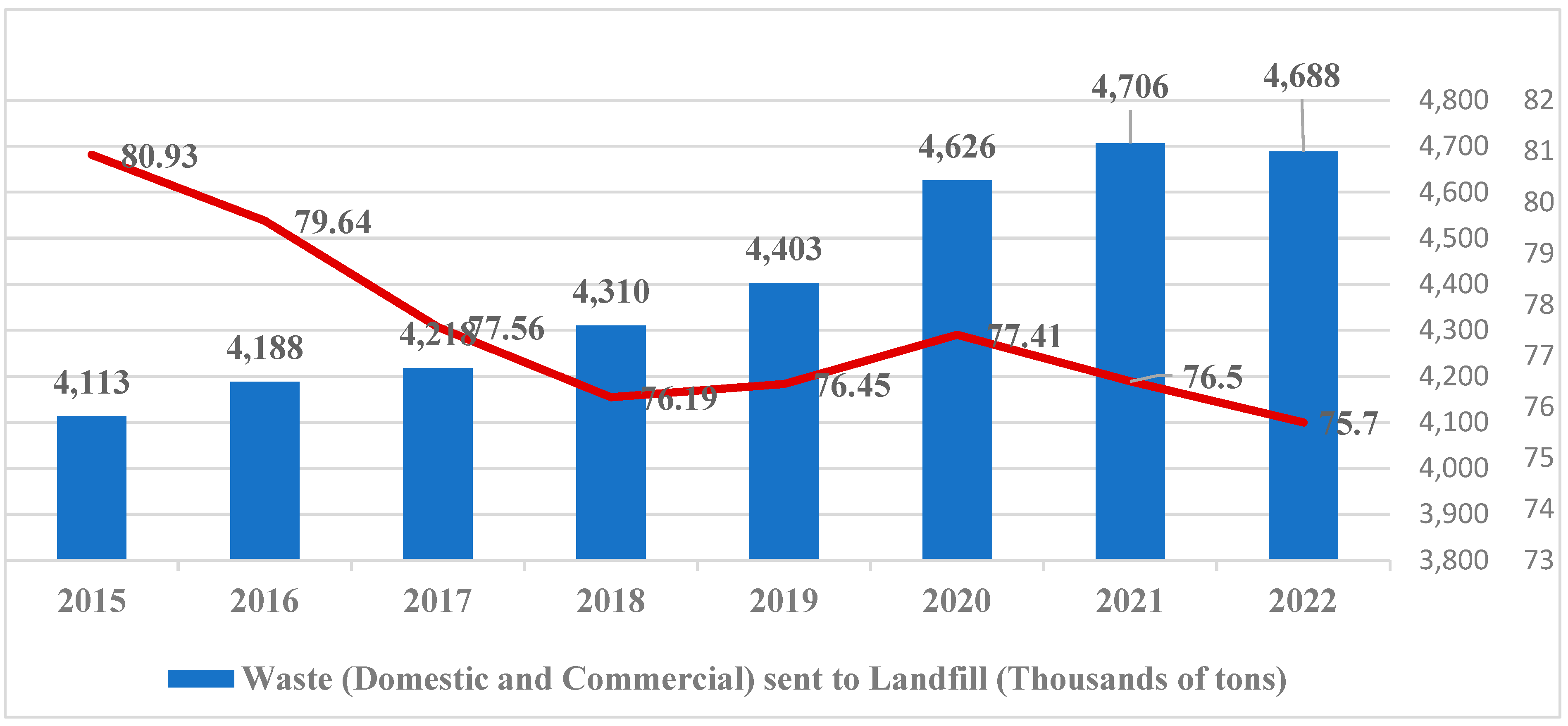

3.1. The Increase in the Amount of Landfill-Disposed Waste in Israel

3.2. Economic Aspects of the Waste Disposal Policy

3.2.1. Waste Disposal Costs

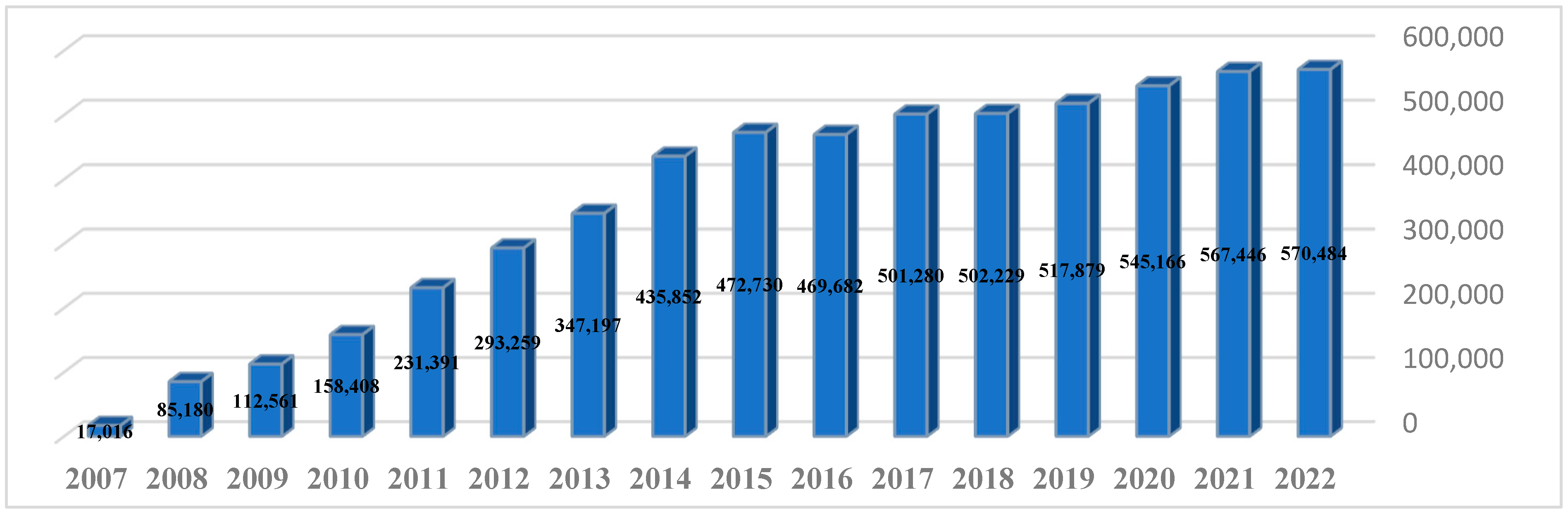

3.2.1.1. Landfill Levy

3.2.1.2. Landfill Entrance Fees and Waste Transportation Costs

3.2.2. The Financial Costs Deriving from the Landfilling Policy and the Cleanliness Maintenance Fund

3.2.3. The Barriers to Transitioning from a Landfill Policy to an Alternative Policy

3.3. Political Aspects of Israel’s Waste Disposal Policy

3.3.1. Deficient Functioning of the Ministry of Environmental Protection

3.3.2. Government Instability in the Ministry of Environmental Protection

3.3.3. Development of a Positivist Worldview in the Government Ministries in General and in the Ministry of Environmental Protection in Particular

4. Conclusions

4.1. An Increase in the Rate of Municipal Use of Landfilling

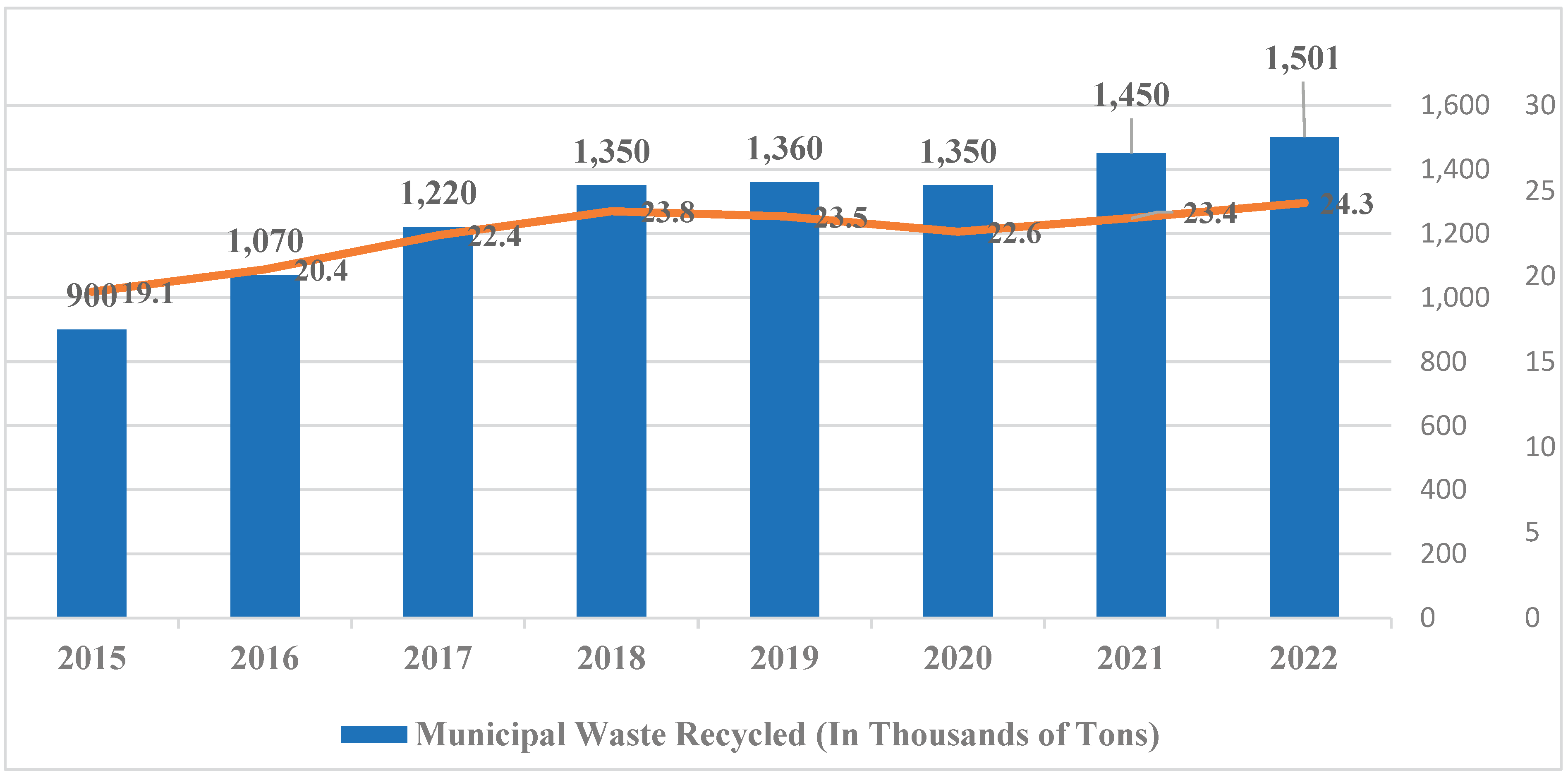

4.2. Low Rate of Waste Recycling as a Proportion of All Municipal Waste

4.3. Economic Factors Affecting the Public Policy for Treating Municipal Waste

4.3.1. The Landfill Levy

4.3.2. The Cleanliness Maintenance Fund

4.4. Political Factors Affecting Public Policy on Treating Municipal Waste

4.4.1. Government Instability in the Ministry of Environmental Protection

4.4.2. Embracing a Positivist Policy by Decision Makers in the Ministry of Environmental Protection

4.4.3. Power and Control Struggles between the Different Government Ministries

Funding

Conflict of Interest

References

- Ahmad, S.Z.; Ahamad, M.S.S.; Yusoff, M.S. Spatial effect of new municipal solid waste landfill siting using different guidelines. Waste Manag. Res. J. Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2013, 32, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H.; McHugh, M.D. Is nursing shortage in Israel inevitable? Isr. J. Heal. Policy Res. 2014, 3, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.S.; Huang, B.; Cui, L. Review of construction and demolition waste management in China and USA. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 264, 110445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayalon, O.; Becker, N.; Shani, E. Economic aspects of the rehabilitation of the Hiriya landfill. Waste Manag. 2006, 26, 1313–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Sasson, M., Raveh, A., Zlatkin, O., & Domb, A. (2022). Mountains of plastic and greenhouse gases: The challenge of lessening landfilling without emissions. Ecology and Environment Journal, 13(1), 1-17. (Hebrew).

- Björklund, A.E.; Finnveden, G. Life cycle assessment of a national policy proposal – The case of a Swedish waste incineration tax. Waste Manag. 2007, 27, 1046–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bong, C.P.C.; Ho, W.S.; Hashim, H.; Lim, J.S.; Ho, C.S.; Tan, W.S.P.; Lee, C.T. Review on the renewable energy and solid waste management policies towards biogas development in Malaysia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, S.; Beymer-Farris, B.; Seay, J.R. Addressing the challenges associated with plastic waste disposal and management in developing countries. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2021, 32, 100682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnley, S. The impact of the European landfill directive on waste management in the United Kingdom. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2001, 32, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- elik, S., & Çorbacıoğlu, S. (2008). Multiple approaches in public policy snalysis: A vritique of positive approach. Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi/Journal of Social Sciences, 32(1).

- Cohen, E. (2016). The nature of Israel’s public policy aimed at curbing the rise in property prices from 2008-2015, as a derivative of the country’s governance structure. Economics & Sociology, 9(2), 73. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. The rise in Israel’s real estate prices: Sociodemographic aspects. Isr. Aff. 2018, 24, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Traffic congestion on Israeli roads: Faulty public policy or preordained? Isr. Aff. 2019, 25, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Israel’s public policy for long-term care services. Isr. Aff. 2020, 26, 889–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Regulating demand or supply: Examining Israel’s public policy for reducing housing prices during 2015–2019. Hous. Policy Debate 2022, 32, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. The unregulated private rental sector and the impact on Israeli housing market. J. Policy Model. 2023, 45, 362–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. The increase in the number of vehicles and the shortage of parking in Israel’s urban areas - economic and political factors. Econ. Sociol. 2023, 16, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Xi, B.; Tan, W. Composting industry under the Chinese municipal solid waste sorting policy: Challenges, opportunities, and directions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 19513–19519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskal, S.; Ayalon, O.; Shechter, M. The state of municipal solid waste management in Israel. Waste Manag. Res. 2018, 36, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinan, T.M. Economic efficiency effects of alternative policies for reducing waste disposal. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1993, 25, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwolatzky, T.; Brodsky, J.; Azaiza, F.; Clarfield, A.M.; Jacobs, J.M.; Litwin, H. Coming of age: Health-care challenges of an ageing population in Israel. Lancet 2017, 389, 2542–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggleston, K. (2020). Demographic and health care challenges. In Fateful decisions, Chapter 6 (pp. 151-179). Stanford University Press.

- Eckstein, Z.; Weiss, Y. On The Wage Growth of Immigrants: Israel, 1990-2000. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2004, 2, 665–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzadkia, M.; Mahvi, A.H.; Baghani, A.N.; Sorooshian, A.; Delikhoon, M.; Sheikhi, R.; Ashournejad, Q. Municipal solid waste recycling: Impacts on energy savings and air pollution. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2021, 71, 737–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.; Fang, M.; Wang, Y. Climate change affects land-disposed waste. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2021, 11, 1004–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, D. Counting the cost of the Intifada: Consumption, saving and political instability in Israel. Public Choice 2003, 116, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowkes, T., May, T., Nash, C., Siu, Y. L., & Rees, P. (2002). Forecasting road traffic growth: Demographic change and alternative policy scenarios. In Transport Policy and the Environment (pp. 50-61). Routledge.

- Friedberg, R.M. The impact of mass migration on the Israeli labor market. Q. J. Econ. 2001, 116, 1373–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendreau, F. (2010). The demographic challenges. Challenges in African Agriculture (p. 9-33).

- Gina, S., Catrinel, D., & Ştefania, A. (2017). The impact of political instability and terrorism on the evolution of tourism in destination Israel. Romanian Economic and Business Review, 12(4), 98-108.

- Goldberg, E. Particularistic considerations and the absence of strategic assessment in the Israeli public administration: The role of the state comptroller. Isr. Aff. 2005, 11, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Yao, Y. Demographic changes and the housing market. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2021, 95, 103734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S. (2015). The challenges of twenty-first-century demography. In Challenges of Aging (pp. 17-29). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

- Hermann, T. (2012). Something new under the sun: Public opinion and decision making in Israel. The Institute for National Security Studies (Hrsg.): Strategic Assessment, 14(4), 41-57.

- James, K.S. India’s demographic change: Opportunities and challenges. Science 2011, 333, 576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klemencic, M.; Fried, J. Demographic challenges and future of the higher education. Int. High. Educ. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollikkathara, N.; Feng, H.; Stern, E. A purview of waste management evolution: Special emphasis on USA. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 974–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, K. S., & Jospe, C. (2017). Climate change is a waste management problem. Issues in Science and Technology, 33(3), 83-88.

- Lavee, D. Is municipal solid waste recycling economically efficient? Environ. Manag. 2007, 40, 926–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavee, D., & Regev, A. (2009). An alternative to landfill tax in Israel. The Economic Quarterly, 56(1), 29-45. (Hebrew).

- Lavee, D.; Regev, U. A proposal for alternative government policy to reduce landfill of household waste in Israel. Isr. Econ. Rev. 2010, 8, 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Lavee, D.; Nardiya, S. A cost evaluation method for transferring municipalities to solid waste source-separated system. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 1064–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Li, X. Waste incineration industry and development policies in China. Waste Manag. 2015, 46, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannie, N., & Bowers, A. (2014). Challenges in determining the correct waste disposal solutions for local municipalities - a South African overview. Civil Engineering= Siviele Ingenieurswese, 2014(9), 17-22. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC161422.

- Mazzanti, M.; Zoboli, R. Waste generation, waste disposal and policy effectiveness: Evidence on decoupling from the European Union. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2008, 52, 1221–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moh, Y.C.; Manaf, L.A. Overview of household solid waste recycling policy status and challenges in Malaysia. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 82, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, C.; Denney, J.; Mbonimpa, E.; Slagley, J.; Bhowmik, R. A review on municipal solid waste-to-energy trends in the USA. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 119, 109512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachmias, D.; Arbel-Ganz, O. The crisis of governance: Government instability and the civil service. Isr. Aff. 2005, 11, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, S.; Berruti, F. Municipal solid waste management and landfilling technologies: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 1433–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissim, I.; Shohat, T.; Inbar, Y. From dumping to sanitary landfills – solid waste management in Israel. Waste Manag. 2005, 25, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okun, B.S. Religiosity and fertility: Jews in Israel. Eur. J. Popul. 2017, 33, 475–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okun, B. S. (2013). Fertility and marriage behavior in Israel: Diversity, change, and stability. Demographic Research, 28, 457-504.

- Orenstein, D.E.; Hamburg, S.P. Population and pavement: Population growth and land development in Israel. Popul. Environ. 2010, 31, 223–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlack, R.D.; Willis, C.E. Multi-objective decision-making in waste disposal planning. J. Environ. Eng. 1985, 111, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, B., Samuel, H., Merkur, S., & World Health Organization. (2009). Israel: Health system review.

- Rosen-Zvi, I. (2007). Whose garbage is it anyway?! Garbage disposal and environmental justice in Israel. Law Studies, 23(2), 487-558. (Hebrew).

- Salhofer, S.; Schneider, F.; Obersteiner, G. The ecological relevance of transport in waste disposal systems in Western Europe. Waste Manag. 2007, 27, S47–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauve, G.; Van Acker, K. The environmental impacts of municipal solid waste landfills in Europe: A life cycle assessment of proper reference cases to support decision making. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 261, 110216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schellekens, J., & Anson, J. (2017). Israel’s destiny: Fertility and mortality in a divided society (pp. 1-12). Routledge.

- Siniscalco, M. T. (2000). Achieving education for all: Demographic challenges.

- State Comptroller. (2022). A report on audit in the local government- waste disposal in the authorities the locality and its burial. Israeli State Comptroller.

- Sumathi, V.; Natesan, U.; Sarkar, C. GIS-based approach for optimized siting of municipal solid waste landfill. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 2146–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szajnbrum, L. (2009). Birth in Israel. International Journal of Childbirth Education, 24(4), 13.

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. SAGE Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, R.; Salmons, R.; Powell, J.; Craighill, A. Green taxes, waste management and political economy. J. Environ. Manag. 1998, 53, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaverková, M.D. Landfill impacts on the environment. Geosciences 2019, 9, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinreb, A. (2020). Population projections for Israel 2017–2040. Policy Paper, 4.

- Weinreb, A., Chernichovsky, D., & Brill, A. (2018). Israel’s exceptional fertility. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

| 1 | This law constitutes an amendment to the federal law legislated as early as 1975. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | The fund was established under section 10 of the Maintenance of Cleanliness Law 1984 and was intended to concentrate financial means for treating environment issues. https://www.gov.il/en/Departments/Guides/maintenance_of_cleanliness_fund

|

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | In 2015, nearly 81% of all waste produced was buried, while in 2021 the burial rate was only 76.5%. |

| 7 | |

| 8 | As part of its commitments to the UN, Israel made a commitment to reduce its emission of greenhouse gasses by 27% until 2030 and by 85% until 2050. |

| 9 | The collection sites charge the landfill levy and a management fee in a single sum, such that the municipalities pay the landfill levy for 100% of the waste collected, while only the relative amount for the waste buried in practice is transferred to the Cleanliness Maintenance Fund. The site operator retains the difference. |

| 10 | The landfill levy amounts are index linked and are updated on January 1st of each year. |

| 11 | State Comptroller (2022). A Report on Audit in the Local Government - Waste Disposal in the Authorities the Locality and its Burial. Israeli State Comptroller. |

| 12 | The audit showed that the difference between the entrance fees to the various landfill sites can be as much as 300%. Moreover, the entrance fees that each landfill charges different clients, including the municipalities, are not uniform, and the difference can be as much as 100%. |

| 13 | Cited from the Maintenance of Cleanliness Law (temporary injunction applied in 2013-2020). |

| 14 | As of 2020, the fund’s revenues derive from four accounts: landfill levies (91.6%), plastic bag account (6.9%), deposit account (0.003?), and general account (1.5%). Source: State Comptroller (2022). |

| 15 | Revenues from the landfill levy were received beginning from the latter half of 2007. |

| 16 | At a rate of only 40% of the fund’s total revenues. |

| 17 | In 2021, a total of 1.6 billion shekels were utilized for goals not included in the strategic plan for management of municipal waste. Source: The Knesset’s Research and Information Center, Budget Control Department, Analysis of the financial reports of the Cleanliness Fund in 2020 and 2021. Page 5, Table 3. |

| 18 | From 2016-2021, a total of 1.66 billion shekels from the fund’s money were transferred to the State Budget and in 2021 the management of the fund approved the transfer of another 600 million shekels in 2022. According to the proposed state budget for 2023 and 2024 – since the money was not transferred in practice, the validity of this decision will be extended until the end of 2024. |

| 19 | Source: https://www.calcalist.co.il/local_news/article/ryo3uydu9 (May 10, 2022). |

| 20 | An organization that encompasses all municipalities in Israel. |

| 21 | |

| 22 | The landfill levy produces about 600 million shekels a year for the Cleanliness Maintenance Fund. |

| 23 | Moreover, it is evident that from 2019 to 2020 there was even a drop in the rate of municipal waste recycling of all waste collected; this may be related to the closure of the Amir transit recycling station in that year. |

| 24 | Five consecutive elections were held in Israel in a short span of only three and a half years (from April 2019 to November 2022). |

| 25 | From 2009 to 2013, Minister for Environmental Protection Gilad Erdan served in this position. From then to the present, seven other ministers have served, as follows: Amir Peretz, Benjamin Netanyahu, Avi Gabay, Ze’ev Elkin, Gila Gamliel, Tamar Zandberg, and Idit Silman (currently). |

| 26 | Link to the draft resolution: https://ynet-pic1.yit.co.il/picserver5/wcm_upload_files/2023/02/18/Hkajxo06o/Seder_Gov_seder_gov2023_n117.pdf

|

| 27 | |

| 28 | |

| 29 | In 2015, 900 thousand tons were sent for recycling, constituting 19% of all municipal waste collected that year, where in 2018 1.35 million tons were recycled, constituting 24% of the total amount of municipal waste collected that year. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).