1. Introduction

The occurrence of fire accidents caused by polymer ignition is becoming increasingly prevalent globally, resulting in significant loss of life and property. This phenomenon has emerged as a matter of societal concern [

1]. So, it is essential to decrease fire hazards by some effective methods. One of the most efficacious and convenient methods for the prevention of polymer ignition is the utilization of intumescent fire protection coatings [

2,

3]. Indeed, the process presents several advantages. Firstly, it does not alter the intrinsic properties of the material, for example, the mechanical properties. Secondly, it is a rapid process. Thirdly, it may be used on multiple substrates, for example, metallic materials, polymers, textiles, and wood. [

1,

4,

5]. Intumescent fire protection coatings are widely recognized worldwide in the field of fire protection due to their ecological safety. They are prepared based on carbonization agents, acid sources, and blowing agents [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Expandable graphite, which is frequently employed as a blowing agent and smoke suppressant in an extensive array of flame retardant materials, represents a graphite intercalation compound(GIC) [

10,

11,

12,

13]. When heat exposure, EG expands strongly, forming a large barrier that separates the polymer from the fire source to provide fire protection[

14]. EG exhibits high flame retardant efficiency, low toxicity and is smokeless, rendering it an optimal material for fire protection. Nevertheless, during the combustion process, the vermiculite structural layer formed by EG exhibits low adhesion and is susceptible to destruction by thermal convection. [

15]. Furthermore, the compatibility between EG and polymer is poor, which would affect the materials' mechanical and flame-retardant properties.

In order to address the aforementioned issues, this paper presents a modification of expandable graphite (MEG) with a carbonizing agent, resulting in the synthesis of an organic-inorganic hybrid intumescent flame retardant. Intumescent fire-retardant coatings have been prepared based on IFR, IFR/EG, and IFR/MEG, respectively. The fire-retardant influence of MEG in the intumescent fire-retardant coating has been studied by CCT, DaqPRO 5300 radiation heat flow meter, and TGA.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The materials include melamine (MEL) pentaerythritol (PER) and ammonium polyphosphate (APP) provided by Tianjin BASF Chemical Co., Ltd., China, styrene-acrylic emulsion (with the solid content of 50.84%) provided Anhui Kobang Resin Technology Co. Ltd., China), Expandable graphite (EG) obtained from Jiangsu Xianfeng Nanomaterials Technology Institute, China, Phosphorus oxychloride (POCl3, A.R.), Ammonia water and Ethanediol from Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China. IFR was obtained with a mass ratio of 3:1:1 for APP, MEL and PER.

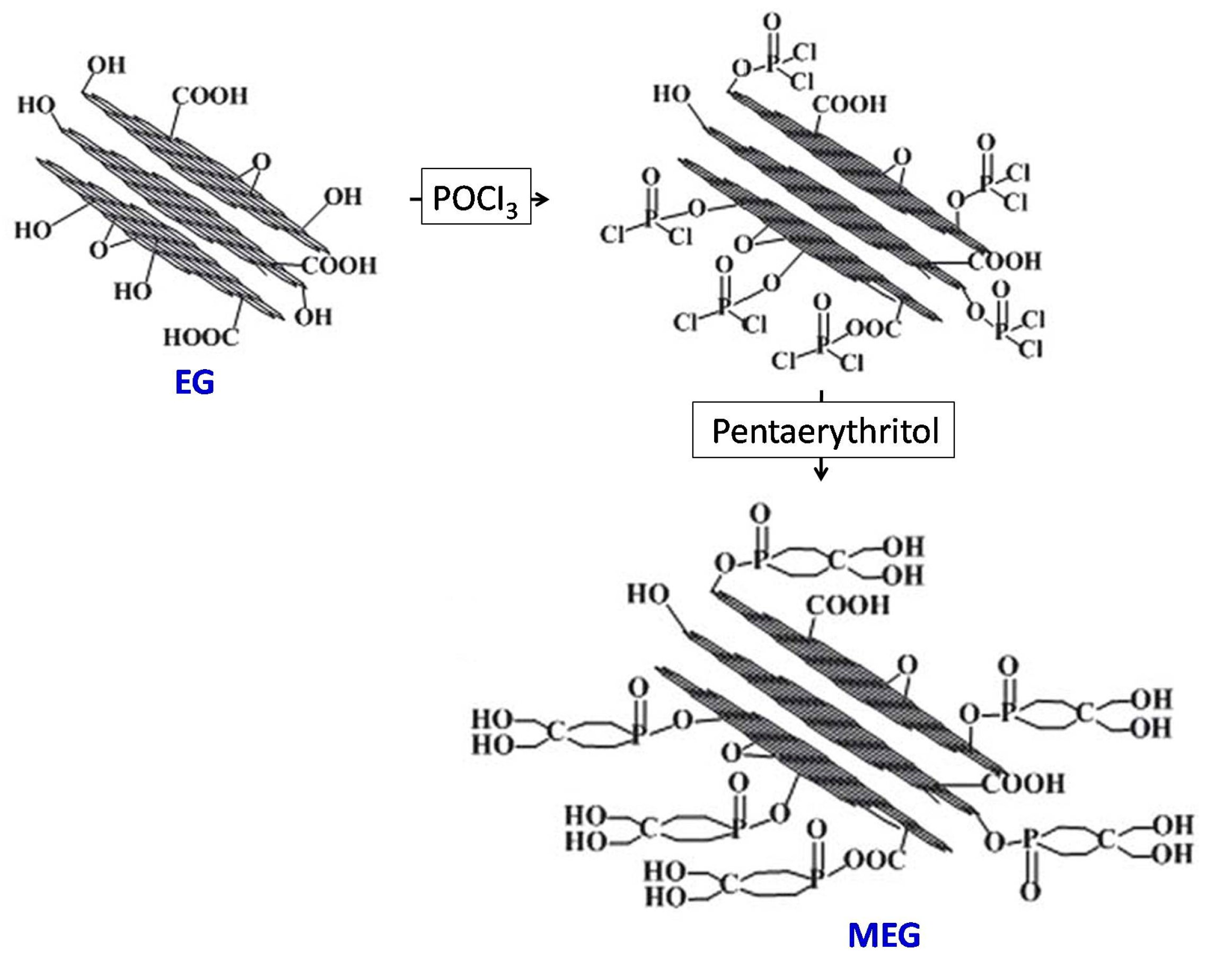

2.2. Synthesis of MEG

A solution of EG (20 g), POCl3 (6 mL) and 1,4-dioxane (500 mL) was placed into a reactor and heated to 60 °C for a period of 3 hours. Subsequently, 9 g of PER was added to the reactor and heated to 100 °C for a further 6 h, resulting in the crude product. The resulting crude product was filtered, washed with 1,4-dioxane, and subsequently dried under a lower pressure at 80 °C for 12 h, thereby obtaining MEG, as shown in

Figure 1.

2.3. Preparation of Intumescent fire-Retardant (IFR) Coatings

IFR, EG, and MEG were mixed according to their respective percent, as indicated in

Table 1. Mix IFR, IFR/EG and IFR/MEG separately in a shear mixer at 1000 rpm for 20 minutes. The aforementioned mixture was then combined with styrene-acrylic emulsion and other auxiliaries, which were stirred into a uniform solution at 400 rpm for a period of 20 minutes. The coatings comprising IFR, IFR/EG, and IFR/MEG were applied to wood boards of dimensions 90×90×3 mm³ and 70×70×3 mm³, respectively, for use in cone calorimeter and smoke density analyzer tests. Then, the coatings containing IFR, IFR/EG, and IFR/MEG were applied to the iron board with the size of 90×90×0.5 mm

3, respectively, which can be used for DaqPRO 5300 radiation heat flow meter tests. The samples should be cured for 24 h at a temperature of 25°C. The samples were then heated to 50 °C using a vacuum oven and held for another 24 h. The dosage of intumescent fire-retardant coating is 250 g/m

2, with the preparation formulation shown in

Table 1.

2.4. Measurements

The Fourier transform infrared spectrum is recorded by the spectrometer (VARIUS, Avantes. Netherlands). Heat tests were conducted using a cone calorimeter (Shanghai Shuangxu Electronics Co., Ltd., China). The specimen size was 90×90×3 mm3 , wrapped in aluminum foil, with an external heat flux of 35 kW/m2. Experiments were conducted to investigate the flow of radiant heat using a radiant heat flow meter (Qingdao Jingcheng Instrumentation Co., Ltd.). One end of a thermocouple was positioned at the base of an iron plate coated with a flame retardant coating to facilitate the collection of temperature data throughout the combustion process. The other end of the thermocouple was linked to the radiant heat flow meter. Thermogravimetric analysis was conducted on a DT-50 (Setaram, France) instrument with a nitrogen protective gas. Approximately 10.0 mg of the sample was placed in a crucible and heated to 900 °C, with the heating rate was set at 10 K/min.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of MEG

The production process of MEG is divided into two steps. First, POCl₃ is grafted onto the EG surface. Then P-Cl is esterified with PER.

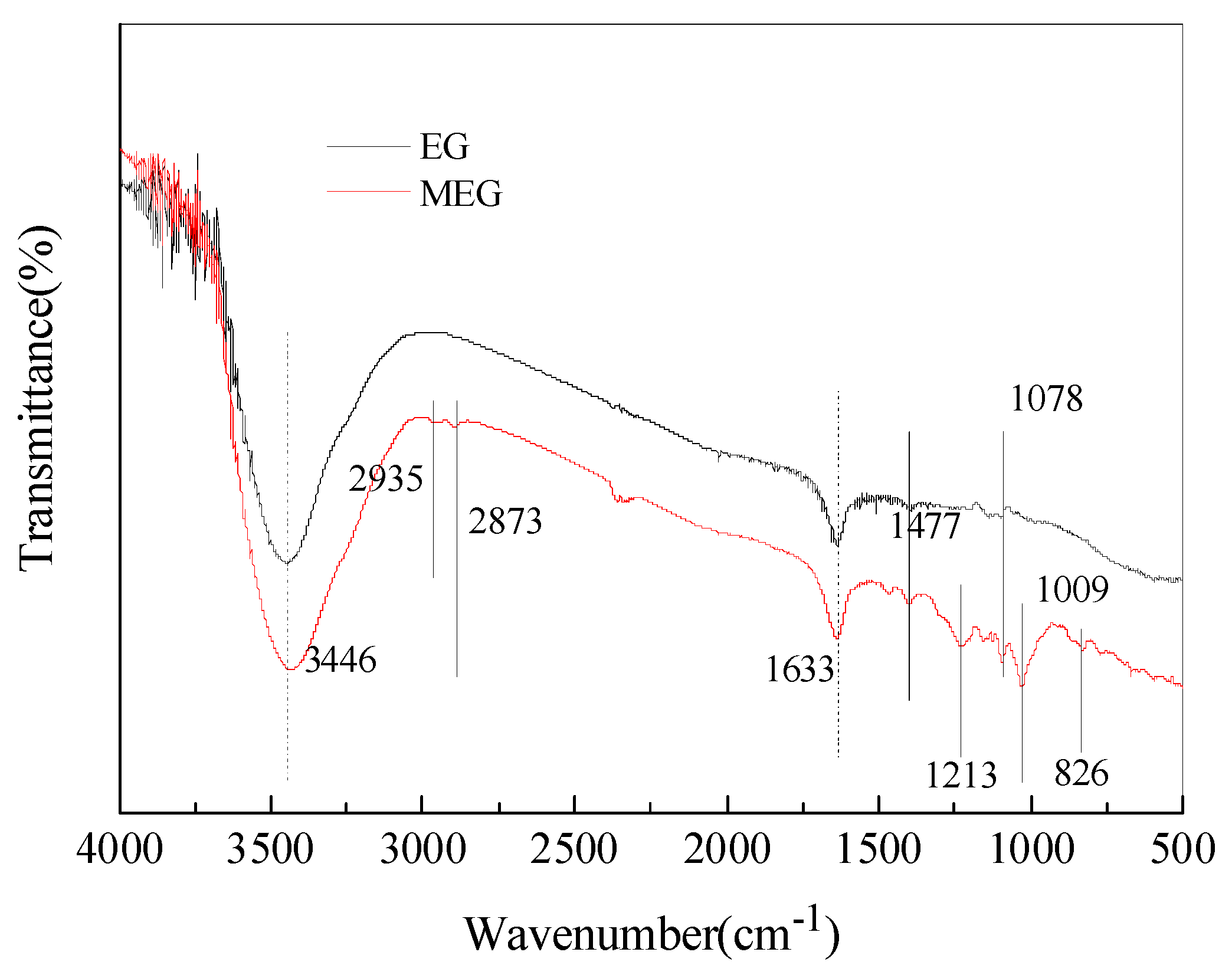

Figure 2 shows the FTIR spectra of EG and MEG. In the spectrum of EG, a solid peak appears at 3452 cm-1, which is due to the stretching vibration of -OH and C-O groups. This stretching vibration indicates the presence of -OH in EG and its ability to react with POCI3. There are also many new absorption peaks in the MEG spectra. The peaks at 2935 cm-1 and 2873 cm-1 are carbon-hydrogen bonds, while the peak at 1213 cm-1 is P=O. The peak at 1078 cm-1 indicates cyclic P-O bonds, while the peaks at 1009 cm-1 and 826 cm-1 indicate P-O-C bonds. The infrared spectra of EG and MEG showed that an organic-inorganic hybrid intumescent flame retardant was successfully synthesised by modifying MEG with a carbonylating agent.

3.2. Cone Calorimeter Test

Cone calorimetry is an important method for flammability characterisation and is based on the principle of oxygen consumption. The heat release rate (HRR) as measured by the combustion chamber thermometer (CCT) is a significant parameter in fire analysis, as it provides an indication of the intensity of a fire. Nevertheless, it is frequently employed to delineate fire hazard behaviours, as evidenced by the averaged HRR or peak HRR (PHRR) in actual scenarios [

16,

17]. The PHRR value is utilized to quantify the intensity of a fire.

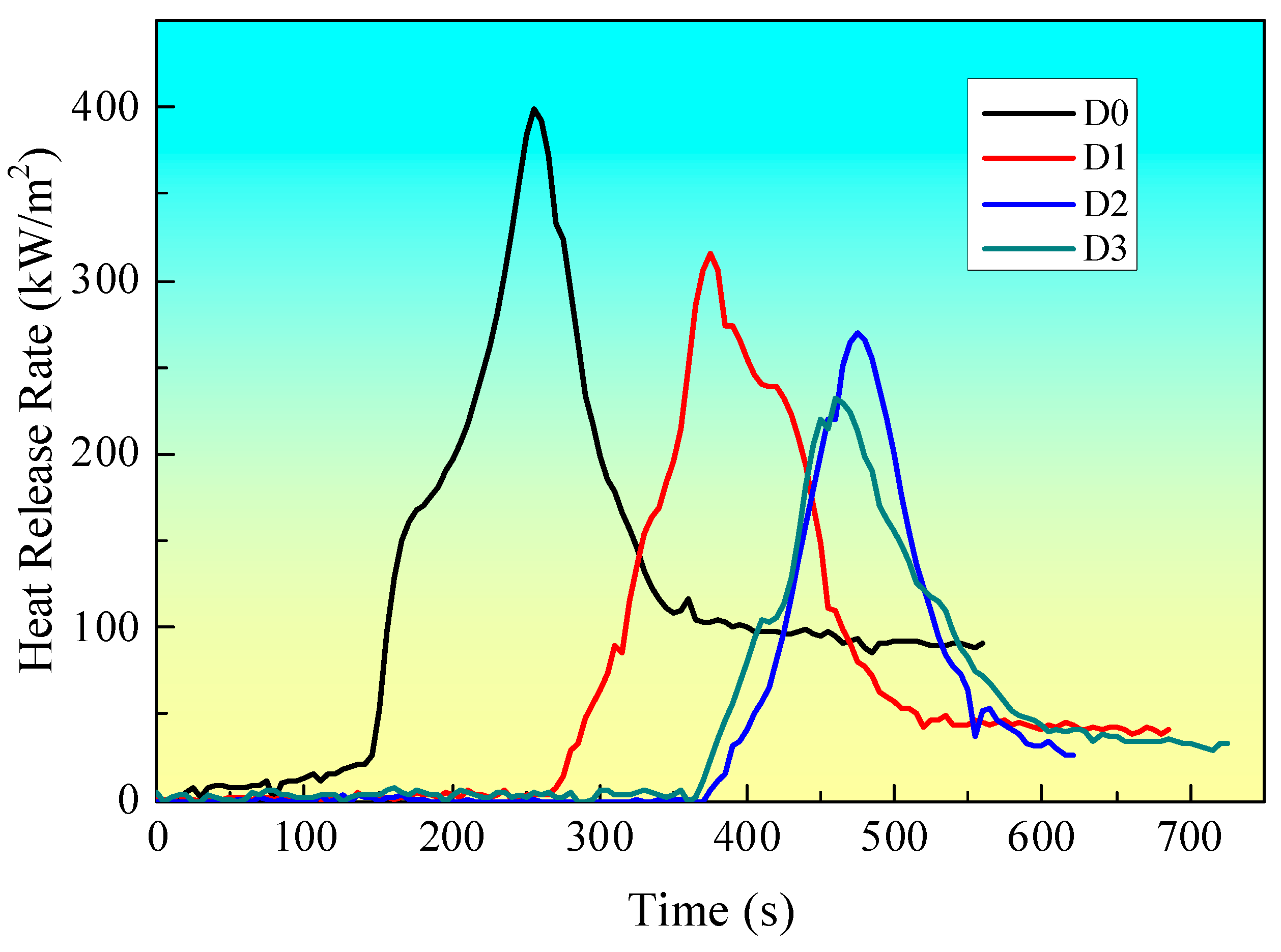

3.2.1. Heat Release Rate (HRR)

Figure 3 illustrates the HRR curves of samples with distinct intumescent fire-retardant coatings, as obtained from CCT. The pertinent data from the CCT are provided in

Table 2. It can be observed that sample D0, which lacks any coating, ignites rapidly and reaches a peak heat release rate (PHRR) of 398.6 kW/m². The heat release rate value for sample D1, which has a coating containing only IFR, is lower than that of sample D0. The addition of EG to the fire-retardant coating system results in a reduction in the PHRR value of sample D2 in comparison to sample D1. Moreover, the addition of EG results in a prolongation of the ignition time (TTI) in comparison to both D0 and D1, as presented in

Table 2. Furthermore, the addition of MEG results in a further reduction in the PHRR value in comparison to sample D2, which contains EG. Sample D3, which incorporates MEG, exhibits the lowest PHRR value (232.8 kW/m²) and the longest TTI (356 s) among all samples presented in

Table 2. This suggests that the incorporation of MEG produces a practical synergistic flame retardant effect when combined with IFR in this coating system.

The synergistic effect of EG and APP promotes char morphology and improves thermal stability. The formation of a char layer prevents heat transfer into the underlying material and the ingress of combustible gases into the flame zone. Concurrently, EG and APP release non-combustible gases, including CO₂, NH₃, SO₂, which dilute the combustible gases in the gas phase. The combination of EG and APP is therefore a highly reliable IFR system [

18]. In the case of D3 with MEG, the charring agent grafted onto the surface of EG can change the structure of char residue after CCT. The charring agent can change the wormlike structure from the D2 sample into an intumescent compact char structure. The intumescent compact char structure formed from the D4 sample has good heat and mass transfer properties. So, the D3 sample shows the lowest HRR among all samples.

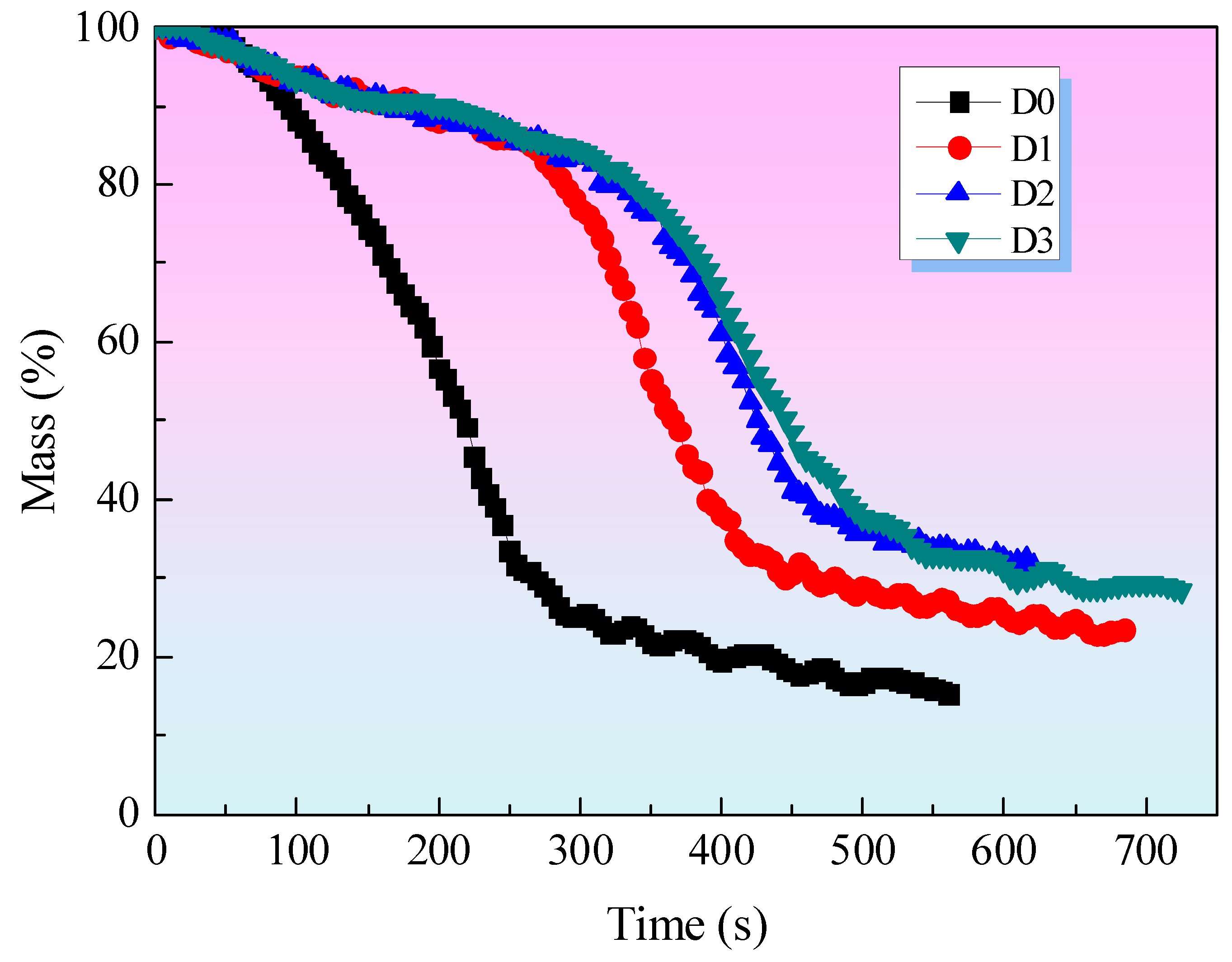

3.2.2. Mass

Figure 4 illustrates the weight of the char residues for all samples. It can be observed that the char residue weight of sample D2, which contains both EG and IFR, is greater than that of sample D1, which contains only IFR, throughout the entire burning period. This suggests that EG can enhance the weight of the char residue by increasing its expansion degree, which in turn improves its heat shield performance. Therefore, the char residue weight of D2 is greater than that of D1. The addition of MEG to the fire-retardant coating (sample D3) resulted in an improvement in the char residue. The char residue of sample D3, comprising IFR and MEG, is the highest among all samples prior to 550 seconds. At this point, the percentage of char residue in sample D3 is in excess of 40 wt%. This evidence suggests that MEG can enhance the formation of char residue in this coating system. This can be explained by the fact that compact char residues will form on the surface of coatings with IFR and MEG during combustion, acting as a physical protective layer. The char residue would act as a protective barrier, limiting the diffusion of oxygen to the substrate or decreasing the rate of volatilization of combustible gases, particularly aromatic gases which are precursors of smoke. [

19,

20]. When the test time exceeds 550 seconds, the char residue weight of D3 is observed to be lower than that of D2. This phenomenon can be attributed to the formation of amorphous carbon on the surface of the D3 sample, which can undergo oxidation under conditions of high-heat radiation, resulting in a reduction in the char residue weight of the D3 sample.

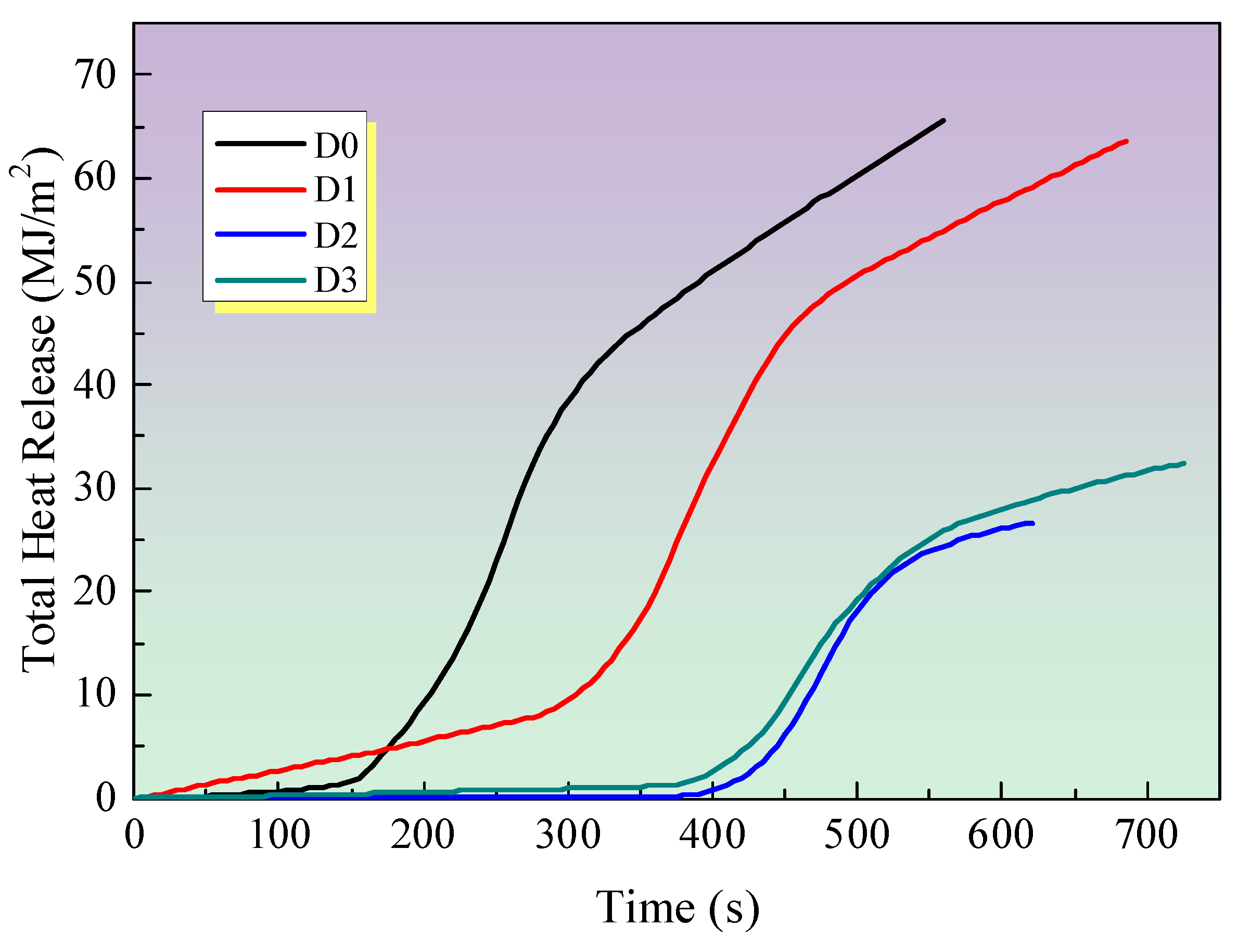

3.2.3. Total Heat Release (THR)

Figure 5 illustrates the total heat release (THR) of all samples. It has been proposed that the gradient of the THR curve can be used to represent flame spread [

21,

22]. It can be observed that the THR value of the D0 sample, is the highest among all samples. In comparison to the D0 sample, the gradient of the THR curve for the sample with only IFR is markedly diminished, thereby indicating a deceleration in the rate of flame spread. The incorporation of EG and MEG into intumescent fire-retardant coating systems results in a further reduction in the THR value in comparison to the D1 sample with only IFR. This is attributed to the formation of a substantial intumescent, compact char residue on the surface of the samples, which effectively restricts flame spread. Additionally, the reduction in THR value is in accordance with the HRR curves in

Figure 2, which demonstrate that the addition of EG or MEG can effectively decrease the THR value.

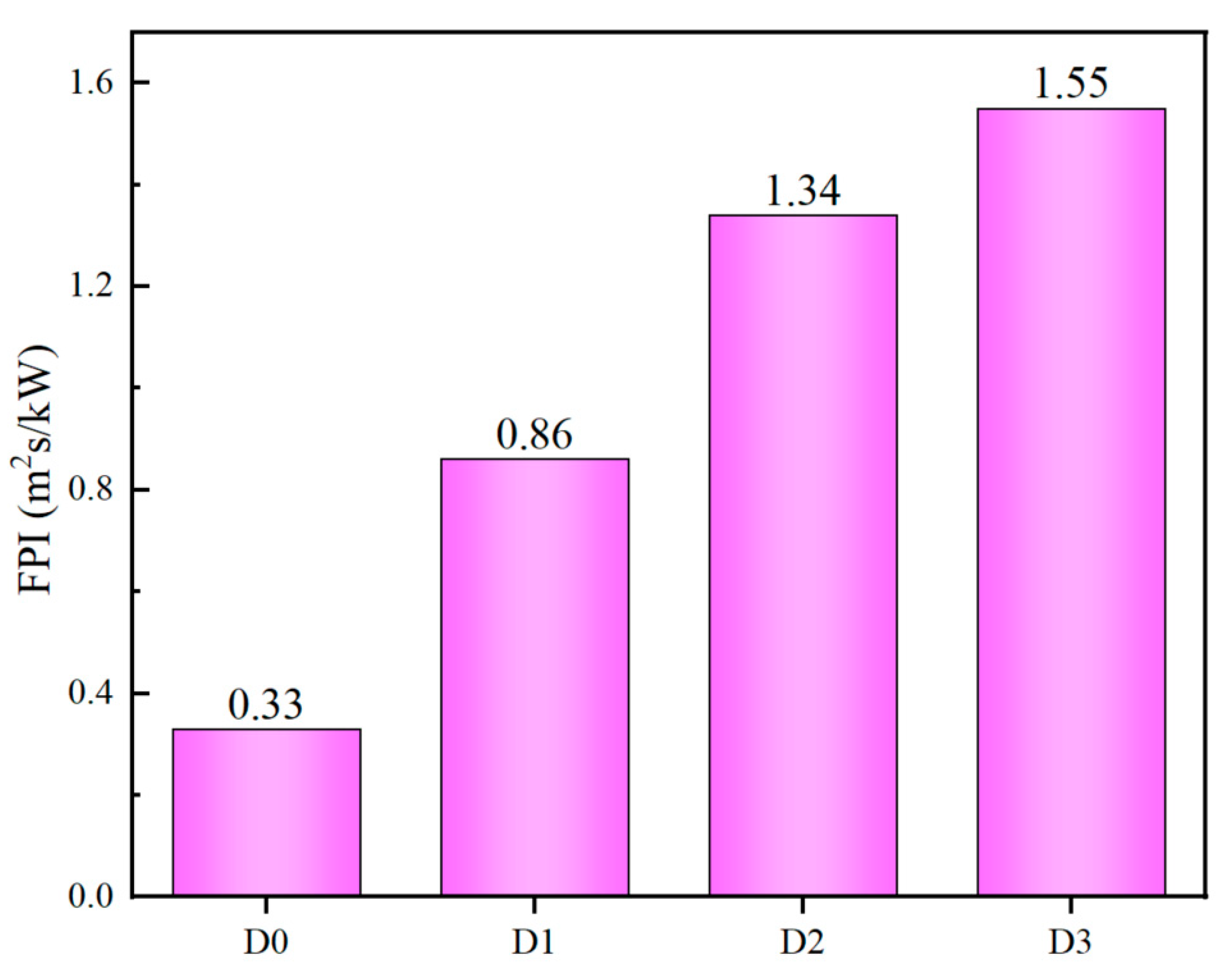

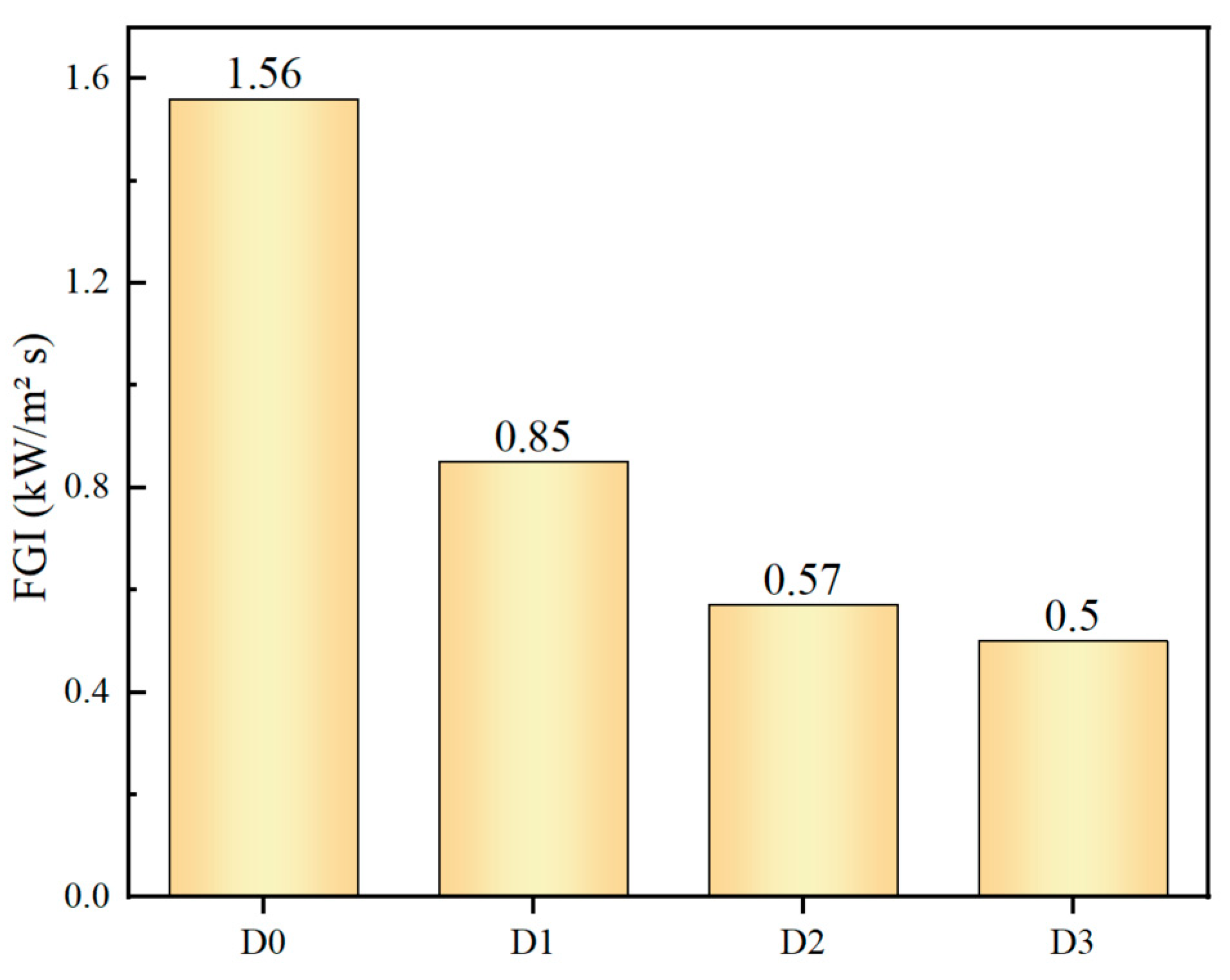

3.2.4. Fire Performance Index (FPI) and Fire Growth Index (FGI)

Subsequent to the cone calorimeter test, the fire performance index (FPI) and fire growth index (FGI) are calculated in order to assess the fire hazard. The FPI (m² s/kW) is the ratio of time to ignition (TTI) to PHRR, and the FGI (kW/m² s) is defined as the ratio of peak HRR to time to PHRR (TTP), respectively [

23]. The FPI and FGI are calculated directly from the data obtained from cone calorimeter tests, and thus provide a direct reflection of the safety ranking of the samples. It can be reasonably deduced that materials with a higher safety rank should require high FPI and low FGI values. The FPI and FGI results are illustrated in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, respectively [

24,

25]. The D3 sample, which has been treated with IFR/MEG, displays the most considerable FPI value and the lowest FGI value, indicating that it is assigned a relatively high fire safety rank.

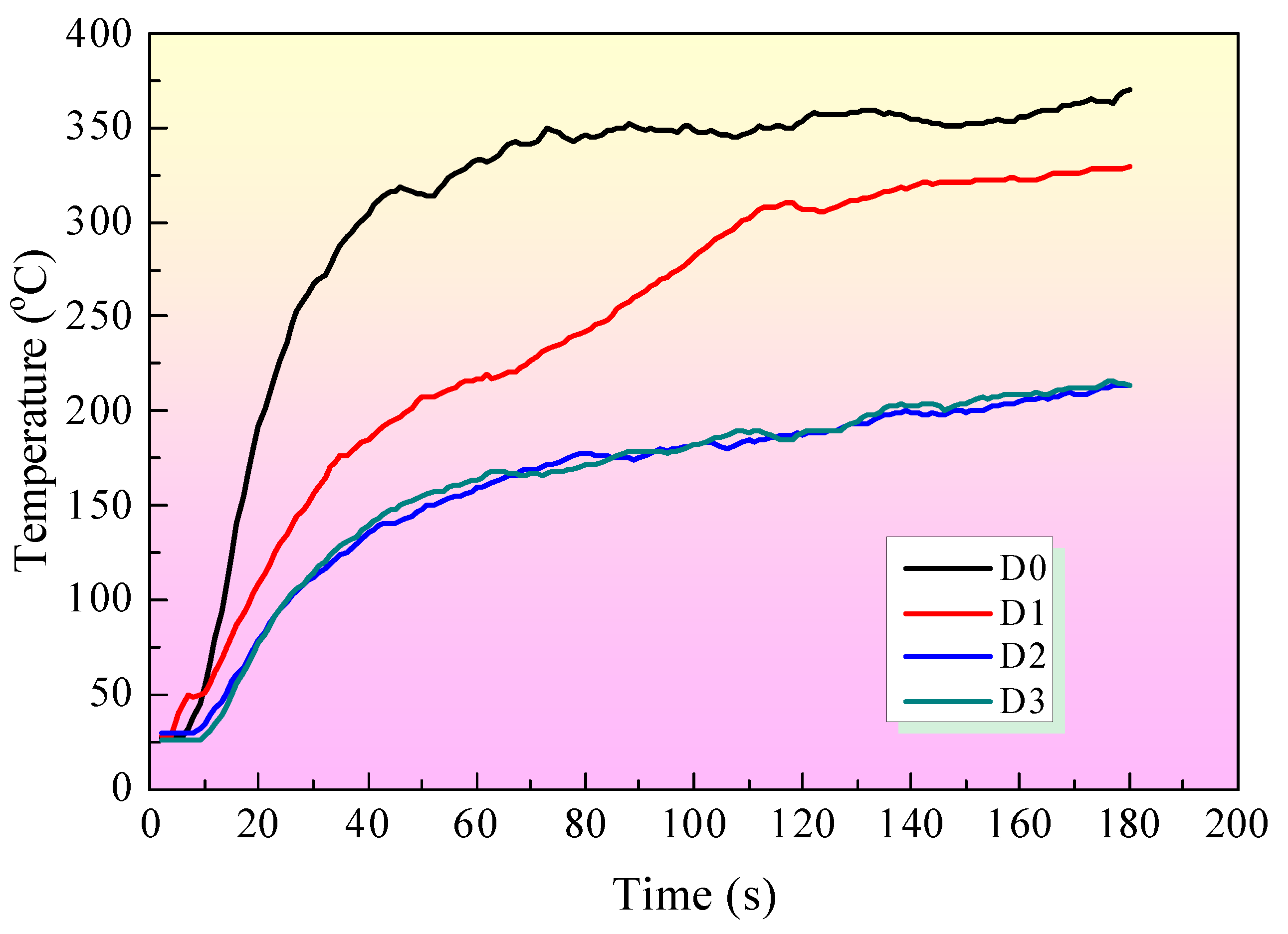

3.3. DaqPRO 5300 Radiation Heat Flow Meter Test

Figure 8 shows the temperature curves from the DaqPRO 5300 radiation heat flow meter tests. Four coating samples (from sample D0 to sample D3) were applied to the iron board with the size of 90×90×0.5 mm

3, respectively. The temperature of the D0 sample is higher than those of any other samples with a fire-retardant coating. The fire-retardant coating on the iron board's surface decreases the temperature compared with D0 without any coating. When EG is incorporated into the intumescent fire-retardant coating system, the temperature of sample D2 with IFR/EG is lower than that of D1 sample with only IFR. Furthermore, adding MEG can further decrease the temperature compared with the D2 sample. Besides, MEG can improve char residue's structure, resulting in a good fire-retardant effect.

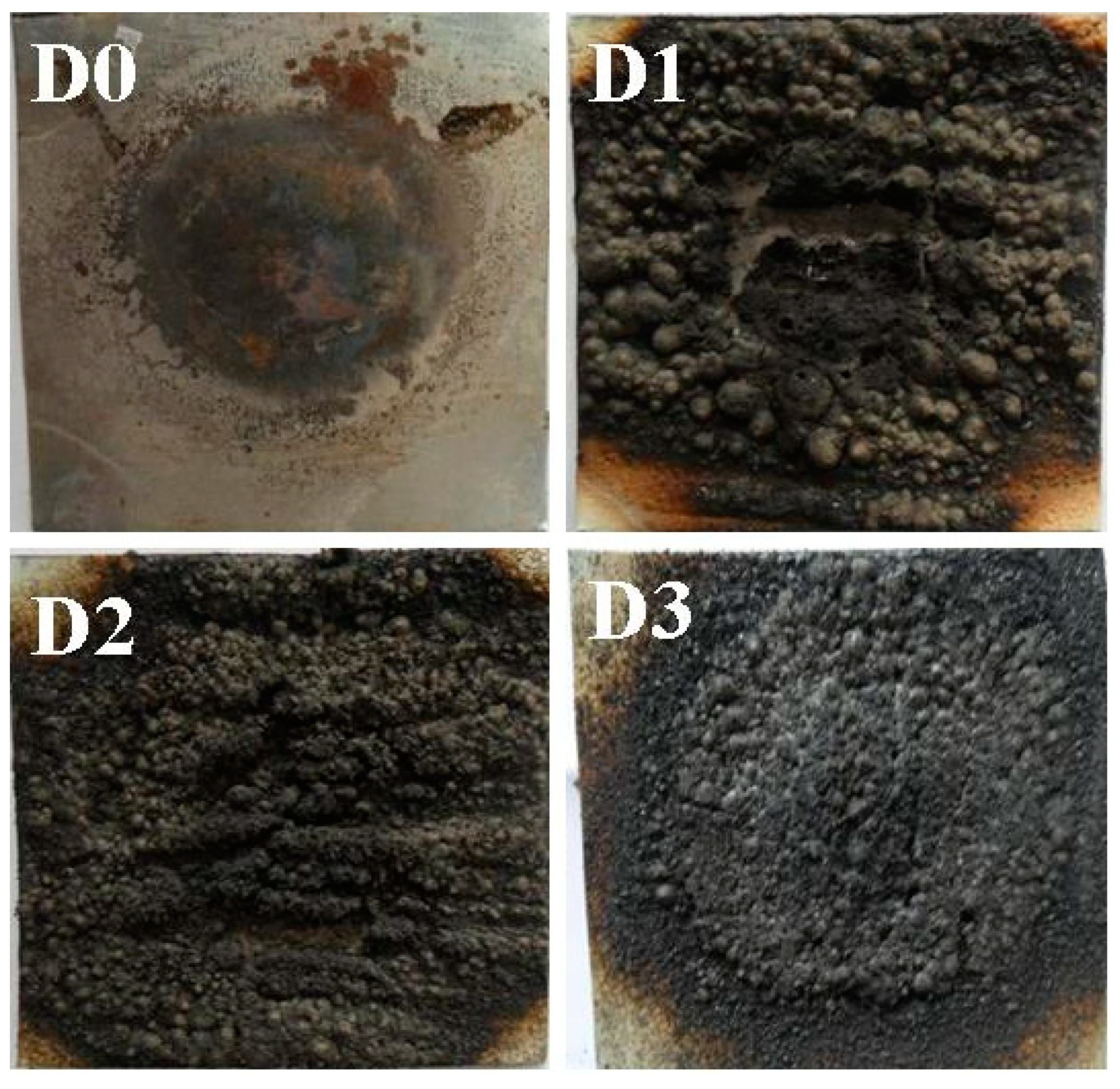

Figure 9 illustrates the char residues of intumescent fire-retardant coatings following the DaqPRO 5300 radiation heat flow meter test. The formation of an effective carbon layer can impede the transfer of heat between the combustion zone and the underlying substrate. It can be seen that D1 sample with only IFR has relatively high char residue. But, it is not compact enough. D2 sample containing both IFR and EG has high and regular char residues. In the case of the D3 sample with IFR and MEG, the most intumescent compact char residues are found among all samples. This indicates that MEG can contribute to forming char residue and prevent heat from passing through fire-retardant coating systems.

3.4. Thermal Gravimetric Analysis (TGA)

TGA is an efficient way to assess the thermal stability of diverse materials. Additionally, it provides insight into the degradation of polymers at varying temperatures by quantifying the onset of degradation (T

5.0%)

, defined as the temperature at which a 5 wt% mass loss is observed, the temperature corresponding to the maximum degradation rate (T

max), and the residual char [

19,

26].

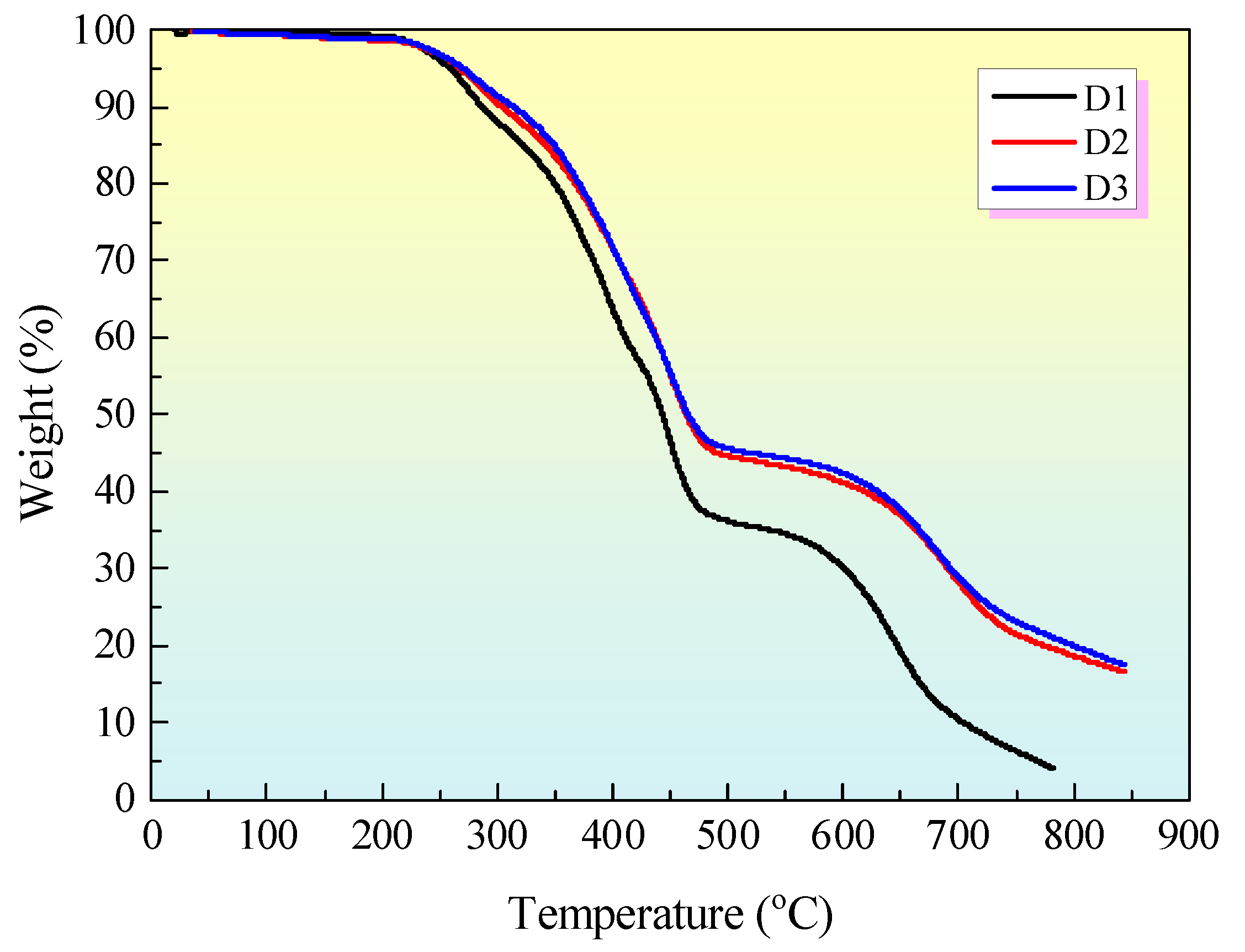

Figure 10 illustrates the thermogravimetric (TGA) curves for the samples. The D1 sample, which comprises only IFR, initiates its decomposition at approximately 250 °C, exhibiting a weight loss of 5 wt%. The char residue of D1 is lower than that of the D2 sample with IFR/EG or the D3 sample with IFR/M-EG the whole time. It also can be seen that D1 with only IFR is less stable than the samples of D2 and D3 between 250 °C and 450 °C. Adding EG improves thermal stability compared with D1, which only has IFR. Moreover, the addition of MEG to the intumescent fire-retardant coating resulted in the highest char residue of D3 among all samples. That MEG contributes to enhancing the carbon residues in the IFR coating system, which is in agreement with the Mass results after CCT.

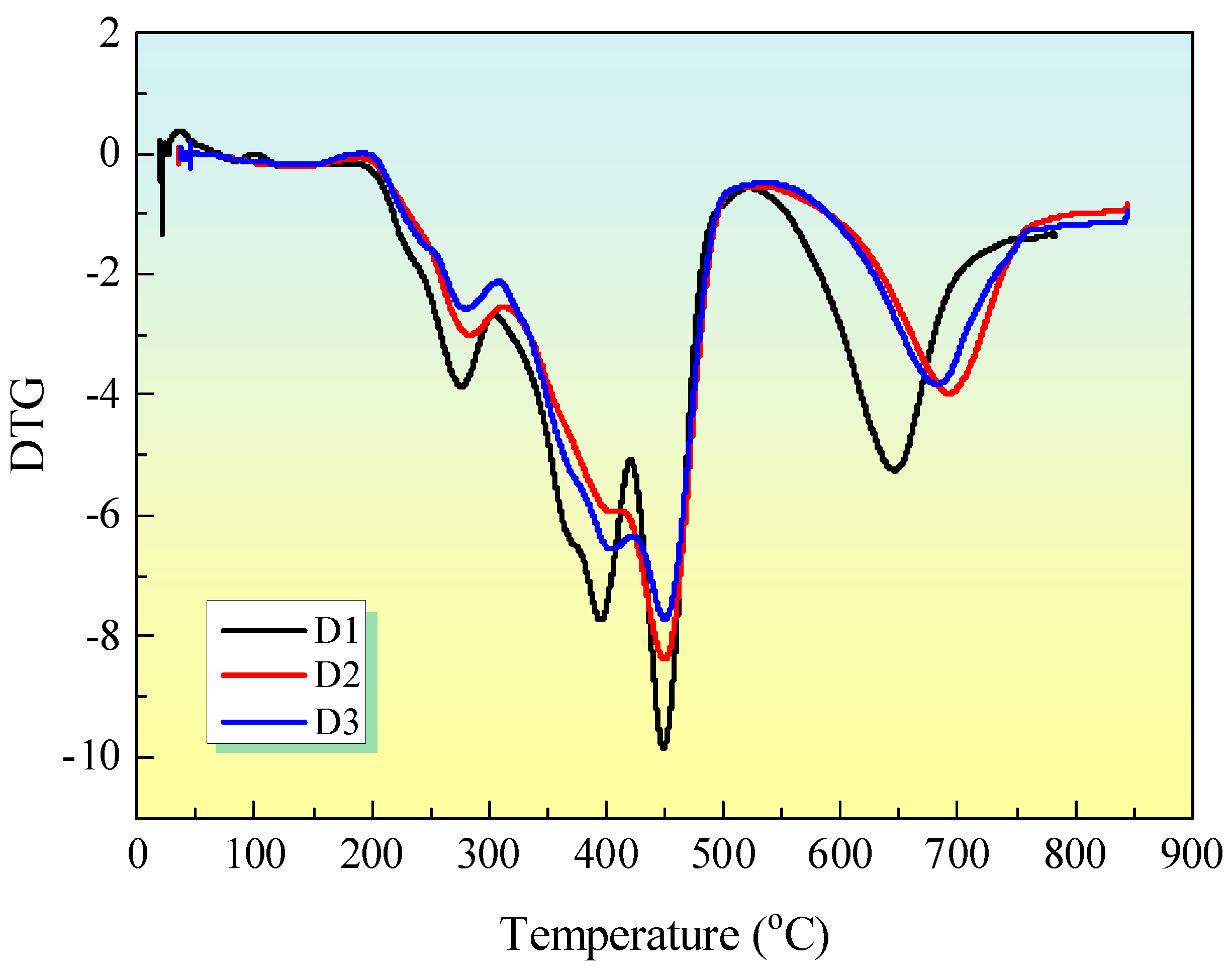

Figure 11 shows the DTG curves for IFR coatings. The thermal degradation of IFR coatings occurs in four distinct stages. The temperature of the maximum mass loss rate (T

max) of sample D1 with IFR and sample D2 with IFR/EG are observed to be lower than that of sample D3 with IFR/MEG throughout the degradation process. Furthermore, the addition of MEG has been observed to accelerate the initial stage of thermal degradation. Melamine and APP degrade between 300 and 500 oC, releasing N2 and NH3. PER and MEL also decompose in this temperature range [

27]. When MEG was added to these coatings, the thermal stability of the second and third degradation stages was significantly enhanced. The amorphous carbon formed in the previous stages is decomposed, so that a fourth degradation stage occurs between 500 and 800°C. The presented evidence lends support to the proposition that MEG enhances the thermal stability of these intumescent fire-retardant coatings.

4. Conclusions

An organic-inorganic hybrid intumescent flame retardant was successfully synthesised by modifying expandable graphite (MEG) with a charring agent. The CCT test results demonstrate that MEG has the capacity to markedly reduce the HRR and THR while simultaneously enhancing the char residue. The radiation heat flow meter test results demonstrate that MEG can enhance the structure of char residue, thereby achieving a favourable fire-retardant effect. The TGA results indicate that MEG can augment the thermal stability of intumescent fire-retardant coating. It can be concluded that MEG can produce an effective synergistic fire-retardant influence with IFR in an intumescent fire-retardant coating system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M., Q.S., F.D. and J.L.; methodology, L.M., Q.S., and F.D.; software, Q.S. and J.L.; validation, F.D.; formal analysis, L.M.; investigation, L.M., Q.S., and F.D.; resources, J.L.; data curation, F.D.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M., Q.S., F.D. and J.L.; writing—review and editing, Q.S., Z.X.; supervision, F.D.; project administration, L.M., H.Y. and F.D.; funding acquisition, L.M., H.Y. and F.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52005517), the State Key Laboratory for High-Performance Complex Manufacturing, Central South University, China (No. ZZYJKT2022-02), the Science and Technology Research and Development Command Plan Project of Zhangjiakou, China (No. 2311005A), 2024 Graduate Innovation Fund project of Hebei University of Architecture (No. XY2024080).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- S. Huo, Y. Guo, Q. Yang, H. Wang, P. Song, Two-dimensional nanomaterials for flame-retardant polymer composites: a mini review, Advanced Nanocomposites, 1(2024) 240-247. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, Y. Guo, W. Shao, F. Xiao, Benign design of intumescent fire protection coatings for steel structures containing biomass humic acid as carbon source, CONSTR BUILD MATER, 409(2023) 134001. [CrossRef]

- J. Shin, H. Moon, S. Jee, K.C. Lee, H.W. Jung, H. Paik, S.M. Noh, Characteristics of phosphorus-nitrogen based flame-retardant monomers for UV-curable coatings on battery PET pouches, PROG ORG COAT, 195(2024) 108665. [CrossRef]

- J. Li, C. Zhai, R. Yang, Expanded charring flame retardant effect of caged polysilsesquioxane containing Schiff base structure on poly(ethylene terephthalate) combustion, POLYM DEGRAD STABIL, 227(2024) 110891. [CrossRef]

- N.F. Attia, S.E.A. Elashery, F. El-Sayed, M. Mohamed, R. Osama, E. Elmahdy, M. Abd-Ellah, H.R. El-Seedi, H.B. Hawash, H. Ameen, Recent advances in nanobased flame-retardant coatings for textile fabrics, Nano-Structures & Nano-Objects, 38(2024) 101180.

- B.K. Kandola, A.R. Horrocks, Complex char formation in flame-retarded fibre-intumescent combinations—II. Thermal analytical studies, POLYM DEGRAD STABIL, 54(1996) 289-303. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xia, W. Chai, Y. Liu, X. Su, C. Liao, M. Gao, Y. Li, Z. Zheng, Facile fabrication of starch-based, synergistic intumescent and halogen-free flame retardant strategy with expandable graphite in enhancing the fire safety of polypropylene, IND CROP PROD, 184(2022) 115002. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, D. Li, M. Xu, B. Li, Synthesis of a novel phosphorus and nitrogen-containing flame retardant and its application in rigid polyurethane foam with expandable graphite, POLYM DEGRAD STABIL, 173(2020) 109077. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zheng, Y. Liu, B. Dai, C. Meng, Z. Guo, Fabrication of cellulose-based halogen-free flame retardant and its synergistic effect with expandable graphite in polypropylene, CARBOHYD POLYM, 213(2019) 257-265. [CrossRef]

- Q. Liu, X. Chen, G. Zhu, X. Gu, H. Li, S. Zhang, J. Sun, X. Jin, Preparation of a novel supramolecular intumescent flame retardants containing P/N/S/Fe/Zn and its application in polylactic acid, FIRE SAFETY J, 128(2022) 103536. [CrossRef]

- P. Panczek, R. Ostrysz, D. Krassowski, Flame Retardants 2000, Proceedings of the 9th Flame Retardants 2000 Conference, London, UK, February 8–9, 2000; 105–111.

- F. Okisaki, FLAMECUT GREP series new non-halogenated flame-retardant systems. New Developments and Future Trends in Fire Safety on a Global Basis International Conference, San Francisco, March 16–19, 1997; 11–24.

- D.W. Krassowski, D.A. Hutchings, S.P. Oureshi, Tomorrow’s Trends in Fire-retardant Regulations, Testing, Applications, and Current Technologies, Fire-retardant Chemicals Association, [Fall Conference], Naples, FL, October 13–16, 1996; 137–146; CODEN: 64WIAYCAN 127: 191956; AN 1997: 563210 CAPLUS.

- J. Yu, L. Sun, L. Ding, Y. Cao, X. Liu, Y. Ren, Y. Li, A UV-curable coating constructed from bio-based phytic acid, D-sorbitol and glycine for flame retardant modification of rigid polyurethane foam, POLYM DEGRAD STABIL, 227(2024) 110892. [CrossRef]

- R. Lian, H. Guan, Y. Zhang, M. Ou, Y. Jiang, L. Liu, C. Jiao, X. Chen, A green organic-inorganic PAbz@ZIF hybrid towards efficient flame-retardant and smoke-suppressive epoxy coatings with enhanced mechanical properties, POLYM DEGRAD STABIL, 217(2023) 110534. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou, B. Tawiah, N. Noor, Z. Zhang, J. Sun, R.K.K. Yuen, B. Fei, A facile and sustainable approach for simultaneously flame retarded, UV protective and reinforced poly(lactic acid) composites using fully bio-based complexing couples, Composites Part B: Engineering, 215(2021) 108833. [CrossRef]

- R. Zhou, J. Mu, X. Sun, Y. Ding, J. Jiang, Application of intumescent flame retardant containing aluminum diethyphosphinate, neopentyl glycol, and melamine for polyethylene, SAFETY SCI, 131(2020) 104849. [CrossRef]

- M. Xu, X. Yan, F. Li, Y. Xiao, J. Li, Z. Liu, H. He, Y. Li, Z. Zhu, Fabrication high toughness poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/thermoplastic starch composites via melt compounding with ethylene-methyl acrylate-glycidyl methacrylate, INT J BIOL MACROMOL, 250(2023) 126446. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Wang, Z. Wu, J. Zhao, M. Sun, X. Ma, A. Abudula, G. Guan, Enhanced catalytic oxidation of toluene over amorphous cubic structured manganese oxide-based catalysts promoted by functionally designed Co–Fe nanowires, CATAL SCI TECHNOL, 14(2024) 2806-2816. [CrossRef]

- A. Sut, E. Metzsch-Zilligen, M. Großhauser, R. Pfaendner, B. Schartel, Rapid mass calorimeter as a high-throughput screening method for the development of flame-retarded TPU, POLYM DEGRAD STABIL, 156(2018) 43-58. [CrossRef]

- X. Almeras, M. Le Bras, P. Hornsby, S. Bourbigot, G. Marosi, S. Keszei, F. Poutch, Effect of fillers on the fire retardancy of intumescent polypropylene compounds, POLYM DEGRAD STABIL, 82(2003) 325-331.

- S. Wang, Q.F. Lim, J.P.W. Toh, M.Y. Tan, Q. Zhu, W. Thitsartarn, C. He, S. Liu, J. Kong, A versatile, highly effective intumescent flame-retardant synergist for polypropylene and polyamide 6 composites, COMPOS COMMUN, 42(2023) 101699. [CrossRef]

- A. Sut, E. Metzsch-Zilligen, M. Großhauser, R. Pfaendner, B. Schartel, Rapid mass calorimeter as a high-throughput screening method for the development of flame-retarded TPU, POLYM DEGRAD STABIL, 156(2018) 43-58. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, Y. Guo, W. Shao, F. Xiao, Benign design of intumescent fire protection coatings for steel structures containing biomass humic acid as carbon source, CONSTR BUILD MATER, 409(2023) 134001. [CrossRef]

- A. Meena, A. Talha Aqueel Ahmed, A. Narayan Singh, A. Jana, H. Kim, H. Im, Hierarchical Fe2O3 nanosheets anchored on CoMn layered double hydroxide nanowires for high-performance supercapacitor, APPL SURF SCI, 656(2024) 159553. [CrossRef]

- M. Chang, S. Hwang, S. Liu, Flame retardancy and thermal stability of ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymer nanocomposites with alumina trihydrate and montmorillonite, J IND ENG CHEM, 20(2014) 1596-1601. [CrossRef]

- J.Z. Liang, J.Q. Feng, C.P. Tsui, C.Y. Tang, D.F. Liu, S.D. Zhang, W.F. Huang, Mechanical properties and flame-retardant of PP/MRP/Mg(OH)2/Al(OH)3 composites, Composites Part B: Engineering, 71(2015) 74-81. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).