1. Introduction

With the rapid growth of the Metaverse, companies are using Digital Twins (DT) to create a virtual world for their customers and employees. Hence, DTs are becoming the next breakthrough in digitization [

1,

2,

3], which have gained significant traction recently with applications across domains according to recent state-of-the-art reviews in agriculture [

4], automotive [

5], manufacturing [

6], construction [

7] and healthcare [

8]. DTs are virtual copies of systems that are built through fusion of high fidelity system models and data [

9,

10]. According to Grieves and Vickers [

11] a DT can be defined as "a set of virtual information constructs that fully describes a potential or actual physical manufactured product from the micro atomic level to the macro geometrical level. At its optimum, any information that could be obtained from inspecting a physical manufactured product can be obtained from its Digital Twin". Grieves [

11] characterized them as having three distinct spaces, namely, physical, communication and digital. In the physical space, the real space contains that actual system or process and operational technology infrastructure for capturing and manipulating it (i.e. sensors and actuators). The digital space houses a high-fidelity digital replica of the physical system or process which is able to simulate all aspects of it. The communication space allows for communication between the digital and physical spaces. Communication mode between the physical and virtual entities differentiates between a DT, digital shadow and digital model. In DTs, bi-directional real time data flow exists between the physical entity and the digital entity. In a digital shadow [

12] a one-way real-time data flows from the physical entity to the digital entity. In a digital model [

13,

14], no data flow occurs between the entities. These spaces and all their services were further detailed and presented in a layered reference architecture for DTs proposed in [

15], where Alam et al. [

16] identified four main functional layers: (i) data dissemination and acquisition, (ii) data management and synchronization, (iii) data modeling and additional services, and (iv) data visualization and accessibility.

DT can be used to improve the monitoring, performance, efficiency, and reliability of physical entities or systems by enabling real-time data analysis and feedback[

17]. For example, DTs can be used in conjunction with augmented reality and virtual reality technologies to provide immersive and interactive experiences in virtual environments which allow for rich visualization of the physical entity [

18]. Also, Machine Learning (ML) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) can be used to predict potential problems before they occur and to support decision making through insights based on behavioral analysis and simulations[

19]. Additionally, DT is platform for connecting physical infrastructure by providing a platform with common services for collaboration, data sharing, and visualization [

19].

The future significance of DT is evident due to its application in everyday life. It continues to grow rapidly because of the breakthroughs in its enabling technologies, including but not limited to, IoT, AI, and Big Data. For example, recent advances in wireless communication technology such as WiFi 6/7 and 5G/6G has richer experiences for DT because of the increased bandwidth and reliability [

20]. Current projections for DT market estimate that its market is expected to reach

$48.2 billion by 2026 and

$1.3 trillion by 2030.

The rapid increase in the adoption of DT technology across all fields will inevitably lead to ecosystems of DTs forming, where heterogeneous DTs created and maintained by many stakeholders will need to cooperate and share data to realize stakeholder goals [

21,

22]. This requires trust relationships to be established between the stakeholders and DTs and between the different DTs [

23]. Despite its importance [

24,

25], it remains an under-investigated problem without any concrete trust models for DTs. Recent reviews [

8,

16,

26,

27] show that from a technical perspective most of the work is focused on security, safety and privacy, which is not enough for trust assurance [

28]. From a non technical perspective (i.e. stakeholder trust), Trauer et al [

29] presented a trust framework based on a literature review and an interview study with 7 recommendations to improve stakeholder trust in DTs. Furthermore, the trust problem is encompassing [

30], and DTs are inherently complex [

19], which requires modeling from different perspectives [

25]. Therefore, we attempt to characterize the potential trust issues of DTs from 3 different perspectives, trust issues in single DT, trust issues for cooperating DTs, and trust issues for stakeholders and their DTs. In sharp contrast to the survey articles found in the literature, our main contributions in this article can be summarized as follows:

Proposal of a 5 layer reference architecture for DTs.

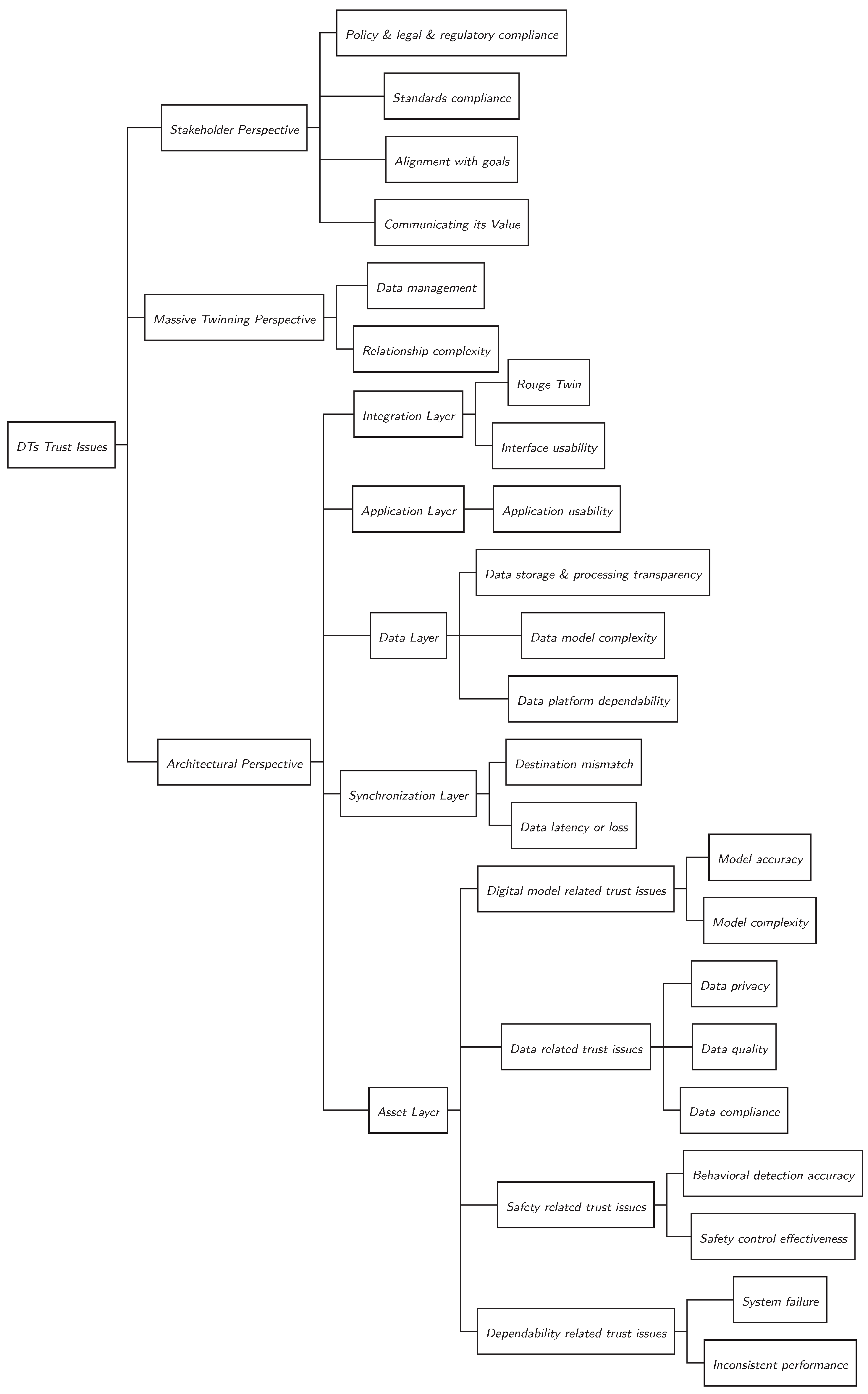

Taxonomy and categorization DT trust issues from 3 perspectives: architectural, massive twinning and stakeholders.

A parametric analysis of trust issues and their mapping to possible solutions for DT.

Future directions highlighting possible solutions for open DT trust problems.

Based on that, the rest of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents background about trust.

Section 3 presents our proposed reference architecture and an illustrative of how its is used to build architect a DT for a logistics hub.

Section 5 discuss the trust issues and recommendations for improving the trustworthiness form an architectural perspective based on our proposed reference architecture. Then,

Section 6 discusses the concept of massive twinning and its trust issues and recommendations. After that,

Section 7 discusses stakeholder trust in DT system and how it can be improved.

Section 8 presents a discussion of our architecture and findings while

Section 9 discusses related work. Finally,

Section 10 concludes and envisions future directions.

2. Trust Background

Trust is the belief or confidence that one has in another person, organization, or system to act in a reliable, honest, and competent manner[

31]. Trust involves taking a leap of faith based on past experiences, reputation, or other factors, with the expectation that the person, organization, or system will act in a predictable and consistent manner. In the context of cooperating systems, it is the degree of confidence or belief that the systems will collaborate for a common purpose in a reliable, honest, and competent manner, according to their intended functions and ethical principles, and in coordination with humans and other systems [

32].

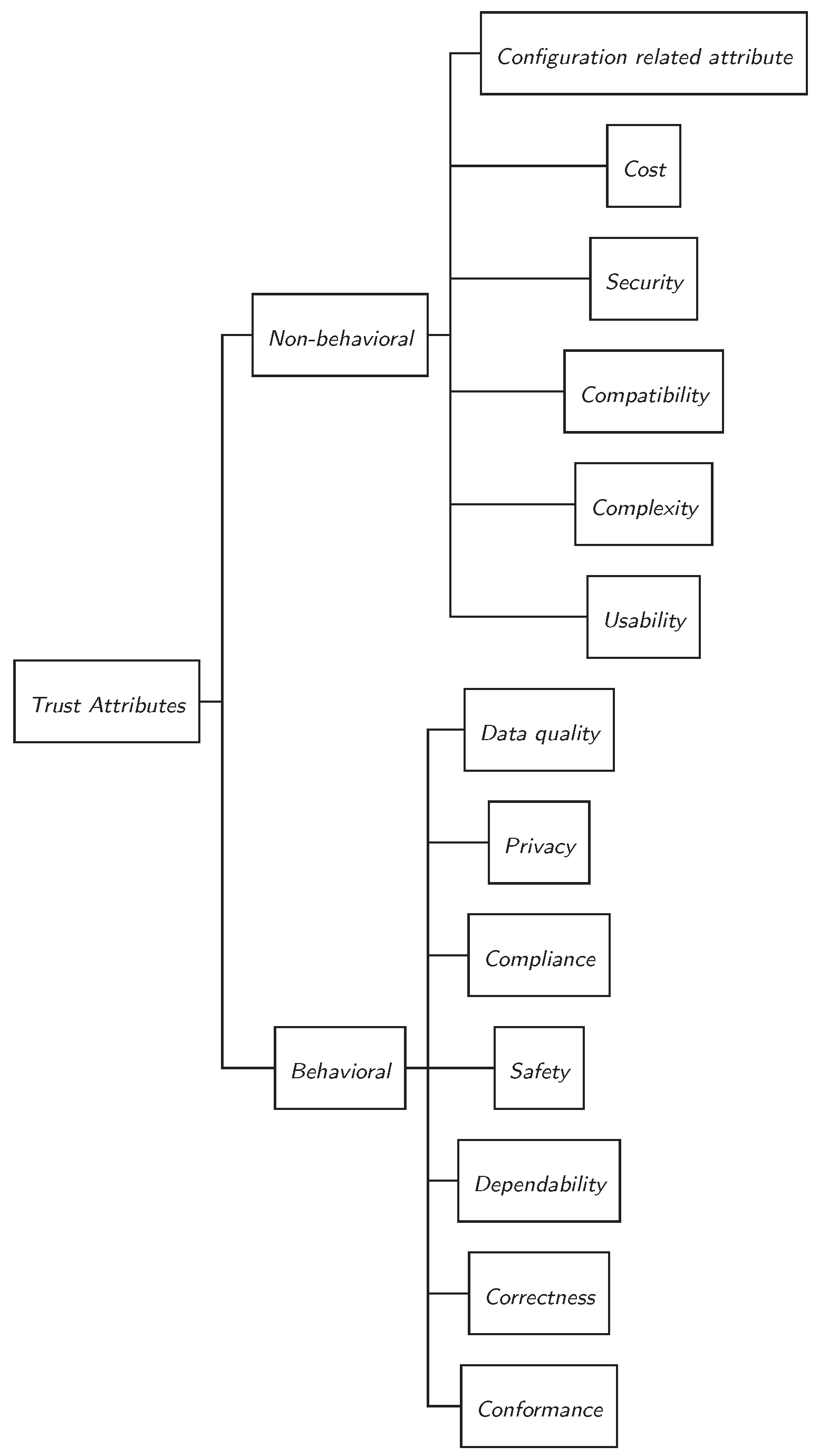

Trustworthiness, on the other hand, refers to the degree to which a system is perceived to be trustworthy. It is a measure of the reliability, honesty, and competence of the system, and is based on past experiences and reputation. It is a key factor in establishing and maintaining trust and it has several attributes. According to [

33] and [

28], trustworthiness has 14 attributes which we classify as either behavioral or non behavioral. These attributes are summarized in

Figure 1.

2.1. Trust Attributes: Behavioral

Attributes in this category are measured based on the behavior of the system. The attributes in this category are: Correctness, Safety, Performance, Compliance, Dependability, Privacy and Data quality. Correctness refers to the conformance of the behavior of the system to its formal specification[

34]. It can be verified and validated using several techniques such as testing and formal methods[

35]. Safety is an attribute the describes how well the system prevents harm to its users, assets and environment in case of hazards and threats [

33]. Performance is an attribute that measures how well the system provides its functionality and achieves its goals [

28,

33]. Several metrics could be used to measure the performance of a system such as throughput and latency[

36]. Compliance covers a wide range of areas [

33] and it is an attribute that describes the degree to which the system adheres to laws, regulations, and industry standards. For example, a system that stores data in non-standard formats or uses non-standard processing methods is less trustworthy. Dependability is complex attribute that describes several behavioral aspects of a system. A dependable system executes predictably and functions as intended. It encompasses several quality attributes of a system including: accuracy, availability, fault tolerance, flexibility, reliability, and scalability. [

28,

33]. It can be measured based on runtime metrics such as failure rate and mean time to failure [

37]. Privacy refers to protection of sensitive information by allowing stakeholders/users to control how data is collected, used and stored [

33]. Data quality attribute measures the quality of the data in terms of its validity, timeliness and integrity [

33].

These attributes apply to most computer systems but they become more important in the context of DTs because of the critical nature of the systems they are made for. For example, the trustworthiness of DTs of human beings must be continually assessed based on these attributes [

38]. On the other hand, conformance is a DT-specific trustworthiness attribute that measures how well a DT reflects its physical twin in terms of behavior [

28].

2.2. Trust Attributes: Non-Behavioral

Attributes in this category are not measured based on the behavior of the system, rather they are quantitatively or qualitatively measured based on aspects such as design or operation. Attributes in this category are: Usability, Complexity, Compatibility, Security, Cost, and Configuration-related attributes. Usability is a subjective attribute that measures the ease with which a system could be operated[

33]. Complexity is an attributes the measures the intricacy, inter-connectivity and heterogeneity of the system’s components and its data[

28,

33]. Compatibility is an attribute that measures the ease with which the system can integrate with other systems [

33]. Security refers to the ability of the system to protect itself and its data from attacks and misuse [

33,

39]. It can be measured by looking at qualitative aspects of the system including: Accountability, Traceability, Confidentiality, Integrity and Non-Repudiation. Cost is an attribute that quantifies trustworthiness of the system based on the investment to make it trustworthy [

33]. For example, investing in the certifying processes can be utilized to build and make the system more trustworthy [

28]. Configuration related attribute measure the degree of completeness and customizability of a system. In general, the more complete and customizable a system is, the more trustworthy it becomes [

33].

Most of the attributes in this category measure fundamental aspects of the system that are pre-requisites for a trustworthy system [

28]. For example, an unsecure system is untrustworthy regardless of the other attributes, because security is a pre-requisite for trustworthiness [

40].

3. Digital Twins Architecture

3.1. Overview

DTs are complex systems that require a deep understanding of both the physical asset or system being replicated and the technology used to create the virtual replica. A DT is a virtual representation of a physical asset or system that is used to simulate and predict its behavior in real-time. This requires a significant amount of data to be gathered from the physical asset or system, which is then used to create a digital model. The data can come from various sources, such as sensors, cameras, and other monitoring devices [

41]. The complexity of DTs is further compounded by the need for advanced analytics, modeling, and simulation capabilities. The data gathered from the physical asset or system needs to be analyzed and processed to create an accurate digital model that can be used for simulations and predictions. This requires expertise in data analytics, artificial intelligence, and ML [

42]. Furthermore, DTs can generate a tremendous amount of data, which can be overwhelming to manage and analyze. The data needs to be stored, processed, and analyzed in real-time, which requires robust data management and analysis capabilities. The management of DTs also requires continuous updates and maintenance to ensure their accuracy and relevance [

43]. Reference architectures are essential for DTs, as they provide a standardized framework for designing and implementing these technologies. A reference architecture is a standardized blueprint that outlines the key components, functionalities, and interactions required for a particular technology or system. In the case of DTs, a reference architecture provides a standardized approach for building and managing virtual replicas of physical assets or systems. In this work, we propose a reference architecture and use it to highlight a the DTs trust issues in terms of the components of the architecture. This section discusses the details of our proposed architecture and presents an application for constructing DT of logistics hub.

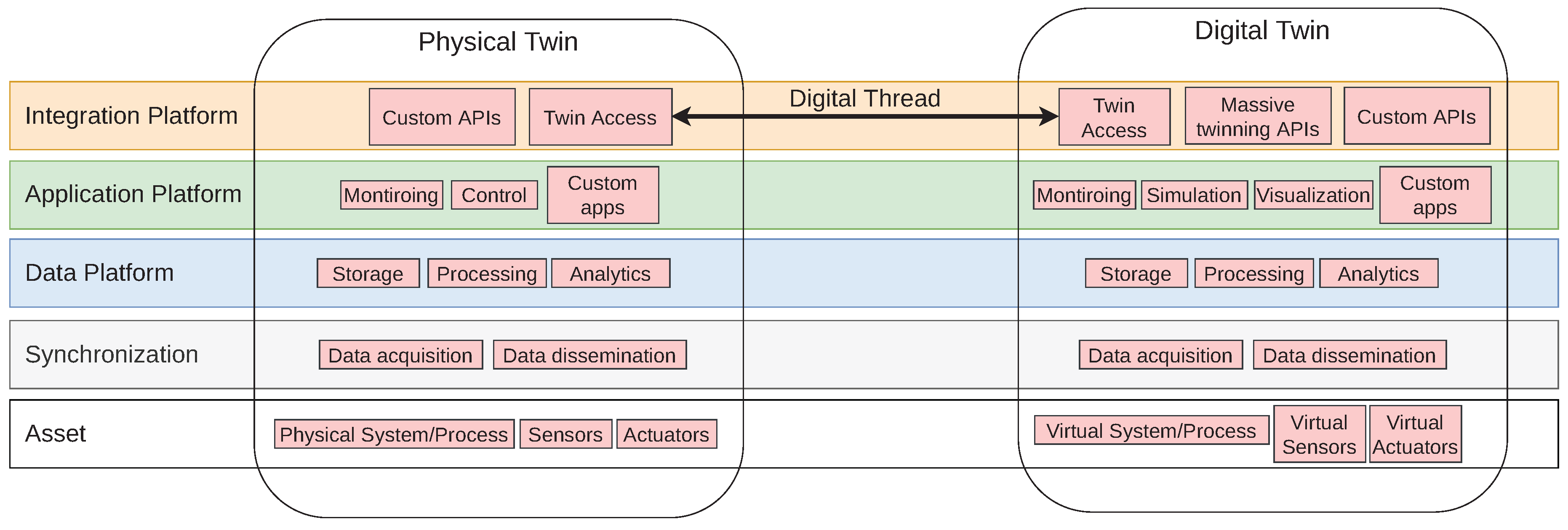

The proposed architecture is shown in

Figure 2, which depicts the twins as almost identical in terms of components and functionality. It is a layered architecture where each layer is present in both twins with some differences in terms of the included functionality in some layers between them. It has 5 layers: asset layer, synchronization layer, data layer, application layer and integration layer. The rest of this section is dedicated to describing the functionality of each layer the physical twin and its digital counterpart.

3.2. Asset Layer

The asset layer includes the physical system/process on the physical twin and its digital replica on the DT. On the physical side, it can include a wide range of entities, such as machines, equipment, sensors, and devices, as well as the environment in which they operate. These entities generate data that is collected and used to create and enhance a digital replica on the DT. The digital replica is modeled can be modeled using different techniques depending on the complexity, available data, and analysis purpose[

44].

The most common modeling techniques [

44,

45] include first principles models, data-driven models, and hybrid models. First principles models are based on physical laws and equations that govern the behavior of the physical system, making them reliable but computationally demanding. Data-driven models use ML and statistical methods to learn from the data collected from the physical system, making them flexible but requiring a lot of data and validation. Hybrid models combine both first principles and data-driven approaches to leverage the strengths and overcome the limitations of each method, achieving high accuracy and efficiency but requiring a lot of coordination between different modeling techniques.

3.3. Synchronization Layer

The synchronization layer serves as a middleware that abstracts the complexity of data delivery from the asset and data layers, within the physical and DTs. It provides a platform for managing the communication and integration of the asset layer and the data layer, with the following key functionalities:

Data collection: Collects data from the assets and devices in the system. This includes data from sensors, cameras, and other monitoring devices.

Data filtering and processing: Provides filtering and processing facilities for the data between the two layers. This can help to reduce the volume of data that needs to be processed at the destination, improving the performance and scalability of the system.

Data transmission: Reliably transmits the data from the asset layer to the data layer and vice versa.

Interoperability and integration: Provides a common platform for integrating and enabling communication between different heterogeneous devices and systems. This reduces the complexity and cost of integration and improves the interoperability of the system.

Security: Provides security features such as authentication, access control, encryption, and traceability and accountability to protect the data flow in both directions.

Fault tolerance and resilience: Implements Logic to detect and recover from communication failures or other faults that may occur during data transmission. This can help to ensure the robustness and reliability of the DT system, even in the presence of unexpected events or failures.

3.4. Data Layer

The data layer implements data related functionality, which includes processing, storage and analytics. Both twins implement these functionalities, but the data layer is richer and more complex on the DT side. This is because the DT stores its own data and that of its physical counterpart, and it is intended to provide more services (e.g. simulation) which require more complex systems. More specifically, it provides the following functions:

Data storage: Provides a storage mechanism for all collected and computed data, which can be in different formats such as structured, semi-structured, and unstructured data. It can also use different database technologies such as relational databases, NoSQL databases, and time-series databases, depending on the type of data and the requirements of the DT application.

Data processing and analytics: Provides facilities for processing and analyzing stored data generate insights and predictions about the underlying assets. This involves using various techniques such as statistical analysis, ML, and artificial intelligence algorithms to identify patterns and relationships in the data.

Data access: Provides a platform for accessing and querying the stored data, which includes providing APIs and other interfaces for accessing the data, as well as providing tools for data visualization and analysis.

Data security: Ensures the security and privacy of the stored data. This includes implementing access control mechanisms, data encryption, and other security features to prevent unauthorized access and data breaches [

46]. This also includes data governance policies, data retention policies, and data anonymization policies, which ensure that the data is used appropriately.

Data backup and recovery: Ensures that the data stored is protected from data loss or corruption. This involves implementing data replication, mirroring, and backup processes to create redundant copies. Also, it involves testing and validating the backup and recovery processes to ensure their reliability and effectiveness in the event of a data loss or corruption.

Model validation and verification (V&V) and accreditation: Involves checking that a DT model accurately represents the physical system under specified conditions, while Model Accreditation involves certifying that a DT model is suitable for a specific purpose or application. There are several methods and challenges for conducting V&V and accreditation of DTs, including continuous V&V, hybrid V&V, and hybrid framework. Continuous V&V involves performing it throughout the lifecycle of a DT, while the hybrid framework combines different V&V techniques for evaluating different aspects of a DT model. The hybrid framework establishes a systematic approach for conducting V&V and Accreditation of DTs. It is based on clear definitions, criteria, metrics, and documentation to facilitate communication and collaboration among different stakeholders.

3.5. Application Layer

The application layer implements a platform where applications could be developed to allow users and stakeholders to interact with the underlying assets using graphical user interfaces. However, it provides the following core functionality:

Monitoring and control: Allows users to monitors the underlying control assets in realtime.

Simulation and modeling: Allows users to simulate the behavior of the physical twin under different conditions, which can be performed based on real-time data or historical data, depending on the requirements of the DT application.

Analysis and optimization: Allows users to analyze the data and optimize the performance of the physical system, which can be performed using various techniques such as statistical analysis, ML, and AI algorithms.

Reporting and visualization: Allows users to generate reports and visualize the data in various formats such as charts, graphs, and tables, which can be customized based on the user’s requirements and preferences.

Some applications are implemented on both twins (e.g. control and monitoring), while others are usually only implemented on the DT (e.g. visualization).

3.6. Integration Layer

The integration layer is a platform that allows stakeholders to define services and interfaces, which allow their twins to communicate with external systems. It provides the core functionality of synchronizing the physical twin to its digital counterpart through the twin access component, which handles data ingestion, protocol translation, and real-time state updates. Another component that could be included in this layer is a massive twinning component that allows DTs of different systems to cooperate, creating a network of interoperable digital models.

This interoperability is the key to unlocking system-of-systems intelligence. By enabling DTs to leverage existing cloud-based systems and services, the integration layer facilitates the creation of richer, composite services. For instance, a DT from a logistics network can share data with a DT from a manufacturing plant, allowing for dynamic, just-in-time part delivery and production rescheduling.

Ultimately, this layer acts as the central nervous system for the entire DT ecosystem. It not only ensures seamless data flow but also manages security, access control, and governance across all connected twins and external services, transforming isolated digital models into a cohesive, intelligent, and actionable enterprise asset.

4. Illustrative and Comparative Study

4.1. Illustrative Example

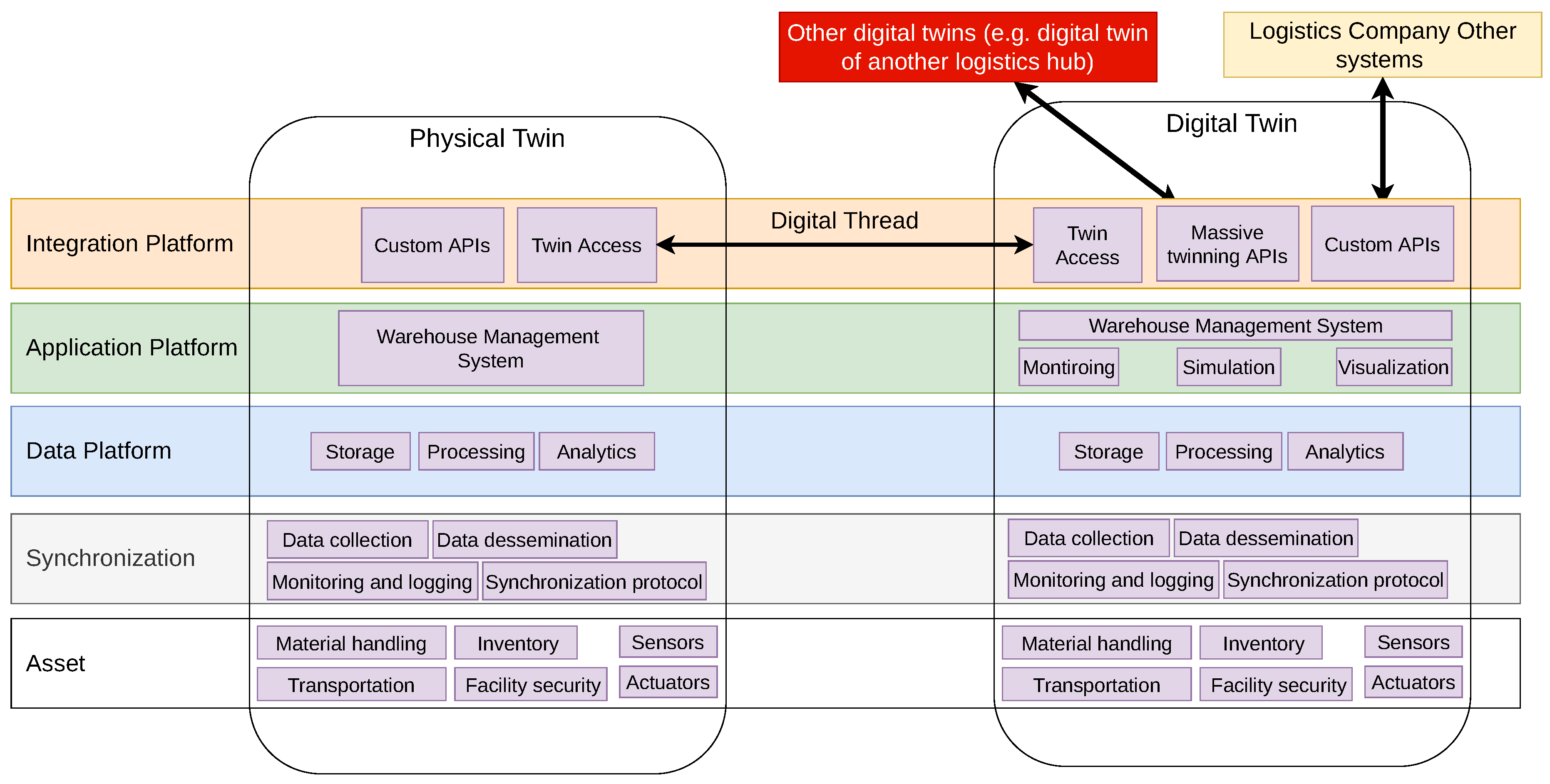

This example describes the construction of a DT of a logistics hub using our proposed architecture. A logistics hub is a central location where goods are received, sorted, stored, and distributed to their final destinations. The environment of a logistics hub is typically a large warehouse or distribution center, where a variety of technologies are used to manage the movement of goods.

A logistics hub is a complex facility that comprises several components, including receiving and shipping areas, storage areas, material handling systems, inventory management systems, transportation management systems, office and administrative areas, and security and safety systems. These components work together to ensure that goods are moved and stored efficiently and effectively. Material handling systems, such as conveyor belts and robotic arms, help to move goods around the facility, while inventory management and transportation management systems track the movement of goods from the warehouse to their final destination. Office and administrative areas allow staff to manage the movement of goods and coordinate with carriers, while security and safety systems ensure the safety of staff and goods.

Figure 3 shows where each of the components fit according to our architecture. For the physical twin, the asset layer contains the material handling, transportation and inventory management systems, in addition to all other sensors and actuators (e.g. cameras, control terminals etc..). At the synchronization layer, dedicated IoT infrastructure that synchronizes the asset and data layers is introduced, such as message brokers, which completely decouples them. This greatly improves the maintainability at each of the layer, but more so for the asset layer, as broken assets are often replaced and new assets are introduced. The data layer stores, processes and analyzes all data within the physical twin. The application layer contains applications that staff use to manage the facility, such as the warehouse management system. At the integration, custom APIs are defined to integrate the physical twin with local services and its DT.

The DT has an identical structure and functionality to its physical counterpart. However, the DT has a more complex data, application and integration layers because it provides more complex services. For example, it might provide predictive analysis at the data layer, simulation at the application layer, and integrations with other DTs and other systems owned by the same company (e.g. ERP systems).

4.2. Comparison With Existing Architectures

Existing architectures such as the ones described in [

16] and [

47] often envision the physical twin to have a different architecture from its DT. For example, the architecture [

16] presents the physical twin as a layer in the architecture of the DT, where a digital thread is introduced to connect it to the first layer in the DT. This greatly simplifies the development of the DT, because all the integration with the physical twin is taken care of by the digital thread. However, it introduces several problems with it, as follows:

The DT is fully dependent on the physical twin, because it is part of the architecture of the DT. This greatly impacts several quality attributes of the DT, such as testability, because the physical twin has to be present to test the DT. Also, flexibility and scalability are impacted, as it is unclear how to connect multiple DTs to the same physical counterpart.

The architecture of the physical twin and the DT could be different. This makes the DT difficult to maintain, as developers look at different specifications when working with the twins.

There is a clear distinction between the physical twin and the DT, because each DT depends on its physical twin. This simplifies finding the physical twin when its digital counterpart is compromised.

On the other hand, in our proposed architecture the DT is an extended digital replica of the physical twin and they both integrate through their integration layers. This solves the first problem because a given twin could be configured to connect to one or multiple twins by extending the twin access component. Furthermore, since both twins have the same architecture, perhaps with extended features on the digital side, maintaining both systems becomes simpler and cheaper because the components of the upper layers on physical side are reused on the digital side. Finally, in our architecture there is no clear distinction between the physical and DTs, because they are modeled like peers that can be connected at will.

5. Toward Trustworthy Digital Twins Architecture

5.1. Overview

Ensuring trust in DTs is critical for their effective use in decision-making and optimization. To integrate trust into our DT architecture, the potential trust issues need to be considered at each of the layers of our architecture. These trust issues affect the trust attributes that we discussed in

Section 2. In this work we focus on how the behavioral attributes are impacted by the trust issues at each layer.

Table 1 presents a summary of these attributes.

5.2. Asset Layer

The asset layer has a physical side and a digital side, that represent each of the twins, respectively. All the trust attributes are impacted at this layer because of its sheer complexity, where interactions between humans, machines and data are managed. The trust issues at this layer can be categorized into four categories, namely, safety related issues, data related issues, dependability related issues, and digital model issues.

5.2.1. Safety Related Trust Issues

Safety is the ability to operate without risk of injury or harm to the system’s environment and its users and it can be achieved by ensuring that there are no consequences on them [

33]. Safety is a critical aspect of trustworthiness and a major concern in critical systems, because those could cause harm to the environment if they did not have designed-in safety mechanisms that mitigate potential risks to a tolerable level [

48]. In addition to mitigating common issues and failures at design time [

49], this requires the behavior of the system to be monitored to detect potential issues at runtime and activate those safety mechanisms [

50]. This highlights two major safety-related trust issues, namely, safety control effectiveness and behavioral based detection accuracy.

5.2.2. Data Related Trust Issues

There are 3 data related trust issues, namely, data quality issues, data compliance issues, and data privacy issues. The quality of the data according to [

33] is measured in terms of its integrity, reliability, timeliness and validity. Data compliance issues are related to legal compliance legal requirements of waht data is collected and how it is collected, such as complying with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Privacy is defined as the protection of personal or sensitive information that is collected, processed, or transmitted by interconnected devices and systems[

51]. It is a major concern for DTs in certain contexts (e.g. smart cities) because these technologies enable continuous sensing and data sharing, which may expose users’ identities, locations, preferences, or behaviors to unauthorized parties [

51].

5.2.3. Dependability Related Trust Issues

There are two dependability-related trust issues, namely, inconsistent performance and system failures. These occur as a result of poor practices during the lifecycle of the DT [

52]. They are partially addressed partially during the development of the DT by improving its scalability, reliability and resilience [

52,

53,

54]. Reliability is the ability of interconnected devices, systems, and applications to perform consistently and accurately in their environments [

55]. Scalability means that a system can cope with the rising workload caused by the expansion of elements in the system during its functioning without compromising its efficiency [

54,

56]. Resilience is defined as the ability of a system to withstand cyber attacks, recover from failures, and maintain its functionality and security throughout its lifecycle [

53,

57]. Then, at run time, the behavior of the DT is monitored to detect potential scenarios that might lead to a failure or performance issues[

58]. For example, during the operation of the DT, monitoring is imperative to anticipate unforeseen load based on the behavior of the system. Otherwise, the system may have inconsistent performance or fail.

5.2.4. Model Related Trust Issues

Model complexity is the degree of difficulty in understanding, designing and managing a system that has many interrelated parts and behaviors [

59]. It is a key challenge for trustworthiness in DTs because it increases uncertainty, variability and unpredictability of the system [

60]. It might also require more data, computation and communication resources, which can introduce errors, biases and vulnerabilities [

59,

60]. Atkinson et al. [

59] analyzed the current DT standards and architectures, and identified some of the sources of unnecessary accidental complexity. The work proposed new standards and architectures that could support the efficient implementation of DTs and their seamless integration with other systems. The work also suggested some best practices and guidelines for reducing complexity and enhancing quality in DTs. Composability, is one way of managing complexity, and it is defined as the ability to combine digital elements into larger assemblies and models that can be reused and modified [

61]. It can help improve trustworthiness at this layer by enabling interoperability, modularity and flexibility. It can also facilitate verification and validation by allowing reuse of existing components and models that have been tested and verified. Composing DTs to build more complex DTs is referred to as massive twinning which introduces more trust issues [

62] that we discuss later.

Model accuracy is the degree to which the DT model reflects the reality and behavior of the physical system. It is a measure of how closely the model matches the actual system in terms of inputs, outputs and dynamics.Accuracy can be improved through the use of verification and validation procedures [

28,

63]. Verification is the process of checking whether the model is correctly implemented according to its specifications. Validation is the process of checking whether the model is consistent with the observed data and phenomena. Verification and validation can help ensure that the model is reliable, accurate and credible. Furthermore, according to [

28] the accuracy of the model changes over time because of the temporal aspect of the physical system, which naturally degrades over time. Tao et al. [

64] proposed a DT modeling theoretical system, which deconstructed and investigated the DT modeling from six aspects: model construction, model assembly, model fusion, model verification, model modification, and model management. Also, they presented a DT modeling framework based on the theoretical system, and applied it to a case study of an aircraft engine DT. This trust issue depends on the correctness and conformance attributes.

5.3. Synchronization Layer

This layer in a DT architecture abstracts the complexity of data delivery from the asset and data layers. It serves as a bridge between the asset and data layers in the physical twin and the DT, which abstracts the data delivery logic from both layers. There are two major trust issues at this layer, data latency/loss and destination mismatch[

65]. Data latency/loss occurs when data is delayed or not delivered to the destination, which can be due to network factors, such as network congestion or bandwidth limitations, or a fault in the synchronization system itself. This can lead to inconsistencies in the destination’s state, affecting its accuracy and reliability. On the other hand, destination mismatch occurs when data is delivered to the wrong destination, which can happen due to configuration errors, network issues, or compromise of the system itself. This can result in an inconsistent state at the intended and wrong destinations. These issues impact the correctness, dependability, and privacy trustworthiness attributes.

5.4. Data Layer

DTs are complex systems that generate and process large volumes of data, often in real-time, depending on the application and the complexity of the system. The purpose of this layer is to store and process all of this data. The physical and DTs also share the trust issues at this layer, although they become more pronounced in the latter because of its inherent complexity [

16]. There are three main trust issues at this layer, namely, poor data platform dependability, data model complexity and data storage and processing transparency.

Poor dependability of the data platform is a critical trust issue because the platform must be able store big data, as the DT becomes more complex. This requires the platform to dynamically adjust to meet the needs of the DT. The complexity of the data model is another trust issue, which could lead to dependability and maintainability issues of the model and its applications [

66]. This includes degrading performance, increasing the difficulty for developing and maintaining applications to leverage this data and increases the probability of bugs which degrades the quality of the data[

67]. This issue affects the dependability and data quality attributes.

Clarity and comprehensibility of how data is collected, stored, analyzed, and used is a critical a major trust issue at this layer. This is because the processing and storage of data affects the quality of the data which is a key trustworthiness attribute [

33]. For example, AI is used to analyze the data and provide insights, which heavily depends on the suitability of the model used [

61,

68,

69] and the repeatability and reliability of the results are contingent on the used AI techniques being explainable and verifiable[

61,

70]. These aspects become imperative in the context of critical systems [

71]. This issue affects the compliance and data quality attributes.

5.5. Application Layer

This layer is an application platform that allows users to interact with and visualize assets through different applications. For example, CAD/ECAD (electronic computer-aided design) systems can be used visualize and manipulate its geometric, physical and behavioral aspects [

72]. Furthermore, since these applications deal with complex and critical systems, it is important that they be easy to use. Therefore, a critical trust isuue at this layer is the usability of those applications and in that regard the literature on software usability can be leveraged to objectively benchmark their usability as an attribute for computing trustworthiness [

28,

33]. Furthermore, the usability of the applications affects several behavioral trust attributes, including dependability, compliance, privacy and data quality. Dependability is affected when the applications do not perform well (e.g. constantly crash). compliance is affected, if the applications collect data in such a way that they break the law, such as collecting data from minors in a smart city context. privacy is affected when the applications leak data to unauthorized entities. Finally, data quality is affected when, for example, an application displays data with lower precision (e.g., by rounding or truncating numbers). This might compel the user to make an incorrect decision based on that low-quality data.

5.6. Integration Layer

This layer is an interface/API platform where APIs are deployed to allow the physical and DTs to synchronize and integrate with other systems. One of the trust concerns at this layer is usability, which refers to how well it exposes the underlying functionality in terms of ease of use [

73], which can be addressed through different techniques such as usability testing and surveys. Another issue is the trustworthiness of the DT from the perspective of the physical twin, which is introduced at this layer because of the synchronization of the twins, and vice versa. Each twin continuously analyzes the behavior of the other in an attempt to detect malicious behavior [

25,

74]. This analysis considers many properties, such as accuracy, to determine the trustworthiness of each of the entities by the other [

28,

74]. Usability at this layer has the same implication in terms of impact on trust attributes.

6. Trust from a Massive Twinning Perspective

Massive twinning [

75] is the concept of creating and maintaining a digital twin for almost every physical entity (such as humans, machines, or processes) in a networked scenario, and using these digital twins to provide data, insights, and control for various applications. Massive twinning is envisaged to be a key feature of 6G networks, as it can enable pervasive intelligent services in industrial and other domains. Massive twinning can also enhance the performance of emergent intelligence (EI) applications, which rely on the interaction among massive agents with simple logic to achieve complex behavior patterns. By migrating the data and logic from the physical agents to their digital twins on the edge server, massive twinning can reduce the traffic load and improve the reliability of EI applications.

Trust management in massive twinning context refers to the ability of digital twins to establish and maintain trust relationships with other digital twins or human agents based on their behavior and reputation [

25]. It is a key element that enables better decision-making and improved operational efficiency of digital twins [

76]. It can also help enhance the resilience and adaptability of the cooperating digital twins by detecting and resolving any conflicts or anomalies that may occur [

25,

76]. The first trust issue is this context is relationship complexity, because in massive twinning the relationships between two DTs is not always symmetric. This asymmetry introduces a lot of complexity that renders most trust models that assume symmetric unusable (e.g. P2P trust models). Another trust issue is data management, because cooperating DTs share a lot of data that has to be stored in a tamper proof way.

7. Trust from a Stakeholder Perspective

Stakeholder trust in a DT is the confidence they have in its design and behavior, which includes its relationships to other systems and stakeholders[

29]. Furthermore, as adoption for DT technology increases, ecosystems will form where they cooperate and share data possibly across domains (i.e. different organizations) which might result in conflicts of interest among stakeholders [

29]. Hence, the need for mechanisms to assure stakeholders of the trustworthiness of their DT (i.e. its value and alignment with their goals). Recent literature indicates that two types of assurances that could be provided to stakeholders:

Qualitative trust assurance: Used to educate the stakeholder about the value of the DT and how it provides that value[

29,

77]. This is difficult to quantify [

77], but there are frameworks that have concrete recommendations of how to achieve that such as [

29]. Furthermore, educating the stakeholders about the behavior of the DT can be done through using modelling techniques (e.g. crystal-box and grey-box modelling) or examining the actual source code of the DT [

77], the main goal here is to provide transparency about the inner workings of the DT.

Quantitative trust assurance: Used to provide stakeholders with concrete estimations of the conformance of the DT to its physical counterpart in terms of model and behavior [

77,

78]. This involves performing automated model validation and verification based on uncertainty quantification [

77], for which open-source tools such as UQpy [

79] exist. For behavioral estimations, usually ML based approach (supervised, semi-supervised or unsupervised) are used to model the behavior of the PT and use that to estimate errors in the DT [

25].

Also, compliance with legal and regulatory requirements is another critical trust issue related using DTs[

80]. For example, DTs must comply with data protection laws such as the General Data Protection Regulation and the California Consumer Privacy Act when they rely on sensitive data, including personal data about individuals, which are designed to protect the privacy and security of personal data and give individuals control over how their data is collected, processed, and used.

8. Key Findings and Interpretations

In this paper, we have explored the trust issues of DTs from three different perspectives: architectural perspective, massive twinning perspective, and stakeholders perspective. We have not discussed any security issues in this paper, as security is a prerequisite for trust. Security refers to the protection of DTs from unauthorized access, modification, or damage, while trust refers to the confidence that DTs behave as expected and intended. Trust is built upon security, but also depends on other factors such as transparency, accountability, reliability, and fairness. Therefore, we focus on the trust challenges that go beyond security in the context of DTs. Also, security issues for DTs has been thoroughly explored in the literature [

16,

81].

Our proposed architecture facilitates the development of DTs because it uses functional layers that exist on both the physical and digital counterparts. In that way, the DT is presented as a digital version of the physical twin with extra functionality. For example, at the application layer, some of the same applications that exist on the physical twin could be deployed on the DT with DT specific ones. This is a departure from the existing architectures in the literature, which present the physical twin as the "physical layer" in the architecture of the DT such as [

15,

47,

82]. Furthermore, isolating the digital and physical assets into their own layer facilitates model validation and verification, as the process of synchronizing it to the data layer is delegated to a separate layer. Also, the synchronization between the twins happens through their respective integration layers which gives each of them full control the their level of integration with their counterpart. Overall, the architecture maximizes reuse and improves maintainability, as both sides (digital and physical) have identical structure.

From an architectural perspective, the trust issues at the asset layer revolve around the construction of the physical and digital assets, such as reliability and scalability. At the synchronization and integration layers layer, the trust issues are mainly communication trust issues, such as interoperability and performance. At the data layer, the complexity of the data models and transparency of AI/ML algorithms are the most pronounced trust issues. At the application layer, application usability is the most pronounced trust issue, as it directly impacts the decisions (or lack there of) taken by the stakeholders.

Trust issues in massive twinning are going to become more pronounced as DTs become more ubiquitous. These issues might seem similar to trust issues of peer to peer systems, however, in a massive twining context the relationships between different DTs are much more complex and often asymmetrical. For example, in massive twinning a single DT could be composed of several smaller DTs, which have relations ships with each other and the one that encompasses all of them. However, it is currently not feasible to develop trust management solutions in this context because its security and privacy is under-investigated and some of the enabling technologies are still not widely in use such as 5G/6G networks [

75].

From the perspective of stakeholders, trust issues revolve around understanding the value of the DT and its methods. For example, they need to understand the internal processes of the DT and how these processes add value to the them.

9. Related Work

Several reviews were published recently [

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89] that cover many aspects of DTs from concept to implementation. Furthermore, other recent reviews that focus mainly on enabling technologies and challenges in DTs were also published in [

3,

8,

26,

27,

43]. These reviews show that cybersecurity related research in DTs has been mainly focused security and privacy. Thus, the literature on building trustworthy DTs is scarce, however, the concept of trustworthiness has been explored in other contexts such as IoT [

31] and Cyber Physical Systems [

33] which could be leveraged in building for DTs. The rest of this section discusses recent developments in cybersecurity and trust for DTs.

Figure 4.

DT Trust Issues From Three Different Perspectives

Figure 4.

DT Trust Issues From Three Different Perspectives

9.1. Recent Advances in Security for DTs

Alcaraz et al. [

16] presented a comprehensive survey of security threats for DTs. They analyze the current state of the DT paradigm and its enabling technologies and identifies its operational requirements. Then it classifies the security threats based on these operational requirements. The reviews in [

90,

91] discuss blockchain-based DTs and the role blockchain technology plays in their security. Examples of blockchain use in DTs can be found in [

92,

93], where blockchain is used to manage DT data. Hasan et al [

90] proposed a blockchain-based approach for creating DTs, which can provide secure and trusted traceability, accessibility, and immutability of data and transactions involved in the creation process of DTs. It uses InterPlanetary File System to host all the data resulting from all interactions.

9.2. Recent Advances in Trust for DTs

Rivera et al. [

76] proposed a maturity model for the development and sophistication for DTs, from blueprint to cooperating DTs. Also, it proposes a framework that identifies five technical enablers for achieving autonomic and cooperative DTs, where they highlight the importance of trust and how it can be integrated into their framework. The authors in [

94] proposed a trust and security analyzer for cooperating DTs based on 6 criteria security, resilience, reliability, uncertainty, dependability, and goal analysis. Bonney et al [

77] proposed the use of crystal-box workflow improve trust and transparency in a DT. The proposed workflow contextualizes the information of the DT to the user by allowing them inspect how it acquires, processes the data is acquired, processed, and used by the DT, without being able to modify them. The workflow was demonstrated using an open source digital platform using a case study of a scaled 3 storey structure, which showed data is generated and processed and how DT information is contextualized for the user. Trauer et al. [

29] proposed a framework to help practitioners create trust in DTs which consists of three main components: stakeholders, user stories, and solution elements. Solution elements are the recommendations and measures to increase trust in DTs, such as explaining the twin properly, creating a common incentive, ensuring IP protection and IT security, proving the quality, ensuring a uniform environment, and documenting thoroughly. The framework is based on a literature review, a market study, and an interview study with 10 experts from various industries. It was evaluated by 12 experts, where they found it to be generally useful and applicable.

10. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper has presented a comprehensive exploration of behavioral trust in DTs, addressing a critical and under-investigated area as DT ecosystems become more complex and interconnected. Our work provides a structured foundation for understanding, analyzing, and enhancing the trustworthiness of DTs through three primary contributions.

First, we proposed a novel 5-layer reference architecture for DTs, comprising Asset, Synchronization, Data, Application, and Integration layers. A key differentiator of this architecture is its symmetrical design, where both the physical and DTs are modeled as peers with identical layered structures. This approach facilitates greater reusability, maintainability, and a clearer conceptual model compared to existing architectures that often subsume the physical twin within the DT’s structure. The illustrative example of a logistics hub demonstrated the practical applicability of this architecture. Second, we developed a systematic taxonomy and analysis of DT trust issues from three distinct yet interconnected perspectives. The Architectural Perspective meticulously identifies and categorizes potential trust issues at each layer of our proposed architecture, mapping them to key behavioral trust attributes such as conformance, correctness, dependability, safety, compliance, privacy, and data quality. This layer-by-layer analysis provides a granular blueprint for developers to pinpoint and address trust vulnerabilities during the design and operation of a DT. The Massive Twinning Perspective examines the emergent trust challenges in scenarios where numerous DTs cooperate. This context introduces unique complexities, such as asymmetric relationships and sophisticated data management requirements, which render traditional symmetric trust models inadequate and call for new, dynamic trust management solutions. The Stakeholder Perspective highlights the importance of stakeholder confidence, distinguishing between qualitative assurances (e.g., transparency and value communication) and quantitative assurances (e.g., model conformance metrics and behavioral error estimation). This underscores that technical trustworthiness must be complemented by perceived trust to ensure widespread adoption.

Finally, our parametric analysis and discussion synthesized these perspectives, clarifying that security, while a fundamental prerequisite, is not sufficient for trust. True trustworthiness in DTs is built upon a combination of robust architecture, reliable data, transparent processes, and usable interfaces, all of which must function cohesively across potentially massive and collaborative ecosystems.

Looking ahead, several promising directions emerge. The proposed trust taxonomy and architectural analysis require validation through empirical studies and real-world case studies across different domains like manufacturing, healthcare, and smart cities. There is a pressing need to develop concrete trust models and metrics tailored for the asymmetrical and composable nature of massive twinning environments. Furthermore, integrating blockchain for tamper-proof data management and advancing explainable AI for transparency in the Data and Application layers are critical technological enablers. Standardizing methods for continuous Verification, Validation, and Accreditation will also be essential for maintaining trust over the entire DT lifecycle. By addressing these open challenges, the research community can pave the way for the development of truly trustworthy DTs that are reliable, transparent, and fit for purpose in our increasingly digital world.

References

- Alhazmi, T.; Azzedin, F.; Hammoudeh, M. MQTT Based Data Distribution Framework for Digital Twin Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Future Networks & Distributed Systems, 2024, pp. 1008–1013.

- Tao, F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, A.; Nee, A.Y. Digital twin in industry: State-of-the-art. IEEE Transactions on industrial informatics 2018, 15, 2405–2415. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Bilal, M.; Qiu, Y.; Qian, C.; Xu, X.; Raymond Choo, K.K. Survey on digital twins for Internet of Vehicles: Fundamentals, challenges, and opportunities. Digital Communications and Networks 2022. [CrossRef]

- Purcell, W.; Neubauer, T. Digital Twins in Agriculture: A State-of-the-art review. Smart Agricultural Technology 2022, p. 100094.

- Piromalis, D.; Kantaros, A. Digital Twins in the Automotive Industry: The Road toward Physical-Digital Convergence. Applied System Innovation 2022, 5, 65. [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Wang, D.; Shen, W.; Li, X.; Liu, Q.; Chen, X. Digital twins-based smart manufacturing system design in Industry 4.0: A review. Journal of manufacturing systems 2021, 60, 119–137. [CrossRef]

- Menassa, C.C. From BIM to digital twins: A systematic review of the evolution of intelligent building representations in the AEC-FM industry. Journal of Information Technology in Construction (ITcon) 2021, 26, 58–83.

- Alazab, M.; Khan, L.U.; Koppu, S.; Ramu, S.P.; Iyapparaja, M.; Boobalan, P.; Baker, T.; Maddikunta, P.K.R.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Aljuhani, A. Digital Twins for Healthcare 4.0-Recent Advances, Architecture, and Open Challenges. IEEE Consumer Electronics Magazine 2022.

- Schleich, B.; Anwer, N.; Mathieu, L.; Wartzack, S. Shaping the digital twin for design and production engineering. CIRP annals 2017, 66, 141–144. [CrossRef]

- Wagg, D.; Worden, K.; Barthorpe, R.; Gardner, P. Digital twins: state-of-the-art and future directions for modeling and simulation in engineering dynamics applications. ASCE-ASME J Risk and Uncert in Engrg Sys Part B Mech Engrg 2020, 6. [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M.; Vickers, J. Digital twin: Mitigating unpredictable, undesirable emergent behavior in complex systems. In Transdisciplinary perspectives on complex systems; Springer, 2017; pp. 85–113.

- Sepasgozar, S.M. Differentiating digital twin from digital shadow: Elucidating a paradigm shift to expedite a smart, sustainable built environment. Buildings 2021, 11, 151. [CrossRef]

- Alhazmi, T.; Azzedin, F.; Hassine, J.; Hammoudeh, M. Formal Specification and Executable Analysis of Digital Twin Systems Using Maude Rewriting Logic. Future Generation Computer Systems 2025, p. 108148.

- VanDerHorn, E.; Mahadevan, S. Digital Twin: Generalization, characterization and implementation. Decision Support Systems 2021, 145, 113524. [CrossRef]

- Alam, K.M.; El Saddik, A. C2PS: A digital twin architecture reference model for the cloud-based cyber-physical systems. IEEE access 2017, 5, 2050–2062. [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz, C.; Lopez, J. Digital Twin: A Comprehensive Survey of Security Threats. IEEE Communications Surveys Tutorials 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kukushkin, K.; Ryabov, Y.; Borovkov, A. Digital Twins: A Systematic Literature Review Based on Data Analysis and Topic Modeling. Data 2022, 7, 173. [CrossRef]

- Opoku, D.G.J.; Perera, S.; Osei-Kyei, R.; Rashidi, M. Digital twin application in the construction industry: A literature review. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 40, 102726. [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.; Snider, C.; Nassehi, A.; Yon, J.; Hicks, B. Characterising the Digital Twin: A systematic literature review. CIRP Journal of Manufacturing Science and Technology 2020, 29, 36–52. [CrossRef]

- Iraji, S.; Mogensen, P.; Ratasuk, R. Recent advances in M2M communications and Internet of Things (IoT). International Journal of Wireless Information Networks 2017, 24, 240–242. [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.; Fischer, J.; Boschert, S. Next generation digital twin: An ecosystem for mechatronic systems? IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 265–270. [CrossRef]

- Eckert, C.; Isaksson, O.; Hallstedt, S.; Malmqvist, J.; Rönnbäck, A.Ö.; Panarotto, M. Industry trends to 2040. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Design Society: International Conference on Engineering Design. Cambridge University Press, 2019, Vol. 1, pp. 2121–2128.

- Rasheed, A.; San, O.; Kvamsdal, T. Digital twin: Values, challenges and enablers from a modeling perspective. Ieee Access 2020, 8, 21980–22012. [CrossRef]

- Trauer, J.; Mutschler, M.; Mörtl, M.; Zimmermann, M. Challenges in Implementing Digital Twins–a Survey. In Proceedings of the International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2022, Vol. 86212, p. V002T02A055.

- Bersani, M.M.; Braghin, C.; Cortellessa, V.; Gargantini, A.; Grassi, V.; Presti, F.L.; Mirandola, R.; Pierantonio, A.; Riccobene, E.; Scandurra, P. Towards Trust-preserving Continuous Co-evolution of Digital Twins. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 19th International Conference on Software Architecture Companion (ICSA-C). IEEE, 2022, pp. 96–99.

- Sharma, A.; Kosasih, E.; Zhang, J.; Brintrup, A.; Calinescu, A. Digital twins: State of the art theory and practice, challenges, and open research questions. Journal of Industrial Information Integration 2022, p. 100383.

- Botín-Sanabria, D.M.; Mihaita, A.S.; Peimbert-García, R.E.; Ramírez-Moreno, M.A.; Ramírez-Mendoza, R.A.; Lozoya-Santos, J.d.J. Digital twin technology challenges and applications: A comprehensive review. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 1335. [CrossRef]

- Laplante, P. Trusting Digital Twins. Computer 2022, 55, 73–77. [CrossRef]

- Trauer, J.; Schweigert-Recksiek, S.; Schenk, T.; Baudisch, T.; Mörtl, M.; Zimmermann, M. A Digital Twin Trust Framework for Industrial Application. Proceedings of the Design Society 2022, 2, 293–302. [CrossRef]

- Stjepandić, J.; Sommer, M.; Stobrawa, S. Digital twin: conclusion and future perspectives. DigiTwin: An Approach for Production Process Optimization in a Built Environment 2022, pp. 235–259.

- Wei, L.; Yang, Y.; Wu, J.; Long, C.; Li, B. Trust management for Internet of Things: A comprehensive study. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 7664–7679. [CrossRef]

- Rein, A.; Rieke, R.; Jäger, M.; Kuntze, N.; Coppolino, L. Trust establishment in cooperating cyber-physical systems. In Proceedings of the Security of Industrial Control Systems and Cyber Physical Systems: First Workshop, CyberICS 2015 and First Workshop, WOS-CPS 2015 Vienna, Austria, September 21–22, 2015 Revised Selected Papers 1. Springer, 2016, pp. 31–47.

- Mohammadi, G. Trustworthy cyber-physical systems; Springer, 2019.

- Mohammadi, V.; Rahmani, A.M.; Darwesh, A.M.; Sahafi, A. Trust-based recommendation systems in Internet of Things: a systematic literature review. Human-centric Computing and Information Sciences 2019, 9, 1–61. [CrossRef]

- Ly, K.; Sun, W.; Jin, Y. Emerging challenges in cyber-physical systems: A balance of performance, correctness, and security. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS). IEEE, 2016, pp. 498–502.

- Samir, K.; Khabbazi, M.; Maffei, A.; Onori, M.A. Key Performance Indicators in Cyber-Physical Production Systems. Procedia CIRP 2018, 72, 498–502. 51st CIRP Conference on Manufacturing Systems, . [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.Z.A.; Kuo, S.y.; Lyons, D.; Shao, Z. Dependability in cyber-physical systems and applications, 2018.

- Miller, M.E.; Spatz, E. A unified view of a human digital twin. Human-Intelligent Systems Integration 2022, 4, 23–33. [CrossRef]

- Azzedin, F.; Suwad, H.; Rahman, M.M. An Asset-Based Approach to Mitigate Zero-Day Ransomware Attacks. Computers, Materials & Continua 2022, 73.

- Alyami, S.; Alharbi, R.; Azzedin, F. Fragmentation attacks and countermeasures on 6LoWPAN Internet of Things networks: Survey and simulation. Sensors 2022, 22, 9825. [CrossRef]

- of Standards, N.I.; Technology. Considerations for Digital Twin Technology and Emerging Standards 2021.

- Gartner. Reference Architecture for Digital Twin Technology 2021.

- Fuller, A.; Fan, Z.; Day, C.; Barlow, C. Digital twin: Enabling technologies, challenges and open research. IEEE access 2020, 8, 108952–108971. [CrossRef]

- Thelen, A.; Zhang, X.; Fink, O.; Lu, Y.; Ghosh, S.; Youn, B.D.; Todd, M.D.; Mahadevan, S.; Hu, C.; Hu, Z. A comprehensive review of digital twin—part 1: modeling and twinning enabling technologies. Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 2022, 65, 354. [CrossRef]

- Wunderlich, A.; Booth, K.; Santi, E. Hybrid analytical and data-driven modeling techniques for digital twin applications. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Electric Ship Technologies Symposium (ESTS). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–7.

- Azzedin, F. Mitigating denial of service attacks in RPL-based IoT environments: trust-based approach. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 129077–129089. [CrossRef]

- Aheleroff, S.; Xu, X.; Zhong, R.Y.; Lu, Y. Digital twin as a service (DTaaS) in industry 4.0: an architecture reference model. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2021, 47, 101225. [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Shi, X.; Song, S.; Wang, X. Study on IIoT-based Safety Platform of Industrial Enterprises. In Proceedings of the 2022 Prognostics and Health Management Conference (PHM-2022 London). IEEE, 2022, pp. 415–419.

- Premalatha, J.; Rajasekar, V. Industrial Internet of Things Safety and Security. In Internet of Things; CRC Press, 2020; pp. 135–152.

- Khan, W.Z.; Rehman, M.; Zangoti, H.M.; Afzal, M.K.; Armi, N.; Salah, K. Industrial internet of things: Recent advances, enabling technologies and open challenges. Computers Electrical Engineering 2020, 81, 106522. [CrossRef]

- Bertino, E.; Sandhu, R.; Thuraisingham, B.; Ray, I.; Li, W.; Gupta, M.; Mittal, S. Security and Privacy for Emerging IoT and CPS Domains. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Twelfth ACM Conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy, 2022, pp. 336–337.

- Moore, S.J.; Nugent, C.D.; Zhang, S.; Cleland, I. IoT reliability: a review leading to 5 key research directions. CCF Transactions on Pervasive Computing and Interaction 2020, 2, 147–163. [CrossRef]

- Gajek, S.; Lees, M.; Jansen, C. IIoT and cyber-resilience: Could blockchain have thwarted the Stuxnet attack? AI society 2021, 36, 725–735. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Christie, R.; Manjula, R. Scalability in internet of things: features, techniques and research challenges. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Res 2017, 13, 1617–1627.

- Xing, L. Reliability in Internet of Things: Current status and future perspectives. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2020, 7, 6704–6721. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Z.; Arafat, H. Internet of Things (IoT): Definitions. Challenges, and Recent Research Directions 2015.

- Al-Hejri, I.; Azzedin, F.; Almuhammadi, S.; Syed, N.F. Enabling Efficient Data Transmission in Wireless Sensor Networks-Based IoT Applications. Computers, Materials & Continua 2024, 79.

- Attaran, M.; Celik, B.G. Digital Twin: Benefits, use cases, challenges, and opportunities. Decision Analytics Journal 2023, 6, 100165. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, C.; Kühne, T. Taming the complexity of digital twins. IEEE Software 2021, 39, 27–32. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zheng, X.; Schweiger, L.; Kiritsis, D. A cognitive approach to manage the complexity of digital twin systems. In Smart Services Summit: Digital as an Enabler for Smart Service Business Development; Springer, 2021; pp. 105–115.

- Wang, B.T.; Burdon, M. Automating trustworthiness in digital twins. In Automating Cities; Springer, 2021; pp. 345–365.

- Ghaleb, M.; Azzedin, F. Trust-aware Fog-based IoT environments: Artificial reasoning approach. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 3665. [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.; Davidson, S. How to tell the difference between a model and a digital twin. Advanced Modeling and Simulation in Engineering Sciences 2020, 7, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Xiao, B.; Qi, Q.; Cheng, J.; Ji, P. Digital twin modeling. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2022, 64, 372–389. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.A.; Memon, Z.A.; Durrani, N.M.; Haider, W.; Laeeq, K.; Mallah, G.A. A multi-layer trust-based middleware framework for handling interoperability issues in heterogeneous IoTs. Cluster Computing 2021, 24, 2133–2160. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Khan, L.; Zhou, S. Classified enhancement model for big data storage reliability based on Boolean satisfiability problem. Cluster Computing 2020, 23, 483–492. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Chu, L.; Pei, J.; Liu, W.; Bian, J. Model complexity of deep learning: A survey. Knowledge and Information Systems 2021, 63, 2585–2619. [CrossRef]

- Cronrath, C.; Aderiani, A.R.; Lennartson, B. Enhancing digital twins through reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 15th International conference on automation science and engineering (CASE). IEEE, 2019, pp. 293–298.

- Alcaraz, C.; Cazorla, L.; Fernandez, G. Context-awareness using anomaly-based detectors for smart grid domains. In Proceedings of the Risks and Security of Internet and Systems: 9th International Conference, CRiSIS 2014, Trento, Italy, August 27-29, 2014, Revised Selected Papers 9. Springer, 2015, pp. 17–34.

- Sagiroglu, S.; Sinanc, D. Big data: A review. In Proceedings of the 2013 international conference on collaboration technologies and systems (CTS). IEEE, 2013, pp. 42–47.

- Löcklin, A.; Müller, M.; Jung, T.; Jazdi, N.; White, D.; Weyrich, M. Digital twin for verification and validation of industrial automation systems–a survey. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th IEEE international conference on emerging technologies and factory automation (ETFA). IEEE, 2020, Vol. 1, pp. 851–858.

- Rokka Chhetri, S.; Al Faruque, M.A.; Rokka Chhetri, S.; Al Faruque, M.A. IoT-enabled living digital twin modeling. Data-Driven Modeling of Cyber-Physical Systems using Side-Channel Analysis 2020, pp. 155–182.

- Bandi, A.; Heeler, P. Usability testing: A software engineering perspective. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Human Computer Interactions (ICHCI). IEEE, 2013, pp. 1–8.

- Boyes, H.; Watson, T. Digital twins: An analysis framework and open issues. Computers in Industry 2022, 143, 103763. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Han, B.; Krummacker, D.; Schotten, H.D. Massive twinning to enhance emergent intelligence. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–4.

- Rivera, L.F.; Jiménez, M.; Villegas, N.M.; Tamura, G.; Müller, H.A. The forging of autonomic and cooperating digital twins. IEEE Internet Computing 2021, 26, 41–49. [CrossRef]

- Bonney, M.S.; de Angelis, M.; Dal Borgo, M.; Wagg, D.J. Contextualisation of information in digital twin processes. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2023, 184, 109657. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, P.; Dal Borgo, M.; Ruffini, V.; Hughes, A.J.; Zhu, Y.; Wagg, D.J. Towards the development of an operational digital twin. Vibration 2020, 3, 235–265. [CrossRef]

- Olivier, A.; Giovanis, D.G.; Aakash, B.; Chauhan, M.; Vandanapu, L.; Shields, M.D. UQpy: A general purpose Python package and development environment for uncertainty quantification. Journal of Computational Science 2020, 47, 101204. [CrossRef]

- Barricelli, B.R.; Casiraghi, E.; Gliozzo, J.; Petrini, A.; Valtolina, S. Human digital twin for fitness management. Ieee Access 2020, 8, 26637–26664. [CrossRef]

- Suhail, S.; Zeadally, S.; Jurdak, R.; Hussain, R.; Matulevičius, R.; Svetinovic, D. Security attacks and solutions for digital twins. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.12501 2022.

- Redelinghuys, A.; Basson, A.H.; Kruger, K. A six-layer architecture for the digital twin: a manufacturing case study implementation. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing 2020, 31, 1383–1402. [CrossRef]

- Campos-Ferreira, A.E.; Lozoya-Santos, J.d.J.; Vargas-Martínez, A.; Mendoza, R.; Morales-Menéndez, R. Digital twin applications: A review. Mem. Del Congr. Nac. Control Autom 2019, 2, 606–611.

- Harper, K.E.; Ganz, C.; Malakuti, S. Digital twin architecture and standards. IIC Journal of Innovation 2019, 12, 72–83.

- Juarez, M.G.; Botti, V.J.; Giret, A.S. Digital twins: Review and challenges. Journal of Computing and Information Science in Engineering 2021, 21. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Weeber, M.; Birke, K.P. Advancing digital twin implementation: A toolbox for modelling and simulation. Procedia CIRP 2021, 99, 567–572. [CrossRef]

- Ran, Y.; Zhou, X.; Lin, P.; Wen, Y.; Deng, R. A survey of predictive maintenance: Systems, purposes and approaches. arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.07383 2019.

- Lim, K.Y.H.; Zheng, P.; Chen, C.H. A state-of-the-art survey of Digital Twin: techniques, engineering product lifecycle management and business innovation perspectives. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing 2020, 31, 1313–1337. [CrossRef]

- Rathore, M.M.; Shah, S.A.; Shukla, D.; Bentafat, E.; Bakiras, S. The role of ai, machine learning, and big data in digital twinning: A systematic literature review, challenges, and opportunities. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 32030–32052. [CrossRef]

- Suhail, S.; Hussain, R.; Jurdak, R.; Oracevic, A.; Salah, K.; Hong, C.S.; Matulevičius, R. Blockchain-based digital twins: research trends, issues, and future challenges. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2022, 54, 1–34. [CrossRef]

- Raj, P. Empowering digital twins with blockchain. In Advances in Computers; Elsevier, 2021; Vol. 121, pp. 267–283.

- Suhail, S.; Hussain, R.; Jurdak, R.; Hong, C.S. Trustworthy digital twins in the industrial internet of things with blockchain. IEEE Internet Computing 2021, 26, 58–67. [CrossRef]

- Putz, B.; Dietz, M.; Empl, P.; Pernul, G. Ethertwin: Blockchain-based secure digital twin information management. Information Processing Management 2021, 58, 102425. [CrossRef]

- Kuruppuarachchi, P.; Rea, S.; McGibney, A. Trust and security analyzer for collaborative digital manufacturing ecosystems. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Leveraging Applications of Formal Methods. Springer, 2022, pp. 208–218.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).