1. Introduction

United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is a unique and necessary opportunity to support sustainable, regenerative and inclusive growth, without which it will be impossible to tackle the climate emergency, the rampant loss of biodiversity and social inequalities and asymmetries.

Sustainable development is understood as socio-economic development that takes into account the rights of nature and dignified life for future generations [

1]. In line with this, sustainability considers a holistic integration of economic, environmental, and social components to promote development, including life quality, health, and well-being.

Looking for meaningful words to define sustainability, dos Santos et al. [

2] obtained, as most common answers of a questionnaire applied to a sample of 49 interviewed citizens, “change, knowledge, reuse, reduction, family, and health”. These authors have also conceptualized sustainability as “the proposal of a life model that guarantees the survival of ecosystems, where the human being is included and grounded in the web of life, where we can all live harmoniously within the interconnected systems of economic, social, cultural, political, and environmental relationships”.

According to the International Institute for Sustainable Development [

3] only 16% of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets are on track to be achieved by 2030, with the remaining 84% showing limited progress or its reversal. Among the 167 countries evaluated, Portugal ranks 16th, with a score of 80.28 [

4]. Most of the SDGs worked on in Portugal achieved a performance of over 50%. As pointed out by Medeiros [

5], local governments have been called upon to participate and to transform the global SDG agenda into a local reality. In Portugal, the SDG Local Platform, a municipal platform for the Sustainable Development Goals [

6], already shows several good practices developed by municipalities. The way forward is now to join forces so that other levels of government and other players in society, together with the Academy, can help transform our current social, economic, environmental, and political reality. Drawing up targets and indicators that are appropriate to each specific local reality, is an opportunity to rethink local development, understand the new dynamics, and search together for alternatives to the challenges of the coming years, collectively in each community.

The way human beings relate to nature, the environment, and consumption promotes imbalances, it is therefore important, on the one hand, to develop actions that minimize the impacts of human activity and, on the other hand, to promote greater awareness to change behavior. According to Hudson [

7] young people have an increased sense of environmental consciousness and are interested in ways to protect and save the planet. This can be explained by the existence of different programs and projects covering different levels of learning, and/or the information/awareness conveyed in the media. For example, the study carried out by Barreiros et al. [

8] regarding HEI’ Students’ Literacy in Sustainable Use of Potable Water, showed that the main sources of information identified by the students are social communication, internet/social networks, and family background. This indicates that, although some environmental awareness has increased, there is still a long way to go, and this should also be promoted at HEI level.

Since it’s clear that human action has a major influence on environmental problems, educational processes have been working on environmental and sustainability issues for a long time. The terms environmental education, education for sustainability or education for global citizenship give rise to specific concepts for working on these issues.

Environmental education is a lifelong learning process that aims to promote informed and active citizenship, ensuring the involvement and commitment of each citizen and the organizations, to a sustainable future [

9].

The Portuguese Strategy for Environmental Education [

10] provides 16 measures framed by strategic objectives, which serve three (3) central pillars of the government’s environmental policy, namely: (1) decarbonizing society (climate, energy efficiency, sustainable mobility); (2) making the economy circular (dematerialization, collaborative economy and sustainable consumption, product design and efficient use of resources, waste recovery) and (3) enhancing the territory (spatial planning, sea, and coast, water, natural values, landscape, air, and noise). However, as pointed out by Coelho et al. [

11] to achieve global social transformation, it is essential that citizens have access to an education that puts real-world experiences at the centre of learning, encourages reflection and critical thinking, and prepares people for diversity; only by developing participation and a sense of belonging to a shared humanity, which individual can move towards education for global citizenship as advocated in the national strategy for Development Education in Portugal 2018-2022 [

12]. Development Education is understood as “a lifelong learning process committed to the integral formation of people, the development of critical and ethically informed thinking, and citizen participation” [

13] (p. 3197). Development Education ultimate aim is “the formation of responsible citizens, committed to a process of social transformation in order to build more just, supportive, inclusive, sustainable and peaceful societies”[

12] (p. 16).

Education for sustainability emphasizes the need to respect human dignity and, diversity, and protect our planet’s environment and resources [

1], which, to a certain extent, systematizes the objectives of environmental education and education for global citizenship.

Klein [

14] states that transdisciplinary collaboration involving stakeholders to solve complex societal problems enables the development of new knowledge, theories, and frameworks that transcend the contributions of single or integrated disciplinary knowledge. However, Guimarães, Jacinto, Isidoro, & Pohl [

15] concluded that the transdisciplinary is not a conventional approach to problem-solving, it depends on the context and, encompasses different disciplines that work with actors outside the academy, and when there is interaction, knowledge is created. This corroborates what Udovychenko, et al. [

16] pointed out, transdisciplinary education is an education that harmoniously combines various disciplines to build new knowledge, and it forms cognitive abilities, stable knowledge and, skills in an individual. Rigolot [

17] states that being transdisciplinary, in a way, is a matter of applying transdisciplinary principles at a very personal level and for most global questions.

Schmidt, L. [

18] argues that it is essential to activate the necessary factors for an ethic of practical action, which requires: (1) public awareness - obtained through educational processes; (2) civic-environmental culture - requires the mobilization of civil society with more and better information; (3) political leadership and decision-making - requires new forms of governance with processes of openness and learning, involving different actors and testing multi-scale models. These are also essential dimensions in education for global citizenship, where the political sense of action is promoted, the ethics of care, where processes are seen as learning possibilities, and where collaborative work forms a matrix that weaves the network. However, there is a need for action and a lack of collaboration between the Portuguese higher education community to allow an advanced sustainability implementation in HEI.

So how can HEIs deal with environmental problems in a structural way? As Barros et al. [

19] point out, networks are, an important path for systemic change towards sustainability in HEI although, in Portugal, there is still no legislation to defend the importance of these networks. There is a consensus on how the promotion of environmental education and the adoption of sustainability-oriented practices are important and, also the minimization of the environmental impacts, promoted by human activities, is a priority and essential. Various programmes help with this; the Eco Schools and the Healthy Campus (HC) are two examples of such programmes. With their specific methodology, they promote the adoption of environmentally friendly practices and help methodologically in recording, monitoring, and validating these practices, which can be adopted by any HEI, since it signs up and follows their methodologies.

Eco-Schools is a program operated and coordinated at international, national, regional, and school level. This multi-level coordination allows for the convergence of common objectives, methodologies, and criteria that respect the specificity of each school concerning its students and the characteristics of the surrounding environment. The international level coordination is made by the Foundation for Environmental Education (FEE), which encourages young people to engage in their environment by allowing them the opportunity to actively protect the environment [

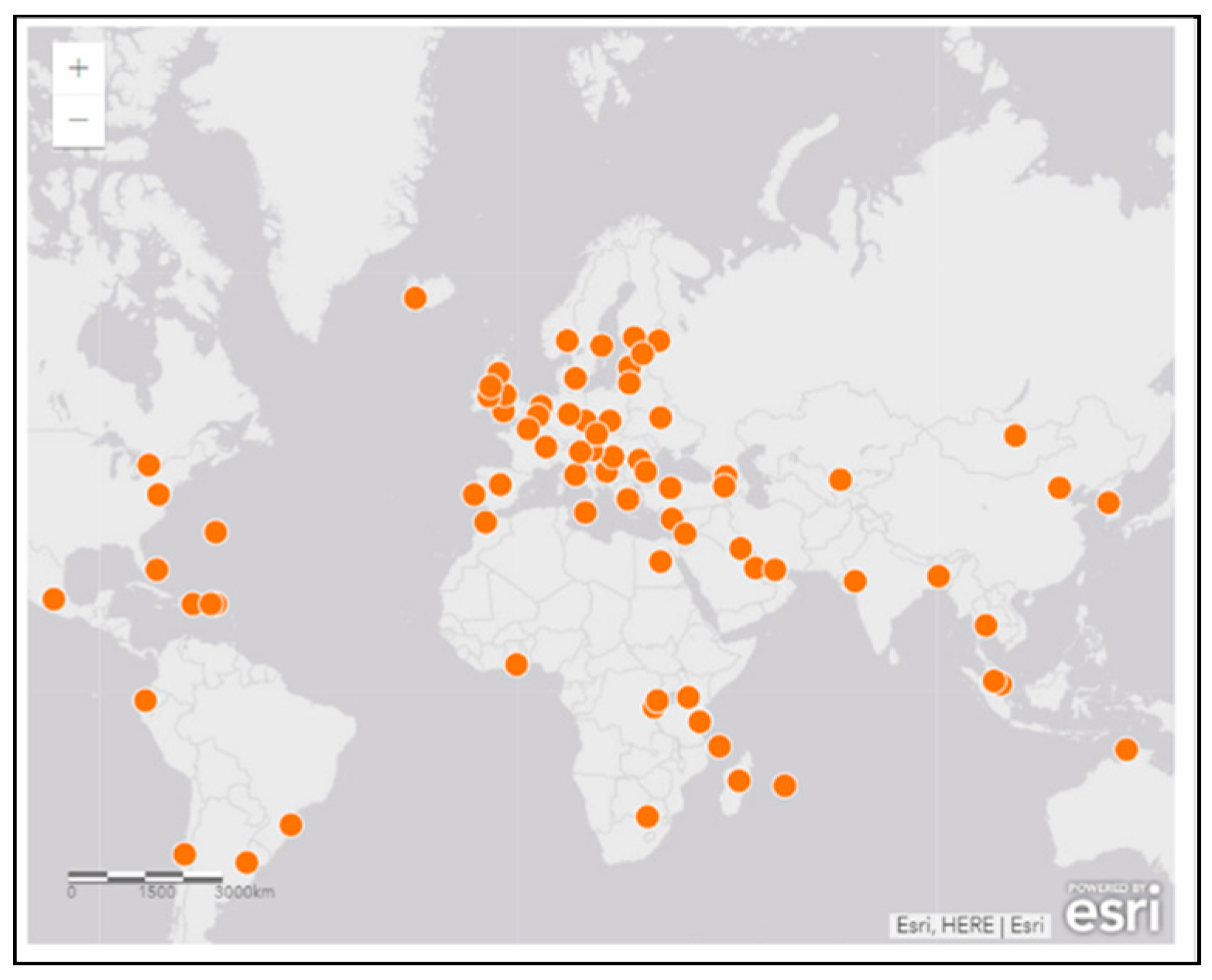

20]. This program is considered the largest Environmental Education program of different levels in the world (99 countries) (

Figure 1) [

21], and it has grown with the constant and ambitious mission to improve literacy and change environmental behaviors.

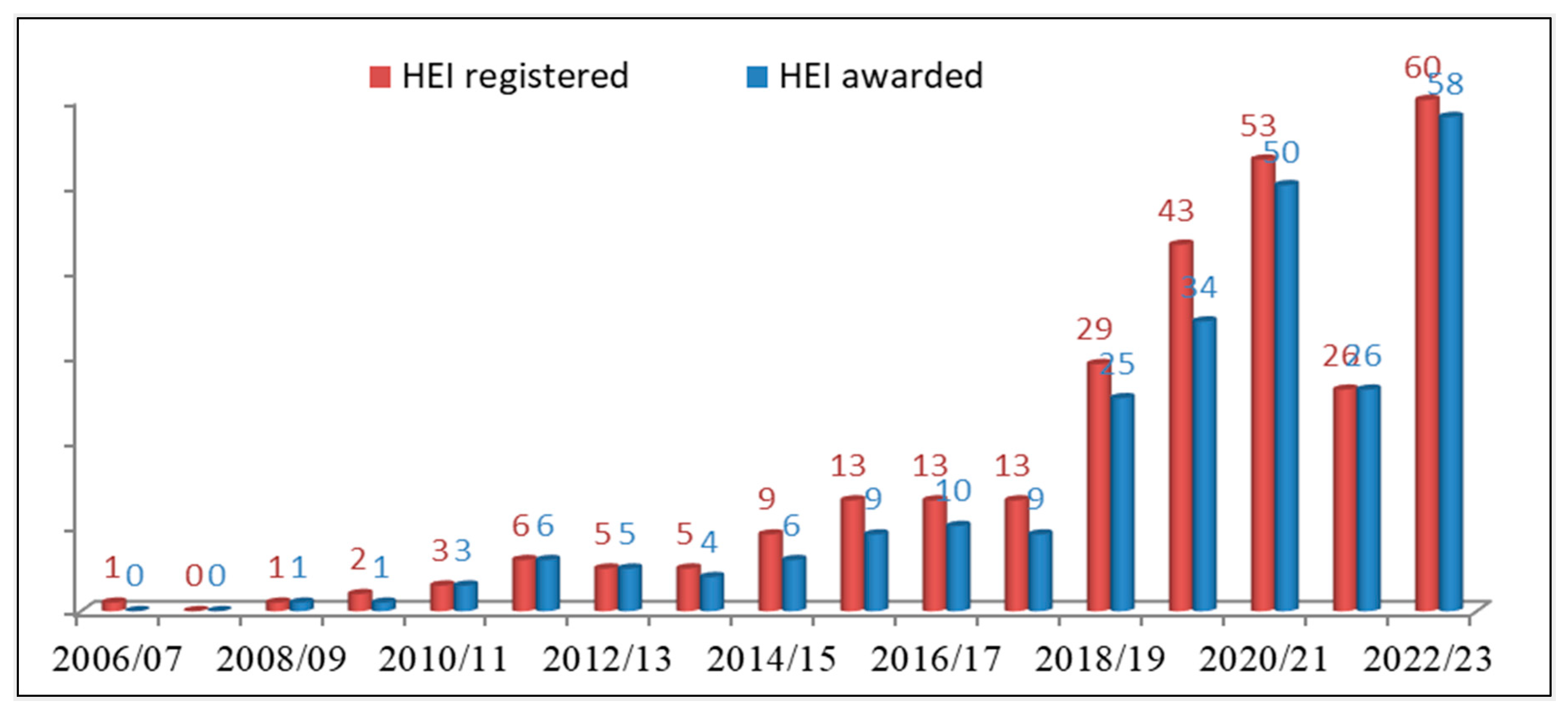

Through the Eco-school program, students, teachers, and staff experience a sense of achievement in being able to have a say in their school’s environmental management policies, ultimately leading to certification and the prestige that comes with being awarded the Green Flag. This program is developed in Portugal, since 1996 by European Blue Flag Association (Associação Bandeira Azul de Ambiente e Educação - ABAAE) which aims to encourage action and recognize the quality work carried out by the school in the field of Environmental Education for Sustainability. Despite this, HEI in Portugal only joined the program in 2006 [

22], although in recent years there has been an exponential increase in HEIs joining the program. Whereas in the post-pandemic period, the number of HEIs has dropped significantly, it is to be expected that the program’s uptake will continue to increase as shown in

Figure 2.

The four schools that belong to Polytechnic Institute of Beja (IPBeja) are nowadays Eco-Schools, although they joined the program at different times namely: School of Health (ESS) joined in 2010/11 even though, it subsequently withdrew from the program for a few years, and, renewed its membership in 2017/18; School of Agriculture (ESA) joined in 2014/15; School of Technology and Management (ESTIG) and School of Education (ESE) joined in 2015/16. To date, all the work done allowed the win of the Green Flag award for ESA nine, for ESTIG, and ESS eight, and for ESE seven [

23].

Healthy Campus (HC) is a very recent program proposed and developed by the International University Sports Federation (FISU) aimed to enhance all aspects of well-being for students and the campus community (students, teachers, and staff). This program aimed to promote health and wellness among HEI communities. The management of HC approach includes different fields, with several activities, resources, and services integrates, namely: (1) HC management; (2) physical activity and sport; (3) nutrition; (4) disease prevention; (5) mental and social health; (6) risk behaviour and (7) environment, sustainability and social responsibility [

24]. This approach is designed to support teachers, staff and mainly students in making healthy lifestyle choices, and it includes physical activities, access to nutritious food options, mental health support services, sensibilisation and awareness-raising workshops or inclusive campus environmental activities.

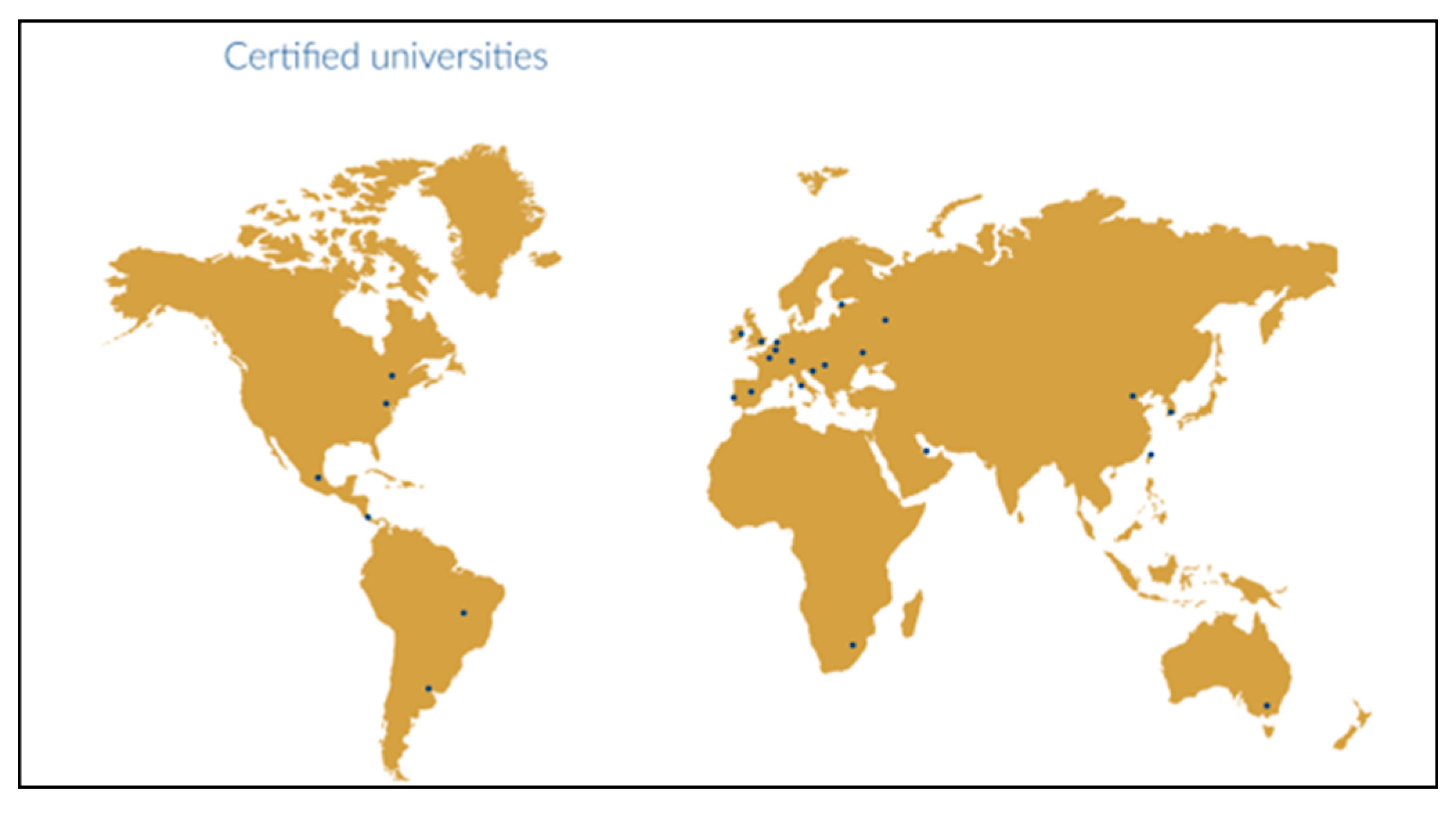

According to FISU [

25] there are 130 universities from 39 countries registered since 2020 (

Figure 3). A recent visit (June 2024) to FISU website, reveals that only 73 HEIs from 26 countries are certified in the programme. This might mean that there are registered HEIs that have not yet obtained certification.

One of the goals of the HC program is to help students prioritize their health and well-being while pursuing their academic goals. Looking to reverse the well-established trend of young adults compromising their health during their academic careers, the initiative is already having a positive impact on the lives and lifestyles of HEI students around the world [

26].

In 2021, the FISU legacy began to value other aspects besides sport. A sustainability focus area was adopted to preserve the values of HEI sport worldwide for future generations, using the United Nations 2030 Agenda and SDG [

27]. FISU as a signatory of the International Union for Conservation of Nature, commits to the following principles: (1) protecting nature and avoiding damage to natural habitats and species; (2) restoring and regenerating nature when possible; (3) understanding and reducing risks to nature in supply chains and (4) educating and inspiring positive action for nature across and beyond sport [

27].

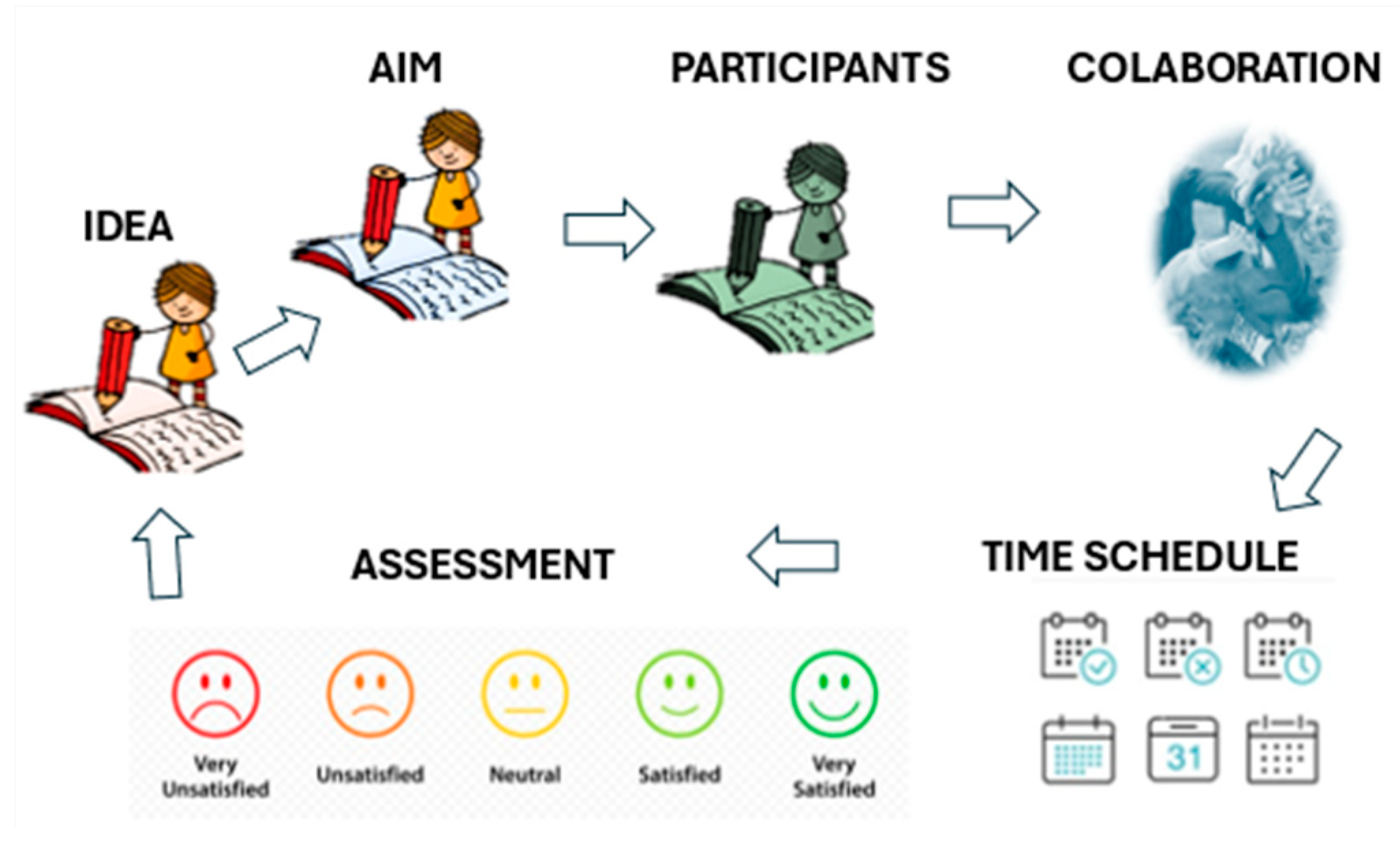

To monitor compliance with the program’s performance in HEIs, FISU uses a 100-point checklist of best practices in the concerned areas covered by the programme [

28].

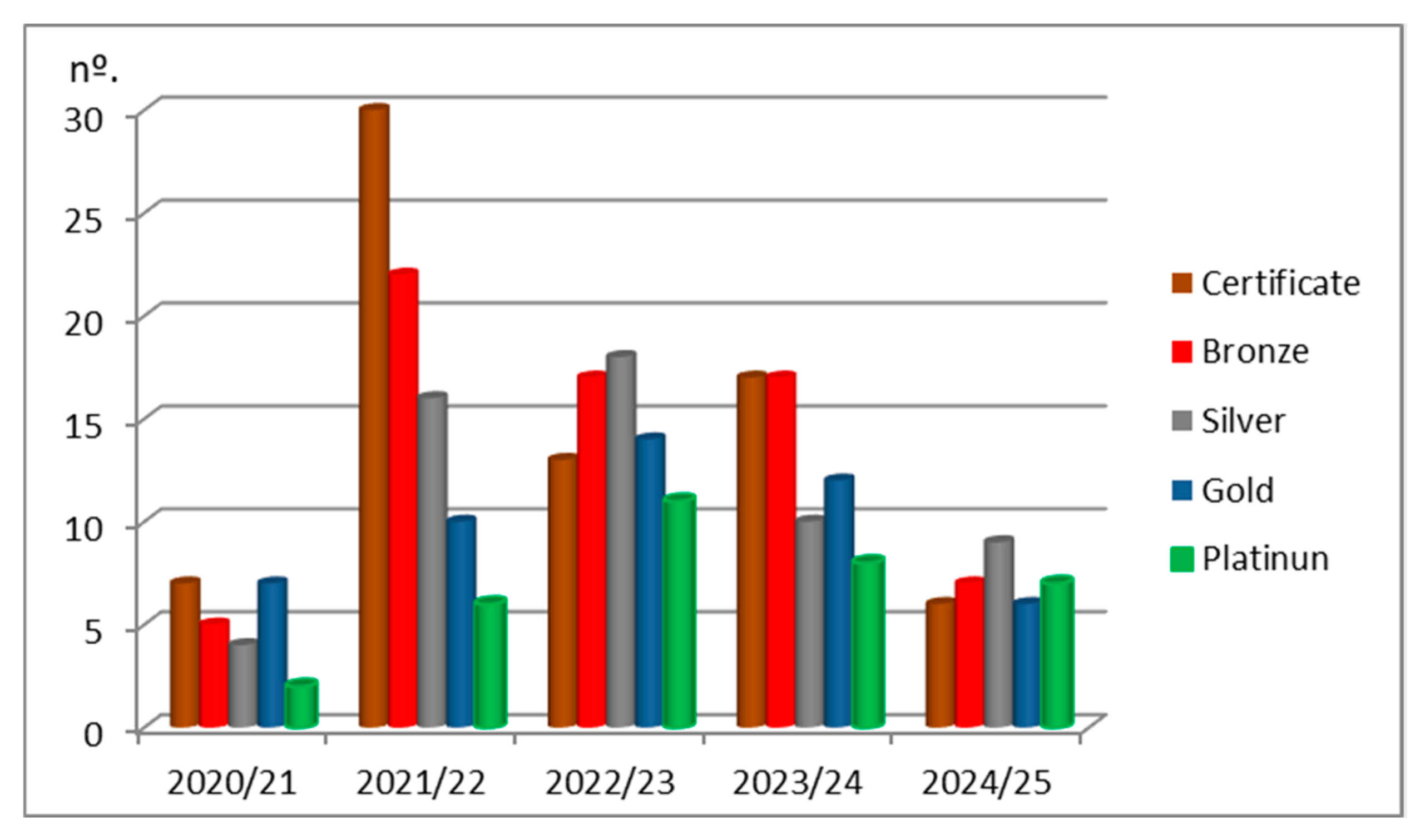

There are different categories of certification namely: certificate, bronze, silver, gold, and platinum.

Figure 4 depicts the certified HEI, in number since the program started (2020/21). It can be observed that in 2021/2022 the adherence of HEI was higher than other years. There is a linear increase for categories of: silver, gold, and platinum from 2020/21 to 2022/23. This situation may be due to the degree of demand to reach the next level.

From a total of 73 HEI certified in this program, 10 HEI are Portuguese, of which 8 are platinum, 1 is silver and 1 is gold [

29].

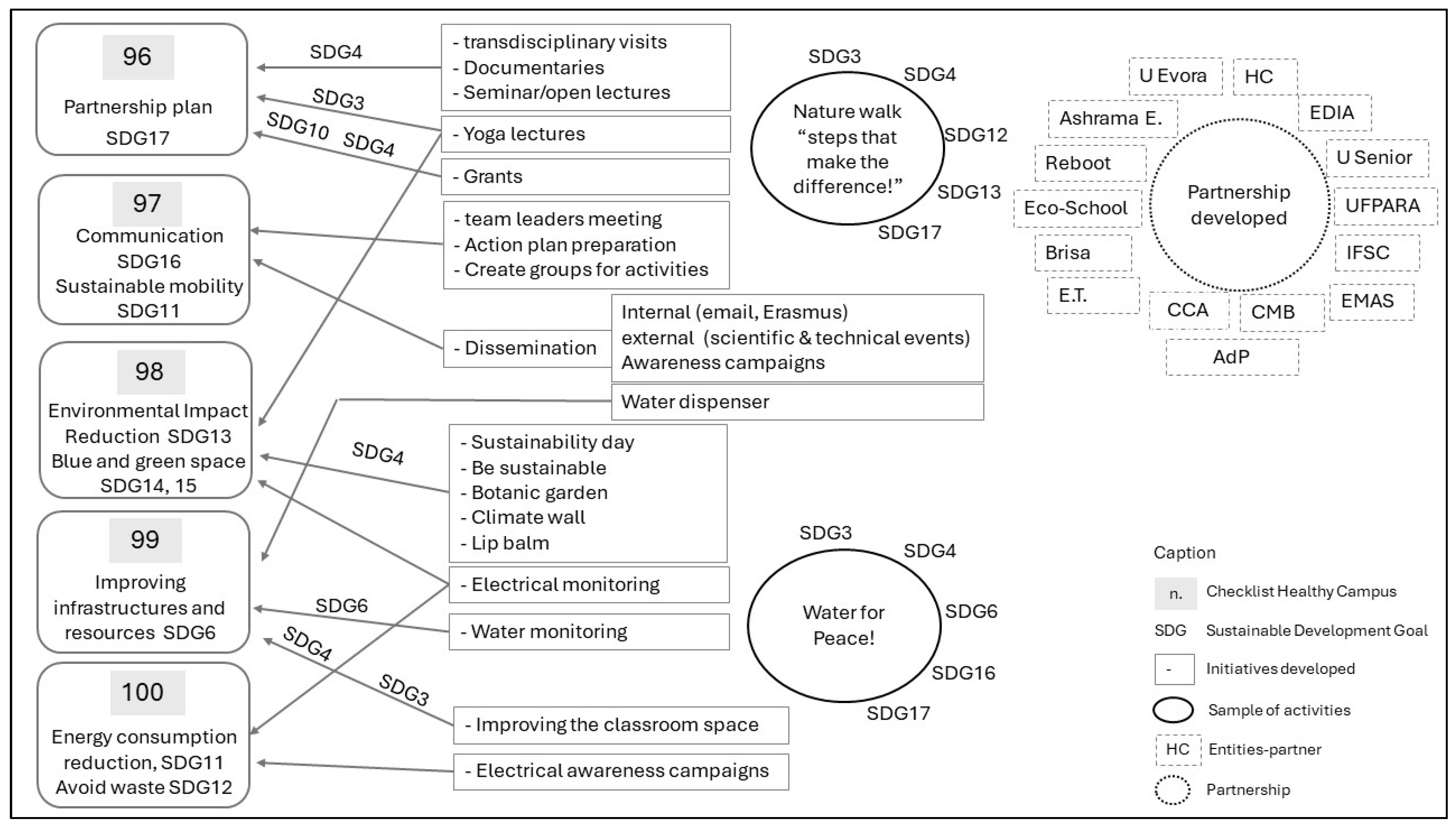

Applications to obtain the FISU certificate, at IPBeja, began in March 2022, and in June 2022, November 2023, and August 2023, the bronze, silver, gold, and platinum certificates were obtained respectively.

Both programs Eco-schools [

30] and HC [

27] work towards Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) in an organized manner and get into leading HEI rankings, regarding these programs.

But why do the HEIs adopt two programmes? What do those programs have in common or different? And how do they complement and benefit each other? Since each programme adopts a set of items to be fulfilled in specific areas, there is complementarity in the way of looking at each of those areas. While, the Eco-schools programme gives a topic to be addressed (for example for the water resource): 1) information on the importance of the topic/resource, 2) a set of problem questions, 3) key concepts and 4) ideas for activities [

31], in the Healthy Campus Programme there are no such recommendations and it moves on to monitoring: 1) the existence of partnerships that facilitate the implementation of actions; 2) the adoption of environmentally friendly practices and 3) the adoption of the “cycle of continuous improvement” environmental policy. This means, in fact, the possibility of complementing teams and environmental work which, as a result, creates synergies which means more sustainable HEIs.

5. Final Consideration

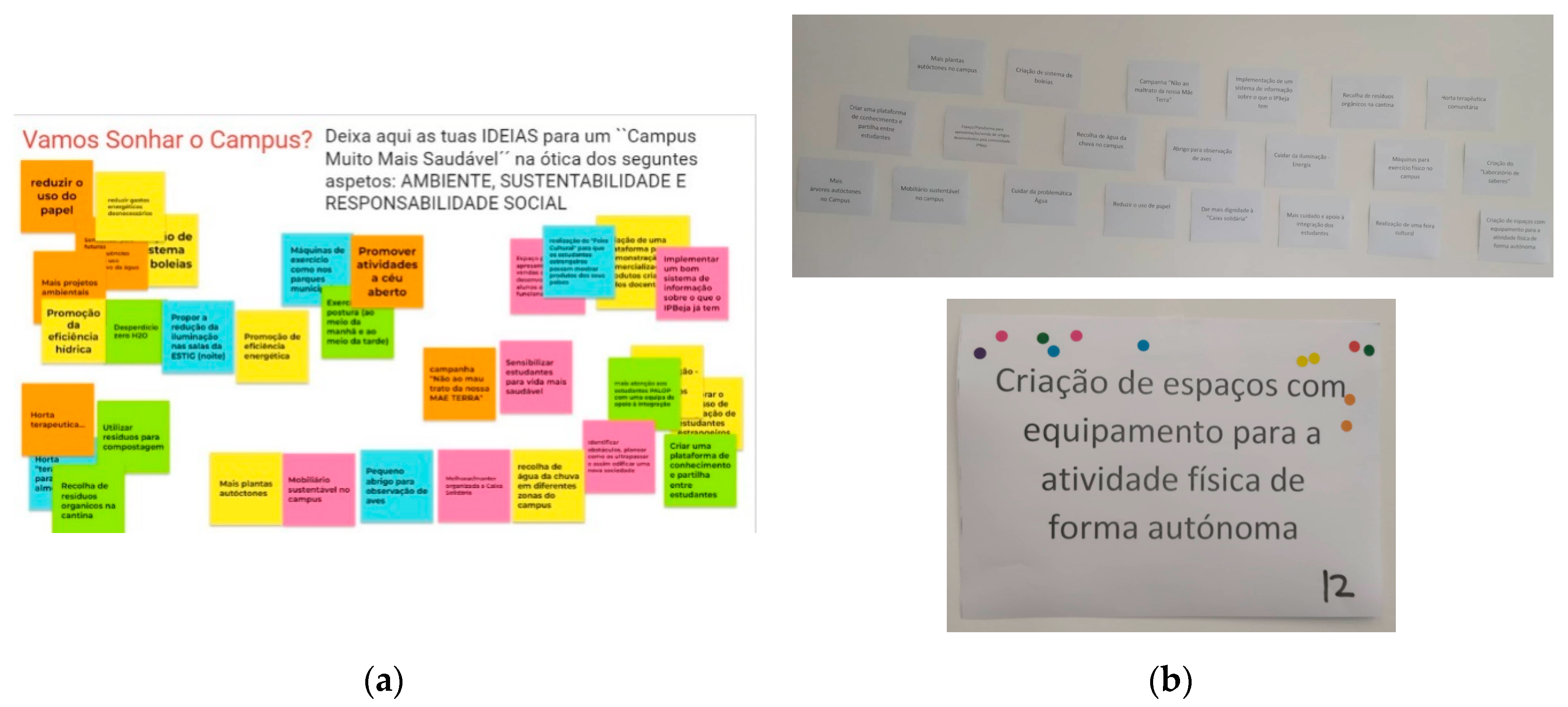

This paper exemplifies how the Academic Community can contribute to collective thinking about “what campus we want”, as well as, come up with ideas for activities to improve the environment, sustainability, social responsibility, and well-being.

The HC is a program that moves on monitoring, and prioritizing partnerships, that can facilitate the implementation of actions, as well as, the adoption of environmentally friendly practices to enhance continuously human and planet well-being.

While planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation are essential components, participant feedback and/or ideas help the ESSR group continuously improve the practical actions developed in the HC program. Despite the short time of running the HC program at IPBeja (28 months), the ESSR group, already gave a positive response to meet the six (6) items: (1) accessibility; (2) social inclusion; (3) sustainable mobility; (4) green spaces; (5) use of infrastructures and resources and (6) energy consumption, by significantly improving institutional processes and practices.

The mind map cross-referencing the items on the HC program’s checklist with the activities carried out shows that each activity can work on several SDGs. Those play an important role in citizenship as they include an action plan for the future, aligned with the 5P principles of 2030 Agenda: People (SDG1,2,3,4,5,6); Planet (SDG6,11,12,13,14); Prosperity (development and quality of life dimension - SDG7,8,9,10,11) and strengthening Peace (SDG16) and Partnerships (SDG17) [

37].

It can be concluded that when: (1) activities are designed and organized collaboratively with all members of the academic community, the inclusion and well-being of the community are enhanced; (2) academic community is called upon to participate/contribute, the activities to be developed are more targeted to their aspirations, allowing for greater involvement of people and growth of the institution in aspects of the environment, sustainability and social responsibility; HC is an asset for work and alignment between pre-defined requirements and the SDGs. In any case, some constraints weaken the effectiveness and impact of HC program, namely a lack of time allocated for the development and performance of tasks and low student motivation.

The work carried out integrating most of the SDGs, highlights SDG4, specifically target 4.7 related to the acquisition of knowledge and skills, to promote sustainable development, adoption of sustainable lifestyles, global citizenship, and appreciation of cultural diversity, improving awareness but also transforming citizens through actions.

The HC program in HEIs corroborates the idea that in addition to the curricular space, HEIs can contribute to education for sustainability, promoting the ability to transform ourselves and prosper, while respecting the limits of the planet.

For future work, intends to continue with the proposed methodology and, above all, the integration and involvement of stakeholders to contribute to the realization of activities that respond to the SDGs at a local, national, and international level and to promote a sustainable mindset, and environmentally conscious people.