Submitted:

22 July 2024

Posted:

23 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

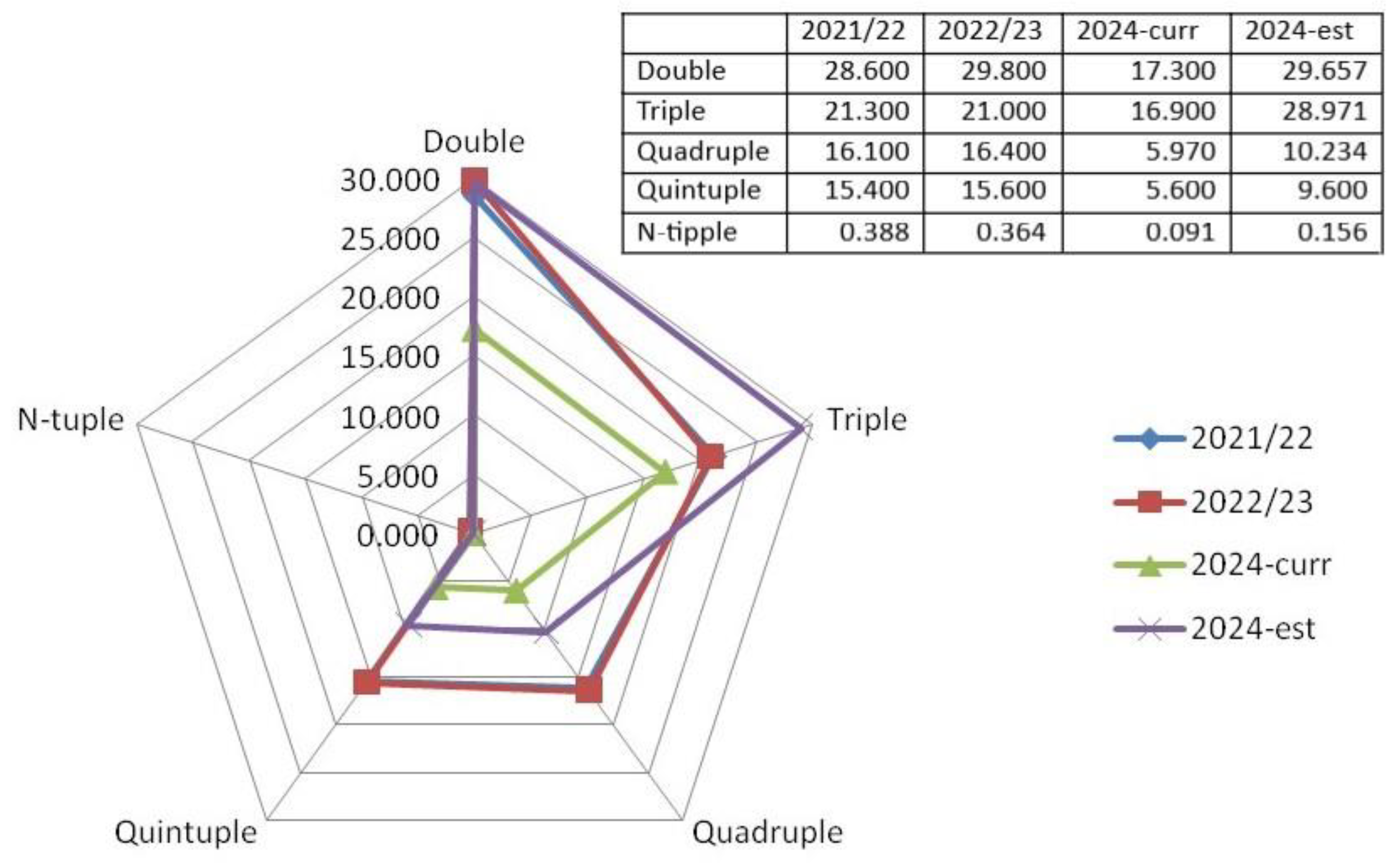

3. Results

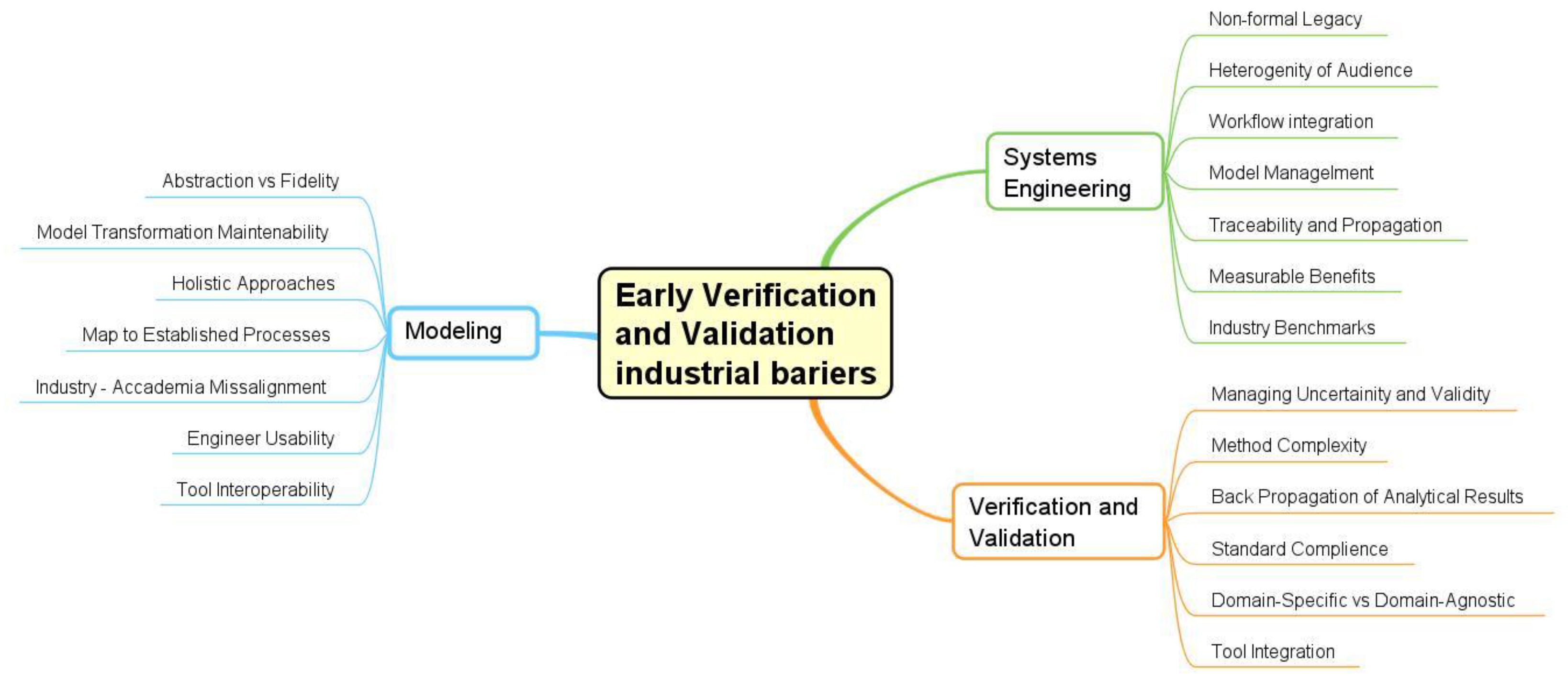

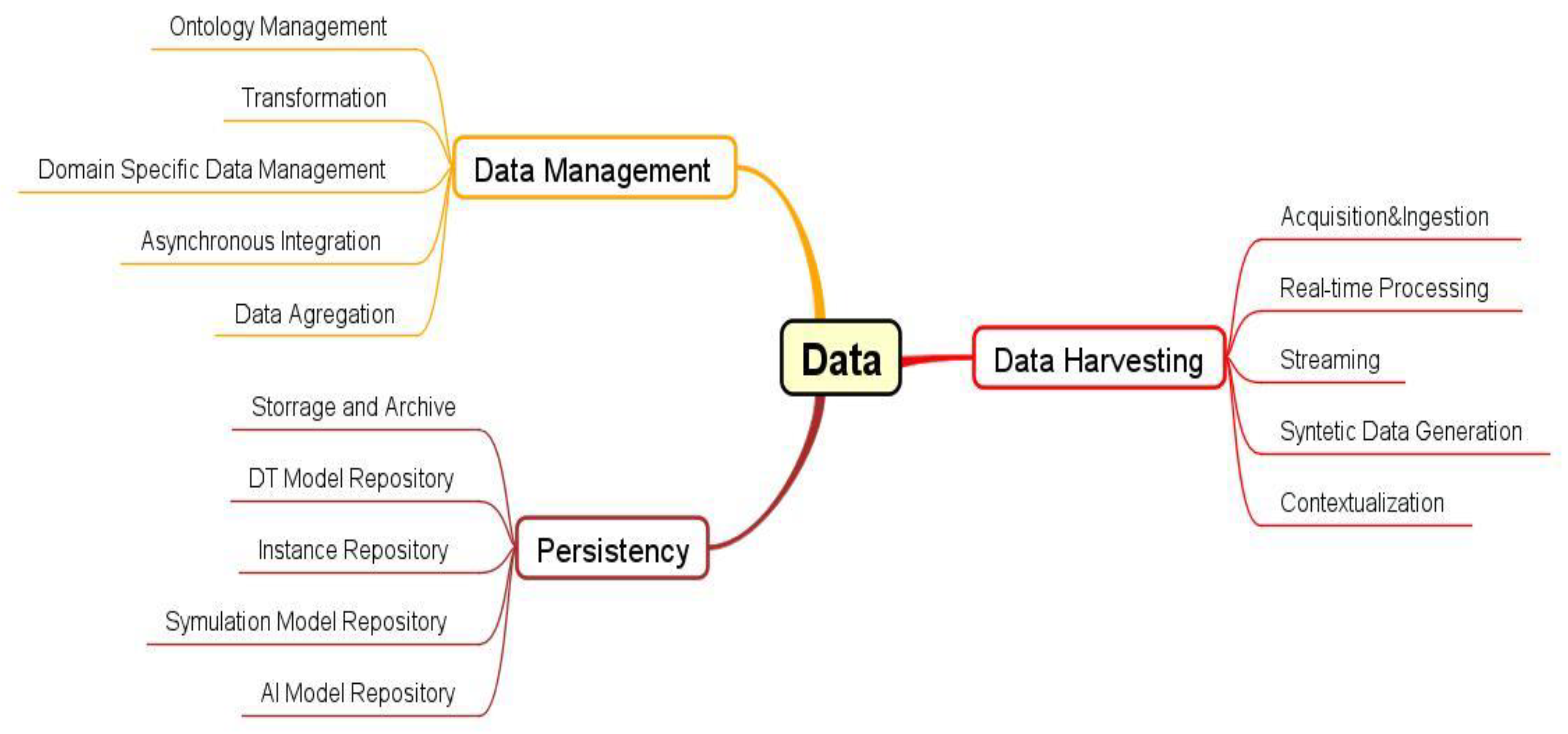

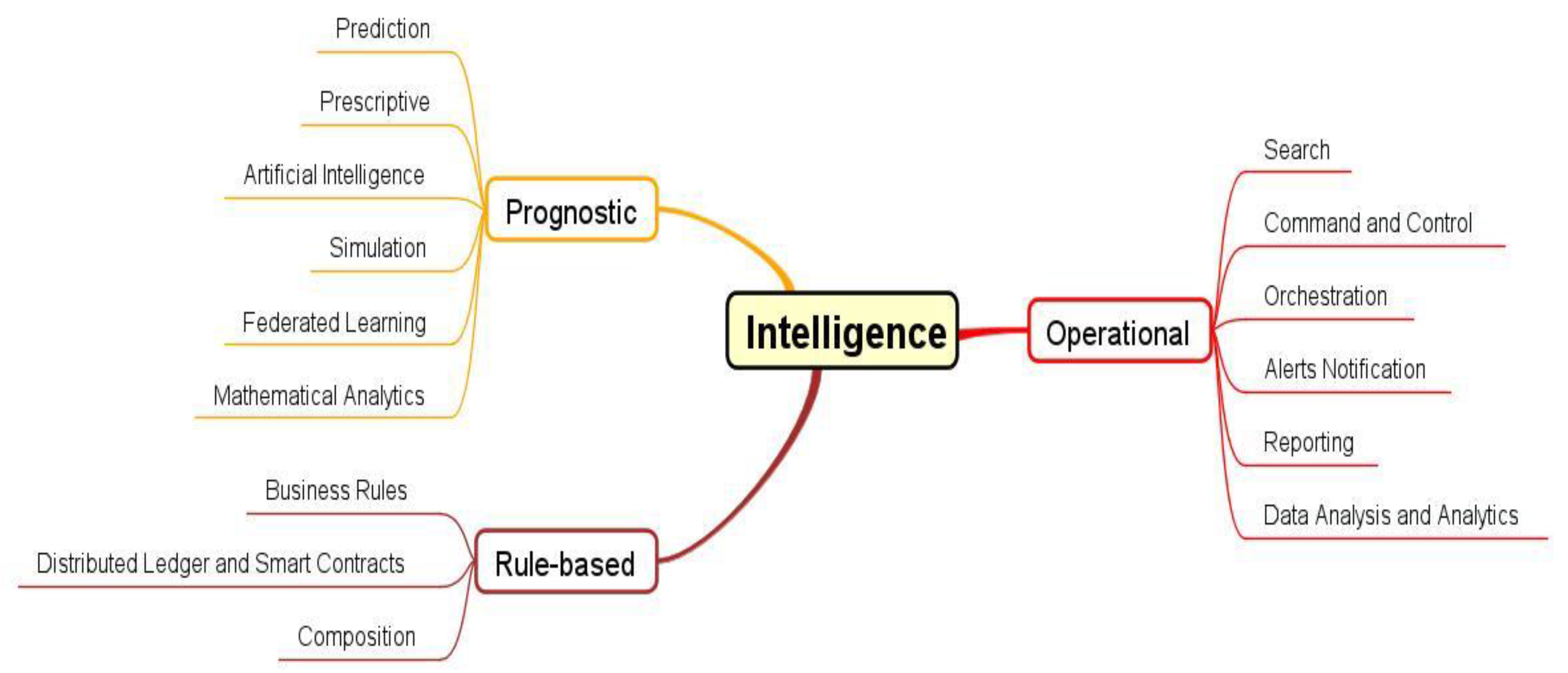

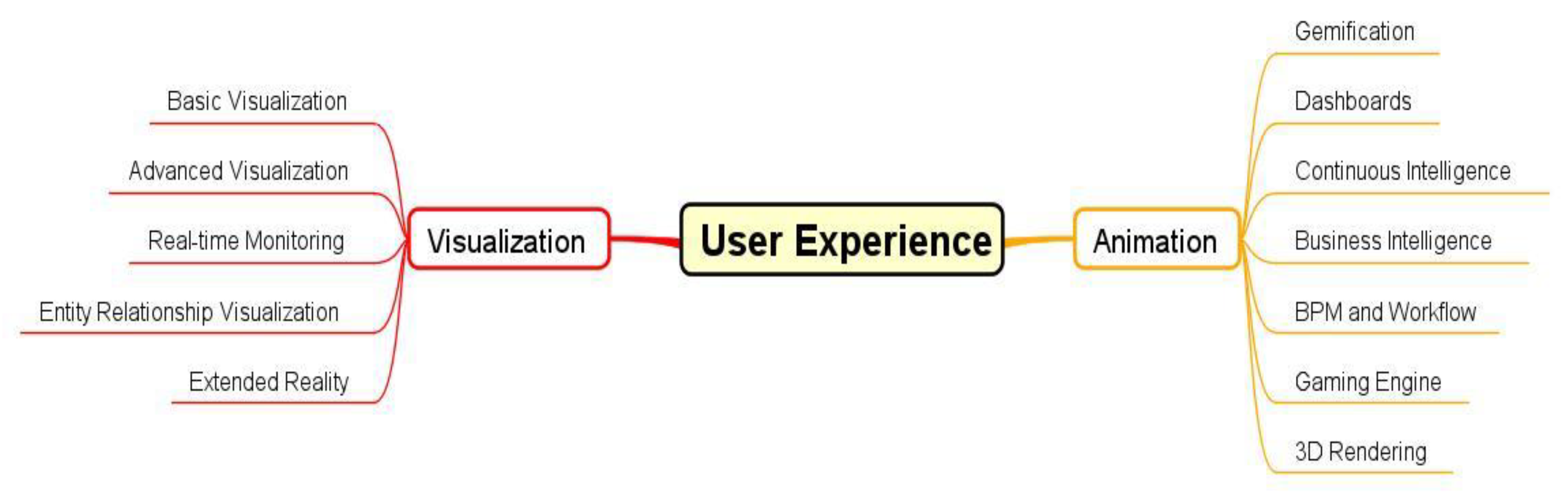

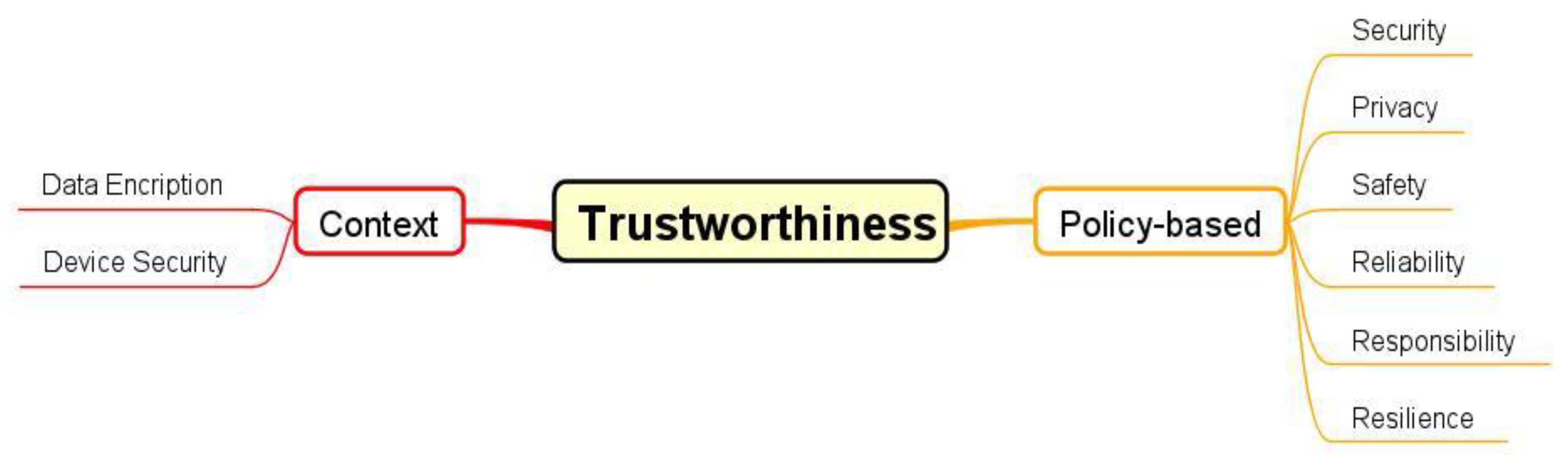

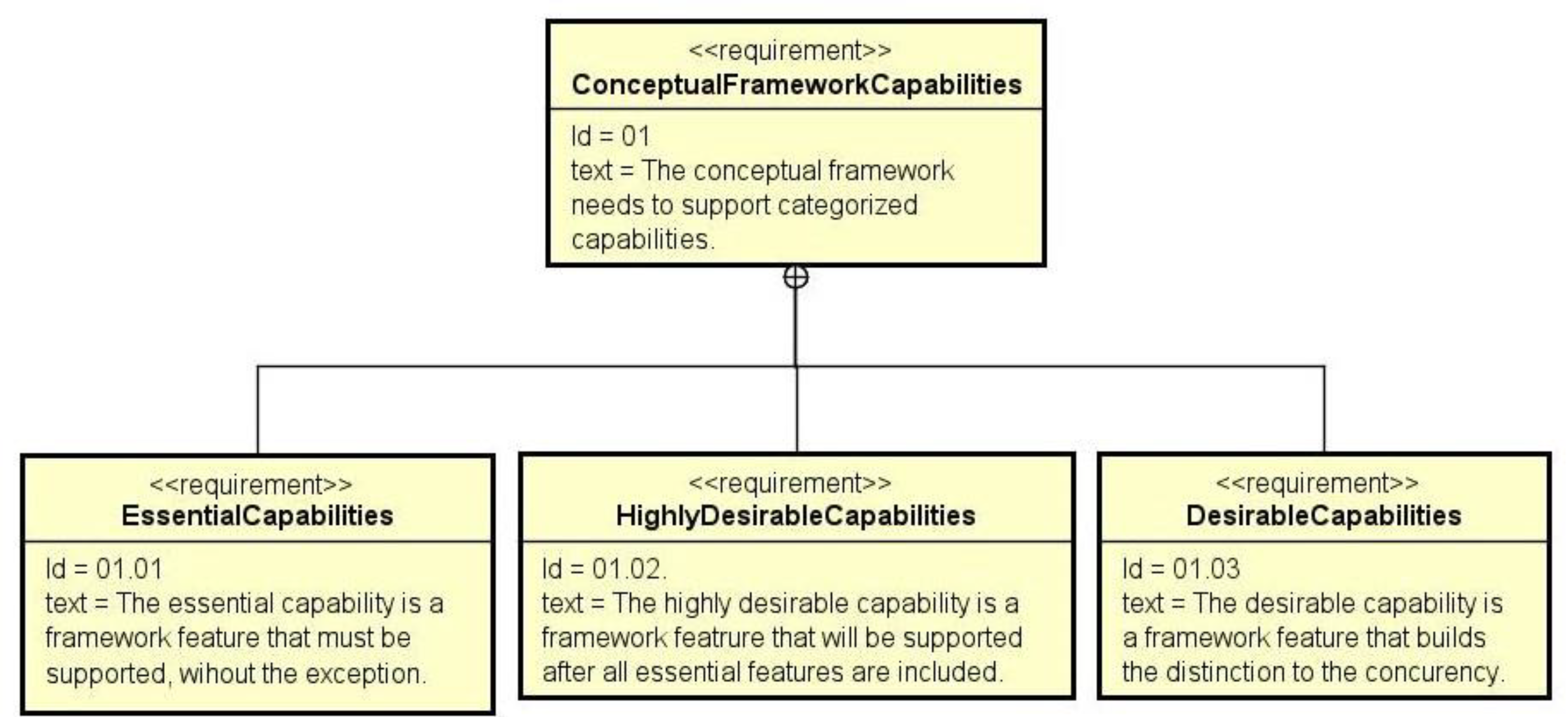

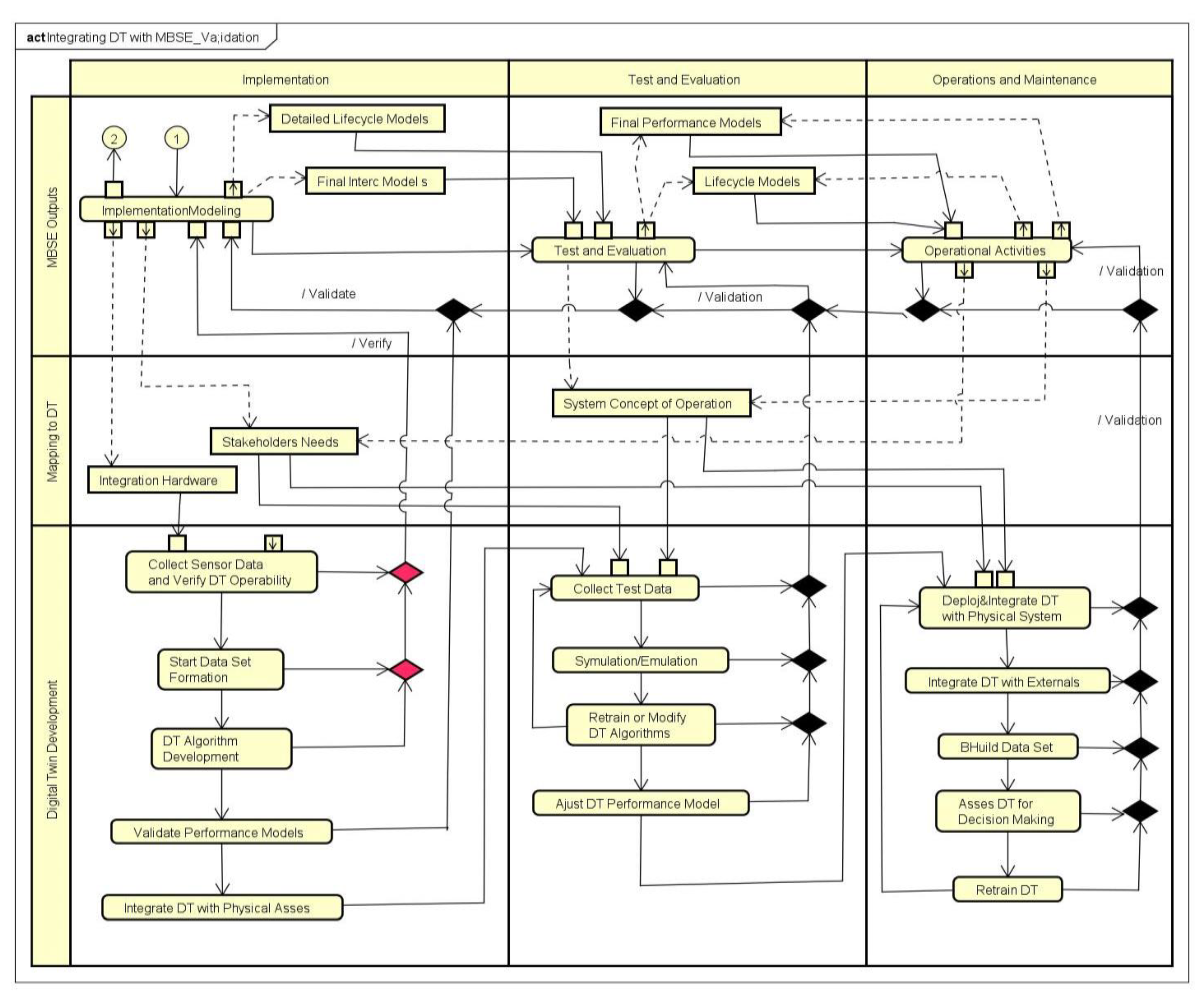

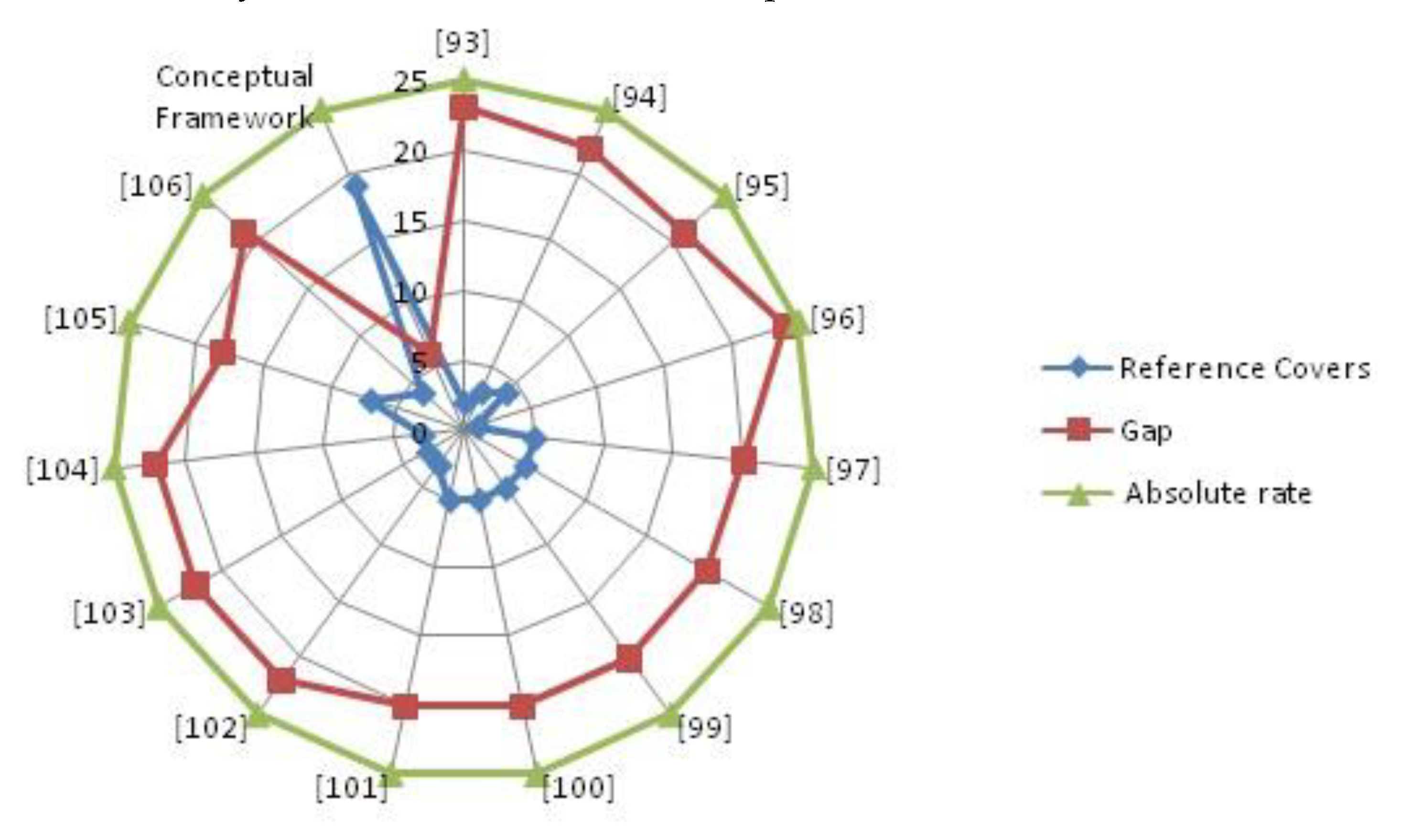

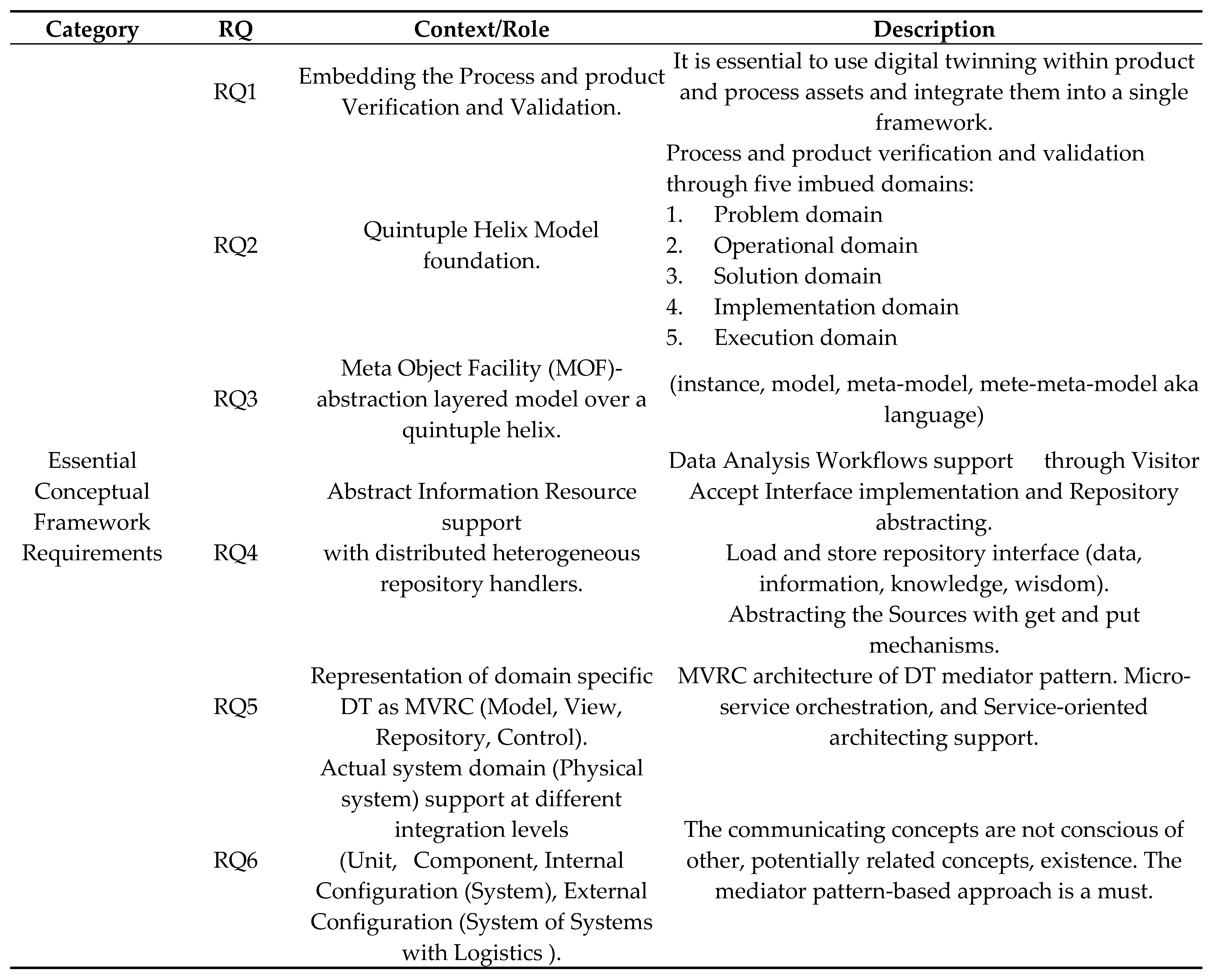

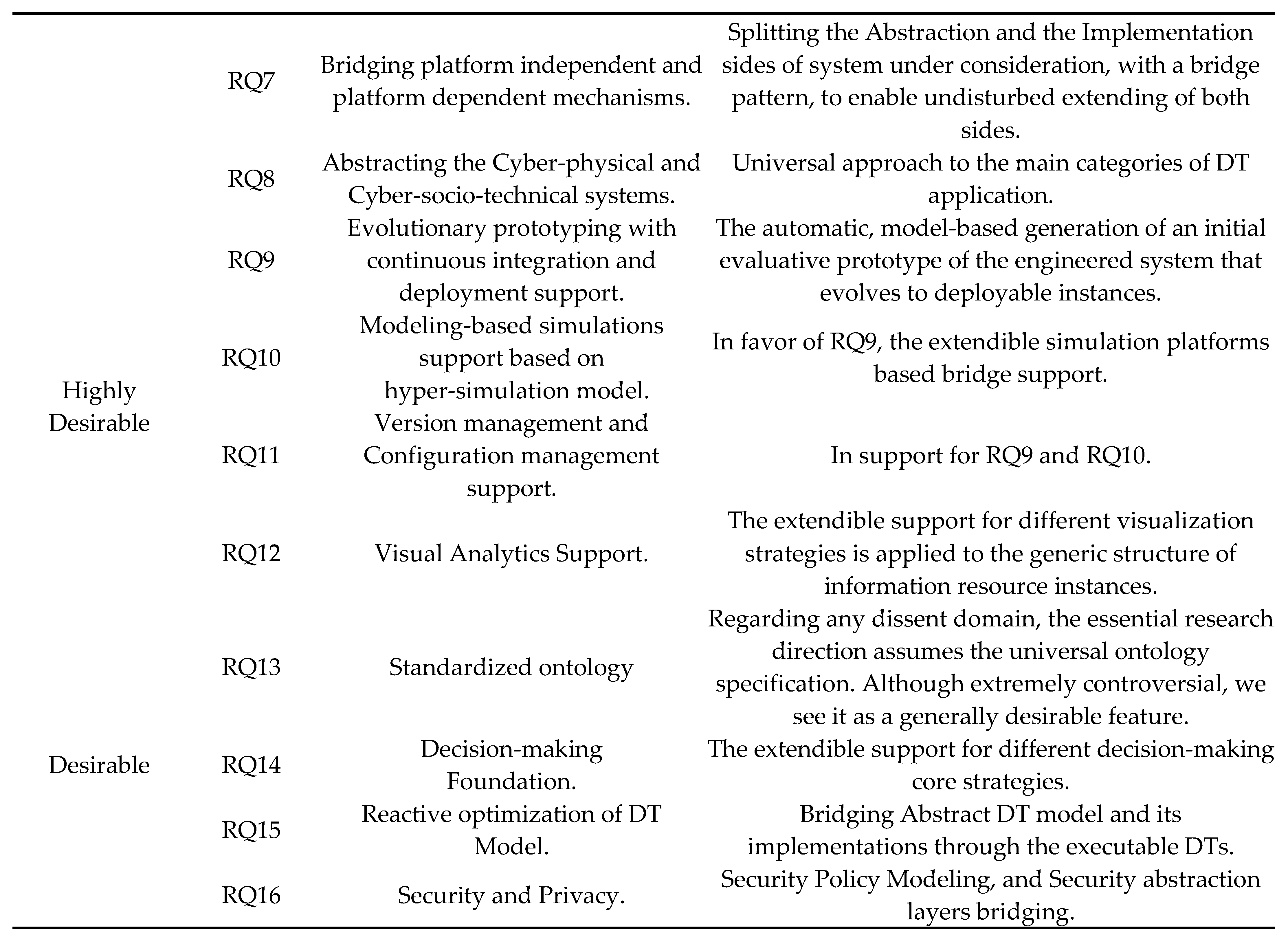

3.1. The Requirements Modeling and Specification

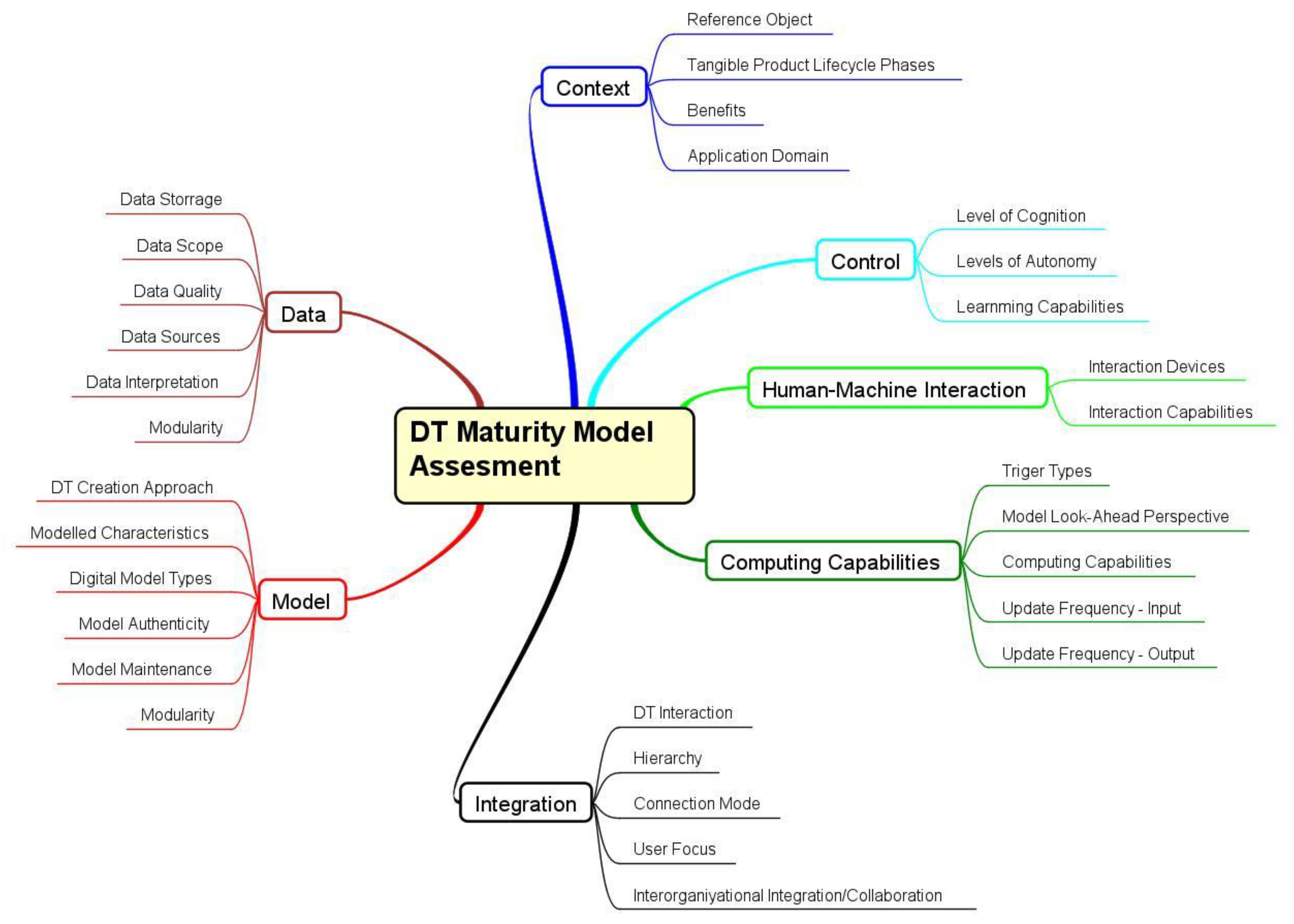

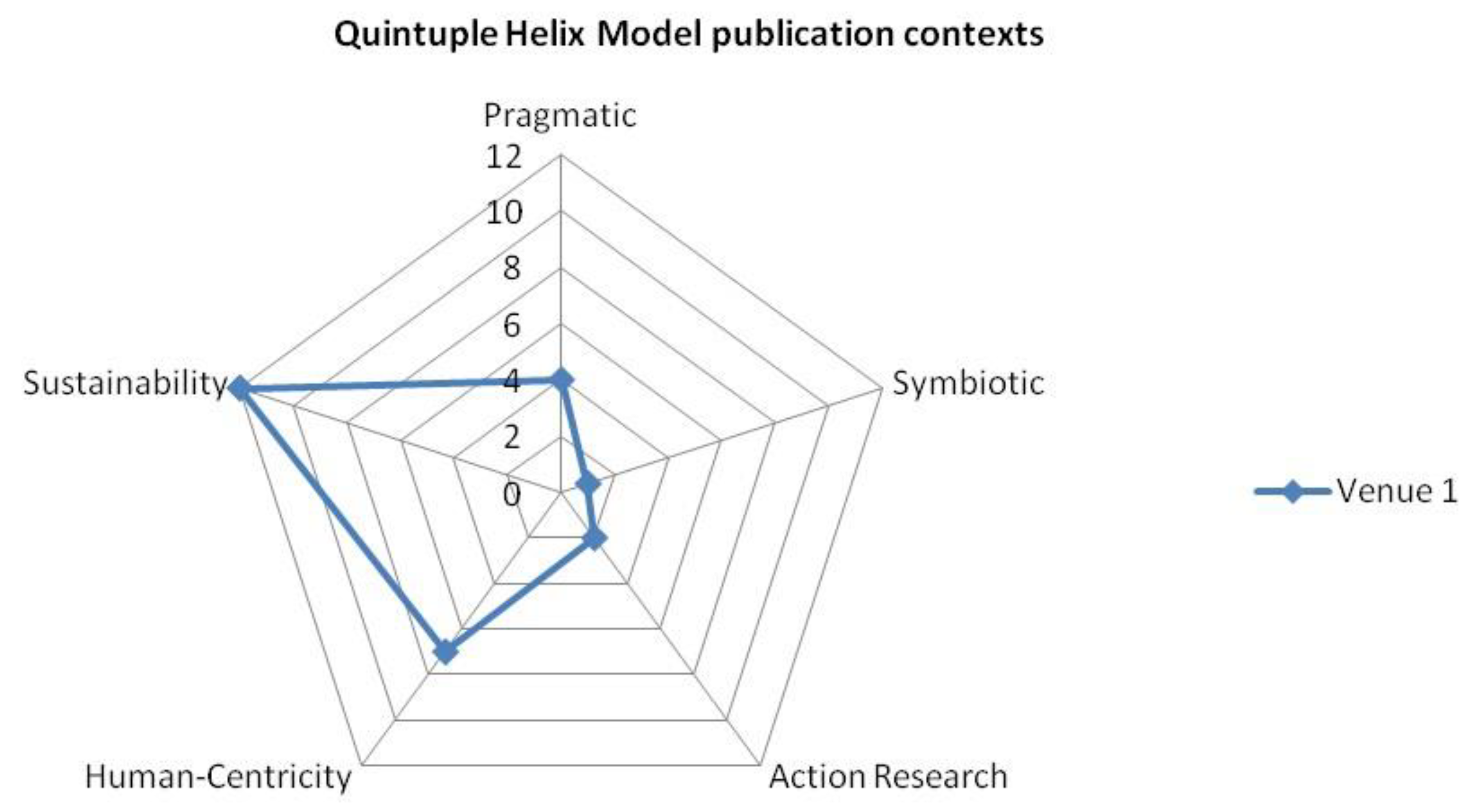

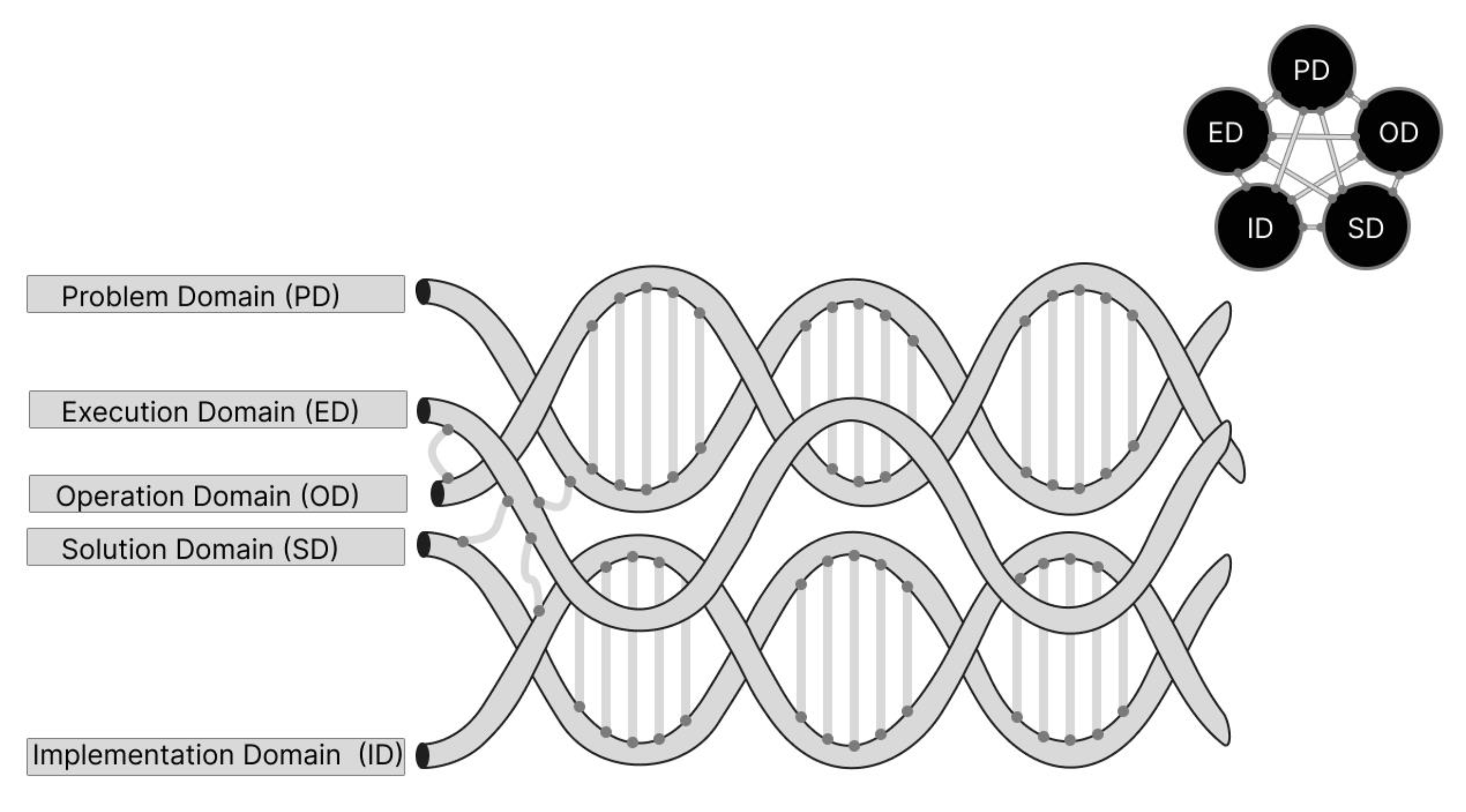

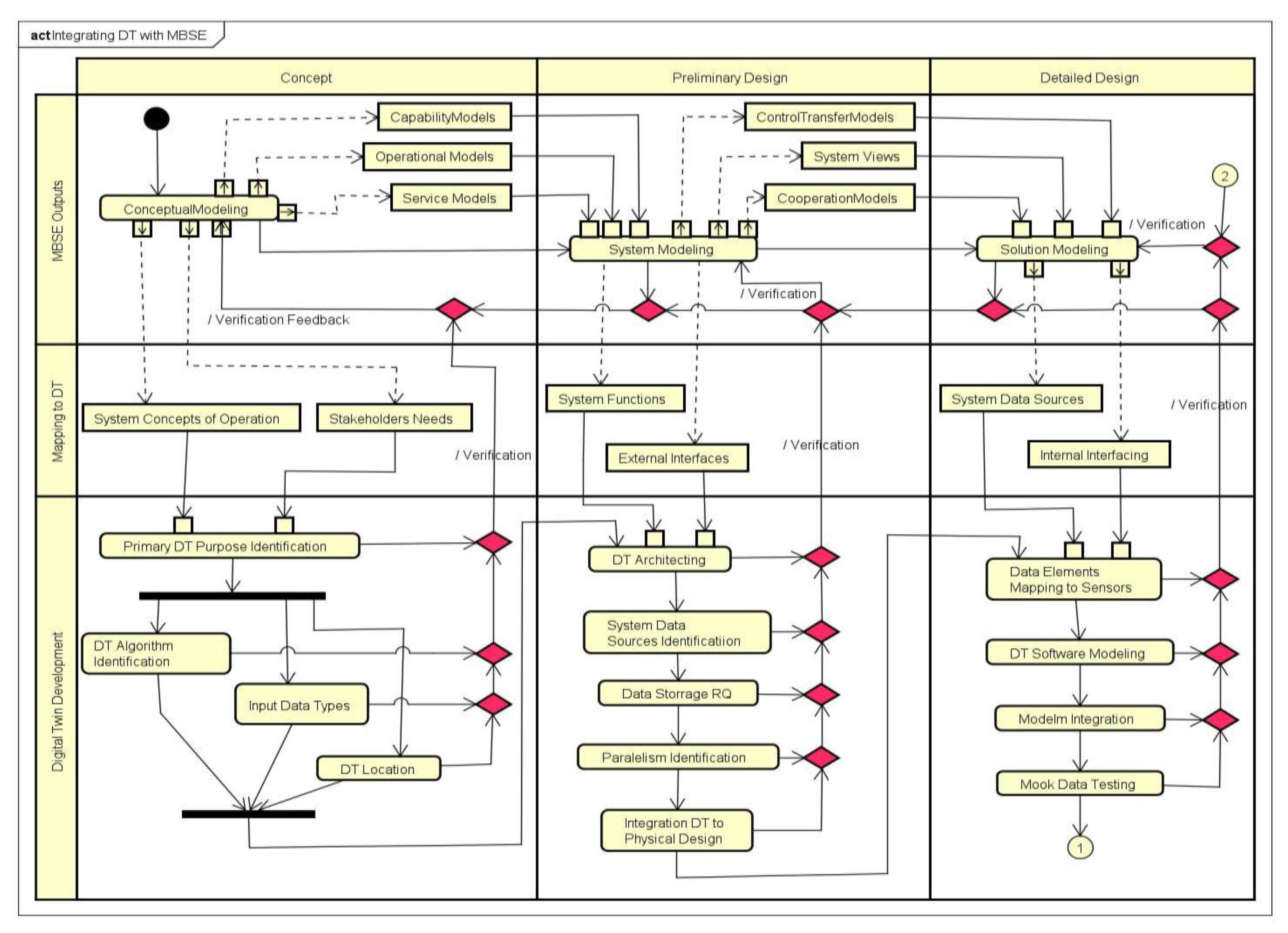

3.2. Quintuple Helix Foundation of DT Verification and Validaion Conceptual Framework

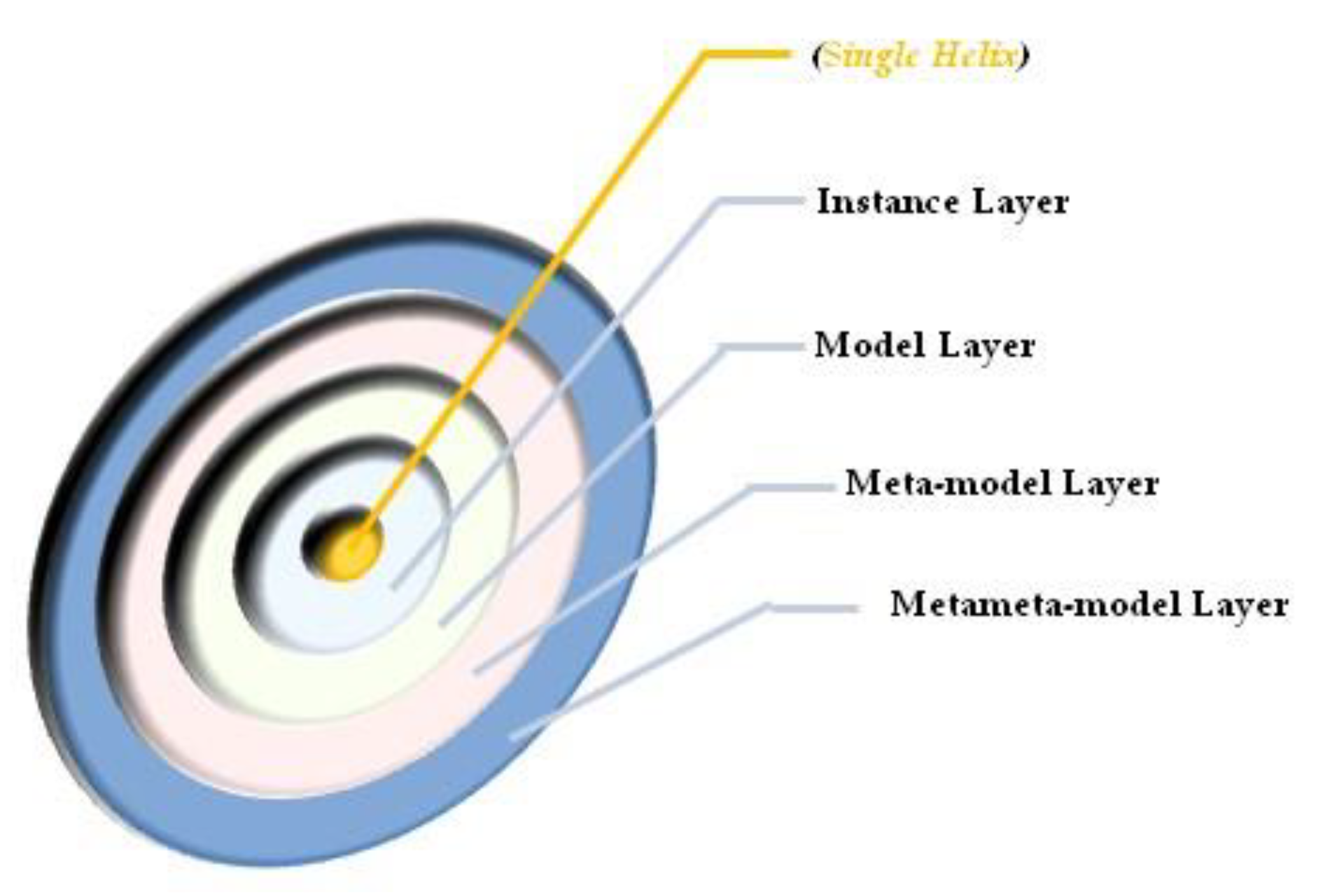

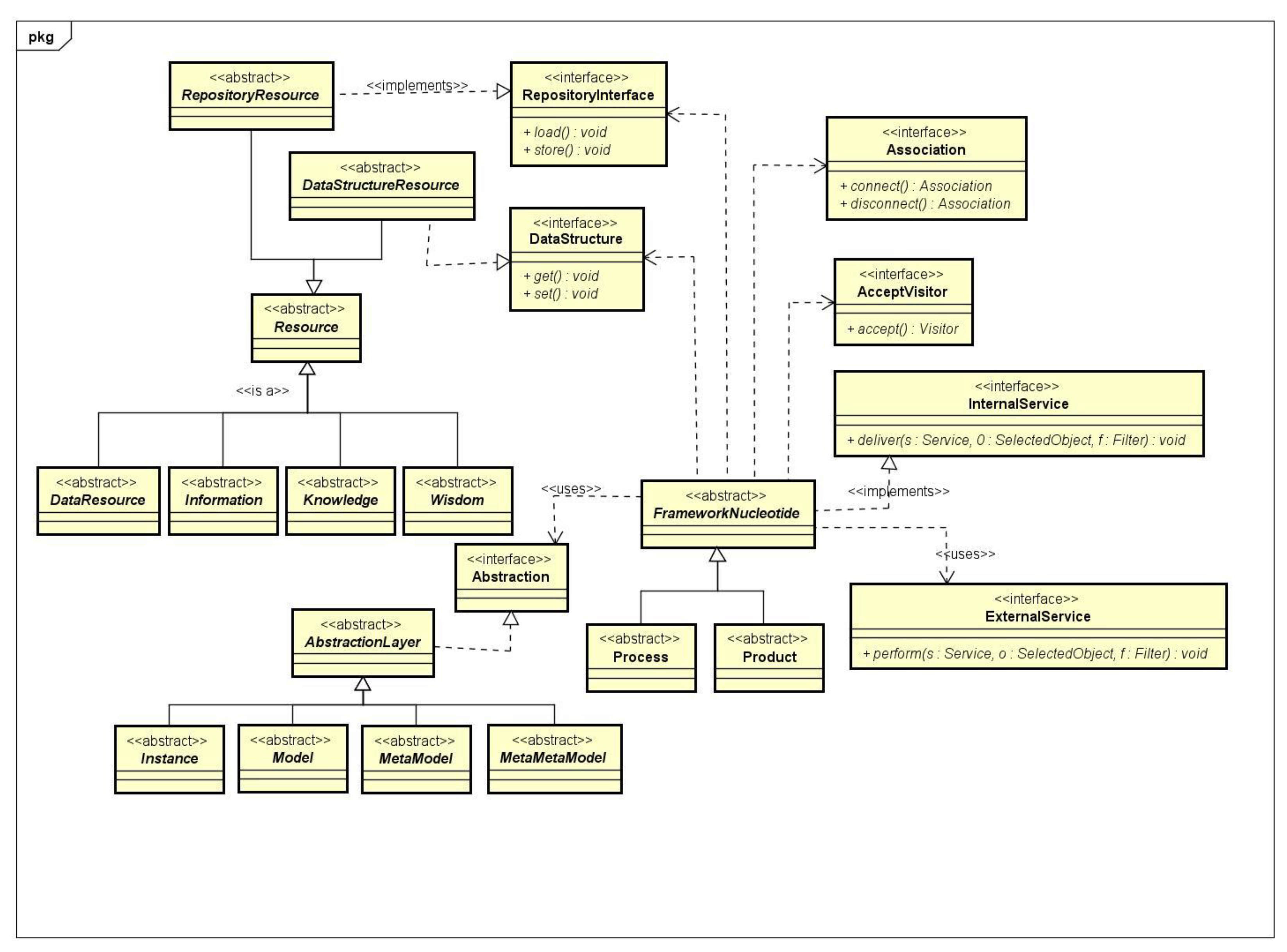

- Abstraction Interface - that bridges the modeling abstraction layers (Instance, Model, Meta-model, and Meta-meta-model) ;

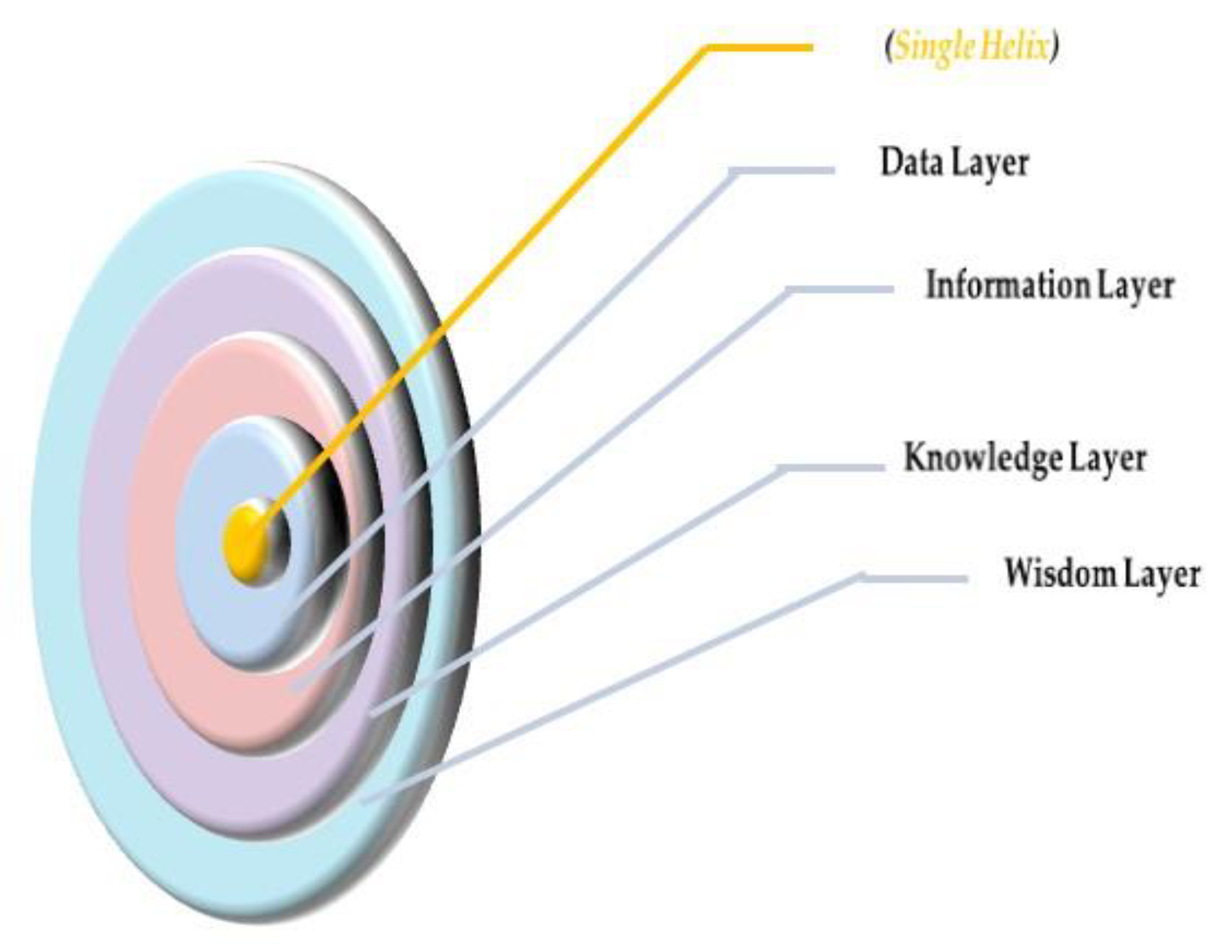

- Data Structure Interface - that bridges the Data Structure Resource, a complex abstract concept encapsulating dynamic Resource collection representing Data, Information, Knowledge, or Wisdom abstractions;

- Repository Interface - that bridges the Repository Resource, a complex abstract concept encapsulating persistent Resource collection representing Data, Information, Knowledge, or Wisdom abstractions;

- Association Interface - that encapsulates the connectivity mechanisms (connect and disconnect services);

- Repository Interface - that bridges the Repository Resource, a complex abstract concept encapsulating persistent Resource collection representing Data, Information, Knowledge, or Wisdom abstractions;

- Association Interface - that encapsulates the connectivity mechanisms (connect and disconnect services);

- Accept Visitor Interface - that enables the hosting of external, visiting, set of services attached to the Framework Nucleotide Instance;

- Internal Service Interface - that enables the formation of an extendible set of internally implemented services, accessible through referencing the universal abstract method implemented by an arbitrary implementer deliver(s: Service, o: SelectedObject, f: Filter). Semantically, run a service (s: Service) on a selected object (o: SelectedObject) and restrict the delivery with security and privacy policy-based dynamic filtering (f: Filter); and

- External Service Interface - that enables access to externally offered services by referencing the universal abstract method implemented by an arbitrary external implementer to perform(s: Service, o: SelectedObject, f: Filter). Semantically, execute external service (s: Service) on the selected object (o: SelectedObject) and restrict the execution by the security and privacy policy-based dynamic filtering (f: Filter).

3.3. Quintuple Helix Conceptual Framework for DT Verification and Validation Spots

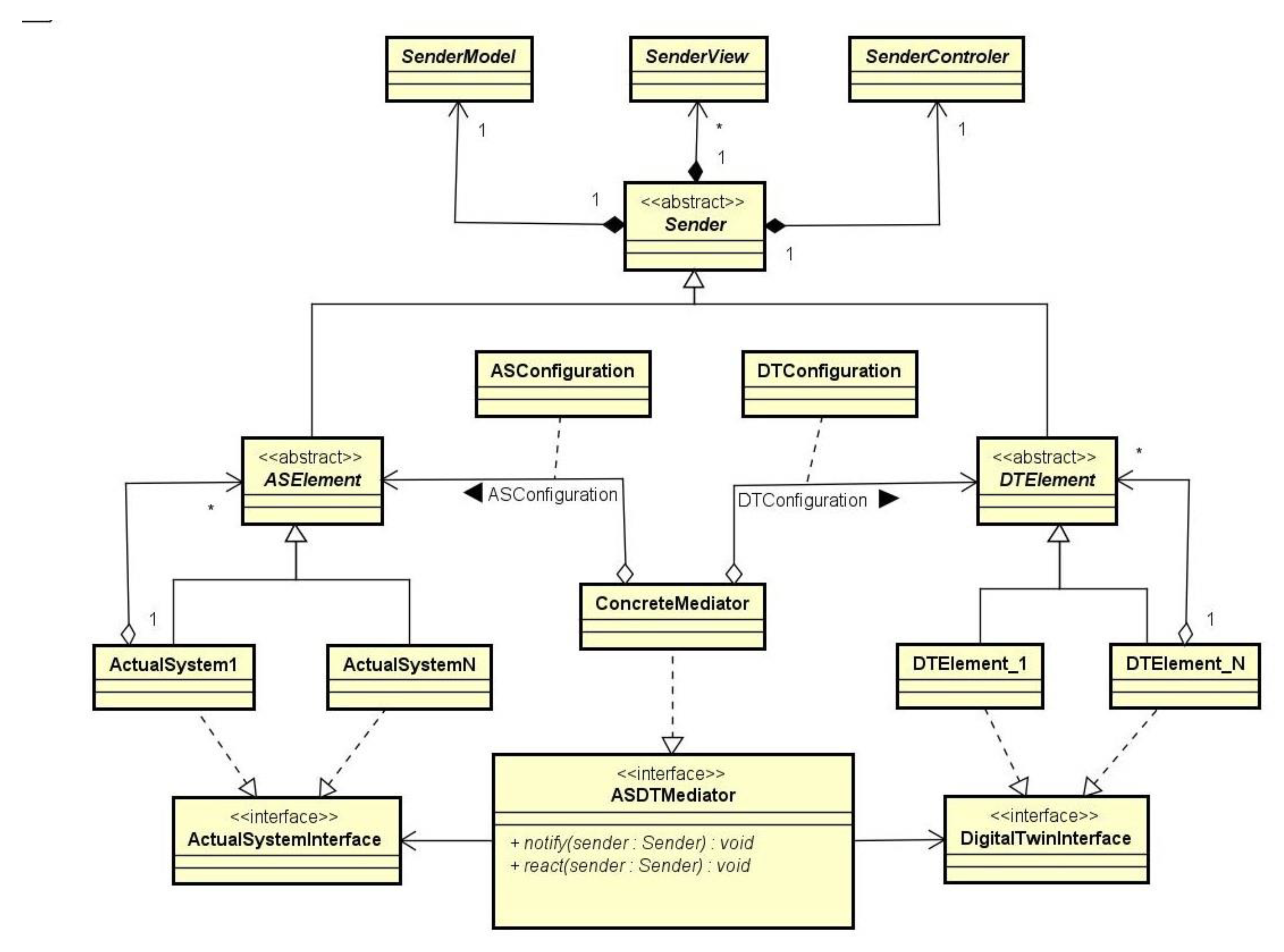

3.4. Quintuple Helix Conceptual Framework Mediation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- the Digital Twin Consortium's Digital Twin Ecosystem Capabilities Periodic Table, containing a systematic collection of referent capabilities and the associated semantics;

- the generative potentials of the DNA helix model with the built-in combinatorial complexity replicating within two back-bones coupled by four-dimensional nucleotides;

- the unified conceptualization approach to reasoning about framework entities and stages that relays on applied MOF model to abstracting framework resources;

- · the standards and standardization support extendibility; and

- Bridging of the abstract specification and the diverse repertoire of implementation platforms favoring the heterogeneity and harmonization of specification, development, modeling, implementation, and execution platforms involved.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johan Cederbladh. Towards Early Validation and Verification of System Behavior With Heterogeneous Models in Systems Engineering, PhD Thesis, Mälardalen University Press Licentiate Theses No. 352, School of Innovation, Design, and Engineering, 2024, ISBN 978-91-7485-633-0, ISSN 1651-9256, Printed by E-Print AB, Stockholm, Sweden.

- Lavi E; Reich Y. Cross-disciplinary system value overview towards value-oriented design. Research in Engineering Design - Theory, Applications, and Concurrent Engineering. 2024 Jan;35(1):1-20. [CrossRef]

- Johan Cederbladh; Antonio Cicchetti; Jagadish Suryadevara. Early Validation and Verification of System Behaviour in Model-based Systems Engineering: A Systematic Literature Review. ACM Transactions on Software Engineering and Methodology. 33, 3, Article 81 (March 2024), 67 pages. [CrossRef]

- Tao, Fei; He Zhang; Ang Liu; and Andrew YC Nee. Digital twin in industry: State-of-the-art., IEEE Transactions on industrial informatics 15, no. 4. 2018: pp.2405-2415. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Fuenmayor, E.; Hinchy, E.P.; Qiao, Y.; Murray, N.; Devine, D. Digital Twin: Origin to Future. Applied System Innovation. 2021, 4, 36. [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Liu, X.; Ripley, C.; Qian, M.; Liang, F.; Yu, W. Digital Twin—Cyber Replica of Physical Things: Architecture, Applications and Future Research Directions. Future Internet 2022, 14, 64. [CrossRef]

- Botín-Sanabria, D.M.; Mihaita, A.-S.; Peimbert-García, R.E.; Ramírez-Moreno, M.A.; Ramírez-Mendoza, R.A.; Lozoya-Santos, J.d.J. Digital Twin Technology Challenges and Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Remote Sensing. 2022, 14, 1335. [CrossRef]

- Muctadir, H.M.; Manrique Negrin; D.A., Gunasekaran; et al. Current trends in digital twin development, maintenance, and operation: an interview study. Software and Systems Modeling. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Angira Sharma; Edward Kosasih; Jie Zhang; Alexandra Brintrup; Anisoara Calinescu. Digital Twins: State of the art theory and practice, challenges, and open research questions, Journal of Industrial Information Integration, Volume 30, 2022, 100383,ISSN 2452-414X. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ji, P.; Ma, H.; Xing, L. A Comprehensive Review of Digital Twin from the Perspective of Total Process: Data, Models, Networks and Applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 8306. [CrossRef]

- Bickford, J; Van Bossuyt, DL; Beery, P; Pollman, A. Operationalizing digital twins through model-based systems engineering methods. Systems Engineering. 2020;1–27. [CrossRef]

- Deantoni, J. ; Muñoz, P. ; Gomes, C. ; Verbrugge, C. ; Mittal, R. ; Heinrich, R.; Bellis, S. ; Vallecillo, A. Quantifying and combining uncertainty for improving the behavior of Digital Twin Systems. ArXiv,2024,2024. [CrossRef]

- Madni, A.M.; Madni, C.C.; Lucero, S.D. Leveraging Digital Twin Technology in Model-Based Systems Engineering. Systems 2019, 7, 7. [CrossRef]

- J.-F. Uhlenkamp; J. B. Hauge; E. Broda; M. Lütjen; M. Freitag; K. -D. Thoben. Digital Twins: A Maturity Model for Their Classification and Evaluation, in IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 69605-69635, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Boy, G. A. ; Masson, D. ; Durnerin, É. ; Morel, C. PRODEC for human systems integration of increasingly autonomous systems. Systems Engineering, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Alessio Baratta; Antonio Cimino; Francesco Longo; Letizia Nicoletti. Digital twin for human-robot collaboration enhancement in manufacturing systems: Literature review and direction for future developments, Computers & Industrial Engineering, Volume 187,2024,109764,ISSN 0360-8352. [CrossRef]

- J. Autiosalo; J. Vepsäläinen; R. Viitala; K. Tammi. A Feature-Based Framework for Structuring Industrial Digital Twins, In IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 1193-1208, 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Ferko; A. Bucaioni; M. Behnam. Architecting Digital Twins, in IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 50335-50350, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ilin I; Levina A; Borremans A; Kalyazina S. Enterprise Architecture Modeling in Digital Transformation Era. In Energy management of municipal transportation facilities and transport , 2019 Dec 10, (pp.124-142). Springer International Publishing, (Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Anastasia-Levina/publication/344003444_Enterprise_Architecture_Modeling_in_Digital_Transformation_Era/links/602ba7a892851c4ed575714c/Enterprise-Architecture-Modeling-in-Digital-Transformation-Era.pdf).

- Steindl, G.; Kastner,W. Semantic Microservice Framework for Digital Twins. Applied Science. 2021, 11, 5633. [CrossRef]

- RAMI 4.0 Reference Architectural Model for Industrie 4.0, (Accesed on 10 July 2024. https://www.isa.org/intech-home/2019/march-april/features/rami-4-0-reference-architectural-model-for-industr).

- Ali Gharaei; Jinzhi Lu; Oliver Stoll; Xiaochen Zheng; Shaun West, et al. Systems Engineering Approach to Identify Requirements for Digital Twins Development, IFIP International Conference on Advances in Production Management Systems (APMS), Aug 2020, Novi Sad, Serbia. pp.82-90. hal-03630920. [CrossRef]

- Michael Grieves; John Vickers. Digital Twin: Mitigating Unpredictable, Undesirable Emergent Behavior in Complex Systems, Chapter in F.-J. Kahlen et al. (eds.), Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems, Springer International Publishing, 2017, pp.111-112. [CrossRef]

- A. Barbie; and W. Hasselbring. From Digital Twins to Digital Twin Prototypes: Concepts, Formalization, and Applications, in IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 75337-75365, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yan Zang. Artificial Intelligence for Digital Twin. In Digital Twin Architectures, Networks and Applications; Springer: Gewerbestrasse 11, 6330 Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 23–39. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Daniell, J; Alam, S. B. Improved generalization with deep neural operators for engineering systems: Path towards digital twin. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 131, 2024, 107844. [CrossRef]

- Wael Fatnassi. Formal Verification of AI-Controlled Cyber-Physical Systems Using Polynomial Approximations: Constraints Solver, Model Checkers, and Applications, PhD Dissertation, University of California Irvine, 2024, Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/41t4b6w9 (accessed on 25 Jun 2024).

- Shadab, N.; Cody, T.; Salado, A.; Beling, P. A Systems-Theoretical Formalization of Closed Systems. ArXiv. /abs/2311.10786, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Renkhoff; K. Feng; M. Meier-Doernberg; A. Velasquez; and H. H. Song. A Survey on Verification and Validation, Testing and Evaluations of Neurosymbolic Artificial Intelligence,. in IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Löcklin; M. Müller; T. Jung, N. Jazdi; D. White; and M. Weyrich, Digital Twin for Verification and Validation of Industrial Automation Systems – a Survey, 2020 25th IEEE International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), Vienna, Austria, 2020, pp. 851-858. [CrossRef]

- Nazakat Ali; Sasikumar Punnekkat; Abdul Rauf. Modeling and safety analysis for collaborative safety-critical systems using hierarchical colored Petri nets, Journal of Systems and Software, Volume 210, 2024, 111958, ISSN 0164-1212. [CrossRef]

- Felicien Ihirwe; Davide Di Ruscio; Katia Di Blasio; Simone Gianfranceschi; Alfonso Pierantonio. Supporting model-based safety analysis for safety-critical IoT systems,Journal of Computer Languages,Volume 78,2024,101243,ISSN 2590-1184. [CrossRef]

- Daisuke Ishii. A Hypergraph-based Formalization of Hierarchical Reactive Modules and a Compositional Verification Method, 16 Mar 2024. arXiv:2403.10919v1. [CrossRef]

- Pe´rez-Gaspar M; Gomez J; Ba´rcenas E; Garcia F. A fuzzy description logic based IoT framework: Formal verification and end user programming. PLoS ONE 19(3): e0296655.,2024. [CrossRef]

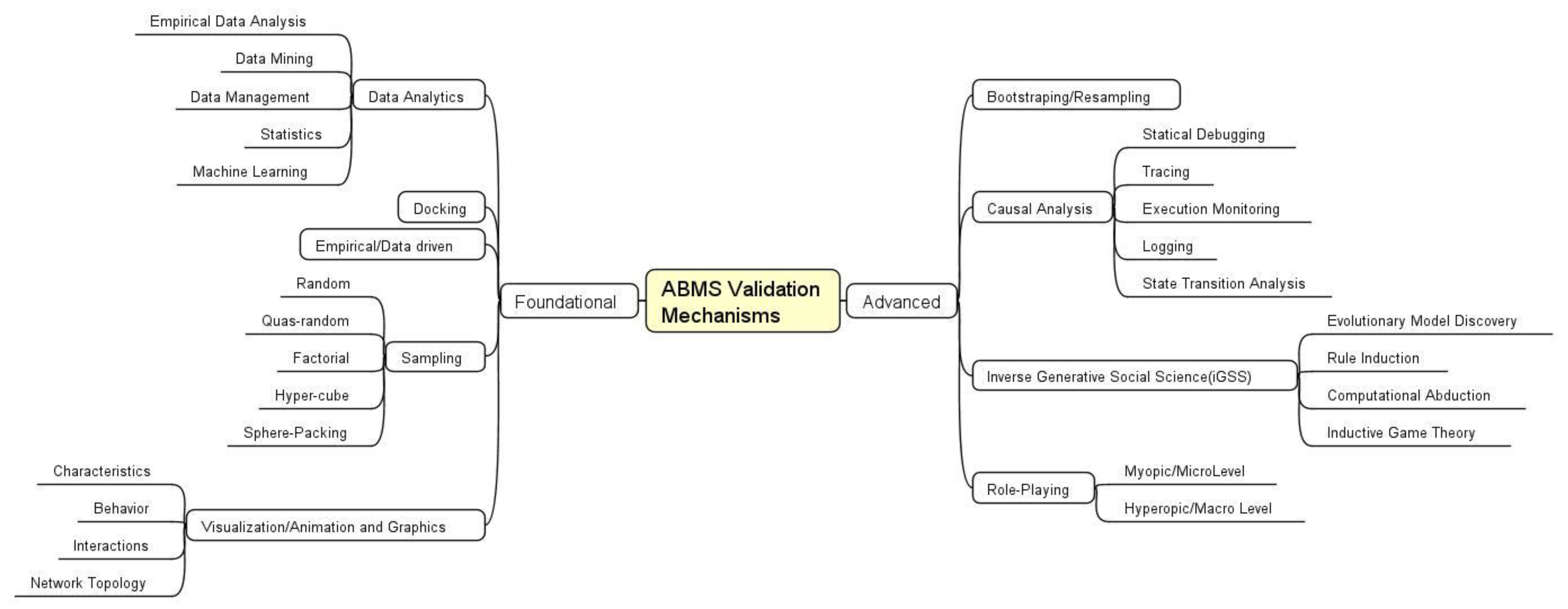

- Collins, Andrew; Koehler, Matthew ; Lynch, Christopher. Methods That Support the Validation of Agent-Based Models: An Overview and Discussion. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation 27 (1) 11,2024. [CrossRef]

- E. Y. Hua; S. Lazarova-Molnar; D. P. Francis. Validation of Digital Twins: Challenges and Opportunities, 2022 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC), Singapore, 2022, pp. 2900-2911. [CrossRef]

- Perišić A; Perišić B. The Foundation for Open Component Analysis: A System of Systems Hyper Framework Model. Chapter, In Advances in Principal Component Analysis. IntechOpen; 2022. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Xin Qin; Yuan Xia; Aditya Zutshi; Chuchu Fan; Jyotirmoy V. Deshmukh. Statistical Verification using Surrogate Models and Conformal Inference and a Comparison with Risk-Aware Verification. ACM Trans. Cyber-Phys. Syst. 8, 2, Article 22 (April 2024), 25 pages. [CrossRef]

- Roos, C.; Biannic, J.-M. ; Evain, H. A new step towards the integration of probabilistic μ in the aerospace V&V process, CEAS Space Journal, vol. 16, no. 1, Springer, pp. 59–71, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni AU; Salado A; Xu P; Wernz C. An evaluation of the optimality of frequent verification for vertically integrated systems. Systems Engineering. 2021; 24: 17–33. [CrossRef]

- Zhan Ling; Yunhao Fang; Xuanlin Li; Zhiao Huang; Mingu Lee; Roland Memisevic; Hao Su. Deductive verification of chain-of-thought reasoning. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS '23). Curran Associates Inc., Red Hook, NY, USA, 2024,Article 1580, 36407–36433.

- Marisol García-Valls; Alejandro M. Chirivella-Ciruelos. CoTwin: Collaborative improvement of digital twins enabled by blockchain, Future Generation Computer Systems, Volume 157,2024, Pages 408-421,ISSN 0167-739X. [CrossRef]

- Randhir Kumar; Ahamed Aljuhani; Danish Javeed; Prabhat Kumar; Shareeful Islam; A.K.M. Najmul Islam. Digital Twins-enabled Zero Touch Network: A smart contract and explainable AI integrated cyber-security framework, Future Generation Computer Systems, Volume 156,2024,Pages 191-205,ISSN 0167-739X. [CrossRef]

- Jonas Friederich; Deena P. Francis; Sanja Lazarova-Molnar; Nader Mohamed. A framework for data-driven digital twins of smart manufacturing systems, Computers in Industry, Volume 136, 2022,103586,ISSN 0166-3615. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Hangbin;Liu,Tianyuan;Liu,Jiayu;Bao, Jinsong.Visual analytics for digital twins: a conceptual framework and case study Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing,Volum 35, Issue 4,pp.1671-1686. [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Guo, Y.; Cui, K.; Wu, P.; Fang, W.; Liu, D. Multidimensional Data Modeling and Model Validation for Digital Twin Workshop. ASME. Journal of. Computing and Information Science in Engineering,2021, 21(3): 031005. [CrossRef]

- Schintke, F.; De Mecquenem, N.; Frantz, D.; Guarino, V. E.; Hilbrich, M.;Lehmann, F.;Sattler, R.; Sparka, J. A.; Speckhard, D.; Stolte, H.;Vu, A. D.; Leser, U. Validity Constraints for Data Analysis Workflows. ArXiv. /abs/2305.08409. [CrossRef]

- Nextflow. https://www.nextflow.io/docs/latest/index.html (accessed on 11 of July 2024).

- Apache Groovy. https://groovy-lang.org/, (accessed on 11 of July 2024).

- Gradle. https://gradle.org/releases/, (accessed on 11 of July 2024).

- Grails. https://docs.grails.org/6.2.0/guide/single.html, (accessed on 11 of July 2024).

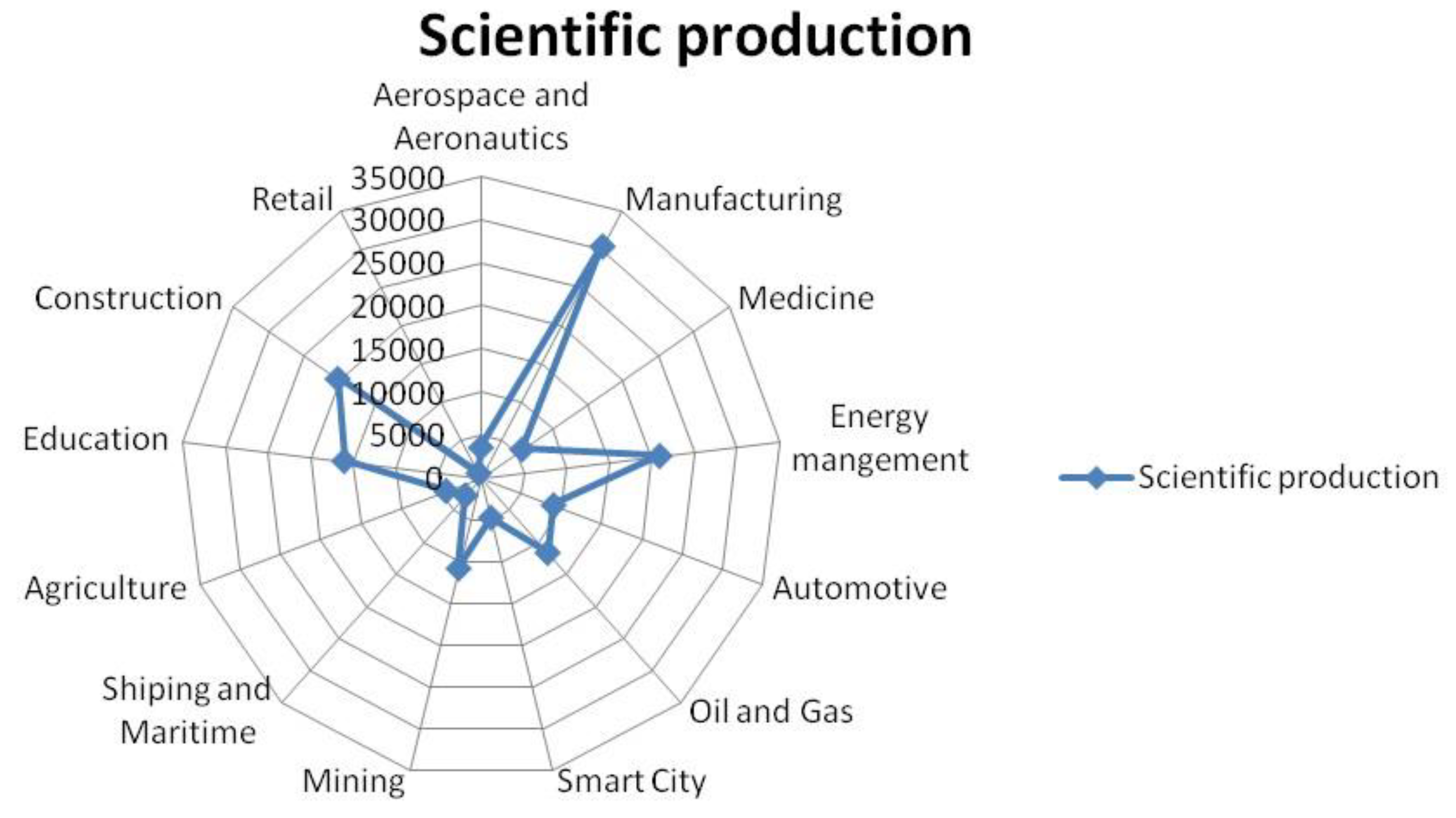

- Singh, M.; Srivastava, R.; Fuenmayor, E.; Kuts, V.; Qiao, Y.; Murray, N.; Devine, D. Applications of Digital Twin across Industries: A Review. Applied Science, 2022, 12, 5727. [CrossRef]

- Harel, D. ; Yerushalmi, R. ; Marron, A; et al. Categorizing methods for integrating machine learning with executable specifications. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 67, 111101, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, M. ; Lehner, D. ; Sindelar, R. ; Wimmer, M. Towards Reactive Planning with Digital Twins and Model-Driven Optimization. In: Margaria, T., Steffen, B. (eds) Leveraging Applications of Formal Methods, Verification and Validation. Practice. ISoLA 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 13704. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Kamburjan, Eduard; Crystal Chang Din; Rudolf Schlatte; S. Lizeth Tapia Tarifa; Einar Broch Johnsen. Twining-by-construction: ensuring correctness for self-adaptive digital twins. In International Symposium on Leveraging Applications of Formal Methods, pp. 188-204. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022.

- S. Fur; M. Heithoff; J. Michael; L. Netz; J. Pfeiffer; B. Rumpe; A. Wortmann. Sustainable Digital Twin Engineering for the Internet of Production. In: Digital Twin Driven Intelligent Systems and Emerging Metaverse, E. Karaarslan, Ö. Aydin, Ü. Cali, M. Challenger (Eds.), pp. 101-121, Springer Nature Singapore, April 2023. www.se-rwth.de/publications/.

- Bárkányi, Á.; Chován, T.; Németh, S.; Abonyi, J. Modeling for Digital Twins—Potential Role of Surrogate Models. Processes 2021, 9,476. [CrossRef]

- Papacharalampopoulos, A.; Giannoulis, C.; Stavropoulos, P.; Mourtzis, D. A Digital Twin for Automated Root-Cause Search of Production Alarms Based on KPIs Aggregated from IoT. Applied Science, 2020, 10, 2377. [CrossRef]

- Wärmefjord, K.; Söderberg, R.; Schleich, B.; Wang, H. Digital Twin for Variation Management: A General Framework and Identification of Industrial Challenges Related to the Implementation. Applied Science, 2020, 10, 3342. [CrossRef]

- Sepasgozar, S.M.E. Differentiating Digital Twin from Digital Shadow: Elucidating a Paradigm Shift to Expedite a Smart, Sustainable Built Environment. Buildings 2021, 11, 151. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, N.; Liu, Z.; Mu, E. Construction Theory for a Building Intelligent Operation and Maintenance System Based on Digital Twins and Machine Learning. Buildings 2022, 12, 87. [CrossRef]

- Hu,W.; Lim, K.Y.H.; Cai, Y. Digital Twin and Industry 4.0 Enablers in Building and Construction: A Survey. Buildings,2022, 12, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Galyna Ryzhakova; Oksana Malykhina; Vadym Pokolenko; Oksana Rubtsova; Oleksandr Homenko; Iryna Nesterenko; Tetyana Honcharenko. Construction Project Management with Digital Twin Information System, International Journal of Emerging Technology and Advanced Engineering, Volume 12, Issue 10, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Omrany, H.; Al-Obaidi, K.M.; Husain, A.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A. Digital Twins in the Construction Industry: A Comprehensive Review of Current Implementations, Enabling Technologies, and Future Directions. Sustainability, 2023, 15, 10908. [CrossRef]

- Roullier, B.; McQuade, F.; Anjum, A. et al. Automated visual quality assessment for virtual and augmented reality based digital twins. Journal of Cloud Computing 13, Article number 51, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Eric VanDerHorn; Sankaran Mahadevan. Digital Twin: Generalization, characterization and implementation, Decision Support Systems,Volume 145, 2021,113524,ISSN 0167-9236. [CrossRef]

- J. Moyne et al., A Requirements Driven Digital Twin Framework: Specification and Opportunities, in IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 107781-107801, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Human; A.H. Basson; K. Kruger. A design framework for a system of digital twins and services, Computers in Industry,Volume 144,2023,103796,ISSN 0166-3615. [CrossRef]

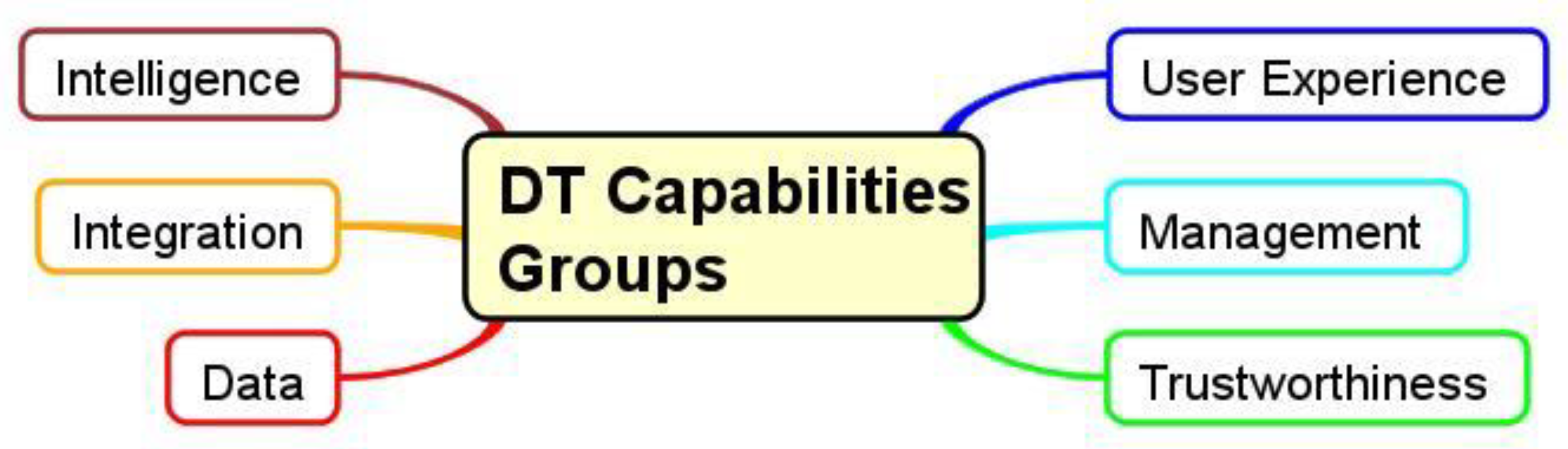

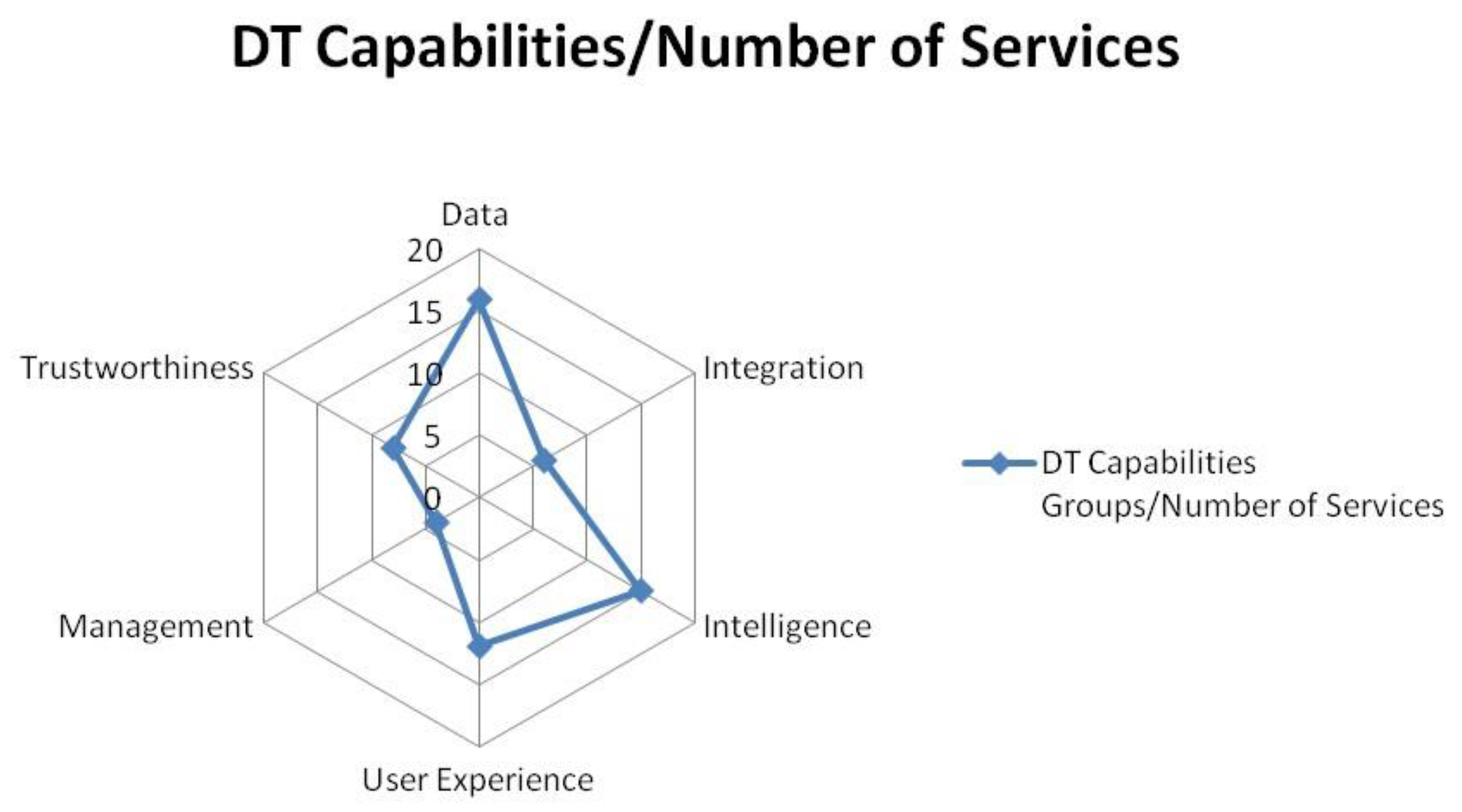

- Digital Twins Consorcium, Digital Twin Capabilities Periodic Table. https://www.digitaltwinconsortium.org/initiatives/capabilities-periodic-table/, (accessed on 7 of July 2024).

- Taratori, R.; Rodriguez-Fiscal, P.; Pacho, M.A.; Koutra, S.; Pareja-Eastaway, M.; Thomas, D. Unveiling the Evolution of Innovation Ecosystems: An Analysis of Triple, Quadruple, and Quintuple Helix Model Innovation Systems in European Case Studies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7582. [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G; Campbell, D.F.J; Grigoroudis, E. Helix Trilogy: the Triple, Quadruple, and Quintuple Innovation Helices from a Theory, Policy, and Practice Set of Perspectives. Journal of Knowledge Economy 13, 2272–2301, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues-Ferreira, A., Afonso, H., Mello, J. A., & Amaral, R. Creative economy and the quintuple helix innovation model: a critical factors study in the context of regional development. Creativity Studies, 16(1), 158–177, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kunwar, R. R.; Ulak, N. Extension of the Triple Helix to Quadruple to Quintuple Helix Model. Journal of APF Command and Staff College, 7(1), 241–280, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Martini Elvira. A quintuple helix model for foresight: Analyzing the developments of digital technologies in order to outline possible future scenarios, Frontiers in Sociology. 7:1102815, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kholiavko, N.; Grosu, V.; Safonov, Y.; Zhavoronok, A.; Cosmulese, C. G. QUINTUPLE HELIX MODEL: INVESTMENT ASPECTS OF HIGHER EDUCATION IMPACT ON SUSTAINABILITY. Management Theory and Studies for Rural Business and Infrastructure Development, 43(1), 111–128, 2021. [CrossRef]

- González-Carrasco V; Robina-Ramírez R; Gibaja-Romero D-E; Sánchez-OroSánchez M. The Quintuple Helix Model: Cooperation system for a sustainable electric power industry in Mexico. Front. Sustain. Energy Policy 1:1047675, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hadi Naghavi pour; Jasmine Begum; Vee Meng; et al. Pragmatic and Symbiotic Quintuple Helix Model Mitigating Emerging Technologies Disruption: A Vision, Strategy, and Policy. TechRxiv. February 06, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mutian He; Tianqing Fang; Weiqi Wang; Yangqiu Song. Acquiring and modeling abstract commonsense knowledge via conceptualization, Artificial Intelligence,Volume 333,2024,104149,ISSN 0004-3702. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.R; Sarkadi, Ş. Reflective Artificial Intelligence, Minds & Machines 34, 14,2024. [CrossRef]

- OMG Meta Object Facility (MOF) Core Cpecification, Version 2.5.1., document number : formal/2019-10-01, October 2019. https://www.omg.org/spec/MOF/2.5.1/PDF.

- Digital Twin Definition Language. https://azure.github.io/opendigitaltwins-dtdl/DTDL/v2/DTDL.v2.html, (accessed on 20 of June 2024).

- Pioneering the international standards and standardization. https://www.iec.ch/blog/150th-anniversary-father-international-standardization (accessed on 16 of July 2024).

- Guodong Shao. Use Case Scenarios for Digital Twin Implementation Based on ISO 23247, NIST, US Department of Commerce, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Guodong Shao; Joe Hightower; William Schindel. Credibility consideration for digital twins in manufacturing, Manufacturing Letters,Volume 35,2023, Pages 24-28,ISSN 2213-8463. [CrossRef]

- Anaya, V.; Alberti, E.; Scivoletto, G. ; A Manufacturing Digital Twin Framework. In: Soldatos, J. (eds) Artificial Intelligence in Manufacturing. Springer, Cham., pp. 181-193, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Caiza, G.; Sanz, R. Immersive Digital Twin under ISO 23247 Applied to Flexible Manufacturing Processes. Applied Science.2024, 14, 4204. [CrossRef]

- OPC Foundation, The Industrial Operability Standards. https://opcfoundation.org/ (accessed on 16 of July 2024).

- Cavalieri, S.; Gambadoro, S. Proposal of Mapping Digital Twins Definition Language to Open Platform Communications Unified Architecture. Sensors 2023, 23, 2349. [CrossRef]

- Axel Busboom. Automated generation of OPC UA information models — A review and outlook, Journal of Industrial Information Integration,Volume 39,2024,100602,ISSN 2452-414X. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C.; Volz, F.; Stojanovic, L.; Sutschet, G. Increasing Interoperability between Digital Twin Standards and Specifications: Transformation of DTDL to AAS. Sensors 2023, 23, 7742. [CrossRef]

- Qinglin Qi; et al. Enabling technologies and tools for digital twin,Journal of Manufacturing Systems, Volume 58, Part B,2021,Pages 3-21,ISSN 0278-6125. [CrossRef]

- Lehner, D.; Pfeiffer, J.; Tinsel, E. F.; Strljic, M. M.; Sint, S.; Vierhauser, M.; Wimmer, M. Digital twin platforms: requirements, capabilities, and future prospects. IEEE Software, 39(2), 53-61.,2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Moyne; et al. A Requirements Driven Digital Twin Framework: Specification and Opportunities. in IEEE Access, Vol. 8, pp. 107781-107801, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Duan H, Gao S, Yang X and Li Y. The development of a digital twin concept system [version 2; peer review: 3 approved with reservations]. Digital Twin 2023, 2:10. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Zhao, Y., Yao, P., Zeng, F., Zhan, B., & Ren, KKBX: Verified Model Synchronization via Formal Bidirectional Transformation. ArXiv, 2024, abs/2404.18771. [CrossRef]

- Flammini Francesko. Digital Twins as run-time predictive models for the resilience of cyber-physical systems: a conceptual framework, Philosophical Transactions. R.Soc.A.379,20200369, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Dahmen, U., Osterloh, T. and Roßmann, J., Verification and validation of digital twins and virtual testbeds. Int J Adv Appl Sci, 11(1), pp.47-64, 2022.

- C. Human; A.H. Basson; K. Kruger. A design framework for a system of digital twins and services, Computers in Industry, Volume 144,2023,103796,ISSN 0166-3615. [CrossRef]

- Igiri Onaji; Divya Tiwari; Payam Soulatiantork; Boyang Song; Ashutosh Tiwari. Digital twin in manufacturing: conceptual framework and casestudies, International Journal of Computer Integrated Manufacturing, 35:8, 831-858, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Negri, E.; Berardi, S.; Fumagalli, L.; Macchi, M. MES-integrated digital twin frameworks. Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 56, 58-71. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Hangbin Zheng; Tianyuan Liu; Jiayu Liu; Jinsong Bao. Visual analytics for digital twins: a conceptual framework and case study. J. Intell. Manuf. 35, 2024, 1671–1686. [CrossRef]

- Sabah Suhail; Rasheed Hussain; Raja Jurdak; Alma Oracevic; Khaled Salah; Choong Seon Hong; Raimundas Matulevičius. Blockchain-Based Digital Twins: Research Trends, Issues, and Future Challenges. ACM Computing Surveys, 54, 11s, Article 240, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. C. Balta; M. Pease; J. Moyne; K. Barton; D. M. Tilbury. Digital Twin-Based Cyber-Attack Detection Framework for Cyber-Physical Manufacturing Systems," in IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 1695-1712, April 2024.

- Jürgen Dobaj; Andreas Riel; Thomas Krug; Matthias Seidl; Georg Macher; Markus Egretzberger. Towards digital twin-enabled DevOps for CPS providing architecture-based service adaptation & verification at runtime. In Proceedings of the 17th Symposium on Software Engineering for Adaptive and Self-Managing Systems (SEAMS '22). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 132–143. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hugh Boyes; Tim Watson. Digital twins: An analysis framework and open issues, Computers in Industry, Volume 143,2022,103763, ISSN 0166-3615. [CrossRef]

- Worden, K.; Cross, E. J.; Barthorpe, R. J.; Wagg, D. J.; Gardner, P. On Digital Twins, Mirrors, and Virtualizations: Frameworks for Model Verification and Validation. ASME. ASME J. Risk Uncertainty Part B. September 2020; 6(3): 030902. [CrossRef]

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| F01 | Verification and Validation Framework |

| F02 | Digital Twin Development Framework |

| F03 | Integrated Framework |

| F04 | System of Digital Twins |

| F05 | Covers Specific Digital Twin Capability |

| F06 | Ontology Framework |

| F07 | Trustworthy (Security and Privacy) |

| F08 | Name Space and Definitions |

| F09 | Reference Architecture |

| F10 | Prototyping Support |

| F11 | Ilustrated with Case Studies |

| F12 | Model verification and validation |

| F13 | Bidirectional model synchronization |

| F14 | Simulations |

| F15 | Verification and validation of scenarios |

| F16 | Automatic verification and validation support |

| F17 | Digital Twins configuration |

| F18 | Data Integration |

| F19 | Service Oriented Architecture (SOA) |

| F20 | Entire Life Cycle Support |

| F21 | Decision making support |

| F22 | Analytics |

| F23 | Visualization |

| F24 | Extendibility |

| F25 | Generality (covering cyber-physical and socio-technical systems) |

| Referenced Frameworks | |||||||||||||||

| Feature | [93] | [94] | [95] | [96] | [97] | [98] | [99] | [100] | [101] | [102] | [103] | [104] | [105] | [106] | CF |

| F01 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ● |

| F02 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ● |

| F03 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ● |

| F04 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● |

| F05 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ○ |

| F06 | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ |

| F07 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| F08 | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ |

| F09 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● |

| F10 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● |

| F11 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ |

| F12 | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ |

| F13 | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● |

| F14 | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ● |

| F15 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● |

| F16 | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● |

| F17 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● |

| F18 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● |

| F19 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● |

| F20 | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● |

| F21 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● |

| F22 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ● |

| F23 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ● |

| F24 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● |

| F25 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● |

| 25 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).