Submitted:

03 April 2024

Posted:

04 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Gene Expression Data

2.2. Transcriptomic Analyses

2.3. Functional Pathways

2.3.1. Transcription

2.3.2. Translation

2.3.3. Folding, Sorting and Degradation

2.3.4. Replication and Repair

2.3.5. Chromosome

3. Results

3.1. Independence of the Three Transcriptomic Characteristics of Individual Genes

3.2. Cancer-Induced Regulation of Gene Expression Profile

3.2.1. Measures of Regulation of Expression Level

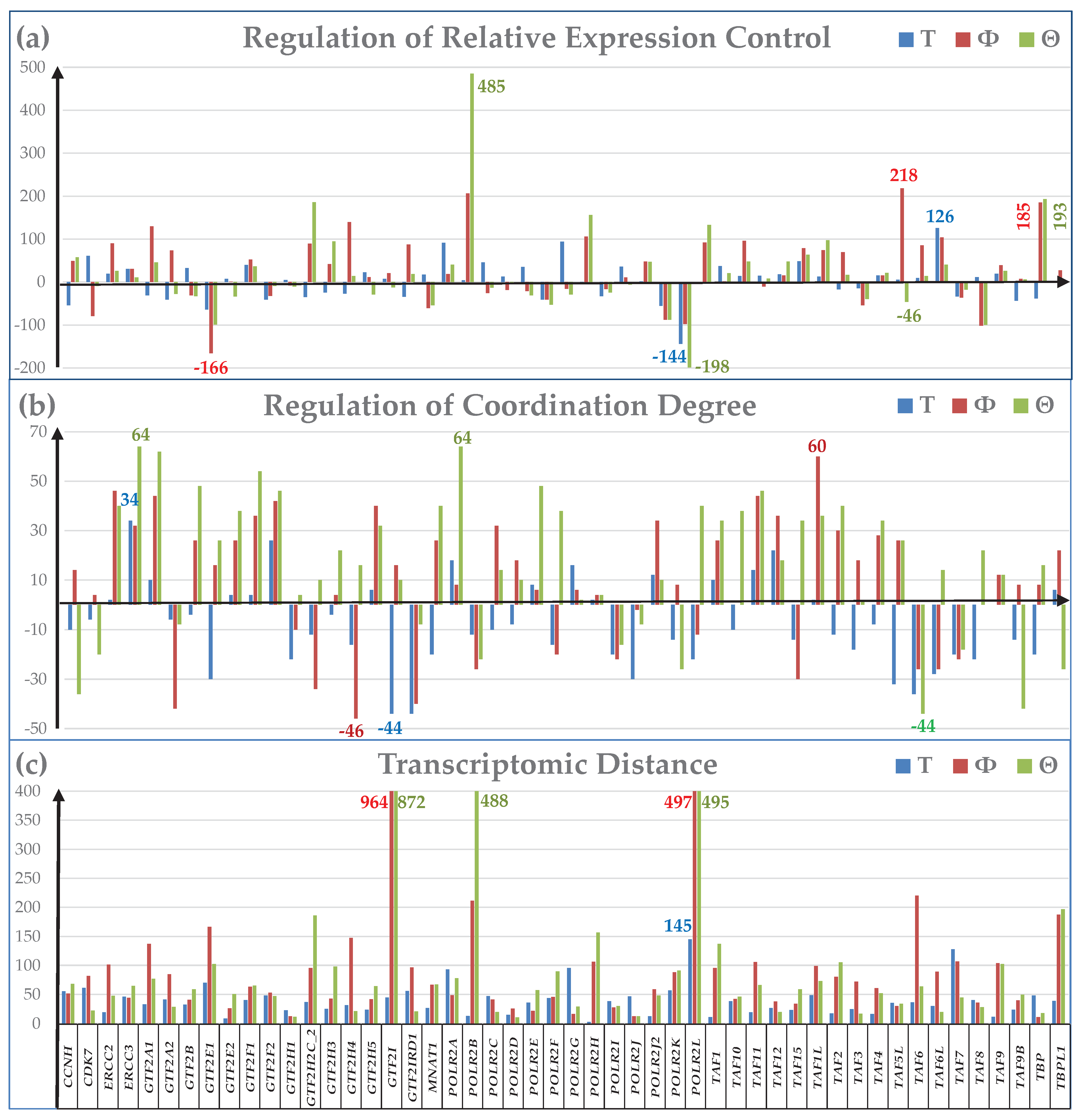

3.2.2. Regulation of the KEGG-Constructed Functional Pathways Responsible for the Genetic Information Processing in the Malignat Region of the Thyroid Tumor

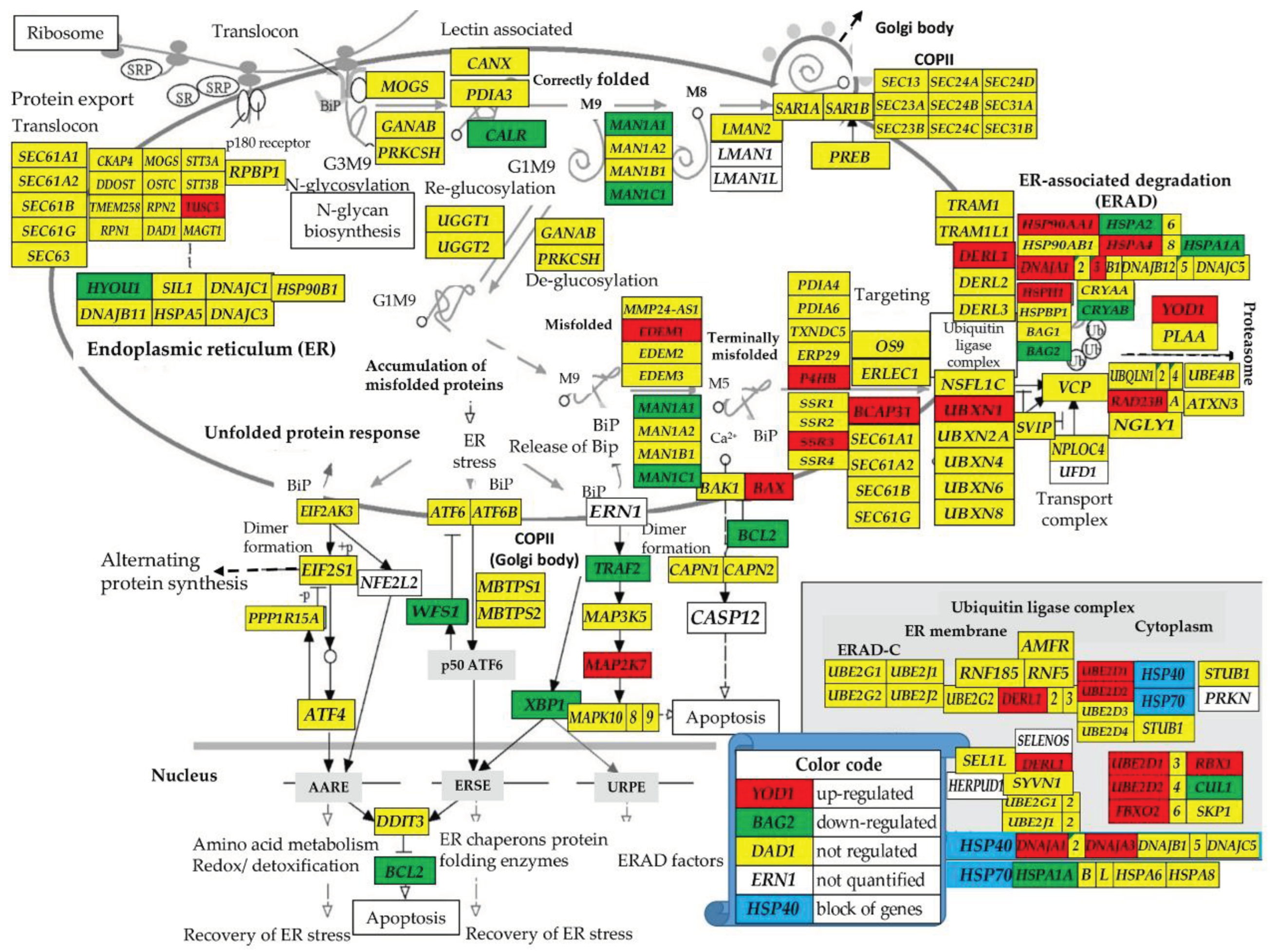

3.2.3. Regulation of the Protein Processing in Endoplasmic Reticulum pathway

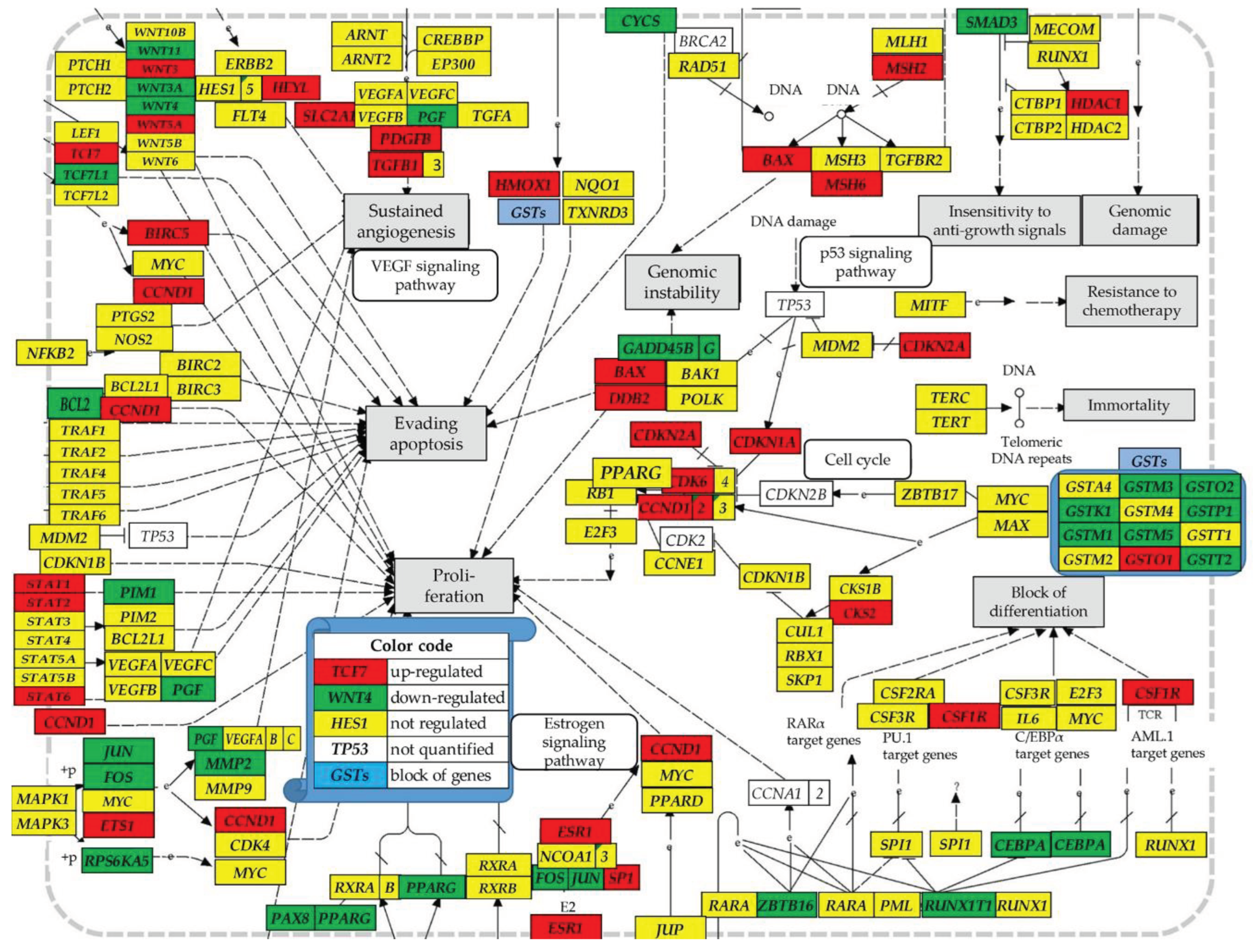

3.2.4. Regulation of the Cancer Cells’ Survival and Proliferation Genes

3.3. Additional Measures of Transcriptomic Alterations

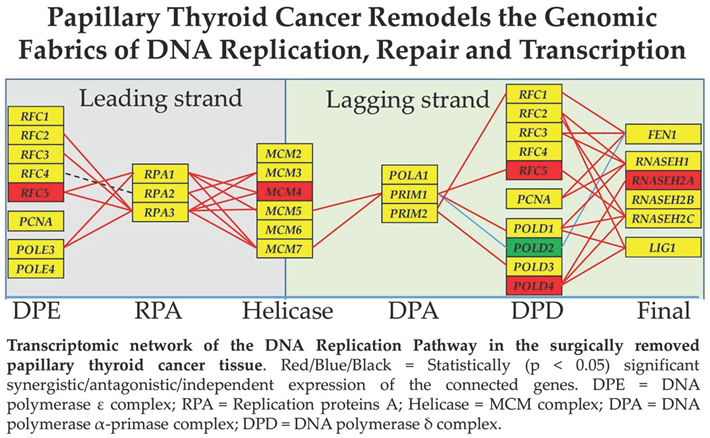

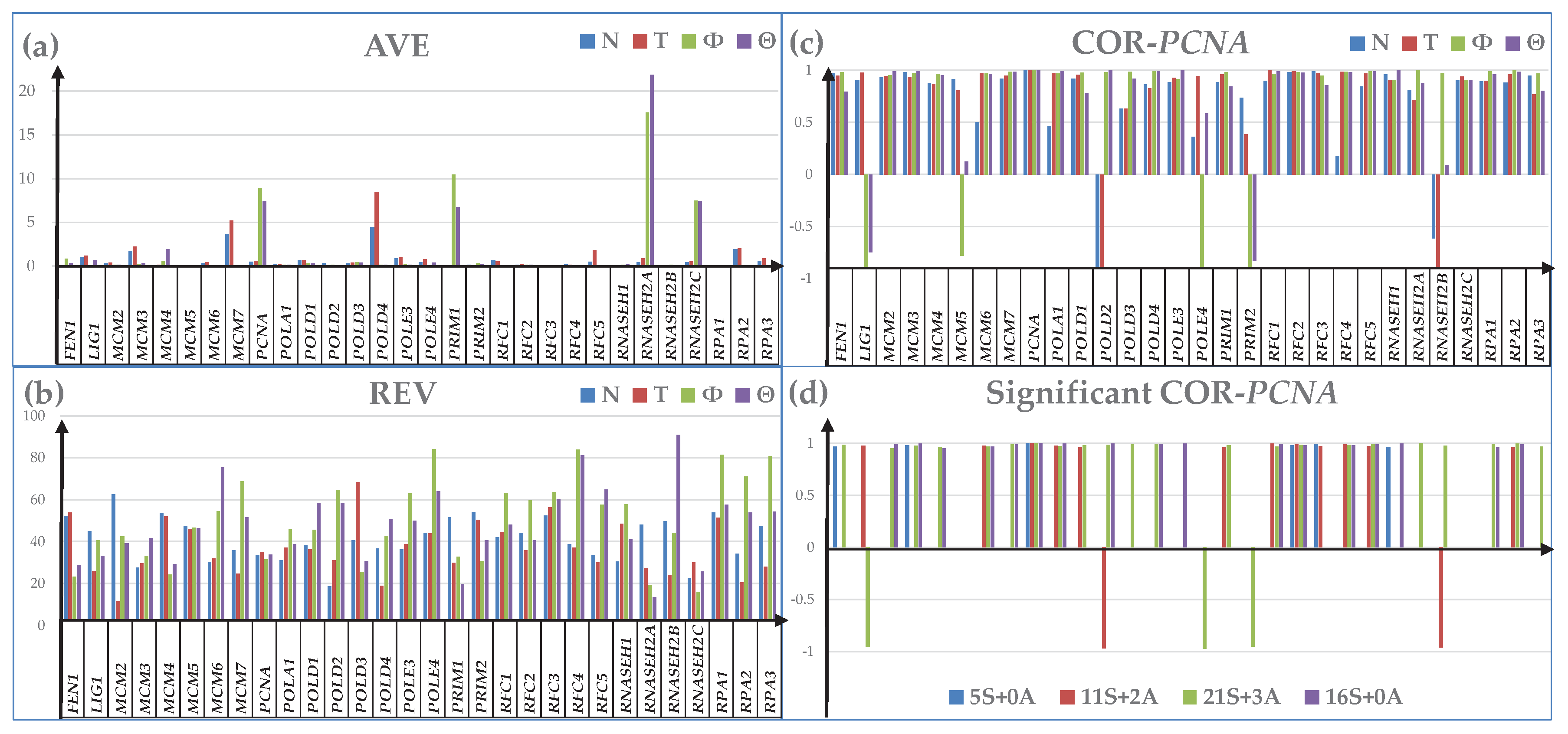

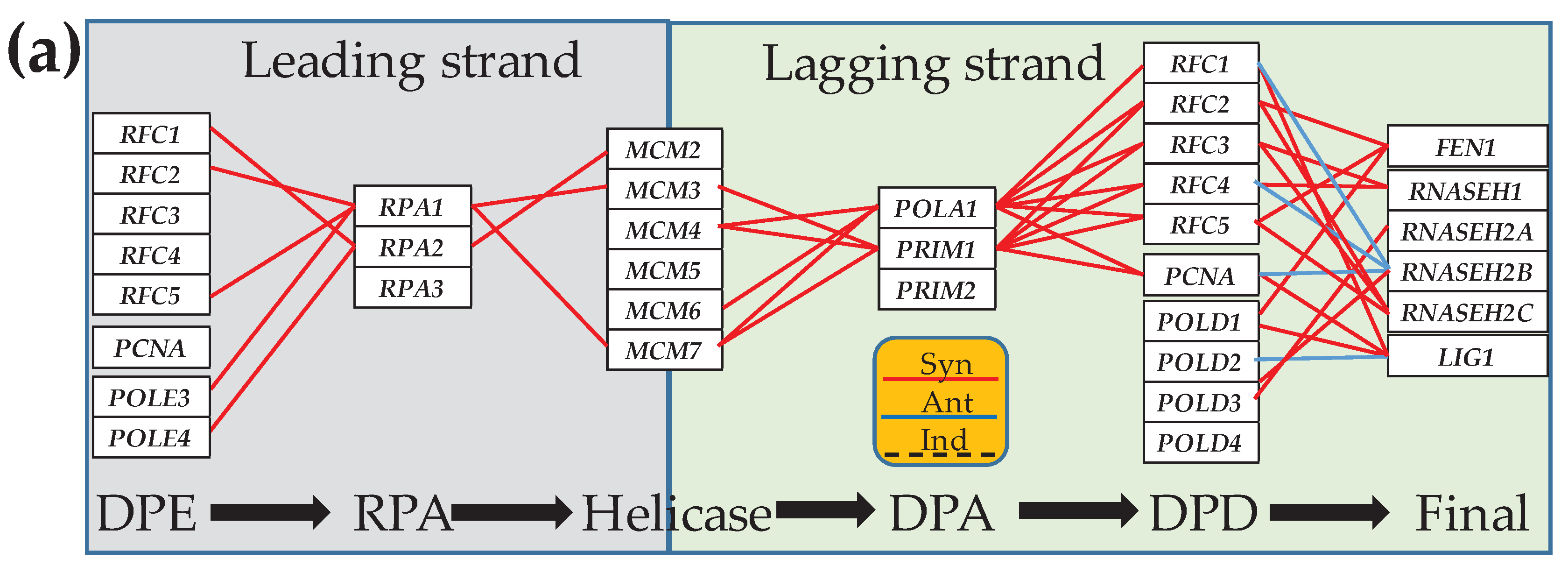

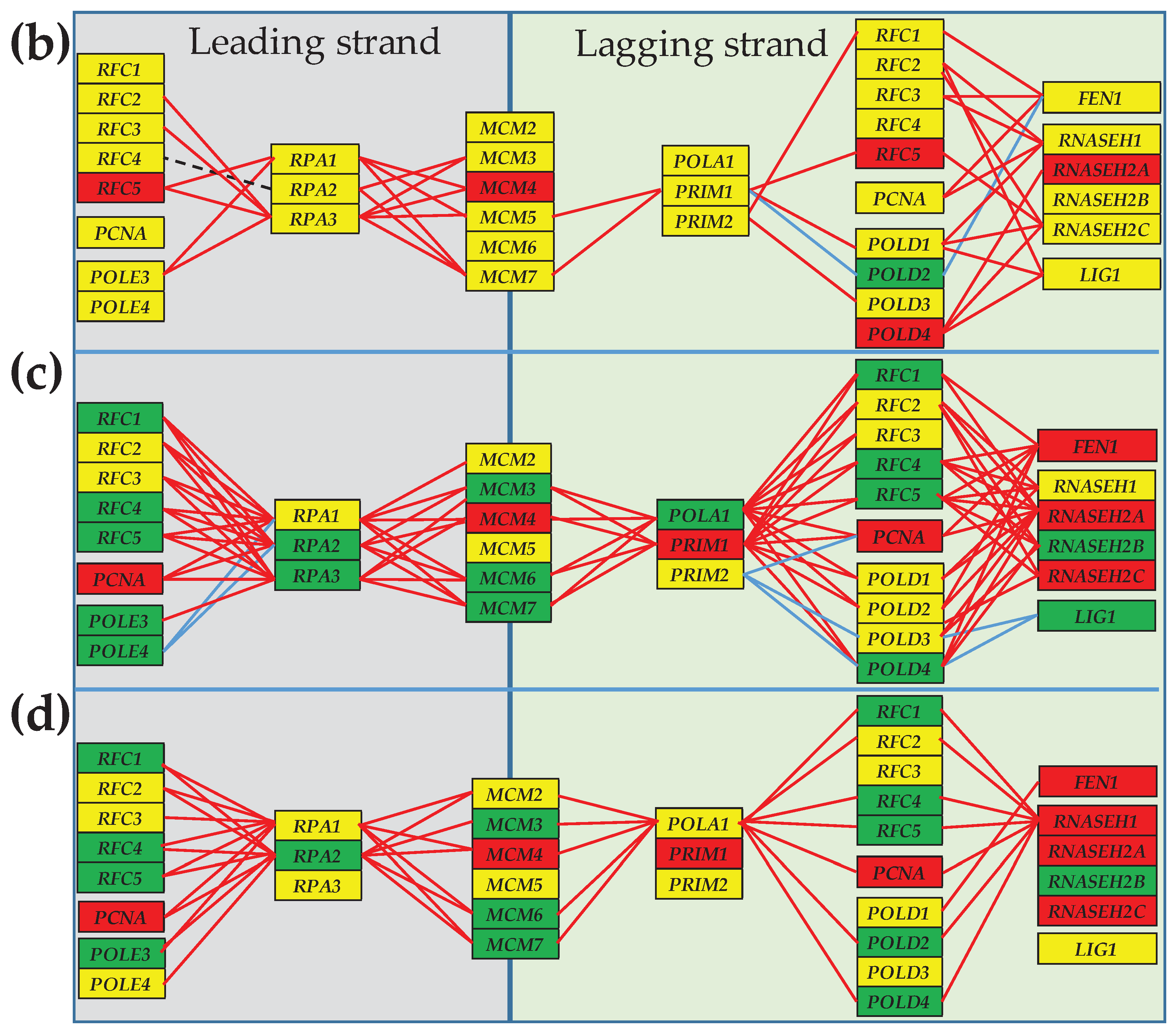

3.4. Cancer-Induced Remodeling of DNA Replication (DER) Pathway

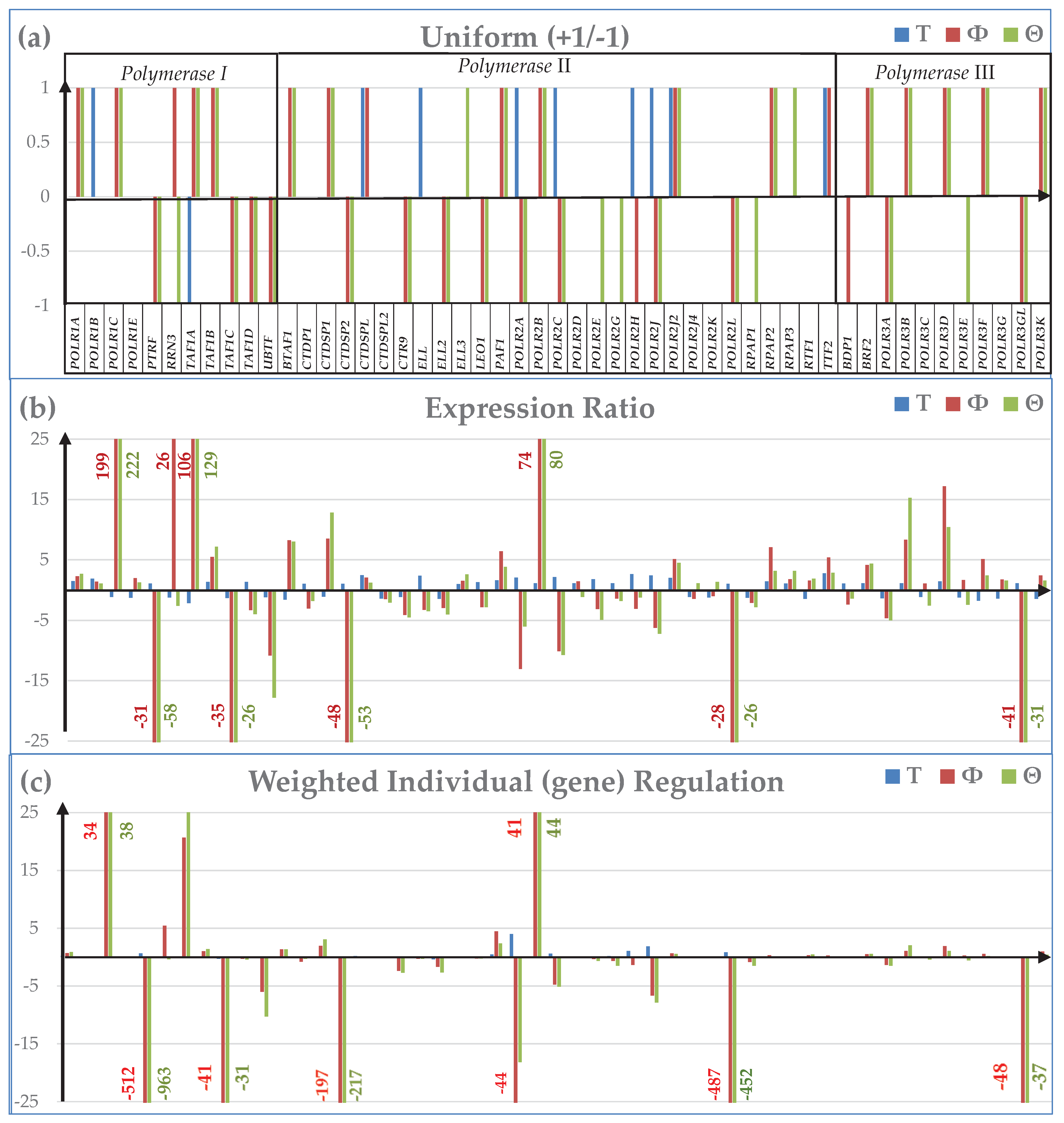

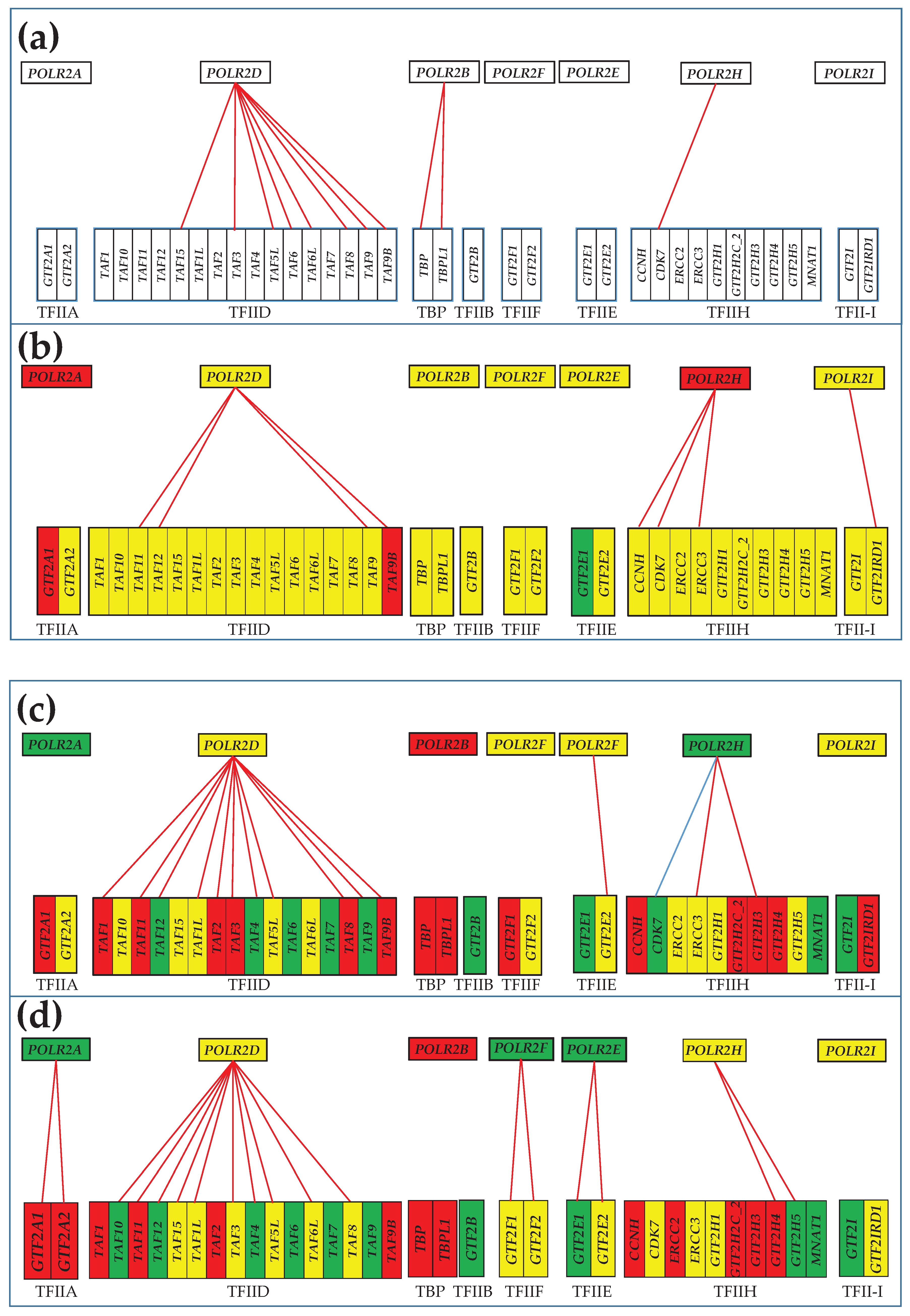

3.5. Remodeling of the Coupling of Polymerase II Genes with Basal Transcription Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Primary Transcriptomic Characteristics of Individual Genes

Appendix B. Secondary Transcriptomic Characteristics of Individual Genes

Appendix C. Criteria and Measures of Transcriptomic Alterations of Individual Genes and Functional Pathways

References

- American Cancer Society: Key Statistics for Thyroid Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/thyroid-cancer/about/key-statistics.html (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Pavlidis, E.T.; Galanis, I.N.; Pavlidis, T.E. Update on current diagnosis and management of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. World J Clin Oncol. 2023, 14, 570–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limaiem, F.; Rehman, A.; Anastasopoulou, C.; Mazzoni, T. Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. [Updated 2023 Jan 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536943/. (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Wang, Z.; Ji, X.; Zhang, H.; Sun, W. Clinical and molecular features of progressive papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. Int J Surg. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Huang, T.; Li, H. Risk factors for skip metastasis and lateral lymph node metastasis of papillary thyroid cancer. Surgery. 2019, 166, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y. MicroRNA-3653-3p inhibited papillary thyroid carcinoma progression by regulating CRIPTO-1. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2023, 69, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhuli, K.; Medori, M.C.; Donato, K.; Donato, K.; Maltese, P.E.; Tanzi, B.; Tezzele, S.; Mareso, C.; Miertus, J.; Generali, D. M. Omics sciences and precision medicine in thyroid cancer. Clin Ter. 2023, 174 (Suppl. S2), 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margraf, R.L.; Crockett, D.K.; Krautscheid, P.M.; Seamons, R.; Calderon, F.R.; Wittwer, C.T.; Mao, R. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 RET protooncogene database: Repository of MEN2-associated RET sequence variation and reference for genotype/phenotype correlations. Hum Mutat. 2009, 30, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igbokwe, A.; Lopez-Terrada, D.H. Molecular testing of solid tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011, 135, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, F.; Falchetti, A.; Franceschelli, F. ; Marini F, Tanini A, Brandi ML Thyroid cancer: Current molecular perspectives. J Oncol. 2010, 2010, 351679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máximo, V.; Melo, M.; Zhu, Y.; Gazzo, A.; Sobrinho Simões, M.; Da Cruz Paula, A.; Soares, P. Genomic profiling of primary and metastatic thyroid cancers. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2024, 31, e230144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIH National Cancer Institute GDC Data Portal. Available online: https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/ (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Li, Z.; Jia, L.I.; Zhou, H.R.; Zhang, L.U.; Zhang, M.; Lv, J.; Deng, Z.Y.; Liu, C. Development and Validation of Potential Molecular Subtypes and Signatures of Thyroid Carcinoma Based on Aging-related Gene Analysis. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2024, 21, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Hu, L.; Tan, Q.; Jia, J.; Xie, P.; Li, J.; Wang, M. Transcriptional profiles reveal histologic origin and prognosis across 33 The Cancer Genome Atlas tumor types. Transl Cancer Res. 2023, 12, 2764–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Lee, H.S.; Park, J.; Kim, K.S.; Kim, S.K.; Cho, Y.W.; Song, Y.S. Different Molecular Phenotypes of Progression in BRAF- and RAS-Like Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2023, 38, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A. Powerful quantifiers for cancer transcriptomics. World J Clin Oncol. 2020, 11, 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Tuli, N.Y.; Iacobas, S.; Rasamny, J.K.; Moscatello, A.; Geliebter, J.; Tiwari, R.K. Gene master regulators of papillary and anaplastic thyroid cancers. Oncotarget. 2017, 9, 2410–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penna, G.C.; Vaisman, F.; Vaisman, M.; Sobrinho-Simões, M.; Soares, P. Molecular Markers Involved in Tumorigenesis of Thyroid Carcinoma: Focus on Aggressive Histotypes. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2016, 150, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Han, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, R.; Liu, Z. Prognosis and therapy in thyroid cancer by gene signatures related to natural killer cells. J Gene Med. 2024, 26, e3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yin, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H. Exploration and validation of key genes associated with early lymph node metastasis in thyroid carcinoma using weighted gene co-expression network analysis and machine learning. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023, 14, 1247709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Pozo, V.A.; Cadena-Ullauri, S.; Guevara-Ramírez, P.; Paz-Cruz, E.; Tamayo-Trujillo, R.; Zambrano, A.K. Differential microRNA expression for diagnosis and prognosis of papillary thyroid cancer. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023, 10, 1139362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A. Biomarkers, Master Regulators and Genomic Fabric Remodeling in a Case of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Genes 2020, 11, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyoto Encyclopedia of genes and Genomes: KEGG Pathway database. 2. Genetic Information Processing. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html#genetic (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Ouyang, J.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Tan, L.; Zou, L. Integration of metabolomics and transcriptomics reveals metformin suppresses thyroid cancer progression via inhibiting glycolysis and restraining DNA replication. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023, 168, 115659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.S.; Branco, S.C.; Silva, S.N.; Azevedo, A.P.; Gil, O.M.; Manita, I.; Ferreira, T.C.; Limbert, E.; Rueff, J.; Gaspar, J.F. Polymorphisms in base excision repair genes and thyroid cancer risk. Oncol Rep. 2012, 28, 1859–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, L.S.; Gomes, B.C.; Gouveia, R.; Silva, S.N.; Azevedo, A.P.; Camacho, V.; Manita, I.; Gil, O.M.; Ferreira, T.C.; Limbert, E. The role of CCNH Val270Ala (rs2230641) and other nucleotide excision repair polymorphisms in individual susceptibility to well-differentiated thyroid cancer. Oncol Rep. 2013, 30, 2458–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, L.S.; Gomes, B.C.; Bastos, H.N.; Gil, O.M.; Azevedo, A.P.; Ferreira, T.C.; Limbert, E.; Silva, S.N.; Rueff, J. Thyroid Cancer: The Quest for Genetic Susceptibility Involving DNA Repair Genes. Genes 2019, 10, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Pan, Y.; Luo, Y.; Cheng, R.; Zhai, Q. Intrathyroid thymic carcinoma: A clinicopathological analysis of 22 cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2023, 67, 152221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Ying, Y.; Zeng, X.; Liu, J.; Xie, Y.; Deng, Z.; Hu, Z.; Yang, J. DNMT1/DNMT3a-mediated promoter hypermethylation and transcription activation of ICAM5 augments thyroid carcinoma progression. Funct Integr Genomics. 2024, 24, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Ma, N.; Zhang, Y.L.; Chen, X.H.; Luo, X.; Zhang, M.; Gao, Q.J.; Zhao, D.W. Transcription factor FOXP4 inversely governs tumor suppressor genes and contributes to thyroid cancer progression. Heliyon. 2024, 10, e23875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagıs, M.; Can, N.; Sut, N.; Tastekin, E.; Erdogan, E.G.; Bulbul, B.Y.; Sezer, Y.A.; Kula, O.; Demirtas, E.M.; Usta, I. A Comprehensive Approach to the Thyroid Bethesda Category III (AUS) in the Transition Zone Between 2nd Edition and 3rd Edition of The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology: Subcategorization, Nuclear Scoring, and More. Endocr Pathol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Hei, H. Advances in post-translational modifications of proteins and cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1229397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerfaoui, M.; Dokunmu, T.M.; Toraih, E.A.; Rezk, B.M.; Abd Elmageed, Z.Y.; Kandil, E. New Insights into the Link between Melanoma and Thyroid Cancer: Role of Nucleocytoplasmic Trafficking. Cells 2021, 10, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Xue, L.; Vlantis, A.C.; van Hasselt, C.A.; Chan, J.Y.K.; Fang, J.; Wang, R.; Yang, Y.; Li, D.; Zeng, X. Brusatol attenuated proliferation and invasion induced by KRAS in differentiated thyroid cancer through inhibiting Nrf2. J Endocrinol Invest. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Hao, F.; Ning, L.; Sun, C. Targeting PEAK1 sensitizes anaplastic thyroid carcinoma cells harboring BRAFV600E to Vemurafenib by Bim upregulation. Histol Histopathol. 2024, 18705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, S.; Iacobas, D.A. Personalized 3-Gene Panel for Prostate Cancer Target Therapy. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 360–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, H.; Saito, Y.; Ohuchida, K.; Kawakami, E.; Fujiki, S.; Watanabe, T.; Ono, R.; Kaneko, A.; Takagi, S.; Najima, Y. Deregulated Mucosal Immune Surveillance through Gut-Associated Regulatory T Cells and PD-1+ T Cells in Human Colorectal Cancer. J Immunol. 2018, 200, 3291–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.J.; Dhanasekaran, S.M.; Petralia, F.; Pan, J.; Song, X.; Hu, Y.; da Veiga Leprevost, F.; Reva, B.; Lih, T.M.; Chang, H.Y.; et al. Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium. Integrated Proteogenomic Characterization of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cell. 2019, 179, 964–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Gong, J.; Xu, W.; Liu, Z.; Cui, D. Next-generation sequencing identified somatic alterations that may underlie the etiology of Chinese papillary thyroid carcinoma. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2023, 32, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Xi, L. Theory and Applications of the (Cardio) Genomic Fabric Approach to Post-Ischemic and Hypoxia-Induced Heart Failure. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, S.; Ede, N.; Iacobas, D.A. The Gene Master Regulators (GMR) Approach Provides Legitimate Targets for Personalized, Time-Sensitive Cancer Gene Therapy. Genes 2019, 10, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Iacobas, S.; Lee, P.R.; Cohen, J.E.; Fields, R.D. Coordinated Activity of Transcriptional Networks Responding to the Pattern of Action Potential Firing in Neurons. Genes 2019, 10, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medscape: Thyroid Cancer Staging. Available online: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2006643-overview (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Hierarchal gene master regulators of one case of papillary thyroid cancer. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE97001 (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Hierarchal gene master regulators of papillary (BCPAP) and anaplastic (8505C) thyroid cancer cell lines. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE97002 (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Agilent-026652 Whole Human Genome Microarray 4x44K v2. Platform GPL10332. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GPL10332 (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Iacobas, D.A.; Obiomon, E.A.; Iacobas, S. Genomic Fabrics of the Excretory System’s Functional Pathways Remodeled in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 9471–9499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Mgbemena, V.E.; Iacobas, S.; Menezes, K.M.; Wang, H.; Saganti, P.B. Genomic Fabric Remodeling in Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (ccRCC): A New Paradigm and Proposal for a Personalized Gene Therapy Approach. Cancers 2020, 12, 3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RNA polymerase. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa03020 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Basal transcription factors. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa03022 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Spliceosome. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa03040 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Ribosome. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa03010 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa00970 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Nucleocytoplasmic transport. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa03013 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- mRNA surveillance pathway. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa03015 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Ribosome biogenesis in eukaryotes. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa03008 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Protein export. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa03060 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa04141 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- SNARE interactions in vesicular transport. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa04130 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Ubiquitin mediated proteolysis. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa04120 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Sulfur relay system. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa04122 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Proteasome. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa03050 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- RNA degradation. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa03018 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- DNA replication. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa03030 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Base excision repair. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa03410 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Nucleotide excision repair. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa03420 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Mismatch repair. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa03430 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Homologous recombination. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa03440 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Non-homologous end-joining. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa03450 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Fanconi anemia pathway. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa03460 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa03082 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Polycomb repressive complex. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa03083 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Pathway in cancer. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa05200 (accessed on 14 January 2024).

- Arbel, M.; Choudhary, K.; Tfilin, O.; Kupiec, M. PCNA Loaders and Unloaders—One Ring That Rules Them All. Genes 2021, 12, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, N.; Takayama, K.I.; Yamada, Y.; Kume, H.; Fujimura, T.; Inoue, S. Ribonuclease H2 Subunit A Preserves Genomic Integrity and Promotes Prostate Cancer Progression. Cancer Res Commun. 2022, 2, 870–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saiselet, M.; Floor, S.; Tarabichi, M.; Dom, G.; Hébrant, A.; van Staveren, W.C.; Maenhaut, C. Thyroid cancer cell lines: An overview. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2012, 3, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mineva, I.; Gartner, W.; Hauser, P.; Kainz, A.; Löffler, M.; Wolf, G.; Oberbauer, R.; Weissel, M.; Wagner, L. Differential expression of alphaB-crystallin and Hsp27-1 in anaplastic thyroid carcinomas because of tumor-specific alphaB-crystallin gene (CRYAB) silencing. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2005, 10, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacobas, S.; Iacobas, D.A. A Personalized Genomics Approach of the Prostate Cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, D.; Semmens, K.; McManus, E.; Chen, Q.; Meerzaman, D.; Wang, X.; Hafner, M.; Lewis, B.A.; Takahashi, H.; Devaiah, B.N. at al. The nuclear transcription factor, TAF7, is a cytoplasmic regulator of protein synthesis. Sci Adv 2021, 7, eabi5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, K.; Li, X.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, D.; Tian, L. Mechanisms of cancer cell death induction by triptolide: A comprehensive overview. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Jia, L.I.; Zhou, H.R.; Zhang, L.U.; Zhang, M.; Lv, J.; Deng, Z.Y.; Liu, C. Development and Validation of Potential Molecular Subtypes and Signatures of Thyroid Carcinoma Based on Aging-related Gene Analysis. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2024, 21, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, E.; Asnaashari, S.; Jahanban-Esfahlan, A.; Sokouti, B. The role of MAPK, notch and Wnt signaling pathways in papillary thyroid cancer: Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analyzing microarray datasets employing bioinformatics knowledge and literature. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2023, 37, 101606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, S.; Iacobas, D.A. Astrocyte proximity modulates the myelination gene fabric of oligodendrocytes. Neuron Glia Biol. 2010, 6, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Iacobas, S.; Stout, R.F.; Spray, D.C. Cellular Environment Remodels the Genomic Fabrics of Functional Pathways in Astrocytes. Genes 2020, 11, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Fan, F.; Xu, W.; Jiang, X. POLD4 Promotes Glioma Cell Proliferation and Suppressive Immune Microenvironment: A Pan-Cancer Analysis Integrated with Experimental Validation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saiselet, M.; Floor, S.; Tarabichi, M.; Dom, G.; Hébrant, A.; van Staveren, W.C.; Maenhaut, C. Thyroid cancer cell lines: An overview. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2012, 3, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlstedt, B.A.; Ganji, R.; Mukkavalli, S.; Paulo, J.A.; Gygi, S.P.; Raman, M. UBXN1 maintains ER proteostasis and represses UPR activation by modulating translation. EMBO Rep. 2024, 25, 672–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu-Baer, F.; Ludwig, T.; Baer, R. The UBXN1 protein associates with autoubiquitinated forms of the BRCA1 tumor suppressor and inhibits its enzymatic function. Mol Cell Biol. 2010, 30, 2787–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidoo, N. ER and aging-Protein folding and the ER stress response. Ageing Res Rev. 2009, 8, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.J.; Ho, J.-N.; Byun, S.-S. ARRDC4 and UBXN1: Novel Target Genes Correlated with Prostate Cancer Gleason Score. Cancers 2021, 13, 5209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cen, X.; Chen, Q.; Wang, B.; Xu, H.; Wang, X.; Ling, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qin, D. UBE2O ubiquitinates PTRF/CAVIN1 and inhibits the secretion of exosome-related PTRF/CAVIN1. Cell Commun Signal. 2022, 20, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K. A biomarker and molecular mechanism investigation for thyroid cancer. Central European Journal of Immunology. 2023, 48, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.L.; Lin, Y.T.; Chang, Y.C.; Kondapuram, S.K.; Lin, K.H.; Chen, P.C.; Kuo, C.Y.; Coumar, M.S.; Cheung, C.H.A. The SMAC mimetic GDC-0152 is a direct ABCB1-ATPase activity modulator and BIRC5 expression suppressor in cancer cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2024, 5, 116888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, P.; Drouot, G.; Witz, A.; Merlin, J.L.; Becuwe, P.; Harlé, A. Emerging Roles of DDB2 in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 5168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saiselet, M.; Floor, S.; Tarabichi, M.; Dom, G.; Hébrant, A.; van Staveren, W.C.; Maenhaut, C. Thyroid cancer cell lines: An overview. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2012, 3, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.L.; Xie, Y.; Chen, Y.L.; Zhang, Z.M.; Tao, Y.F.; Li, G.; Wu, D.; Wang, H.R.; Zhuo, R.; Pan, J.J. The RNA polymerase II subunit B (RPB2) functions as a growth regulator in human glioblastoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2023, 674, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, F.; Li, Q.; Wang, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Lu, D.; Zhou, H.; Li, S.; et al. Proteomics and molecular network analyses reveal that the interaction between the TAT-DCF1 peptide and TAF6 induces an antitumor effect in glioma cells. Mol Omics. 2020, 16, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Xu, X.; Wei, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, G.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Ren, X.; Wang, S.; Qin, C. Prognostic Role of DNA Damage Response Genes Mutations and their Association With the Sensitivity of Olaparib in Prostate Cancer Patients. Cancer Control. 2022, 29, 10732748221129451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchinomiya, K.; Tomita, M. A mathematical model for cancer risk and accumulation of mutations caused by replication errors and external factors. PLoS ONE. 2023, 18, e0286499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuwei, X.; Bingzi, D.; Zhaowei, S.; Yujie, F.; Wei, Z.; Kun, L.; Kui, L.; Jingyu, C.; Chengzhan, Z. FEN1 promotes cancer progression of cholangiocarcinoma by regulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Dig Liver Dis 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmohsen, K.; Srikantan, S.; Tominaga, K.; Kang, M.J.; Yaniv, Y.; Martindale, J.L.; Yang, X.; Park, S.S.; Becker, K.G.; Subramanian, M. Growth inhibition by miR-519 via multiple p21-inducing pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 2012, 32, 2530–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellosaurus B-CPAP (CVCL_0153). Available online: https://www.cellosaurus.org/CVCL_0153 (accessed on 11 February 2024).

- Iacobas, D.A. Advanced Molecular Solutions for Cancer Therapy—The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of the Biomarker Paradigm. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 1694–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TRANSCRIPTION | |

|---|---|

| RNA polymerase | POLR1B, POLR2A, POLR2C, POLR2H, POLR2J, POLR2J2 |

| Basal transcription factors |

GTF2A1, TAF9B, GTF2E1 |

| Splicesome |

CDC40, EFTUD2, HNRNPA1, HNRNPC, LSM5, PHF5A, RBM8A, RBMX, SNRNP70, SNRPD1, SNRPG BCAS2, HSPA1A, LSM6, PPIL1, PRPF40A, RNU2-1, RNVU1-18, SRSF6 |

| TRANSLATION | |

| Ribosome |

MRPL14, MRPL21, MRPS6, RPL14, RPL28, RPL30, RPLP1 RPL10A, RPL17, RPL18A, RPL21, RPL23, RPL26, RPL27, RPL31, RPL34, RPL35A, RPL6, RPS10, RPS12, RPS14, RPS16, RPS20, RPS25, RPS27, RPS3A, RPS5, RPS6, RPS7, RPS8 |

| Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis | IARS2, NARS2 |

| Nucleocytoplasmic transport |

KPNA6, NUP205, NXF1, NXF3, RBM8A, TNPO2 NUP153, NUP93, XPO4 |

| mRNA surveillance pathway |

NXF1, NXF3, PAPOLG, PPP2CA, PPP2R2D, PPP2R3B, RBM8A, SMG6 PELO, PPP2R2B |

| Ribosome biogenesis in eukaryotes |

DROSHA, FBLL1, HEATR1, NHP2, NXF1, NXF3, POP4, RCL1, RPP40 FBL, SNORD3B-1 |

| FOLDING, SORTING AND DEGRADATION | |

|---|---|

| Protein export | SRP9 |

| Protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum |

BAX, BCAP31, DERL1, DNAJA1, EDEM1, FBXO2, HSP90AA1, HSPH1, MAP2K7, P4HB, RAD23B, SSR3, TUSC3, UBE2D1, UBE2D2, UBXN1, YOD1 BAG2, BCL2, CALR, CRYAB, HERPUD1, HSPA1A, HYOU1, MAN1A1, MAN1C1, WFS1, XBP1 |

| SNARE interactions in vesicular transport |

STX4, VAMP1, VAMP4, VAMP8 STX11, STX1A, STX2 |

| Ubiquitin mediated proteolysis |

CBL, DDB2, FBXO2, HERC4, KEAP1, MAP3K1, MGRN1, RNF7, UBA1, UBB, UBE2A, UBE2C, UBE2D1, UBE2D2, UBE2H PPIL2 |

| Proteasome | PSMA7, PSMB1, PSMB2, PSMB3, PSMB4, PSMD14, PSMD4, PSMD6, PSME4 |

| RNA degradation |

CNOT10, ENO3, EXOSC1, EXOSC3, LSM5, PFKM LSM6 |

| REPLICATION AND REPAIR | |

| DNA replication |

MCM4, POLD4, RFC5, RNASEH2A POLD2 |

| Base excision repair |

NEIL1, PARP1, PNKP, POLD4, RFC5 POLD2, POLG2 |

| Nucleotide excision repair |

DDB2, POLD4, POLR2A, POLR2C, POLR2H, POLR2J, POLR2J2, RAD23B, RFC5, XPA POLD2 |

| Mismatch repair |

MSH2, MSH6, POLD4, RFC5 POLD2 |

| Homologous recombination |

POLD4, RAD50, XRCC3 POLD2 |

| Non-homologous end-joining | RAD50 |

| Fanconi anemia pathway |

FANCE, FANCI, POLH, RMI2 FAN1 |

| CHROMOSOME | |

| ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling |

ARID1A, BAZ1A, BAZ2A, BCL7A, BCL7B, BCL7C, HDAC1, KAT5, MEAF6, PBRM1, RSF1 S, MARCA4, SMARCD3, SMARCE1, YEATS4 CECR2 ING3 MBD2 |

| Polycomb repressive complex |

AEBP2, CBX2, CBX4, EZH1, HDAC1, PHF19, SCMH1, TEX10, UBE2D1, UBE2D2, YAF2 ASXL3, USP16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).