1. Introduction

Ruth Mateus-Berr and Ille C. Gebeshuber initiated an interdisciplinary workshop hosted at the University of Applied Arts Vienna. This workshop served as a platform for participants to engage in discussions centred around integrating art and science within an undergraduate curriculum with a specific emphasis on biomimetics and sustainability. Collaboratively, Richard W. van Nieuwenhoven and Matthias Gabl curated a course syllabus aimed at guiding undergraduate students aged 11 to 12 in the creation of an artwork utilizing Engineered Living Materials (ELMs). Given the well-established research foundation and the renowned living component, mycelium-based ELMS emerged as the logical choice for this endeavour [

1].

In recent years, there has been a remarkable surge in the exploration and application of mycelium materials, particularly in packaging and construction [

2]. This growing interest signifies a notable shift towards harnessing the potential of ELMs as viable alternatives in various industries [

1]. While the prevalent practice involves subjecting the mycelium to heat treatment during the post-growth phase to deactivate its biological activity, the accessibility of mycelium production methodologies has democratised its usage. Indeed, the emergence of do-it-yourself (DIY) kits [

3], made available by various companies, has facilitated widespread experimentation and innovation in this visionary field. Central to the appeal of mycelium-based ELMs is their inherent sustainability [

4], which resonates deeply with the ethos of contemporary environmental commitment [

5]. Mycelium offers a renewable and biodegradable alternative, unlike traditional materials derived from finite resources. Utilising local resources for the materials locally and producing them on-site further bolsters their eco-credentials, contributing to the promotion of circular economy principles [

6]. Moreover, mycelium-based materials exhibit remarkable versatility in their application. A combination of moulding, casting and shaping techniques can be tailored to meet a diverse range of functional and aesthetic requirements. This adaptability opens up various possibilities across industries, from customisable packaging solutions to structurally sound architectural elements [

7,

8]. Beyond their practical utility, mycelium materials are a potent educational tool, offering a multifaceted learning experience that transcends traditional disciplinary boundaries. The convergence of scientific principles, sustainable practices and artistic expression presents a unique opportunity for interdisciplinary engagement, especially among young learners, by integrating biology, material science, sustainability and craftsmanship concepts into educational initiatives centred around mycelium materials, fostering a holistic understanding of complex scientific concepts while nurturing creativity and critical thinking skills [

9]. Considering the compelling attributes elucidated, this article endeavours to provide educators with a comprehensive framework delineating practical methodologies for incorporating diverse facets into undergraduate science education, aiming to stimulate and sustain students’ interest and motivation to actively engage in science-based curricula.

Interdisciplinarity “has been linked with attempts to expose the dangers of fragmentation” in a century where knowledge in science doubles every two years, it should uncover and develop connections between disciplines, “re-establish old connections”, and create innovative solutions [

10]. Klein argues that the basic structure of interdisciplinarity was, since its beginning, an “inseparable implication of disciplinary thought” [

11, 20]. In her opinion [

10, 188], an interdisciplinary approach is a process for achieving an integrative synthesis, “a process that usually begins with a problem, question, topic or issue.” The essential part is problem-solving through transgressing disciplinary language and worldview. Klein [

10, 188-189], described steps: defining, determining, developing, specifying, engaging, gathering, resolving, building and maintaining, collating, integrating, confirming or disconfirming, and deciding are similar to the steps of Design Thinking methodology, which are supplemented by teamwork [

12].

Design thinking is seen as an essential way to cultivate 21st-century skills, according to 8 Li and Zhan [

13, 8], who conducted a meta-study of the application of design thinking (43 SSCI peer-reviewed journal papers with 44 studies) in the school context. They note that the need and interest in introducing primary and secondary schools to design thinking has increased by almost 30 per cent since 2017. For the most part, the method is used for STEM in the younger grades. Interestingly, this method was hardly used in subjects such as technology and design, but rather in science and engineering. Art and design education must re-claim the methodology.

2. Materials and Methods

As the provided study also should foster 3D visualisation, the decision was made to make all participants’ workpieces fit each other. For this, a solution was found to use building blocks of 4x4x4 cm3 as a basis.

2.1. Design of the Flat Form

Participants must design a flat form (FF) constructed from 4 basic blocks (BB). Mathematically, there are just three possible forms; this is utilised in the first class session to illustrate that many of the individual forms are, in reality, equal to each other after spacial rearrangement (

Figure 1)(

Figure 2). This first class session also teaches the participants to think in the third dimension and express these thoughts on paper as a drawing.

A personalized marking is included in the design to identify each individual FF in the shared structure built at the course’s end.

2.2. Construction of the Flat Form

The second task for the participants was to realise the designed form in clay. In this class, the teacher instructs the participants on the clay-forming methods so that the proportions are according to the design. The personalized markings are added using a scraper on top of the structure. Because the different FFs are interconnected later in the course, the teacher has to verify the proportions of every participant.

During this phase, the teacher already tells the students that the structures shall be combined later so the participants can think about the different possibilities of connecting the individual pieces.

2.3. Construction of the Negative Flat Form

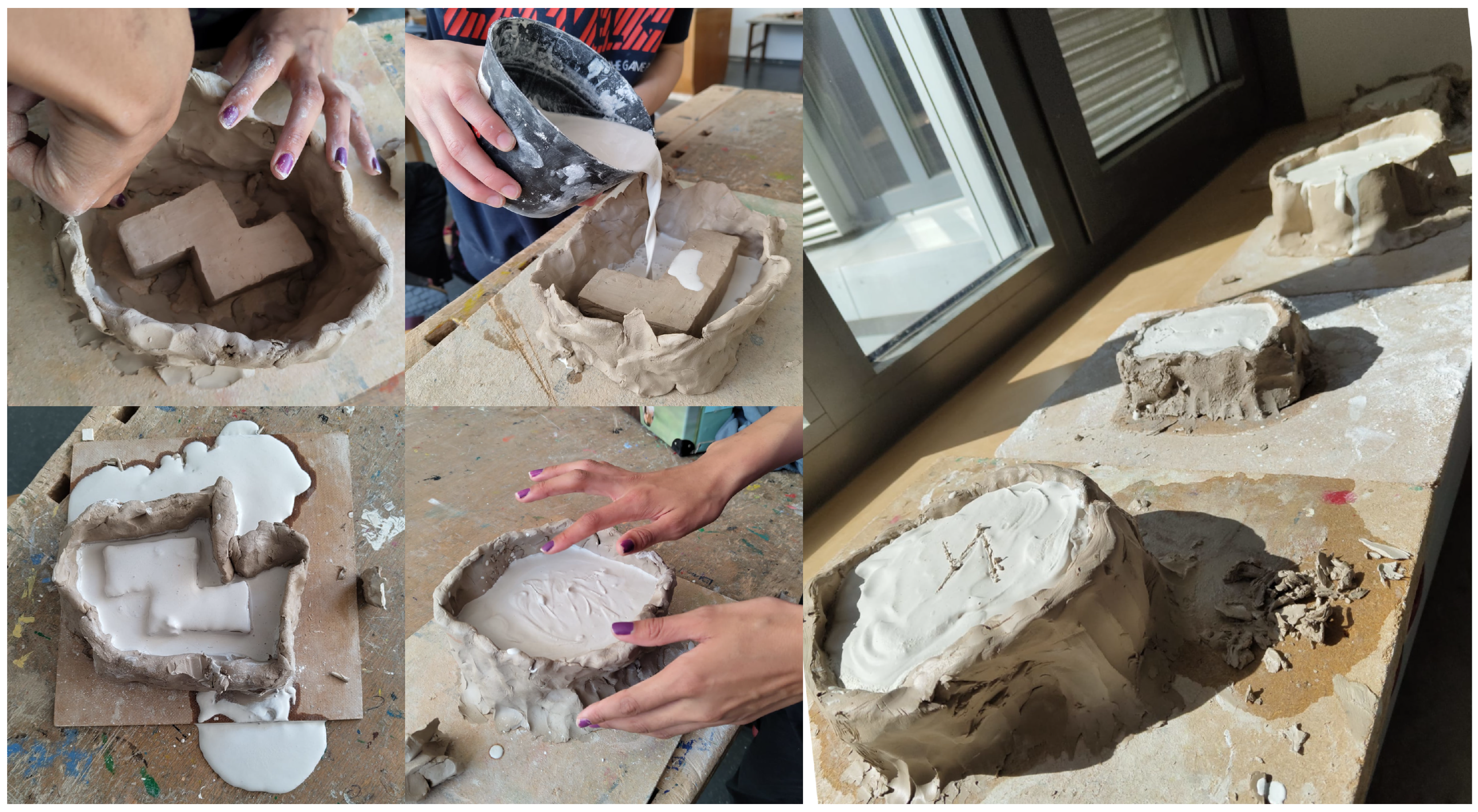

The third task is to create a negative of the constructed clay form. This is done by utilising casting plaster. By forming a clay wall around the FF of around 5 cm height, space is created for casing plaster. To reduce the plaster needed for casting, the space between the clay wall and the clay structure should be around 1 cm wide (

Figure 3).

The participants need to collect the right paster ingredients and mix them appropriately. The cast-ready plaster is then poured into the prepared clay form. Depending on the product used, this cast must dry according to the plaster specifications (

Figure 3). In this study, we utilised PUFAS Modellgips (PUFAS, Leipzig, Germany) and needed a resting period of at least one day.

2.4. Mycelium Flat Form

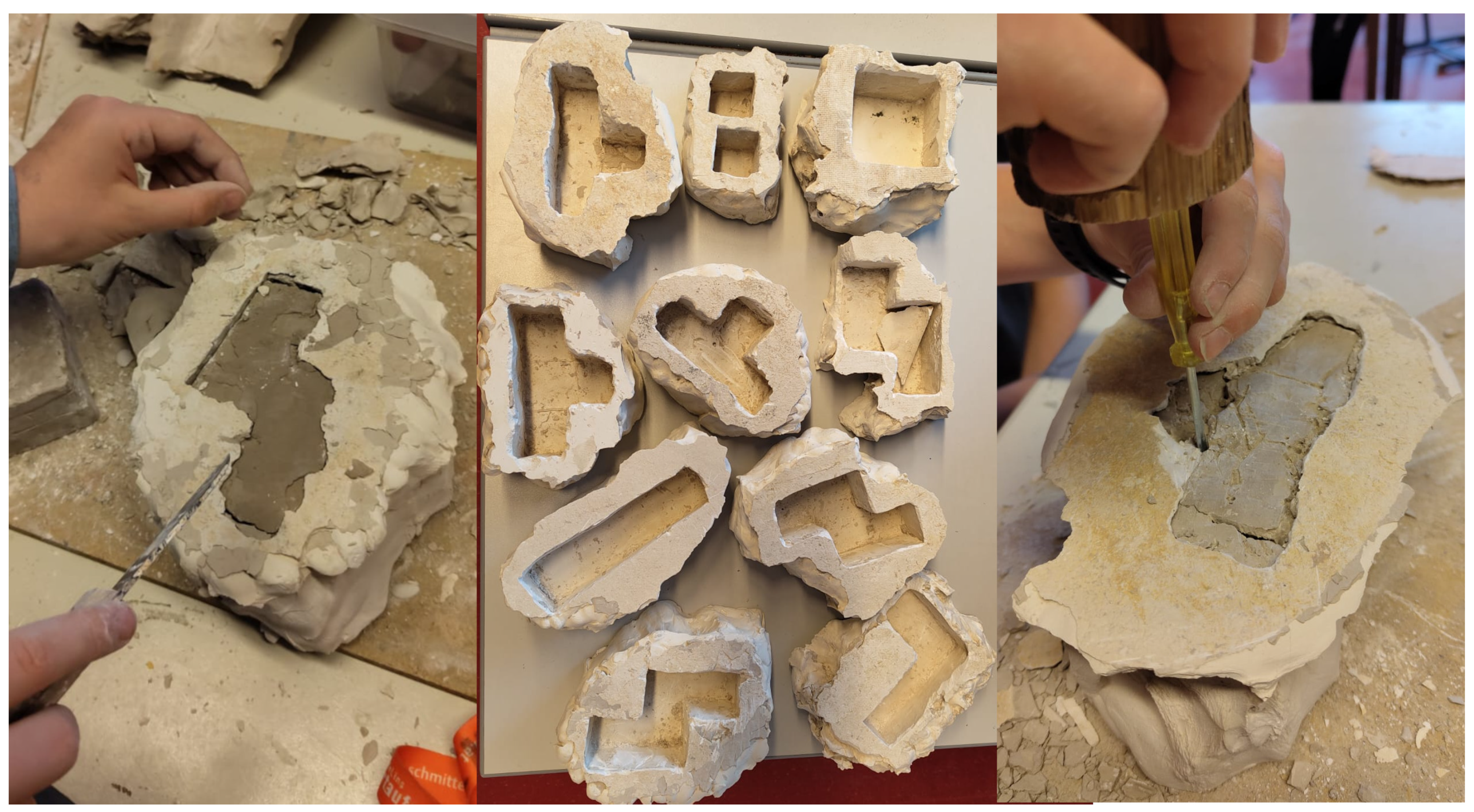

The fourth task starts with carefully separating the FF from the negative plaster form (

Figure 4). After cleaning the FF, the mycelium DIY is needed; it is best to contact the company in person to synchronise the arrival of the DIY with the start of this phase in the class. Because the mycelium is very sensitive to bacterial infections, it must be handled as sterile as possible. Consequently, lab gloves and masks were a requirement for all participants. The sterile handling of the materials also adds extra suspense to the procedure, which helps to keep the participants interested. The gloves and the FF must be sterilised, which is done with 70% isopropanol. The teacher hands out the isopropanol and the disinfection process is done in front of the teacher to keep the participants from misusing it. Instructions are given not to touch anything that is not sterilised.

The sterile gear provided is a teaspoon, a small container for the flower, a container for the mycelium-impregnated wood spans, two cling film pieces of at least 20x20 cm2, and two toothpicks. The participants collect 2 grams of flower and around 70 grams of mycelium-impregnated wood spans with these utensils.

Back at their workplaces, the participants first carefully (by not touching the FF with the gloves as the FF is likely not fully sterile) fill the plaster form with the cling film. The flower and the mycelium-impregnated wood spans are then well-mixed in the mycelium container. So much of the mixture is now cast into the FF that it is filled, and every cm layer is pressed with glove-covered fingers into the edges of the form. The teacher prepares a sample for the best results so the participants can see the procedure before practising it. As the FF is filled to the top, it is covered with the second cling film perforated every 3 cm using toothpicks.

2.5. Incubation

The filled FF of all participants are then placed together at a place to incubate for five days, whereas seven should also be possible, but that would probably terminate the growth phase and would not allow for the merged growth of the shared structure. The ideal temperature for incubation is 24 degrees, depending on the DIY utilised.

The incubation place is best selected for minimal interaction as the mycelium is very sensitive during the initial growth. Nevertheless, for regular checking of the participants, the incubation place should be visible, for example, in a small glass house (

Figure 5.

2.6. Shared Mycelium Construction

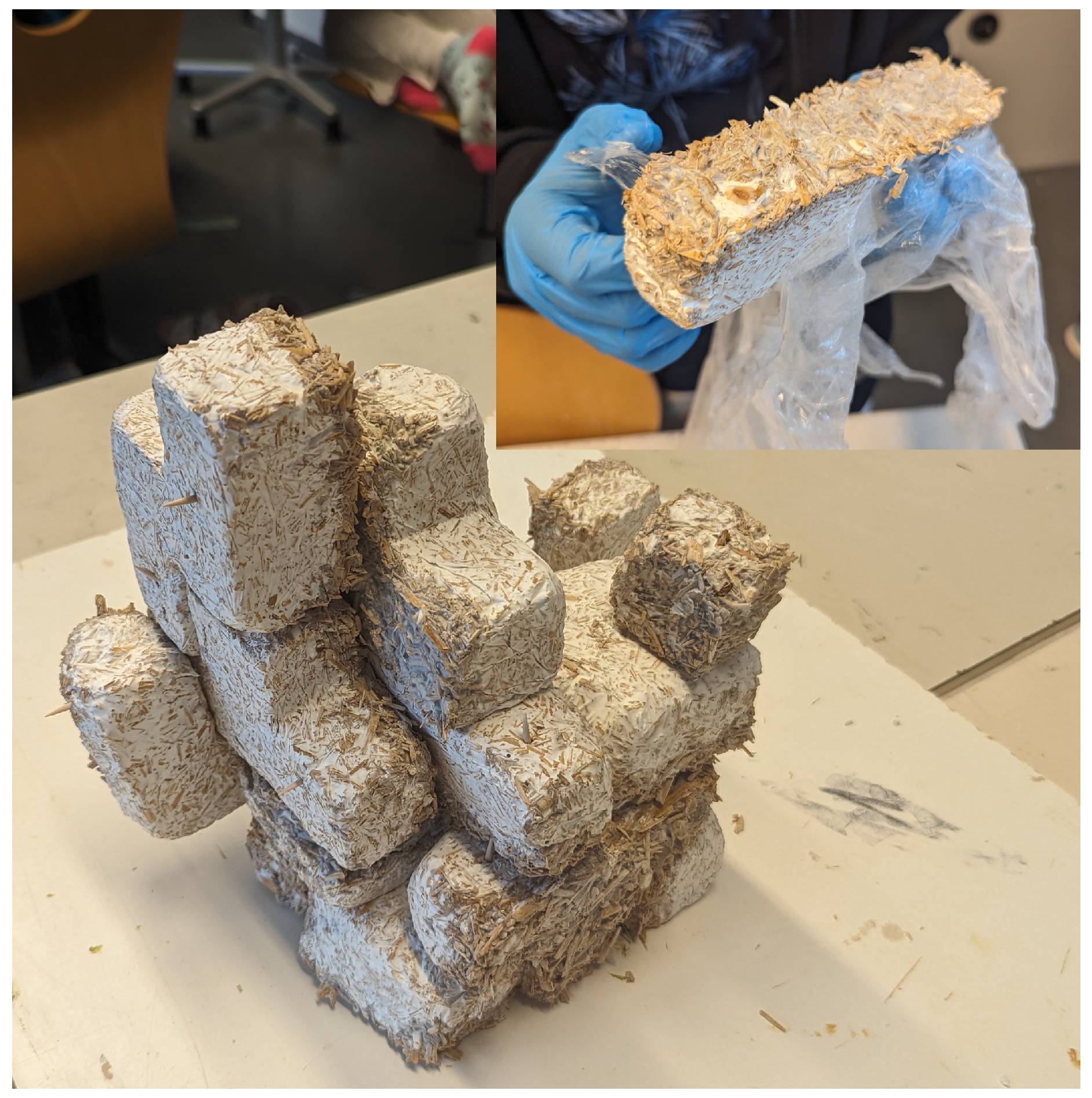

After five days, the mycelium should be grown to cover the wood spans with a whitish-like texture (

Figure 6). The cling film allows easy extraction from the FF. During extraction, the participants must decide on the three-dimensional shared form built from the individual bricks. Again, gloves with disinfection procedures are used. Disinfected toothpicks are utilised to connect the mycelium forms. One week of additional incubation at the same incubation place allows the material to grow together. Note that this only happens sometimes and strongly depends on many individual parameters.

2.7. Decomposion Process

The last step of this course is the exposure of the structure to a natural environment to view the decomposition of the material and its integration back into Nature. It is recommended to visit the place of last year’s course with the participants of the following year to view the progress of the decomposition.

2.8. Educational Objectives and Competencies

The objectives and competencies align with the curriculum guidelines for "Technology and Design" and "Art and Design" set by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education for general secondary schools (Lehrpläne – allgemeinbildende höhere Schulen des Bildungsministerium für Bildung für die Unterrichtsfächer, Bundesministerium für Bildung 2023 [

14].

Children who learn to model three-dimensionally acquire diverse competencies and skills encompassing cognitive, motor and socio-emotional domains.

2.8.1. Fine Motor Skills

Learning to model in three dimensions fosters children’s fine motor skills development. This skill development is evident as they manipulate clay, modelling compounds and building blocks. Over time, their precision in movements and attention to detail improves significantly.

2.8.2. Creativity and Experimentation

Children who engage in different modelling techniques develop a sense of creativity and an eagerness to experiment. They explore how different forces, shapes and movements affect the material, encouraging a hands-on approach to learning and discovery.

2.8.3. Focus and Concentration

Modelling activities help children enhance their focus and concentration. The immersive nature of these activities allows them to maintain attention for extended periods, fostering deep engagement and sustained mental effort.

2.8.4. Spatial Thinking

By engaging in three-dimensional modelling, children develop spatial thinking. They start to understand the relationships between different parts of a model and how these parts are arranged in space, which is crucial for grasping complex spatial concepts.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Drawing and First Clay Modeling

During the introductory session, initial scepticism regarding the prospect of working with fungi was noted among the students. The session commenced with a query regarding familiarity with the classic computer game Tetris, revealing varying levels of prior exposure. However, students quickly grasped the concept of constructing Tetris blocks as a limited set of shapes. Each student then proceeded to individually draft a scaled 3-dimensional sketch of a selected Tetris block shape on a 1:1 scale with dimensions of 4 cm per edge. This task progressed more swiftly than anticipated due to prior experience with three-dimensional drawings from mathematics classes. Excitement mounted as students eagerly queued to collect clay to form their positive moulds, yet challenges emerged as they endeavoured to replicate their selected Tetris block shapes precisely. Strategies varied, from assembling individual cubes to moulding complete forms to be gradually reconfigured into the desired Tetris block shape. Guidance was provided to facilitate the clay-forming process, emphasizing the need for dimensionally accurate positives that do not interlock with their negatives to ensure ease of separation without damage. Despite considerable progress, achieving precise dimensions (4 cm side length) proved elusive within the allocated time, as we expected, necessitating further refinement in subsequent sessions (

Figure 1).

Anticipated challenges include maintaining student engagement during the meticulous shaping process. Each student marked their work for identification before the blocks were collectively gathered, revealing the potential for assembly (as in the Tetris computer game) and the need for further refinement to achieve uniformity. Blocks were prepared for preservation until the next session by sprinkling them with water and wrapping them in cling film. The workshop underscored the diverse skill sets required and the varied approaches students employ to tackle sub-tasks. All students achieved a comparable level of progress by the end of the session. Individual responsibility for workshop cleanup during the concluding minutes was especially stressed.

3.2. Finalising the Clay Modeling

The second day of the course, scheduled a week later, posed more significant challenges as the focus shifted towards enhancing endurance among the students. The objective was to refine the dimensions of the clay Tetris blocks to precisely 4 cm squares. Incorporating three students absent from illness the previous week added complexity, necessitating their catch-up to align with their peers’ progress. Over the two-hour duration, the students’ motivation gradually declined, varying among individuals. As the students approached the target dimensions, some began to assert that their efforts were satisfactory despite the clay base length exceeding the required measurement by over a centimetre. One student, previously recognized for exceptional aptitude in other classes, encountered difficulty achieving precise dimensions, attempting to mask this challenge with a dismissive attitude: "I do not care too much." Conversely, one of the students recovering from illness displayed remarkable engagement, visibly striving to outperform her peers. This heightened engagement could be attributed to her desire to integrate into the leading girl group within the class, having previously experienced discrimination. Half of the students reached a plateau approximately halfway through the session, decreasing further progress. During the final hour, the teachers provided physical assistance to two-thirds of the students to achieve the required precision. A recurring challenge was the thickness of the Tetris blocks, with instances of being either excessively thin or excessively thick. Ultimately, the result was deemed satisfactory, as all Tetris blocks met the predetermined diameter criteria (with the requirement of 0.5 cm left unmentioned). To foster group cohesion, teachers created two cubes with a base length of 4 cm each, and students shall integrate these cubes into their project at the course’s conclusion.

The process of collecting and storing the Tetris blocks prompted individuals to spontaneously engage in piecing them together, despite the absence of any requirement to do so (

Figure 2). The cleanup process proceeded smoothly, with students demonstrating a willingness to participate despite the need to correct behaviour from two students previously identified as problematic. Notably, these problematic students were among the first to adopt the "good enough" mentality previously observed.

3.3. Casting the Negative

The moulding process commenced with constructing a water-tight clay wall around the clay structure, facilitating the pouring of gypsum (gibs) around the structure. Ensuring a minimum of one centimetre of gypsum above the structure was imperative to construct a closed mould. The procedure was demonstrated using pre-prepared square clay structures by the instructors, with gypsum prepared by thoroughly mixing two parts of water with one part of gypsum. The novelty of gypsum casting elicited excitement among the students, particularly the male cohort, who became eager to progress to the pouring stage. The initiated working speed caused incomplete and leaky clay walls, which led to significant gypsum leakage through holes, adding an element of challenge and excitement as students engaged in identifying and sealing the leaks (

Figure 3). The casting and mixing process proceeded sequentially under individual supervision, allowing for the controlled generation of waste. Following casting, students observed and felt the hardening of the gypsum with keen interest, further heightening their engagement.

The subsequent half-hour (the minimum time needed to clean up the gypsum mess) was dedicated to cleaning procedures of their workspaces and surroundings. The demonstrated gypsum mould was hardened by the session’s end, enabling the extraction of the clay positive and providing a tangible demonstration of the principle of using a positive to create a mould for a positive of another material. This session evoked growing enthusiasm among students for the project as their understanding deepened.

3.4. Cleaning the Negative

Despite the deviation from the original plan due to external circumstances, the extended interval led to the clay hardening more than anticipated. Surprisingly, this resulted in unexpected engagement and excitement among the students, particularly during removal. Using tools like hammers and chisels to remove the hardened clay added an element of fun to the session, which was especially surprising given that the students were from another group (

Figure 4). As the students tried removing the inner clay structure without damaging it, their excitement and concentration levels rose, fostering a dynamic and immersive learning environment.

Although two forms suffered minor damage due to thin walls, this allowed students to learn repair techniques using small quantities of clay. Overall, the unexpected time delay and the resulting challenges added an element of excitement and problem-solving to the session, enriching the learning experience for the students.

3.5. Filling the Mycelium in the Gypsum Forms

The session commenced with an intensive introduction to establish a clean and disinfected work environment. Lab gloves and masks were meticulously disinfected using 70% isopropanol and lab tissues, followed by thorough disinfection of the workbenches. The utilisation of masks, serving as an additional precaution against mycelium contamination, sparked reflections on past experiences with Covid-19 pandemic-related protocols, emphasising the importance of these measures in everyday lab environments—the stringent disinfection protocols aimed to safeguard the mycelium from contamination, heightening student anticipation. Paired into groups, students handled their previously prepared negative forms consecutively.

Wrapping disinfected cling film around the forms ensured seamless filling without compromising integrity (

Figure 5). As recommended by Grow Bio (

https://grow.bio), two layers of cling film were employed to counteract the moisture-reducing effects of the gypsum. This progress point was utilised to synchronise the students’ progress in the session. Following the disinfection of plastic containers, students retrieved blocks of mycelium, which, although exhibiting more significant growth during transport than in our trials, posed no issue, according to Grow Bio. The mycelium was ground manually, with a tablespoon of flour added to provide readily assimilable nutrients during post-grinding stress.

Layer-by-layer filling of the forms ensued, capturing the interest of even the most reserved students. Careful attention was paid to ensure uniform filling, especially along the edges, with periodic reminders emphasising the imperative of maintaining sterility—the final step involved covering the filled forms with perforated cling film to facilitate mycelial respiration.

The palpable excitement and immersion in the lab work were evident, with some students expressing their enthusiasm through personalised breast signs. Subsequently, the group naturally divided into two, with one group setting up the mini glasshouse tent for protected mycelial growth while the other engaged in discussions encompassing various scientific disciplines intersecting with the project.

The session concluded with students cleaning the desks, while floor cleaning was deferred until after their departure to mitigate potential mycelium dispersal. Despite the intense atmosphere, characterised by substantial excitement, the students demonstrated commendable focus on their tasks, making the session manageable for the instructors. Filled forms were stored within view but out of reach in the glasshouse tent, augmented with open water containers to enhance humidity levels.

3.6. Forming the Mycelium Communal Structure

Cultivation was carried out for six days due to logistical constraints preventing an earlier start. Students wore disinfected laboratory gloves during the procedure. Each student received their mycelium block individually. To extract the mycelium from the forms, 2/3 of the forms had to be broken to avoid damaging the mycelium blocks.

As students handled the mycelium blocks, their reactions varied widely, ranging from disgust to excitement and curiosity. The teachers noted that the mycelium growth was less than expected, potentially due to decreased humidity levels attributed to the gypsum used.

Students sequentially added their mycelium blocks to the communal artistic structure. The individual blocks were pressed together utilizing desinfected toothpicks. The communal structure was returned to the incubation tent for further growth.

The following day, during the scheduled session, we provided a comprehensive introduction to mycelium and its potential applications, emphasizing its role in sustainability. During the presentation, about half of the students showed interest, some students perceived questions related to biology and physics as unfitting. For the teachers, it was surprising to experience that even basic knowledge of the topic and the broader concept of sustainability was missing.

3.7. Educational Results

Understanding positive and negative forms is critical to developing three-dimensional thinking. The children created the clay positive form and cast a negative form (mould) in plaster; they experienced firsthand how a previously occupied space becomes a cavity. This process enhances their understanding of volume, space, and the relationships between dimensions, forming a foundation for creative design and three-dimensional thinking.

3.7.1. Skills Developed through Positive and Negative Molding

-

Spatial Thinking and Imagination

The children developed a keen understanding of volume, dimensions and the spatial relationships between objects and shapes.

-

Fine Motor Skills

Working with clay positive form and plaster negative form required precise hand movements, enhancing fine motor skills necessary for detailed work.

-

Problem-Solving Skills and Logical Thinking

Children learned to identify and overcome challenges in the design process, strengthening their logical thinking and problem-solving abilities.

-

Patience and Perseverance

The modelling and moulding process required patience and perseverance, teaching children that creative work demands time and meticulous effort.

-

Self-confidence and Self-Esteem

Successfully creating works of art and overcoming design challenges boosted children’s self-confidence and self-esteem.

-

Teamwork and Social Skills

When tasks were given as group work, children enhanced their ability to collaborate, communicate and share ideas effectively.

-

Cognitive Skills

Understanding and applying positive and negative forms promotes abstract thinking and comprehension of complex relationships.

3.7.2. Holistic Development

The skills acquired through modelling and three-dimensional thinking are crucial for artistic development and contribute significantly to children’s holistic education and personality development. These activities promote cognitive, social and emotional growth, preparing children for future challenges and opportunities.

3.8. Interdisciplinary Results

To evaluate the student’s learning outcomes, we designed a questionnaire inspired by a study conducted by the Interdisciplinary and Community Engaged Learning (Educational Development & Training) team at Utrecht University [

15]. This study involved interviews with successful interdisciplinary researchers to distil critical factors contributing to their success [

15]. The researchers identified three critical conditions: 1) immersion in the perspectives of others, 2) open-mindedness and modesty, and 3) finding common ground.

Participants in our interdisciplinary project were assessed to determine whether they met these criteria. Notably, one student highlighted that understanding a collaborator’s views in this context involves grasping their content and appreciating the origins of these perspectives. Team dynamics often involved participants with varying levels of expertise, providing opportunities to practice modesty. Despite occasional unmet expectations regarding partners or the project itself, teams effectively managed their tasks and readily found common ground (S1). For another student it was important and valuable to occasionally let go of his expectations and accept what comes. And that it is important to remain calm and composed when not everything goes according to plan and to trust in your own abilities (S2).

Yes, we approached the project with an open mind and embarked on an experiment. Everyone was very committed and competent in their field.

4. Conclusions

Integrating mycelium-based Engineered Living Materials (ELMs) into an interdisciplinary undergraduate curriculum yields profound insights and educational outcomes. This initiative, spearheaded through a collaborative effort at the University of Applied Arts Vienna, successfully merged art and science, focusing on biomimetics and sustainability. By leveraging the innovative potential of mycelium, students were guided through a transformative journey encompassing design, craftsmanship and scientific inquiry. The workshop facilitated hands-on experiences in creating mycelium-based artworks and instilled a deep appreciation for sustainability practices among participants. Through the meticulous process of designing, modelling, casting and cultivating mycelium, students developed crucial skills in spatial thinking, fine motor skills and problem-solving. These skills are vital for fostering creativity and preparing students for future challenges in a rapidly evolving world. The project’s interdisciplinary nature encouraged collaboration and communication across disciplinary boundaries. Students learned to navigate diverse perspectives and embrace the complexities inherent in interdisciplinary teamwork. This holistic approach enriched their educational journey and equipped them with essential skills such as patience, perseverance and self-confidence. Looking ahead, the success of this initiative paves the way for future explorations at the intersection of art, science and sustainability. By continuing to integrate innovative materials and interdisciplinary approaches into curricula, educational institutions can nurture a new generation of creative thinkers and problem solvers committed to shaping a more sustainable future. Ultimately, this endeavour advances academic scholarship and serves as a testament to the transformative power of interdisciplinary education in addressing global challenges. Through ongoing collaboration and innovation, we can inspire future generations to lead with creativity, empathy and a profound respect for our planet.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this article.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge TU Wien Bibliothek for financial support through its Open Access Funding Programme.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- van Nieuwenhoven, R.W.; Drack, M.; Gebeshuber, I.C. Engineered Materials: Bioinspired “Good Enough” versus Maximized Performance. Advanced Functional Materials 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Mautner, A.; Luenco, S.; Bismarck, A.; John, S. Engineered mycelium composite construction materials from fungal biorefineries: A critical review. Materials & Design 2020, 187, 108397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbee, J. Innovative Mycelium Packaging for All Kinds of Products — grown.bio. www.grown.bio, 2024. [Accessed 08-05-2024].

- Aiduang, W.; Jatuwong, K.; Luangharn, T.; Jinanukul, P.; Thamjaree, W.; Teeraphantuvat, T.; Waroonkun, T.; Lumyong, S. A Review Delving into the Factors Influencing Mycelium-Based Green Composites (MBCs) Production and Their Properties for Long-Term Sustainability Targets. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemu, D.; Tafesse, M.; Mondal, A.K. Mycelium-Based Composite: The Future Sustainable Biomaterial. International Journal of Biomaterials 2022, 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, M.; Haigh, L.; Soria, A.C. The Circularity Gap Report 2023; Circle Economy: Amsterdam, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Park, D.; Qin, Z. Material Function of Mycelium-Based Bio-Composite: A Review. Frontiers in Materials 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, A.; Bonenberg, A.; Sydor, M. Mycelium-Based Composites: Surveying Their Acceptance by Professional Architects. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.S.; Wells, M.A. Integrating interdisciplinary education in materials science and engineering. Nature Reviews Materials 2023, 8, 491–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.T. Interdisciplinarity; Wayne State University Press: Detroit, MI, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, J.T. Humanities, culture, and interdisciplinarity; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mateus-Berr, R. Applied Design Thinking Lab and Creative Empowering of Interdisciplinary Teams. In Encyclopedia of Creativity, Invention, Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Springer: New York, 2019; pp. 1–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhan, Z. A Systematic Review on Design Thinking Integrated Learning in K-12 Education. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 8077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMBWF. Änderung der Verordnung über die Lehrpläne der Volksschule und Sonderschulen. BGBl. II Nr. 1/2023.

- Diphoorn, T.; Huysmans, M.; Knittel, S.; Mc Gonigle, B.; van Goch, M. Travelling Concepts in the Classroom: Experiences in Interdisciplinary Education. Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Education 2023, 12. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).