1. Introduction

Thyroid cancer (TC) is a malignancy that has significantly increased in frequency worldwide in recent years, especially in the most developed countries [

1]. Among the various types of thyroid cancer, papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) is the most common, predominantly affecting women compared to men with a 3:1 ratio [

1]. The typical procedure for the initial evaluation of nodular thyroid disease involves cytopathological analysis by percutaneous fine needle aspiration biopsy. This procedure has limitations, it is invasive, time-consuming, and often inaccurate, particularly because it may yield false-negative results for large thyroid nodules and is not suitable to repeating applications for a tumor follow-up [

2]. Thus, to minimize patient harm and enhance diagnostic precision and specificity, it is crucial to develop a non-invasive, well-tolerated method for identifying PTC. Liquid biopsy is minimally invasive detection method, with potential application to several diseases, including PTC. However, there are currently no specific biomarkers available for PTC. Liquid biopsy can provide extracellular vesicles (EVs) and represents a simpler, minimally invasive alternative to needle biopsy. EVs are small, membrane-bound nanoparticles secreted by almost all cell types in various fluids, including blood, urine, and saliva. Their significant role in cancer biology is documented, with implications for tumor growth, metastasization, and the developing of drug resistance and immune evasion [

3,

4,

5]. Because of these findings, EVs have garnered considerable interest as potential cancer biomarkers. They possess various characteristics that make them promising candidates, for example: (i) EVs are shed from all cell types in the organism; (ii) molecules contained in EVs, including proteins, lipids, DNA, mRNAs, and microRNAs (miRNAs), are components of the cells from which the EVs originate and reflect their physiological or pathophysiological status; (iii) the molecular cargo of EVs can be influenced by their microenvironment [

5,

6,

7]. Moreover, EVs in liquid biopsy are informative pathological specimens more easily accessible than tissue samples obtained by traditional methods such as needle aspiration or surgical biopsies.

Recent advances in cancer research have been achieved on various fronts, and one of these is the study of the Chaperone System (CS) [

8,

9]. The chief components of the CS are the molecular chaperones, some of which are called heat shock protein (Hsp). These are involved in many physiological mechanisms in normal cells and are present inside EVs secreted by cancer cells. Hsps released by cancer derived EVs play a role in human cancer development and immune system stimulation, and their levels in the cancer cells may be modulated by specific miRNAs [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Based on these premises, chaperone associated miRNAs in circulating EVs can be considered promising biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and patient monitoring.

In the past decade, there has been growing interest in the study of noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs), a class of RNA molecules that perform several regulatory functions within cells and include miRNAs, which are involved in the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression. miRNAs are dysregulated in different types of human tumors, suggesting a role as tumor promoters or tumor suppressors. Because of this, the levels of miRNAs have been determined in various cancer types [

6,

12,

14,

15]. For example, the levels of circulating miRNAs in patients with thyroid cancer have been measured in a search for diagnostic biomarkers [

6,

16,

17].

The study reported here focused on the levels of miRNAs contained within EVs, taking advantage of the fact that the EVs’ phospholipid bilayer protects RNA from circulating RNAses. We determined the levels of miR-1, miR-206, and miR-221 in patients with papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) and compared them with the levels in a control group constituted of patients with benign goiter (BG). We focused on miR-1 and miR-206 because of their known involvement in the regulation of expression of the gene encoding the molecular chaperone Hsp60 [

18], a protein implicated in the tumorigenesis of PTC [

19,

20,

21], and we also focused on miR-221 because it is usually augmented in PTC [

22,

23,

24,

25]. The levels of these three miRNAs were measured in EVs extracted from the plasma of patients with PTC and BG both before and after thyroidectomy surgery. The data were also compared with those obtained from EVs isolated from the culture medium of a PTC cell line (MDA-T32).

Once the experimental data were obtained, a bioinformatics analysis was carried out to predict the target genes of the miRNAs examined to better understand the possible dysregulated pathways which lead to the development of thyroid neoplasia and tumor progression via metastatic dissemination.

The data obtained from plasma, culture medium, and bioinformatic analysis reinforced the idea that miR-1 and miR-206 are promising candidates as thyroid cancer-specific biomarkers, particularly considering their association with Hsp60 expression. In addition, analysis of miR-221 within EVs confirmed data in the literature indicating that the levels of miRNAs in circulation are elevated in PTC patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

The patients recruited for this study underwent surgery at the Department of Oncological Surgery of the University Hospital of Palermo P. Giaccone between 2020 and 2021. The Ethics Committee of University Hospital AUOP Paolo Giaccone of Palermo approved the study (Approval Number: N. 05/2017 of 05/10/2017) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave their written informed consent. Twelve patients were studied, seven with papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) and five with non-toxic benign goiter (BG), the latter used as controls. Two blood samples were taken from each patient, one on the day of surgery before the operation (BS, before surgery) and a second (after surgery, AS) on the day of release from the hospital (1 week later).

2.2. Cell Culture

Human papillary thyroid carcinoma cells (MDA-T32 CRL-3351, ATCC) were grown in RPMI (Roswell Park Memorial Institute) 1640 medium (Gibco-Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100g/mL streptomycin, 1x MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids solution (Gibco-Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 2mM L-glutamine, in a humidified 37˚C atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

2.3. EVs Isolation from Plasma

Whole blood was collected in EDTA tubes from each subject and plasma was separated by centrifugation at 2,000 xg for 20 minutes. Plasma samples were centrifuged at 11,000 xg for 30 minutes at 4°C to remove cell debris and large particles. Subsequently, the samples were diluted 1:1 with cold PBS (Phosphate-buffered saline), to reduce its viscosity, and filtered with 0,22 μm pore filters. Next, the samples were ultracentrifuged at 110,000 xg for 2 hours at 4°C. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was resuspended in cold PBS and ultracentrifuged at 110,000 xg for 2 hours at 4°C. Finally, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet resuspended in two aliquots: (a) in 100μL of radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer for Western Blot analysis (the entire procedure was carried out on ice to prevent protein degradation; and (b) in 100 μL of PBS for miRNA extractions or biophysical characterization of EVs

[26].

2.4. EVs Isolation from Cell Culture Medium

When MDA-T32 cells in culture reached 80% confluence, they were starved by growing them in medium without FBS for 24 hours. Afterwards, cell culture medium was collected for EVs isolation. Fifteen ml of cell culture medium were first centrifuged at 800 xg, for 10 minutes at 4°C, to remove death cells; then, the supernatant was recovered and further centrifuged at 13,000 xg for 20 minutes at 4°C to remove cell debris and mitochondrial contaminants. At the end of this step, the supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.22 μm pore filter. The filtered supernatant was ultracentrifuged for 2 hours, at 11,000 x g at 4°C. After ultracentrifugation, the supernatant was discarded, while the EV-pellet was collected and resuspended in 100μL of RIPA buffer for Western blot analysis, or in 100 μL of PBS for miRNA extractions or biophysical characterization of EVs.

2.5. EVs Characterization

2.5.1. NanoSight™ Particle Tracking Analysis

Nanoparticle size distribution and concentration were measured using a NanoSight NS300 instrument. The instrument was equipped with a 488 nm laser, a high sensitivity sCMOS camera and a syringe pump. EV samples were resuspended in PBS and then diluted in particle-free PBS (filtered through 20 nm filters) to generate a dilution in which 20-120 particles per frame were tracked, to obtain a concentration within the recommended measurement range (1-10 × 108 particles/ml). Five experiment videos of 60-s duration were analyzed using NTA 3.4 Build 3.4.003 (camera level 15–16).

2.5.2. Size Distribution Determined by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

were pipetted after thawing and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove eventual aggregates or dust. The supernatant was placed at 20 °C in a thermostated cell compartment of a Brookhaven Instruments BI200-SM goniometer, equipped with a He-Ne laser (JDS Uniphase 1136P) tuned at 633 nm and a Hamamatsu single-pixel photon counting module (mod. C11202-050). Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) measurements have been acquired as previously described [

27]. The size distribution Pq(σ) of vesicles is calculated by assuming that the diffusion coefficient distribution is shaped as a Schultz distribution, which is a two-parameter asymmetric distribution, determined by the average diffusion coefficient ¯D (σz is the diameter corresponding to ¯D) and the polydispersity index PDI [

27,

28]. The analysis was performed by using two species: the former to consider the contribution from small particles around 20 nm or less (proteins or small molecules), the latter for the contribution assigned to vesicles.

2.5.3. Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (STEM)

The purified EVs were resuspended in PBS. Then, the EV preparations were mounted on a formvar nickel grid (200 mesh squares grid) by layering the grids over 10 μl drops of EV preparations to allow adherence of particles to the grids, and they were incubated overnight at 24ºC. Grid-mounted preparations were prepared for contrast staining by treating them with 1% uranyl acetate (w/v) for 5 minutes. After washing with methanol twice for 5 minutes, a filter paper was used to blot away the excess liquid from the grids, then the grids were treated with Reynold’s solution for 3 minutes [

26]. Finally, the grids were rinsed in distilled water twice for 5 minutes. After this procedure, the grids were ready to be observed and photographed under a scanning electron microscope (SEM) FEI-Thermo Fisher Versa 3D equipped with a retractable STEM detector.

2.6. Protein Extraction, Quantification, and Western Blot Analysis

Western blot was performed to detect the presence of typical EV-associated proteins to confirm the presence of EVs in the biological sample. EVs obtained by ultracentrifugation, were lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer, containing 50mM Tris/HCl,150mM NaCl,1% NP-40, 1mM EGTA and supplemented with Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) (1mM AEBSF, 1μM Aprotinin, 50μM Bestatin, 15μM E-64, 20μM Leupeptin, 10μM Pepstatin A). The procedure was carried out on ice to prevent protein degradation. EV lysates were then homogenized by pipetting up and down several time on ice for 1 hour. To obtain only the whole protein suspension, lysates were centrifuged at 16,000 x g for 20 minutes. The supernatant was collected and stored in new tubes at -20°C. Total proteins concentration present on EVs was determined by using the Bradford assay and a standard Western blot procedure was performed using the following antibodies: anti-CD81; anti-Alix; anti-Calnexin (

Table 1). Each experiment was performed at least three times.

2.7. miRNA Extraction, Retro Transcription, and Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

miRNAs from EVs isolated from the cell culture medium and plasma samples of patients were obtained using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The concentration of the miRNA-enriched fractions was determined using Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 2000 1-position Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA). cDNA was synthesized using miRCURY LNA RT Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) and the Applied BiosystemsTM VeritiTM 96-Well Thermal Cycler (Fisher Scientific, MA, USA. Afterward, Real-Time PCR was performed by using the miRCURY LNA SYBR®Green PCR Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Reactions were carried out by adding primers specific for human miR-1-3p, miR-206, miR-221-3p, and miR-16-1-3p, the latter was used as a housekeeping internal control (

Table 2).

Real-Time PCR assays were performed on the real-time PCR cycler Rotor-Gene Q (QIAGEN). The miRNA levels were normalized to the levels obtained for miR-16-1-3p, used as housekeeping control. Changes in the transcript level were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.8. Bioinformatic Analysis

To validate the data obtained experimentally, a bioinformatics analysis was performed to better understand the potential significance of our findings. The analysis, performed on TargetscanHuman 8.0 and then supported by the data in the literature on Pubmed, predicts the targets of miRNAs that were found to be up regulated in thyroid cancer and specifically in PTC.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses of miRNA expression levels were performed using the GraphPad Prism 8.8 package (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test for plasma data. On the other hand, for data from the cell line, statistical analysis was performed using the unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. All data are presented as mean ± SD, and the level of statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of EVs

EVs were isolated from the plasma of 12 patients and from cell culture medium of the MDAT32 cell line. NTA, DLS, and STEM were performed for biophysical and morphological characterization of EVs. With the NTA measurements the purified EVs showed a size distribution in the expected range of 100-124 nm, typical of EVs (Figure 1). DLS measurements were performed to further characterize particle size distribution of EVs. From the size distribution, it was confirmed that the EVs had a size range of 120 - 130 nm (Figure 1). Since morphology is another important property that distinguish EVs, the STEM method was used to define the morphology and shape of the EVs obtained from all groups studied. The images demonstrated the typical round shape morphology of EVs (Figure 1).

Isolated EVs were also characterized by Western blotting, to detect different EV markers such as ALIX and CD81. As expected, this analysis confirmed: (a) The presence of CD81 and Alix in EVs isolated from both the plasma samples and cell culture medium of the MDAT32 cell line; and (b) The absence of CD81 and Alix in cell lysate (Figure 1).

To assess the purity of isolated EVs, the absence of calnexin was also demonstrated. Calnexin is an endoplasmic reticulum protein, which is cell specific and is expected to be absent in EVs. As expected, this analysis confirmed: (a) The absence of calnexin in the EVs; and (b). The presence of calnexin in the cell lysates (Figure 1).

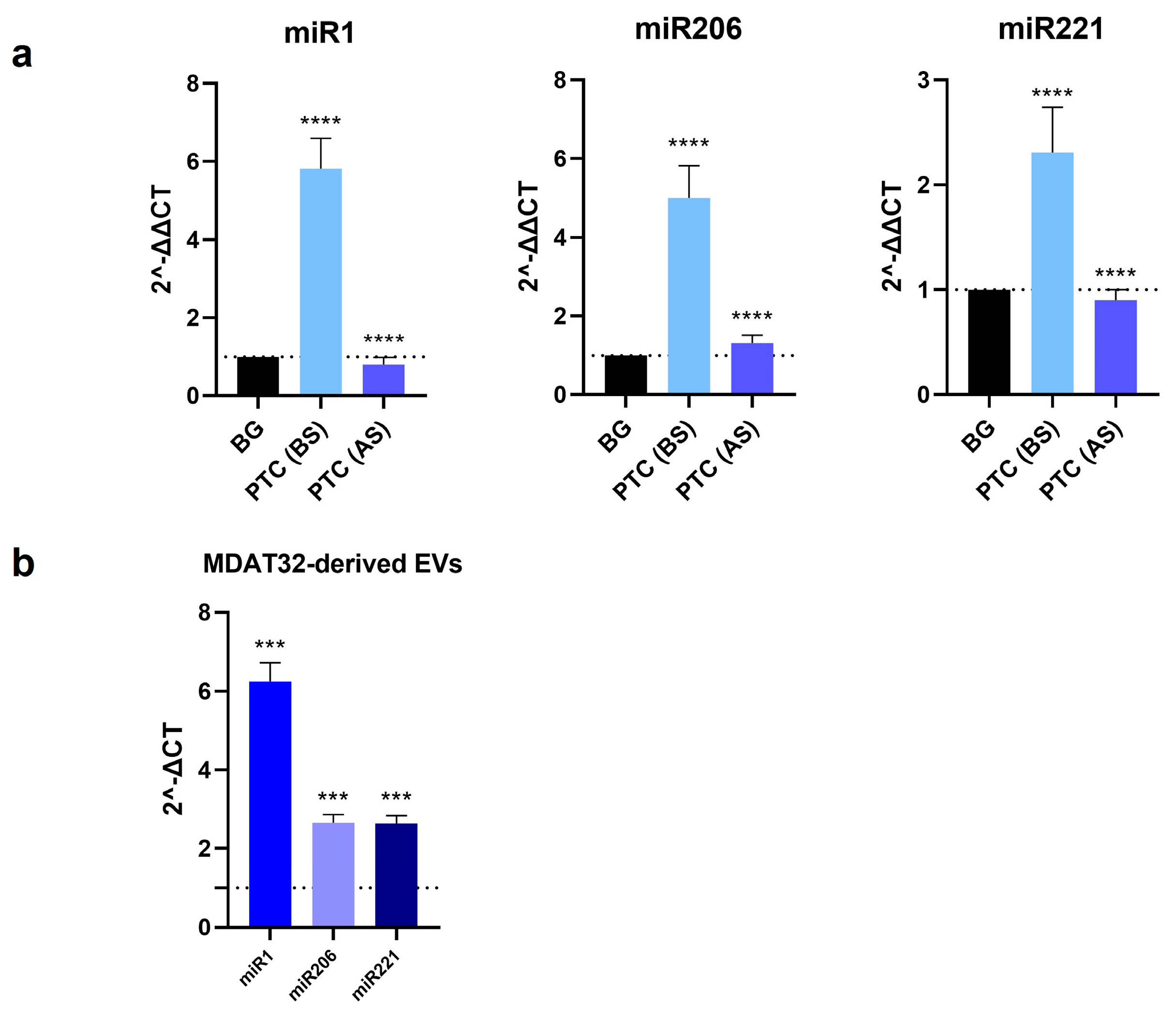

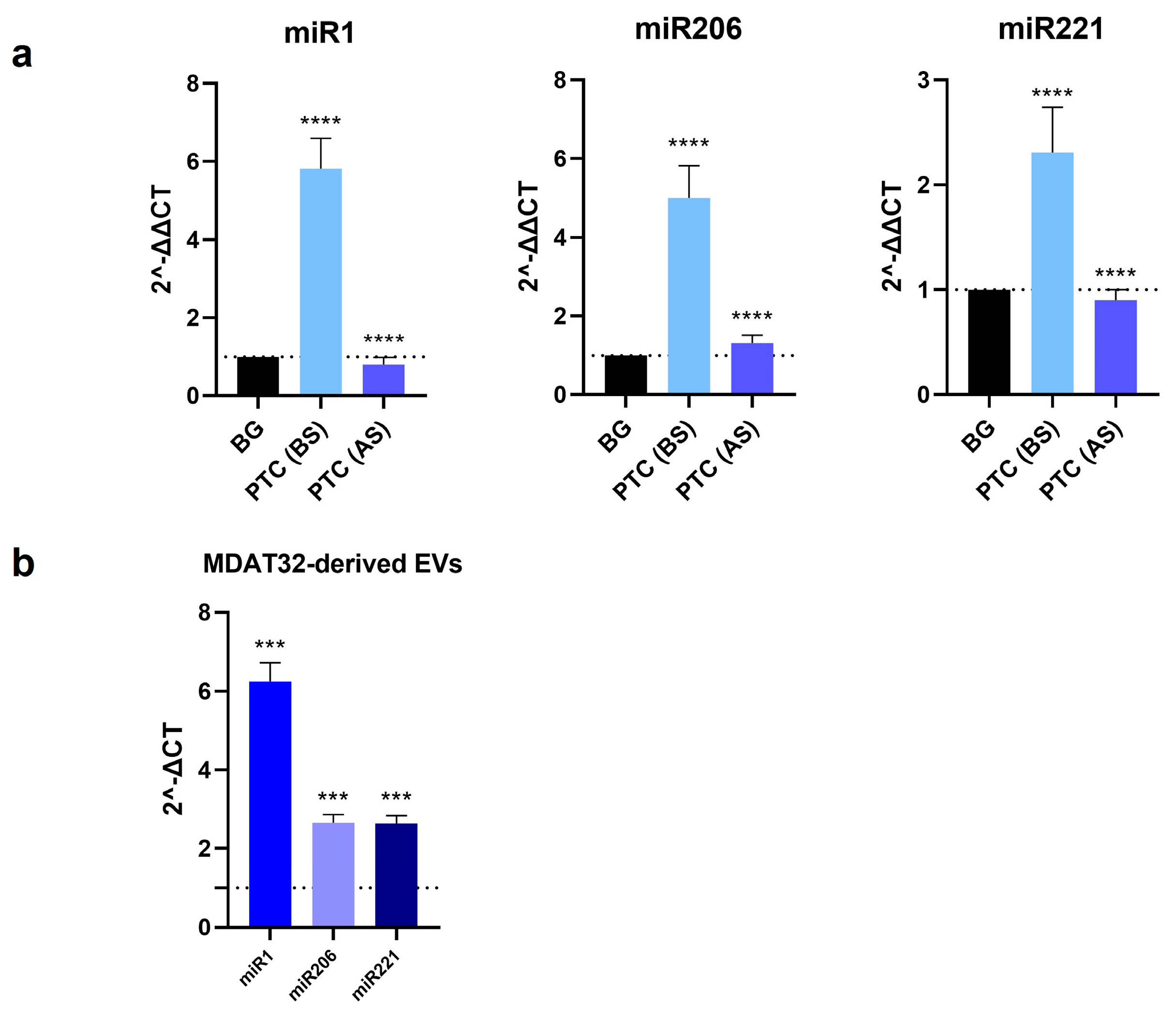

3.2. Evaluation of microRNAs Levels in EVs

To identify potential miRNA-based biomarkers for PTC, we evaluated the levels of specific miRNAs isolated from both MDAT32-derived EVs and EVs isolated from plasma samples of patients with PTC and BG (before and after surgery). The results showed that the levels of miR1, miR206, and miR221 within plasma derived EVs were significantly higher in patients with PTC than in BG controls. In patients with PTC, following surgery there was a decrease in the levels of all three miRNAs analyzed. The levels of miR1, miR206, and miR221 in MDAT32-derived EVs were also significantly higher (Figure 2).

3.3. miRNA Targets Prediction for Thyroid Cancer-Associated Genes

The results obtained for each miRNA analyzed are presented in

Table 3. The Total Context Score on TargetScan is a metric used to assess the potential of a miRNA binding site to regulate a target gene. This score integrates various factors that influence the effectiveness of miRNA-mediated gene regulation, including complementarity between the seed region of the miRNA and the binding site on the target mRNA, location and accessibility of the binding site, and number of binding sites. When the total context score is negative and low, the probability that miRNA affects target gene expression is higher [

29]. The conducted bioinformatic analysis shows the genetic targets of the studied miRNAs that may contribute to the development and progression of TC.

4. Discussion

The incidence and morbidity of thyroid cancer have increased over the past decades [

30], consequently, the search for useful biomarkers is becoming more and more necessary for developing accurate diagnostic and patient-monitoring tools. There is growing evidence showing involvement of miRNAs in thyroid cancer [

6,

17,

24]. Among the miRNAs frequently dysregulated in thyroid cancer, miR-1 and miR-206 are particularly important because of their role in regulating Hsp60, a member of the CS involved in the progression of PTC. To date, the diagnostic accuracy of miRNAs in PTC has not been conclusively established, demanding further studies. The aim of the present study was to explore whether the levels of three miRNAs (miR-1-3p, miR-206, and miR-221-3p) in EVs isolated from the plasma (liquid biopsy) of patients with PTC would be consistently elevated and, thus, serving as diagnostic biomarkers. Additionally, we explored the potential mechanisms involving miR-1 and miR-206 in PTC through bioinformatic analysis. Patients with PTC were compared with patients with BG, before and after the surgical removal of the thyroid. EVs were characterized by dynamic light scattering (DLS), and STEM and nanotracking particle analyses to verify the presence of vesicles with a size of 100-120 nm. Western blotting was performed to detect specific EV-markers like CD81 and Alix. We focused on miR221 because it is deregulated in thyroid carcinomas and promotes cancer cell migration and invasion [

31,

32]. In addition, we focused on miR1 and mir206, which are predicted to regulate Hsp60 expression, a chaperonin involved in the development of thyroid cancer [

18,

19,

20]. Previous works showed that Hsp60 is elevated in carcinoma tissues [

33,

34,

35] and is found at high levels in plasma from subjects with PTC [

19]. The MDAT32 cell line also showed high levels of Hsp60 (data not shown).

The levels of miR-1-3p, miR-206, and miR-221-3p were significantly higher in patients with PTC before surgery (BS) compared to control patients (BG). Also, the levels of miRNAs before surgery were higher than levels after surgery (AS). Therefore, the data indicate that these miRNAs, which were chosen for this study because they might be involved in thyroid tumorigenesis [

12,

19], are promising biomarkers for diagnosis and monitoring of PTC patients.

Bioinformatic analysis revealed, among the miRNA target genes examined, the presence of genes involved in tumorigenesis (e.g., MET, HDAC4, VEGFA, TP53BP2), in cell cycle regulation (e.g., CCND2, CDKN1B, CDKN1C), and in apoptosis (e.g. CAAP1, BCL2L11).

Specifically, MET is implicated in cell proliferation and is often overexpressed in tumors, and HDAC4 influences chromatin structure and regulates cancer proliferation and progression [

36,

37,

38]. CCND2 is a member of the cyclin family that binds to cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), promoting cell progression from G1 to S phase of the cell cycle. The dysregulation of this process can lead to uncontrolled cell proliferation, a common feature of cancer cells [

39]. In contrast, CDKN1B and CDKN1C are cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors that usually act as tumor suppressors, but their regulation is altered during tumor processes [

40].

Targets also included genes that influence tumor diffusion via metastasis such as TAGLN2 involved in Transgelin 2 protein expression, the alteration of which can affect tumor cell migration [

41]. Furthermore, chaperonins protect tumor cells from stress, allowing them to survive and proliferate [

20], and the bioinformatics analysis revealed HSPD1 (the molecular chaperone or chaperonin type I Hsp60) and CCT5 subunit (component of the type II CCT chaperonin) among the target genes of the miRNAs examined.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the findings of this study align with the increasing body of literature suggesting that microRNAs (miRNAs) are implicated in tumorigenesis, including thyroid cancer [

42]. The results indicate that miR-1-3p, miR-206, and miR-221-3p, present in extracellular vesicles (EVs) isolated from the plasma of patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), are significantly elevated before surgery compared to controls and show a notable decrease post-surgery. These observations highlight the potential of these miRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers and tools for monitoring disease progression in PTC. Additionally, bioinformatic analysis identified several target genes associated with cancer-related processes, such as tumorigenesis, cell cycle regulation, and apoptosis. These insights underscore the necessity for further investigation into the clinical utility of miRNAs in the context of thyroid cancer.

Author Contributions

FC, FR, CCB and CCampanella—contributions to conception and design; GDA, RS, FS and CCB—performed experiments and analyzed data; GDA, RS, GG, GGraceffa, CCipolla, FS SR, MM, ECdeM, AJLM and CCB —been involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically; SR and MM —performed DLS experiments and analyzed data; GGraceffa, CCipolla, FS SR, MM, ECdeM, AJLM, FC, FR CCB and CC —contributed to manuscript editing. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be ac-countable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Euro-Mediterranean Institute of Science and Technology (IEMEST), Palermo, Italy, and University of Palermo, Italy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospital AUOP Paolo Giaccone of Palermo approved the study (Approval Number: N. 05/2017 of 05/10/2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Goodarzi, E.; Moslem, A.; Feizhadad, H.; Jarrahi, A.; Adineh, H.; Sohrabivafa, M.; Khazaei, Z. Epidemiology, Incidence and Mortality of Thyroid Cancer and Their Relationship with the Human Development Index in the World: An Ecology Study in 2018. Advances in Human Biology 2019, 9, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, C.; Martorana, F.; Pennisi, M.S.; Stella, S.; Massimino, M.; Tirrò, E.; Vitale, S.R.; Di Gregorio, S.; Puma, A.; Tomarchio, C.; et al. Opportunities and Challenges of Liquid Biopsy in Thyroid Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 7707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti, G.; Sánchez-López, C.M.; Andres, A.; Santonocito, R.; Campanella, C.; Cappello, F.; Marcilla, A. Molecular Profile Study of Extracellular Vesicles for the Identification of Useful Small “Hit” in Cancer Diagnosis. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 10787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Rappa, F.; Fucarino, A.; Pitruzzella, A.; David, S.; Campanella, C. Exosomes: Can Doctors Still Ignore Their Existence? EuroMediterranean Biomedical Journal 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Hou, X.; Hao, J.; Zhang, W.; Shi, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ruan, X.; Zheng, X.; Gao, M. METTL3 Inhibition Induced by M2 Macrophage-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Drives Anti-PD-1 Therapy Resistance via M6A-CD70-Mediated Immune Suppression in Thyroid Cancer. Cell Death Differ 2023, 30, 2265–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delcorte, O.; Craps, J.; Mahibullah, S.; Spourquet, C.; D’Auria, L.; Van Der Smissen, P.; Dessy, C.; Marbaix, E.; Mourad, M.; Pierreux, C.E. Two MiRNAs Enriched in Plasma Extracellular Vesicles Are Potential Biomarkers for Thyroid Cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2022, 29, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardente, S.; Aventaggiato, M.; Splendiani, E.; Mari, E.; Zicari, A.; Catanzaro, G.; Po, A.; Coppola, L.; Tafani, M. Extra-Cellular Vesicles Derived from Thyroid Cancer Cells Promote the Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) and the Transfer of Malignant Phenotypes through Immune Mediated Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macario, A.J.L.; Conway de Macario, E. Chaperonins in Cancer: Expression, Function, and Migration in Extracellular Vesicles. Semin Cancer Biol 2022, 86, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paladino, L.; Vitale, A.; Santonocito, R.; Pitruzzella, A.; Cipolla, C.; Graceffa, G.; Bucchieri, F.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.; Rappa, F. Molecular Chaperones and Thyroid Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Campanella, C.; Bucchieri, F.; Cappello, F. Extracellular Heat Shock Proteins in Cancer: From Early Diagnosis to New Therapeutic Approach. Semin Cancer Biol 2022, 86, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Lo Cascio, F.; Mocciaro, E.; Vitale, A.M.; Vergilio, G.; Pace, A.; Cappello, F.; Campanella, C.; Palumbo Piccionello, A. Curcumin Affects HSP60 Folding Activity and Levels in Neuroblastoma Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graziano, F.; Iacopino, D.G.; Cammarata, G.; Scalia, G.; Campanella, C.; Giannone, A.G.; Porcasi, R.; Florena, A.M.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.L.; et al. The Triad Hsp60-MiRNAs-Extracellular Vesicles in Brain Tumors: Assessing Its Components for Understanding Tumorigenesis and Monitoring Patients. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, G.; Santonocito, R.; Vitale, A.M.; Scalia, F.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Campanella, C.; Bucchieri, F.; Cappello, F.; Caruso Bavisotto, C. Air Pollution: Role of Extracellular Vesicles-Derived Non-Coding RNAs in Environmental Stress Response. Cells 2023, Vol. 12, Page 1498 2023, 12, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Che, J.; Cao, B. Isolation and Identification of MiRNAs in Exosomes Derived from Serum of Colon Cancer Patients. J Cancer 2017, 8, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budakoti, M.; Panwar, A.S.; Molpa, D.; Singh, R.K.; Büsselberg, D.; Mishra, A.P.; Coutinho, H.D.M.; Nigam, M. Micro-RNA: The Darkhorse of Cancer. Cell Signal 2021, 83, 109995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, K.; Li, Y.; Song, E.; et al. Circulating MicroRNA Profiles as Potential Biomarkers for Diagnosis of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012, 97, 2084–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankovic Miljus, J.; Guillén-Sacoto, M.A.; Makiadi-Alvarado, J.; Wert-Lamas, L.; Ramirez-Moya, J.; Robledo, M.; Santisteban, P.; Riesco-Eizaguirre, G. Circulating MicroRNA Profiles as Potential Biomarkers for Differentiated Thyroid Cancer Recurrence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2022, 107, 1280–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, Z.-X.; Lin, Q.-X.; Deng, C.-Y.; Zhu, J.-N.; Mai, L.-P.; Liu, J.-L.; Fu, Y.-H.; Liu, X.-Y.; Li, Y.-X.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; et al. MiR-1/MiR-206 Regulate Hsp60 Expression Contributing to Glucose-Mediated Apoptosis in Cardiomyocytes. FEBS Lett 2010, 584, 3592–3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Cipolla, C.; Graceffa, G.; Barone, R.; Bucchieri, F.; Bulone, D.; Cabibi, D.; Campanella, C.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Pitruzzella, A.; et al. Immunomorphological Pattern of Molecular Chaperones in Normal and Pathological Thyroid Tissues and Circulating Exosomes: Potential Use in Clinics. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladino, L.; Santonocito, R.; Graceffa, G.; Cipolla, C.; Pitruzzella, A.; Cabibi, D.; Cappello, F.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.L.; Bucchieri, F.; et al. Immunomorphological Patterns of Chaperone System Components in Rare Thyroid Tumors with Promise as Biomarkers for Differential Diagnosis and Providing Clues on Molecular Mechanisms of Carcinogenesis. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.S.; Chung, K.-W.; Young, M.S.; Kim, S.-K.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, E.K. Differential Protein Expression of Lymph Node Metastases of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Harboring the BRAF Mutation. Anticancer Res 2013, 33, 4357–4364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ye, T.; Zhong, L.; Ye, X.; Liu, J.; Li, L.; Yi, H. MiR-221-3p and MiR-222-3p Regulate the SOCS3/STAT3 Signaling Pathway to Downregulate the Expression of NIS and Reduce Radiosensitivity in Thyroid Cancer. Exp Ther Med 2021, 21, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Xie, L.; Chen, X.; Yang, Y.; Peng, Q. Biomarker Value of MiR-221 and MiR-222 as Potential Substrates in the Differential Diagnosis of Papillary Thyroid Cancer Based on Data Synthesis and Bioinformatics Approach. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 794490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zheng, J.; Li, J.; Wu, X. MiR-221, a Potential Prognostic Biomarker for Recurrence in Papillary Thyroid Cancer. World J Surg Oncol 2017, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, W.; Chang, Q.; Lu, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, C. MiR-221-3p Facilitates Thyroid Cancer Cell Proliferation and Inhibit Apoptosis by Targeting FOXP2 Through Hedgehog Pathway. Mol Biotechnol 2022, 64, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santonocito, R.; Paladino, L.; Vitale, A.M.; D’Amico, G.; Zummo, F.P.; Pirrotta, P.; Raccosta, S.; Manno, M.; Accomando, S.; D’Arpa, F.; et al. Nanovesicular Mediation of the Gut–Brain Axis by Probiotics: Insights into Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Biology (Basel) 2024, 13, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterna, A.; Rao, E.; Adamo, G.; Raccosta, S.; Picciotto, S.; Romancino, D.; Noto, R.; Touzet, N.; Bongiovanni, A.; Manno, M. Isolation of Extracellular Vesicles From Microalgae: A Renewable and Scalable Bioprocess. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamo, G.; Fierli, D.; Romancino, D.P.; Picciotto, S.; Barone, M.E.; Aranyos, A.; Božič, D.; Morsbach, S.; Raccosta, S.; Stanly, C.; et al. Nanoalgosomes: Introducing Extracellular Vesicles Produced by Microalgae. J Extracell Vesicles 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimson, A.; Farh, K.K.-H.; Johnston, W.K.; Garrett-Engele, P.; Lim, L.P.; Bartel, D.P. MicroRNA Targeting Specificity in Mammals: Determinants beyond Seed Pairing. Mol Cell 2007, 27, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzato, M.; Li, M.; Vignat, J.; Laversanne, M.; Singh, D.; La Vecchia, C.; Vaccarella, S. The Epidemiological Landscape of Thyroid Cancer Worldwide: GLOBOCAN Estimates for Incidence and Mortality Rates in 2020. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2022, 10, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Chang, Q.; Lu, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, C. MiR-221-3p Facilitates Thyroid Cancer Cell Proliferation and Inhibit Apoptosis by Targeting FOXP2 Through Hedgehog Pathway. Mol Biotechnol 2022, 64, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.L.; Gao, A. Bin; Wang, Q.; Lou, X.E.; Zhao, J.; Lu, Q.J. <p>MicroRNA-221 Promotes Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Cells Migration and Invasion via Targeting RECK and Regulating Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition</P>. Onco Targets Ther 2019, 12, 2323–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.-Q.; Wang, J.-Q.; Tsai, Y.-P.; Wu, K.-J. HSP60 Overexpression Increases the Protein Levels of the P110α Subunit of Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase and c-Myc. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2015, 42, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanella, C.; D’Anneo, A.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Barone, R.; Emanuele, S.; Lo Cascio, F.; Mocciaro, E.; Fais, S.; Conway de Macario, E.; et al. The Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor SAHA Induces HSP60 Nitration and Its Extracellular Release by Exosomal Vesicles in Human Lung-Derived Carcinoma Cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 28849–28867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino Gammazza, A.; Campanella, C.; Barone, R.; Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Gorska, M.; Wozniak, M.; Carini, F.; Cappello, F.; D’Anneo, A.; Lauricella, M.; et al. Doxorubicin Anti-Tumor Mechanisms Include Hsp60 Post-Translational Modifications Leading to the Hsp60/P53 Complex Dissociation and Instauration of Replicative Senescence. Cancer Lett 2017, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comoglio, P.M.; Trusolino, L.; Boccaccio, C. Known and Novel Roles of the MET Oncogene in Cancer: A Coherent Approach to Targeted Therapy. Nature Reviews Cancer 2018 18:6 2018, 18, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, W.J.; Hu, Y.L.; Qian, C.Y.; Feng, Y.; Liu, J.Z.; Yang, J.L.; Huang, H.; Zhu, Y.Z.; Xue, W.J. HDAC4 Promotes the Growth and Metastasis of Gastric Cancer via Autophagic Degradation of MEKK3. British Journal of Cancer 2022 127:2 2022, 127, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spartalis, E.; Athanasiadis, D.I.; Chrysikos, D.; Spartalis, M.; Boutzios, G.; Schizas, D.; Garmpis, N.; Damaskos, C.; Paschou, S.A.; Ioannidis, A.; et al. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors and Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma. Anticancer Res 2019, 39, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Fu, K.; Jing, S. MicroRNA-409-3p Suppresses Cell Proliferation and Cell Cycle Progression by Targeting Cyclin D2 in Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Oncol Lett 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornari, F.; Gramantieri, L.; Ferracin, M.; Veronese, A.; Sabbioni, S.; Calin, G.A.; Grazi, G.L.; Giovannini, C.; Croce, C.M.; Bolondi, L.; et al. MiR-221 Controls CDKN1C/P57 and CDKN1B/P27 Expression in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Oncogene 2008 27:43 2008, 27, 5651–5661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Tan, H.; Huang, Y.; Guo, M.; Dong, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Z. TAGLN2 Promotes Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Invasion via the Rap1/PI3K/AKT Axis. Endocr Relat Cancer 2023, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Syeda, Z.; Langden, S.S.S.; Munkhzul, C.; Lee, M.; Song, S.J. Regulatory Mechanism of MicroRNA Expression in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Antibodies used for Western blots.

Table 1.

Antibodies used for Western blots.

| Antigen |

Type and source |

Supplier |

Dilution |

| CD81 |

Mouse monoclonal |

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX. Sc-70803 |

1:1,000 |

| Alix |

Mouse monoclonal |

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX. Sc-53538 |

1:500 |

| Calnexin |

Mouse monoclonal |

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX. Sc-46669 |

1:1,000 |

Table 2.

miRNA PCR primers used for Real-Time PCR Assays.

Table 2.

miRNA PCR primers used for Real-Time PCR Assays.

| miRNA |

Code |

Sequence |

Supplier |

Dilution |

| has-miR-16-1-3p |

YP00206012 |

MIMAT0004489: 5'CCAGUAUUAACUGUGCUGCUGA |

QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany |

1:10 |

| hsa-miR-1-3p |

YP00204344 |

MIMAT000416: 5'UGGAAUGUAAAGAAGUAUGUAU |

QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany |

1:10 |

| hsa-miR-206 |

YP00206073 |

MIMAT0000462: 5'UGGAAUGUAAGGAAGUGUGUGG |

QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany |

1:10 |

| has-miR-221-3p |

YP00204532 |

MIMAT0000278: 5'AGCUACAUUGUCUGCUGGGUUUC |

QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany |

1:10 |

Table 3.

Thyroid cancer-associated genes that are predicted targets of hsa-miR-1-3p, hsa-miR-206, and hsa-miR-221-3p miRNA.

Table 3.

Thyroid cancer-associated genes that are predicted targets of hsa-miR-1-3p, hsa-miR-206, and hsa-miR-221-3p miRNA.

| microRNAs |

Target gene |

Gene name |

Total context score1

|

| hsa-miR-1-3p |

MET |

met proto-oncogene |

-0.27 |

| |

HDAC4 |

histone deacetylase 4 |

-0.29 |

| |

CCND2 |

cyclin D2 |

-0.53 |

| |

TAGLN2 |

transgelin 2 |

-0.85 |

| |

CAAP1 |

caspase activity and apoptosis inhibitor 1 |

-0.48 |

| |

HSPD1 |

heat shock 60kDa protein 1 (chaperonin) |

-0.35 |

| hsa-miR-206 |

NOTCH3 |

notch receptor 3 |

-0,23 |

| |

VEGFA |

vascular endothelial growth factor A |

-0.20 |

| |

CCND2 |

cyclin D2 |

-0.53 |

| |

CDON |

cell adhesion associated, oncogene regulated |

-0.51 |

| |

MET |

met proto-oncogene |

-0.27 |

| |

CXCR4 |

chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 |

-0.38 |

| |

HSPD1 |

heat shock 60kDa protein 1 (chaperonin) |

-0.35 |

| hsa-miR-221-3p |

CDKN1B |

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (p27, Kip1) |

-1.05 |

| |

TIMP3 |

TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 3 |

-0.20 |

| |

RECK |

reversion-inducing-cysteine-rich protein with kazal motifs |

-0.26 |

| |

CCT5 |

chaperonin containing TCP1, subunit 5 (epsilon) |

-0.69 |

| |

TP53BP2 |

tumor protein p53 binding protein, 2 |

-0.54 |

| |

CDKN1C |

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1C (p57, Kip2) |

-0.35 |

| |

BCL2L11 |

BCL2-like 11 (apoptosis facilitator) |

-0.42 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).