1. Introduction

a-Amylases (E.C. 3.2.1.1.) are starch-degrading enzymes that hydrolyze the internal a-1,4-O-glycosidic bonds of polysaccharides preserving the a-anomeric configuration of the products. They belong to the glycoside hydrolase enzyme family 13 (GH-13) based on amino acid sequence similarity [

1]. This family is included in the GH-H clan of glycoside hydrolases [

2]. This group of enzymes share a number of common characteristics such as a (b/a)

8 barrel structure, the hydrolysis or formation of glycosidic bonds of the a conformation, and a number of conserved amino acid residues in the active site. a-Amylases are one of the most important industrial enzymes, which are widely used from the conversion of starch into sugar syrups to the production of cyclodextrin for the pharmaceutical industry. They account for 30% of the world's production of enzymes [

3,

4].

Most a-amylases are metalloenzymes that require calcium (Ca

2+) ions for their activity, structural integrity, and stability [

5]. a-Amylases are ubiquitous and produced by plants, animals, and microbes, where they play a dominant role in carbohydrate metabolism. Amylases of plant and microbial origin have been used as food additives for centuries. Barley amylases have been used in beer production. Fungal amylases have been widely used as target foods. Despite the wide distribution, mainly amylases of microbial origin are used in industry (

B. subtilis,

B. stearothermophilus,

B. licheniformis and

B. amyloliquefaciens) due to their cheapness, ease of production and the possibility of modifying and optimizing the production process [

6,

7].

Heterologous and homologous expression of α-amylases from different microbial sources in

B. subtilis (generally recognized as safe (GRAS) in biotechnological applications) is now widely used in the preparation of α-amylase strain-producers and α-amylases based on them [

8,

9,

10,

11]. The demand for α-amylases with diverse physiological and biochemical characteristics across different industries drives the deliberate search for enzymes with novel attributes using recombinant technologies [

12,

13,

14,

15] and enzyme engineering [

16,

17].

The objective of this study is to molecularly clone the α-amylase gene from the B. amyloliquefaciens MDC1974 and B. subtilis MDC3500 strains into the E. coli/B. subtilis pBE-S shuttle vector, express the recombinant enzyme extracellularly and characterize it.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial strains, culture conditions and plasmids

The sources of the α-amylase genes used in this study were the DNAs of B. amyloliquefaciens MDC1974 and B. subtilis MDC3500 strains, which were provided by the microbial depository center of SPC “Armbiotechnology”. The B. subtilis RIK 1285 strain, known for its low protease activity, was used as the host for the expression vector. The E. coli Top10 strain from Invitrogen was employed for the initial transformation and propagation of the expression vector. The pBE-S shuttle vector (E. coli/B. subtilis) from Takara Bio served as the vector for cloning and extracellular expression of the recombinant α-amylase genes.

Bacterial strains were stored either on meat peptone broth agar plates at 4°C or in meat peptone broth supplemented with 50% (v/v) glycerol at -45°C. E. coli or Bacillus strains were cultured on a Sanyo rotary shaker at 150 rpm, maintained at 37°C for E. coli and 33°C for Bacillus, respectively, in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (composed of 1 % peptone, 0.5 % yeast extract, and 0.5 % NaCl). When necessary, LB medium was supplemented with ampicillin at 100 μg/mL for E. coli or kanamycin at 10 μg/mL for B. subtilis. Overnight bacterial cultures were also grown in LB medium for DNA isolation purposes.

2.2. Recombinant DNA techniques and cloning procedures

Recombinant DNA techniques and cloning procedures related to an α-amylase of the

B. amyloliquefaciens MDC1974 strain, as well as the construction of primer pairs adapted for Gibson assembly for cloning the amy1974 gene with and without its own signal peptide, were described previously [

18].

DNA from the B. subtilis MDC3500 strain was purified using the Monarch Genomic DNA Purification Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The following primer pairs were utilized in the Gibson assembly method to clone variants of the target α-amylase gene, both with and without its native signal peptide, into the shuttle vector pBE-S, which carries the aprE signal peptide for extracellular expression of the target genes. For the variant with its own signal peptide, the amy_3500_pBE-S_NdeI_F forward primer (sequence: GCCGGTGCACATATGtttgcaaaacgattcaaaacctctt, with the NdeI recognition sequence underlined) was used. For the variant without its own signal peptide, the amy_3500_pBE-S_Sig_NdeI_F forward primer (sequence: GCCGGTGCACATATGgaaacggcgaacaaatcgaatgag, with the NdeI recognition sequence underlined) was utilized. Both forward primers were paired with the amy_3500T_pBE-S_XbaI_R reverse primer (sequence: ATGGTGATGTCTAGAtcaatggggaagagaaccgctt, with the XbaI recognition sequence underlined). This reverse primer includes a TGA stop codon to ensure the production of the mature protein without a His-tag.

PCR amplification of an α-amylase gene of

B. amyloliquefaciens MDC1974 strain was described previously [

18]. PCR amplification of the α-amylase gene from the

B. subtilis MDC3500 strain was performed under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 minutes; 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 54°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 2 minutes; followed by a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes.

DNA electrophoresis was performed using a 0.8 % agarose gel (Agarose I™, VWR® tablets) in 40 mM Tris-Acetate-EDTA buffer, pH 8.0. The gel was run at 100 volts for 35 minutes. DNA bands were visualized using Millipore's GelRed® nucleic acid stain. NEB's TriDye™ 1 kb Plus DNA Ladder was utilized as a reference for agarose gel sizing.

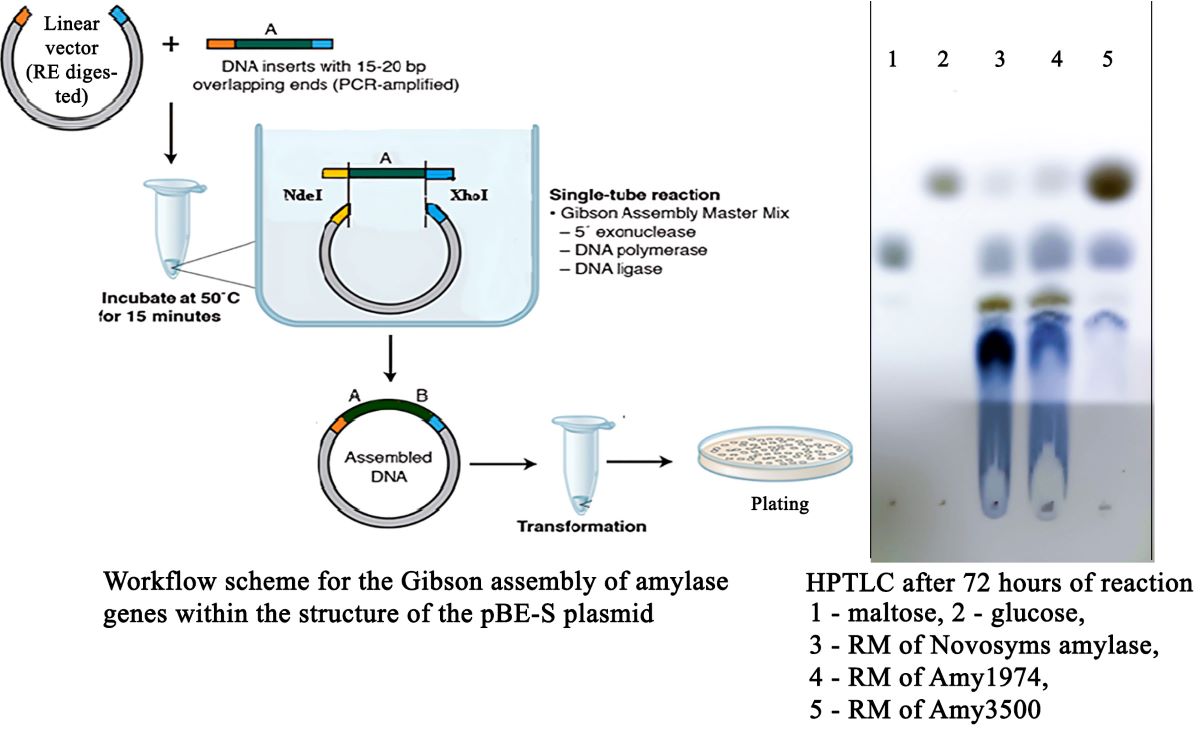

Cloning was performed using the Gibson assembly method [

19]. Initially, the pBE-S vector was double-digested with NdeI and XhoI restriction enzymes according to the manufacturer's instructions (New England Biolabs). The vector, linearized with XbaI and NdeI restriction enzymes, and the amplified genes were introduced into the reaction mixture in the recommended ratio and in a final volume of 10 μl. Subsequently, an α-amylase gene cloning reaction was conducted using NEBuilder® HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix at 50 °C, following the manufacturer's instructions.

2.3. Transformation and obtaining of α-amylase strain producers

Transformation of

E. coli Top 10 cells with pBE-S_amy1974sig and pBE-S_amy1974 vectors was described previously [

18]. The transformation of

E. coli Top 10 cells with synthesized pBE-S_amy3500sig and pBE-S_amy3500 vectors (taken directly from the cloning reaction mixtures) was carried out using the heat shock method. Transformed colonies were selected by growing on LB medium containing ampicillin and were screened using the colony PCR method. Plasmids were isolated using the QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit from QIAGEN, following the manufacturer's instructions (

https://www.qiagen.com/us/products/discovery-and-translational-research/dna-rna-purification/dna-purification/plasmid-dna/qiaprep-spin-miniprep-kit) and stored at -20°C until further use.

Transformation of

B. subtilis RIK 1285 cells with propagated in

E. coli Top 10 cells pBE-S_amy1974sig and pBE-S_amy1974 vectors with obtaining the target

B. subtilis RIK 1285_amy1974sig and

B. subtilis RIK 1285_amy1974 strains was described previously [

18]. Transformation of

B. subtilis RIK 1285 cells with propagated in

E. coli Top 10 cells pBE-S_amy3500sig and pBE-S_amy3500 vectors with obtaining the target

B. subtilis RIK 1285_amy3500sig and

B. subtilis RIK 1285_amy3500 strains was conducted following the manufacturer's – "Takara Bio", instructions with certain modifications (

https://www.takarabio.com/documents/User%20Manual/3380/3380_UM.pdf). The method involves forcing the bacterial cells to enter the stage of sporulation through starvation, which coincides with the stage of competence for cell transformation [

20].

2.4. Fermentation and obtaining of recombinant α-amylases

The optimization and selection of fermentation media for the fermentation of recombinant amylase strains were described previously [

18]. The following optimized fermentation medium was used for the fermentation of recombinant α-amylase strains: 1 % sucrose, 1 % starch, 0.3 % (NH

4)

2SO

4, 0.2 % NH

4Cl, 0.5 % KH

2PO

4, 0.025 % MgSO

4, 1 % yeast autolysate (calculated by dry weight), 40 mg/L L-lysine, 40 mg/L L-tryptophan and 10 mg/L kanamycin. An overnight culture was grown in LB medium at 33°C on a rotary shaker (140 rpm). The overnight culture (seed material) was introduced into the fermentation medium in a volume of 5 %. The fermentation was provided in cotton-stoppered 500 mL wide-mouthed flat-bottomed flasks containing 20 mL each of growth medium (fermentation conditions: 33°C, 220 rpm).

2.5. Determination of enzyme activity

Enzyme activity secreted in the culture fluid was determined by estimating the concentration of reducing groups formed during starch hydrolysis using our own modification [

21] of Sumner's 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) reagent method [

22] (Sumner, 1954), with Miller's modification [

23]. The reaction medium, with a final volume of 0.2 mL, contained 1% (w/v) starch, 50 mM acetate buffer at pH 6.0, 1 mM CaCl₂, and the required amount of enzyme preparation. After 10 minutes of incubation at 55°C, 1 mL of our modified DNS reagent was added, followed by 15 minutes of incubation in a boiling water bath. The optical absorption of the solutions was measured at a wavelength of 546 nm.

The mentioned modifications of the DNS reagent are as follows: Sumner and Sisler's reagent (Sumner, J. B., Sisler, E. B. Arch. Biochem. 4: 333 (1944), cited by [

23]) contained approximately 0.63% dinitrosalicylic acid, 18.2% Rochelle salts (K-Na-tartrate), 0.5% phenol, 0.5% sodium bisulfite, and 2.14% sodium hydroxide. The reagent modified by Miller contained 1% dinitrosalicylic acid, 0.2% phenol, 0.05% sodium sulfite, and 1% sodium hydroxide. If necessary, 1 ml of 40% Rochelle salt is added to 6 ml of the reaction mixture before placing it in a boiling bath. Our modification of the DNS reagent contained per liter: 10 g of DNS reagent, 10 g of sodium hydroxide, and 50 g of potassium sodium tartrate. Immediately before use, 15 mM 2-mercaptoethanol was added to the required volume of the reagent.

One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzed the formation of 1 μmol of reducing groups in one minute under the specified conditions. The amount of protein was estimated using the method of Groves and Davis [

24].

2.6. Partial purification of amy1974 and amy3500 amylases by FPLC and their characterization

The partial purification of Amy1974 and Amy3500 α-amylases, derived from recombinant strains carrying plasmids with and without their signal peptides, was performed using the FPLC NGC Quest 10 Plus system by Bio-Rad on a 1 ml CHT Type I hydroxyapatite column. Each 20 ml of crude enzyme preparation (obtained by centrifugation of the supernatant at 10000 g and filteration through a 0.2 μm Millipore syringe filter) was applied to the 1 ml hydroxyapatite column. The column was then washed with 5 ml of 10 mM sodium phosphate solution at pH 7.0, followed by elution step with a 10 ml sodium phosphate linear gradient ranging from 10 to 400 mM at pH 7.0.

SDS electrophoresis was carried out in 12.5 % polyacrylamide gel in presence of 0.1% SDS and at pH 8.9 by Bio-Rad protocol. The pH 8.3 Tris–glycine buffer was used in electrode chambers. The BLUeye pre-stained protein ladder (Merck, USA) was used for molecular weight determination. Protein was stained with 0.1% solution of Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 according to Bio-Rad recommendations (

https://www.bio-rad.com/webroot/web/pdf/lsr/literature/ Bulletin_6040.pdf).

2.7. Methods used for enzyme characterization

To determine the dependence of enzyme activity on temperature, the activity was measured at the specified temperatures.

The dependence of enzyme activity on pH was determined in solutions of citrate, phosphate, and borate (50 mM each) at the specified pH. The pH was measured in a separately prepared full reaction mixture with a higher volume (sufficient for pH measurement) to ensure accuracy.

To determine thermal stability, the enzyme preparation was incubated for 20 minutes at the specified temperature (in a water-based ultrathermostate), then cooled to 4°C, and the remaining activity was measured under the previously mentioned conditions.

The dependence of enzyme thermal stability on pH was determined as follows: the enzyme preparation was incubated for 20 minutes in a solution containing citrate, phosphate, and borate (20 mM each) at the specified pH (measured as mentioned above), then cooled to 4°C, and the remaining activity was measured under the previously mentioned conditions.

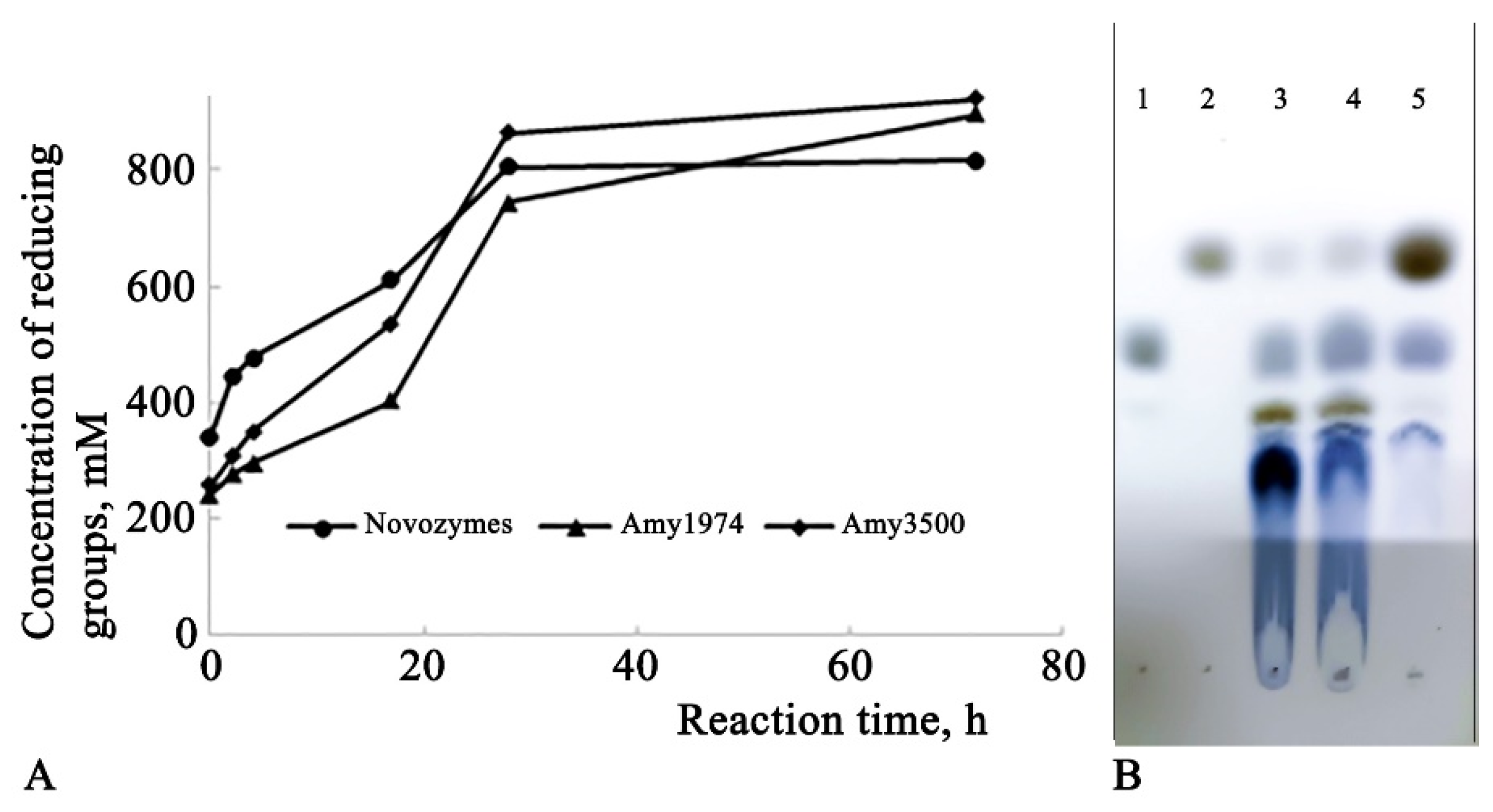

To determine the depth of the hydrolysis reaction conducted by the studied enzyme preparations, corn starch hydrolysis was performed with 15% starch solutions in the presence of 1 mM CaCl2 at pH 6.0. The quantity of α-amylases was calculated as ten times the amount needed to complete the reaction in 24 hours. Twenty percent of the calculated enzyme preparations were added to the reaction mixtures, which were then heated to 80°C (to gelatinize the starch). After cooling down to 55°C, the remaining portions of the enzymes were added to the reaction mixtures, and the yield of reducing groups was monitored using the DNS assay. The HPTLC was performed on “HPTLC Silica gel 60 F254” plates by two subsequent runs in butanol/acetone/water (4:5:1) and butanol/formic acid/water (4:8:1) elution systems. Chromatograms were visualized by aniline staining.

2.7. Statistical analysis

The results represent mean values of three measurements. Calculations were done using the Microsoft Office Excel software package.

3. Results

3.1. InterPro analysis of amylase genes and the application of the obtained information for designing primer pairs

The primer pair synthesized based on the alpha-amylase gene of

B. subtilis strain ZJ-1 (GenBank accession number JX081246) was able to produce a similarly sized amplicon from the DNA isolated from the

B. amyloliquefaciens MDC1974 strain (amy1974). The Eurofins-sequenced amy1974 gene exhibits 99% identity with the amyZJ-1 gene (Figure S1) according to BLAST analysis, whereas the amino acid BLAST shows 100 % identity between the two proteins (GenBank accession number PP976357, protein_id="XCI78649.1"). The InterPro analysis of

B. amyloliquefaciens MDC1974 α-amylase is presented in Figure S2 (

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/) [

25]. According to this analysis, the product of amy1974 gene belongs to the thermostable α-amylase family (IPR013776). It contains a signal peptide (SIGNALP_GRAM_POSITIVE SignalP-TM), the glycosyl hydrolase family 13 catalytic domain (IPR006047), and a C-terminal domain associated with prokaryotic alpha-amylases (IPR015237). Additionally, the provided analyses revealed that this protein belongs to the glycoside hydrolase superfamily (IPR017853). Amy1974sig (variant with signal peptide) contains 514 amino acids and has a theoretical pI of 5.74 and a molecular weight of 58.4 kDa, whereas Amy1974 (without signal peptide) contains 483 amino acids and has a theoretical pI of 5.31 and a molecular weight of 54.8 kDa, according to Expasy calculations (

https://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/). These calculations are based on signal peptide cutting site determinations by SignalP-5.0 software (

https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/SignalP-5.0/) as provided in Figure S5(B) and Table S1 [

26]. The obtained information was used to construct primer pairs for cloning the amy1974 gene with and without its own signal peptide.

The 16S rRNA gene sequence of the B. subtilis MDC3500 strain (GenBank: MT534524) demonstrates 99% identity to the corresponding gene sequence of the Bacillus sp. KBS0812 strain, with complete genome sequence (GenBank: CP041757.1). The primer pair synthesized based on the α-amylase gene of the Bacillus sp. KBS0812 strain was able to produce functional acidic α-amylase of B. subtilis MDC3500 (amy3500). The Eurofins-sequenced amy3500 gene (GenBank: OK490393) exhibits 98% identity, with 3 gaps and a 10-nucleotide shift, compared to the α-amylase gene of the Bacillus sp. KBS0812 strain (Figure S3) according to BLAST analysis. In contrast, the amino acid sequence of amy3500 (UUZ04253.1) is 100% identical to the corresponding amino acid sequence of the Bacillus sp. KBS0812 α-amylase. InterPro analysis of the B. subtilis MDC3500 α-amylase is presented in Figure S4. According to this analysis, the amy3500 gene features four signatures of the catalytic domain of the α-amylase family (IPR006046). It contains a signal peptide (SIGNALP_GRAM_POSITIVE SignalP-TM), the glycosyl hydrolase family 13 catalytic domain (IPR006047), the α-amylase/branching enzyme C-terminal all-beta domain (IPR006048), and the starch-binding module 26 domain (IPR031965). Additionally, the analysis revealed that this protein belongs to the glycoside hydrolase superfamily (IPR017853) by its catalytic domain, to the glycosyl hydrolase superfamily (IPR013780) by its all-beta domain, and to the immunoglobulin-like fold superfamily (IPR013783) by its starch-binding module 26 domain. Amy3500sig (variant with signal peptide) contains 659 amino acids and has a theoretical pI of 5.80 and a molecular weight of 72.4 kDa, whereas Amy3500 (without signal peptide) contains 626 amino acids and has a theoretical pI of 5.53 and a molecular weight of 68.9 kDa, according to Expasy calculations. These calculations are based on signal peptide cutting site determinations by SignalP-5.0 software as provided in Figure S5(C) and Table S1. The obtained information was used to construct primer pairs for cloning the amy3500 gene with and without its own signal peptide.

3.2. Cloning the amy1974 and amy3500 genes in pBE-S shuttle vector with and without their own signal peptides

The pBE-S shuttle vector utilized in this study is depicted in Figure S6(A). It encompasses the kanamycin and ampicillin resistance sites, the ColE1 and pUB origins, as well as the aprE promoter and signal peptide of the subtilisin protease, which are located upstream from the multiple cloning site (MCS) and the His tag sequence.

PCR amplification and cloning of an α-amylase gene of

B. amyloliquefaciens MDC1974 strain was described previously [

18].

Cloning of the amy3500sig and amy3500 variants of the α-amylase PCR amplified genes from the B. subtilis MDC3500 strain into the shuttle vector pBE-S was accomplished using Gibson's assembly method. For this purpose, the quantities of the vector linearized with XbaI and NdeI restriction enzymes and the amplified gene introduced into the reaction mixture were calculated as 0.03 and 0.06 picomoles per 10 μl of the reaction mixture, respectively. An α-amylase gene cloning reaction was then conducted using NEBuilder® HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix at 50 °C according to the manufacturer's instructions. The manufacturer's recommended 15-minute incubation was extended to 40 minutes. As a result, pBE-S_amy3500sig and pBE-S_amy3500 vectors, with and without the own signal site respectively, were obtained. DNA electrophoresis diagrams of the pBE-S_amy3500sig and pBE-S_amy3500 vectors are presented in Figure S6(B).

3.3. Transformation of B. subtilis RIK 1285 cells and preparation of α-amylase strain producers

Transformation of

B. subtilis RIK 1285 cells with propagated in

E. coli Top 10 cells pBE-S_amy1974sig and pBE-S_amy1974 vectors with obtaining the target

B. subtilis RIK 1285_amy1974sig and

B. subtilis RIK 1285_amy1974 strains was described previously [

18].

To obtain an Amy3500 α-amylase-secreting strain producer, B. subtilis RIK 1285 cells were transformed with pBE-S_amy3500sig and pBE-S_amy3500 vectors propagated in E. coli cells. Given that the B. subtilis RIK 1285 strain is auxotrophic for lysine and tryptophan, the casamino acids recommended by Takara Bio were replaced by L-lysine and L-tryptophan at 40 mg/L each during the stage of obtaining competent cells of that strain. According to the method, circular plasmid is added to the competent cells and gently shaken for 90 minutes on a rotary shaker. Experiments have indicated that transformation occurs only after shaking for 90 minutes followed by static conditions for another 60 minutes. Under these conditions, the efficiency of natural transformation of the competent strain with pBE-S_amy3500sig and pBE-S_amy3500 vectors was 2.8 × 10^2 and 2.5 × 10^2 CFU/µg DNA, respectively. The results of colony PCR identification of pBE-S_amy3500sig and pBE-S_amy3500 B. subtilis RIK 1285 transformants are shown in Figure S6(C). After conducting the work, B. subtilis RIK 1285_amy3500sig and B. subtilis RIK 1285_amy3500 strains producing α-amylase were obtained.

3.4. Optimization of recombinant α-amylase fermentation conditions and preparation of partially purified amylase samples from four described strains

The optimization and selection of the composition of the fermentation medium using the active transformants carrying the pBE-S_amy1974 vector with the gene lacking its own signal peptide were described previously [

18]. The optimization of fermentation media and conditions included the source of organic nitrogen, intensity of aeration, the concentration of kanamycin, and the duration of fermentation. The optimized conditions are detailed in the materials and methods section. Since the target amylase genes were similarly regulated by the expression system used (pBE-S vector and

B. subtilis RIK 1285 host), the derived conditions were applied to all strains of recombinant amylases.

The enzymatic activities resulting from the flask fermentation (3x20 ml of each) of the four obtained α-amylase secreting strains are documented in

Table 1.

Interestingly, the α-amylase activity of B. subtilis RIK 1285_amy1974 showed almost a twofold increase compared to the activity of B. subtilis RIK 1285_amy1974sig. The activities of B. subtilis RIK 1285_amy3500 and B. subtilis RIK 1285_amy3500sig strains were found to be similar. However, all four strains exhibited significantly higher α-amylase activity compared to the host strain.

3.5. Partial purification of obtained α-amylase preparations by FPLC on hydroxyapatite

Partial purification of α-amylase preparations was performed according to the procedure described in the Materials and Methods section. The results are presented in Figure S7. In all four cases, the main enzymatic activity (more than 90%) was observed in fractions 7 and 8, with fraction 7 exhibiting more activity. The specific activities in 7th fraction were as follows: Amy1974 reached 1000 U/mg, Amy1974sig reached 1400 U/mg, Amy3500 reached 500 U/mg, and Amy3500sig reached 600 U/mg.

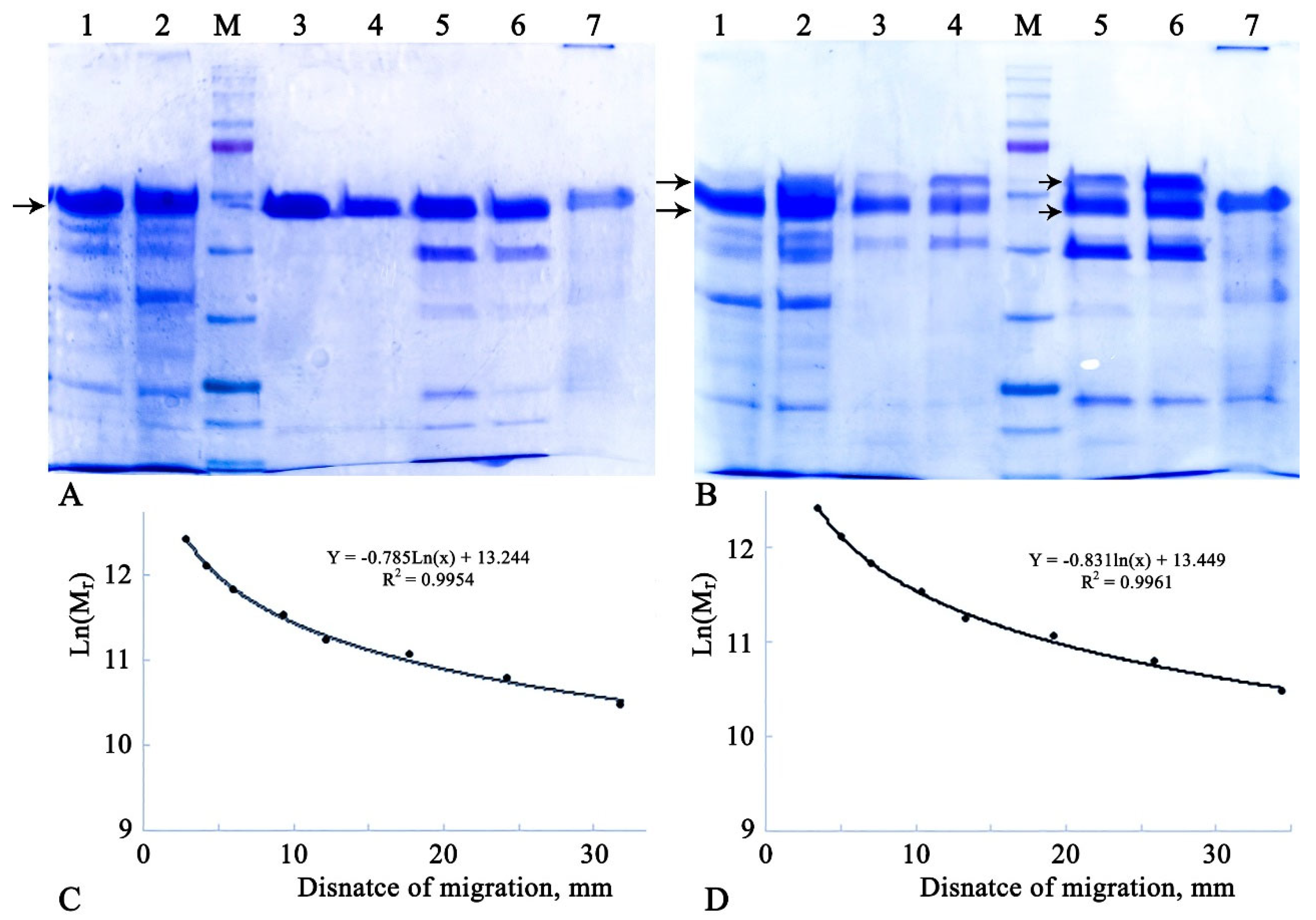

3.6. SDS-PAGE characterization of partially purified Amy1974 and Amy3500 α-amylase samples

The FPLC-purified α-amylase preparations, along with respective controls (crude extracts, FPLC fractions 7 and 8, and extracellular proteins from the host strain grown under the same conditions for 48 hours), were characterized by SDS-PAGE. The results are presented in

Figure 1.

From

Figure 1(A), it is evident that all six studied variants of Amy1974 showed similar molecular weights, averaging 54,626.6 ± 460.7 Da compared to the 54,838.47 Da calculated by Expasy based on sequence and bioinformatics data. Taking into account that the molecular weight of the full enzyme was calculated as 58.4 kDa, it can be concluded that the enzyme is secreted from

B. subtilis RIK 1285 cells without any signal peptide (whether from the vector or a combination of the vector and its own signal peptides).

The results presented in

Figure 1(B) show a more complicated picture. For all six studied variants of Amy3500, the enzyme activity is represented by two spots, with average molecular weights of 64007.1 ± 925.6 and 55038.1 ± 478.5 Da. However, the Expasy-calculated molecular weights revealed 72377.9 and 68875.6 Da for variants with and without the signal peptide, respectively. Nevertheless, the obtained results indicate that the presence of the native signal peptide, along with another signal peptide from the expression vector, does not affect the exact molecular weights of the secreted α-amylase variants but significantly decreases the amount of the heavier (64 kDa) protein.

3.7. Catalytic properties of the obtained Amy1974 and Amy3500 preparations

The effect of Ca2+ concentration on variants of α-amylase activities is presented in Figure S8. These data indicate that Amy1974 at a concentration of 0.2 mM Ca2+ and Amy3500 at a concentration of 0.1 mM Ca2+ showed maximum activity, respectively. However, the effect of this metal is not significant and falls within the 20-30% range. Furthermore, dialysis of these enzyme preparations against buffer solutions with and without 1 mM CaCl2 indicates a negligible activating effect of Ca2+ on both Amy1974 and Amy3500 α-amylases.

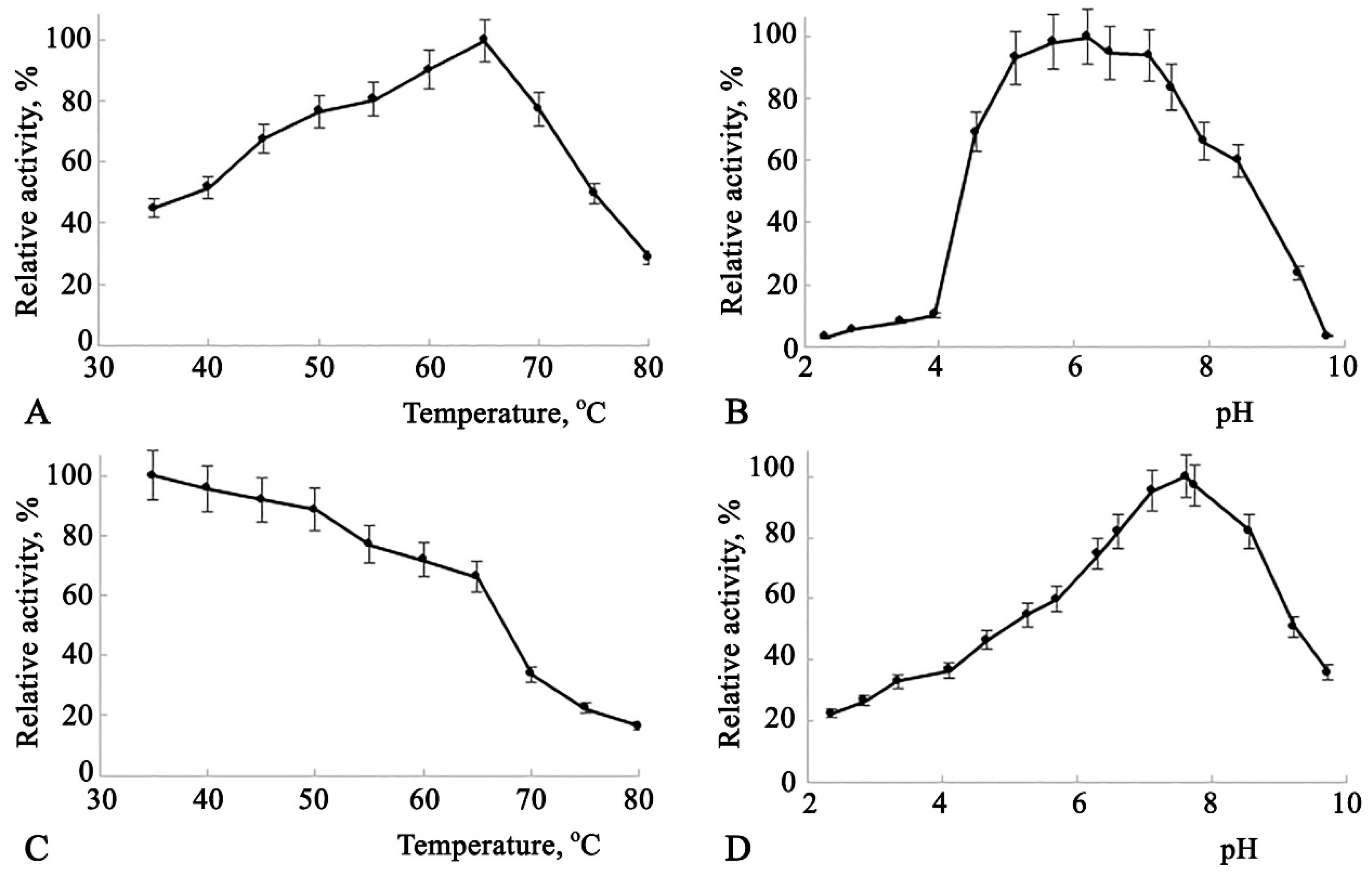

Some catalytic characteristics of Amy1974 are presented in

Figure 2.

The dependence of enzyme activity on temperature (

Figure 2(A)) shows a broad activity range between 50°C and 70°C, peaking at 65°C. The enzyme activity dependence on pH also demonstrates high activity across a broad pH range of 4.7 to 7.9, with the peak at pH 6.5 (

Figure 2(B)). The enzyme's thermal stability dependence on temperature is represented by a declining line, where enzyme activity decreases by nearly 25% in the 35°C to 65°C range. A 50% recovery of enzyme activity after a 20-minute incubation was observed at 68°C (

Figure 2(C)). This incubation condition was utilized to study the enzyme's thermal stability dependence on pH. As shown in

Figure 2(D), the enzyme exhibits greater stability at pH levels between 6.5 and 8.2, with the peak at pH 7.6.

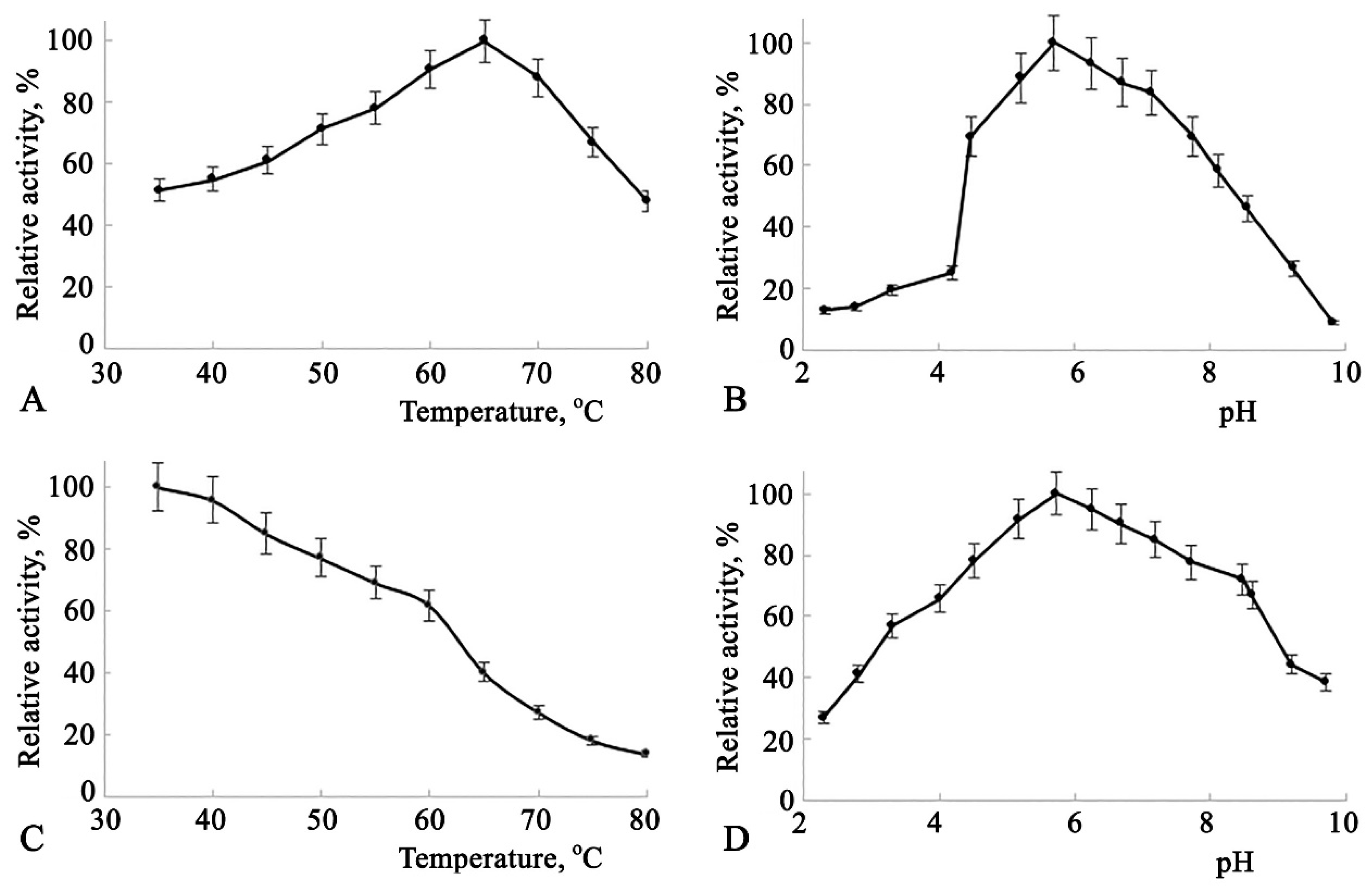

All the aforementioned catalytic characteristics were also studied for Amy3500 and are presented in

Figure 3.

The dependence of enzyme activity on temperature (

Figure 3(A)) shows a broad activity range between 60°C and 70°C, peaking at 65°C. The enzyme activity dependence on pH also demonstrates high activity across a broad pH range of 5.0 to 7.5, with a peak at pH 5.8 (

Figure 3(B)), showing some shift to the acidic range of pH. The enzyme's thermal stability dependence on temperature is represented by a declining trend, where enzyme activity decreases by nearly 39% in the 35°C to 60°C range. A 50% recovery of enzyme activity after a 20-minute incubation was observed at 63°C (

Figure 3(C)). This incubation condition was utilized to study the enzyme's thermal stability dependence on pH. As shown in

Figure 3(D), the enzyme exhibits greater stability at pH levels between 4.7 and 7.7, with a peak at pH 5.9, showing a significant shift to the acidic range of pH.

Amy1974 and Amy3500 α-amylases were tested for activity against various substrates. The results are presented in

Table 2.

The depth of hydrolysis of 15% corn starch was evaluated for Amy1974 and Amy3500 α-amylases in comparison with Novozymes Liquoflow® Go 2X α-amylase. The results are presented in

Figure 4.

The obtained results show that although Novozymes amylase initially demonstrates higher activity (immediately after gelatinization), the Amy1974 and Amy3500 α-amylases soon reach and surpass the reaction depth of the Novozymes enzyme within 72 hours. Additionally, while Amy1974 produces an end-product pattern on HPTLC similar to that of Novozymes α-amylase, Amy3500 nearly entirely converts the starch into glucose.

4. Discussion

In this study, we presented the cloning, extracellular expression, and characterization of two amylases – Amy1974 of

B. amyloliquefaciens MDC1974 and Amy3500 of

B. subtilis MDC3500. The unrelatedness of

B. amyloliquefaciens and

B. subtilis strains was shown in 1967 [

27]. Specifically, hybrid formation between

B. subtilis W23 and

B. amyloliquefaciens F DNA revealed only 14.7 to 15.4% DNA homology between the two species. The comparison of amino acid sequences of Amy1974 and Amy3500 studied in this research is presented in Figure S9. This comparison indicates very low similarity between the studied proteins' amino acid sequences, with 22% identities, 36% positives, and 25% gaps.

Despite such strong differences, both amylases belong to the glycosyl hydrolase family 13 by their catalytic domain (IPR006047) and have different C-terminal all-beta domains, with an additional substrate-binding domain in the case of the B. subtilis enzyme, according to InterPro analysis. At the superfamily level, InterPro reveals that both enzymes belong to the glycoside hydrolase superfamily (IPR017853) by their catalytic domain. However, they have different all-beta domains, and Amy3500 additionally contains an immunoglobulin-like fold superfamily (IPR013783) starch-binding module 26 domain.

The NCBI Protein BLAST search of Amy1974 revealed 10 protein hits with more than 99% sequence identity with subject motifs. Among them were one representative each from

Proteus mirabilis,

Escherichia coli, and

Bacillus velezensis, with the others being

B. amyloliquefaciens species. Among these hits, two

B. amyloliquefaciens species with NCBI Reference Sequences WP_041481726.1 and 3BH4_A, and a

P. mirabilis species with NCBI Reference Sequence WP_013352208.1, showed 100% sequence identity with Amy1974. In the case of the

B. amyloliquefaciens 3BH4_A NCBI Reference Sequence, the 1.4 Å resolution pdb file 3bh4 was obtained and characterized [

28].

Similarly, the NCBI Protein BLAST search of Amy3500 revealed 20 protein hits with more than 99% sequence identity with subject motifs. Most of them were representatives of

B. subtilis species. Among these protein hits, the protein with NCBI Reference Sequence WP_003234692.1 showed 100% sequence identity with Amy3500. The crystal structure of

B. subtilis α-amylase, in complex with the pseudotetrasaccharide inhibitor acarbose, was thoroughly characterized with 2.3 Å resolution and is available under pdb file 1ua7 [

29].

Cloning of the desired genes was carried out using Gibson assembly with the NEBuilder® HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix [

19]. This method has apparent advantages over classical cloning [

30], Golden Gate cloning [

31], and TA-cloning [

32]. In contrast to these methods, when using Gibson assembly, the researcher does not need to cut the target gene amplicon with restriction enzymes. This additional step, characteristic of the alternative cloning methods mentioned, can be troublesome if the target gene contains restriction sites required for cloning.

The nature of the signal peptide has a crucial effect on the mode and quantity of target protein secretion. The secretory systems of

B. subtilis are well-studied [

33,

34]. In this study, we used the Takara proprietary pBE-S

B. subtilis/

E. coli shuttle vector, carrying the AprE protease signal peptide, for cloning and future secretory expression of amy1974 or amy3500 α-amylase genes (which have their own signal peptide motifs in their sequence). We utilized the opportunity to obtain variants with the AprE signal peptide, either in conjunction with or without the cloned amylase signal peptides, and subsequently studied the effect on the secretion of target enzymes. Bioinformatics analyses revealed that all three signal peptides – AprE, Amy1974, and Amy3500 – belong to the same Sec/SPI type of signal peptides with probabilities of 0.77, 0.86, and 0.90, respectively, according to SignalP-5.0 software calculations (Figure S5, Table S1). The SDS-PAGE analysis indicated identical molecular weights for both α-amylases, regardless of the presence of their own signal peptide in the final plasmid construct (

Figure 1). However, fermentations revealed nearly a two-fold increase in the final volumetric activity of Amy1974 without its own signal peptide, compared to the variant with double signal peptides, whereas the Amy3500 amylase signal peptide variants exhibited nearly the same volumetric activity. PrsA, a post-translocation chaperone, helps the folding of proteins secreted through the Sec secretion system [

10,

35]. Therefore, the observed anomalies related to the α-amylase signal peptide form may be associated with this chaperone.

SDS-PAGE analysis of recombinant Amy1974 and Amy3500 α-amylase samples, with and without their own signal peptides in the respective plasmid constructs, indicates a clear shortening of both variants of Amy3500 to the same extent, while Amy1974 remains intact after secretion (

Figure 1). Moreover, Amy3500 is secreted in two shortened forms with molecular weights of 64.0 and 55.0 kDa, instead of the variant with 68.9 kDa, when the signal peptide part is removed after secretion. This corresponds to a shortening of nearly 42 and 121 amino acids from the C-terminus for the 64.0 and 55.0 kDa variants, respectively. It should also be noted that in the case of Amy3500 (variant without its own signal peptide), the majority of the enzyme is in the 55.0 kDa form, whereas in the case of Amy3500sig, the ratio of the 64.0 and 55.0 kDa forms is nearly 3 to 5. This phenomenon is widespread among α-amylases, which, along with the obligatory A (catalytic), B (loop), and C (all-beta) domains, possess a C-terminal substrate-binding domain. For example, truncation of 186 amino acid residues at the carboxyl-terminal region of α-amylase from

B. subtilis X-23 did not influence its enzymatic characteristics (molar catalytic activity, amylolytic pattern, transglycosylation ability, effect of pH on stability and activity, optimum temperature, and raw starch-binding ability), except that the thermal stability of the shorter variant was higher than that of the longer one [

36]. For

Bacillus sp. strain TS-23, it was shown that up to 98 amino acids from the C-terminal end of the α-amylase could be deleted without significantly affecting raw-starch hydrolytic activity or thermal stability [

37]. For

Bacillus sp. KR8104, it was shown that in α-amylase secretion, the N-terminal 44 amino acids and C-terminal 193 amino acids were lost without significantly influencing optimum pH, thermal stability, or the quality of end-products of starch hydrolysis [

38].

In flask fermentations, the α-amylase activity of B. subtilis RIK 1285_amy1974 was estimated to reach 1834 U/ml, while the activity of B. subtilis RIK 1285_amy3500 reached 702 U/ml after 48 hours of fermentation. However, under production conditions in a submerged 250 L bioreactor during pilot-scale fermentation, the volumetric activity of the B. subtilis RIK 1285_amy1974 strain reached 2000 U/ml after 25 hours of fermentation [

21].

The study of the effect of Ca

2+ concentration on Amy1974 and Amy3500 activities, as well as dialysis data, indicates a low activating effect of Ca

2+ on both α-amylases. However, X-ray crystal analysis shows the presence of 8 Ca

2+ ions in the

B. amyloliquefaciens pdb 3bh4 α-amylase structure, which is 100% identical to Amy1974 in amino acid sequence [

26], and the presence of 3 Ca

2+ ions in the

B. subtilis pdb 1ua7 α-amylase structure, which is 100% identical to Amy3500 in amino acid sequence [

27]. This observation may indicate the existence of tightly bound Ca

2+ ions in the studied α-amylase structures, which explains the low activating effect of Ca

2+ on both α-amylases.

The comparison of the catalytic characteristics of Amy1974 and Amy3500 α-amylases with similar enzymes known in the literature reveals the advantages of our preparations in terms of working pH and relatively wide ranges of pH-dependent thermostability. The enzymes are also moderately thermophilic and exhibit wide operating temperature ranges. For comparison, out of 32 studied α-amylases, only 4 exhibit broad operating temperature ranges (

Halobacillus sp. strain MA-2: 30-50°C,

Bacillus sp. isolate ANT-6: 37-80°C,

Bacillus sp. PS-7: 37-60°C, and

Bacillus licheniformis: 40-80°C), and only 2 exhibit broad pH optima (

Nocardiopsis sp.: pH 5-8.6 and

Trichoderma pseudokoningii: pH 4.5-8.5) [

4]. The enzymes studied in this investigation exhibited broad activity peaks between 45-70°C, with a maximum at 65°C. The Amy1974 and Amy3500 α-amylases demonstrated broad pH optima and pH-dependent thermostability, with optimum pH values at 6.5 and 5.8, and thermal stability peaks at pH 7.6 and 5.9, respectively. Both α-amylases displayed high relative activity against various starches, including corn amylopectin and potato amylose, while showing comparatively lower activity towards cyclodextrins.

The α-amylases presented in this work show interesting behavior in terms of the depth of the starch hydrolysis reaction. While Amy1974 hydrolyzes starch, similar to the Novozymes preparations used in production, to short dextrose and maltose, Amy3500 α-amylase converts starch almost completely to glucose. This is an important factor in terms of obtaining high-glucose-containing syrups from starch using only an α-amylase.

5. Conclusions

The amino acid sequences of the α-amylase genes, Amy1974 from B. amyloliquefaciens MDC1974 and Amy3500 from B. subtilis MDC3500 strains, were analyzed using InterPro software to elucidate the family and superfamily profiles of these valuable industrial enzymes. Additionally, primer design was performed for cloning the respective genes, both with and without their own signal peptides, along with the host plasmid signal peptide.

Both α-amylase genes were molecularly cloned into the E. coli/B. subtilis pBE-S shuttle vector, both with and without their own signal peptides. For recombinant Amy3500, the amylase variants resulted in similar levels of volumetric activity. In contrast, the expression of Amy1974 nearly doubled compared to Amy1974sig, which had double signal peptides. The molecular weight of Amy1974 α-amylase was consistent with the theoretical molecular mass calculations. However, the estimated molecular weight of Amy3500 amylase was significantly reduced upon exiting the producer cells.

Ca²⁺ had no significant activating effect on the activities of Amy1974 amylase and Amy3500 amylase, likely due to its tight binding to the protein scaffold. Therefore, this ion can be omitted from technological processes involving the studied enzymes.

Both enzymes exhibited broad activity peaks, with a maximum at 65°C. The Amy1974 and Amy3500 α-amylases also demonstrated broad pH optima and pH-dependent thermostability. Both α-amylases displayed high relative activity against various starches while showing comparatively lower activity toward cyclodextrins.

The Amy1974 amylase converts starch into dextrins of varying lengths and maltose, whereas Amy3500 converts starch almost entirely into glucose. This is an important fact from a resource-saving perspective, as this enzyme can be used for starch saccharification alone, without the need for glucoamylase, thereby eliminating the requirement to adapt the process to different temperature and pH optima for various enzymes.