3.1. Phase Structure, Stability, and Transformations on High-Temperature Annealing of the As-Cast Alloy

The calculated phase fraction vs temperature plot for our alloy is shown in

Figure 1a. The BCC/B2 phase fraction remains relatively flat between 40-45% in the range from 500

oC-1100

oC, while the FCC phase fraction reduces sharply below 900 C, primarily competing with sigma and D0

24 ordered phases. At lower temperatures, a number of additional ordered FCC and BCC based phases are predicted, which should not impact the high temperature behavior, but might prove deleterious to room temperature properties, if formed.

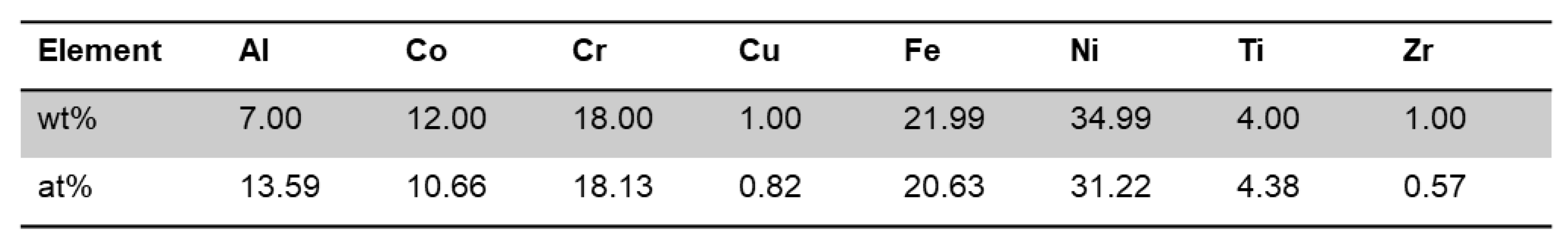

A combination of SEM EDS and EBSD,

Figure 1b–d, reveals the as-cast alloy to be dual phase, composed of an FeCrCo rich FCC and a NiAlTi rich BCC. The cellular microstructure has fine FCC lamella in a continuous BCC matrix with both vermicular and Widmanstätten lathe morphologies visible. A coarse extracellular FCC phase separates the lamellar regions. Small regions of secondary BCC are visible inside the extracellular FCC regions. From EBSD, it was found that the average size of FCC grains is ~9 μm, with two peaks in the size distribution corresponding to the lamellar regions (~5 μm) and coarse extracellular regions (~20μm). Grain size in the BCC phase showed two populations corresponding to the continuous interlamellar BCC, between 15-40 μm, and the fine scale BCC phases formed in the extracellular FCC or separated by intersecting FCC lamella, between 0.5-4 μm in size (

Figure S1). The phase fraction is relatively even, with about 55% FCC and 44% BCC, and the remaining 1% composed of sigma forming amongst the lamellar FCC structures. An additional NiZr rich phase can be observed closer to the center of the cast ingot, forming at the interface of the coarse FCC and BCC phases (

Figure S2).

The thermal series of diffraction spectra taken during in-situ heating XRD, plotted in

Figure 2a, shows the persistence of the duplex structure up to 1000

oC, after which the BCC peak has disappeared by 1200

oC leaving a fully FCC microstructure. DSC,

Figure 2c, shows three distinct endothermic events, with a broad peak at 900

oC, a small sharp peak at around 1150

oC and a large peak between 1200

oC and 1325

oC, centered at 1275

oC. The endotherm at 900

oC is likely due to a disordering transformation in the FCC phase as shown by the associated inflection in the thermal expansion of the FCC peaks between 800

oC and 1000

oC. The sharp endotherm at 1150

oC corresponds to the dissolution of the BCC phase, as confirmed by the spectra in

Figure 2a, and the final endotherm at 1275

oC likely corresponds to the melting of the alloy. This confirms that annealing the material up to 1100

oC should remove persistent low temperature ordered phases and homogenize the alloy while maintaining the dual phase structure.

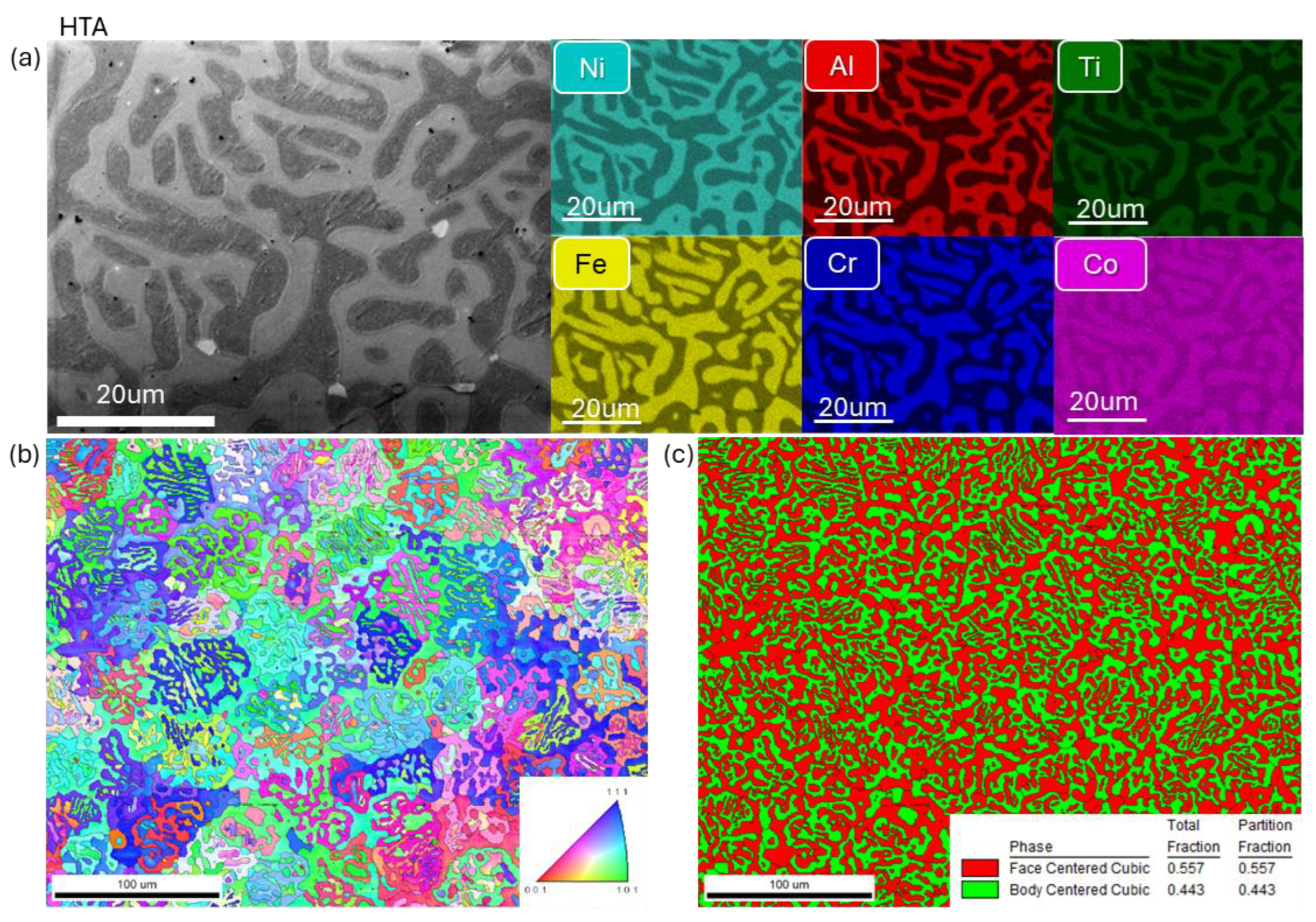

After thermal treatment, the microstructure in the HTA samples, shown in

Figure 3, has coarsened significantly as compared to the as-cast. The prior cellular structure has transformed into a bicontinuous network of FCC and BCC phases, the previous lamellar morphology retained in regions of discreet FCC phases. The NiZr intermetallic phase persists after annealing, having globularized from the weblike structures observed in the as-cast structure (

Figure S3). While the sigma phase was not observed, the phase fractions after annealing are nearly identical to the as-cast with ~44% BCC and ~56% FCC. After annealing, EBSD again shows two populations of grain sizes in the FCC spanning from 1.3-11.8 μm and from 20.4-42.4 μm, corresponding to the former lamellar and extracellular regions respectively. The BCC grains vary in a single broad population from ~5μm-33μm, with a sharp peak at 27.7 μm. (

Figure S4) The similar phase fractions before and after annealing indicate that there was little chemical driving force for microstructural coarsening. The primary driving force for the observed coarsening therefore appears to be the shape instability of the lamellar FCC phase, as only minimal growth was observed in the boundary regions. A much larger volume fraction of globularized FCC grains are observed than BCC grains, with the later remaining predominantly continuous (

Figure S5).

The substantial microstructural coarsening following HTA heat treatment obscures precise identification of the initial instability mechanisms responsible for the structural evolution. EBSD of the AC condition (

Figure S5), reveals a mix of lamella with both trans-lamellar grain boundaries and boundary-free lamella, suggesting the FCC phase globularized through combined boundary splitting and cylinderization mechanisms [

18]. Boundary splitting occurs when the tensional balance between a through-thickness boundary and the adjacent phase boundary induces sufficient thermal grooving to cleave the lamellar structure. Cylinderization, conversely, results from capillary forces generated from the curvature difference between the lamellar edges and flat surfaces, driving edge recession and lamellar breakdown. More extensive thermal grooving effects are visible in larger extracellular FCC regions of the HTA-treated samples (

Figure S5).

The pronounced increase in the grain size of the FCC phase during annealing without an accompanying change in phase fraction, highlights that microstructural evolution primarily depends on lamellar instability rather than phase instability.

Samples of both the AC and HTA alloy were cold rolled in multiple passes until failure as a quick assessment of the thermal treatments effect on room temperature mechanical behavior. Cracks were visible on the AC sample after just 3% reduction in thickness, whereas the HTA condition was able to undergo a 38% reduction in thickness before crack formation occurred, having regained a notable degree of ductility after thermal treatment (

Figure S6).

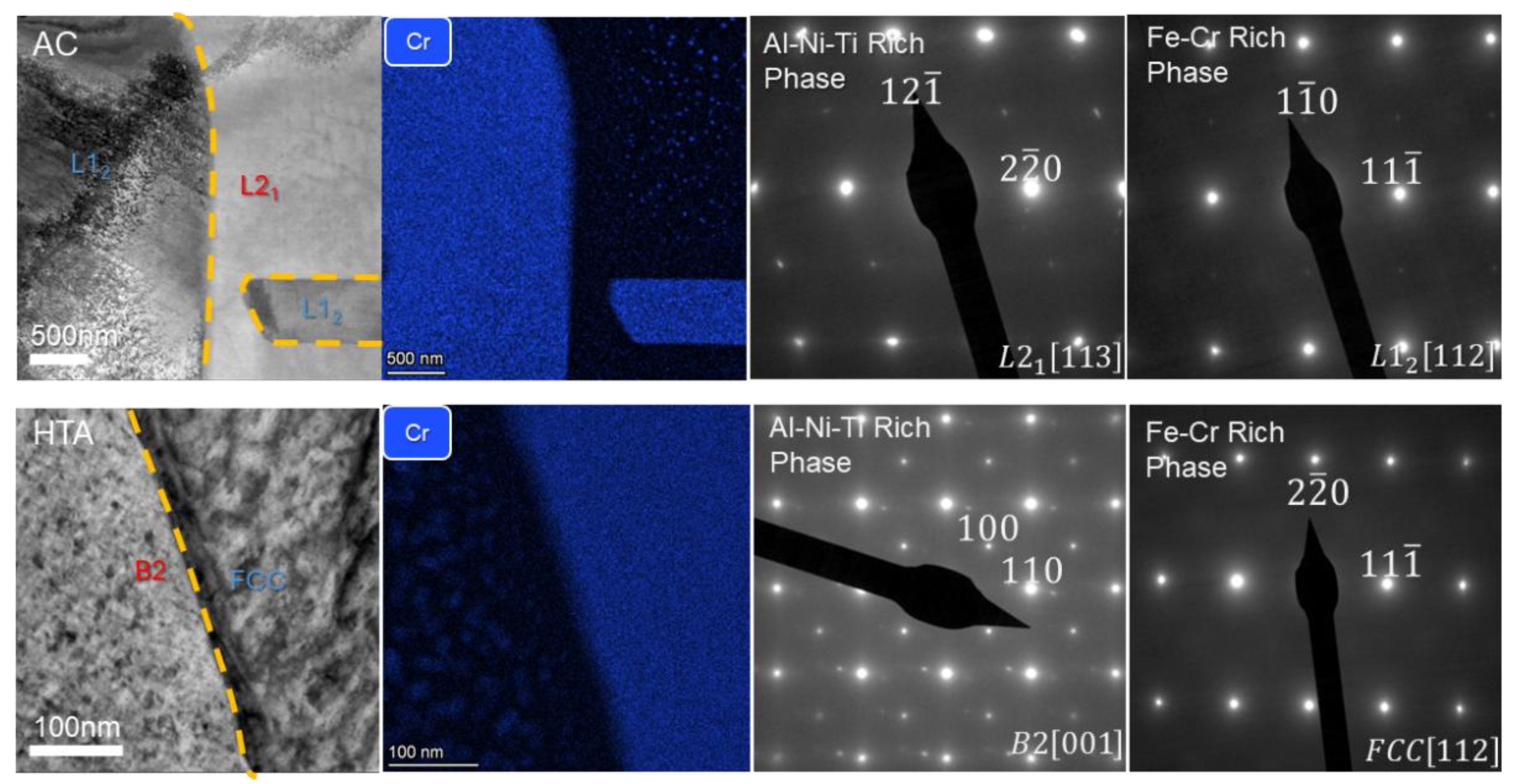

TEM analysis of both the undeformed samples reveals the FCC phases to be compositional homogenous, while a dispersion of Cr rich nanoprecipitates are observed in the BCC phase both before and after annealing. Superlattice spots in the SAED patterns of the AC sample at (110) and (121) indicate the presence of L1

2 and L2

1 ordering in the FCC and BCC phases respectively. It should be noted that while (121) is typically a forbidden reflection, the absence of an equivalent d-spacing in BCC and B2 structures, in combination with the presence of the L2

1 (111) peak in XRD (

Figure S7) has been considered sufficient to identify the ordering. The inclusion of Ti in NiAl B2 forming HEAs has been previously shown to stabilize the formation of the Ni

2AlTi L2

1 phase [

19]. This structure transforms to a disordered FCC+B2 structure after annealing at 1100

oC, though the Cr rich BCC nanoprecipitates appear to persist. This BCC phase has been established to form due to a conditional Cr miscibility gap in B2 ordered NiAl [

20].

3.2. Plastic Flow Behavior Under Compression as Function of Temperature

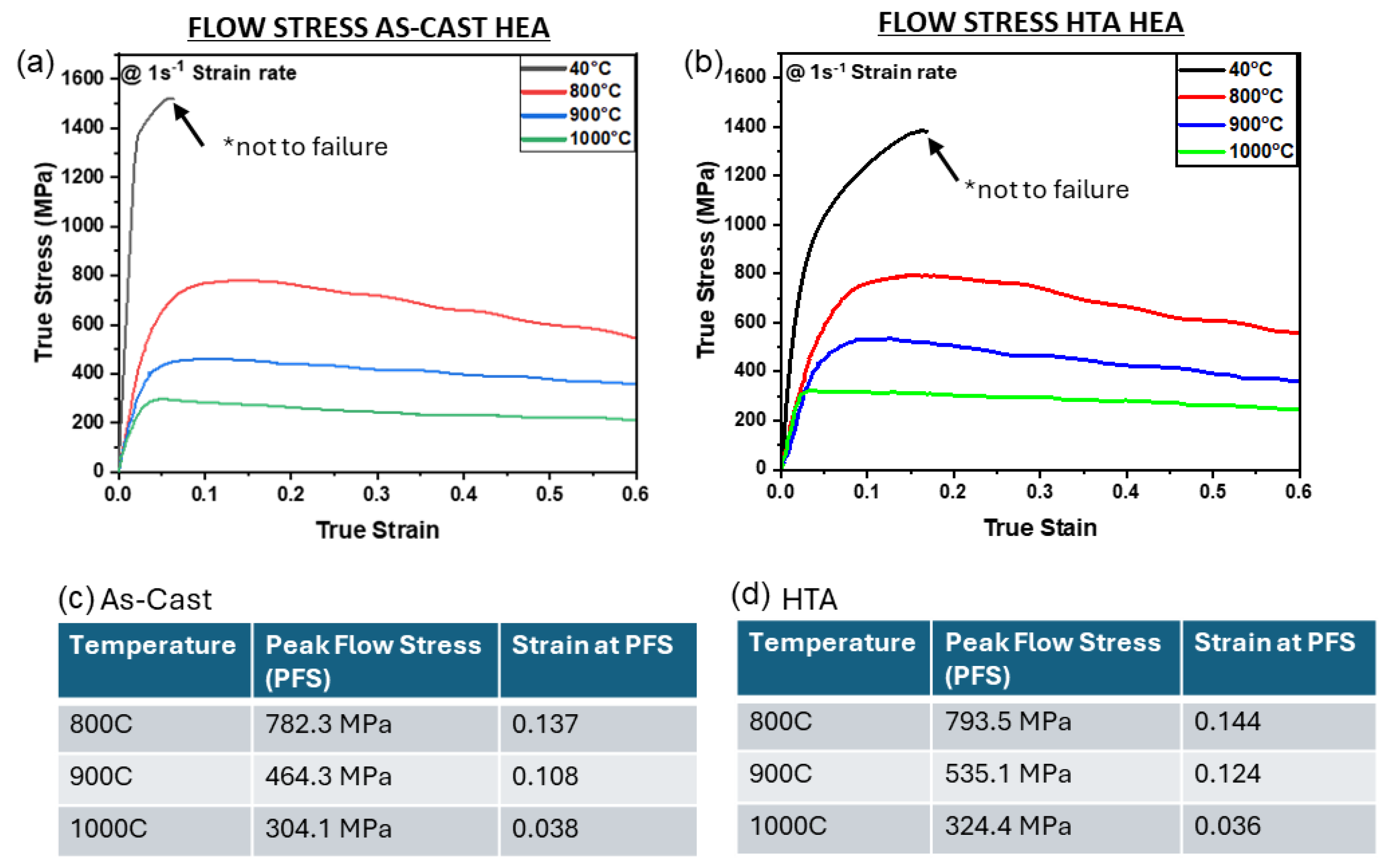

In comparing the room temperature flow behavior of the AC and HTA samples,

Figure 5, we observe that although thermal treatment is accompanied by a significant drop in initial yield strength, from 1.4 GPA for the AC to 800 MPa for the HTA, both conditions were able to sustain a significant degree of work hardening. Even though the tests were restricted by the force limit on the load cell used, this is consistent with the observed improvement in plasticity in the HTA condition noted during cold rolling (

Figure S6). Consistent to our results, the effects of globularization of lamellar domains on room temperature mechanical behavior was previously investigated in Al

0.7CoCrFeNi, where even partial transformation of the lamellar domains resulted in a marked decrease in the initial flow stress, but was accompanied by an increase in work hardenability of the alloy [

21]. The decrease in the yield strength of the annealed alloy versus the cast alloy can likely be attributed to the disordering of the FCC phase and the coarsening of the lamellar structure. The coarsened structure has a significant reduction in phase boundaries to block dislocation motion, reducing the measured yield stress, but has been shown to have an increased dislocation storage capacity as compared to the lamellar FCC, contributing to the sustained work hardening in the HTA condition [

22]. The growth of the BCC nanophase within the B2 regions also likely contributes to the observed work hardening, trapping dislocations within the harder phase.

Despite the clear differences in room temperature compression, the effects of pre-annealing on high temperature compression appear to be more subdued. Both AC and HTA specimens plastically flow near identically at 800

oC,

Figure 5a,b, with a sharp initial peak leading into an extended work hardening regime before transitioning to continuous flow softening. There is a slight increase in peak flow stress in the HTA condition, 793.5 MPa, compared to the AC condition, 782.3 MPa, and a slight increase in the strain at peak flow stress at 0.144 up from 0.137 respectively, as listed in

Figure 5c,d. The differences in flow behavior are more pronounced at 900

oC, where the HTA sample displays a prolonged work hardening region and a 15% increase in the peak flow stress over the AC at 900

oC. While the HTA sample transitions into a flow softening region with a similar slope to that observed in the 800

oC condition, the AC sample displays a brief work hardening region followed by a much shallower flow softening regime, very near to stead state. From the flow curves for the HTA and AC samples at 1000

oC, the HTA sample again demonstrates the higher peak flow stress. However, it displays no work hardening region, instead transitioning directly into a steady state deformation regime upon yielding. Although reaching a lower peak flow stress of 301.1 MPa, versus the 324.4MPa achieved in the HTA, the AC sample demonstrates a very brief initial work hardening region before entering a steady state deformation regime.

3.3. Deformation Mechanisms and Work Hardening

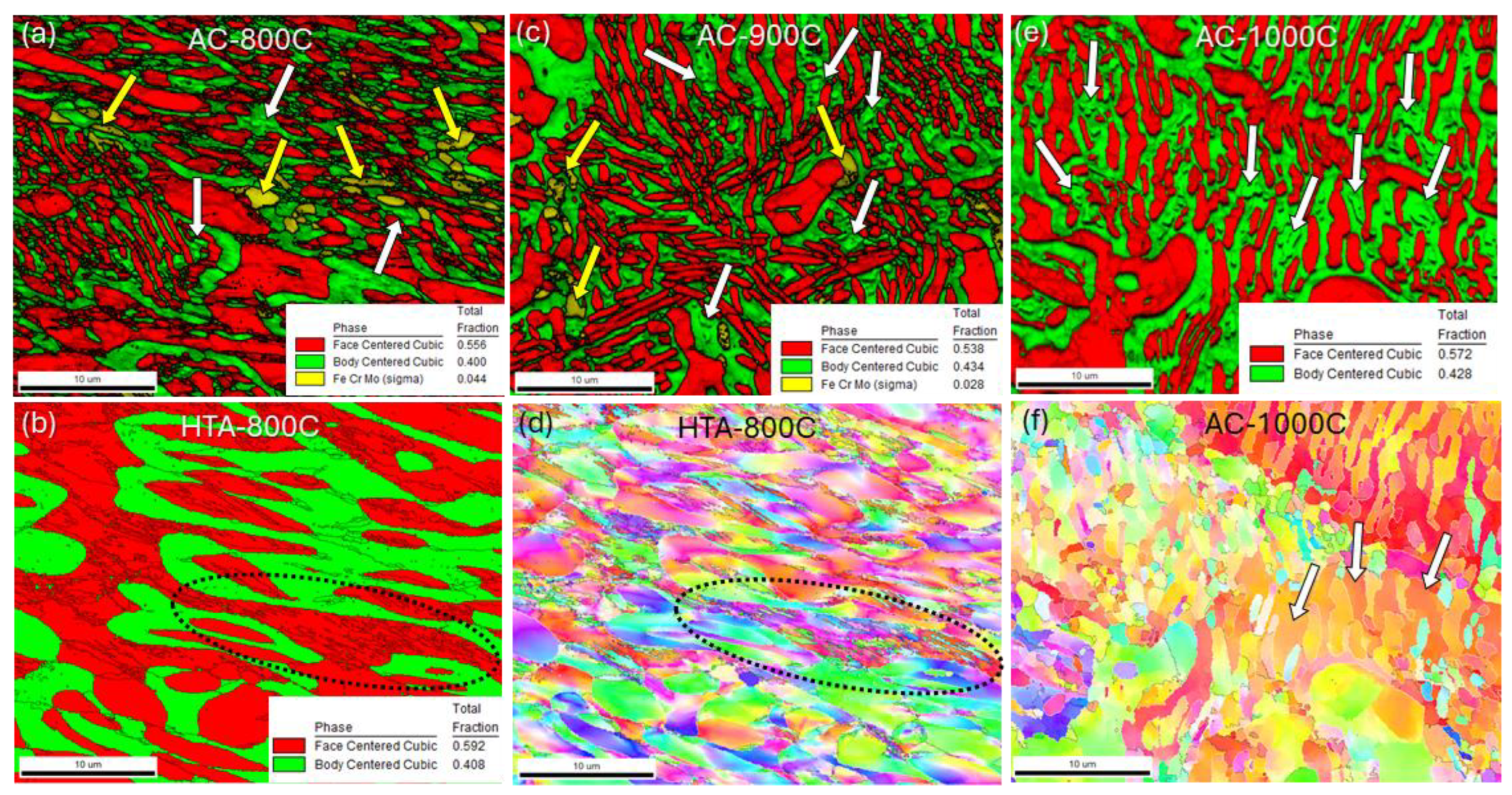

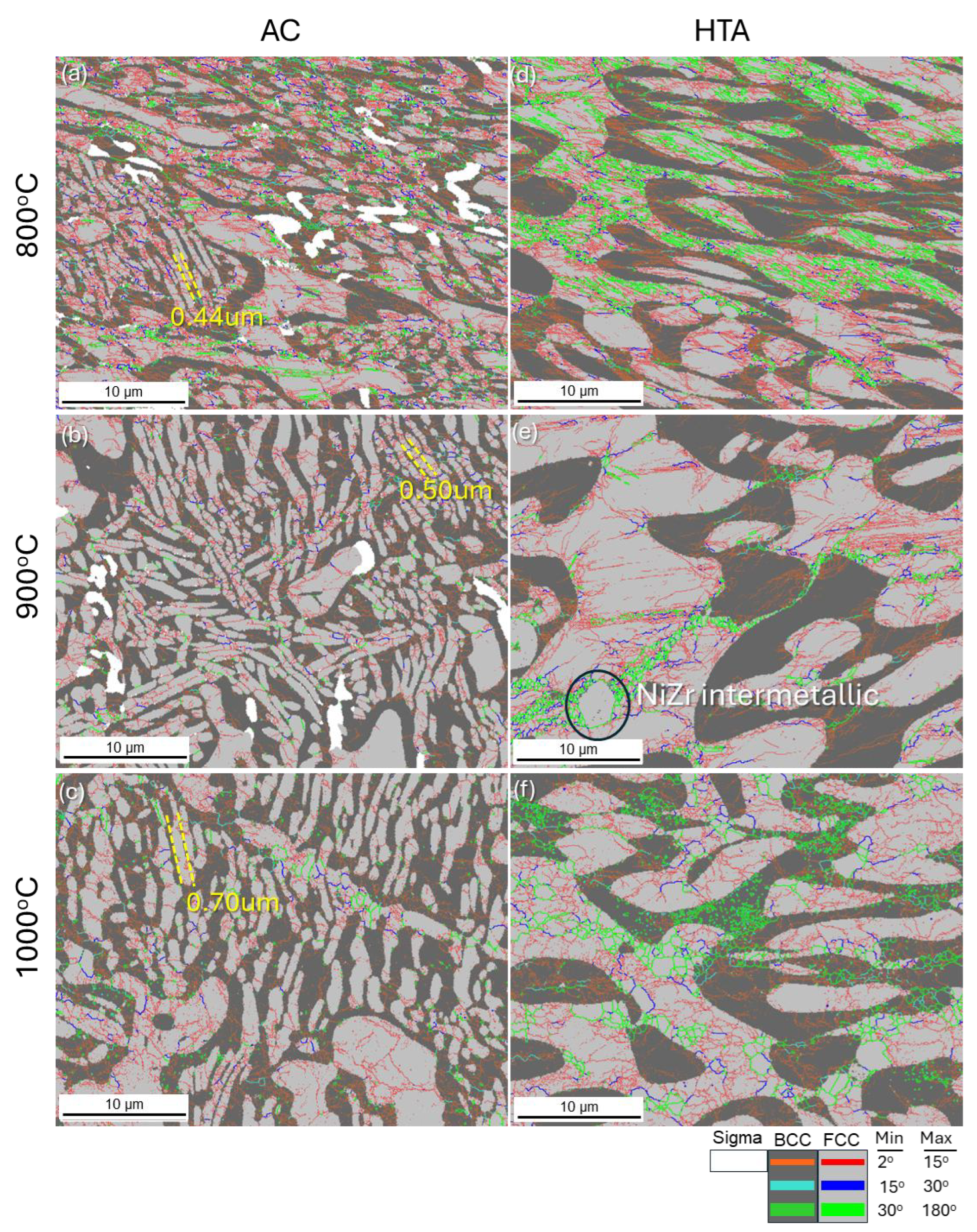

EBSD of the AC-800C, AC-900C, and AC-1000C samples,

Figure 6a,c,e, show that the lamellar morphology of the AC microstructure is retained even after high temperature compression. The phase maps show that sigma phase persists in the AC-800C and AC-900C conditions but is absent in AC-1000C. An additional BCC phase is revealed by the IQ of the maps among the lamellar regions and is shown to be coherent with the surrounding BCC,

Figure 6f. This second BCC phase was found to be α-Cr via EDS (

Figure S8). With increasing deformation temperature, the fraction of sigma phase decreases and both the number and size of α-Cr grains appear to increase. The absence of a positional relationship between the sigma and α-Cr would indicate that the shift in phase content occurs via dissolution of sigma and precipitation of BCC rather than structural transformation of sigma phase to BCC. The IPF map of the HTA-800C sample, shown in

Figure 6d, reveals the presence of high densities of deformation twins within the FCC phase, indicated within the dashed circle. The identity of these boundaries as deformation twins was confirmed in TEM, shown in

Figure 9f. The coarsening of the lamellar microstructure during annealing would reduce the twinning stress required for activation [

23]. The activation of twinning-based deformation modes in the HTA condition would account for the increased plasticity and work hardening responsible for its similar flow behavior to the AC-800C condition despite the latter having a much finer lamellar microstructure.

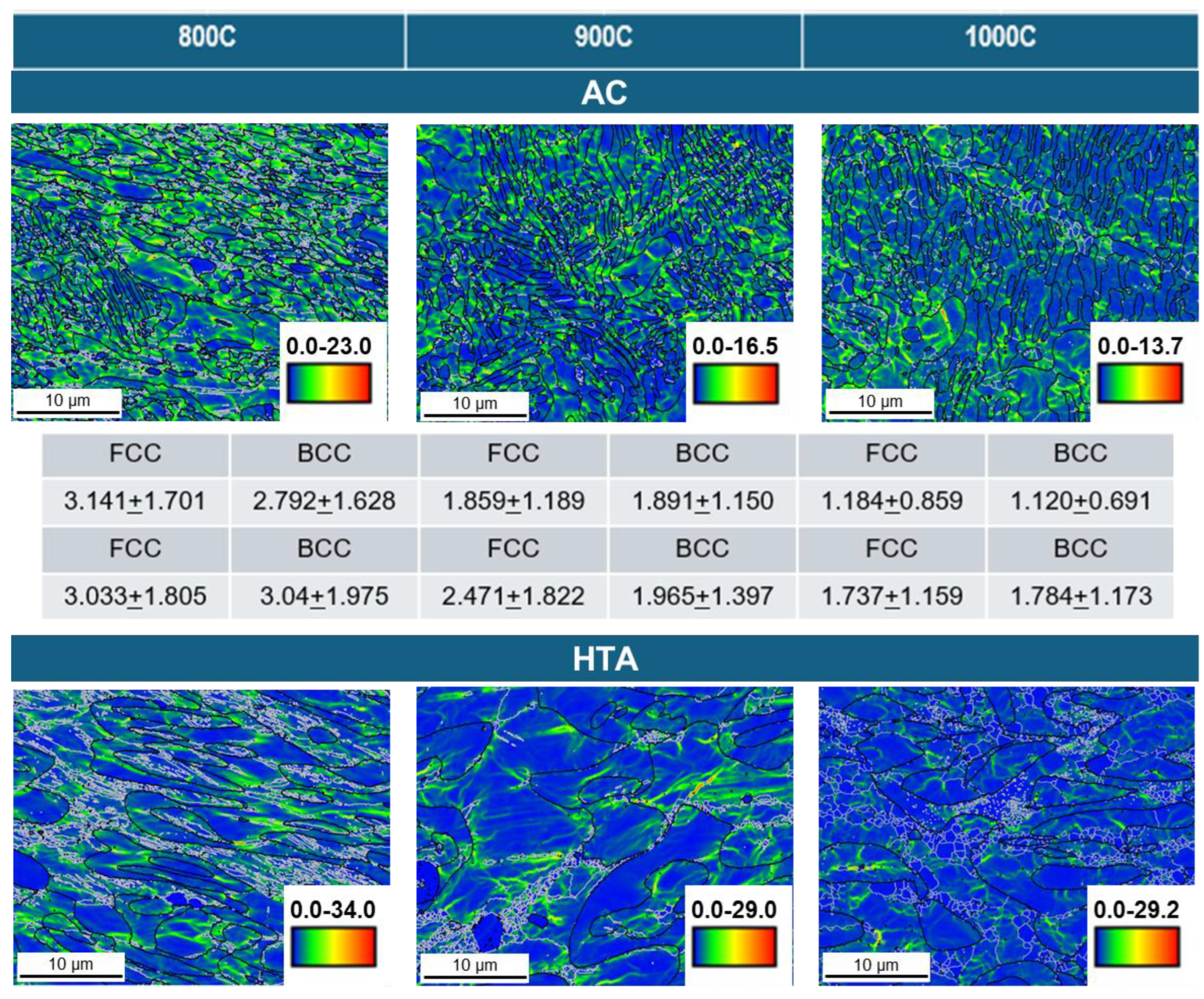

Further EBSD analysis of the high temperature deformed samples provides insights into the microstructural evolution during compression. The retained density of GNDs, as represented by the kernel average misorientation (KAM), shown in

Figure 7, is observed to decrease with increasing deformation temperature for both the AC and HTA conditions. Across all temperatures, the HTA condition was observed to have a higher average KAM than the AC, although if only considering the FCC phase, a higher average KAM is observed in the AC-800C condition compared to the HTA-800C condition. Considering the individual phase partitions, the average KAM is found to be higher in the FCC phases of the AC-800C and HTA-900C sample and is found to be roughly equivalent between the FCC and BCC phases of the remaining conditions. In both the AC-800C and HTA-900C samples, the high KAM regions are observed within the FCC phase adjacent to the phase boundaries, indicating the buildup of GNDs at the FCC-BCC interface. The presence of strain partitioning in these conditions suggests that these GNDs are accommodating the strain incompatibility of the two phases. According to the theory behind HDI strengthening, the buildup of these GNDs should induce a backstress into the FCC phase counter to the applied stress, increasing its effective strength. These factors would indicate HDI strengthening as a contributor to the observed work hardening in both the AC-800C and HTA-900C samples.

Despite the similar flow behavior observed between the two initial conditions at 800

oC, there is minimal indication of strain partitioning in the HTA sample, which would suggest that the displayed work hardening is likely dominated by the deformation twinning in the FCC phase. While the HTA-1000C condition displays roughly equivalent retained dislocation densities in the FCC and BCC phases, the presence of significantly more DRX grains, predominantly in the FCC phase, indicates that strain partitioning during the deformation still likely occurred. The heavy strain localization which accompanies the buildup of GNDs at phase boundaries associated with heterodeformation resulted in the almost immediate onset of DRX softening in the early stages of yielding. This early onset softening is responsible for the apparent lack of a work hardening regime in the HTA-1000C flow curve,

Figure 5b. In the case of the AC-900C and AC-1000C samples, the absence of obvious strain partitioning as well as minimal recrystallization indicate that the FCC and BCC phases deformed homogeneously.

Maps of the low and high angle boundaries in

Figure 8 show that the flow behavior of the AC samples is heavily dependent on the dislocation storage capacity of the lamellar regions. High gradient misorientations and small subgrain formation are visible in both the FCC and BCC phases in the AC-800C condition. The degree of substructuring, the lamellar thickness and the subgrain size all increase at 900C and again at 1000C, following the established trend of subgrain size increasing with decreasing stress. During compression, the initial lamellae are elongated, reducing in thickness with increasing strain. When the phase boundary separation is equivalent to the subgrain size, further reduction in thickness makes the grain unstable to dynamic growth, resulting in spheroidization, and limiting the dislocation storage capacity of the lamella. As the subgrain size increases with increasing deformation temperature, a lower strain is necessary to reduce the lamellar thickness to the subgrain size, resulting in a truncation of the work hardening regime and a lower stored dislocation density. The presence of lamella with both single and multi subgrain thicknesses in the AC-800C sample indicates that the critical lamellar thickness was reached near the end of compression. The absence of lamella more than one subgrain thick in the 900C and 1000C conditions indicates that the critical thickness was reached much earlier during compression. Additionally, the initial lamellar thickness appears to be smaller than the subgrain size at 1000C, resulting in the coarsening of lamella and the absence of sustained work hardening in the AC-1000C condition.

In the HTA samples, the flow behavior is significantly more dependent on the co-deformation behavior of the FCC and BCC phases. At 800

oC,

Figure 8d, fine scale recrystallized grains can be observed along the twin boundaries as well as the phase boundaries in the FCC. The BCC appears less recovered, with large retained misorientation gradients.

At 900

oC,

Figure 8e, in the absence of the high twinning density, dislocations stored in the FCC primarily occupy subgrain boundaries adjacent to phase boundaries, with a highly recrystallized shear band forming to either side of a coarse Ni-Zr rich intermetallic. The BCC structure is less severely deformed, with much of the stored defect density found in localized substructures adjacent to the phase boundaries, further indicating the role of HDI strengthening in the sustained work hardening observed in HTA-900C condition.

The FCC phase has fully polygonised at 1000

oC,

Figure 8f, with a number of high angle grains similar in size to the subgrain structure. The BCC phase displays similar recovery of the subgrain structure, with populations of small grains appearing along phase boundaries. These undeformed grains likely formed through discontinuous nucleation as they’re significantly smaller than the subgrain structure.

S/TEM analysis of the AC and HTA conditions deformed at 800

oC confirm the primary modes of plasticity accommodation to be dislocation mediated and mixed deformation twinning and dislocation mediated respectively. The dislocations are primarily localized to the FCC phase in the AC-800C condition, forming dislocation walls in the lamellar regions and full dislocation cells in the coarse extracellular FCC. Deformation nanotwins are visible in the FCC phase of the HTA-800C condition, with little evidence of polytwinning or cross slip. Recrystallized grains have formed along phase boundaries and in areas of high twin boundary density. A number of fine scale Cr rich grains are observed in the recrystallized regions, seen in

Figure 9e. Dislocation buildup along phase boundaries is present in both samples, contributing to the observed work hardening. Both samples possess FCC+B2 microstructures, the additional superlattice reflections from the L1

2 and L2

1 ordering observed in the base AC condition absent in the post deformed samples. This change in ordering likely occurred during the initial heating and therefore had little effect on the observed deformation behavior.

Figure 9.

STEM-HAADF and STEM EDS of the AC-800C and HTA-800C samples. SAED from the twinned region of the HTA-800C-1/s sample is included as an inset.

Figure 9.

STEM-HAADF and STEM EDS of the AC-800C and HTA-800C samples. SAED from the twinned region of the HTA-800C-1/s sample is included as an inset.

The Cr-rich spinodal BCC phase is absent in B2 regions adjacent to sigma grains in the AC sample, shown in

Figure 9b. From

Figure 6a,c,e, the observed coarsening and size uniformity of the sigma and α-Cr grains after deformation at elevated temperature implies that the phase growth is favored over further nucleation of these phases at the testing temperatures. This growth appears to be driven by the diffusion of Cr from the surrounding B2 phase at the expense of the spinodal nanophase. The presence of these coarse Cr rich phases suggests that the spinodal nanophase is absent in the lamellar regions of all deformed AC samples.

The presence of the spinodal nanophase in the base HTA sample without discernable sigma or α-Cr indicates that the separation likely formed during quenching. During the annealing of the HTA samples, the sigma phase, coarse α-Cr, and spinodal phase found in the cast structure dissolve. Since the Cr-NiAl spinodal separation has previously been reported during the rapid cooling of HEAs, it is likely that the Cr rich BCC nanophase reformed during the quenching after annealing [

24]. The elimination of sigma and α-Cr nuclei introduces an incubation period into Cr separation via nucleation and growth, during which separation by spinodal decomposition is kinetically favored due to the inherently low activation energy needed. As the spinodal decomposition progresses, the associated reduction in the Cr supersaturation of the B2 phase further reduces the driving force for sigma and α-Cr nucleation, extending the stability of the spinodal nanophase at higher temperatures by preventing ripening.

The formation of the spinodal nanophase in the B2 phase has been shown to both improve its initial strength and work hardenability [

7]. Despite the absence of the spinodal nanophase in the AC-800C condition, the intrinsic strength of the B2 appears to have been sufficient to achieve the strain incompatibility required for HDI strengthening, as evidenced by the strain partitioning shown in

Figure 7 and the sustained work hardening regime observed in

Figure 5. At 900

oC and 1000

oC, the thermal reduction in the strength of the unreinforced B2 phase appears to have been sufficient for homogeneous deformation of the FCC and BCC phases to occur, as evidenced by the lack of strain partitioning. The presence of the spinodal nanophase in the HTA-900C and HTA-1000C samples extends the strength of the B2 phase to higher temperatures, maintaining the strain incompatibility with the FCC and the resulting strain partitioning. At 900

oC, this results in the greater sustained work hardening and higher peak flow stress of the HTA sample as compared to the AC as a result of the difference in heterodeformation behavior. At 1000

oC, the increased strength of the B2 in the HTA sample and accompanying strain partitioning results in a severe strain localization within the FCC which at the elevated temperature causes an almost immediate activation of DRX softening upon plastic yielding. The more homogeneous deformation observed in the AC-1000C sample experienced less strain localization, and therefore possessed a small discernable work hardening regime, despite its lower peak flow stress as compared to HTA-1000C.

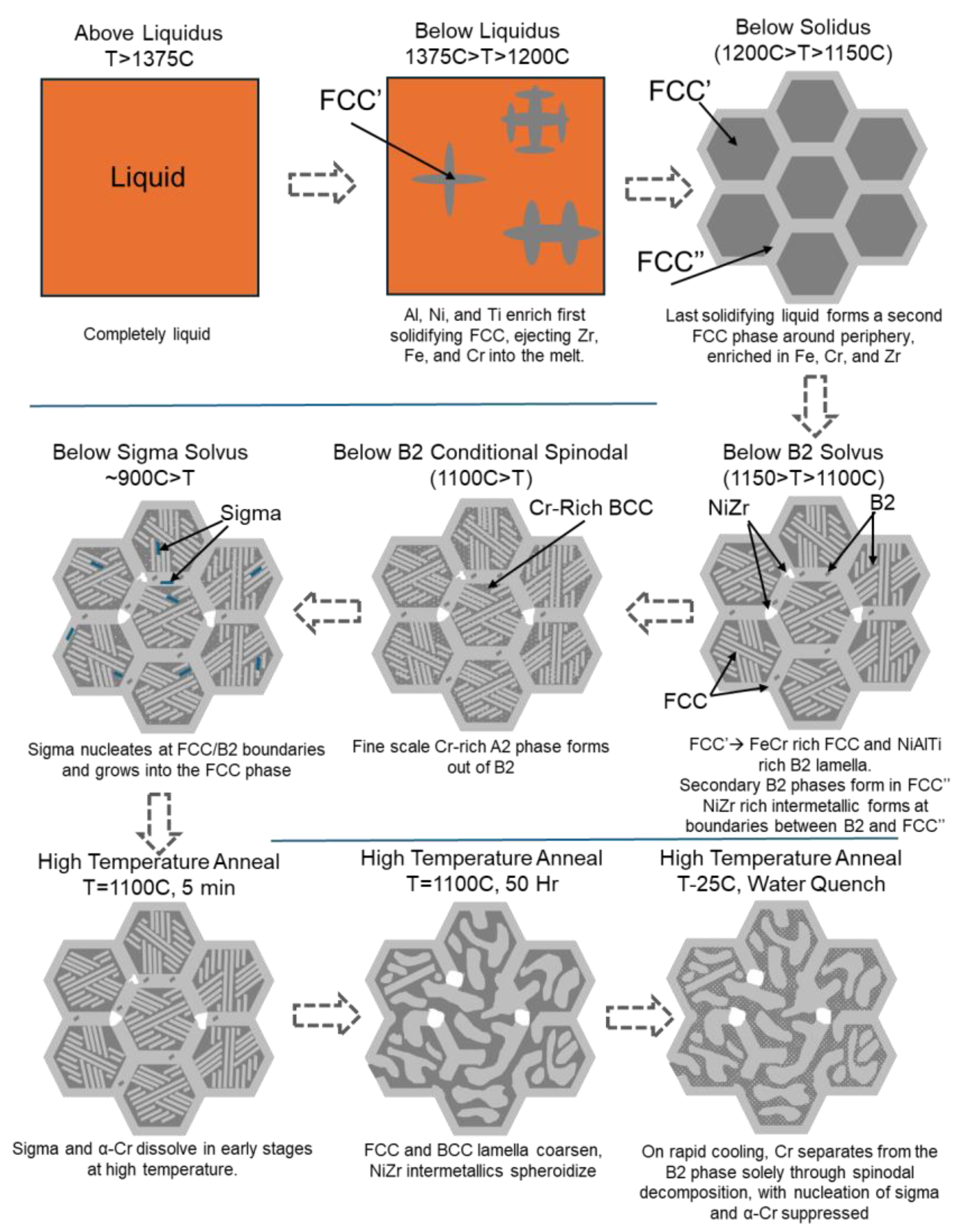

From the previous observations, we propose the solidification and processing pathway shown in

Figure 10. Moving below the liquidus line around 1375

oC, a primary FCC phase enriched in Ni, Al and Ti, dubbed FCC’, forms from the melt, ejecting Zr and minor amounts of Fe and Cr into the liquid. By 1200

oC, the melt has fully solidified into a completely FCC structure, with two distinct compositions; a cellular structure with FCC’ surrounded by a second Fe, Cr, and Zr enriched FCC, dubbed FCC’’, which formed from the last solidifying liquid. Moving below the B2 solvus at 1150

oC, the FCC’ phase decomposes into lamellar structures of FeCrCo rich FCC and AlNiTi rich B2 phases. Small secondary B2 phases form within the coarser boundary FCC’’ and NiZr intermetallics form at the boundaries of the Zr-enriched FCC’’ and the newly formed Ni-rich B2 phase. After the formation of B2 and the NiZr intermetallics, the composition of the remaining boundary FCC and lamellar FCC regions are roughly equivalent. Cooling below some temperature between 1100

oC and 1000

oC, the B2 phase enters a conditional miscibility gap, and begins to form a fine scale Cr-rich BCC phase via spinodal decomposition. Further cooling below ~950

oC, FeCr rich Sigma phase begins to form along the FCC-B2 boundaries, growing by the diffusion of Cr from the supersaturated B2 phase into the FeCr rich FCC. This accounts for the vast majority of the microstructure observed in the As-Cast sample. Raising this structure to 1100

oC, the sample is above the solvus lines for both sigma and BCC-Cr, resulting in the dissolution of Cr back into the B2 phase during the early stages of heating. The remaining FCC+B2+NiZr microstructure proceeds to coarsen significantly over the following 50 hours, driven primarily by the shape instability of the fine lamellar phases which formed from FCC’. Upon quenching in water, the sample moves rapidly through the Cr miscibility gap in the B2 phase, which is still able to separate via spinodal decomposition due to the relatively low activation barrier. The nucleation of coarse Cr-rich phases such as sigma and α-Cr are suppressed completely.

The liquidus, solidus and B2 solvus temperatures can all be pulled directly from DSC, shown in

Figure 2. High temperature XRD, also shown in

Figure 2, confirms that only FCC phases are present at 1200

oC, below the solidus line. Comparison of the nominal compositions of the boundary FCC phase with the lamellar regions indicates solute partitioning of Al, Ni, Ti and Zr during solidification and the formation of two separate FCC phases from the melt. The spinodal temperature was determined from the coarse α-Cr grains observed in the As-Cast samples. The α-Cr was observed in AC-1000C,

Figure 6, but not in the HTA condition,

Figure 3, and therefore must become unstable between 1000

oC and 1100

oC. Since the spinodal temperature is always less than or equal to the solvus temperature of the bounding phases, the stability of the spinodal phase should also fall somewhere between 1000

oC and 1100

oC. The temperature for sigma formation was pulled from CALPHAD, shown in

Figure 1, and is supported by the phases observed in the high temperature deformed AC samples, shown in

Figure 6. Evidence for the evolution during high temperature annealing was included in the discussions of

Figure 3,

Figure 6 and

Figure 9.

To summarize, the initial annealing of the HTA condition produces notable changes in the high temperature deformation mechanisms of the dual-phase HEA over the AC condition. The AC and HTA samples display very similar flow curves at 800C, with dislocation buildup at phase boundaries and HDI hardening caused by the mixture of soft FCC and hard B2 contributing to the high peak flow stresses and work hardening observed in both cases. The lower contribution of phase boundaries to the coarse grained HTA condition is offset by the activation of deformation twinning in the FCC phase, providing additional plasticity and barriers to dislocation motion, resulting in its similar performance to AC-800C.

Work hardenability of the AC conditions additionally depends on the ratio of lamellar thickness to subgrain size, with the increased subgrain size at higher temperatures lowering the critical strain at which the lamella can no longer store additional dislocations. The persistence and growth of coarse sigma and α-Cr in the AC samples depletes the NiAl B2 phase of Cr at the expense of the spinodal nanoprecipitates and their contribution to strengthening and work hardening of the B2 phase. Sigma and α-Cr nuclei formed during solidification are eliminated by high temperature annealing, and cannot form during the subsequent quenching.

The lower activation energy of the spinodal separation results in the decomposition of the B2 and the formation of the spinodal nanophase despite the rapid cooling. When the samples are heated, the progression of the spinodal decomposition decreases the driving force for nucleation of sigma and α-Cr, further increasing the stability of the nanoprecipitates. The spinodal dispersion persists in the HTA samples, increasing the strength of the B2 phase and maintaining the property balance for heterodeformation of the two phases at higher temperatures. The combined observations of enhanced work hardening and strain partitioning to the FCC phase seen in the HTA-900C condition indicate the role of HDI strengthening in its improved performance over the AC-900C condition, which displayed more uniform deformation behavior. This is likely indicative that the absence of the spinodal nanoprecipitates reduces the difference in the mechanical strengths of the FCC and B2 phases resulting in more homogeneous deformation. The limited formation of GNDs and the resulting back stresses reduces the observed sustained work hardening. For the AC-1000C and HTA-1000C conditions, these same influences are seen, but with different effects on the overall observed work hardening. The absence of strain localization in the AC-1000C condition delays activation of softening by DRX, resulting in the presence of a small work hardening regime arising from the large number of retained phase boundaries in the lamellar structure. In contrast, the increased hardness of the B2 phase in the HTA-1000C condition produces a notable increase in peak flow stress but also results in the almost immediate activation of DRX softening upon yielding due to the high strain localization to the phase boundaries in the FCC phase.