1. Introduction

Sea transport vessels provide transportation of goods between countries and continents separated by seas and oceans. At the same time, depending on the type of characteristics, different vessels are used:

• General Cargo (their displacement is 30,000–40,000 tons, main power plant capacity is 10,000–12,000 kW);

• Bulk Carriers (displacement of which reaches 100,000–120,000 tons, main power plant capacity is 18,000–20,000 kW);

• Oil Product/Crude Oil/Chemical Tanker (with displacement up to 300000–350000 tons and main engine power of 18,000–20,000 kW);

• Liquefied Natural Gas Ship – LNG and Liquefied Petroleum Gas Ship – LPG (volume of cargo tanks of which reaches 250,000 m3, main engine power 30,000–35,000 kW);

• Container Ship (capable of carrying 20,000 containers equipped with a main propulsion unit of up to 80,000 kW).

The main and auxiliary engines on marine vessels are internal combustion engines / diesels [

1,

2]. This type of heat engines has the highest efficiency and the lowest specific fuel consumption [

3,

4]. Diesels are the main type of heat engines that ensure the movement of marine vessels, as well as the functioning of their systems and mechanisms [

5,

6]. Modern alternatives to marine diesel engines, such as solar panels, wind generators, rigid sails and light sails, batteries, fuel cells can meet the energy needs of marine vessels only under certain conditions and for a limited period of time.

Solar panels can only be used on ships with large open deck areas (General Cargo, Bulk Carrier, Crude Oil ore Chemical Tanker). Their installation on LNG and LPG ships is problematic (due to the complex geometry of cargo tanks), and on Container Ships is impossible. In addition, the main problem with the use of solar panels is the need to install them after cargo operations and dismantle them before cargo operations [

7,

8].

Wind generators require additional space for installation. They cannot be placed on cargo hold covers or on open superstructure decks. In the first case it is technically impossible (due to periodic opening/closing of the cargo hold covers), in the second case it increases vibration loads on the ship's living quarters. The only place for installation of wind generators is the tank and stern of the vessel, but this complicates mooring operations [

9,

10].

Rigid sails increase aerodynamic drag in the case of headwinds or side winds. Skite sails lose their effectiveness if the hydro-meteorological conditions deteriorate, and in some cases (in high wind and rain) skite sail handling becomes impossible and dismantling becomes difficult and dangerous for the crew that performs it [

11,

12].

Batteries require constant restoration of their capacity, so they are effectively used only in cases of coastal navigation of ships [

13,

14].

The power of fuel cells meets the energy needs of small displacement ships only [

15,

16]. In addition, fuel cells (in comparison with diesel engines) are characterised by a longer start-up time, as well as the time of transition from minimum load to maximum load [

17,

18].

2. Literature Review

The functioning of marine diesel engines is impossible without the use of liquid fuel of petroleum origin, which is the main source of energy for all heat engines. In accordance with the international fuel standard DIS DP-8217, developed by the international standardisation organisation ISO, two grades of distillate fuel are used in marine diesel engines – pure diesel fuel DMA, DMB and mixed fuel DMC, as well as purified fuel RM [

19,

20]. The viscosity range of DMA, DMB, DMC fuels at 50°C is within 2–15 sSt, and their density at 15°C is 880–920 kg/m

3. Considering mentioned above, these fuels are called light fuels. Calorific value of DMA, DMB, DMC fuels is within 42–44 MJ/kg.

RM class fuels (for example. RMA30, RME180, RMG380, RMK700) have 30–700 sSt viscosity at 50°C, 960–1,010 kg/m

3 density at 15°C and are called heavy fuels. Calorific value of RM class fuels is in the range of 39–42 MJ/kg. Heavy grades have a lower cost compared to light grades, which determines their use in marine diesel engines to reduce the financial costs of fuel purchase [

21,

22,

23]. It should also be noted that for modern marine diesel engines (both main and auxiliary) heavy grades of fuels are used to ensure all modes of operation, including starting and reversing modes [

24,

25,

26].

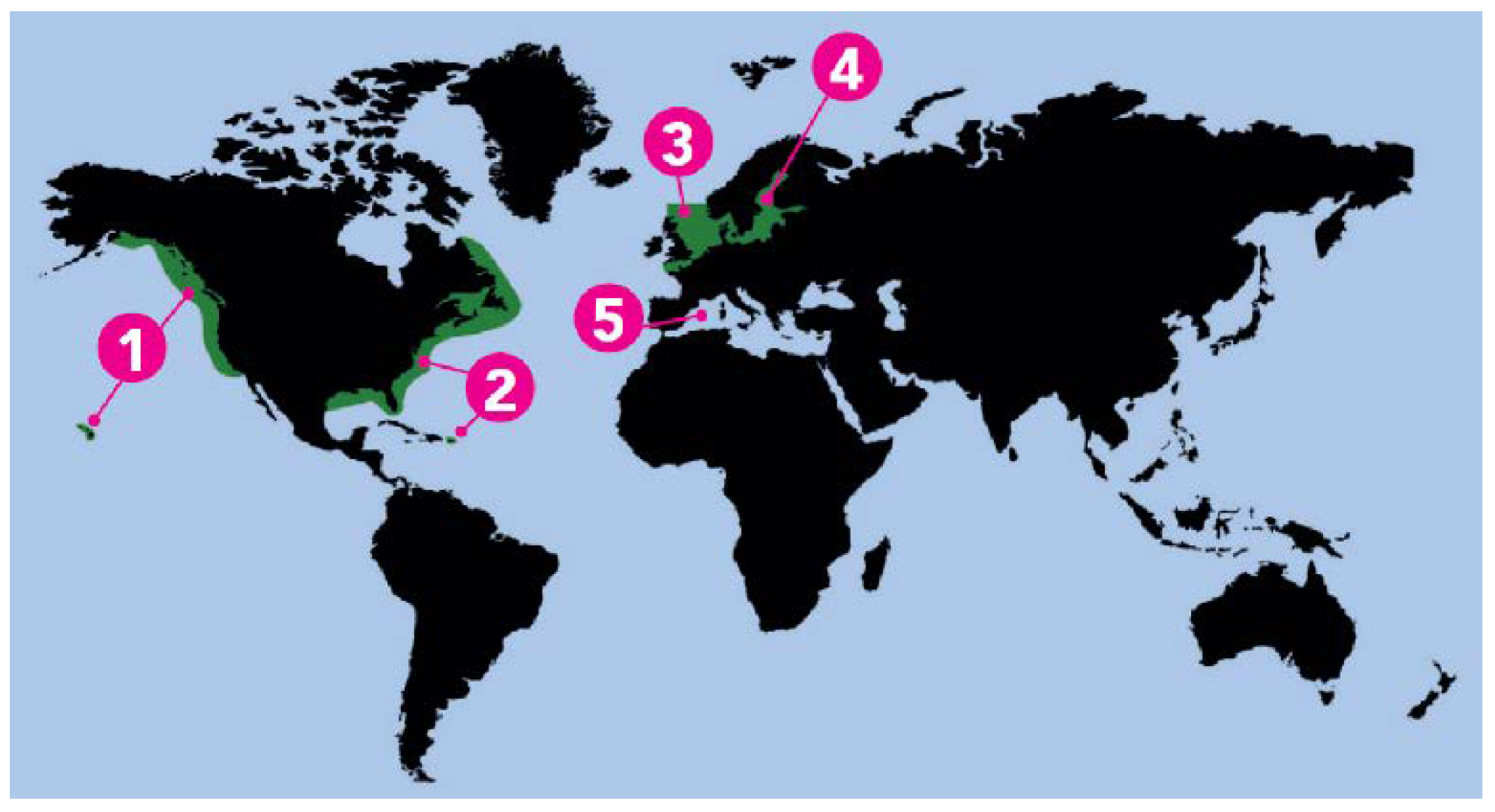

One of the criteria for the use of petroleum fuels in marine power plants is the sulphur content [

27,

28,

29]. According to the requirements of Annex VI MARPOL the sulphur content in fuel in case of operation of diesel engines in special environmental Sulphur emission control areas (SECAs) should not exceed 0.1 % by mass; in case of operation outside SECAs – the sulphur content in fuel should not exceed 0.5 % by mass (

Figure 1). The use of fuel with sulphur content exceeding 0.5 % by mass is possible only in case of additional purification of exhaust gases in special purification systems (usually in scrubbers) [

30,

31,

32]. The main task, which is achieved by using fuel with low sulphur content or scrubbers, is to reduce the emission of sulphur oxides SO

X with exhaust gases [

33,

34,

35].

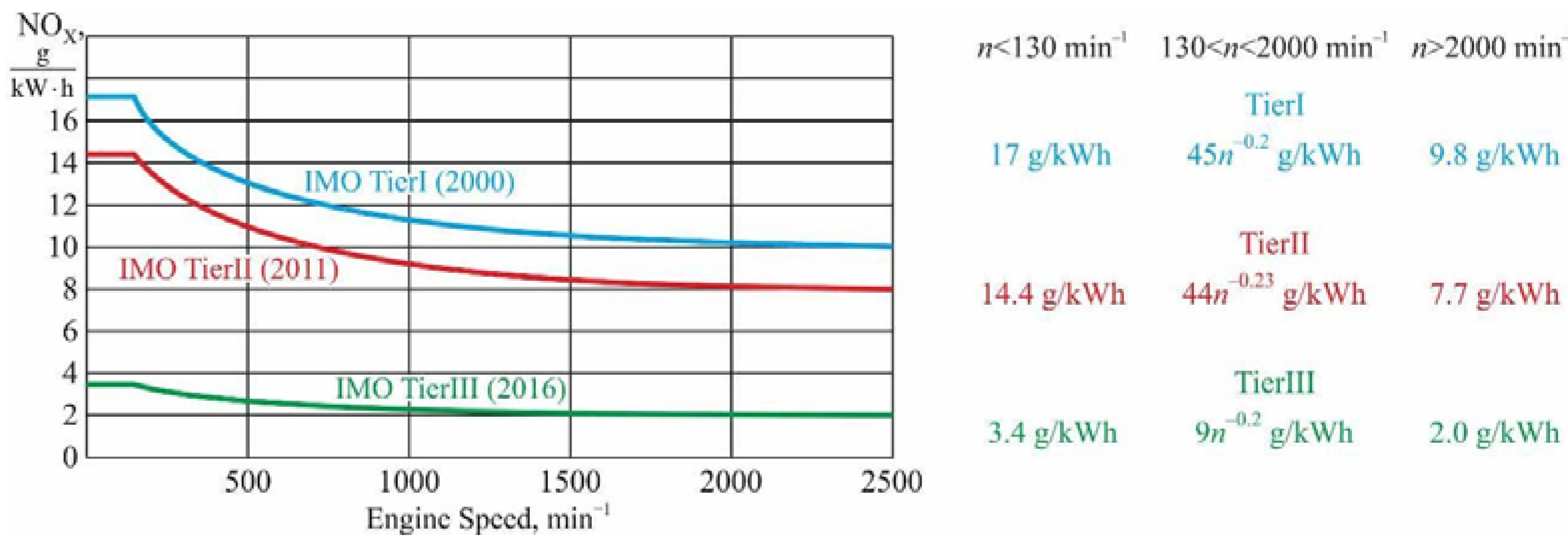

Another component of marine diesel exhaust gases, the value of which is regulated by Annex VI MARPOL, is the emission of nitrogen oxides NO

X with exhaust gases [

36,

37,

38]. In accordance with the requirements of Annex VI MARPOL, three levels of nitrogen oxide emissions are established, which depend on the year of construction of the ship and diesel engine speed (

Figure 2).

The sources of NO

X are airborne nitrogen and fuelborne nitrogen. During combustion of the fuel-air mass, thermal NO

Х and fast NO

Х are formed from the nitrogen in the air; fuel NO

Х is formed from the nitrogen in the fuel. At temperatures above 1500° C (which is only possible in the diesel cylinder), a chain reaction of nitrogen oxides formation occurs. Therefore, all methods and technologies that ensure the reduction of NO

X emissions are aimed at reducing the maximum temperature in the diesel cylinder [

39,

40,

41].

One of the options to reduce SO

X and NO

Х emissions with exhaust gases of marine diesel engines is the use of alternative fuels, the main types of which are liquefied natural gas, liquefied petroleum gas, hydrogen, ammonia, vegetable oils, biofuels [

42,

43,

44].

Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) is the most common of all alternative fuels used in stationary power generation. The advantage of LNG is its high calorific value, which can reach 55–48 MJ/kg. In addition, LNG does not contain nitrogen, this makes the formation of fuel NO

Х impossible and reduces the overall emission of nitrogen oxides. However, LNG requires regasification for combustion, which requires additional volumes of consumption tanks. The density of LNG in liquid after regasification at 20° C is 0.67 kg/m³ [

45,

46]. Therefore, it requires the use of a separate fuel system to feed it into the diesel cylinder. In addition, LNG is characterised by a higher autoignition temperature compared to petroleum fuel. Its value can reach 700–750° C – as a result of the compression process of the fuel-air mixture this value can be achieved not in all operating modes of the diesel engine. In this connection, LNG is used in marine diesel engines as an additional fuel to liquid fuel of oil origin [

47,

48]. As a rule, LNG is used on ships by which it is transported as cargo. In this case, diesels operate both on the gas-diesel cycle (in case of using a mixture of LNG and liquid petroleum fuel) and on the diesel cycle (in case of ballast passages and absence of LNG on the ship).

Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) is a mixture of light hydrocarbons liquefied under pressure. The calorific value of LPG is 47–49 MJ/kg, the density of the gas phase at 20° C is 1.87–2.52 kg/m³. As well as with LNG, when using LPG, a separate fuel system is required to supply the gas to the diesel cylinder. The auto-ignition temperature of LPG is 500–550° C, which allows its use as a separate fuel. However, as with LNG use cases, LPG-only diesel operation is only possible when the ship is in cargo transition (when carrying LPG). In the case of a ballast crossing of the vessel, the diesel is operated on petroleum origin fuel. A common disadvantage of using both LNG and LPG is the tendency of these fuels to condense when the pressure and temperature in the fuel system change. This increases the hydraulic resistance in the LNG / LPG supply system, which leads to a decrease in the amount of gas entering the diesel cylinder for combustion [

49,

50].

Nowadays hydrogen as a fuel is used practically in all types of transport, as well as in stationary power engineering. When hydrogen burns, only water vapour is produced, so hydrogen is the most environmentally friendly fuel. The calorific value of hydrogen is 120–140 MJ/kg, which is significantly higher than that of all other fuels. However, at combustion of hydrogen, mechanical loads of cylinder group and crank mechanism parts sharply increase. Hydrogen, reacting with lubricating oil, increases its oxidation rate. In addition, hydrogen is explosive. Hydrogen must be stored in special cylinders under high pressure and supplied to the cylinder at a certain temperature. There are also difficulties with hydrogen bunkering in seaports. There are fuel cells that generate hydrogen, the energy of which is further converted into electrical or mechanical energy. However, the power of such fuel cells can only provide the energy consumption of small displacement ships [

51,

52]. All these limit the usage of hydrogen as a fuel on marine ships.

One of the promising alternative fuels is ammonia. Its main advantage is the absence of carbon emissions during combustion. The calorific value of ammonia is 18–19 MJ/kg, which reduces the efficiency of its use as a separate fuel. It is most expedient to use ammonia in a mixture with fuel of oil origin on gas carriers that transport ammonia as a cargo [

53,

54]. The disadvantage of ammonia is its toxicity and explosion hazard.

Mixtures of methyl and ethyl alcohols with diesel fuel – methanol and ethanol – can be used as an alternative fuel for marine diesel engines. Methanol and ethanol combustion occurs with less (compared to diesel fuel) emission of toxic components – carbon oxides and nitrogen oxides into the atmosphere [

55,

56,

57]. At the same time in pure form (without mixture with diesel fuel) methanol and ethanol are poisonous substances. Flash point of methanol and ethanol is in the range of 8–12° C, therefore they belong to the class of hazardous liquids. The density of methanol and ethanol is 800–820 kg/m

3 at 20° C. This allows their usage without re-completion of marine fuel systems. The calorific value of methanol is 22–23 MJ/kg – which leads to increased time of methanol injection into the diesel cylinder and also makes it difficult to start the diesel engine. Methanol can be used both in diesel engines to produce mechanical energy and in special fuel cells to produce electrical energy [

58,

59].

Vegetable oils as motor fuels can be used either pure or blended with diesel fuel, as well as with gas condensates, alcohols, esters and other alternative fuels [

60,

61].

Vegetable oils come from oilseeds that contain vegetable fats. The most common vegetable oil used in internal combustion engines is rapeseed oil. The density of rapeseed oil at 20° C is between 900–920 kg/m

3. This makes it possible to use fuel equipment for transporting rapeseed oil through the fuel system, as well as for its injection into the diesel cylinder, which is used for transporting and injecting diesel fuel. The sulphur content in rapeseed oil does not exceed 0.02 % by mass – this makes it possible to use rapeseed oil in special ecological areas SECAs. The calorific value of rapeseed oil is 37–37.5 MJ/kg – this reduces the torque on the diesel shaft and limits the use of rapeseed oil in high power diesel engines [

62,

63].

One of the alternative fuels is biodiesel – biofuels [

64,

65]. The main components used in the production of biodiesel are vegetable and animal fats, the chemical composition of which slightly differs from each other [

66,

67]. As a result of esterification in the presence of methanol or ethanol and a catalyst (in the form of NaOH, KOH, NaOCH

3 or KOCH

3) these substances react to form monoalkyl esters, it is the product that is called biodiesel. The biodiesel phase is further purified by distillation and membrane fission [

68,

69].

Biodiesel (or FAME – Fatty Acid Methyl Ester), unlike petroleum-based diesel fuel, is produced from renewable organic sources. The main performance characteristics of FAME (density, viscosity, flash point, calorific value) coincide with similar indicators of diesel fuel - this allows its use in the majority of modern diesel engines [

70,

71,

72]. As a rule, FAME biodiesel is not used in pure form. The most expedient variant of its use is fuel blends with fuels of petroleum origin. In such blends, petroleum fuel is the main component and its amount is 70–95 % by mass. Biodiesel is used as an additive and its quantity is 5–30 % by mass. Such fuels are classified as B5, B10 ... B25, B30.

Biodiesel fuel is used in both main and auxiliary engines of various capacities. However, the majority of scientific studies, which are aimed at studying the possibility of using biodiesel fuel, are mainly devoted to road and railway transport [

73,

74,

75]. In addition, the criteria by which the efficiency of biodiesel usage in marine diesel engines can be assessed have not been developed. Despite the use of different types of biodiesel, general recommendations for determining its optimal concentration in diesel fuel have not been developed. Also, there are no recommendations for achieving economic and environmental efficiency of using a mixture of diesel and biodiesel fuel at different diesel operating modes.

The use of alternative fuels (including biofuels) in marine diesel engines improves the environmental performance of diesel engines and their impact on the environment. At the same time, the operational indicators of the diesel engine change, which leads to changes in dynamic and thermal loads on its parts, as well as the efficiency of its operation.

In this regard, the aim of the study was to determine the optimal operating modes of marine diesel engines when using biodiesel.

3. Materials and Methods

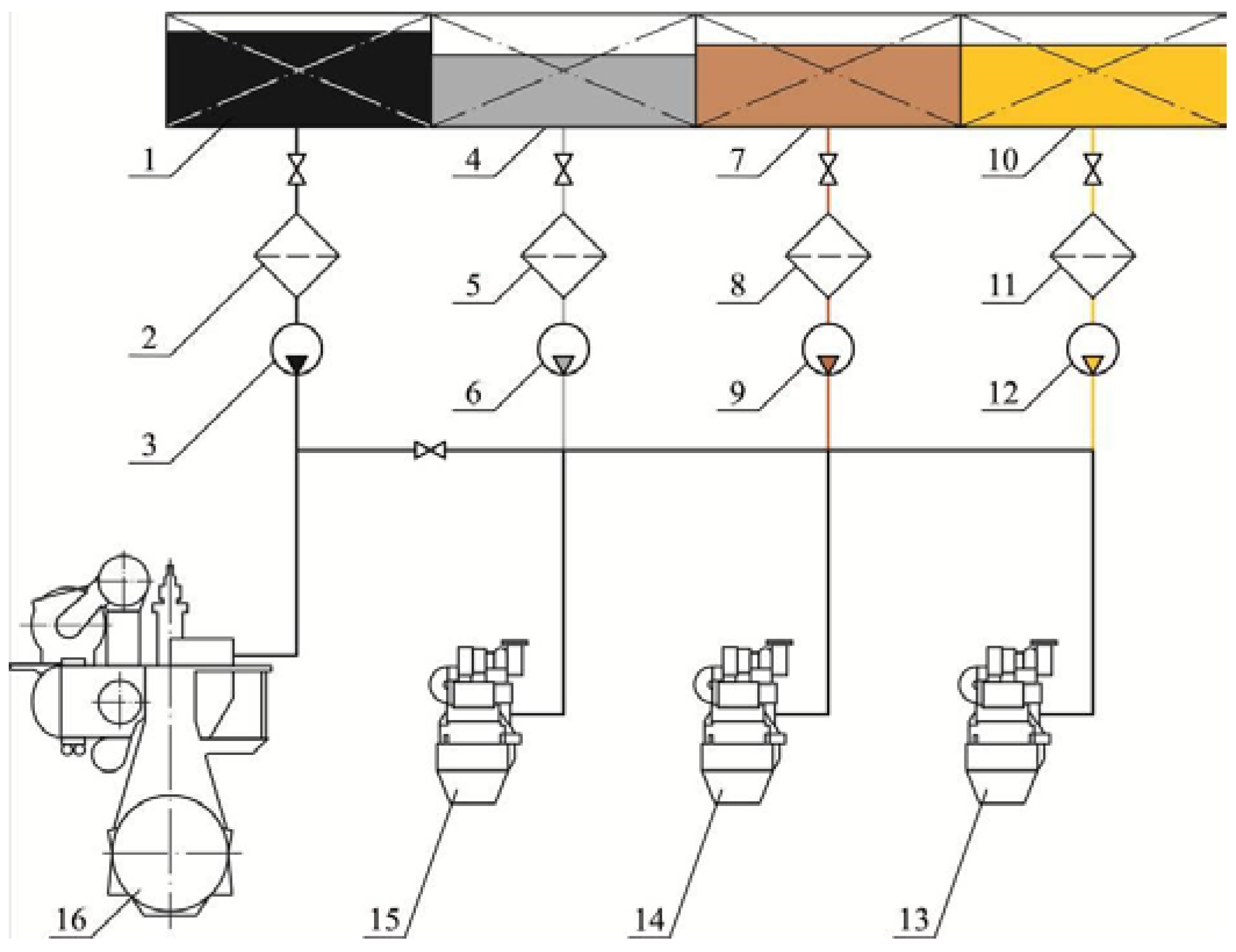

Studies on the influence of biodiesel fuel on the operational parameters of marine diesel engines were carried out on a Bulk Carrier class vessel with deadweight of 58,640 tons. A marine diesel engine 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group was used as the main engine and three marine diesel engines 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel were used as auxiliary ones. The main characteristics of the marine diesel engines are given in

Table 1.

The 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group and the 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel had a common fuel system, the scheme of which is shown in

Figure 3.

Fuel supply to the main engine 16 and auxiliary engines 13, 14, 15 was carried out from fuel tanks 1, 4, 7, 10 using fuel filters 2, 5, 8, 11 and fuel pumps 3, 6, 9, 12. The main parameters of the fuel system operation (pressure, flow rate, temperature, fuel viscosity) were controlled and maintained automatically. The speed and load of the main engine and auxiliary engines were also automatically maintained [

76,

77]. In addition, the load distribution between several auxiliary engines (two or three) was automatically maintained in case of their parallel operation [

78,

79]. The diesels were equipped with the ProPower diagnostic system, which provided monitoring of the main indicators of the working process – combustion pressure

pz, effective power

Ne, specific effective fuel oil consumption

be, exhaust gas temperature

tg. The ProPower system also monitored and analysed diesel exhaust gases, including determination of nitrogen oxides NO

X concentration [

80,

81]. The ProPower system belongs to the modern systems of diagnostics of the working process of marine diesel engines and is used on a large number of marine vessels [

82,

83].

The diesels were operated using DMA and RMG380 petroleum-based fuels and B10 and B30 biodiesel fuels. B10 and B30 fuels include 90 % or 70 % diesel fuel and 10 % or 30 % FAME fuel. The main characteristics of the fuels are given in

Table 2.

When the vessel was in the special environmental areas of SECAs, the diesels were operated with DMA fuel, and when the vessel was outside SECAs, they were operated with RMG380 fuel. In addition, the diesels used B10 and B30 fuels during the experiments. Throughout the experiment, fuel density and viscosity were continuously monitored using the ship's Unitor laboratory [

84,

85]. This ensured the homogeneity of the fuel and guaranteed the correctness of the experiments.

During the navigation passage, the diesels operated at different loads: main engine 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group – in the range of 25–95 % of rated power; auxiliary engines 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel – in the range of 35–80 % of rated power.

During the experimental studies, the main engine 5S60ME-C8 of the MAN-B&W Diesel Group was operated at equal intervals with RMG380 heavy fuel and B10 and B30 biodiesel at loads of 65 %, 75 %, 85 %, 95 % of rated power. The duration of the experiment for each of the loads was 1–3 hours and depended on the sailing conditions of the vessel.

The 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel auxiliary diesels were operated for equal time intervals with RMG380 heavy fuel and B10 and B30 biodiesel at loads of 50 %, 60 %, 70 %, 80 % of rated power. The duration of the experiment for each of the loads was 2–4 hours and depended on the energy requirements of the vessel.

The efficiency of using biofuels B10 and B30 was evaluated according to environmental and economic criteria. The concentration of nitrogen oxides in exhaust gases of diesel engines was taken as an ecological criterion – NO

X, g/(kW⋅h) [

86,

87] and as economic one – specific effective fuel oil consumption –

be, g/(kW⋅h) [

88,

89].

4. Results

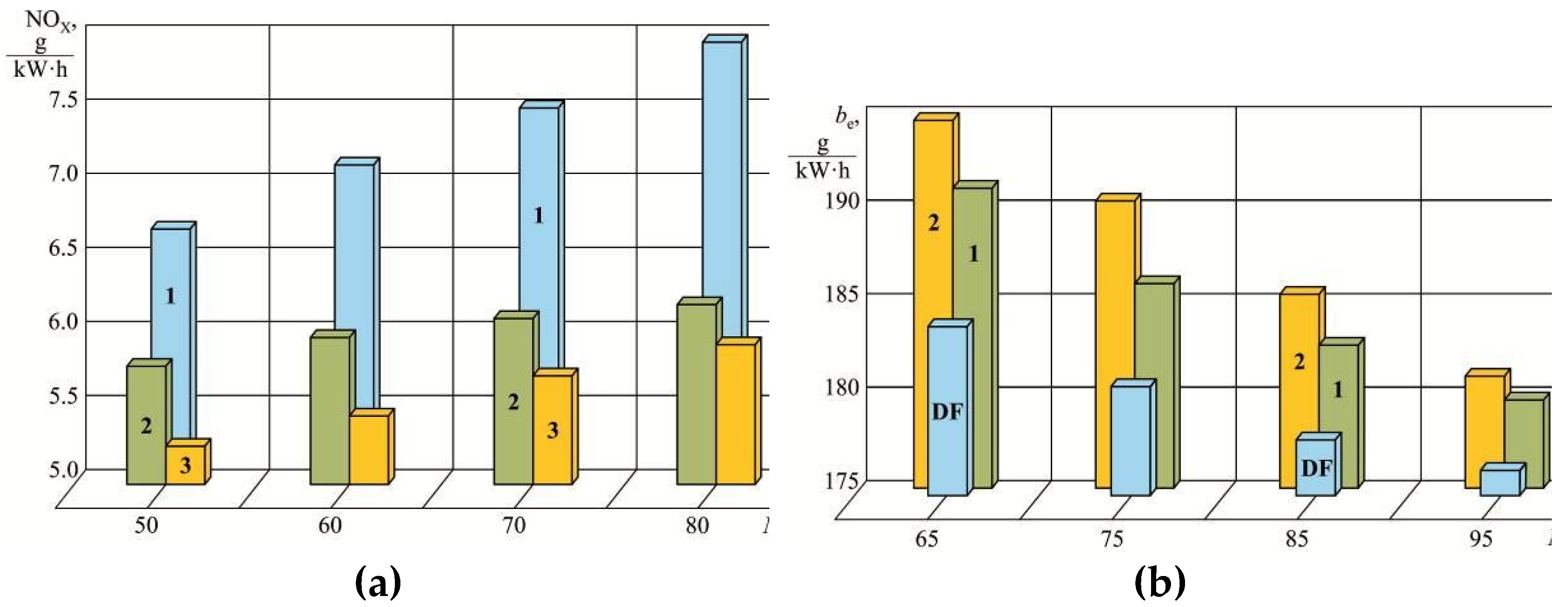

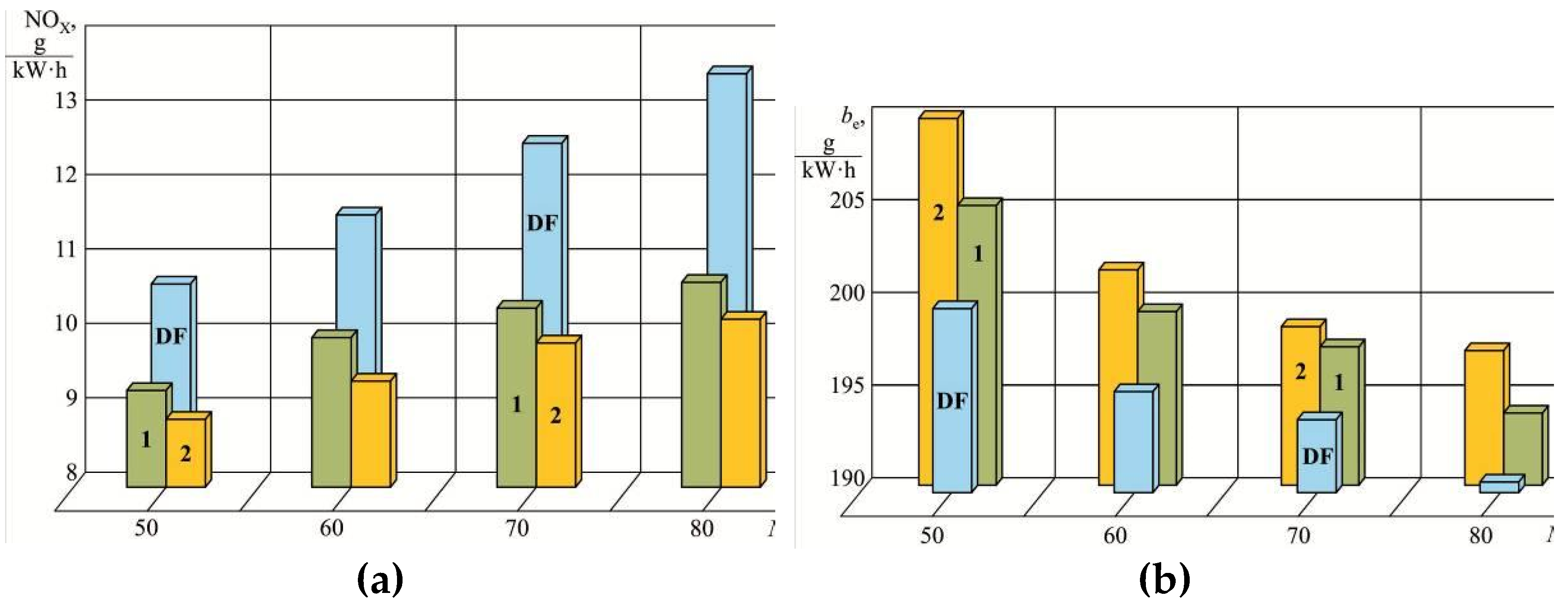

The dependences of nitrogen oxides concentration in exhaust gases NO

X, as well as specific effective fuel consumption

be for different loads of marine diesel engines when using heavy fuel RMG380 as well as biofuels B10 and B30 are shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 with the purpose of better visualization.

The use of biofuels helps to reduce the concentration of nitrogen oxides in exhaust gases – both for the 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group diesel engine and the 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel. However, the specific effective fuel consumption increases. The relative change of these parameters was estimated using the expressions:

relative reduction of nitrogen oxide concentration in exhaust gases

relative increase in specific effective fuel consumption

where

is the concentration of nitrogen oxides in exhaust gases when using diesel and biofuels (B10 or B30);

– specific effective fuel oil consumption when using biofuels (B10 or B30) and diesel fuel.

The above results show that both biofuel B10 and biofuel B30 contribute to the improvement of environmental friendliness of diesel engine operation (namely, provide a reduction in nitrogen oxides NOX emission). However, at the same time the efficiency of diesel engine operation deteriorates (specific effective fuel consumption increases), and for biofuel B30 at some operating modes the increase in specific effective fuel consumption is 4.5–6.0 % (diesel engine 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group) and 3.1–5.0 % (diesel engine 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel).

Further studies were carried out using B10 biofuel, which (in comparison with B30 biofuel) provides better economic performance of the diesel engine with comparatively the same environmental performance.

The use of biofuels changes the working cycle in the diesel cylinder, primarily the combustion process [

90,

91]. This leads to a change in the operational performance of diesel engines, and there arises the task of determining the phases of fuel supply (primarily the advance angle of fuel supply), at which the change in these parameters increases the efficiency of the diesel engine and improves its environmental performance [

92,

93]. This task can be solved by conducting experiments on the main operational modes of diesel engine operation.

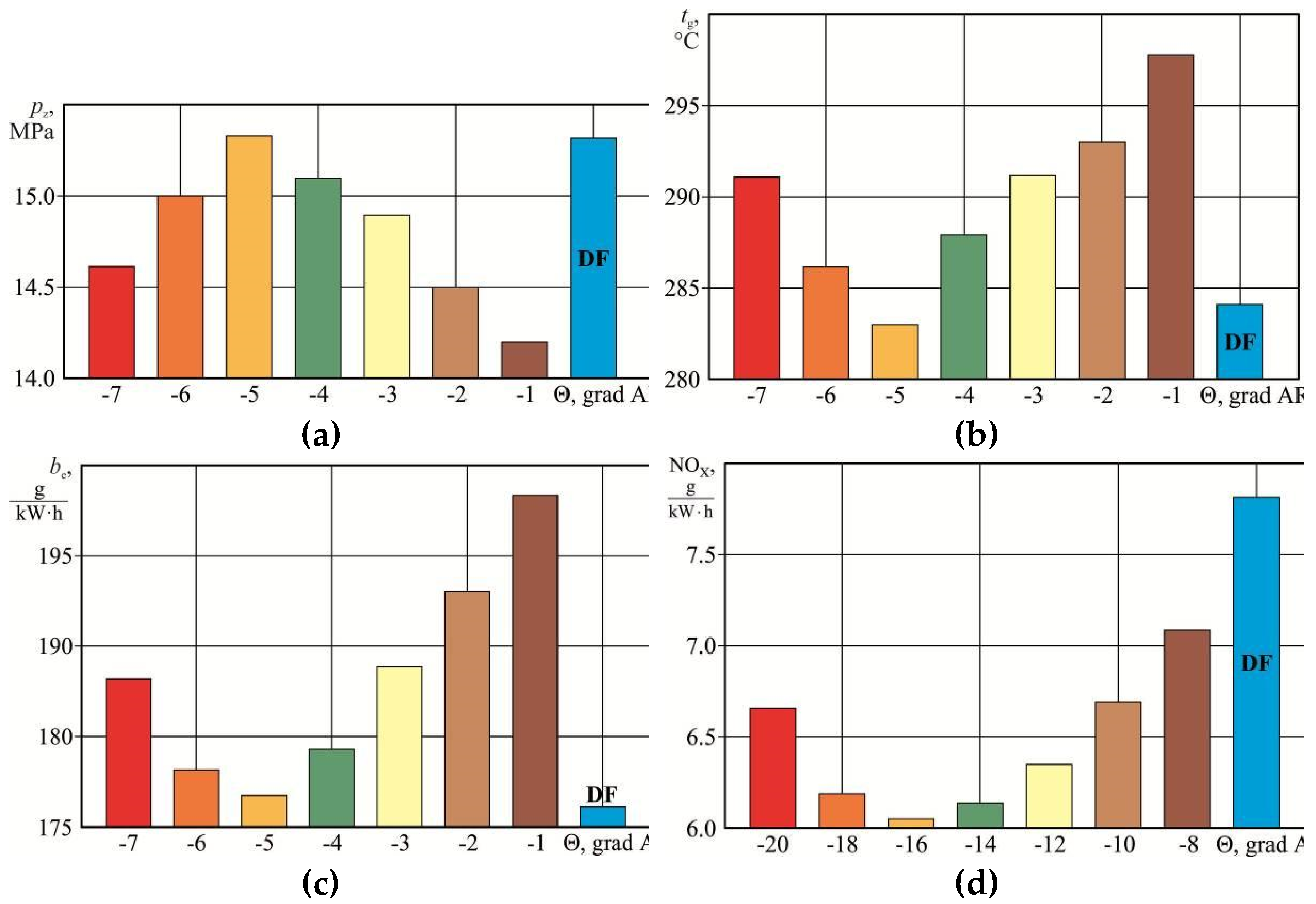

The studies were performed for the range of fuel advance angles recommended by the manufacturers θ, which were measured in degrees of crankshaft rotation angle – grad ARC and were as follows:

for diesel engine 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group – -1...-7 grad ARC;

for 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel – -20...-8 grad ARC.

At the same time as the most rational for diesel engine 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group angle -4 grad ARC is recommended, for diesel engine 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel – -14 grad ARC. These are the injection advance angles at which the diesels were operated when using diesel fuel. These are the angles that were chosen as the "baseline" for the B10 biofuel tests.

The maximum combustion pressure pz, exhaust gas temperature tg, specific effective fuel oil consumption be and nitrogen oxide concentration in exhaust gases NOX were selected as benchmarks for evaluating the performance of marine diesel engines. Their determination was performed with the help of the ProPower ship monitoring and diagnostics system. The choice of these indicators was justified as follows. The maximum combustion pressure characterises the energy efficiency of the diesel engine working cycle, with its increase the performance of all the main diesel engine indicators increases, first of all the average indicator pressure and indicator / effective power. The temperature of exhaust gases characterises the efficiency of fuel combustion. An increase in the exhaust gas temperature indicates a shift of the combustion process to the expansion line and afterburning of fuel in the exhaust receiver. The maximum combustion pressure and exhaust gas temperature are mandatory parameters that are monitored during diesel engine operation. Their values are determined for each individual cylinder, the average for all cylinders of the diesel engine, and the deviation of values for individual cylinders from the average is calculated. Specific effective fuel consumption characterises the fuel efficiency of diesel engine operation and characterises the economic feasibility of selecting certain fuel supply parameters. Specific fuel oil consumption is also directly proportional to the total fuel consumption (hourly or daily) and affects the ship's fuel reserves – an indicator that is relevant for sea transport vessels performing long sea or ocean passages without the possibility of bunkering. The concentration of nitrogen oxides in exhaust gases is the main indicator characterising the environmental performance of marine diesel engines. Its value is regulated in accordance with the requirements of Annex VI MARPOL and depends on the speed of the diesel engine and the year of construction of the vessel.

Figure 8.

Variation of performance indicators of 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W diesel engine at different advance angles of biodiesel B10 (a) – maximum combustion pressure; (b) – exhaust gas temperature; (c) – specific effective fuel oil consumption; (d) – concentration of nitrogen oxides in exhaust gases; DF – heavy diesel fuel.

Figure 8.

Variation of performance indicators of 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W diesel engine at different advance angles of biodiesel B10 (a) – maximum combustion pressure; (b) – exhaust gas temperature; (c) – specific effective fuel oil consumption; (d) – concentration of nitrogen oxides in exhaust gases; DF – heavy diesel fuel.

Figure 9.

Variation of performance indicators of 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel at different advance angles of biodiesel B10. (a) – maximum combustion pressure; (b) – exhaust gas temperature; (c) – specific effective fuel oil consumption; (d) – concentration of nitrogen oxides in exhaust gases; DF – heavy diesel fuel.

Figure 9.

Variation of performance indicators of 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel at different advance angles of biodiesel B10. (a) – maximum combustion pressure; (b) – exhaust gas temperature; (c) – specific effective fuel oil consumption; (d) – concentration of nitrogen oxides in exhaust gases; DF – heavy diesel fuel.

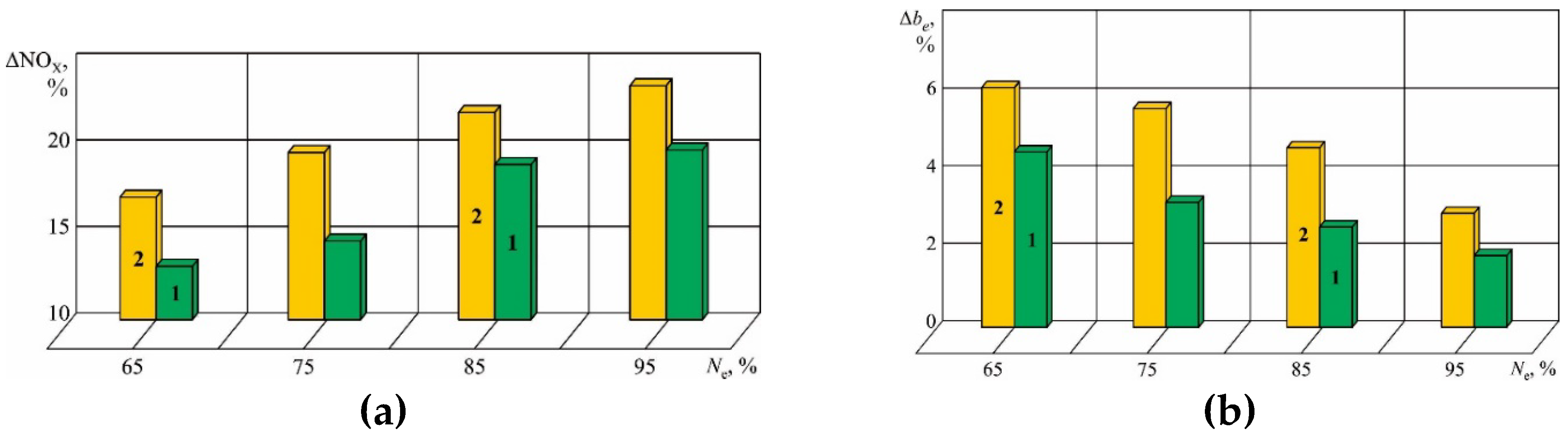

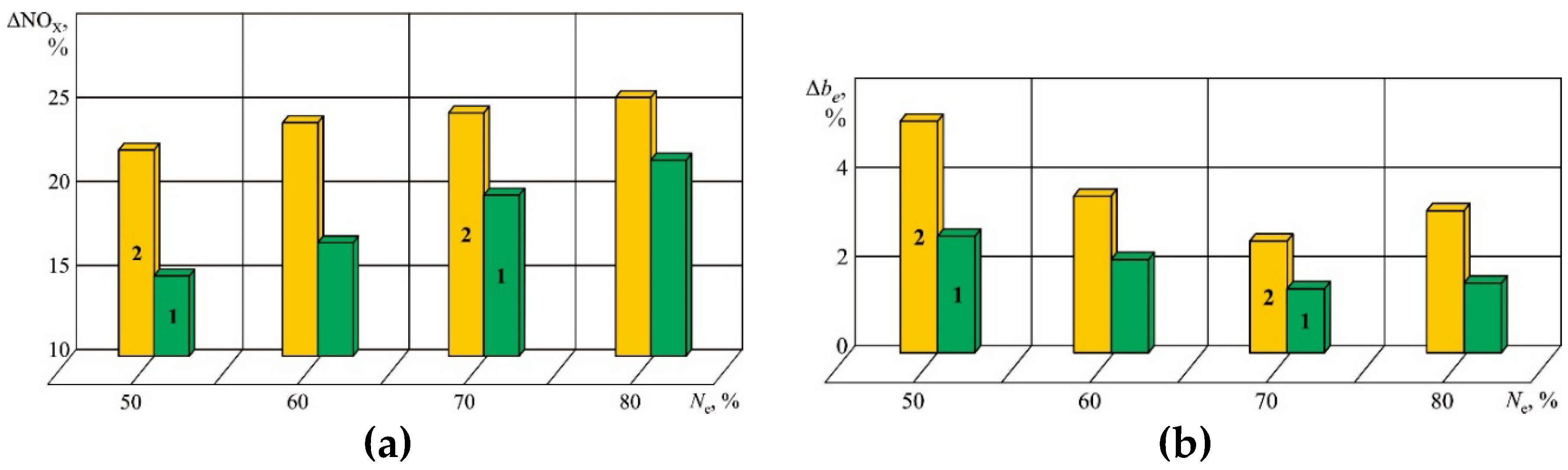

The relative change in the operating parameters of diesel engines at different advance angles of biodiesel B10 was carried out using the formulas:

relative reduction of nitrogen oxide concentration in exhaust gases

relative increase in specific effective fuel consumption

relative reduction of the maximum combustion pressure

relative increase in exhaust gas temperature:

where

– concentration of nitrogen oxides in exhaust gases, specific effective fuel consumption, maximum combustion pressure, temperature of exhaust gases when using diesel fuel;

– concentration of nitrogen oxides in exhaust gases, specific effective fuel consumption, maximum combustion pressure, and exhaust gas temperature at different advance angles of biodiesel B10.

The values that are obtained by formulae (3)-(6) are presented in

Table 13 and

Table 14.

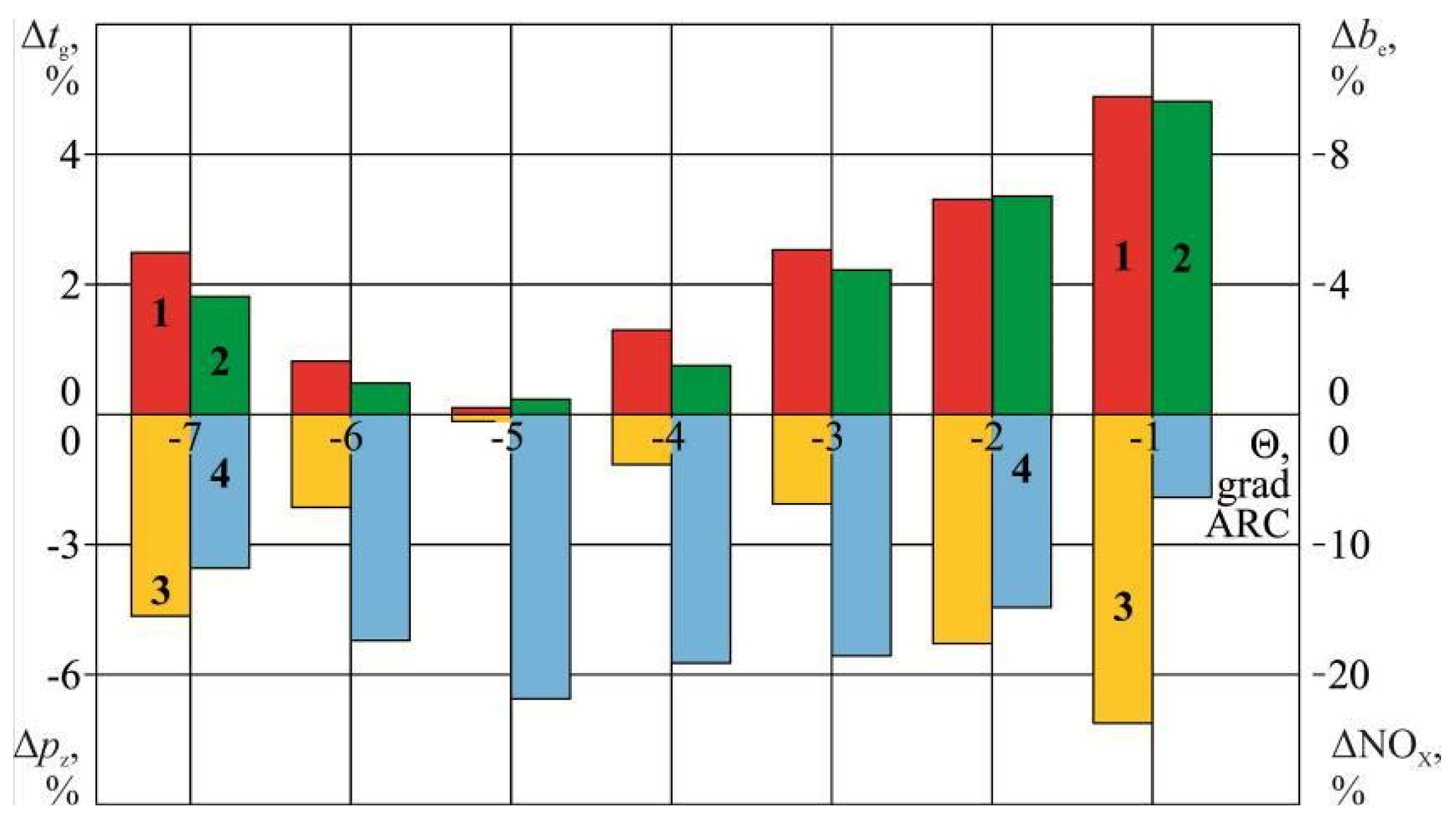

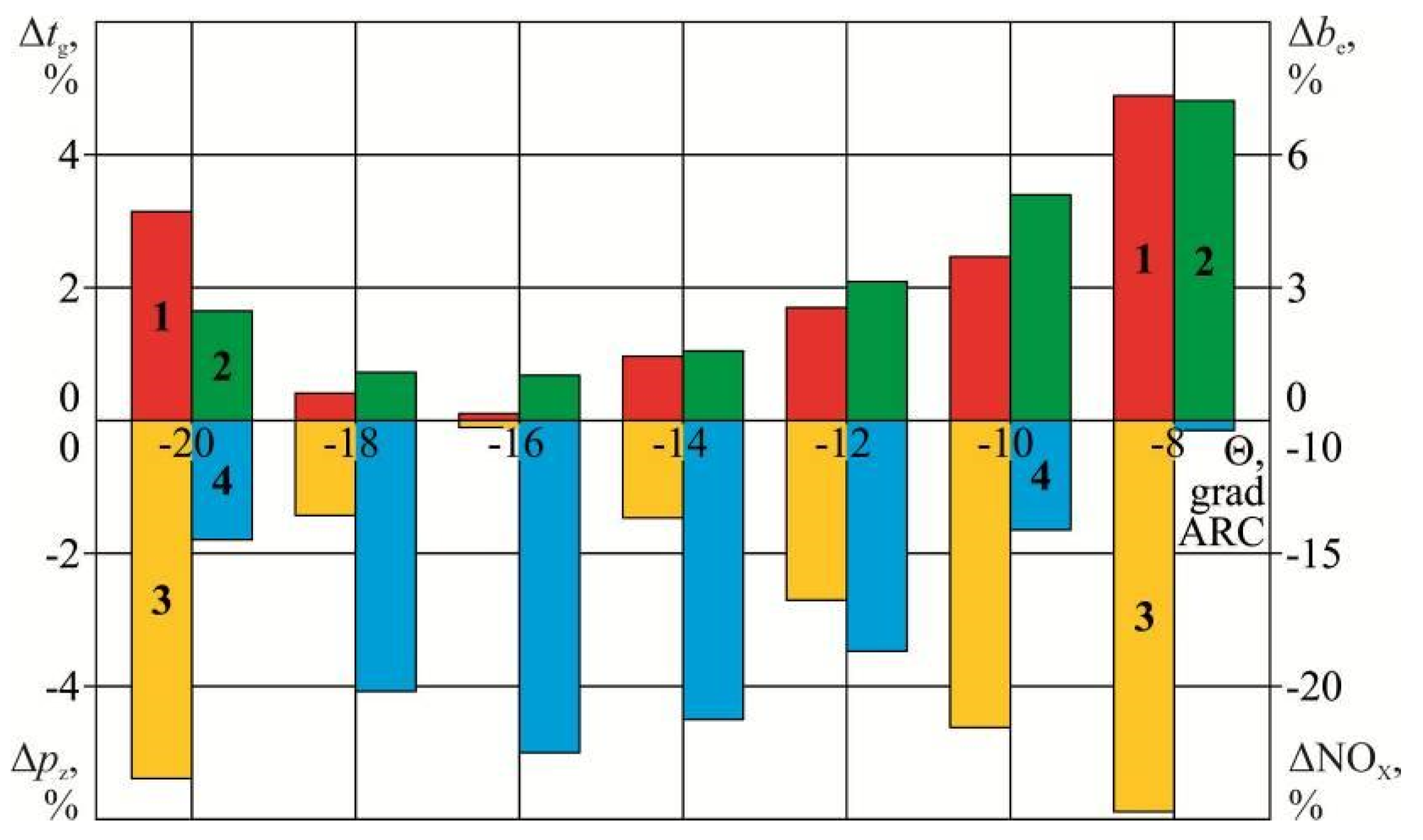

For a comprehensive assessment of the relative change in the performance indicators of diesel engines at different advance angles of biodiesel B10, the diagrams shown in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 are plotted.

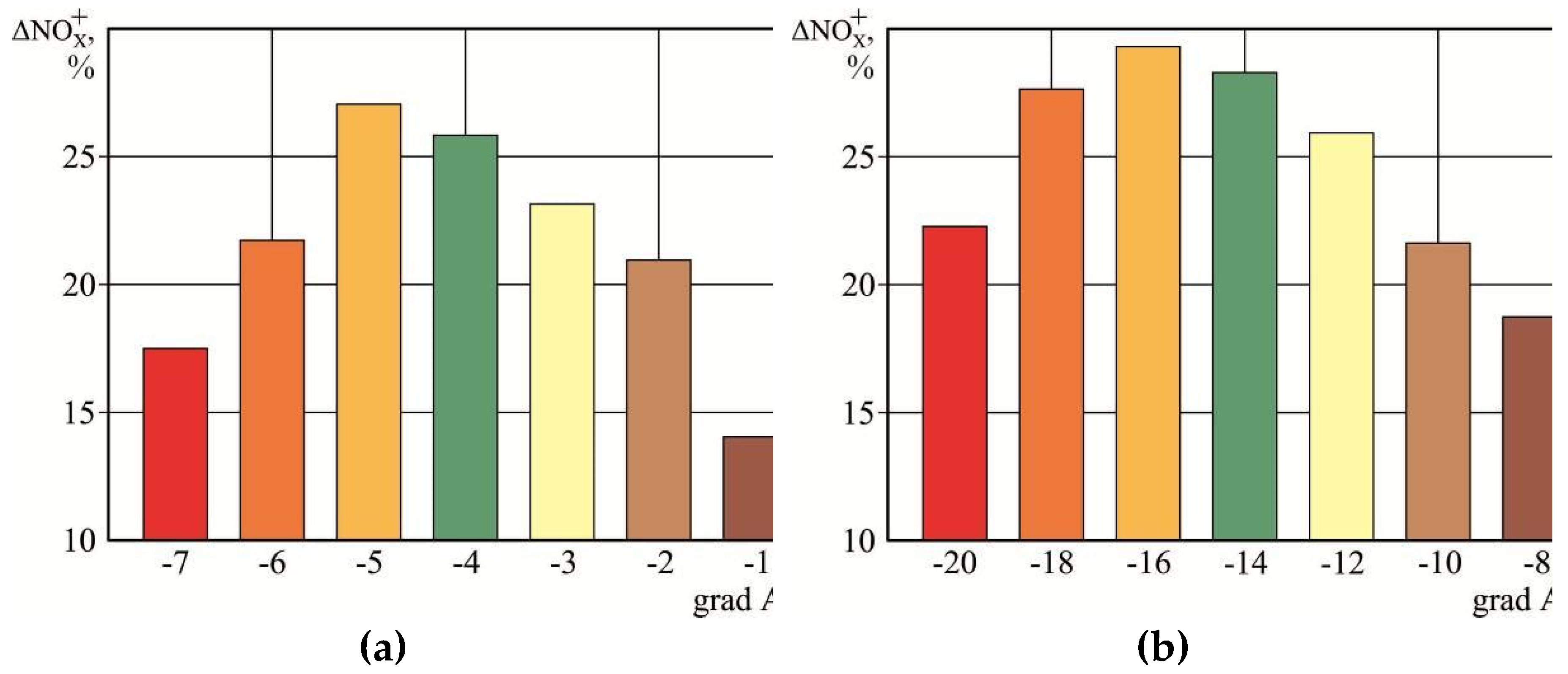

Ecological efficiency of B10 biodiesel use was evaluated by the value of ecological sustainability of marine diesel engines at different advance angles of B10 biodiesel supply. The value of environmental sustainability

was determined by the formula

where

is the maximum possible concentration of nitrogen oxides in exhaust gases according to the requirements of Annex VI MARPOL.

For diesel engine 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W

=14,4 g/(kW⋅h), for diesel engine 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel

is determined by the formula

where

n is the rotational speed, min

–1.

Considering the characteristics of the 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel

The values of environmental sustainability of

marine diesel engines 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W and 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel at different advance angles of biodiesel B10 are given in

Table 15 and

Table 16.

The higher the sustainability value is, the further the value of nitrogen oxide concentration in exhaust gases is from the Annex VI MARPOL regulated value.

During the research all the main parameters of the main and auxiliary diesel engines, as well as the parameters in the systems that ensure their functioning, were controlled and maintained within the required range. These included:

pressure in the cylinder at the end of compression, exhaust gas temperature, average indicator pressure, and the deviation of these indicators from the average value for all cylinders;

diesel shaft speed;

the valve timing (opening and closing angles of the purge and exhaust valves);

pressure and temperature of cooling water and circulation oil at the inlet and outlet of diesel engines;

fuel temperature and viscosity, as well as the technical condition of the high-pressure fuel equipment [

94,

95,

96,

97].

5. Discussion

One of the options for ensuring the environmental performance of marine diesel engines (primarily nitrogen oxide emissions NOX) is the use of biofuels. In addition, the sulphur content in these fuels does not exceed 0.1 % by mass, which makes it possible to use them in special ecological areas – SECAs.

When using biologically derived fuel in diesel engines, oxidation and combustion processes change (compared to the operation of a diesel engine using petroleum fuel), which leads to a change in the thermodynamics of the combustion process. This is the reason for changes in the main performance indicators of the diesel engine.

Increasing the efficiency of biofuel use consists not only in choosing its optimal composition, but also in determining the optimal advance angles of biofuel supply to the diesel cylinder. Changing the advance angle of biofuel supply (compared to the variant of diesel operation on diesel fuel) is necessary due to the change in the composition of the fuel mixture that burns in the diesel cylinder.

Dependences of the main operational indicators of both two-stroke and four-stroke diesel engines on the advance angle of fuel supply have a sinusoidal form and are characterised by the presence of an optimum – the minimum values of exhaust gas temperature, nitrogen oxide concentration in exhaust gases, specific effective fuel oil consumption, as well as the maximum value of combustion pressure.

In order to increase the efficiency of biofuel utilisation, it is necessary to shift the feeding process to the compression line – to increase the fuel advance angle, and the range of this change should be in accordance with the manufacturers' recommendations regarding possible angles of fuel feeding.

The optimum advance angle of biofuel is determined experimentally and depends on the characteristics of the diesel engine.

The use of biofuel (compared to diesel operation on diesel fuel) increases the environmental sustainability of the diesel engine, which occurs over the entire range of diesel operating modes. It increases the environmental stability margin, which can be understood as the relative difference between the maximum permissible and current concentration of nitrogen oxides in the exhaust gases.

6. Conclusion

One of the ways to ensure environmental efficiency and expand the range of environmental sustainability of marine diesel engines is the use of biofuels. One of the most common types of biofuels is biodiesel fuel FAME – Fatty Acid Methyl Ester. Marine diesel engines use fuel mixtures, the main part of which (70–90 %) is made of distillate grades of fuel, with FAME fuels used as an additive (10–30 %). Biofuels B10 and B30 were used as such mixtures during the studies. The experiments, which were carried out on marine diesel engines 5S60ME-C8.2 MAN-Diesel&Turbo and 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel, allow us to come up to the following conclusions.

1. Biofuels B10 (which contains 90 % distillate fuel and 10 % FAME biodiesel) and B30 (which contains 70 % distillate fuel and 30 % FAME biodiesel) compared to heavy fuel RMG380 provide a reduction in the concentration of nitrogen oxides in exhaust gases in the following range:

for the diesel 5S60ME-C8.2 MAN-Diesel&Turbo by 12.95–19.90 % (biofuel B10) and by 16.73–23.62 % (biofuel B30);

for the diesel 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel by 14.71–21.43 % (biofuel B10) and by 22.29–25.13 % (biofuel B30).

At the same time, when using biofuel, the specific effective fuel oil consumption increases:

for the diesel 5S60ME-C8.2 MAN-Diesel&Turbo by 1.70–4.37 % (biofuel B10) and by 2.84–6.01 % (biofuel B30);

for the diesel 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel by 1.55–2.51 % (biofuel B10) and by 2.59–5.03 % (biofuel B30).

The increase in specific effective fuel oil consumption in certain operating modes of diesel engines is a negative factor and may be the reason for limiting the use of biofuel.

2. Research to determine the effect of B10 biofuel on the performance of marine diesel engines has established that the use of biofuel changes the working process in the diesel cylinder. At the same time, depending on the biofuel injection advance angle, the following is possible:

reduction in maximum combustion pressure – by 1.31–7.19 % for the diesel 5S60ME-C8.2 MAN-Diesel&Turbo and by 1.50–5.99 % for the 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel diesel;

reduction in nitrogen oxide emissions – by 7.45–21.39 % for the diesel 5S60ME-C8.2 MAN-Diesel&Turbo and by 10.20–22.45 % for the diesel 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel;

increase in exhaust gas temperature by 0.70–4.93 % for the diesel engine 5S60ME-C8.2 MAN-Diesel&Turbo and by 0.62–4.63 % for the diesel engine 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel;

increase in effective fuel oil consumption by 0.57–9.66 % for the diesel engine 5S60ME-C8.2 MAN-Diesel&Turbo and by 1.57–8.38 % for the diesel engine 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel.

The comparable results obtained for the two-stroke diesel engine 5S60ME-C8.2 MAN-Diesel&Turbo and the four-stroke engine 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel confirm the correctness of the experiments and the reliability of the conclusions. The optimal biofuel feed advance angle is determined experimentally and must comply with the limits recommended by the diesel engine operating instructions.

3. The use of B10 biofuel increases the environmental sustainability of marine diesel engines. The environmental sustainability margin is:

for the diesel 5S60ME-C8.2 MAN-Diesel&Turbo by 13.75–26.74 %;

for the diesel 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel by 18.28–29.42%.

This increases the environmental safety of diesel engines in the event of emergency situations, as well as accidental and short-term emissions of exhaust gases into the atmosphere with an increased content of nitrogen oxides – phenomena that are possible in starting modes of diesel operation, as well as in modes of sudden load changes.

It is the increased environmental friendliness of marine diesel engines in the case of using biofuel that is the most positive criterion and contributes to the intensity of the use of biofuel in the power plants of marine vessels.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.; methodology, S.S., O.K. and O.V.; validation, O.M., R.R., and T.S.; data curation, O.K., T.S. and O.M.; writing, original draft preparation, O.K., R.R. and O.V.; writing, review and editing, S.S., T.S. and O.V.; visualization, S.S., O.M. and O.K.; investigation, S.S., R.R.., T.S., and O.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sagin, S.; Madey, V.; Sagin, A.; Stoliaryk, T.; Fomin, O.; Kuˇcera, P. Ensuring Reliable and Safe Operation of Trunk Diesel Engines of Marine Transport Vessels. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Du, T.; Duan, S.; Qu, H.; Wang, K.; Xing, H.; Zou, Y.; Sun, P. Analysis of Exhaust Pollutants from Four-Stroke Marine Diesel Engines Based on Bench Tests. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, P. Experimental Investigation into the Effects of Fuel Dilution on the Change in Chemical Properties of Lubricating Oil Used in Fuel Injection Pump of Pielstick PA4V185 Marine Diesel Engine. Lubricants, 2022; 10, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoko, I.; Stanivuk, T.; Franic, B.; Bozic, D. Comparative Analysis of CO2 Emissions, Fuel Consumption, and Fuel Costs of Diesel and Hybrid Dredger Ship Engines. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorokhobin, I.; Burmaka, I.; Fusar, I.; Burmaka, O. Simulation Modeling for Evaluation of Efficiency of Observed Ship Coordinates. TransNav: The International Journal on Marine Navigation and Safety of Sea Transportation, 2022; 16(1), 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, O.; Onyshchenko, S.; Onishchenko, O.; Lohinov, O.; Ocheretna, V. Integral Approach to Vulnerability Assessment of Ship’s Critical Equipment and Systems. Transactions on Maritime Science. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wright, L.A. A Comparative Review of Alternative Fuels for the Maritime Sector: Economic, Technology, and Policy Challenges for Clean Energy Implementation. World. 2020, 2, 456–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, H.; Kim, Y.H.; Hong, J.-P.; Hwang, D.; Kang, H.J. Marine Demonstration of Alternative Fuels on the Basis of Propulsion Load Sharing for Sustainable Ship Design. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Ringsberg, J.W. Ship energy performance study of three wind-assisted ship propulsion technologies including a parametric study of the Flettner rotor technology. Ships and Offshore Structures. 2020, 15(3), 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, T.G.; Ramirez, J.; Ristovskim, Z.; Brown, R.J. Global impact of recent IMO regulation on marine fuel oil refining processes and ship emissions. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment. 2019; 70, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.-W.; Yeo, S.; Lee, W.-J. Assessment of Shipping Emissions on Busan Port of South Korea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagin, S.V. , Kuropyatnyk, O.A. The Use of Exhaust Gas Recirculation for Ensuring the Environmental Performance of Marine Diesel Engines. Naše More Int. J. Marit. Sci. Technol. 2018, 65, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Müller-Casseres, E.; Belchior, C.R.P.; Szklo, A. Evaluating the Readiness of Ships and Ports to Bunker and Use Alternative Fuels: A Case Study from Brazil. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, O.; Onyshchenko, S.; Onishchenko, O. Development measures to enhance the ecological safety of ships and reduce operational pollution to the environment. Scientific Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport. 2023, 118, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, H.; Hitchmough, D.; Armin, M.; Blanco-Davis, E. A Study on the Viability of Fuel Cells as an Alternative to Diesel Fuel Generators on Ships. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inal, O.B.; Zincir, B.; Dere, C.; Charpentier, J.-F. Hydrogen Fuel Cell as an Electric Generator: A Case Study for a General Cargo Ship. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Han, M. Industrial Development Status and Prospects of the Marine Fuel Cell: A Review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, S.; Shi, W.; Xu, X. Proposed Z-Source Electrical Propulsion System of a Fuel Cell/Supercapacitor-Powered Ship. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagin, S.V. Decrease in mechanical losses in high-pressure fuel equipment of marine diesel engines. Mater. Int. Conf. Sci. Res. SCO Series. Synerg. Integr. 2019, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Wei, H.; Tan, Z.; Xue, S.; Qiu, Y.; Wu, S. Biodiesel as Dispersant to Improve the Stability of Asphaltene in Marine Very-Low-Sulfur Fuel Oil. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagin, S.V.; Semenov, O.V. Motor Oil Viscosity Stratification in Friction Units of Marine Diesel Motors. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2016, 13, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrzljak, V.; Poljak, I.; Kosor, M.; ˇCulin, J. Bisection Method for the Heavy Fuel Oil Tank Filling Problem at a Liquefied Natural Gas Carrier. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagin, S.; Kuropyatnyk, O.; Sagin, A.; Tkachenko, I.; Fomin, O.; Píštěk, V.; Kučera, P. Ensuring the Environmental Friendliness of Drillships during Their Operation in Special Ecological Regions of Northern Europe. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likhanov, V.A.; Lopatin, O.P.; Yurlov, A.S.; Anfilatova, N.S. Simulation of soot formation in a tractor diesel engine running on rapeseed oil methyl ether and methanol. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2021; 839, 052057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likhanov, V.A.; Lopatin, O.P. Dynamics of soot formation and burnout in a gas diesel cylinder. IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 2020; 862, 062033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varbanets, R.; Fomin, O.; Píštěk, V.; Klymenko, V.; Minchev, D.; Khrulev, A.; Zalozh, V.; Kučera, P. Acoustic Method for Estimation of Marine Low-Speed Engine Turbocharger Parameters. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Li, X. Effects of fuel types and fuel sulfur content on the characteristics of particulate emissions in marine low-speed diesel engine. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2020, 27, 37229–37236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Cho, J.; Lee, J. Mixing Properties of Emulsified Fuel Oil from Mixing Marine Bunker-C Fuel Oil and Water. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagin, S.V.; Solodovnikov, V.G. Cavitation Treatment of High-Viscosity Marine Fuels for Medium-Speed Diesel Engines. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2015, 9, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelyubov, D.V.; Fakhrutdinov, M.I.; Sarkisyan, A.A.; Sharin, E.A.; Ershov, M.A.; Makhova, U.A.; Makhmudova, A.E.; Klimov, N.A.; Rogova, M.Y.; Savelenko, V.D.; et al. New Prospects of Waste Involvement in Marine Fuel Oil: Evolution of Composition and Requirements for Fuel with Sulfur Content up to 0.5%. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ershov, M.A.; Savelenko, V.D.; Makhmudova, A.E.; Rekhletskaya, E.S.; Makhova, U.A.; Kapustin, V.M.; Mukhina, D.Y.; Abdellatief, T.M.M. Technological Potential Analysis and Vacant Technology Forecasting in Properties and Composition of Low-Sulfur Marine Fuel Oil (VLSFO and ULSFO) Bunkered in Key World Ports. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Vith, W.; Unger, J.L. Assessing Particulate Emissions of Novel Synthetic Fuels and Fossil Fuels under Different Operating Conditions of a Marine Engine and the Impact of a Closed-Loop Scrubber. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatu˘g, Ç.; Arslano˘glu, Y.; Guedes Soares, C. Feasibility Analysis of the Effects of Scrubber Installation on Ships. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnes, H.; Fridell, E.; Moldanová, J. Effects of Marine Exhaust Gas Scrubbers on Gas and Particle Emissions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagin, S.V.; Sagin, S.S.; Madey, V. Analysis of methods of managing the environmental safety of the navigation passage of ships of maritime transport. Technology Audit and Production Reserves. 2023, 4, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuropyatnyk, O.A.; Sagin, S.V. Exhaust Gas Recirculation as a Major Technique Designed to Reduce NOх Emissions from Marine Diesel Engines. Naše More Int. J. Marit. Sci. Technol. 2019; 66(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zablotsky, Yu.V.; Sagin, S.V. Enhancing Fuel Efficiency and Environmental Specifications of a Marine Diesel When using Fuel Additives. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagin, S.V.; Kuropyatnyk, O.A.; Zablotskyi, Y.V.; Gaichenia, O.V. Supplying of Marine Diesel Engine Ecological Parameters. Naše More Int. J. Marit. Sci. Technol. 2022, 69, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, E.; Can, Ö. Effects of EGR, injection retardation and ethanol addition on combustion, performance and emissions of a DI diesel engine fueled with canola biodiesel/diesel fuel blend. Energy. 2020, 244, 123129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Deng, Y.; Chen, L.; Han, W.; Jiaqiang, E.; Wei, K.; Han, D.; Zhang, B. Hydrocarbon emission control of a hydrocarbon adsorber and converter under cold start of the gasoline engine. Energy. 2022, 239, 122138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Peragón, F.; Torres-Jiménez, E.; Lešnik, L.; Arma, O. Methodology improvements to simulate performance and emissions of engine transient cycles from stationary operating modes. A case study applied to biofuels. Fuel. 2022, 312, 122977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adami, G.; Figari, M. Multi-Parametric Methodology for the Feasibility Assessment of Alternative-Fuelled Ships. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maceiras, R.; Alfonsin, V.; Alvarez-Feijoo, M.A.; Llopis, L. Assessment of Selected Alternative Fuels for Spanish Navy Ships According to Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagin, S.V.; Sagin, S.S.; Fomin, O.; Gaichenia, O.; Zablotskyi, Y.; Píˇstˇek, V.; Kuˇcera, P. Use of biofuels in marine diesel engines for sustainable and safe maritime transport. Renewable Energy. 2024, 224, 120221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdevicius, M.; Semaskaite, V.; Paulauskiene, T.; Uebe, J. Impact and Technical Solutions of Hydrodynamic and Thermodynamic Processes in Liquefied Natural Gas Regasification Process. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Lu, H.; Lu, Q.; Yan, J. Thermo-Mechanical Coupling Analysis of the Sealing Structure Stress of LNG Cryogenic Hose Fittings. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruško, D.; Karabai´c, D.; Bajsi´c, I.; Kutin, J. Ageing of Liquified Natural Gas during Marine Transportation and Assessment of the Boil-Off Thermodynamic Properties. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zou, J.; Lei, Q.; Lu, X.; Chen, Z. Thermo-Economic Analysis and Multi-Objective Optimization of a Novel Power Generation System for LNG-Fueled Ships. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Jeong, B.; Choi, J.-H.; Lee, W.-J. Life Cycle Assessment of LPG Engines for Small Fishing Vessels and the Applications of Bio LPG Fuel in Korea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, K.W.; Kim, M.; Hur, J.-J. Development of a Marine LPG-Fueled High-Speed Engine for Electric Propulsion Systems. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.; Lee, J.; Chang, D. Heat Integration of Liquid Hydrogen-Fueled Hybrid Electric Ship Propulsion System. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, M.; Blanco-Davis, E.; Platt, O.; Armin, M. Life-Cycle and Applicational Analysis of Hydrogen Production and Powered Inland Marine Vessels. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazdauskas, M.; Lebedevas, S. Optimization of Combustion Cycle Energy Efficiency and Exhaust Gas Emissions of Marine Dual-Fuel Engine by Intensifying Ammonia Injection. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Ying, W.; Chen, A.; Chen, G.; Liu, Y.; Lyu, Z.; Qiao, Z.; Li, J.; Zhou, Z.; Deng, X. Study on the Impact of Ammonia–Diesel Dual-Fuel Combustion on Performance of a Medium-Speed Diesel Engine. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tian, J.; Li, J.; Wang, S.; Zhong, Y.; Dong, R.; Gao, S.; Cao, C.; Tan, D. Investigation on combustion, performance and emission characteristics of a diesel engine fueled with diesel/alcohol/n-butanol blended fuels. Fuel. 2022, 320, 123975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labeckas, G.; Slavinskas, S.; Mickevicius, T. Experimental investigation of biodiesel-n-butanol fuels blends on performance and emissions in a diesel engine. Combustion Engines. 2022, 188(1), 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visan, N.A.; Niculescu, D.C.; Ionescu, R.; Dahlin, E.; Eriksson, M.; Chiriac, R. Study of Effects on Performances and Emissions of a Large Marine Diesel Engine Partially Fuelled with Biodiesel B20 and Methanol. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Lyu, Z.; Luo, P.; Zhang, G.; Ying, W.; Chen, A.; Xiao, H. Effects of Methanol–Ammonia Blending Ratio on Performance and Emission Characteristics of a Compression Ignition Engine. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomin, O.; Lovska, A.; Kučera, P.; Píštěk, V. Substantiation of Improvements for the Bearing Structure of an Open Car to Provide a Higher Security during Rail/Sea Transportation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puškár, M.; Kopas, M.; Sabadka, D.; Kliment, M.; Šoltésová, M. Reduction of the Gaseous Emissions in the Marine Diesel Engine Using Biodiesel Mixtures. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8(5), 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovskii, A.Yu; Altoiz, B.A.; Butenko, V.F. Structural Properties and Model Rheological Parameters of an ELC Layer of Hexadecane. Journal of Engineering Physics and Thermophysics. 2019, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strus, M.; Poprawski, W. Efficiency of the Diesel engine fuelled with the advanced biofuel Bioxdiesel. Combustion Engines. 2021, 186, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J. , Tian, J.; Xie, G.; Tan, D., Qin, B.; Huang, Y.; Cui, S. Effects of Different Diesel-Ethanol Dual Fuel Ratio on Performance and Emission Characteristics of Diesel Engine. Processes. 2021, 9, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonický, J.; Feriancová, P.; Tulík, J.; Hujo, L’. ; Tkáˇc, Z.; Kuchar, P.; Tomi´c, M.; Kaszkowiak, J. Assessment of Technical and Ecological Parameters of a Diesel Engine in the Application of New Samples of Biofuels. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagin, S.; Karianskyi, S.; Madey, V.; Sagin, A.; Stoliaryk, T.; Tkachenko, I. Impact of Biofuel on the Environmental and Economic Performance of Marine Diesel Engines. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visan, N.A.; Carlanescu, R.; Niculescu, D.C.; Chiriac, R. Study on the Cumulative Effects of Using a High-Efficiency Turbocharger and Biodiesel B20 Fuelling on Performance and Emissions of a Large Marine Diesel Engine. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Li, J.; Guo, H.; Wang, X.; Jiang, G. Numerical Method for Predicting Emissions from Biodiesel Blend Fuels in Diesel Engines of Inland Waterway Vessels. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madey, V.V. Usage of biodiesel in marine diesel engines. Austrian Journal of Technical and Natural Sciences. Scientific journal. 2021; 7-8, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagin, S.; Madey, V.; Stoliaryk, T. Analysis of mechanical energy losses in marine diesels. Technol. Audit. Prod. Reserves 2021, 5, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labeckas, G.; Slavinskas, S.; Mickevicius, T. Experimental investigation of biodiesel-n-butanol fuels blends on performance and emissions in a diesel engine. Combustion Engines. 2022, 188, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, H.-j.; Jeon, S.-k. Analysis of Characteristic Changes of Blended Very Low Sulfur Fuel Oil on Ultrasonic Frequency for Marine Fuel. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madey, V. Assessment of the efficiency of biofuel use in the operation of marine diesel engines. Technology Audit and Production Reserves. 2022, 2(1(64)), 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likhanov, V.A.; Lopatin, O.P.; Vylegzhanin, P.N. Calculation of geometric parameters of diesel fuel ignition flares. IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 2020, 862, 062074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ershov, M.A.; Grigorieva, E.V.; Abdellatief, T.M.M.; Chernysheva, E.A.; Makhin, D.Y.; Kapustin, V.M. A New Approach for Producing Mid-Ethanol Fuels E30 Based on Low-Octane Hydrocarbon Surrogate Blends. Fuel Processing Technology. 2021, 213, 106688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salova, T.; Lekomtsev, P.; Likhanov, V.; Lopatin, O.; Belov, E. Development of calculation methods and optimization of working processes of heat engines. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2700, 050015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorb, S.; Levinskyi, M.; Budurov, M. Sensitivity Optimisation of a Main Marine Diesel Engine Electronic Speed Governor. Scientific Horizons. 2021, 24, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuropyatnyk, O.A. Reducing the emission of nitrogen oxides from marine diesel engines. International Conference “Scientific research of the SCO countries: synergy and integration. 2020; 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorb, S.; Popovskii, A.; Budurov, M. Adjustment of speed governor for marine diesel generator engine. International Journal of GEOMATE. 2023, 25, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varbanets, R.; Shumylo, O.; Marchenko, A.; Minchev, D.; Kyrnats, V.; Zalozh, V.; Aleksandrovska, N.; Brusnyk, R.; Volovyk, K. Concept of vibroacoustic diagnostics of the fuel injection and electronic cylinder lubrication systems of marine diesel engines. Polish maritime research. 2022, 29, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-U.; Hwang, S.-C.; Han, S.-H. Numerical and Experimental Study on NOx Reduction According to the Load in the SCR System of a Marine Boiler. J. Mar. Sci.Eng. 2023, 11, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ershov, M.A.; Grigorieva, E.V.; Abdellatief, T.M.M. Hybrid Low-Carbon High-Octane Oxygenated Environmental Gasoline Based on Low-Octane Hydrocarbon Fractions. Science of the Total Environment. 2021, 756, 142715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minchev, D.S; Gogorenko, O.A.; Kyrnats, V.I; Varbanets, R.A; Moshentsev, Y.L.; Píštěk, V.; Kučera, P.; Shumylo, O.M. Prediction of centrifugal compressor instabilities for internal combustion engines operating cycle simulation. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part D: Journal of Automobile Engineering. 2023, 237(2-3), 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, S.; Varbanets, R.; Minchev, D.; Malchevsky, V.; Zalozh, V. Vibrodiagnostics of marine diesel engines in IMES GmbH systems. Ships and Offshore Structures. 2022, 18, 1535–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagin, S.V.; Solodovnikov, V.G. Estimation of Operational Properties of Lubricant Coolant Liquids by Optical Methods. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2017, 12, 8380–8391. [Google Scholar]

- Sagin, S.V.; Semenov, О.V. Marine Slow-Speed Diesel Engine Diagnosis with View to Cylinder Oil Specification. Am. J. Appl. Sciences. 2016, 13, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultanbekov, R.; Denisov, K.; Zhurkevich, A.; Islamov, S. Reduction of Sulphur in Marine Residual Fuels by Deasphalting to Produce VLSFO. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagin, S.V.; Karianskyi, S.; Sagin, S.S.; Volkov, O.; Zablotskyi, Y.; Fomin, O.; Píˇstˇek, V.; Kuˇcera, P. Ensuring the safety of maritime transportation of drilling fluids by platform supply-class vessel. Applied Ocean Research. 2023, 140, 103745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagin, S.V.; Stoliaryk, T.O. Comparative assessment of marine diesel engine oils. Austrian Journal of Technical and Natural Sciences. Scientific journal. 2021. 7-8, 29-35. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, S.; Liu, D. Research on the Ignition Strategy of Diesel Direct Injection Combined with Jet Flame on the Combustion Character of Natural Gas in a Dual-Fuel Marine Engine. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopatin, O.P. Investigation of the combustion process in a dual-fuel engine. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2024, 2697, 012079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopatin, O.P. Modeling of physico-chemical processes in the combustion chamber of gas diesel. AIP Conf. Proc. 2024, 2969, 050008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorb, S.; Budurov, M. Increasing the accuracy of a marine diesel engine operation limit by thermal factor. International Journal of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics. 2021, 6, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagin, S.V. Determination of the optimal recovery time of the rheological characteristics of marine diesel engine lubricating oils. International Conference “Process Management and Scientific Developments”. 2020. 4, 195-202. [CrossRef]

- Popovskii, Yu.M.; Sagin, S.V. , Khanmamedov, S.A.; Grebenyuk, M.N.; Teregerya, V.V. Designing, calculation, testing and reliability of machines: influence of anisotropic fluids on the operation of frictional components. Russ. Eng. Res. 1996, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zablotsky, Yu.V.; Sagin, S.V. Maintaining Boundary and Hydrodynamic Lubrication Modes in Operating High-pressure Fuel Injection Pumps of Marine Diesel Engines. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagin, A.S., Zablotskyi, Yu.V. Reliability maintenance of fuel equipment on marine and inland navigation vessels. Austrian Journal of Technical and Natural Sciences. Scientific journal. 2021. 7-8, 14-17. [CrossRef]

- Varbanets, R.; Zalozh, V.; Shakhov, A.; Savelieva, I.; Piterska, V. Determination of top dead centre location based on the marine diesel engine indicator diagram analysis. Diagnostyka. 2020, 21, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Sulphur emission control areas. 1 – The North American SECA with most of United States, Canadian coast and Hawaii; 2 – The United States Caribbean SECA with Puerto Rico and the United States Virgin Islands; 3 – The North Sea SECA with The English Channel; 4 – The Baltic Sea SECA; 5 – All Europe Union Ports.

Figure 1.

Sulphur emission control areas. 1 – The North American SECA with most of United States, Canadian coast and Hawaii; 2 – The United States Caribbean SECA with Puerto Rico and the United States Virgin Islands; 3 – The North Sea SECA with The English Channel; 4 – The Baltic Sea SECA; 5 – All Europe Union Ports.

Figure 2.

Annex VI MARPOL emission requirements for nitrogen oxides NOX.

Figure 2.

Annex VI MARPOL emission requirements for nitrogen oxides NOX.

Figure 3.

Principal fuel scheme of marine diesel engines 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group and 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel:.1 – heavy fuel (S about 0.5 %); 2, 5, 8, 11 – fuel filter; 3, 6, 9, 12 – fuel pump; 4 – diesel fuel (S<0.1 %); 7 – biodiesel B10; 10 – biodiesel B30; 13, 14, 15 – auxiliary engine 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel; 16 - main engine 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group

Figure 3.

Principal fuel scheme of marine diesel engines 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group and 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel:.1 – heavy fuel (S about 0.5 %); 2, 5, 8, 11 – fuel filter; 3, 6, 9, 12 – fuel pump; 4 – diesel fuel (S<0.1 %); 7 – biodiesel B10; 10 – biodiesel B30; 13, 14, 15 – auxiliary engine 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel; 16 - main engine 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group

Figure 4.

Dependence of nitrogen oxides concentration in exhaust gases NOX (a), and specific effective fuel oil consumption be (b) for different loads of marine diesel engine 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group. DF – diesel fuel; 1 – biofuel B10; 2 – biofuel B30.

Figure 4.

Dependence of nitrogen oxides concentration in exhaust gases NOX (a), and specific effective fuel oil consumption be (b) for different loads of marine diesel engine 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group. DF – diesel fuel; 1 – biofuel B10; 2 – biofuel B30.

Figure 5.

Dependence of nitrogen oxides concentration in exhaust gases NOX (a), and specific effective fuel oil consumption be (b) for different loads of ship diesel engine 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel. DF – diesel fuel; 1 – biofuel B10; 2 – biofuel B30.

Figure 5.

Dependence of nitrogen oxides concentration in exhaust gases NOX (a), and specific effective fuel oil consumption be (b) for different loads of ship diesel engine 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel. DF – diesel fuel; 1 – biofuel B10; 2 – biofuel B30.

Figure 6.

Relative reduction of nitrogen oxides concentration in exhaust gases (a) and relative increase of specific effective fuel oil consumption (b) of 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group diesel engine under different experimental conditions.

Figure 6.

Relative reduction of nitrogen oxides concentration in exhaust gases (a) and relative increase of specific effective fuel oil consumption (b) of 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group diesel engine under different experimental conditions.

Figure 7.

Relative decrease of nitrogen oxide concentration in exhaust gas (a) and relative increase of specific effective fuel oil consumption (a) of 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel under different experimental conditions.

Figure 7.

Relative decrease of nitrogen oxide concentration in exhaust gas (a) and relative increase of specific effective fuel oil consumption (a) of 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel under different experimental conditions.

Figure 10.

Relative change of operational indicators of the ship diesel engine 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W at different advance angles of biodiesel B10:.1 – temperature of exhaust gases; 2 – specific effective fuel oil consumption; 3 – maximum combustion pressure; 4 – concentration of nitrogen oxides in exhaust gases.

Figure 10.

Relative change of operational indicators of the ship diesel engine 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W at different advance angles of biodiesel B10:.1 – temperature of exhaust gases; 2 – specific effective fuel oil consumption; 3 – maximum combustion pressure; 4 – concentration of nitrogen oxides in exhaust gases.

Figure 11.

Relative change of operational indicators of 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel at different advance angles of biodiesel B10:.1 – temperature of exhaust gases; 2 – specific effective fuel oil consumption; 3 – maximum combustion pressure; 4 – concentration of nitrogen oxides in exhaust gases.

Figure 11.

Relative change of operational indicators of 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel at different advance angles of biodiesel B10:.1 – temperature of exhaust gases; 2 – specific effective fuel oil consumption; 3 – maximum combustion pressure; 4 – concentration of nitrogen oxides in exhaust gases.

Figure 12.

Environmental sustainability of marine diesel engines 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W (a) and 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel (b) at different B10 biodiesel advance angles.

Figure 12.

Environmental sustainability of marine diesel engines 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W (a) and 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel (b) at different B10 biodiesel advance angles.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of marine diesel engines.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of marine diesel engines.

| Characteristic |

5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group |

6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel |

| Cylinder diameter, m |

0.6 |

0.165 |

| Piston stroke, m |

2.4 |

0.21 |

| Type |

two strokes |

four strokes |

| Quantity |

1 |

3 |

| Power, kW |

8200 |

530 |

| Rotational speed, min-1

|

92 |

1200 |

| Specific fuel consumption, kg/(kW⋅h) |

0.176 |

0.191 |

Table 2.

Main characteristics of fuels.

Table 2.

Main characteristics of fuels.

| Characterisation |

Fuel type |

| DMA |

RMG380 |

B10 |

B30 |

| Density at 20° C, kg/m3

|

894 |

942 |

891 |

889 |

| Viscosity at 40° C, sSt |

6,4 |

376 |

6,26 |

6,12 |

| Sulphur content, % |

0.072 |

0.43 |

0.065 |

0.058 |

| Calorific value, kJ/kg |

43,680 |

40,020 |

43,686 |

43,032 |

Table 3.

Nitrogen oxide concentration in exhaust gases of a 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group marine diesel engine under different experimental conditions.

Table 3.

Nitrogen oxide concentration in exhaust gases of a 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group marine diesel engine under different experimental conditions.

| Load, % |

Type of fuel |

| B10 |

B30 |

RMG380 |

| 65 |

9.21 |

8.81 |

10.58 |

| 75 |

9.92 |

9.32 |

11.64 |

| 85 |

10.32 |

9.88 |

12.65 |

| 95 |

10.75 |

10.25 |

13.42 |

Table 4.

Specific effective fuel oil consumption of the 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group marine diesel engine under different experimental conditions.

Table 4.

Specific effective fuel oil consumption of the 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group marine diesel engine under different experimental conditions.

| Load, % |

Type of fuel |

| B10 |

B30 |

RMG380 |

| 65 |

191 |

194 |

183 |

| 75 |

186 |

190 |

180 |

| 85 |

182 |

185 |

177 |

| 95 |

179 |

181 |

176 |

Table 5.

Nitrogen oxide concentration in exhaust gases of 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel under different experimental conditions.

Table 5.

Nitrogen oxide concentration in exhaust gases of 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel under different experimental conditions.

| Load, % |

Type of fuel |

| B10 |

B30 |

RMG380 |

| 50 |

5.74 |

5.23 |

6.73 |

| 60 |

5.92 |

5.42 |

7.11 |

| 70 |

6.02 |

5.64 |

7.48 |

| 80 |

6.16 |

5.87 |

7.84 |

Table 6.

Specific effective fuel oil consumption of 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel under different experimental conditions.

Table 6.

Specific effective fuel oil consumption of 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel under different experimental conditions.

| Load, % |

Type of fuel |

| B10 |

B30 |

RMG380 |

| 50 |

204 |

209 |

199 |

| 60 |

199 |

202 |

195 |

| 70 |

196 |

198 |

193 |

| 80 |

194 |

197 |

191 |

Table 7.

Relative reduction of nitrogen oxide concentration in exhaust gases of 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group marine diesel engine under different experimental conditions.

Table 7.

Relative reduction of nitrogen oxide concentration in exhaust gases of 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group marine diesel engine under different experimental conditions.

| Load, % |

Type of fuel |

| B10 |

B30 |

| 65 |

12.95 |

16.73 |

| 75 |

14.78 |

19.93 |

| 85 |

18.42 |

21.90 |

| 95 |

19.90 |

23.62 |

Table 8.

Relative increase in specific effective fuel oil consumption of 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group diesel engine under different experimental conditions.

Table 8.

Relative increase in specific effective fuel oil consumption of 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group diesel engine under different experimental conditions.

| Load, % |

Type of fuel |

| B10 |

B30 |

| 65 |

4.37 |

6.01 |

| 75 |

3.33 |

5.56 |

| 85 |

2.82 |

4.52 |

| 95 |

1.70 |

2.84 |

Table 9.

Relative reduction of nitrogen oxide concentration in exhaust gases of 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel at different experimental conditions.

Table 9.

Relative reduction of nitrogen oxide concentration in exhaust gases of 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel at different experimental conditions.

| |

Type of fuel |

| B10 |

B30 |

| 50 |

14.71 |

22.29 |

| 60 |

16.74 |

23.77 |

| 70 |

19.52 |

24.60 |

| 80 |

21.43 |

25.13 |

Table 10.

Relative increase in specific effective fuel oil consumption of 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel under different experimental conditions.

Table 10.

Relative increase in specific effective fuel oil consumption of 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel under different experimental conditions.

| Load, % |

Type of fuel |

| B10 |

B30 |

| 50 |

2.51 |

5.03 |

| 60 |

2.05 |

3.59 |

| 70 |

1.55 |

2.59 |

| 80 |

1.57 |

3.14 |

Table 11.

Experimental results (diesel 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group).

Table 11.

Experimental results (diesel 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W Diesel Group).

| Indicator |

Fuel advance angle, θ, grad ARC |

DF |

| -7 |

-6 |

-5 |

-4 |

-3 |

-2 |

-1 |

| pz, MPa |

14.6 |

15 |

15.3 |

15.1 |

14.9 |

14.5 |

14.2 |

15.3 |

|

tg, °C |

291 |

286 |

284 |

288 |

291 |

293 |

298 |

284 |

|

be, g/(kW⋅h) |

183 |

178 |

177 |

179 |

184 |

188 |

193 |

176 |

| NOX, g/(kW⋅h) |

11.88 |

11.22 |

10.55 |

10.75 |

11.05 |

11.35 |

12.42 |

13.42 |

Table 12.

Experimental results (diesel 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel).

Table 12.

Experimental results (diesel 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel).

| Indicator |

Fuel advance angle, θ, grad ARC |

DF |

| -20 |

-18 |

-16 |

-14 |

-12 |

-10 |

-8 |

| pz, MPa |

15.8 |

16.45 |

16.7 |

16.45 |

16.25 |

15.95 |

15.7 |

16.7 |

|

tg, °C |

334 |

326 |

324 |

328 |

330 |

332 |

339 |

324 |

|

be, g/(kW⋅h) |

198 |

195 |

195 |

194 |

199 |

203 |

207 |

191 |

| NOX, g/(kW⋅h) |

6.68 |

6.21 |

6.08 |

6.16 |

6.37 |

6.72 |

7.04 |

7.84 |

Table 13.

Relative change of performance parameters of 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W diesel engine at different B10 biodiesel advance angles.

Table 13.

Relative change of performance parameters of 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W diesel engine at different B10 biodiesel advance angles.

| Indicator |

Fuel advance angle, θ, grad ARC |

| -7 |

-6 |

-5 |

-4 |

-3 |

-2 |

-1 |

| Δpz, MPa |

4.58 |

1.96 |

0 |

1.31 |

2.61 |

5.23 |

7.19 |

| Δtg. °C |

2.46 |

0.70 |

0 |

1.41 |

2.46 |

3.17 |

4.93 |

| Δbe, g/(kW⋅h) |

3.98 |

1.14 |

0.57 |

1.70 |

1.55 |

6.82 |

9.66 |

| ΔNOX, g/(kW⋅h) |

11.48 |

16.39 |

21.39 |

19.90 |

17.66 |

15.43 |

7.45 |

Table 14.

Relative change in performance parameters of 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel at different B10 biodiesel advance angles.

Table 14.

Relative change in performance parameters of 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel at different B10 biodiesel advance angles.

| Indicator |

Fuel advance angle, θ, grad ARC |

| -20 |

-18 |

-16 |

-14 |

-12 |

-10 |

-8 |

| Δpz, MPa |

5.39 |

1.50 |

0 |

1.50 |

2.70 |

4.49 |

5.99 |

| Δtg, °C |

3.09 |

0.62 |

0 |

1.23 |

1.85 |

2.47 |

4.63 |

| Δbe, g/(kW⋅h) |

3.66 |

2.09 |

2.09 |

1.57 |

4.19 |

6.29 |

8.38 |

| ΔNOX, g/(kW⋅h) |

14.80 |

20.79 |

22.45 |

21.43 |

18.75 |

14.29 |

10.20 |

Table 15.

Environmental sustainability of the 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W diesel engine at different B10 biodiesel advance angles.

Table 15.

Environmental sustainability of the 5S60ME-C8 MAN-B&W diesel engine at different B10 biodiesel advance angles.

| Indicator |

Fuel advance angle, θ, grad ARC |

| -7 |

-6 |

-5 |

-4 |

-3 |

-2 |

-1 |

|

, % |

17.5 |

22.08 |

26.74 |

25.35 |

23.26 |

21.18 |

13.75 |

Table 16.

Environmental sustainability of 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel at different B10 biodiesel advance angles.

Table 16.

Environmental sustainability of 6DL-16 Daihatsu Diesel at different B10 biodiesel advance angles.

| Indicator |

Fuel advance angle, θ, grad ARC |

| -20 |

-18 |

-16 |

-14 |

-12 |

-10 |

-8 |

|

, % |

22.46 |

27.91 |

29.42 |

28.49 |

26.06 |

21.99 |

18.28 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).